Celebrating

Autumn Off the Beaten Path in the Kootenays

Our Endangered Puffins

A Tale of Four Elephants

- Lauren DeStefano

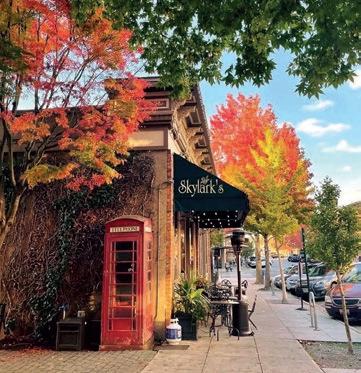

Autumn Off the Beaten Path in the Kootenays

Our Endangered Puffins

A Tale of Four Elephants

- Lauren DeStefano

Brett Baunton is a photographer who believes images can make a difference. His work is featured in National Geographic and National Parks magazines, and is utilized to promote the causes of many conservation groups. He enjoys boating, hiking, and skiing, making Bellingham the perfect home base. Learn more at brettbaunton.com.

Abram Dickerson is the owner/principal at Aspire Adventure Running. As a husband, a father, and an entrepreneur, he attempts to live his life with intention and purpose. He loves mountains and the friendships that result from the suffering and satisfaction of running, skiing, and climbing in wild places.

Amy Eberling, the Founder and Executive Director of The Salish Sea School, is a passionate educator who spent a decade teaching high school biology. She created The Salish Sea School to foster a deeper connection between students and the marine environment, establishing programs focused on marine biology, conservation, and research, to ensure that the next generation values and protects the Salish Sea ecosystem.

Cathy Grinstead was born and raised in northern California, where she spent her summers backpacking in the Sierra. In 2018, she retired from veterinary practice and moved to Bellingham to explore a different part of the world. She enjoys hiking, outrigger paddling, and snow sports and loves all that Bellingham has to offer!

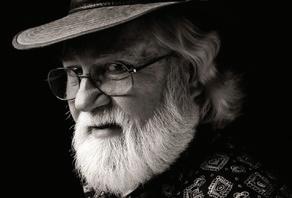

Embracing the uncertainty of true adventure has been a driving theme in Bob Kandiko’s lifestyle. Choosing “the new and the unknown” has not always been easy, but the rewards have been huge. He is planning more adventures.

People can find Bellingham-based artist Gretchen Leggitt ’s massive mountain murals throughout the West and her mountain stickers can be spotted on the backs of Subarus worldwide. Leggitt is the creator of Hydrascape Stickers, cofounder of non-profit Paper Whale, and producer of Fire & Story and Noisy Waters Mural Festivals.

Alan Majchrowicz is a landscape and nature photographer living with his family in Bellingham, WA. His images have appeared in advertising campaigns, product design, tourism brochures, books, magazines, and calendars. Learn more at alanmajchrowicz.com.

John Miles climbed and hiked in the North Cascades for nearly 50 years. He also taught environmental

studies at Western Washington University, taking students “into the field” as often as possible, and what a field it was. In retirement, living near Taos, New Mexico, he hikes and skies the Southern Rockies. His latest book is Teaching in the Rain: The Story of North Cascades Institute (2023).

John Minier is the owner and lead guide at Baker Mountain Guides. Originally from Alaska, he has a deep appreciation for wild and mountainous places. Since 2004, he has worked across the western U.S. as a rock guide, alpine guide, ski guide, and avalanche instructor.

Andy Porter is a Skagit-based photographer and teacher who fell in love with the North Cascades long before he laid eyes on them. Studying maps of Oregon and Washington while plotting a PCT Trek, the North Cascades captured his imagination. View him at andyporterimages.com.

Paul Tolme, the Journalist on the Loose, is an outdoors writer, awardwinning environmental journalist, and blogger for Cascade Bicycle Club. He lives with his wife in a Seattle houseboat crammed with bikes, skis, snowboards, kayaks, and paddleboards but no regrets. His work can be seen at paultolme.com and cascade.org/news.

Dennis Walton had the wonderful opportunity to work internationally as a geologist, allowing him to live in and travel to many corners of the world. His interest in the world’s many cultures fueled his passion for photography, which continues to this day. View his photography at denniswalton.zenfolio.com.

The author and publisher of Hiking Snohomish County (2024) and Hiking Whatcom County (2023), Ken Wilcox is a long-time Bellingham resident, writer, and professional trail planning/design consultant. He writes about parks, trails, Northwest history, and travel, and frequently posts his work via Substack at www.kenwilcox.com

Robert Wrigley is the author of twelve books of poetry. Winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award, the Poet’s Prize, and a Pacific Northwest Book Award, he lives in the woods of north central Idaho and spends as much of his time as he can outdoors.

September is upon us. Lit by the incandescent light of summer’s golden glow, it offers us ripe opportunities to roam the high country, exploring alpine gardens buried by snow for nine or ten months of the year. It’s a sweet month and calls us to the endof-summer party to savor the languid light on a landscape that resembles a transcendentalist painting.

But October is a bittersweet month. Summer is a fading memory. Winter, the elephant in the room (lots of elephants in this issue), looms large in the shadows of the evenings, each one coming sooner—and lasting longer. The wind, done with its summer frivolity, begins to gnaw on the land with ever-sharpening teeth. For lovers of the North Cascades, this is prime time. Temperatures are mild, autumn’s vibrant colors illuminate

meadows and forests, and the bugs are gone.

Sure, we all love the cloudless summer days, lazy bees in the wildflowers, and the exhilaration of a dip in a glacier-milky lake. But, in autumn, the mountains reveal their artistic side. Alpine meadows are painted orange, purple, and red. The first snows, dream-like, remind us of childhood days when the cold meant nothing, raising questions that have yet to be answered. The combination of outrageous colors and the freshness of the shifting seasons make for ideal conditions—golden chances to indulge our benevolent passions in high places. Memorable days. Evocative nights. Powerful fuel for the fire of the soul.

Of course, the knowledge that the door is closing, that these alpine paths will soon be buried under a mantle of snow (perhaps already dusted white) for the next nine months, also stirs the soul. There is a need to gather it in, while the gathering is good.

In this issue, we celebrate the turning of the seasons and the joy of high places. Autumn is a state of mind, an embracing of change. The eternal cycle reminds us of the ephemeral nature of all we hold dear, a bigger-picture view of where we

Our days are numbered, and our good fortune, my

For trail runners, there’s nothing like the Blanchard Beast. This 10-mile-long race winds through the forests of Blanchard State Forest, located south of Bellingham on Blanchard Mountain, on October 19.

The Beast is just one of many running events staged each year by the Greater Bellingham Running Club (GBRC). This venerable and enthusiastic group of running enthusiasts has been celebrating our local trails for almost a half century. The folks at GBRC—which traces its origins back to 1976—are passionate about running. The group hosts ten races annually and enjoys weekly runs (open to any who want to join) all year. “GBRC is an all-inclusive club, welcoming all levels and abilities of walkers & runners,” says board member/ treasurer/race director Larry Lober.

“Participants range from less than a year old in baby joggers to individuals well into their 80s.”

Among the club’s annual events are such local favorites as the Chuckanut Foot Race, the Lake Padden Relay, and the Whatcom Falls 5K.

The Club is all about community. Their annual Turkey Trot event benefits the Bellingham Food Bank, and the group also contributes to the YMCA’s Girls on the Run and Trail Blazers programs. Together with Haggen Foods, they offer college scholarships for local runners and provide shoe vouchers to low-income high school athletes.

GBRC made it through COVID by being adaptable—and creative. “At the onset of

COVID, a few of our runs were canceled,” Lober explains. “We then adopted a virtual format where runners ran the courses independently and submitted their times, and top finishers were recognized with awards.”

After 48 years, GBRC has become stronger than ever, with almost 700 members. And with their emphasis on inclusivity and community, it’s easy to see why.

More info: www.gbrc.net

Starting beside the Salish Sea on the Lummi Nation and ending in downtown Bellingham, the Bellingham Bay Marathon has come to be seen as a “rite of autumn” by locals and runners from around the world alike. Along the route, runners are treated to magnificent views out over Bellingham Bay to the San Juan Islands and east to the towering peaks of the North Cascades.

First run in 2007, race day offers something for everybody with marathon, marathon relay, half marathon, 10k, and 5K routes. The race is a qualifier for the Boston Marathon and is certified by USA Track and Field.

Since its inception, the Bellingham Bay Marathon has benefitted the community that hosts it with 100% of the net proceeds going to the Bellingham Bay Swim Team, Whatcom FC Rangers soccer club, and other local youth programs.

