FIASCOS: YOUR STORIES BIG WALL CLIMBING IN YOSEMITE SLOVENIAN MTB-ING MAROONED IN THE ARTHURS CAUGHT IN AN AVALANCHE

FOOTWEAR FOR MOUNTAIN ATHLETES

OBSESSIVELY DESIGNED SHOES FOR PERFORMANCE IN THE VERTICAL WORLD

FIASCOS: YOUR STORIES BIG WALL CLIMBING IN YOSEMITE SLOVENIAN MTB-ING MAROONED IN THE ARTHURS CAUGHT IN AN AVALANCHE

OBSESSIVELY DESIGNED SHOES FOR PERFORMANCE IN THE VERTICAL WORLD

FCS Australia is a leader in surfing fins, covers, traction, leashes and accessories.

1%

An Aussie favourite in fishing since 1920. Alvey Side Cast Reels have been and continue to be made in Australia with quality & expertise in mind.

SPRING 2024

The Fiasco Issue

Spero-Wanderer Region

Photo Essay: Parts Unknown

The Cover Shot 14

Readers’ Letters 18

Editor’s Letter 20

Gallery 24

Columns 32

Getting Started: Knots to Know 52

WILD Shot 146

FEATURES FIASCOS

Green Pages 38

Invasion of the Fire Ants 42

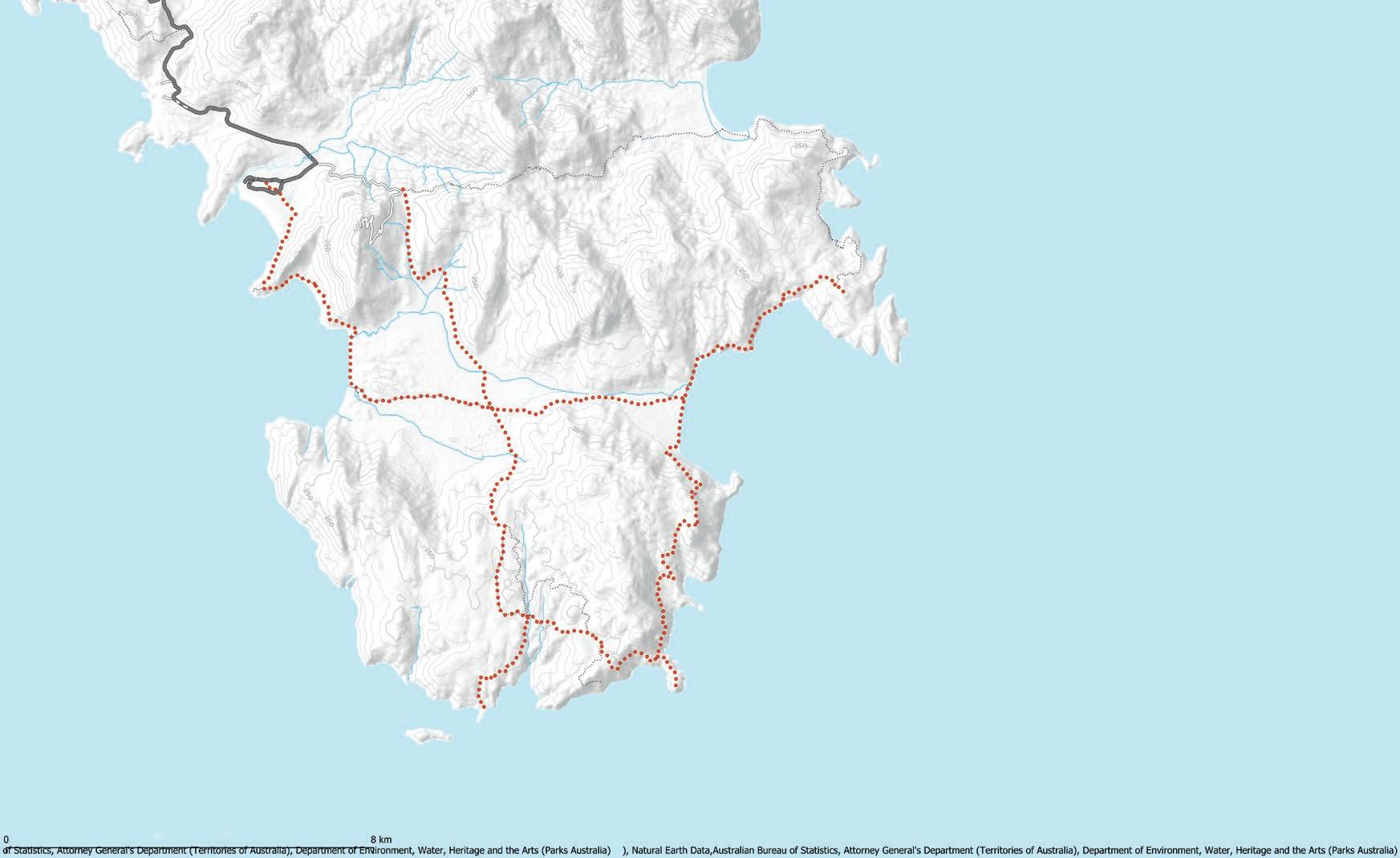

Tasmania’s Spero-Wanderer Region 76

Opinion: Volunteering for Trouble 46

Fiasco Short Stories 54

Marooned in the Western Arthurs 58

Tent Fiasco Stories 66

Profile: Kerry Lowe 48

Climbing Yosemite’s El Cap 68

Caught in an Avalanche 84

Photo Essay: Parts Unknown 88

MTB-ing in Slovenia 96

Off track in the Warrumbungles 106

Skiing and Climbing NZ’s Big Peaks 116

116 Memory Games

48

Profile: Kerry Lowe

In the heart of NSW’s Pilliga region, one man is quietly working on creating a trail network that is not only home to the Pilliga Ultra runnning festival, but that will help the campaign to protect the area.

58

Marooned in the Western Arthurs

When things go wrong, they can go really wrong. In the winning entry of our Fiasco Stories Competition, Chris Newman tells the sorry tale of a gastro-hit traverse of Tasmania’s challenging Western Arthurs.

106

WILD BUNCH

TRACK NOTES

GEAR

Daywalks in QLD’s Sunshine Coast 124

Wilsons Prom Lighthouse Circuit 126

Unsung Heroes 134

Talk and Tests 136

Support Our Supporters 140

Heading back to NSW’s iconic Warrumbungle NP for the first time in more than a decade, Ryan Hansen discovers that, sadly, not everything is once as it was. But that doesn’t mean the ‘Bungles have lost their capacity to inspire.

AUSTRALIAN MADE. AUSTRALIAN PRINTED.

wild.com.au @wildmagazine @wild_mag

subscribe.wild.com.au

EDITOR: James McCormack

EDITOR-AT-LARGE: Ryan Hansen

GREEN PAGES EDITOR: Maya Darby

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT: Caitlin Schokker

PROOFING & FACT CHECKING: Martine Hansen, Ryan Hansen

DESIGN: James McCormack

FOUNDER: Chris Baxter OAM

COLUMNISTS: Megan Holbeck, Tim Macartney-Snape, Dan Slater

CONTRIBUTORS: Grant Dixon, Daygin Prescott, Geoff Law, Anzhela Malysheva, Jenny Stansby, Shaun Mittwollen, Emily Scott, Callum Hockey, Alistair Paton, Bruce Paton, Martin Bissig, Gerhard Czerner, Chris Newman, Johan Augustin, Jeremy Shepherd, Kerry Trapnell, Reid Marshall, Christian McEwen, Craig Pearce

By Ryan Hansen

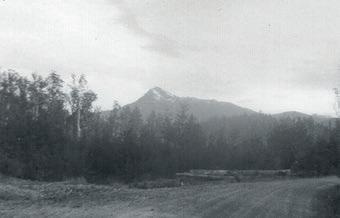

For some time, it’d been our objective to stand where Martine stands in this photo. We’d first spied the mountain a year ago from Mt Exmouth (Ed: Because of the square aspect ratio used for cover images, Exmouth is unfortunately just off the right of frame on the cover; you can, however, see it in the image above), and then we saw it again yesterday from a new for us viewpoint. The peak had occupied our vision for much of today, too; initially as an almost-touchable target, and then, as the regrowth scrub had thickened, as an unattainable, faraway goal. But we’d persisted bashing, stumbling, battling our way ever onwards until, demoralised, we’d slumped to the ground in a clearing below, peering up at its enticing cliffs.

Undeterred, I’d found a way up with surprising ease. Thoroughly impressed by its substantive views, I’d laced it back to camp, refuelled with a rapid cuppa, and returned back up in a proverbial flash for sunset, this time with Martine. As we admired the last of the evening’s rays with a resident rock wallaby, the full-circle nature of our experience hit home: There, just to the right of the setting sun, was Mt Exmouth, where it’d all begun.

You can read more about Ryan’s adventures in the Warrumbungles in the accompanying feature story ‘Times of Change’ starting on p106.

