Warning

Members of Aboriginal communities are respectfully advised that some of the people mentioned in writing or depicted in photographs in the following pages have passed away. All such mentions in this publication are with permission.

Unless otherwise noted, the Aboriginal words used in this publication have been standardised, when possible, according to the relevant cultural authority

Avertissement

Les membres des communautés aborigènes sont respectueusement avisés que certaines des personnes mentionnées par écrit ou représentées sur les photos dans les pages suivantes sont décédées. Toutes les mentions et photographies de cette publication sont autorisées.

Sauf indication contraire, l’orthographe des mots aborigènes de cette publication a été normalisée d’après, si possible, l’autorité culturelle compétente.

Wamulu

Wamulu

inscrit dans le temps

Petitjean

& Arnaud Serval

8

: Project in Time 9

: un project

Georges

42 The Wamulu Project 43 Le projet Wamulu Bérengère Primat

64 Wamulu: a Contemporary Return 65 Le retour contemporain du Wamulu Howard Morphy 110 Artists’ Biographies 111 Biographies des artistes 116 Authors’ Biographies 117 Biographies des auteurs 120 Bibliography 120 Bibliographie 122 Acknowledgements 123 Remerciements Contents | Sommaire

Wamulu: Project in Time

Georges Petitjean

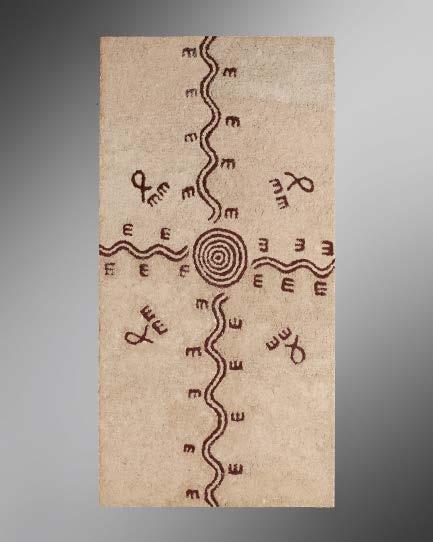

Between 2002 and 2005, an exceptional artistic project took place in the Central Desert of Australia, one that intended to make permanent a type of artwork that by its nature is impermanent and ephemeral. Ground paintings, an ancient form of art that goes back many thousands of years, are made for ceremonial purposes and are erased once a ritual or ceremony is completed. Never before had durable works of art been created using the same materials and techniques used in conventional ground paintings. A total of sixty-five Wamulu paintings on board were produced for the duration of the project. Wamulu, a yellow desert flower found abundantly in the Alice Springs region, is used as primary material for ground paintings or ground mosaics. After collection, the flowers are left to dry in the sun for several days and subse quently finely chopped into raw plant fibre pulp. The plant fibre is then mixed with pigment and a synthetic binder before being applied to boards onto which a preliminary design has first been painted. Rather than being applied via brushwork, the total image is built up with tufts of plant matter. The par ticular texture of the wamulu, somewhat reminiscent of cracked earth, has a haptic quality; it wants to be seen and felt.

As texture and colour are integral components of desert art, the tactile aspect is as important as the visual one. Designs correspond to major Dreamings in Central Australia.1

Arnaud Serval, a French collector, curator and art dealer, initiated the Wamulu project in 2002. From 27 June until 8 September of that year, an exhibition, Wati, les Hommes de Loi / The Law Men, organised by Serval, took place at the Passage de Retz in Paris. On this occasion, Ted Egan Jangala and Albie Morris Jampijinpa travelled to France and constructed a ground painting in situ. Serval asked Ted Egan Jangala, Johnny Possum Japaljarri and Albie Morris Jampijinpa whether wamulu could be applied onto a permanent sup port and exhibited. Although the suggestion was well received, they in turn

8

Wamulu: un projet inscrit dans le temps

Georges Petitjean

Un projet artistique exceptionnel s’est déroulé dans le désert d’Australie cen trale entre 2002 et 2005. Ce projet visait à rendre pérennes des peintures au sol qui sont par essence éphémères. Les peintures au sol, une forme d’art ancienne qui remonte à plusieurs milliers d’années, sont destinées à l’origine à des fins cérémonielles, puis effacées à la fin du rituel. Jamais auparavant, des œuvres d’art durables n’avaient été créées en utilisant le même matériau et technique que les peintures au sol conventionnelles. Soixante-cinq Wamulu au total ont été réalisés durant cette période.

