14 minute read

A Community of Lifelong Learners

by Janet Karvouniaris, Social Studies Alumna Faculty

Dedicated to Steve Medeiros, an educator of unique intelligence, character, and leadership

Irecently came across this question on ResearchGate, a platform for researchers to post their work, posit questions and respond to fellow researchers: “Caveat lector (Warning to reader): How do we distinguish “trolling” from critical thinking with the Socratic Method?” (Joseph Tham starting a discussion in Deliberation, June 2, 2020) I found this juxtaposition of trolling with the Socratic Method intriguing - the contemporary with the classic! And the role of critical thinking in connection with the former and the latter was very compelling. I am much more familiar with the Socratic Method than I am with the concept of “trolling”, so my first reflex was “Google it” and here is what I found:

In internet slang, a troll is a person who starts flame wars or upsets people on the Internet by posting inflammatory and digressive, extraneous, or off-topic messages in an online community (such as a newsgroup, forum, chat room, or blog) with the intent of provoking readers into displaying emotional responses and normalizing tangential discussion, either for the troll’s amusement or a specific gain. (Wikipedia)

The Internet, under any circumstances, is a seemingly limitless trove of information for the curious, lifelong learner, but…caution, critical thinking must be amply applied!

I have always believed that effective teachers see themselves as both teachers and learners, and that lifelong learning is a habit of mind developed where there is a predisposition and a growth mindset. When I retired from ACS Athens nearly five years ago, I continued to work with colleagues on Professional Development and Curriculum Development initiatives in areas where my experience and expertise could perhaps be of benefit. I have also stayed in contact with many former colleagues and students around the world through social media, pursued other areas of interest, read widely, and certainly become more proficient with the use of digital tools. My long career as a member of the vibrant ACS Athens learning community and the habits of mind I cultivated ensured that even in retirement, my own education was far from over!

When the Covid 19 pandemic forced school closings and ACS Athens had to make the transition to distance learning, I was not surprised, but impressed at how seamlessly the transition appeared to be. Not surprised, because the groundwork had been laid over a decade ago when the Humanities team designed and offered the very first blended course (2008), an online Humanities class with a 10-day Face to Face field study component, which served as a model for subsequent courses. By 2011 there were three online Humanities courses, each with a different interdisciplinary theme, making the Humanities interdisciplinary study experience available to a wider audience while maintaining the necessary F2F interaction among students and between students and teachers. We were able to begin a partnership with the Chapin School in New York.

With the introduction of the i²Flex paradigm under the expert guidance of Dr. Avgerinou, blended instructional design with online components that met international standards (QM©) became the norm. The emphasis on flexibility, student-centered guided instruction, and the use of a multitude of digital tools certainly prepared teachers and students alike to move toward the Virtual School. Moreover, constructivist educators willing to invest substantial time, take the calculated risks, and commit to an ongoing process of research and reflection in order to improve student learning were uniquely suited to facilitate a smooth transition.

The history of education in the digital age at ACS is one built on a tradition of creating unique programs tailored to a diverse student population, taking full advantage of the school’s location in Europe. So when the need arose for a holistic approach embracing academic, social, and emotional needs of individuals during a very stressful time, ACS was well-positioned

to fill the need. I am certain that, while this was exhilarating and rewarding, it has also been extremely stressful and exhausting for all involved!

The recent “Stay at Home” period due to the Covid 19 pandemic provided many opportunities, as well as challenges, for me. I found a complex of thoughts and feelings surface as my family navigated, seemingly blindfolded through new territory. By far, the most pervasive feeling was one of gratitude for many things I used to take for granted; health, food security, running water, family, and the comforts of home. Reflecting back on that period, I also realize that I was never bored because I was discovering new areas of interest and developing new practices. Thanks to technology, I was not isolated from my retired colleagues and friends at ACS Athens, and they continued to influence me toward further learning. I started a Qigong practice, completed a 1000 piece jigsaw puzzle depicting Renoir’s Dancing at the Moulin de La Galette (a painting I love from teaching Humanities all those years), and signed up for an online course called, Tangible Things: Discovering History Through Artworks, Artifacts, Scientific Specimens, and the Stuff Around You (EdX/ Harvard). I hadn’t taken an online course since I did the requisite training to teach TOK but this seemed perfect for me! The course was self-paced and I opted out of the certificate so…no pressure. I quickly recognized that the opportunities and limitations of conditions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic would change the way I approached the course.

