ADVENTURES NORTHWEST

and dive into the extraordinary in Blaine by the Sea.

Art, Adventure, and Seaside Charm Await.

Unveil the winter magic of Blaine by the Sea, a hidden gem on the breathtaking Salish Sea. Dive into a coastal charm with art galleries that tell tales of the seascapes and vibrant downtown murals by OverAll Walls. Step into a world of creativity and culture at the new Blaine Art Gallery, where every visit is a masterpiece in the making. Join us for our monthly 1st Friday Downtown Art Walks, an inspiring evening filled with local artists showcasing their talents, free complimentary wine tastings tantalizing the palate, and delightful local treats celebrating Blaine’s unique flavors. Indulge your senses with our exquisite farm-to-table global cuisine. Stroll through Blaine’s charming boutiques, where each shop is a treasure trove of unique finds. For the adventure enthusiast, our full-service marinas are the perfect launchpad for your next seafaring adventure. Make it a weekend; stay at Semiahmoo Resort, a casual Pacific Northwest beachfront getaway. Discover Blaine by the Sea, and let your seaside enchantment begin!

Plan your Blaine by the Sea winter getaway today and discover the joy of a refreshing change of pace. 40-minutes from Vancouver, BC • 2-hours from Seattle • Seconds off 1-5, Exit 276 at the US/Canada Border

Upcoming Blaine Events

1st FRIDAY OF EVERY MONTH

Downtown Art Walk with Free Complimentary Wine Tasting with Treats

NOVEMBER 30, 2024

Holiday Harbor Lights & Night Market & Illuminary Walk

MARCH 14, 15 & 16, 2025 22nd Annual Wings Over Water Northwest Birding Festival

My Dog Sighs mural on Blaine Art Gallery’s outside wall at 922 Peace Portal Drive, downtown Blaine.

PhotoRuthLauman

EXPLORE, UNWIND, REPEAT AT SEMIAHMOO RESORT

Semiahmoo Resort, Golf, and Spa provides an authentic Pacific Northwest experience for everyone. Feed your outdoorsy soul with bike riding, birdwatching, and seaside strolls. Then hit the links at our award-winning golf course or unwind with a relaxing spa treatment. Finally, grab your friends and family and taste the farm-fresh bounty of the region expertly crafted by our culinary team.

Adventure's NW is half page, 7.5 x 4.625 inches, 300 dpi, high res pdf preferred, fonts embedded, printer settings 'universal coated'

Enchantment awaits.

In Skagit Valley, winter casts a magical spell, transforming fields into a glistening wonderland. The air fills with the scent of woodsmoke and laughter. Become enamored with nature while viewing graceful wildlife and winter birds. Beneath a starry sky, whispers of enchantment invite all to explore the beauty and mystery of this serene season. Plan your visit now!

Photo by John D’Onofrio

A hidden gem kind of place… where the air turns crisper, the snowflakes pirouette from the sky, and even the squirrels wear tiny mittens. You’ll find yourself savoring comfort food, surrounded by crackling fireplaces and the twinkle of fairy lights. Pack your warm layers, grab your sense of wonder, and get ready to undiscover Idaho.

CONTRIBUTORS

Mark Bergsma has been a working photographic artist for more than 40 years. “Solitude” is from a series of work created during a snowshoe tour of Artist Point in March of 2024. His photographic journey has had a profound effect on his life. Visit him at markbergsma.com

