Notes

3 “House in Soho, London,” Architectural Design (December 1953): 342.

5 Banham, The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? (New York: Reinhold, 1966), 16.

6 Banham, The New Brutalism, 17.

7 Banham, The New Brutalism, 18.

8 Banham, The New Brutalism, 20.

10 Alison and Peter Smithson, The Heroic Period of Modern Architecture, Architectural Design (December 1965), 5.

11 Robin Boyd, “The Sad End of New Brutalism,” Architectural Review (July 1967): 10.

12 Boyd, 9.

13 John Summerson, “Introduction,” Ten Years of British Architecture: ’45-55, Arts Council of Britain, 1956, 11.

14 Reyner Banham, “The New Brutalism,” Architectural Review (December 1955): 355-6.

15 Banham, The New Brutalism, 134.

16 Reyner Banham, “This is Tomorrow,” Architectural Review (September 1956): 188.

17 Beatriz Colomina, “Brutalism and War,” in Brutalism: Contributions to the international symposium in Berlin, 2012, Park Books, 2017, 24. More than anyone else, Colomina has recognized the importance of the Smithson-Mies connection in numerous essays. See especially “Couplings,” in “Rearrangements, A Smithson Celebration,” OASE 51 (June 1999): 22-33.

18 The photographs appeared in the 1913 edition of Jahrbuch des Deutschen Werkbunds

20 Reyner Banham, A Concrete Atlantis: U.S. Industrial Building and European Modern Architecture 1900-1925, MIT Press, 1986, 21.

21 Banham, “The New Brutalism,” 358.

22 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 2.

23 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 1.

24 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 1.

25 Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, tr. H. Eiland and K. McLaughlin, Harvard University Press, 462.

26 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 2

27 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 7.

28 Banham, “The New Brutalism,” 358.

29 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 9

30 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 18.

31 Banham, “The New Brutalism,” 356

32 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 21.

33 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 8.

34 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 8

35 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 9

36 Banham, A Concrete Atlantis, 248-253.

37 Banham, “The New Brutalism,” 358, 361.

38 John Voelcker, “Letter,” Architectural Design (June 1957): 184.

39 Robin Middleton, “The New Brutalism or a clean, well-lighted place,” Architectural Design (January 1967): 7-8.

40 Vilém Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images, tr. N. Roth, University of Minnesota Press, 2011 [1985], 5

41 Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images, 170.

42 Vilém Flusser, “A New Imagination,” in Writings, ed. A Strohl, tr. E. Eisel, University of Minnesota Press, 2004 [1990], 114.

43 Jacques Rancière, “The Surface of Design,” 91-107 in The Future of the Image, tr. G. Elliott, Verso, 2007. First published as “Les ambivilences du graphisme” in Design … Graphique?, ed. Annick Lantenois, Ecole regionale des Beaux-Arts de Valence, 2002.

44 Rancière, “The Surface of Design,” 91.

45 Rancière, “The Surface of Design,” 106.

46 Rancière, “The Surface of Design,” 101.

47 Maryanne Wolf, Proust and the Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain, Harper Collins, 2007, 4.

48 Maryanne Wolf, Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World, Harper Collins, 2018, 1.

49 Wolf, Reader, Come Home, 2.

50 Wolf, Reader, Come Home, 2.

51 Wolf, Reader, Come Home, 8.

52 Wolf, Reader, Come Home, 8.

53 Wolf, Proust and the Squid, 17.

54 Wolf, Proust and the Squid, 5.

55 Wolf, Proust and the Squid, 12. “The various features that characterize the visual system—enlisting older genetically programmed structures, recognizing patterns, creating discrete working groups of specialized neurons for particular representations, making circuit connections with great versatility, and achieving fluency through practice—are similar in all the other major cognitive and linguistic systems involved in reading.” 15

56 Wolf, Reader, Come Home, 8.

58 Barbara Stafford, “Crystal and Smoke: Putting Image Back in Mind,” 33-34, in A Field Guide to a New Meta-Field: Bridging the Humanities-Neurosciences Divide,” University of Chicago Press, 2011.

59 Mark Hansen, “From Fixed to Fluid: Material-Mental Images Between Neural Synchronization and Computational Mediation,” in Releasing the Image: From Literature to New Media, eds. J. Khalip and R. Mitchell, Stanford, 2011, 104.