I would like to share with the ACS Community of Lifelong Learners the way I addressed the final project for the course:

“Your final assignment is to develop an original interpretation of a physical object of your own choice. Your interpretation can be presented through writing, making another object, or helping to design and create an exhibit.

Regardless of the form it takes, your project should demonstrate an ability to look closely, connect broadly, and think critically.”

Due to the limitations of the “lockdown”, I chose to present by writing about an object I had at home – no access to museums or libraries! The result is Pythagoras Cup and the Greek Mind. Pythagoras’ Cup and the Greek Mind By Janet Karvouniaris

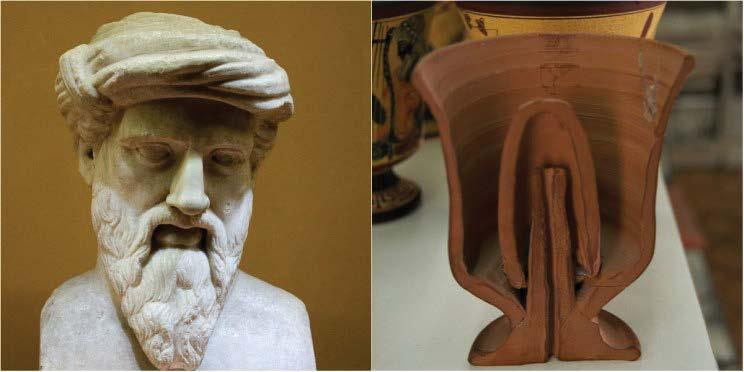

It is May 11, 2020, in Athens, the first day of opening public services, shops, and some schools, and the beginning of unrestricted movement since early March when measures were enacted to prevent the spread of Covid 19 and “flatten the curve”. (Greece has done a good job of keeping the pandemic at bay, although 151 people have died to date.) Museums, libraries, and archaeological sites are still closed, which limited my choice of a “tangible thing” for this investigation and meant that I would have to use my own library and digital tools for research. Consequently, I chose a museum replica of Pythagora’s cup that I had purchased from the museum shop in the Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Greek Technology. This small, rich interactive museum contains exhibits from a whole range of technology including: The automatic theaters of ancient Greece, clocks, mythical automatics of ancient Greece, the inventions of Archimedes, elevating mechanisms, hydraulic technology, measuring instruments, telecommunications, astronomical measuring tools, siege, textile, agricultural and medical technologies, flight machines, sport and nautical technologies, toys and musical instruments, geometric kinetic mechanisms of ancient Greece, and the automatic servant of Philon-the first operating robot known to humans!

The museum collection represents a unique feature of ancient Greek civilization which is what HDF Kitto called, “a sense of wholeness of things.” Unlike the modern mind, which tends to divide, specialize and think in categories, the Greek instinct was the opposite, to take a wide view and see things as an organic whole (Kitto, p. 169). The Greeks have an untranslatable word, ‘sophrosyne’ (Σωφροσύνη) which expresses this unity of the intellectual and moral virtues. We might think of sophrosyne today as a sound, open mind and excellence of character, which leads to other virtuous qualities such as; self-control, prudence, decorum, and the ability to think critically outside of the boundaries of specific disciplines.

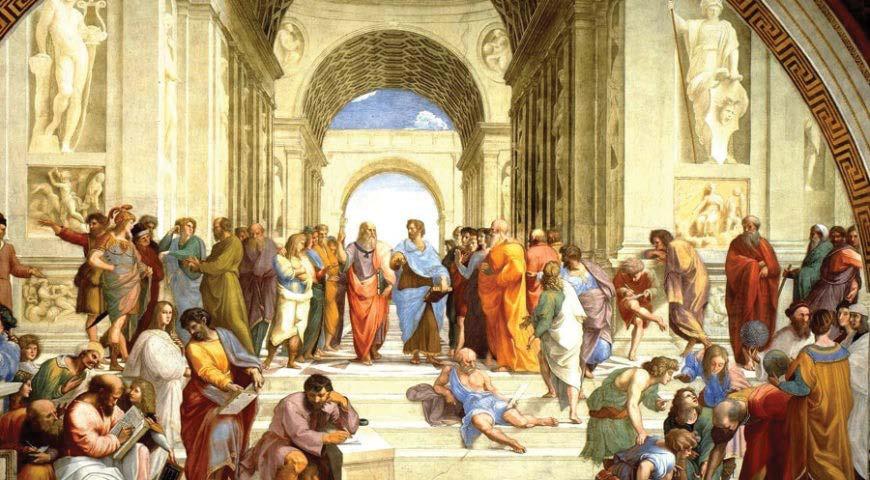

Many of the well-known Greeks of the ancient world were many things at once, what would later be described as “Renaissance men”, and today as “well-rounded individuals”. Solon, for example, was a political and economic reformer, businessman and poet. Pythagoras was a philosopher, mathematician, and inventor who developed theories of mathematics and music, nature and the universe- BIG, BROAD

ideas! He is on Plato’s side with the abstract, philosophical thinkers, and poets in Raphael’s fresco, The School of Athens (created in 1510, Vatican Library, Rome).

