IRONCLAD

The Magazine of the A mer ic a n Civil War Museum

Volume 1/ Issue 3 / Spring 2023

An August Morning with Farragut; The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864

William Heysham Overend, 1883 Oil on Canvas. 10 feet x 6.5 feet

An August Morning with Farragut; The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864

William Heysham Overend, 1883 Oil on Canvas. 10 feet x 6.5 feet

An August Morning with Farragut

William Overend was commissioned by the Fine Art Society in London, England, to paint this massive (10 feet x 6.5 feet) painting. A British artist, Overend traveled to the United States to research the project, including sketching the USS Hartford warship, collecting photographs and uniforms, and interviewing survivors.

The design was inspired by an account of the Battle of Mobile Bay, written by J. C. Kinney in 1881. In Overend's painting, the viewer sees the ironclad CSS Tennessee on the right scraping alongside the USS Hartford after attempting to ram the wood-hauled Hartford. Sailors clamor to their stations, firing cannon at pointblank range at the Tennessee, while Admiral Farragut stands on the edge of the rope rigging in a strong and commanding pose. It was during the Battle of Mobile Bay that Farragut is credited to exclaim, "Damn the torpedoes!"; a reference to navel mines, not modern torpedoes.

A Popular Painting

Readers will notice the differences in color, vibrancy, and (on close inspection) details between the image above and the photograph on the cover. Soon after the painting's completion, reproduction prints in color and black & white were sold in England and the U.S. The original painting also toured the U.S.; shown in several cities including Philadelphia, Buffalo, Cedar Rapids, and Hartford. The painting's current home is the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT. The image above is a color reproduction print created by an unknown artist.

COVER: OIL ON CANVAS. SOURCE: WADSWORTH ATHENEUM MUSEUM OF ART

ABOVE: COLOR REPRODUCTION PRINT. SOURCE: REDDIT.COM/R/BATTLEPAINTINGS

ON THE COVER

Knickknackery

Scrimshaw Nautilus

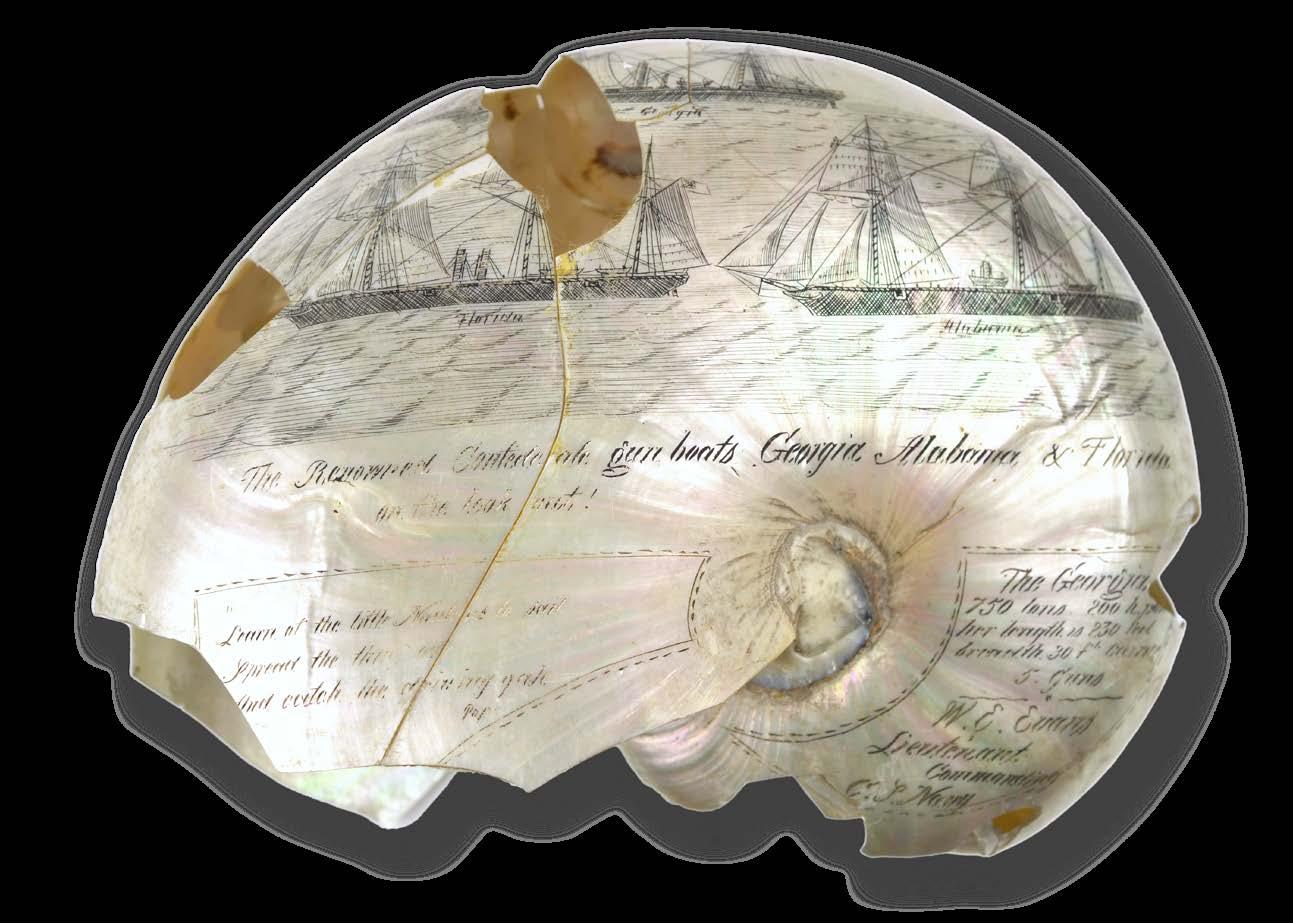

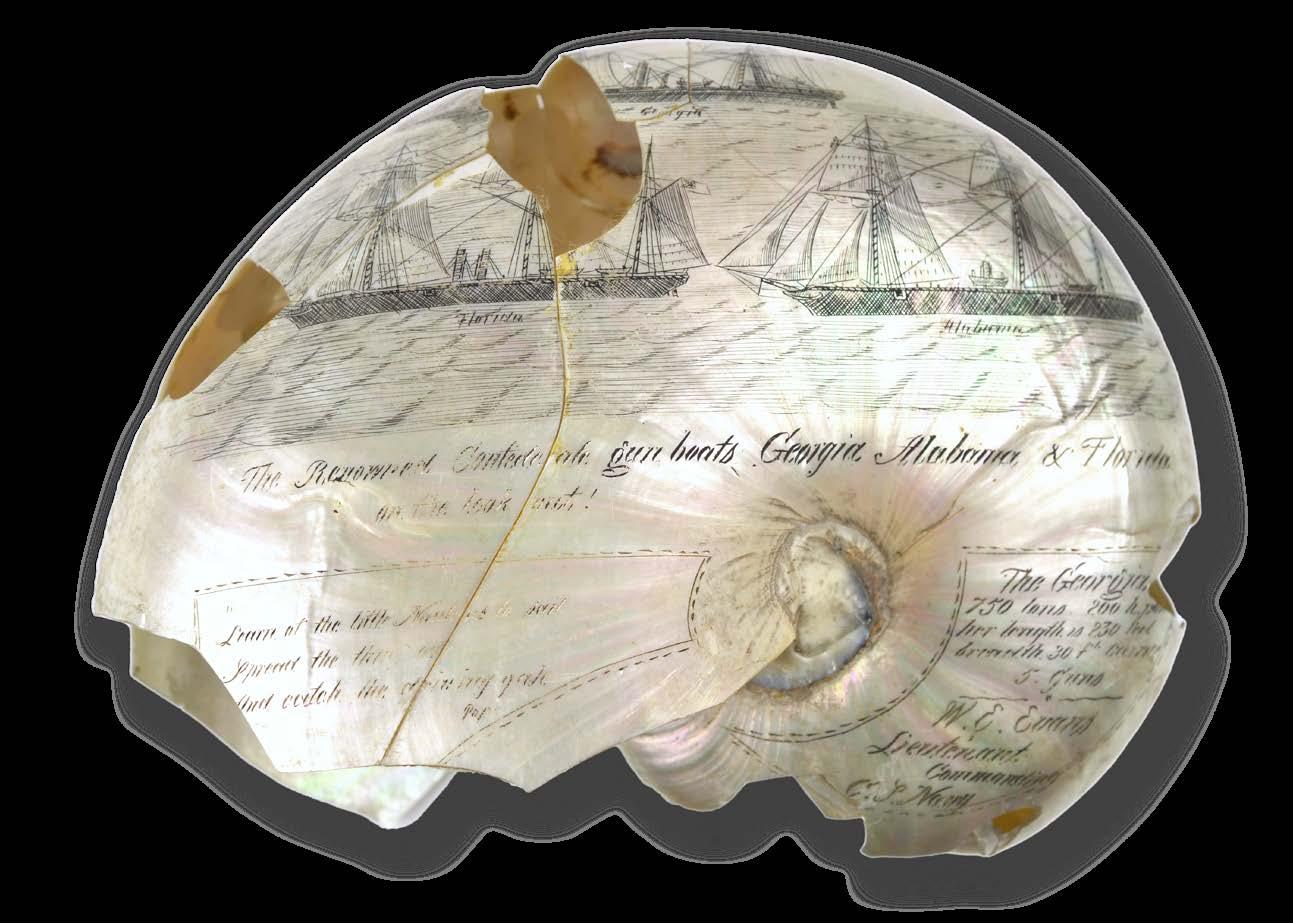

The art of scrimshaw has a long naval tradition. Sailors around the world have been applying their artistic talents to seashells and bits of bone for centuries. Scrimshaw reached its zenith of popular appeal through the work done by mariners carving away at the teeth of sperm whales.

Scrimshaw is produced by scratching or carving into the bone or shell with a jackknife or large needle, such as a sail needle. The inscribed lines are then darkened with ink or lampblack so they show up on the surface like an engraving.

A Confederate sailor aboard CSS Georgia carved this shell and presented it to Lt. William E. Evans. The scrimshaw

shows not only CSS Georgia, but also CSS Florida and Alabama, two other Confederate commerce raiders. He also included a quote from Alexander Pope:

Learn of the little nautilus to sail Spread the thin oar

And catch the driving gale

The iron-hulled Georgia was originally built in 1862 in Great Britain as a fast merchantman, utilizing both steam power and traditional sails. She was purchased by the Confederate government and converted into a commerce raider to prey on U.S. merchant ships in the Atlantic. Carrying five guns, she captured nine prizes during her short voyage from April to October, 1863.

ACWM COLLECTION

See other scrimshaw artifacts from the ACWM collection on page 27.

Magazine

Publisher

Rob Havers , Ph.D.

ACWM President & CEO

Managing Editor

Robert Hancock

Art Director/Designer

John Dixon

Editorial Review

Ana Edwards

Kelly Hancock

Jeniffer Maloney

Museum

Board of Directors

Daniel G. Stoddard, Chair

Claude P. Foster, Vice Chair

Walter S. Robertson III, Treasurer

Mario White, Secretary

J. Gordon Beittenmiller

Hans Binnendijk, Ph.D.

Audrey P. Davis

Sally Diggs Fletcher

George C. Freeman III

Hon. David C. Gompert

Bruce C. Gottwald, Sr.

Monroe E. Harris, Jr., D.D.S.

Rob Havers, Ph.D.

Richard S. Johnson

Donald E. King

John L. Nau III

William R. Piper

Lewis F. Powell III

O. Randolph Rollins

Kenneth P. Ruscio, Ph.D.

Leigh Luter Schell

Julie Sherman

Roderick G. Stanley

Ruth Streeter Foundation

Board of Directors

Donald E. King, Chair

J. Gordon Beittenmiller

David C. Gompert

Walter S. Robertson III

Kenneth P. Ruscio Ph.D.

Jeffrey Wilt

FROM THE CEO

Dear Friends

Greetings from Richmond, Virginia, and welcome to the Spring edition of our quarterly publication, Ironclad.

While the name of this publication is reflective of a host of interrelated considerations, there is a very obvious naval connection, and this edition of Ironclad has a very definite Naval theme. John Coski’s piece examines the battle of Hampton Roads, the original clash of the Ironclads. David Gompert and Hans Binnendijk, building on our mantra of “causes, course, and consequences” examine a revolution in naval affairs sparked by the Civil War. We also explore the defenses of Charleston Harbor during the war.

Looking back, we reflect on what was a tremendous ACWM Symposium 2023. Beginning the “Civil War and Remaking America” initiative, this year’s symposium amounted to a pre-quell for the next three years of lectures, exhibitions, book talks, and special programs. We were delighted to welcome a large in-person audience (25% up from last year) as well as a greater online audience, 80% of whom viewed the livestream from beyond the state of Virginia. While we have ambitious goals to grow the symposium’s in-person attendance, we are extending our reach, nationally and internationally, as part of our strategic plan. These percentages are encouraging indeed.

