Cities & Rivers: aldayjover architecture and landscape

1

Recovery of the Gállego River Banks in Zuera –– 30

The Monomaterial Building

Iñaki Alday –– 96

Bullrings in the River

Luis Francisco Esplá –– 42

Residence and Day Center for People with Intellectual Disabilities –– 100

The Mill Cultural Center –– 44

The Water Park –– 108

Cities & Rivers

Introduction –– 04

Ca La Mustera Farmhouse –– 56

Water Park Pavilions

Bath Pavilion

Ceremony Pavilion

Quay Pavilion –– 124

Beyond Sustainability

David Cohn –– 08

A porch in Monells and Other Designs by Iñaki Alday and Margarita Jover Xavier Monteys –– 64

Renovation of Paseo de la Independencia –– 66

Time Regained

Eduardo Arroyo –– 132

Arbolé Theater –– 134

Floods, River Dynamics and Climate

Change in the Urban Public Space

Iñaki Alday –– 14

Seven points of disrupting dichotomies

Bruno de Meulder

Kelly Shannon –– 24

Las Armas Social Housing –– 74

Water Park Power Plant and Infrastructure Buildings

Power Plant and Video Art Center

Water Park Maintenance Building

Electrical Substation –– 140

Las Delicias Sports Hall –– 84

2 Table of Contents

Recovery of Uniland Quarry –– 150

Can Xarau Park –– 210

San Juan de Puerto Rico Old Aqueduct –– 286

Aranzadi Park –– 158

Agricultural Interpretation Center –– 218

San Juan de Puerto Rico Old Aqueduct –– 294

Aranzadi Park: From Techno-Nature to Socio-Ecological Public Space

Elizabeth K.Meyer –– 170

Benicàssim New City Center –– 174

Ibiza Pedestrian City Center –– 230

Kelani River Park –– 308

Mas Bassedes Farmhouse –– 240

Metropolitan Forest of Madrid: The Southern River Parks –– 318

Cerdanyola Green Corridor –– 182

Green Diagonal Park –– 246

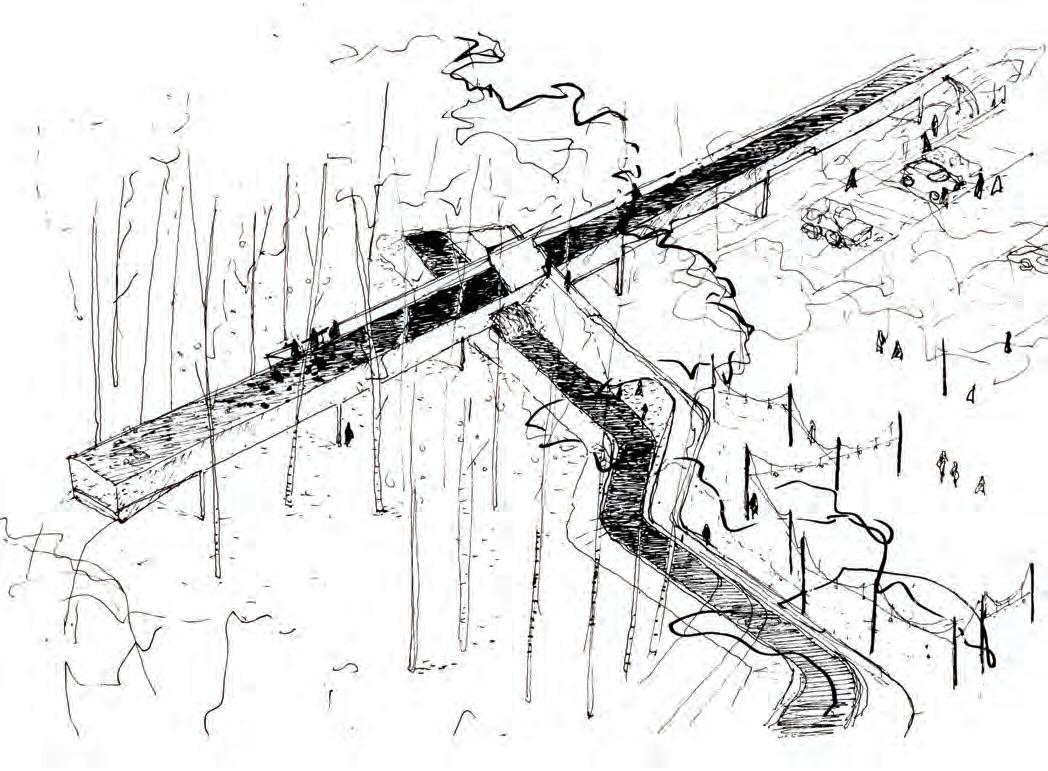

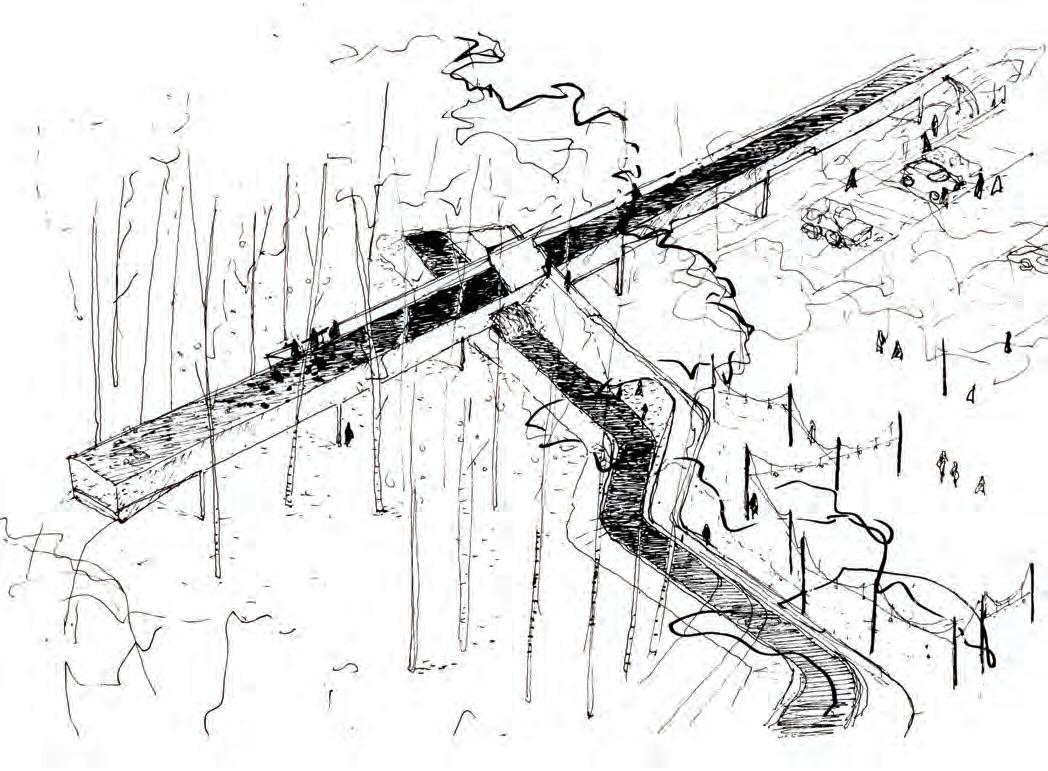

On Architectural Drawing Margarita Jover –– 326

Badalona New City Center –– 190

The Radical Pastoral: Barcelona's Green Diagonal

Sueanne Ware –– 264

Zaragoza Tramway Integration –– 196

Park Güell Extension in the Tres Turons –– 268

Biographies –– 330

Credits –– 333

The Tramway as an Urban and Landscape Project

Javier Monclús –– 206

Santiago de Compostela Green Plan –– 276

3

CITIES & RIVERS INTRODUCTION

This volume collects, in chronological order, a selection of projects and works built by aldayjover architecture and landscape. Founded in Barcelona in 1996 by Iñaki Alday and Margarita Jover, later joined by Jesús Arcos and Francisco Mesonero, the firm has positioned itself since its inception in the uncomfortable and indefinite space between the building, the public spaceand the landscape. A changing space that struggles with formal definition, and therefore, offers more freedom for design and more opportunities for discovery than the traditional disciplinary approaches to buildings and to gardens.

Contrary to what is usual in a young firm, and often throughout a professional career, we quickly decided to give up the single-family house as a subject of exploration. Although the 20th-century modern avant-gardes used the house as a research opportunity in the domestic space1, 60, 80 or 100 years later this exploration is essentially exhausted. The single-family house remains a fertile ground for formal gymnastics, but the planet cannot afford more irrelevant exhibitionist exercises when they mean the consumption of the territory, the increase of commuting, the unnecessary expansion of infrastructural networks, and the waste of energy and resources through small, scattered units.

Others are the needs of our time to which architects, urban planners, landscaper architects and engineers are called upon to respond. The lack of decent and affordable housing is much more relevant and demanding of imaginative new solutions than the formal exhibitionism

of the single-family home or the iconic object. And the same can be said of public services – facilities, green spaces and infrastructure – always at a disadvantage with respect to corporate and speculative interests.

Two events of international repercussion mark the period of greatest flourishing of architecture and urbanism in modern Spain. The Olympic Games in Barcelona in 1992 exposed a country in transformation to a massive planetary audience for the first time. Since the early 80s, an unusual alliance between public authorities and experts – architects, urban planners, engineers – physically built a new democratic country. An avalanche of civic facilities, social housing, parks, streets and infrastructure began to appear, radically changing what was an undersupplied country – the last European state to free itself from a fascist dictatorship after 40 years. 1992 marked the showcase not only of a country, but also of the work of generations of extraordinarily well-trained architects, on the shoulders of the heroes of the hidden Spanish modernity. At the opposite end of this period, the Zaragoza International Exhibition “Water and Sustainable Development”, in 2008, coincides with the bursting of the real estate bubble and the almost absolute disappearance of opportunities for many architects that the excellent Spanish schools had formed during those almost 20 years of romance between public policy and architectural culture.

aldayjover is part of an architectural culture focused on the public and aligned with the ideals of the project

4

Essays

of modernity, not only architecturally (transparency, rationality) but also socially (equity and public service). Spanish architecture at the end of the century, busy solving pressing needs, did not allow itself the luxury of exploring postmodern banality. This political, economic and cultural context is the milieu for aldayjover’s diverse body of work, practically all won through blind design competitions.

However, aldayjover sets itself apart from two aspects that characterize the turn of the century: formal exuberance and the focus on the production of the object. Faced with the formal exuberance that is exhibited with the emergence of deconstructivism and other currents, aldayjover’s line of work is characterized by a formal containment that responds to uses and users, and that is obsessed by the appropriateness of the materiality and tone of the geographical insertion of the project in its context. Our references are the figures of Martínez Lapeña/Torres and Josep Llinàs (training offices of Iñaki and Margarita) and Alejandro de la Sota. Skeptic with the autonomy of the architectural object, a still living legacy of postmodernity, aldayjover understands architecture not so much as a creation but as a transformation of a place. Architecture extends into a continuum that goes beyond the building to incorporate the dynamics of the landscape, public space, infrastructures and agents operating in the territory. This multifaceted and multi-scale perspective develops a voice of its own in a global context of erosion of the role of the architectural discipline. Alternative to the traditional role as a service provider, with the emergence of climate change and the exacerbation of social inequalities, the relevance of architecture must be measured in the ability to formulate the appropriate questions and innovate in new answers. Complex socio-ecological challenges can no longer be addressed with standard disciplinary solutions or gleaming objects.

The first project, in parallel to small reuse and restoration commissions in the old town of Barcelona, positions the studio in that space of no man’s land between the city, the building and the landscape. A bullring, a riverbank damaged by landfills and a small growing town are the ingredients in the Recovery of the Gállego River Banks in Zuera. The project responds to the wishes of

citizens, to the environmental needs of the river and the riverbank, to the physical security of the urban area, to the urgency of basic urban sanitation facilities, and to the opportunity that geography offers to guide the growth of the city and its urban quality. But combining all these demands required a complete change of paradigms about what is expected from a building, a park, and a battered back of town.

The same themes continue to appear during the following years, branching out into several lines of architectural, urban and landscape investigation. Water, the relationship between the river and the city, and the project of public space that absorbs and controls floods constitute a consistent line of work. In Zuera, aldayjover produced the first model of public space and floodable architecture of the modern era, which evolves and expands in scale in the Water Park for the EXPO 2008 in Zaragoza, and includes new strategies in the Aranzadi Park in Pamplona or in the Kelani River in Sri Lanka.

