9 minute read

Testing the Flexible in i²Flex and Combo Studies

dents’ learning. Without a doubt, John Dewey’s words ring true for all of us, “We do not learn from experience... we learn from reflecting on experience”.

References Avgerinou, M. D., & Gialamas, S. (Eds.). (2016). Revolutionizing K-12 blended learning through the i2flex classroom model. Information Science Reference.

Clark, T. R. (2020). The 4 stages of psychological safety: Defining the path to inclusion and innovation (First edition). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Gleason, D. L. (2017). At what cost?: Defending adolescent development in fiercely competitive schools.

Gleason, D., PhD. (2020, April 15). Health & student support services: A message from David Gleason. Concord Academy. https://concordacademy.org/health-student-support-services-a-message-from-david-gleason/

Gleason, D., PhD., & Mattoon, M. (2020, April 24). National School Reform Faculty webinar: Live in fragments no longer, only connect. https://nsrfharmony.org/

Horn, M. B., & Staker, H. (2014). Blended: Using disruptive innovation to improve schools (1st ed.) [Electronic resource]. Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Brand. http://catalogimages.wiley.com/ images/db/jimages/9781118955154.jpg

■

by Hercules Lianos, Academy English Faculty

Monty Python’s Terry Jones, Michael Pallin, and Terry Gillian

In a Monty Python sketch, Michael Pallin, Terry Jones, and Terry Gillian burst into a room set in an English industrial town dressed as medieval cardinals. They shout in shrill voices, “nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!” to the surprise of an unsuspecting mill worker (Graham Chapman) and lady (Carol Cleveland). Michael Pallin then begins to list their car-

dinal weapons: “fear, surprise, ruthless efficiency, fanatical devotion to the Pope, nice red uniforms.”

If you are not familiar with the sketch, I apologize for what may have been confusing to you. I would say, however, that the first three of the cardinal weapons apply to the Covid-19 pandemic as well. It surprised everyone, spread fear, and is ruthlessly efficient - though as far I know it has no relation whatsoever to the Pope. Nobody expected Covid-19 in September, and we as educators were forced to adapt to a new landscape. Every aspect of the i2Flex approach was tested, as were the goals of interdisciplinary teaching and learning.

Testing Flexibility However, administration, IT, faculty, and our students were, in large part, prepared. For years now, ACS has focused on a blended learning approach through its i2Flex methodology. There has been consistent reflection and revision of teaching strategies for guided and independent student education. Our emphasis on face to face and independent inquiry learning was transferable to the synchronous and asynchronous lessons that schools worldwide grappled with. We had practical experience in what is needed to make blended learning meaningful. But let’s not kid ourselves. The transition was abrupt, and it was absolute. There was exhaustion, there was anxiety, and there was frustration. There was also perseverance and wisdom gained.

The transition was abrupt, and it was absolute. There was exhaustion, there was anxiety, and there was frustration. There was also perseverance and wisdom gained.

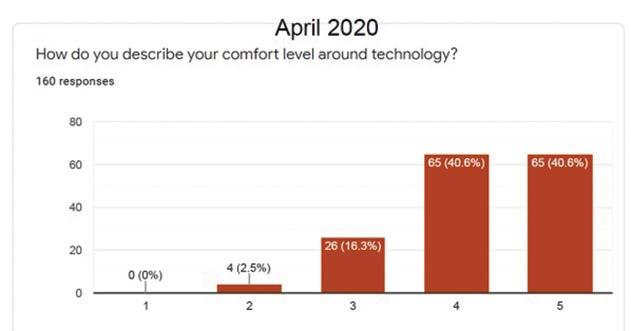

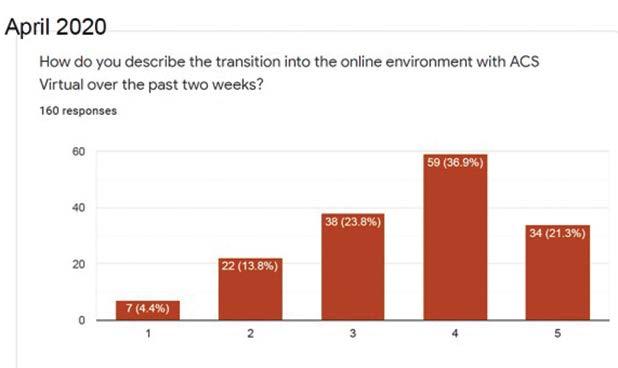

Flexible, independent, and inquiry-based learning is cultivated in students from the day they begin their educational journey at our school. Two weeks into “lockdown,” high school principal Dave Nelson wanted to take the pulse of the academy student body. In a survey he administered of 160 high school respondents in April, 81.2 % stated that they felt very comfortable around technology. Of those students, 58% felt quite comfortable transitioning into an online environment, while 18.2% felt uncomfortable. There is, of course, more than one way to skin a statistic. During professional development, the group I was in wondered if willing respondents reflect trends that would be found in those who didn’t respond to the survey. Be that as it may, this is still a strong indication that our student body was well poised to navigate virtual waters.

