January/February 2019

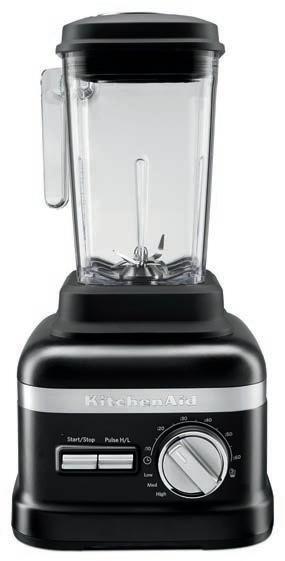

GET SERIOUS. IMMERSION BLENDERS 8-QUART STAND MIXERS COMMERCIAL BLENDERS Commercial Kitchens are tough environments even by our legendary standards. That’s why KitchenAid® Commercial was born. Now the brand you grew up using can grow with your business. KitchenAid Commercial equipment is NSF certified and designed for you to power your passion. ®/™ ©2018 All rights reserved. The design of the stand mixer is a trademark in the U.S. and elsewhere. SDO18302 2000 North M-63, Benton Harbor, MI 49022 PH: 855-845-9684 www.kitchenaidcommercial.com email: commercial@kitchenaid.com CONGRATULATIONS ACF ON 90 YEARS KEEP MIXING!

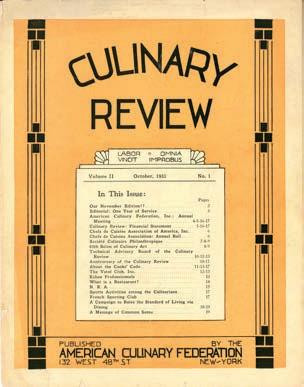

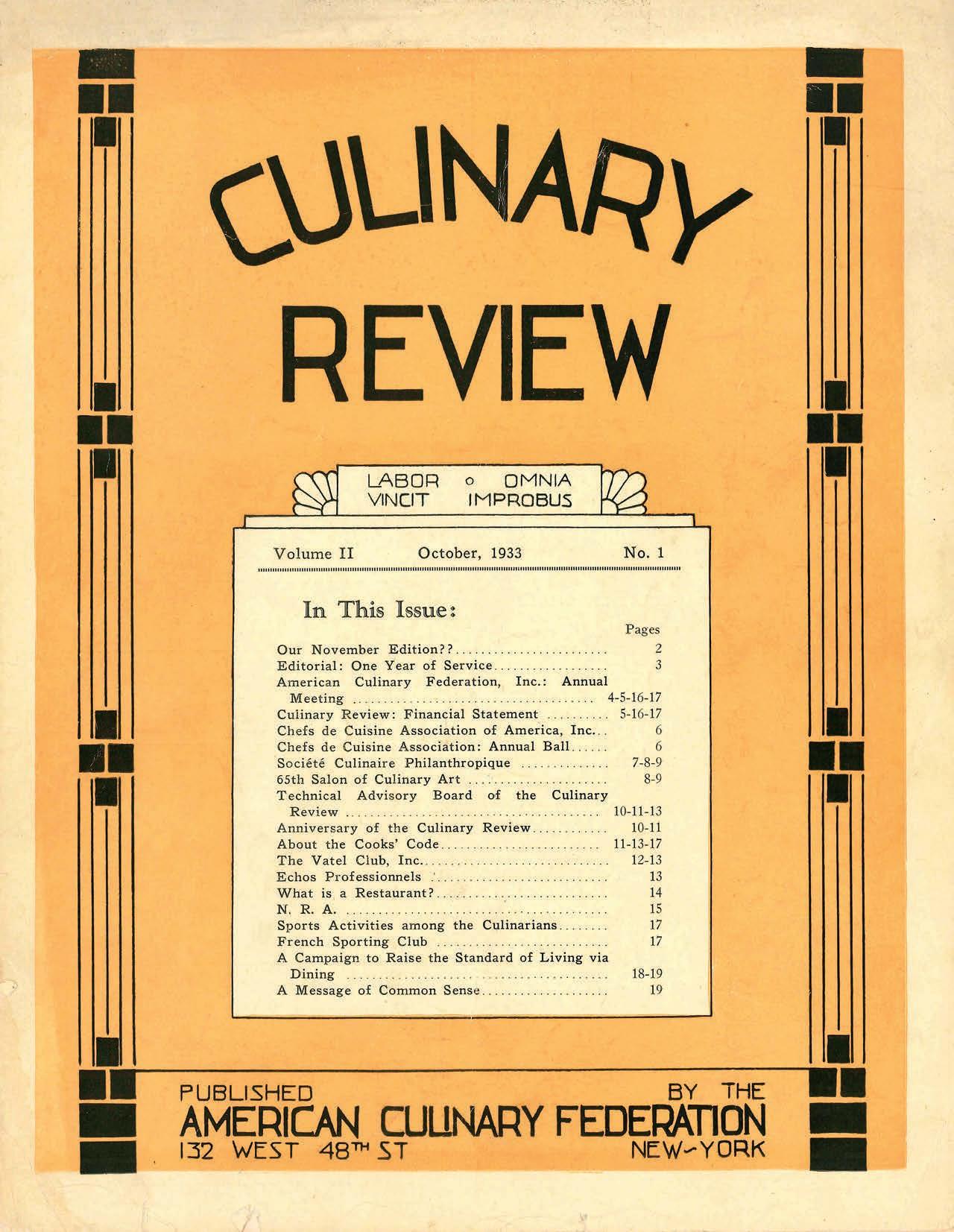

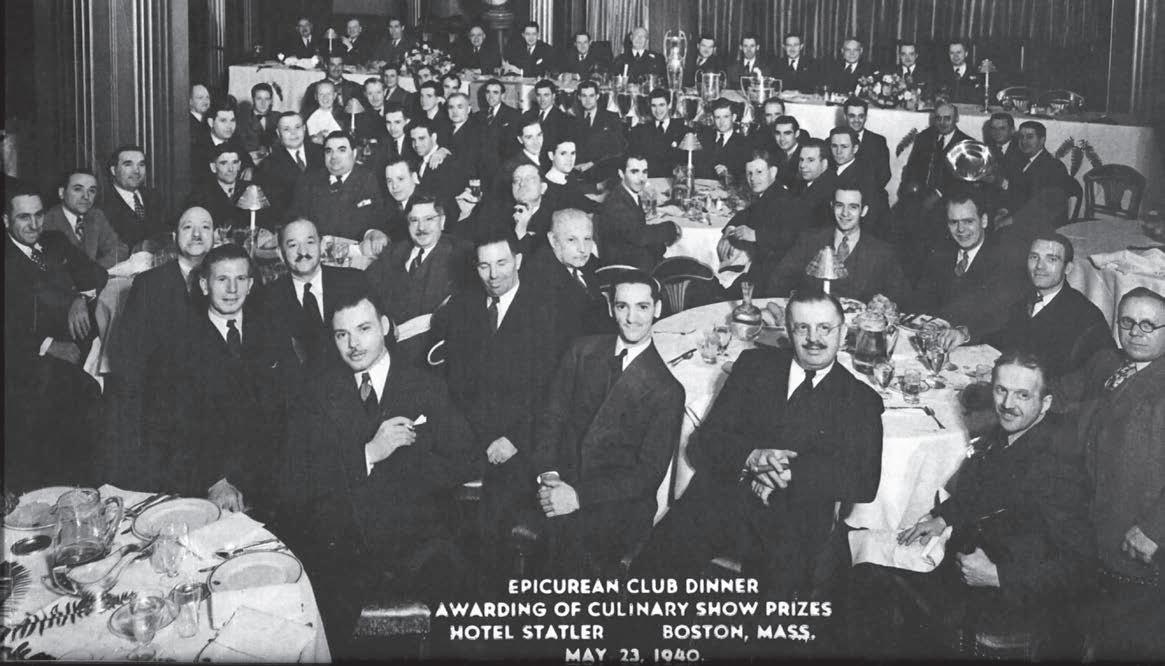

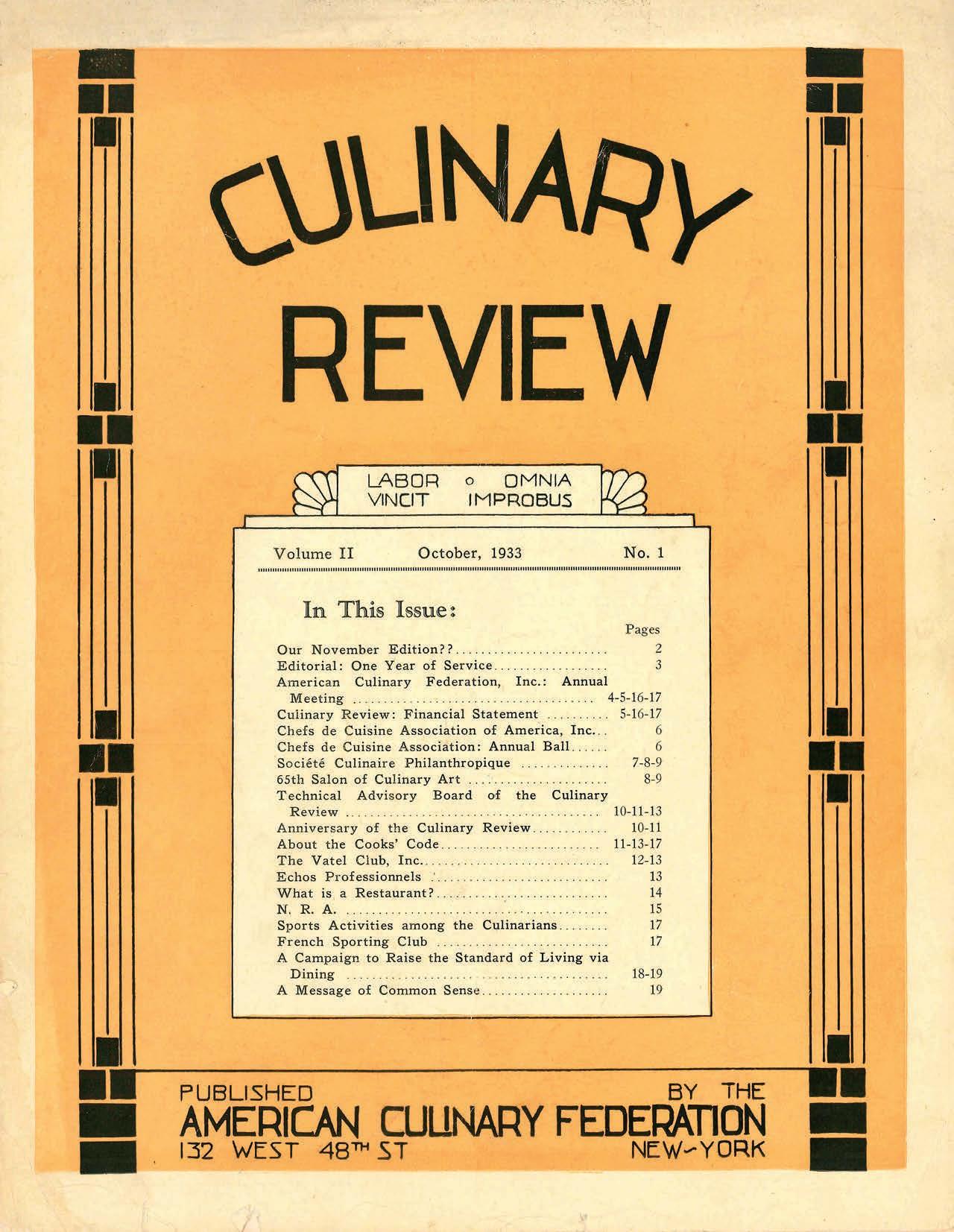

Published 180 Center PlaC e Way Florida AmericAn culinAry FederAtion by t he culinAry review nAtionAl Volume XLII No. 1 January/February, 2019 In This Issue: Pages President’s Message 4-5 On the Line 6 News Bites 8-11 Advocacy 12 Menu Trends 14-15 Food History 16-17 Restaurant History 18-20 Classical vs. Modern 22-23 Education 24-25 Feature: 90 Years of Excellence 26-33 Culinary Culture 36-37 Competitions 38-41 ChefConnect 2019 42-43 The Quiz 45 A Look Back 46 On the Cover: Roland Schaeffer, CEC®, AAC, HOF, Stafford Decambra, CEC®, CCE®, CCA®, AAC Sherry Gaynor, CEPC®, CCE® and Courtney “Birch” Moment at the Ice Plant Bar in St. Augustine, Florida. This page recreates the original cover of the October 1933 edition of the Culinary Review. To see the original visit page 31.