60 Hansen, “Fixed to Fluid,” 87.

61 Hansen, “Fixed to Fluid,” 104.

62 Hansen, “Fixed to Fluid,” 111.

Chapter 1 That’s Brutal

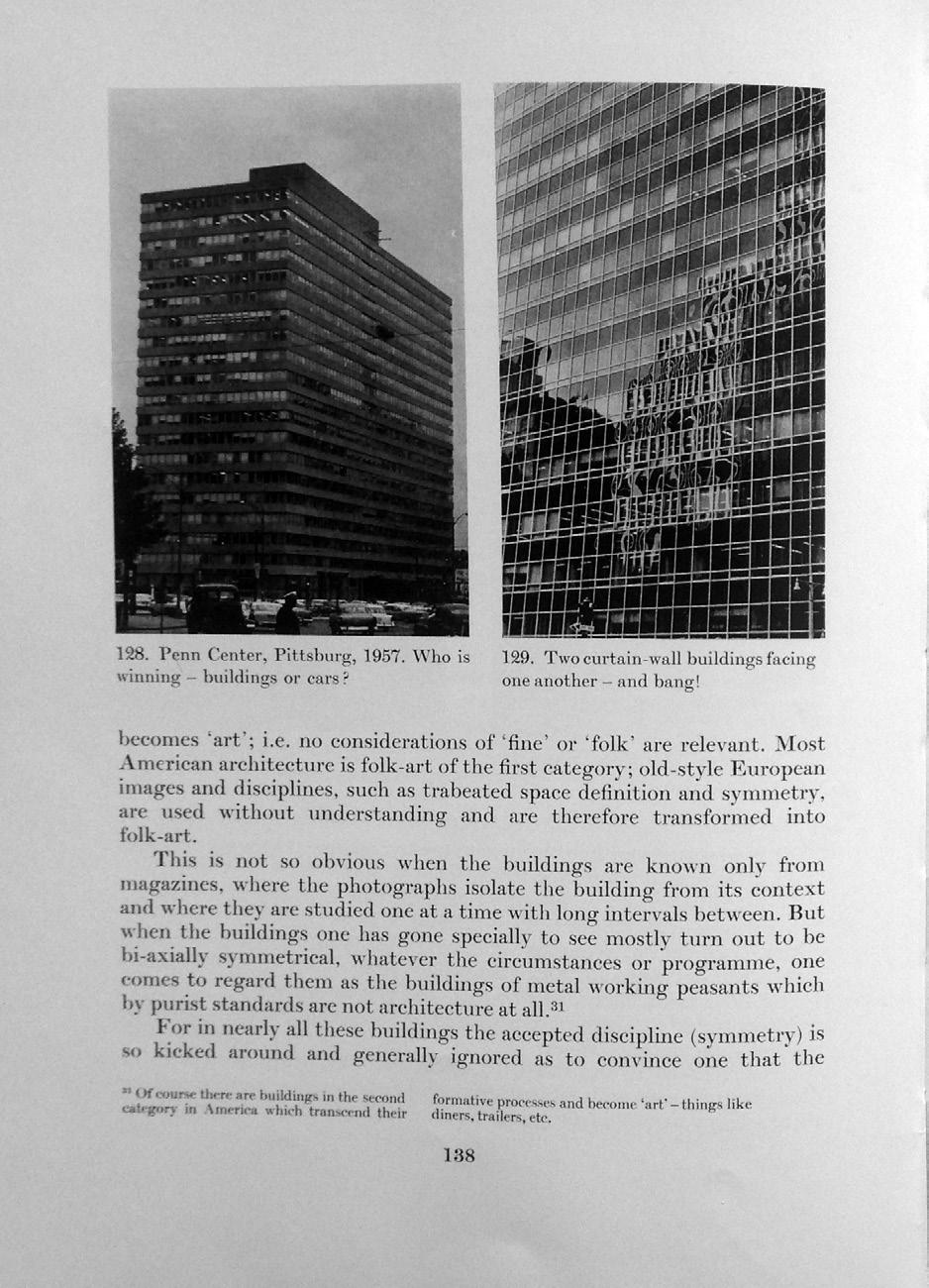

basis of New Brutalism is replaced by a fully anti-visual position: “Architecture remains a predominantly visual art; this may be regrettable but it is a historical and cultural fact, and it means that architects are educated and influenced primarily by the force of visual example.”29

In his explanation of the powerful influence of the photographs of factories and grain elevators on early modernist architects, Banham did more than emulate the methods of visual studies and formal analysis: he reinforced ideas about photography as mechanical, automatic representations that epitomize —or at the very least emulate and signify— scientific, technological, and even journalistic objectivity: “the power of the photographs comes from the fact that, like the works of engineering they represented, they were understood to be the product of the scientific application of natural laws. Having come into the hands of their European admirers in the guise of news photographs, rather than that of “art” photography, they were supposedly free from those elements of personal selection and interpretation that must inevitably infect any artistic rendering, or even the traditional production by architectural draftsmen of finished drawings from measured field notes. The photographs represented a truth as apparently objective and modern as that of the functional structures they portrayed.” 30

