CONTENTS

Contributions and Acknowledgments

Framing

Foreword INTRODUCTION THE URBAN WORLD IS GRIDDED THE ATLAS OF GRID CITIES Grid Cities 101 Featuring the Values of Grid Cities GRID PROJECTS ACROSS HISTORY RESPONDING TO DIFFERENT NEEDS AND OBJECTIVES Founding the Gridded City: A Means to Control the Territory

a New Form of City: The Ideal City

Inventing

the Territory: Grid as Organizer for the Whole Country Composing the City by Fragments: Grids Defined by Discontinuous Open Spaces

City Searching for a Decentralized Model: The Discontinuous City Creating Capital Cities: The Symbolic Core and the Supporting Grid 6 10 14 30 32 140 176 194 220 242 268 286 308 328 356 1 1.1 1.2 2 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8

Extending the City: Great Urban Expansions of the Nineteenth Century Overlapping Grids: Transformative Devices for the Existing

THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY DILEMMA

DEFINING THE NEW URBAN CULTURE

Abandoning the Grid: The Modern City and New Traffic Demands

Revisiting the Grid: Six Lenses on the Post-WWII Urban Project

Defining Compositional Strategies: Key Episodes and Logics of City Design

Acknowledging Changes in the Grid: Alterations, Exceptions, and Transgressions

Constructing Urban Form: Design Tools for the Regular City

Integrating the Multilayer City: New Combined Roles for the Network and Block

ATLAS OF CONTEMPORARY PROJECTS 48 Projects Scanning the Specificity of Urban Projects PROJECTIVE DESIGN TOOLS REVISING TRADITIONAL INSTRUMENTS

THE EMERGENCE OF NEW URBAN GRIDS THE

GUIDELINES Endnotes, References, and Image Credits 378 386 400 420 422 476 506 522 566 590 616 632 668 3 3.1 3.2 4 4.1 4.2 5 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 6

THE GOOD GRID CITY AS OPEN FORM COPING WITH NEW URBAN ISSUES AND INTRODUCING FUTURE

City design has generated controversial discussion in recent decades. In fact, cities that were once models of urban planning during the post-war period are now seriously reviewing their urban plan in order to meet new emerging paradigms. The industrial system that induced much of the urbanization of the western world now plays a secondary role, and today new dynamics operate both in urban centers and in the surrounding areas of influence, which in turn generate new and highly innovative metropolitan conditions. In response to these new economic dynamics and to the demands of emerging urban culture, a transformation is taking place in the forms and the processes of city design. The aim of this academic research is to emphasize the value of reconsidering open forms for city design, such as the grid city, for its adaptability to multiple programs and architectural morphologies.

The presence of regular forms or grids is manifest in the design of cities and their extension into conurbations. Some are almost automatic processes of decomposition of the land and spaces of infrastructures for subsequent construction in interstitial spaces, tending to produce a rather banal city, or a “city without attributes” as described by Robert Musil (1930). Others, however, offer potential innovation in city design because they ensure basic urban coherence, at the same time allowing a high degree of versatility over time: these are the reference models that this research into urban grids takes as its departure point.

The research aims to explore the regular city, today and in the past, by studying its morphological component, and to discover the wealth and immense adaptability of these urban forms. Its potential as an urban framework that can resist the passage of time and the evolution of social demands has been proven. It can be interpreted as an “open work” because it is never complete, even when a city becomes a monumental space, because its uses are changing. It is a cultural object capable of representing multiple symbolisms: from the mandala in India, to the Book of Rites or Liji in China, to the layout of the Roman cardinal axes. It has also been an agent or matrix of change or modernization as in the triangular grid that transformed Paris, or the decolonization proposal in Casablanca with the Gamma grid, as described by Tom Avermate and Maristella Casciato (2014). In these cases, the meaning of the grid can extend far beyond the initial project and its politic value to become an instrument capable of channeling local housing aspirations and become an important urban piece in the present-day city.

In the grid city, then, we have a form of city design that is backed by fascinating experiences: from the Commissioners’ Plan for New York’s Manhattan in 1811 to Cerdà’s Plan for Barcelona in 1855; from the ancestral, hierarchical regularity of Xi’an to today’s maxi-grids in Shenzhen; from the extensions of Amsterdam, re-scaling the old wharfs in the east of the city, to gigantic developments in East Asia.

With the regularity of this urban form, examples from very different periods and varied cultures seek to guarantee development over time, in most of the cases with a marked formal coherence.

A study of the historic evolution of the grid shows that it is an instrument with the ability to design urban space without a defined program. It also serves to organize the territory for purposes of control and administration; to establish principles that adapt over time, ensuring certain rules

FOREWORD

11 Foreword |

WHY A BOOK ABOUT GRIDS?

This book about eight years of research into the grid city at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) is divided into three parts: historical interpretation, its place in the culture of city planning or design, and pointers as to how city design may evolve in the mid-term. To this end, it offers some points of discussion and models to develop urban grid projects in social contexts of mature governance and administration.

The cultural roots of this approach to the grid city are explained in chapter three of this book. However, closer references include recent works in the project field such as those of Peter Eisenman (1986), particularly the book about his studios at the GSD from 1983 to 1985. Then there are the monographic publications of Mario Gandelsonas (1999) that reveal new readings and drawings of the American city, and Albert Pope’s (1996) exploration of the dissolution of the grid. European influences include the French school represented by Jean Castex and Phillipe Panerai (2004), the Venice School in Italy, with the investigation of urban morphology headed by Carlo Aymonino (1999), and the LUB directed by Manuel de Solà-Morales with Joan Busquets (1992), researching the Ensanche, an almost exclusive form of growth of Spanish cities, which, as explained in chapter 2.5, impacted much of Europe.

The general interest of architects in the regularity of the grid has many precedents, from Constantinos Doxiadis (1972) in studies of the Greek city, to Leslie Martin and Lionel March (1972) and their attempts to rationalize space and urban form, to Oswald Mathias Ungers (1997) and his work with regular planning rules, to Vittorio Gregotti (1966) and his attempts to fuse the field of architecture with that of urbanism. At some points of the investigation, inevitably, the perspective of the field of art and its associated critique made some necessary and very fruitful incursions thanks to powerful analyses made under the influence of the Bauhaus, such as those by László Moholy-Nagy (1930) and György Kepes (1965) with their efforts to update the approach to structuralism in art, design, and architecture in the sixties. Rosalind Krauss, too, made an interesting contribution to the subject of grids in her reader, published in 1985; and Benjamin Buchloh’s compendium (2015) is full of references for the 20th century.

Here we will refer to some of the works used as a basis for discussion at the seminar on urban grids, with the participation of over a hundred students in the course of six academic years, which served as a basis for the more specific research that this book offers. Alongside the reflections of the seminar, work on a dozen cities scanned in the course of the studios served to extend our knowledge of many types of grids and their contemporary evolution. A great deal of the hypothesis was drawn during a Senior Mellon Fellowship in 2009 and discussion with Phyllis Lambert at CCA in Montreal. The historic understanding of the city was based on the regular forms that urban projects contributed. The spaces of exploration and design further sought to examine this field to see to what extent the regular city project can be a valid strategy, and what elements or sequence of elements are needed to implement it. Most of all, however, the entire book is based on the monographic scope of the Faculty Research Seminars at GSD that started out from certain initial hypotheses to build a body of theoretical contribution to grid cities, looking beyond specific reflection on each city, though including it. Our sincere thanks to all those who attended for their diverse and varied contributions.

