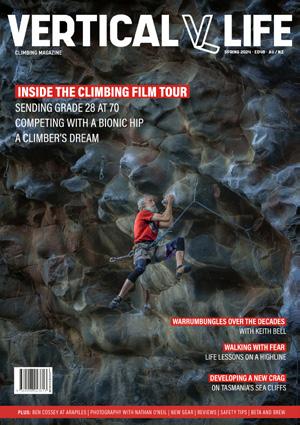

INSIDE THE CLIMBING FILM TOUR

SENDING GRADE 28 AT 70 COMPETING WITH A BIONIC HIP A CLIMBER’S DREAM

WALKING WITH FEAR . LIFE LESSONS ON A HIGHLINE WARRUMBUNGLES OVER THE DECADES. WITH KEITH BELL

DEVELOPING A NEW CRAG. ON TASMANIA’S SEA CLIFFS

SENDING GRADE 28 AT 70 COMPETING WITH A BIONIC HIP A CLIMBER’S DREAM

WALKING WITH FEAR . LIFE LESSONS ON A HIGHLINE WARRUMBUNGLES OVER THE DECADES. WITH KEITH BELL

DEVELOPING A NEW CRAG. ON TASMANIA’S SEA CLIFFS

OBSESSIVELY DESIGNED SHOES FOR PERFORMANCE IN THE VERTICAL WORLD

VERTICAL LIFE IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY WINTER/ SPRING /SUMMER/AUTUMN/ AUSTRALIAN MADE. AUSTRALIAN PRINTED. AUSTRALIAN OWNED.

EDITORS

Editor: Wendy Bruere

Gear and coffee editor: Sule McCraies wendy@verticallifemag.com

DESIGN

Marine Raynard

marine@adventureentertainment.com

ADVERTISING

Pip Casey

Email: Pip@adventureentertainment.com

Phone: +61 448 484 566

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Kate Baecher, Dave Barnes, Keith Bell, Wendy Bruere, Daniel Butler, Ben Cossey, Keith Lockwood, Sule McCraies, Nathan McNeil, Elise Marcianti, Allie Pepper, Claire Williams.

PHOTOGRAPHY

Keith Bell, Michael Blowers, Simon Carter, Nick Hancock, Victor Hall, Caitlin Horan, Molly Johnson, Brecon Littleford, Victoria Kohner-Flanagan, Tim Macartney-Snape, Sule McCraies, Christian McEwen, Nathan McNeil, Anna Pearson, Allie Pepper, Matt Raimondo, Peter Rowed, Claire Williams.

CREDITS IMAGE

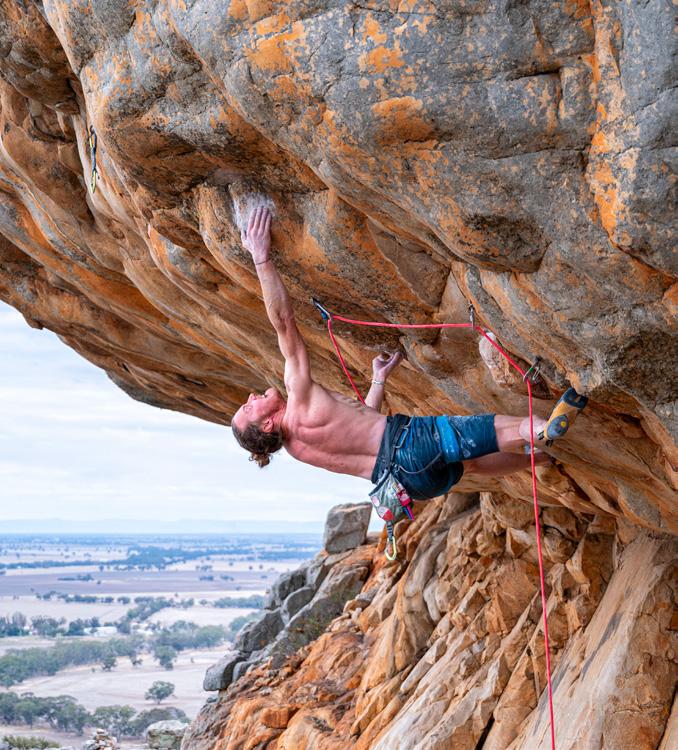

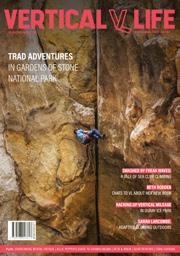

A still from Inside Out, produced by Christian McEwen, and set to feature in this year’s Climbing Film Tour.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT IMAGE

An eagle soars past a climber in Warrumbungles National Park. Image by Caitlin Horan.

PUBLISHER

Toby Ryston-Pratt

Founder & CEO

Adventure Entertainment. ABN: 79 612 294 569

SUBSCRIPTIONS

subscribe.verticallifemag.com.au E magazines@adventureentertainment.com P: 02 8227 6486 PO Box 161, Hornsby, NSW, 1630

COPYRIGHT

The content in this magazine is the intellectual property of Adventure Entertainment Pty Ltd. It must not be copied or reproduced without the permission of the publisher.

DISCLAIMER

Rock climbing and other activities described in this magazine can carry significant risk of injury or death. Undertake outdoor activity only with proper instruction, supervision, equipment and training. The publisher and its servants and agents have taken all reasonable care to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication and the expertise of its writers. Any reader attempting any of the activities described in this publication does so at their own risk. The publisher nor its servants or agents will be held liable for any loss, injury or damage resulting from any attempt to perform any of the activities described in this publication. All descriptive and visual directions are a general guide only and not to be used as a sole source of information. Climb safe

12. Editor’s Note

14. Read Watch Listen

16. Getting to know: Jason Whiter

28. How I Got the Shot: Nathan O’Neil

58. Updates from Altitude

70. Gallery

32. The Climbing Film Tour returns

42. Walking with fear

48. Traipsing Through Trachyte Towers To Tonduron

54. Sean Myles Project / Light Weight Baby

20. Local Lore: Genesis, Tasmania

62. Mindset Reset

66. Tale of Whoa

76. Field Tested

78. New Gear

81. Beta & Brew

Vertical Life acknowledges that we live, work, recreate and climb on stolen land, and that sovereignty was never ceded.

We acknowledge the Traditional Custodians across Australia and Aotearoa, and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We recognise the continuing connection of all First Nations peoples to Country and Culture across all lands and waterways since time immemorial, and reaffirm our commitment to reflection, reconciliation and solidarity.

Issue #48 of Vertical life was printed on Wangal Country.

The Olympic climbers were headed to the finals as we put the finishing touches on this issue. In fact, in a multitasking success story I managed to knock off some major edits while shrieking in excitement through the first round of bouldering.

The idea of climbing featuring in the Olympics is unlikely to have ever crossed the minds of older climbers back in the day when it was a dangerous, somewhat rebellious, pursuit. Whereas newer climbers might have started at the gym post-2021, when climbing was already an Olympic sport broadcast to an audience of millions.

Climbing can feel like a fast-evolving sport. I mean, who had even heard of speed climbing four years ago? I sure hadn’t, but gosh it was exciting to watch live as records were broken, then broken again!

Even in my 12 short years climbing, I’ve seen changes… Climbing gyms seem to have more of a gender balance for a start. There’s more of them too—new bouldering gyms are springing up like chalky mushrooms. This means there’s more climbers whose focus is gym climbing—rather than use the gyms to train for real rock routes, pulling on plastic is a growing sport in itself. There’s still plenty more people heading outdoors too. As a result of this, it seems awareness is growing around negotiating access to crags appropriately and consulting with traditional owners, especially before bolting new areas. (Head to page 20 to read more about how Dave Barnes approached this when he wanted to develop a new crag.)

I’ve also seen changes in myself through my years climbing. They happen gradually, but one day you suddenly realise real development has occurred. A few weeks ago, chatting about multipitches with a new gym climber, I explained the concept of the hanging belay to him. “I want nothing to do with that!” he exclaimed, a look of horror crossing his face.

WHEN I FIRST WENT TO A CLIMBING GYM I GOT SCARED OF HEIGHTS TOP-ROPING A GRADE 14… WHO WOULD HAVE THOUGHT THAT 11 YEARS LATER I’D BE TIPTOEING ALONG THE AIGUILLES D’ENTREVES TRAVERSE AT 3600M ON THE ITALIAN-FRENCH BORDER? DEFINITELY NOT ME.

Eleven-and-a-half-years ago I would have had the exact same sentiment; these days a hanging belay feels perfectly natural and secure. It’s not just because I’ve learnt some technical skills and gotten used to heights though. Along the way, I’ve learnt to manage fear, assess risk, make judgements about who to trust as a climbing partner—all skills that flow into life off the wall as well.

So, I guess what I’m trying to say is that our sport evolves and we evolve through our participation in it. This is something that is reflected across the stories in our spring edition. Keith Bell takes us through climbing history with his reflections on the Warrumbungles, with first ascents protected by pitons, when a grade 17, pioneered in 1962, was the hardest route in Australia. Then Ben Cossey gives us a reminder of how much has changed in just a few decades with his first ascent of Light Weight Baby, grade 34–now Arapiles’ hardest climb.

Elise Marcianti explores how leaning into fear and instability on a highline, rather than fighting against it, helped her to stop fighting complex emotions on solid ground too. Letting it flow through her helped keep physical and mental balance. We also get behind the scenes of the 2024 Climbing Film Tour, chatting to Australian and NZ filmmakers whose offerings all explore the human element and how we evolve in our sport, in one way or another. Taking up climbing in his 50s, Ian Elliot sends a 28 before his 70th birthday; Sefton regains mobility with a ceramic hip replacement and discovers he can climb better than ever before; and Christian McEwen takes up on a visually stunning climb up an epic route—but one that at grade 14, as he explains, is achievable for most climbers despite how it looks.

Read on... and contemplate what the future might bring, for climbing and for you.

—Wendy Bruere, VL Editor

BY GERRY NARKOWICZ

When people think of major climbing destinations, typically the large granite faces of Yosemite, the splitter orange cracks of Indian Creek, or remote Patagonian pinnacles come to mind. All of these locations have well-known histories and have been the feature of many highly publicised climbing films, magazine covers and sponsored trips.

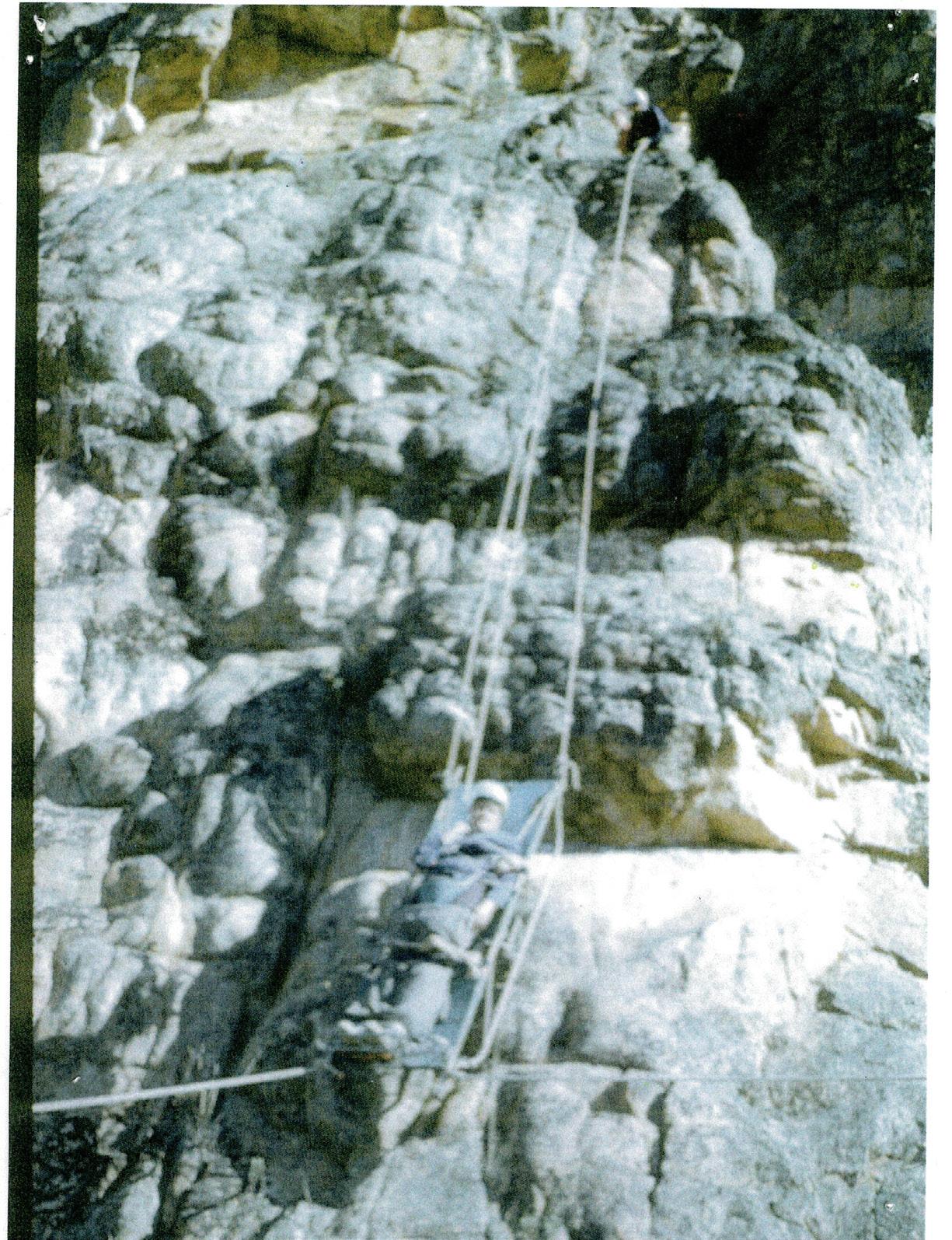

However, stationed on the other side of the globe in Australia’s island state is a collection of world class climbing, most of which seems to elude the spotlight. Gerry Narkowicz looks to fix this by shining a spotlight on the history of Tasmanian climbing in his new book, Climbing Wild.

