History Explorer Day

March 11

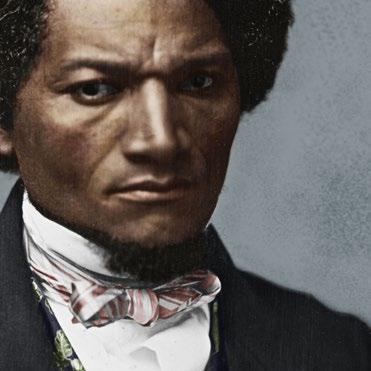

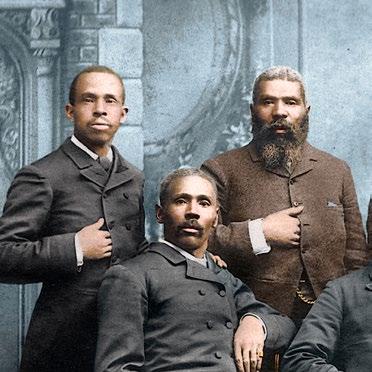

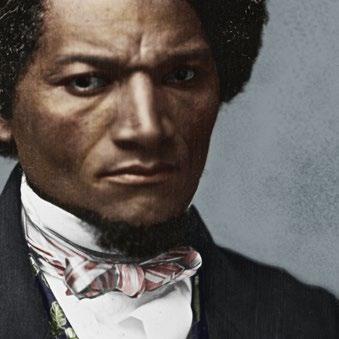

Interact with reproduction artifacts & listen to a Frederick Douglas living historian.

History Explorer Day

March 11

Interact with reproduction artifacts & listen to a Frederick Douglas living historian.

ACWM held the first Holiday Open House at Appomattox in December 2022. The event brought the community together with music, merchants, children's activities, and a Thomas Nast-themed Santa.

The Appomattox Campaign

March 28

The battles of Five Forks, Petersburg, Sailor’s Creek, and Cumberland Church.

The Battles of Appomattox

April 6

April 8 & 9, 1865. Who were the tragic, final casualties before the surrender?

acwm.org/events

Neither Slave Nor Free

April 8

When did freedom come for enslaved people of Appomattox, and what did that freedom look like?

Appomattox will be hosting several Spring programs, including presentations by Patrick Schroeder (N.P.S.), Prof. William C. Davis, and the Rev. Al Jones. Visit ACWM.org for information and registration. @acwmuseum @acwmuseum

The Confederate Peace Makers

April 8

Prominent Confederates work with Lee to maneuver a surrender short of abject defeat.

@americancivilwarmuseum

@theamericancivilwarmuseum

Magazine

Publisher

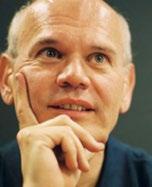

Rob Havers , Ph.D.

ACWM President & CEO

Managing Editor

Robert Hancock

Art Director/Designer

John Dixon

Editorial Review

Ana Edwards

Kelly Hancock

Jeniffer Maloney

Museum

Board of Directors

Daniel G. Stoddard, Chair

Claude P. Foster, Vice Chair

Walter S. Robertson III, Treasurer

Mario White, Secretary

J. Gordon Beittenmiller

Hans Binnendijk, Ph.D.

Audrey P. Davis

Sally Diggs Fletcher

George C. Freeman III

Hon. David C. Gompert

Bruce C. Gottwald, Sr.

Monroe E. Harris, Jr., D.D.S.

Rob Havers, Ph.D.

Richard S. Johnson

Donald E. King

John L. Nau III

William R. Piper

Lewis F. Powell III

O. Randolph Rollins

Kenneth P. Ruscio, Ph.D.

Leigh Luter Schell

Julie Sherman

Roderick G. Stanley

Ruth Streeter Foundation

Board of Directors

Donald E. King, Chair

J. Gordon Beittenmiller

David C. Gompert

Walter S. Robertson III

Kenneth P. Ruscio Ph.D.

Jeffrey Wilt

Warm greetings from Richmond, Virginia, and welcome to the second edition of Ironclad, the magazine of the American Civil War Museum. I hope you enjoyed the first edition. It is a substantial upgrade both in terms of production values and articles but is also emblematic of our ambition. So far, responses to the new publication have been very positive ranging from “Bravo!” through “Congratulations on Volume 1, Issue 1, of Ironclad! Outstanding work!” all the way to “another win for the ACWM!” While just a sampling of the immediate responses, they are representative of the positive feedback we received.

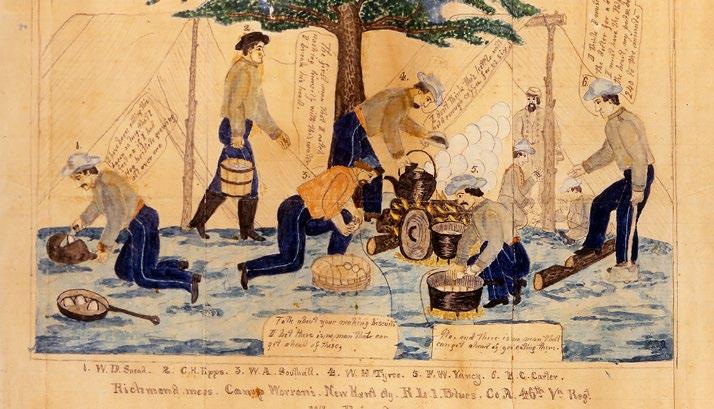

Needless to say, issue #2 builds on the standards of issue #1 with a fine array of articles; Robert Hancock offers another perspective on the soldier’s experience of “soldiering” in As Good as a Heap of Women Would Do, while John and Ruth Anne Coski provide a fine biographical sketch of Eleanor Brockenbrough, to whom the American Civil War Museum owes a significant debt of gratitude for her work in collating and cataloging our works-on paper collection, in Eleanor S. Brockenbrough: “an incredibly bright lady who knew her collection like nobody else.” This article is also a timely reminder that this peerless collection, still owned by the ACWM, exists in its entirety and is housed at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture where it is being re-cataloged and digitized. Robert Hancock also provides a fascinating account of the life and times of the “other” Jeff. Davis who served with the forces of the Union.

As always we have been busy with a raft of educational and public programming, and more information on precisely what we have been up to can be found on page 4. We continue to collect artifacts to bolster our collection, and a focus on one particular item, a snuff box, is to be found on page 10. While we work to expand our collection, preserving what we already have is as important. The White House has been undergoing extensive work in recent months as part of Phase One of a comprehensive refurbishment. The house is not only an artifact, but the site of history too. The story of Betsey and James, enslaved people working there during the war, is fascinating and provides yet another perspective on the historic home.

Lastly, I hope you will take note of our impressive upcoming programs. The Spring Program Series at Tredegar featured on page 30, provides highlights of "The Civil War & Remaking America" discussions, and inside the front cover you will find program offerings for ACWM-Appomattox before and during the Freedom Week celebration in Appomattox.

I hope to see you soon at the American Civil War Museum! Happy New Year!

Dr. Rob Havers President & CEO

Scenes from the Museum over the past few months. Highlights include visitors from the Dutch Embassy, Sports Congress Convention, Civil War & Reconstruction History Center (N.C.), Education programs, and White House renovations.