“We are excited and grateful to once again have PeaceHealth/St. Joseph Medical Center as our presenting sponsor and race-day firstaid provider,” says Race Director Marc Blake. PeaceHealth has been the presenting sponsor of the Bellingham Bay Marathon since 2019.

This year’s Marathon will be run on September 22.

More info: www.bellinghambaymarathon.org

There’s something about the Skagit River that inspires poetry. There can be no denying this fact when you consider the stirring words of Gary Snyder, Robert Sund, Philip Whelan, Jack Kerouac, Tom Robbins, and many others. Keeping this sacred tradition alive is the biennial Skagit Valley Poetry Festival, coming to La Conner, WA, October 3-5. Featuring a plethora of poets, the festival has become a destination event over the years, evoking the magic spirit of the Skagit.

This year’s event highlights the creators of the recently published Cascadia Field Guide, a multi-discipline (poetry, art, and prose) book that celebrates the natural world of the Pacific Northwest. All three of the editors of this groundbreaking book will be on hand: Elizabeth Bradfield, CMarie Fuhrman, and Derek Sheffield, along with poets like Tim McNulty (Salmon, Cedar, Rock & Rain), Sati Mookherjee (Ways of Being), and Robert Wrigley (The True Account of Myself As a Bird ), our featured poet in this issue. The Skagit River Poetry Foundation took root in 1998, the result of a conversation between leaders from seven rural school districts in Skagit County. These leaders hoped to create a non-profit project that would support high literacy standards with the arts; poetry was the natural vehicle. From 1998 to the present, more than 50 Skagit, Island, and Whatcom County teachers have hosted resident poets each year. More than 400,000 students have had the experience of playing with words while reading and writing poetry one-on-one with experts.

The organization’s board, comprised of school and community volunteers, has honed activities that infuse diverse voices into area classrooms from September through May. They bring poetry to rural communities that reflect diverse multi-ethnic and multi-generational populations, viewpoints, and history.

The culminating event for this in-class work is the biennial Skagit River Poetry Festival, which was started in 2000 and is held every other October. Students have the festival poets to themselves on the Friday of the Festival from 9 am-2 pm, after which the public is invited to savor poetry readings at various venues around La Conner.

More info: www.skagitriverpoetry.org

As an introduction to the golden spectacle of our glorious autumn larch forests, the Blue Lake Trail provides easy access to a lovely lake (indeed, it is very blue) cradled in a dramatic basin. The aforementioned larches are radiant at the end of September and the beginning of October. The hike is short—only 2.2 miles each way—and is a feast for the eyes for its entire length. The grade is forgiving (only 1100 feet of gain), and once at the lake, you’re treated to views of the magnificent Early Winter Spires and Liberty Bell rising above nearby Washington Pass. A cautionary note: The Blue Lake Trail is uber popular, especially during larch season. Try to come mid-week and get an early start to minimize the crowds.

Trailhead: Between mileposts 161 and 162 on the North Cascades Highway (WA-20), three miles east of Rainy Pass. Northwest Forest Pass required.

Here’s a grand undertaking: an unforgettable multi-day backpacking excursion into a remote corner of North Cascades National Park. The views from the Copper Ridge Lookout Cabin, 10 miles in, are as good as it gets, but the price of admission is somewhat (pardon the expression) … steep. You’ll climb some 5500 feet all told, up and over Hannegan Pass, down to the Chilliwack River, and then up to the ridge. Once aloft, the wandering is magnificent, and the views are sublime: Baker and Shuksan, Redoubt, Challenger, Whatcom Peak, the Pickets…the list goes on and on. You’ll enter the National Park when you reach the Chilliwack—the designated campsites within are strictly permitted. Most permits are snatched up when they become available in March, but 40 percent are made available on a first-come, first-served basis. These can be picked up at the Glacier Public Service Center in Glacier.

Trailhead: Turn left on the Hannegan Pass Road (#32), just past milepost 46 on the Mt. Baker Highway (WA-542), and drive 5.5 miles to its end at the Hannegan Pass Trailhead. Northwest Forest Pass required.

The short hike up Winchester Mountain to the venerable lookout cabin that adorns its summit is a bucket list proposition at any time of year. But it’s especially beguiling in the autumn when orange, gold, and magenta hues paint the subalpine meadows. The hike—only 3.5 miles roundtrip with 1300 feet of elevation gain—is the easy part. Navigating the rough and tumble road to reach the trailhead is the real challenge, requiring a high-clearance vehicle for sure, and maybe 4WD. Some folks choose to park at the Yellow Aster Butte Trailhead (good luck finding a spot!) and walk up, sparing their vehicle’s undercarriage and their central nervous system. From the trailhead at Twin Lakes, the climb is straightforward and delightful, with non-stop views of the surrounding peaks. Once on top, gaze upon the magnificent Border Peaks and north into Canada. Trailhead: From the Mt. Baker Highway (WA-542), turn left on Twin Lakes Road (#3065), 13.5 miles east of Glacier. Follow this (if you can!) for 7 miles to its end at Twin Lakes. Northwest Forest Pass required.

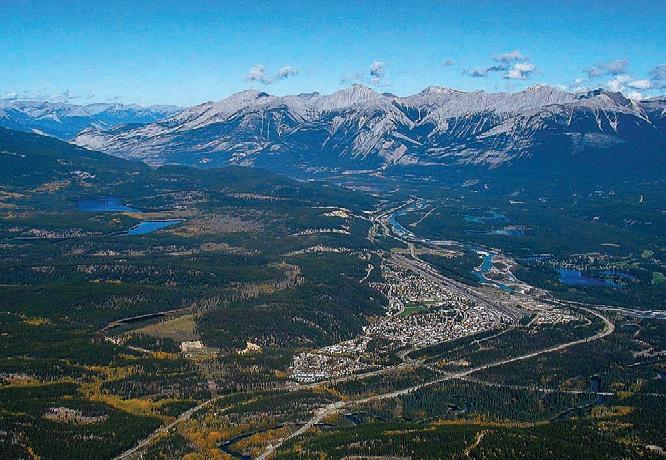

Themountains of British Columbia are justifiably world famous for their rugged beauty and isolation, stretching in range after glorious range across the vast province, which is larger than France and Germany combined. British Columbia is a mountain lover’s dream come true.

If the words ‘Larch Madness’ have you racing for your gear, then you’ll love the Kootenays.

The province’s southeast corner is home to the magnificent Purcell and Selkirk Ranges; together with the Monashees, they are part of the greater Columbia Mountains. These ranges, along with the western flanks of the Rockies, lie within the region known as the Kootenays. But the Kootenays are more than just lofty wild peaks clad in glaciers. Its numerous valleys contain large fjord-like lakes and quaint little towns with vibrant art communities. Because the nearby and more famous Canadian Rockies draw most of the tourist crowds, the Kootenays remain relatively quiet and unknown. Outdoor enthusiasts visiting the Kootenays will find them refreshingly unspoiled.

The Purcells and Selkirks, while nearly abutting each other, are geologically distinct and visually different ranges. Together, they contain two national parks, numerous provincial parks, one wilderness conservancy, and enough impressive peaks and glaciers to enthrall even the most discerning mountain aficionado. Also, vast stretches of wild wilderness, all of which could easily qualify for national park status, lie between these protected areas.

For hikers, backpackers, climbers, and backcountry skiers, the Kootenays offer the kind of freedom that is rapidly disappearing in parks and wilderness

areas throughout the world. With a few exceptions, such as Glacier National Park and Bugaboo Provincial Park, permits and fees are not required. One can just show up at a trailhead and enjoy the freedom of the hills. The Purcell and Selkirk Mountains are also home to many sub-alpine meadows with beautiful stands of Alpine, or Sub-Alpine Larch (Larix lyallii). If

the words ‘Larch Madness’ have you racing for your gear, then you’ll love the Kootenays. In the North Cascades, many of the best larch locations can be ridiculously overcrowded or increasingly out of reach due to strict permitting systems. But in the Kootenays, finding a beautiful spot and having it all to yourself is still possible. In contrast to the welcome empti-

ness, it must be noted that several areas are popular destinations for the helihiking and heli-skiing crowd. Canadian

Mountains Holidays (CMH) is one of several luxury lodges operating in the Selkirks and Purcells. It can be discon-

certing to grunt and sweat your way into a beautiful alpine basin only to hear the constant thumping of helicopters (or worse, unknowingly setting up a camp next to a landing area).

