Real Cases. Real Experts. Real Science.

VOLUME 19 • NUMBER 3 • FALL 2010

Profiling Network Intrusions Combating Police Suicide Challenges in Operational Psychology Evil Minds Museum

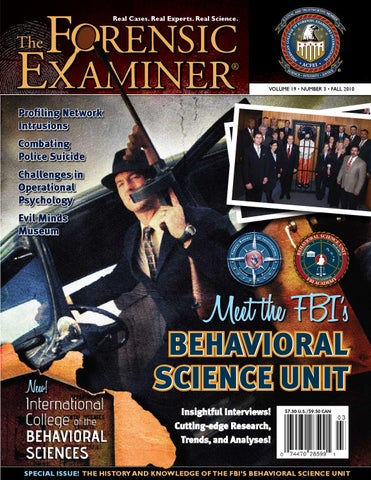

Meet the FBI’s

New!

BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE UNIT Insightful Interviews! Cutting-edge Research, Trends, and Analyses!

$7.50 U.S./$9.50 CAN

SPECIAL ISSUE! THE HISTORY AND KNOWLEDGE OF THE FBI’S BEHAVIORAL SCIENCE UNIT