Editor in Chief

Jocelyn Tolbert

Creative Services Manager

David ristau

Assistant Editor

Heather Henderson

Graphic Designer

Kara Walter

Sales Specialist

Dave Merli

Director of Marketing and Communications

renee brust

american Culinary Federation, Inc.

180 Center Place Way St. Augustine, FL 32095 (800) 624-9458 (904) 824-4468 Fax: (904) 940-0741 ncr@acfchefs.net • www.acfchefs.org

board of Directors

President

Stafford DeCambra, CeC®, CCe®, CCa®, aaC

Immediate Past President

Thomas Macrina, CeC, CCa, aaC

National Secretary

Kyle richardson, CeC, CCe, aaC

National Treasurer

Christopher Donato, CeC, aaC

American Academy of Chefs Chair

Mark Wright, CeC, aaC

Vice President Central Region

brian Hardy, CeC, CCa, aaC

Vice President Northeast Region

Christopher neary, CeC, CCa, aaC

Vice President Southeast Region

Kimberly brock brown, CePC®, CCa, aaC

Vice President Western Region

Carlton brooks, CePC, CCe, aaC

Executive Director

Heidi Cramb

The National Culinary Review® (ISSn 0747-7716), January/February

2019, Volume 43, number 1, is owned by the american Culinary Federation, Inc. (aCF) and is produced 6 times a year by aCF, located at 180 Center Place Way, St. augustine, FL 32095. a digital subscription to the National Culinary Review® is included with aCF membership dues; print subscriptions are available to aCF members for $25 per year, domestic; nonmember subscriptions are $40. Material from the National Culinary Review®, in whole or in part, may not be reproduced without written permission. all views and opinions expressed in the National Culinary Review® are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the officers or members of aCF. Changes of mailing address should be sent to aCF’s national office: 180 Center Place Way, St. augustine, FL 32095; (800) 624-9458; Fax (904) 940-0741.

The National Culinary Review® is mailed and periodical postage is paid at St. augustine, Fla., and additional post offices.

POSTMaSTer: Send address changes to the National Culinary Review®, 180 Center Place Way, St. augustine, FL 32095.

looking Forward

When did the professional chef become a magician? I always hear from my fellow chefs that television, with its constant menu of competitions and unrealistic depictions of diva chefs who pull a lapin a la Bourguignonne out of a hat, has created a false impression of what it is we do every day.

While I agree to some extent — most chefs aren’t that dramatic — I would argue that television and the advent of the “celebrity” chef has simply revealed chefs as they really are: agents of transformation.

Are you really a different chef from Chef Charles Scotto? Do you care less about the food you craft than our original CMCs? Are our international competitors less skilled than the chefs that were on the 1964 Culinary Team USA?

The answer, of course, is no. Professional chefs are magicians but our talents are not fly-by-night tricks and theatrical sleight of hand. Our successes are the results of decades of commitment to culinary excellence in technique, skills and training, both on our own, in schools and with excellent mentors.

This year, the American Culinary Federation turns 90 years old. And in 2019, I believe we are entering the best years of our organization’s history. These pages show us the ways we’ve grown over the years but also provide a peek into what’s next. Online learning, can't-miss events, better communication — you’ve asked for these and this year, the ACF will deliver them all.

It’s not a magic formula. In the next few years, we are going to take the things we have always done best — education, networking and events and add that ingredient that only ACF has — you, our member chefs — and we will transform into something new.

In 1929, our founders saw that as an association, the organization was more than the sum of its parts — the individual chefs. In 2019, we acknowledge and celebrate what we’ve learned. We are better together and that’s the magic of the American Culinary Federation.

President

4 ncr | J anuary/February 2019

n

tional

a m erican Culinary

me at sdecambra@acfchefs.net or follow me on Facebook @stafforddecambra and Instagram @sdecambra

Stafford T. DeCambra, C

e C , CC e , C C a , aaC

a

Federation Contact

miramos Adelante

¿Cuándo fue que el chef profesional se convirtió en mago? Siempre escucho de mis colegas chefs que la televisión, con su menú constante de competencias y representaciones poco realistas de chefs estelares que sacan un lapin a la Bourguignonne de un sombrero, ha creado una falsa impresión de lo que hacemos todos los días.

Aunque estoy de acuerdo en cierta medida (la mayoría de los chefs no son tan dramáticos) diría que la televisión y el advenimiento del chef "famoso" simplemente han revelado a los chefs como lo que son realmente: agentes de transformación.

¿Acaso ustedes son realmente diferentes al chef Charles Scotto? ¿Les importa menos la comida que elaboran que nuestros CMC originales? ¿Acaso nuestros competidores internacionales son menos expertos que los chefs que formaban parte del Equipo Culinario de EE.UU. en 1964?

La respuesta, por supuesto, es no. Los chefs profesionales somos magos, pero nuestros talentos no consisten en trucos de vuelo nocturno y juegos de manos teatrales. Nuestros éxitos son el resultado de décadas de compromiso con la excelencia culinaria en materia de técnica, habilidades y capacitación, tanto por nuestra cuenta, en las escuelas y con excelentes mentores.

Este año, la American Culinary Federation cumple 90 años. Y creo que, en 2019, estaremos entrando en los mejores años de la historia de nuestra organización. Estas páginas muestran cómo hemos crecido a lo largo de los años, pero también nos permiten dar un vistazo a lo que está por venir. Aprendizaje en línea, programas para no perderse eventos, mejor comunicación: ustedes lo pidieron y, este año, ACF cumplirá.

No es una fórmula mágica. En los próximos años, vamos a tomar las cosas que siempre hemos hecho mejor: educación, redes y eventos, y agregaremos ese ingrediente que solo ACF tiene (ustedes, nuestros chefs miembros) para transformarnos en algo nuevo.

En 1929, nuestros fundadores vieron que, como asociación, la organización era más que la suma de sus partes: los chefs individuales. En 2019, reconocemos y celebramos lo que hemos aprendido. Estamos mejor juntos y esa es la magia de la American Culinary Federation.

dates to rem ember:

February 24-26, 2019

ChefConnect: Atlantic City

March 1-10, 2019

Certified Master Chef Exam Schoolcraft College, Livonia, Michigan

March 31-a p ril 2, 2019

ChefConnect: Minneapolis

au gust 4-8, 2019

ACF National Convention: Orlando

A list of 2019 ACF Regional Competitions is on page 41.

upcoming AcFApproved c om petitions:

January 22, 2019

Site: USC Hospitality Culinary Challenge

Chefs de Cuisine Association of California

March 15-16, 2019

Site: Dorsey Schools' Culinary Academy

Michigan Chefs de CuisineDorsey

For a full list of upcoming culinary competitions, visit acfchefs.org/competitions.

wearechefs COM 5 | President's Message | Un Mensaje Del Presidente |

Follow the ACF on your favorite social media platforms:

@acfchefs

@acfchefs

@acf_chefs

@acfchefs

Twitter question of the month:

We all know “hot behind” and “86’d.” What is your favorite bit of jargon that’s unique to your kitchen, and how did it come about?

Tweet us your answer with the hashtag #ACFasks and we’ll retweet our favorites.

Our favorite #acfchefs Instagram photo of the month:

National Culinary Review subscribers now have access to a brandnew digital platform on which to read the magazine: wearechefs. com. There, readers will find many of the same articles as in the print version of NCR, plus additional content: recipes, related stories, bonus photos and more. Plus, We Are Chefs is now the home of the ACF’s digital publication for culinary students, Sizzle, as well as the ACF blog — our home for industry news, content written by our member chefs and professional foodservice industry writers as well as announcements and breaking updates from the ACF. Members can read the digital magazine in its entirety by signing in at ncrdigital.com.

Need more CEHs?

Check out ACF’s new Online Learning Center . There you’ll find NCR quizzes, videos of educational sessions from ACF events, practice exams for certification and more. Read more on page 9 and visit learn.acfchefs.org to get started.

The Culinary Insider, the ACF’s bi-weekly newsletter, is a great source of timely information about events, certification, member discounts, the newest blog posts, competitions, contests and much more. Sign up at acfchefs.org/tci

6 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | On the Line |

Tag your Instagram photos with #acfchefs and you could see your image here in the next issue of NCR.

perfection requires

A LITTLE CONCENTRATION

Filled with the savory tastes of roasted vegetables, sautéed onions and select herbs, Minor’s® Flavor Concentrates add rich, distinct flavor to your soups, sauces and sandwiches. Choose from a variety of Classic or Latin blends, then stir into your hot or cold recipes to easily elevate flavor without the added step of cooking.

Flavor Integrity | Versatility | Ease & Consistency

To learn more about Minor’s Flavor Concentrates, visit flavormeansbusiness.com or call a Minor’s Chef at 800.243.8822.

All trademarks are owned by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A., Vevey, Switzerland.

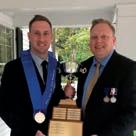

Culinary Team USA Brings

Home the Hardware

The Villeroy & Boch Culinary World Cup 2018 took place in Luxembourg at the end of November and ACF Team USA took home silver in both the cold buffet and hot kitchen portions of the competition. Team USA brought home a total of 18 silver medals and one bronze medal.

Congratulations to the competitors, coaches and managers, including: Gerald Ford, CMC; Andrew Chlebana, CEPC; Paul Kampff; Geoffrey Lanez, CEC; Jesus Olmedo; Timothy Recher, CEC; Thomas Haggerty, CCC; Vanessa Marquis, CEC; Reimund Pitz, CEC, CCE, AAC; Kevin Storm, CEC, CCA, AAC; Rene Marquis, CEC, CCE, CCA, AAC; John Coletta; Raimund Hofmeister, CMC, AAC; Gunther Heiland, CMPC, AAC; Thomas Macrina, CEC, CCA, AAC.

For a full list of competitors and support staff, including the members of Culinary Youth Team USA, Regional Team USA and Team Hawaii, as well as more photos from Luxembourg, visit wearechefs.com.

8 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | News Bites |

Educate Yourself

ACF is excited to announce the launch of an Online Learning Center with opportunities to enhance your skills, advance your career and maintain your ACF certification.

With ACF’s Online Learning Center, you can earn ACF-approved continuing education hours (CEHs) that are automatically uploaded to your member profile. Take online classes, quizzes and practice exams for the certification written exam all in one place.

Videos of select sessions from the ChefConnects and National Convention will also be available for purchase for those who were unable to attend in person. Registered attendees will receive credit to watch up to five recorded sessions from any of the three ACF events for additional CEHs.