PUBLISHER

Toby Ryston-Pratt Adventure Entertainment Pty Ltd ABN 79 612 294 569

ADVERTISING AND SALES

Toby Ryston-Pratt 0413 183 804 toby@adventureentertainment.com

CONTRIBUTIONS & QUERIES

Want to contribute to Wild? Please email contributor@wild.com.au Send general, non-subscription queries to contact@wild.com.au

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Get Wild at wild.com.au/subscribe or call 02 8227 6486. Send subscription correspondence to: magazines@adventureentertainment.com or via snail mail to: Wild Magazine PO Box 161, Hornsby, NSW 2077

This magazine is printed on UPM Star silk paper, which is made under ISO 14001 Environmental management, ISO 5001 Energy Management, 9001 Quality Management systems. It meets both FSC and PEFC certifications.

WILD IS A REGISTERED TRADE MARK; the use of the name is prohibited. All material copyright Adventure Entertainment Pty Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without obtaining the publisher’s written consent. Wild attempts to verify advertising, track notes, route descriptions, maps and other information, but cannot be held responsible for erroneous, incomplete or misleading material. Articles represent the views of the authors and not the publishers.

WARNING: The activities in this magazine are super fun, but risky too. Undertaking them without proper training, experience, skill, regard for safety or equipment could result in injury, death or an unexpected and very hungry night under the stars.

WILD ACKNOWLEDGES AND SHOWS RESPECT to the Traditional Custodians of Australia and Aotearoa, and Elders past, present and emerging.

[ Letter of the Issue ] OH, THE MEMORIES

Hello James,

Well, I went into town today, and guess what I saw on the rack in the newsagency ... Wild Magazine #191. So I broke down and bought it to check it out. Moving here from Colorado thirteen years ago was a huge culture shock for me, especially as I used to ski back in Colorado twenty times a season.

While I was going through the magazine, I came across your Ed’s Letter on page 18 with the title ‘Great Expectations’, and on it there was a very beautiful photo you took of a skier riding down a nice slope with the sun going down (Ed: It was of Shaun Mittwollen on the Sentinel, Kosciuszko NP). That photo brought back memories of me skiing in the back bowls of Vail, when the sun was going down. My years of skiing all over Colorado, from Keystone (where there is night skiing) to Loveland Ski Resort on the Continental Divide, would make your mouth water, with hip-deep cotton-candy powder, and orange and violet sunsets. The sounds of my skis making turns up in the Rocky Mountains seemed to stop time.

I never thought all that would stop upon moving down here thirteen years ago. But seeing your Ed’s Letter photo made me think back to all the great memories I have of skiing with my friends in Colorado. I’ve wanted one day to go skiing somewhere as nice as that here in Australia, but have had little motivation ... until I saw your photo.

Yeah, we all are aware of global warming and climate change and the effect it has had on our skiing season. But no amount of climate change will ever halt my dreams of making some fresh turns in some beautiful location in Australia.

Keep skiing or stay home, Eddie Prados

Tottenham, NSW

PS I hope you can use this photo of me solo climbing on The Diamond on Long Peak, Colorado. (Ed: We sure can!)

Dear Wild, The article about Hinchinbrook Island (‘Australia’s Jurassic Park’, Wild #192) brought back great memories of our honeymoon in 1990. We kayaked from Lucinda up the east coast of the island and around to Missionary Bay in our 1932 Klepper folding kayak, complete with sail. After packing up the kayak, the ferry from Cardwell to Ramsay Bay picked us up, dropped us off at the start of the Thorsborne Trail, and then took our kayak back to Cardwell, where it was stored until our return.

We then walked the trail, with a day trip up Mt Bowen. Not carrying heavy packs, we did the return trip in about ten hours, arriving back at camp at roughly 4PM. We had no issues with navigation either up the creek or along the tops, as there had been a recent bushfire, but we did end up scratched and covered in black from the banksias.

Not your average honeymoon!

Janette Asche

St Lucia, QLD

(Ed: Thanks for the lovely story, Janette. And you’re right; paddling around in 1932 folding kayaks and climbing Mt Bowen is far from the average honeymoon.)

Dear James,

In reference to ‘Letters to the Editor’ in Wild #192 that just arrived, I don’t think the Social Climbers featured further in Wild because it became the topic of a book; see amazon.com/Social-Climbers-Chris-John-Darwin /dp/0725106808

The book was actually a great ‘everyman’s’ insight into mountaineering, and offered the rest of the country a look into things that Wild readers love! I hope I still have my copy up the back of the bookcase somewhere.

Brian Farrelly Canberra, ACT

SEND US YOUR LETTERS TO WIN!

Each Letter of the Issue wins a piece of quality outdoor kit. They’ll also, like Eddie in this issue, receive A FREE ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION TO WILD. To be in the running, send your 40-400 word letters to: editor@wild.com.au

QUICK THOUGHTS

On Wild’s Facebook post about Editor James McCormack being in Kosciuszko NP in the snow, testing out his Aldi OneZ sleeping bag suit (featured on p137 of this issue):

“I was also out there [that] weekend, and I sure would’ve run screaming if I’d seen that looming out of the night at me!!” DS

EVERY published letter this issue will receive a pair of Smartwool PhD crew hike socks. Smartwool is well known for their itch-free, odour-free Merino clothing, and their technical PhD socks have seamless toes and are mesh-panelled for comfort.

Eddie’s Letter of the Issue will get something special: A Smartwool sock drawer. It’ll include hiking, running and lifestyle socks, enough for anyone to throw out all those old raggedy, holey and often stinky socks they’ve been making do with.

When I first began thinking about a fiasco theme for this issue, I decided my Ed’s Letter should chronicle some of my own outdoors fiascos. Man, I thought, this will be a rich vein for me to tap into. I sat at my desk, fingers hovering at the keyboard, ready to tap out a long list of bungled adventures that had gone preposterously south.

But nothing came. Zip. Zilch. Zero. Give it time, I figured, something will come. But days turned into weeks, weeks into months, and still nothing came. Sure, I have an endless stream of outdoors injury stories: Broken arms, punctured lungs (yes, lungs), a triple-fractured pelvis, a torn ACL ... . The number of broken ribs is up in the double digits. So, too, is the number of times I’ve fractured vertebrae.

But injuries alone do not a fiasco story make. It needs an element of debacle. Or at least, multiple things to go wrong and to compound on each other. And, ideally, things should not just go wrong; they should go comically wrong.

After four months of nothing, a dark thought, decades old, bubbled to the surface. It involved a bright yellow Dolphin torch, you know, one of those massive things the size of a brick. I remembered not using it for illumination, however; I was using it as a pillow. And when I say pillow, it wasn’t in the usual sense of a pillow; I just needed something to raise my head out of the water of the literal stream that had begun flooding where we slept. Flooding. That’s exactly what happened, because once I remembered the Dolphin, all the memories I’d seemingly repressed from that trip came flooding back. I was in first-year uni, and the winter break had arrived. Stuey, Oov and myself had decided to set off to the snow; there was loads of precip forecast, and the skiing looked excellent. But as the date to depart loomed, it became apparent none of us had given this any serious thought. We were students. We had no vehicle. We had no accommodation. And we were broke. The cost of lift tickets, even back then when

they were a fraction of today’s cost, was out of the question. We needed an alternative.

As young Sydneysiders have for generations, we looked to the nearby Blue Mountains for inspiration. The forecast was grim. And being winter, the temps weren’t balmy. The heavy precip down south was heading this way, too; in what proved to be a dramatic underestimate, more than 200mm over two days was predicted. For three young, testosterone-fuelled, foolish teenagers, heading into this maelstrom ludicrously under-equipped—being flat broke, none of us had decent gear— seemed an occasion ripe with adventure. And so we set off to the Grose Valley on what we’d dubbed ‘The Real Man’s Camping Trip’ (and yes, we were being ironic).

We jumped off the train at Blackheath, and set off into the deluge. (We later learnt that nearby Katoomba would receive more than 160mm today; tomorrow it would get 275.) By the time we’d walked the few kilometres to Govetts Lookout, we were already soaked. I had a GoreTex jacket, but Stuey’s and Oov’s jackets were pathetic. None of us had the money for rain pants, either; we wore jeans or trackie dacks.

At the lookout, little of the mist-shrouded valley was visible, but we could at least see Govetts Leap Falls lunging impressively out of the clouds. Down we went, negotiating the steps carved into the cliff; so much water flowed onto us it felt we were in Govetts Leap Falls themselves. But it was only once we reached the base of the falls that we realised we’d bitten off something serious. The creek was truly thumping. Actually, it was raging. It wasn’t long until, at one of the creek crossings, Stuey got swept downstream. A little further on, where the creek flowed through a narrow rock channel, I used a two-metre-long stick to test the water’s depth; it didn’t hit the bottom.

We ended up stopping shy of the Blue Gum Forest. None of us owned an actual tent, so we huddled under my 3x4m tarp. Nor did we have a proper stove; just a tiny solid-fuel tablet one that struggled to warm the instant noodles we brought for dinner.

