Publisher

Rob Havers , Ph.D.

ACWM President & CEO

Managing Editor

Robert Hancock

Art Director/Designer

John Dixon

Editorial Review

Ana Edwards

Kelly Hancock

Jeniffer Maloney

Museum

Board of Directors

Daniel G. Stoddard, Chair

Claude P. Foster, Vice Chair

Walter S. Robertson III, Treasurer

Mario White, Secretary

J. Gordon Beittenmiller

Hans Binnendijk, Ph.D.

Audrey P. Davis

Sally Diggs Fletcher

George C. Freeman III

Stephen T. Gannon

Hon. David C. Gompert

Bruce C. Gottwald, Sr.

Rob Havers, Ph.D.

Richard S. Johnson

Donald E. King

John L. Nau III

William R. Piper

O. Randolph Rollins

Kenneth P. Ruscio, Ph.D.

Leigh Luter Schell

Julie Sherman

Roderick G. Stanley

Ruth Streeter

Jeffrey L. Wilt

Foundation

Board of Directors

Jeffrey L. Wilt, Chair

J. Gordon Beittenmiller

David C. Gompert

Donald E. King

Walter S. Robertson III

Kenneth P. Ruscio Ph.D.

Greetings from Richmond, Virginia, and welcome to the summer edition of our quarterly publication, Ironclad. We received fulsome praise for the previous edition, with its dramatic fold out cover illustration of the well-known painting of Admiral Farragut at the naval battle of Mobile Bay, so we had some way to go to match it, but I’m confident we have done just that!

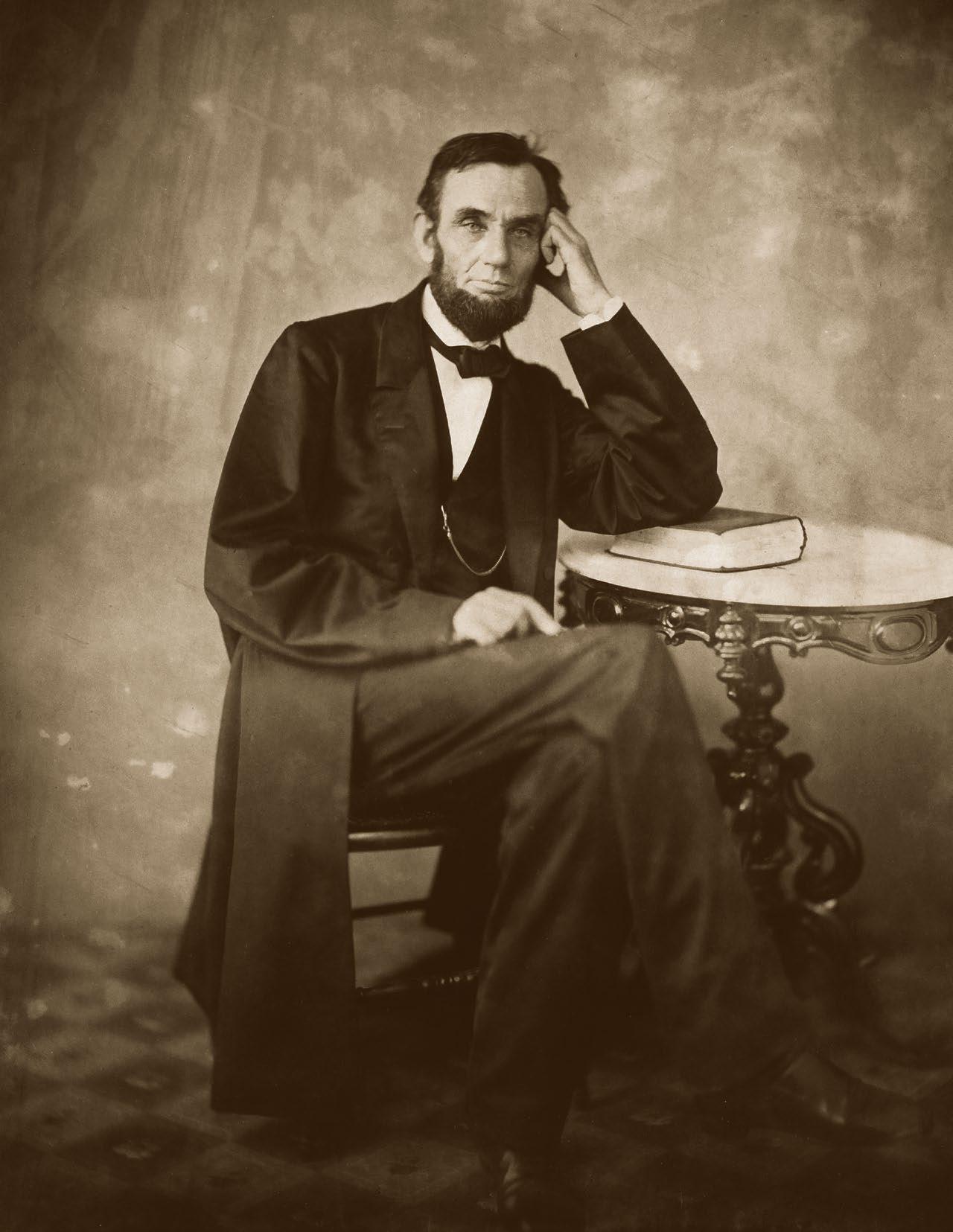

In this edition, you will find Andrew Lang’s fascinating discussion and exposition of Lincoln’s thoughts and actions on the eve of the emancipation proclamation. Professor Lang’s piece details, thoroughly, the arguments that Lincoln advanced in support of the proclamation. It shows, too, the manner in which he saw it through the prism of the entire span of U.S. history as well as the tumultuous time of civil war in which he wrote it. Lincoln is somewhat of a theme in this issue with the publication of the rare Gardner formal portrait of Lincoln from 1863.

In addition to the various articles, we also look at our activities in the midst of a busy summer. Our visitor attendance numbers, nearly 78,000 across all three of our sites, were, for us, record breaking, and we were delighted to see so many visitors at our museum sites and attending our programs in person and on-line. Interest in the Civil War remains buoyant with new generations of Americans still intrigued and fascinated by the causes, course, and consequences of arguably the most significant time in U.S. history.

Appropriately, in an issue with a Lincoln focus, I’m delighted to announce that we have set the date for our ACWM Lincoln Prize Lecture for October 26, 2023, at Tredegar. This first annual event for ACWM is a result of our new partnership with Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, an organization that has done so much for the preservation, dissemination, and teaching of American History. In particular, their support of a greater understanding of the Civil War is substantial, and their annual ‘Lincoln Prize’ award given to the finest scholarly work in English on Abraham Lincoln, the American Civil War soldier, or the American Civil War era, is one that enhances the general public's understanding of the Civil War era. The Lincoln Prize is one of, if not the, most prestigious awards in the field.

One of this year’s award winners, Dr. Jonathan White, will be in attendance with former Lincoln Prize winner and esteemed historian, Dr. Ed. Ayers. I hope you will join us for this inaugural lecture. This event is supported by the Roller Bottimore Endowment which has sustained an ACWM lecture series with a long and storied history with the Museum. On the occasion of what will be the 25th Elizabeth Roller Bottimore Lecture, we are pleased to be able to honor that tradition with a new focus on Lincoln Prize winning authors. More details coming soon!

As always, I look forward to seeing you in person in Richmond or Appomattox.

Dr. Rob Havers President & CEO

By Chuck Young and Robert Hancock

By Chuck Young and Robert Hancock

AsAshistorical interpreters, we have a compulsion (an obsession, perhaps?) to know things. We are asked a lot of questions regarding the artifacts on display, and the joy of every interpreter is that “Ah!” moment when a visitor comes to an understanding of the information that has been shared. And while we all love a mystery, it only extends as far as the research required to solve it. We don’t tend to like unanswered questions. At the American Civil War Museum, we are blessed to have a plethora of primary and secondary information available that can be crafted into compelling stories and tours to share with our visitors. One notable exception involves the large, bronze cannon that resides in the museum’s lobby at our Tredegar location; a gun with a potentially fascinating story if only one could find it.

What we do know is that the cannon tube was manufactured in 1861 by John Clark’s foundry located at the corner of Race and Tchoupitoulas Streets in New Orleans in what is today’s Lower Garden District. Before the war, Clark made “furnaces, grate bars, car axles, and cotton presses.” By the summer of 1861, he was casting cannons for independent Confederate artillery units. These were mostly six-pounder guns and twelve-pounder howitzers, similar to the U.S. Model 1841 that saw wide use during the Mexican War from 1846-48. Carriages for Clark’s guns were made locally in the shop of Peter Seibert located on Liberty Street.

During this period, cannons came in two basic types: smoothbore and rifled. The term “pounder” is normally used in reference to a smoothbore gun, which is denoted by the weight of the solid shot that it fired, such as “sixpounder” or “twelve-pounder.” Rifled guns were generally referred to by the width of the bore in inches. Here is where the nomenclature gets confusing. Clark’s guns as described in period sources use a combination of the two. Thus, a six-pounder rifle which, in this case, is the equivalent of a 3.3 inch rifled gun.

Clark’s output was small compared to the big foundries producing cannon during the war, and this is the only rifled cannon from Clark known to have survived. With such a unique piece, is it possible to track down which unit used this cannon during the war?The famed Washington Artillery of New Orleans was initially armed with a number of 6-pounder rifles; the 3rd company is listed as having one in 1861 and the 5th company as having two in 1862. In a solicitation letter dated March 11, 1862, to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard (also from Louisiana), Clark lists the Washington Artillery as being among the New Orleans artillery units who received some of his over 100 cannons that he had purportedly produced up to that point. Another unit mentioned was the Watson “Flying Artillery” who, according to the August 13, 1861, edition of the Times-Picayune, was armed with “six brass rifled guns, cast in this city, and four of which are 6-pounders and two 12-pounders.” What this tells us is that John Clark produced rifled cannon tubes, which were referred to by their smoothbore designation. This can confuse some modernday historians who see the “pounder” description and immediately conclude that the gun was a smoothbore.