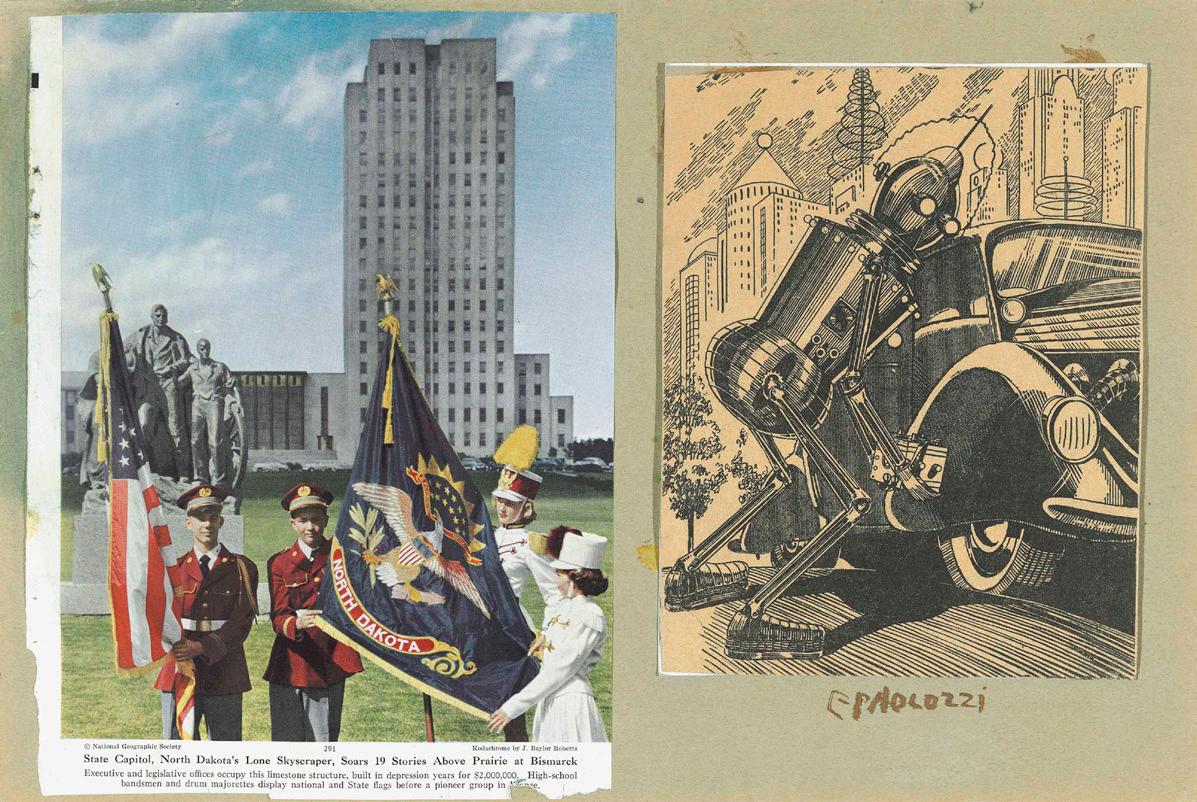

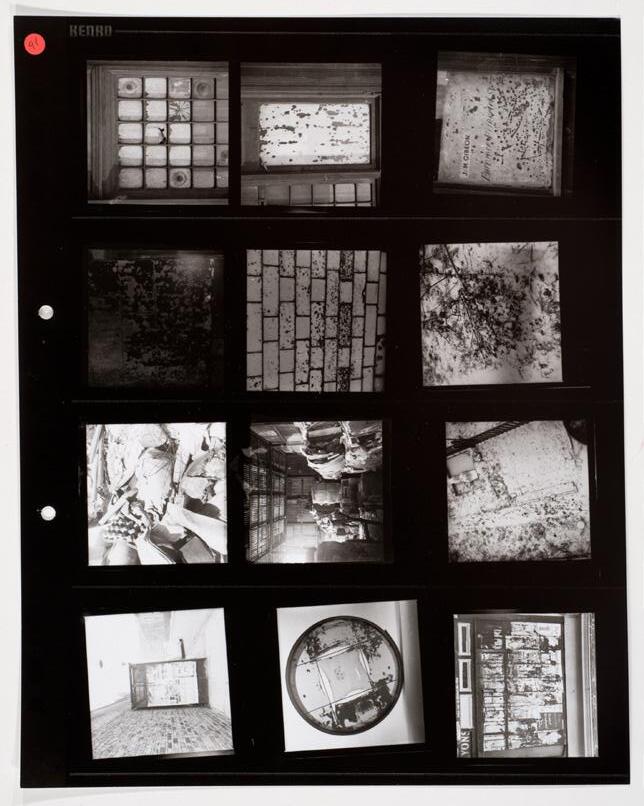

The contrast between Banham’s understanding of photography in A Concrete Atlantis and the New Brutalist’s understanding of photographic images is too clear to ignore. In fact, it was precisely an impulse against seeing documentary and scientific photography in terms of objectivity that inspired the New Brutalists’ first tests of an imaging aesthetic in projects such as Parallel of Life and Art (1953) and Patio and Pavilion (1956), or in the Smithsons’ photo-collages for the Golden Lane Housing competition (1952) and their uses of Henderson’s photographs in their CIAM Grille (1953), or that they continued to explore in their later essays and books. Most peculiar and symptomatic of all, at the end of the introduction to A Concrete Atlantis, Banham invited a comparison of classic modern architecture with New Brutalism by repeating a crucial phrase he had used in 1955. In “The New Brutalism” he declared that Parallel of Life and Art constituted the “locus classicus of the movement”31 and in A Concrete Atlantis he called the much earlier Fiat factory in Turin (1916-1923) “the locus classicus of modernism.” But in the latter case his assessment was quite literally classicizing: “the ambitions, expectations, and frame of mind that drove the founding fathers of the modern movement to adopt these [American] monuments as the models for their new architecture … expected to rediscover and then embody the eternal and fundamental verities underlying all great architecture, old as well as new.”32 While Banham did not endorse the poetics and aesthetics of the early modernists, he made no distinction between their “European” way of seeing and his own. As his argument develops in the introduction it becomes entirely clear that he, like the early modernists, saw the fourteen photographs as well as his own snapshot as imaginatively powerful not because they are concrete images, but because they are technical, optical images of things that “had concrete—literally concrete—presence here on earth.”33 The photographs depicting the “idealized but concrete industrial architecture

Todd Feinberg and Jon Mallatt, The Ancient Origins of Consciousness: How the Brain Created Experience

For a fascinating and comprehensive account of the evolutionary basis of the neural systems underlying reading, see Todd Feinberg and Jon Mallatt, The Ancient Origins of Consciousness: How the Brain Created Experience, vii-x, 69100, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017, especially the chapter “Consciousness Gets a Head Start: Vertebrate Brains, Vision and the Cambrian Birth of the Mental Image.”