The seminal project of the Recovery of the Gállego River Banks in Zuera is also the origin of other lines of research developed by the studio. The powerful and complex physicality of the riverbank – boulders, logs, rocks, earth, organic matter, living systems of flora and fauna – propels the evolution from white, almost immaterial, geometries to an abstraction soiled by textures, raw materials and traces of life. Concrete -on-site formwork with canes or holes or precast- continues to be explored materially and structurally in many subsequent projects. In particular, a number of buildings innovate with structures of thin concrete walls that allow a single material to solve interior and exterior, structures and finishes: the Mill in Utebo, the Las Delicias Sports Hall, and the Power Plant and Video Art Center. The programmatic “perversion” of a bullring open to the river, topographical, floodable and prepared for other uses, has its continuation in the spatial interlocking of the sports center, in the video art center and the power plant, in the civil wedding pavilion and greenhouse of the Water Park, and in other models of programmatic assembly.

The Recovery of the Gállego River Banks in Zuera, once its role as flood management is understood, starts one

5

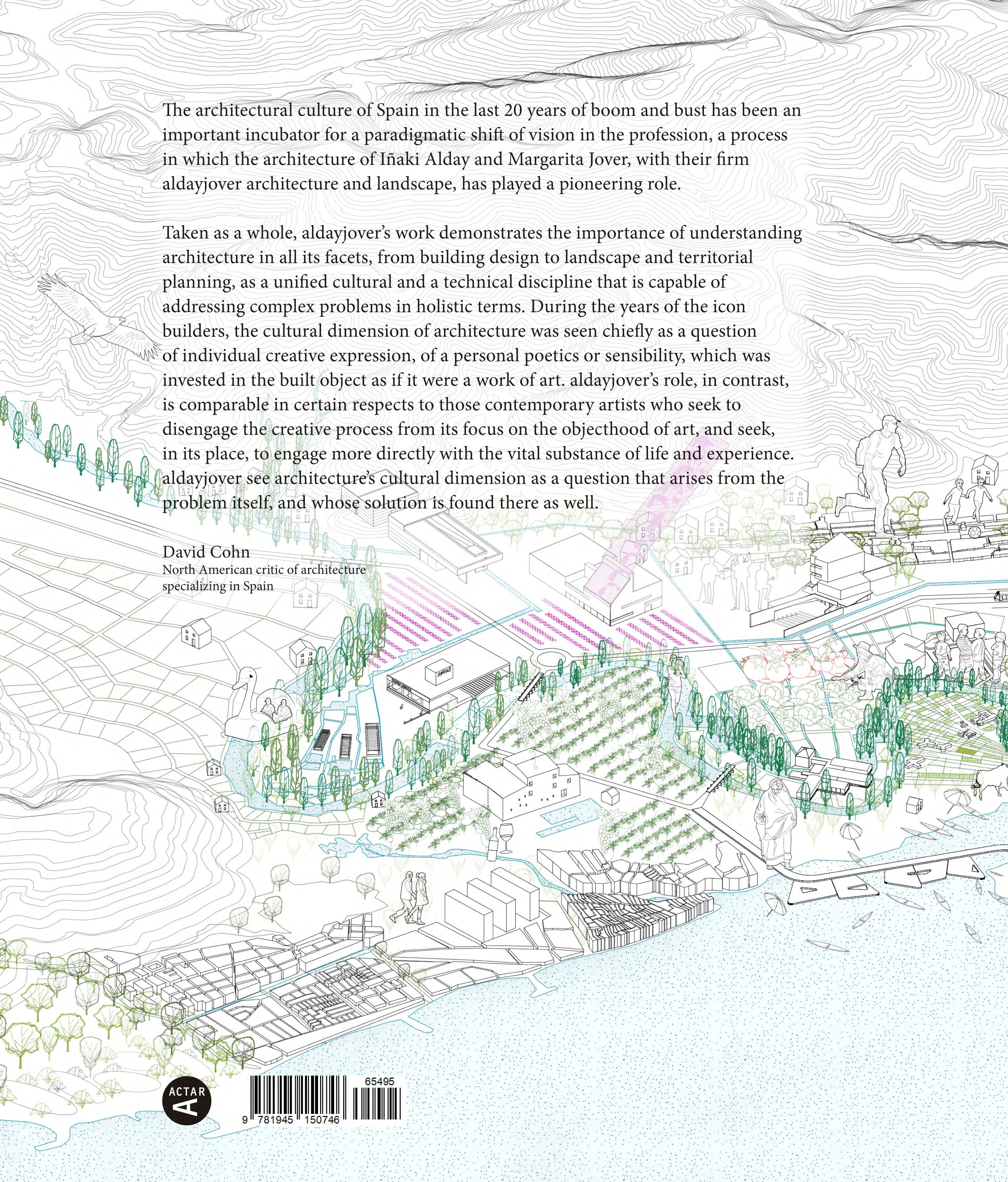

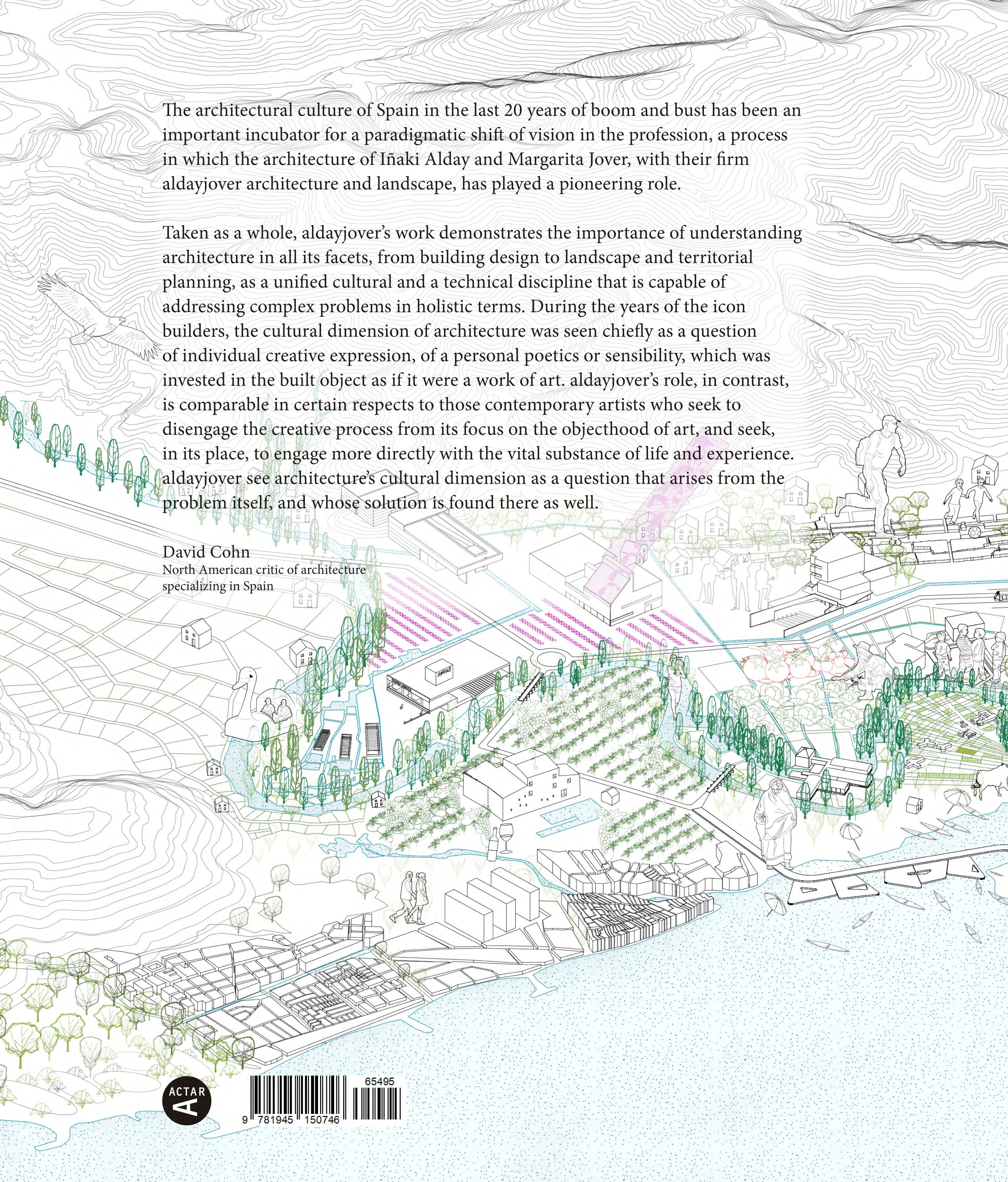

BEYOND SUSTAINABILITY DAVID COHN *

The architectural culture of Spain in the last 20 years of boom and bust has been an important incubator for a paradigmatic shift of vision in the profession, a process in which the architecture of Iñaki Alday and Margarita Jover, with their firm aldayjover architecture and landscape, has played a pioneering role.

During the boom years, interest in architecture was mainly focused on the iconic, inventive formalism exemplified by Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Bilbao, opened in 1997. But this creative euphoria was left in moral ruins by the crash of 2008 and the revelations of overspending, mismanagement and corruption on the part of many politicians involved in public building, exposing a culture of ostentation and excess in which the architecture of the Guggenheim era was inexorably implicated. In the wake of that disillusion, the pursuit of formal novelty could no longer in itself sustain architecture in its aspiration to address the public good, to work towards improving and humanizing everyday life – an aim, I would argue, that has been the fundamental motivation of architectural innovation since the origins of the Modern Movement in the 18th century.

Ten years have passed since 2008, but the profession in Spain has yet to recover a normal level of activity, and many of its most talented members, including Alday and Jover among them, have found their best opportunities abroad. But the end of the period of plentitude has also been a time of reflection, investigation and the development of alternative strategies, especially for a new generation of architects that has come of age just before and during the crisis. These new initiatives have explored issues of sustainability, environmental ecology, and a focus on immediate, local problems within a global understanding of the issues at stake, as opposed to the media-hungry focus of the icon builders. Architects have joined neighborhood activists in projects such as community gardens, alternative cultural spaces and participative planning efforts. They have developed radical new approaches to the adaptive re-use of existing buildings in response to principles of sustainable practice. There have been exhibitions exploring alternative building systems and materials of traditional cultures from around the world. Others have developed methods incorporating Big Data into the design process, and the global issues it can encompass.

Well before the crisis, however, aldayjover began its practice with what could deceptively be termied “landscape” projects, as in their Gállego Riverbank Recovery in the town of Zuera, in Aragón (19962001), but that in fact anticipate many of these concerns, and offer the first complete profile of the emerging paradigm that brings them together in a coherent, renewed vision of architecture and its role in culture and society. Their work is no longer strictly contained within the conceptual boundaries of the individual building or project as the principal object of design and study. Instead, their attention has shifted to a holistic overview of the habitat, of the environment and its mix of urban and natural features, as the true field of action for architecture and its ambitions.

As a consequence, on the one hand, their buildings can be understood as almost equivalent to the role of street furniture in the design of an urban plaza. This is evident not only in the various pavilions of the Zaragoza Water Park, for example, which are subsidiary to the broader aims of the park design as a whole, but also in specifically architectural commissions, such as The Mill Cultural Center, in

8

Essays * North American Architect and Architecture Critic

which the new structure is conceived in relation to the original mill building and the surrounding context, and assumes a modest protagonism, entering into a quiet dialogue with its environs. Buildings in both cases become functional, minimal elements conceived in terms of a larger frame of reference.

On the other hand, and more importantly, this approach implies that the true subject or responsibility of architects today is found in the environment, the livable habitat, and the full spectrum of issues at stake in its maintenance and adoption to human needs. This principle has led aldayjover from the limits of specific commissions to take on the broader issues that arise in the course of studying the problem at hand. A case in point is their project for Zuera, where their studies for a modest bullfighting ring led them to organize a new riverside park on its site, with an innovative design that accommodates, rather than resists, seasonal flooding. This in turn led them to a new development plan for the town, an environmental clean-up and

new sewage treatment measures, resulting in a coordinated plan that established a new, positive relation between the town and its river (including an amphitheater that serves other uses besides bullfighting, and that is designed for periodic flooding). Alday explains, “The idea was to bring together different stakeholders with different interests. The town wanted its bullring. The watershed authority was concerned because the river was eroding the banks below the town. And ecologists wanted to clean the river of trash and raw sewage. By bringing together these different stakeholders, we received the support of the European Union, and the final investment was 2.5 million euros, instead of the initial 250,000. And it solved many problems instead of only one.”