Much is known about the Washington Artillery due to its prewar and wartime accomplishments. In July 1861, its first 4 companies traveled to Virginia with at least one 6-pounder rifle but, according to Charles B. Dew, in his work entitled Ironmaker to the Confederacy: Joseph R. Anderson and the Tredegar Iron Works, Tredegar “outfitted the Washington Artillery of New Orleans and the battery of Wade Hampton’s Legion with new field pieces just

prior to the Manassas engagement.” It is possible, or even probable, that the Tredegar foundry melted down the Clark-made cannons and recast them as more modern 12-pounder “Napoleon” gun-howitzers, which became the workhorse gun of the Confederate armies. If so, then our Clark cannon was not used by the Washington Artillery companies stationed in Virginia.

The 5th company of the Washington Artillery, on the other hand, was not formed until March 1862, so it did not join its sister companies in Virginia. Instead, it remained in the western theater and saw service in all the major battles including: Shiloh, Perryville, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga,

and Missionary Ridge, where the battery had to abandon all its guns. Confederate prisoners captured in the fighting around Chattanooga were transported to the newly opened prison camp at Rock Island, Illinois. The cannon barrel of our mystery gun was a gift from the U.S. Arsenal at Rock Island to the Commonwealth of Virginia in the 1930s. It was later donated to the museum. Was it a coincidence that captured Confederate soldiers from Missionary Ridge were taken to Rock Island, and that our cannon tube came from the same location?

Clearly a compelling case can be made for the 5th company of the Washington Artillery as the owners of the Clark cannon tube since it is scarred, presumably from battle damage, and “spiked” with a square nail in the vent hole, which was done when a gun had to be abandoned to the enemy, making it inoperable. An even more compelling case, though, can be made for the Watson “Flying Artillery” Battery. As mentioned above, according to the Times-Picayune, the Watson Battery was armed with six rifled guns in 1861. There is also specific documentary information pertaining to the early combat story of the unit that matches the Clark cannon barrel.

continued on next page

The Watson Battery was organized on July 1, 1861, and named for its financier, A.C. Watson, a wealthy planter of Tensas Parish, Louisiana. Following its organization, it trained for a month on the Watson plantation before traveling to the Confederate stronghold of Columbus, Kentucky, on the Mississippi River. The battery was then posted to the camp of observation opposite Columbus, on the Missouri side of the river, near Belmont. It was here that the Watson Battery received its baptism of fire on November 7, 1861, when the Confederate camp was attacked by Union forces commanded by Brigadier General U.S. Grant.

During the battle, the Watson Battery of six guns comprised the entirety of the Confederate artillery. Modern scholars state that all six guns were smoothbore since they were referred to as “pounders,” whereas the primary account provided by the TimesPicayune, refers to them as rifles. During the fighting that day, the battery ran out of ammunition and was ordered to withdraw. One of the guns was abandoned when its harness team ran off, while another gun was left behind after a Union shell exploded near one section of the battery. The book The Battle of Belmont: Grant Strikes South states that “some reports claim that a Federal artillery shell had exploded near Watson’s Battery. While the other pieces of Watson’s Artillery were withdrawn to the bank of the river, the gun fell into Federal hands. Colonel Buford’s 27th Illinois were the first to press into the Confederate line and succeeded in capturing the gun belonging to Watson’s Battery.” Battery commander Lieutenant Colonel Beltzhoover stated in his report of the battle that “My loss [was] 2 killed and 8 wounded and missing; 45 horses killed; 2 guns missing.”

A similar account is provided by Otho Klemm of Taylor’s (U.S.) Battery, the Chicago Artillery, who stated that: “The rebels had

about five hundred men and two batteries of artillery, one being the celebrated Watson L.A. of New Orleans” (the Order of Battle for Belmont lists Watson as the only battery at Belmont, but possibly split into two sections). “Two of our pieces were firing upon the guns of the enemy as fast as possible, while the other four threw a perfect hail of canister, shells, and spherical case, which must have done an awful execution, as it tore up the ranks of the infantry and killed about all the cannoneers at their guns. One fellow, we found hammer and spike in hand, ready to spike his gun.” The Clark barrel has damage that could have resulted from being fired at by the Chicago Artillery. Klemm also states “We captured two cannons” and “We drew off two of the enemy’s guns.” An account in The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant has two captured guns (one 6-pounder and one 12-pounder) being sent to the US base at Bird Point and eventually making it to Camp Holt, IN, near Louisville, KY. Three other captured guns were left behind, “smartly spiked” by their captors. As previously stated, our cannon barrel is spiked with a square nail.

There is a great deal of circumstantial evidence concerning the original ownership of our gun, but frustratingly, not quite enough to give it a positive attribution. We might imagine the men in Watson’s Artillery loading and firing as fast as they could while shot and shell rained down on them, scarring the barrel; or someone in the Washington Artillery, knowing that they would have to abandon their piece, frantically spiking the gun so the enemy could not turn it against them. Unfortunately, in the end, we will probably never know, but it’s still fun to think about.

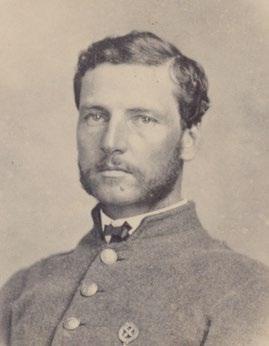

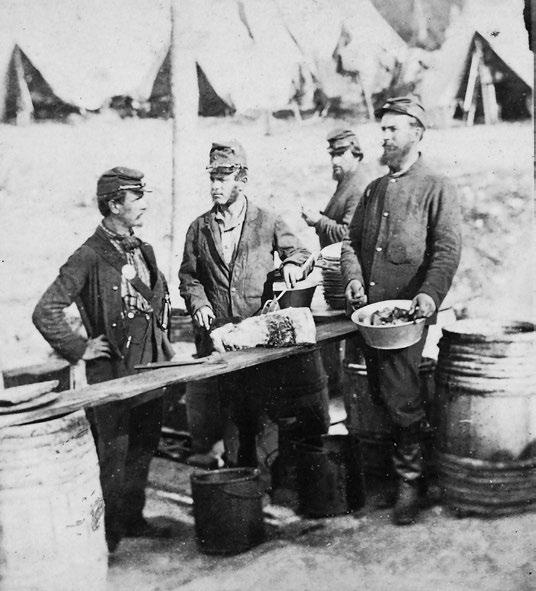

Members of the 5th Co mpany, Washington Artillery in New Orleans, c. 1862. PHOTO: WASHINGTONARTILLERY.COM

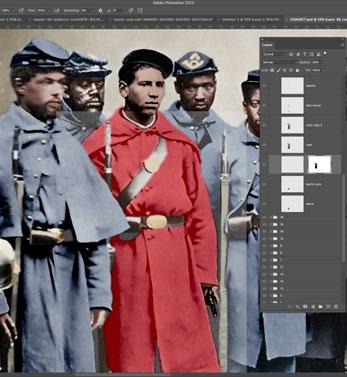

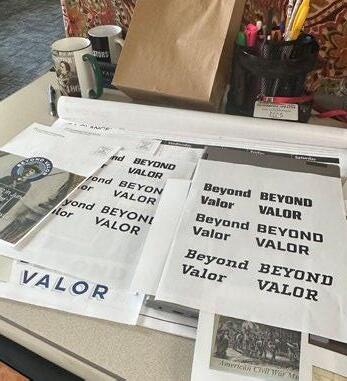

In this article, we'll uncover the fascinating story behind the collaboration between two institutions that led to the creation of the popup exhibition "Beyond Valor: United States Colored Troops & the Fight for Freedom" at ACWM–Tredegar. We'll also be discussing the curation process behind the exhibition and the journey of transforming an empty space into a platform for sharing underrepresented stories from the Civil War.

To begin the story, let me first paint a picture of a familiar experience: reconnecting with an old friend. I was attending a birthday gathering at our alma mater. In catching up with other friends, the topic of where our careers had headed arose. Normally a dreaded conversation starter for people in their mid-20s, I was pleasantly surprised when our discussion took an unexpected turn, eliciting surprise, fascination, and interestingly enough—inspiration.

continued on next page

A good friend of mine, Daniel Jones, who now serves as the Cultural Curator at Cameron Art Museum (CAM) explained that in November 2021, they had unveiled an outdoor art sculpture called “Boundless”. The sculpture commemorates the more than 1,800 United States Colored Troops who fought for two consecutive days in February 1865 on the ground where the museum now stands, ultimately leading to the fall of Wilmington, North Carolina. Artist Stephen Hayes, also from North Carolina, created a life-size bronze sculpture using the facial features of eleven African American men connected to the site, including USCT descendants, re-enactors, veterans, and community leaders. Daniel also let me know that he collaborated with Stephen Hayes to develop a tour for school groups and museum visitors and that he conducts it every Friday. To our surprise, this traditionally insignificant encounter was leading us to connect our institutions in ways we could have never imagined!

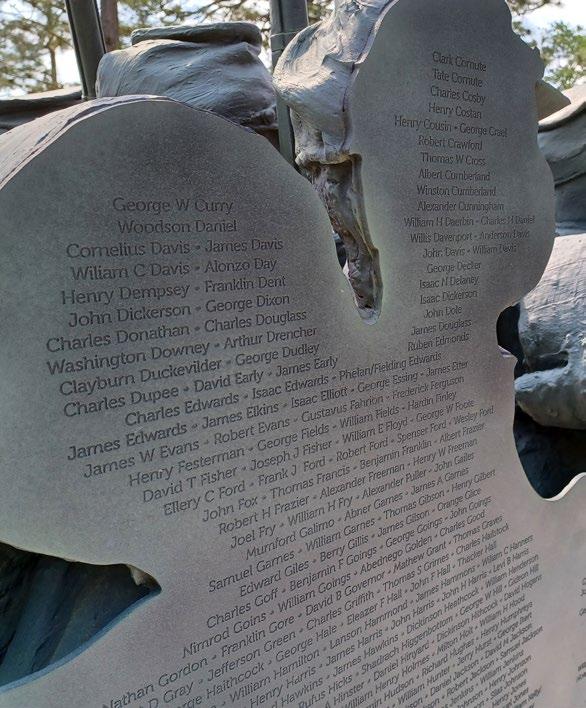

On the back of the “Boundless” sculpture are inscribed the names of the 1,820 men of the 1st , 5th, 10 th, 27th, and 37th United States Colored Troops regiments who fought in the Battle of Forks Road. These names were researched by a group of community volunteers, led by a local public historian. “Thanks to their combined research efforts,” says Heather

Wilson, Executive Director at Cameron Art Museum, “we now know that these men were as young as 12 and as old as 45 and that they came to military service as carpenters, cooks, barbers, and farmers. Some were slaves that had escaped, and some were freedmen. We also know that some were from as far away as Ohio and that some of them stayed and settled in southeastern North Carolina and Northern Virginia after the Civil War.”