In that same vein, we’re delighted to announce a new partnership arrangement with the Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History. Each year GL draws together a short list of the best new works on the American Civil War and awards the Lincoln Prize, arguably the most prestigious award for writing on the Civil War. We are delighted to announce that we plan to bring each new Lincolnprize winner to Richmond to deliver the Annual Elizabeth Roller Bottimore lecture, a lecture series that has a long and storied history with the ACWM. More details to follow as we look forward to hosting this year’s dual winners of the award. Many congratulations to both Dr. Jonathan White from Christopher Newport University, as well as to journalist and historian Jon Meacham.

As always, please enjoy this edition of Ironclad magazine, and join us in person at one of our three sites or virtually at one of our upcoming programs!

Dr. Rob Havers President & CEO

Ironclad magazine is published quarterly by The American Civil War Museum. 490 Tredegar St., Richmond, VA 23219 The contents of this magazine may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the consent of the American Civil War Museum.

PHOTO: CAROLINE MARTIN

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 1

7

Charleston, South Carolina

Maritime Engagement for Control of the Confederate Lifeline

Civil War Outdoors Series

An arieal view of

Charleston SOURCE:

4.0

CONTENTS

modern-day

Pixabay.com, CC BY-SA

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 2

15 Revolutions in Naval Affairs

Bridging

1 Letter from the CEO 14 Tredegar Society: Loose Cannons 23 Knickknackery 30 Sympoisum: Photo Highlights 32 Shop: Nautical-themed books

24 Monitor

Davidson's first-hand account Ironclad Volume 1/ Issue 3/ Spring 2023 THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 3

the gulf between needed and existing capabilities.

vs Virginia Lt.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 4

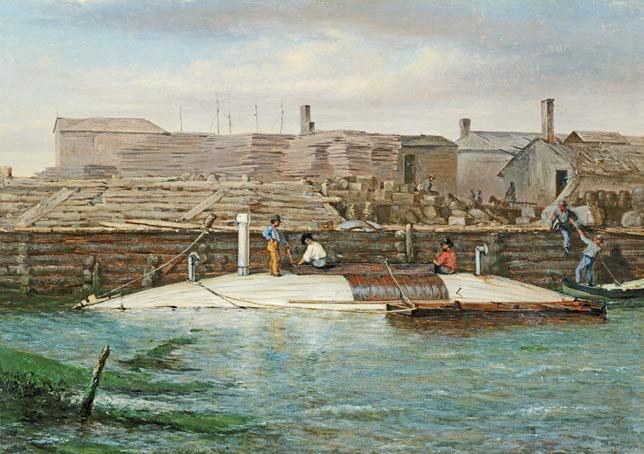

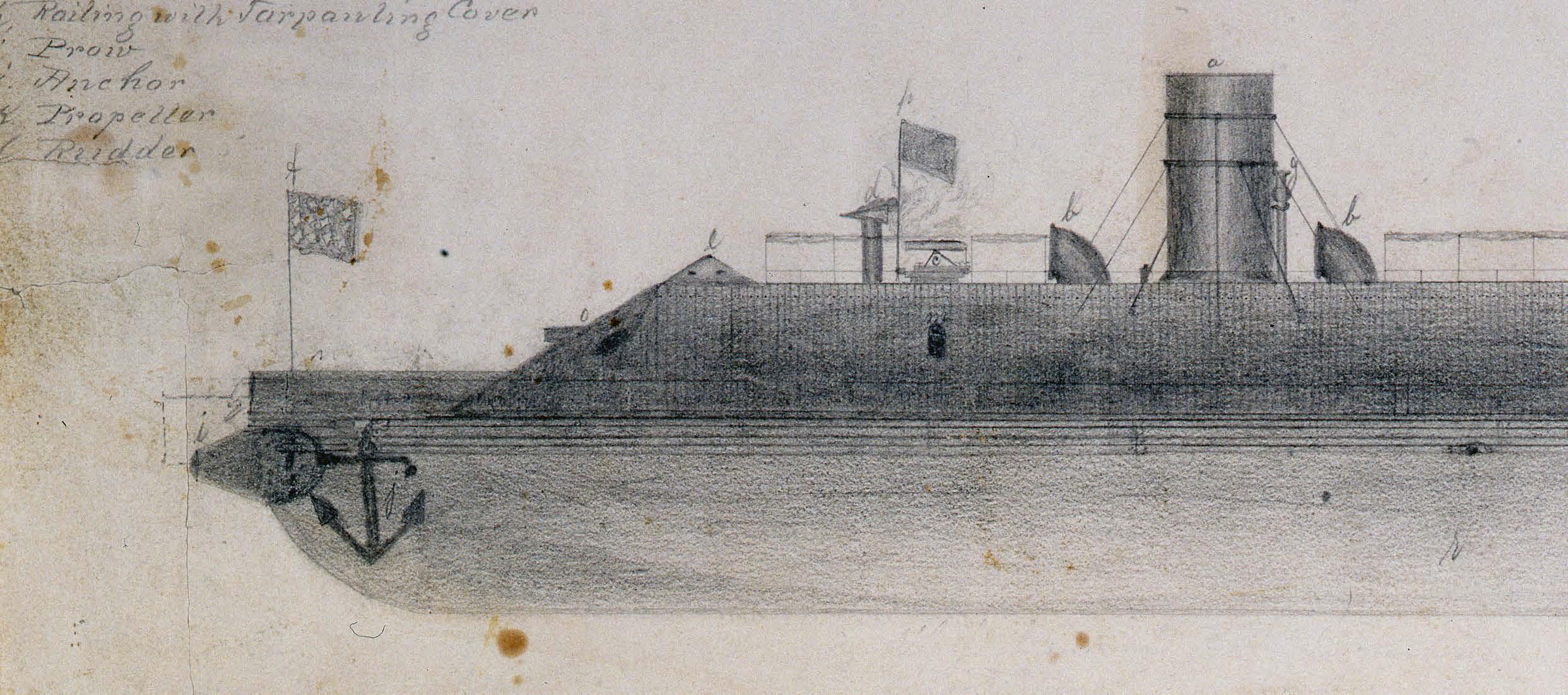

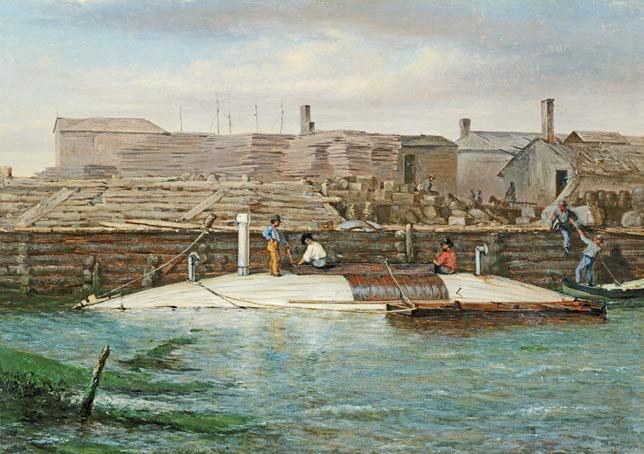

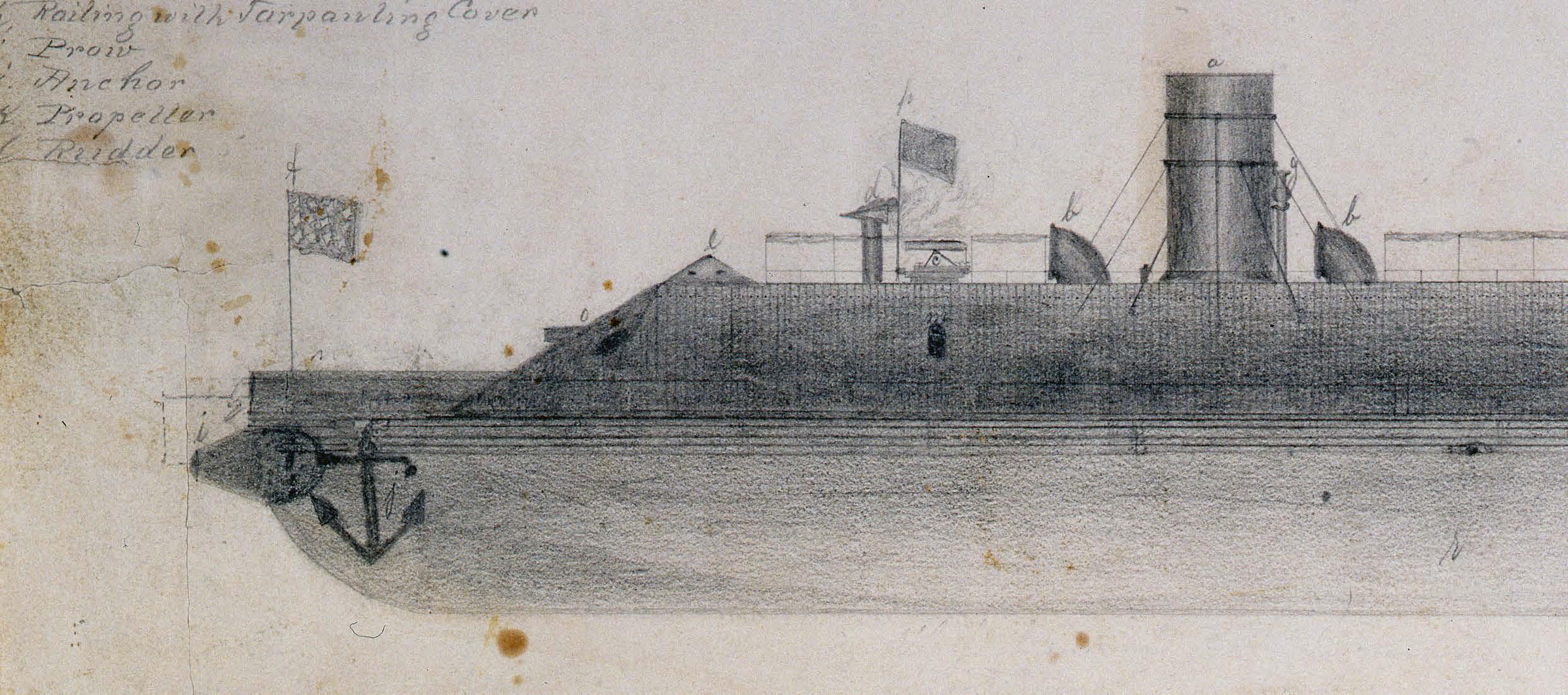

Torpedo Boat David at Charleston Dock—

Oct. 25, 1863

Conrad Wise Chapman

15.5 x 11.5 IN Oil on board

ACWM COLLECTION

Collection Highlight

Conrad Chapman, 1862 VIRGINIA STATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES

Sergeant Conrad Wise Chapman arrived in Charleston, South Carolina, in September 1863. His unit was assigned to a remote corner of the Charleston defenses, but the Confederate high command had more appropriate plans for a man of Chapman’s talents. General P.G.T. Beauregard commissioned Chapman to sketch scenes around Charleston Harbor. He subsequently took the sketches home to Rome, Italy, where his father

continued on next page

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 5

continued from previous page

lived and had a studio, and produced thirty-one finished paintings which he called his “Journal of the Siege of Charleston.”

The artist had this to say about his painting of the torpedo boat David: “This was the first torpedo boat ever constructed; it is being repaired in one of the docks of Charleston; places may be seen where the boat was struck by bullets. New plates are about to be placed in position.”

During the war, Confederate and Federal engineers and military officers experimented not only with submarines (see article “The Civil War and Naval Revolutions” p. 15), but also

Collection Highlight

semi-submersible torpedo boats called Davids (after David and Goliath). Conrad Chapman sketched the original David from life sixteen days after Lt. William Glassel used her to attack and disable the powerful U.S. ironclad vessel New Ironsides. Glassel went overboard and was captured, but the David limped back to Charleston.