Meanwhile, the rain pelted down. In the midwinter cold, we were freezing, but a fire was out of the question. Not long after we lay down for sleep, a stream began flowing right under the middle of the tarp. In hindsight, we could have moved position; instead we stayed put, and I simply placed my head on the brick-sized Dolphin torch to keep it out of the water.

We slept more-or-less on the ground, with just cheapie closed-cell mats between us and the dirt. Oov did not have a sleeping bag either, and I shared mine with him, with it unzipped like a quilt. It was saturated, though, with the down clumped into a handful of sodden lumps. We lay there shivering; sleep was impossible. Well, nearly impossible. There were three delicious minutes when I dozed off, until an antechinus scurried in and bit me on the toe. There was no chance of sleep after that. It was the longest night I’ve ever had. By morning, the pounding rain had not let up. We set off, heading back now via Rodriguez Falls. Creek crossings at times seemed almost terrifying. There was one spot where we had to cross fast water above a waterfall. It was genuinely dangerous. Stuey—having been swept downstream yesterday—baulked, pacing the banks like a caged tiger. Coaxing him across took thirty minutes.

Late that afternoon, we dragged ourselves into the pub at Blackheath, where we spent the night recovering. One of us, not me, was so dog-tired and beaten he soiled himself during the night. But here’s the thing: Do I regret this outing? Not one teensy bit. In fact, I recommend everyone have their own fiasco at some stage. I have never learnt more about adventuring in a single trip than this one, and despite it being an utter debacle, I look on it now with fondness. Such fondness, in fact, it seems strange I repressed it so deeply that I almost couldn’t recall it. But it does make me think: What other outdoors fiascos have I repressed? I’m sure there are many. And boy, they must be doozies.

JAMES MCCORMACK

Traditional Owners and graziers have recently won a campaign to stop new oil and gas infrastructure in western Queensland’s Channel Country, which contains some of the last free-flowing desert rivers left on Earth. It’s extremely flat country where any interruption can dramatically alter the water’s path. This image, taken in March 2024 after a wet summer in the tropical north, shows the monsoonal rains as they travel hundreds of kilometres down the Georgina and Diamantina Rivers and Cooper Creek to the Lake Eyre Basin. From the air, these unique braided channels resemble arteries, which is fitting for the life they bring to this typically dry and isolated area.

by KERRY TRAPNELL

Shaun Mittwollen starts down Mt Carruthers’ north face, September, 2023. Despite this being one of the worst Aussie snow seasons on record, if you were willing to head into the NSW backcountry and earn your turns, quality skiing could still be found, even in spring. And don’t be fooled by those bare patches; the snow ran unbroken all the way to James Macarthur Creek deep in the valley below. by JAMES MCCORMACK

meganholbeck.substack.com meganholbeck.com @meganholbeck

[MEGAN HOLBECK]

The wonderful four-day Yuraygir Coastal Walk deserves, even in the depths of winter, a AAA rating: Accessible; Adventurous; Amazing.

Four days, seventy-odd kilometres of stunning coastline, five kids aged nine to fifteen, two adult twins, a strong southerly headwind, and an iffy July forecast. It doesn’t sound like a classic school-holiday good time. But then throw in the magic: Perfectly positioned tiny towns with accommodation ranging from budget to boutique; supplies from pub grub to pasta packets; light packs; warm beds and showers at each day’s end. Giving people—people who mesh—the time and space to talk about the things that get crowded out in normal life, aided by the rhythm of movement, exercise and nature, and supplemented by shell finding, ball throwing, singing … and lollies.

The Yuraygir Coastal Walk in northern NSW traverses coastal heath, rock ledges and kilometres of hard-packed sand from Angourie to Red Rock. It feels more remote than it looks on the map, especially in the middle of winter. Although it passes through three towns, and four-wheel drives are allowed on some beaches, we only saw four other walkers—mostly we had the whole place to ourselves.

There was plenty of other life. Rosella flocks decorated the coastal shrub like bright baubles, pelicans clumped on beaches, and pairs of oystercatchers chased each other in the receding waves, reflected in the thin mirror of water. Whales and dolphins swam in the distance; massive cuttlefish lay washed up on the beach, bone-white and alien.

The southerly headwind whipped both the clouds and the sand into changing shapes, transforming the ocean into messy, pounding surf. The atmosphere switched from foreboding to inviting with the clouds and light. One moment the scene had the stark beauty of an approaching storm; the next it looked benign and swim-worthy.

There were hours of talking; connection in every combination. The teenagers passed kilometres holding hands, talking, singing. Whenever a camera appeared, they turned around and walked backwards, bums first, an effective protest against photos. The twelve-year-olds raced, ignored advice, splashed through waves, listened to music, and generally tried out their new, high-school selves. Jasper floated: He strolled along uncomplaining, stopped to examine stuff, ran ahead, then joined a group for games, comic relief or to prod for reactions. Laura

GIVING PEOPLE THE TIME AND SPACE TO TALK ABOUT THE THINGS THAT GET CROWDED OUT IN NORMAL LIFE .. .”

and I talked about all the things we don’t get a chance to usually, and learned who the other was again, how we each are now.

Despite the forecast, we stayed mostly dry, except for a good soaking at lunch on the second day. A couple of soggy, cold hours of walking brought us to Minnie Waters, where Guy—my slow-arriving husband/ fellow walker/driver/caterer/logistical support—dispensed hot chocolate, beer and the keys to caravan park cabins, followed by kilograms of Yamba prawns, hot chips and Sara Lee cake.

We stayed in a beautiful apartment overlooking Brooms Head Beach and a huge room at the Wooli Hotel Motel; had pizza in the pub and prawns on a picnic table. Jasper reached for his ball and fell in the Wooli River, minutes after the

boatman told him about the resident sharks. “Help!” he squealed, clambering uneaten onto the rocks seconds later.

Except for the ten minute burst of competitive whinging that began each day’s walk, there was surprisingly little complaining. Even when I added three kilometres to our longest day by following the beach past the motel, there wasn’t a meltdown. Instead, there was muttering about my navigation, demands to see the map, then all was forgotten during negotiations for the best bed.

The walking was not difficult and rarely boring. Some sections along rock ledges took care, time and thought; the NPWS notes give warnings about the dangers of big seas and high tides. The upside of winter’s wind and rain meant the sand was firm and we kept moving. In warmer weather, it’d be a different experience: You’d stop for swims; the sand would be soft. But in general, this walk would be fine for keen, fit(ish) walkers from eight to 78, depending on how it was done. Staying in the beautiful national parks’ campsites along the way would make it feel wilder and more adventurous, while doing our way made it fun, possible and amazing for our ragtag mob.

This accessible adventure wasn’t expensive, and the money we spent went straight into the local economy. It didn’t require much organising, equipment or effort; we used existing infrastructure; and we had next-to-no environmental impacts. (A few shells may have been taken—I tried.)

If we’re looking for ways to introduce a wide range of people to the joys of nature, while allowing them to test themselves gently and develop a connection and appreciation for the world around them, experiences like these are a good place to start.

It’s always tough to decide what gear to take out on any given adventure, but especially so when you’re a participant on the reality show Alone.

We go into the wild to immerse ourselves in nature. To shrug off the stress and routine of everyday life by reconnecting to our primal home. For many of us, it’s also to break out and challenge ourselves on different levels. However, hardly any of us take the challenge as far as having to rely solely on foraging and hunting for food as the participants in the popular TV franchise Alone must do. (Ed: If you’re not familiar with Alone, which is available online for free on SBS at sbs.com.au/ondemand, ten people choose ten items, and then head into the wilds to see how long they can survive). I find the series mildly fascinating, but ultimately frustrating.

Despite the foreboding soundtrack to the repetitive camera pans, a signature of all episodes, the initial overseas episodes held me with the landscapes, plants, wildlife and those participants who were competent. But my frustration levels grew with the antics, and the apparent lack of mental preparation and self-reflection of the less-capable participants.

An ability to handle loneliness is obviously critical for anyone getting close to lasting the distance, as—also obviously— is their ability and luck in gleaning enough sustenance. Not so obvious to success is the choice of which ten items they are allowed to take from the specified list (Ed: One of my frustrations with Alone is that they don’t tell us explicitly on the show what ten items have been chosen by each participant. You can, however, find out what the specified fifty items are that participants get to choose from at history.com/shows/alone/articles/gear-list)

For someone with a practical bent and a fascination with gear, I find this a timeless dilemma, as indeed I do for any

outdoor escapade. While such decisions aren’t usually make or break for personal adventures, they can certainly be for Alone participants. I’ll now do my best choosing what I would take.

Quick, waterproof shelter is vital, so a big tick for the tarp. Securing it well, and for numerous other tasks, parachute cord also gets the tick. Staving off hypothermia and ensuring adequate sleep is also vital, so in goes an appropriate sleeping bag and—because you don’t have to carry it—I’d go for the heavier, bulkier but more functional when wet,

HARDLY ANY OF US TAKE THE

CHALLENGE AS FAR AS HAVING TO RELY SOLELY ON FORAGING AND HUNTING FOR FOOD.”

option of a synthetic one. While comfort is also important for a good sleep, I’d reluctantly leave out a sleeping mat and make do with dry vegetation for padding my bony hips and insulating me from the cold ground.