Aldayjover’s case for architecture’s role in solving territorial issues can be understood as a bid to rescue the living habitat from the blind and uncoordinated technical management of the planner, the sociologist, the civil engineer, the environmental scientist and so on, to the degree that such professionals, in their

rational and scientific methodologies, tend to objectify and quantify the habitat in the sense defined by Martin Heidegger in his essay, “The Question Concerning Technology,” which identifies a way of thinking in which, for example, a lake becomes nothing more than a quantifiable amount of stored water, a “resource”1. All of these specialists are necessary in solving problems at a territorial scale, but they are not sufficient in themselves. As in the building trades, architects are not only coordinators of different specialists. They bring to the table the humanist values of architectural culture, its awareness of history, its sophistication in visual, spatial, sympathetic and associative or poetic thinking, and its full participation in cultural and intellectual concerns in the broadest sense.

In aldayjover’s encompassing approach to design, the habitat is no longer the tabula rasa of the technician. It is a palimpsest replete with traces of the interactions of human history and culture with the natural habitat and the givens of geographic circumstance. Any new intervention sim-

9

CANAL IN THE WATER PARK IN ZARAGOZA

Ter River Territory. Pals rice paella recipe at the Foodscapes exhibition. Venice Architecture Biennale 2023

FLOODS, RIVER DYNAMICS AND CLIMATE CHANGE IN URBAN PUBLIC SPACE IÑAKI ALDAY

aldayjover designed one of the first floodable public spaces and public facility in modern times in Zuera Spain in 1998 –construction finished in 2001. The project, with a total extension of 20 Ha (50 acres), sealed a landfill and reconnected the river forest with the town. It included a bullfight and multi-purpose arena integrated in the park, compatible with seasonal floods. Its flood diagram became a paradigmatic image and the project was exhibited in the 2004 Rotterdam Architecture Biennale. With the title “The Flood”, it was meant to foster a

national discussion in preparation for the Dutch operation “Room for the River” (2008-2014). This biennale confronted the public with increasing flood risks, seeking to visualize alternative solutions to traditional hard engineering operations. In 2004, the Recovery of the River Banks of the Gállego River in Zuera was the only built project exhibited at the biennale as example of new solutions.

Before Zuera, only three public space projects had explicitly dealt with river or stream floods. In 1989 Pascal Hannetel

designed a series of retention spaces in a small stream, the Petit Gironde.1,2 Placed in a rural area, the design offered spatial qualities that announced its potential as a hybrid public space. The same landscape architect designed the Parc Corbiere (1995) in the floodable banks of the Seine in Le Pecq. As described by Prominski and his co-authors, the park engages playfully with the flood “but the use of the flood dynamics has not been extended to the design of the riverside”.3 In 1993, Michael Van Valkenburg designed a radical proposal for the 32

14

RECOVERY OF THE GÁLLEGO RIVER BANKS IN ZUERA. FLOOD DIAGRAMS

RECOVERY OF THE GÁLLEGO RIVER BANKS IN ZUERA. FLOODED BULLRING, 2014

Essays

acres (13 Ha) Mill Race Park in Columbus, Indiana (USA), allowing the free entrance of the river and keeping part of the civic program protected through topographical operations. The Recovery of the Gállego Riverbanks in Zuera took these precedents, most significantly the Petit Gironde, to “design the flood” in the public space with a radical new approach to the relation between rivers – and their dynamics – and their cities settled in the banks. The Gállego riverbanks project introduces the full scope of the flood dynamics in riverside public space and the bullfight arena.

This set of four seminal projects brings to the Western hemisphere in the turn of the XXI century the long tradition of the South Asian ghats, the stepped riverbanks, typically built with stone, that connect towns and temples with their rivers, mostly for cultural and religious practices but also for daily life (fishing, transportation, bathing, laundry, or leisure). South Asian ghats negotiate the strong oscillations of the monsoon rivers allowing permanent access to the water through a strict architectural device. Ghats are physical connections between the urban terrace and the river flow, built in the same materials as the

temples, forts and other urban constructions, as the Ahilya Fort in Maheswar, in the banks of the Narmada River. Ghats accept the water oscillation and capture copious sediments left by the river for its use in the fields, managing productively most of the effects of flooding.

Hannetel’s Petit Gironde, in a rural area, and aldayjover’s Gállego, in an urban area, reinterpret in their respective contexts the flooding of a stream (Petit Girond) or a small river ( Gállego) including the rest of the river dynamics.

The Recovery of the Gállego River banks designs the sedimentation process with different planting strategies, filtering dragged objects and large solids, while allowing fine particles to pass for fertilization and flora development. A perpendicular drainage system is traced along the vegetal filters, including small bridges from which kids fish during the high waters season. Close to the concept of ghats, the bullfight arena is a stepped amphitheater open to the riverbank that floods and drains through the two ceremonial doors -the matador’s and the bulls’ doors. The cattle areas are slightly depressed and become temporary ponds contained by walls, until the soil soaks

the remains of the flood. The project was awarded with a groundbreaking European Urban Public Space Prize in 2002.

The later “Room for the River” (200814) was framed as a territorial operation at a big scale, fundamentally addressing farmland and rural or sub-rural areas, to increase the drainage capacity of the Rhine system in the deltaic lands of the Netherlands. With a complementary but different approach, the work of aldayjover focuses on the relation of rivers and floods with urban and peri-urban public spaces.

In 2005, aldayjover won the international competition for the Water Park for the EXPO 2008 “Water and Sustainable Development” in Zaragoza. It is located in the main river of the same watershed as the Gállego, the Ebro, the river that carries the largest volumes of water and with the highest seasonal variations in the Iberian Peninsula. This project is significantly larger, from 20 to 125 Ha (50 to 300 acres), transforming a peri-urban agricultural meander in decadence into the largest park of the city and the main piece of the 2008 International Exhibition. A quarter of the park is seasonally shared by the river and the

15

AHILYA FORT ON THE NARMADA RIVER, MAHESWAR, INDIA

SOURCE: LUKAS VACOVSKY. WIKIPEDIA COMMONS

AHILYA FORT ON THE NARMADA RIVER, MAHESWAR, INDIA. GHATS DETAIL. SOURCE: PANKAJ VIR GUPTA

The Mill Cultural Center

Cities 44

Geography, territory and urban history in the definition of a hydraulic infrastructure

The design approach for the transformation of the architectural ruin of an old mill into a Cultural Center is tied in with the understanding of the territory that supported it over the centuries. The town of Utebo – in the province of Zaragoza, Aragon – is located on a huge flood plain of the Ebre River, one of the largest and most fertile river basins in Spain. The middle of this flood plain is characterized by broad meanders that have changed paths over time, and the soil has been fertilized by the deposit sediment from the river, with major agricultural benefits. The current landscape of Utebo – which sits in this fertile basin – is characterized by a continental climate with large temperature variations, sparse and irregular rain (320mm/year), and a cold, dry wind called “El Cierzo” by locals. As a result of humanization processes, the natural landscape of the riparian woodlands was replaced with agriculture, and the deforestation of centuries past led to the disappearance of forests of holm oak, juniper and European oak outside the flood plain. This eventually generated an arid landscape of white clay and limestone, with very little fertile soil, known as “Los Monegros”. As a result, traditional architecture sought to mitigate the continental climate through cisterns

to store water and thick mud walls for insulation, in the midst of a territory caught between the fertile basin watered by the Ebre River and the barren, arid landscape of Los Monegros. The region – shaped by a complex cultural and ecological ecosystem – supports a man-made landscape atop a geographic, geological and climatic foundation, of which the old mills are a part.

In the productive territory of the agricultural basin, the landscape is characterized by a dense network of ditches and irrigation canals that use gravity to supply the fields with water and are managed by irrigation communities. The most important of them is the Imperial Canal of Aragon, the relevance of which in terms of scale and scope reached a continental level. It was built from 1776 to 1790, between Navarra and Zaragoza, to ensure irrigation for the crops nestled in the valley, and it had a complex sub-network of smaller canals managed using a system of dams, floodgates and valves. The system includes the Almozara canal, which supplies water to the fields in Utebo and crossed the town to power the mill located in the El Monte neighborhood. All that is left of that mill, which appears on old maps of Utebo, are vestiges posterior to its historical use for the production of flour, an activity that was complemented after the 20th century with the production of hydroelectric power.

Continuity and discontinuity with history: The issue of the ruins

The commission for the design of a new Cultural Center and a small museum about the use of water resources in Utebo addresses the tough issue of how the ruins of the old mill should be treated. At the time of the commission, the ruins were located 1.2 to 2 meters above the groundfloor level, and three well-preserved barrel vault arches were preserved on the basement level. The original building – made from traditional brick, stone and mortar walls – was flanked by the Almozara canal, which is still active although it has been decades since the mill has ground any grain or produced any electricity. The square footage required for the new construction of the cultural center was so large, that it would have been easy for its construction on the plot to eradicate the delicate ruins. Their presence is still relevant both physically and symbolically in the memories of many residents in the region. As such, the design is centered on the continuity with history, reusing and reinterpreting the pre-existing elements to strengthen them and bring them back to life. The volumetric organization aims to leave open space above the old barrel vaults, situating the new building in the rest of the area designated by the planning. Finally, the building material is ochre-colored dyed concrete, a nuance of technological evolution added to the base of the traditional wall construction.

45

UTEBO IN THE EBRO RIVER VALLEY

UTEBO

ACEQUIA DE LA ALMOZARA RÍO EBRO

CANAL IMPERIAL

ZARAGOZA N-232 AP-68 FERROCARRIL

PLANTA BAJA

GROUND FLOOR

1 ASCENSOR (CAP. 13 PERSONAS). 2 INSTALACIONES. 3 ARMARIO DE CONTROL. 4 MOSTRADOR DE INFORMACIÓN Y CONTROL. 5 ACCESO PÚBLICO DESDE LA PLAZA ARAGÓN. 6 ACCESO PÚBLICO DESDE EL PARQUE DE LA ACEQUIA. 7 VESTÍBULO. 8 MOLINO: ZONA DE VISITA Y EXPOSICIÓN. 9 ESCALERA HACIA SÓTANO MOLINO. 10 ESCALERA. 11 ESCALERA HACIA TURBINAS. 12 SALA DE ACTOS.

1 ELEVATOR (CAP. 13 PEOPLE). 2 FACILITIES. 3 CONTROL CABINET. 4 CONTROL AND INFORMATION COUNTER. 5 PUBLIC ACCESS FROM ARAGÓN PLAZA. 6 PUBLIC ACCESS FROM DE LA ACEQUIA PARK 7 LOBBY. 8 WINDMILL:VISIT AND EXHIBITION AREA. 9 STAIRCASE TO BASEMENT MILL. 10 STAIRCASE. 11 STAIRWAY TO TURBINES. 12 EVENT ROOM

52 Cities

2,5 57,5m 0 7 5 10 1 2 3 4 12 6 11 8 9

LIBRARY INTERIOR

Mill Cultural Center

The

53 LONGITUDINAL SECTION CROSS SECTION 51020m 0 15 SL ST 51020m 0 15 SL ST

The Water Park

108

Rivers Rivers

For three months in 2008, the city of Zaragoza – capital of Aragon, in northeast Spain – became the headquarters for the international exhibition Expo 2008, which centered on the theme “Water and Sustainable Development”. The exhibition grounds were located between the banks of the Ebro River and the edges of Zaragoza’s fourth ring road, which crosses the Ranillas meander. The location was ideal, both for the ease of access by car and for its proximity to the river, tying in with the theme of the event. In addition to serving as a splendid emblem of the exhibition’s intentions, the small 25-hectare plot brought substantial national investment (from both public and private sources) to the city of Zaragoza and the community of Aragon. It resulted in urban renewal interventions that not only supported the success of the event but also improved the city as a whole, transforming quality of life there in the long term. Specifically, the improvement measures encompassed: opening the city to the Ebro River, along with connecting the system of urban and metropolitan parks; updating the circulation infrastructures by completing the ring roads; increasing the performance of the railway infrastructures with the new TGV route Madrid-Zaragoza-Barcelona; expanding the services sector with new hotels, office spaces and commercial establishments on different scales; and, finally, improving the airport and expanding the offer of public facilities. Understanding this international event as a catalyst for investment was key to ensuring that hosting it would be beneficial for the city as a whole. The project for the Metropolitan Water Park, covering 125 hectares on the exterior side of the ring road, adjacent to the exhibition grounds,

was part of these extraordinary benefits for the future development of Zaragoza after the event was over.