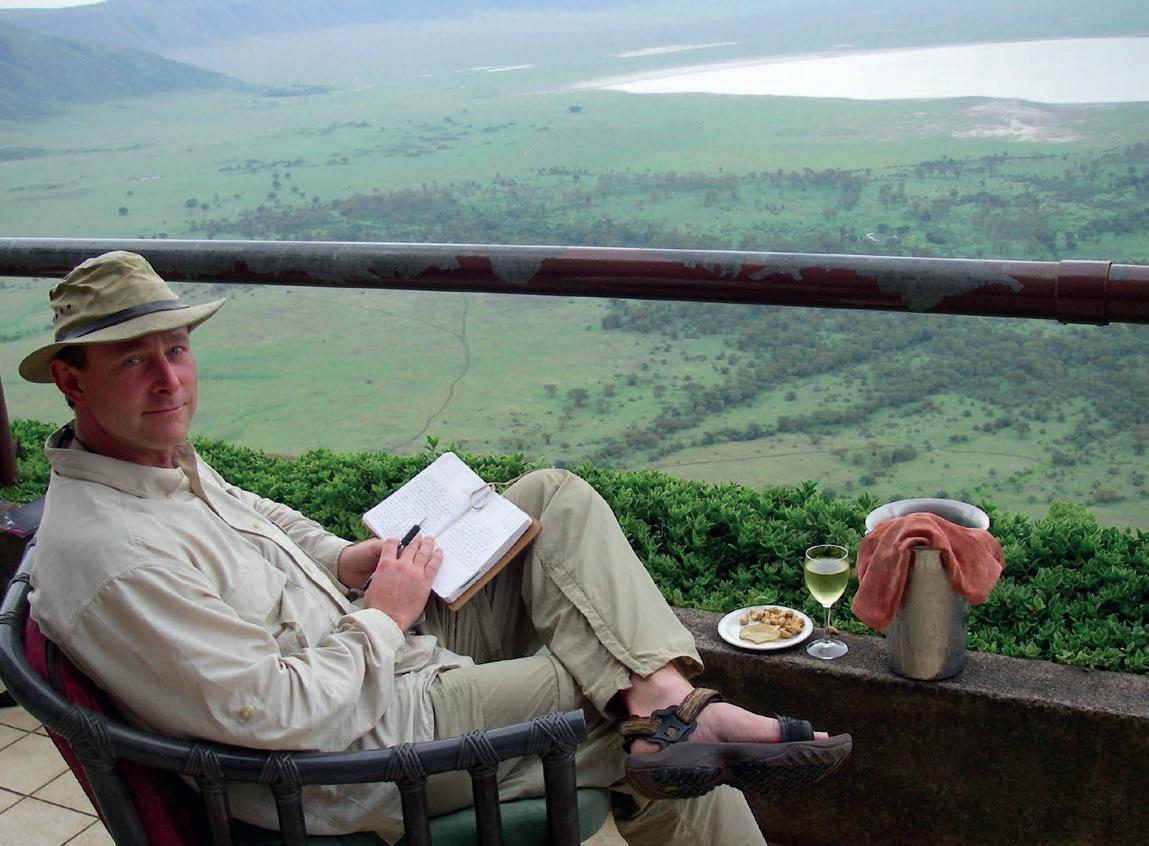

Poet Nancy Canyon, coaches for The Narrative Project and teaches writing for Chuckanut Writers. Her books Saltwater, Celia’s Heaven, Women’s Bodies Women’s Words, and Struck: A Season on a Fire Lookout, are available at villagebooks.com. She lives near Lake Whatcom with her husband, Ron, and her pup, Lucy. A former anthropologist and wilderness guide, Michael Engelhard is the author of the memoir Arctic Traverse: A Thousand-Mile Summer of Trekking the Brooks Range and No Walk in the Park: Seeking Thrills, Eco-Wisdom, and Legacies in the Grand Canyon. After twenty years in Alaska, he again lives in Moab.

Peter Frazier grew up on Chuckanut Bay, where he still lives today. After careers in communications, design, and hospitality, he works with others to build a resilient, thriving Whatcom County. Besides family and friends and the people of the PNW, being on the Salish Sea matters most to him.

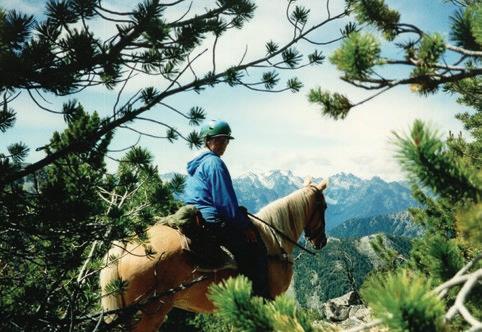

Sharon Hoofnagle practiced veterinary medicine for 37 years in Whatcom County, WA devoted exclusively to horses. She enjoys kayaking, sailing, and hiking. Being on a trail on horseback provides peace and pleasure that balances a busy life. She is a founding member of Whatcom Back Country Horsemen.

John Minier is the owner and lead guide at Baker Mountain Guides. Originally from Alaska, he has a deep appreciation for wild and mountainous places. Since 2004, he has worked across the western U.S. as a rock guide, alpine guide, ski guide, and avalanche instructor.

Tony Moceri is a freelance writer and the author of A Wandering Mind who lives in the foothills of Mt. Baker. In his free time, Tony enjoys exploring the world with his wife and daughter. You can find more of his writing at www. tonymoceri.com.

Born and raised in Skagit County, WA, Wyatt Mullen is a landscape photographer and science communicator interested in the impacts of climate and weather on alpine regions. He spends much of his time trail running, skiing, and backpacking throughout the greater North Cascades ecosystem. Visit him at wyattmullen.com.

Tore Ofteness is a native of Norway, grew up in Seattle, and studied commercial photography at Seattle Community College before moving to Bellingham, where he has enjoyed a career as a freelance photographer. He has been honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Professional Aerial Photographers Association International and a Bellingham Mayor’s Art Award.

Award-winning painter Ron Pattern works most days in his studio in the Morgan Block Building in Historic Fairhaven. His bold landscapes and portraits are shown in galleries throughout the Pacific Northwest and are held in private and corporate collections throughout the US and Canada. For more info: pat-

John D’Onofrio Publisher/Editor john @ adventuresnw.com

Oksana Brown Accounting accounting @ adventuresnw.com

ternart.net and @ronpatternart Instagram.

Brian Povolny is a retired orthodontist who indulges his love of moving through nature by rock climbing, backcountry skiing, cycling, and windsurfing. A long-time resident of Seattle, he also enjoys writing about his experiences in our beautiful region.

Paul Tolme, the Journalist on the Loose, is an outdoors writer, award-winning environmental journalist, and blogger for Cascade Bicycle Club. He lives with his wife in a Seattle houseboat crammed with bikes, skis, snowboards, kayaks, and paddleboards, but no regrets. His work can be seen at paultolme.com and cascade.org/news.

Lori Vonderhorst was born into a family of graphic and fine artists. After moving to Seattle in 1979, she eventually operated her own graphic design firm, working for public utilities, hospitals, and medical clinics. She retired in 2021 to pursue fine art fulltime. Visit LoriVonderhorst.com to learn more.