Currently available:

• 30-hour Culinary Nutrition course

• 30-hour Introduction to Food Service course

• Beekeeping for the Executive Chef

• Preventing Discrimination in the Restaurant

• Certification written practice exams

• National Culinary Review quizzes

• Ingredient of the Month quizzes learn.acfchefs.org

Wisconsin Chefs Host Fundraiser for Students

Two chefs from the ACF Middle Wisconsin chapter organized a fundraiser dinner in Stevens Point, Wisconsin in the Fall. Chefs Jon Hardin and Fred Griesbach, CEC, AAC, worked with a group of students from Lincoln High School in Wisconsin Rapids to prepare a meal for 100 guests. The dinner was held at Michele’s Restaurant, where Chef Hardin works as head chef. Their efforts raised more than $3,000 for Lincoln High’s Family, Career, and Community Leaders of America and ProStart culinary arts programs. The philanthropic duo has put together many such fundraisers over the last several years to raise money for the Lincoln High School programs as well as for other charitable organizations like Operation Bootstrap, a local program in Stevens Point, WI that provides food, clothing, shelter, and other assistance to those in need.

Read this!

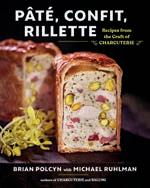

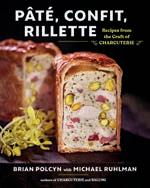

Pâté, Confit, Rillette: Recipes from the Craft of Charcuterie (W. W. Norton & Company, 2019),

By Brian Polcyn with Michael Ruhlman

By Brian Polcyn with Michael Ruhlman

At its heart, pâté is all about taking scraps of meat and fat that would otherwise go to waste and transforming these simple ingredients into a beautiful piece of charcuterie. From chefs Brian Polcyn and Michael Ruhlman (both speaking at ChefConnect: Atlantic City in February), the eight sections of "Pâté, Confit, Rillette" explore the ancient art of elevating livers, tongues and other less commonly utilized parts to exquisite and imaginative dishes. This book covers all of the fundamental techniques a chef needs to recreate its combination of timeless recipes and refreshing twists on old favorites and discover why this craft has persisted for centuries.

wearechefs COM 9

Are You Certified?

The ACF and NCR salute our newest certified chefs. For the full list, visit wearechefs.com.

We’re on a Mission

What has your chapter been up to? NCR is looking for amazing ACF chapters to highlight in a feature we’re calling Chapters On a Mission. If your chapter has done one or more of the following in the past year, we want to hear about it:

• Recruited a number of new members

• Maintained an active social media presence

• Provided unique educational experiences for your members

• Been a model for diversity

• Gotten involved with your community, supporting local charitable causes

• Mentored culinary students or young chefs

• Attended ACF events as a group

• Been exemplary ambassadors for the ACF and the culinary industry in another way

To submit your chapter’s story, visit bit.ly/ACFCOAM and fill out the form. Include as many great pictures and important details as you can. The deadline to be included in this year’s Chapters On a Mission is June 30.

Lyon's Share

On January 26-30, 3,000 exhibitors and brands and 200,000 hospitality professionals — including 25,000 chefs — will descend on Lyon, France for Sirha 2019. The event, organized every other year for more than three decades, presents all the news and trends in the world of foodservice.

“Over the years, Sirha has established itself as a unique trade show in the foodservice and hospitality industry and has become a major event for food professionals all over the world,” says Marie-Odile Fondeur, managing director of Sirha. “The most prestigious players in gastronomy today and tomorrow come to meet and exchange at the largest gathering of chefs on the planet.”

In addition, the finales of the prestigious Bocuse d’Or culinary competition, Coupe du Monde de la Pâtisserie and the International Catering Cup, as well as 18

more culinary contests, play out during Sirha. For this year’s Bocuse, 24 teams from five continents will compete in the finale in Lyon. The 2019 edition will be presided over by the winner of the previous edition, American Chef Mathew Peters.

Also on the menu during the event are three pop-up restaurant concepts; the Sirha Innovation Awards, which crown 12 innovations in the food service sector; the Sirha World Cuisine Summit, a series of roundtables and discussions with international players in the foodservice industry and more.

“Our mission is to offer the keys to understand a market that is increasingly complex and competitive, and to encourage technical innovation, creativity and growth for businesses in the food service and hospitality industry,” Fondeur says. “Sirha is where the foodservice industry and more broadly speaking the food habits of tomorrow are shaped.” sirha.com

10 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | News Bites |

Matt Livers, CEC

Mary Ybanez Ferrer, CEC

Thomas J. Frieling, CSC Almitra Williams, CSC

Tayler Redd, CSC Gregory Burton, CSC Erie Delos Reyes, CC Wayne G. Davis, CC

Bea Vang, CC Sadat Roach, CC Tracy J. Alexander, CC Angela J. Helton, CC

Bocuse d'Or 2017

Honoring Chef Christopher Neary

The American Culinary Federation, our members and the culinary community have lost of one of our finest leaders.

Chef Christopher J. Neary, CEC, CCA, AAC, current ACF Northeast Region Vice President, passed away on December 9, 2018. Rather than donations to a single charity, Chef Neary's family is encouraging chefs to continue to support charities of their choice.

Pressure Cooking

Salut!

The 2019 Certified Master Chef® (CMC®) exam could be your chance to achieve the highest level of certification a chef can earn. The intensive eight-day exam takes place March 1-10 at Schoolcraft College in Livonia, Michigan. Each day will bring new challenges to test candidates’ knowledge, skills, creativity and professionalism under pressure.

Just 72 chefs have ever passed this unique and rigorous exam. If you’re committed to your craft and think you have the necessary skills and stamina to perform at the highest standards, there are still spots open to register for this year’s exam. More information about how to register is available on acfchefs.org/certify

Congratulations to all of the ACF chefs who brought home awards from the Villeroy and Boch Culinary World Cup 2018, including: Vanessa Marquis, CEC, silver medal; Edward Castillo, CEC, silver medal; Peter Sproul, CEC, AAC, silver medal; James Storm, bronze medal; Robert Walljasper, CEC, CCE, bronze medal; Jeremy Abbey, CEC, CEPC, CCE, CCA, diploma. ACF is proud to have so many talented chefs dedicate their time and talent to compete at this level.

Aaron Bremer, CEC, is the subject of an article in Greater Fort Wayne Business Weekly by Linda Lipp. The article details Chef Bremer’s career path from dishwasher at his parents’ restaurant, Bob’s Restaurant in Woodburn, Indiana, to executive chef at Thermodyne Foodservice Products Inc.

The ACF Cleveland Chapter held its 58th annual Presidents Brunch at the Chagrin Valley Hunt Club in October. Chapter awards included Portage Country Club Executive Chef Jonathan Steele Pepera, CEC being selected as the Chef of the Year, Tony Stanislo of the Medina County Career Center receiving Chef Educator of the Year, and Minor’s received the Purveyor Partner of the Year. The chapter also awarded $4,000 in scholarships and one-year ACF memberships to local culinary students.

Last year, Minor’s challenged chefs nationwide to develop and submit original recipes for a chance to win over $25,000 in prizes. In November, the judges named Barry Greenberg, CEC, from Iowa City, Iowa, as the grand prize winner for his Carnita Tamale Tarts, an interpretation of tamal de cazuela. Chef Greenberg won $10,000 plus a trip to watch the prestigious Bocuse d’Or Culinary Competition in Lyon, France on January 29-30.

Gabriel Maldonado, CEC, CCA is the new executive chef at The Gasparilla Inn and Club in Boca Grande, Florida. Chef Maldonado, a member of the ACF Caxambas Chapter of Southwest Florida, previously held a position at New Canaan Country Club in New Canaan, Connecticut.

wearechefs COM 11

A Fair Deal by

Heather Schatz

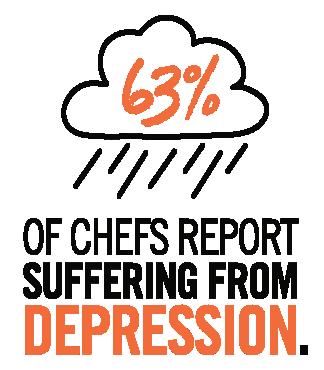

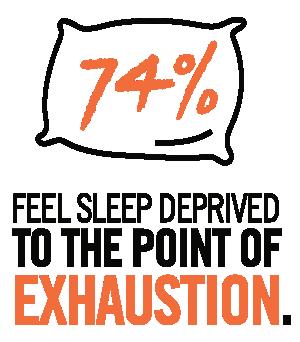

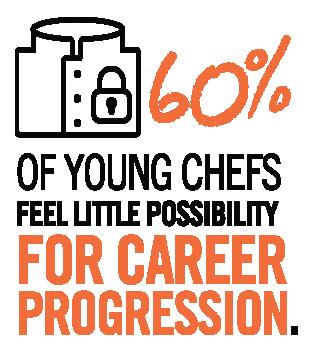

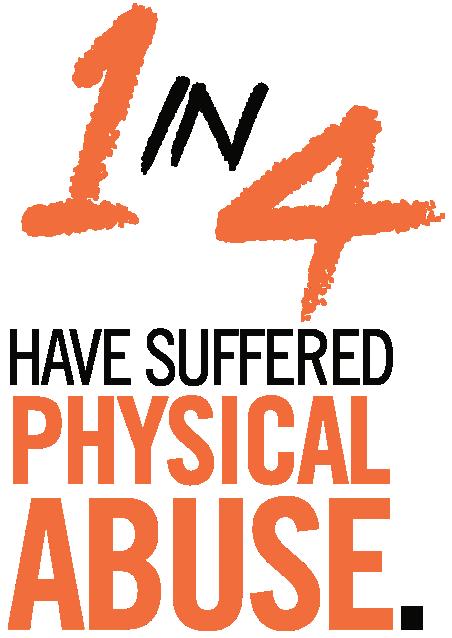

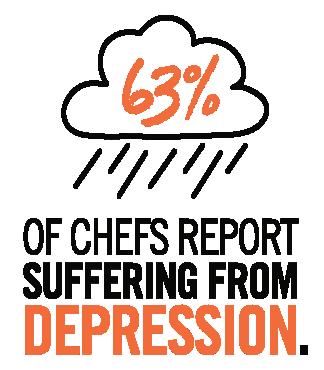

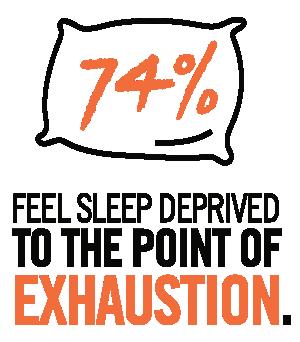

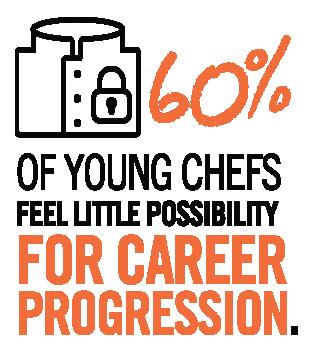

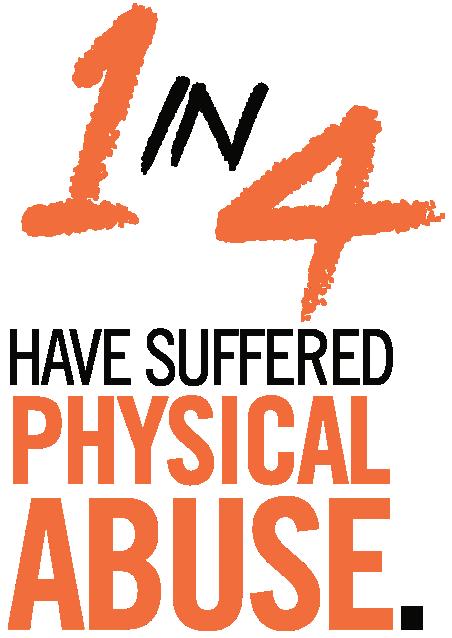

Our friends at Unilever Food Solutions recently launched FairKitchens, “a movement of chefs supporting chefs to inspire to a new kitchen culture.”