According to CAM’s website, “Boundless” is the first sculpture park in the nation dedicated to honoring the United States Colored Troops. The installation required a community effort that involved excavating the land, researching military documents, and raising funds to commission the artist and install the permanent sculpture. The "Boundless" sculpture is intended to encourage people to look deeper into the lives of those who fought at the Battle of Forks Road and to preserve their stories through the oral histories of their families.

The Cameron Art Museum issued a call for the descendants of the regiments featured in "Boundless" to attend their upcoming homecoming celebration in November 2023 to honor their legacies. I was surprised by the sculpture park and "Boundless" exhibit, but I was also impressed by CAM's dedication

The Boundless sculpture was created by Stephen Hayes and installed on the Cameron Art Museum property in 2021 — where the battle of Forks Road occurred in February 1865.

continued from previous page

(Above) Daniel Jones of Cameron Art Museum with article author Aliyah Harrison.

The Boundless sculpture was created by Stephen Hayes and installed on the Cameron Art Museum property in 2021 — where the battle of Forks Road occurred in February 1865.

continued from previous page

(Above) Daniel Jones of Cameron Art Museum with article author Aliyah Harrison.

to preserving the history of the site, even though they are primarily an art-focused institution. After the night had come to a close, we exchanged contacts, and I promised to look into a way that our museum could support their message, even if it was just sharing the project.

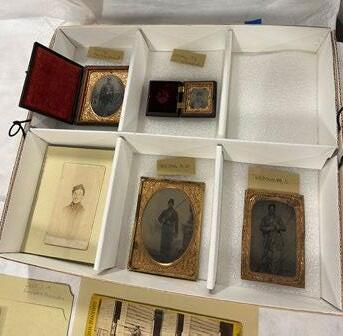

As a member of the ACWM’s Marketing team, my goal was to find ways to show our visitors the similarities between our museums. Firstly, we are both part of the Civil War Trails. Secondly, we share stories of the Civil War that are not wellknown. Lastly, our sites have significant historical value as they played a crucial role in the end of the war, showing visitors that Civil War history can be found everywhere. Afterward, I searched our PastPerfect online collection database for any artifacts related to USCT or Wilmington. Once I found some relevant pieces, I shared my discoveries with our Collections team and elaborated on my meeting with Daniel to both Lexie Hunt, our collections manager, and Robert Hancock, our senior curator and director of collections. Soon after our meeting, our teams decided that we could move forward in an even bigger direction with this project.

In order to plan our collaboration more effectively, we made the decision to travel to Wilmington, North Carolina, to

meet about the Boundless exhibit with Daniel and Heather in person. As we weren't sure what the outcome of our collaboration would be, John Dixon, the creative services manager, and Oliver Mendoza, the digital engagement coordinator in the ACWM marketing department, scheduled a trip in April 2023 to conduct interviews and create a documentary about the sculpture.

After returning from an exciting trip to Wilmington, I was eager to reconnect with our Collections team and learn about their findings on the artifacts. To my pleasant surprise, they had even better news than I had expected. Not only did we have artifacts from the Wilmington area, but we also possessed the muster rolls (official lists of men who served in the unit) of some of the regiments involved in the Battle of Forks Road. Furthermore, Robert and Lexie were so interested in the connections that this collaboration brought about, that they thought it would be a great chance to display the related artifacts in a pop-up exhibition. After conducting further research on USCT and consulting scholars such as Dr. Holly Pinheiro, Assistant Professor of African American History at Furman University, we were able to ultimately define the exhibit’s purpose. We were then able to make progress on the

continued on page 10

A detail of the the Boundless sculpture from the reverse side with 1,820 inscribed names of the United States Colored Troops who fought in the battle of Forks Road. Aliyah Harrison and Oliver Mendoza from ACWM interview and film Heather Wilson, CAM Executive Director (top) and Daniel Jones, CAM Cultural Curator (bottom).The process of developing the "Beyond Valor" pop-up exhibit required extensive planning, collaboration, and execution; from graphic design to create the logo and exhibit materials to video production for the "Boundless" documentary to interior design to plan the exhibit space to Collections research and artifact curation to the installation of the exhibit and supporting graphics.

continued from page 7 project in a more efficient manner by (1) selecting artifacts that best reflected the connection to CAM and USCTs stories, (2) editing CAM's documentary footage, (3) creating programming that highlighted the themes we wanted to showcase in the pop-up, and (4) transform an empty space that had not been utilized before.

The Collections Department selected artifacts that could be arranged in two display cases and best represented the connection to the "Boundless" sculpture. We then contacted Dr. Holly Pinheiro and Emmanuel Dabney, museum curator at Petersburg National Battlefield, to organize an event called “Unveiling the Untold: USCT & their Legacies” that highlighted the USCT soldiers and their families.

As we began the installation process, we soon discovered that all exhibits present creative and technical challenges (such as spending almost five hours applying the vinyl graphic to the window!), but we achieved our goal and are thrilled with the final results.

The pop-up exhibition has been well received thus far. Since its opening, visitors have shown immediate reactions to its powerful message. Furthermore, attendees of the "Unveiling the Untold" event received added insight into the artifacts on display and were able to gain a deeper understanding of the United States Colored Troops motivations and experience.

The collaboration between the Cameron Art Museum and the American Civil War Museum has opened the doors for future joint initiatives and ongoing partnerships that can contribute to helping preserve and illustrate our history. By sharing resources, expertise, and perspectives, institutions like CAM and the ACWM can amplify their collective efforts in creating meaningful cultural experiences. By attracting both art enthusiasts and history buffs, the exhibition sparked dialogue and added awareness to the stories and their connections to the United States Colored Troops, raising their historical importance to wider audiences.

For your next Civil War Trails road trip, we recommend visiting both the Cameron Art Museum and ACWMTredegar to explore our exhibitions that showcase the stories of the USCT. Whether you're viewing the "Boundless" art sculpture in Wilmington, NC, or "Beyond Valor: United States Colored Troops & the Fight for Freedom" at ACWMTredegar, both experiences will inspire you to reflect on the immense courage, resilience, and sacrifices of these men and their families and gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of their fight for freedom.

Aliyah Harrison is Digital Engagement Manager for ACWM.

PHOTO: RYAN KELLY, VPM NEWS

PHOTO: RYAN KELLY, VPM NEWS

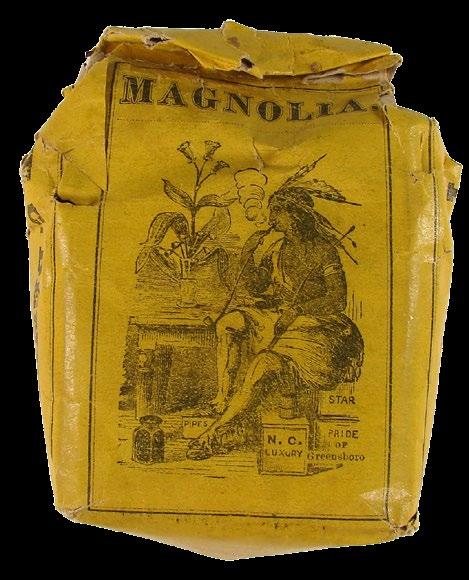

Tobacco had been commercially grown in the south since the 17th century and was still an important cash crop when the Civil War began. The southern state governments tried to curtail the growing of tobacco in favor of much needed foodstuffs, but their resolutions and laws were often ignored.

Taking tobacco, usually chewed or smoked in a pipe, was a popular pastime with soldiers during the war. Many soldiers who had never used tobacco before took up the habit in order to bond with their fellow soldiers and help wile away the dull, monotonous hours in camp and on the march. They found comfort in the “weed.” Tobacco was also used by Confederates to barter with soldiers in the Union army where southern tobacco was almost impossible to get. The opposing army camps were often quite close to one another and a lively trade, though officially frowned upon, would go on between Union and Confederate soldiers.

O the luxury of a pipe in camp! What that the muses inspire me to write a poetical essay on that subject!

Southern processed chewing tobacco. 20,000 pounds of tobacco were captured by Gilham's Brigade (US) during raids from Bulls Gap, TN, to Greenville, TN, in 1862.

W-3 L-4.5 INCHES . ACWM 0985.11.41.

This pipe bowl was carved from pear wood. Featuring the Virginia State Seal, it was made by J.W. Belote and presented to Colonel William F. Niemeyer, commander of the 61st Virginia Infantry, in 1864. Niemeyer was killed at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House on his 24th birthday.

L-3.5 INCHES. ACWM 0985.13.109

This painted ceramic pipe was found on the Malvern Hill battlefield by Pvt. Wilbur Sheldon of the 5th Michigan Infantry. It features the figure of a vivandiere, a woman (often the wife of a soldier) who followed a regiment and sold food and drink to supplement the soldiers’ rations. They could also do a bit of sewing or tend to the wounded after a battle.

W-4.25 L-10 D-1.25 INCHES. ACWM 0985.13.422.

Below are two (detail) images of Vivandieres from the Library of Congress. On the left is an unidentitfied woman. On the right is Marie (Mary) Tepe. She traveled with the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Note the similarities in dress and accuracy translated to the pipe carving.

Dr. Thomas Meams carved this pipe bowl made of ivy wood. The carving has alternating bands of incised fretwork and smooth wood. "Greenhow" is in raised letters on the base of the bowl. Meams gave it to Mary T. Johnson Greenhow [Mrs. S. C. Greenhow].

H-2.25 L-2.75 INCHES. ACWM 0985.13.656

This pipe was made from a piece of dogwood tree that was cut by a shell fired from a gunboat on the Potomac River in 1863. John F. Brooks, a first lieutenant in the 4th Texas (Hood's) Brigade, made the pipe with a pen knife. It represents a kneeling soldier wearing a prewar militia uniform.

H-6.5 W-5 L-6 INCHES. ACWM 0985.13.658

T. R. Buford carved from wood this pipe bowl and intended it to represent General “Stonewall” Jackson. Buford served in the 11th Mississippi Infantry.

Albert Simms of Sturdivant’s Artillery (CS), used this silk tobacco pouch during the war. The pouch was embroidered by his “sweetheart".