Bellingham-based poet Richard Widerkehr’s recent collections of poems are Night Journey (2022) and At The Grace Café (2021). “There are Stars” first appeared in Sweet Tree Review

Onthe morning after the election, I went for a long walk on Stewart Mountain.

Although much of the news was good (Initiative 2117 had been resoundingly defeated), there was, of course, deep concern about the future of our country. I am old enough to remember “civics class,” where as children, we were taught

that the United States of America was the greatest country not just in the world –but in the history of the world.

The truth, it turned out, is a lot more complicated, but despite the many shortcomings and shadowy subtexts, the United States has offered a great deal to those who live here and around the world. I’m no Pollyanna—inequalities and injustices have always been with us, and endemic income disparity continues to cripple our society—but still, we have primarily been a nation of people who cared about each other and the common good. It is in our bones.

leaving what Abraham Lincoln called, “our better angels” behind. A time when self interest has—in many quarters— eclipsed our concern about the common good.

What can we do? We can refuse to lose hope, to become cynical, to “go to ground.” Cynicism gives birth to inactivity, and we all must be activists now. The presidential election was won with some 72 million votes. This represents a mere 32% of the eligible voters in this country. A lot of people have checked out. More than ever, we must stay in the game. Be present.

While traveling in Iceland a few years ago, locals asked me where I lived in the U.S. I’d answer, “Washington. The state, not the capital.” and sometimes add, “Nothing good comes from there.” Every time I made this comment,

We need to focus our energy on the aspects of the world that we each touch in our daily lives: our neighbors, our community, our friends and families. We need to be there for each other. And we need to step up our efforts on behalf of

Try Bellingham’s Best Fried Chicken in the heart of downtown

antam Kitchen & Bar started as a spin-off project of Mallard Ice Cream and has become the premier spot for fried chicken in Bellingham. Make your way downtown for an elevated twist on classic comfort foods that will leave you satisfied and coming back for more.

Our upstairs bar is 21+ and our downstairs is all-ages, creating the perfect space for all occasions. Happy Hour is Tuesdays & Thursdays, all day downstairs and 5-6p in the Bookhouse Bar.

2024 Cascades Best Gold - Best Downtown Bellingham Restaurant 2023 Cascadia Daily News - Best Chef: Nick Thompson

&Out About

Opportunity Knocks in the San Juans

The San Juan Islands consist of 172 named islands, a lifetime of places to explore. The Washington State Ferry system will take you to four: Orcas, San Juan, Lopez, and Shaw. That leaves a lot of islands that are only accessible to those with boats, including some of the most beguiling, such as the Washington State Marine Parks, including Sucia, Matia, Patos, Stuart, and Jones Islands, all resplendent beauty spots.

The trip from Squalicum Harbor in Bellingham to Sucia Island aboard Opportunity Knots takes about an hour. “Some of the best times on Sucia are during the winter,” Riedesel says, “when you have the island to yourself!”

Responding to this obvious need, Mark Riedesel and Craig Hougen launched Island Opportunity Charters in March of last year, offering island adventure-seekers a way to enjoy these spectacular islands. Their brand new Munson landing craft (aptly named “Opportunity Knots”, equipped with a heated cab and an enclosed head, transports up to 12 passengers to and from the islands, providing year-round access to our remarkable marine parks for both day and overnight trips.

Hougan and Riedesel have deep connections to the water; Hougan has been running boats in the San Juan’s since he was 8 years old, and Riedesel began a lifelong love of fishing in a skiff with his dad. Between them, they figure they’ve been on the water for a combined 60 years. Their passion for working on the water has paid off. Riedesel and Hougan have logged more than 21,000 miles in the islands in the year and a half since launching Island Opportunity Charters—a lot of work but a labor of love.

More info: www.islandopportunitycharters.com

Fire & Story

As local events go, Fire & Story captures the essence of Cascadia like no other. This threenight event brings together poets, authors, storytellers, performance artists, Coast Salish, Lummi Nation, and Nooksack Tribal members, fire dancing, comedy, live blacksmithing, glass sculpting, puppets, illuminated light art installations, and acoustic musicians—all gathered around architecturally fabricated wood fire pits on the Bellingham waterfront. Fire & Story launched in 2024 and is a project of Paper Whale, a Bellingham-based nonprofit dedicated to activating underutilized spaces with aesthetic integrity and visual diversity. “This unique wintertime offering is designed for the community to come together during the darkest days of the year for song, story, and lore to celebrate cultural elements in the Pacific Northwest,” explains Paper Whale executive director and cofounder Nick Hartrich.

The festival is free, and all ages are welcome. This winter’s event will be held January 23-25 on the waterfront between the Granary Building and the Pump Track.

More info: www.paper-whale.com

Acupuncture and Eastern Medicine

Find balance, harmony, and overcome health challenges so you can keep living the life you love.

Opportunity Knots Photo courtesy Island Opportunity Charters

Beside the Fire

Photo by Mataio Gillis/@fotomataio

Whatcom Art Guild opens New Art Center

The Whatcom Art Guild (WAG) has been a part of the local cultural landscape since 1964, growing from 19 founding members to more than 100 today. Dedicated to showcasing local artists and craftspeople, the Guild has operated the Whatcom Art Market since 2010, providing gallery space to an eclectic mixture of painters, photographers, sculptors, woodworkers, glass artists, jewelry makers, textile artists, and more.