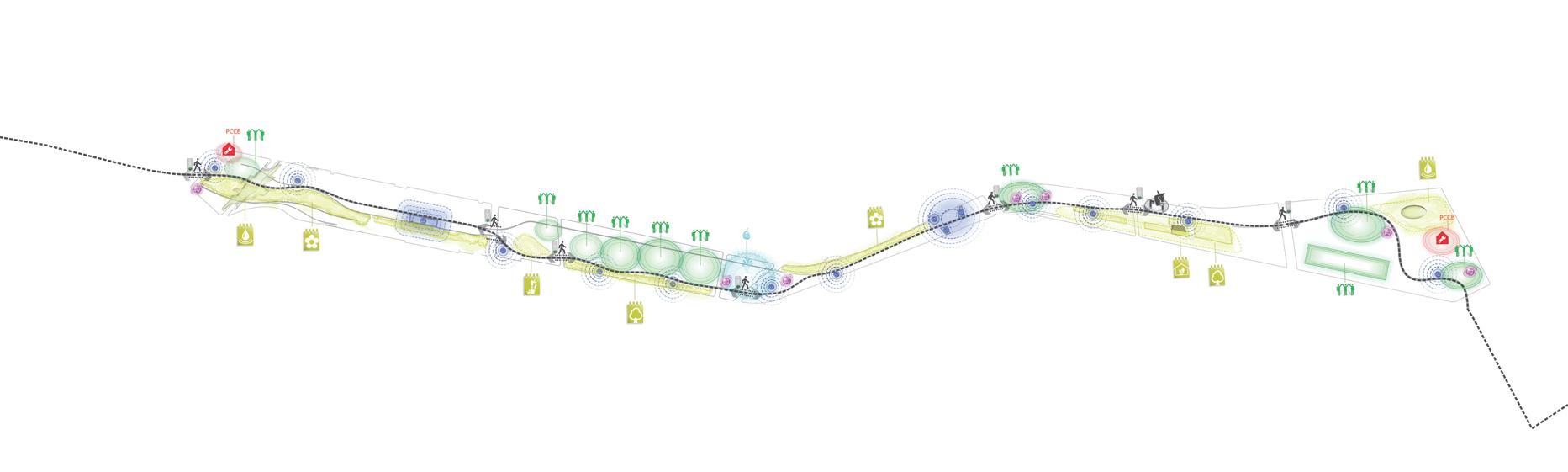

The relevance of the Water Park project lies in recognizing that it meant designing a transformation process, attuned to the surroundings and to the passage of time – a design process that was not a response to contemporary formal logics but rather established architectural, topographic and landscape logics to promote geographic, historic and territorial integration. A series of strategies that would guarantee its future vitality. Their development settled somewhere between the urgency of the event and the patience it requires for a garden to take shape. The park is a continuous reminder of its inclusion in the corridor of the Ebro River, in the traces of its history, and in the flows of an energetic river that controls its own dynamics.

The envisioned park was a silver-plated meander, inspired by the nature of the original riparian vegetation – a park with a strong identity that would contain the seeds for all the future developments along the banks of the Ebro, introducing nature into the city. The design began with a desire to express the history of a territory and its relationships with the people who live there, transforming it into a reflection of the strength of the river and its swells – a space for overflow, where the vegetation serves as a natural filter, where the river lets loose its energy before being redirected downstream.

109

112 Rivers The Water Park PROPOSAL FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF THE WATER SYSTEM 0. RABAL IRRIGATION CANAL - FLOW RATE: 0,72 HM3/YEAR 1.COLLECTION AND PUMPING - TANK COVER - (LEVEL 212,80) - FLOW RATE: 1,94 HM3/YEAR (31,23 L/Y TO 102,98 L/S) IN WATER PUMPING REGIME 12 NOCTURNAL HRS 2. AERATION CASCADE (LEVEL 212,80 A LEVEL 201,75) 3. WATER INLET COMPARTMENTS OF THE RABAL AND EBRO RIVER - (LEVEL 201,75) 4. GRAND CANAL RESERVE -PRIMARY DEPURATION DECANTATION - AREA: 12000 M2 - VOLUME: 18000M3 - WIDTH. 25M - LENGTH: 480 M - DEPTH: 1,50 M - IRRIGATION INTAKE FOR ENCLOSURE OF PARK- MAXIMUM IRRIGATION FLOW RATE 50% OF JULY TOTAL:17,18 L/S 5. SUPPLY OF IRRIGATION WATER AND LAYERS TO EXPO PREMISES- (LEVEL 201,75) - FLOW RATE: PEAK 56 L/S, AVERAGE 36,42 L/S (3147 M3/DAY) - IN 12 HR NOCTURNAL PUMPING REGIME 6. SECONDARY TREATMENT AQUEDUCT - (LEVEL 201,80 A 201,10) - AREA: 7845 M2 - VOLUME: 1989,50 M3 - WIDTH: 8 M - LENGTH: 605 M - DEPTH: 20-30 CM Y 60-80 CM - FLOW RATE: FROM 21,40 L/S TO 48,33 L/S 7. AERATION CASCADE - (LEVEL 201,10 A 197,00) 8. PLAZA DEL AGUA LAGOON - TERTIARY TREATMENT BY LAGOONING 9. AERATION CASCADE - (LEVEL 197,00 TO 195,35) 10. LAGOONS (LEVEL 195,35) - AREA: 3663,10 M2VOLUME 2395,70 M3 13. CANAL 2 (COTA 195,35) - AREA: 3563,10 M3 14. DITCH (LEVEL 197,00 TO 196,00) - AREA: 667,20 M2 - VOLUME: 133,40 M3 - FLOW RATE: 10 L/S 15. WHITE WATER CANAL 16. NAVIGATION BASE - (LEVEL 195,35) - AREA: 5896,70 M2 - VOLUME: 5265,90 M3 17. NAVIGATION BASE - AREA: 9199,80 M2 - VOLUME: 7189,40 M3 18. NAVIGATION BASE - AREA: 7890,80 M2 - VOLUME: 6415,30 M3 19. SWIMMABLE POND - (LEVEL 195,35) - AREA: 2584 M2 - VOLUME: 1409 M3 20. IRRIGATION POND - AREA: 4415 M2 - VOLUME: 8163,40 M3 - IRRIGATION FLOW RATE 50% OF JULY TOTAL: 17,18 L/S 21. INFILTRATION LAGOONS 22. WATER GAMES

The park will remain partially accessible during the extraordinary flood event at 50 years, when the paths that run along the canals at a higher level will provide access to “plots” that are raised above the current ground level. This is where the most delicate uses are located, which will be available at any time of year. Finally, the 100- and 500- year floods will submerge the meander nearly entirely, like before the intervention, and only the tops of trees and the main built elements will be protected. The aqueduct will remain above the water level, preserving the plant- and mineral-based water treatment system and providing an unusual overlook above the moving waters of the Ebro river overflowing its banks.

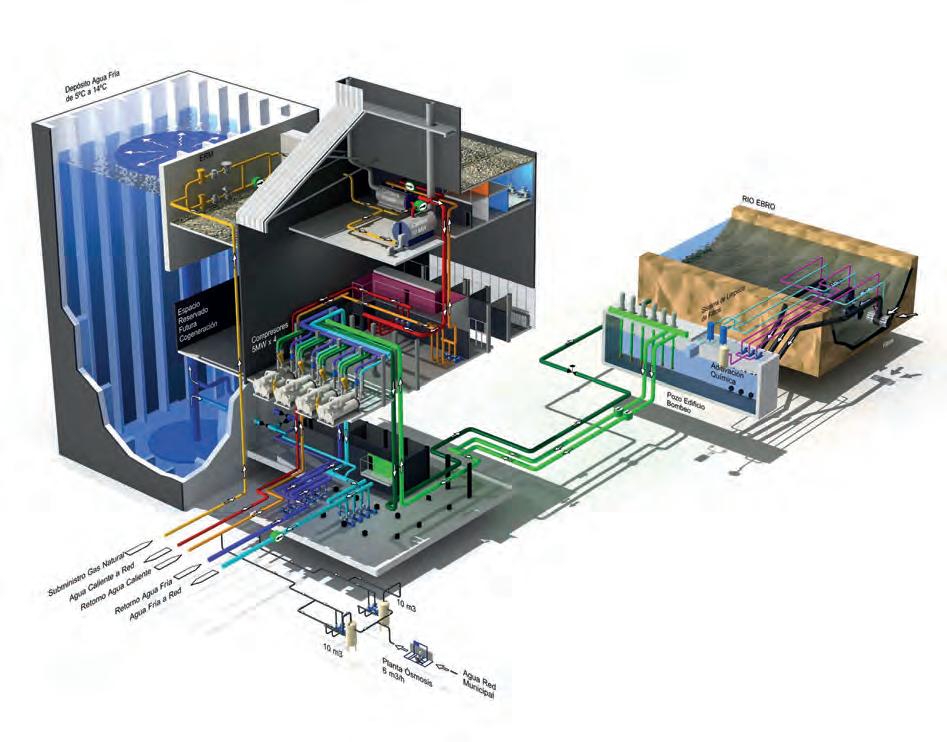

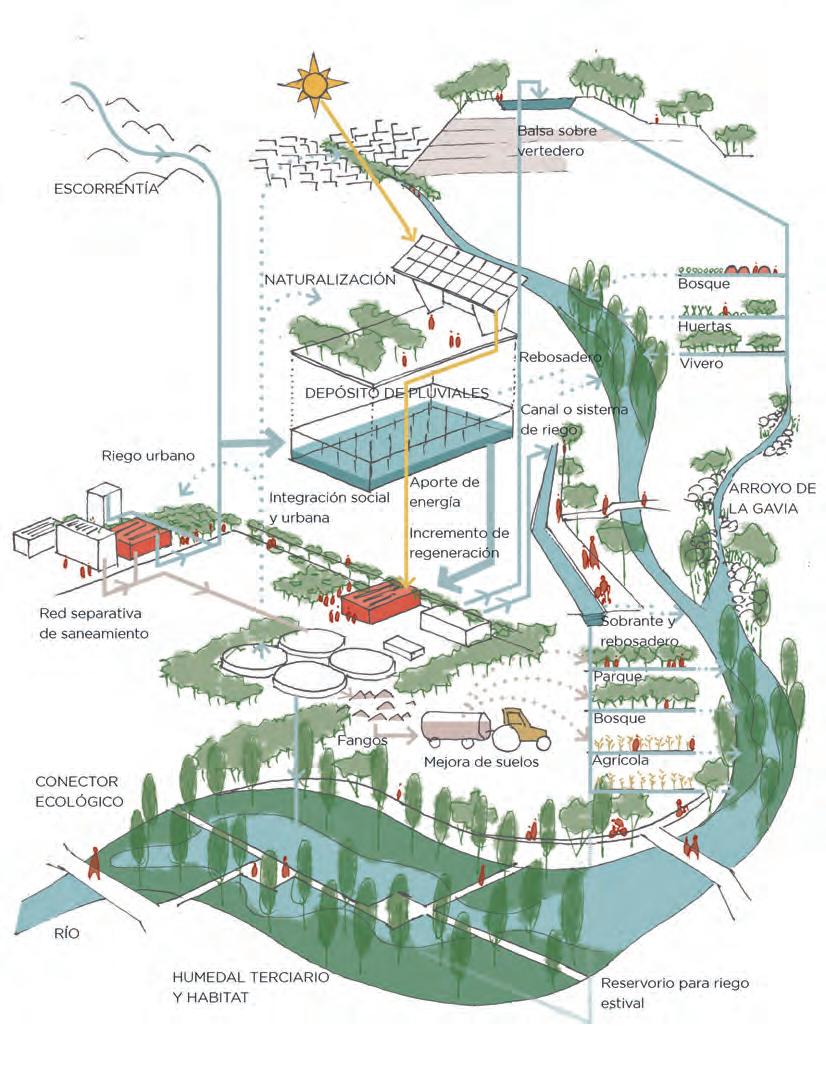

The park’s water system

Like a spine, the treatment and transport of water from the Ebro River and the Rabal irrigation canal organizes the activities along the 2.5 km of the park, qualifying spaces for different uses. The water is collected, its quality is improved using green filters, it is used for swimming and boating, it is recycled for irrigation, and it is returned to the river via infiltration, aiming for maximum water surfaces and minimum consumption. During this complex itinerary, the water also undergoes a gradual progression, equated with other similar processes that take place in the park: from the loud rushing water in the areas nearest to the city toward the calm, mirror-like natural surfaces in the swimming area; from the main canal reservoir to the natural state of the river. A living, self-sufficient system is organized, which cleans the water that is removed to transfer it into the swimming areas. Later, continuing this process, it is put back into the river through a series of infiltration basins set among the trees, generating a vibrant natural habitat.