A couple of other things to consider when planning a trip to the Kootenays are road access and trail conditions. Access to trailheads can consist of a long drive on gravel roads, which are often very narrow and bone-jarringly rough. While most don’t require a 4x4 vehicle, they usually require high clearance. And for those accustomed to hiking along well-maintained trails in the Pacific Northwest, a hike in the Kootenays can be an eye-opener. Many trails receive

little or no maintenance and are merely rough routes over roots, rocks, and boulders, with nary a switchback.

In addition, if you’re traveling from western Washington, you can expect a long circuitous drive. Except for Glacier National Park’s Rogers Pass on the Trans-Canada Highway, these destinations generally require driving up and down long valleys and often require (free) ferry rides across lakes. It’s usually a good idea to plan a full day of driving to get to the trailhead, but the journey takes you through some awe-inspiring scenery, and along the way, you’ll get a chance to experience the local vibe.

The Kootenays are also home to several commercially-operated hot springs. These are sprinkled throughout the region and are just the thing after a rewarding trip into the mountains.

ANW

There are many spectacular trail destinations in the Kootenays, including Glacier National Park (not the one in Montana), Valhalla Provincial Park, Bugaboo Provincial Park, and Jumbo Pass. For more info, check out www. westkootenayhiking.ca. Excellent guidebooks include Where Locals Hike in the West Kootenay: Premier Trips Near Kaslo & Nelson by Kathy and Craig Copeland and Hikes Around Invermere and the Columbia Valley by Aaron Cameron and Matt Gunn.

by Abram Dickerson

On September 3, 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wilderness Act into law. Its purpose: “to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition” and “to ensure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.”

Photo by Jack Davis

At the heart of the Wilderness Act is a recognition of both the destructive appetite of humans and our capacity for wonder and reflection. When we stare at the night sky and simply open our eyes, it’s clear we are an anthropomorphic blip on an unfolding cosmic scroll. Yet, as a species with a seemingly inexhaustible drive to consume, we mine, manipulate, mar, and ultimately destroy the very earth that sustains us. Humans are fickle animals, capable of organizing the dust of this earth into the Sistine Chapel, the Taj Mahal, and the atomic bomb. In short, we are a paradox of power.

Yet, we are so busy with the logistics of living that we forget our place and our potential. The loss of nature as a sanctuary motivated the authors and activists to create the Wilderness Act. They were witnessing the destruction of the wild in a capitalist-fueled extraction of resources that was quickly destroying an ecologically sustainable and naturally beautiful landscape. They feared the development of the world and the loss of inspiration and connection to an inherently balanced and “unmarred” landscape. They feared the permanent loss of spaces for solitude and scenic inspiration that could remind us to be careful, to walk gently, and to channel our individual and collective action towards that which is beautiful, cooperative, and sustainable.

As we approach the 60th anniversary of the Wilderness Act and face yet another election cycle, it’s worth reminding ourselves that the systems we create for cooperation are fragile. We can rewrite our agreements and undo our citadels of law and order. That which we hold dear can be lost. Our market-driven, hyper-digitized, 24-hour click-buy-smear-kitten-face-insta-tick-scroll culture, if not unchecked, can distract and manipulate us into forgetting our place in the universe. What is that place?

Earth. Where beautiful, rare, and wild elements converge into intelligent and interconnected life. What is the “enduring resource of wilderness?” It is a reminder that life is sacred, wonderful, and worth working and loving to protect.

Last October, while in Bellingham for the launch of my book Teaching in the Rain I was asked several times whether I was hopeful about the future of the planet and the environment around us, and if so, what cause for hope buoyed me in these difficult times. I answered as best I could, citing the wisdom of my late esteemed colleague at Western Washington

Sometimes people say the world today is in a worse mess than ever, but as a student of history, I disagree.

University, David Clarke, who spoke of his “catastrophic crisis theory of social change.” He had experienced the London Blitz in 1940 and observed that people were not willing to change normal behaviors even in the face of the threat of Nazi Germany until the bombs started dropping. Then, recognizing the threat to their very survival, which we call an “existential crisis” today, they did so. This last-minute change of heart was not very comforting since it suggested that things had to get very bad before people would respond. Still, at least it offered a ray of hope that people might change behaviors that currently threaten our world in various ways.

Story by John C. Miles

I have been thinking about these questions ever since, and when Adventures Northwest invited me to write an essay on hope in these fraught times, I decided to accept the challenge. I won’t elaborate

Photo by John D’Onofrio

on all the reasons behind the questions because the questioners know the challenges facing society and the environment today, which is why they asked, perhaps seeking solace and inspiration. I came across a quotation recently that captures the essence of our situation. Writer, entrepreneur, and environmentalist Paul Hawken offered the insight that “Hope only makes sense when it doesn’t make sense to be hopeful.” Exactly! When things seem so difficult that one is tempted to feel despair and say, “Why bother, it seems so hopeless?” the need for hope is greatest.

So, what is hope anyhow? Is it optimism? Not exactly, because that involves believing that things will work out whatever we do. Optimism depends on faith, requiring nothing of us. Is it idealism, a belief that some ideal condition should and will be achieved? It is likely not idealism alone because nothing is achieved simply because one believes it ought to be achieved. So perhaps it is emotion, and to some degree, it is a feeling that things can get better. But there is more to it than that.

A. Thomas Cole, in his newly-published book Restoring the Pitchfork Ranch, writes that hope is “a discipline, a behavior, an intuition, a practice, a choice.” Cole’s definition struck me because when my environmental education students felt despair at all the bad news they encountered, all I could say was that they had a choice. They could choose to feel hopeless and give up, or they could forge ahead, realistically assessing what they could do to help the situation and forming a plan. And it would have to be a long-term plan because the positive effects of their choice would probably not be immediately apparent. All eventually chose to forge hopefully ahead because they realized that was what they had signed up for and the alternative was unacceptable. Sometimes people say the world today is in a worse mess than ever, but as a student of history, I disagree. The world is always a mess, a mix of good and evil, moral progress and regress. Think of what it must have been like for many during the twentieth century’s world wars,

or the bubonic plague, or for American Indians facing the juggernaut of colonialism and all that was being taken from them, including, very often, their lives. Those were indeed hard times, and not to make light of our current situation, but today, we have many tools to work toward hopeful outcomes if we choose to use them–and we have choices, unlike some of those earlier examples–so there is reason for hope.

I have studied the conservation movement in America, particularly the Pacific Northwest, for many years. Currently, I am working with my wife on a biography of Dave Foreman, who, back in the 1980s, became famous (or perhaps infamous) as a co-founder of Earth First!

Recently, I read a piece he wrote questioning his “Ecotopian” colleagues, who seemed to think the rightness of their cause would ultimately prevail. No, he wrote, that wouldn’t be enough. It would require action, engagement, political agitation, and even disruptive and forceful

action to protect wild places, biodiversity, and justice. Foreman had moments of despair, but he always came up with a plan to forge ahead, and he did much good.

Dave found hope in his reading of history–he could take the long view, in his case, even an evolutionary view. Martin Luther King, Jr. said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Dave was often impatient, but he agreed with this. He knew the history of conservation well, so he knew how long it had taken, for instance, to come up with the idea of protecting wilderness and to act on that idea. And how long it was taking to recognize that doing so was not just for the benefit of humans but for all living beings.

Originally, wilderness was given a measure of protection for the values it could offer humans, like inspiration, challenge, and relief from the stresses of modern life. He and others understood and enjoyed these values but went further to say that wild lands and wild creatures

had value in themselves and were intrinsically valuable, not just instrumentally valuable to humans. When Dave died after working toward this goal for forty years, he knew more work needed to be done, and the moral universe still needed bending, but he had done what he could and could take satisfaction in that.

None of us can save the world by ourselves. We should not think that way, for it would only lead to frustration. But in our microcosm, our corner of the world, we can make it better, and collectively, if enough of us are doing this, who knows what the outcome might be? Everything is uncertain. We cannot, of course, know the future or assure the outcomes of our efforts. As an educator for nearly fifty years, I hoped I was doing something good for each student that might result in cascades of good for many, but I could not know for sure if that was or would be happening. Nonetheless, I had hope, and a plan and made the effort, and after decades I can see some positive outcomes.