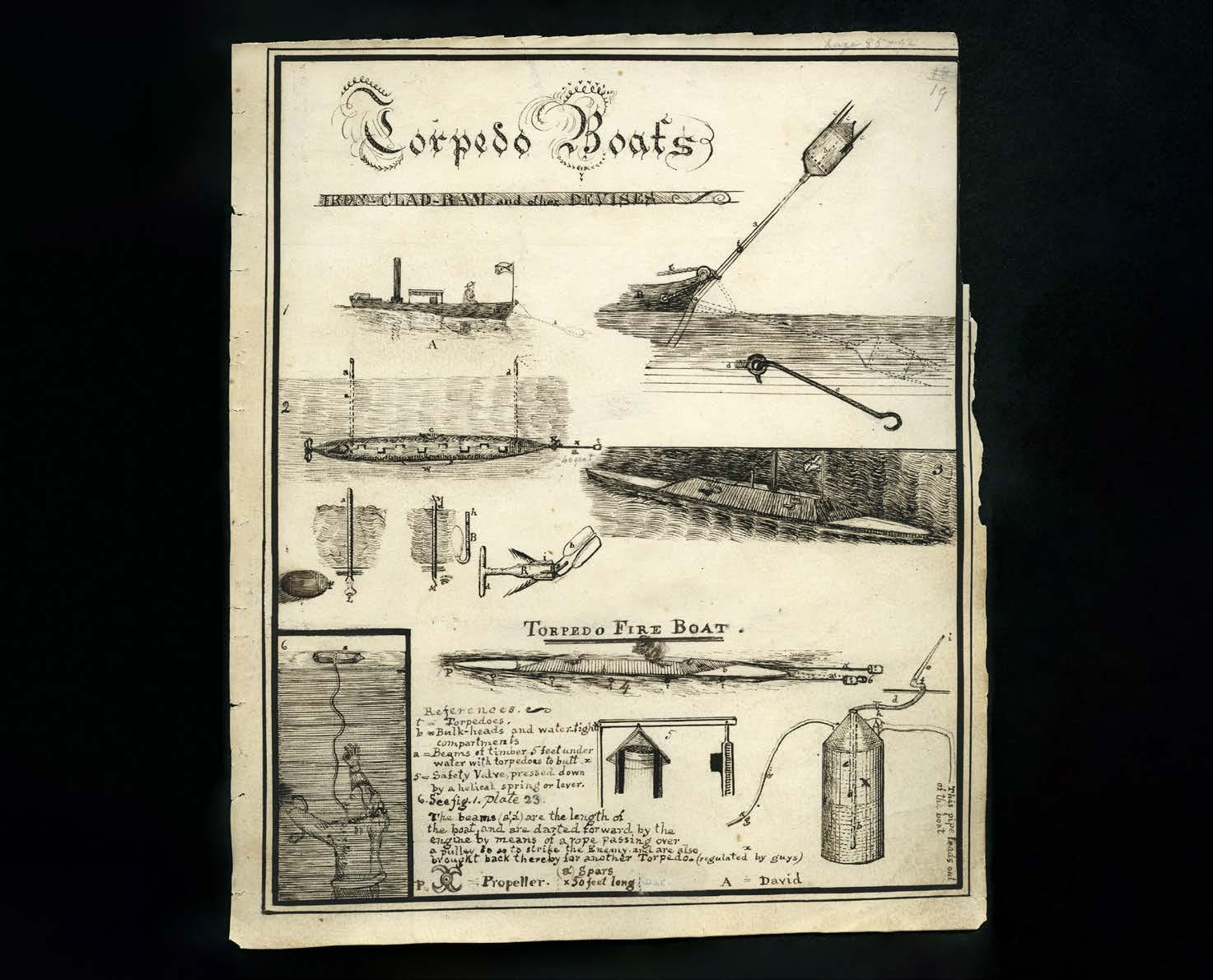

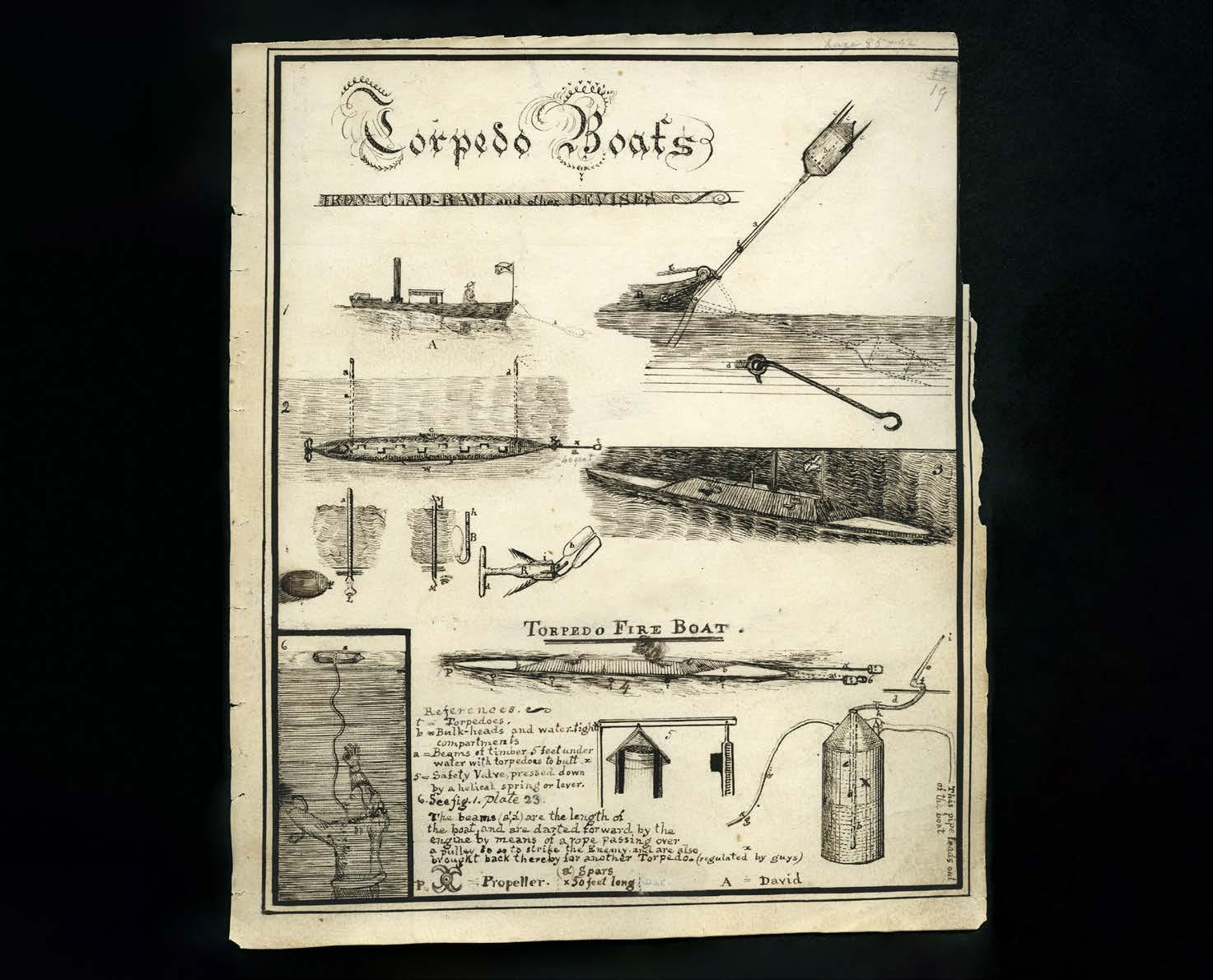

“Iron-clads are said to master the world,” wrote Brigadier General Gabriel Rains, Chief of the Confederate Army’s Torpedo Bureau, “but torpedoes master the iron-clads.” During and shortly after the war, Rains compiled a “Torpedoes” book that consisted of handwritten descriptions, instructions, and drawings.

In his book, Rains described the operation of Torpedo boats:

…at Charleston, Mobile, and Richmond, a number of small boats from 25 to 30 feet long, made of boiler iron plates with a locomotive engine which operated a propeller at the stern as the motive, were made and called ‘Torpedo-Boats (fig. A plate) or ‘Davids’. These boats carried on the end of a spar a Torpedo as arranged on a larger scale in (fig. B) with points of steel, so as to strike an enemy vessel below the water-line and stick in the spikes (C) when on backing the boat it would be left and exploded by Electricity and a protected gutta percha wire, or a corde pulling down a slab upon a sensitive primer.

Though rife with technical problems, and used in limited numbers, these torpedo boats nonetheless played a part in the evolution of naval warfare. END

Torpedo-Boats

Brig. Gen. Gabriel Rains

1860–1869

Drawing

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 6

ACWM COLLECTION

Charleston

The Heart of Secession Besieged: Charleston’s Coastal and Maritime Civil War

By Samantha Barrett

By Samantha Barrett

Civil War Outdoors Series THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 7

Asthe sharp light of a crisp winter day fades and is slowly replaced by vibrant oranges and mellow purples and blues in the sky across Charleston harbor, I imagine a similar background for the 55th Massachusetts United States Colored Troop Regiment as they arrived in Charleston on the evening of February 21st, 1865.

While they marched through the streets of this beleaguered city, singing and shouting, the troops were met by an outpouring of love and affection from Charleston’s black population as their arrival signaled a new light of freedom in this dark heart of slavery, vigorously defended for four long and bloody years. Today, walking through the colorful streets of Charleston, lined with stately buildings and well appointed gardens, it is difficult to imagine the devastation wrought on this place by the Civil War, but the 55th Massachusetts entered a city decimated by an almost constant bombardment from the Union

fleet stationed off shore, as well as the “Great Fire” of 1861 and the intentional firing of munitions and supplies by retreating Confederates a few days before.