ACWM 1995.007

Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill of the 13th Virginia Infantry used this tobacco bag. It was made from red flannel wool and white silk with black velvet leaf appliques.

H-2 W-1 L-2.5 INCHES. ACWM 0985.13.1804

H-2 W-1 L-2.5 INCHES. ACWM 0985.13.1804

With over 15,000 objects, the ACWM collection of Civil War era artifacts remains our most important asset. We continue to grow our collection from donors across the country who entrust the American Civil War Museum to preserve these incredibly important elements to the story of Civil War history. Our donors have made all the difference for restoration efforts of our largest artifact, The White House of the Confederacy.

We appreciate our members and donors, whose support enables us to expand our outreach, to learn as we research and preserve artifacts, and carry out our mission to explore, inspire and promote public understanding of the Civil War.

Supporting the American Civil War Museum means access to our world-class collection, admission to our three museum sites, programming all year long at no cost, and special rates for our signature lectures and in the Museum Shop.

If you would like to discuss a donation of any sort to the Museum, or want to join or renew your membership, please contact Jake Huff, Manager of Donor Relations at jhuff@acwm.org or 804.649.1861 ext. 144

We are pleased to announce that Karen Huennekens joined the ACWM Museum staff as Director of Development and Events on August 1st Having served in the fundraising non-profit sector for the past 13 years, Karen comes to the Museum from Richmond’s historic Woman’s Club at the Bolling Haxall House. Karen holds a bachelor’s degree in Marketing from the University of Kentucky Gatton School of Business.

Tredegar

Appomattox

White House of the Confederacy

Tredegar

Appomattox

White House of the Confederacy

ACWM

The occasion was “piled high with difficulty.” In that December of 1862, civil war continued to deluge the nation in blood when President Abraham Lincoln delivered his annual message to Congress. Distressing news radiated from the warfront. A bruised and demoralized Army of the Potomac shivered in the bleak winter cold. At home, antiwar malcontents barked for peace with the rebels. The entire edifice of constitutional self-government, which Lincoln once termed “the only true sovereign of a free people,” stood on the brink of collapse.

Meanwhile, the republic inched closer to the dawn of an unprecedented social revolution. On January 1, a presidential proclamation would decree most of the nation’s bound laborers as “forever free.” Lincoln acknowledged the moment’s overwhelming gravity. Gone were the days of conciliation and compromise to bind a house divided. “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present,” Lincoln counseled. “As our case is new, so we must think anew and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country.”

Lincoln thus proposed conservative plans for gradual, compensated emancipation in the Border States. He even advanced the colonization abroad of free people of color. Above all, he implored Congress to consider a series of constitutional amendments that would over time abolish slavery from the American landscape. The very source of the nation’s violent discord had to be abolished, lest the republic perish from unrelenting turmoil. “Other means may succeed; this could not fail,” Lincoln told Congress. “The way is plain, peaceful, generous, just.” The great African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass had long encouraged this logic. “Abolish slavery and the last hinderance to a solid nationality is abolished,” he proclaimed earlier in the year. “Abolish slavery and you put an end to sectional religion and morals, and establish free speech and liberty of conscience throughout your common country. Abolish slavery and rational, law abiding Liberty will fill the whole land with peace, joy, and permanent safety now and forever.”

Ever since his reentry into politics in 1854, Lincoln believed that the moral spirit of the Declaration of Independence would inspire a self-governing people to abolish slavery gradually.

Figurine, 1865. Match safe believed to have been used by Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

Figurine, 1865. Match safe believed to have been used by Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

But his vision had been dashed with the advent of disunion and war. By 1862, Lincoln changed course. And in his December message, he put forth one of the most radical propositions ever articulated by an American president. The concluding paragraphs of Lincoln’s address read like few other presidential messages. He beseeched his fellow citizens to consider something bigger than politics, something bigger even than the destructive war inflicting the nation.

Lincoln asked the people to reflect on the process of history, a history that moved inexorably through time, compelling conscious action to unparalleled, once unthinkable forces. When he referenced “the dogmas of the quiet past,” Lincoln alluded to the Republican Party’s now obsolete pledge to protect slavery where it once legally existed. His words also conveyed a deeper, more fundamental implication. History now mandated that a free citizenry liberate themselves and their nation evermore from slavery’s suffocating embrace. No longer could the institution exist in a republic that once gave it sanction, especially now that that institution threatened to end the republic’s life. Deeds, not words, must meet history’s resolute intervention. “We must rise with the occasion” to meet “the stormy present” that few had anticipated.

And thus, “Fellow-citizens, we can not escape history.” Such an unusual statement. The premise seems self-evident. Did anyone really think they could escape history? Absolutely. Across the nineteenth century, Americans of diverse persuasions judged their nation distinct from all other human societies. And they believed their Union had transcended the course of history itself. For many, the republic shone as an exceptional beacon ordained by Providence to liberalize and modernize the world. Their nation was immune to decay. Their nation would never succumb to the plagues of global decline. Their nation was destined to march toward the sunny uplands. But disunion in the name of slavery and the civil war that it wrought shattered these once romantic assumptions.

Lincoln rejected the idea of “inevitable progress.” Nations were not impervious to the force of history. Humans could not escape history any more than they could evade their own nature. That the United States was the “last best hope of earth” meant that it could disappear. Human societies might never again renew the blessing of free government by consent. Lincoln reminded Congress that their nation confronted an eternal historical judgment: “The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation.” Atop this mystic tribunal sat God himself whom Lincoln once called “the Supreme Ruler of the nations,” a God who moved with mysterious purpose.

Lincoln thus used his annual message to communicate far more than a political agenda, propose federal budgets, or muse on military strategy. He compelled his citizens to see the Civil War—and indeed, life itself—as he had come to see it: as not merely a political crisis, but as a battle waged in an ancient conflict. The world was ordered in an endless moral struggle. History was not a random process that humans could dodge. God nevertheless furnished all humans with clues and a soul to see the right, to pursue the objective truth amid history’s jarring travails.

Lincoln understood that slavery made war on free societies and the moral conscience. The institution deceived the human heart with wicked promises of mastery and riches. “Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man’s nature,” he spoke in 1854, “opposition to it, is [in?] his love of justice. These principles are an eternal antagonism; and when brought into collision so fiercely…shocks, and throes, and convulsions must ceaselessly follow.” Here, Lincoln foreshadowed his message to Congress in 1862. History moved in unknown, unanticipated ways. Motives and intentions may once have attempted to settle the sectional crisis. Yet the currents of history had moved in directions beyond mortal control.

Might it be, Lincoln wondered, that the God of history brought a terrible civil war upon the United States to account for the people’s misplaced efforts to rid the nation of human bondage? Had a free people beckoned the Lord’s wrath by allowing the formation of a new slaveholding Confederacy that now claimed the mantle of American virtue? Perhaps, but perhaps not. After all, Lincoln would later say, “the Almighty has His own purposes.” Emancipation therefore offered “a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.”

Why must God bless a people who had long forsaken him? Because the free, white citizenry—the very people who had prolonged the crisis of slavery—now pursued a civic renewal. Necessity compelled loyal citizens to reconsider the place of emancipation in American life. “In giving freedom to the slave we assure freedom to the free—honorable alike in what we give and what we preserve.” To be sure, Lincoln spoke not of white philanthropy and black passivity. If God created all humans in his holy image, no person could ever claim earthly mastery over another. “We must think anew and act anew.” We: white northerners and southerners. We: loyal citizens and rebels. All must cure a nation that once declared but had blasphemed the universal divinity of human equality.

continued on next page

continued from previous page

All must see in the enslaved the image of God. “And then we shall save our country.”

Though as Virgil had taught in the Aeneid, spiritual battles were not easily won. “The gates of hell are open night and day; Smooth the descent, and easy is the way: But to return, and view the cheerful skies, In this the task and mighty labor lies.” For white Americans to embrace emancipation meant recovering, reaffirming, recommitting to the very history that they had long ignored but from which they could never escape. And that was the history of 1776 to which, Lincoln once said, binds with an “electric cord” “the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving [people] together.” The slaveholding Confederacy had attempted to sever this cord, championing a substitute claim to the American founding’s proposition of human equality. Failure to defeat the Confederacy’s unholy ambitions invited perpetual conflict upon the United States.

Lincoln had pondered the meaning of civil war ever since the advent of disunion in early 1861. The Confederacy signaled what he soon termed “the approach of returning despotism.” The slaveholding nation reestablished on the continent a “monarchy” that waged “war upon the first principle of popular government—the rights of the people.” Lincoln spoke of the threat posed not only to loyal citizens, but also to non-slaveholding southerners whose democratic will had been silenced by oligarchic elites. And to the enslaved, the Confederacy pledged generations of bondage, squashing any hope for liberation. Slaveholding echoed “the arguments that kings have made for enslaving people in all ages of the world.” Nobles controlled language and habits, customs and labor, consigning all their subjects to arbitrary, permanent stations. With imperial appetites, monarchies devoured the land and its resources, depriving all a fair chance in the race of life. The Confederacy aimed “to prove that control of the people” was virtuous when in fact it “is the source of all political evil.”