I’ll finish with a personal anecdote. I grew up in a rural New Hampshire town in the 1950s, and in front of my house flowed the Sugar River, a small tributary of the Connecticut River. I loved to be outdoors, and we played along that river for years, despite the water being so severely polluted we could see sewage dropping out of the riverbanks into the stream. A woolen mill upstream dyed the water bright colors: yellow one day, red the next. The only fish that survived in that cesspool were suckers which we could catch but shook off our hooks because we didn’t dare touch them. That was in the 1950s. When I returned to this same river in the late 1980s, I was astonished and delighted to find it was a blue-ribbon trout stream, flyfishing only, and very popular.

How did this happen? The Clean Water Act was passed by the U.S. Congress in 1972 and signed into law by none other than Richard Nixon. Pollution got so bad back then that rivers caught fire, Lake Erie was declared dead, and a “catastrophic crisis” seemed imminent. But with the help of this law and hard work by many locals who enjoyed the river, my little Sugar River was cleaned up. In 2016, wild Atlantic salmon returned for the first time to the Connecticut River, a sign that the entire watershed was healing. No salmon had made this journey since the Revolutionary War, and the struggle to restore this iconic fish migration continues. Other fish populations that had plummeted, including striped bass, sea-run brown trout, alewives, and endangered American eels, are recovering. This process of

restoring the Northeast’s longest river continues, but hopeful people are at work, and they are succeeding. In the face of what seemed long odds, they made a plan, are working tirelessly, and are hopeful the river will ultimately be restored— for their own benefit and that of many species.

Perhaps the most famous message about hope is from the Nineteenth-century American poet Emily Dickinson, who wrote,

Hope is the thing with feathersThat perches in the soulAnd sings the tune without the wordsAnd never stops - at all -

And sweetest- in the gale - is heardAnd sore must be the storm –That could abash the little Bird That kept so many warm –

I’ve heard it in the chillest land –And on the strangest Sea –Yet – never - in Extremity, It asked a crumb – of me.

Her message seems quite clear. We have a choice, and I choose to take the path of hope.

by Bruce Howatt

The rain falls for two days and nights, drifting through the trees, chilled by the breath of oncoming winter. Here at the Klipchuck Campground in the Methow Valley at the tail end of September, Jesse, Al, and I are waiting for the weather to turn so we can head up into the mountains. The rain falling here is likely falling as snow up where we’re going, a thought that fills us with anticipation. We’re on our annual quest to commune with the golden larches that illuminate the eastern flanks of the high North Cascades at this time of the year, and the combination of incandescent orange trees and freshly fallen snow is beguiling indeed.

parking lot. Today, the lot is crammed with cars and bustling with eager hikers preparing to head out to various destinations on the Golden Lakes Loop, a

Finally, on the morning of the third day, the clouds part ways and we eagerly break camp. After the obligatory stop at Cinnamon Twisp (a beloved bakery/breakfast spot in downtown Twisp), we head up into the mountains, following the winding road beside Gold Creek to the Crater Creek Trailhead.

The last time I was here (way back in 2012), mine was the only car in the

23-mile circuit that in recent years has become famous as a larch pilgrimage par excellence. The full loop, which I completed on a previous excursion, involves surmounting both Horsehead Pass and the legendary Angel Staircase.

Upper Eagle Lake, our destination for the evening, is the first marquee attraction on the loop.

We load our backpacks and head up through the dense forest, quickly leaving the hubbub of the trailhead behind us. After crossing a bridge on Crater Creek and reaching the junction where the Crater Creek Trail branches off to the north, we continue climbing on the Eagle Lakes Trail, gradually reaching more open terrain, small stands of aspen, and eventually the first scattered larches.

The Larch is unique among the trees of the North Cascades, a graceful conifer whose needles turn a resplendent golden color in autumn. The range is home to two distinct species. The alpine larch (Larix lyallii) grows exclusively at high elevations, usually above 5,000 feet, while the Western Larch (Larix occidentalis) occupies relatively lower elevations between 2,000 feet and 5,500 feet.

Generally speaking, their vibrant color peaks in late September and early October. When in their full glory, they glow with an incandescent fire that illuminates the forest. For my money, they offer an autumnal spectacle that is unmatched, and the dramatic settings in which they are found only add to the glory.

As we climb through the thinning forest, the surrounding mountains

come into view above the Marten Creek Valley. Before long, about five miles from the trailhead, we see Lower Eagle Lake, far below in the darkening forest.

We turn right on the side trail towards Upper Eagle Lake, winding our way among the golden trees over a rise before a gradual descent to the shore of the lake, its surface an unimaginably beautiful mirror reflecting the larch forest, the snow-dappled ramparts of Sawtooth Ridge, and the deep blue of the sky.

We pitch our tents on a more-or-less flat spot beside the lake shore and put on every layer of clothing we have as the temperature plummets in the halflight of twilight before enjoying dinner beside a small crackling fire, then dive into our sleeping bags as a cold wind

blows down from the dark peaks. The morning dawns clear, windy, and cold. There is ice in my water bottle. The rising sun climbs above the

puffy white clouds glide across the lustrous blue sky.

ridge to the east, spreading a syrupy golden light across the lake, illuminating the larches in an almost iridescent color. We sit quietly with our morning coffee, bathe in the light, and watch

After an hour of basking in the warm sun, Jesse heads up toward Horsehead Pass while Al and I relax beside the lake, entranced by the cloud shadows that dance across the surface. The cliffs across the lake are adorned with rubble and scree, filigreed with freshly fallen snow in chiaroscuro patterns of white, grey, and black. Scattered stands of larches, like elements in a Maxfield Parrish painting shine like torches. When the wind subsides, the surface of the lake becomes still, reflecting the splendor.

I wander off alone among the larches on a soft carpet of golden needles spread among the shattered rocks and fallen limbs, relishing the intrica-

cies of the golden forest. High above, whisps of cloud caress the barren summit of Mt. Bigalow.

In mid-afternoon, the sun drops and the last golden rays stream between the larch-fringed spires that form Sawtooth Ridge. Finally, with a final burst of light, it disappears below the ridge, and the temperature drops 20 degrees in a heartbeat. The silence is broken only by the vespers of birds and the gentle lapping of the lake.

As darkness settles over the lake, the wind gusts across the water like a coming attraction for winter—waiting impatiently in the wings—on this final day of September. The

Like so many beautiful destinations in the North Cascades, Upper Eagle Lake gets a lot of traffic these days. Larch Madness has become a sort of religion in the Pacific Northwest. As access to many of the famous larch destinations—such as the Enchantment Lakes— becomes ever more restricted as a result of tight permitting, more and more acolytes find their way here instead.

Currently, there are virtually no restrictions in place. No backcountry permit is required to visit (or camp), campfires are allowed, and the Eagle Lakes Trail (although not the Upper Eagle Lakes Trail) is open to mountain bikes (and motorcycles!).

How long this situation will remain so unfettered is anyone’s guess. Therefore, visitors must practice strict ‘Leave No Trace’ ethics. But beyond packing your trash out, hikers must conduct themselves with a high level of consideration for the fragile nature of the setting and the wilderness experience of fellow hikers. If camping, choose an established campsite, and if having a campfire, keep it small and burn only down dead wood. There’s a mountain privy located near where the trail reaches the lake. Use it. Do not wash anything in the lake—not your dishes, not your body. Respect your fellow visitors by keeping quiet. Leave your Bluetooth speaker at home.

Visiting such a pristine and beautiful place is an increasingly rare privilege that should be respected, or, like so many places, the very qualities that draw pilgrims here will be lost.

last lingering clouds are blown away, leaving a crystalline sky and twinkling stars. The wind whips up boisterous waves that splash restlessly in the darkness as a full moon rises, bathing the freshly fallen snow across the lake in pearly light.

We make dinner and lean back in our Therm-A-Rest chairs, sharing stories beneath the star-spangled sky before slipping into the warm cocoon of our sleeping bags.

In the morning, a pastel sunrise ushers in October, and I sit on a rock, swaddled in layers of polypro, fleece, and down, staving off the morning chill, which is finally vanquished by the welcome warmth of the sun.

What a joy it is to sit here, sipping my coffee, savoring the silence in this wild place, watching the light change and the clouds pass. Moments like this nourish my soul and remind me of much that is important to remember but so easily forgotten in my busy life. I savor the warm sunlight and the stillness, and rejoice in my good fortune—another golden moment to treasure on my journey around the sun.

From the Crater Creek Trailhead, hike the Crater Creek Trail 0.7 miles, staying straight at a junction with the Eagle Lakes Trail #431. Pass a junction with the Martin Creek Trail about two miles from the trailhead. Continuing upward, cross Eagle Creek, and turn right on the Upper Eagle Lake Trail at 5.7 miles. From here, it’s a half-mile to the lake.