Cheers, blessings,

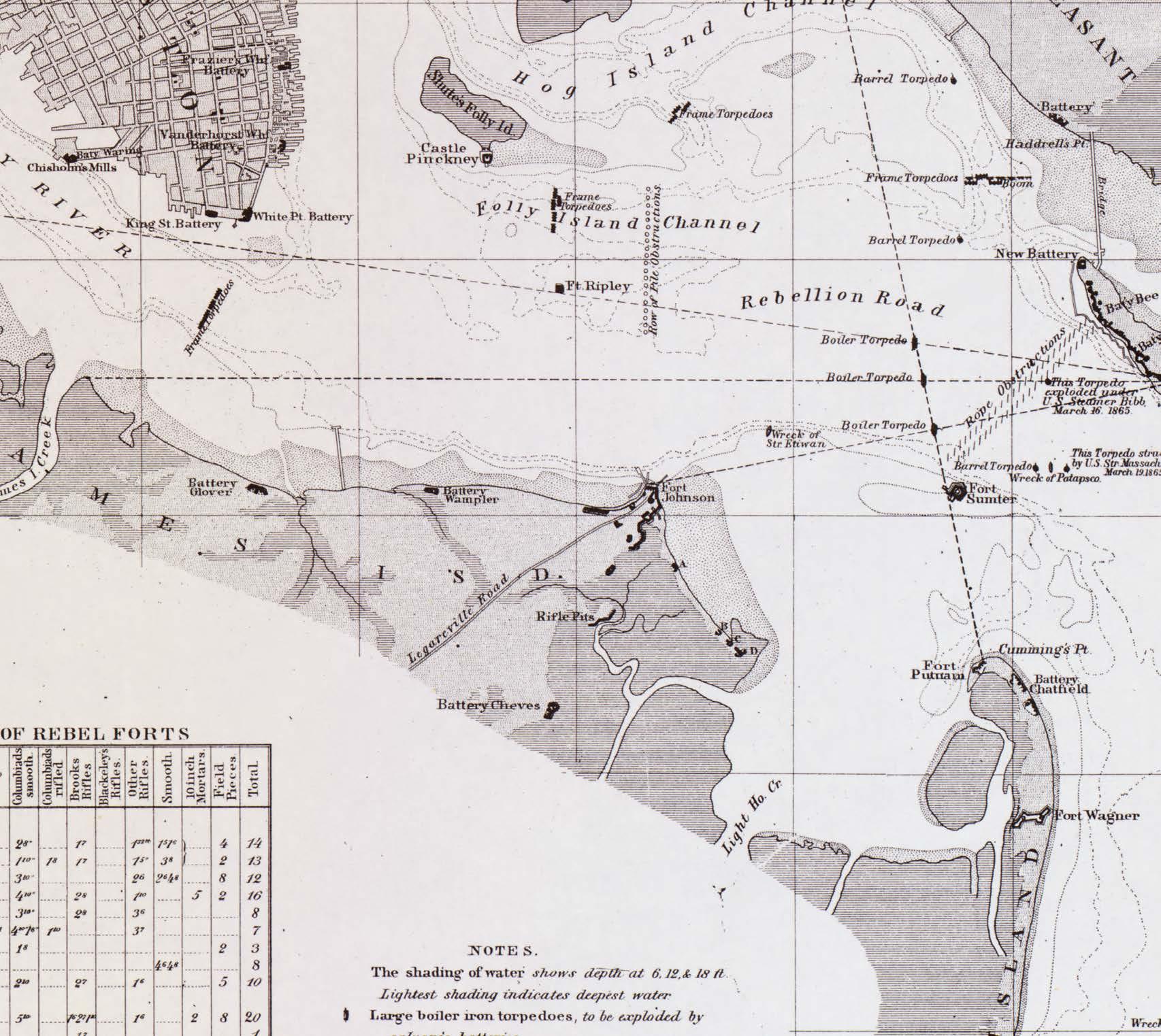

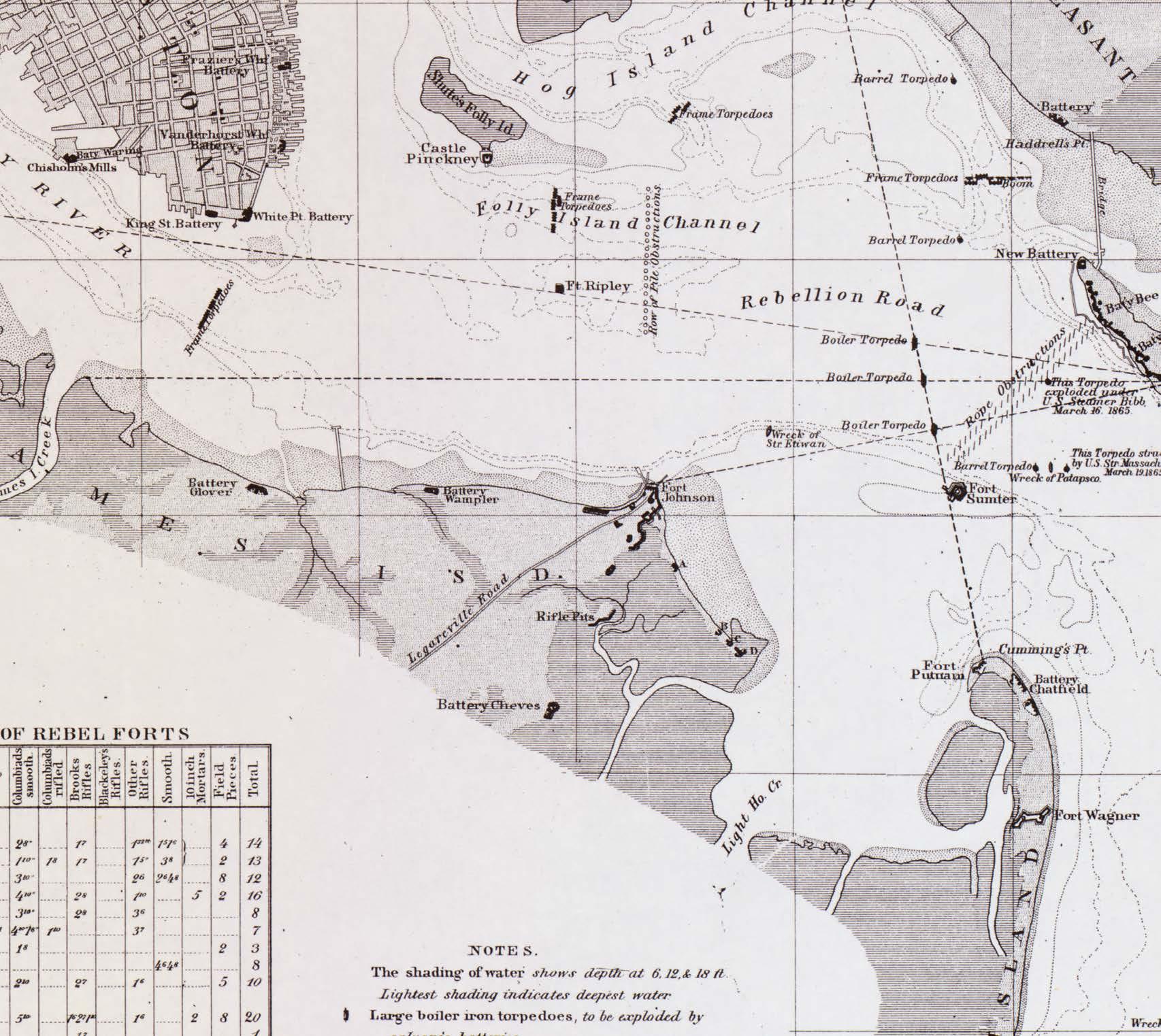

Despite all the destruction, the defenses of Charleston set up in and around the city were so strong and well placed that the Union was unable to take the city by force and only gained entrance when the Confederate defenders left. From the Revolutionary War to the Antebellum Period, a ring of defenses had evolved to protect this jewel of the south. Since Charleston was one of the most prosperous cities and ports in the country, second only to New Orleans in the south, it was essential to secure its harbor and seaward approaches.

The Antebellum defenses of Charleston included Fort Moultrie, Fort Johnson, Castle Pinckney, the Battery, and Fort Sumter. Moultrie, Pinckney, and Sumter were brick and mortar forts, while Johnson and the Battery were the site of

prayers, and songs were heard on every side.

ARTICLE COVER IMAGE: A view of modern-day Charleston through

SOURCE : Pixabay.com, CC BY-SA 4.0 IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 8

– Col. Charles B. Fox of the 55th Massachusetts 1

sail rigging.

old earth fortifications which were resurrected by the South Carolinians following secession. They also added new defenses such as adding Forts Marshall and Beauregard, and Battery Bee to Sullivan’s Island to expand the defensive capabilities of Fort Moultrie.

Following South Carolina’s secession from the Union, the state utilized local militia and state troops to take over the majority of these fortifications. However, the federal commander of troops stationed at Fort Moultrie, Major Robert Anderson, fatefully decided to leave Fort Moultrie on December 26, 1860, and remove to the island-bound Fort Sumter where he thought he would be in a more tenable position. The problem was he had a limited number of supplies and no immediate naval support. On January 9th, 1861, Charleston’s defenses got their first trial when Citadel cadets fired at the Fort Sumter resupply ship, Star of the West , from a new battery on Morris Island, just southeast of the city. Their fire was effective enough to hit the ship three times, persuading the captain to turn around and leave without

delivering the much needed supplies to Maj. Anderson. This incident was only a harbinger of the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, and the war to follow.

Beyond the defensive fortifications built around Charleston, the Confederates found other ways to protect the harbor. While they could not directly attack the Union fleet gathered just off the coast, primarily to implement the blockade, the Confederates, in the absence of a traditional naval force, used an innovative combination of naval mines (called torpedoes) and small gunboats to keep the Union ships at arm’s length. With little means to build a traditional navy, the Confederacy adopted the use of naval mines as a key component of their defensive strategy. They were a cheap and usually effective way to protect the thousands of miles of coastline and riverways across the south. Small, steam powered gunboats could easily be retrofitted from civilian crafts and used in shallow coastal

and “brown water” inland operations. These innovations, combined with the strategic placement of coastal fortifications, allowed Charleston to remain unconquered until 1865 and forced the Union military to use a “backdoor” approach through the rivers, sea islands, and marshlands surrounding the city instead of a direct assault from the sea. However, these defenses did not stop the Union from constantly shelling Charleston and its fortifications from 1863-1865 or setting up an effective blockade that kept out desperately needed supplies.

While there was a sort of stalemate between the Confederate defenses on one hand and the Union navy on the other, there were breakthroughs on both sides. Most notably Robert Smalls’ escape with Confederate gunboat Planter and the development and use of the CSS Hunley submarine.

Robert Smalls, ca 1862

IMAGE: TINTYPE

SOURCE: HAGLEY MUSEUM

Robert Smalls was an enslaved wheelman, or pilot, on the Confederate gunboat, CSS Planter, in Charleston harbor and in the coastal waterways, mainly between Charleston and Port Royal to continued on next page

MAP SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 9

the south. This meant he had an intimate knowledge of those waterways as well as any defensive features in and around them, including the naval mines. Smalls had been trying to save up enough money to buy the freedom of his wife and children for several years, but his position on Planter gave him another idea: to escape instead. In the wee hours of the morning on May 13, 1862, while the white officers spent the night on shore, he was able to slip the Planter out of Charleston harbor along with the enslaved crewmen and their families. Smalls captained the boat safely through the mine infested harbor and past all the fortifications to the Union fleet. Later, the story of his bravery and ability to execute operations under difficult circumstances helped him personally recruit thousands of black soldiers and sailors for the Union. He then returned to naval operations along the South Carolina coast and used his knowledge of Confederate defenses to help the Union carry out their “backdoor” operations around Charleston and capture strategic objectives, such as Folly and Morris Islands.

The story of the submarine, H.L. Hunley, is another example of invention born of necessity on the part of the Confederacy. Besides using defensive methods through naval mines, small gunboats, and coastal fortifications, the Confederates realized that they desperately needed a better way to break the Union blockade if they were going to survive. In New Orleans and Mobile, a small group of inventors and engineers, including Horace Hunley, Lieutenant William Alexander, James McClintock, and Baxter Watson, began developing a submarine. They built two early versions, Pioneer and American Diver, but neither was able to do any damage to the enemy. After H.L. Hunley was built and conducted a successful test mission in July 1863, witnessed by Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan, it was sent to Charleston in the hopes of giving them an edge against the Union fleet, especially the Union ironclads. While

the submarine was being developed, a semi-submersible torpedo boat, christened CSS David , was also being built in Charleston. It was used in late 1863 and into 1864 to attack ships in the Union blockade but never successfully sank anything. The Union had already built a submarine called USS Alligator, but it operated in Virginia in June of 1862 with no targets to attack and then sunk on the way to join the blockade fleet off Charleston.

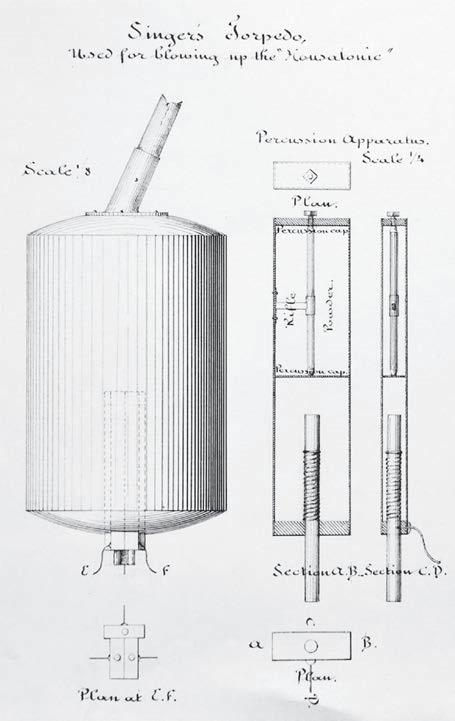

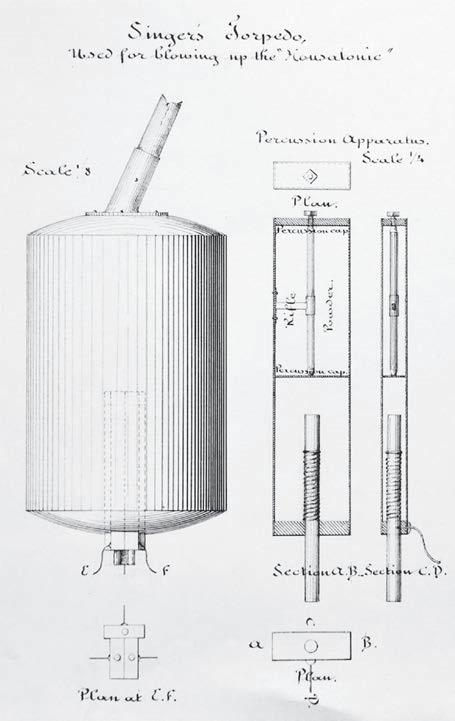

After arriving in Charleston, the submarine Hunley sank twice, killing thirteen sailors including Horace Hunley, the inventor. This did not stop the proponents of the submarine from continuing to advocate for its use, and eventually, it was sent out on a mission February 17, 1864. On this night mission, Hunley ’s target was USS Housatonic, one of the mightiest Union warships stationed outside Charleston harbor. The crew made it to Housatonic, successfully rammed their spar torpedo into the side of the massive ship, and blew a hole in its hull, sending it straight to the bottom. While Hunley never made it back to shore and sank with the entire crew still aboard, this was a revolutionary use of naval engineering and technology, and it, along with the forays of the David, sent the Union into a panic over how to best protect the blockading squadron. In a report to Secretary

continued on page 13

acwm.pastperfectonline.com

continued from previous page

Submarine Torpedo Boat H. L. Hunley Dec. 6 1863 Conrad Wise Chapman Oil paint on wood, 1864 15.5 x 11.5 IN ACWM COLLECTION

ACWM has 31 paintings by Chpaman — detailing the fortifications of Charleston, South Carolina — in its collection. See the other paintings online at

The system of torpedoes adopted by us was probably more effective than any other means of naval defense.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 10

–

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States 2

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 11

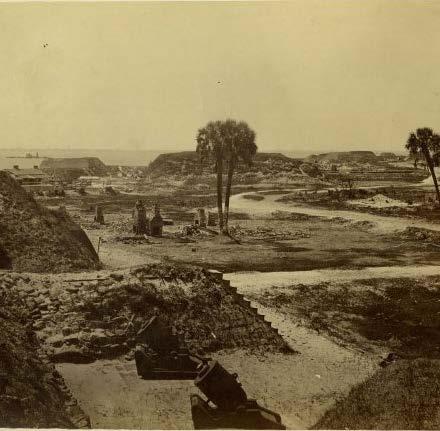

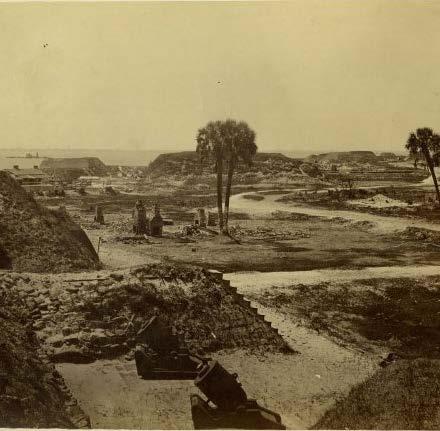

Charleston, SC

ALBUMEN PRINT, CA. 1865 ACWM COLLECTION

Ruins of the Circular Church, Charleston, SC

ALBUMEN PRINT, CA. 1865 ACWM COLLECTION

Fort Moultrie, Charleston, SC

ALBUMEN PRINT, CA. 1865 ACWM COLLECTION

Current-day scenes of Charleston, SC. (From top left to right) Downtown, a mortar and cannon at White Point Gardens, the eastern point of downtown Charleston, once a battery. (Bottom) The view from Ravenel Bridge, looking East towards the mouth of the bay with the USS Yorktown (1943-1970) in the foreground at Patriots Point.