The prominent Confederate Presbyterian minister, James Henley Thornwell, agreed with Lincoln. Thornwell heralded his new nation’s imperial quest to slay the “godless monster” of democracy. The Confederacy meant to superintend “the progress of regulated liberty on this continent.” Slavery required unlimited growth, unchecked authority, unquestioned obedience. The Confederacy could not tolerate a free society on its northern frontier. Lincoln concurred. But the president believed that like history itself, the nation was constant.

continued on page 21

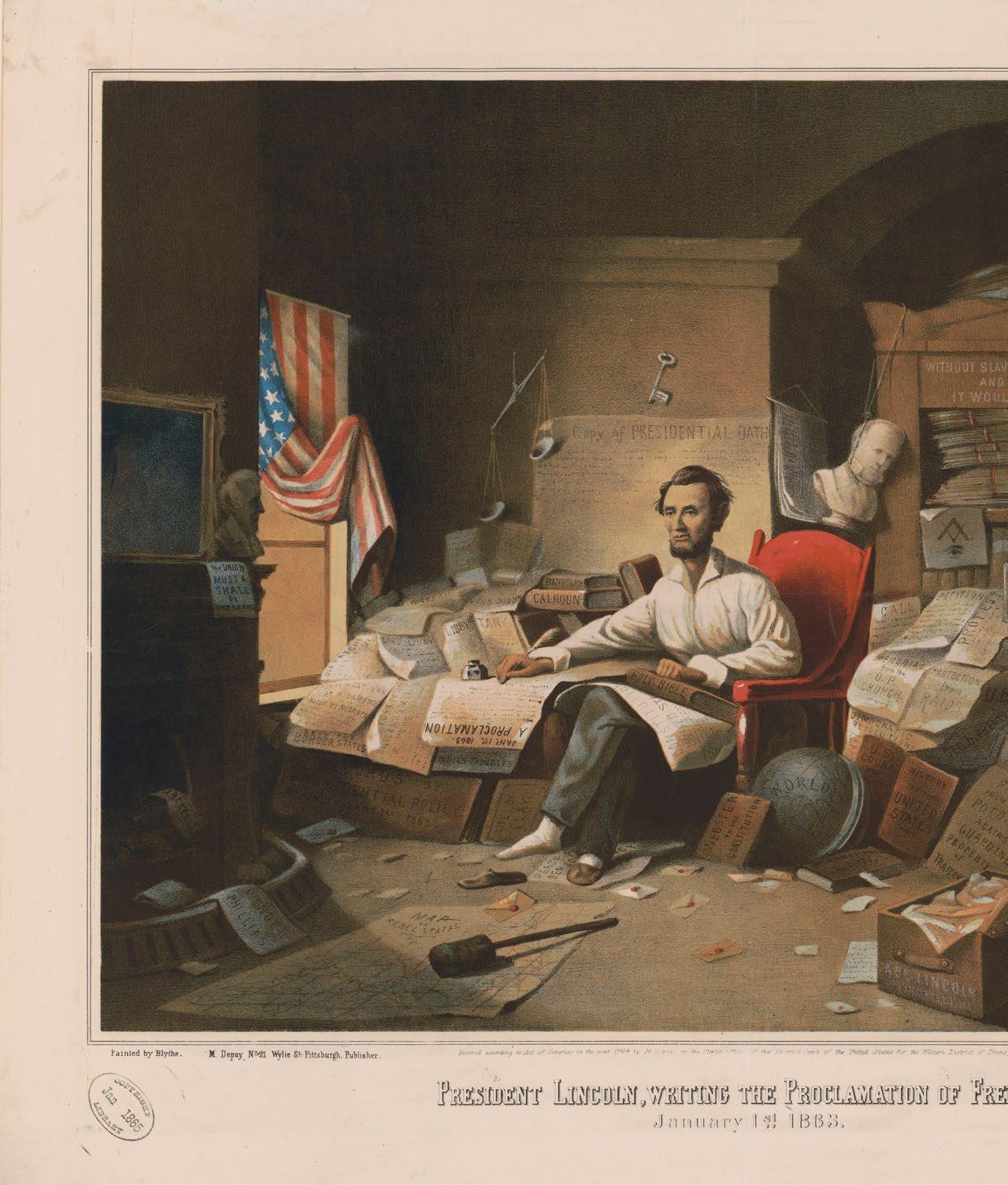

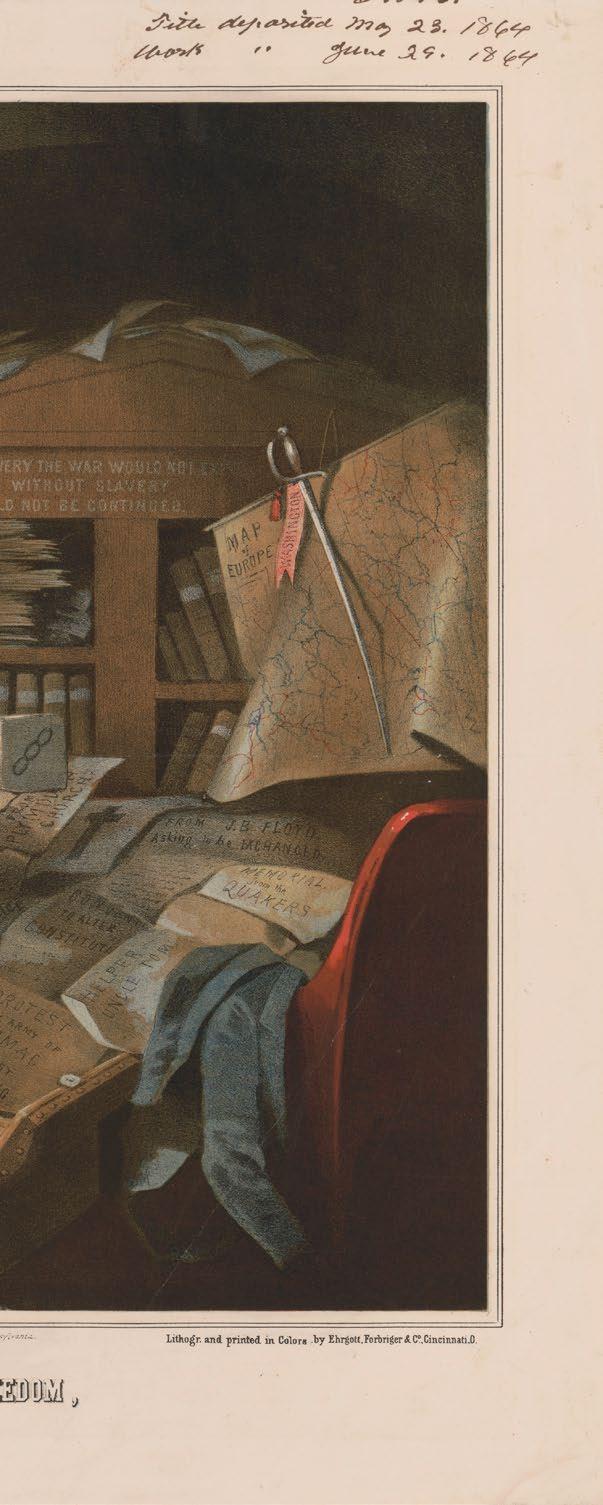

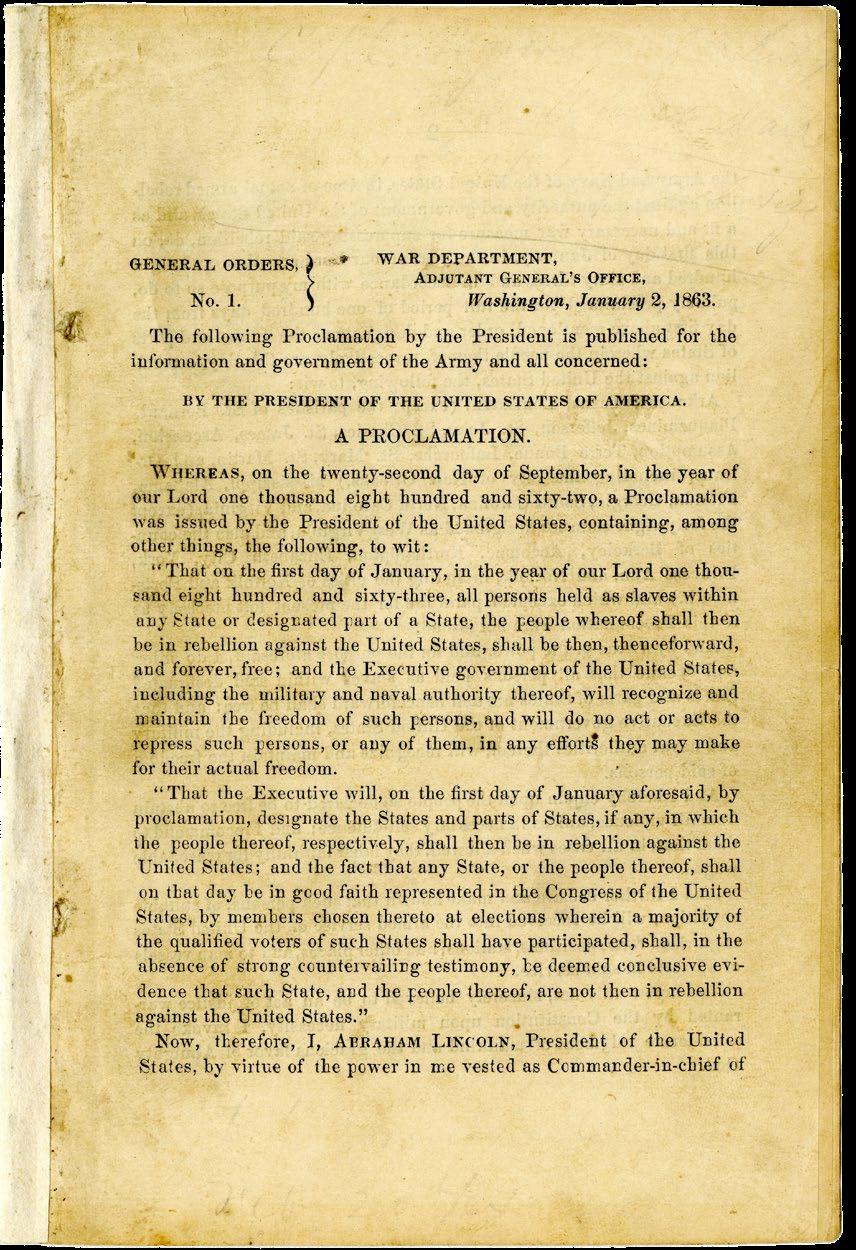

President Lincoln, writing the Proclamation of Freedom Lithograph, 1863.General Orders No. 1

A field copy of the Emancipation Proclamation used to disseminate the proclamation among Union lines in the field.

ACWM TRE2005.00.1019

Disgruntled secessionists could not so easily rearrange organic nationhood. “The territory is the only part which is of certain durability,” Lincoln countered in referencing Ecclesiastes 1: “‘One generation passeth away and another generation cometh, but the earth abideth forever.’” The American people had claimed “that portion of the earth’s surface” to organize a self-governing republic committed to individual rights and common liberty. It was “the home of one national family.” To sever this natural bond, to build two diametrically opposed societies upon the same terrestrial space, invited enduring, hostile conflict. Enmeshed in perpetual chaos and civil strife, republics melted away, replaced by strongmen who stripped the people’s liberties and ruled with iron fists.

