15 minute read

IB English A: Literature Yr. 1

water. Kraters were used at drinking parties called symposia, where men would talk and enjoy the company of male friends, whilst their wives were prevented from taking part.”

**White ground technique “The white-ground technique was developed at the end of the 6th century BC. Unlike the better-known black-figure and red-figure techniques, its coloration was not achieved through the application and firing of slips but through the use of paints and gilding on a surface of white clay. It allowed for a higher level of polychromy than the other techniques, although the vases end up less visually striking.” Wikipedia

Sources Cited Kitto, HDF. The Greeks. Penguin Books, 1951.

Perry, Marvin. Sources of the Western Tradition, Vol 1. Wadsworth, Boston, USA, 2014.

https://thegeorgegarden.blogspot.com/2018/10/raphael-school-of-athens-labeled.html Accessed May 3, 2020.

https://www.artble.com/artists/raphael/paintings/school_of_ athens Accessed May 9, 2020

http://kotsanas.com/gb/exh.php?exhibit=2201006 Kotsanas Museum of Ancient Greek Technology Accessed May 5, 2020

https://www.polytroponart.gr/greek-pottery-shapes/ Accessed May 3, 2020

https://www.ancient.eu/Pythagoras/ Accessed May 7, 2020

https://www.zmescience.com/science/physics/the-pythagorean-greedy-cup-423545/ Accessed May 5, 2020

My sketch and my photo of the Pythagoras cup

Asynchronous Teaching & Learning, Active Student Engagement, And Student-Teacher Collaboration In Ib English A: Literature Yr. 1

by Dr. Evangelos Syropoulos Academy, English Faculty

One of the biggest challenges all IB teachers face is the enormous syllabus they have to cover in three semesters. Taking also into consideration that teachers could not exclusively focus on content but should also help students develop various skills as well as prepare them for many external and internal assessments, teaching an IB course looks like a Herculean task. To continue with the allusions to ancient Greek culture, the aim of this article is to show how a bit of Odysseus’ cunning and ingenuity in the form of asynchronous teaching/ learning may make this task far easier and less intimidating than it origi-

nally appears to be. To do so, I shall present how I incorporated asynchronous components in IB English A: Literature Yr. 1 that enabled me to run two classes concurrently: a traditional F2F class combined with an online asynchronous one during the first semester of the 2019-2020 academic year; and two online classes, a synchronous and asynchronous one, during the second semester, after the closing of the schools due to the Covid-19 pandemic. I shall also show how the use of online asynchronous activities during the first semester smoothened the transition to an exclusively online learning environment both for my students and me in the second semester.

Challenges of the New IB English A: Literature Course The structure of the new IB English A: Literature course necessitates that students are exposed to as many literary texts as possible in the first year of their studies. According to the new syllabus, they should freely choose which texts they are going to use for their official oral and written assessments. Taking into consideration that they should start preparing for these assessments at the beginning of the second year, students should have as many options as possible by the end of the first year. For this reason, I decided that they should study in-depth at least eight out of the 13 texts (11 at Standard Level) in the first year. At the same time, they should also acquire almost college-level thinking, oral, and writing skills, master both the contextual, theoretically-informed method of literary analysis and the sophisticated, detailed close reading of a text, while being introduced to three out of four official assessments: the Individual Oral, Paper 2, and the Higher Level Essay.