PHOTOS: SAMANTHA BARRETT

FOOTNOTES

1 Charles Barnard Fox, Record of the Service of the Fifty-Fifth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.(Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, 1868), 57.

2 Jefferson Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government 2 vols.(New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1881) 2: 207.

3 Charles W. Stewart, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion: Series I. Volume 15. Operations: South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, Oct. 1, 1863 to Sept. 30, 1864.(Washington: Government printing office, 1902), 329.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 12

continued from page 10

of the Navy Gideon Welles on the sinking of Housatonic, Rear-Admiral John Dahlgren wrote: “The Department will readily perceive the consequences likely to result from this event; the whole line of blockade will be infested with these cheap, convenient, and formidable defenses, and we must guard every point.”3 He went on to request that “similar contrivances'' be quickly built by the Union navy yards in order to balance the naval scales he thought had tipped in the Confederate’s favor. Despite Dahlgren’s urgent request, the Union did not build submersibles to send to the fleet outside Charleston, and the Hunley remained the only submarine to sink a vessel in combat until the 20th century.

Today, visitors to Charleston can still see and visit many of the defensive locations

mentioned as well as the Hunley at The Friends of the Hunley museum. In downtown Charleston, multiple Civil War artillery pieces have been left along the famous Battery at White Point Gardens, and you can look out across the harbor and imagine a line of Union ships at the mouth. Across the water, on Sullivan’s Island, visit Fort Moultrie National Historical Park, and then walk along the beach. On your walk see if you can pick out Fort Sumter, Morris Island, Fort Johnson, and Castle Pinckney in the distance. If you want a marine experience of Charleston’s Civil War sites, I highly recommend taking the National Park tour out to Fort Sumter or catching one of the many sailing cruises around the harbor.

Lastly, one of the best ways to get a bird’s eye view of the harbor and all the sites

listed in this article is to walk across the Ravenel Bridge which spans the Cooper River. You can park at Mount Pleasant Memorial Waterfront Park underneath the bridge and walk the 2.7 mile pedestrian lane into downtown Charleston. If you want to experience the harbor from both the water and the bridge, walk the bridge then add an extra mile to catch the Charleston Water Taxi at Aquarium Wharf. It runs in a loop and will take you back to Mount Pleasant at Patriot’s Point. From there it will be another mile walk back to your car.

A diagram of the Singer Torpedo and fuse deployed by the H.L. Hunley to sink the USS Housatonic SOURCE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION

(Top) A replica of the H.L. Hunley at the Friends of the H.L. Hunley Museum in Charleston. (Below) The H.L. Hunley artifact is submeged in a fresh water tank to aid in its long-term conservation efforts at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, adjacent to the Museum.

PHOTOS: SAMANTHA BARRETT

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 13

Samantha Barrett is an ACWM Education Outreach Specialist

Loose Cannons!

Ready, Aim, Fire! A bang, a puff of smoke, and a whiff of gunpowder inaugurated the return of “Loose Cannons,” the annual fundraiser hosted by the Tredegar Society, a group of young professionals dedicated to supporting the American Civil War Museum and its mission.

From musket firing demonstrations by Museum staff, dancing to music performed by the Jared Stout Band, and General and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant (historic interpreters, Erik and Lindsay Curren of Staunton, Virginia), who posed for photographs with guests in their nineteenth century regalia, it was a very special evening at Tredegar.

The Tredegar Society raised nearly $20,000 through ticket sales and sponsorships from the American Battlefield Trust, Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, and a bevy of other corporate sponsors, with all of the net proceeds from the event going to the Museum.

Raising awareness for the American Civil War Museum with community engagement through special events and programs is a goal for the Tredegar Society throughout the year.

acwm.org/events

ACWM CEO Dr. Rob Havers (left) with Tredegar Society president Tyler Johnson, and Loose Cannons organizers Lindsay Fisher and Tayler Anderson.

Travis Voyles, VA Sec. of Natural & Historic Resources

Keven Walker, CEO of the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation (right); Cara Sisson (center), and Rob Havers.

Jared Stout Band

Erik & Lindsay Curren as Ulysses & Julia Grant pose with fans.

upcoming events visit www.acwm.org/events. IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 14

Erik & Lindsay Curren

For

Revolutions in Naval Affairs

By David C. Gompert and Hans Binnendijk

By David C. Gompert and Hans Binnendijk

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 15

At certain times, the character of naval warfare and course of naval history undergo rapid, profound, and lasting change. The American Civil War was one such time. Studying that war’s revolution in naval affairs offers lessons – even for today.

With secession quickly following Abraham Lincoln’s election, war began before either side was ready. Both sides scrambled to muster available officers, sailors, and ships. Within a year, the deficiencies of off-theshelf capabilities forced both sides to adapt. Because the Union’s naval strategy was more ambitious, and its technological and industrial capacities more prodigious, it drove the Civil War’s naval revolution.

What is a revolution in naval affairs?

A heightened threat may demand new strategy, execution of which requires new capabilities. The wider the gulf between needed and existing capabilities, the stronger the revolutionary impulse, especially when at war. New capabilities often call for technological innovation. If they prove viable, industry mobilizes to produce them on a full scale. Throughout, bold and creative leadership is indispensable. This dynamic describes the Civil War’s naval revolution, as well as those since.

[Battle of Mobile Bay]

Lithograph by Prang and Co., after J.O. Davidson. 1866.

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 16

The Union's Revolution in Naval Affairs

Again, first comes strategy. Reacting to secession, the North’s “Anaconda” plan was devised to choke the South’s economy by blocking its seaports and controlling the Mississippi River. Union warships were expected to blockade some 180 ports along some 3500 miles of coastline. On the Mississippi, 60,000 Union troops in 40 vessels and convoyed by 20 river gunboats were to steam downriver, capturing forts along the way until reaching New Orleans.

It soon was evident that the Union fleet of 1861 was grossly inadequate for this plan, in numbers and quality. A handful of blockaders had to secure the entire Southern coast, whereas blockade runners could choose opportune times and routes to make runs to Nassau and Cuba. In the war’s first year, only one out of ten runners were captured. For its strategy to succeed, the Union needed not just more ships but faster ones with more accurate guns of greater range.

Thus began the Union’s urgent transition from old warships to new ones. Pre-war “ships-of-the-line” were wooden-hulled, wind-driven, and laden with large numbers of inaccurate guns. By war’s end, warships were clad in metal, propelled by steam, and armed with far better guns mounted in movable turrets. Compared to the old ships, new ones were faster, more maneuverable, versatile, survivable, and lethal, and indifferent to currents and winds. They could operate on high seas or in narrow inland waters – both would prove essential.

Before long Union squadrons were pummeling shore batteries to reduce Southern forts and close Southern ports. More accurate guns fired faster and caused surer destruction of targets. As the efficacy of new capabilities became plain, the Union scaled up production at an unprecedented clip, thanks to the Industrial Revolution sweeping the North.

Facing Confederate forts impeding Union passage along the Mississippi and guarding Southern ports, the Union Navy had an answer: new bombardment tactics whereby gunship squadrons maneuvered continuously in oval patterns, making them less vulnerable and optimizing firing angles. Also, being ironclad, they could sail close to their targets to get off better shots. When Confederate forts were too hard to attack frontally from the water, Union gunships would “run the gauntlet,” often through plunging fire, to gain advantageous positions from which to attack. Admiral David Farragut famously brought his fleet upstream at night past the chains, forts, and batteries protecting New Orleans. Once the fleet was in position, the forts guarding New Orleans fell to joint naval-ground assaults.

Meanwhile, riverine warfare was enabled by the speed and maneuverability that only steam-propelled ships could provide, and iron-cladding obviously helped. Union gunboats gained control of the Mississippi, culminating with the fall of Vicksburg, to allow Northern passage and restrict Southern replenishment across the river. Along the way, these vessels escorted convoys, transported troops, and attacked Southern guerillas along the shores.

An illustrated map showing Gen. Winfield Scott's plan to strangle the Confederacy economically, focused on blockading seaports. It is also called the "Anaconda plan.

ILLUSTRATION: 35 X 44 CM, 1861

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Civil War gunnery progressed as rapidly as propulsion and armor. Rifling dramatically improved accuracy by spinning and stabilizing projectiles. Rotating turrets provided nearomnidirectional fire, augmenting the tight turning of steamdriven warships. These innovations, thanks to Northern inventiveness, swung the long-held advantage from fortified shore batteries into naval bombardment.

continued on page 19

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 17

IMAGE: WET COLLODION ON GLASS, CA. 1865

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

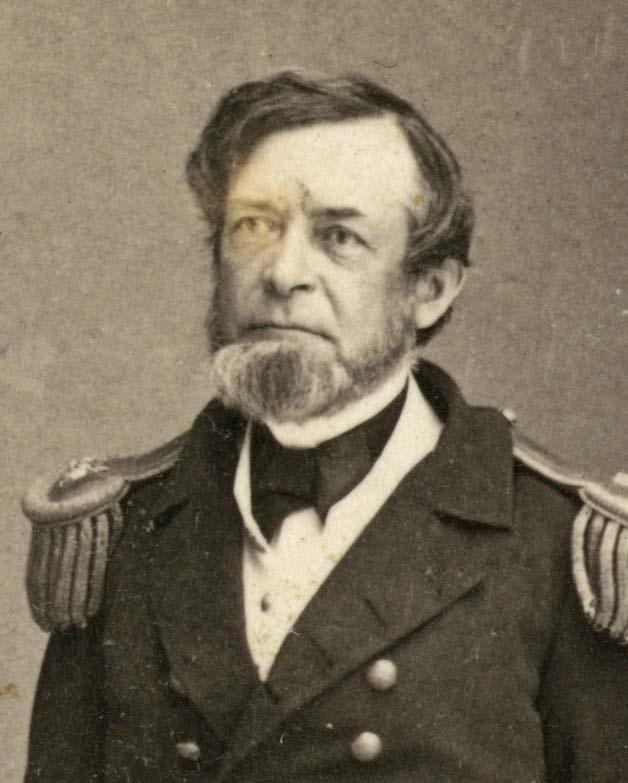

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 18

Emerging Technology and Industrial Mobilization

There really is such a thing as “Yankee ingenuity.” Finding technical fixes to practical problems came naturally in harsh, chilly, rocky New England, which was the epicenter of the American Industrial Revolution. Technology progressed rapidly in the North before and during the Civil War. Patents issued annually grew from about 900 in 1850 to 5000 in 1860 to 13,000 in 1870.

Union needs called for advances in metallurgy. Over millennia, innovations in mining, extracting metal from ore, smelting, shaping, and use of coal and coke furnished the Industrial Revolution with the iron and steel with which to make machines and infrastructure. Henry Bessemer invented a high-volume steelmaking process five years before the American Civil War. Even then, because iron was cheaper and easier to make than steel, the latter was reserved primarily for making small arms.

Innovation also improved gunnery before and during the Civil War. Rifled gun barrels with spiral grooves were invented much earlier but first manufactured on a large scale in the 1850s. Also, advanced gun sights, percussion locks, and methods to gauge ballistic trajectories added to force and accuracy.

The North’s Industrial Revolution powered huge increases in productivity and production. Nearly 90% of all U.S. industrial production resided in the North. The Union had 11 times as many ships and 32 times as many weapons manufacturers as the Confederacy. The North’s industrial capacity was based on its growing indigenous population; swelling immigration; agricultural productivity; a doubling of investment in manufacturing in the 1850s; and financial wherewithal based on a sturdy banking system and Californian gold.

While the total number of Northern factories did not increase appreciably – it already had 110,000 factories in 1861 – iron and steel production did. When war broke out, the North was producing 20 times more iron than the South. That and the increased capacity to produce steam engines led to the Union’s preponderance of gunboats. When war began, the Union had 42 warships, including sailing vessels of doubtful utility. By the end, the Union navy had 626, ships, including 84 ironclads, carrying 4,610 guns, making it the world’s largest.

Union Leadership

Union naval officers typically got the most out of their new ships and crews and left a lasting imprint on how war is waged on water. In general, these leaders were quick learners and daring innovators, captives of neither tradition nor bureaucracy. Farragut, Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, and Andrew Foote stood out in all these respects; not far behind were Admial David Porter and Samuel Du Pont . Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Assistant Secretary Gustavus Fox get high marks for vision, political savvy, and ability to ensure commanders got the fleet they needed.

Farragut took naval warfare to a scale and degree of difficulty not previously attempted. He forced the surrender of New Orleans by running a squadron past the forts downstream of the city and proceeding upstream to the city. Later, Farragut succeeded as stunningly in bringing Mobile Bay under Union control, despite a formidable array of Confederate torpedoes (mines), which he is said to have loudly “damned” as he sped through them.