Fire is essential for cooking and warmth, so the fire lighting flint must go in, and that brings in a difficult choice. For long-term wood supply—in the hopefully cosy and confined space of my more permanent shelter—I’d need to cut firewood. Of the choice of permitted cutting implements to choose from—axe, two choices of saw, a hunting style knife (limited practicality) and a multitool— the axe is the first item I’d choose. But

After all, that is our natural heritage. [TIM

axes have the downside of requiring a lot more energy to use, so if the location favoured the making of a log cabin-type shelter, I’d be tempted to also include a saw. Finally, for its usefulness in performing other tasks, a multitool would be a must. A steel cooking pot completes the list of essentials needed whatever the environment.

That leaves two items, and they would have to be purposeful for catching food. As all locations seem to be located by large bodies of water, a fishing line and hooks go in for aquatic hunting, leaving the choice for terrestrial hunting between a bow (with arrows) and snare wire. Neither are particularly humane, but before making this choice I think I would have to do a lot of practice with them to see what worked best for me. Having hunted and trapped in my youth, I know for sure that a rifle is by far the least cruel means of hunting, but that’s off the list. So, there’s my ten.

But wait, when you’re all alone, darkness is not your friend. So out goes the saw, and in its place is a thing that doesn’t warm, nourish or shelter you, that would only be used occasionally but could be very handy when you really needed it during those long, lonely hours of darkness: a headlamp.

The show is contrived for sure, and for all the drama of each individual’s successes and failures in using their limited resources, it’s inevitable to conclude that one thing that would make the task a lot easier, more than any amount of equipment, would be to do away with the biggest contrivance of all, that of being alone, and instead be allowed to have a compatible companion or better still a tribe of them.

[DAN SLATER]

Back in 2017, in his very first column, Dan wrote about the use of PFCs within the outdoor equipment industry. In this first of a two-part column, he’s checking back in to see what progress has been made.

When I first started this column in 2017, 36 issues ago … well, for a start I had no idea it would still be going beyond 2018, never mind 2024. You see, I originally made a list of 16 hot topics related to environmental responsibility within the outdoor-equipment-manufacturing industry, and I assumed that once I’d covered those topics, I’d return from whence I came, leaving this page available for more deserving text. Back then, Wild was bi-monthly, so my issue plan would last until about the end of 2018. During that time though, the role of editor changed, and when I chatted to the new helmsman James in 2018 regarding the impending closure of my body of work, he got on his knees (over the phone) and literally begged me (Ed: Yes, it’s true! ) to extend it to keep writing about gear in general. I was surprised, and it took me a little while to re-programme my brain and pivot from strictly environmental considerations to a broader gear chat.

I digress. The very first topic on my original list, and subject of my second column (the first being of an introductory nature) was Durable Water Repellency (DWR), and the widespread use of perfluorocarbons (PFCs) in their manufacture. PFCs break down into toxic PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyls) but no further, and stay in the environment forever, primarily reaching humans through our drinking water. The health risks aren’t fully understood, but ingested carbon has long been linked to cancer. Indeed, the World Health Organisation has declared PFOA, a type of PFAS, a Group 1 human carcinogen.

Acceptable PFAS levels are regulated in different ways globally, with different types (there are thousands) having different levels. For instance, PFOA is regulated in Australia at 560 nanograms per litre (ng/l). To the average consumer, this may be just a bunch of acronyms and what seems like a very tiny number, so perhaps the best way to judge this is by comparison. In the US, the limit for PFOA and PFAS combined is 4 ng/l, and this is still well above the US advisory health limits. In Canada, the limit for all PFAS combined is 30 ng/l. So why is Australia’s limit so high? That would

YOU’D BE FORGIVEN FOR THINKING THE CURRENT ACCEPTABLE LEVELS ARE UNACCEPTABLE.”

be beyond the scope of this column, but you’d be forgiven for thinking the current acceptable levels are unacceptable.

I also talked about Greenpeace attacking the industry’s use of PFCs in a 2015 report, and the industry’s optimistic response as they promised, company by company, to reduce the length of the offending carbon chains from eight molecules to six. The shorter-chain molecules are less damaging when they break down in the environment, but they break down quicker so are less effective on the garment. In fact, C6 solutions were quickly also deemed unacceptable. What I didn’t mention back then was a ‘hidden’ source of PFCs—the waterproof

membrane itself. The original Gore-Tex membrane was ePTFE (expanded polytetrafluoroethylene), which requires PFCs in its production. Greenpeace released another report in 2021 applauding Gore’s intention to introduce a new membrane based on ePE—PFC-free expanded polyethylene—to replace ePTFE by the end of 2023. Gore unfortunately didn’t meet this deadline due to “product development and scaling challenges”, so their ePE membrane is currently running alongside the old ePTFE one in their range. However, their new deadline—end of 2025—seems more promising. It should also be noted that since 2016, many companies have moved away from Gore-Tex in favour of their own proprietary membranes, many of which use alternative PFC-free technologies.

I went on to list some greener alternatives to carbon-based DWRs that were being considered, among them Schoeller’s Ecorepel and Archroma’s Smartrepel Hydro. According to the Schoeller website today, Ecorepel is used in products by Black Diamond, Vaude and Icebreaker, however none of their websites returns any results for ‘ecorepel’. Archroma does not list any outdoor brands as partners on its website.

I finished up with an optimistic “Hopefully a safe and effective solution is not far away.” Well, was it? This column has been very science-based, and if you’ve made it this far, I applaud your staying power, but how does this translate to the brands we know and wear every day? How have they evolved over the past decade to combat the problem? We’ll find out in Part II, next issue.

Introducing the new Australian Made XRS™ Connect Handheld UHF CB Radio, XRS-660

Building on the market-leading innovation of GME’s popular range of XRS™ Connect UHF CB Radios, the Australian Made XRS-660 offers several exciting new features, including being the first Handheld UHF CB Radio to feature a Colour TFT LCD screen, providing the ultimate Handheld radio display for all environmental conditions – even in full sunlight.

Boasting Bluetooth® audio connectivity the XRS-660 can wirelessly connect to an extensive range of third-party audio accessories, providing users with new and improved ways to stay connected and built-in GPS functionality ensures the XRS-660 offers true location awareness without relying on a smartphone to provide GPS location data.

Also featuring rugged IP67 Ingress Protection and a MIL-STD810G rating, the XRS-660 is our toughest and most advanced Handheld UHF CB Radio yet.

SUBSCRIBE FOR 2 YEARS &

WILD IS NO ORDINARY MAGAZINE. Since its establishment in 1981, Wild has been the inspiring voice of the Australian outdoors. It is a magazine of self-reliance and challenge and sometimes doing it tough. While it is not necessarily hardcore, what it certainly is not is soft-core. It is not glamping. It is not about being pampered while experiencing the outdoors. Wild does not speak down to experienced adventurers. And Wild does not look on conservation as a mere marketing tool. For over four decades, Wild has actively and fiercely fought for the environment. Campaigning to protect our wild places is part of our DNA. Show that you care about stories that matter by subscribing to Wild.

(RRP $299.95)

On the trail, sleep is a must. For the best experience, you need enough rest. The Tensor™ pad’s Spaceframe™ construction and internal design provide stability, quiet comfort, and weight distribution. The new internal layer helps minimise drafts and add warmth.

• Spaceframe™ baffles offer unparalleled stability and weight distribution, using low-stretch, die-cut trusses that eliminate springiness

• A new ultra-thin film within internal architecture adds R-value (R 2.5)

• 100% bluesign® certified, 20D premium recycled polyester fabric

• 7.6 cm of quiet and supportive cushioning without the usual ‘waterbed’ feel

• Included Vortex™ pump sack provides easy and fast inflation, saves breath at elevation, and minimises moisture entering the pad

• Laylow™ zero-profile, multifunctional, micro-adjustable valve is flush to the pad and allows fine-tuning of comfort

• Packaging is made from recycled materials and is 100% recyclable

For just a one-time payment of $95, you’ll get a Nemo Tensor Sleeping Mat worth $299.95 plus 8 issues of the magazine worth $119.60, for a total value of $419.55! TERMS & CONDITIONS

Offer available for Australian and New Zealand residents only. Offer is available while stocks last.

- Never miss an issue - Great gift idea - FREE delivery to your door - Save up to $49.45 - Get the mag before it hits the newsagents

A selection of environmental news briefs from around the country.

EDITED BY MAYA DARBY

Wayilwan Country

Resource companies questing for gold threaten a precious wetland ecosystem.

Healthy rivers and wetlands are essential for native wildlife, Aboriginal cultural heritage, local communities, and a diverse range of industries—from floodplain grazing to tourism and recreational fishing. The rivers and wetlands of NSW are under extreme stress after decades of catchment degradation, water-course diversion, unsustainable water extraction, and climate change.

Over the past century, the Murray-Darling Basin has experienced a dramatic decline in wetlands, waterbirds and native fish populations due to a massive increase in the volume of water extracted for irrigation.