Paradigmatic and Syntagmatic Syllabus Design Even before I started exploring the potential of online asynchronous teaching/ learning, I decided that I should reconceive the design of the new syllabus to accommodate the new needs of our students. To use terminology borrowed from structural linguistics, the design logic used to create the syllabus of this course is usually a paradigmatic, vertical one. In each unit, teachers include literary texts from different historical eras and literary periods, encouraging students to explore thematic similarities between them. This approach can be particularly time-consuming, especially if it is applied not just to a unit but to the course in its entirety because several teaching hours should be spent in discussing radically different historical and cultural contexts. Moreover, the occasional back and forth movement between historical eras and literary periods can be confusing for students, preventing them from grasping how literary forms develop throughout the years – for example, how we move from literary realism to modernism and postmodernism. Since generic transformation was one of the prescribed organizing concepts of the new IB English A: Literature syllabus, I decided to combine the paradigmatic approach with a syntagmatic, linear one, enabling me to group literary texts from roughly similar periods within a unit and progressively trace the development of literary forms either from unit to unit or even within a unit. So, instead of structuring units around different themes, I chose an overarching theme for the whole course: the rise of individualism and its effect on literary writing. It is obvious that this theme already contains a diachronic, progressively historical dimension, allowing me to trace generic transformation and development from the ancient times to the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, modernity, and postmodernity. So in the first semester, students would be exposed to radically different forms of individuality in ancient Greece and the English Renaissance through the study of Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex and Shakespeare’s Hamlet, while additionally reading two classics from the Italian and French Renaissance: Machiavelli’s The Prince and Montaigne’s Essays, that also happen to be two of Hamlet’s most prominent intertexts and Shakespeare’s major influences while writing his play. In the second semester, students would study how post-Enlightenment middle-class individualism gives rise to the realist novel (Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey) and realist drama (Henrik Ibsen’s The Wild Duck) and is subverted in the modernist novel (Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse). Year two would focus on modernism’s division between high and mass culture (Robert Frost’s poetry, Joni Mitchell’s lyrics, Annie Dillard’s essays), the overcoming of this division in postmodern culture (Maya Angelou’s poetry and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton) as well as on how the existence or the subversion of this division determines the identity of both the author and the reader/ audience.

Previous Experience with Blended and Online Asynchronous Teaching/ Learning Although I had hoped that the above design logic would enable me to teach several texts at the same time and, thus, save some time, in the first month of teaching, I realized that more time was needed to help students develop their thinking, writing, and oral skills. This was when I started exploring the idea of asynchronous teaching/ learning. Although I had already used i2Flex activities (mostly forums) in the teaching of IB English A: Literature in the past, my attitude to the use of blended teaching/ learning radically changed after the training I received for online course design and the actual design of an English Literature course for ACS Athens Virtual in the summer of 2019. In particular, the activities I created for the studying of prose fiction and drama allowed me to understand that assessments should not be separated from instruction but conceived as an instructional tool, each one providing students with a different frame of literary analysis.

Semester 1: Combining F2F and Asynchronous Online Teaching/ Learning Determined to solve the problem of time, I decided in the first semester to take advantage of the intertextual connection between Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Machiavelli’s The Prince, and Montaigne’s Essays and run concurrently a F2F and an online asynchronous class. During November and December, students studied Hamlet in a traditional F2F classroom setting, while at the same time, they were studying independently Machiavelli (in November) and Montaigne (in December) in a virtual classroom setting. Their online learning experience