While Farragut was opening the lower Mississippi, Andrew Foote, Commander of the Union’s Western Gunboat flotilla, teamed with then-Brigadier General Ulysses Grant to open Tennessee by river to Union control. Foote did this by orchestrating, with Grant, an unprecedented level of army-navy “joint” collaboration – a major and long-lasting contribution to the revolution in naval affairs and ultimately the essential American way of war. Grant himself described how Foote was in “perfect agreement” on how to take Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and nearby Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. With neither officer having authority over the other, they formed a trustful partnership that has been a vital quality of jointness ever since. Foote also showed that a force of steam-propelled armored gunboats could fight and win battles on and from inland waters that wooden sailing ships could not.

The Navy Department’s leading ordnance expert, Commander John Dahlgren, invented the eponymous gun, which excelled during the war. Though muzzle-loaded and smooth-bored, its bulbous breech yielded immense explosive force and, thus, greater distance, accuracy, destruction, and safety than heavy guns to that point. Promoted to rear admiral,

continued on page 22

continued from page 17

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 19

IMAGE: WET COLLODION ON GLASS STEROGRAPH (LEFT SIDE), CA. 1865

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren on the deck of the USS Pawnee standing next to a cannon designed by himself – the Dahlgren gun.

Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren on the deck of the USS Pawnee standing next to a cannon designed by himself – the Dahlgren gun.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 20

IMAGE: WET COLLODION ON GLASS, CA. 1865

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Gideon Wells

U.S. Secretary of the Navy

IMAGE: WET COLLODION ON GLASS, CA. 1865

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

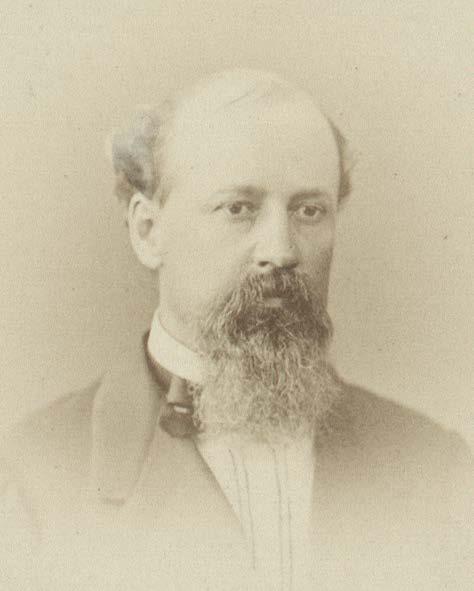

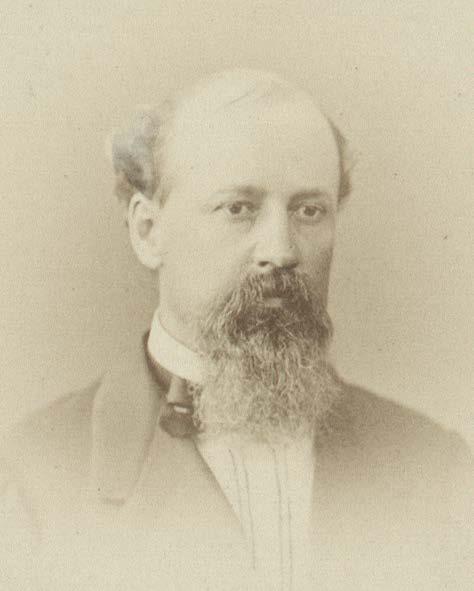

Gustavus Fox

Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Navy

IMAGE: ALBUMEN PRINT, CA. 1866

IMAGE: ALBUMEN PRINT, CA. 1861

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

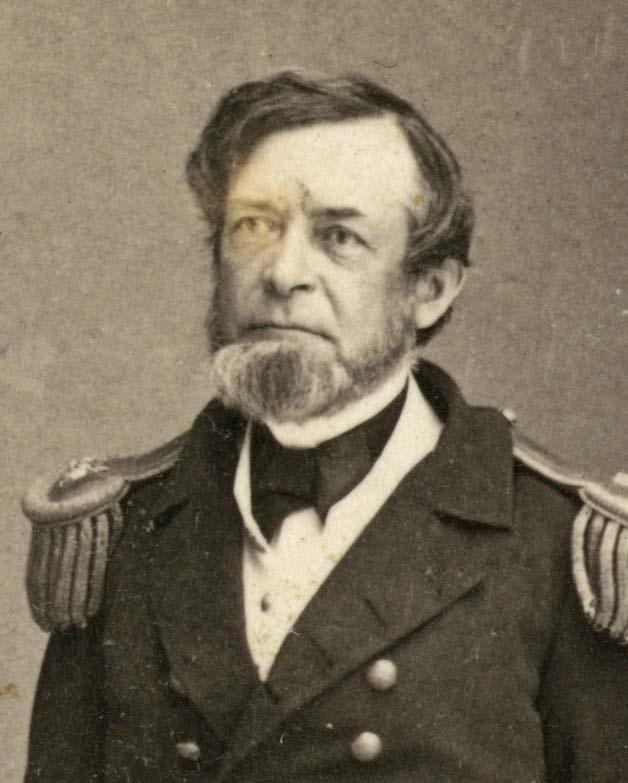

Stephen R. Mallory Confederate Secretary of the Navy

Andrew Foote Commander of the U.S. Western Gunboat flotilla

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 21

Dahlgren was assigned to neutralize Charleston, the war’s cradle, which was protected by several previously invincible forts. He sent monitors within just 300 yards of Confederate batteries. After two months of naval bombardment, Dahlgren forced abandonment of Charleston’s forts, effectively ending Charleston's use by blockade-runners.

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, assisted by Gustavus Fox, transformed the Union navy into a large, modern, and effective fighting force. They mounted the unprecedented industrial mobilization that overpowered Confederate capabilities. Welles rewarded excellence and creativity in his officers, promoting Farragut, Dahlgren, Foote, and Du Pont all to the new rank of rear admiral based on their success and ability to lead in the face of uncertainty and change.

Confederate Innovation

Renowned naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan opined that the Confederacy was doomed for want of a navy. He held that any country with a long coastline and dependence on sea trade ought to have a capable navy, lest it fall victim to an adversary with one. Mahan believed the Union’s Anaconda strategy would have failed had the Confederacy possessed a navy to defend its shores and sea access. Indeed, the South’s long coastline and many harbors and inlets would have favored a Confederate navy; lacking one, it favored the Union’s.

Whether Confederate leaders made a definite decision to deprive the navy in favor of funding their armies, this was the effect of their policies. The Confederacy spent but 10% of its wartime budget on naval capabilities, even as the lack of such capabilities was causing severe economic and strategic losses. While the Confederacy had to make do with an anemic fleet, it at least had a resourceful and innovative naval leader. Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory, knowing the South could not match the Union Navy, championed improvisation.

Under Mallory, the South managed to acquire some 20 ironclads to defend its ports and rivers. The war’s first was the CSS Manassas, then joined by the Louisiana, the Mississippi, the Atlanta, the Arkansas and others. But it was the converted USS Merrimack—the CSS Virginia—that made history by fighting the war’s, and history’s, first ironclad battle with the USS Monitor in 1862. (Most Confederate ironclads were eventually captured or scuttled.)

The height of Confederate ingenuity was a submarine, the CSS Hunley, which was the first ever to sink an enemy ship, the USS Housatonic, in Charleston’s harbor. The 40-foot vessel was made of iron, had a crew of eight, a hand-crank propeller, ballast tanks, hand pumps, and a torpedo at the end of a 22-foot spar triggered to detonate at contact. The Hunley’s top speed was 4 knots. In its attack on the Housatonic, the Hunley’s own crew were killed probably from the concussion of the explosion.

Although Southern innovations did not not approach the level of a revolution in naval affairs, they were still significant and were adopted by the U.S. Navy. In this limited respect, the Confederacy contributed to the naval revolution that eventually made the United States the global sea power advocated by Mahan.

Subsequent Revolutions in Naval Affairs

The Civil War naval revolution was of monumental importance not only because it helped the Union win but also because it changed the course of naval history. Even as the U.S. Navy was largely mothballed after the Civil War, study of its transformation spread. As Britain, France, Russia, Japan, and newly formed Germany and Italy intensified competition for colonies, battle fleets were their main instruments of power. These nations began to build large, turreted, ocean-going ironclads. Soon, Great Britain was building very large armored warships. British and German battleships, dreadnaughts, and battle cruisers built and sent into World War I were direct descendants of Union ships. Because their enhancements, e.g., steam turbines, were incremental, it is fair to say that the revolution of the American Civil War defined navies globally through World War I.

David Gompert is on the faculty of the U.S. Naval Academy and former Acting Director of National Intelligence. Hans Binnendijk is a Distinguished Fellow at the Atlantic Council and former Director of the Institute for National Security Studies at the National Defense University. Both authors are on the Board of Directors of the American Civil War Museum.

continued from page 19 IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 22

Knickknackery Scrimshaw

Fragment of scrimshawed bone of the ironclad CSS Virginia.

According to the donor, this shell, with a carved image of CSS Georgia, was made by a twelve-year-old girl while the ship was docked in Cherbourg, France, and was given to Lt. William Evans.

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 23

A great, patched-upunwieldy scarecrow

Lieutenant Hunter Davidson’s Forgotten Account of the CSS Virginia at Hampton Roads

The article on the M-M [Monitor-Merrimac] battle I wrote because I was really worried into it by reading so many contradictory & prejudicial reports on the subject and wanted to see our Naval History on the square.