Le wamulu est une fleur jaune du désert que l’on trouve en abondance dans la région d’Alice Springs, utilisée comme matériau premier pour les peintures ou mosaïques au sol. Après la collecte, les fleurs sont séchées au soleil pendant plusieurs jours puis finement hachées en une pulpe brute de fibres végétales.

La fibre végétale est ensuite mélangée à des pigments puis à un liant synthé tique avant d’être appliquée sur des panneaux en bois, sur une esquisse pré paratoire. Plutôt que d’être peinte, l’image est construite dans sa totalité avec des touffes de matière végétale. La texture particulière du wamulu rappelle un peu celle de la terre craquelée, elle possède une qualité haptique : celle d’être vue et ressentie. La texture et la couleur sont des composants essentiels de l’art du désert, l’aspect tactile étant aussi important que l’aspect visuel. Les motifs correspondent aux Rêves principaux de l’Australie centrale.1

L’initiateur du projet Wamulu en 2002 est Arnaud Serval, un collectionneur français, curateur et marchand d’art. Entre le 27 juin et le 8 septembre de la même année, Serval organisa une exposition Wati, les Hommes de Loi / The Law Men au Passage de Retz à Paris. À cette occasion, Ted Egan Jangala et Albie Morris Jampijinpa se rendirent en France et réalisèrent une peinture au sol in situ. Arnaud Serval demanda à Ted Egan Jangala, Johnny Possum Japaljarri et Albie Morris Jampijinpa si le wamulu pouvait être appliqué sur un support durable, puis exposé. Bien que la suggestion ait été bien perçue,

9

Most of the shields and paintings included in this publication have been created around the same period of time as the Wamulu

La plupart des boucliers et toiles de cette publication ont été fabriqués à la même période que les Wamulu mentionnés.

4. Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa (c. 1933–deceased) Decorated shield, unknown date Synthetic polymer paint on carved and shaped beanwood 72 x 22.5 cm

Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa (c. 1933–décédé) Bouclier décoré, date inconnue Peinture polymère synthétique sur bois de fer sculpté et façonné 72 x 22,5 cm

5. Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa (c. 1933–deceased)

Mount Wedge, Mount Ellen, Mount Denison, 1973 Acrylic on canvas board 61 x 77 cm

Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa (c. 1933–décédé) Mont Wedge, Mont Ellen, Mont Denison, 1973 Acrylique sur carton entoilé 61 x 77 cm

26 4

27 5

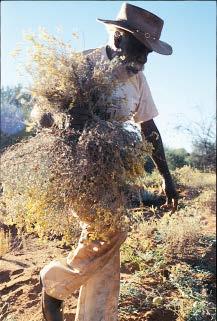

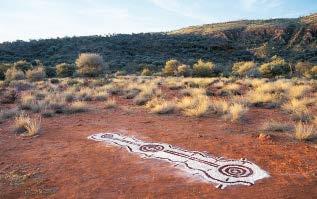

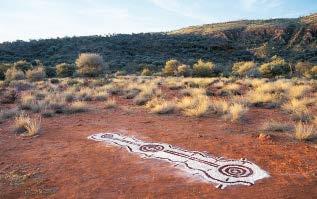

its specific location and prepare it with great care; they turn it into a pool table! It becomes a wonderful place. Every little twig, every tiny stone is removed. They rake, they flatten everything out. Then, water is poured to solidify the earth, so that it does not have the structure of red sand dust. Once the surface is ready, they start working on the Wamulu ground painting.

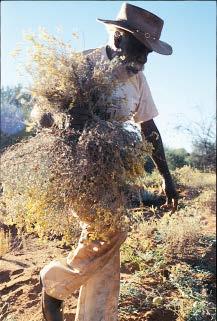

16. Dinny Nolan collecting wamulu around Alice Springs, 2002

Dinny Nolan récoltant du wamulu aux abords d’Alice Springs, 2002

44

16

17. 4WD full of wamulu after gathering, 2002

4x4 rempli de wamulu après la cueillette, 2002

17

BP : Peux-tu nous expliquer le procédé de création de ces œuvres en wamulu ?