included the study of various primary and secondary sources as well as the composition of two mini-essays, addressing the representation of individuality in both writers, that were uploaded, peer-reviewed, and discussed in four different Moodle forums (two for each writer). Apart from the virtual classroom, Machiavelli and Montaigne were also discussed in a F2F setting in relation to Hamlet, enabling students to apply the knowledge they acquired from the online learning experience to the analysis of Shakespeare’s play in class. Apart from allowing me to teach three authors at the same time, this use of the i2Flex model of instruction enabled students to develop many different skills: critical and synthetic thinking, research, and oral skills in the F2F setting (through contextual presentations on the Renaissance, application of knowledge acquired online to the class analysis of Hamlet, and mock Individual Orals combining knowledge acquired both in the F2F and online classroom); critical reading and writing skills in the virtual classroom (through the four mini-essays/ forum posts on Machiavelli and Montaigne). It also allowed me to prepare students for different internal and external assessments at the same time: their oral assessment, the Individual Oral, in the F2F setting, and two of their written assessments, the Higher Level Essay and Paper 2, in the virtual classroom. The success of this experiment became immediately evident when I read the first forum posts on Machiavelli and saw how thoughtful and sophisticated they were, exhibiting in-depth understanding and critical application of the reading material. Moreover, when students had to choose two of the four texts analyzed during the semester for their mid-term exam (which was modelled after Paper 2), most of them selected the ones they studied online. When I asked them why they replied that they felt more confident with these texts because they were far more involved in their analysis. Ultimately, this online asynchronous component changed the class dynamic. We were not interacting any more simply as teacher and students, but as collaborators in the learning process. From the beginning of the online component, I explained the rationale behind the assignment and made clear that I needed the students’ active engagement and help in order to cover in-depth the demanding syllabus of IB English A: Literature. This empowered students to assume responsibility for their learning and view the detailed covering of the syllabus as our collective goal. Their attitude has inspired me to come up with bolder ideas about the use of asynchronous teaching/ learning in the second semester. Semester 2: Combining Synchronous and Asynchronous Online Teaching/ Learning A) Even before the end of the first semester, I knew that I would include an online component in the second semester for the analysis of the aesthetic form of Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, so after the winter break, I organized my F2F classes accordingly. In February, after the midterm exams, we studied at the same time the content/ context of Austen’s Northanger Abbey and Ibsen’s The Wild Duck through a series of research-based student presentations, focusing on how the cultural context of the Enlightenment enables the rise of literary realism, how Romanticism’s critique of the Enlightenment affects generic development as well as how the realist novel/ drama is generically related to the romance, the sentimental novel, the gothic novel, and melodrama. When our school closed, I was ready to introduce them, through the F2F discussion of Northanger Abbey, to the analysis of a fictional prose text’s aesthetic form: plot/ structure, narration/ focalization, characterization, setting, and language. The closing of the school did not affect the delivery of my syllabus, as the F2F sessions were immediately replaced by BigBlueButton synchronous sessions, supplemented with some low immediacy and asynchronous sessions that ensured that I retained some flexibility in the online environment. In this way, some formal aspects, like plot/ structure and character complexity, development, and depth, were discussed in synchronous sessions, while others, like the direct or indirect presentation of character, the representation of setting, and the referential or self-consciously literary use of language, were analyzed in more elaborately designed forums that exhibited the influence of similar forums I designed for my online course. These forums, apart from prompts, would include step-by-step directions for the analysis as well as references to carefully chosen and curated reading material that introduced students to a small number of clearly defined new concepts. Before the spring break, students finished the analysis of a realist novel’s aesthetic form, and they were ready to apply the knowledge they acquired to the analysis of realist drama through the 100% asynchronous study of The Wild Duck’s aesthetic form.

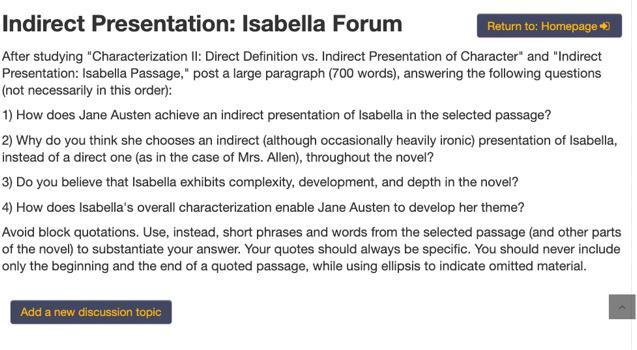

Jane Austen Forum: Indirect Presentation of Character

B) The design of the new asynchronous component greatly benefitted from the work I did for a GOA course on online assessment that I attended immediately after the closing of the schools. The Wild Duck asynchronous component was conceived as a combination of three forums, each one devoted to the analysis of different formal aspects: 1) plot/ structure, 2) characterization