The iconic Macquarie Marshes—home to the Wayilwan People, who know the wetlands as Wammerawa—are one of the only semi-permanent inland wetlands in the Murray-Darling Basin, and are teeming with life. Unique, rare and endangered water birds like brolga, magpie geese and painted snipe find abundant nesting spots and fertile foraging grounds in the intricate patchwork of ecosystems that make up this complex, interconnected landscape. These incredibly biodiverse ecosystems regularly support 20,000 water birds, and can sustain hundreds of thousands of birds after flooding.

Recognised for its importance as a breeding site for migratory birds which fly from Alaska and Siberia to breed there, almost 20,000ha of the 200,000ha

Macquarie Marsh area is designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Significance.

But there is something shiny under the heavyclay marsh soil that mining companies want—gold. Mining-exploration licences were issued by the NSW Government in the heart of the fragile wetland. The Nature Conservation Council put pressure on the decision maker and were hours away from serving court papers to challenge the exploration. Thankfully, the regulator overturned their decision to allow exploratory drilling, and while this came as a relief, Australian Consolidated Gold Holdings have been asked for more information to support their application. The fight isn’t over yet.

It is unthinkable that mining can even be considered in this critically important site. The Nature Conservation Council is calling on the NSW Government to cancel all current mining-exploration licences within the 200,000ha designated as the Macquarie Marshes, to ban the granting of miningexploration licences in this area in the future, and to improve public notifications so that communities are informed and aware of exploration applications in their area and of what their rights are.

To learn more, head to nature.org.au/protect_the_ macquarie_marshes

ANNA GREER

Nature Conservation Council

IT IS UNTHINKABLE THAT MINING CAN EVEN BE CONSIDERED IN THIS CRITICALLY IMPORTANT SITE.”

At peak population, the Macquarie Marshes support as many as 500,000+ birds.

Credit: Leanne Hall

WAMMERAWA/ MACQUARIE

MARSHBY THE NUMBERS: Total area: 200,000ha

Ramsar—year declared: 1986

Ramsar criteria met: 6 (out of 9)

Ramsar site area: 19,850ha

Native species:

Birds: 233

Mammals: 29

Frogs: 15

Reptiles: 60

Fish: 11

Nationally threatened species: 5

Credit: M Hrkac

Regular bird population: 20,000

Peak bird population: 500,000+

GunaiKurnai Country

Snow gums (Eucalyptus pauciflora) are an iconic species of the Australian High Country. These stunning trees are culturally and ecologically significant and are a keystone species of the alpine region. Unfortunately, snow gums are facing a double threat to their survival from both changing fire regimes and dieback. Friends of the Earth Melbourne are hosting a Snow Gum Summit in Feb 2025 that will bring together land managers, academics and anyone interested in the future of this iconic species. The summit will explore what’s required to ensure the survival of snow-gum woodlands, and put the issue firmly on the state-government agenda. To get involved, head to melbournefoe.org.au/snow_gum_summit_2025

CAM WALKER, Friends of the Earth Melbourne

Gadigal, Malijangapa & Wangkumara Country Soil microbes are microorganisms like bacteria, fungi, archaea, viruses, and protozoa, and are crucial in maintaining healthy, balanced ecosystems. In dryland ecosystems—think 70% of Australia—soil functions are particularly critical in maintaining the wellbeing and resilience of the landscape from the ground up. As part of her research at UNSW, PhD candidate Jana Stewart is working alongside Wild Deserts to better understand how trophic rewilding (reintroducing locally extinct ‘ecosystem engineers’ like bilbies and bandicoots) may influence below-ground soil diversity. Stewart’s investigations offer exciting findings in an under-researched field and will provide crucial insights on management approaches in ecosystem restoration. Follow along on Instagram @loveyouleafyou or email jana.stewart@student.unsw.edu.au

JANA STEWART, University of New South Wales

Meanjin

The Queensland Government’s South East Queensland Regional Plan will see up to 40,000 new homes built each year to accommodate six-million people by 2046. Urban sprawl threatens critical habitat for koalas, owls, gliders, quolls and other endangered species. Our housing solutions need not mow down their homes for ours. Queensland Conservation Council is calling on the government and opposition to take urgent action to protect this native habitat prior to the election. New development needs to build up, not out, to ensure our precious ecosystems are safeguarded. To learn more, head to: queenslandconservation.org.au

JEN BASHAM, Queensland Conservation Council

takayna

Readers of Wild will remember Al Bloom’s story earlier this year about endangered Tasmanian masked owls in takayna/Tarkine. Well, for now at least, some masked owls in takayna can be at peace, thanks to the pausing of logging in late June in a remote area of forest at the junction of the Arthur and Frankland Rivers. The pause is a result of 39 days of courageous defenders staging the largest community defence against logging in Tasmania in over a decade, with 29 citizens being arrested. But with logging and mining continuing elsewhere in takayna, masked owls—along with eagles—are still losing their forest homes. Masked owls have been consistently recorded and even photographed (which is incredibly rare) in the proposed toxic tailing dam site by Chinese Government miner MMG, as well as in recent protest sites in the Florentine Valley and Frankland River forests. Calling pairs have been heard in these forests almost every survey night, underscoring how essential these forests are to their territories. Head to @bobbrownfoundation on Instagram to hear the calls of the masked owls, or to bobbrown.org.au to learn more.

ADAM BURLING & JENNY WEBER

Bob Brown Foundation

lutruwita

Tasmania’s national parks have long been in developers’ sights. Here’s the latest on how their alarming proposals are progressing.

Development in national parks is an ongoing issue around Australia, with private developers proposing projects on public lands that are ecologically damaging, that frequently restrict public access, and that reduce wild character. Nowhere is this more so than lutruwita/Tasmania. The island state’s World Heritage-value wilderness has long been eyed off by developers as the holy grail— free or cheap land that is incredibly spectacular.

In 2014, the Tasmanian Government launched an “unlock the parks” policy, creating an expression of interest (EOI) process for developers to propose projects on reserved land. To counter the perception of land-banking by proponents, the process requires proponents to give regular updates on their proposals’ progress. Despite this, much information remains hidden. But a recent Right to Information (RTI) request revealed a plethora of errors from the agency overseeing this EOI process, and a number of projects have been either radically altered, withdrawn and resubmitted in secret or withdrawn altogether. Despite heavy redactions, some information has been revealed. Here’s what we learnt:

CRADLE BASE CAMP EXPERIENCE: The Office of the Coordinator General’s (OCG) website showed this project had been withdrawn. However, in reality a deal was made between the Tasmanian Walking Company (TWC) and the OCG to withdraw the original project on the proviso another project in the same place with a different name be accepted. The Cradle Base Camp Experience was out, the Lake Rodway Hut Walk was in. A decade on though, and the project’s details remain swathed in secrecy. Leaked plans, however, show the accommodation and living nodes will spread out over an area of 400m2, joined by boardwalks with other associated infrastructure. All private, and all on public land.

WALLS OF JERUSALEM LODGE WALK: The RTI indicates this EOI has “minor variations” to reduce the project’s scale and impact. Details of these variations were hidden, however it’s rumoured the proponent, TWC, has reduced the number of planned lodges within the Walls of Jerusalem NP from two to one, presumably due to ballooning construction costs.

OVERLAND TRACK LODGE EXPERIENCE: No progress for these five luxury lodges has been demonstrated, other than the claim that a market-research project is underway. That’s right, a decade in, and the TWC is only now doing market research—this is a case of land-banking, pure and simple.

MARIA ISLAND EXPERIENCE: The RTI indicates the Adkins House project has been withdrawn and replaced with a revised EOI, the ‘Maria Island Experience’. Wild Bush Luxury has been silent on why the Adkins House rebuild was removed from their plans.

SOUTH EAST CAPE LODGE WALK: A letter in the RTI shows that Wild Bush Luxury withdrew this proposal for a lodge-based experience in the wilderness zone at South Cape Bay over six months ago. The OCG website failed to inform the public of this withdrawal, presumably to save face for the government.

SOUTH COAST TRACK LODGE WALK: The proponent claims “targeted consultations” have occurred; none have been with the Aboriginal community, who have ancient spiritual connection to this stunning area. The project is for six luxury lodges—some within metres of Tasmania’s most significant cultural sites. Wild Bush Luxury claim they’ll submit documentation for assessment in the next 6-9 months.

HALLS ISLAND/LAKE MALBENA: The proponent has a requirement under the EPBC Act to complete a comprehensive landscape-wide assessment, to be done in consultation with relevant land owners and Aboriginal groups. Despite this, the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania has not been approached since this was made a condition of assessment.

In sum, not one project of consequence has begun operations in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area due to staunch opposition from community groups and conservationists. Despite the lack of progress, however, the Tasmanian Government maintains their policy is a success while obsessively hiding information from the public. Learn more at protectournationalparks.org

DAN BROUN

Protect Our National Parks

THE TASMANIAN GOVERNMENT MAINTAINS THEIR POLICY IS A SUCCESS WHILE OBSESSIVELY HIDING INFORMATION FROM THE PUBLIC.”