INTRODUCTION

|

for Regular City

16

Urban Grids: Handbook

Design

001 003 005 007 009 011 013 015 017 019 021 023 025 027 029 031 033 035 037 039 041 043 045 047 049 051 053 055 057 059 061 063 065 067 069 071 073 075 077 079 081 083 085 087 089 091 093 095 097 099 101 002 004 006 008 010 012 014 016 018 020 022 024 026 028 030 032 034 036 038 040 042 044 046 048 050 052 054 056 058 060 062 064 066 068 070 072 074 076 078 080 082 084 086 088 090 092 094 096 098 100 Abu Dhabi Algiers Amsterdam Baku Bari Berlin Bogota Brasilia Budapest Canberra Caracas Chandigarh Copenhagen Damascus Edinburgh Guadalajara Hangzhou Ho Chi Minh City Houston Jaipur Kansas City Khartoum Kyoto Lima Los Angeles Madrid Maputo Medellin Messina Milan Monterrey Moscow New Orleans Osaka Palermo Philadelphia Portland Rio de Janiero Rotterdam Salt Lake City Santiago de Chile Seattle Shanghai St. Louis Taipei Tokyo Tunis València Vienna Xi’an Zhengzhou Alexandria Almaty Athens Barcelona Beijing Bilbao Boston Brussels Buenos Aires Cape Town Casablanca Chicago Curitiba Denver Glasgow Hague Helsinki Hong Kong Islamabad Johannesburg Kaohsiung Krakow La Plata Lisbon Lyon Mannheim Marseille Melbourne Mexico City Milton Keynes Montreal Naples New York City Ouagadougou Paris Phoenix Prague Rome Saint Petersburg San Francisco Savannah Seoul Shenzhen Stockholm Tehran Toronto Turin Vancouver Washington, D.C. Yangon

THE ATLAS OF GRID CITIES Methodological Understanding

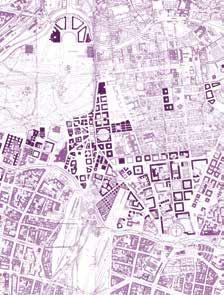

The 101 selected city projects provide a representative sampling of various manifestations of the urban grid from across the world. The broad survey reveals the urban grid as a mediator of many conditions common across urban practices, from the topography of the site to the efficiency of the city’s infrastructure, the flexibility of its mobility networks, the densities and programmatic mixes it enables, and its capacity towards change. The descriptive approach of the atlas allows for a systemization of knowledge from these cities, focusing on quantitative design features so as to better understand qualitative values.

The following city by city analysis is organized on a consistent template, annotated to the left. The process of analysis proceeds from an initial phase of research into the history and geography of the city, the major urban projects that have shaped the city through time, and an interpretation and classification of the city as one of six types of grid cities.

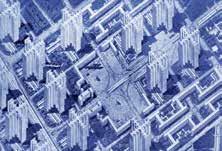

This initial reading leads to a selection of a representative city district for measured analysis at multiple scales. The analysis of a representative 1000meter extract of the city reveals the qualities of the multi-layered urban grid, specifically the capacity of the regular spatial field to enable an efficient overlay of public transit grids, primary street grids, secondary grids and patterns of open space embedded within the system of streets. An analysis of block size reveals the relative regularity of block forms produced by the grid, and an analysis of land use reveals the relative diversity and mixing of programs enabled by the grid. Land use is represented at either the scale of the parcel or the block, depending on the information that is available.

A further analysis of a 400-meter extract of the city reveals the qualities of the urban form in relation to the spatial field of the grid. The reading of the parcellation of the block reveals the regularity of land division and the subsequent subdivision or aggregation that is enabled by each particular grid project, while the reading of the urban fabric reveals the relation of patterns of built form to the space of the street, as well as exceptions to this regularity. 400-meter axonometric studies reveal the

three-dimensional forms and densities enabled by the selected grids. Where the information is available, a single extract is studied across two time periods to better understand the grid’s capacity for measured change both morphologically and typologically.

Following the measured analysis in plan, three to four street sections are studied in an effort to understand the hierarchies embedded in the grid and the quality of spaces they produce. Particular attention is paid to the organization of the surface of the street into multiple strips, which allow for a desired mixing of uses and different speeds of movement; the volume of the street, as defined by built form and tree plantation; the distribution of program, responding to the verticality of the section; and the incorporation of underground elements, including basement levels and metro. The study concludes with a synthetic drawing, organized to address and amplify selected characteristics and qualities of each city. Methods to the synthetic interpretation range from a delamination of the multiple layers to a city’s grid, to the identification of distinct grid fragments across the space of a city, the superimposition or addition of distinct grid projects across a city’s evolution, and the analysis of how a city’s grid operates across scale.

The necessarily subjective aspects of the study should as well be acknowledged. The choice of cities is driven by an intent to capture a diverse selection of urban practices and conditions across the world and through history. Beyond a few paradigmatic cases, a different set of cities could have reasonably been chosen. In addition, the analysis within individual cities is guided by an interpretation of the most significant and representative urban grid project in each city’s history, an interpretation which then guides the following layers of analysis. The interpretive lens is explicitly demonstrated in the designation of cities by grid city type, summarized on the following page, a classification which helps to structure the comparative study that directly follows the atlas.

1.1 A1 A2 A3 A4 B1 B2 B3 B4 CITY RESEARCH

city plan

locator map

Descriptive text Relevant

5km

Aerial image 1,000m ANALYSIS

Major grids Minor grids Block size Program distribution

C1 C2 C3 C4 D E F 400m ANALYSIS Building footprints Parcellation Axonometric 1 Axonometric 2 URBAN BLOCK STREET HIERARCHY SYNTHETIC READING

37 1.1 The Atlas of Grid Cities | A1 E F B1 C1 C3 B3 D B2 C2 C4 B4 A2 A3 A4

BUENOS AIRES

Established in 1580 on the Rio de la Plata, Buenos Aires is characterized by its infinite grid and regular manzana blocks of 110 meters square. Across this pattern of the same block repeated without differentiation or hierarchy, large infrastructural pieces began to be inserted into the city through the synthesis or removal of several blocks, notably through the construction of the 9 de Julio Avenue in 1816. The typical block of Buenos Aires is completely built out, with larger pockets of green space appearing the further one moves out from the city center.

140m 6.5 6.5 11.5 11.5 23 23 16 16 7 7 2 2 8 Boulevard Section 30m 5.5 5.5 19 8m 3 2.5 2.5 Street Section Alley Section 400m 400m 125m 115m 47m 47m 10m 10m 30m 125m 125m 125m 10m 400m 400m 125m 115m 47m 47m 10m 10m 30m 125m 125m 125m 10m Residential Mixed-Use Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural / Religious Office Open Space -2000m² -4000m² -8000m² -6000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -14,000m² -15,000m² -25,000m² 1000m 125 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 40m 1000m 10m 10m 10m 10m 10m 10m 10m 30m Residential Mixed-Use Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural / Religious Office Open Space -2000m² -4000m² -8000m² -6000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -14,000m² -15,000m² -25,000m² 1000m 125 10 10 10 10 10 10 40m 1000m 10m 10m 10m 10m 10m 10m 10m 30m Residential Mixed-Use Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural / Religious Office Open Space -2000m -4000m² -8000m -6000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -14,000m -15,000m² -25,000m² Residential Mixed-Use Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural / Religious Office Open Space -2000m -4000m² -8000m -6000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -14,000m -15,000m² -25,000m² 125 118 Residential Mixed-Use Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural / Religious Office Open Space -2000m² -4000m -8000m² -6000m -10,000m -12,000m² -14,000m² -15,000m -25,000m² Residential Mixed-Use Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural / Religious Office Open Space -2000m² -4000m -8000m² -6000m -10,000m -12,000m² -14,000m² -15,000m -25,000m²

Division

de la

de Buenos Aires, 1769 34° 36’ S 1940 / 2010 18 1.18 Building Footprints Block Dimension Primary Grid Parcellation Program Secondary Grid 56 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

Eclesiástica

Ciudad

The cellular grid structure of Chandigarh, developed from 1951 by the office of Le Corbusier following the earlier planning efforts of Albert Mayer, is composed of a regular hierarchy of streets (“Vs”) and open space corridors underlying a grid of cells measuring approximately 1 by 1.6 kilometers. Urban functions are organized at the scale of the cell as well as the scale of the larger grid, as seen in the designation of an entire cell for civic and commercial functions. Symbolic capital functions are concentrated in a single area, at the northern terminus of Leisure Valley, between the city and mountains beyond.