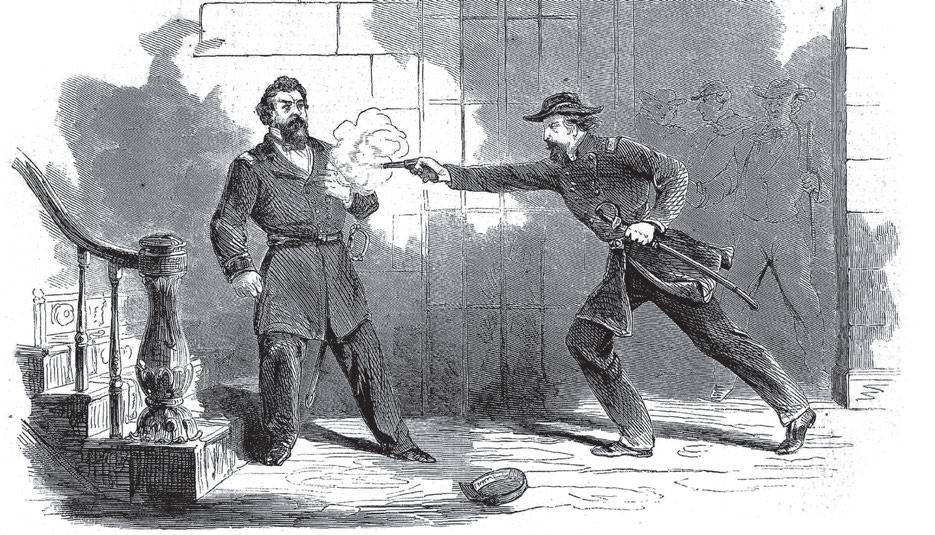

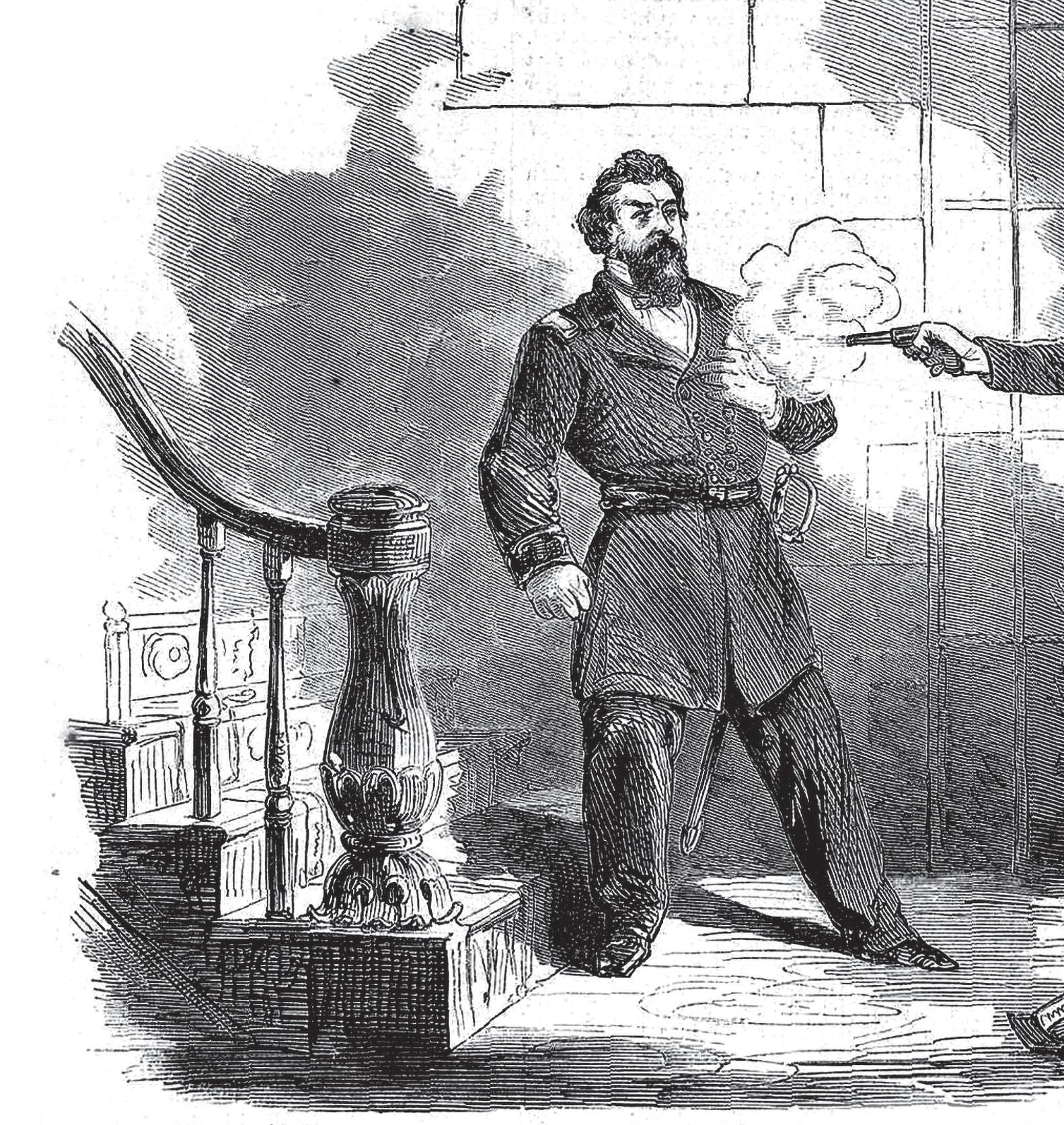

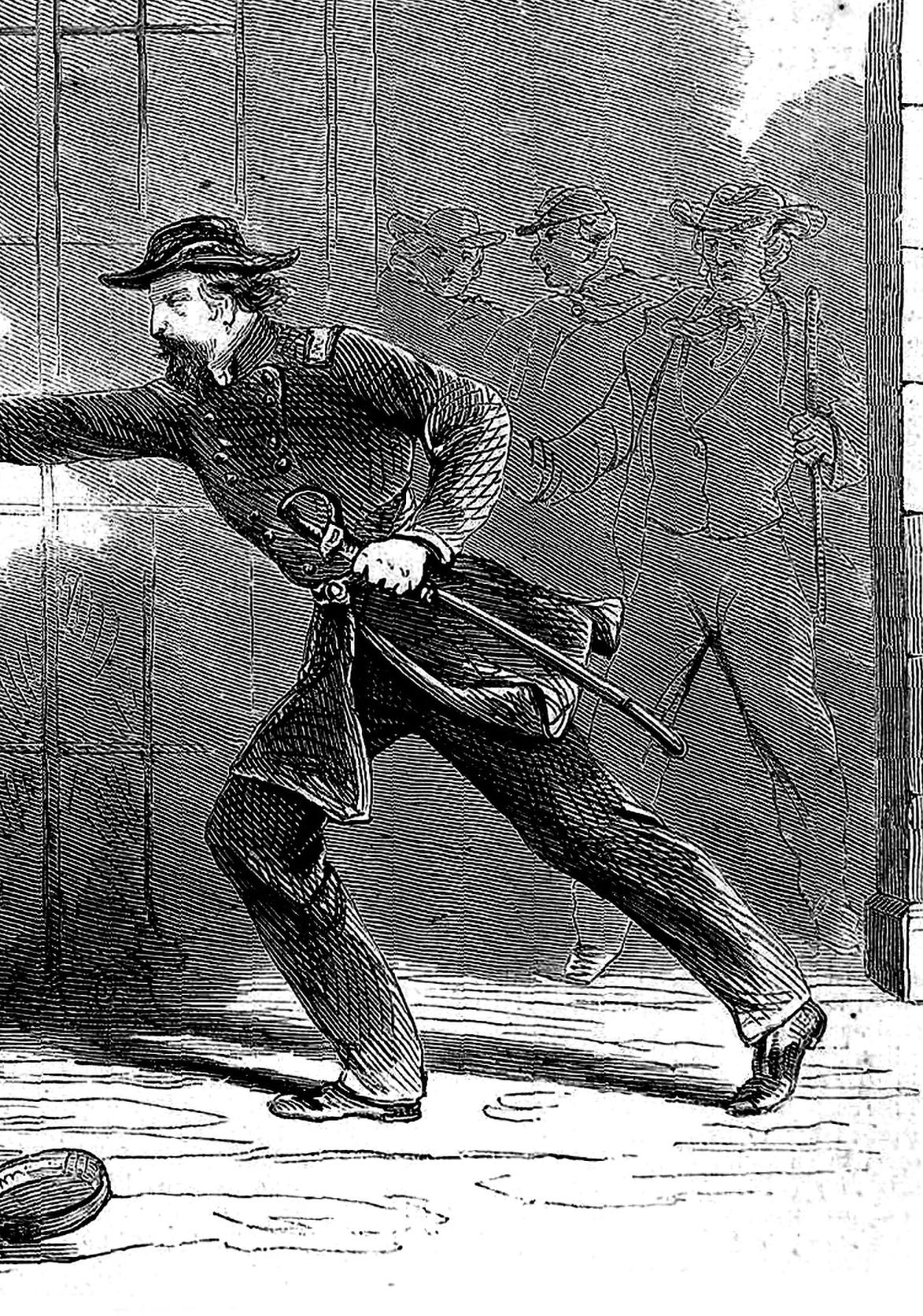

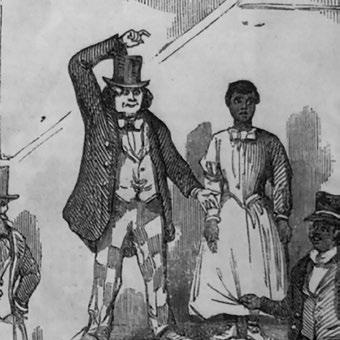

An illustration by Henry Mosler for Harpers Weekly published on October 18, 1862 depicting Gen J.C. Davis shooting Gen. Nelson. An investigative reporter and illustrator, Mosler visited the Galt House in Louisville, KY shortly after the shooting to interview witnesses' first-hand accounts of the incident. He recorded notes and sketches in a journal, which is available online through the Smithsonian Institute: www.aaa.si.edu/collections.

General Jefferson C. Davis, U.S.A., is probably best remembered for two things: the similarity of his name to the President of the Confederate States (Jefferson F. Davis, twenty years his senior and not related), and for killing a fellow officer after an argument.

Jefferson C. Davis was born in Indiana in 1828. His military career started at the age of nineteen when he joined the 3rd Indiana Volunteers. He was cited for bravery during the Mexican-American War, and he received his commission as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army. He was present at Fort Sumter during the bombardment that started the Civil War and fought in a number of battles including Pea Ridge, Arkansas, after which he was given the brevet rank of brigadier general of U.S. volunteers. He was next put in charge of the defense of Louisville, Kentucky, under threat by the Confederate advance into that state. He quickly fell afoul of his commanding officer, Major General William “Bull” Nelson. When asked how the defensive preparations were going and how many men he had mustered for the defense of Louisville, Davis was unable to give any specifics, replying, simply, that he did not know. Nelson flew into a rage and dismissed Davis, ordering him to report back to General Wright in Cincinnati. “You have no authority to order me,” replied Davis. Nelson told the provosts to forcibly remove Davis if he did not go on his own. Davis quickly packed his bags and reported to General Wright in Cincinnati.

When General Buell took over command from Nelson, Davis was sent back to Louisville as the army was in need of experienced officers. While Nelson was no longer in overall command, he was still present. Davis ran into “Bull” Nelson at the

continued on next page

continued from previous page

hotel desk of the Galt House, used as the U.S. headquarters in Louisville. He demanded an apology from Nelson for his earlier reprimand and dismissal. “Go away, you damned puppy,” Nelson replied. “I don’t want anything to do with you!” Events quickly spiraled out of control after Davis angrily threw a registration card, which he had balled up in frustration, in General Nelson’s face. Nelson’s response was to backhand Davis across the face. As “Bull” Nelson was six inches taller and twice his weight, Davis’s immediate response was to ask Oliver Morton, Indiana’s governor, standing nearby: “Did you come here, sir, to see me insulted?” General Nelson stormed off. Davis went looking for a pistol.

Davis found Nelson in his office, aimed the pistol at his chest and pulled the trigger. Nelson died a half hour later. Oddly, charges were never filed, there was no court-martial, and Davis, never denying (or regretting) shooting Nelson, simply returned to duty. He was later given command of XIV Corps during the Atlanta Campaign.