Climbing in Australia has found its roots firmly in the soils of adventure. This is especially true of Tasmanian climbing in which the approach can often be considered one of the cruxes. It is not uncommon for a day out to include roped traverses along the sealine, tyrolean traverses, or routes with more access pitches (and rappels) than actual climbing pitches. Full-value adventuring like this can be a drawcard for climbers, but at times it presented a challenge for the pioneers of the Tasmanian climbing scene.

Climbing Wild walks the reader through the key moments in the development of Tasmania as a climbing destination starting right back in the 1960s. As it moves through the eras, it outlines the key routes, personalities and attitudes that defined the times. Laced with quotes from the first ascensionists and spectacular photography it is easy to get lost in the images alone.

I particularly liked the “New Millenium’s” account of the big wall style climbing in the Tyndalls—colloquially known as the “unclimbable cliffs” due to their difficult access and overhung conglomerate nature. This area remains one of the few locations in Australia where the dark art of aid climbing remains alive, with many new routes after the 2000s still requiring long stints in the etriers. There is a striking photo of Doug Fife, one of the key first ascensionists of the area, sitting on a free hanging haul bag with Lake Huntley in the background, which makes the suffering and fear described in the chapter seem worthwhile.

The book highlights the diversity in Tasmanian climbing. Only pages after the big walling war-stories of the Tyndalls, the reader finds themselves immersed in one of Australia’s hardest routes with the Hour Glass. The first ascensionist, Simon Bischoff, described the route as “virtually holdless”… and the photos certainly support his claim.

As someone whose attention is easily lost when confronted by long, overly detailed accounts of climbing antics, I really appreciated the fast-paced nature of the book. At almost 200 pages, the book is slightly intimidating; however, it manages to fit multiple stories on each leaf, with just the right level of specifics to keep you engrossed. Even for climbers already well aware of the possibilities down south, Climbing Wild is an entertaining read for weary wall climbers and newbie gym-goers alike.

Available at Adventure-shop.com.au

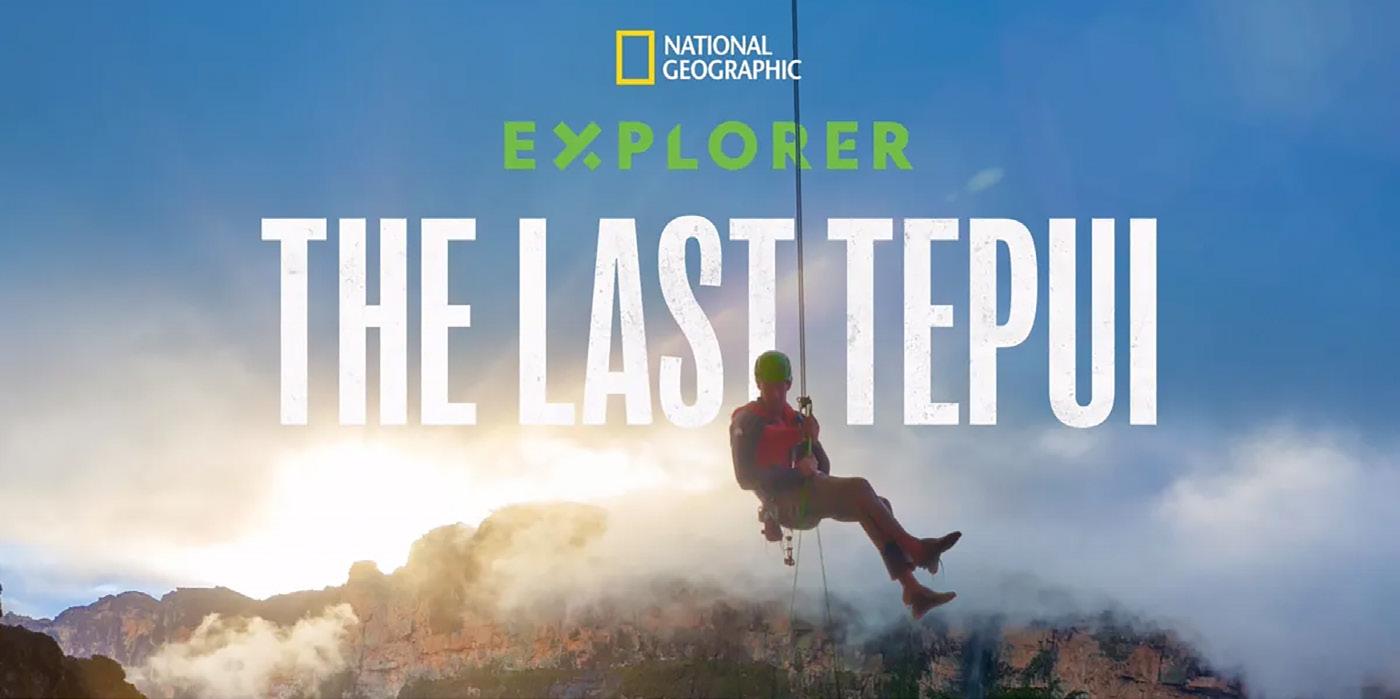

From searching for neutrinos in Antarctica to studying extremophiles in the depths of underwater caves, science has taken people to some pretty amazing places. Whilst the science might be intriguing, accessing these locations can present serious challenges and require a specific set of skills. The Last Tepui is a story about scientists looking to study areas only accessible by big wall climbers.

Tepui are mesas (broad, flat-topped mountains) in the Amazon, which are covered in rainforest. Their sheer walls and forested summits make them amazingly difficult to access. In the documentary, a team led by legendary climber Alex Honnold attempts to ascend one of these tepui, bringing a scientist along with them to study the unique flora and fauna on the walls. Alex has long been outspoken on

environmental issues—he has used his platform to talk about climate change, and his climbing skills to access hardto-reach places, including in the Arctic, to assist with climate research. Following a long approach through the mud and streams of the rainforest, it was not long before the team found themselves on a committing, harrowing ground-up first ascent of the tepui. With long run out sequences on holds described as “removable” the team quickly realises that this ascent is no longer a scientific mission but rather one of climbing nous. The majority of the climbing team tentatively

work their way up the wall, relying on questionable and infrequent piton placements. Alex, however, is filmed at one point hanging one-handed from a tiered roof and spinning himself around to admire the view.

This film demonstrates how a single location can hold different meanings to different people, and how these different contexts can interact symbiotically. Whilst the scientific team saw the possibility of undiscovered life, for the climbers it was also a rogue, fear-festering adventure in the making.

Streaming on Disney+

In the modern day, many regular climbing gym-goers will strategically plan their visitations to their local bouldering facility to avoid coming face-to-face with the muchfeared creation of the hangboard—the Climbing Dude-Bro! The idea of strength in our sport often stirs up images of grunting hordes of shirtless beta-sprayers flexing their biceps next to the latest boulder problem. Beth Rodden could not be further from this stereotype.

Across two podcast episodes, A Softer Strength examines some of the topics covered in Beth’s recently released memoir, A Light Through the Cracks. We come to understand how Beth maintained her status as one of the world’s most hardcore climbers through the tribulations of pregnancy and motherhood. She chats about how different stages of life forced her to reconnect with her more human elements. Self-described as a climber who

is “bumbling through life” in a similar way to everyone else, Beth found that becoming a mother drove her to develop a healthier relationship with her body, and to examine her personal expectations.

While this is an impressive development journey for anyone, climbing had been Beth’s identity—her livelihood, the focus of each day, the foundation of her relationships—since she was young. Such a shift in perspective presented unique challenges. Through a conversation about coming to approach climbing as just one part of a much broader life, the podcast reminds us to come off belay from time to time and look around at the other important aspects of our wellbeing.

This podcast is an interesting listen not only from the perspective of expecting parents, but also more generally for people trying to find the balance between a highly demanding physical sport and their everyday life. It

challenges notions of what it means to be strong, and shows the power and courage in embracing a more complex softer side.

Streaming on Spotify

ABOUT THE REVIEWER: Daniel is a Sydney based outdoor enthusiast who spends his free time rock climbing, cave diving and planning mountaineering escapades. Daniel has climbed and dived across Australia and New Zealand with a particular focus on traditional climbing. Somewhat ironically, Daniel spends his weekdays working as an insurance broker.

(HE/HIM)

NAARM/MELBOURNE

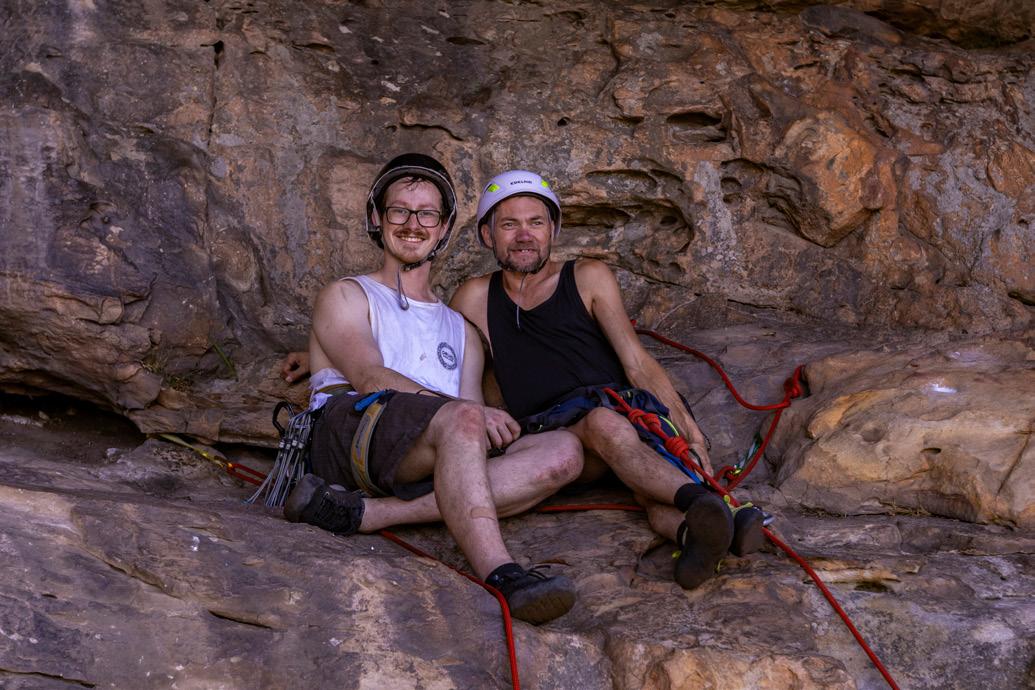

Interview and images by Claire Williams

JASON WHITER IS A VISION-IMPAIRED PARA CLIMBER WHO, ALONGSIDE COMP CLIMBING, EMBARKED ON HIS FIRST OUTDOOR CLIMB EARLIER THIS YEAR, STEPPING OUT FROM THE FAMILIAR WALLS OF INDOOR CLIMBING TO FACE THE HEIGHTS OF MOUNT ARAPILES.

CLAIRE FIRST MET JASON AT GRAVITY WORX, A GYM IN MELBOURNE WHERE HE TRAINS WITH HIS COACH, BEN DALBY. THEY INSTANTLY CLICKED. OVER CONVERSATIONS AT THE GYM, AND LATER AT THE CRAG, CLAIRE GOT TO KNOW JASON’S STORY.

When we walked into the gym tonight, you mentioned the pink climb was still up. But when I think of a vision-impaired climber, I thought it would be more like climbing in the dark, can you describe what you experience?