MORE INFO:

LAKE MALBENA

Lake Malbena is a pristine lake in the Walls of Jerusalem NP, formed by glacial activity in the last ice age. It has remained largely unchanged since, other than through Aboriginal landscape management and the odd fire.

In the middle of the remote lake lies 10ha Halls Island, which has experienced no development other than a small, 70-year-old heritage-listed shack used by bushwalkers for decades. But there’s a proposal for an exclusive, helicopter-accessed ‘standing camp’—cute wording for luxury huts—on the island, which would allow at least 270 helicopter flights a year into a wilderness area that currently has none. The skies here are the domain of the endangered wedgetailed eagle, and that’s how it should remain.

The red fire ant is described as one of the world’s worst invasive species. In Australia, the ants are taking over new areas, and experts fear that the battle to control them has already been lost. It’s bad news not just for the country’s ecology, but also for bushwalkers and anyone else who engages in outdoor activities.

Words JOHAN AUGUSTIN

Photography JOHAN AUGUSTIN (unless otherwise noted)

Atruck speeds down the highway, creating a gust of wind that makes the sugarcane stalks quiver. These fields of sugarcane stretch as far as the eye can see, and a closer look reveals mounds of earth near the robust stalks that bask in the sunlight around the road.

“They use the stalks as a ‘body’ to get direct heat from the sun,” says Greg Zipf. ‘They’ refers to an unwelcome guest that Greg’s sugarcane fields outside Brisbane have received, one that’s proving tough to get rid of: the red fire ant.

An insect native to South America, the red fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) has spread to many new areas, including Australia, over the past few decades, hence why it’s also called the red imported fire ant.

Greg, who is carrying a container of the ant poison Indoxacarb, provided by the Queensland Government, walks with me along the cane field’s edge; within about 100m, he spots six ant nests.

“Six months ago, there were no nests here,” he says, adding that the significant floods earlier in the year likely helped the ants—which clustered together to form ‘rafts’—move over long distances.

We’re accompanied by Reece Pianta from the Invasive Species Council, an environmental organisation founded in 2002 with a mission to raise awareness about the widespread problem of imported pests and weeds that run amok, threatening Australia’s native species. The group now advocates for far stricter biosecurity laws.

“We’re pressuring the government to do more about fire ants,” says Reece, adding that the ants are “the worst invasive species in Australia. They’re a superpest!”

The problem is that ants are capable of quickly spreading to new areas, and just because an area is deemed ‘ant-free’ doesn’t mean colonies aren’t living underground where they’re out of reach of ant-tracking dogs.

Reece explains that the queens can fly up to 32km to form new colonies, while humans—through transportation activities—unknowingly assist the ants, for instance, transporting them via trucks. It’s crucial, therefore, that compost material from, for example, sugarcane, is treated to prevent further spread of the pest.

These treatments are subsequently expensive—a cost that farmers like Greg must bear alone. “It’s not our fault that the ants spread. It’s the government’s responsibility, and they should pay us for spending our own time on this,” he says.

The ants have been present around Brisbane for about twenty years, so it’s not a new problem, but it has proven to be a persistent and challenging one—one requiring relentless work.

“We must treat the land twice a year, and never give up if the ants are not to return,” says Greg.

Despite the numerous mounds on Greg’s sugarcane fields, no ant activity is visible. However, this quickly changes when Reece kicks a nest with his boot. The nest swarms with ants and eggs just beneath the dried layer of earth. To better observe the ants’ activity, Reece places a white piece of paper within the nest.

By the time Reece lifts his hand again, about thirty ants have swiftly climbed onto it. As he attempts to brush them off, they sting him en masse; the resultant ‘fiery’ pain Reece experiences

shows why the ants have the name they do. “Aargh, it hurts a lot,” says Reece, wincing. His hand quickly swells up with numerous red marks.

The attack illustrates why it’s crucial to combat this new invasive species in Australia. “They are very aggressive,” says Reece. “[And they] continue to sting until they have exhausted all their venom,” hence the importance of removing red fire ants quickly. What’s more, the ants attack anything edible in their path, including insects, bird eggs, even other ant species, and they also pose a threat to larger native animals and livestock.

“Our iconic animals,” says Reece, “like koalas, platypuses, and echidnas will be on the fire-ant menu.”

The unwelcome guest also poses a danger to humans, who can suffer allergic reactions from the venom. In the United States, many people have died from fire ant stings in recent years (see sidebar), a trend that experts don’t want to see in Australia.

Anthony Young, a lecturer in crop protection at the University of Queensland, walks with me through a park on the outskirts of Brisbane, pointing out ant nests in a few sunny spots. Children play in a nearby schoolyard, and some visitors have a picnic on the grass in the park. The few fire-ant colonies previously seen in other states, such as New South Wales and Western Australia, have been eradicated, but in Queensland the problem is so widespread that it may be too late to reverse the trend. “My son has already been stung by fire ants,” he says.

According to Anthony, the government has realised too late that the ants are a serious threat. “We really need to act now,” he says. Large, coordinated campaigns are necessary, but currently it appears the ants are winning the race. “It looks hopeless—we need a game changer.”

That game changer is more funds.

“The current eradication program needs to double or triple, at least”, says Nigel Andrew, an entomologist at Southern Cross University. The funding required, he says, to eradicate the red fire ants needs to be “200 to 300 million a year. We are at half of that currently.”

First discovered around Brisbane in the early 2000s, red fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) are believed to have arrived by ship from South America. Despite the name, they’re not red, but more copper-brown in colour, and are relatively small, just 2-6mm. Nonetheless, they’re extremely aggressive, and can cause significant harm to humans, wildlife, and livestock.

The species has spread to other countries such as South Korea and China, and in the United States, the invasive ant is now present across one-third of the country, costing it around $7 billion USD annually. More than 80 people have died in the US as a result of stings.

The species can spread approximately 5km annually in Australia, and there are currently ant nests on 8,000km2 in Queensland, of which 7,000km2 have been treated so far. If left undisturbed, the species could potentially spread over 97% of Australia’s area.

Modelling by the Queensland Government indicates that in southeast Queensland alone, fire ants would impose costs of about $45 billion over 30 years. In Australia, they could cause an extra 140,000 medical consultations and 3,000 anaphylactic reactions a year.

Sources: Invasive Species Council, National Fire Ant Eradication Program

IMAGES - CLOCKWISE FROM TOP

Anthony Young finds ant nests in a park just outside Brisbane

Ants and eggs

Pustules resulting from imported-red-fire-ant stings.

Credit: Murray S Blum

A raft of fire ants floating on floodwater. Credit: Invasive Species Council

Nigel explains that due to the nature of the aggressive ant, it will “dominate other species, kill off pollinators and remove predators.” That can also lead already-endangered species to go locally extinct.

The current eradication plan ends in 2027, and it must demonstrate its effectiveness before receiving additional funding, according to Reece Pianta. At the moment, the funds are being distributed by federal and state governments via the National Fire Ant Eradication Program.

“The goal is to eradicate fire ants by 2032,” a spokesperson for the National Fire Ant Eradication Program told me, without clarifying what will happen when the program runs out in three years. “Eradicating fire ants is no small feat,” the spokesperson said, “but our dedication remains steadfast. While many countries have given up, Australia continues its fight.”

The effort to keep aggressive fire ants at bay is crucial if Australia’s outdoor lifestyle is to remain the same, according to David Bell, President of Bushwalking NSW.

“Fire ants have the potential to be one of the worst pests ever seen in this country, worse than cane toads. If they break containment lines, they [could] spread to nearly all of the continent. It has the potential to radically change the way we recreate in outdoor areas,” David says.

And any outdoor activity would be at risk. “Bushwalkers camping near fire-ant nests would be affected, as would people walking through areas where ants are present. We’ve already seen outdoor activities cancelled or suspended on the Gold Coast.”

What can be done to lower the risk of being stung by fire ants when out in the bush? Is there anything one can do to treat the skin, if stung?

“The best way to avoid being stung,” says David, “is to leave the area immediately and report the infestation to the relevant authorities as soon as possible. If the stings worsen, people should go to a GP or a hospital immediately, particularly if they develop an allergic reaction.”

One aspect that makes fire ants particularly problematic for bushwalkers and other outdoor enthusiasts is that fire ants prefer to build their nests in open areas, and not so much in closed forests. “Unfortunately, these open areas,” says David, “are also where people like to camp. If in an open area where fire ants could occur, [it’s] best to conduct a careful ground sweep before setting up tents.”

But those ground sweeps only help if members of the public know what they’re looking for. “Education for the community on how to recognise fire ants and what to do is also very important.”

This isn’t going to be an easy problem to tackle, and most other countries have failed in their efforts. It’s going to take commitment, and hard work. “Governments need to keep up with eradication efforts,” says David Bell, “and not drop the ball ... with funding and regional support.” It’s also crucial that landowners report known or possible sightings of nests and cooperate with the authorities.