Controversy continued to plague Davis’s career. During Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” the U.S. Army found themselves responsible for thousands of recently freed slaves. After Davis’s men crossed the river near Savanna, he had the pontoon bridge taken up, leaving about 600 people stranded and at the mercy of the pursuing Confederates. Those who could not escape were captured and returned to bondage. Davis ended the war as a major general by brevet only, so he was reduced to colonel of the 23rd Infantry. He died in Chicago in 1879.

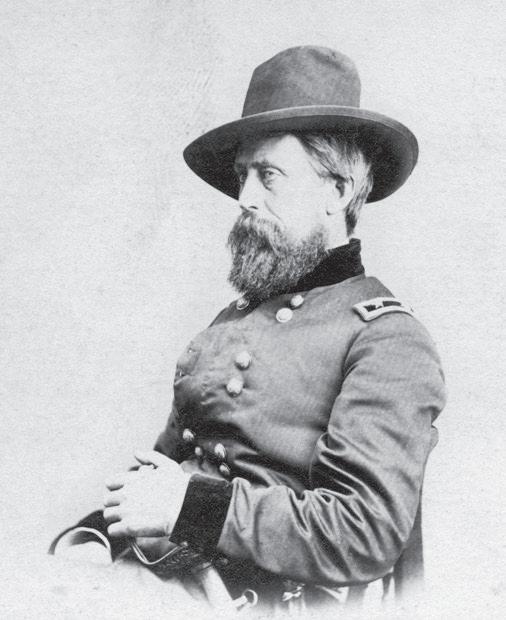

IMAGE: ACWM, 0985.14.00172

General William "Bull" Nelson, ca 1862.

IMAGE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

"GORobert Hancock is the ACWM Senior Curator and Director of Collections. (Top) Major General Jefferson C. Davis, ca 1864.

noun

1. a feeling of doubt or hesitation with regard to the morality or propriety of a course of action.

Author of Four Years in the Stonewall Brigade, John Overton Casler, a self-described “high private in the rear ranks,” served with the 33rd Virginia Infantry during the war.

Casler described the grisly habit of plundering the dead: “Sam Nunnelly came to me and said we would get over in front of our works that night and plunder the dead….I told him I would not do it, as we would be in danger of being shot by our own men as well as the enemy. But he said he would go by himself and crawl around and ‘play off’ wounded. So, he went, and was gone all night, coming back at daylight. He got three watches, some money, knives, and other things. He would risk his life anytime for plunder.”

According to Casler, soldiers soon lost any qualms over the moral dilemma associated with robbing the dead. “It was difficult for a soldier to figure out why a gold watch or money in the pocket of a dead soldier, who had been trying to kill him all day, did not belong to the man who found it as much as it did to anyone else.”

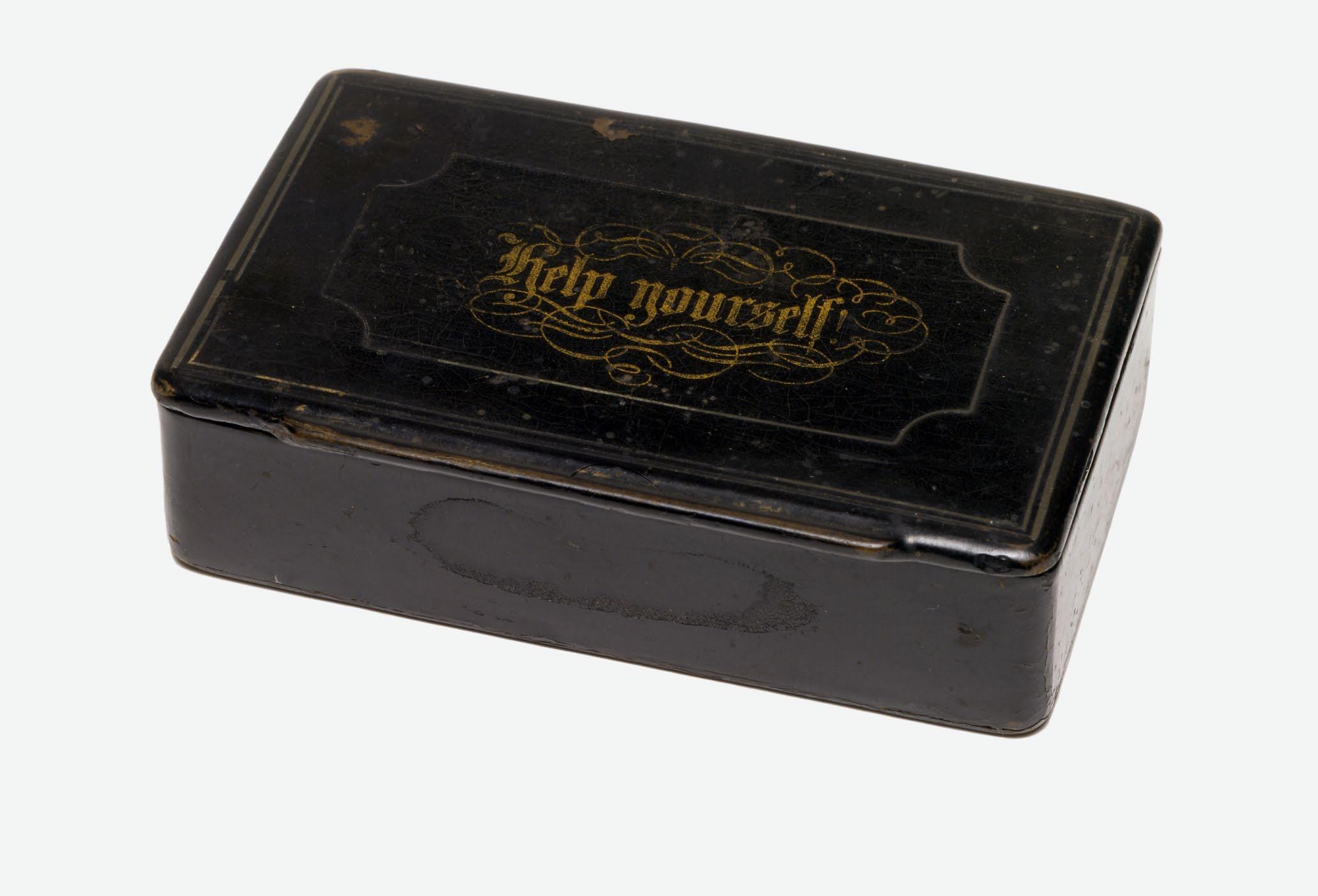

Casler also learned to “liberate” items from the enemy that he needed or might find useful, so long as it involved little to no risk to himself. In the case of this snuff box, he took the inscription “Help Yourself” literally.

This snuff box was taken from a dead Union soldier on the Chancellorsville, Va. battlefield on May 2, 1863, by John O. Casler, 33 rd Virginia Infantry.

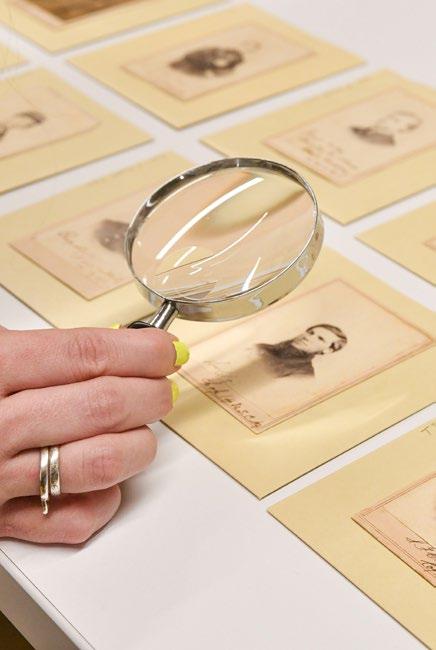

ACWM has numerous artifacts that were "liberated" from the dead including canteens, weapons, binoculars, sewing materials, clothing, badges, photos, and other personal items. Find more items by searching the phrase "found on battlefield" in the ACWM Collections online database: acwm.pastperfectonline.com

Snuff Box . ACWM item #0985.13.00100. H-1.5" x W-4.5"x D-2"

Snuff Box . ACWM item #0985.13.00100. H-1.5" x W-4.5"x D-2"