FairKitchens was created to identify and address several of the most serious issues plaguing our industry, and ultimately, help pave the way for a brighter future for everyone in it.

Prior to launching the movement, the Unilever Food Solutions team conducted research into why individuals leave the industry, and discovered that several factors — including a lack of sleep, nutrition and recognition — are having a serious impact on the well-being of chefs and service industry professionals.

“Chefs love what they do, but too often, pursuing their passion for cooking comes at a cost to their well-being,” says Chef Einav Gefen, Executive Chef at Unilever Food Solutions. “At times it often feels as though we, as the consumer, care more about the welfare of the chicken on our plate than the chef who has cooked it — this needs to change. We need to unite the industry by providing tangible solutions that

will lead to a change for good. We are creating the FairKitchens movement to inspire a new kitchen culture, championing chef well-being.”

To that end, the movement seeks to bring change to the industry in a variety of ways, such as training, support networks and events.

And that’s where the ACF comes in. We are currently working with the FairKitchens team to not only promote the movement, but also to help expand upon it, and hopefully help take it to the next level.

"We are excited to be a part of this unique movement, and are working hard to develop training materials and other educational content to support it,” says Jeremy Abbey, CEC, CEPC, CCE, CCA, ACF Director of Culinary Programs. “Many of us are aware of the struggles that occur in the hospitality industry, and the FairKitchens movement is an exciting path to help address these concerns and inspire change."

To read more about FairKitchens — including an interview with Chef Gefen — and ACF's work with the movement, visit wearechefs.com

12 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Advocacy |

Hot off the Press

Looking back at the n ational restaurant a ssociation’s annual What’s Hot survey reveals changing trends

by Jocelyn Tolbert

Since 2007, the National Restaurant Association (NRA) has surveyed American Culinary Federation chefs to get insight on the coming year’s culinary trends, and gathered the results in what’s now known as the What’s Hot Survey.

The first year, more than a thousand ACF chefs shared their opinions about which food and beverage trends were heating up and what trends are cooling off. Here’s what our chefs thought was “Hot” in 2007:

culinary concept trends. Full reports are released in early January, but we can guess what might be on it. For instance, items like locally-grown and organic produce have been perennial favorites, rarely leaving the top 20.

“Organic and local vegetables have become less of a trend and more of an everyday aspect of our lives. Vegetables are center of the plate material these days. The trend just keeps evolving and is mainstream now,” says Christopher Tanner, CEC, AAC, program director at Columbus Culinary Institute at Bradford School in Columbus, Ohio. “I went to a BBQ restaurant recently and was given the option of a smoked local carrot with Alabama BBQ sauce. What was once a specialty organic ingredient is now accessible to most anyone.”

Interestingly, in early incarnations of the now-12-year-old survey, chefs would include their thoughts on what trends were becoming passé. In 2007, that list was:

1. Scandinavian cuisine

2. Starfruit

3. Organ meats/sweetbreads

4. Ethiopian cuisine

5. Kiwi

6. Edible flowers/rose petals

7. Blackened items

8. Low-carb dough

9. Soda bread

10. Fruit soups

11. German cuisine

12. Taro

13. Low-carb items

14. Foams

15. Okra

16. Vichyssoise

17. Meat salad

18. Consomme

19. Catfish

20. Cold soups

Of course, trends come and go. Fads that were becoming passé in 2007 are coming back in more contemporary forms. Take “low carb items,” for instance. above: Cover of the NRA's What's Hot survey, 2007

For the 2019 report, the NRA polled 650 ACF chefs on food, beverage and

NATIONAL RESTAURANT ASSOCIATION NOT WHAT’S HOT WHAT’S AND RESTAURANT FOOD-ANDBEVERAGE TRENDS IN 2007 www.restaurant.org 14 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Menu Trends |

1. Bite-size desserts

Flatbread

Bottled water

Specialty sandwiches

Asian appetizers

Espresso/specialty coffees

Whole-grain bread 10. Mediterranean cuisine

Pan-seared items 12. Fresh herbs

Latin American cuisine

Exotic mushrooms

Salts

Grilled items

Pomegranates

Grass-fed items

Free-range items

Pan-Asian cuisine

2. Locally grown produce 3. Organic produce 4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

11.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

Dishes that reduce carbs by subbing in veggies — like mashed cauliflower and zucchini noodles — are now being seen on menus across the nation.

“Trends are not necessarily cyclical as much as they change and grow. If they don't grow then they die off as a fad. Many trends start at a high-level, accessible to a limited influential group. They then may grow to a culinary audience in magazines or cookbooks where the trend starts to blossom,” Tanner says. “Trends reports listed gochujang and açai repeatedly, but they never truly gained traction. Others are so unique that they will sit at a high-level with fine-dining chefs but never trickle their way down to the mainstream. For something truly to become mainstream, it must be accessible and not require a large amount of education for our consumers.”

Into the Drink

Though the full What’s Hot report wasn’t available by press time, preliminary results on beverages were released in early December. Some of the Association’s 2019 beverage findings include:

• Nearly 65 percent of respondents indicate that craft, artisan and locally produced spirits is the number one alcoholic beverage trend.

• Almost 60 percent of respondents said locally produced spirits, wine and beer would be among the hottest beverage choices in 2019.

More than 50 percent identified housebrewed beer as a hot trend.

On the non-alcoholic side, 51 percent said craft/house-roasted coffee would simmer over in 2019.

“At restaurants and other foodservice operations today, beverages, including wines, spirits, beers, and nonalcoholic drinks are big traffic drivers,” says Hudson Riehle, the NRA’s senior vice president of research. “Offering craft liquors, wines and other beverages allows restaurants to distinguish their drink programs from their competitors. At the same time, putting a more local, sustainable spin on beverages is particularly appealing to millennials, who, in general, are more apt to support smaller, different, more socially responsible businesses and products.”

wearechefs COM 15

Let Them e at Pie

by Lauren Kramer

One of the oldest recipes on the planet, pies have been a favorite dish since ancient Egyptian times. The Romans published the first pie recipe — a rye-crusted goat cheese and honey pie — but according to the American Pie Council, the earliest pies were mostly meat-based, with fruit pies gaining prominence in the 1500s. Back in those days, the pie crust was referred to as a “coffin,” a name that stuck when pies crossed the ocean to America with the first English settlers. It wasn’t until the American Revolution that the macabre reference was swapped for the term “crust,” which persists to this day.

Pies are a staple of American culture today, in both sweet and savory form. “I think everyone has a favorite pie, and many of us spend our lives chasing our childhood memories of our favorite pie,” says Dave Woodall, chef and co-owner of the restaurant Red Herring in Los Angeles. The reason for the endurance of this dish and the deep American love for it boils down to two words: fat and sugar. “Everyone loves the aroma of baked flour. It’s just a very comforting, familiar scent,” he says. “Add to that the human predilection for fat and sugar, and you have it dialed.”

Woodall bakes a pie a day, usually sweet dessert pies with a range of fillings that vary with the seasons: apples and orchard fruit in the fall, berries in the spring and nut or chocolate pies in the

heart of winter. “I believe more is more when it comes to pie, so we do big, towering, overstuffed monster pies at Red Herring.” The two secrets to a good pie lie in the ingredients and the technique, he says. “I’ll see people go for complex recipes without understanding the technique you need to make pie. They’ll overwork the dough until it gets tough and dry, they won’t bake the pie long enough or they’ll bake it at too high a temperature. Another oft-made error is not letting your filling rest before you fill your pie. When you do that you land up with soup in a crust!”

Red Herring goes through 60 slices of pie a week, and menued at $9 per slice, this dessert runs at a food cost of 30to-35 percent. “That’s above where you want to be for a commercial restaurant operation like ours, but we keep our pies on the menu because it’s something near and dear to my heart,” he explains. “I make the dish early in the morning to give the dough time to rest, and the process is meditative and wonderful.”

Woodall says chefs can recognize a good pie crust in one that barely holds together until it’s baked. He kneads his doughs by hand, freezing the butter and using a cheese grater to grate it into the dry base and deliver an even distribution. “The flakier the dough texture I’m aiming for, the larger the chunks of butter should be,” he says.

At the Mockingbird Restaurant in Nashville, Tennessee, Brian Riggenbach,

partner and executive chef says the eatery goes through “an ungodly amount” of its Bechamel chicken pot pie. Made with pearl onions, thyme and truffle butter on a homemade pie crust, the dish is on the menu year-round because, he says, “there’d be a mutiny if we tried to take it off!” Riggenbach makes a 40-quart batch of rich, flaky, buttery crust dough by hand every second day to ensure its freshness, and says the crust is the key to a successful dish. “This is such a sensory dish, and it requires a tangible feeling,” he explains. “Over time you learn to really feel it and it talks back to you — the dough and the way it all falls together.”

That sentiment is echoed by Tom Fleming, chef-owner of Crossroads Diner in Dallas, Texas, who makes two pies daily for his eatery: pecan pie, which is his long-time staple, and another seasonal sweet pie. As a pie judge at the State Fair of Texas for the past 21 years, he’s tasted more pies than he can remember.

“Thickness of the pie crust is key and over time great pie makers just know the right thickness,” he cautions. “For the custard it’s really the relationship between the syrup, butter and eggs that counts, as well as the ratio between filling and crust.”

For a good pie, there’s no room for cheap shortcuts like commercially prepared dough and fillings. “A lot of lackluster pies in the world are created when the labor is taken out of the equation and the pie becomes an afterthought,” Woodall says. The skill required to produce a remarkable pie takes endless practice and a deep understanding of consistency and texture. Only with this investment of time and attention to detail can you do justice to a universally loved dish that has so long endured.

16 n C r | J anuary/February 2019 | Food History |

Lauren Kramer, an award-winning writer based in Vancouver, british Columbia, is passionate about gourmet food and delights in tasting it and writing about it.

wearechefs COM 17

“I MAkE THE DISH EARLy IN THE MORNING… AND THE PROCESS IS meditative and wonderful .”

It’s Not Fancy But It’s Good

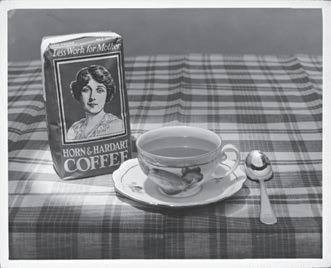

Horn & Hardart’s automat was a beacon of light during the Depression—and for consistencyobsessed restaurateurs who followed

by Karen Weisberg

by Karen Weisberg

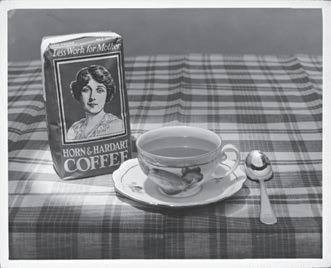

Baked beans, pumpkin pie, huckleberry pie, oatmeal cookies, cup custard, beef and noodles with burgundy sauce, hearty stews, fish cakes, “velvety” baked hams, macaroni and cheese, “succulent” Salisbury steaks, creamed spinach, the “fluffiest” mashed potatoes… “these are a few of their favorite things”... ‘cause for sure, every man, woman and child had a favorite. One can almost taste the memories of those lucky enough — or even those down on their luck — to have frequented one of the 84 Horn & Hardart Automats (automatic cafeterias with steam tables and waitstaff) that operated in the U.S. from July 1901 through April 1991. During the 1920s to the late 1950s, a cup of “gilt-edge” coffee there (dispensed through an elegant dolphin spout) was $.05; a slice of pie was $.10. A full meal cost less than $.50 in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Partners Frank Hardart in New York — he of the smooth, iconic French drip coffee that sold for a nickel for 38 years — and Joe Horn, a man whose gusto for substantial meals and Philadelphia were equally legendary, together created a restaurant chain that was successful and beloved beyond the sum of its New York and Philly parts.