and 3) setting and language. Three students would analyze plot/ structure, seven students would analyze characterization (each one a different character or a couple of characters), and two students would analyze setting and language. For the first phase, each student had to respond to a different prompt addressing different aspects of the formal elements and upload a 1000word essay. Once again, the forums included stepby-step directions for the analysis and occasionally strategic references to new reading material, offering more sophisticated approaches to methods of analysis they had already practiced in the synchronous sessions. For the second phase, after all the essays were uploaded, students had to study their peers’ responses and post in each forum a 200-700 word review of the essays submitted in each section (the number of words depended on the number of essays each student had to review in each forum). In other words, each student had to post three reviews, highlighting what they liked about the analyses, what they thought was missing as well as contrasting their peers’ analyses with their own evaluation of Ibsen’s use of plot/ structure, characterization, setting, and language in The Wild Duck. Obviously, this was a long-term assignment, lasting for more than a month, and ran concurrently with the synchronous study of Heart of Darkness and modernism, starting immediately after the spring break. The fact that The Wild Duck includes proto-modernist elements (especially its overdetermined symbolism) eased the transition to the synchronous study of modernism and Heart of Darkness. Assessment wise, there were multiple opportunities for formative assessment and feedback. Peer assessment was already part of the second phase of the task, and it led to self-assessment, as students had to repeatedly use the relevant rubric and apply its criteria to both evaluate the work of their peers and compare their peers’ performance against their own. Since most students are impatient with the detailed analysis of aesthetic form, the overarching goal of my feedback was to teach them how to insist on technical details. This was mainly achieved through the use of strategic questioning in the discussion forum (during the second phase of the task), directing students’ attention to nuances that their analysis may have missed. The most important learning target of this asynchronous component was the autonomous detailed close reading of a fictional literary text (The Wild Duck). Autonomy is the keyword here. Students had already spent many synchronous sessions closely analyzing with my help another fictional text (Northanger Abbey). The challenge for them now was to assume ownership of the skills they had already developed by applying them independently in order to both perform close reading and assess the close readings of their peers. Moreover, as all students studied in-depth and evaluated every formal aspect of The Wild Duck, an invaluable knowledge bank has been created that may prove extremely helpful in various official IB assessments: the Individual Oral, the Higher Level Essay, and Paper 2. This asynchronous component once again changed the class dynamic as well as the nature of my collaboration with the students, as they realized that they are responsible not only for their own learning but their peers’ learning.

Henrik Ibsen Forum: Analysis of Structure, Associative Relations

Summer Assignment and Online Asynchronous Learning One of the dilemmas I faced after the transition to a totally online learning environment was whether I should teach the eighth text of the syllabus To the Lighthouse. I could still teach it in an asynchronous way, but I feared that given the extraordinary circumstances and the work students had to do for other courses, the workload would be too heavy for them. I also felt that this workload would be unnecessary since the seven texts they studied this year already provided them with more than enough options for all their internal and external assessments. However, I found a way out of the dilemma when I started thinking about summer reading as a perfect opportunity for asynchronous online learning. Every summer, first-year students have a large-scale summer assignment, preparing them for the second year – usually, they study some texts and write an essay. For this year, I thought it would be a great opportunity for students to study To the Lighthouse in the way they studied The Wild Duck. They were already introduced to literary modernism through the synchronous analysis of Heart of Darkness, so they would easily apply their knowledge of modernist thematic concerns and aesthetics to the analysis of Woolf’s novel. The first part, including the independent study of the Moodle Reading Material, step-bystep directions, and the essay-length response to different prompts, could take place during the summer, while the peer-review and the F2F debriefing could take place in early September. In this way, my initial goal of teaching eight texts before the beginning of the second year would be accomplished without overburdening the students.

Concluding Remarks My initial combination of F2F and online asynchronous teaching/ learning in the first semester prepared my students for the smooth transition to an online learning environment after the closing of our school in the second semester. It also prepared me for a more rigorous exploration of the potential of low immediacy tech tools as vehicles for active student engagement and student-teacher collaboration. Looking back on all the prompts, extensive directions, carefully chosen and targeted resources, forum posts, responses, and discussions in the tabs of our course’s Moodle Shell, I witness the full transformation of teaching and learning into a collaborative effort; or rather, the realization of the platonic idea of the teacher-student relationship.