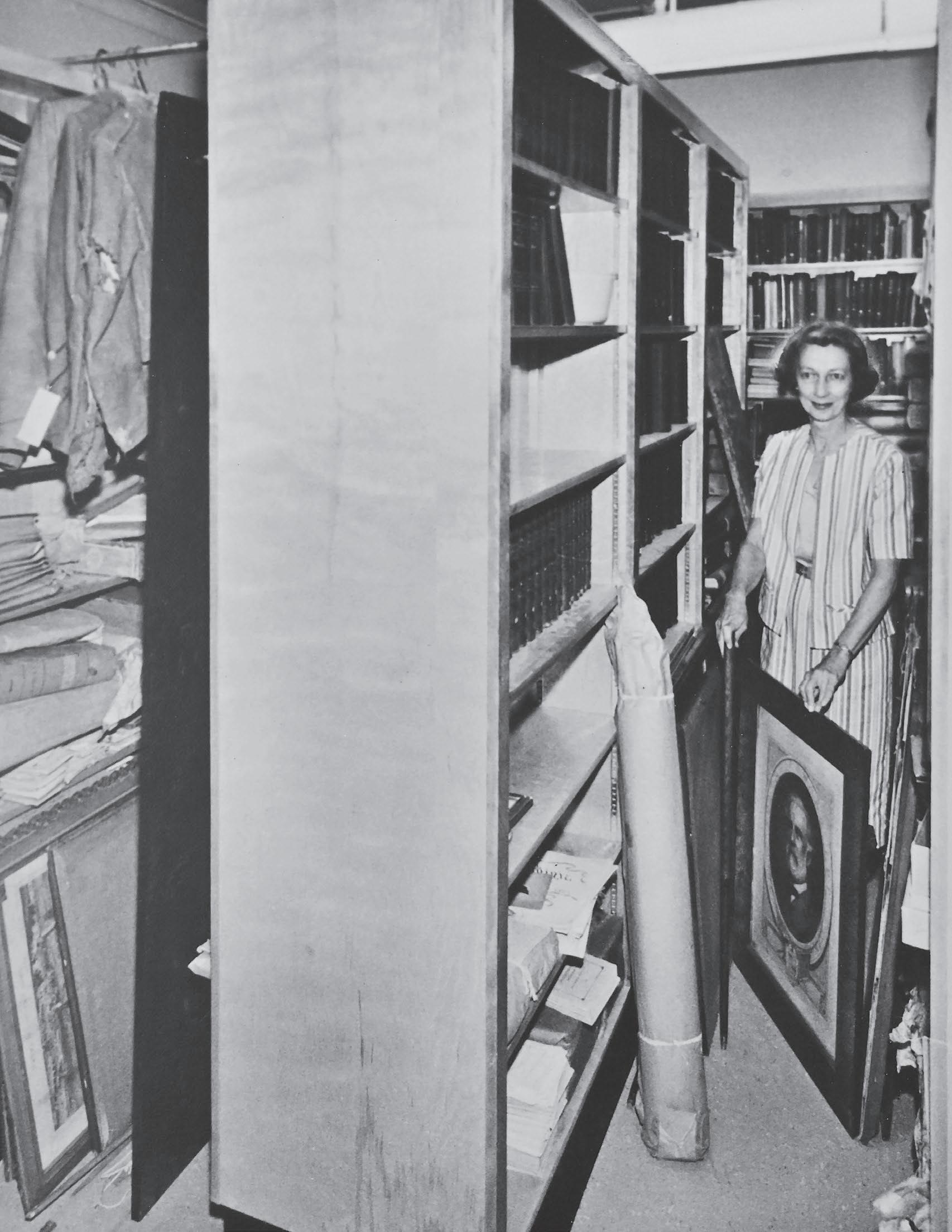

Eleanor Brockenbrough in Collections at the Confederate Museum, July 1964.

IMAGE: ACWM. ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN THE RICHMOND TIMES-DISPATCH

If you wish to research in the American Civil War Museum’s valuable manuscript or rare book collections, you need to visit the Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library Reference Desk at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture (known previously as the Virginia Historical Society). There you will find the collections formerly housed in The Museum of the Confederacy’s Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library.

Many readers will ask: who was this Eleanor S. Brockenbrough and why has she had research facilities named for her at two different institutions? Older readers will rush to answer with enthusiasm: she was a walking card catalog and the brains, heart, and soul of one of the most valuable Civil War history manuscript collections in existence.

The woman who devoted her life to assisting others study Confederate history seemed born to the job. She was a collateral descendant of Dr. John Brockenbrough, the builder of the Clay Street residence (later the Confederate Executive Mansion or “White House of the Confederacy”) that housed her library and her office and the granddaughter of Confederate Colonel John Mercer Brockenbrough, who commanded – ineffectively – a brigade at Gettysburg. (“Oh, yes, he was a bad colonel, but a fine grandpa,” she once quipped.)

Eleanor Sampson Brockenbrough was born on Washington’s Birthday, 1910, the third of seven children of John Mercer Brockenbrough and Clara Doyle Kenny Brockenbrough, the daughter of Irish immigrants. Her mother’s father fled Ireland during the Potato Famine and became a successful businessman in New York and in Baltimore. Clara met her future husband through mutual friends in Norfolk, Virginia.

Catholic in a predominantly Protestant community and a blend of Old Virginia and nouveau riche, the Brockenbroughs established a stately family seat at “Doolough,” an impressive Tudor Revival style home on the north bank of the James River on Pumphouse Road. Eleanor lived there most of her 75 years.

Her first formal education was a Montessori School. According to her sister, Mary Austin, Eleanor liked to say that she “flunked kindergarten three times.” She learned piano and dance and gave public recitals. She attended St. Catherine’s School in Richmond, then followed her sisters

to the Academy of the Sacred Heart in Noroton, Connecticut, where she graduated in 1927.

Unlike her sisters, Eleanor was not interested in attending college, but took private business courses for a few years. Clara Brockenbrough instilled in all her children a love of books, and Eleanor showed a life-long interest in history.

Hard times hit the Brockenbrough family in January 1930 when their father died of heart disease at 66, and the full force of the Great Depression threatened their once firm financial foundation. Although living in diminished circumstances, the Brockenbroughs were not poor and Eleanor was not compelled to work outside the home. She shared

her mother’s interest in gardening and became something of a handyman around the family estate.

Her association with the Confederate Museum may have begun on a tour there with a Girl Scout troop (though she certainly knew of it through her distant family connection) when she met House Regent India Watson Thomas. Thomas was the third unmarried woman to serve as the administrator and de facto curator of the collection. She had assumed the job a few years earlier upon the resignation of second House Regent Susan Harrison, for whom Thomas had served as Assistant House Regent since 1925. Eleanor Brockenbrough in turn became Thomas’ assistant in late 1939.

More than 33 years later, a reporter writing a profile about Eleanor Brockenbrough asked how she began at the Museum. “I just walked in one day and asked Miss India for a job,” she replied.

She ended up working at the Museum for 40 years, but her tenure almost ended after only seven. In November 1946, she submitted her resignation, explaining that she could not afford to live on her salary ($75 per month). The Museum Board asked her to withdraw her resignation, increased her salary to $100 a month, and rearranged the work schedule so that she and India Thomas could each take off every other Saturday.

Eleanor learned about the Museum and its collections on the job and from India Thomas. The two women worked together and established a mutual respect and fondness. They also established a mutually-satisfactory division of labor. “Miss India” was the de facto director and curator of the object collections. Eleanor handled the paperwork and was the de facto librarian, and her title later reflected that focus.

Over the decades, the two women and their all-female board of trustees operated the Museum on a shoestring budget and dreamed of building an annex that would accommodate the collections that had long ago outgrown the rooms of the former Confederate Executive Mansion. India and Eleanor kept up with the evolving standards of their profession, attending conferences of the Southeast Museums Conference and other organizations.

Eleanor probably expected to succeed India Thomas as House Regent as she had succeeded Susan Harrison. Instead, as Miss Thomas approached her 70th birthday with visibly diminished capacities, the Museum board hired a consultant to assess its long-term

India Watson Thomas (left) and Eleanor Brockenbrough on the Confederate Museum's portico. The photograph was taken by Bradley Smith and published in Holiday magazine in April 1948.

India Watson Thomas (left) and Eleanor Brockenbrough on the Confederate Museum's portico. The photograph was taken by Bradley Smith and published in Holiday magazine in April 1948.

future. In light of the consultant’s recommendation, the Board decided that “the time had come to employ a trained professional director” – specifically “a man who will eventually become director of the Museum” – and to gently nudge India Thomas into retirement.

Over the next 17 years, Eleanor found herself holding the position of assistant director to three successive male executive directors: Peter Rippe from 1962-1968, Kurt Brandenburg from 1969 to 1977, and Edward D.C. “Kip” Campbell, Jr., beginning in 1978. In the intervals between them, she served as acting director.

The situation was fraught with potential tension, but Eleanor swallowed whatever resentment she may have felt. “From the day I arrived Eleanor was gracious and helpful in many ways,” Kurt Brandenburg remembered in 2019. “She introduced me to the Museum’s physical and operational nuts-and-bolts, and over the years she frequently provided useful information on the history of the museum and its board, and on the wider community of supporters.” She was, he added, “completely dedicated to the museum and its collections.”

Pride in her work and in the Museum and its collections and sharing them with visitors was Eleanor Brockenbrough’s chief motivator. She later reminisced to “Kip” Campbell, how, during World War II, the museum had “bustled with soldiers with little to do and with little to spend coming to the Museum for tours” – and how she particularly enjoyed talking with nonsoutherners and introducing them to the subject of the Confederacy.

Eleanor Brockenbrough was proud of her Virginia lineage and expressed what Kurt Brandenburg described as “deep sadness for the countless southern homes and families devastated by the war.” But she was not what the era knew as a “Professional Southerner.” She told the reporter in 1972 that she did not consider herself a “Confederate buff” and did not “go digging around old battlefields for shells and buttons.”

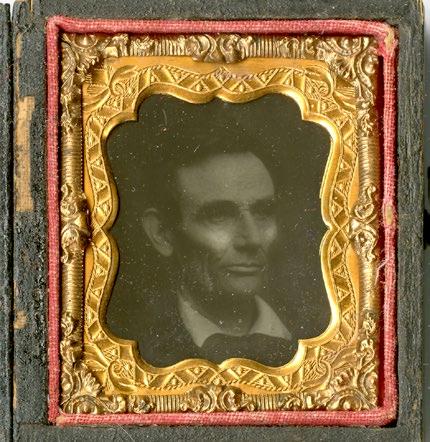

She was uncomfortable with those who, a century after the war, insisted on keeping alive the war’s animosities. She expressed admiration for both Robert E. Lee, especially for his postwar admonition to be good American citizens, and for Abraham Lincoln. Peter Rippe recalled her saying that “’if the South had understood Abraham Lincoln and read his speeches, the Civil War might not have happened.”

“She had great respect for the protagonists rather than for one side over the other,” explained Kip Campbell. The Civil War was “a period of history, it was the past, it deserved attention and it deserved respect for sacrifices, etc., but, again, she never to me ever expressed anything like affection or nostalgia for another time. The collection and its stories were to be respected, studied, and shared but not celebrated.” Historian Emory M. Thomas agreed with Campbell’s insight. Confederates, he noted, “were human beings, and she “acknowledged and understood their struggle.”

Although she showed no special interest in any particular chapter of Civil War history, she mined the collection to write deeply-researched articles for the Museum’s Newsletter inaugurated in 1963 (the lineal ancestor of this magazine). Among her articles were

features on the Confederate Secret Service, the Confederate Patent Office, Christmas in the Confederacy, carte-devisite photographs, and the evacuation and occupation of Richmond.