Just before Christmas in 1888, the first Horn & Hardart Baking Company Lunch Room opened in Philadelphia. This was not an automat boasting a wall of gleaming glass door cubbies with slices of pie or sandwiches on view to be purchased for nickels inserted into slots.

No, this fledgling enterprise consisted of one long counter and 15 stools. Frank Hardart manned the kitchen and brewed his coffee while Joe Horn served and was earnestly attentive to each customer.

18 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Restaurant History |

n e w y ork Public

b

r us sell a s tor r eading r oom for r ar e b ooks and Manuscripts ( r obert F b yrnes c ollection), The n e w y ork Public Library

Photo credits: Left, The b uttolph collection of menus, The

Library; opposite, The

rooke

Upstairs/Downstairs

Eventually, four “automatic” units were imported from Germany. According to Marianne Hardart, Frank Hardart’s great-granddaughter, “The food inside the window was a display; a cook in the basement prepared the order, then cranked it up to the dining room on a dumbwaiter.” When it arrived, the guest had to insert a second coin to get the dish. “Cold food was already prepared but still had to be sent up from the basement.” In this way, “food appeared to be untouched by human hands and, with the discovery of bacteria in the 1880s, to be able to help yourself was a popular advertising ploy in the 1900s,” contends Alec Tristin Schuldiner, Ph.D, in his 2001 dissertation, “Trapped Behind the Automat: Technological Systems and The American Restaurant, 1902-1991.”

Tweaking the tech

Meanwhile, H&H’s chief engineer, John Fritsche, was laser-focused on “automatic vending.” He patented some 30 vending machines of various configurations, as Schuldiner details.

“In 1906, Fritsche filed for a patent on a ‘vending machine’ related to but distinctively different than the imported

automats; though a dumbwaiter system, Fritsche’s automat was specifically designed to vend pre-made servings via an unending chain of cells. His device could be kept chilled sufficiently to hold dishes of ice cream or custard … presenting a new cell when the available one was emptied.” With updates and tweaks made in 1911 — the year H&H expanded to NYC — this became the technology the company used for the following 80 years. It also served as a “solution” to the problem of labor. For accessing cold food, Fritsche’s design was like magic: “Make a selection, deposit a nickel, turn the knob and the door sprang open,” Marianne Hardart points out.

Consistency rules

Whether “chefs” played a substantial role at H&H in setting food prep standards as well as in the creation of standardized recipes remains debatable. What is certain is that Joe Horn was a stickler for setting and adhering to the highest quality standards regarding fresh meat, fish, vegetables, etc., purchased seasonally and often locally, for the commissaries. Marianne Hardart points to Horn’s introduction of the Sample Table, one in each of the two commissaries, as evidence he was determined to ensure that food was consistently produced up to standard.

wearechefs COM 19

opposite: 1958 Horn & Hardart menu above, from left: H&H Lunchette Exterior View, 1955; H&H exterior, cafeteria and retail Shop, 163 E. 86th St., New York, 1967

Once the menu item was prepared, it might be checked out at the Sample Table so changes could be made quickly. Every morning, company VIPs sampled random items. “One morning, a thousand gallons of soup were rejected for lacking a single ingredient,” Marianne Hardart notes in “The Automat, The History, Recipes and Allure of Horn & Hardart’s Masterpiece,” co-authored with Lorraine B. Diehl.

But the sine qua non was surely the “Managers’ Instruction Book.” The owners passionately cared that each and every one of the 400 menu items prepared twice daily in their commissaries met the exacting standards set out in the 200-plus page manual. Examples of entries include:

• Coffee: First draw and throw away about 2-oz. because coffee lying in the faucet absorbs a metallic flavor.

• Cakes: Display in rush periods; make up no more than six orders at a time to avoid stale product.

• Do not slice bananas in advance as they discolor rapidly.

During the Great Depression and for many years thereafter, the affordability of automat fare was a huge draw. “Joe Horn and Frank Hardart understood the importance of food that lingered in the memory while not emptying the wallets of the working people to whom the Automat catered,” Marianne Hardart says.

Truly, the commissaries were built to keep costs down, but over the years, they “allowed high standards to be maintained in 165 locations [including cafeterias,

automats and retail shops in NYC and Philly],” writes Valerie Wingfield of the New York Public Library in her 2010 article, “Before the Big Mac: Horn & Hardart Automats.”

Hail to the Chef

In 1933, a bona fide executive chef was brought on board. Francis Bourdon had trained at the Cordon Bleu in Paris and was previously employed at both The SherryNetherland and at The Plaza Hotel. His fellow chefs in the city are said to have teased him as being “L’Escoffier des Automats.”

“Bourdon advertised his skill to patrons via fanciful window displays of elaborate pastries and other feats of the chef’s art,” notes Lisa Hurwitz in her first feature documentary, “The Automat,” slated for completion in fall 2019. Meanwhile Shuldiner quotes Harvey Levenstein’s 1988 book “Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet”: “Horn & Hardart’s ability to hire such a highly trained chef was undoubtedly in part thanks to the fact that the restaurants of such upper class institutions ... were greatly diminished during the Prohibition Years [19201933], a setback from which they never recovered. While Bourdon was likely glad to have the job, he could not have given his skills free reign; though H&H is reputed to have offered particularly tasty food, it could not have strayed too far from the cafeteria norm.”

new york-based award-winning journalist Karen Weisberg has covered the issues and luminaries of the food-and-beverage world—both commercial and noncommercial—for more than 25 years.

20 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Restaurant History |

Photo credits: The b rooke r us sell a s tor r eading r oom for r ar e b ooks and Manuscripts ( r obert F b yrnes c ollection), The n e w y ork Public Library

Introducing the most exciting, inspiring foodservice trends of 2019! After scouring the globe for incredible flavors, analyzing consumer preferences and examining influential menus across channels, Custom Culinary® is proud to present ten trends we expect to make a major impact in the year ahead.

© 2018 Custom Culinary, Inc. All rights reserved. Check out the Custom Culinary® website each month for a deep dive into each of our 2019 trends! CUSTOMCULINARY.COM

EACH ISSUE, YOU’LL FIND:

IN

INSPIRATION,

BITE

CURVE. RECIPE VIDEOS INDUSTRY RESEARCH PRODUCT RECOMMENDATIONS TOOLS FOR ADAPTING THE TRENDS INTO SIGNATURE DISHES C M Y CM MY CY CMY K CCI18-0789 ACF ad-121018_fnl2.pdf 1 12/10/18 5:04 PM

A YEAR OF

ONE

AT A TIME SUBSCRIBE TO OUR DIGITAL NEWSLETTER AND STAY AHEAD OF THE CULINARY

Classical

A recipe for “Pollo en Piña - Caribbean Style Chicken in a Pineapple Boat” appeared in the October 1977 issue of the National Culinary Review (then called the Culinary Review). The recipe was written by Chef Gerhard Grimeissen, CEC, AAC, who at the time was the executive chef of the El Paso Country Club in Sacramento, California.

“When I first read the 1977 recipe, I was immediately transported to another place and time,” says Chef Hari Pulapaka, CEC, of Cress Restaurant in Deland, Florida.

The recipe’s quirky presentation and classic Caribbean flair — chicken dipped in egg and rolled in coconut, served with rice in half a hollowed-out pineapple — made it an irresistible candidate for a modern rewrite.

22 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Classical vs. Modern |

Modern

“I am always trying to respect the original intent and best features of a dish no matter how much or little I interpret it in my own way,” Pulapaka says. “For sure, most chefs [today] would find a different presentation than in the hollowed out pineapple. To me, it's a missed opportunity to reduce food waste. Furthermore, I subscribe to the adage that if it's on the plate, it should be edible.”

To create the modern version, Pulapaka grilled some of the pineapple and brought the chicken to the forefront with a crisp, roasted skin. “For this dish, so many familiar flavors come together, so I thought, why not really marry them all with a refined sauce,” he says. “Similar in concept and more diverse in enjoyment because depending on what bite you take, the experience can be different.”

See the classical and modern recipes, as well as the original page from the October 1977 issue of NCR, at wearechefs.com.

wearechefs COM 23

Photos by a gnes L opez

Culinary Education History: Still in the Making

Only after World War II with the founding of the first college dedicated to culinary as a profession did the U.S. visibly set out on its own culinary path. In 1946 the New Haven Restaurant Institute (now known as the Culinary Institute of America) opened in order to train World War II veterans in culinary arts.

Since the 1980s and ‘90s, the number of post-secondary culinary programs in the U.S. has grown from around 60 to more than 800, though the number is currently falling rapidly, says Kevin Clarke, CCE, JD (pictured below), director of culinary education for Colorado Mountain College, Breckenridge and Dillon, Colorado.

In addition to funding problems experienced by many private schools, unemployment in most states is below four percent. “When people have jobs, they don’t go to school,” says Michael Carmel, CEC, CCE (pictured opposite top), department head for culinary arts at Culinary Institute of Charleston and Trident Technical College, North Charleston, both in South Carolina.

By Jody Shee

Culinary school enrollment is down about 20 percent from five years ago, Clarke says. The TV star chef glamour bubble is wearing off. “Also, the Department of Education has been tweaking their student financial aid model based on earning potential after the individual graduates,” to the detriment of culinary school students. Additionally, “Graduates are saying, ‘If they hire me at $12 an hour after I go to school and pay the same $12 if I don’t go to school, why do I need to go?’”

Chosen culinary degrees are also changing with the times. Baking/pastry arts degrees have become more popular because graduates find they can become entrepreneurs without investing a lot of money — as in becoming cake decorators making $1,000 on weekends, Carmel says. Culinary jobs in healthcare and schools are asking chefs to get certified as dietetic managers, which is boosting culinary nutrition education. Meanwhile, research chef/culinology, which was a popular focus a decade ago, is waning as many culinary students lack the necessary math and science interest and skills.

Secondary Schools

Going forward, the pipeline for post-secondary culinary education (including apprenticeships) may be most aptly filled from secondary school vocational technical

24 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Education |

With the changing of times, culinary instruction of all types is undergoing a modernization revolution.

programs. This past July, Congress passed the Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century (Perkins V) Act — the latest reworking of the 1984 Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Technical Education Act. The act provides over $1 billion in federal support. Prior to the original legislation, the direction of vo-tech education came largely from the funding sources, says George Dennis, CEC, CCE, AAC (pictured below), hospitality instructor at Kent Career Technical Center, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The Department of Education instituted and funded the act to make sure young people could make a living from a trade. It continually seeks for and updates ways to develop professionals with necessary skills, Dennis says. The department thus identified career pathways and career clusters. The current eight classifications of instructional programs for culinary includes such careers as cooking and related culinary arts, baking and pastry arts, bartending, restaurant culinary and catering management and more.

Apprenticeships

Apprenticeships across career fields were collectively acknowledged and woven into the education fabric in 1937 with the passing of the National Apprenticeship Law. Though many hospitality properties developed their own culinary apprenticeship programs along the way, apprenticeships took a giant leap forward in 1974 when the American Culinary Federation (ACF) created a set of national guidelines for apprenticeship standards that served as a blueprint for other vocational secondary and postsecondary technical schools.