As 1861 bled into 1862, Lincoln sensed the war assuming a spirit of its own. In September, he wondered whether human endeavors held sway when “it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party.” Might it be that God had willed slaveholders to build the Confederacy? Might it be that he willed the war to escalate? Might it be that he willed the enslaved to flee their plantations, seek refuge behind Union lines, destabilize the very institution that their Confederate overlords aimed to preserve? Might it be that God willed persistent Union military defeat? Lincoln thus questioned whether “Human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect His purpose.” But it was near impossible to discern that purpose because politics and military endeavors had failed to defeat the rebellion.

Few Americans better revealed to Lincoln the war’s possible meaning than enslaved and free people of color. In that same month of September 1862, a black New Jerseyian published in The Liberator a scathing letter to Lincoln condemning the immorality of colonization. How was the deportation of African Americans to countries abroad any less evil than enslavement itself? Both conditions deprived victims of the full rights and liberties that could be found only in the United States. “The negro, sir, was here in the infancy of the nation, he was here during its growth, and we are here to-day.” The next month, George Boyer Vashan, a black Pennsylvanian, informed Lincoln that neither politics nor even the national presence of black people had caused the war. Rather, “that cause must be sought in the wrongs inflicted upon him by the white man.” In Vashan we can almost sense the haunting melody later spoken in Lincoln’s 1865 Second Inaugural Address: “The wealth piled by the bondsman’s labor,” “the blood drawn with the lash,” the

warping of the human soul, the blasphemy inflicted on God’s creations—that is what caused the war. Vashan concluded: “Not until this nation, with hands upon its lips, and with lips in the dust shall cry repentantly, “Unclean! unclean!” will the beneficent Father of all men, of whatever color, permit its healing and purification.”

Lincoln came to agree with Vashan that the war came because of what slavery represented, how it operated, what it did to a free society. Perhaps that was why the divine force of history brought humanity’s eternal struggle to the North American continent in the middle of the nineteenth century. In his December 1862 message to Congress, Lincoln explained the uncompromising perpetuity of the nation: “That portion of the earth’s surface which is owned and inhabited by the people of the United States is well adapted to be the home of one national family, and it is not well adapted for two or more.” As Lincoln later said at Gettysburg, this was the nation, brought forth on the continent “four score and seven years ago,” “conceived in liberty,” dedicated to human equality. And it existed “under God.” The nation was of nature, of history, of divinity. It was final.

But American slavery and now the Confederacy polluted the land with the worst forms of idol worship: avarice and dominance, hatred and violence, decadence and manipulation. To use the land in defiance of history, in insolence of God, tested the nation’s viability to live. The institution had long splintered the republic and arrayed all its people in perpetual conflict. Slavery fostered competing claims to truth, obscured any sense of common morality, authored irreconcilable histories. Above all, human bondage dehumanized its victims, champions, apologists, and agnostics.

In Lincoln’s telling, the Civil War came as moment for all Americans complicit in slavery to combat the very institution that threatened the nation’s life. The president used his 1862 message to Congress—and indeed the American Civil War itself—to warn against “inevitable progress,” national destiny, and democratic complacency. It would be eleven months until he spoke at Gettysburg and two-and-a-half years until he delivered his Second Inaugural. But by December 1862, he had already crystalized in his mind the meaning of “a new birth of freedom.”

Andrew F. Lang, associate professor of history at Mississippi State University, is the author of A Contest of Civilizations: Exposing the Crisis of American Exceptionalism in the Civil War Era (2021), a finalist for the Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize.Recently, the museum acquired a small pocket diary owned by James P. Hancock, who served with the 126th Illinois Volunteer Infantry.

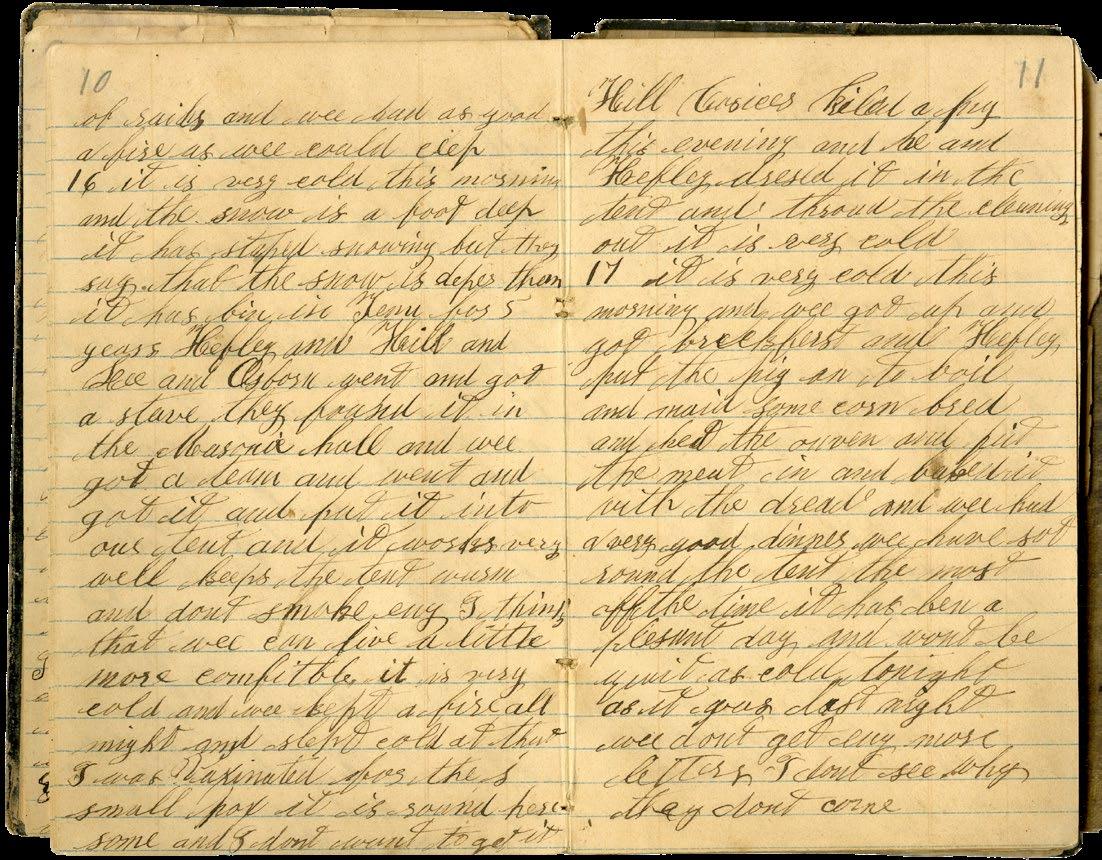

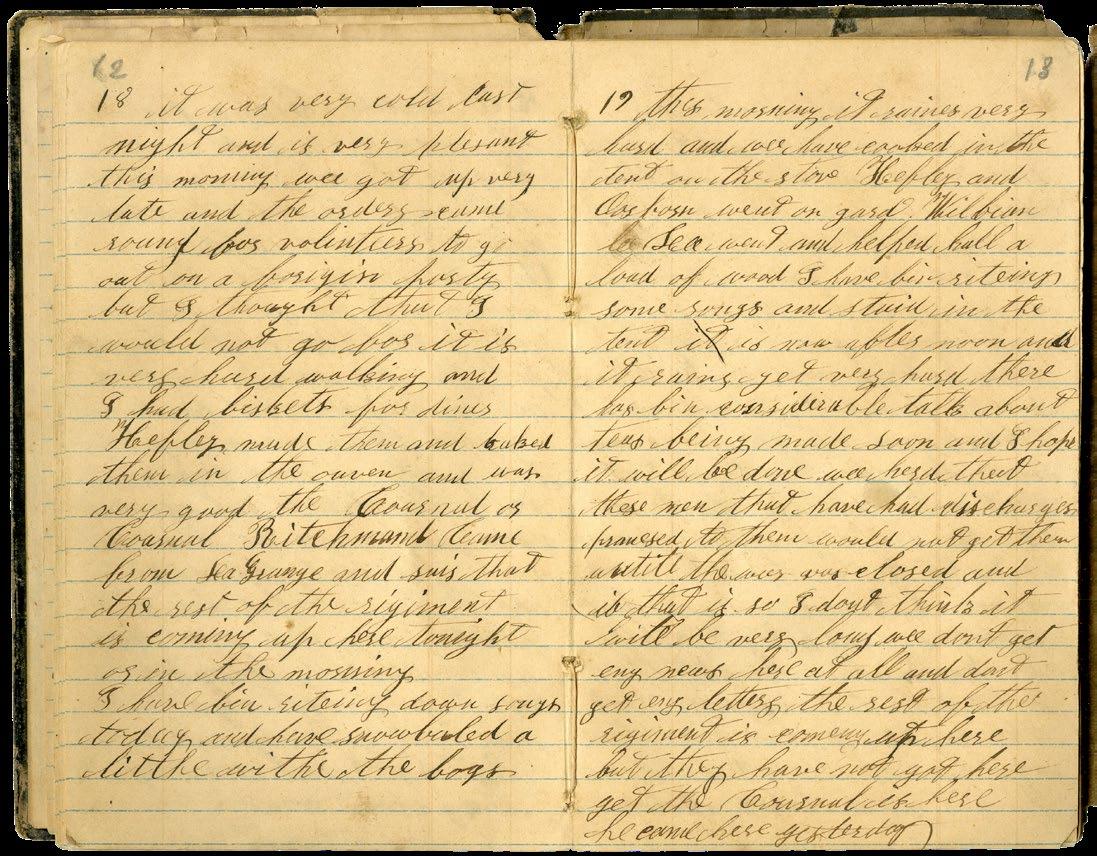

Transcribing a 19 th century diary can offer a number of challenges. First, there is the literacy of the writer to consider. At the time of the Civil War, approximately one soldier in six was illiterate. James Hancock had received at least a basic education. He relies heavily on phonetic spelling. He is also inconsistent. For instance, “pleasant” is spelled either “plesant” or “plesent.” Other spellings are more creative, such as “cournal” for colonel, and “tords” for towards.

The next hurdle to transcribing a diary, and the one that gives people the most trouble, is the penmanship. In Hancock’s case, he was not a careful writer, thus most of his vowels

are almost indistinguishable, his “r” looks like an “s,” and vice versa, and, to top it off, he uses no punctuation. Like breaking a cypher, eventually one finds patterns in the writing, and once a word is figured out (through context and a lot of squinting), the transcriber will hopefully recognize the same word later on without undue trouble.