She was more interested in people of the era than in military organizations and campaigns, observed historian Robert K. Krick, for whom she provided valuable assistance while researching the first edition of his book, Lee’s Colonels. “She kind of liked scoundrels” in history, Peter Rippe remembered. But she held Confederate General Patrick Cleburne “in great esteem,” Kurt Brandenburg recalled.

In between her other duties, she also responded to the lion’s share of the correspondence that the Museum received. In March 1969 she described to the Board the variety of letters received: (1) “The requests for reservations for groups, (2) students’ requests for information, (3) requests for pictures and records, and (4) ‘impossible’ mail requesting information which often requires time consuming answers.”

When the Museum finally achieved its dream of a new building in 1976, she helped research and write the new exhibits, contributing background text and quotations from primary sources, especially for sections on civilian life. Peter Rippe recalled her approach to writing exhibit labels: “The artifacts should stand alone.” / “We will not exaggerate on the labels.” / “Concentrate on the artifacts” – and she used the professional term, artifacts, instead of the term, relics, that her predecessors had used.

She also participated in the early stages of converting the former Confederate Executive Mansion from a museum

She was completely dedicated to the museum and its collections.

Kurt Brandenburg

building back into an historic home. Kip Campbell recalled her concern that consultants were too focused making the restored house “too artsy… too artificial and “unreal.” She wanted to make sure it remained “real” and lived in – an executive mansion, not a decorative arts showpiece.

As assistant house regent, assistant director, and occasional acting director, Eleanor was familiar with all aspects of the Museum’s operations. Kurt Brandenburg, who is an authority on Civil War weapons, recalled that she deferred to him on matters related to the object collection. “The library, however, was her particular domain and here our roles were largely reversed,” Brandenburg noted. “Eleanor pursued the growth and improvement of the library’s collection with passion and impeccable judgment, for which the board and I, along with the scholarly community, were truly grateful.”

Working her entire career for an institution whose collections and reputation far exceeded its financial resources, Eleanor learned how to make the most out of what she had. Like her predecessors, she put in long hours and was miserly with office supplies.

Her favorite items in the collection were Confederate Imprints (official and unofficial items printed in the Confederate states during the War), and she used ingenuity to improve the Museum’s already rich collection. She worked closely with imprint authorities, including Richard Harwell (who was

Kip Campbellediting a new authoritative catalog of imprints) and Robert K. Krick, and traded some of the many duplicates and triplicates for new imprints.

Generations of scholars, genealogists, and casual researchers knew Eleanor Brockenbrough as the face of the Confederate Museum and the “gatekeeper” of the collection. Upon first exposure, her manner could appear stand-offish, even “icy,” and she could intimidate even the most accomplished Civil War historians. “Reserved at first – classic Richmond” is how Emory Thomas (himself a native Richmonder) remembered her, but “she warmed to you.” If she knew you were serious about your work, “she worked very hard for you.”

Thomas’s first impression was that she was “an incredibly bright lady who knew her collection like nobody else.” "Whip-smart herself” in Kip Campbell’s judgment, she recognized and respected intelligence in others.

She was especially engaged with the Papers of Jefferson Davis project, assisting its editor, Haskell Monroe, with photocopying the treasure trove of Davis papers in the Museum library. She worked closely with Lee Wallace, Louis Manarin, and other historians involved in the Civil War Centennial research projects.

Although the library had a card catalog, she preferred to interrogate researchers, learn their interests and their needs, and identify the documents that would help them. Her colleagues attributed this apparently proprietary attitude toward the library to several causes beyond her encyclopedic knowledge of the collection. Most of the cards in the card catalog were handwritten and obviously

not up to professional standards, and the cards often included the names of donors. Limiting access to the catalog protected the Museum’s sensitive information and its reputation.

Housed in the basement of the former Confederate executive mansion, the library was small, and researchers worked in what was also her own work space. Personal attention and oversight was as inevitable as it was helpful.

A September 16, 1963 meeting of an advisory committee heard a report on the state and future of the library collection. Director Peter Rippe described the collection as “one of the most valuable collections of manuscripts and documents of the Confederacy in existence” housed in “cramped, unsuitable quarters in a space that is badly needed for [other] storage.” Not for the first or last time, the Museum considered transferring the collection to the Virginia Historical Society, but decided to renovate the basement storage spaces as finances allowed.

In the May 1964 Newsletter, Eleanor Brockenbrough described the renovation work in a column she entitled “News from the Library: -- or, ‘A Report from the Field of Battle.’” After describing the planning and execution of the job, she concluded: “All of which convinces us that the ideal librarian must be an agile sylph with the strength of Samson, the nose of a bloodhound and the memory of an IBM machine.” Two months later she commented giddily to a newspaper reporter that “We now have shelf space to grow in.”

In the mid-1960s, Eleanor gained the assistance and camaraderie of a young student. Ellen Gay Detlefsen of continued on next page

She had great respect for the protagonists rather than for one side over the other.

Richmond visited the Museum to research her undergraduate honors thesis at Smith College. She ended up working several summers as an assistant in the library. She dedicated her thesis to Eleanor and a Smith College archivist “in affectionate appreciation for their introduction to the intellectual adventures of historical research.”

Located as it was in the basement of a four-story building, the library suited Eleanor Brockenbrough not only because of her knowledge and talents, but also because of her physical ailments. A slight woman (5’4” and weighing under 100 pounds), she was not frail, but she suffered from rheumatoid arthritis and became increasingly stooped. Historian Robert Krick knew about her arthritis but he “never saw a hint of physical discomfort.”

That changed when she fell on the ice at the Museum in the mid-1970s, underwent spinal fusion surgery, and was homebound for almost a year.

Like all of her Confederate Museum predecessors, she was married only to her job and continued to work past age 65. A naturally shy person, she was, according to her younger sister, always conscious and critical of her appearance. Others saw a pleasant and impeccably neat and fastidious woman. Peter Rippe described her as “a small woman of stature” with a beautiful smile, a soft, pleasant voice and a penetrating wit.

Kip Campbell became director during Eleanor’s last years with the Museum and established a special relationship with her. Even after her formal retirement in 1979, he visited Doolough frequently to apprise her of developments at the Museum and seek her advice. Although bedridden, she was “interested and engaged” in “everything you could bring up –really,” Campbell recalled. “I cannot emphasize enough that she was almost ‘elfin’ in her delight.” She “laughed very easily,” often culminating in a loud “cackle.”

On the 40 th anniversary of Eleanor Brockenbrough’s hiring, the Museum Board launched a concerted effort to raise funds for a library in the new museum building. “The Library has always been Eleanor’s fondest dream,” wrote Board President Penelope Eure, “and its completion would be the perfect way to recognize and pay special tribute to someone who has given so much time and devotion to the Museum.”

Before long, the funds were in hand. The Museum dedicated the Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library on April 10, 1981.

Four years later, on August 13, 1985, Eleanor Brockenbrough died of cancer in a Richmond nursing home. She was buried in Hollywood Cemetery.

Over the ensuing 33 years, the library that bore her name hosted thousands of researchers, including many who had known and worked with her. As part of the reorganization that created the American Civil War Museum in 2014, the Museum negotiated a licensing agreement with the Virginia Historical Society, by which the VHS would store and make available the manuscript, Imprint, and rare book collections.

Still the formal property of the Confederate Memorial Literary Society (CMLS) – the organization for which Eleanor Brockenbrough worked – the library collections are part of an even larger and more valuable collection of Civil War resources.

Asked what made Eleanor Brockenbrough most proud of her work, Peter Rippe replied without hesitation: “The library, and recognition of the library in published books.” Eleanor received frequent and fulsome acknowledgments from noted historians, such as Frank Vandiver, Bell Irvin Wiley, James I. “Bud” Robertson, Jr., Emory Thomas, Richard Harwell, and Robert K. Krick. In his A History of the Confederate States Navy, Italian military historian Raimondo Luraghi thanked Eleanor for her “invaluable help in wading through the ‘high sea’ of manuscripts and papers” at the Museum, as well as for her “acute and thoughtful suggestions.”

The greatest tribute to Eleanor Brockenbrough and her life’s work is for historians and researchers to continue to use and to cite the CMLS manuscripts at the Virginia Museum of History and Culture. And be sure to visit the Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library Reference Desk while you’re there.

Dr. John M. Coski was the director of the Eleanor S. Brockenbrough Library from 1996-2009. Ruth Ann Coski was the library manager, 1996-2006, and authored the entry about Eleanor Brockenbrough in the Dictionary of Virginia Biography.

[Eleanor provided] invaluable help in wading through the ‘high sea’ of manuscripts and papers.

Raimondo Luraghi

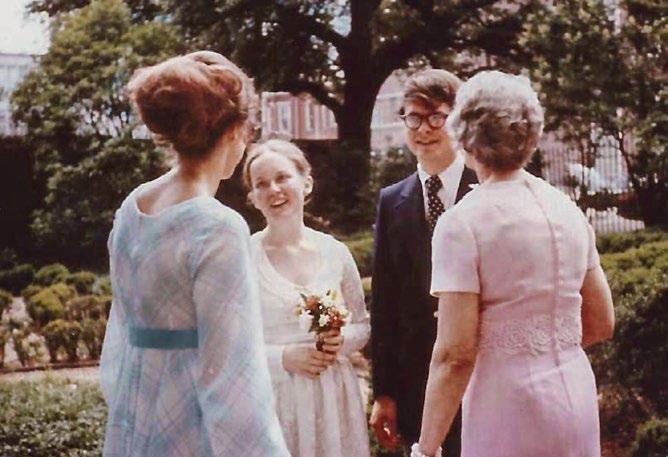

Ellen Gay Detlefsen (inset) was Brockenbrough's assistant in the 1960s and subsequently earned her Master’s and Doctorate in Library Science at Columbia University. Detlefsen wrote her dissertation on the Confederate printing industry, exploiting the Confederate Imprint collection that Eleanor Brockenbrough worked so assiduously to build. She spent several more summers as “assistant to the assistant director,” performing “every task imaginable in the operation of the Museum,” Eleanor wrote. An educator and researcher for 42 years, she is Professor emerita at the University of Pittsburgh's School of Information Sciences. Detlefsen also held her wedding reception with her husband, Charles F. Reynolds III, on the White House portico and in the garden (below).