A broad sweep of changes is currently launching to address digital development, varying required hours for different career choices and a modernization of the 500 or so required skills, stepping away from the original European model setting French cooking as the standard, Clarke says.

The new three-step apprenticeship model allows students to select a 1,000-hour program leading to Certified Fundamentals Cook (CFC®) designation; a 2,000-hour program leading to Certified Culinarian (CC®); and a 4,000-hour program leading to Certified Sous Chef (CSC®) certification. Additionally, ACF's online Apprenticeship Portal launched this month, providing apprentices a way to digitally log their hours worked and skills competencies.

It’s not enough to know the five Mother Sauces anymore. “If you’re coming out of a 4,000-hour formal apprenticeship to become a sous chef, you should know how to make pho, sushi and other Asian cuisines as well as Mexican regional and South American, for example,” says Clarke. “They should learn to cook a steak and a few classic sauces, but also be able to do another six or eight styles of sauce that may be important for their region of the country.”

wearechefs COM 25

Jody Shee, a Kauai, Hawaii-based freelance writer and editor, previously was editor of a foodservice magazine. She has more than 20 years of food-writing experience and writes the blog www.sheefood.com.

90 Years of e xcellence

The aCF has represented and advocated for culinary professionals since 1929. b ut its roots have been growing for centuries.

by a na Kinkaid

by a na Kinkaid

26 ncr | J anuary/February 2019

wearechefs COM 27

today the job of chef is a recognized and respected profession, marked by the wearing of a towering toque and pristine white jacket, often emblazoned with the certifying emblem of the American Culinary Federation. Chefs appear on more than 150 televised food shows with eight out of ten Americans watching weekly. Culinary colleges and training programs abound, along with esteemed competitions and organizations such as the Internationale Kochkunst Ausstellung (IKA) and the supportive James Beard Foundation. Hardback cookbooks continue to sell in record numbers while other book publication formats decline. YouTube alone saw a 280-percent increase in viewership of food-focused videos in 2018 alone. Chefs today are acknowledged as creative artists, but are also working to change a host of social issues ranging from poor childhood diet to disaster relief. Restaurateur and Chef José Andrés may soon become the first chef to win the Nobel Peace Prize for preparing food for thousands of Puerto Ricans affected by Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Yet chefs were not always viewed so positively.

Hubert Schmieder (pictured left), AAC has been working in the culinary industry since 1943. Since that time he has seen the “culinary arts mushroom all over the world.”

“Today chefs can move beyond the kitchen — and they should,” he says. “That’s how chefs can change the world into a better place.”

Yet such was not always the case — especially in America.

There was a time when American chefs were considered only domestic servants who cooked, or worse, labored as slaves. Such presidential icons as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson did not hesitate to utilize slave cooks in their kitchens. New England’s colonial taverns offered a slightly more liberating alternative — most often with a proprietor’s wife serving the male customers and cooking at an open hearth fireplace.

During the 1800s, America grew and expanded, yet its culinary sophistication lagged far behind that of Europe. American chefs at that time were more like self-taught cooks, hard working but often lacking even the most basic professional culinary training. Standardized sanitary and safety guidelines did not exist. Kitchen procedures and discipline were either random or cruel, and sometimes both.

When America’s newly wealthy titans of industry traveled to Europe in the late 1800s, they marveled at the elegant hotels and smoothly running restaurants they encountered. The ease of service and creativity of cuisine they experienced there was the result of a venerated culinary tradition that stretched from Carême to Escoffier.

In short, they were impressed — very impressed. On returning home, many a wealthy industrialist with money to burn wanted to invest in building a grand European-style hotel complete with an

28 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | 90 Years of Excellence |

elegant kitchen. By the early 1900s, elite hotels were appearing in America’s major cities from coast to coast.

It soon became apparent that these grand hotel restaurants would need grand chefs if they were to match the legendary hotels of Europe. Offers went out to some of Europe’s leading chefs, with an enticing salary attached. Motivated by the chance to create anew, chefs began arriving in America, bringing with them the time-tested culinary standards and traditions of Europe.

In their new kitchens the chefs found the latest equipment (including the first ovens with a built-in heat regulator — American-made of course) and new ingredients, such as wild rice and cranberries, to explore. Yet they felt isolated. No single national organization or uniform professional standard linked the chefs in New York with the chefs in Chicago or San Francisco.

And there was another problem: the staff. Due to America’s rapid growth, there was no prevailing order or standard within the nation’s professional kitchens. Chefs found that if staff were trained

in-house, when a new staff member arrived, he would operate on his previous employers’ procedures. It was a mess that led to slow service, inconsistent food preparation, cost overruns, high staff turnover and work injuries.

Something had to be done.

At that time, New York City’s leading culinary associations, Chefs de Cuisine, the Société Culinaire Philanthropique and the Vatel Club, offered membership based solely on the chef’s nationality. As a result, French club members met only with other French chefs and the same was true for members of the Italian club.

Yet members within each club soon recognized the need for a more inclusive national society. That awareness soon led each club to pledge their support to the new organization, as well as $200 each to defray the initial costs of organizing the new Federation.

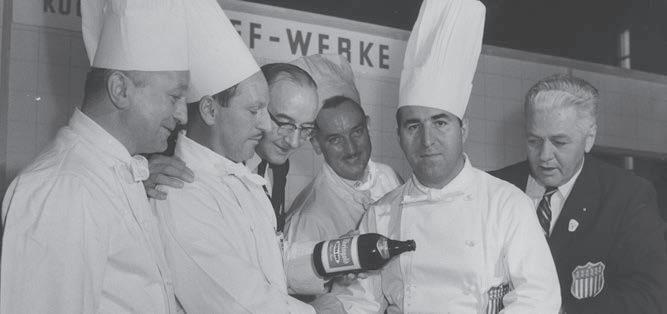

On May 20, 1929, New York’s leading European chefs, each representing their respective culinary associations — Louis Jousse, John Massironi, Charles Schillig, Rene Anjard, Joseph Donon, Louis Paquet, Charles Bournez, Charles Lepeltier and Charles Scotto (pictured right) — came together to form The

wearechefs COM 29

Previous spread: Shaina Clemons, Roland Schaeffer, CEC, AAC, HOF and Emilio Ramirez at the Ice Plant Bar in St. Augustine, Florida.

American Culinary Federation. Their intent was to create an organization that offered consistent professional training for incoming staff.

Not long afterwards, on October 29, 1929, a day forever known as “Black Tuesday,” the New York Stock Exchange dramatically collapsed. More than 16 million shares were traded in a panic selloff. By the first of December, the market had lost over $26 billion in value.

For many it was the financial end, but the chefs organizing the American Culinary Federation knew their organization would be needed more than ever as the newly unemployed would soon be flooding hotels and restaurants seeking work. They bravely pushed ahead and on January 14, 1930 the first officers were elected.

Charles Scotto was chosen as president. Louis Paquet and John Massironi accepted the role of vice presidents. Louis Jousse was elected as general secretary and Charles Schillig was elected as general treasurer. Scotto’s vital

stewardship of the Federation would last until his death in 1937.

Under his guidance, the American Culinary Federation, known to its many new members by its initials ACF, would shape American culinary history. They began with three guiding principles. First, they wanted to bring together “an elite body of cuisiniers” able to support each other and exchange information. Second, they wished to “foster cooperation between employers and the ACF.” Last, but not least, they pledged to “establish and supervise the training of cooks under a recognized professional association rather than by unqualified personnel.”

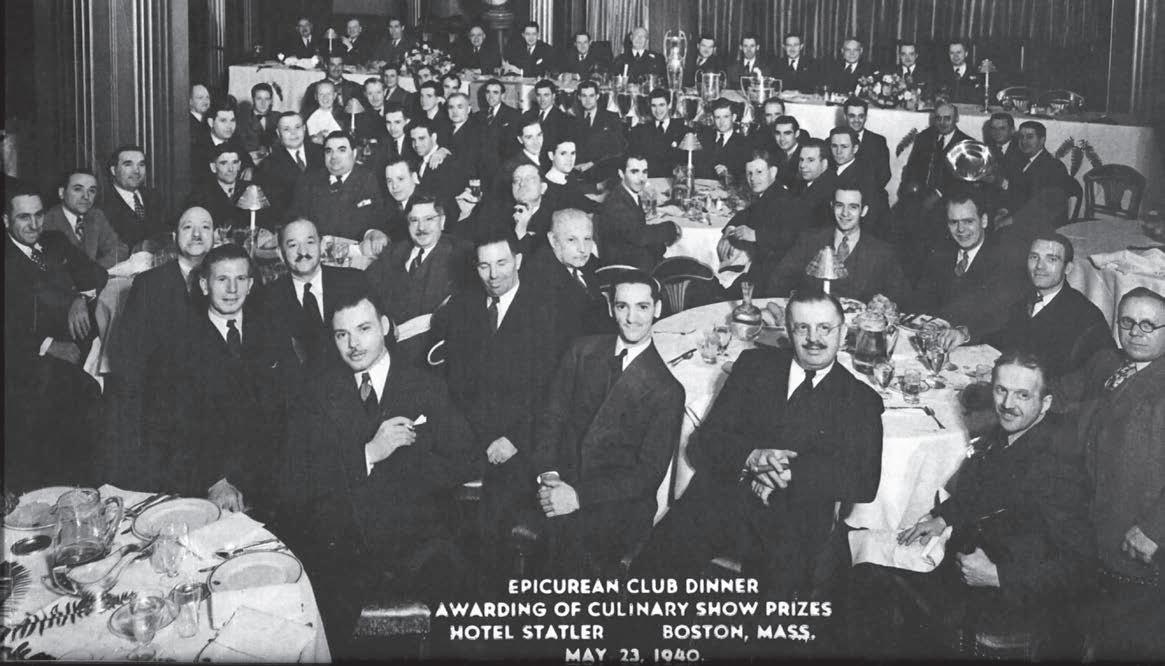

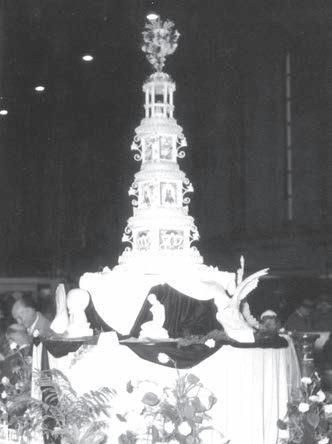

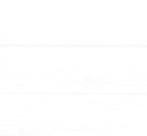

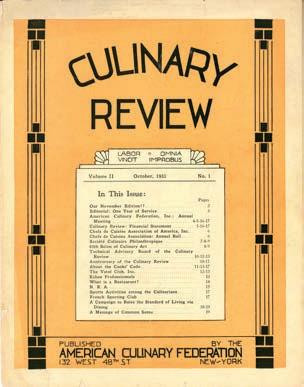

despite the social and economic upheaval caused by the Great Depression, the ACF took its first step above: Chefs at the second ACF convention in 1950. opposite, from top left: The cover of the second issue of the ACF's Culinary Review magazine; The six-foot wedding cake presented by the U.S. Culinary Team at the 1964 IKA

30 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | 90 Years of Excellence |

towards establishing universal culinary training standards in 1931 when it adapted the traditional apprenticeship program utilized by the Epicurean Club of Boston and chose Escoffier’s hallmark text “A Guide to Modern Cookery” as a proposed apprentice training manual.

Sadly history and war intervened and it would be 40 years before the organization would be able to fully implement a certified training program. The ensuing years, however, were full of many other accomplishments, ranging from the publication of a national culinary magazine to the recognition of pastry chefs as full Federation members and the establishment of an employment bureau for chefs.