The Art Guild recently announced the opening of the Whatcom Art Center, located next to the Art Market in Fairhaven. Offering art studios, art classes, workshops, and exhibition space, the Art Center doubles the footprint of the Art Guild, providing local artists and art students with an expanded presence in the vibrant art community of Bellingham and Whatcom County.

The new Art Center builds on a robust legacy of creative involvement by the artistic community, with support that has remained enduring over the decades. Painter and WAG member James Williamson believes this energy is largely inspired by the beautiful landscapes surrounding us in Cascadia, describing much of the work produced by WAG members as “artwork for those who live in or yearn for the Pacific Northwest.”

More info: www.whatcomartmarket.org

3 Great Hikes for Winter

Marymere Falls

Located near Lake Crescent in Olympic National Park, the short hike to Marymere Falls offers a delightful walk through a verdant rainforest. Along the way, the trail passes through a botanist’s dream: a garden of mosses and ferns beneath a majestic canopy of ancient trees. Viewpoints afford views of the rambunctious falls from above and below. Choose both. The total distance is less than two miles, and the elevation gain is a mere 500 feet, so bring the kids.

Trailhead: Drive Highway 101 west from Port Angeles to the Storm King Ranger Station (Milepost 228) on the shore of Lake Crescent. National Park Pass Required.

Horseshoe Bend

Looking for an infusion of green in the depths of a grey Cascadian winter? Look no further than the Horseshoe Bend Trail. Follow the boisterous Nooksack River upstream along the moss-dripping rainforest lining its shore. The air itself seems green. And if you’re lucky—and the clouds part—you’ll get a tantalizing glimpse of the snow-covered high country. If you walk to the end, you’ll have covered a scant 2.5-miles round-trip, but if you take your time and stop along the way to contemplate the river’s flow and listen to the water music, it might take you a while—time well spent.

Trailhead: Drive Highway 542 (the Mount Baker Highway) east from Glacier. Park in the pull-out on the south side of the road, 2 miles past the Glacier Public Info Center, east of the bridge between mile markers 34 and 35 (opposite the Douglas Fir campground entrance). No permit required.

Happy Creek Trail

This little loop trail is aptly named. Covering only a third of a mile, this boardwalked excursion through towering cedar beside a mossy stream is more of a stroll than a hike. But it offers big-time sensory delights and is great for the little ones. At the halfway point, a side trail heads to Happy Creek Falls, a rougher uphill mile. In winter, the North Cascades Highway is closed approximately a half mile west of this trailhead, necessitating a bit of a walk along the road to reach it and creating opportunities for solitude.

Trailhead: Drive the North Cascades Highway (WA-20) east to the trailhead between MP134 & 135. If the highway is closed for winter, park at the closure and walk a short .5 mile up the highway to the trailhead. No permit required.

Grandeur of Nature/Mt. Baker Painting by James Williamson

Photo by John D’Onofrio

McRory

The Quietest Sound

Story and Photos by Stephen Grace

The Olympic Peninsula has the best place names of anywhere I’ve lived. Humptulips. Hamma Hamma. Wynoochee. Duckabush. My favorite - Dosewallips.

At the end of autumn, when a window of clear weather opened, I traveled on a road alongside the Dosewallips River. Several years ago, a stormswollen flow pulverized a stretch of pavement, closing the route to motorized vehicles. After packing camping gear in panniers, I pedaled my old steel frame bike on the remnants of the road,

its bed buckled and broken, its surface green with ferns and moss—a route the forest was slowly reclaiming. Where the river had erased the road, I got off my bike and pushed it up a bypass around the washed-out section. At the road’s end, where a trail led into the wilds, I pitched my tent beneath a canopy of Western Redcedars and Douglas-firs. Bigleaf Maples with their yellow leaves, and Vine Maples, bright with crimson foliage, insisted that the season was fall. But the frost that stiffened the ground spoke of winter.

Maybe all the solitude I enjoyed on this trip addled my brain, but the

Olympic wilderness seemed rife with spectral effects. The sound of spilling water in the Dosewallips echoed off boulders like murmuring voices in a monastery. The river ran clear where it sheeted over rocks, and the flow stalled in pools so green they made a mockery of moss, pools so blue they stole attention from the sky. Deep within a forest crisscrossed by shadows, trees groaned and screeched as they rubbed their trunks together and entwined their limbs. While staring at a splintered stump, I imagined the sound the wood had made as it cracked—centuries of silent growth released in a single

Bigleaf Maple

thunderclap.

A Canada Jay startled when I moved from the forest into a meadow, its wings brushing the still air, the quietest sound I had ever experienced. But then I heard a silence deeper yet. Ice as thin as cellophane wrinkled and cracked as I walked on the bank of a brook.

Kneeling next to the frozen violence of a waterfall, I listened to the hush that had replaced the roar of raging water: silence distilled into ice.

view of the tallest peaks. But in the valley below, maples glowed golden. Their leaves ignited at dusk while I descended as if the world had taken time to light torches to show me the way as I returned to camp on this brief autumn day.