AS : Quand une peinture en wamulu est réalisée, les Aborigènes choisissent l’endroit et le préparent, ils en font un billard ! Cela devient un endroit magni fique, chaque petite brindille est enlevée, chaque petit caillou est retiré, ils passent le râteau, ils aplatissent tout. Puis, ils mettent de l’eau sur la terre pour la solidifier, que ce ne soit pas juste du sable rouge en poussière ; et donc, sur cette surface préparée, ils réalisent l’œuvre en wamulu

Nous avons ramené des mètres cubes et des mètres cubes de fleurs. Nous les laissions sécher au soleil pendant deux ou trois jours. Ensuite, tout le wamulu était haché très finement.

Puis, toute cette matière était tamisée pour enlever les petites branches, les petites brindilles et ne garder que la feuille et la fleur du wamulu devenu aussi doux que du coton.

C’est un processus qui prend beaucoup de temps et, pendant toutes les étapes, ils chantent en permanence les chants de cérémonie pour donner vie à ces œuvres. Le wamulu est une plante sacrée, donc tous les chants, tous les rites existent autour de cette plante-là.

Quand les Aborigènes peignent leurs Dreamings (Rêves), ils chantent toujours les songlines (pistes de chants) de ce qu’ils sont en train de peindre. Ils ne peuvent pas créer sans chanter le parcours de l’ancêtre : soit ils chantent dans leur tête, soit ils chantent à voix haute ; mais ils chantent régulièrement pen dant qu’ils réalisent les œuvres. Et encore aujourd’hui, lorsqu’ils réalisent des tableaux à l’acrylique, ils chantent toujours les histoires qui leur sont liées. Je

45

Wamulu: a Contemporary

Howard Morphy

Wamulu — textured pigment-soaked material made from plant fibre or down — has been used throughout Central Australia for millennia as a major medium of body decoration, to cover sacred objects in designs, and in pro ducing ceremonial ground sculptures.

The museum label “mixed-media” reflects the diversity of art practices in which the forms of objects refuse singular categorisations. Designs in Central Australian art exist independently of particular media. They are a manifestation and product of the actions of ancestral beings in the landscape, designs that were then inherited by the human beings who followed them in occupying the land. Central Australian artists were always adept at using inherited designs to create works of almost any scale in many different media. The same design might appear engraved on a small wooden object, be painted on a ceremonial board or occupy the central space of a ceremonial ground. The ability to tran scend limitations of scale is reflected in the modern acrylic painting tradition in which original small canvas boards were rapidly transformed into large can vases by Uta Uta Tjangala and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, gigantic paintings from Yuendumu and Michael Nelson Jagamara’s parliamentary mosaic.

The Wamulu works produced collaboratively by Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa, Johnny Possum Japaljarri, Ted Egan Jangala and Albie Morris Jampijinpa exem plify this creativity and the adaptation of form to context. They are transpositions of ground sculptures — in their technique and form — onto a surface that enables them to be seen on a gallery wall. At the opening exhibition in the Annandale Galleries in Sydney in 2005 they were set in place by a ground sculpture.

Ground Sculptures – A Pan-Australian Form

Ground sculptures are important features of Aboriginal religious perfor mances across Australia. In many societies the sculptures demarcate an

64

Return

Le retour contemporain du Wamulu

Howard Morphy

Fabriqué à partir de fibres végétales ou de duvet imprégnés de pigments, le wamulu est un matériau que les Aborigènes du Désert central utilisent depuis des millénaires pour décorer la peau et les objets sacrés et pour pro duire des sculptures cérémonielles à même le sol.

Les musées font souvent usage des termes de « techniques mixtes » ou de « matériaux composites » pour désigner ces pratiques artistiques très diverses, comme le wamulu, qui résistent aux catégorisations trop uniformes.