1000m 1000m 1000m 1000m -2500m² -5000m -7500m² -10,000m² -12,500m -15,000m -17,500m² -20,000m -22,500m² 1000m 1000m Surface Parking Park / Plaza Mixed Use - Res. Mixed Use - Com. Institutional Market Rec. Office Hotel -2500m -5000m² -7500m² -10,000m -12,500m² -15,000m² -17,500m -20,000m² -22,500m² 1000m 1000m Surface Parking Park / Plaza Mixed Use - Res. Mixed Use - Com. Institutional Market / Rec. Office Hotel Boulevard Section 16m 32m 73m 6 10 16 3 22 10 7.5 7.5 6 4 9 3 1 6 4 1 1 4 Alley Section Street Section Block Parcelization Urban Density Block Section (Related 400x400 Grid Analysis/2013 400m 400m Block Scale(m ) 44,800 68,200 29,400 2 150m 150m 140m 290m FAR: 0,4 FAR: 2,1 Block Parcelization (Related to Infrastructure) 500m 400m 25m 22m 6m 45m 6m 24% 6% 6% 43% 21% 44,800 68,200 29,400 150m 150m 140m 290m 400m 400m 57 27 87 52 57 18 12 10 70m 60 20 70 42 40 400m 400m 57 27 87 52 57 18 12 10 70m 60 20 70 42 40 6 6 8 8 10 30m 190 180 -2500m² -5000m² -7500m² -10,000m² -12,500m² -15,000m² -17,500m² -20,000m² -22,500m² 1000m 1000m Surface Parking Park / Plaza Mixed Use - Res. Mixed Use - Com. Institutional Market Rec. Office Hotel -2500m² -5000m² -7500m² -10,000m² -12,500m² -15,000m -17,500m² -20,000m² -22,500m² 1000m 1000m Surface Parking Park / Plaza Mixed Use - Res. Mixed Use - Com. Institutional Market / Rec. Office Hotel

Plan of Chandigarh, Le Corbusier, 1951 30° 45’ N 1966 / 2010 23 1.23 Building Footprints Block Dimension Primary Grid Parcellation Program Secondary Grid 61 1.1

Atlas of Grid Cities |

CHANDIGARH

The

A former British colony and significant port city, Hong Kong is characterized by the use of the grid to negotiate urban density across a highly irregular topography. Following a series of land reclamations, growth has shifted towards methodologies of vertical expansion and the multiplication of grounds in the form of networks of public bridges and tunnels layered above and below the inherited street grid, connected to public transit. An array of discontinuous, regular grids conforming to the varied shoreline continues to define the core of the city.

Mixed-Use / Res. Commercial Institutional Hotel -2000m² -3000m² -5000m² -4000m² -6000m² -8000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -20,000m² Office Government 1000m 24m 20m 20m 25m 25m 22m 1000m 22m 17m 12m 12m 14m 14m 14m 25m Mixed-Use / Res. Commercial Institutional Hotel -2000m² -3000m² -5000m² -4000m² -6000m² -8000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -20,000m² Office Government Mixed-Use / Res. Commercial Institutional Hotel -2000m² -3000m² -5000m² -4000m² -6000m² -8000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -20,000m² Office Government 1000m 24m 20m 20m 25m 25m 22m 1000m 22m 17m 12m 12m 14m 14m 14m 25m Mixed-Use / Res. Commercial Institutional Hotel -2000m² -3000m² -5000m² -4000m² -6000m² -8000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -20,000m² Office Government 400m 400m 40 36 48 50 45 43 43 14m 14m 12m 25m 14m 14m 28m 10m 10m 88m 82m 50m 94m 25m 400m 400m 40 36 48 50 45 43 43 14m 14m 12m 25m 14m 14m 28m 10m 10m 88m 82m 50m 94m 25m 400m 400m 40 36 48 50 45 43 43 14m 14m 12m 25m 14m 14m 28m 10m 10m 88m 82m 50m 94m 25m 400m 400m 40 36 48 50 45 43 43 14m 14m 12m 25m 14m 14m 28m 10m 10m 88m 82m 50m 94m 25m 14m 8m 26m 26m 3.5 3.5 9.5 9.5 1 9 2.5 2.5 11 2 9.5 6 4 3 6 1.5 1.5 42 94 Mixed-Use / Res. Commercial Institutional Hotel -2000m² -3000m² -5000m² -4000m² -6000m² -8000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -20,000m² Office Government Mixed-Use / Res. Commercial Institutional Hotel -2000m² -3000m² -5000m² -4000m² -6000m² -8000m² -10,000m² -12,000m² -20,000m² Office Government

HONG KONG Plan for the Development of the Port of Hong Kong, 1941 22° 17’ N Block A / B 36 1.36 Building Footprints Block Dimension Primary Grid Parcellation Program Secondary Grid 74 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

MEXICO CITY

Mexico City was established by Hernán Cortés in 1521 on the site of the razed Aztec city Tenochtitlan, near the site of the ancient grid city of Teotihuacan. The new layout, designed by A. G. Bravo, V. de Tapia, and two Aztec assistants, is centered on the Plaza Mayor and composed of 100 city blocks organized into quadrants by two principle north-south and east-west avenues. Subsequent growth following the drainage of vast lakes and wetlands is characterized by an accumulation of distinct grid forms, a repetitive pattern of cellular maxi-blocks and an extensive transit network.