Commander Hunter Davidson

IMAGE: ALBUMEN PRINT, CA 1865

SOURCE: NAVAL HISTORY AND HERITAGE COMMAND

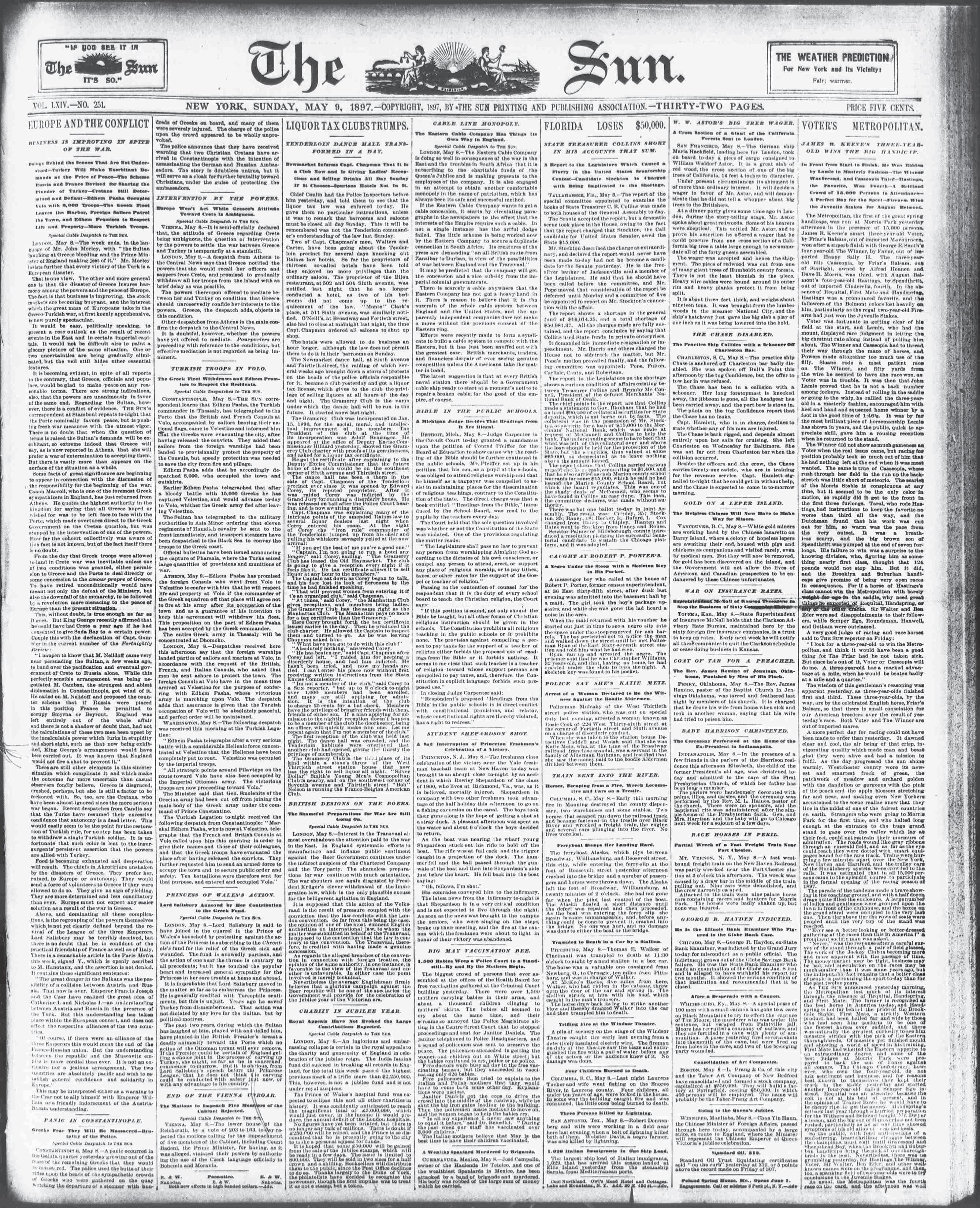

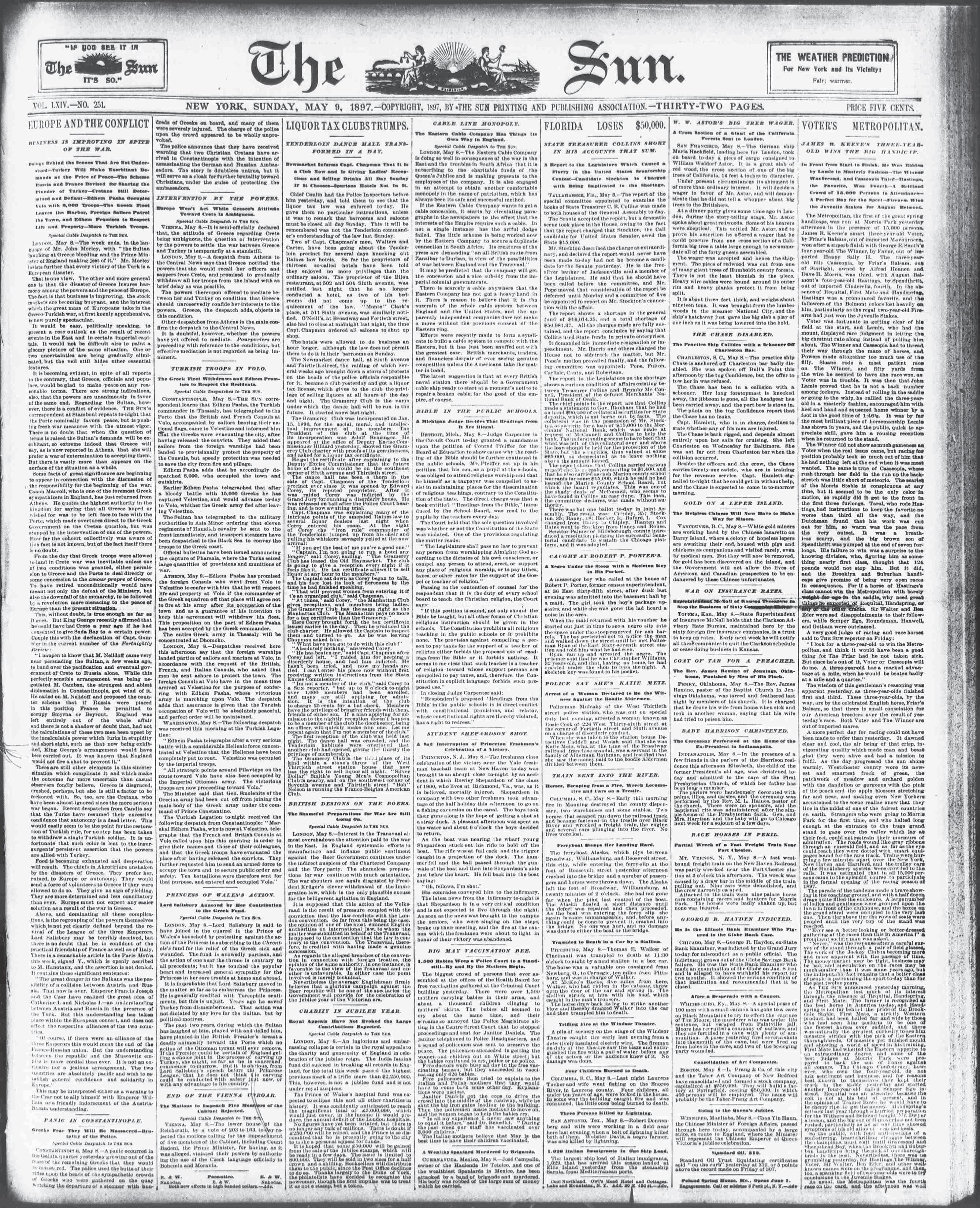

Front page of the The Sun from May 9, 1897 in which Davidson's account was published.

SOURCE: NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY

– Hunter Davidson to Adm. Stephen B. Luce, 19 April 1897

– Hunter Davidson to Adm. Stephen B. Luce, 19 April 1897

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 24

By Dr. John M. Coski

“ In the battle between the Monitor and the Merrimac , I had charge of the Merrimac’s forward or first division of guns, and as she did much of her work ‘bows on,’ I was in a very favorable position to see what occurred.”

So began an important and virtually unknown eyewitness account of the most famous naval battle of the American Civil War.

Published in the May 9, 1897 New York Sun and running more than 4,000 words, its author was Lt. Hunter Davidson, C.S.N. Descended from several old Virginia families, Davidson (1826-1913) was the son of a U.S. Army officer. Hunter entered the U.S. Navy at age 15 in 1841, served in the Mexican War, graduated from the new Naval School at Annapolis in 1849, distinguished himself in the U.S. Coastal Survey in the 1850s, taught at the U.S. Naval Academy, and received two U.S. patents

for a boat-lifting device just before the outbreak of civil war. In April 1861, he resigned his commission as lieutenant in the U.S.N., and offered his services to his ancestral state.

During the Civil War, he earned his footnote in naval history as commander of the Confederacy’s Submarine Battery Service and for pioneering the use of electrically-detonated “torpedoes” (mines) against enemy warships. He won promotion to commander in 1864 for a daring torpedo boat attack against the friagte USS Minnesota. In late 1861, Davidson received one of the most coveted assignments in the Confederate navy: officer on the Confederacy’s first and most celebrated ironclad warship, the CSS Virginia

journal is unknown and his Sun article (one of several he contributed to that newspaper) was not widely reprinted and fell into obscurity. Much of what Davidson wrote follows the standard narrative of Virginia's brief career, but he included details about working the guns and conversations (no doubt embellished) with the ship’s commander that add color and texture to the narrative.

bat tle I cannot call it

The CSS Virginia was built on the burned out hull of the U.S. steam frigate, Merrimack , a name that Davidson and many officers and crew continued to use (usually misspelled) for the Confederate ironclad. In his 1897 assessment, Davidson emphasized her vulnerability and lack of maneuverability. Although she had a “powerful battery,” only two guns proved “serviceable” in the battle. She was “mainly covered with scrap iron, nowhere more than four inches

Although his article was published 32 years after the epochal battle, Davidson insisted that “the facts…are fresh in memory, and my account entered just afterward in the private journal I kept, is still with me.” The fate of the private continued on next page

An iron test plate rolled for the CSS Virginia at Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Va., 1862 8 x 13.5 x 1 inches

SOURCE: ACWM COLLECTION

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 25

continued from previous page

thick,” Davidson wrote. “The shield was inclined at an angle of about 36 degrees, forming a covering for the fighting deck, and the men at the guns had to work stooping.” Her greatest vulnerability was at the “knuckle,” where the sloped shield joined the perpendicular sides. This was, Davidson wrote, “considered so tender that it was necessary to hide and protect it by increasing the draft to 22 1/2 feet, and so bring it about six inches below the water line. The gunports were only four inches perpendicularly above the water line.”

“The Merrimac,” Davidson concluded, “was a great, unwieldy patched-up scarecrow, without buoyancy or ability to maneuver, but she was the best the means of the South enabled it to do.”

Keenly aware that the U.S. navy was also building an experimental ironclad floating battery, Confederate naval authorities rushed to complete Virginia. To command her the Navy Department appointed Capt. Franklin Buchanan, a Marylander who had been the first superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy. His executive officer was Lt. Catesby Ap Roger Jones, of Virginia, who had been an officer aboard the new steam frigate USS Merrimack on her maiden voyage in 1856 and had supervised her conversion into CSS Virginia

– Hunter Davidson

– Hunter Davidson

“On the morning of March 8, 1862, the day previous to the arrival of the Monitor in Hampton Roads the Merrimac, sallied forth from Norfolk against the Federal forces assembled there,” Davidson recalled. “’All hands’ had been up through the previous night, preparing the vessel to move, but without time for exercise at the guns, as everything had been rushed on board, working day and night for weeks previous in the desire to get the vessel out. In fact, most of the fighting crew were green hands, put on board at the last moment.”

In broad, but vivid, strokes Davidson described the action of March 8th, when Virginia took on the wooden warships blockading Hampton Roads. She inflicted the worst losses the U.S. navy ever suffered until December 7, 1941.

IMAGE: ALBUMEN PRINT

SOURCE: ACWM COLLECTION

IMAGE: ALBUMEN PRINT

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

“Night came on after the day’s work – battle I cannot call it, for an iron steamer, under way, fighting wooden sailing vessels at anchor, does not give them battle,” Davidson wrote grimly. “The officers and crew of the Merrimac were exhausted with twenty-four hours’ continuous labor, much of it in stooping positions under the inclined shield.” The vessel was also worse for wear.

Capt. Franklin Buchanan, ca 1862

Lt. Catsby Jones, ca 1862

The Merrimac was a great, unwieldy patched-up scarecrow, without buoyancy or ability to maneuver, but she was the best the means of the South enabled it to do.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 26

Most notably, the iron ram – Davidson called it a “beak” – had been twisted off while ramming the USS Cumberland, exacerbating the ship’s leaking condition.

Captain Buchanan had been wounded by small arms fire, and command passed to Catesby Jones. He had hoped to anchor near the scene of action so as to resume the destructive work at first light, but the pilots warned him that rough waters could cause the leaking vessel to roll or sink – transforming an historic triumph into an embarrassing disaster. Virginia returned to her base for the night.

I was the first to observe the Monitor

Davidson had the morning watch on March 9, and his account surrendered to the drama of the occasion: “I was the first to observe the Monitor anchored off near Newport News. It loomed up to an enormous size, under the influence of a partial mirage, so often seen in the Chesapeake and the adjoining waters. At first I could not imagine what it was, so totally different was the general outline from anything I had ever seen or heard of. In a few moments, however, I recalled the information we had not long before received from New York in reference to the Monitor. I immediately sent below to let Jones know that it had arrived and was anchored in sight. Jones came out on deck, in a moment, and his face showed

that he understood the situation. He was a very quiet, reserved man, and so I asked him. ‘What are you going to do?’ ‘Fight her, of course,’ was the prompt reply.”

Davidson preferred “to continue the work of destruction among the wooden vessels” and let Monitor try to stop it. Jones feared that Monitor could exploit Virginia’s weaknesses, especially her vulnerable knuckle, which was even more exposed after the expenditure of so much coal and ammunition the day before raised it above the water line.

Davidson’s narrative of the first duel of ironclads conceded that Monitor was not without her own “difficulties and defects,” but he always returned to Virginia’s defects and Monitor ’s advantages. “The Monitor could stand ordinary rough weather, had eight inches of well-formed iron on a [rotating] turret, carried two 11-inch guns side by side and pointing in the same direction, drew only 14 feet of water, and maneuvered with ease,” Davidson wrote. Virginia’s chief advantage was “the presence of a far greater number of regular naval officers on board.”

“As soon as possible we were under way, and the contest began at close range,” Davidson continued. He did not describe the nearly three hours of combat in the familiar terms of the two ironclads firing at each other at point-blank range without discernible effect. He emphasized

instead that the “only serviceable weapons” Virginia had in the fight were a pair of 7-inch Brooke rifles mounted on pivot carriages, one mounted on the bow and the other aft. Because the ship’s exposed steering apparatus was mounted aft, “we did not expose that end.” Perhaps not coincidentally, Davidson himself commanded and personally worked the 7-inch bow rifle.

Jones and his officers searched for any literal or metaphorical chink in Monitor ’s armor. Davidson noted that there seemed to be “something wrong” with Monitor ’s port shutters because they remained open when the ship was not firing. In fact, Monitor ’s executive officer, Lt. Samuel Dana Greene, decided to leave them open because closing the heavy pendulum covers consumed too much time and manpower. Davidson determined to exploit the weakness and “made the men of my division fire into them as rapidly as possible with small arms while the chance offered.” That, too, had no effect.

Davidson offered a uniquely personal account of how Virginia’s officers finally found a way to cripple their nemesis. “Jones sat in a small hatchway at the after part of my division, and we were in communication every few minutes during the action,” Davidson wrote in his account. Davidson wondered aloud what Monitor was trying to do. He replied,

continued on next page

CS Steamer Virginia

HARDIN LITTLEPAGE (CSS MIDSHIPMAN), 1862

IMAGE: PENCIL AND INK ON PAPER

SOURCE: ACWM COLLECTION

Hardin Beverly Littlepage, n.d.

IMAGE: ALBUMEN PRINT

SOURCE: ACWM COLLECTION

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 27

continued from previous page

with emphasis, that the same question had repeatedly occurred to him. ‘Can’t you try and hit the pilot tower? ’he asked. At the same time he ordered Lieutenant C. C. Simms, the executive officer, to go aft and direct the other division to do the same.”

Virginia’s guns aimed for the pilot house, and Monitor ’s movements suddenly “appeared wild,” and she steered off toward Hampton into shoal waters where Virginia could not reach her. Virginia’s officers learned later that a shot striking the pilot house blinded Monitor ’s commander, Lt. John L. Worden. That shot effectively ended the duel between the two ironclads.