The water system is organized to harness the preexisting agricultural layout: the irrigation ditches are widened to be used as navigation canals, recycling the formal structure of the meander. The circuit begins with a large rectangular canal, measuring 25 x 400 meters, at the

113

Power Plant and Infrastucture Buildings

140

POWER PLANT Buildings Buildings

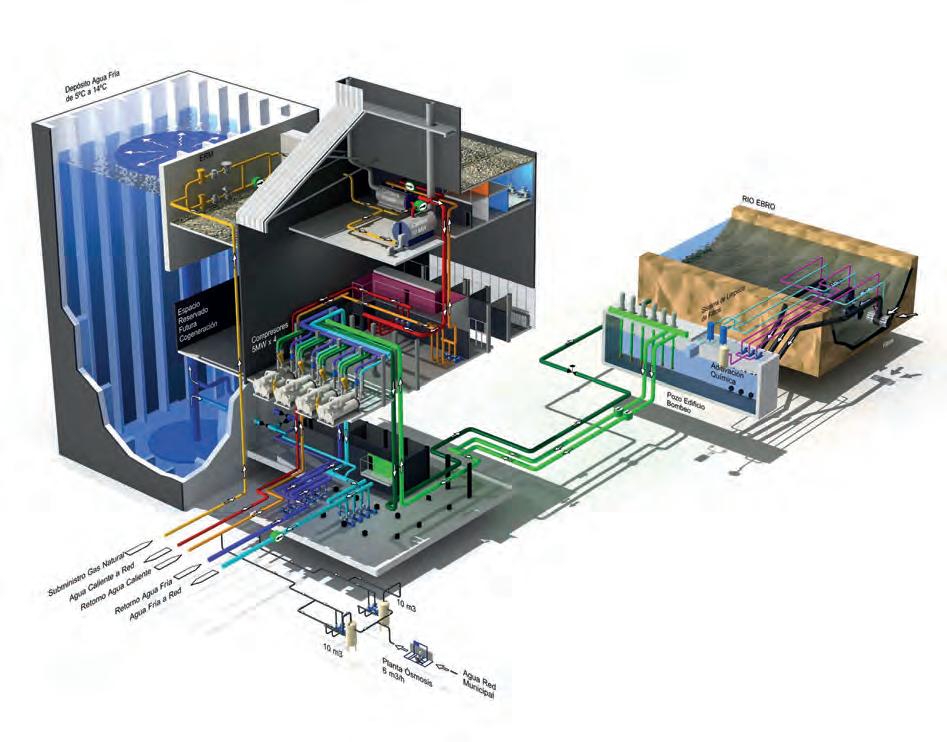

The project for the Water Park – designed for the city of Zaragoza, Spain, in the context of the 2008 International Exhibition – not only had to respond to significant territorial and landscape challenges, its broader structures also had to accommodate the necessary transition between the complex urban systems of the adjacent, densely populated neighborhood of Actur and the natural features of the Ranillas meander. In order to achieve this ambitious goal, the project for the Water Park outlined a gradual progression from the city to the river that begins at Avenida de José Atarés. Before the intervention, this street marked a clear boundary between the artificial and natural spheres. The dividing line of the former Avenida Atarés, renamed Boulevard de Ranillas, comes to be understood as a wide urban strip that forms a permeable junction. A threshold on a monumental scale to enter the Water Park from the city, it is comprised of three elements: a structure of trees that anticipates the silver forest of the Water Park; a 25-meter-wide canal that is crossed by floating bridges; and a geometric urban area connected to the neighborhood, which, nonetheless, breaks away from the line of the road to incorporate buildings – such as the Power Plant and Video Art Center – with façades that

face both the park and the city.

This new urban planning framework contains, from north to south, the infrastructure buildings for the park and the meander, the police station, the supermarket and the offices for the International Exhibition, as well as the United Nations Water Secretariat. Located within this new built threshold is a sequence of three buildings that provide services for the Water Park: The Power Plant and Video Art Center, the Transformer Substation (SET) and the Park Administration Building for the park’s management. These buildings are all dedicated to the generation and transformation of energy, or the catchment and management of water from the Ebro River, which supplies the park and guarantees its successful operation. The arrangement of this infrastructural triad forms most of the park’s façade, in addition to being one of the first built volumes at one of the most strategic entrances to the city.

The intense technical requirements for installations of this type would generally be associated with a peripheral site, removed from urban routes. Such infrastructures would be situated in more industrial environments, or strategies would be designed to hide them, limiting citizens’ visual and physical access to them. Instead, here they are not hidden but are

given an urban quality, responding to a clear desire for visibility, having accepted that their presence is necessary and that the flood-prone nature of the site makes it impossible to hide them underground. As such, the three infrastructural facilities are organized as part of the overall layout of built volumes. At the same time, they are rendered easy to understand through the possibility of public access and the expression of their function on the exterior, in a display of non-literal transparency with regard to the function and content of each volume.

141

LOCATION OF THE BUILDINGS IN THE WATER PARK

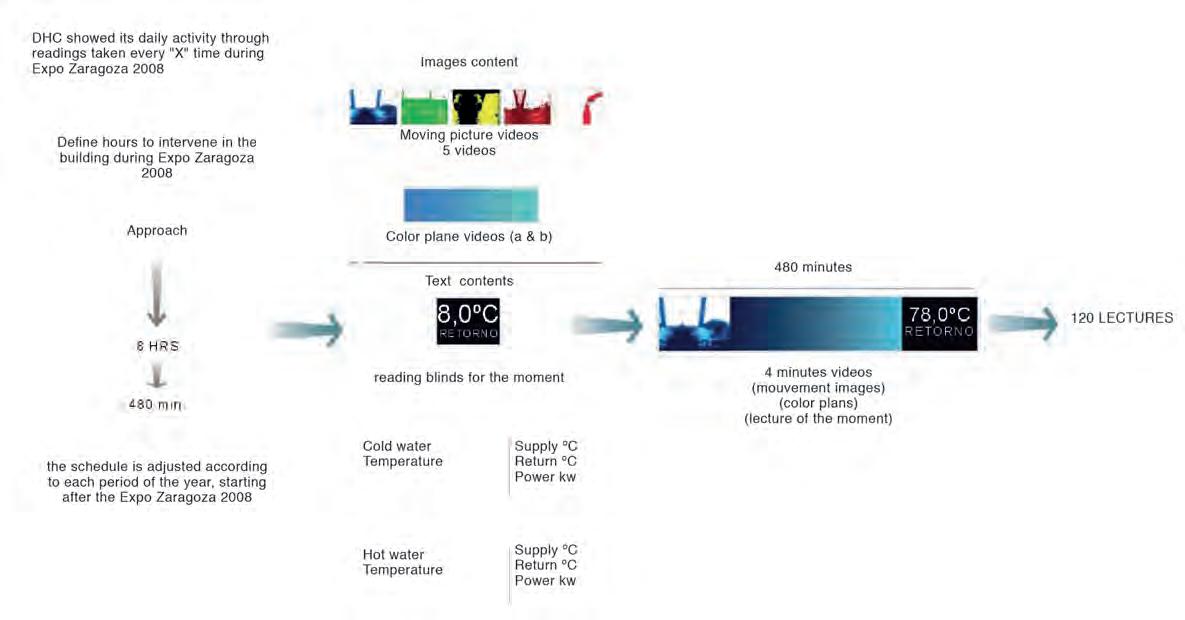

Power plant and video art center

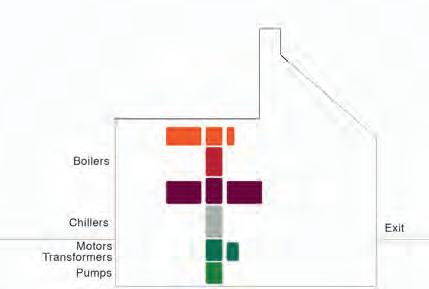

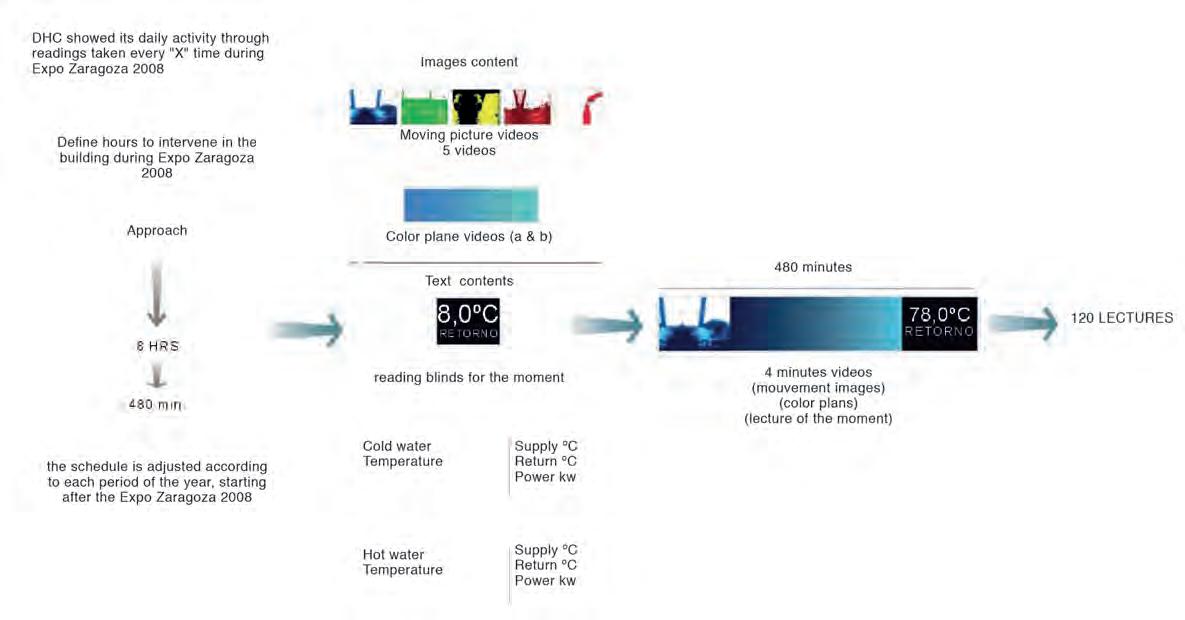

The power plant building (district heating and cooling, DHC) is designed as a trigeneration plant that will provide cooling and heating to all the new buildings in the Ranillas Meander, in addition to cogenerating electricity that will eventually be fed back into the grid. These programmatic characteristics ultimately spell out a highly complex program with significant requirements in terms of safety and insulation. Its location between the Water Park and the neighborhood of Actur, very close to the river, defines its role as a public facility that is open to the city, without hidden back façades or service yards. The desire to make this infrastructure into a link between the workings of the park and the residents of the city is realized through two strategies: first, by generating a safe interpretive path for visitors; and, second, with the inclusion of a public video art program. The technical requirements for the power plant make construction using in situ concrete a necessity, for questions of safety, soundproofing and structural requirements.

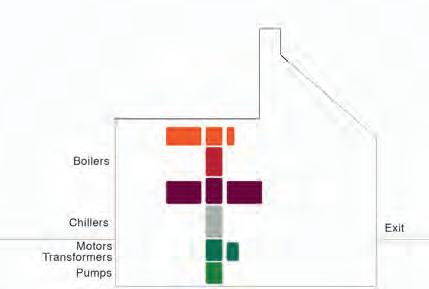

The power plant consists of a large semi-underground water tank (11,000 m3) and an adjacent volume containing the engine room. The pumps are located

in the sub-basement (-2), the electric transformers, motors and chillers are on the ground floor, and the control station and boilers (five units of up to 60 tons each) are located on the second floor. The building is made of exposed black-colored concrete both inside and outside, with a load-bearing envelope that is 30 cm thick. The exterior finish is given a noticeable corrugated texture, which draws attention away from the edges of the formwork and the imperfections. The black color adds nuance to the contrasts between light and shadow and adds complexity and variability to the final texture. The interior can be visited through public paths on a mezzanine level, defined by a color scheme that reflects the different kinds of energy, contrasting with the black of the engine room. In the lightweight roof of the boiler room – built with corrugated polycarbonate for safety reasons, due to the risk of explosion or gas leaks – a matrix of LED lights generates a sequence of images, generating a digital vision (as opposed to a literal view) of the room’s contents and operations. This large 20x20-meter video surface is complemented by another at ground level (4 meters high and 30 meters long) with the same characteristics. The Power Plant sends data to the video software detailing

the type of energy being produced and its proportions throughout the day and the different seasons, controlling the video art images in an installation created by Eulalia Valldosera. At night, when the installations are closed to the public, the black building disappears and the images of the artwork on the outdoor polycarbonate panels become detached, floating among the trees of the Water Park. New videos will be added to the collection to be screened at festivals and events. Between the video art pieces, the media façade provides ongoing information about the production of energy and the facility’s performance, providing public accountability. The original concrete building thus becomes partially transparent, in a sort of experimental piece that uses digital processes (as opposed to material ones) to express and communicate the production taking place inside.