1000m 13 17 13 14 13 11 12m 1000m 13m 18m 13m 13m 17m 13m 11m 13m 19m 13m Residential Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural Parking -6000m² -7000m -10,000m² -8000m² -12,500m -15,000m² -20,000m² -30,000m -45,000m² 1000m 13 17 13 14 13 11 12m 1000m 13m 18m 13m 13m 17m 13m 11m 13m 19m 13m Residential Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural Parking -6000m² -7000m -10,000m² -8000m² -12,500m -15,000m² -20,000m² -30,000m -45,000m² Residential Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural Parking -6000m -7000m² -10,000m² -8000m² -12,500m² -15,000m² -20,000m -30,000m² -45,000m² Residential Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural Parking -6000m -7000m² -10,000m² -8000m² -12,500m² -15,000m² -20,000m -30,000m² -45,000m² 400m 360m 92m 97m 165m 17m 13m 115m 75m 125m 16m 12m 400m 360m 92m 97m 165m 17m 13m 115m 75m 125m 16m 12m 92m 97m 165m 17m 13m 115m 75m 125m 16m 12m 32m 26m 14m 5m 5 6 27 6 6 6 2.5 2.5 3 3.5 3.5 7 207 82 Residential Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural Parking -7000m² -8000m² -12,500m² -15,000m -30,000m² -45,000m Residential Institutional Hotel Commercial Cultural Parking -7000m² -8000m² -12,500m² -15,000m -30,000m² -45,000m

19° 26’ N

Plan De La Nouvelle Ville De Mexique, De Fer, 1715

1918 / 2014 58 1.58 Building Footprints Block Dimension Primary Grid Parcellation Program Secondary Grid 96 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

NEW YORK CITY

Founded as New Amsterdam in 1624, New York City is defined by the overlay of a rectangular grid plan across Manhattan Island north of Houston Street, as detailed in the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. The grid has proven resilient, as the coupling of the bi-directional lot configuration and three-dimensional building codes have produced a series of distinct building typologies, from the dumbbell tenement to the step-back tower of 1916. The aggregation of multiple blocks at moments of interchange led to the design of superblocks of greater densities, from Rockefeller Center to Hudson Yards.

1000m 30m 20 30m 30m 30m 1000m 25m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m High-Rise Resid. Mixed Use / Res. Institutional Hotel Mixed Use / Com. Cultural Religious Office Parking -2000m² -4000m² -8000m² -6000m² -10,000m² -12,500m² -15,000m² -17,500m² -20,000m² 1000m 30m 20 30m 30m 30m 1000m 25m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m 17m High-Rise Resid. Mixed Use / Res. Institutional Hotel Mixed Use / Com. Cultural / Religious Office Parking -2000m² -4000m² -8000m² -6000m² -10,000m² -12,500m² -15,000m² -17,500m² -20,000m² High-Rise Resid. Mixed Use / Res. Institutional Hotel Mixed Use / Com. Cultural / Religious Office Parking -2000m² -4000m -8000m² -6000m -10,000m² -12,500m -15,000m² -17,500m -20,000m² High-Rise Resid. Mixed Use / Res. Institutional Hotel Mixed Use / Com. Cultural / Religious Office Parking -2000m² -4000m -8000m² -6000m -10,000m -12,500m -15,000m² -17,500m -20,000m² 30m 28m 5 5 5 2.5 6 6 3.5 18m 3.5 3.5 2.5 2.5 4 2 20 5 30 400m 400m 244m 30m 62m 62m 62m 62m 62m 18m 18m 18m 18m 18m 400m 400m 244m 30m 62m 62m 62m 62m 62m 18m 18m 18m 18m 18m 245 62 244m 30m 62m 62m 62m 62m 62m 18m 18m 18m 18m 18m High-Rise Resid. Mixed Use / Res. Institutional Hotel Mixed Use / Com. Cultural / Religious Office Parking -2000m² -4000m² -8000m² -6000m -10,000m² -12,500m -15,000m² -17,500m -20,000m² High-Rise Resid. Mixed Use / Res. Institutional Hotel Mixed Use / Com. Cultural / Religious Office Parking -2000m² -4000m² -8000m² -6000m -10,000m² -12,500m -15,000m² -17,500m -20,000m²

40° 42’ N 1937 / 2010 66 1.66 Building Footprints Block Dimension Primary Grid Parcellation Program Secondary Grid 104 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

Commissioners’ Plan, Simeon De Witt et al., 1811

GRID PROJECTS ACROSS HISTORY

Responding to Different Needs and Objectives

This publication examines regular cities on the basis of key objectives that prompted their creation or pursued the transformation that the implementation of grids subsequently brought about. We have chosen eight goals, each described separately, in order to examine the specific instruments that have informed their spatial regularity.

2.1 FOUNDING THE GRIDDED CITY: A MEANS TO CONTROL THE TERRITORY

This section explores the grid city as a powerful instrument in the control and constant use of the territory. A selection of examples serves to explain, even today, the urban form and the structure of the territory in the long term. Here, there are two different blocks: the bastides in France, and the colonization of territories beyond Europe starting in the fifteenth century.

In the first block, in the case of the bastides in France, the territory was relatively delimited, and the aim was to control and exploit it: cities were key elements in this strategy. It coincided with the rebirth of cities in Europe after the medieval period, when they were characterized rather by their lack of economic and urban dynamics. The bastides organized the urban settlement, with its streets, squares, and protective boundaries, and guaranteed its evolution, while its strategic location articulated the broader territory with a highly homogeneous, consistent logic of spatial distribution. There are other similar examples such as the new settlements in Florence, Poland, and in Majorca with the pobles of Jaume I.

This course of action was later consolidated even further as a way of restructuring the territory to adapt it to new techniques of exploitation. This is the case in the seventeenth century, with the rural colonies in Sierra Morena, Spain, planned by Olavide and Campomanes under the reign of Carlos III; the city of La Carolina in 1769 is a good example (see Oliveras Samitier, 1998). Later on, we could also associate the productive industrial colonies built to harness the energy of water, or to mine resources, such as saltpeter or coal; and, finally, cities linked to a specific industry, be it Pullman cars in Chicago at the end of the nineteenth century, or chocolate in Broc, Switzerland; or footwear production like the famous case of Bata in Czechoslovakia last century, as a good example of developing a city that is more than a simple industrial holding.

The second block describes various urban models in the colonization of many of the territories outside Europe by applying very different urban patterns and design techniques. It includes a wide range of generally very basic interventions, with the aim of settling residents to exploit a territory, at the same time, in many cases, ensuring protection, as enclaves of future trade with other cities. The rules governing the construction and layout of the plots were very simple, though still responding to symbols of religious beliefs as the exportation of faith (for the case of Latin America, see the Psicon monograph, issue 2, 1975, particularly the interesting analyses by Jorge

Hardoy).

Hardoy).

The end of the fifteenth century saw the consolidation of a new vision of the terrestrial world. Progress in navigation—particularly in instruments for geographical orientation—were to have consequences for the urbanization of vast territories (America, Asia, Africa), consolidating

178 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

FOUNDING THE GRIDDED CITY

A Means to Control the Territory

The following section examines the foundation of the grid city as a means to control a greater territory. A series of case studies are investigated, from the model of the bastides of southwest France in the 12th and 13th centuries to the various colonial models of city-making and territorial control in the Americas and elsewhere from the 14th through the 18th centuries. We will find that despite the diversity in context of the cases studied, the spatial field of the urban grid was proven instrumental to the implementation of these projects, together providing a foundational model for urbanization that has a lasting imprint on these cities and territories today.

Particular attention is paid to the universality of the model of the urban grid and its flexibility or adaptability across a variegated terrain. These tensions between the universal and the local, and the relationships across scale enabled by the grid, guide the following analysis. First, research is done on the wider colonial project, tracing its territorial extent and distribution of settlements. Second, a selection of cities are traced to their foundational extents at scale, allowing for a comparative reading across each project and leading to the induction of general rules and the tracing of a “model” grid per episode. Third, the foundation of a single city is traced across scale, from the spatial field of the urban unit to the organization of the hinterland and the city’s relation to other settlements within a territorial network.