Drive the North Cascades Highway (SR20) through Twisp to a right turn on the easy-to-miss North Fork Gold Creek Road (4340). At 6.6 miles, hang a left on Road 300 and follow it for six miles to the Eagle Lake/Crater Creek (431) Trailhead. A Northwest Forest Pass is required.

By Robert Wrigley

One hundred fourteen miles to the nearest streetlight, twenty-six to a paved road, eleven from the truck, and almost two hundred forty thousand to the new moon,

which cannot be seen at all from earth tonight. So many stars, even the most familiar constellations are harder to discern, but up there in that thicket of twinkling is Draco,

the dragon, second-to-last of the famous labors of next-door Hercules, although tonight it appears both hero and dragon are ostentatiously dressed and battling to the death in flounced, sequined,

and glintingly bejeweled ball gowns, in rhinestoned boas and hats of gaudy astronomic proportion, trillions of miles from stellar peacock feather tip to flirty brim.

Instead of his usual oaken club, Hercules swings a precious astral parasol, and Draco sprawls like a cat on a black velvet diamond dusted pillow. From here, you can see they’re just not into it

anymore, if they ever really were. Years of deranged poets just making it up as they went along, neither Hercules nor Draco wanting to disturb the lovely Hesperides, nymphs of evening and sunset. And yet still, their golden apples— such flashy baubles with which to accessorize; also the fact that Hercules must redeem himself, having slaughtered his wife and children.

Why does it mean, so much myth dwelling in darkness?

Why can’t gods and dragons dress up and find a release that doesn’t lead to carnage? O poor mortal humans of earth, poisoning themselves with their own illumination until all the sky looks like over-used bedding. But from out here, where almost no one human lives, we can see another way— star derived infinite dust, universal proximity.

As the night goes on, other more distant stars appear and allow us to see that Hercules and Draco battle not at all but embrace, as if they beg forgiveness, and even, eventually, disappear together in a heavenly cloud of peace and light years, almost as though they’re only stars, after all, stars that live and die but go on for what might as well be forever, like all the other gods that ever were.

Celebrating 55 Years Supporting Pacific Northwest Clay Artists!

By Brett Baunton

Ifindthere is nothing more invigorating than a mountain adventure in the fall. Temperatures are comfortable and the bugs are gone. Salmon are coming up river to spawn and birds fly overhead on their migration south. Glorious alpine meadows feature red, orange, and yellow foliage and ripe blueberries provide trailside refreshment. Nothing tops the iconic larches glowing like golden torches at tree line on the eastern crest. It’s prime time in the North Cascades, and for me, absolutely unforgettable.

See more of Brett Baunton’s photography at www.brettbaunton.com.

Visit AdventuresNW.com to view an extended gallery of Brett’s mountain photography.

Story by Amy Eberling

Theair buzzes with excitement

as each smiling guest, aged five to 99, boards the vessel, united by a shared mission to encounter one of the Pacific Northwest’s most captivating maritime treasures: a football-sized seabird that spends most of its life in the vast Pacific Ocean: the Tufted Puffin.

As we head south from the marina, a curious nine-year-old girl named Isla asks, “Why are these birds here?”

“There isn’t a safe place to build nests in the open ocean,” I explain, “When winter turns to spring, their fancy feathers emerge, and they journey hundreds of miles to isolated rocky coastal areas or remote islands. Scientists believe they return to nest at the same spot where they were born. Imagine making that long journey ‘home’ without the help of Google Maps! Isn’t that incredible?”

the position of the sun, moon, and stars, sensing the earth’s magnetic field, and detecting the unique scent of their nesting area,” I reply.

“Similar to salmon returning to a river!” exclaims Isla.

“Yes, exactly!”

Once they reach their breeding

hand, the protection and incubation of this egg is paramount. Over the course of six weeks, both parents take turns protecting and incubating this precious egg. Once the chick, affectionately known as a ‘puffling,’ emerges from the egg, it relies on its parents for nourishment until it’s prepared to take its first flight, usually between 38 and 44 days after hatching. At this point, the young puffling must venture out on its own to learn how to fly and forage for food.

Anticipation among the guests grows as we approach a small, isolated island near the eastern edge of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Everyone wants to be the first to spot an elusive Tufted Puffin.

“Wow,” says Isla, “my parents need their phones for directions! How do the birds even find their way?”

“Scientists believe they use a combination of visual landmarks such as

ground, Tufted Puffins reunite with their mates through a series of bill-clatters and courtship displays. These seabirds, believed to be monogamous, form longlasting pair bonds that remain from one breeding season to the next. Seabirds typically live longer than other birds and invest a significant amount of time and energy into nurturing the single egg they lay each year. With only one chance at

Off the bow, a cluster of floating feathered silhouettes catches our attention. Using binoculars, we realize it is a group of their tufted relatives, Rhinoceros Auklets, nestled amongst floating bull kelp bulbs. It’s no coincidence that many seabirds are found near seaweed forests such as this, as these underwater havens play an essential role in nurturing the forage fish that serve as their primary

food source. The one at Smith Island is the largest bull kelp bed in Washington State.

But wait, with the swift turn of a head, a long-awaited flash of white and vibrant orange bill catches someone’s attention.

“There! Look!” Isla shouts triumphantly, “WOW! Their tufts are beautiful!”

Sure enough, a pair of brilliant Tufted Puffins gracefully paddle through the water off the bow. Their mesmerizing golden tufts flutter elegantly in the wind, reminiscent of models posing on a runway. These tufts are not a permanent feature but part of their seasonal transformation, known as breeding plumage. As summer draws to a close, their tufts will fall off, and their vibrant white face and orange bill will darken. It is also interesting to note that puffins exhibit monomorphic

characteristics, meaning based on plumage alone, the difference between males and females is indiscernible.

As quickly as they appear, the puffins disappear beneath the surface to hunt, leaving us time to discuss their natural history.

“Auks are a family of seabirds, also known as Alcidae (al-KID-ay), that comprise a diverse group of seabirds including puffins, guillemots, murres, and auklets. They originated in the North Pacific around 8-10 million years ago. Today, they inhabit a vast range stretching from the Bering Sea and Alaska in the west to the coasts of Europe, Iceland, and northern North America in the east.

“Tufted Puffins belong to the Auk family,” I share with the passengers,

“It

They are highly adapted for life at sea, thanks to dense, waterproof, insulating plumage, short wings for diving and underwater propulsion, and specialized bills for catching fish. In essence, these birds are masters of the underwater realm, capable of ‘flying’ effortlessly through the deep with ease as they pursue their prey. Diving depths vary by species, with some diving up to 200 meters deep!”

Ann F. & Dave W • 2023 – Alaska Cruise

“What do they eat?” Isla asks. “Tufted Puffins will consume small fish and crustaceans underwater before surfacing. Occasionally, we get lucky and see them surface with 10- 20 fish across their bills, held in place by specialized small tooth-like structures on the roof of their mouth called denticles. When this happens, we can assume they are returning their catch to their newly hatched chick on that island right there! It is important to photograph puffins carrying fish because we send the pictures to local scientists who are studying their diet. Thus far, we have found bill loads around the Salish Sea full of a

There are numerous ways to improve the overall water quality of the Salish Sea, benefiting not just the puffins but all marine life. These actions include:

• Scooping the Poop: Always pick up after your pets to reduce harmful bacteria entering waterways.

• Adopting a Storm Drain: Regularly clean a storm drain near your home to prevent debris and pollutants from reaching the sea.

• Holding Sea Safe Celebrations: Minimize plastic decorations and avoid purchasing and releasing balloons, as they often end up in the ocean.

• Leaving No Trace: When exploring the outdoors, leave it as you found it.

• Sharing the Puffin Story: Discuss these beautiful seabirds to raise awareness and inspire others to consider their conservation.

small bait fish called sand lance.”

Smith Island stands sentinel in the background, serving as one of these precious seabirds’ last two remaining breeding islands in the Salish Sea.

“Smith Island is a very special place,” I explain to the passengers. “It is part of the Smith and Minor Islands Aquatic Reserve that was established

in 2010. It covers over 36,000 acres of state-owned aquatic land and due to

its protected status, we must keep a respectful distance of at least 300 yards. However, with your binoculars, you can still observe the nesting burrows. Take a look at the top of the island, just below the grass line—those are nesting holes created using a combination of bills, feet, and wings. They can be two to six feet deep! Other birds like Rhinoceros Auklets and Pigeon Guillemots also use burrows for nesting.”