Our student body is well poised to navigate virtual waters 1. Very Uncomfortable to 5. Very comfortable

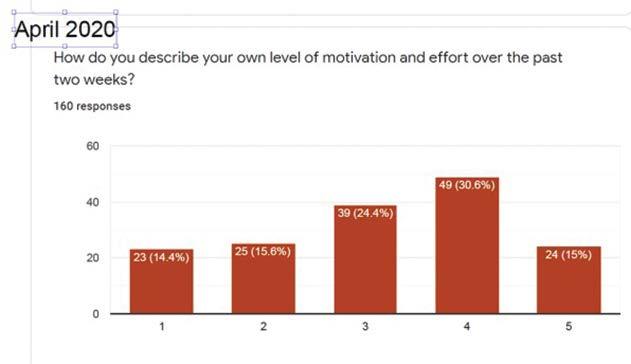

During campus closure face to face teaching hours decreased. This meant that students devoted more time to independent study, and faculty spent an impressive amount of time adapting content and delivery to invigorated demands of synchronous and asynchronous remote learning and assessment. Together with my Combo Studies partners, Marla Coklas and Leo Gontzes, I reflected on the process after each lesson. We noticed, broadly speaking, that some students more easily adapted to remote learning than others. Some students even felt more comfortable participating in discussions through the chat than when in a physical classroom. They became more “vocal” through their keyboards. What to do, though with those who are less motivated, have less developed time management skills, and are experiencing “Covid-19 closure” anxiety?

In that same survey, 30% of the students did not feel confident about their motivation levels, 26.9% about their time management skills, and 39.4% felt anxious about school closure. Addressing this set of statistics was perhaps the greatest challenge faculty faced during the Covid-19 phases. When sharing a physical space, an educator has an immediate understanding of engagement. The classroom is conducive to individualized support. Modeling learning, socialization, and utilizing physical proximity to instill motivation transpires more seamlessly in a physical setting.

Faculty became quite savvy, or rather savvier, with various platforms like Big Blue Button, Moodle apps and other tech tools - shout out to the IT team for all the support. This technology was utilized to meet educational goals by delivering content and providing a means for interactivity. Students may be digital natives; this, however, does not mean they necessarily are adept at educational tech demands. A large portion of the time faculty spent was on guiding students either during virtual office hours, synchronous lessons, or responding to individual emails throughout the day and night. We must remember that all of this existed in the greater context of a “Covid-19 world” and all that entails. Teachers were modeling, furbishing, and refurbishing their virtual classrooms. Accommodating the needs of all students in this new setting was and is an ongoing process. How does one achieve a constant gauge of involvement of all those pixelated usernames? This has been our challenge.

The classroom is conducive to individualized support. Modeling learning, utilizing physical proximity, and instilling motivation transpire more seamlessly in a physical setting. Covid-19 and Combo As “Combo teachers,” we set preserving the tenets of Interdisciplinary team teaching (ITT) as a priority. Integrating disciplines, understanding equality of partner roles, and sharing a vision are all elements that are required and cultivated throughout such a partnership. Jan Karvouniaris, whose dedication to interdisciplinary teaching is tireless, defines it as “the breakdown of artificial barriers between disciplines resulting in a richer curriculum.” As such, students do not view subject matter through a single lens, but rather through a kaleidoscope. A common theme is the lens, and critical skills are the tools, through which students view each discipline. All of this necessitates constant communication between teaching partners. During campus closure, common planning time shifted from primarily physically sitting together as a team during a planning block to virtual meetings, phone calls, and file sharing.

A goal behind any course should be to more deeply engage students by creating relevance between what they have been examining and their lives in the world today. It is relevant what Combo classes inherently focus on. What we aim for is a constructivist approach to learning where students draw from prior knowledge to solve current or novel problems.

Is history doomed to repeat itself? To what extent is literature a product of its social, historical, and geographic context? These are perennial questions. One thing is for sure, though, their relevance is timeless. This became absolutely clear during campus closure and a “Covid world”.

Students concluded their study of the Cold War and The Crucible by Arthur Miller shortly after campus doors shut. The themes of fear, paranoia, and mass hysteria, as expressed during this historical period and in Miller’s work, were discussed. These elements were clearly visible in today’s world to students.

As the Cold War Unit came to a close, we began the study of the Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights, the Vietnam War, and The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. Students examined common characteristics of dystopian (or speculative ) fiction and its purposes. Generally set in an imagined future, their authors filter through what is very real in the world today to spin a cautionary tale. Essential questions asked (thank you, Elizabeth Ktorides) were what role does

the individual play in the function of a society? What role does a community or government have for the individual? What are the responsibilities of each during times like these?

What role does a community or government have for the individual? What are the responsibilities of each during times like these?

In his Financial Times piece, “The World After Coronavirus,” Yuval Noah Harari warns that in times of crisis, freedoms are necessarily limited for the sake of the greater community, but do they stay limited when the crisis is gone? Offred, the narrator in The Handmaid’s Tale, reflects on how Gilead came to be when she muses, “nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it.” However, in response to the question, “are we living in a dystopian society?”, Atwood responds with an emphatic “no.” She asserts that it is a crisis and that it requires concerted mobilization. Students drew parallels between the emotional, civil, and political reactions to the spread of Covid-19. We again reflected on what the collective responsibilities are. We looked at news pieces and discussed possible parallels between history, literature, and the world today. We examined why the Harlem Renaissance helped to redefine how Americans and the world understood African American culture and how it set the stage for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. We also came to the realization that the struggle for a just and free society is an ongoing one. In his 1951 poem, “Harlem” Langston Hughes ponders what “happens to a dream deferred”. What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a soreAnd then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar overlike a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode?

Weeks after its initial study we revisited the last line, “Or does it explode?”. We reflected on it following the protests that transpired after police officer Derek Chauvin was recorded killing a subdued George Floyd. We asked the class if their understanding of the poem changed in any way. We discussed what ways citizens mobilize to affect change and to what extent they are effective or justified. We again studied media repre-

sentations and statistics. Offred argues that change is gradual, but often it can be abrupt, as was the case in March 2020. The question is if, and how quickly, you can adapt without sacrificing core values, how flexible you can be. As educators, this is what we wrestle with. We were all tested during the pandemic and will continue to be. Eventually, we will flatten the Covid-19 curve. But as educators and eternal students, we will never flatten the learning curve. If we do, we’ve stopped trying.