Les motifs propres aux œuvres d’Australie centrale existent toutefois indé pendamment des matériaux utilisés. Créés par les êtres ancestraux en se déplaçant dans le paysage, ces motifs, qui manifestent leurs pouvoirs, ont été légués aux êtres humains qui leur ont succédé. Les artistes du Désert central ont su créer à partir de cet héritage des œuvres utilisant une grande diversité de matériaux, de techniques et d’échelles. Le même motif peut être ainsi gravé sur un petit objet en bois, peint sur un panneau cérémoniel ou bien sculpté au centre d’un espace cérémoniel. Cette capacité à varier les échelles se retrouve dans la tradition moderne qu’est la peinture acrylique, où les petites toiles du début ont rapidement été remplacées par de grands formats, qu’il s’agisse des grands tableaux d’Uta Uta Tjangala et de Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, des gigantesques peintures de Yuendumu ou de la mosaïque de Michael Nelson Jagamara au Parlement australien.

Les œuvres en wamulu, réalisées de manière collaborative par Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa, Johnny Possum Japaljarri, Ted Egan Jangala et Albie Morris Jampijinpa, illustrent bien cette créativité et l’adaptation de la forme au contexte. Ces œuvres sont des transpositions de sculptures au sol, avec leurs techniques et leurs formes propres, sur une surface leur permettant d’être accrochées aux murs d’une salle d’exposition. Pour l’exposition inau gurale en 2005 à la galerie Annandale de Sydney, une sculpture au sol venait compléter et contextualiser l’ensemble.

65

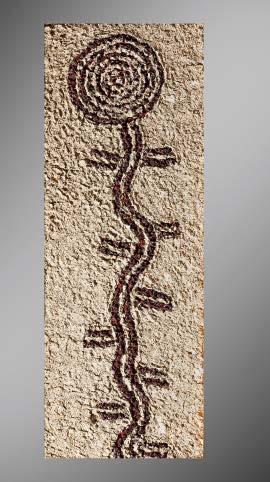

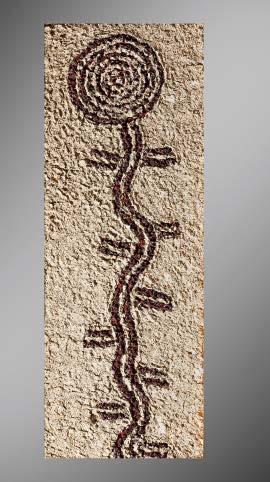

42. Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa (c. 1933–deceased) Mikanji / Water Dreaming at Mikanji, 2005

Natural ochres, wamulu vegetal fibres and binder on wood 122 x 45.5 cm

Dinny Nolan Tjampitjinpa (c. 1933–décédé) Mikanji / Rêve Eau à Mikanji, 2005 Ocres naturelles, fibres végétales de wamulu et liant sur bois 122 x 45,5 cm