I can sort of make it out a bit. Colours aren’t good if they look similar; they might just blend in. Browns and reds blend in and looking up I can’t make out if a hold is a jug, a pinch, or a sloper.

I was first diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at the age of 11 which developed into more complications in my 20s. My left eye is completely damaged with no usable vision. My right eye is like looking through a pinhole on an average day; however, in bright light, it’s more like looking through baking paper.

Oh, wow! So, when you’re about to hit a hold, you don’t know what you’re grabbing?

My hand might look like it’s over the hold, but it could be too far in front or too far behind because I don’t have depth perception. I have other complications from diabetes, including neurological problems. I can’t tell you where my feet or hands are. I know they’re floating around somewhere, but I can’t pinpoint them unless I’m looking at them. I also have some nerve damage in my limbs, meaning I don’t have the full range of touch like the average person.

What initially got you into climbing?

I took one of my PT clients to Gravity Worx last year. He was doing a six-week weight-loss challenge and I wanted to change up the program. During the session, I had a go at it and thought, okay, this is pretty fun. So, I brought him back a week later. From that point, I started looking into my options for competitions and found out there was paraclimbing with a blind division.

What made you want to try outdoor climbing?

I loved the temptation to try something new. I really love nature and camping, so I wanted to take it all in with the fresh air and views. Seeing other para climbers do it also inspired me. After I lost my sight, I stayed in the same career as a real estate agent, before becoming a personal trainer. I haven’t allowed it to stop me from pursuing the things I’ve wanted to do. It has challenges, obviously, but it hasn’t slowed me down too much.

Prior to climbing at Arapiles I asked you what you were most looking forward to and you said, “Getting to the top”. Having done it now, what did it feel like getting to the top?

Words can’t really explain that feeling. I felt a strong sense of achievement. Looking out and seeing the wheat fields, the colour contrast of the yellow with the blue of the sky, I felt very relaxed. It was a warm day but the rock was cool, there was a light breeze just brushing past. I enjoyed sitting up there listening to the birds. It gave me a feeling of peace. All my worries, troubles, and mile-long to-do list were down below me. Up there, I felt a sense of calm that I hadn't felt in forever.

Has outdoor climbing been what you expected?

No, it’s probably more than I expected. There’s a lot more preparation involved than I thought. I underestimated the hike-ins and hike-outs; that was quite challenging. Needing to be guided over the terrain was probably more challenging than the climbs themselves.

I did four outdoor climbs and an abseil where you guided me over the top of the cliff to the edge and I had to put my trust in you all. There was so much—the climbs were great and the abseil was really fun. I enjoyed each component of the day.

Having tried both now, what do you prefer: indoor or outdoor climbing?

They both have their positives. Outdoors it was easier to climb and a lot more fun. I’d like to do more outdoor climbing, but I think I still prefer indoor climbing as it’s a controlled and more accessible environment.

UP THERE, I FELT A SENSE OF CALM THAT I HADN'T FELT IN FOREVER.

THE ANNOUNCEMENT THAT PARACLIMBING WILL BE INCLUDED IN THE 2028 OLYMPICS MADE ME IMMENSELY PROUD TO BE PART OF SUCH A HISTORIC MOMENT.

Having only begun climbing recently, you’ve already competed in quite a few climbing competitions, haven’t you?

I've participated in a bouldering competition, Lab Masters 2023, where I didn't perform well—I fell off everything. Despite that, I thoroughly enjoyed my time on the mat. I've also competed in the Australian Oceanic Qualifiers last year and the NSW State Titles this year. Although I didn't achieve any notable finishes, I faced tough competition, including a strong climber in a wheelchair. I only managed to outperform him because I was climbing an easier route. At the K2 Base Camp QLD State Titles this year, I placed 3rd. I was honored to make it onto the Australian team for the Paraclimbing World Cup in Innsbruck, Austria, this year too. While I did not qualify for the finals, climbing on the main wall was a significant moment for me. Watching the Innsbruck World Cup the year before had inspired me to pursue competitive climbing, so being there was incredibly humbling. The announcement that paraclimbing will be included in the 2028 Olympics made me immensely proud to be part of such a historic moment.

Do you have any future goals in climbing?

It’s a privilege to have represented Australia, but for me, it’s about raising awareness around a sport that’s not well known in the para community, especially the blind community. It’s hard to find a sport when you’re vision-impaired, and it would be good to show the community here that I am doing it. I may not be great, but I can do it. I want to show people where it can actually take you. It’s a worldwide competition; the pathways are there.

How has climbing impacted your life?

It’s given me something to aspire to. It’s definitely changed the way my body feels. My chiropractor said he’s never seen my body more aligned. I’ve had some neurological improvements—I’m starting to feel more in my feet. My flexibility has improved a lot, and the positivity from the climbing community has helped me mentally. It has allowed me to escape my everyday chaos. When I am climbing, I am in that moment and not thinking about the next email I need to respond to.

The climbing community has also been a blessing. In other sports I’ve experienced, the competitive side takes over and no one is supporting each other. With climbing it’s different—the people around you want you to do well, they don’t care what level you climb at because everyone has their own personal goals. It’s a positive environment.

What changes and growth have you noticed within yourself?

It’s tough to answer, but I think it’s given me the courage to take chances I may not have taken otherwise. It’s risky for me to get on a plane, healthwise the doctors don’t know how my body will react to the pressure and altitude, but I’m now taking those chances to pursue my climbing goals.

CLAIRE WILLIAMS is an Aussie rock climber with 14 years of photography experience. She has found her purpose combining her passions of climbing, adventure, travel and action photography.

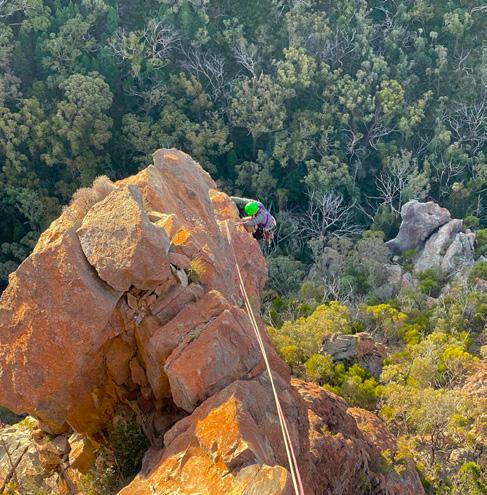

A NEWLY DEVELOPED CRAG JUST 20 MINUTES FROM HOBART BRINGS EVEN MORE ROCK OPTIONS FOR CLIMBERS LOOKING FOR VERTICAL METRES ON TASMANIA'S CLASSIC SEA CLIFFS. VL REGULAR DAVE BARNES TELLS THE STORY OF THE INFAMOUSLY CHOSSY CLIFF HE WAS DETERMINED TO DEVELOP.

Three years ago Conrad Walsburough and I went on a sea level traverse of the Alum Cliffs between Kingston and Hinsby Beach in Hobart. It was a glorious day as we navigated the boulders while looking up at towering walls of choss. Amongst it all I saw a group of walls that had more clean rock than shale. I was keen to have a closer inspection. A week later I rapped down the wall and saw a bucket full of potential. Countless hours and 50 wire brushes later, that place is named Genesis.

At the time, climbers were hearing frequent, foreboding news of closures at the Grampians, Arapiles, and Mount Warning. I wanted to make sure that this crag was kosher. I liaised with Local Council, State Government (Crown Land), and The Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania. I shared who I was, what part of the cliff I wished to develop and what that involved. I asked if there were any environmental or cultural elements climbers needed to respect.

Each in their own time got back to me. Local Council had no issue as Genesis was on Crown Land. The Crown had no issue as long as I built no tracks and respected nesting birds. I consulted with traditional owners who thanked me for approaching them and sent me a list of recognised cultural areas nearby and what to look out for if I came by any. Provisions were established for that if I did. Three green lights. I was ready to progress.

Paul Pritchard had dabbled on these cliffs in previous years. I assisted establish some climbs at Hinsby Beach. I knew this rock. The thing is though, most of it is a pile of vertical choss. The Alum Cliffs are made of Permian Mudstone. The metal smell of the rock is from the aluminium found within. The mud part needs discernment when climbing but once cleaned, sound rock is plentiful. Blocks of good rock are crossed by dirty breaks which on established routes have been cleaned. The breaks offer a welcome rest and often a knee bar.

COUNTLESS HOURS AND 50 WIRE BRUSHES LATER, THAT PLACE IS NAMED GENESIS.

The first route completed took five days of cleaning and bolting. A Wind Hovered (18) was the beginning. The climbs on either side stay with the biblical theme of the crag, so the route names read, left to right: In The Beginning (21), A Wind Hovered (18), Over The Ocean (18).

Subsequent to my early forays I kept returning, dragging friends along. With their help, I have established 14 routes with a combined length of over 300m of climbing. Several of them are really good. In fact, Tim Macartney Snape gave them the stamp of approval, saying, “A beautiful location and the climbing is good training for Everest.”

There are some mixed routes, but to ensure safety 12mm and 10mm stainless steel glue in ring bolts protect climbers, and double ring anchors mean climbers can avoid the loose shale edge at the top of the cliff. Many of the rings have been painted black to keep routes inconspicuous to non-climbers.

Genesis has some aces in its hold: thoughtful climbing in a stunning location above deep water, a 20 minute drive from the city, and only an eight-minute walk in. There’s a convenient access gully to the base of the crag, and sport routes of 20 to 30 metres. Climbing here requires sound skills. As a measure you should be able to comfortably climb two grades higher than any climb grade here.

I KNEW THIS ROCK. THE THING IS THOUGH, MOST OF IT IS A PILE OF VERTICAL CHOSS.

• Edge of Eve (19): a long arete that keeps you thinking all the way to the top.

• Braveheart (20): a beautiful face and looks just as stunning.

• In The Beginning (21): A cracker from beginning to end with a series of technical moves as the wall steepens.

• The Open Book of Enoch (22): On the steeper side for Genesis, it follows a seam through bulges with multiple puzzles to solve. After The Storm (20): A sporty shorter route at far left end of the crag. It has you strolling up a clean wall with a crux plum in the middle.

• 18 draws

• 60m rope

• Trad gear if you want to do Camnivorous Corner (18) or Hold The Line (17).

• Third climber for photos—if you want to capture the magic, shoot from the top

• The usuals (helmet, belay device, safety line, water, etc.)

1. Drive past Shot Tower on Channel Highway.

2. Turn left on Taronga Road, and park at the end.

3. Access to the Alum Cliffs Track runs between the houses (there is a sign to show the way).

4. On reaching the Alum Cliffs track proper, turn right and proceed past creek gully.

5. When on the flat again, keep going for 50 metres, turn left off the main track following green tape markers on trees.

6. This brings you to the cliff, near the top of A Wind Hovered. You can rap in from a tree here.

7. Alternatively, follow the creek gully to the bottom of the cliff—the gully has a four-metre rope to assist in the final scramble to the base of the climbs.

Warning: The top of this crag is loose. Use caution above and below cliff on uneven surfaces. Use existing access options.

Fitzroy, K2, Cho Oyu, Denali, Aconcagua, Kilimanjaro, Kosciuszko, El Capitan, Ama Dablam, Annapurna, Everest, Minto Peak... ...where will you take it?