142 Buildings

Power Plant and Infrastucture Buildings

143 HEATING AND COOLING SYSTEM

Green Diagonal Park

246

Cities

SOURCE: BSAV. SOCIETAT BARCELONA SAGERA ALTA VELOCITAT

Morphology of Barcelona, a geographical city

The Romans founded Barcelona on a plain with a soft slope oriented towards the southeast and surrounded on four sides by important geographic features: to the southeast the Mediterranean Sea; to the northeast the Besòs River; to the southwest the Llobregat River; and to the northwest the Collserola mountain range. Currently, the metropolitan area of Barcelona has 3.5 million inhabitants, although the municipality concentrates 1.5 million in just 100 hectares. It is one of the densest cities in Europe, with hardly any parks.

Growth of the city and Idelfons Cerdà’s design for the Eixample

Barcelona was founded as Barcino between 15 and 10 BC, initially with the urban form of a castrum and, later, an oppidum. This configuration remained almost entirely intact throughout the Middle Ages and with very few changes up until the 19th century, when the city began to densify, eventually becoming an insalubrious metropolis with high mortality rates. Despite the booming economy that attracted immigration from rural areas, for political reasons the city was unable to tear down its walls and expand until the final decades of the 19th century. Once expansion became possible, the city grew rapidly in keeping with the plan for the Eixample, across what was essentially an agricultural plain, almost entirely devoid of constructions. Ildefons Cerdà coined the word “urbanization” in his treatise General Theory of Urbanization, in which he proposed a regular square grid for Barcelona with 100-meter sides and a network of 20-meter-wide streets. The only exceptions to this network were five 50-meter-wide streets, which he called “transcendental roads”: Passeig de Gràcia; Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes; Avinguda Diagonal; and the last two, eminently geographical in nature, Avinguda del Paral·lel and Avinguda Meridiana [parallels and meridians]. The 90-degree intersection

of the latter two coincides at a point in the port where a clock tower marks its position. Although contemporary Barcelona is hyperdensified, the Eixample plan allocated more than half of the surface area for public green space, where the “transcendental roads” were meant to “connect the city with the world”. In the early 20th century, this grid made it easy to accommodate an increasing density – by eliminating the planned green spaces, and the roads that had been desiged for more primitive modes of transport ended up succumbing to the hegemony of the automobile. The city was once again trapped – not by walls, but within its geographical limits, with high levels of environmental pollution and very few green spaces. The ideas from Ildefons Cerdà’s plan for the Eixample (1860-70) are essential in the conception of the Park, especially with regard to its transcendental roads.

Urban plans and projects from 1888 to 2018: from The Ciutadella to The Green Diagonal Park

Historically, Barcelona has been able to develop urban plans at the right time to take advantage of public and private investments associated with international events. In the 19th century, such events were understood by the emerging industrial bourgeoisie as opportunities for investing their capital, not only in pursuit of an economic benefit, but also in the interest of improving the city. The bourgeoisie had the necessary financial wherewithal to support the urban development of Barcelona’s Eixample and was willing to continue investing in new projects. The sequence of events surrounding the 1888 and 1929 World’s Fairs were proof of this. In 1888, the military citadel was transformed into an urban park outfitted with a variety of facilities, the Parc de la Ciutadella. In 1929, a new fairground was built at the foot of Montjuïc, near Plaça Espanya.

Following the instability of the 1930s, marked by social, economic and political crises in the Western world, Spain was

plunged into a civil war (1936-39) and then a 40-year dictatorship that overlapped with the Second World War. When the dictator died in 1975, and after a period of transition, democracy was restored and the Statutes of Autonomy were established, which grouped together provinces with their own historical entity under autonomous governing bodies, one of which was the Generalitat de Catalunya (Barcelona). In this political context, the city of Barcelona, in alliance with a dynamic political class and Barcelona’s architecture school, began preparing urban renewal plans to take back public space as a fundamental sphere for all citizens – a space which, under the dictatorship, had been a sphere of oppression, where freedom of opinion and free will were all but impossible.

These plans and projects took shape in the early decades of democracy in keeping with the notion of “monumentalizing the outskirts”, building exquisitely designed public squares in all neighborhoods but also laying out more ambitious plans for a renovation of the entire city, including the historic center. Many of these plans came to a head with the opportunity provided by the 1992 Olympic Games, under the leadership of the city’s chief architect, Oriol Bohigas and the mayor Pasqual Maragall. This event served as a catalyst for the investment required for opening the city toward the sea, reorganizing vehicle traffic with the construction of the ring roads, refurbishing the old city with the renovation of public spaces in the Gothic Quarter and the Raval neighborhood, and consolidating the public squares in the neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city. It was a smalland large-scale urban operation that has since been studied around the world and has generally been deemed successful. After 1992, the next big event was the Forum of Cultures (2004), which, despite certain difficulties and perhaps a few mistakes, fueled the development of the area where Avinguda Diagonal reaches the sea, and the final stretch of beaches between the Olympic village (Vila Olímipica) and the Besòs River, including the ecological restoration of the river.

247

258 Cities

VEGETATION SCHEME LANDSCAPES SCHEME CONNECTIVITY SCHEME CIVIC AXES SCHEME SMART SCHEME Green Diagonal Park

Cross-cutting civic axes

Visitors who arrive at the new Green Diagonal Park by train from other places, biking down from the mountains, or walking in from the city will experience how the old scar of the railway has given way to a welcome green carpet, where the surrounding neighborhoods can see a reflection of their identities. The neighborhoods that run from Sant Andreu to La Sagrera have never had any connection with the areas of Sant Martí and Bon Pastor. Now is the time to bring them together, to connect citizens and make the park into a meeting point, a communication link. The design focuses on aligning the urban fabrics, which range from the orthogonal grid of the Eixample, in the Bac de Roda area, to the fabric of Sant Andreu, Sant Martí or the novel layouts of the new areas along the borders. A system of cross-cutting paths is implemented. They are straight, narrow and with parallel edges – structured like a fishbone – prioritizing

functionality and connectivity. They create nine key civic axes through which the park will interact, actively participating in the socioeconomic reinvigoration of the area: Green Diagonal - Camí Comtal Park - Les Glòries - Ciutadella - Mar; the historic road in Sant Martí de Provençals - Gran de Sant Andreu; the social axis Pegaso - Sant Martí; les Rambles Onze de SetembrePrim; the cultural axis of Fabra i Coats; the Forums of Sant Andreu - La Maquinista; the modern heritage axis of GATEPAC; the water network of the Rec Comtal - La Trinitat; and the corridor Camí ComtalBesòs - Pirineu Comtal.

Playgrounds

The Green Diagonal Park aims to construct the cultural landscape in a palimpsest of natural and artificial elements. The play areas for all ages will be strategic elements in cementing the link between citizens and the new infrastructure with

its range of uses. Over the length of the park, spaced approximately every 400 m, there will be a series of play areas, understood as milestone-spaces, which will offer unique types of play for collective interaction. Each play area will have its own specific design, incorporating slides, zip lines, sandboxes, spaces for hiding or climbing, digital interaction elements, graphic elements, apparatuses for stretching or different types of physical exercise, as well as spaces for resting, drinking fountains, and spaces in the shade and in the sun. To reinforce the idea of continuity in the design of these play areas throughout the park, the projects will use the same vocabulary and materials. In developing the fencing for the children’s areas, we tried to use topographical and landscape strategies in order to minimize the effect of confinement, fostering instead the feeling of playing in the countryside, without sacrificing security.

259

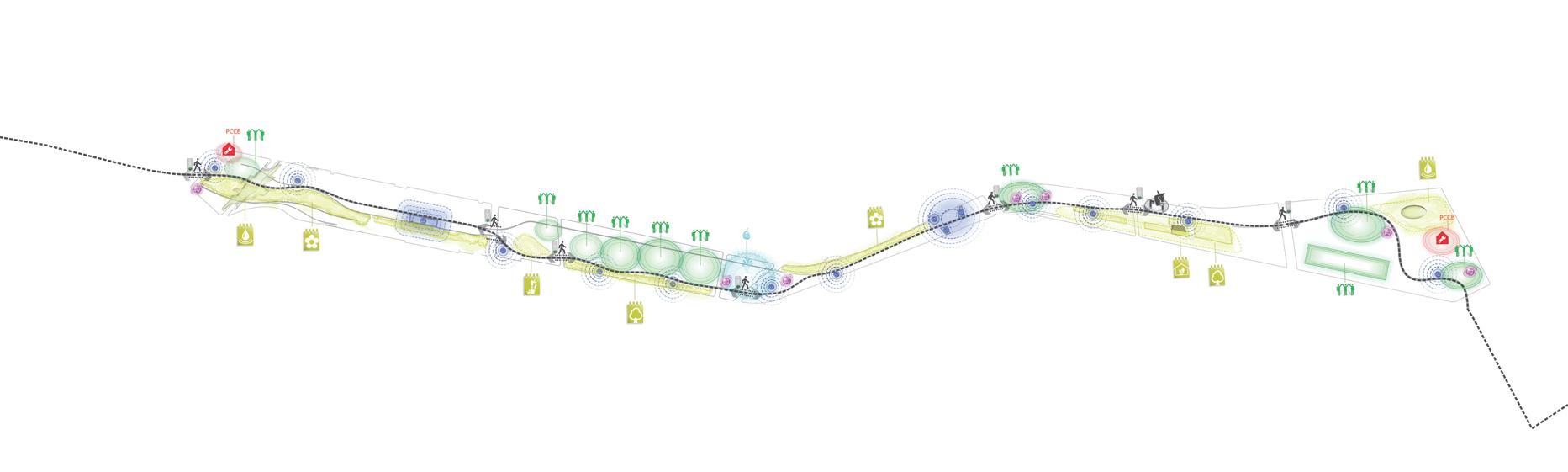

Madrid Metropolitan Forest: The Southern River Parks

Rivers

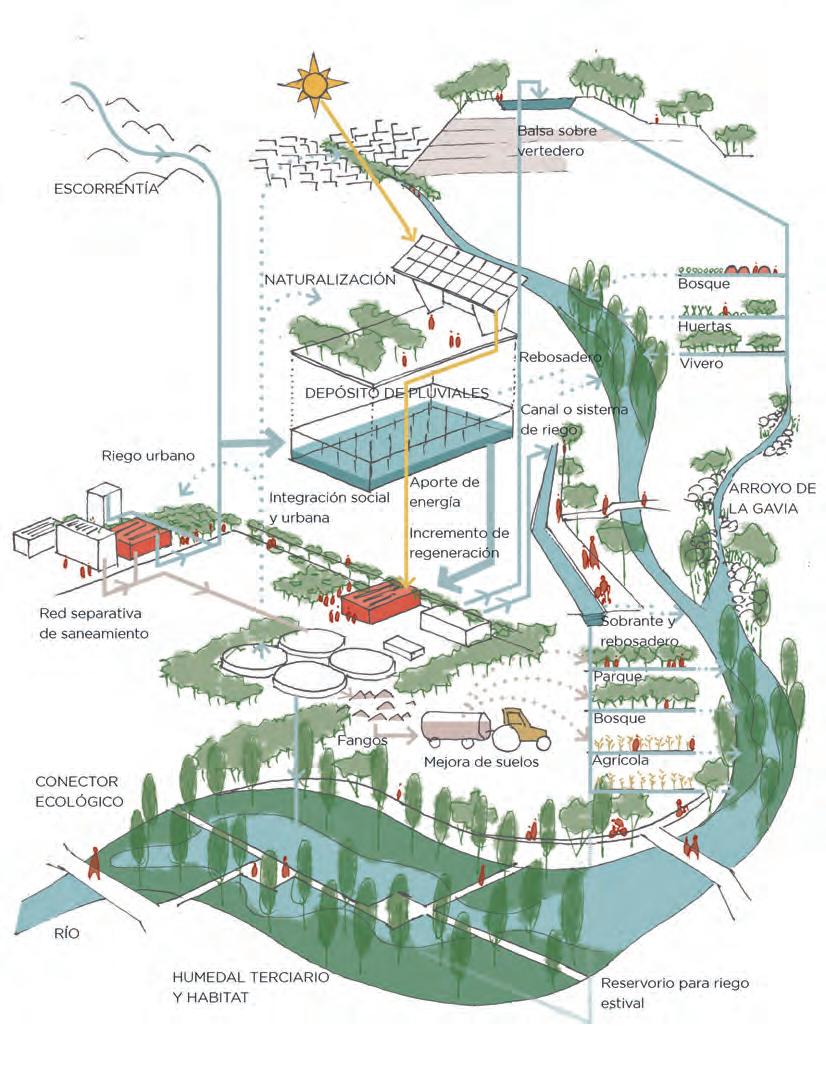

Southern spring, generated infrastructure

The transdisciplinary proposal was the winner of the International Competition for the Metropolitan Forest of Madrid, Lot 4 “The Southern River Parks”. A jury made up of 24 experts selected Manantial Sur, Regenerated Infrastructure for being a “complete project in all its components that has generated debate about the role of water, forestry and agriculture”.