During this period, the ACF also clarified that it was not a union, but an organization fully dedicated to the three original goals of fellowship, positive relations and professionally trained chefs.

World War II delayed the implementation of further new programs. Yet despite severe food restrictions due to wartime rationing in 1941-1944, ACF managed to send food

relief packages to those suffering in both the Asian and European theaters of war.

When the War ended in 1945, the American Culinary Federation was able to resume full activities. By 1946 ACF had grown to four national chapters and in 1950 the first national convention was held in New York City. In 1955 the American Academy of Chefs was formed by ACF to honor outstanding chef members. During this period, women chefs increasingly joined in Federation activities.

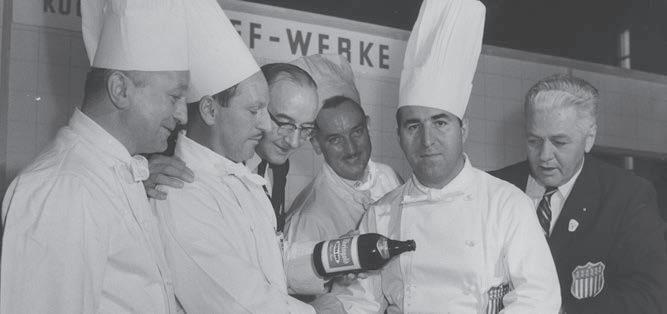

By 1956 the developing depth of the Federation’s membership enabled the Federation to field a team of top U.S. chefs to participate in one of the world’s most legendary culinary competitions, the Internationale Kochkunst Ausstellung (IKA) International Culinary Art Competition, for the first time.

Just four years later in 1960, the U.S. Culinary Team captured its first World Championship title at the IKA in Frankfurt. By 1964 ACF’s U.S. Culinary Team earned eight gold medals. This time ACF members and chefs traveled for the first time as a group to the Frankfurt competition to support and cheer on the U.S. team.

“Our show in Frankfurt [in 1964] was spectacular,” Chef Hubert Schmieder, a member of the 1964 U.S. Culinary Team, wrote in a piece titled “ACF Before the 1970s.” “We had a six-foot wedding cake that only Casey Sinkeldam could do, [President] Kennedy’s picture out of sugar cubes, the tallow sculptures from Richard

wearechefs COM 31

[Mack], the wild turkey platters from [Frederique] Bohrman, the 75 pounds of round beef from Otto [Schlecker], the gigantic lobster so old and so big we could hardly find a pot big enough to cook him in[. We] needed an electric carpenter’s drill to open his one-inch thick claws, and that’s hard to find at night in Frankfurt.”

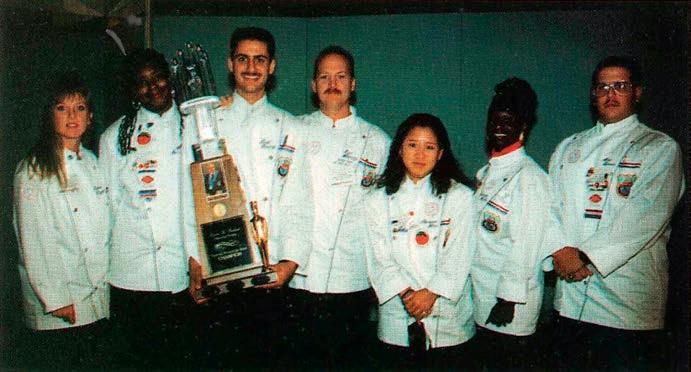

More victories came in 1980, 1984, and 1988 — setting the world record for the most consecutive wins — then again in 1992, 1996 and 2000 when the ACF accredited team shifted from classic European cuisine to dishes featuring eco-friendly ingredients and innovative plate presentations. During this same period Lyde Buchtenkirch became the first woman elected to the prestigious American Academy of Chefs and also became the first woman to be on an IKA competition team.

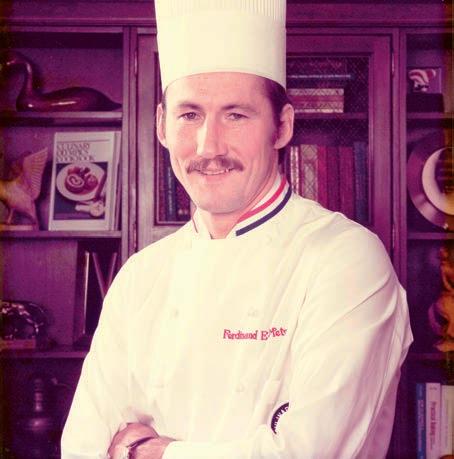

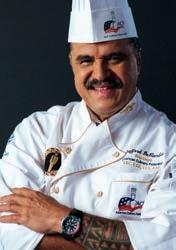

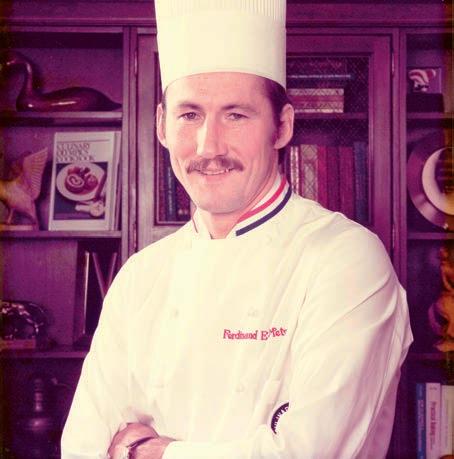

yet winning medals was not the only accomplishment of the Federation. In 1972 Ferdinand Metz, CMC, AAC, HOF and and Jack F. Braun, CEC, AAC, HOF developed the first ACF

Certification Program, actively supported by L. Edwin “Ed” Brown and Chef Wolfgang Von Dressler, AAC.

As a result of their efforts, a long-desired goal of the American Culinary Federation was finally achieved. The number of applicants for the first class was so overwhelming, only the 30 most qualified individuals were chosen, four of whom went on to become ACF national presidents.

“Certification has proven the single most important reason to join the American Culinary Federation,” Metz, who served as president of the ACF from 1979–1983 says. “[It] indicates both skill and commitment to the culinary profession.”

In 1977, due largely in part to the persistent efforts of the American Culinary Federation, the U.S. Department of Labor agreed to reclassify the role of chef from the generic Service occupational category of “domestic servant” to that of “chef” in the Professional, Technical and Managerial category. At long last, American chefs were accepted as skilled professionals.

“The American Culinary Federation worked long and hard to raise the position of chefs from that of a mere domestic servant to a skilled professional,” says Metz. “Because of ACF’s effort to upgrade the U.S. government’s culinary classification, cooking was no longer reserved for the lazy and the untrained. As a result, cooking became an acknowledged profession.”

32 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | 90 Years of Excellence |

in 1982 the organization opened its permanent offices in St. Augustine, Florida, (chosen because the city offered a free plot of land on which to build) and began growing in new and exciting ways. The ACF’s Chef & Child Foundation was formed in 1989 to promote proper nutrition in children. In 1992, the first Knowledge Bowl competition was held at the national convention in Washington, D.C. By 1998 chefs and food industry professionals around the world could follow the activities of the ACF on its new website. In 2001, the organization’s first five-year strategic plan was put forth. The ACF’s magazine for culinary students, Sizzle, was first printed in 2004.

In that same year, the training programs developed by the ACF received full academic certification and grew to offer certifications ranging from Certified Fundamentals Cook® (CFC®) to Certified Master Chef ®(CMC®) as well as Personal Certified Chef® (PCC®), Certified Pastry Culinarian® (CPC®), Certified Culinary Educator (CCE®) and many more.

“The certified chef gets hired first because the restaurant or hotel knows the ACF certified chef can really get the job done,” says Denise S. Graffeo, CEC, AAC, HOF, who in 2017 became the

first woman elected into the American Academy of Chefs Hall of Fame. “Certification leads to a supportive network, one able to last a lifetime.”

Today the American Culinary Federation continues its outreach to its over 15,000 members in 230 chapters through national conferences and an array of innovative programs such as The Chef & Child initiative, the Young Chefs Club, disaster relief, apprenticeships, scholarships and grants programs that affect the lives of millions of people throughout the nation and abroad.

Thanks to these beneficial programs and the ongoing efforts of The American Culinary Federation for these last 90 years, chefs today are viewed as valued professionals, admired for their creativity and trusted for their knowledge and skill. The years ahead promise more innovation and change as chefs address the emerging issues of sustainability, immigration, globalization, chronic hunger, disaster relief and human rights.

as a noted culinary historian, ana Kinkaid writes regularly for the aCF website, We are Chefs, and speaks to standingroom-only audiences at aCF national Conventions as well as at The Culinary Institute of america and Women Chefs and restaurateurs conferences.

wearechefs COM 33

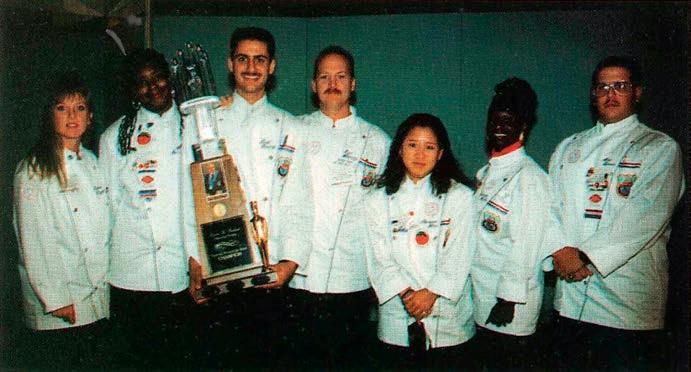

above: Los Angeles Trade Technical College team, the first Culinary Knowledge Bowl winners, 1992

Made from fresh, local milk gathered only a few hours after milking, BelGioioso Fresh Mozzarella, Burrata and Stracciatella begin with quality ingredients and care. The result is a delicate, clean-flavored Fresh Mozzarella with a soft texture and porcelain white appearance – the finest available on the market today

Available in waterpack tubs and cups, thermoform logs and balls, and slicing loaf.

belgioioso.com

OUR DIFFERENCE Fresh, Quality Milk

BelGioioso Burrata filled with Stracciatella

BelGioioso Fresh Mozzarella

new Stracciatella rBST Free* | Gluten Free | Vegetarian *No significant difference has been found in milk from cows treated with artificial hormones.

BelGioioso Stracciatella Tomato Appetizer

Try our

Let’s

A shining moment is not about to be interrupted by a spot. Your job is to create a great experience for your customers. Ours is to make sure clean dishware, flatware and glassware is the least of your concerns. Introducing the SMARTPOWER™ program — a safe, simple, sustainable warewashing solution. Learn more at ecolab.com/smartpower TM © 2017 Ecolab USA Inc. All rights reserved.

Shine.

Together

Past, Present, Future

How african-american cooking has intersected with mainstream american dining | by alan richman

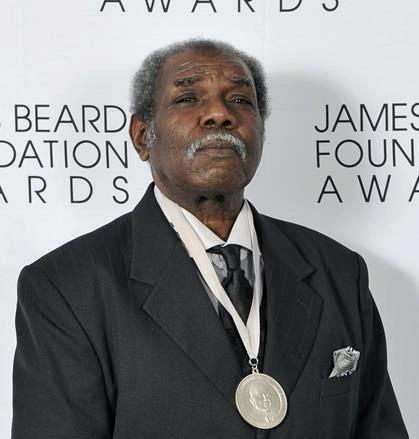

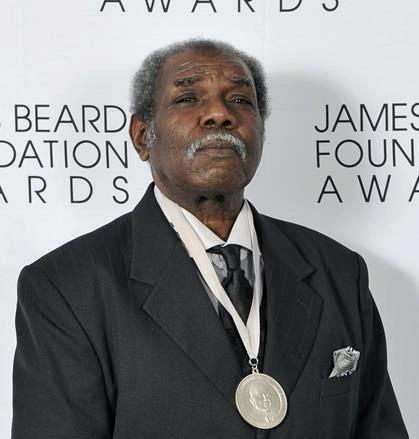

In 1910, Walter Jones opened what would become Jones Bar-B-Q Diner. Hubert Jones (pictured below), Walter’s son, used to refer to that early setup as “a hole in the wall, some iron pipes, a piece of fence wire and two pieces of tin.”