Member support enables us to provide educational programming, expand our collection, and deliver on our mission to explore the stories and legacies of the Civil War.

We thank you and hope to see you soon at the American Civil War Museum!

By Kelly Hancock

By Kelly Hancock

WWhen Jefferson and Varina Davis moved into the house at 12th and Clay in Richmond, Virginia— the house they would call home throughout the Civil War—they brought with them a small number of enslaved servants. We can document three: Robert Brown and James and Betsey Pemberton. Robert Brown will be the subject of another article, but of special interest today are James and Betsey.1

From what we can gather, James and Betsey were both born into slavery on the Davises plantation. James Pemberton said he belonged to Davis “ever since he was a small boy,” and Varina in referring to her maid, whom we know was Betsey, wrote that she “was an ignorant girl born and brought up on our own plantation.”

James and Betsey were young, most likely in their early twenties, at the time of the Civil War. Although marriages between enslaved people were not legally recognized, they did occur. The Davises appear to have acknowledged the union between James and Betsey. In a letter written by Varina when she was in Raleigh in the spring of 1862, she asked Jefferson Davis to relay “Betsey’s love to Jim, and tell him she is quite well.”

James was both a footman or table servant and a body servant to Jefferson Davis. As such he was often with the Confederate president. For instance, in the fall of 1863, he traveled with Davis to the Western Theatre. There Davis sought to sort out the discontent in the Army of Tennessee under the command of General Braxton Bragg and visited General P.G.T. Beauregard to assess the situation in Charleston.

In addition to serving as a lady’s maid, Betsey also was a nursemaid to William Howell, or “Billy,” born in December 1861, shortly after the Davises moved in. This job may not have been one for which Betsey was particularly suited. Varina wrote from Raleigh praising the care Robert Brown and Catherine, the children’s Irish nanny, had taken of Billy when he was ill but noting only that, “Betsey did her best.” Jefferson Davis, painted a less than stellar portrait of Betsey as a nursemaid. Writing to Varina from Fort Monroe on September 26, 1865, he confessed, “I am haunted by the suspicion that Betsy [sic] treated him [Billy] harshly when an infant and I thought I saw the effect upon him afterwards.”

Mary Chesnut was a close aquientance of

Davis and wrote often in her diary about the Davises.

As personal servants, valet and lady’s maid, they were “compelled to tend to all [the Davises] bodily wants” and were intimately connected to them; however, their relationship with the Davises was drastically different from that of Ellen Barnes McGinnis and James Jones, who have been previously highlighted in this magazine.

Unlike Ellen and James Jones, who remained in touch or reconnected with the Davises, James and Betsey Pemberton charted a different course. In the winter of 1864, they set out for Union Army lines. According to diarist Mary Chesnut, they “decamped” on January 8:

The President's man, Jim, that he believed in as we all believe in our own servants, ‘our own people,’ as we call them, and Betsy [sic], Mrs. Davis's maid, decamped last night. It is miraculous that they had the fortitude to resist the temptation so long.…

James traveled a little over two weeks before entering Fort Monroe and being interviewed by General Benjamin Butler. He stated that he “came by the way of Charles City Court House, came up from Williamsburg, and on up to the Fort.” Butler was so impressed by the information that Pemberton had to share that he sent him on January 25, to Washington,

D.C. to meet with Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. In a letter to Stanton, Butler explained:

A table servant of Jeff. Davis has come within our lines. I have examined him and think him truthful and reliable, and his information of sufficient consequence to send him to you. He reports, and I believe him, the rebel Vice-President having fled to Europe without the knowledge of Davis. The boy’s name is James Pemberton. I send by mail minutes of a hurried examination.

In the “hurried examination,” Pemberton incorrectly testified that Alexander Stephens had fled, but accurately reported that there was a “great deal of feeling against General Bragg.” He mentioned that Davis’ hope was to keep the war going in Georgia until “Lincoln’s time was out.” (Lincoln would be coming up for reelection in ten months.) Much of the information that Pemberton revealed was from his fairly recent travels with Jefferson Davis.

On a personal note, James Pemberton expressed a desire to see William Jackson. Jackson, an enslaved man hired out to work for the Davises early in the war, had seized his freedom in the

continued on next page

Varina IMAGE: NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY Gen. Benjamin Butler, U.S., interviewed James Pemberton and was impressed with his infomation on Jefferson Davis. IMAGE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESSThe letter Gen. Butler, U.S., sent to Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War, concerning James Pemberton's information.

IMAGE: NATIONAL ARCHIVES

continued from previous page

spring of 1862. Pemberton noted that he had seen Jackson’s wife a few days before he left and noted that she “lives about three square from the President’s house.”

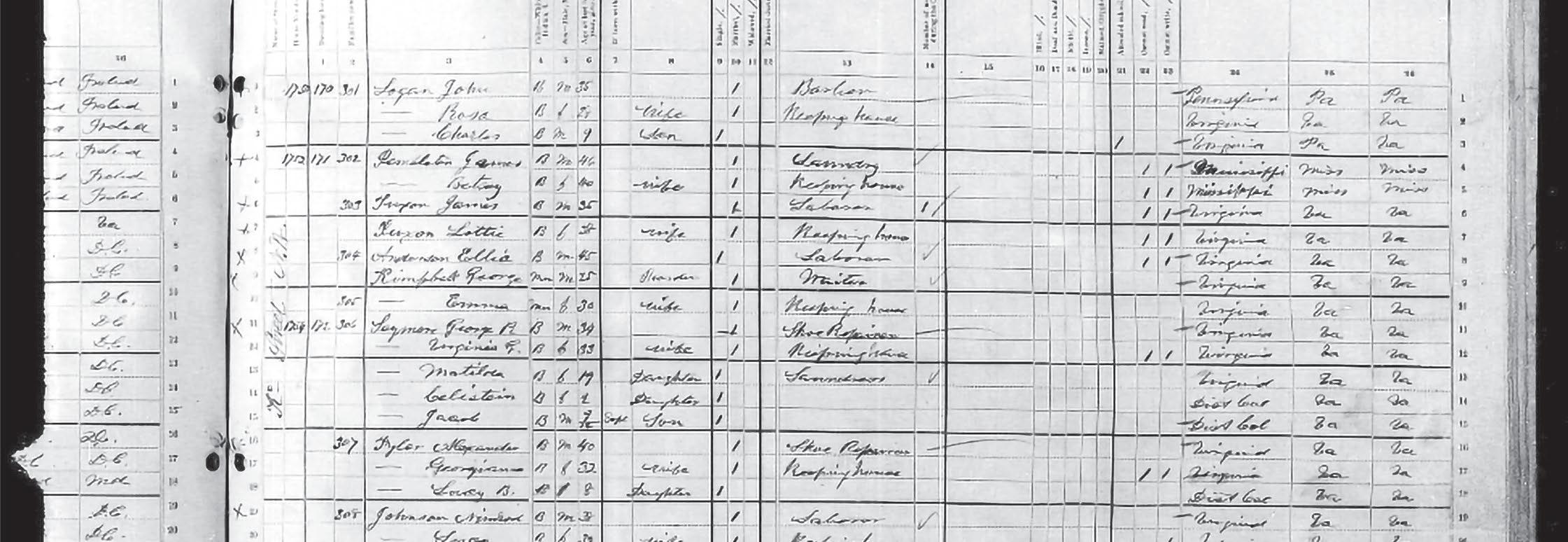

What happened after James Pemberton met with Edwin Stanton remains a mystery. The Anglo-African newspaper reported from its office in Norfolk, Virginia, on February 6, that Pemberton had returned to the city, but the correspondent also noted that he had been provided with a position in the “Treasury department.” It may well be that the Pembertons ended up making their home in Washington, D.C. An 1880 census record has a James and Betsey “Pembleton” (the name is misspelled the same way in an Anglo-African article on January 30), born in Mississippi, living there. James’s occupation is listed as janitor.

That James and Betsey left and never looked back seems to have been somewhat surprising to the Davises or, at least, to Varina. In writing of what was most likely Betsey’s departure, Varina recalled, “one young woman, who was an object of much affectionate solicitude to me, followed her husband off, but systematically arranged her flight, she made a good fire in the nursery and came to warn me that the baby would be alone, as she was going out for awhile. We never saw her afterward.”

Mary Chesnut contemplated, “I do not think it had ever crossed Mrs. Davis's brain that these two could leave her.”

Although James and Betsey’s departure may have been unexpected to the Davises, the February 6 Anglo-African article (which was discovered only about two years ago) provides a possible explanation:

Mrs. Davis is a very bad woman, and one night about 10 o’clock she called Mrs. Pemberton, who was then very ill, from her bed to get something out of a box…After much labor Mrs. P. managed to get up stairs, and told Mrs. Davis that she was unable to unscrew the box. For saying this, Jeff Davis, who was sitting before the fire, bounded from his seat, knocked her down, and then attempted to choke her. After this…Davis did not exchange a word with [Pemberton] for a month.

It was the continual abuse by Davis’s wife of Mr. and Mrs. Pemberton that induced them to leave. This last act on the part of Davis, was wholly owing to her influence.

Newspaper interviews with former servants, whether they were enslaved or free, as well as correspondence provides a positive image of the Davises, so this comes as shocking and strikes a discordant note. Some may be tempted to reject it outright as a complete fabrication. Others may take it at face value and view it as proof of the degrading influence of slavery–not only on the enslaved but on the enslavers themselves. Still, yet, the truth may lie somewhere in between. This information provides a new lens through which to view the Davises and causes us to question long-standing assumptions about life within the Confederate President’s house, illustrating that elements of the past are in many ways a puzzle, the pieces of which we are still striving to put into place.