“On either side of Plato or Aristotle are the main thinkers of the classical world. The philosophers, poets, and abstract thinkers are allied on Plato’s side. The physical scientists and more empirical thinkers are on the side of Aristotle. Only a few of the ancient thinkers in the School of Athens can be identified definitely. One of whom is one of Plato’s masters, the Greek mathematician Pythagoras. Here he is demonstrating his theory that ultimate reality consists of numbers and harmonic ratios.” In my view, Pythagoras’ ingenious wine cup represents this unity of the ancient Greek mind. From careful study of this artifact, we can glean much about the “wholeness of things” in ancient Greece, as we are guided by The scientific principle behind the “trick”, the moral lesson he intended his students to learn about moderation - Παν μέτρον άριστον- the beautiof a handmade, practical object meant for daily use. My first encounter with Pythagora’s cup was about 18 months ago when I attended a STEM Fair at the Technopolis venue in Athens, which is the former gasworks plant of Athens, established in 1857 to light the city of Athens. It is now a major cultural center for all types of artistic, scientific, and cultural events. The fair was wonderful and surprising in many ways-there were students from primary grades through university who explained/demonstrated their own inventions, performed, and hosted exhibits of their work connecting a variety of disciplines. Visitors could browse, stop, and talk with the students and even make things of their own. A small group of middle school girls from a Greek public school were demonstrating the scientific principles behind Pythagora’s cup and showing interested visitors how to make their own from a plastic cup and a straw. Their enthusiasm for their “work” was remarkable and hooked me into spending more time than I expected with them.

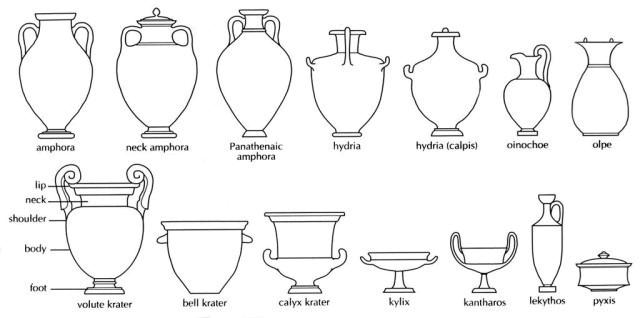

I had never seen this object in a museum (only a demonstration of the “tricky” siphon principle) and I have been to MANY museums in Greece, but since Pythagoras (ca.570-ca. 490 BCE) was from Samos, these cups can be found in the museum there. They can also be found at the “mother of all souvenir shops” near Monastiraki Square, I discovered. They come in a variety of colors and styles but are always the same simple *krater shape and make great gifts for friends who are interested in wine, ancient Greek art and history, and, of course, STEM education. Now, with this project, I had an opportunity to take a closer look at this object and delve deeper into its significance.

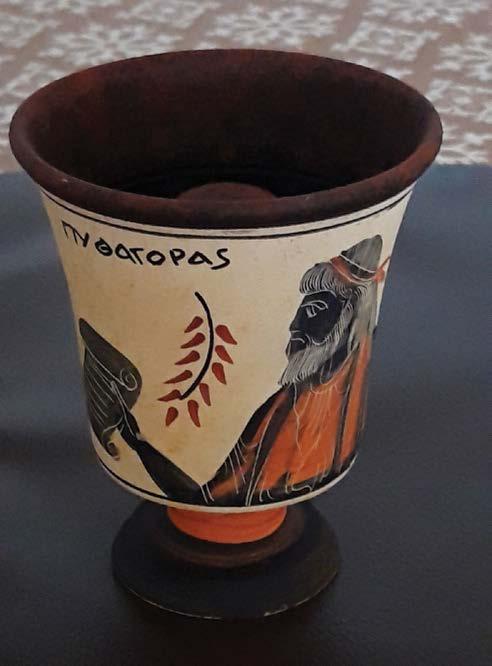

What does it look like? This particular cup is handmade of clay, and the decoration is close to the **white ground style that was popular at the end of the 6th C. BC. It is about five inches tall from foot to rim. The colors used are black and rust on an off-white background. I noticed (and one can see in the photo), these three colors are combined in different ways to give the impression of more variation. Pythagoras holding a scroll is depicted on one side with his name above and an olive branch (?), and the other side has a stylized palmetto design. By doing a small sketch, I was able to observe details that I hadn’t seen just by looking at and handling the cup.