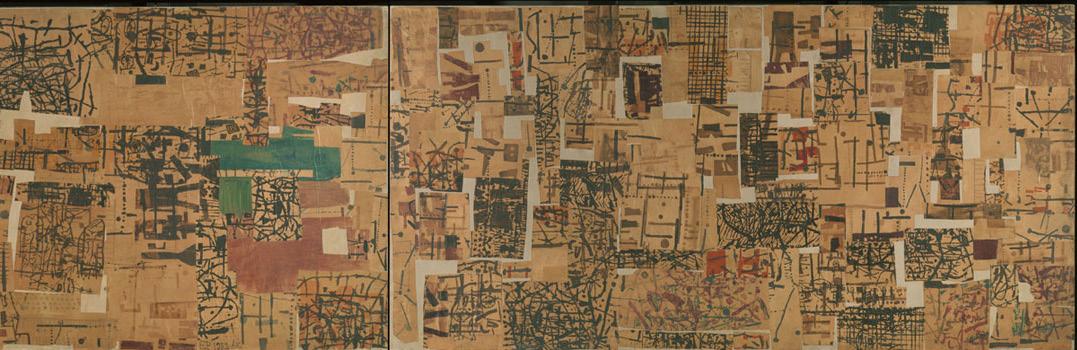

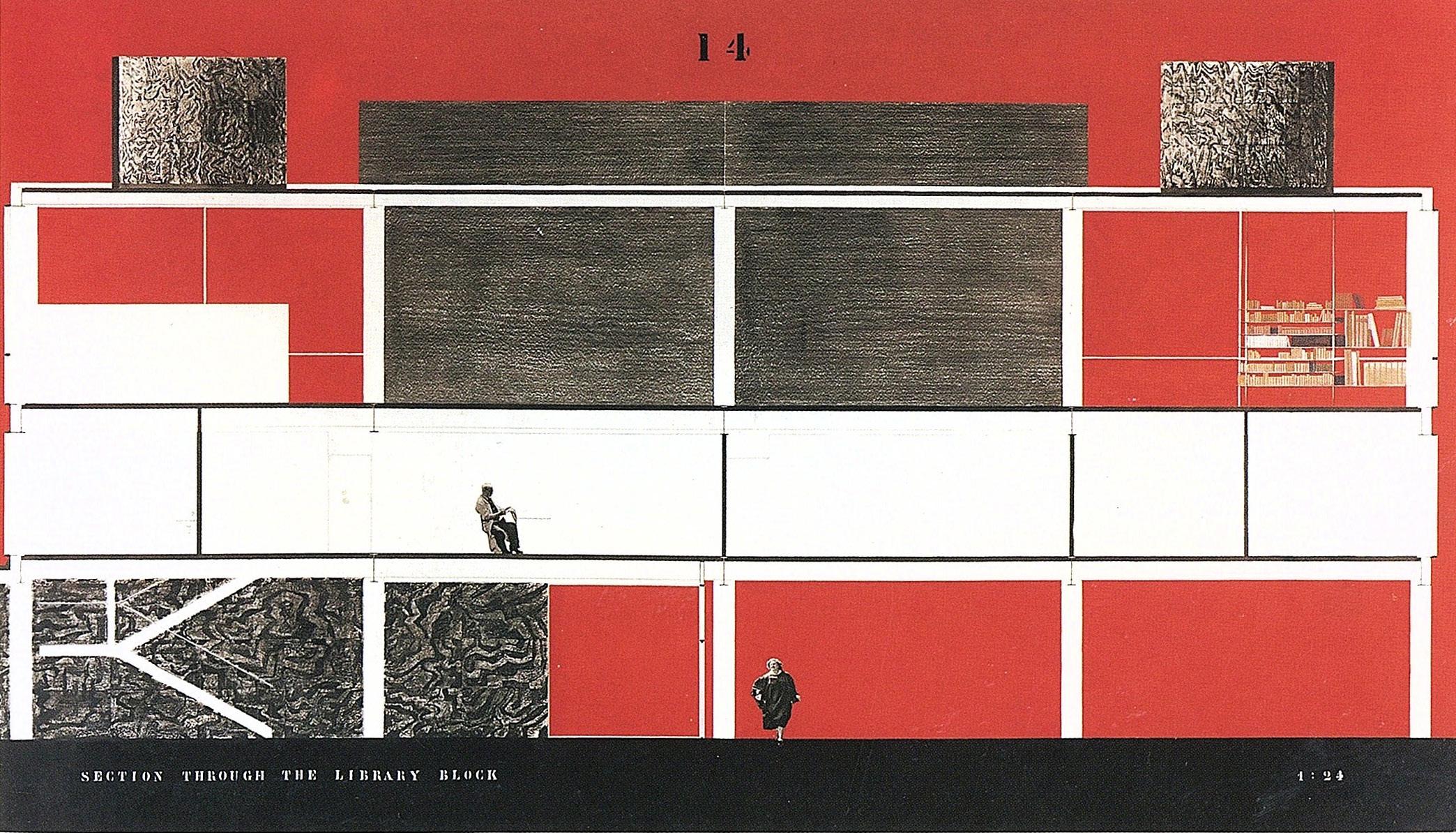

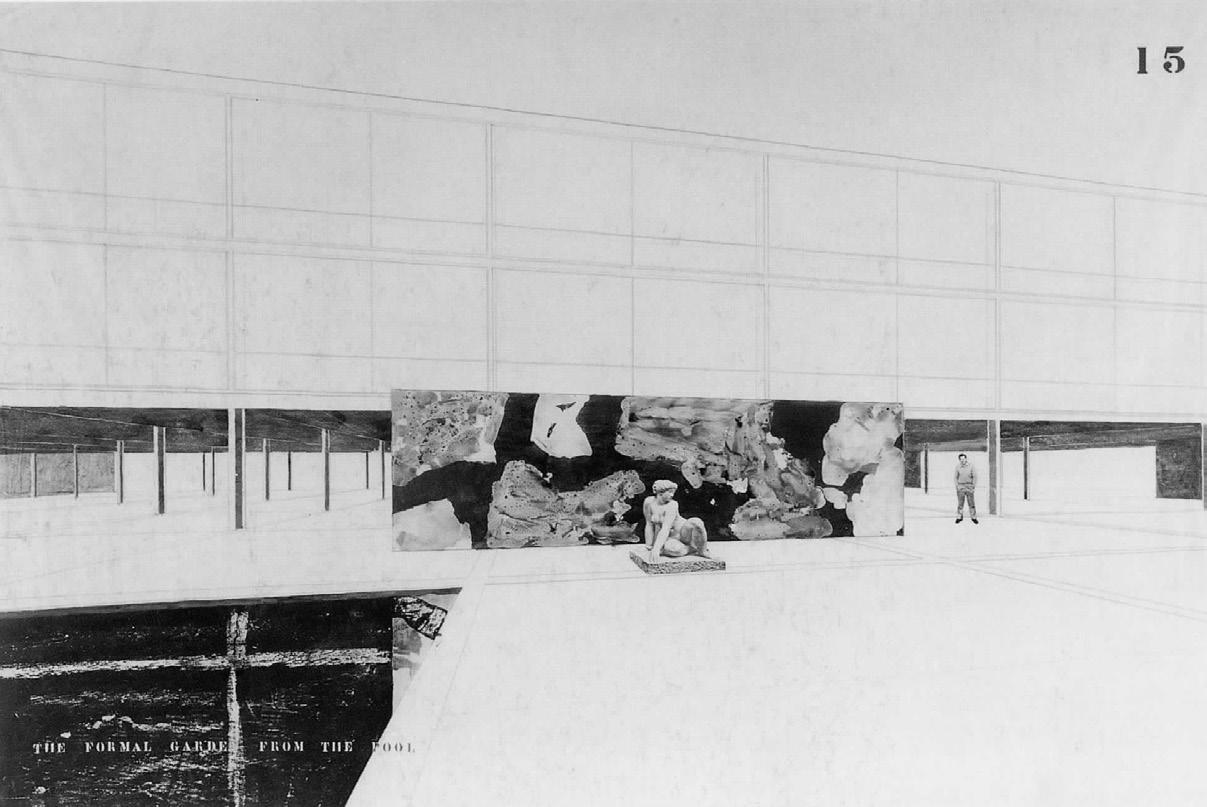

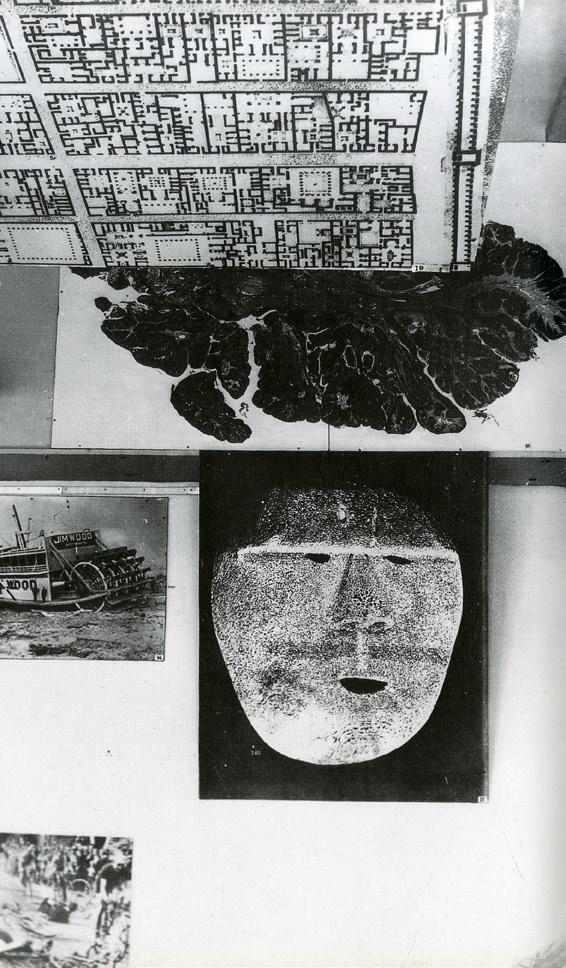

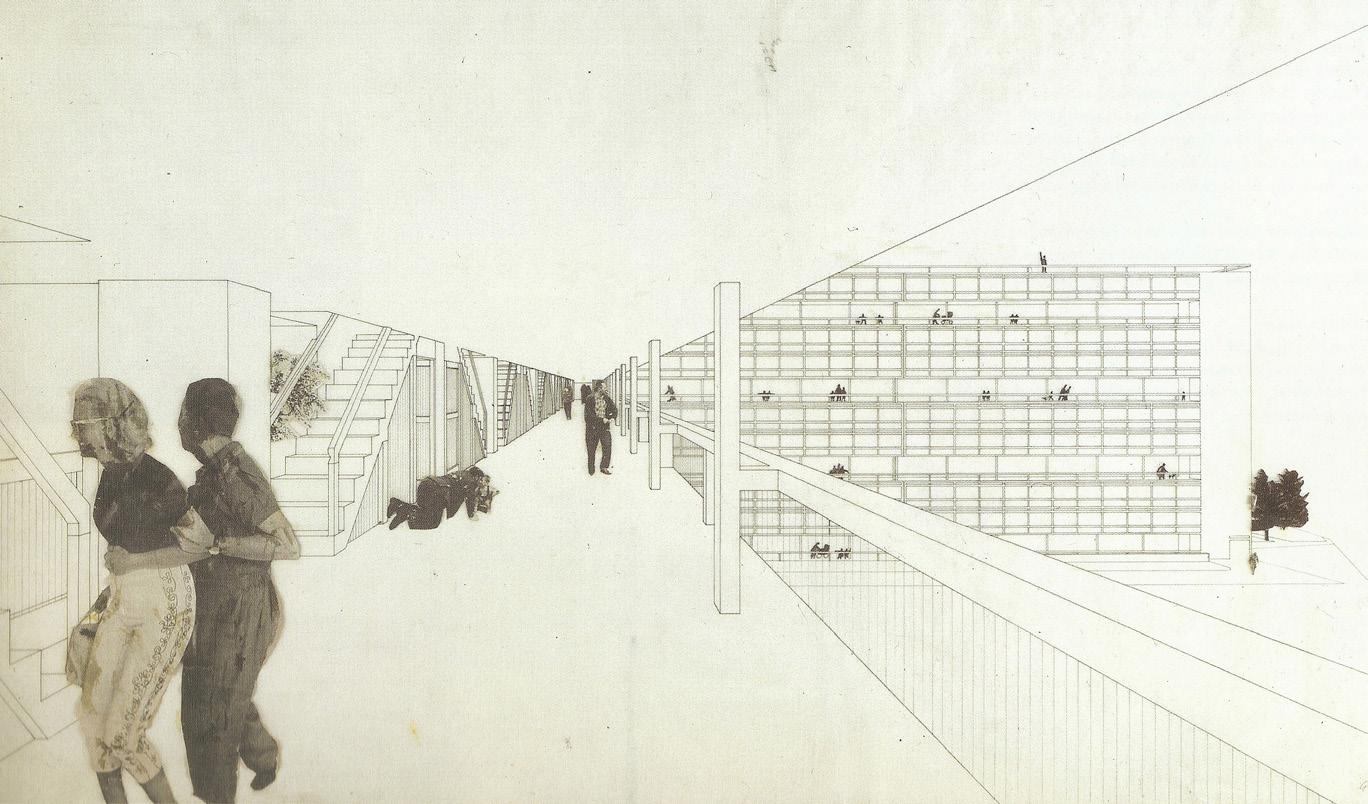

of North America”34 manifested the idea of science and technology that, Banham argued, fueled the “simultaneous quest for pure modernity and also ancient certainty” 35 that was shared by Loos, Gropius, Le Corbusier, Pevsner, and Giedion, and was evident above all in Edoardo Persico’s 1927 essay praising the “ancient order” of the Fiat Factory, which Banham quotes nearly in its entirety to make “the last argument of the book.”36 Thus A Concrete Atlantis ratifies and finalizes his rejection of his own pet ideas about the importance of concrete images for New Brutalism two decades earlier. That’s Brutal, What’s Modern attempts