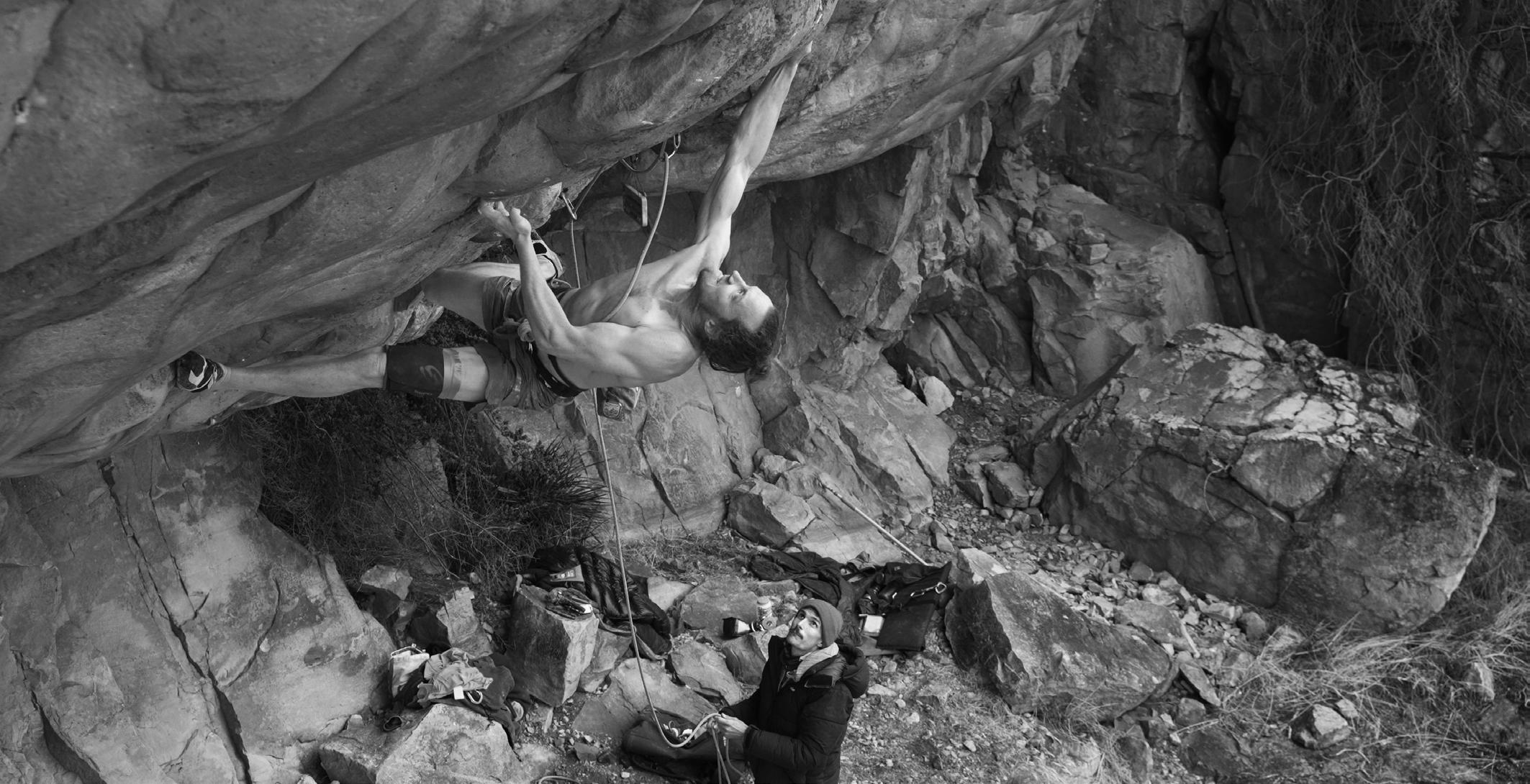

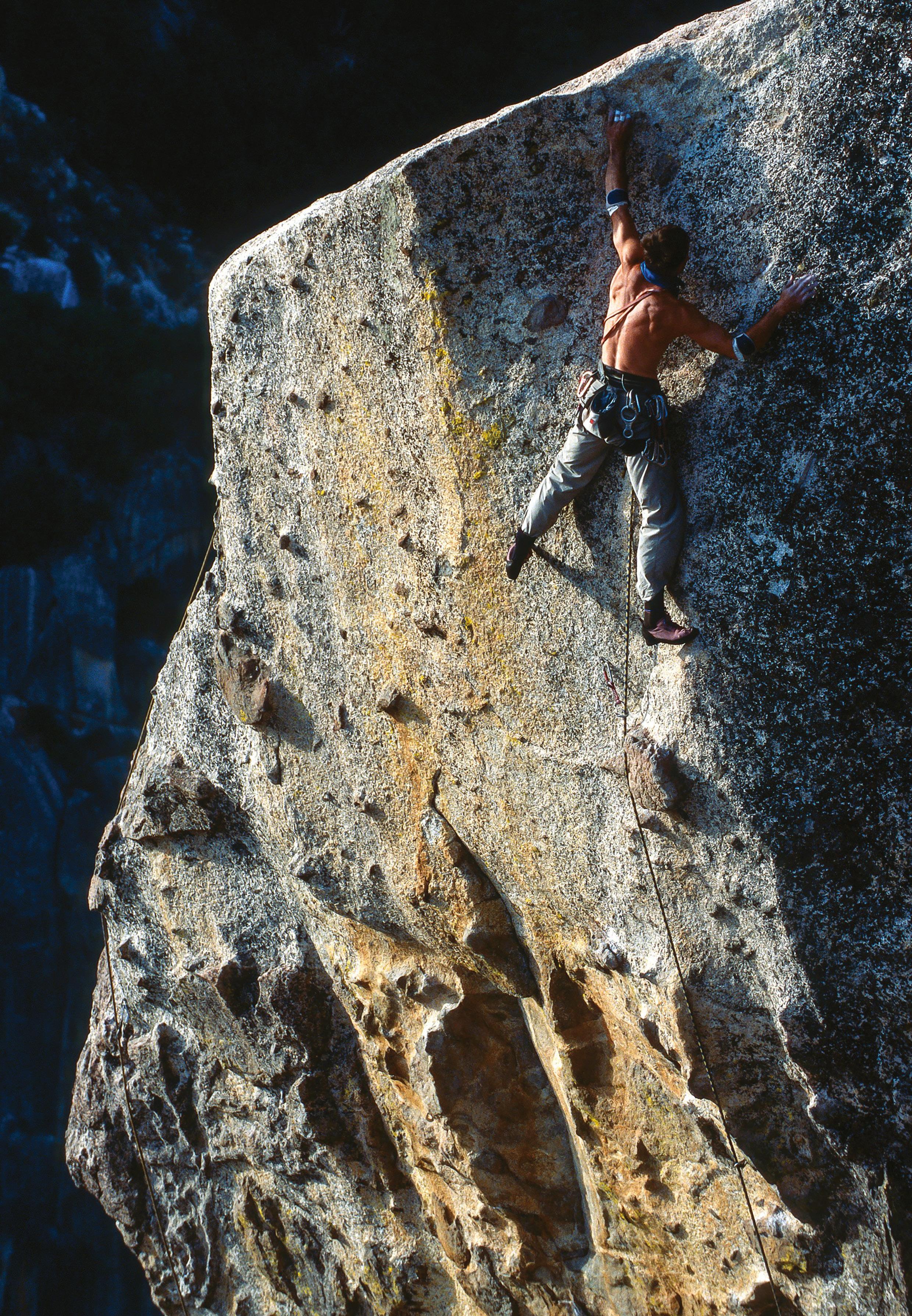

WORDS AND IMAGES BY NATHAN O’NEIL

When Queensland-based photographer Nathan was asked to be part of a shoot with Ben Cossey at his local crag, he jumped at the chance. He planned his perfect shot, and waited to see if the stars would align with lighting, flash and position… and if so, would Ben have enough skin left on his fingers to pull through the crux one last time?

Climbing days for me lately have unfortunately been few and far between. With two little bundles of joy (well, one bundle of joy and one two-year-old terror) coupled with the responsibility of keeping a roof over our heads in this economy, this dull boy is basically all work and no play at the moment.

Needless to say, I was damn excited when I got a phone call one afternoon asking me to jump on a shoot with Blue Mountains based filmmaker Brecon Littleford, for a project they were shooting for The North Face with their athlete and president of the Garden Training Club, Ben Cossey. Their plan was to travel from Sydney to Coolum Beach in Queensland and climb consecutive days at the best cave climbing crags around. The first stop north of the border (i.e. my turf) was to be Flinders Cave in the Scenic Rim. Brecon was planning on meeting local climbers and photographers at each location and asked if I would be interested in joining them at Flinders, along with Queensland crusher, Lucy Stirling.

The crux of the day was to capture Ben climbing the recommended hard classics with Lucy, with all the filming taking priority, but I was told that if I had a particular image in mind that I wanted to capture, they would do what they could to facilitate it. The day prior to their arrival I decided to head up to Flinders for a climb to re-acquaint myself with the routes Lucy had recommended Ben get on. It was also a chance to do us all a solid and dump some static ropes up there to save us from hauling them up along with camera and climbing gear on shoot day—a back-breaking load I’ve done too many times to count.

After their convoy of two classic climber vans arrived at the car park, and after Brecon and Lucas Corrotto had finished their happy dance when I told them they could leave their ropes in the van, we set off up to the cave of wonders. It’s always nice to get a first timer’s reaction as they peak around the corner and get their first glimpse as to just how big Flinders Cave is, and then again when they see the vista upon arrival.

Ben and Lucy spared no time warming up on some classics as Ben’s already flogged skin adapted to the sharp features of Flinders. The standout line for the day was ‘A Space Odyssey’—a steeper than steep 29 that packs a punch as you move through a mega sequence at what looks like 50 degree overhang low on the route. This is the line I wanted to shoot Ben on, should he have the skin left at the end of the day.

I’ve been experimenting with off-camera flash in my climbing photography lately as it brings a whole new element to the game and can really accentuate the climber in the breathtaking landscapes we often find ourselves. My idea was to have a flash attached to my drone which would hover out of sight above the tree line and be equipped with two to three grids which would help direct the beam of light from the flash to the area surrounding Ben, without spilling too much light over the whole cave. This would isolate his position on the wall for the shot. I wanted to showcase the position that Flinders Cave sits in the surrounding landscape of Peak Crossing. With the cave being perched high on the mount and overlooking the Great Dividing Range, it’s pretty speccy! I had a variety of lenses with me on the day but knew that the 15-35mm would be the one I wanted as I would need the widest lens I owned to bring in as much of the landscape as I could.

Ben onsighted ‘A Space Odyssey’ that afternoon in true Cossey style (many grunts) and after some more filming and with the light fading, the window to get this shot was rapidly closing. I set up the drone and velcroed my flash to it—which, when I write it down like that, doesn’t sound too smart, but I assure you, it was pretty solid— and sent it up. I gave the controller to Lucas and told him I’ll let him know where I need it when I’m in position. With access to a fairly easy route to the left side of the cave, I climbed and self-belayed up a short length of rope into a position I had set up earlier.

Before I could get my camera to my eye, I heard some commotion from down below. “Up, up! It’s going to hit the tree”.

TURNS OUT THE DRONE NO LONGER WANTED TO BEAR THE WEIGHT OF MY FLASH AND DECIDED IT WAS GOING TO LAND (IN A TREE). IT PLUMMETED TO THE GROUND WITH THE FALL LUCKILY BEING SOMEWHAT BROKEN BY A FEW SHRUBS.

Turns out the drone no longer wanted to bear the weight of my flash and decided it was going to land (in a tree). It plummeted to the ground with the fall luckily being somewhat broken by a few shrubs.

I simply yelled at Brecon, “Don’t worry about the drone, just get the flash!” as he descended a line from a tree trunk into the gulley.

It was well after sunset now and I was pushing my camera to its limit in terms of low light shooting. I had spied the moves during Ben’s onsight burn and knew the sequence I wanted to photograph; he was on the route sitting and waiting to start the crux sequence for me to get the shot. I told Brecon just to stand at the base and hold the flash in the air while I fired a test shot. I promptly dialled the camera and the flash in and told Ben to have a crack, despite being totally cooked. What a trooper!

With his classic blue singlet and taped on knee pads, Ben pulled through the crux sequence two or three times while I tried to snap the perfect frame. Given the prep that had gone into this moment I could have asked him to do it a hundred more times, but the light was sucked from the sky in no time and we were blanketed in darkness. I took a moment to examine what I had captured and let out an “Oh my god!” across the cave. Even though I could only see it on a little three inch screen, I was already stoked with the result. I wanted to get back to terra firma and show the crew what I had captured.

I feel like this image pays tribute not only to an amazing crag and its stunning scenery, but also to the climbers that are walking back

to their cars in the dark, putting in the work, doing what they love, fuelling their passion and making the most of the day. I have so many fond memories of exits by head torch (or phone light when I didn’t plan on a late exit) over the years. Those times are what encapsulate some of the things I enjoy most about climbing, and I was stoked to feel like I’d captured a bit of that spirit in some way.

Camera specs for the nerds

• Shot on Canon EOS R5 w/ RF 15-35mm f/2.8 @ 15mm

• Shutter speed 1/25 (!)

• Aperture 2.8

• ISO 5000

• Speedlite used was Godox V1 with unknown number of grids

Five Caves Five Days—the film this shoot was in aid of—will be touring around Australia in November 2024. In this uniquely Australian climbing adventure tale, Ben Cossey travels in his van along the east coast, from Campbeltown, NSW, to Coolum, QLD, meeting local climbers along the way to show him the goods at their local crags. Follow @thenorthface_aunz for screening updates.

NATHAN O’NEIL is a Scenic Rim-based award-winning photographer and filmmaker specialising in adventure, lifestyle, and action sports. With a background in outdoor sports and a keen eye for emotion, he captures raw moments in the wild, infusing landscapes with human connections.

Luke Hansen Don’t Believe the Hype (31) Boronia Point.

Photo Ben Sanford mountainequipment.com

BY WENDY BRUERE

Hitting screens in November, the annual Climbing Film Tour is back with a new collection of films, each with engaging storytelling and inspiring cinematography, guaranteed to get you planning for your next adventures at home and abroad.

Motivated by a desire to bring the climbing community together and share the stoke of vertical adventures, the team at Vertical Life and Adventure Entertainment have curated a selection of local films from Australia and New Zealand, along with international offerings. The films explore local stories and remote destinations, delving deeply into personal perspectives while showcasing vast ancient landscapes.