The Tufted Puffin population along Washington’s coastline and throughout the San Juan Islands has experienced a tragic decline over the past century. According to the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, in 1909, there were an estimated 25,000 Tufted Puffins across 44 nesting sites on the coast of Washington and in the interior Salish Sea. By 2009, the population had plummeted to less

than 3,000, with only 19 nesting sites remaining and only two in the Salish Sea. This dramatic decline led to the Tufted Puffin being listed as an endangered species in Washington in 2015.

If the alarming 8.9% annual decline continues, the state’s population could become functionally extirpated (locally extinct) within the next 40 years.

Although we cannot pinpoint the exact number of Tufted Puffins return-

ing to Smith Island, scientists estimate that fewer than 60 individuals return yearly. Because they spend much of the day hunting in different places around this island, we will be lucky to see between five and ten individuals during our visit.

Tufted Puffins range across the North Pacific, from as far east as Japan to northern California. They are listed as ‘Endangered’ in Japan, ‘Sensitive’ in Oregon, and ‘Species of Special Concern’ in California. While the population appears stable in Alaska, a troubling mass die-off event on St. Paul Island in 2016 raises significant concern for the species’ future. Over 350 severely emaciated carcasses washed ashore, underscoring the urgency for further research and conservation efforts to safeguard these remarkable birds.

In Washington, scientists are in-

vestigating several factors that may be contributing to their local decline. Some potential reasons include loss of breeding colonies from coastal development, which leads to reduced nesting success, bycatch in commercial fishing nets in the Pacific Ocean, changes in oceanic conditions, or overfishing, which affects their food supply. Changes in prey abundance or distribution can cascade effects on populations, affecting reproductive success and overall fitness. Their decline is a powerful reminder of our interconnectedness with the natural world and the significant impact our actions can have on the diverse species that inhabit our planet.

Efforts to conserve and recover the Washington population are ongoing, yet the most effective methods to support their recovery remain unclear. Local researchers are working to protect and restore nesting habitats by installing artificial nest boxes and using Tufted Puffin decoys to attract nesting pairs. They are also monitoring population trends, breeding success, and foraging behavior.

The Salish Sea School, a nonprofit organization based in Anacortes, is on a mission to awaken curiosity and deepen connections with the sea through outdoor education programs, citizen science initiatives, and ecotours. These unforgettable experiences allow students and community members alike to develop a stronger bond with the sea and its inhabitants, ultimately inspiring a commitment to preserving the fragile beauty of the Salish Sea. Our engaging ecotours have provided over 2,000 students, families, and adults a unique opportunity to actively contribute to Tufted Puffin conservation efforts. Additionally, our ecotours provide valuable data for scientists to contribute to ongoing research and monitoring efforts. Through these immersive educational experiences, The Salish Sea School continues to instill a deep love and sense of responsibility for the marine environment among all participants, inspiring a lifelong commitment to its preservation. We warmly invite you to join us on an unforgettable conservation ecotour to witness firsthand the majesty of Tufted Puffins and become an active participant in their protection. Together, we can secure a brighter future for these remarkable seabirds and the precious ecosystems they call home.

Learn more at: thesalishseaschool.org/bird-tours

Altogether, these efforts help to better understand the ecology and inform conservation strategies.

After seeing a few more Tufted Puffin pairs, we begin to make our way back to Skyline Marina in Anacortes beneath a sky radiant with soft pink hues as the sun sets, inspired both by the beauty

art of nature

Gretchen Leggitt’s massive murals are evidence of her rooted passion for the natural world. Whether splitboarding, climbing, kayaking, or pedaling, landscapes that have caught her eye amidst a lifetime of adventures inspire Gretchen’s playful subjects. Leggitt’s compositions depict her unique perspectives of nature, encapsulating topography’s nuanced geometry and the energetic movement of the elements.

Her colorful murals can be found across the country, including the largest in Washington State, spanning over 22,000 square feet. She resides, recreates, and creates in Bellingham, WA, ancestral lands of the Coast Salish People.

Learn more at gretchenleggitt.com

of the Salish Sea and our encounter with the Puffins.

Clearly, these charismatic birds are influential ambassadors for their own protection. We must all remember that every small action counts and that together, we can protect and celebrate the rich biodiversity in our coastal ecosystems.

Story and Photos by Robert Kandiko

North Cascades National Park contains some of the most spectacular mountain scenery in the United States, but due to its rugged topography, accessing the alpine zone is physically demanding. Most trails begin at low elevations in old-growth forests, and hikers must work to get to the tree line for truly jaw-dropping vistas. Beyond the trails lies the most rugged terrain in the lower 48 states. Extending your adventure beyond the maintained trail system is not for the meek.

The “Elephant in the Park”

(Elephant Butte) takes this thought to the extreme. The summit is definitely not one of the classic peaks, such as Forbidden, Challenger, Torment, or Terror, sought out by climbers. Elephant Butte requires no technical climbing skills because it is more of a lump on a ridge than a dramatic rock spire. At 7,340 feet, Elephant Butte is not even one of the highest 200 peaks in the range. So why my fascination with it? Location, location, location! Elephant Butte is positioned close to the center of the most spectacular sector of the park, the Pickets.

This isolated subrange of the park contains the most jagged collection of

rock spires in the most remote location. The Pickets hold a mystical allure to mountaineers due to their beauty, history, and remoteness. Like a moth drawn to a flame, climbers approach this area with a humble understanding of the risk involved in reaching one of the summits. When hikers see the Pickets from a distance, they appear as serrated teeth against the horizon.

Elephant Butte provides the rare opportunity to experience the wildness of the Pickets without the technical gear or skills of an alpinist and the usual heinous approach through steep slopes covered with slide alder and Devil’s Club infested

with black flies, mosquitoes, and ground hornets. So why the “Elephant in the Park” metaphor? Reaching the summit of this 7,340-foot peak requires nearly 10,000 feet of elevation gain and loss over roughly 20 miles of travel!

On Labor Day weekend, 1998, Karen Neubauer and I started up the Sourdough Mountain trail at Diablo, a small town 900 feet above sea level. Tired of hoisting packs full of ropes, helmets, crampons, and ice axes, we selected Elephant Butte as our objective. Countless steep switchbacks led up through the canopy of conifers and understory vine maples. 4,000 feet up we left the trail and headed up to the crest of Stetattle Ridge, where we gazed out over deeply shadowed valleys to a sea of peaks stretching in all directions. At 6,500 feet, we set up the tent near a late-season tarn beneath a rising full moon.

Up before that moon set over Mt. Fury, we continued out the ridge with its many ups and downs until we reached its high point at 6,800 feet. To the west, Elephant Butte seemed tantaliz-

ingly close until we saw the BIG drop between our perch and the peak. We descended 1,500 feet only to regain that—plus another 1000 feet—to finally reach the rounded summit where we were rewarded by 360-degree views into the heart of the range. To the east, we could see the long ridge we had traveled leading back toward Ross Lake. To the south was the Colonial/Snowfield group leading through a maze of peaks towards Cascade Pass. To the north, the less visited Redoubt/Spickard group rose into the sky near the Canadian border, while to the west, oh so close, were the jagged Pickets highlighted by the dramatic glacier-clad northern walls of the Southern Pickets. The view was one of the best we had enjoyed on our many excursions in the region.

We gobbled a quick lunch before turning back, which meant that we had to drop 2500 feet before gaining 1500 feet to Stetattle Ridge. After 10 hours of arduous travel, we arrived at camp just as the full moon rose. The following day, we descended almost 6,000 feet

back to the car. Just another “normal” outing in the Cascades! Nearly 10,000 feet up and down, for a 7400-foot summit: “The Elephant in the Park”.

As a child, I instinctively checked to make sure the bedroom closet doors were shut before turning out the lights, thereby guaranteeing that the monster that may be lurking inside would not enter the bedroom while I slept. What that monster looked like was uncertain, but it wasn’t pretty. Six decades later, I would glimpse that monster.

For years, I ruminated about that ’98 Elephant Butte climb, haunted by the vivid memories of that spectacular panorama of wild peaks. A return trip beckoned, and like an addict, I had to have another fix. Karen knew better. I coerced my friend Dave to join me for a July trip in 2022, 24 years after first reaching Elephant Butte’s summit. The approach trail towards Sourdough Mountain seemed steeper than I had remembered.

Dave simply powered ahead as he always does. By the time we reached the campsite, I was completely exhausted. To the west, Elephant Butte seemed very far away.