The Metropolitan Forest. A forest belt that bypasses the city of Madrid, relying on existing green areas and those classified by urban planning to achieve a green corridor that will run within the municipality and the edge of the municipal term, always seeking the greatest possible ecological and spatial continuity, in coexistence with the multiple infrastructures that have historically been occupying and dividing that territory.

The proposal for the green belt of Madrid, the first major metropolitan intervention to mitigate the effects of climate change, is born with the aim of recovering

degraded spaces and increasing afforestation / reforestation and providing universal access to public space. A Forest that responds to socio-ecological challenges, using water as the driving force for project and planning. A project under the framework of the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals (ODS)

“The Southern River Parks”.

Lot 4

The area of Lot 4 corresponds to the area located to the south of the city, comprising the areas of the Manzanares Linear Park, the Arroyo de La Gavia and the hills that surround it and the agricultural border of Madrid with Getafe.

In addition to its peripheral location, the southern Manzanares basin and its topography have been used as one of the main entry routes for the major mobility infrastructures of the city of Madrid, and in its condition as the city’s “drain”, as ideal location for treatment plants. The social

consequences of having taken advantage of these conditions have been the accumulation of neighborhoods with the lowest per capita income in the city, located in these less comfortable areas and, on many occasions, with a deficit of public facilities. The Metropolitan Forest is the opportunity to change the perspective of these facilities. Make them positive and even take advantage of them to introduce some equipments of not only metropolitan scale, but also local.

The southern area of Madrid along the Manzanares riverbed is a place of infrastructures that have divided the territory; but it is also a space of opportunities, full of resources, not only water and ecological linked to its channels, but also historical, agricultural, horticultural, archaeological and social to expand and re-growth.

319

MANANTIAL SUR. ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL ENGINE OF THE SOUTH OF MADRID

There is no landscape without water, a good landscape project is not one that paints a green space, nor one that builds large architectural ‘follies’ in a free space. A good landscape project is a water, soil, vegetation and other –social, historical and patrimonial- resources management project over time.

The design of water management is the skeleton that allowes the construction of a monumental landscape that this area of the city deserves. The designed water system is an artificial and natural hybrid that has three sources: gravity drainage from rainwater runoff, upstream river intakes for orchards, and water from the treatment plants.

‘Manantial Sur’ is a proposal for social and ecological-landscape growth: The social growth recovers pedestrian connectivities and creates civic centralities. The ecological growth promotes the conditions for the emergence of fauna and flora biodiversity as well as a large monumental forest based on better use and management of water resources. The growth of mobility infrastructures comes from understanding them as broad ecological corridors that make up an agroforestry and social mosaic.

It is an opportunity for Madrid to rethink its green territory as a manager of water and nature, creator of microclimates, promoter of healthy habits and transformer of treatment plants into new springs that generate more life.

322 Rivers

SCHEME OF CLOSED WATER, PRODUCTIVE AND SOCIAL CYCLES

A SPRING IN MADRID. NATIVE AND DIVERSE HABITATS

Madrid Metropolitan Forest

323 PROPOSED MAIN HABITATS

Essays

MARGARITA JOVER

“In a line, the world comes together; with a line, the world is divided. Drawing is both beautiful and terrible.”

Drawing as a medium

Using architectural drawing as a medium, one can operate in three different ways. If we classify them according to their role, beginning from the most public sphere and ending with the most private, first we have the drawings that are drafted as instructions for construction: a precise tool to communicate the form and material qualities of the design. Next, there is the drawing as a graphic medium to express different architectural ideas for different audiences. Finally, in the studio or in more private spheres, there is the drawing as the expression of an intuitive pursuit to explore ideas. In each of these three roles, the drawing takes on different levels of resolution, where resolution is understood as the amount of information necessary to communicate certain ideas. Depending on the category in which the drawing is operating, certain aspects of the architecture will have high levels of resolution, and others will have very low levels of resolution.

In the first level of drawing, which belongs to the more public spheres and is used to communicate the construction of a building, the drawing shows high levels of resolution in technical aspects such as form, materials, costs or methods of assembly; at the same time, it loses all resolution in the information associated with understanding the architectural object as an urban element. On the other

hand, the second level of drawing can synthesize the urban role of a building very well, but it omits entirely any information related to material qualities. This second type of drawing sometimes acts like a thematic diagram or compass; other times it takes the form of a poetic act that clearly reflects a specific aspect of the architectural reality. On that same second level, perhaps the most complex, we find different families of architectural drawings that aren’t a means to physically build an object, but rather an end in themselves to communicate architectural ideas. We find diagrams in plan, in section, and other two-dimensional montages with high levels of resolution in various spatial, material and cultural aspects of the architecture. The third level of drawing is an investigation; it asks questions of itself as it is produced. Its relationship with thought is immediate. It is a drawing that tries to capture the ideas flowing through the drawer’s mind. It encircles them, pursues them, and works by trial and error. This type of drawing can operate in plan or in section, in any abstraction of reality, in an iterative way. Each iteration questions the others, obtains a response and answers with another iteration. The process requires a means for each iteration to see the previous one and intuit the next one in a flexible space-time sequence. This is the case of explorations that are often done using layers of tracing paper in architecture studios. The degree of

transparency or opacity is critical to this process, because it defines the margin of maneuverability for operation. If the paper is extremely transparent, it is impossible to move mentally and visually beyond the present iteration. If it is too opaque, it is impossible to see the past. But if it is semitransparent, the past and the present can enter into dialogue to construct the future. These explorations operate with predefined levels of resolution, necessary and sufficient to generate the dialogue between the present, past and future formal, spatial or ideological configuration. In this context, defining the medium and the means for one’s work becomes the most significant creative task, which provides the foundation for a certain type of thought to flow.

Physical medium and digital medium

Working with traditional media, we find materials that have specific properties, like semi-transparent paper, pencils or paint; and they are imbued with certain rules that indicate possibilities and impossibilities. Working with digital media is the same. The medium has rules like a chess board: there are things you can do and things you cannot. An in-depth familiarity with each drawing software lets you understand which medium to choose for exploring one idea or another. Certain programs allow a particular kind of question and,

326

ON ARCHITECTURAL

DRAWING

Eduardo Chillida, Preguntas, 1994.

consequently, certain types of responses: i.e., formal, pragmatic, etc. In architecture schools and firms, it has been common knowledge for some time that the different programs should coexist, and the more different they are, the more leeway the human mind has to approach complex spatio-temporal and material problems. This criterion runs counter to economic interests, according to which software companies aim to monopolize the market, and with it the forms of drawing and thinking. Moreover, using all the drawing software on the market would define the operative limits of human beings when it comes to drawing, although it would also provide indications for designing new programs to explore things that are impossible with the existing ones.

Drawing as a medium for architecture by aldayjover

We understand architectural drawing as a medium that anticipates the architecture that will be built. Whether it is digital or manual, an architectural drawing describes precisely, but it only partially evokes the future built reality.

The main challenge in an architectural drawing is achieving the right amount of information, both for the purpose of construction and for evoking architectural meaning. When a drawing gives too much information with respect to its dimensions, it interferes awkwardly between the design and the future built reality. This happens frequently with perspectives that imitate reality: they contain too much information to hold up in a blueprint, and that information is very often not hierarchized. The result is visual noise that obstructs the reading of the architectural future.

Drawing entails establishing controlled degrees of lack of definition for the sake of an increased precision in understanding the drawing as a medium for use in construction as an approach to the spirit of the built work.

Design themes: the tension between materiality and immateriality

The Cultural Center in Utebo transforms the ruins of an old flour mill into a cultural center for a small town near Zaragoza in the Ebro River valley. One of the main architectural themes involves the transformation of the half-buried ruin; its shapeless and heterogeneous materiality, formed by worn adobe and stone walls, communicates the passage of time. The design aims to contrast this messy reality with the precise and tyrannical geometry of certain urban arrangements. The architectural intent is to generate an intense vibration as

327

SKETCH OF THE WATER PARK AQUEDUCT IN ZARAGOZA

DaviD Cohn is a North American critic of architecture specializing in Spain. Now semi-retired, he has been based in Madrid since 1986. He holds a Master of Architecture degree from Columbia University (1979) and a Bachelor of Arts from Yale University (1976). He was International Correspondent in Madrid for Architectural Record (USA) from 1992 to 2019, and collaborated regularly with a number of international and Spanish periodicals. He has published over 780 articles and 15 books, including “Young Spanish Architects” (2000) and monographs on Fran Silvestre, Francisco Mangado, Fernando Menis, Mansilla + Tuñón, Fraile + Revillo and Manuel Gallego, among others. In 2002 he received a Research Grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, and in 2006 he gave the Keynote Address at the Museum of Modern Art in New York for the inauguration of the exhibition “On Site”, which was dedicated to Spanish architecture. His upcoming book, “Modern Architectures in History: Spain”, will be published soon by Reaktion Books, London.

Luis FranCisCo EspLà was born in Alicante in 1957. He obtained a degree in fine arts from the Valencia School of Fine Arts. Awarded the Gold Medal of Fine Arts 2009. He is the son of Francisco Esplá, novillero (bullfighter of young bulls), and founder of the Alicante Bullfighting School, and brother to the matador Juan Antonio Esplá. He first wore the suit of lights in Benidorm on 21 June, 1974. This first novillada bullfight was followed by numerous others that same year, at the end of which he made his debut with picadores (mounted lancers) in Santa Cruz de Tenerife. His official presentation as a bullfighter took place in Zaragoza on 23 May 1976 and was validated in Madrid the following year. He has garnered major triumphs in bullrings all around Spain, and has forged a reputation as a genuine master of the art of classical bullfighting and in the suerte de banderillas. He retired from the rings in 2009 after the official presentation as a bullfighter of his son Alejandro.

Bruno DE MEuLDEr teaches urbanism at KU Leuven, is the current Programme Coordinator of MaHS and MaULP and the Vice-Chair of the Department of Architecture. With Kelly Shannon and Viviana d’Auria, he formed the OSA Research Group on Architecture and Urbanism. He studied engineeringarchitecture at KU Leuven, where he also obtained his PhD. He was a guest professor at TU Delft and AHO (Oslo) and held the Chair of Urban Design at Eindhoven University of Technology from 2001 to 2012. He was a partner of WIT Architecten (1994-2005). His doctoral research dealt with the history of Belgian colonial urbanism in Congo (1880-1960) and laid the basis for a widening interest in colonial and postcolonial urbanism. His urban design experience intertwines urban analysis and projection and engages with the social and ecological challenges that characterize our times.

330

Biographies

ELizaBEth K. MEyEr, FASLA, is the Merrill D. Peterson Professor of Landscape Architecture at the University of Virginia School of Architecture, where she has taught since 1993, also serving as Chair of the Department of Landscape Architecture as well as interim Dean of the School of Architecture. She holds degrees from the University of Virginia and Cornell University; she taught previously at Cornell and Harvard University Graduate School of Design, and practiced as a landscape architect with the EDAW and Hanna/Olin design firms. She was named one of the 25 most admired educators in the U.S. by DesignIntelligence in 2011, 2012, and 2013. Ms. Meyer is engaged nationally as a studio critic and lecturer; she has published widely on contemporary landscape design practice and theory, exploring such issues as the social and aesthetic implications of creating new parks on toxic industrial sites, and the role of aesthetics in sustainable design.