Three films from Australia and New Zealand are confirmed, with more from around the world still to be announced. While we can’t give away what’s still under wraps, we’re thrilled to bring you behind-the-scenes interviews with the directors of Ian, Ceramic and Inside Out.

THE FILMS EXPLORE LOCAL STORIES AND REMOTE DESTINATIONS, DELVING DEEPLY INTO PERSONAL PERSPECTIVES WHILE SHOWCASING VAST ANCIENT LANDSCAPES.

MOST PEOPLE IN THEIR 50S START TO DECLINE A BIT, BUT HE BEGAN CLIMBING AND KEPT PROGRESSING RIGHT UP UNTIL HE TURNED 70.

When filmmaker Matt Raimondo met Ian Elliott—then in his late 60s—casually crushing at the local crag, Coolum Cave, he was intrigued.

“Witnessing a senior climber matching, if not surpassing, the skill levels of much younger climbers was both humbling and inspiring,” said Matt. “Everyone is inspired by Ian when they meet him. For young people, he’s the age of their grandparents and climbing harder than they are; people my age—forty-ish—are inspired because it shows we can keep climbing for 30 years.”

While Ian succeeded in his quest to send a grade 28 shortly before his 70th birthday, it wasn’t until Matt took the first steps for the film that he realised how new to climbing Ian was.

“When we meet these older climbing legends, we assume they’ve been climbing all their lives and just kept it up,” explained Matt. “In

our first interview for the film, Ian told me he started climbing in his 50s. Most people in their 50s start to decline a bit, but he began climbing and kept progressing right up until he turned 70.”

Matt was thrilled to be able to share this perspective on the possibilities in life with viewers. “I wanted people to see that it doesn’t matter how old you are, it’s never too late to start climbing, or anything. You’re not too old to start climbing, or start a new sport, or keep progressing—Ian is proof that if you want to do something, you can,” said Matt.

“I wanted the film to connect viewers with the same feeling of inspiration people get if they’re lucky enough to meet Ian in person—I wanted to share that feeling with other people,” he added.

Matt was also excited about the opportunity to introduce viewers to his local crag, Coolum Cave.

THE FILM WAS ALSO A WAY TO CREATE SOMETHING THAT REALLY SHOWCASED A PLACE WHERE I LOVED TO CLIMB. IT’S OUR LOCAL COMMUNITY, IT’S A WORLD CLASS CLIMBING PLACE, AND I WANTED TO SHARE A PLACE THAT I FIND INCREDIBLY SPECIAL.

“The film was also a way to create something that really showcased a place where I loved to climb. It’s our local community, it’s a world class climbing place, and I wanted to share a place that I find incredibly special,” he said. “I’ve shot films for work projects around Australia and overseas, so to shoot something that’s just two minutes from my house gave me the opportunity to make it really stand out.”

Being so familiar with the crag, and living so close by, meant Matt was able to secure highly polished footage. “I knew all the angles we could get to, I knew the climbs really well, and I had other filmmakers in my network, so we were able to elevate it to this really cinematic level,” he explained. “I’d go up in the morning for sunrise, or evening for time-lapses, and there was nothing stopping me because it’s literally shot in my backyard.”

Collaborating with cinematographer and fellow climber Caleb Ware, they innovated ways to film different angles, rigging a crane out of rope rather than using drones, to capture each move as Ian climbed. “It’s really cool when you see some of the behind the scenes shots that show how we did it,” said Matt.

“We also needed a lot of help from the local climbing community who gave up their time to climb to operate the camera ropes, while using headsets to communicate the movements we required,” he explained. “Everyone did an incredible job to make it extra special, and we all did it because we loved Ian and believed in the story.”

The film details Sefton Priestley’s journey as a competitive climber whose hips start to fuse. Initially told his climbing days were over, he sought out a second surgeon who gave him a life-changing ceramic hip replacement.

New Zealand filmmaker Anna Pearson had known Sefton for many years before she started filming. Acquaintances from way back, Anna and Sefton first met at university. Years later, having shifted her focus from journalism to filmmaking, Anna was casting around for ideas for her next film project and thought of Sefton and his story.

“He was really onboard, very gracious with his time and energy,” Anna said. “The challenge was finding a way to tell the story about something that had passed, to make it interesting despite being an ‘after the fact’ type film—it’s quite interview driven.”

As part of the process, she was able to access archival footage of Sefton climbing in 2012. “It really shows his lack of mobility. Even Sefton said it was quite shocking to look back on. There’s a shot of him trying to climb up a fairly easy climb…he looks like a wooden puppet, so stiff and immobile,” Anna said.

Filming Sefton 12 years later, long after the hip replacement, highlighted the difference. “We did a shoot day at Flock Hill, a nearby beautiful bouldering location, and went out with Sefton and his three boys,” said Anna. “I realised how much of his life the hip replacement had given him back—to be an active dad, carrying the bouldering mats, spotting his kids while they bouldered. It wouldn’t have been possible without the surgery.”

The surgery brought some unexpected benefits too. “Sefton explained that after the hip surgery he had hoped to be able to lead climb like he used to—but he found that he could actually climb far better. He had a whole range of motion available to him that he hadn’t had before,” said Anna.

SEFTON EXPLAINED THAT AFTER THE HIP SURGERY HE HAD HOPED TO BE ABLE TO LEAD CLIMB

LIKE HE USED TO—BUT HE FOUND THAT HE COULD ACTUALLY CLIMB FAR BETTER.

Sefton also discovered that his improvements in climbing weren’t confined to leading. Even though he had initially dismissed the idea of ever bouldering again, fearing it would be too much load and too much impact on his hips, he realised he could do it—and do it well—after surgery. “He even went on to win Nationals for a third time,” said Anna.

“He hadn’t really realised how much he had adapted his climbing style. When he was climbing in his 20s he went to the world championships, but he couldn’t climb at that super elite level and his limitations showed up,” Anna explained. “He described it as he did a lot of very twisty climbing—lots of overhangs where the twisty climbing helps a lot—but when it came to splaying yourself against a flat wall it was harder for him to open out that way.”

As part of the filming, Anna also sought out the surgeon who had performed Sefton’s hip replacements. “He talked about how for his young, fit and active patients he chooses ceramic hip replacements, because otherwise they would wear out the plastic,” said Anna. “And I think he was just incredibly delighted to hear that Sefton is leading such an active, fulfilled life.”

Anna added that she hopes viewers “get a sense of Sefton’s attitude, his drive and positively in overcoming this and living the kind of life he wants.”

The first surgeon he saw told him he was done climbing, but he got a second opinion and it changed his life, said Anna. “I liked that attitude—don’t give up the first time someone says no!”

Inside Out has a distinctly otherworldly feel about it. Filmmaker Christian McEwen said his concept was to create a dreamlike experience, encouraging viewers to explore their imagination. “If you could dream, where would you end up?” he asked.

This vision was part of the reason for the choice of location. “The Warrumbungles has a kind of ancient, dreamy landscape, that almost doesn’t look like it should be sitting there. The rock spires barely look real,” Christian said.

This is only his second film, and he said he learnt a lot along the way. “I’ve dived into this world of filming and directing, but at the same time I’m climbing as well, so I’m dealing with the logistics of climbing and directing at the same time,” Christian said.

“I’ll look around on route and think, ‘this is a really good shot’— but when you’re climbing you need to be focused on what you’re doing!” he explained. “I’m learning how to navigate being a climber, a director and a producer, and learning how to blend those three things together.”

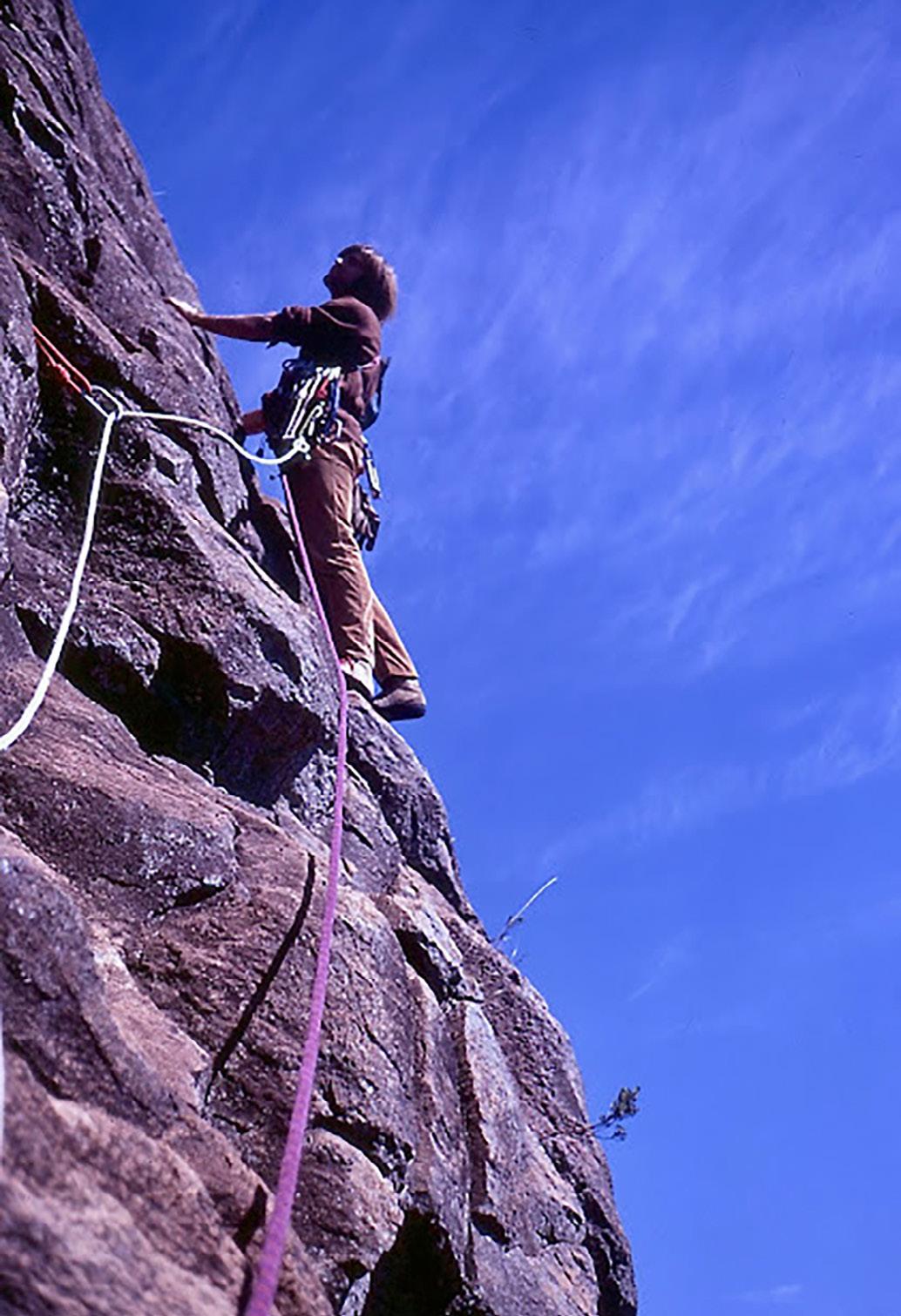

The climb chosen as the focus of the film is the classic Cornerstone Rib, a 190-metre grade 14 trad route. First climbed in 1962 by Bryden Allen and Ted Batty, it’s probably the most popular route in the Warrumbungles.

“It’s a really bold line, not hard climbing, just a prominent, bold line—when you film the route it’s not just a rock face amongst other rock faces. It’s also a classic must-do route for any climber,” explained Christian.

“We’re not full professional climbers by any means, and the level we climb at can be achieved by most climbers. I like to inspire people to do something that I believe most climbers are capable of.”

THE WARRUMBUNGLES HAS A KIND OF ANCIENT, DREAMY LANDSCAPE, THAT ALMOST DOESN’T LOOK LIKE IT SHOULD BE SITTING THERE. THE ROCK SPIRES BARELY LOOK REAL

GRAPPLING WITH FEAR IS A FAMILIAR CONCEPT FOR CLIMBERS. MOUNT BEAUTYBASED HIGHLINER ELISE EXPLORES HER RELATIONSHIP WITH FEAR, AND HOW SHE LEARNT TO MOVE WITH IT, NOT FIGHT AGAINST IT.

Easter was approaching and the word was going around for a highlining gathering at Arapiles. The last time I had been there was my first experience on the line, a midline called D Minor, and it had won me over. I couldn’t commit to standing—the mere thought of my body leaving the line, the only point of “security”, was too overwhelming. I was uncomfortably aware it was just a leash and a small piece of webbing that allowed me to be suspended in this space. As my feet wobbled below me, trying to balance my weight, fear set in.