The bastides of southwest France, constructed primarily by French and English rulers across a territory loosely defined from the early 12th century, provide an early example of the application of a regular town model following the logic of a grid. The territory is defined and controlled over the course of over a century through the incremental planting of clearly defined town enclosures. Located across fertile lands and centered on market squares, the bastides together form what is here described as an incomplete territorial patchwork. Similarly, the Spanish project of city-making in the Americas pursues the control of a much wider territory through the incremental establishment of regular settlements following a singular town model, often located near or adjacent to existing population centers. Each new city is centered on a plaza and

surrounding administrative core linked directly to the Spanish crown, and organized on an openended grid providing the capacity for growth and adaptation. Unparalleled in scope and duration, the systemization of town planning practice by the Spanish enables a more complete network than any other colonial project, essentially laying a completely new urban system over the existing articulated landscape of the Americas.

The French settlement of the Americas, in contrast, is primarily characterized by the strategic control of trade routes through the establishment of discrete fortified outposts and towns along major waterways. Settlement forms range from the incremental linear grid patterns of early settlements along the Saint Lawrence River to more grandiose orthogonal grids at New Orleans and Louisburg, which exhibit logics of symmetry and axiality derived from European precedent. The British models across America are diverse in scope and geared towards settlement and agricultural production, controlling access to the hinterland through the establishment of coastal cities near entrances to waterways. Three distinct colonial planning projects in Pennsylvania, Carolina, and Georgia serve as experiments for the import of new Enlightenment ideals in city and territorial planning, each deploying the grid across scale in

an effort to structure a new society. Together, these models provide a foundation for later, more speculative town planning efforts that utilize the grid for efficiency and equal land subdivision, a process that will displace indigenous populations through a gradual territorial demarcation westwards.

Last, the Dutch model is characterized by a global network of strategic outposts driven by commercial interests and, as the other colonial models, dependent upon the subjugation of local populations and exploitation of certain resources. The cities are sited on major waterways and characterized by the import of regular grids informed by universal ideals. The section concludes with a comparative study across the five models, identifying similarities and inducing qualities and conditions that remain relevant to urban practices today.

Asia, as well as the colonial cities of the Portuguese Empire, which in many cases became intertwined with the expansion of other European models across the globe.

2.1 Founding the Gridded City |

2.1.1 View of Santo Domingo by John Ogilby, 1671. (Facing page) Mapping of the five select models. The study could be expanded to include, among others, the bastides of King Edward I in northern Wales, the Florentine New Towns of the 14th century, the Nuevas Poblaciones de Andalucía y Sierra Morena of 18th-century Spain, the application and adaptation of Spanish, French, and British models across Africa, the Middle East, and

2.1.1 View of Santo Domingo by John Ogilby, 1671. (Facing page) Mapping of the five select models. The study could be expanded to include, among others, the bastides of King Edward I in northern Wales, the Florentine New Towns of the 14th century, the Nuevas Poblaciones de Andalucía y Sierra Morena of 18th-century Spain, the application and adaptation of Spanish, French, and British models across Africa, the Middle East, and

197

THE CITY BEAUTIFUL MOVEMENT

Defining New Centralities

The City Beautiful movement overlaid onto the existing city a logic of civic nodes interconnected by monumental avenues, one sharing formal characteristics with the cases of Rome and Paris but enacted through a different mechanism, the comprehensive urban plan. A study of two proposals emblematic of the movement, Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s plans for San Francisco and Chicago, demonstrate an approach to the city that accounts for multiple physical layers and modern demands, including circulation and hygiene, pursuant of the belief that improvements to the civic spaces of the city can lead directly to improvements in the quality of life of the citizenry.9 The proposals of Burnham and Bennett rely on a calibrated relationship between nodes, networks of avenues, and existing grids, as well as the diagonal overlay as a means to connect the city’s civic center to the expanded periphery of the twentieth century metropolis. Often commissioned through private initiative, and lacking in either the absolute power of the Papal States nor the developmental mechanisms of Haussmann’s Paris, the comprehensive plans of the City Beautiful remain largely unrealized, functioning instead as points of reference for the eventual realization of more limited civic projects characterized by the incision of few, key diagonals and well-defined urban ensembles.

The viability of the comprehensive plan largely relies on its coordination with the grids of the existing city. The opening of new oblique avenues addresses a principal disadvantage of the orthogonal grid, the restriction of diagonal movements, by opening direct routes across long distances.9 In addition the opening of diagonals and nodes introduces unique spatial conditions across otherwise undifferentiated grids, producing new hierarchies of interest in the city as well as opportunities to apply three-dimensional building controls across new continuous developments.

An early discourse on the utility of the diagonal overlay as a mechanism to improve the inherited orthogonal grid is seen in Buenos Aires around the turn of the twentieth century. Following the opening of the first principal avenue in the city from 1884, the Avenida de Mayo, the Plan de Mejoras of 1887

proposes the opening of 36 kilometers of diagonals and over 26 hectares of squares to qualitatively transform the city’s core and connect the periphery.10 Although the plan of Antonio Crespo remained unrealized, a discourse began on the opening of diagonal overlays across the repetitive grid of the city, leading to the design of a regular mesh of diagonals by Enrique Chanourdie in 1906 and the ambitious plan by French architect Joseph Bouvard in 1909 for 32 diagonals and extensive parks across the greater municipality. This succession of proposals, the geometries of which are compared on the facing page, lead to the opening of two principal diagonals and the block-wide 9 de Julio Avenue by the 1920s.

In North America, the City Beautiful movement was largely borne out of the influence of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, which put on display a model “beaux-arts” city of classical order with underlying improvements in circulation and sanitation systems. Daniel Burnham, the principal organizer of the fair, and Edward Bennett would go on to design comprehensive plans for San Francisco, Chicago, and Manila, and take part in the McMillan Commission for Washington, D.C. in 1901. The movement led to a range of projects by others including new civic centers in Madison,

2.6.21 New Plan for Thessaloniki by Ernest Hébrard, 1917. An emblematic work of the period is seen in Hébrard’s plan following the fire, which replaces the pre-existing Ottoman order with a hierarchical system of avenues and streets combining an orthogonal and diagonal logic. The diagonal grid is configured as a means to define new centralities and suture the urban grid of the city center with the remaining urban fabric of the periphery.

2.6.20 Painting by Jules Guérin for Daniel Bur nham and Edward Bennett’s Plan of Chicago from 1909, capturing a dramatic view over the proposed civic center, facing west.

2.6.20 Painting by Jules Guérin for Daniel Bur nham and Edward Bennett’s Plan of Chicago from 1909, capturing a dramatic view over the proposed civic center, facing west.

324 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

Des Moines, and Denver, the overlay of the oblique Fairmount Parkway across the grid of Philadelphia, as well as comprehensive city plans such as the 1911 Plan for Seattle by Virgil Bogue.

NEW TOWNS OF HONG KONG

From Satellite Towns to the New Towns in the New Territories

The New Towns of Hong Kong are distributed across the irregular topography of the coastal territory, sited apart from but functionally dependent upon the inherited core of Kowloon and Hong Kong Island. Their planning dates to the colonial government’s response in the late 1950s to an influx of labor and capital following the Chinese Civil War, with population rising from approximately one-half million to over two million in only six years. Among a series of satellite towns constructed near Kowloon, Tsuen Wan became a model for subsequent compact, high-density developments, built on reclaimed land and typified by new high-rise housing typologies.