JaviEr MonCLús (Zaragoza, 1951) is an architect from the School of Architecture of Barcelona and a Doctor from the Polytechnic University of Catalonia. He is Professor of Urban Planning at the School of Engineering and Architecture of the University of Zaragoza, where he has been director of the Departmental Architecture Unit. Director of ZARCH magazine. Member of the editorial board of Planning Perspectives and Director of the PUPC Research Group (Urban Landscapes and Contemporary Project). Author, co-author or co-editor of numerous publications (more than 200) on urban theory, urban design and urban history. Among which we can mention the book Urban Visions. From the culture of the plan to landscape urbanism (Abada, 2017, Urban Visions, Springer 2018; co-edited with Carmen Díez). Many of them are part of a collective work focused on the systematic knowledge of urban forms and the architecture of cities. Responsible, together with Carmen Díez, for the research projects “Urban Regeneration of Housing Estates in Spain” (UR-HESP) (MINECO). He has developed his professional activity in urban planning as an author, collaborator or consultant. In Zaragoza, it is worth mentioning his responsibility in the Riberas del Ebro Plan and his activity as director of the Accompaniment Plan of the 2008 International Exhibition.

XaviEr MontEys is a professor at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC), where he directs the Habitar research group, and carries out his teaching activity at the Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona (ETSAB). He has taught classes and lectures at various university centers and institutions. He is a contributor to the magazines Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme, Arquine and the Quadern supplement of the Catalan edition of the newspaper El País. He is the author of various articles and books, including Casa Collage (2001, with Pere Fuertes), La habitacion (2014) and La calle y la casa. Interior planning (2017), all of them published by Editorial GG.

331

KELLy shannon teaches urbanism at KU Leuven, is the Programme Director of the Master of Human Settlements (MaHS) and Master of Urbanism, Landscape and Planning (MaULP) and a member of the KU Leuven’s Social ad Societal Ethics Committee (SMEC). She received her architecture degree at Carnegie-Mellon University (Pittsburgh), a post-graduate degree at the Berlage Institute (Amsterdam), and a PhD at the University of Leuven, where she focused on landscape to guide urbanization in Vietnam. She has also taught at the University of Colorado (Denver), Harvard’s GSD, University of Southern California, Peking University and The Oslo School of Architecture and Design amongst others. Before entering academia, Shannon worked with Hunt Thompson (London), Mitchell Giurgola Architects (New York), Renzo Piano Building Workshop (Genoa) and Gigantes Zenghelis (Athens). Most of her work focuses on the evolving relation of landscape, infrastructure and urbanization. She has numerous publications and works on design research consultancy projects, primarily to the Vietnamese and Flemish governments.

suEannE WarE is a Professor and Head of School Architecture and the Built Environment at the University of Newcastle, Australia. She holds a masters degree in landscape architecture from the University of California, Berkeley and a PhD from Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology University, Melbourne. Her most recent books include Sunburnt: Australian Practices of Landscape Architecture, edited with Julian Raxworthy (Sun, 2011) and Taylor Cullity Lethlean: Making Sense of Landscape, edited with Gini Lee (SpaceMaker, 2013). Her research outputs as creative works have been awarded national and international design accolades (SIEV X memorial, the Road as Shrine, The Anti-Memorial to Heroin Overdose Victims). Much of her scholarly and creative practice work centres on socially engaged design processes, citizen co-design, and design activism. She is a Fellow in the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects. She has been visiting professor and scholar at ETSABarcelona, Spain and at Ecole Nationale Superieure du Paysage –Versailles.

332

Iñaki Alday

Margarita Jover

Jesús Arcos

Francisco Mesonero

Contributions by:

Eduardo Arroyo

David Cohn

Luis Francisco Esplá

Elisabeth K. Meyer

Bruno de Meulder

Xavier Monteys

Javier Monclús

Kelly Shannon

Sueanne Ware

Merrie Afseth

Pablo Alós

Elena Albareda

Aroa Álvarez

Rafael Álvarez

Arnau Balcells

Teresa Baldó

Eric Barr

Lorena Bello

Pascual Bernat

Leah Bohatch

Juliana Bracchi

Paulina Baroni

Laia Boquera

Marta Castañé

Pablo Carro

Cristina Capel

María Eugenia Castrillo

Amanda Coen

Laura Collado

Ana M. Cubillos

Saida Dalmau

Andreea Dan

Caroline Dillard

Enric Dulsat

Montse Escorcell

Jorge Espinosa

Alina Fernandes

Sean Fowler

Silvia Foros

Julia Frost

Omar González

Alba Guillén

Jordi Hernández

José Manuel Herrera

Moisés Jiménez

Ryan Kiesler

Nicole Lacoste

Carla Leandro

Connor Little

Arántzazu Lúzarraga

Marilena Lucivero

Xinyu Lyu

Andreu Meixide

Susana Mitjans

Katerina Mitsoni

Shinji Miyasaki

Mario Monclús

Eliott Moreau

Carmen Muñoz

Monisha Nasa

María Nieto

Leonardo Novelo

Héctor Ortín

Ana Ostos

Anna Planas

Irene Pecharromán

Filippo Poli

Laura Paes

Rubén Páez

Paula Poveda

Rafael Pleguezuelos

Ana Quintana

Anna Ramírez

Derek Rayle

Nerea Rentería

Lucia María Rodríguez

Natalia Rodríguez

Catalina Salvà

Claudia Sanllehy

Júlia Salvia

Dolores Sancho

Marta Serra

Bruno Seve

Xiaonian Shen

Zhilan Song

Megan Spoor

Théa Spring

Gina Susanna

Cecilia Vinyolas

Joana Verd

Raquel Villa

Nina Walters

Makai Wilson-Charles

Tensae Woldesellasie

Ana Zabala

333

Authors Contributors

L’Atelier du Paysage. Christine Dalnoky. Project: The Water Park.

Burgos&Garrido arquitectos. Project: Social Housing Torre Baró.

Eric Batlle y Joan Roig. Project: Renovation of Paseo de la Independencia.

Jorge Rigau arquitectos. Project: San Juan de Puerto Rico Old Acueduct.

KLM arquitectos. Project: Buenos Aires Elevated Highway Park.

María Pilar Sancho. Project: Recovery of the Gállego River Bank in Zuera.

RCR Arquitectes. Project: Green Diagonal Park.

Vir.mueller architects. Project: Maharashtra Park and Bridge /Noida Masterplan.

West 8. Project: Green Diagonal Park.

05AM Arquitectura. Project: Ibiza Pedestrian City Center.

ABM Consulting (Hydraulic Engineer Consultant)

Artec Studio (Lighting Design)

ASEPMA (Water Solution Consultant)

Aníbal Sepúlveda (Historic Preservation Expert)

BIS structures (Structural Consultant)

Benedicto Gestión de Proyectos (Budget and Project Manager)

Bruno Remoué + associats, urbanism & mobility (Mobility Consultant)

Conrado Sancho (Civil Engineer Expert)

David Solans. Taller de ingeniería ambiental (Hydraulic Engineer Expert)

Davide Vason (Infographic)

Eva Brugal (Budget and Project Manager)

Escofet (Furniture Design)

IRBIS (Environmental Consultant)

INCO ingenieros (Engineer Consultant)

IGuzzini (Lighting Consultant)

Fernando González (Agronomy and landscape)

JG Ingenieros (Engineer Consultant)

Jorge Abad (Biology and Ecology Expert)

Josep Bonvehí (Budget and Project Manager)

LAMP Lighting (Lighting Consultant)

Pepe Lanao (Budget and Project Manager)

Level infrastructure (Civil Engineering)

Luis M. Gutiérrez (Budget and Project Manager)

Matèria Verda (Agronomy and botany)

mmcité (Furniture Design)

Paisaje Transversal (Urban Planning)

Pablo Rived (Budget and Project Manager)

PROMPT Collective (Infographic)

PyP (Systems) - Estudio Ros (Facilities Consultant)

PSC Ingenieros Hidráulicos (Hydraulic Engineer Consultant)

Randelec (Facilities Consultant)

Roser Vives Delàs (landscape & agronomy)

SBDA (Infographic)

SENER (Engineer Consultant)

Torres-Rosa Consulting (Engineer Consultant)

334 Co-authoring firms External consultants

Photographers

Jordi Bernadó

Recovery of the Gállego River Banks in Zuera –– 9, 36, 37 left, 38-43

The Water Park –– 111, 115, 120-123

Renovation of Paseo de la Independencia –– 66, 71

The Mill Cultural Center –– 28, 44, 47, 48, 52, 55

Can Mustera Farmhouse –– 56, 58, 60, 61, 63, 65 left

Mas Bassedes Farmhouse –– 240, 244, 248

Water Park Pavilions –– 124, 126, 127, 128, 129 right, 130, 131

Water Park Power Plant and Infrastructure Buildings –– 99, 133 top right, 140,141, 146, 147, 149 bottom

Agricultural Interpretation Center ––218, 220 bottom, 225 top, 225 bottom right, 226 right, 227

Residence and Day Center for People with Intellectual Disabilities –– 100107

José Hevia

Renovation of Paseo de la Independencia –– 68, 69

Zaragoza Tramway Integration –– 196, 198, 199, 203, 204, 205, 207

Water Park Pavilions –– 129 left

Water Park Power Plant and Infrastructure Buildings –– 143, 145, 147 top right, 149 top

Arbolé Theater –– 134-137

Las Delicias Sports Hall –– 10, 84, 86, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93

Las Armas Social Housing –– 74, 75, 79, 81, 83

Pedro Pegenaute

Aranzadi Park –– 162, 163, 164, 168, 169, 171

Agricultural Interpretation Center ––220 superior, 225 bottom left, 226 right, 228, 229

Eduardo Berian / Hidrone

Aranzadi Park –– 25, 158, 165,

Germán Lama

Ibiza Pedestrian City Center Images delivered by Ibiza Municipality –– 230, 232, 234, 235, 238 top right

Lourdes Grivé Roig

Ibiza Pedestrian City Center Images delivered by Ibiza Municipality –– 238 top left

Carlos Madrid

Recovery of the Gállego River Banks in Zuera –– 37, 38

Adrià Goula

Benicàssim New City Center Model –– 175

Badalona New City Center Model ––

192

Santiago Amo

The Water Park –– 117 right

Infographics

sbda –– 21 right, 150, 151, 155, 157, 174, 177, 179, 182, 183, 185, 186, 189, 190, 191, 195, 210, 212, 215, 216, 246, 254-257, 259 top, 260, 263, 266 top, 268, 273, 274, 275, 286, 290, 291, 292, 294-297, 303, 305, 308, 316-318, 322, 325

Modelmakers

AiR maquetas y proyectos

Benicàssim New City Center Model –– 175

Miquel Lluch

Badalona New City Center Model –– 192

335 Image credits

Cities & Rivers aldayjover architectura and Landscape

Publishedby ActarPublishers,NewYork,Barcelona

Authors

IñakiAlday,MargaritaJover

JesúsArcos,FranciscoMesonero

Editor

EricaSogbe

Contributors:

EduardoArroyo

DavidCohn

LuisFranciscoEsplá

ElisabethK.Meyer

BrunodeMeulder

XavierMonteys

JavierMonclús

KellyShannon

SueanneWare

Graphicdesign

ActarPro-MargaGibert

Copyeditorenglishedition

AngelaKayBunning

PrintingandBinding

Arlequin

Distribution

Actar D, Inc. New York, Barcelona.

New York

440 Park Avenue South, 17th Floor

New York, NY 10016, USA

T +1 2129662207

E salesnewyork@actar-d.com

Barcelona Roca i Batlle 2-4

08023 Barcelona, Spain

T +34 933 282 183

E eurosales@actar-d.com

Allrightsreserved

© edition:ActarPublishers

© texts:Theauthors

© drawings,photographs,andcomputergraphics: aldayjoverarquitecturaypaisaje

Thisworkissubjecttocopyright.Allrightsare reserved,inallorpartofthematerial,specificallythe rightsoftranslation,reprinting,reuseofillustrations, recitation,transmission,reproductiononmicrofilmor othermedia,andstorageindatabases.Foranysuch use,permissionmustbeobtainedfromthecopyright owner.

english

ISBN: 978-1-945150-74-6

Printed in Spain

Publication date:

March 2023