A page from the 1880 Census in Washington D.C., which records James and Betsey Pemberton. IMAGE: FAMILYSEARCH.COM

A page from the 1880 Census in Washington D.C., which records James and Betsey Pemberton. IMAGE: FAMILYSEARCH.COM

By Robert Hancock, ACWM Senior Curator

By Robert Hancock, ACWM Senior Curator

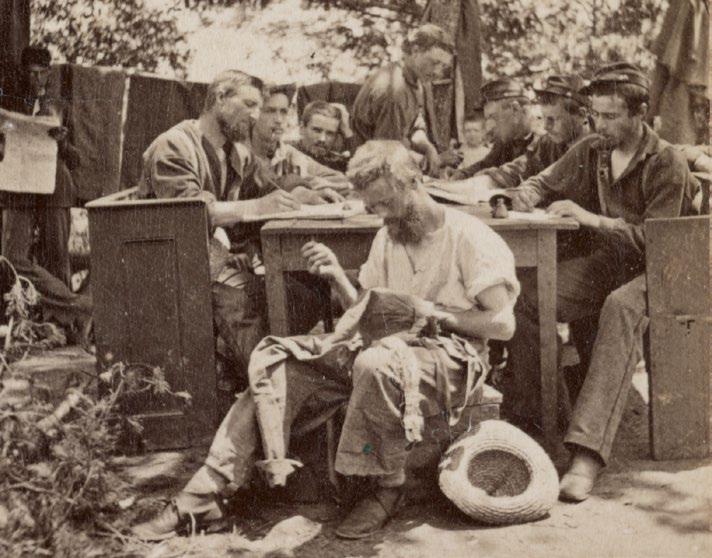

A raw recruit in the army expects to learn how to march in step and fire his rifle. However, having to learn to darn your own socks was probably not mentioned on the recruiting posters.

For many of these men (some of them no more than boys), this was their first experience away from the comforts of hearth and home. One might expect that those newly recruited soldiers who hailed from the rural farmlands of Virginia or Ohio might have an easier go at campaigning than their city-dwelling brethren. However, even a farm boy from Pennsylvania probably had little experience in sewing a patch on his trousers or cooking his own supper. These domestic skills, taken for granted at home with mothers and sisters present, had to be learned if one were to survive the rigors of campaigning.

continued on page 27

ACWM: 0985.13.1183

A “housewife” was a small sewing kit carried by many soldiers during the war to make repairs to their clothing such as replacing a button or sewing on a patch. Containing needles, thread, and extra buttons, they were rolled or folded and easily carried in a knapsack or haversack. If the regiment was lucky enough to have a tailor in their ranks, then his skills could be pressed into service to make repairs or alterations to a soldier’s clothing.

ACWM: 0985.13.883

This combination folding knife was “liberated” from a Union soldier by John Casler of the 33rd Virginia Infantry.

Boston Light Artillery soldiers in camp at Relay House in Maryland sitting at a long table writing letters, while one soldier in the foreground is sewing. ca 1861.

PHOTOGRAPHER: E. & H.T. ANTHONY

IMAGE SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

John Wilson and myself has been patching the seat of our britches this morning. John puckered his patch bad but I got mine on finely as good as a heap of women would do.Samuel Pryer, 28th North Carolina Infantry

ACWM: 1975.20.1

Tom Buck, a tailor serving in Rosser’s (Confederate) Cavalry, made this shirt out of a spread from “an old Dutchman's bed” while in camp in Pennsylvania.

continued from page 25

Napoleon (supposedly) once said that “An army marches on its stomach.” Without proper provisions, sickness increased and men left the ranks to rampage across the countryside looking for food.

According to U.S. Surgeon General William Hammond, the men in blue had the most abundant food allowance in the world. A U.S. soldier’s official daily ration was: “twelve ounces of pork or bacon, or one pound and four ounces of salt or fresh beef; one pound and six ounces of soft bread or flour, or one pound of hard bread, or one pound and four ounces of corn meal….”

Add to that a supply of beans or peas, rice or hominy, coffee or tea, sugar, salt, pepper, potatoes, vinegar, and molasses. Bakeries were set up close to the army to supply fresh bread. Dried fruit and Borden’s Condensed Milk were issued when available. The soldiers even received the occasional ration of whiskey.

Cooking meals for the soldiers was sometimes done on the company level—with a select number doing most of the cooking for everyone else. This garnered a certain amount of consistency and expertise in preparing the rations that were issued. More often than not, especially when actively campaigning, preparing meals was down to the mess (a group of four to eight men in the same company) or the individual.

Some soldiers became quite proficient at cooking. Others never got the hang of it. A group of U.S. soldiers, serving under Ulysses Grant in the west, used a confiscated coffee mill to grind up some hard corn to make a mush. One of them wrote that it filled them

up, “but with the majority it did not agree,” giving them, as he put it, the “Mississippi Quick Step,” resulting in a long line at the regimental doctor’s tent and the latrines.

Despite the official regulations, there were times when even the Union army was left wanting for food, and the men marched on empty stomachs. Part of the problem was the soldier’s lack of restraint. “We generally draw five days’ rations at one time and generally eat them up in three days and starve the other two.”

It is a soldier’s lot to grumble about food in terms of quality as well as quantity. A soldier from Illinois serving in Kentucky wrote: “The boys say that our ‘grub’ is enough to make a mule desert…Hard bread, bacon and coffee is all we draw.” These privations tended to be short lived when compared to shortages suffered by Confederate soldiers, who almost constantly lacked proper provisions.

The logistics of supplying food to an army of upwards of 100,000 men is mind boggling and the system was rife with unscrupulous officers and incompetent commissaries. When scurvy showed up among the soldiers in the Army of the Cumberland, General Rosecrans was baffled. Reports showed that 100 barrels of vegetables were daily supplied to his command, and he assumed that it was being issued to the men. In reality, one-fourth of it was being consumed by the staff officers and their families at headquarters, and, as the remainder trickled down through the division and brigade commands, there was little left for the enlisted men.

continued on next page

I dont think the Confederacy treats her troops right. She feeds us... on pickled Beef... Nasty stinking blue stuff, a dog will hardly smell it.

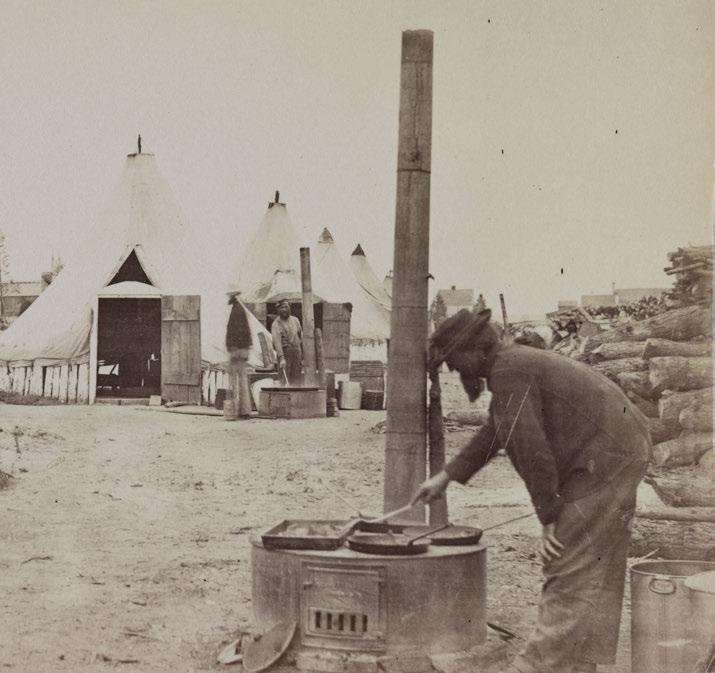

Edwin H. Fay, 18th Battalion Tennessee Cavalry(Left) African-American army cook at work at City Point, Va. during the siege of Petersburg, June 1864-April 1865. (Right) Cooks preparing food for the 153 rd New York Infantry. IMAGES SOURCE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

I have learned to cook so well that when I come home you will have to let me do all thecooking

and let “Aunty” do something else.

ACWM: 0985.15.43

A staple of every soldier’s diet was the hard biscuit or cracker commonly referred to as hardtack. Baked in their millions, these simple crackers made of flour and water were issued to the soldiers by the crate full. Also known as “teeth dullers” and “sheet-iron crackers,” the men grew heartily sick of them over time. Often infested with insects by the time they reached the soldiers in the field, the “worm castles” could be broken up and tossed into boiling soup or coffee and the offending insects skimmed from the top.

ACWM: 2009.5

Every soldier carried a tin cup which was used to dip water or boil soup or coffee.

ACWM: 0985.12.19b

Universally, the favored drink of soldiers (aside from liquor, of course) was coffee. It was brewed strong and generally taken black unless the men had been issued Borden’s condensed milk or there was a cow handy.

…[coffee] gave strength to the weary and heavy laden, and courage to the despondent and sick at heart.

F.Y. Hedley, 32nd Illinois Infantry

Scarcely any of us knew how to cook as much as a cup of coffee.

William Bircher, 2nd Minnesota Veteran Volunteer Infantry

The Return of a Federal Foraging Party into Camp near Annandale Chapel, Virginia from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. ACWM: TRE2005.006.004

The Return of a Federal Foraging Party into Camp near Annandale Chapel, Virginia from Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. ACWM: TRE2005.006.004

Chickens, geese, turkeys, hogs, and cattle were taken very freely. I tell you the country is perfectly ransacked.

JacobBartmess, 39th Indiana mounted Infantry

In times of privation, soldiers often resorted to “foraging”— begging or stealing whatever they could find around them. Then it was the civilians’ turn to go without.