The next day started with weary legs and the undulating Stetattle Ridge seemed unending. We reached the high point before the BIG drop. This time it seemed like a chasm and not a drop. Fatigue crushed my will to go forward. Kindly, Dave accepted the decision to turn back, and we savored the view, which is still superb but not the penultimate summit vista I had promised him. The ‘monster’ in my closet—aging—had finally appeared. Somehow, I knew this

trip would be a delineation in my life that could not be denied. In youth, we ignore the aging process and see it in others as something separate from ourselves. Elephant Butte nudged me past that blind spot. That monster had exited the closet, never again to be corralled back in.

It had been a wetter-than-normal winter in the Pacific Northwest, resulting in a heavy snowpack. But then, an unusually late spring heat spell caused much of the snowpack to melt. A delightfully warm, dry summer settled over Western Washington.

On July 29, 2023, a thunderstorm

blew into the North Cascades, bringing a fury of lightning strikes to the dry forest above Diablo Lake. This unique geographical area, east of Newhalem, has a slightly drier climate zone due to a rain shadow effect caused by the western peaks of the Cascades. The Sourdough Mountain Fire had been ignited.

On August 4, the combination of heat, high winds, and tinder-dry forest resulted in a rapid acceleration of the fire, giving birth to a massive plume of smoke rising thousands of feet into the sky. This cloud, resembling a violent cumulonimbus thunderhead, could be seen throughout the Puget Sound Region. Over 400 firefighters struggled to con-

tain the flames, fighting desperately to keep the fire from crossing Highway 20, burning the town of Diablo, incinerating the North Cascades Institute, and reaching the powerlines and facilities of Puget Sound Energy. The North Cascades Highway was closed, as were all trails and campgrounds in the Ross Lake Recreation Area and the immediate North Cascades National Park area. The North Cascades Institute canceled its summer and fall educational programs, some of which ironically were to have been focused on the local effects of climate change.

In recent years media coverage of the effects of climate change has centered on the devastating California fires, the longlasting drought on the Colorado Plateau, and the flooding in the Northeastern

large forest fires on the eastern slopes of the Cascades, as well as dry spells affecting agriculture and fisheries.

United States. The influence of the warm, moist Pacific Ocean has spared the Pacific Northwest from some of the significant impacts of climate change. Still, over the last decade, the region has suffered from

The hike Dave and I made up the Sourdough Mountain Trail was made memorable by the lush forest, which provided cooling shade in an otherwise dry and hot south-facing aspect. The transition from this canopy through the more open subalpine meadows was a portal to the nirvana of mountain scenery. It is unknown how much immediate impact the Sourdough Mountain fire had on the trail leading up to Stetattle Ridge and Elephant Butte. Several other

recent fires in the Chilliwack River/Bear Creek drainages and at Downey Creek in the Glacier Peak Wilderness have necessitated closing trails for years to allow crews to cut down trees and stabilize slopes for safe passage. Those fires were in very remote areas normally only visited by avid backpackers.

The “Elephant in the Room” metaphor refers to something too taboo to discuss openly. In many quarters, climate change is such a topic. One cannot ignore the scars of the Sourdough Mountain fire, along with the Newhalem fires of 2015 and the 2021 Cedar Creek fire near Mazama, above Highway 20. Though fires are part of the forest ecosystem, the recent increase in both frequency and severity of fire events in the Cascades seems to represent a new normal.

A recent article in the Seattle Times quoted a forest service ranger stating that over 100,000 hikers visited the iconic Enchantment Lakes last year, mostly on

extended day hikes, as the coveted overnight permits are obtained only via a lottery, which is almost impossible to win. Over a single afternoon, as many as 1000

hikers have been recorded at Colchuck Lake. On a typical summer weekend, the Artist Point parking lot near Mt. Baker is full by mid-morning, with cars lining the hairpin corners back down to the Lake Ann trailhead. An autumn weekend may have more than 400 cars lining the North Cascades Highway by the Maple Pass and Blue Lake trailheads. During the Perseid meteor showers last summer, crowds overwhelmed the Sunrise parking lot at Mt. Rainier National Park. Some trampled the fragile meadows in an attempt to find enough space to view the night sky. My most recent overnight trip to the high campsite on Sahale Arm in North Cascades National Park required a very lengthy wait at the Marblemount Ranger station to secure a permit. The Park now issues, through Recreation.gov, advance backcountry camping permits in early

spring for the majority of campsites, leaving a small percentage available on a firstcome basis, so I felt incredibly lucky to score a permit to visit this highly desired camp, which has only six permitted sites.

Our small group ascended 4000+ feet in mist and fog to the wildly exposed campsite. The following morning, we took advantage of clearing skies to summit Sahale Peak, expecting to savor the remarkable views from our remote campsite when we descended at day’s end. To our dismay, we discovered our tenting zone completely overrun by dozens of day hikers who had raced up the trail starting in the dark. The noise from music and cell phone conversations filled the air, ruining any hope that our group could enjoy a communion with nature in one of North America’s most spectacular backcountry locations. Reluctantly, we admitted defeat, packed our gear, and descended to the parking lot, passing more than a hundred hikers heading up.

It has truly become a “tragedy at the

On the shores of Lake Crescent

commons” where an increasingly large population’s use of a limited resource dilutes the value of that resource for everyone. The resources allocated to parks, wilderness areas, and national/state forests have not increased. At the same time, the population in the surrounding areas continues to grow, at times exponentially. The desire to experience nature has also exploded, partly due to the enforced isolation wrought by the pandemic. Resource managers, both at the national and state

levels, are challenged with the unenviable task of providing access while, at the same time, protecting the resource. The “Elephant” of overcrowding and population growth may be the most significant dilemma of all.

Wilderness is a place on the map. Wildness is a quality of being uncontrolled. These two words, so similar in spelling, may be increasingly difficult to find together.

COMPASS | Real Estate Agent (360) 319-0696

Brandon@BrandonNelson.com

A hidden gem kind of place... where the air smells like pine needles and adventure. Majestic trails wind through lush forests, their leaves ablaze with the fiery hues of autumn and don’t be surprised if you stumble upon a hidden waterfall or two. Pack your bags, grab your sense of wonder, and get ready to undiscover Idaho.

by Paul Tolme

You’ve probably been car camping, but have you ever tried bike camping— commonly called bikepacking? It’s a great way to enjoy a short autumn getaway while pedaling right from home to the nearest campground—no automobile required.

The abundance of ferries in the Northwest and in Seattle, where I live, makes it easy to roll onto a ferry or water taxi with our bikes and gear and disembark on Bainbridge or Vashon islands, the Kitsap Peninsula, even a foreign shore when bringing our bikes aboard the Victoria Clipper.

Electric bikes have made bike overnighters even easier. My wife and I load up our Tern cargo bike without concern about overpacking or traveling light. E-bikes enable a car-lite lifestyle where every outing is a healthy adventure.

Not into sleeping on the ground? Try bike glamping. Katie and I recently drove to the Anacortes ferry terminal, parked in the long-term lot, biked onto the ferry wearing a light backpack of clothes and toiletries, and spent two amazingly comfortable nights close to nature on Lopez Island.

Our destination was Lopez Farm Cottages, an idyllic organic farm with sheep and chickens, walled tents on platforms, a queen-sized bed inside, and hot showers and clean bathrooms nearby. Lopez is the least populated and most bikeable of the San Juan Islands, with lots of camping options and relatively light traffic.

September and early October are the perfect times to visit Lopez due to smaller crowds and milder temperatures. As summers have heated up and gotten smokier, fall has become my favorite biking season.

Two of my favorite fall bike events are the three-day Lake Chelan Tour on September 27-29 and the Kitsap Color Classic on October 6. Both are organized by Cascade Bicycle Club, the statewide nonprofit whose 54 years of advocacy have made Washington one of the most bike-friendly states in the nation.

This year, bikers will celebrate the 30th annual Kitsap Color Classic with routes of 25, 33, or 54 miles, and food stops at Norwegian Point, historic Port Gamble, and the Scandinavian town of Poulsbo, plus a finish line party in Kingston. Hope to see you there.

Bikes represent freedom because the outdoor adventure begins immediately upon pedaling away from home. That sense of freedom and joy I get while bicycling is tempered this year by uncertainty about our democracy.

Instead of voting by mail, I plan to bike my ballot to a drop box. It will be a symbolic gesture in light of the fact that bicycles and the cleaner world they represent are on the ballot.