Time will tell whether these efforts will prove successful. One thing we do know, however, is that inaction will prove costly for farmers, for outdoor enthusiasts, for the broader public, and for the environment in general. W

LEARN MORE: Head to the Invasive Species Council website at invasives.org.au/insect-watch/red-imported-fire-ant

CONTRIBUTOR: Sydney-based journalist Johan Augustin focuses on environmental and travel-related topics.

We Use the Gear We Sell.

Whether it is bushwalking, climbing, trail running, or exploring the world’s great mountain ranges we are out there doing it and can’t wait to help you choose the right products for your next adventure.

Head out into the bush enough, and eventually you’ll find what you’re looking for: strife.

Photography

It’s not like, when we wander into wilderness, disaster is the objective. But it’s tempting to think that, sometimes, maybe it is. Particularly when you consider the ironic, wry, and weirdly twisted psyche we Made-in-Oz bushwalkers are afflicted with.

What better story to tell, after all, than an utter fiasco encountered, then escaped from? The drama! The hilarity! Beer and skittles!

But then there’s death. “People die out here all the time,” said the driver taking my group to a West MacDonnells eight-day offtrack wander in Central Australia. Later, I did a Google search for death on the Larapinta. Sadly, sure enough.

Unfortunately, the line between the catastrophe averted—the fiasco—and the catastrophe not good and not averted—Lucifer’s trilogy of death, disaster and destruction—like the line between love and hate, can be very, very thin indeed. There but for the Grace of God—or Satan or whoever makes the decisions—is a phrase that has ricocheted around my brain many a time post-fiasco.

But life is lived more fully when we push the envelope, go for the PB, broach the unknown, live on the edge a little: Live life, don’t scroll through it on TikTok.

Both God and Satan know I’ve had my fair share of fiascos. None have veered into the truly life-threatening, though my wife might argue the point. Top of her mind could be a nationalpark-rangers’ evacuation of my teenage son and I from Kosciuszko National Park in 2020 (see Wild 175), due to a massive bushfire raging its way towards us.

Plenty of these fiascos were characterised by some excruciatingly bad decision making. Not that I knew they were vapid at the time (hindsight being such a clever dick). I didn’t have the experience, or perhaps the wit, to know that. I am, after all, a ‘people’. Yes, people are at the heart of nearly all fiascos. That’s because people are stupid. That includes me; it’s not like I’m immune to the type of stupidity that results in fiascos. Of course, not every fiasco is borne of stupidity; sometimes it’s sheer dumb luck. Here are some examples of both the stupid and unlucky varieties that I’ve witnessed or been at the heart of:

THAT IS THE DARK ALLURE OF THE EXISTENTIAL PACKAGE WE PURCHASE: GAMBLE WITH EXISTENCE, THEN CHEAT IT.”

It is inevitable, then—if we are doing it properly, that is— that this approach will lead to mistakes; to, ultimately, fiascos. Maybe that is the dark allure of the existential package we purchase: Gamble with existence, then cheat it. That feels like a very short-term game to me, however. Russian roulette.

Which is where risk management steps in. Every excursion into nature involves risk. The more off the beaten track we go, the greater the risk, hence the greater the likelihood of fiasco— it lurks, as we know, around every snake-infested, loose-rock‘paved’, precipitous, radically exposed corner. Our risk appetite is balanced by what we do to mitigate risk: Some good shoes and some waterproof kit, maybe; having various means of navigation; route choices (eg doing the Eastern Arthurs but not, if we aren’t feeling up to it, climbing Fed Peak).

- Kosciuszko National Park: An early-days-in-my-outdoors-education bushwalk with my then four-year old son, in what is a relatively benign part of the park. Because it was a supposed marked trail in Nichols Gorge near Blue Waterholes, I thought, “No need for a map.” But as I lost the track (missed some barely-there trail markers), the map (and some not-yet-acquired common sense) would have been handy. I ended up carrying my son on my shoulders through off-track trash until I found my way, gratefully following a bemused but kind young couple who I clung to like a life raft. Getting my four-year old back to the trailhead was a deeply emotional relief that I will never forget. Scars, these being scars my son and wife are more than happy to poke a sharp stick at, too.

- Kanangra-Boyd National Park: One winter, many years ago, I was all excited about going lightweight, but a summer sleeping bag in sub-zero temps, where snow wafted down, water bottles froze and butane stoves went cactus, was easily the least-comfortable night I’ve ever spent outdoors #gearfailure #never_again. It

felt like I was freezing to death. I now sometimes over-compensate but I’ve never been cold since. More scars.

- Mt Kaputar National Park: I went on an escapade with, let’s call them, Cain and not-so-Able. The latter took a 5-star, heavy, metal Trangia with full accoutrements, metal drink bottle, alcohol and about the heaviest boots I’ve ever seen. The boots ended up delaminating, the walker ended up dehydrating, half his pack went into Cain’s and mine, and the walk was aborted, with me left shaking my head asking “How did I end up here?”

- West MacDonnells: After five days of wandering, the group I was in ascended the Giles Massif (see Wild 189). It didn’t go well for one walker. He blew up big time as we approached the peak. We split his pack, allowing him to walk carrying close-to-zero weight, which seemed to do the trick. But the following day, on the plain, he said, “All good to carry weight.” That didn’t last long. Luckily, we weren’t on the hard scrabble rock that dominates the area, because he soon fainted face-first into a sandy beach. Cue ye olde splitting-of-the-pack-contents strategy. Scars, although this time not mine.

- Western Arthurs (potentially Australia’s single biggest repository of fiascos, rivalled only by the West MacDonnells): Towards the end of a massive day, fatigued and clearly in diminishing-concentration mode, I—in a strategy decided on to evade a brutal storm about to hit the range—made a significant error, leaping rather than stepping down some rocks, and sprained my ankle in an excruciatingly pain-full—literally breath-taking—fashion (see Wild 190). Somehow, I managed to regather and hobble my way down Moraine K. It’s the closest I’ve come to pressing my Garmin inReach’s SOS button. Painful scars. (Oh, and speaking of calling for help in the Western Arthurs, over a couple of days around Xmas 2023, there were about five evacuations. A failed one was when the chopper was called in by a concerned party who saw an ‘’old man’’ struggling (no, not me). The chopper duly flew in, found the guilty ancient person, who said thanks for your concern, but all good, and marched right on.)

- South West Cape: Bamboozled in a prison-like maze of melaleuca, I tried to squeeze and fight my way through the thicket up the back of Noyhener Beach. The SW Cape track is not marked

on its western and northern sides, however in the melaleuca, some kind souls have taped a path through it. But the route is bedlam, deceiving and very navigationally demanding. All pad options need to be interrogated before committing to them. In one section, I did the classic loop de loop, exiting the jungle precisely where I’d entered it. Frazzled and, yes, scarred.

- Bimberi Wilderness/The Legend of Faceplant Dave (see Wild 186): Mired in the wilderness, at the tail-end of a five-day on/offtrack Brindabellas excursion, Dave and I not so much lost as battled a snarling, utterly ferocious set of vegetal tsunamis. Sometimes we made 600m in an hour. Oh, and we were pummelled by rain, too. If we stopped, we’d freeze, and we sure as hell wouldn’t reach the trailhead. While the wild was beautiful, our senses of humour were stretched taut. Scarred, but soothed somewhat by medicine provided that night in a Cooma pub.

THERE IS AN EXISTENTIALIST PARADOX in wilderness immersion. We are born in freedom. Freedom to make choices. Freedom to stuff it up. And we do so, willingly, rapturously even, like moths compelled by the allure of the wild’s brightness. And we are compelled also, thanks to the sick voyeur in us, to hear the stories of fiasco. We find them riveting, like watching a car crash.

What we sometimes forget, though, is that they are always there. They, the fiascos, roil underneath us on every adventure. Like sharks in the surf, they move in silence, benign until they are not. Their threat is also their wonder, however, and there is a thrill attached to the revelations of the unknowns faced, negotiated, resolved.

Ultimately, I wonder if the real fiasco is made up of the episodes where the proverbial hits the fan, or if the real delusion we carry into the wilderness is that we think we are off for adventure, when, actually, we are just volunteering for trouble. W

CONTRIBUTOR: Sydney-based Craig Pearce escapes, whenever possible, the wilderness of the corporate canyons for the non-anthropocentric society of snakes, snow gums and wallabies.

fees

In the heart of NSW’s Pilliga region, one man is quietly working on creating a trail network that is not only home to the Pilliga Ultra running festival, but that will help the campaign to protect the area.

Words EMILY SCOTT

Photography CALLUM HOCKEY

Kerry the caretaker? Kerry the trail maker? Kerry the bushwalker? Kerry the local legend? Kerry the humble, quietly spoken and dedicated friend of woodland forests in the Pilliga?

I was first introduced to Kerry Lowe, 72, President of the Tamworth Bushwalking and Canoe Club, not in person but in story, the type of story that evokes senses of intrigue and of awe and of mythic out-of-this-world-ness. For some time, until I’d actually met the man, I forgot most of the events and contents of these stories. The feelings associated with them, however, remained, and Kerry seemed to me like a faraway mystical character, almost difficult to believe in, but heart-warming to hear of.