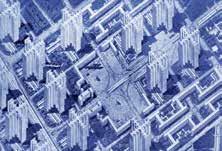

The program was officially launched in the early 1970s with the designation of Tsuen Wan, Shatin, and Tuen Mun across the largely rural New Territories. Unlike the satellite towns, the early new towns were detached from the inherited city and conceived as self-reliant communities, each containing a carefully calibrated mix of housing, recreation, and employment opportunities.4 By the time a third phase of new towns was initiated from the 1980s, including Tseung Kwan O and Tin Shui Wai, planning no longer followed the model of self-containment, as secondary industries had since moved to mainland China and employment was increasingly concentrated in Hong Kong’s financial and services center. The development of an efficient highway and commuter rail system connecting the new towns of the New Territories with Kowloon and Hong Kong Island has since become critical to their continued viability.

The new towns are generally planned around a town center, a concentration of commercial and cultural facilities at or near a primary rail station. These are supplemented with local shops, services, and facilities at the centers of individual housing estates, which are characterized by their high density and organized on a maxi-grid of roadways overlaid with networks of light rail or bus transit, as well as a dense network of pedestrian overpasses.

20km 10km 9 8 10 1 3

Sha Tin

Tseung Kwan O

Tung Chung

Tsuen Wan Tuen Mun

Tai Po

Fanling

Kwu Tung

Yuen Long

Tin Shui Wai

First generation new towns Hong Kong Island and Kowloon Second generation new towns Third generation new towns 1km10km

Hung Shui Kiu

2.7.11 Aerial sketch perspective of Shatin New Town, 1976. View from the northwest, over Shatin New Town Plaza and the Shing Mun River beyond.

342 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

Shatin

Tseung Kwan O

Tung Chung

Tsuen Wan

Tuen Mun

Tai Po

Fanling

Kwu Tung

Yuen Long

T in Shui Wai

1km 10km Regional boundary Urban boundary City center Area of new town Built area of new town Highway Boulevard Road Railway

Hung Shui Kiu

THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY DILEMMA

Defining the New Urban Culture

Chapter three looks at the radical evolution in urbanism throughout much of the 20th century. This was an important cultural change at a time when cities were undergoing major developments and transformations of a kind that had not previously been seen. This change was apparent above all in the erosion or even dissolution of the grid as a common pattern in the construction of the city, up until this point marked by continuity in formation and development, and in its various formalizations. The introduction of new paradigms associated with the architecture of the Modern Movement and of new forms of mobility with the implantation of the automobile, and the similarity between the city and means of industrial manufacture represent a series of transformations that were to create a strong contrast between the traditional and the metropolitan city. They were also to prompt a breakaway from the spatial forms and the concept of urbanity that the regular city had produced.

This chapter is organized in two parts. The first sets out to re-examine the abandonment of the grid. Some outstanding spatial paradigms were created, specifically the definition of the “unit” (from the field of sociological research, with the “neighborhood unit” as the basis of the social project); the concept of the “fish spine” as an urban framework according to the suggestions of Ludwig Hilberseimer and his replanning of urban grids; and, finally, the “superblock” as an organizational form that can accommodate new programs and the evolution of the dwelling.

The second part revisits the grid from the viewpoint of new principles which, though drawing on the advances of modern architecture, aim to overcome the spatial and environmental problems of the periphery and recover the quality engendered by traditional urbanity. The idea is to explore novel approaches that are not mere mimetic reproductions of the “city of yesterday” like some post-modern proposals put forward in the nineties. This second part introduces six innovative paradigms that establish the foundations of some present-day grid projects: the requalification of urban flows; a framework for new hierarchies; a matrix for large-scale buildings; the megastructure; the universal grid; and the recovery of the urban block.

By way of introduction, we would like to highlight some cultural phenomena that this major evolution in urbanism produced in the city as of the early decades of the 20th century, including the discontinuity between the historic and the modern city, and the new nature of the cosmopolitan city compared to the traditional city; and, finally, to present some modern or innovative projects that reinterpret the regularity of urban space despite not forming part of the main stream of Modern Movement architecture.

This is not the place for a review of the models or the doctrine of the modern city that have so profusely fueled the basic repertoire of much of the bibliography of urban design in the last century, of which the Atlas of the Functional City (2014) is a good example. Nor must we forget their contribution to improving housing conditions in general and the will to create new conditions for progress in society. Instead we will look at the new spatial and formal models to have emerged that may be useful for casting new light on other forms of regularity that are introduced as derivatives or by-products of the dominant doctrine that served to produce examples of city construction beyond the modernist principles that were posited as universal. A

380 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

REVISITING THE GRID

Six Lenses on the Post-WWII Urban Project

Significant shifts occurred following the Second World War, as urban design emerged as a distinct discipline and the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) was reaffirmed and later dissolved in 1959. As strict adherence to the functionalist doctrines of the Athens Charter subsided, urban practices became better characterized by an opening of discourse and a widening of approaches to new urban problems.1 The following section explores changes in the conception and implementation of the urban grid through this period of experimentation, complicating the inherited paradigms of the unit, superblock, and urban spine, and at times revisiting certain forms or design mechanisms from the 19th-century city.

The study begins with a survey of significant projects, publications, exhibitions, and conferences from the latter half of the 20th century. From this survey six paradigms are identified which, though not exclusive and necessarily subjective, together reveal the renewed and continued instrumentality of grid forms in city design. These paradigms combine a continuity of certain mechanisms from the early 20th century with a recovery of key ideas from before CIAM, notably those of Patrick Geddes and Camillo Sitte, as well as a recognition of new urban problems and conditions characterizing the postwar years, including the spread of the automobile, the increased scale and centripetal form of private development, and a perceived lack of coherence or historical continuity to the contemporary city.2

The first paradigm concerns the reconfiguration and requalification of the urban grid through an attention towards different modes of movement, demonstrated here in Louis I. Kahn’s Plan for Midtown Philadelphia from 1953. Kahn and colleague Anne Tyng’s notational drawings of present and proposed traffic patterns across downtown Philadelphia reveal the capacity of the differentiated, multi-layer grid to better address contemporary needs, reflecting a renewed attention towards the interrelationship of traffic and pedestrian uses of space, and a recovery of the street as an architectural space of particular value.

A second paradigm is found in the hierarchical maxi-grid, a mechanism developed in the post-war

years as a means to organize new urban expansions on the principles of functional zoning and ease of automobile access. Derived from the early twentieth-century paradigms of the superblock and the sector, the maxi-grid is here studied through its elaboration in the new city of Ciudad Guayana in eastern Venezuela. An exceptional case of a linear city of distinct sectors organized on grids responding to different functions, attention is given to the design of the new civic and commercial core, Alta Vista, and its regular grid of 300 by 150 meters.

A third paradigm concerns the three-dimensional grid as an organizational and structural framework for buildings of increasingly large scales, designed to address new ideas of mobility, adaptability, and an interrelationship of parts. Developed by members of Team 10 from the early 1950s, early experiments lead to the realization of a number of projects later identified as mat-building in Alison Smithson’s 1974 article “How to recognize and read mat-building.” This study focuses on the Free University Berlin competition and project from 1963, designed and realized by Candilis, Josic, Woods, and Schiedhelm on a module of 66 meters square.

Reynar Banham identifies a fourth paradigm, the megastructure, in his 1976 publication of the same name, describing a new type of three-dimensional grid that is able to integrate multiple layers of services and infrastructures while allowing for the proliferation of new urban forms connected beyond the traditional street grid.3 The grid of the megastructure is explored here through the speculative works of the Metabolists in Japan, showcased through the 1960 Tokyo World Exposition and based on the combined notions of growth and

change, and the project of Plug-In City by the architecture collective Archigram in the early 1960s.