A path through an elfin forest led to a ridgetop plastered with snow. Peering over an edge, I saw a basin slowly flood with clouds. The summit of Mount Constance disappeared—a mass of stone erased in an instant by shifting weather, making the mountain seem as ephemeral as a thought. Suspended ice crystals refracted a spectrum of rainbow colors inside the space left when Mount Constance vanished behind the clouds. Snow crunched beneath my shoes as I walked inside a cloud. I breathed deeply, inhaling vapor that had risen from rivers and oceans, and droplets exhaled by trees and whales. Winter clutched the high country in its cold grip, and clouds denied me a

As a young man, while desperate to understand the world and my place in it, I had traveled to the Himalayas seeking enlightenment. I don’t remember what I learned in the mountain kingdoms of Asia. If I glimpsed an eternal truth back then, it had vanished like Mount Constance in a cloud.

Just before reaching my tent, a realization stopped me in my tracks. I sat on a log and listened. I can’t recall what the Buddhist monks had told me, not because my memory is dimming with age, but because back then I hadn’t learned to listen. Now, my mind, worn down from three decades of questing, constantly moving forward and hoping for some revelation around the next bend, I could finally sit still in a forest and hear the wild silence. And the forest spoke a simple truth: my life is one among many, and the many lives are one.

In the distance, the Dosewallips flowed.

Dosewallips

The Trajectory of a Dream: Rediscovering Mt. Stuart

Story by Brian Povolny

Ihad a dream that lasted 24 years, one that drifted in my subconscious like a satellite in orbit revolving patiently, waiting to be activated. Only now can I see how round and symmetrical the dream was, how it would inevitably return to its origin.

I was nineteen when I first saw it. After four days of driving westward to my new home in Seattle, I stopped at Indian John Hill Rest Area on I-90 to infuse my hemorrhaging Corvair with oil. Excitement had been building for several hours as I approached the Cascade Mountains. Born in Ohio, I had only skied on teeny midwestern hills. The idea of skiing on a ‘real’ mountain thrilled me, and I could scarcely imagine what it would be like to live just an hour’s drive from one. As I slammed the hood of my leaking car shut, I noticed a high rocky peak in the distance, overshadowing its neighbors, clearly visible over the intervening hills.

parked next to me, who seemed also to be looking at the mountain, what its name was. I have no idea why I thought this

fellow would know. But he did.

A snowfield floated improbably near the apex of the jagged summit. I was immediately drawn to this peak and asked an elderly gentleman in a Winnebago

“That’s Mt. Stuart, son,” he replied and went on to provide detailed statistics about the peak: its elevation, granitic nature, its rank as the second highest nonvolcanic peak in the state, and, finally, its defining position in the Stuart Range.

Everything he said heightened the allure of the distant mountain. After he

drove away, I sat on a picnic table and daydreamed of an excursion to the evocative peak. How to approach or ascend it was not part of my thoughts. Certainly, I was not a climber and would not have known what to do with a rope or an ice axe. Nor would I have known what backcountry skiing was since determined outdoor people had not yet rediscovered it. There would have been no way for me to imagine skiing along the highest ridge of this peak, or jumping onto the exposed snowfield that shimmered so marvelously that summer evening in 1971. Yet now, having done these things, I think my amorphous fantasy was to simply ski from the summit of Mt. Stuart.

Mt. Stuart’s reputation places it in a select group of striking peaks, impressive with great relief and complex walls of granite, ice, and snow. You won’t often find skiers on the mountain, but climbers covet dozens of its high-quality routes. Most aspiring Washington climbers eventually attempt this peak by one route or another. The south side has numerous rock and snow routes, which appeal to peak baggers because they’re not too

Painting by Tim Ahern

difficult. Likewise, serious alpinists have long considered the mountain’s north side, especially the North Ridge, a rite of passage. Mt. Stuart has something for everyone. Mountaineering legend Fred Becky called it the “crown peak of the north central Cascades.” Professor W.D. Lyman described it as a “dizzy horn of rock set in a field of snow.”

Without any intention on my part, Mt. Stuart became my first mountain crush, teaching me all the inaugural lessons of mountaineering. In 1973, while wandering around the old REI store on 11th Ave in Seattle, I saw an ad for a climbing course and signed up. It turned out Mt. Stuart would be the class’s location. There were just two students. We learned rudimentary mountaineering skills and lived in a snow cave on the Sherpa Glacier for a week. We climbed to the summit on the final day, and I was hopelessly hooked. Back home afterward, my pulse would quicken when I imagined the contours of upper Mountaineer Creek on Stuart’s north side or the fantastic granite needles that stood on its subsidiary ridges, or the pocket glaciers cascading off its immense north face. Within a couple of years, I achieved many climbing milestones on Mt. Stuart: first major alpine rock climb, first technical ice, first planned bivouac, first unplanned bivouac. In those first years, it seemed that Mt. Stuart would encompass all the climbing I’d ever want to do. I would never desire another mountain and be forever content to scale its ridges, faces, and ice falls.

fact that I was less interested in alpine climbing since my main object in traveling to large mountains had now become a need to ski down them.