I could, at this point, write some fun facts about Kerry’s history, his life—and I will get to that. But the nub of the story, in short, is this: Over fourteen years, Kerry has created approximately 54km of trails through Barkala Farm, a nearly 5,000ha property, some of which is farmland, but most of it wild Pilliga woodland in the heart of Gomeroi/Kamilaroi Country in NSW’s North West Slopes region. These trails are home to the annual Pilliga Ultra, a festival of running and sports activism designed to support local people in their efforts to attract tourists and to protect this environmentally significant area.

Given the fact Kerry doesn’t live here—he divides his time between a camp on the farm and his home on the outskirts of Tamworth, which is roughly a 200km drive away—and given the rocky, chossy terrain and scattered escarpments of the Pilliga, this trail building is quite a feat.

On the map, the Pilliga lies where the green near the coast, the green of the hinterland, the green of rain, slowly fades out west and becomes scarcer. The land turns vaster, more desert-like. The Pilliga is not the thick bushland of the Wollemi, nor the boundless plains of the Strzelecki Desert. It’s the woodland in-between, and has its own unique beauty. “Most of it’s wilderness,” says Kerry, which is what has driven him here, and what keeps him driving back.

Kerry describes the Pilliga as similar to the Blue Mountains but on a smaller scale. Small, however, doesn’t mean insignificant; in fact, it can emphasise the microsystems at play, and the intricacies and the delicate in life. Kerry describes gorges, canyons, and cliffs, and estimates there are 1,000 caves on Barkala Farm.

But the Pilliga is under threat. Mining-exploration permits and underground disruption began here in the 1990s; ever since, the unheard voices of the Gomeroi people, and of others who oppose mining here, have been suffocated and drowned out by the broad reach of the resources giant Santos. In fact, trying to understand the campaign to protect the Pilliga is like stepping inside Tara June Winch’s fictional-yet-realistic story The Yield, a story that almost uncannily mirrors what’s happening here, a story of the politics of black and green relations, of the blurry ethics of much-needed funding for the local footy field available only by the same companies destroying the local environment, of the history of colonised Aboriginal nations, of the narrative of creating local jobs.

AFTER THAT INTRODUCTION TO KERRY that had more to do with storytelling and less to do with the actual man, I finally met him in person at Pilliga Pottery, a café and working ceramics studio on Barkala Farm. It was early May, 8AM sharp; the leaves had already turned, the fire was still smouldering, the rain was soft.

We crammed into Kerry’s LandCruiser, and then travelled down a dirt track into the bush. Kerry had set up his camp for a few weeks on a transition between cleared farming land and dense bushland. We collected metal rakes and gloves and set off on foot for some trail maintenance. With Kerry in front, he showed us—rather than telling us—how to clear the paths.

Kerry’s presence exudes modesty; I quickly learned that as much as Kerry is a character, he is understated and unassuming.

MOST OF IT’S WILDERNESS,” SAYS KERRY, WHICH IS WHAT HAS DRIVEN HIM HERE, AND WHAT KEEPS HIM DRIVING BACK .”

As such, he creates a sense of ease, trust and confidence. We trailed the trails attempting to mimic his use of the tools, noting the attention to detail he takes, from the use of dead wood to line a particular side of the path, to the building of mounds for erosion prevention, to raking the looser rock to the side, and to the general clearing of overgrown plants from the singletrack.

As we moved, Kerry explained how feral goats damaged the land, how their movements, mass-reproduction rates, and migration have thinned out the bush of what once was—up until recently—dense scrub. I saw our role as humans here as being one that sits somewhere on the spectrum between enabling destruction (from goats, from mining, from tree clearing) and accessibility (of witnessing the wild, of breathing it in, of sitting in it). We are often destroying, or often well-meaning and good intentioned yet still somehow destroying.

Environmentally, culturally, recreationally and historically significant, the Pilliga sits in Gomeroi country and borders the Wayilwan nation. The word ‘Pilliga’ is thought to have derived from the word bilaar meaning spear, or balaar meaning sheoak (casuarina) in Gamilaraay language; both seem relevant given the woodland is scattered in she-oak—a dense wood with straight growth—which is ideal for spearmaking. Native white

cypress and ironbark forests blanket the landscape, thickened with dense lower scrub covering the floor of the forest.

The Great Artesian Basin, one of the world’s largest underground freshwater resources, lies under the Pilliga; mining for fossil fuels here has the capacity to pollute it and jeopardise its health, thus threatening local ecosystems. Now I could at this point bang on about the Pilliga being home to many threatened bird species, like the barking owl, glossy back cockatoo, greycrowned babbler, brown treecreeper, speckled warbler, varied sittella, little lorikeet and turquoise parrot. It’s home to threatened mammals, too: the koala, squirrel glider, black-striped wallaby, Corben’s long-eared bat and the Pilliga mouse.

As I said, I could bang on about all these species, but I won’t. Instead, I’ll tell you what Kerry—a man of fewer words than me—said when I asked how he started creating trails at Barkala: “Walking around.”

I pried for further details, and he mentioned exploratory bushwalks, during which he wandered and pondered. He looked over topographic maps and created routes; the contour lines and his knowledge of high points and potential lookout locations meant he knew the cliffs, tabletops, caves and areas of special vegetation. In steeper parts, he chose routes that had less chance of erosion, using zig-zag techniques to slowly climb to higher peaks.

Kerry is no amateur trail creator, having created trails for thirty years. After spending just a few hours with him on the trail with a metal rake, I realised how much manual labour building these trails must have entailed. Even Kerry acknowledged this himself, admitting he’s “starting to slow down these days.”

Beyond Cradle Mountain, Tasmania’s Overland Track winds south, providing public huts for all walkers, without sky-high fees

Kerry maintaining the trails

Kerry and Hilary McAllister (For Wild Places CEO) pausing for a breather while discussing the Pilliga Ultra

On 13-15th September, 2024, a weekend of running, community and sports activism will occur at Barkala Farm, a roughly 33km drive north of Coonabarabran, NSW.

Run in one or all of the events (10K, 20K or 50K). And take in the Pilliga’s beauty and diversity, and learn from the local community about why this landscape is so special. Learn more at pilligaultra.com

THE BITS ABOUT KERRY I SAID I’D GET TO are as follows: He first arrived at Barkala Farm fourteen years ago, when his girlfriend was captured by the potter’s studio. Since that time, Kerry hasn’t ever properly left, and has been camping in the bush there nearly every second week. After my first meeting with him, we spoke again over the phone; he told me he’d set up camp at ‘Split Rock Valley’. His setup was clean and cosy. Kerry is a man you can still write a letter to; in any case, he doesn’t have an email. He spends most of his time out of range; we contacted each other on a landline graciously facilitated by the property’s owner.

Kerry has been bushwalking for fifty years. During that time, his paid work has differed across varying roles in conservation and consulting, computer business and tour guiding. Since retiring ten years ago, Kerry has kept himself busy; when not at home in Tamworth and president-ing the local bushwalking and canoe club, he is often touring; K’gari island, and Kangaroo Island have been recent destinations.

SANTOS’S FACT SHEET ON THE NARRABRI GAS PROJECT in the Pilliga makes no mention of the Gomeroi people in its ‘about’ section; instead, it offers a narrative of the area’s history as a ‘working forest,’ using language that suggests a pre-existing path of destruction, and it alludes to an idea that adding mining to the mix of farmland and forestry isn’t that far-fetched or controversial. It wouldn’t be that disruptive, it seems to say, because it’s disrupted already.

But the multi-layered significance of the Pilliga represents environmental and cultural aspects worthy of protection. That doesn’t mean, however, that environmental and cultural significance alone should be a prerequisite for protection. This idea speaks to the lens of a capitalistic, post-colonial world—prove to me it’s worth something, or I’ll damage it, take it, exploit it, sell it.

When I asked Kerry about the mining in the area, I could hear the distinguishable trait of disgust in his voice: “It’s not warranted,” he said. He’s written multiple letters to government departments voicing concerns about the ongoing mining and the attempts to expand it in the area. Noting that the mining will impact valuable resources, including sources of water, Kerry quoted from a document on the gas project, stating the impacts will continue to affect the Great Artesian Basin for 1,400 years. That takes a bit to sink in.

CONTRIBUTOR: Linking the personal to the political, Emily Scott hikes and bikes but can never seem to escape the day job social worker in her.

To me, Kerry reflects the essence of responsible exploring. He seems to acknowledge that this land is not completely untouched, that there are many years of connection with country here that is not ours. That we can use this privilege to campaign against the exploratory permits of the mining industry that propose to tear down the sense of wild that exists here. That the ‘wild’ isn’t necessarily our wild; that we can explore quietly and respectfully. W

with Christian McEwen

Knowing how to tie the right knot for the right occasion is a skill every adventurer should know. Wild Earth Ambassador Christian McEwen shares six of his favourite knots.

Knot-tying is one of those skills that will never go out of fashion, especially in the outdoors. You'll become more resourceful and ready to jump into action when you have the knowledge to tie a bunch of super versatile knots.