A fifth paradigm is found in the “radical architecture” of Archizoom and Superstudio from the late 1960s, who deploy a universal grid as a diagram for new and infinite living environments. “Grid-space” permeates everything in their respective projects No-Stop City and Continuous Monument, from urban surface to interior object. While these projects remain conceptual, commentary may be read on the overlay of logistic and telecommunication grids in the second half of the 20th century and their relation to urban organizational systems, and a general predisposition towards the grid as a conditioning device for free movement and equality.4

The section concludes with the Berlin International Building Exhibition (IBA) of 1984/87, which demonstrates a renewed focus on the urban block as a site of experimentation, and the importance of the urban fabric in the definition of the collective space of the city. Rather than a simple recovery of the 19th-century Hobrecht Plan, the IBA Neubau projects of Ungers, Kollhoff, Krier, and others demonstrate innovations in the design of the street and the articulation of the block into gradated thresholds of interiority and exteriority. Together with the Altbau component focused on urban regeneration, Berlin’s IBA stands as one of several projects founded upon the values and knowledge ingrained in specific urban forms, works ranging from O. M. Ungers’s 1975 Roosevelt Island competition entry to the 1978 Roma Interrotta exhibition.5

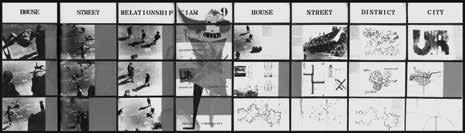

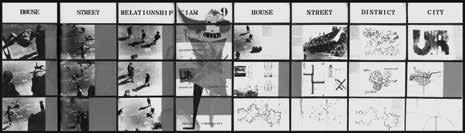

3.2.1 “Urban Re-Identification Grid” from CIAM 9, Alison and Peter Smithson, 1953. Based on a study of public spaces in the Bethnal Green neighborhood of London.

403

3.2 Revisiting the Grid |

THE ATLAS OF CONTEMPORARY PROJECTS

The 48 selected projects represent a global sampling of emerging forms of the geometrically regular city, together demonstrating a range of conditions that continue to inform the use of the urban grid today. The survey reveals the urban grid as a common instrument of continued importance in the design of cities, adapted to address the programmatic and functional demands of the near future.

The selection pulls from urban projects that have been established in the past three decades and remain in a process of maturation today. Each project demonstrates the extension, adaptation, or implementation of an urban grid as instrumental to its realization, and together the selection represents a relative diversity in scale, programmatic mix, and geographic location. The visual index on the facing page makes apparent this diversity in scale, ranging from a 4 hectare single block to a 7300 hectare new town project.

Similar to the Atlas of Grid Cities in chapter one, a consistent analytical framework is deployed across all case studies in an effort to make legible the geometries, dimensions, and programmatic mixes underlying each project. The research proceeds from an overview of each project’s site, situation, and the demands it is responding to, followed by a measured analysis at the project, neighborhood, and block scales.

At the project scale, a 2 by 2 kilometer focus area is chosen to analyze the project’s urban characteristics and design intent. A series of four plans isolate the figure of the project’s built and unbuilt space, the infrastructure network of the site and the fabric of the immediate surroundings. At the neighborhood scale a 400- by 400-meter sample area is chosen to analyze the project’s massing, block structure, open space structure, and mix of programs. At the block scale one or two representative blocks are isolated and studied to better understand the three-dimensional qualities of each project. In addition to these three scales, an urban section of a consistent 360-meter length is provided to make legible the calibrated relationships between interior and exterior and the sectional qualities of

the street, and an abstracted connectivity diagram and morphology diagram are included in the lower corner, highlighting the grid hierarchies embedded in the urban structure of each project and the compositional strategies guiding their organization in plan.

Following the atlas is a comparative scan of the 48 projects. Ten variables guide this analysis, from the dimension and shape of block types to the structure of open space and the mix of programs. Taken together, these scans allow for hypotheses to be drawn on the evolution of the urban grid in the near term and the conceptual frameworks we may deploy when considering future actions.

A1 B1 B2 B3 B4 C1 C2 C3 C4 D1 D2 E A2 A3 F1 F2 4.1

427 4.1 The Atlas of Contemporary Projects | A1 A2 A3 B1 B2 B3 B4 C1 C2 C3 C4 D1 D2 F1 F2 PROJECT OVERVIEW Aerial image Site plan Descriptive text PROJECT SCALE Figure Ground Infrastructure Context NEIGHBORHOOD SCALE Massing Block Open Space Program BLOCK SCALE Type #1 Type #2 PROJECT SECTION DIAGRAMS Connectivity Morphology E

Methodological Understanding

PROJECTIVE DESIGN ELEMENTS

The new value accorded to the grid city in projects currently under way is reviving the hypothesis of considering it as a powerful open form for designing the city of tomorrow. A prospective, creative vision today could offer good guidance in the mid-term.

The best way to advance seems to be to try to understand the key design elements that inspire or provide the framework for the present-day city project, and take them as pointers for work in the future. The idea is not so much to create a catalog or repertoire of new elements to apply to possible new realities, as to stimulate new reflection on elements that have shaped and framed the development of grids in the past and the present and that can be useful for the project of tomorrow. These include the following:

1.The compositional strategies of some seminal grid projects, which serve to explain the value of outlines that are frequently condemned or criticized as “just 2D,” or two-dimensional. Behind this apparent simplicity, however, lies a significant power to establish clear hierarchies and maintain their propositive capacity in the long term. Here, research will center on a synchronous examination of these outlines, some of them hundreds of years old, to produce a present-day interpretation and extract values of the urbanistic project that can be applied to today’s circumstances.

2.The changes or alterations in the original grid project, which enrich its language and its programmatic content. This is a reference not to adaptations that any city project undergoes due to geography or adjustments to its development over time, but to the exception or transgression in a canonical layout of the grid proposed by the project. This may be an element of singularity and an added value for the overall project. Close attention must be paid to the careful development of the exception or alteration to determine whether it truly benefits the whole. Strategic position and number of exceptions will probably be themes to take into account when evaluating their applicability to different realities.

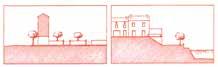

3.The design tools crafted to construct urban form, with the aim to understand the rules that complement the city layout, accompanying and ensuring its development in volume and program. They were initially considered to belong to the sphere of private interests that developed the city, and sought to guarantee construction rights and resolve conflicts between neighboring properties.

Urban rules have to frame urban architecture, so they normally respond to prototypical initial images that are then implanted in the process of developing the overall project. Today, these rules have multiplied and become extraordinarily sophisticated, also in response to the legal and administrative complexity surrounding city development. However, it is interesting to take a closer look at urbanistic problems and the urban forms that respond to different cultural and economic realities with a view to extracting clear new city design conditions in the mid-term. The anticipatory vision apparent in Raymond Hood’s images of Manhattan in the 1920s now needs new tools that can synthesize present-day demands, such as a multifunctional, multi-social city, sustainable mobility, and others, as we will go on to see.

508 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

Revising Traditional Instruments

DEFINING COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES

Key Episodes and Logics of City Design

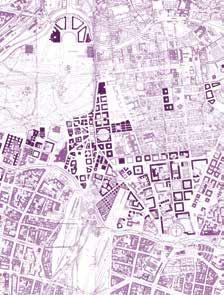

The following section explores the compositional strategies underlying a selection of seminal grid city projects. Unlike more normative or elementary urban grids, the eight selected city projects demonstrate relatively complex grid compositions that have been produced through the identification of a clear design idea and the repetition of a few measured acts. Considered together, this synchronic reading of city projects renders visible a range of strategies and morphologies that may continue to inform creative solutions to the design of urban grids today.