THE FEAR WAS VISCERAL. I COULDN’T OVERCOME IT, BUT IN THAT MOMENT I MADE A DECISION THAT I WOULD RETURN.

Unlike climbing, there was nowhere to wedge in to, no wall to put my hands against, and nothing to cling onto to dampen the shakiness that shivered up through me. I panicked. The fear was visceral. I couldn’t overcome it, but in that moment I made a decision that I would return. I told myself I would keep showing up and sitting with the exposure until I was able to be with it and walk the line.

The upcoming highlining gathering at Arapiles was my opportunity to return to where the journey started, when I had first sat on the line, clinging to it. Since then I had built the courage to roll out and attempt to stand over the crashing ocean waves below in Freycinet. I spent time on a Perma rig, and returned time and time again until I could stand and then walk, and eventually I had sent it across a highline over The Gorge on Mount Buffalo. EVERYTHING SLIPPED AWAY, MY THOUGHTS STARTED TO DISSIPATE, TIME FADED AWAY. I ONLY SAW THE LINE IN FRONT OF ME, EVERYTHING BOTH AROUND ME AND WITHIN ME BLURRED OUT OF FOCUS.

The 40 metre, 60 metre and 100 metre lines at Arapiles had been set up. I set out with my friends Rene, CJ and Peter for a sunrise mission. We walked up to King Rat Gully in the dark with harnesses in hand and tea bags in pockets. We shared a tea as we sat in the nook of the rock, witnessing first light appear over the flat horizon ahead. Between moments of conversation, we slipped into our own focus as we each prepared ourselves. When enough daylight for us to see eventually seeped onto the line, we began.

I mounted the line and let my gaze narrow to the width of the line. Everything slipped away, my thoughts started to dissipate, time faded away. I only saw the line in front of me, everything both around me and within me blurred out of focus. The stillness amplified my senses. I could feel every muscle, every toe tense. I could feel my shoulder blades lower and my spine lengthen. In sync with my breath, I stood up and into the expansiveness that lay ahead.

I stood unapologetically into the freedom the space offered, and I welcomed the fear with arms wide open. We leaned into the exposure as the sun started to expose itself above the horizon, and together we watched the colours spill across the sky. We walked the highline until the yellows and oranges transmuted to blues, until our legs burned with fatigue, and our minds were content from a state of bliss. As I came in from the line, I looked over at the D Minor line sitting below me and reflected on the journey and where it all began.

I FELT CONFRONTED NOT ONLY BY THE SHEER EXPOSURE OF THE FAR HORIZONS AND SPACE BELOW, BUT BY THE EXPOSURE OF MYSELF—MY OWN FEARS AND LIMITATIONS.

When I had first sat on that line, I felt confronted not only by the sheer exposure of the far horizons and space below, but by the exposure of myself—my own fears and limitations. When I sat there it stripped me bare, the vastness sank right through me. I had no

option but to sit through it, feel it and embody it. That exposure exposed parts of myself I hadn’t seen or felt before. Those times fighting the line slowly dissolved as I learnt to surrender.

Someone had told me when I was wobbling to move with it, not against it. It felt counterintuitive to not try to counteract it, but it works. I swayed with the motion and continued to walk on. I noticed that the advice applied to my emotions and mind too— going against my thoughts and feelings only threw me more off balance. Slowly I stopped battling with the line, with my emotions and my mind, as I learnt to move with the motions, both physically and mentally.

I AM OFTEN OVERLOADED AND OVERWHELMED, BUT IN MOVEMENT I GET MOMENTS OF RESPITE, A REJUVENATING BREATH OF FRESH AIR AND A BREAK FROM THE SPEED OF MY THOUGHTS.

Fear is something that is and will always be present. It will continue to manifest itself as a tight grip and a dry mouth, but I know that fear is there to protect me—an alert to potential dangers, a survival mechanism deep within us.

I can now allow it to be there, but not to control me the way it did for the eight years I spent in the grips of anorexia. During that time, I became wheelchair bound, tube fed and medically unstable. I was in and out of hospital for months and spent years in treatment. I grew to no longer trust myself or anyone around me. I became afraid to eat certain foods, then afraid to eat anything at all. I began to fade away and the fear that was there to protect me, to preserve life, became the very thing that almost took my life.

After a long period of not eating, running away and being unwell, I began to choose recovery. I started to show up six times a day to the dining table and face it. I went through therapy and not only healed but rediscovered myself. In the process I also discovered I have ADHD. I realised that highlining, as well as the mountain bike riding, trail running and climbing I do, allows me to access a place in my mind of total stillness as flow. For years I had found it so hard to navigate the world with the constant chaos, confusion and clutter in my mind. I am often overloaded and overwhelmed, but in movement I get moments of respite, a rejuvenating breath of fresh air and a break from the speed of my thoughts. It's where everything slows down, worries fade and I enter a flow state. I become fully present.

Highlining has allowed me to deepen my comfort with discomfort and find freedom within the fear. It gives me a way to access flow state and a stillness in my mind, and to test myself, find new limits and reach new heights. At the Easter highlining gathering at Arapiles we all got to dive to those places within and open up to the exposure. We walked alongside fear, and alongside each other.

ELISE MARCIANTI is an artist and runner, who is usually out exploring the trails with paint in her hair. Formerly based in Melbourne and now in Bright she spends her time exploring the outdoors climbing, trail running, snowboarding and most recently highlining.

PETER ROWED is a regular 9-to-5 desk jockey, chasing adventures whenever the weather and life allow.

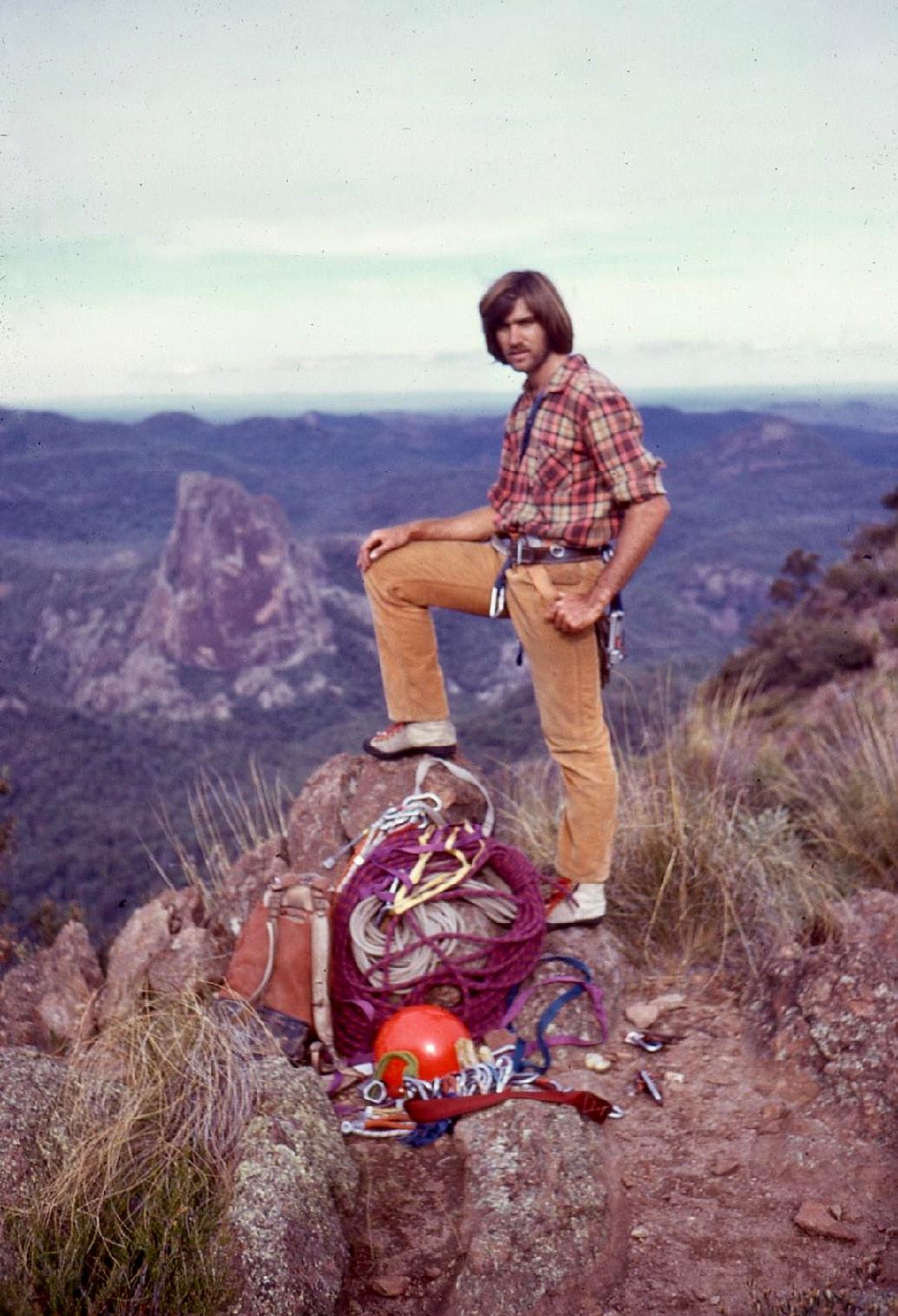

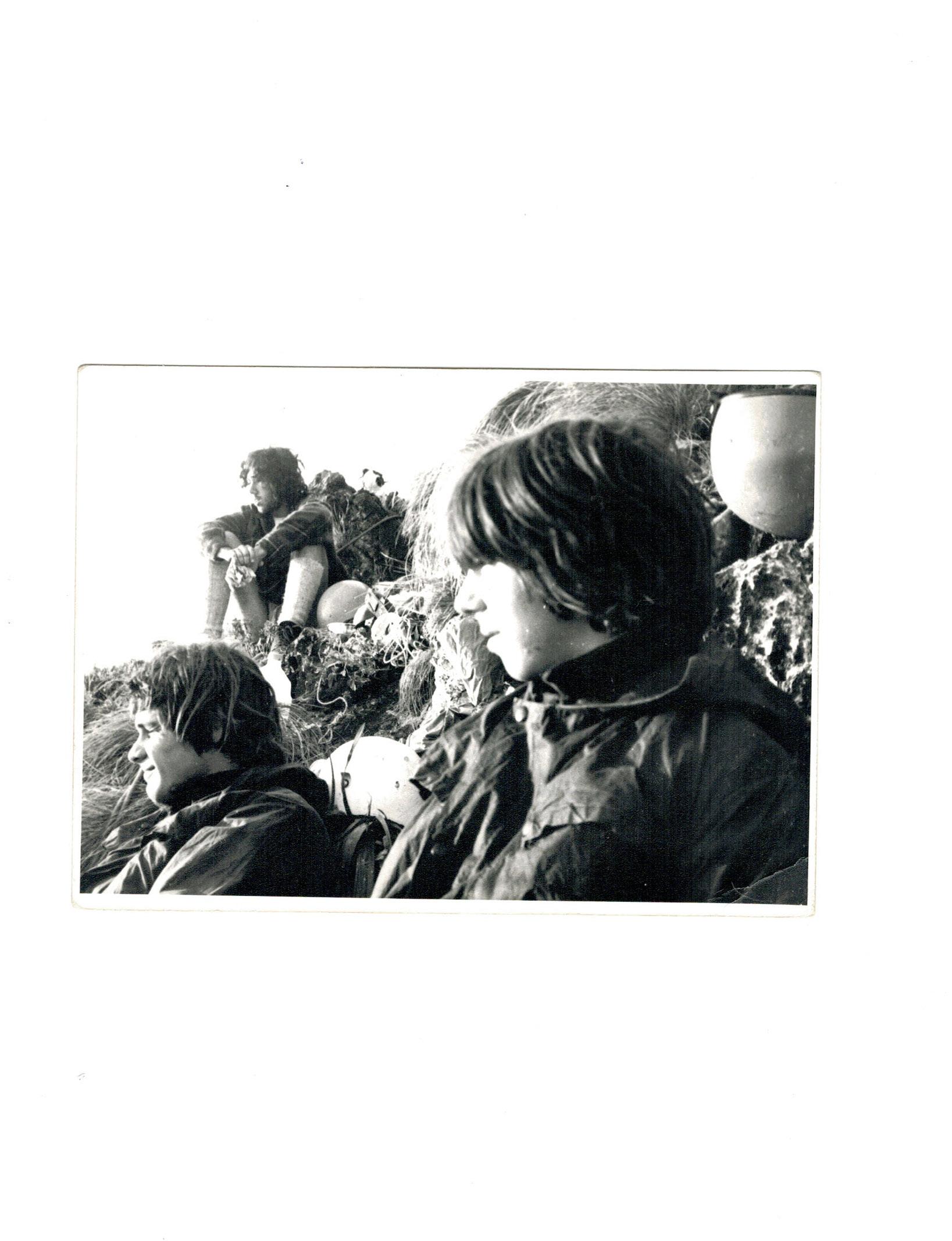

WORDS BY KEITH BELL

IMAGES BY KEITH BELL, TIM MACARTNEY-SNAPE AND MORE

CLIMBING LEGEND KEITH BELL HAS BEEN EXPLORING THE ‘BUNGLES SINCE THE 1960S. WITH A WEALTH OF TALES OF FIRST ASCENTS, NEAR MISSES AND INSIDER ADVICE, HE TAKES A JOURNEY ALONG THE INFAMOUSLY WILD ADVENTURE ROUTES THAT WEAVE THEIR WAY UP THE ANCIENT VOLCANIC SPIRES.