> Detail of artwork no. 42 Détail de l’œuvre no 42

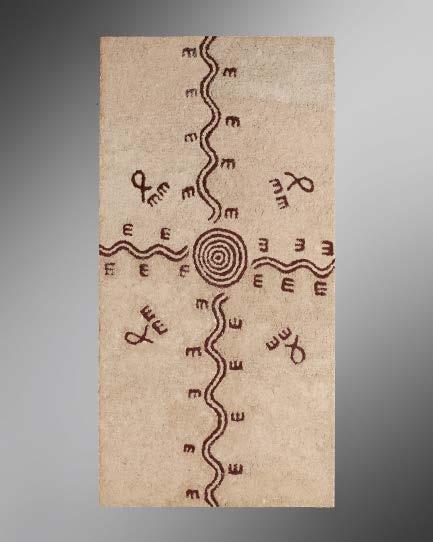

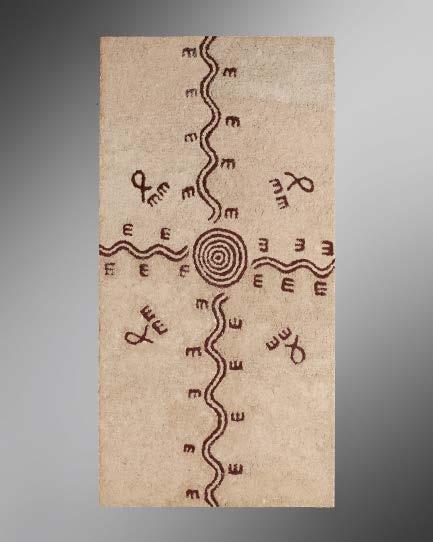

50. Johnny Possum Japaljarri (c. 1940–deceased) Janganpa / Possum Dreaming, 2005

Natural ochres, wamulu vegetal fibres and binder on wood 122 x 45 cm

Johnny Possum Japaljarri (c. 1940–décédé) Janganpa / Rêve Opossum, 2005

Ocres naturelles, fibres végétales de wamulu et liant sur bois 122 x 45 cm

51. Johnny Possum Japaljarri (c. 1940–deceased) Janganpa / Possum Dreaming, 2005

Natural ochres, wamulu vegetal fibres and binder on wood 244.5 x 122 cm

Collection Arnaud Serval Johnny Possum Japaljarri (c. 1940–décédé) Janganpa / Rêve Opossum, 2005

Ocres naturelles, fibres végétales de wamulu et liant sur bois 244,5 x 122 cm Collection Arnaud Serval

88

50

63. Unknown artist Karli / Boomerang, unknown date

Natural ochres on wood 82 x 7.5 cm

Artiste non identifié Karli / Boomerang date inconnue Ocres naturelles sur bois 82 x 7,5 cm

64. Unknown artist Karli / Boomerang, unknown date

Natural ochres on wood 81 x 7 cm

Artiste non identifié Karli / Boomerang date inconnue Ocres naturelles sur bois 81 x 7 cm

104

63

105 64

FONDATION OPALE

Series’s GAY’WU Production Production de la série GAY’WU Fondation Opale

Under the supervision of Sous la direction de Georges Petitjean, Bérengère Primat

THE PUBLICATION L’OUVRAGE

Authors Auteurs Howard Morphy, Georges Petitjean, Arnaud Serval (interviewed by interviewé par Bérengère Primat)

Editorial coordination and Proofreading Coordination éditoriale et Révision des textes Nathalie Bizart, Isabelle de le Court

Translation from English to French Traduction de l’anglais au français Lise Garond

5 CONTINENTS EDITIONS

Art direction Direction artistique Annarita De Sanctis

Editorial coordination Coordination éditoriale Aldo Carioli in collaboration with avec la collaboration de Lucia Moretti

Editing Secrétariat de rédaction Charles Gute, Olivier Godefroy

Colour separation Photogravure Pixel Studio, Bresso, Italy

All rights reserved Tous droits réservés – Fondation Opale. For the present edition Pour la présente édition © 2022 – 5 Continents Editions S.r.l.

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Le Code de la propriété intellectuelle interdit les copies ou reproductions destinées à une utilisation collective. Toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle faite par quelque procédé que ce soit, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit, est illicite et constitue une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles L.335-2 et suivants du Code de la propriété intellectuelle.

5 Continents Editions

Piazza Caiazzo 1 - 20124 Milan, Italy www.fivecontinentseditions.com

ISBN 978-88-7439-997-0

Distributed by ACC Art Books throughout the world, excluding Italy. Distributed in Italy and Switzerland by Messaggerie Libri S.p.A. Distribution en France et pays francophones BELLES LETTRES / Diffusion L’entreLivres

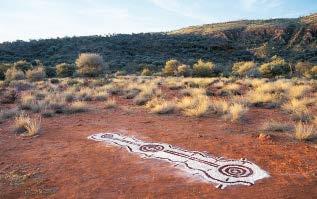

p. 8–9

West MacDonnell Ranges around Alice Springs Chaîne de montagnes de West MacDonnell aux abords d’Alice Springs

p. 124–125

Ground painting, 2002 (detail of the image on pages 62-63)

Peinture au sol, 2002 (détail de l’image aux pages 62-63)

Printed and bound in Italy in April 2022 by Tecnostampa – Pigini Group Printing Division, Loreto – Trevi for 5 Continents Editions, Milan Achevé d’imprimer en Italie sur les presses de Tecnostampa – Pigini Group Printing Division, Loreto – Trevi, pour le compte de 5 Continents Editions, Milan, en avril 2022