The section is organized in three parts. The first, “Compositional Strategies,” is structured on a series of drawings which speculate upon the decisions and strategies leading from an initial design idea, above, to the composite urban form we commonly recognize, below. This is followed by a series of tracings of the eight city projects overlaid at scale, opening speculation on the relationship across parts of various projects and the opportunities of such compositional strategies to inform the ongoing definition of grid fragments in heterogeneous urban contexts. The second part, “Key Episodes,” examines each project individually in greater depth in regards to its urban history and evolution, considering the physical, economic, and cultural contexts that have informed its composition and subsequent transformations. The third part, “Interpretive Framework,” positions the selected city projects within a wider discourse of antinomies commonly used to qualify urban projects.

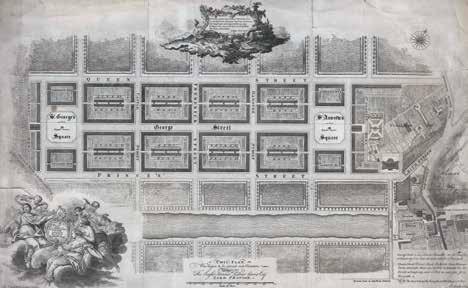

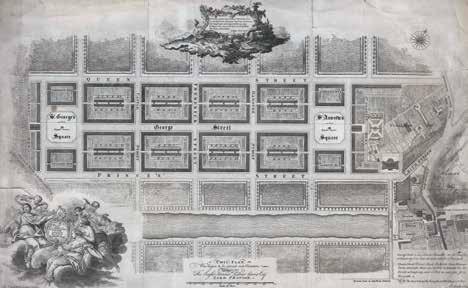

The index of drawings on the facing page provides an introduction to the study through the identification of the most salient characteristics of each city project. In the cases of Lisbon and Edinburgh, a regular grid is generated through the definition of an axis or pair of axes. Each axis is anchored by a pair of squares and defined by a symmetrical disposition of compact urban blocks. In the case of Central Milton Keynes, a visual axis aligned to the midsummer sun anchors the organization of the grid, but the hierarchy of streets is inverted with major lines bounding the district in a maxi-grid formation. Unique to Milton Keynes is the composite overlay of multiple types of grids and the

sectional separation of pedestrian and automobile networks. In all three cases the topography of the site informs the orientation of the axis, aligned to a valley-line in the case of Lisbon and a ridge-line in the cases of Edinburgh and Milton Keynes.

In the case of Savannah, a multi-scalar grid is generated through the repetition of a basic urban unit, the ward, and a territorial unit, the square-mile tract. The interrelation and incremental subdivision of these two systems produces a composite grid form of remarkable complexity and adaptability.

In the case of Tang-era Chang’an (Xi’an) and Heian-Kyo (Kyoto), a comprehensive hierarchical grid determines the organization of urban space at the macro and micro scales. While the grid of Chang’an is generated through the definition of three perimeter gates on each side, connected by wide avenues that organize the city into sectors, the grid of Heian-Kyo is generated in a centrifugal manner, characterized by an open perimeter and based on the scalar subdivision of an orthogonal spatial field. All three cases exhibit an acentric disposition of an urban or administrative core aligned to a north-south axis of varied importance.

In the cases of Saint Petersburg and L’Enfant’s plan for Washington, D.C., the superimposition of

multiple orders results in a grid system with greater variation. The grid of Saint Petersburg is generated from the extension of axes from three nodes, each taking on a different geometry in response to conditions of site and shoreline. The resulting network of axes makes coherent the distribution of grid fragments of different orientation. The grid of Washington, D.C. is generated from the siting of key capital elements and the superimposition of a diagonal and orthogonal order derived from these elements. A diagonal network, generated by radials extending from two primary and secondary nodes, is overlaid onto a more regular grid of streets defining the scale of the urban block.

5.1.1 James Craig, Plan of the New Streets and Squares intended for the city of Edinburgh, 1768.

525 5.1 Defining Compositional Strategies |

OGLETHORPE PLAN, 1733

James Oglethorpe’s foundational plan for the capital of the Province of Georgia, Savannah, from 1733 is composed of an urban grid nested within a square-mile territorial grid, both grids based on a common beginning point on the bluffs of the Savannah River. Oglethorpe’s intention of providing a precise spatial framework for a limited society founded on agrarian equality was made possible through the use of the grid plan across scales, establishing set spatial relationships between groups of individual urban lots, garden lots, and field lots while accommodating the provision of civic amenities, common lands, and peripheral villages.4 Although intended as settlement with a limited size, the scalar grids have provided a framework for a much more nuanced and incremental process of city expansion through the 19th century following a unique compositional logic, free from dependence on any external reference or center .

Oglethorpe’s city plan is based on the repeatable unit of the Savannah Ward. The repetition of the unit of the ward in two directions produces a hierarchical grid system notable for its diversity of street types and regularity of open space. The urban grid remains open to expansion through repetition, growing from six to 24 similar wards by 1855. Later expansions no longer adhered to the ward plan, but retained their adherance to the square-mile territorial grid through a process of subdivision.

Along with its logic of growth through combination, the ward unit provides a guarantee of common open spaces in close proximity to individual lots, allowing for an increase in the building area of private lots and a resulting increase in urban density and activity. Each ward consists of a central square, four “tything” blocks of ten house lots each and four “trust” lots reserved for the public buildings of the colony. The combination of wards produces an urban grid plan with a six-level hierarchy, allowing for a range of streets of different qualities within a close proximity. Traced to the right is the ideal regional grid of Oglethorpe’s plan, composed of 56 plots measuring one mile square, providing a regular framework for the distribution of town, commons, gardens, farms, villages, and infrastructure.

IDEAL PLAN OF SAVANNAH, 1735

The town wards lie on the line of symmetry, surrounded by the commons, with the remaining space of the four plots reserved for gardens. The scalar system is calibrated on the measure of the tything block of an individual ward and a one-mile-square field plot, each organized into ten private lots with a common space at the center. Outside the garden plots are 24 field plats, corresponding to the 24 tything blocks of Savannah’s initial six wards, with plots reserved for individual townships beyond.

1000 0 N 5000m 1000 0 N 5000m SAVANNAH

KEY EPISODES 4 554 | Urban Grids: Handbook for Regular City Design

Hardoy).

Hardoy).

2.1.1 View of Santo Domingo by John Ogilby, 1671. (Facing page) Mapping of the five select models. The study could be expanded to include, among others, the bastides of King Edward I in northern Wales, the Florentine New Towns of the 14th century, the Nuevas Poblaciones de Andalucía y Sierra Morena of 18th-century Spain, the application and adaptation of Spanish, French, and British models across Africa, the Middle East, and

2.1.1 View of Santo Domingo by John Ogilby, 1671. (Facing page) Mapping of the five select models. The study could be expanded to include, among others, the bastides of King Edward I in northern Wales, the Florentine New Towns of the 14th century, the Nuevas Poblaciones de Andalucía y Sierra Morena of 18th-century Spain, the application and adaptation of Spanish, French, and British models across Africa, the Middle East, and

2.6.20 Painting by Jules Guérin for Daniel Bur nham and Edward Bennett’s Plan of Chicago from 1909, capturing a dramatic view over the proposed civic center, facing west.

2.6.20 Painting by Jules Guérin for Daniel Bur nham and Edward Bennett’s Plan of Chicago from 1909, capturing a dramatic view over the proposed civic center, facing west.