Hubert’s son James is now the owner and pitmaster of the Marianna, Arkansas restaurant, which is reputed as the nation’s longest running African-American eatery. Today, the diner is a two-table enterprise serving a community of about 4,100 people. Each morning at six, James, now 63, opens for business, preparing pork barbecue sandwiches soaked in a vinegar-based red sauce with coleslaw on Wonder Bread. At $3.50 apiece, this “value meal” is the only item on the eat-in menu. Take-home barbecue is sold at $7 a pound. Generally, Jones works alone, but his wife Betty lends a hand on weekends and holidays.

The place can get quite busy. Daniel Walker, a writer for the Arkansas Times , has warned readers: “On weekends, customers start picking up their pork as early as 7 a.m., and they often sell out by 10 a.m.”

Official recognition came to James and his predecessors in 2012, when he received the James Beard Foundation Award in the America’s Classics category. But accolades like that have come slowly — very slowly — for African Americans like Jones.

Laying the Groundwork

“When I was growing up, our family would eat out frequently — but never expensively — at Army & Lou’s on Chicago’s South Side. It was a blackowned soul food restaurant with black kitchen help, black servers and black customers. Only the linen tablecloths and the milk were white,” says Kimberly

Brock Brown, CEPC, CCA, AAC (pictured right), Vice President of the ACF Southeast region, a chef who pulls extra duty as an educator, speaker and mentor.

Seeing black people perform key functions emboldened Brock Brown to imagine a culinary career for herself. Over the past 30-plus years, following graduation from El Centro College in Dallas, she worked at a succession of kitchens across the Carolinas. She was featured pastry chef at the James Beard House in New York City in 1998 and started a wholesale specialty foods distributing company in 2008. The following year, she launched Culinary Concepts, LLC, which focuses on catering, demonstrations and special services.

“Slavery and then poverty made African-American cooks resourceful. Provided with no more than leftovers and sub-standard ingredients, they had to make use of everything — from the squeak to the tail,” she says. “This forced them to learn creative use of herbs, spices and flavorings in order to make dishes palatable.”

At 72, Savannah-based Joe Randall doesn’t stand over the stove as much as he used to, but still manages to keep busy as a chef, educator and owner/operator of the African-American Chefs Hall of Fame. Sometimes referred to as the “dean of Southern cuisine,” Randall worked at more than a dozen restaurants before parlaying his experience into faculty positions at four culinary institutions, including his own Chef Joe Randall’s Cooking School. Since early 2017, the school has been integrated with the Hall of Fame, which features such well-known inductees as Robert W. Lee, Leah Chase, Patrick Clark, Leon West and Edna Lewis, in addition to Randall himself.

36 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Culinary Culture |

Lewis, who died in 2006 at the age of 89, is particularly important, says Randall. The granddaughter of a former slave, she wrote cookbooks that, according to The New York Times, “revived the nearly forgotten genre of refined Southern cooking while offering a glimpse into African-American farm life in the early 20th century.” She is sometimes credited with helping to remove the stereotype of food south of the Mason-Dixon line being nothing more than fried chicken and cornpone.

certification system that helped elevate the professional status of all culinary employees, black and white alike.

Tell the People

A working chef for nearly three decades, an active member of ACF and a founding member of the Black Culinarian Alliance Corporation (BCA Global), Kevin Mitchell also is an educator who strives to be a role model for young kitchen personnel from minority groups.

Currently serving as chief instructor at the Culinary Institute of Charleston in North Charleston, South Carolina, Mitchell believes black people in the culinary industry need more exposure in such venues as the Food Network and Cooking Channel. He would like to see culinary schools devote more time to the contributions of people like Thomas Jefferson’s chef, James Hemming; the outstanding 19th century Charleston

Like Brock Brown, Randall emphasizes the need for black chefs in the 19th and early 20th centuries to make do with “whatever was available that day. Sometimes it would be rabbit, possum or squirrel.”

Meanwhile, status and recognition have remained elusive. Randall says that numerous cookbooks attributed to white female authors actually reflected work being done by black kitchen staff. “Not all blacks were able to read and write; in fact, laws prohibited teaching slaves how to read,” he says.

An off and on member of ACF since the 1970s, Randall says the organization was instrumental in establishing a

caterer Nat Fuller; Pullman train cooks and culinary mentors like Darryl Evans and culinary stars like Patrick Clark.

"Knowing the culinary history is inspiring. It helps me when I want to encourage other culinarians about this path," says Brock Brown. "AfricanAmerican chefs are cooking in just about every genre, 24/7, 365 days of the year. We have to meet people where they are. Show successful minority chefs who look like them to help encourage and inspire them."

alan richman, former editor/associate publisher of Whole Foods Magazine, is a new Jersey-based freelance writer focusing on food and nutrition. Contact at arkr@comcast.net.

wearechefs COM 37

“SL AVERY ANd THEN POVERTY m A dE A FRICAN-AmERICAN CO OKS resourceFul .”

Clash of the Titans

Culinary competitions push chefs

by rob benes

Culinary competitions play a vital role in culinary arts as they continually raise the standards of culinary excellence.

“Competitions are a way to see if your approach to cooking is relevant with current foodservice trends,” says Staff Sgt. Sarah Deckert-Perry, a military chef at Fort Campbell, Tennessee, who has been involved in competitions since 2000 and has won upward of 25 medals. “Lots of times cooking competitions showcase current cooking trends, as well as new ingredients, methods, techniques and presentation styles.”

While many countries have a more static approach to menu development, American chefs have long provided a melting pot of creativity toward food. When Americans began competing as an official team in 1956, they were clearly the underdogs. However, American cookery soon established itself as worldclass cuisine, and American chefs distinguished themselves at the Internationale Kochkunst Ausstellung (IKA) International Culinary Exhibition, commonly known as the “culinary Olympics,” as well as at other international competitions.

“A chef can say anything they want to say about themselves, but a culinary competition puts you against other chefs who are judged on the same criteria. This is how you really tell how good you are as a chef,” says Hubert Schmieder, AAC, chef emeritus at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, who won an individual gold medal in the 1960 IKA, was a member of the US Culinary Team at the 1964 IKA and helped charter planes to bring ACF Culinary Team to IKA in 1964, 1968 and 1972.

Competitions also encourage networking and a sharing of techniques, processes and products. “Competitions are an

outlet for chefs to demonstrate their craftsmanship at a higher level compared to what they do on a day-to-day basis in their restaurant and share that knowledge with others,” says Chief Warrant Officer Joseph Wisniewski, CEC, CCE, Joint Culinary Training Exercise (JCTE) Advanced Culinary Chief, and Team Manager of U.S. Army Culinary Arts Team (USACAT), Fort Lee, Virginia.

Competitions can play a role in student education, too, but experts say it shouldn’t be a focal point. “I prefer a student that wants to learn how to cook first and foremost. Too many students think that by entering competitions it will get them fame and fortune. This is not true. The numerous cooking shows on television are giving the wrong impression about cooking competitions and how to prepare flavorful food that’s consistent,” says Ferdinand Metz, CMC, who leads two consulting companies, Ferdinand Metz Culinary Innovations and Master Chefs’ Institute, both in Temecula, California, and who was ACF’s culinary team manager and captain from 1976 to 1988.

Internationale Kochkunst Ausstellung (IKA)/Culinary Olympics

The IKA is a quadrennial chef competition with more than 1,500 chefs from more than 50 countries. The exhibition had been held in Erfurt, Germany, but in 2020 it will relocate to Stuttgart, Germany.

The United States has participated in the Culinary Olympics since 1956. The 1960 U.S. team captured the first world championship honor and repeated the distinction in 1980, 1984 and 1988 by taking the hot-food competition and establishing a new world record for the most consecutive gold-medal wins. In 2004, ACF

38 ncr | J anuary/February 2019 | Competitions |

to demonstrate their knowledge and skills in a competitive format.

Culinary National Team USA won the hot-food championship with one of only four gold medals given and finished third overall. In 2008, the national team again won gold in the hot kitchen, for the first back-to-back gold medals since 1980. The ACF regional team won the overall world championship title in the regional category. At the 2012 IKA, ACF Culinary National Team USA won a silver medal in cold-food presentation — only one gold medal was awarded — and a silver medal in the hot-food kitchen, placing sixth overall. At the last IKA in 2016, ACF Culinary Team USA earned the top score and the overall gold medal in culinary art in the cold-food competition. Overall, the team ranked fourth in the world among 30 national teams and brought home three gold medals.

“Not all chefs are great competitors, but the skills that lead to success in competition are valuable to all chefs,” says ACF Culinary Team USA team manager Reimund Pitz, CEC, CCE, AAC. “In assembling a Culinary Team USA, we look for culinarians who demonstrate consummate skill and creativity, the ability to work as part of a team and a fierce dedication to the craft.”

At the 2020 IKA/Culinary Olympics, there will be a new set of standards regarding international cooking competitions. The exhibition of cold platters has always been one of the major attractions of the event, but, starting in 2020, the exhibition of cold platters will now be replaced by a Chef’s Table, which will allow visitors to sit right in the kitchen of the national teams and enjoy their meal. At the 2016 IKA/Culinary Olympics, the junior national teams exhibited an “Edible Buffet” instead of a cold platter.

In addition to the competition rules changing, teams must adapt to new cooking trends. “We utilize processes, techniques and training methods that

have worked in past competitions with a modern approach to the food. For example, taking the classic Duchess Potatoes and using sweet potatoes instead of russet and adjusting the flavor profile with different seasonings,” says Gerald “Jerry” Ford, CMC, team captain, Culinary Team USA, and executive chef, The Ford Plantation, Richmond Hill, Georgia.

Joseph Leonardi, CMC, director of culinary operations, The Country Club, Brookline, Massachusetts, was part of ACF Culinary Team USA from 2005 to 2016 and 2009 ACF Chef of the Year. He has seen today’s competition standards raise the bar because of European influence on food. “Years ago, it was straight fundamental cooking. Then it

wearechefs COM 39

top: ACF Culinary Team USA 1960, left to right: Charles daniel, Charles Finance, Paul Laesecke, Edmond Kasper, Tony Achermann, William Schmitz bottom: ACF Culinary Team USA 1980

changed into molecular cooking. Now, it seems cooking is a combination of strong cooking fundamentals with European influence,” he says.

“The biggest change in competition has been a move to more functionality instead of details in items that might not be practical to replicate for 50 people on the cold food display,” says Alison Murphy, pastry chef, Martis Camp Lodge and Golf Course, Truckee, California, who was ACF Pastry Chef of the Year 2013 and was on ACF Culinary Team USA in 2013 and 2014. “The criteria are moving toward preparing and presenting items that are foods that you’d do in real life.”

The goal of ACF Culinary Team USA is to compete in the Culinary Olympics, which is a three-year process and a tremendous time commitment for team members. The team meets monthly for a

compete but will strengthen your trade skill that will transfer to your job and career,” says Ford.