Bicycles are on the ballot in Seattle, and I will vote yes to raise my property taxes to fund more bike lanes and safer streets. They are on the state ballot, and I will vote no on Initiative 2117, which would kill Washington’s Climate Commitment Act.

Bicycles democratize transportation. Join me this November in biking to the ballot box. It could be the most important bike ride of our lifetimes.

Story by Cathy Grinstead

We hear the words “paddles ready… paddles set…and hit” from our steersperson, and the outrigger canoe starts its glide through the water, gaining speed with our paddle strokes. We round the breakwater and out into the open water of Fairhaven Harbor. All of us relish this feeling of getting on the water and moving together. It feels like freedom.

On quiet mornings, the bay belongs to us and the gulls. The fishing boats have left long before. The water can be glassy, or we can paddle through wind, waves, and fog. Occasionally, seals pop their heads out of the water and watch us pass. There was one exhilarating windy paddle where people on the shore later told us that an orca followed us as we paddled south out from Waypoint Park back to the boating center—none of us saw it since we were concentrating on our paddle strokes. Evening paddles are magical in a different

way. The longer days of our northern summers mean we have time for a paddle after our workday has ended and can enjoy the changing colors of the clouds and the water as the sun sets. Paddling towards Clark’s Point, watching the setting sun light up the orange madronas as we pass along the shore is the definition of serenity.

As we stroke through the water, it’s hard not to admire the views of the islands, the Olympics, the Canadian peaks, Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters, and the Bellingham waterfront. We live in an amazingly beautiful place.

However, the magic of paddling in a sixperson outrigger canoe is the experience of “ohana,” or family, a notion of community and support. We share the experiences of our paddle, on and off the bay. We also share the connection of our canoes with the ancient Polynesians and Hawaiians and are privileged to participate in this ancient tradition in our own sacred waters of the Salish Sea. ANW

Story and Photo by Ken Wilcox

Whenwe think of the “North Cascades,” I’m sure we all have a certain image that pops into our heads. Perhaps it’s the awesome view of Mount Baker or Shuksan from Artist Point or one of the stunning vistas from the North Cascades Highway, like the Diablo Lake Overlook or Washington Pass. For me, it’s Glacier Peak and the Mountain Loop Highway between Granite Falls and Darrington.

In fact, I blame my hopeless addiction to mountains on the Mountain Loop. When I took up mountaineering, I approached many of the first peaks I climbed from said highway: White Chuck, Del Campo, Vesper, Sloan, Pugh, and Glacier Peak (for me, the symbolic center of the range), as well as Whitehorse and Pilchuck, summits that anchor the endpoints of this remarkable corridor.

Creek, historic Monte Cristo, the myriad lakes east of Granite Falls, and Barlow Point, where I can pretend I’m still at 5,000 feet because the view is so good. However, access can get a little tricky by November, when the highway typically closes, depending on conditions. It’s gated for the winter at Deer Creek and Bedal Campground, usually until May.

In the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps built roads, trails, and campgrounds along the future Mountain Loop, and the highway was officially dedicated in 1942.

Along its 54-mile length are numerous trailheads, campgrounds, picnic areas, river access points, and historic sites. Most of the two-lane highway is paved and well maintained, except for a 15-mile midsection of gravel, which can get a little rough in places, depending on when it was last graded.

I often return to the Loop to bask in this vertical world’s rugged beauty. And now, as we drift into autumn and I’ve more or less satisfied my peak-bagging urge, my interest shifts to favored trails like Squire Creek Pass and Cutthroat Lakes. Who can resist the higher ground with its alpine reds and yellows tinged with frost, draped below ridges and spires dusted with October snow?

As the season advances, as the snowline falls, and my fingers freeze, I look more to mid-elevation hikes, like Perry

Officially completed in the early 1940s, history traces the Mountain Loop Highway’s roots to the discovery of gold and silver at Monte Cristo in 1889. Miners extended a wilderness wagon road up the Sauk River valley from Darrington to haul the ore to the smelter in Everett. But engineers soon realized a railway from Granite Falls over Barlow Pass would be far more efficient. The first train arrived in the bustling mountain town in 1893. However, the boom was over within a few years, and floods decimated the railroad tracks.

In the 1920s, railroad logging expanded rapidly up the Sauk, and vacationers and adventurers began to discover these new avenues into the mountains.

In early fall, consider a stiff hike up Mount Pilchuck on an excellent trail to the historic fire lookout (6.2 miles RT, 2,200-feet elevation gain, access near milepost 12.1) or a longer scenic trudge up Mount Dickerman, including fall color and a good look at Glacier Peak (8.4 miles RT, 3,900-feet elevation gain, access near milepost 27.4). These are popular hikes, and for good reason. For more elbow room, go on a weekday if possible.

Squire Creek Pass via the Eightmile Trail is steep and rugged but a fine choice for extensive views before the snowy months set in (5.6 miles RT, 2,300-feet elevation gain, access from the Clear Creek Road near milepost 50.8).

For a more moderate and familyfriendly hike—sometimes on boardwalk planking—to Ashland Lakes (5.4 miles RT, 800-feet elevation gain). Walk as little or as much as you like while visiting these peaceful lakes surrounded by old-

growth forests. The road to the trailhead is well-signed from the Loop at milepost 15.8.

Barlow Point rarely sees a crowd. Despite some steepish switchbacks, it’s just over a mile long with a 900-foot gain to the big view from an old fire lookout site. Find the trailhead at Barlow Pass (milepost 30.6).

Finally, you don’t want to miss the majestic view from the Big Four Picnic Area and Ice Caves trailhead at milepost 25.5. A barrier-free loop follows part of the historic Monte Cristo Railway grade, then crosses wetlands on a boardwalk to a river bridge. From there, the kid-friendly hike climbs another mile, gaining just 200 feet to full-on bliss.

Story by John D’Onofrio

When I heard about Jasper burning, I wept.

This little town, long a venerable outpost in the Canadian Rockies, is (was) one of my favorite places in the world. Located way up at the northern terminus of the worldrenowned Icefields Parkway, Jasper was a special place, a throwback to the days of oldfashioned mountain civility, embodying elegant beauty and inspiring communion with nature. A genteel and civilized place, Jasper was a destination that attracted venturesome folks with an eye for natural beauty and a taste for the wilderness.

Traveling in a ’76 Toyota Corolla with two friends, the tiny car packed with camping gear and musical instruments, I wandered across the western

by the most beautiful mountains I had ever seen. I was drawn to it, a flicker of awe-inspiring beauty in the gloom of the warehouse. It was taped to the cart with packing tape, but one day, when no one was around, I furtively removed the card with a box cutter to see the back and learn the location of this jaw-dropping place: Maligne Lake in Jasper National Park.

Jasper was evacuated on July 23 this year as a galloping wall of flame 300 feet high roared across the tinder-dry forests of the Rockies. One of more than 125 wildfires burning simultaneously in Alberta, the fire consumed more than 150 square miles of Jasper National Park. The day it started was the hottest day ever recorded on Earth.

I first visited Jasper in 1978 as a roving college student, part of a 12,000-mile road trip during a long, enlightening summer vacation from school in New Jersey. It was a golden and carefree time, where the route and schedule were mostly dictated by happenstance and good fortune.

US. We eventually found ourselves in the Canadian Rockies, a place I knew I had to go on this meandering journey.

The inspiration was provided by a postcard. The previous summer, on a break from college, I took a miserable job at the warehouse of a hardware distributor in the bowels of New Jersey. A cadre of middle-aged women were ‘order pickers’ who pushed picking carts up and down the aisles to fill orders. They’d all been there a long time and were clearly halfcrazy from the experience. To brighten their dreary days, they covered their carts with taped-on pictures of family, pets, flowers…and postcards.

One particular postcard on one particular cart caught my eye: a picture of a brilliant turquoise lake surrounded

Six weeks into my road trip that first visit to Jasper was like a dream. I saw the Northern Lights for the first time (on the fourth of July, no less). I saw my first moose and grizzly bear. We pulled into the town of Jasper at dusk, and I can still remember the glow of window light as the surrounding mountains faded into the night.

The next day, we met some girls who worked for the park and smuggled us into the employee dormitory so we could take long-overdue showers. We bought warm croissants at the Jasper Bakery and hung out on the vast lawn of the Jasper Park Information Center, a beautiful building made of stone, the source of backpacking permits. We relaxed on the grass and played guitars, making music with fellow travelers. Such inspiring bonhomie! I fell in love with Jasper that morning.