I focused on the peak with a different eye this time. From where I stood, the entire upper mountain was snowy. I instinctively imagined a descent route, visualizing a path from the summit to the false summit and then down Cascadian

Couloir. You could ski Mt. Stuart! Why had I never considered it before?

skis is a revelation. The thought of skiing my beloved Mt. Stuart made me giddy. It is 4 a.m. The sleeping city is empty of activity, like a forest before a storm; birds and insects mute. I think about the multitudes sleeping right now and realize that very few would join this attempt to ski Mt. Stuart in a day. My companion Frith took my suggestion no more seriously than an invitation to go for a jog in the park. No problem, of course, she’ll go. As we leave the dark city, I try to picture the progression of our upcoming climb, but I can’t because there are too many unknowns. Where will the snow level be? Can we ski from Longs Pass to Ingalls Creek? Will conditions allow for a fast ascent? Will the snowpack and the weather remain stable? I wonder where we’ll be as darkness once again falls over the city.

Yet, driving west on I-90 in March of 1995, I gazed again at a very snowy Mt. Stuart and realized that 12 years had passed since I was last on the mountain. How could it have been so long? Perhaps the changes that come with passing years, unimaginable to my younger self, had preempted the youthful passion. More likely, though, was the

One of the rewards of mountain travel is developing an intimate knowledge of a great natural eminence. As a climber, you study the micro and the macro: the handhold in front of your nose, the weather generated by the peak thrust into the atmosphere. A climber moves slowly, the better to contemplate secret little places, but must rely on mental pictures for an overall view. Now imagine being a bird, perhaps a hawk. You can fly around the mountain in minutes, see everything in real time, land anywhere you like. Get a lay of the land by charting your flight path right over it. That’s skiing. You climb the peak, then swoop down, surrendering freely to the pull of gravity, feeding off the energy inherent in the mountain; your descent completes the knowledge gained on the ascent. Hiking down a mountain in boots is a sentence, carried out one trudging step at a time, but descending the same mountain on

We exit the car at 6 a.m. The roar of a stream, which forms a small cataract next to the parking lot, fills the air with white noise. As we start hiking, we are curiously alone, each in the solitude imposed by the waterfall like a couple wearing earbuds who automatically go about independent yet complementary tasks. The smell of fir trees and cool morning air is bracing. In minutes, we reach snow and put on skis. Soon, we are gliding upward over frozen snow. Progress is good; we leave the forest in less than an hour and approach Longs Pass. As we crest the pass, one last step takes us from frozen pre-dawn into the warmth of morning sun. I look across the Ingalls Creek Valley to the awesome panorama of Mt. Stuart. My God, it seems so huge!

Two and a half months have passed since I viewed the snowy mountain from I-90 and resolved to ski it. Today, the

Mt. Stuart

Photo by Brian Povolny

ridge connecting the false summit to the summit is all rock. We’ll have to leave the skis at the top of Cascadian Couloir, scramble to the top, and abandon the plan to ski from the summit. I feel robbed like someone just ruined a good novel by telling me the ending. In desperation, I scrutinize the mountain for alternatives. To my surprise, one jumps out immediately: Ulrich’s Couloir.

A revelation! Forget about Cascadian. The only way to really ski Stuart is Ulrich’s. I see now that it’s the only continuous snow route to the true summit. That shimmering snow field I first saw in 1971 is actually the upper slope of Ulrich’s Couloir.

Describing Ulrich’s, Beckey writes, “This prominent couloir, about 4000 feet high, bites into the south slopes of Stuart, and higher curves westerly to reach the summit in an uninterrupted sweep.” Ulrich’s is steep in places as it snakes its way upward through granite canyons. Later in the season, it presents difficulties

like cliffs, rockfalls, and waterfalls, but now it’s all snow.

The actual climbing route ascends a slope immediately to the east of the main couloir for about 1500 feet, then traverses into Ulrich’s, thus avoiding the largest cliff in the lower reaches of the true couloir. The whole damn thing appears to be skiable—a terribly exciting prospect!

We strip skins off our skis and jump the little cornice at Long’s pass to ski down into the Ingalls Creek Valley, which drains the immense, deeply furrowed south slide of Mt. Stuart. Wide GS turns down the bowl below the pass bring us to woods where we encounter a party who had climbed Stuart a day earlier. They quiz us about our experience. Do we know how to climb? Do we have the proper equipment?

“We’re skiing,” I tell them to calm their fears that we might try to climb the mountain without adequate preparation. As we continue past them, I experience the unholy sense of superiority that skiers

secretly feel when they pass hikers.

Soon, the snow gets patchy. We pull off the skis and strap them to our packs, cross Ingalls Creek on logs, and moments later we’re kicking steps up Stuart itself. The snow is softening, and I fear that progress may be slow. Luckily, someone had kicked steps two or three days ago. Just before crossing into the couloir proper, we climb a section without steps and find ourselves struggling in knee-deep snow, post-holing with each step. Frith leads this section and soon we traverse into Ulrich’s Couloir.

The couloir steepens, eases, and steepens again as it twists up Stuart’s deeply eroded face—towering granite walls on our right form a little summit at each turn. I am amazed at the number of good rock-climbing routes on these walls but remain confident that no one has climbed them because they each end on just one of an endless series of pinnacles.

There is no breeze deep within these walls, and it is getting hot. Even though we’ve stripped down to minimal clothing, we’re still drenched in sweat. Places where snow has recently funneled down the gully, are hollowed out like half pipes. The old tracks disappear, and we make new ones, testing first to the right and then left for the best snow. We carry ice axes, but ski poles prove to be the best climbing aids.