to recuperate both Banham’s rejected theorization and the Smithsons’ recursive practice of New Brutalism as ways of making and scrutinizing concrete images. It builds on Banham’s initial but not quite coherent theorization of New Brutalism in 1955 as an imaging practice which “requires that the building should be an immediately apprehensible visual entity, and that the form grasped by the eye should be confirmed by the experience in use” or, as he elaborated in reference to the Smithsons’ entry in the 1952 Golden Lane Housing competition, the “determination to create a visual image by non-formal means . . . and fully validating the presence of human beings as part of the total image… .”37 The following year Banham offered his crucial “concrete images” reformulation, yet only one year after that, in a letter to the editor of Architectural Design defending his ideas about New Brutalism, he would neglect his imaging theories, leaving it to John Voelcker, in a letter in the same issue of the journal, to offer what remains perhaps the most eloquent expression of those ideas: “Brutalism aims to invent those unique images from bits and pieces (stone, door handle, standard metal window, polythene pipe, etc.) which communicate and are inevitable in the historical/ecological/ technological situation ‘as found’.”38 Fast forward yet another ten years, and another evocative version of those ideas would appear in Robin Middleton’s review of Banham’s book. Seemingly responding to Banham’s misleading discussion of a “fusion of the Mies-Image and the Corb-Image,” Middleton suggested a different pairing of sources for the Smithsons’ “Brutalist” imaging practices:

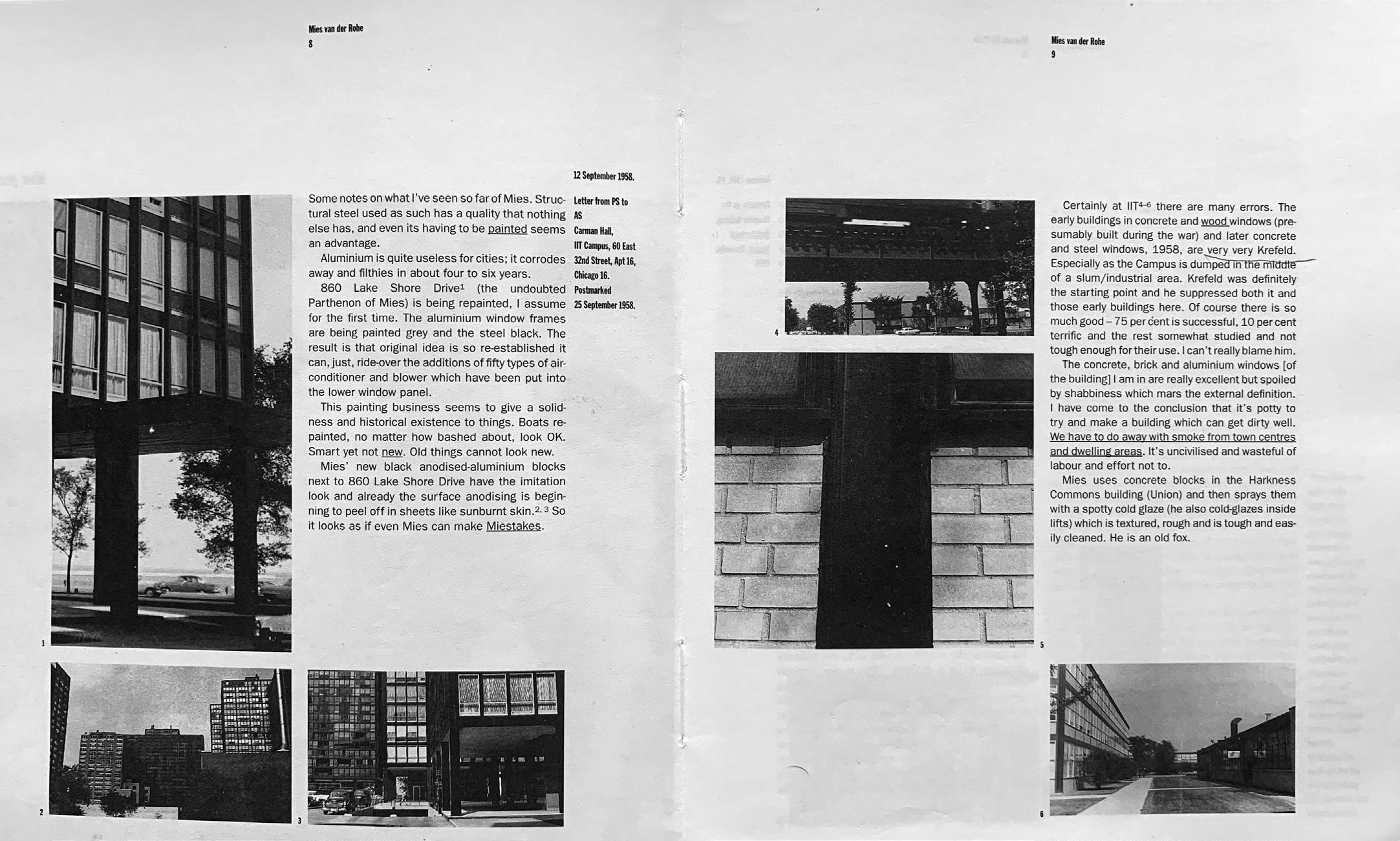

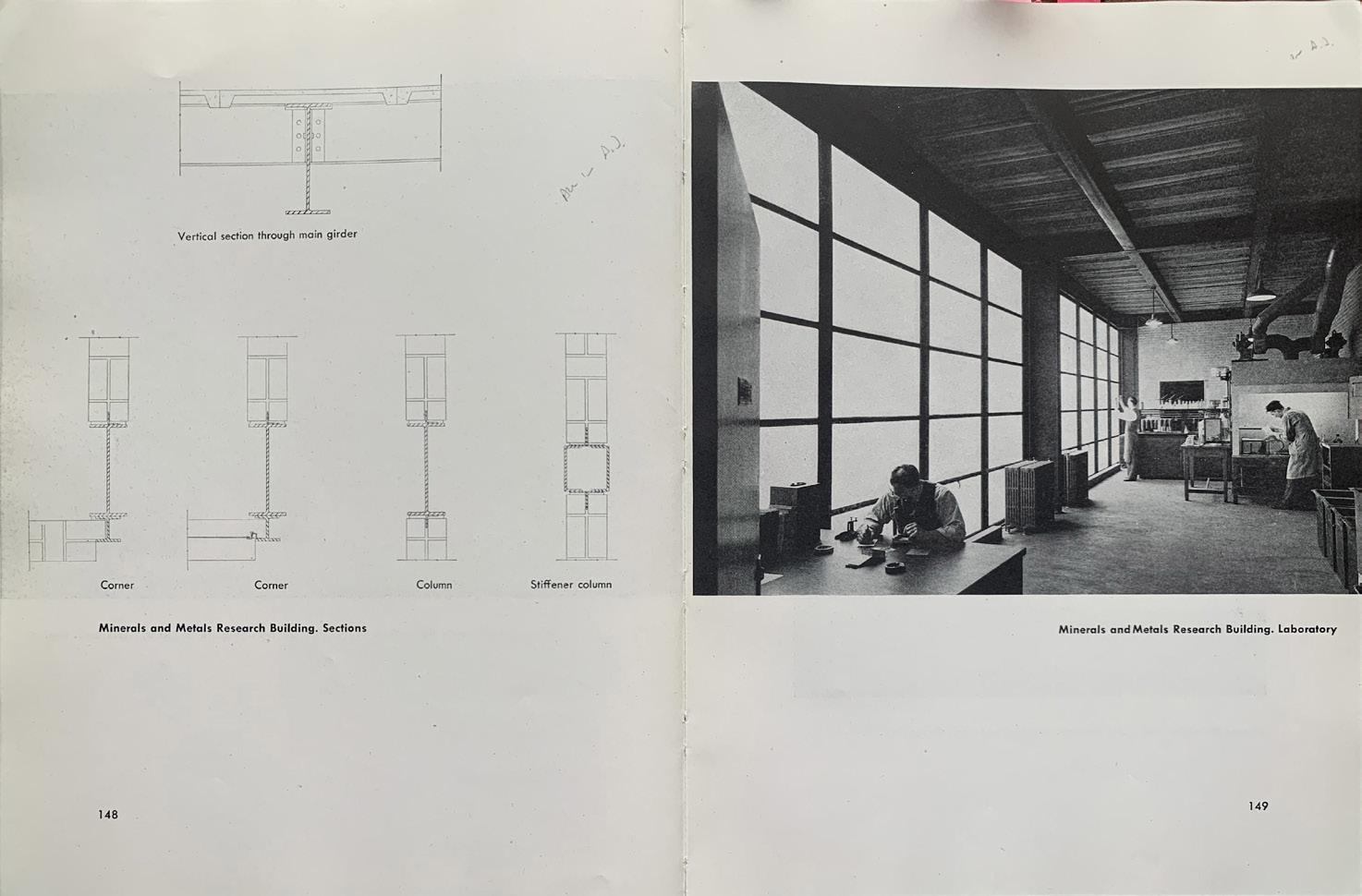

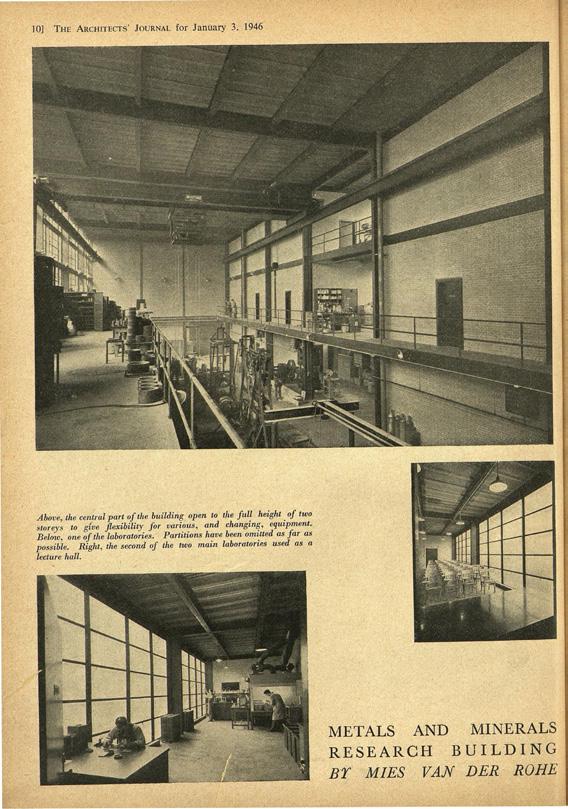

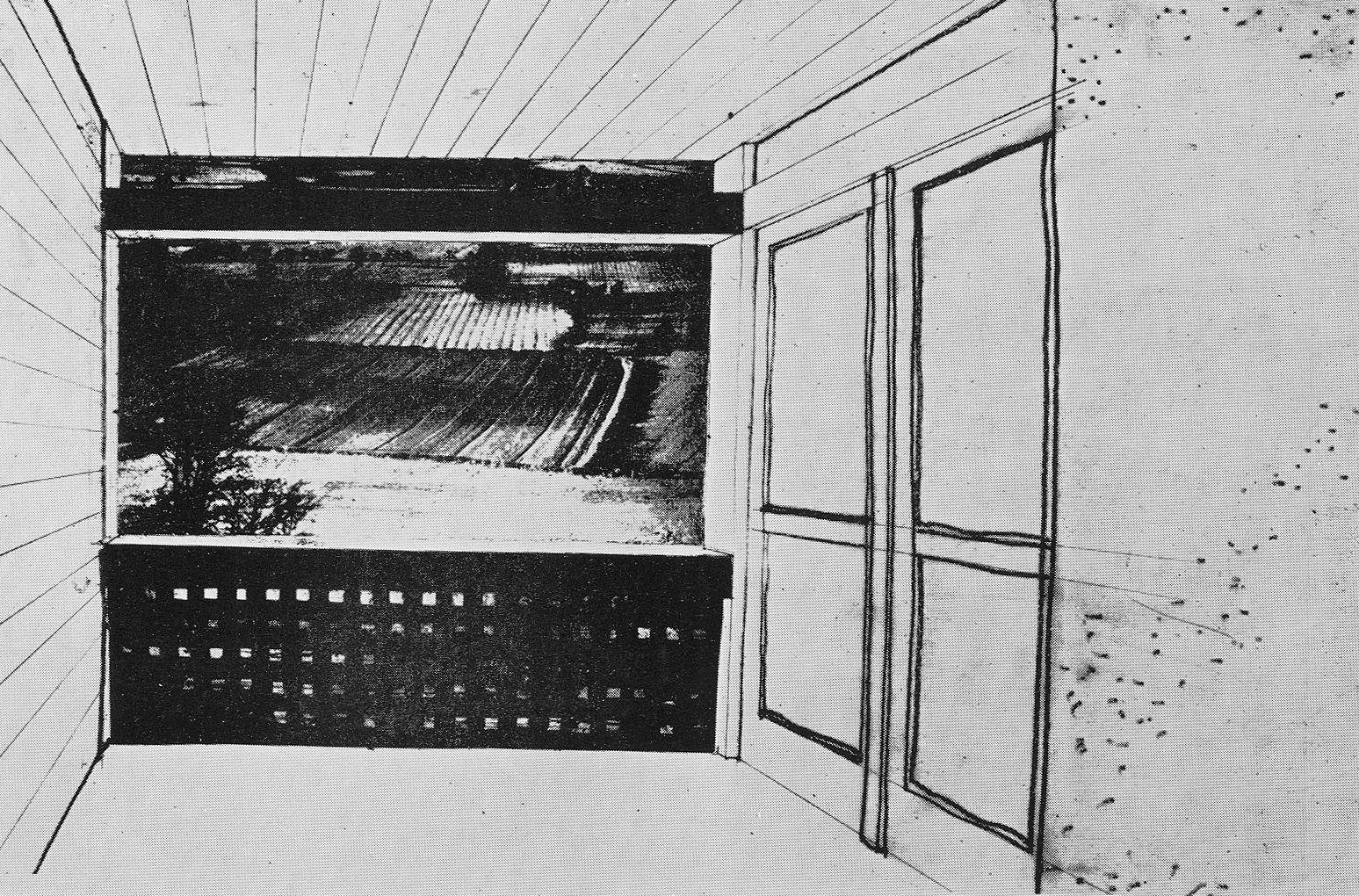

“Mies van der Rohe’s beautifully articulated buildings for the Illinois Institute of Technology suggested a point of departure— the buildings were reticent, clean and easily apprehended. They provided a ready-made aesthetic. But the Smithsons’ real discovery … was more personal in inspiration. They realized that they would have to build up their architecture from whatever fragments were available. … But the problem remained how to relate one to another and then to the building as a whole so that the result might be architecture. Charles and Ray Eames … provided the Smithsons with a clue. Objects could be arranged, apparently casually, against a neutral background to forceful resultant effect. The combination of the Mies aesthetic with the Eames concept of arrangement proved electrifying when interpreted by the Smithsons. The wash-handbasins and kitchen stoves at Hunstanton seen against the walls of glass convey still the strongest impression of the Brutalist image. But clearly architecture could not be composed like a pin-up board; at worst the method might be equated with flower arrangement.”39 [ARRAY4P: Brutalist Image]

Thus Middleton, like Banham, advanced imaging as crucial to New Brutalism but then retracted it as not adequately or fully