Monitor ’s withdrawal allowed Virginia to resume her attack on the grounded wooden frigate, Minnesota. In an effort to draw closer to her prey, Virginia, too, ran aground. The only gun that could reach Minnesota was the 7-inch bow rifle which, Davidson boasted, he pointed and fired with his own hands, sinking an armed tug that lay alongside Minnesota and inflicting damage on the frigate.

Thanks to the efforts of Virginia’s capable engineers, she soon freed herself from the shoal, and could assume a more

CSS Virginia Engaged with USS Cumberland UNKNOWN ARTIST, 1862

IMAGE: OIL ON TICKING, 17 X 12 IN.

SOURCE: ACWM COLLECTION

favorable position toward Minnesota. The ship, that was to be the focus of Virginia’s attention on March 9, appeared now at her mercy. In his Sun article, Davidson quoted Minnesota’s captain, Gerson Van Brunt, as testimony to how close his ship was to destruction: “Seeing that the Monitor had retired from the action and could no longer render me any assistance, that my decks were covered with dead and dying, and my vessel unable to resist the enemy, I had gone on deck to make arrangements to abandon the vessel, when, to my surprise, I saw the rebel monster steaming toward Norfolk.’” Indeed, at noon, Catesby Jones ordered his ship to break off the battle and steam back to Norfolk.

As Virginia turned back toward the Elizabeth River, Lt. John Taylor Wood, Davidson’s former Naval Academy faculty colleague who commanded the ship’s aft 7-inch pivot rifle, came to Davidson and said, “’Dave, let’s gives [sic] the Monitor a parting shot.’ ‘All right,’ I answered, and our divisions each fired two shots low, so as to richochet [sic], for the Monitor was a long way off; and we thought one at least struck her, but

The old patchwork had nearly run her race. The grounding had spread her butt ends, as well as twisted her knuckle, and she was leaking rapidly.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 28

– Hunter Davidson

IMAGE: WET COLLODION STEREOGRAPH (LEFT).

SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

the distance was too great to be certain. To those last shots the Monitor did not reply, and thus ended the day’s contest.”

patchwork had nearly run her race. The grounding had spread her butt ends, as well as twisted her knuckle, and she was leaking rapidly.”

SOURCE:

Davidson contended in 1897, as he had in 1862, that Virginia won the first duel of the ironclads, that Monitor “was as much defeated as an army that abandons the field of battle and leaves it in possession of the enemy.” Even though Virginia also left the field and failed in her objective to sink Minnesota and the other wooden warships, that failure did not owe to her ironclad foe. Appealing to the court of historical judgment, Davidson asked rhetorically “where was the Monitor ” while Virginia was “lying aground for nearly an hour, immovable, and deliberately trying to destroy the Minnesota.” “Nowhere did she come, not a shot did he fire, and this I state as if standing in the ’witness box.’” Virginia left, Davidson wrote, not because of Monitor, but because “the old

When Hunter Davidson wrote his account of the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1897, it was not only temporal distance, but spatial distance, that separated him from the event. Davidson lived the last 38 years of his life in South America. Since the end of the Civil War he had been searching for lucrative employment abroad and finally found it in Argentina, where he was in command of the torpedo and hydrographic department. An “unreconstructed” Confederate, Davidson retired to Paraguay, where he married a woman 46 years his junior (Enriqueta Silvia Davalos. 1872-1953) and began a second family. Despite his self-exile, he remained determined to assert and defend his place in the history of the American Civil War.

Officers of the USS Monitor pose in front of its turret on July 9, 1862. Lt. Samuel Dana Greene, the executive officer, is seated on the far right.

Hunter Davidson died in 1913 at the age of 86 in Paraguay and is buried in Paraguarí, Paraguay.

CONFEDERATEVETS.COM

Officers of the USS Monitor pose in front of its turret on July 9, 1862. Lt. Samuel Dana Greene, the executive officer, is seated on the far right.

Hunter Davidson died in 1913 at the age of 86 in Paraguay and is buried in Paraguarí, Paraguay.

CONFEDERATEVETS.COM

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 29

Dr. John M. Coski served as the museum’s historian and director of the Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library for more than 30 years. He is currently finishing a full-length biography on Hunter Davidson.

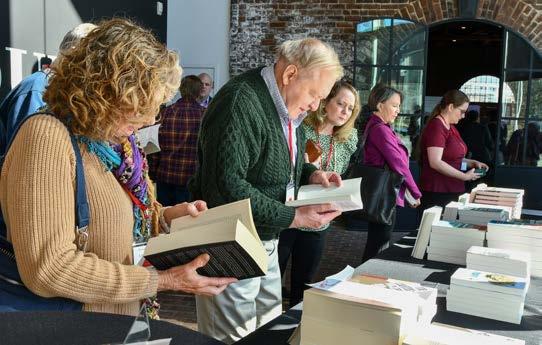

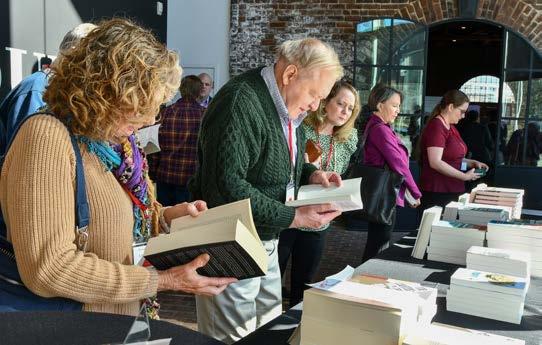

Symposium Highlights 2023

Building upon the success of last year’s symposium, the museum held the 2023 Symposium on site. In all, 104 people attend in-person with another 57 viewing through livestream. The 2023 Symposium covered topics from “abolition to Reconstruction,” marking the beginning of a multiyear programmatic initiative, The Civil War and Remaking America, which will cover the causes, course and consequences of the war. Join us this spring and fall as we explore the causes of the war. Next year’s symposium will focus on secession and the first shots of the war.

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 30

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 31

Capital Navy

By John M. Coski

Capital Navy is the first book to examine the importance of Confederate naval operations on the James River, and their significant (and yet largely ignored) impact on the war in Virginia.

Paperback: 366 pages

Publisher: Savas Beatie, July 2005

Member: $17.06; Retail: $18.95

SKU: 1556

Duel Between the First Ironclads

By William C. Davis

Using letters, diaries, and memoirs of men who lived through the epic battle of the Monitor and the Merrimack and of those who witnessed it from afar, William C. Davis documents and analyzes this famous confrontation of the first two modern warships. The result is a full-scale history that is as exciting as a novel.

Paperback: 220 pages

Publisher: LSU Press, April 1981

Member: $17.96; Retail: $19.95

SKU: 40200

Our Little Monitor

By Anna Gibson Holloway & Jonathan W. White

Holloway and White bring “Our Little Monitor” to life in this beautifully illustrated volume. In addition to telling her story from conception in 1861 to sinking in 1862, they explain how fighting in this new “machine” changed the experience of her crew and reveal how the Monitor became “the pet of the people”.

Hardcover: 304 pages

Publisher: The Kent State University Press, Feb. 2018

Member: $31.46; Retail: $34.95

SKU: 153532

Unlike Anything That Ever Floated

By Dwight Sturtevant Hughes

From flaming, bloody decks of sinking ships, to the dim confines of the first rotating armored turret, to the smoky depths of a Rebel gundeck to the office of a worried president with his cabinet peering down the Potomac for a Rebel monster, this dramatic story unfolds through the accounts of men who lived it.

Paperback: 192 pages

Publisher: Savas Beatie, March 2021

Member: $13.46; Retail: $14.95

SKU: 154197

To the Uttermost Ends of the Earth

By Phil Keith & Tom Clavin

Authors Phil Keith and Tom Clavin introduce some of the crucial but historically overlooked players, including John Winslow, captain of the USS Kearsarge and Raphael Semmes, captain of the CSS Alabama Readers will sail aboard the Kearsarge as Winslow embarks for Europe with orders to destroy the Alabama.

Hardcover: 320 pages

Publisher: Hanover Square Press, April 2022

Member: $27.00; Retail: $29.99

SKU: 155077

In the Waves

By Rachel Lance

In the Waves is much more than just a military perspective or a technical account. It’s Rachel Lance’s quest to find all the puzzle pieces of the Hunley. Balancing a gripping historical tale and original research, In the Waves is an enthralling look at a unique part of the Civil War and the lengths one scientist will go to uncover its secrets.

Paperback: 368 pages

Publisher: Dutton, April 2021

Member: $16.20; Retail: $18.00

SKU: 155096

Shop online @ ACWM. ORG Featured Books

IRONCLAD : Spring 2023 32

A History of Ironclads

By John V. Quarstein

By John V. Quarstein

The construction and combat service of ironclads during the Civil War were the first in a cascade of events that influenced the outcome of the war and prompted the development of improved ironclads as well as the creation of new weapons systems, such as torpedoes and submarines, needed to counter modern armored warships.

Paperback: 288 pages

Publisher: The History Press, February 2007

Member: $22.74; Retail: $24.99

SKU: 441

The Battle of the Ironclads

By John V. Quarstein

This thrilling history is the first volume to offer a comprehensive pictorial interpretation of the men and ships that forever changed naval warfare. Over 150 images (photographs, engravings, paintings, and sketches) have been gathered to chronicle the exciting story of the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia

Paperback: 128 pages

Publisher: Arcadia Publishing, July 1999

Member: $19.80; Retail: $21.99

SKU: 155073

The CSS Virginia

By John V. Quarstein

Virtually everything about the Virginia's design was an improvisation, characteristic of the Confederacy's efforts to wage a modern war with limited industrial resources. A noted historian, Quarstein recounts the compelling story of this underdog, with detailed appendices, crew member biographies, and a complete chronology of the ship and crew.

Paperback: 592 pages

Publisher: The History Press, August 2013

Member: $22.74; Retail: $24.99

SKU: 483

The Monitor Boys

By John V. Quarstein

The U.S. Navy's first ironclad warship rose to glory during the Battle of Hampton Roads, but there's much more to know about the USS Monitor. Historian John Quarstein has compiled bits of historical data research to present the first comprehensive picture of the lives of the officers and crew who faithfully served.

Paperback: 352 pages

Publisher: The History Press October 2015

Member: $22.74; Retail: $24.99

SKU: 2349

The USS Tecumseh in Mobile Bay

By David Smithweck

The USS Tecumseh led a fleet of 14 wooden ships and four iron monitors entered the bay. A torpedo, poised to strike for two years, found the Tecumseh and sank it in minutes, taking ninety-three crewmen with it. Join author David Smithweck on an exploration of the ironclad that still lies upside down at the bottom of Mobile Bay.

Paperback: 160 pages

Publisher: The History Press , October 2021

Member: $19.80; Retail: $21.99

SKU: 155072

The Civil War on the Mississippi

By Barbara Brooks Tomblin

By Barbara Brooks Tomblin

Drawing heavily on the diaries and letters of officers and common sailors, Tomblin explores the Union navy's fight to win control of the Mississippi. She provides fresh insight into major battles, such as Memphis and Vicksburg, and offers fascinating perspectives from ordinary sailors engaged in brown-water warfare.

Paperback: 388 pages

Publisher: University Press of Kentucky , April 2022

Member: $27.00; Retail: $30.00

SKU: 155095

Featured Books Shop online @ ACWM. ORG

THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR MUSEUM 33

490 Tredegar St., Richmond, VA 23219 NON-PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID RICHMOND, VA PERMIT NO. 2399

in June presents

American Civil War Museum BEYOND United States Colored Troops and the Fight for Freedom

Coming

The

An August Morning with Farragut; The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864

William Heysham Overend, 1883 Oil on Canvas. 10 feet x 6.5 feet

An August Morning with Farragut; The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864

William Heysham Overend, 1883 Oil on Canvas. 10 feet x 6.5 feet

By Samantha Barrett

By Samantha Barrett

By David C. Gompert and Hans Binnendijk

By David C. Gompert and Hans Binnendijk

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut

Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren on the deck of the USS Pawnee standing next to a cannon designed by himself – the Dahlgren gun.

Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren on the deck of the USS Pawnee standing next to a cannon designed by himself – the Dahlgren gun.

– Hunter Davidson to Adm. Stephen B. Luce, 19 April 1897

– Hunter Davidson to Adm. Stephen B. Luce, 19 April 1897

– Hunter Davidson

– Hunter Davidson

Officers of the USS Monitor pose in front of its turret on July 9, 1862. Lt. Samuel Dana Greene, the executive officer, is seated on the far right.

Hunter Davidson died in 1913 at the age of 86 in Paraguay and is buried in Paraguarí, Paraguay.

CONFEDERATEVETS.COM

Officers of the USS Monitor pose in front of its turret on July 9, 1862. Lt. Samuel Dana Greene, the executive officer, is seated on the far right.

Hunter Davidson died in 1913 at the age of 86 in Paraguay and is buried in Paraguarí, Paraguay.

CONFEDERATEVETS.COM

By John V. Quarstein

By John V. Quarstein

By Barbara Brooks Tomblin

By Barbara Brooks Tomblin