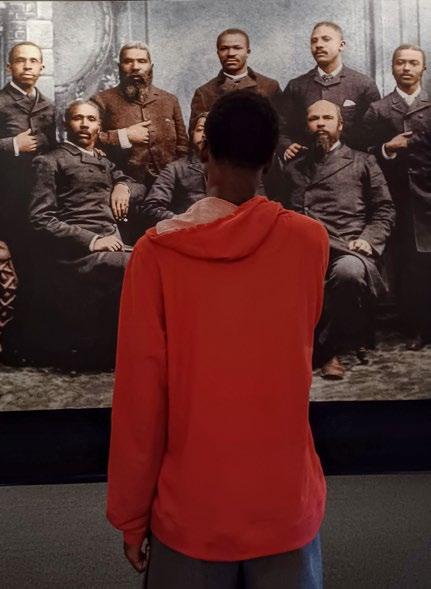

From abolition through reconstruction, the American Civil War forever altered the course of the nation. We are pleased to announce our major initiative "The Civil War & Remaking America", a multi-year look into the causes, course and consequences of the War. The launch of this initiative begins with this year’s symposium and is followed up by a spring lecture series focused on the causes of the war and the beliefs of those fighting to preserve the Union. Join us each month— March, April, and May—as noted scholars discuss their research and perspectives.

One of the longest running disputes in US History is whether the Constitution was a proslavery or an antislavery document. What can the debates surrounding the drafting and ratification of this founding document tell us, and when did the theory of antislavery constitutionalism fully emerge?

Join us for this discussion with Dr. James Oakes, Distinguished Professor of History and Graduate School Humanities Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Moderated by ACWM President and CEO, Dr. Rob Havers.

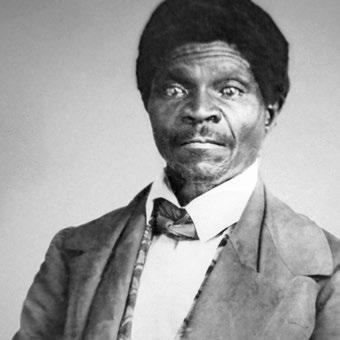

Dr. Martha Jones

Described by Senator Charles Sumner as “more thoroughly abominable than anything of the kind in the history of court,” the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sanford, is one of the most controversial of all time. Discover how this infamous Supreme Court decision impacted Black citizenship, energized the Republican Party, and moved the nation closer to Civil War.

Join us for this discussion with Dr. Martha Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor, Professor of History, and a Professor at the SNF Agora Institute at The Johns Hopkins University. Moderated by ACWM President and CEO, Dr. Rob Havers.

Although emancipation was a key outcome of the Civil War, it was devotion to the Union and the belief that the American republic was the “last best hope of earth” that sustained millions of loyal soldiers and civilians in the United States during this country’s deadliest conflict.

Join us for this discussion with Dr. Gary Gallagher, John L. Nau III Professor in the History of the American Civil War Emeritus, University of Virginia. Moderated by ACWM President and CEO, Dr. Rob Havers.

Dr. Oakes

Dr. Oakes

More thoroughly abominable than anything of the kindDr. Jones

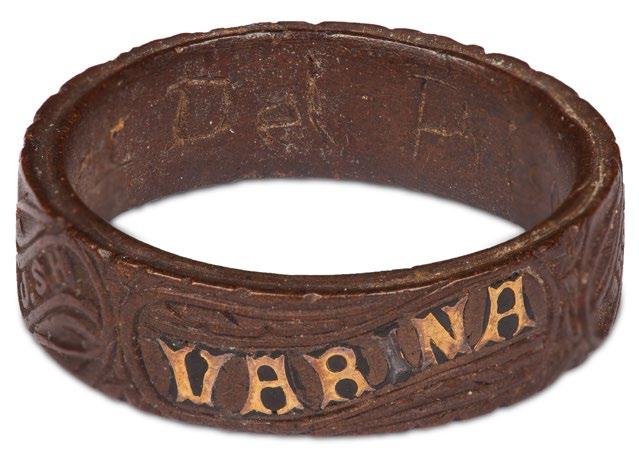

According to one wartime visitor to the White House, Emma Lyon Bryan, "The walls and mantels of her (Varina Davis, wife of President Jefferson Davis) reception room were almost covered with chains and all kinds of knick-knacks, made and presented to her by those who had been captured and imprisoned by the enemy."

This ring is believed to have been made for Varina by a Confederate prisoner of war at Fort Delaware Military Prison, based upon the interior inscription: “Ft Del Pris.”

The first fort erected on what was locally known as Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River was started around 1817. The fort occupied by Confederate prisoners during the Civil War was built between 1848 and 1860.

Enlisted men were kept in a barracks—known as the “Bull Pen'' by the inmates—that held about 10,000 men. Officers had separate quarters. Many of the soldiers captured at Gettysburg were incarcerated here. By Civil War standards, living conditions on the island were more than tolerable, the death rate from disease and other causes was approximately 7.6% of the total inmate population. This percentage includes a smallpox epidemic which hit the area in 1863, infecting prisoners and guards alike.

Gutta percha ring carved by unknown prisoner at Fort Delaware prison. ACWM: 0985.7.55

Pencil sketch of Fort Delaware by George Richwood, who was incarcerated there. ACWM: 1998.10.25

Gutta percha ring carved by unknown prisoner at Fort Delaware prison. ACWM: 0985.7.55

Pencil sketch of Fort Delaware by George Richwood, who was incarcerated there. ACWM: 1998.10.25

An Example for All the Land reveals Washington, D.C. as a laboratory for social policy in the era of emancipation and the Civil War. In this panoramic study, Kate Masur provides a nuanced account of African Americans' grassroots activism, municipal politics, and the U.S. Congress.

Paperback: 376 pages

Publisher: Univ. of North Carolina Press, October 2010

Member: $33.75, Retail: $37.50

SKU: 154920

By Kate Masur

By Kate Masur

Masur details the groundbreaking history of the movement for equal rights that courageously battled racist laws and institutions, Northern and Southern, in the decades before the Civil War. A Pulitzer Prize finalist.

Publisher: W.W Norton & Company, March 2021

Paperback: 496 pages

Member: $18.00

Retail: $20.00

SKU: 154733

By Manisha Sinha

By Manisha Sinha

Sinha documents the influence of the Haitian Revolution and the centrality of slave resistance in shaping the ideology and tactics of abolition. This book is a comprehensive new history of the abolition movement in a transnational context.

Paperback: 784 pages

Publisher: Yale University Press, February 2017

Member: $24.30, Retail: $27.00

SKU: 152992

By Manisha Sinha

By Manisha Sinha

Sinha discusses some of the major sectional crises of the antebellum era—including nullification, the conflict over the expansion of slavery into western territories, and secession—and offers an important reevaluation of the movement to reopen the African slave trade in the 1850s.

Paperback: 378 pages

Publisher: Univ. of North Carolina Press, June 2003

Member: $38.25, Retail: $42.50

SKU: 154917

By Aaron Sheehan-Dean

By Aaron Sheehan-Dean

This atlas includes data maps and covers key issues before and after the war years, balancing military and non-military coverage and presenting maps that deal with political and social changes along with campaign and battle maps.

Paperback: 144 pages

Publisher: Oxford University Press, March 2020

Member: $31.49, Retail: $34.99

SKU: 42805

By Aaron Sheehan-Dean

By Aaron Sheehan-Dean

Sheehan-Dean explores how Virginia soldiers—even those who were non-slaveholders—adapted their vision of the war's purpose to remain committed Confederates.

Paperback: 312 pages

Publisher: Univ. of North Carolina Press, Nov. 2009

Member: $33.75, Retail: $37.50

SKU: 978095

Lang shows how the intellectual, political, and social ramifications of the war and its meaning rippled through the decades that followed, not only for the America's own people but also in the ways the nation sought to redefine its place on the world stage.

Paperback: 558 pages

Publisher: Univ. of North Carolina Press, Jan. 2021

Member: $26.96, Retail: $29.95

SKU: 154918

By Andrew F. Lang

By Andrew F. Lang

In the Wake of War traces how volunteer and even professional soldiers found themselves tasked with the unprecedented project of wartime and peacetime military occupation, initiating a national debate about the changing nature of American military practice that continued into Reconstruction.

Paperback: 336 pages

Publisher: LSU Press, August 2021

Member: $27.00, Retail: $30.00

SKU: 154919

By Caroline E. Janney

By Caroline E. Janney

This volume of essays offers a fresh and nuanced view of the eastern war's closing chapter. Assessing events from the siege of Petersburg to the immediate aftermath of Lee's surrender, it blends military, social, cultural, and political history to reassess the ways in which the war ended.

Hardcover: 320 pages

Pub.: University of North Carolina Press, April 2018

Member: $31.50, Retail: $35.00

SKU: 153605

Janney takes readers from the deliberations of government and military authorities to the ground-level experiences of common soldiers. Ultimately, what unfolds is the messy birth narrative of the Lost Cause, laying the groundwork for the defiant resilience of rebellion in the years that followed.

Hardcover: 344 pages

Publisher: University of North Carolina Press, September 2021

Member: $27.00, Retail: $30.00

SKU: 154306

By Chris Mackowski, Frank J. Scaturro

By Chris Mackowski, Frank J. Scaturro

Celebrates a man whose towering impact on American history has often been overshadowed and in many cases, ignored. This collection of essays, by leading Grant scholars, offers fresh perspectives on Grant’s military career and presidency, as well as underexplored personal topics.

Hardcover: 240 pages

Publisher: Savas Beatie, May 2023

Member: $29.65, Retail: $32.95

SKU: 154921

By Christopher Alan Graham

By Christopher Alan Graham

Interrogates the legacy of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church self-identified benevolent paternalism on the racial and religious geography of Richmond, and the epilogue reflects on what an authentic process of recognition and reparations might be, drawing useful lessons.

Paperback: 232 pages

Publisher: University of Virginia Press, March 2023

Member: $26.10, Retail: $29.00

SKU: 154924