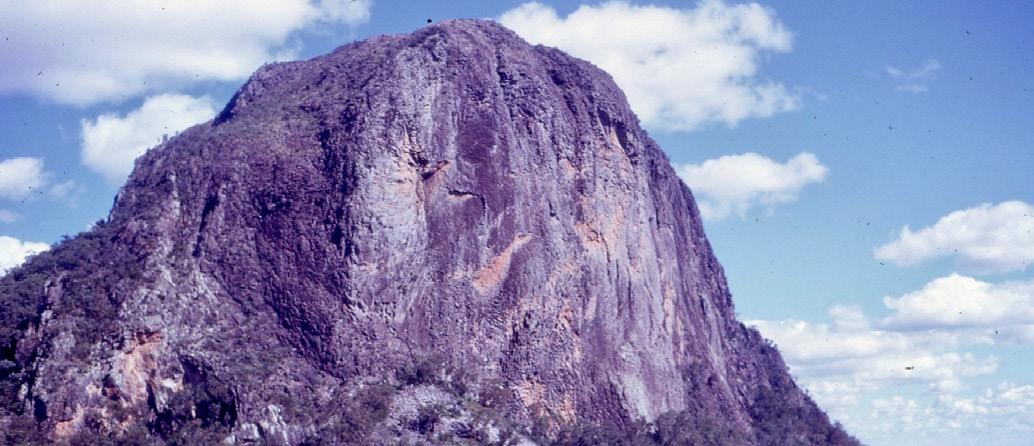

The Warrumbungle National Park, located about 500 kilometres northwest of Sydney by road, holds within its boundaries a collection of volcanic peaks that are a magnet for many visitors— including hikers and rock climbers. For the latter, the steep, multihued trachyte walls of orange, yellow, brown, red and grey of its four main peaks—Crater Bluff, Belougery Spire, Bluff Mountain and Tonduron Spire—offer some of the finest trad multi-pitches to be found in Australia.

Crater Bluff and Belougery Spire are accessed by a somewhat steep, but well-maintained and well-travelled trail, which leads to a lookout point between the two crags. Grand High Tops, and its highest point Lughs Throne, is a famous landmark of the Warrumbungles’ main hiking trail, providing spectacular views of not only the crags, but of the surrounding countryside and plains.

Sacred significance of crooked mountain

This remarkable area holds deep meaning to First Nations people. The National Parks website explains, “Warrumbungle is a Gamilaraqy word meaning ‘crooked mountain’, and for many thousands of years it has been a spiritual place for the custodians of this land, the Gamilaraay, the Wiradjuri and the Weilwan. The landscape, plants and animals of the park are a constant reminder of its sacred significance to the Aboriginal people today.”

Looking back in the direction that you have come from lies the thin outline of The Breadknife, a sinuous and spectacular dyke that radiates out from the most climbed route on Crater Bluff, indeed in the ‘Bungles, Cornerstone Rib – a seven pitch, grade 14, Bryden Allen classic. While the Breadknife, with its smaller subsidiaries the Butter and Fish Knives, offer some very good climbs, climbing on them has been banned for many years owing to the access tourist tracks sidling alongside both sides of the dyke.

Balor Hut can be found a short walk from the bottom end of the Breadknife. Most climbers stay here for the convenience of its location. Its tanks also provide a good supply of water, which is important as the national park lies in a semi-arid area of New South Wales.

Belougery Spire is the sentinel back on your left. While Vertigo (four pitch, grade 10), its most popular route, is clearly visible rising three pitches above a high terrace, a drop beyond conceals the longer, harder classic climbs of Caucasus Corner (12 pitch, grade 17) and Out and Beyond (nine pitch, grade 15).

The latter has a famous traverse near its start whereby the initial 10-metre exposure becomes 100 metres at its end. After the initial corner of the former, the route rises diagonally to the left to ascend an exposed and elegant buttress to the summit.

To the right, peeking over Dows Plateau, is the stunning profile of Bluff Mountain, a long 300-metre high cliff that contains the best routes in the Warrumbungles: Stonewall Jackson (12 pitch, grade 20), Elijah (12 pitch, grade 17) , Ginsberg (11 pitch, grade 19) and many others. Almost all who have ventured on this peak have been enthralled by the spectres of wedge-tailed eagles (Australia’s biggest raptor) circling lazily on the face’s thermals.

Bryden Allen and John Ewbank were the first to climb the main precipice via Elijah in 1965 over five days. John was belaying Bryden on a small ledge using primitive nuts while Bryden thought a bolt should be placed. He then led out, placed a runner around a block and was moving diagonally away from it when he felt what he later described as a “fearful tug”. Bracing himself he managed to stay on; it transpired that John had fallen off the small ledge after his belay disintegrated and Bryden had halted his fall. Bryden was always quick to quip that it was a case of the leader belaying his belayer— while he was leading.

For many years the start of Elijah, the first major route on the mountain, was marked by an early pair of Bryden’s friction boots hanging by their laces off a small flake.

As one tops out onto Lughs Throne, the eye is drawn towards the overpowering presence of Crater Bluff with its spectacular series of ribs and gullies rising abruptly before you. The upper reaches of Tonderburine Creek carve out the rock in between, forming a deep and sweeping valley. The abode of Cornerstone Rib, Rib and Gully (six pitch, grade 13), Vintage Rib (seven pitch, grade 15) and more, lies directly across the valley. On its right wall again hidden from view resides Lieben (six pitch, grade 17), for a long time the hardest route in Australia, pioneered by the mighty Bryden Allen/Ted Batty team in 1962.

But also worthy of note is the first ascent of this peak, made in 1936 by Dr Eric Dark, Marie Byles and Dorothy ‘Dot’ Butler. Suffice to say just getting to this place then would have been quite a trek. At the summit to celebrate their success, and to indicate to others below that they had indeed summitted, a fire was lit—as well as probably to boil a billy for a cup of tea. Unfortunately, the fire got away, and they set the summit of Crater Bluff alight, reproducing a scene perhaps worthy of the peak’s volcanic origins. My first climb in the ‘Bungles was this very peak in 1964, with manilla rope, sandshoes, manilla slings, steel carabiners and a bowline tie-in. I found it a difficult proposition.

In 1969, Howard and I made the fourth ascent of Lieben on Crater Bluff, with an audience of Victorians, including Keith Lockwood, Roland and Anne Pauligk, as well as their menagerie of parrots

that had travelled with them. (This is entirely true, by the way. Roland’s pet parrots were infamous at the time, and it’s even said that they would unclip ropes from runners.) Now, one of their feathered friends wanting to get a closer look at the action flew up and perched on an important handhold just above me on the crux pitch. Each time I reached out to use the handhold a slashing beak would nip at my hand. Was this the harbinger of the interstate war (Victoria versus the rest) that raged through the seventies?

As I hung about, a crazy thought went through my mind. What if I pushed the parrot off, and it fell to its death at Roland’s feet some 150 metres below. The idea of tangling with Roland made me think I would be better off going tandem with the bird. But in the end it was going to be the cocky or me and stuff the consequences. I took out my peg hammer, reached up and gently but firmly pushed the bird over the precipice. It fell, completing a neat somersault before it unfurled its wings, and thankfully flew away without sustaining any damage. Next day Roland and Keith did the fifth ascent, and I was pleased to see the parrot perched on Roland’s shoulder as he climbed the crux pitch. At least he had a feathered handicap too.

Beyond is the squat shape of Tonduron Spire, a lonely waif lost in a wilderness of scrub. Shaped like a classic jelly it was the last major crag to be savoured by climbers, largely owing to its isolation and the nature of its rock. It can be reached from the Grand High Tops with a lengthy walk down Tonderburine Creek, or approached through the township of Tooraweenah and eventually by walking up Tonderburine Creek. Neither way is easy, hence the delineation.

The area behind the Grand High Tops is the northern, more civilised and frequented part of the national park, approached through the township of Coonabarabran. It contains the Park HQ, campsites with amenities and a network of well-maintained trails. Tonduron Spire, on the other hand, is situated in the southern undeveloped wilderness area of the park. Its South Ridge (6) was first climbed by Dr Eric Dark and party in 1932 who described it as, “ The most gayest and light-hearted climb I remember, everyone being in the highest spirits”. This ridge is now used as the descent from the peak.

When I first went there in 1972 with Greg Mortimer, the access road from Tooraweenah led to the farmhouse of the Gale Family. Their homestead was situated on Picnic Ground Mountain, just across from the present Gunneemooroo gate on the boundary of the national park. Back then the Gales held the pastoral lease to the area but after the lease expired the house was removed and the area was incorporated into the national park. After a pleasant cup of tea and scones, we were given permission by the family to drive up the then navigable dirt road along the valley to Gales Bore and windmill, the

campsite and the setting out point to access Tonduron. Two climbs were completed, Virago (nine pitch, grade 20) and Saratoga (seven pitch, grade 17) on the northeast face.

In 1974, Ian ‘Humzoo’ Thomas and I teamed up for a trip into Tonduron. After man-handling and coaxing my low-slung Mini Minor over innumerable rocky creek crossings and dodging massive boulders, we finally arrived at the Gales Windmill campsite. Next day we climbed the magnificent corners, cracks and slabs of Antares (five pitch, grade 19) that led directly up the imposing northwest face. The following day we decided since it was blowing a gale to have somewhat of a rest day. We thought we might have a go at what is properly known as the Northern Spire, but which seems to be called by nomenclature of a less savoury nature. I prefer to liken it to a Saturn rocket but perhaps this dates me too much.

With the wind whistling through the trees, I led up the initial chimney formed by the fuselage of the rocket and the small tower on its right, which looks like its booster. While easy at first it became a bit of a grunt as the walls started to close in. Squeeze chimneys are never fun, but I finally struggled out of its confines to belay on the top of the booster. After bringing Zoo up I got him to pose precariously on the top of the booster and obtained what I regard as my favourite photo of him. Zoo climbed the off-width chimney that was formed by the remainder of the rocket and the main cliff. He belayed on a piton driven below a small rock that formed the summit.

Unexpectedly, the spire did not lean against the main face but stood

independently like a cricket stump hammered into the earth. As he belayed, Zoo was exposed to the full force of the wind.

I was about halfway up when he yelled down, “For f…’s sake hurry up. The prick is moving in the wind!”

Although I was somewhat disbelieving, I was up the crack faster than you can bowl a maiden over. Now I know that you are thinking that we had probably imbibed a little more than fresh air, but if you are in the area when a strong wind is blowing … If you are still not convinced that pinnacles can move like metronomes, then try climbing Thanatos at Mt Blackheath in the Blueys if it is still there, and I’m sure that you will swing around to our way of thinking.

In 1987, John Fantini and I arrived at the Guneemooroo (Tonduron) campsite at about 2am after a long drive from Canberra in John’s much loved old Holden—read squeaky and very noisy. We had hardly pulled up when another car appeared and parked nearby. We were incredulous: two parties of climbers arriving at this isolated spot at the same time. As our eyes became accustomed to the dark, we could make out the other car was some sort of ute.

More tense minutes passed and finally a figure got out and walked over to us and asked in a stern, unfriendly voice, “What are you blokes doing out here this time of night? ”

We explained that we were going into Tonduron to climb. At this the silhouette breathed a sigh of relief. He went on to explain that he owned the nearby sheep station, and he thought that John’s car was a sheep duffer’s truck. I could sense John was rather indignant

about this slur on his machine, and I remembered the fate of an errant climber who once dared to spit on his car outside the Newnes Pub in the Wolgan Valley.

Fortunately, John displayed great restraint by not reacting to this affront, because as the farmer opened his car door the light revealed his mate sitting there holding two rifles. What excitement and we hadn’t even reached the crag. This incident is remembered in stone by naming a new route on Tonduron—Starlight Express.

The Warrumbungles offers real adventure climbing, but it will be less of an adventure (or disaster) if the following suggestions are followed. Overcoming long access walks, length of climbs with their attendant problems of difficult route finding and excessive heat (or cold and wind) are the main determinants of success or failure on these peaks. It is essential to have early starts for several reasons as many a climber has had an impromptu bivvy on Crater Bluff after a late start on Cornerstone Rib. An early start will also enable any route-finding difficulties to be surmounted as well as allow a party to be on and off before the heat of the day embraces them.