After a couple of hours of climbing, we rest. Looking up, I see the couloir turn to the left and broaden. Could this be the summit snowfield I’ve been looking at all these years? We hear faint voices from somewhere up on the ridge connecting the false summit to the true summit, so we must be close. Energized, we strike out again. The final face curves upward in a parabolic gradient that demands front pointing with our stiff ski boots to crest the final section. Then, a few steps up a gentle ridge lead to the summit. It’s a beautiful day, with the air still. A few cumulus clouds drift over the surrounding peaks. We relax for a few minutes on the summit rock, snapping pictures and gloating over our successful climb.

I make a point of putting my skis on for the descent at the highest possible point of snow, a childish gesture that makes sense only to me. I will go first, and Frith will follow on foot once I have stopped below the upper face at a safe point where she can put on her skis.

few fast turns. Now it’s time to jump into the summit bowl. The snow is getting saturated with water, so I decide to ski-cut the entire face on my first traverse. Heart pounding, I leap over the edge and traverse across the summit snow field, jumping up and down on my skis to loosen anything ready to go. The surface snow sloughs as I traverse, but just the top three or four inches cut loose and slide. I do a jump turn and ski back onto the slowly moving molasses, pass through it, and stop on the far side of the slope. I take in the scene: a strange mixture of the mythic and the mundane. The entire snow field is sloughing before my eyes, a common enough sight in spring conditions. But this is Stuart’s summit, visible for a hundred miles! Professor Lyman’s field of snow is shedding its skin right off the dizzy horn of rock! Someone at the Indian John Hill rest stop could be watching this happen right now.

Is this a fantasy from which I’ll awaken? No, this is real, and for the next hour, Mt. Stuart belongs to me, dream lover of two decades.

The ski descent never threatens, but continually challenges. Jump turns put me at ease in the steepest sections, and the glopalanches move at a sluggish pace. The snow surface revealed by the sloughs is actually good corn snow, where ski edges easily bite. Frith dons her skis below the steep upper section, and we create a pas de deux on the lovely white stage, figure8-ing one another’s tracks and yelping

with joy. It’s obvious that we’ll have no problem getting back before dark. The skiing is simply fabulous. I’ve never skied anything like this 4000 feet of steep, twisting granite canyon. I wouldn’t even know where to look for a comparison. Maybe the old guy at the rest stop, who seemed to know so much about Mt. Stuart, could point out another equally enchanting peak somewhere. Or maybe for him, there was just one real mountain love, and that was Stuart. Perhaps he had climbed the mountain years earlier and was remembering something special about that adventure when a kid in a Corvair interrupted his reverie to ask if he knew the mountain’s name.

PEAK EXPERIENCES

By John Minier

In Defense of Simplicity

One of the benefits of spending time in the mountains is the opportunity to escape from the constant barrage of distractions, silence the chatter, and find time to reflect. Recently, I found myself contemplating the role ‘prosperity’ plays in my life.

I have been ‘rich,’ and I have been ‘poor,’ and if given the option of one or the other, I choose poor. In fact, some of the happiest times in my life have been when I had the least or lost the most. Living with only a little requires a certain amount of letting go, and letting go requires trusting that the universe will provide what is needed when it is needed.

It’s not the “having more” that I dislike; it’s all the baggage that comes with it, the expectations layered on top of all the striving and effort and the need to control the outcome. It’s the anxiety disguised as ambition and the happiness that is fully dependent on external factors. It’s exhausting.

Being poor reminds us about what is most important in life or, more specifically, who is most important. It forces us to cultivate relationships, to lean on one another, and to trust each other. When we have nothing left to give, we often discover which relationships are genuine, and hopefully, we are reminded that we are worth more than what we can simply produce or provide. A good conversation or a warm embrace becomes the best part of your day. But the truth is that such little moments were always the best part of your day. You just forgot for a while.

When we can no longer distract ourselves with things, we often rediscover the world around us. We remember there is nothing as exciting as simply being here in this moment, in whatever beautiful place we are privileged to inhabit. We remember to get up early to watch the sunrise, to swim in cold water, and to walk amongst the trees. We remember the excitement of the first snowfall and how very good it feels to move our bodies in whatever way we find most appealing. We remember that the greatest relationships we can have are with ourselves and with the world around us.

Photo by Leyla Helvaci

The Light at the end of the tunnel

Cathedral of Ice

Story and Photos by Michael Engelhard

Istep from the truck among 20 other cars, and an arctic wind knifes me within seconds. Weather always funnels like tides through this bottleneck, one of few gaps in the Alaska Range. My brow hurts with an ice-cream headache, and my hands are numb. I forgot my down jacket and borrow a flowery fleece from a friend who drove an hour from Fairbanks with her family in their vehicle. I’m now wearing socks inside mitts and a skimpy hat atop bulky upper layers, which, in the truck window’s reflection, makes me look pinheaded and decidedly fashion-challenged.

We chose a cold day on purpose because lace forests grow in the depths of Castner Glacier only at freezing temperatures. The gloaming bathed the snout of nearby Black Rapids Glacier in azure color, which spread across the Delta River.

The low sun struggled to part the milling scud. My wife and I smile when, igniting a lone summit, it succeeds.