The final challenge is the use of archaic words and phrases. In the use of military parlance, Hancock manages to spell most of them wrong, such as “forigin” for foraging and “gard” for guard. As with ‘cournal”, military ranks are spelled more or less phonetically: “corpral” (corporal), “lewtenent” (lieutenant), etc. Regiment is spelled either “rigiment” or simply “rig.”

Before the task of transcribing commenced, the diary was scanned at high resolution. Scanning the diary means that it

does not have to be handled during the transcription process, thus preventing additional wear and tear to an already fragile object. However, modern technology does little to improve bad spelling and lazy penmanship.

Hancock’s diary offers no great revelations, no romantic descriptions of battle or philosophical musings. In fact, during his short stint in the army, he never saw combat nor fired his rifle at the enemy. What he did write about were those things that most concerned a soldier: namely food and news from home. A number of fellow soldiers are mentioned in the diary and have been identified where possible. Jake and Will are the two who show up most often. Unfortunately, there were three Jacobs in his company and no less than eight Williams.

James P. Hancock enlisted in the 126th Illinois Infantry in September 1862. His small pocket diary, measuring about 6 inches by 4 inches, begins January 1, 1863. He wrote in it every day without fail. At that time, the 126th was stationed in and around Jackson and Humboldt, Tennessee, guarding the railroads that kept the Union army in the area supplied. Confederates under General Nathan Bedford Forrest were a constant threat, raiding Union supply lines and destroying railroads.

Following are selected excerpts from the diary. For the quoted passages, spelling and grammar have been retained from the original manuscript (with the occasional parenthetical translation or added information). In the original, no punctuation was used, so periods and capital letters have been added for clarity.

continued on next page

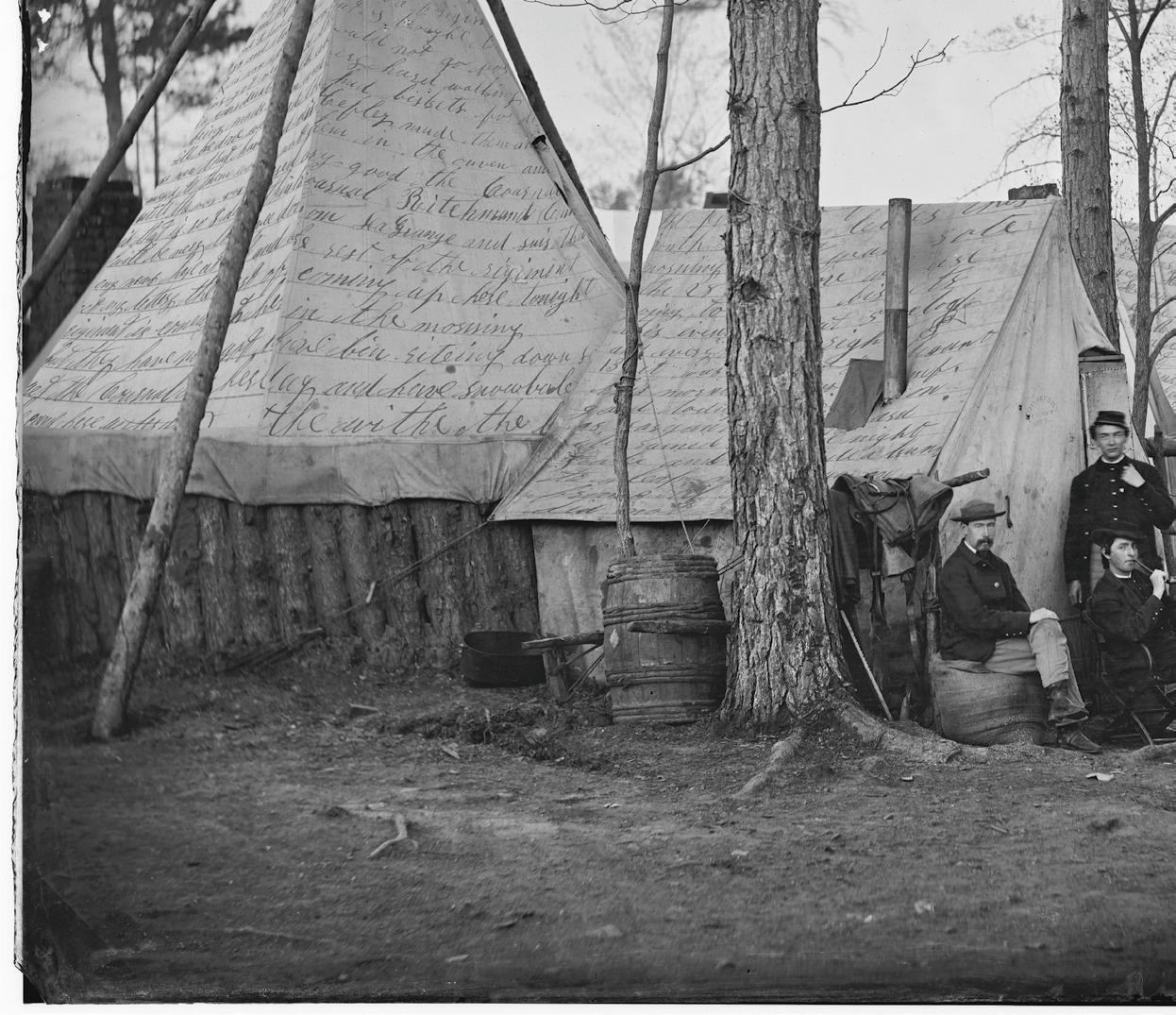

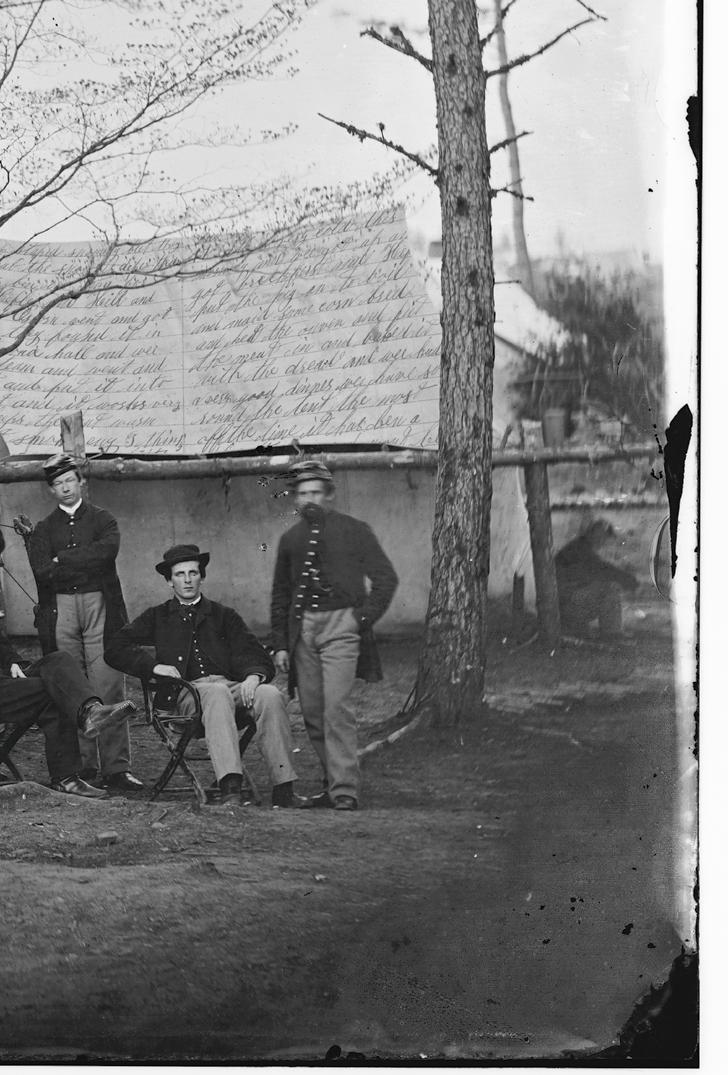

Measuring 6 inches by 4 inches, this image of Hancock's diary is shown at actual size. IMAGE: ACWM Photo Illustration by John Dixon/ACWM. Original image: Provost marshal clerks at the Army of the Potomac headquarters at Brandy Station, VA, December 1863-April 1864. IMAGE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESScontinued from previous page

James P. Hancock 126 Rig. Ill VolJan 1, 1863

I left Jackson for La Grainge went about 5 miles and came to a culvit (culvert or small bridge) that was burned and had to stay and fix it…I got to La Grange that night.

2th (2nd) day it is plesant here this morning. I am at La Grainge and staid here today and at night H. Curricer and I went down to Leut Wetmore tent and plaid ueker that evening and had a good time.

The H. Curricer mentioned is probably Hilliard L. Carriker from Irving, Illinois, who joined the regiment at the same time as Hancock. Lieutenant John J. Wetmore mustered in September 1862, and served with the regiment until January 1864. Euchre (spelled “ueker” by Hancock) was a popular, trick-taking card game usually with four players in teams of two. Hancock, as suggested by other entries in his diary and without bragging, was apparently quite good at it.

The army had small garrisons scattered all over Tennessee and part of the 126th remained in Jackson. Hancock was sometimes sent with a small detail from La Grange back to Jackson, presumably on company business.

This morning went to the junction in a wagon...we went to Jackson in 2 ours and 10 minits the distance 52 mils. Will went up with me. There was a fight east of Jackson the 31 Dec (Battle of Parker’s Crossroads) and Gen Sulivan (Jerimiah C. Sullivan) forses whiped Forrests forses and took 500 pr (prisoners) and 6 peases of artilery and 400 horses and the next day they had another fight and took 300 more pr and 4 more guns and that was all the guns they had. [The] wether is very warm here. It is warming enuf here to go in our shirt sleeves.

Hancock found his time in Jackson “very plesent.” His only complaint was that they were put on half rations. However, he and some of his buddies decided to take matters into their own hands with an unsanctioned foraging expedition.

I went out into the country with five other men and got our dinner and got to (two) geass, and to hams and six squrrils and some sausige and braut it into camp…we had a good time eating our hams and sausige and ribs. We had a grate time…getting through the swamp by the picket gard.

The next day, they continued their feast, then were ordered to go to Humboldt, an important junction of two railroads, just north of Jackson. They took the train and rode atop the railroad cars, getting to Humboldt that night. It started to rain, and they were able to secure a house near the station, where

“the old chimley caut fire but wee put it out.” Later, the rest of the company joined them, bringing their tents and other supplies. They then commenced setting up winter quarters and making themselves as comfortable as possible.