While single ropes might be fine at Arapiles, Frog Buttress and parts of the Blue Mountains, double ropes are a necessity here. There are several reasons why. The obvious one is that in the face of retreat a greater distance can be covered between anchors. Double ropes used properly also largely eliminates the Z drags that might be formed by a single rope stitching between running belays. Lastly, the rock is often complex with rough edges and double rope technique is good insurance against a single rope perhaps failing over a sharp edge.

A good supply of water is also essential, but carrying too much can slow you down. Try to find places to leave a stash of water for the walk out. The creeks in the ‘Bungles are largely ephemeral, and therefore should not be relied upon as a source of drinking water.

And so, if heavy packs, long walks, big climbs, sometimes extreme route-finding in often unrelenting heat/cold/wind is the go for you, then the ‘Bungles is just the place to experience all these in one day. Bryden Allen summed it up in his early 1963 guide: “One is likely to freeze in a biting wind in the early morning and suffer from heat exhaustion in mid-afternoon.”

But you don’t have to be a masochist to enjoy climbing in this place. Early starts, good planning and a small team will enable you to attain these stunning and picturesque peaks with plentiful time to enjoy the view, get down, and wend your way back to camp. On a fine day you might also end up sharing your peak with the park’s magnificent eagles soaring lazily on the thermals.

Trachyte provides fine, delightful climbing mostly with very good protection but at times has run-out sections. It is also a very absorbent rock featuring great friction with beautiful and varied hues. Please save some weight and leave your chalk bag at home. I have climbed in the Warrumbungles since 1964 and have never used nor needed chalk. Enjoy the natural environment of the national park without despoiling it.

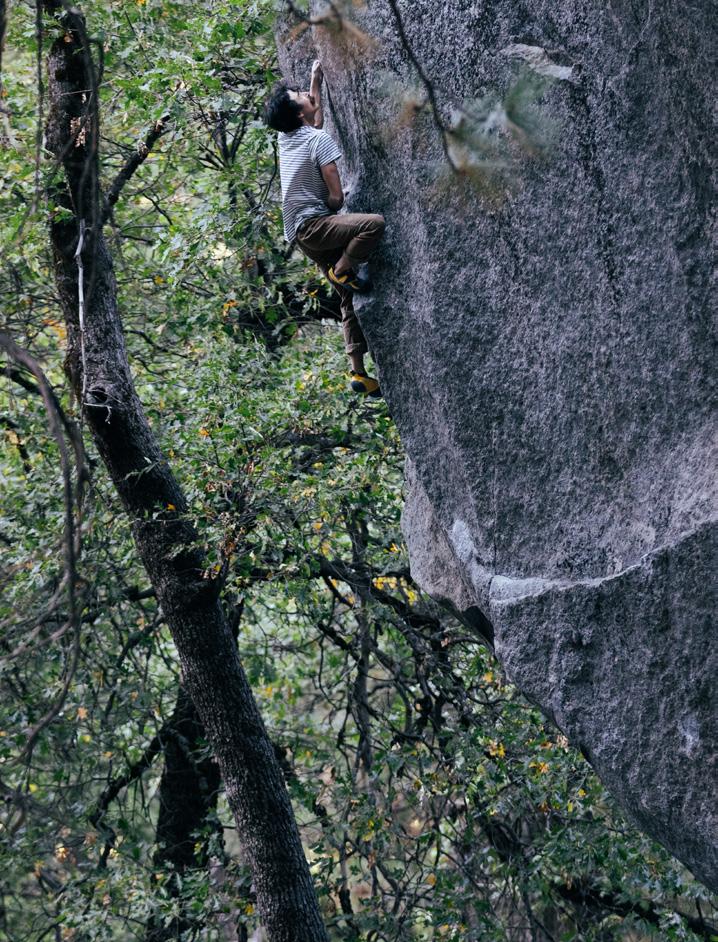

Earlier this year, Aussie climber Ben Cossey made the first ascent of the hardest route at Arapiles/ Dyurite. Light Weight Baby, grade 34, was bolted in the early 1990s by British climber Sean Myles. The 10-metre line waited, unclimbed, for more than three decades—during which time it was referred to as The Sean Myles Project.

Ben first spied the route at the age of 15 and told himself he’d do it one day. A few years on, in 2008, he tried the route for the first time. It wasn’t until a further attempt in 2015 that he started to take it seriously. Life gets in the way sometimes, but with time spent focused on the route over the past few years, Ben sent it in May 2024.

Sure, you may have already heard the news by now, but for our loyal readers who want to know more about the send, Ben’s written up the feat for VL in true Cossey style. With images by climbing photographers Simon Carter and Brecon Littleford, this feature will take you right back there for the journey.

The last great line at Arapiles/Dyurite sat undone for 32 years. It was bolted by British climbing superstar Sean Myles (hence the working title) during a 1992 trip with Jerry Moffatt. The line sat unclimbed—and indifferent to it—as the years passed.

The route optimises everything about Arapilisian/Dyurizian climbing—amazingly schtonkin’ primordial stone, but steeper and more sustained. It had been tickled sporadically throughout its 32 years as a project but no-one had really hunkered down and given it the beans in an attempt to get it done.

It’s in a funny little spot high up on the Mount; had it been in an area with easier access to gawking eyes, perhaps its days as a project may have been somewhat more numbered. Alas, it’s not and instead you have a bonus little Ali-Baba adventure to get there. This, in many ways, adds to the tricksome nature of the redpoint, but equally adds to the wholesomeness of the entire process of getting it done.

The ledge the route starts from is a perfect pic-a-nic spot, worthy of Yogi Bear, and a lovely place to ponder regardless of the route you're trying. Invariably, whenever I’m up there I seem to have forgotten my glasses so the view is perfect and slightly

blurred, giving me the sense of being in a living, panoramic oil painting.

The route itself is a compact little bulge, starting at about 70 degrees overhanging and gently and gradually easing to a vertical-ish headwall. In the lower section the route is comprised of an exactly equal combination of meaty, bum-slappingly and bowel-emptyingly burley underclinging and compressionistic clamping manoeuvres. Once the lip of the bulges’ initial steeptitudes are reached you navigate a section of missionary tick-tacking on crimps leading to a momentary and markedly poverty-stricken rest on a lippy-ripple and spock-pocket.

The last little crux, though, will really weigh the berries in one's basket. A little unwind into a thin seam with the left, a reach to a quintessential bum-crack crease with the right, then the final lurch from a full-frontal perched snuggle to a spreadeagled lunge where you snag the final edge.

Finish the job by inhaling two parmigiana meals, chips and gravy and your friends’ leftovers at the Nati Pub and you have LIGHT WEIGHT BABY!

Words by Allie Pepper

Aussie mountaineer Allie Pepper is attempting to climb the world’s 14 highest peaks without supplemental oxygen in record time. With Broad Peak (8051m), Manaslu (8163m), Annapurna 1 (8091m) and Makalu (8485m) ticked, she and her partner Mikel Sherpa headed up K2 at the end of July–returning just in time to send us an update before VL went to press!

On 1 July, Mikel and I flew into Islamabad, then on to Skardu the next morning. A five hour drive the next day took us to the remote village of Askole, which marks the start of the trek to K2 Base Camp. The trek alone is an adventure of epic proportions. Along the way, you can see Broad Peak and K2 up the Godwin Austin Glacier. When we arrived at Base Camp, I had some catching up to do to get ready for the summit push as I was no longer acclimatised from Makalu. The weather had also not been good, and ropes had not yet been fixed all the way to Camp 3.

Mikel and I had planned to go up the mountain to sleep at Camp 3 for one night before our summit attempt. However, K2 had other plans for us. When we began climbing it became extremely windy, and we were forced to spend the night at Camp 1, hoping

the wind would die down. One night turned into three nights at 6,090 metres. The wind did not abate, but we decided to go up anyway to Camp 2, which was cold and difficult in the conditions. Unfortunately , the wind just did not let up. After two nights at 6,650 metres at Camp 2, the forecast had only worsened, so we decided to come down. Leaving the camp, I could hardly walk, with winds at 80 to 100 km/hour. This first rotation was not ideal for climbing to 8,611 metres without oxygen.

The jet stream continued to hang around the mountain for the next week. Finally, we had news of a weather window around 27 to 29 July. It was time to head back up the mountain. We left a day earlier than most people because I didn’t want to go straight to Camp 2 in a day.

On the 24th, Mikel and I climbed to Camp 1; it took seven and half hours. It was still windy, but forecasts had said it would start to ease the next day. On the 26th we left for Camp 3 around 7:30am. The route to Camp 3 is very steep and technical, including a vertical cliff called the Black Pyramid. It was a long day.

We had planned to leave for the summit the next night on the 27th. However, just as we were ready, we got news that the ropes had only been fixed to the bottleneck at around 8,200 metres. We chose to wait another day; I wasn’t using oxygen and did not want to stand around waiting for rope fixing above 8,000 metres because I knew I would get too cold. We had another rest day at Camp 3 which I assumed would help my acclimatisation. In hindsight, we should have moved to Camp 4 that morning, a few hundred meters higher.

That evening on the 28th at exactly 5:55pm I left the camp to head to the summit. Mikel would follow behind me. I climbed for a couple of hours alone, in front of everyone, until he caught up with me below Camp 4. We had been sheltered from the wind until then, but as I climbed up a vertical section to the camp the wind hit me once again. It was draining my energy trying to keep warm. I continued as Mikel stopped at the camp for a rest. Then I stopped to adjust my buff. For perhaps two minutes I took my gloves off to sort it out. This was a huge mistake as my fingers went completely numb. Mikel caught up to me and I couldn’t talk. He had my mitts in his pack, and I needed them. He helped me put them on, there were a lot of tears as I got the screaming barfies. After around 30 minutes

I could feel my fingers again, and thankfully I have no long-term injury from this short incident.

At 10:08am past the bottleneck, just below where the body of John Snorri came to rest, I stopped. It was in the middle of an ice wall at 8,320 metres. I was going too slow. We had asked climbers coming back from the summit how far away we were. They were all using oxygen, and said around three hours. I knew at that altitude without oxygen, it would take me more than double that time, meaning I wouldn’t reach the summit before 4pm.

This was not acceptable or conducive to survival on K2. I knew 100 percent that I was not able to climb faster; in fact, if anything, the higher I got, the slower I would go. I had to decide. I knew I couldn’t summit without using oxygen in time and come down safely. Usually in this situation I would simply turn around and head back down. However, we were only 300 metres in altitude from the summit. Mikel had come all this way by my side and he would also have to turn around and go down. He was carrying a spare emergency bottle of oxygen for me, as well as the one he had been using since the camp.

I realised I wanted us to stand on the summit together. The weather was amazing, there was no wind. I would have to come back anyway so why not make the summit now as well as later without oxygen?

I told Mikel I would use the spare oxygen bottle to summit. He was very happy as he didn’t want to turn back, but also didn’t want me to continue going up without oxygen. Once I put on the oxygen mask I was able to continue at a solid, steady pace. I was already exhausted, so it didn’t work magic, but it helped a lot. After four hours, we reached the summit. It was so hot I remember thinking it would be possible to stand on the peak in only a swimsuit. I have never experienced that on an 8000er before. With clear skies and a 360-degree view, it was the type of summit dreams are made of. ,

The descent was as expected—difficult and painful. We ran into many climbers who were exhausted and struggling. One way or another, thankfully, we all got back to camp that night. Mikel and I rolled into the tent at 8pm, approximately 26 hours after I left the day before. I was so grateful to be alive, to be able to stop walking and abseiling, and to finally let my body go to sleep.

The next day was beyond epic, getting down from Camp 3 back to Base Camp took around 11 hours. There was high wind, a lot of waiting at abseils, falling rocks and boulders, avalanches and waterfalls where previously there were snow slopes. I thought we would never make it back. Then two days later there was the hike out. More falling rocks and boulders, an avalanche, a horse ride, a bridge destroyed by a flooded river and having to cross sitting in a wooden box attached to a cable.

Am I disappointed that I did not achieve my goal to summit K2 without oxygen? I am blessed to survive, and I am grateful to have made the decisions that led to a successful summit. I am grateful that I did not put anyone else’s life in danger, including my partner Mikel, because of my decisions. I have many lessons to learn for my next climb on K2. It would be a lie to say no part of me is disappointed, but more than anything, I am proud.

At some point most climbers will face an injury of some description… awkward falls, overtraining on the hangboard, or just tripping over at the crag. We’ve all been there and, frankly, it sucks. The desire to mope is high. However, the psychological component of recovery impacts not just how cranky we feel about the situation, but can ultimately influence physical recovery too. Clinical and Performance Psychologist Dr Kate Baecher examines why it’s so important to look after your mental health while your body heals from injury.