Two different views of my Pythagoras cup (my sketch-

ful melding of form and function, and the aesthetics

left, my photo-right) Cultural Context Now, I was curious to find out how this tangible thing was known outside of Greece, so I did a Google search in English and was a little surprised at the top results:

print, but nothing about Pythagoras, except on Amazon: “Tradition says Pythagoras, during water supply works in Samos around 530 BC moderated the workers’ wine drinking by inventing the ‘fair cup’. When the wine surpasses the line, the cup totally empties, so the greedy one is punished.”

A Google search in Greek yielded somewhat different results: “How it works”, “what it is”, “punishment for hubris”, “the ‘smart’ cup”, “the ‘just’ cup”, “make one yourself” (instructions), “where to buy”, “Samos souvenir”. The results in Greek gave much more historical and scientific information about Pythagoras’ cup and focused more on the ingenuity of the design to teach a moral lesson. These differences in the cultural contexts were remarkable. Greek is a much more specific language than English and has many words that can only be translated into English by way of explanation. “Hubris” is one of them. It has a number of different explanations, depending on the context, including excessive pride, failing to recognize human fallibility and wanton wickedness, but one thing is for sure in the Greek tragedies, it is always punished. Pythagoras’ cup was designed to punish hubris and particularly, “pleonexia” (Πλεονεξία)-trying to get more than your share, which was considered an intellectual and moral error, a defiance of the laws of the universe. (Kitto p. 171)

How does it work? At The Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Greek Technology, there is a demonstration of the principle that causes “magic” to happen when too much liquid is poured into the cup.

“It was an ingenious wine cup that had a line which determined the limit of fulfillment and an axial or curved siphon. When one filled it excessively, the level of liquid covered the siphon and emptied automatically. It is considered an invention of Pythagoras (6th C BC) who wanted to teach his students the necessity of [applying] moderation in our lives. It is also called the cup of justice because it reflects the basic principles of justice (vituperation and vengeance). When the limit was exceeded (vituperation) lost was not only that which exceeded the limit but also that which had been acquired up to then.” The humanistic outlook of the ancient Greeks “urged human beings to develop physical, intellectual, and moral capacities to the fullest, to shape themselves according to the highest standards, and to make their lives as harmonious as a flawless work of art. Such an aspiration required intelligence and self-mastery.” (Perry, p. 55) From the outside, it looks like any other cup, but, as this cross-section reveals, it was designed to teach Pythagoras’ students lessons beyond the formal lessons of mathematics and philosophy: The ethical lessons of moderation in all things and justice. If a student poured himself more wine than his mates, he would be punished by losing all the wine, and probably be humiliated at being found out! Drinking in moderation was a virtue but there were higher principles to be taught, as well.

Reflection The process of looking closely was not a particularly new experience for me, but doing the sketch changed my interaction with the object. I began to think more about form and function and the artistic process of creating pottery. I launched my research with Google searches in two languages out of pure curiosity. Examining the cup in two cultural/language contexts led to surprising discoveries and guided me toward further sources across a number of disciplines. The first connections I made were within the obvious context of history. As new questions arose, however, I connected the object to hydraulics (technology), language, visual art, philosophy/ethics and economics. Reviewing my research notes/visuals and thinking critically helped me construct new knowledge and develop my thesis: Pythagoras’ cup represents much more than an ingenious, functional drinking vessel, it embodies the “wholeness of things” that was characteristic of the ancient Greek mind.

Throughout this investigation, the writing process was the way I recorded my evolving thinking and kept track of my research. (I kept a digital file, as well.) Handwriting notes has been proved in many studies to create deeper learning than typing on a keyboard. Teachers know this! Writing was an essential tool in each stage of the process Observe Closely, Connect Broadly, Think Critically. Finally, the exploration of this “tangible thing” has reinforced how much the constructivist approach to learning has become a habit of the mind after my years of teaching Humanities.

Notes:

*A Basic Guide to Greek pottery shapes Krater “Krater comes from a word meaning “mix”. Kraters were used for mixing wine with water.