Hefley (Daniel Hefley) and I went and began to make a oven to bake bread in and they woudent let us have a team (mules and a wagon) to haul bricks and wee shal have to put it of[f] till tomorrow. Jake and Will are in the tent with us now. It is very warm here today and plesant. Wee are getting along. I am as fat as a hog.

They continued to work on their brick oven and made a table for their quarters. They drew their ration of flour so Daniel Hefley could make “biskests” for dinner. The weather turned colder with intermittent rain.

[Jan] 14 It rains very hard here this morning and I am in the tent and it don’t leak eny. It rained very hard all day and wee kept fir[e] in the tent and it smoked very bad all day and all night and Will and [Carriker] went and tried to find a stove but did not find eny and we laid down and covered our heds and went to sleep.

15 It is very cold this morning and the snow is almost 8 inches deep and is snowing all day. The tent is smoking very bad today and the boys are all finding fault with the way that the war is carried on and I think that they have good reason for it. For it looks as though they arnt trying very hard to stop this war.

"Preparing the Mess". Union soldiers preparing the camp meal on a makeshift table. The photograph is attributed to Mathew Brady. IMAGE: LIBRARY OF CONGRESSHancock's journal entries for Janurary 16 and 17, 1864 detail camp life, including snowfall, staying warm, getting vaccinated for smallpox, and the food they ate. IMAGE: ACWM

16 It is very cold this morning and the snow is a foot deep…Hefley and Will and Lee and Osborn (James Osborne) went and got a stove. They found it in the Masonic Hall and wee got a team and went and got it and put it into our tent and it works very well. Keeps the tent warm and don’t smoke eny. I think that wee can live a little more comfitble. It is very cold and wee kept a fire all night and slept cold at that. I was vaxinated for the small pox. It is around here some and I don’t want to get it.

17 It is very cold this morning and wee got up and got breckferst and Hefley put the pig (killed the day before) on to boil and maid some corn bred and [?] the oven and put the meat in and baked it…Wee had a very good dinner…We don’t get eny more letters. I don’t see why they don’t come.

18… Cournal Ritchmond (Colonel Jonathan Richmond, the regiment’s commander until March 1864) came from La Grange and sais that the rest of the rigiment is coming up here tonight or in the morning. I have snowbaled (had a snowball fight) a little with the boys.

19 This morning it rains very hard and wee have cooked in the tent on the stove. Hefley and Osborn went of[f] gard. William Lee went and helped hall a load of wood. I have bin riteing some songs and staid in the tent. It is now after noon and it rains yet very hard. There has bin considerable talk about peas (peace) being made soon and I hope it will be done.

20 it was rather cloudey this morning. Jake and I washed our drawers and shirts and then lay round in the tent the rest of the day… In the evening wee had a great game of eucer. Hefley and Leu Easterday (Lieutenant Martin V. Easterday) and Will and I plaid untill 11 oclock. Some of the boys made some fus about it but it did not make eny ods to us.

Apparently, those euchre games could get pretty raucous!

Hancock's journal entries for Janurary 18-20, 1864 continue to comment on the weather but highlight a snowball fight, list domestic chores, and entertainment with songs and card games. IMAGE: ACWM

Hancock continued to write home, though he received no letters in return. He went on guard duty, and he and his mess mates cooked on their tent stove—boiled meat and dumplings, fritters, and, of course, Hefley’s famous “biskets.”

The month of February found them snug in camp with very little to do except the occasional drill and picket duty.

[Feb.] 9 This morning I came of[f] gard this morning. It looked like rain this morning but did not rain. I was not very well today. My back hert rether bad and I did not eat much. I got a letter from Julia today. Was very glad to heer from her and the little children.

Julia was James’ wife who lived in Hillsboro, Illinois, with their three children, Henry, Joseph, and Amy, all under the age of six. Hancock wrote often of her letters and always looked forward to their arrival.

As winter turned to spring, the weather continued to improve, and Hancock mentions going into town to have his boots repegged, visiting the sutlers to buy paper and ink, and, of course, every time they had fresh “biskets,” it was worthy of mention. The war, for the most part, seemed to be going on somewhere else, for there was very little news to tell. They spent their free hours lounging in their tent, listening to the rain, and beating the lieutenants at cards. They might not have been at it tooth and nail with the enemy, but death, in the form of disease, still made the occasional visit to the company.

[Feb] 26 …I and some of the other boys went to day [to] a graive for John Cooper who died yesterday. It rained when the company went out to bery him. I did not go.

[March] 4…Will went to the hospital. I went over and carred his blankets and napsack over to him.

April 1 This morning we cam of[f] gard. I was sick. I got a bad cold and had the headake and was sick.

2…I went to the Surgan (surgeon) for some medisen and got an excuse from drill.

3…I was quite sick all day. I was looking for a letter but did not get eny.

4…I got a letter from my Dear Wife and it revived me up very much

The 126th was preparing to make their way to Vicksburg to join the siege of that place. Hancock continued writing in his diary, though the entries were getting shorter.

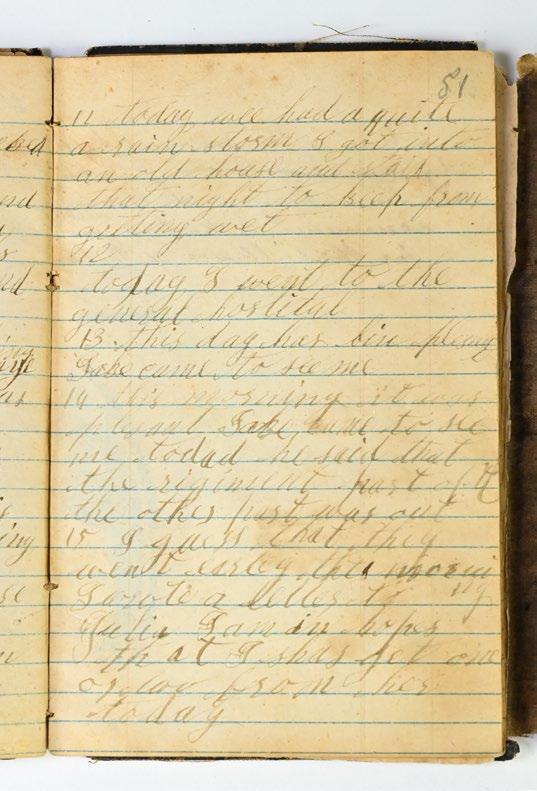

As Hancock's health declined, his diary entries were shorter. Pictured above is the last page of entries dated April 12-15, 1864. He died a short time later.

IMAGE: ACWM

[April]12 Today I went to the general hos[p]ital.

13 This day has bin plesent. Jake came to see me.

14 This morning it was plesent. Jake came to see me today.

15 I guess they (the regiment) went early this morning. I rote a letter to Julia. I am in hopes that I shall get one or two from her today.

Here the diary ends. We will never know if James received the much anticipated letters from his wife. A short time after his last entry, he died from pneumonia. His wife, Julia, applied for and received a widow’s pension from the government. She never remarried. She died on January 3, 1900.

Robert Hancock (no relation to the diarist) is the museum’s Director of Collections and Senior Curator.

Written from a perspective unique in the literature of the Civil War, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp not only chronicles daily life on the battlefront but also records interactions between blacks and whites, men and women, and Northerners and Southerners during and after the war.Taylor tells of being born into slavery and of learning, in secret, to read and write.

Paperback: 136 pages

Member: $19.76; Retail: $21.95 SKU: 2649

Publisher: University of Georgia Press; Reprint (April 2006)

Mid-nineteenth-century Americans considered their nation an unprecedented experiment in political moderation and constitutional democracy. But as abolitionism in England, economic unrest in Europe, and upheaval in the Caribbean and Latin America began to influence domestic affairs, the foundational ideas of national identity also faced new questions.

Paperback: 568 pages

Member: $26.96; Retail: $29.95 SKU: 154918

Publisher: Univ. of North Carolina Press (January 2021)

In the Wake of War traces how volunteer and even professional soldiers found themselves tasked with the unprecedented project of wartime and peacetime military occupation, initiating a national debate about the changing nature of American military practice that continued into Reconstruction.

Paperback: 366 pages Member: $27.00; Retail: $30.00 SKU: 154919

Publisher: LSU Press; Illustrated edition (December 2017)

A hardcover copy of the draft, preliminary, and final versions of Abraham Lincoln's January 1, 1863 Executive Order―the Emancipation Proclamation―which declared the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's slaves.

Hardcover: 28 pages

Member: $11.66; Retail: $12.95 SKU: 123

Publisher: Applewood Books; Reprint edition (February 1998))

In The Families’ Civil War, Holly A. Pinheiro Jr. provides a compelling account of the lives of USCT soldiers and their entire families but also argues that the Civil War was but one engagement in a longer war for racial justice. By 1863 the Civil War provided African American Philadelphians with the ability to expand the theater of war beyond their metropolitan and racially oppressive city into the South to defeat Confederates and end slavery as armed combatants. But the war at home waged by white northerners never ended.Pinheiro examines the intersections of gender, race, class, and region to fully illuminate the experiences of northern USCT soldiers and their families.

Paperback: 242 pages

Member: $24.26; Retail: $26.95

SKU: 155172

Publisher: University of Georgia Press (June 2022)

For Their Own Cause is the first comprehensive history of the 27th USCT. By including rich details culled from private letters and pension files, Mezurek provides more than a typical regimental study; she demonstrates that the lives of the men of the 27th USCT help to explain why in the wars that followed that blacks in the United States continued to offer their martial support in the front lines and the back.

Paperback: 368 pages Member: $34.16; Retail: $37.95

Publisher: The Kent State University Press (October 2016)

In a few hours of fighting, African-American soldiers struck a blow against the Army of Northern Virginia and proved to detractors that they could fight for freedom for themselves and their enslaved brethren. With vivid firsthand accounts and meticulous tactical detail, James S. Price brings The Battle of New Market Heights into brilliant focus with maps by master cartographer Steven Stanley.

SKU: 153395

Paperback: 128 pages

Member: $18.00; Retail: $19.99 SKU: 152602

Publisher: The History Press; Illustrated edition (September 2011)

The American Civil War Museum

presents the pop-up exhibit

United States Colored Troops and the Fight for Freedom