The air calms the moment we drop from the pullout into the bed of Castner Creek, the glacier’s outlet. Inky water rushes under ice panes crashed at an overflow. Tracks hint that a snowmachine foundered here. The procession spread out ahead includes dogs, snowshoe enthusiasts, a kid towing a sled. Walking the well-broken granular trail is like plodding in sand, so I quickly warm up. Still, moisture from the balaclava stuck to my beard quickly rimes my eyebrows and lashes. A fogbow fragment glows at the base of decapitated peaks at our back. Ptarmigan tracks meander drunkenly

between willows, past a rust-and-silver schist boulder of folded phyllo layers. An occasional imprint of fingered wings shows where the ghost birds took flight. Fox pugmarks flesh out the tale.

My fellow sightseers are elated yet subdued, and everyone seems relieved to have escaped their dens and the doom cycle of bad news and voting fraud rumors. It’s mid-December, winter’s

pit, but we’ll gain minutes, if not composure, once the sun tilts higher again. Stepping off-trail for oncoming traffic, holding my breath while hikers pass, I sink up to my knees.

We round a bend about a mile from the trailhead, and the glacier’s terminus looms suddenly. Its mouth is a whale shark’s toothless yawn, larger than expected.

We enter, modern Jonahs, and it

turns into a scalloped cathedral shading from aquamarine to lapis, hues sometimes seen in the Virgin’s mantle. Charcoalgray grit veins walls encasing rocks and snarls of glass vermicelli here and there. Grist from the grinding of eons dusts the surface underfoot. Milky discs dapple it, air pockets arrested till spring.

It’s ten degrees colder inside. My ungloved fingers fumble with the camera. When the last shreds of light surrender to darkness, we click headlamps on. A strange, sacral atmosphere reigns, as in a museum or cathedral. “You must be quiet in the presence of the ice,” Koyukon old-timers in Alaska used to say. “You must show it respect.”

Tlingits and Athabaskan Indians saw glaciers and river ice as both animate and animating the landscape. Glaciers housed fearsome creatures, giant worms or copper-clawed owls. Humbled, engulfed by it, the Castner cave makes perfect sense to me as some creepy-crawly’s lair.

John Muir, a geologist-deist with an animist streak, stood hushed before land ice carapaces, “gazing at the holy vision.” He acquainted himself with glaciers and their work in the West and Alaska to come “as near the heart of the world” as he could. In the Andes, until recently, thousands of campesinos made pilgrimages to a special glacier terminus on an

Coupeville

December 7th - Greening of Coupeville Christmas Parade with the arrival of Santa Claus, Carols with the Shift Sailors @ Cooks Corner Park, Tree Lighting at Cooks Corner Park, Holiday Boat Parade of Lights from the Wharf February 8th 2025Coupeville’s Annual Chocolate Walk

POETRY FROM THE WILD

In The Forest There Are Stars

By Richard Widerkehr

Thick green-black branches can’t hide them, whistling through cedar and fir trees. You’ve seen one star drop as if torn from the forest. The stars jostle each other, falling toward you –you forget what you were and how you came here. Maybe by day on the road to the islands, you drove past high bluffs to the end of a sandy spit, skimmed over the white edges of rooftops. Here sword ferns jut from the hillsides.

High fern-like branches fan themselves downward, and stars soak you with their cold radiance.

The stars that were small and cold

In the sky are still small and cold. The branches Lift about them, hissing lightly in the dark.

annual feast day, harvesting ice blocks ceremoniously. Peruvian peasants, who rightly implicated modern technology, blamed a drought on instruments that measured glacier-ice loss. Awe and the sacred, in general, always have carried notes of fear, the risk of being overwhelmed. Clusters ooh and aah, together but alone, each steam-puffing social bubble percolating separately. Pale beams pick out random details. Enchanted voices

Photo by Lance Ekhart

Ice crystals growing from the ceiling

echo dully, muffled, and ringing at the same time. One guy is ice-skating— it was on his bucket list, he tells someone. A thin ten-yard fracture makes me question the rink’s soundness.

Farther in, sprays of foot-long hoar frost feather above us, serried sequins sparkle like transparent razor blades. A boy knocks down a glitter shower. His father asks him to stop. Exhalations in ice-age caves housing murals of lions and bears corrode the art. Visitors’ breathing in this alpine fridge builds it. In a likely future, however, such wonders could soon be history. Although the Castner retreats much more slowly than neighboring flows because of our species’ collective vapors, it thins almost as fast. This isn’t foremost an aesthetic problem, of course. Warm-blooded life in a glacial vault is as common and as comforting a thought as fallback Earths in outer space.

the ceiling descends. I accidentally brush against hanging crystals. Gully rumblings of water in some deeper, even less knowable places sound ominous.

Time to resurface.

The whale shark throat tightens as

With our perspective reversed, human figures appear as black cutouts, backlit by the blinding-white exit. Step by step, Devil’s Thumb across the valley materializes inside a royal-blue archway.

The plunging afternoon sun pinks its ridge—the light at the end of the tunnel. Until that year, that very instant, with the end of the pandemic and Trump’s reign in sight, I’d never experienced or really grasped this metaphor born in an era of steam trains and gaslights. Post-election, the physical climate notwithstanding, with a vaccine at last having been issued, the promise of light, like beauty, kept us going.

Perhaps there could be a world like the one we’ve already envisioned, one where people are not just disease bearers or faceless shapes. One in which glaciers and kindness, wildness and refuge, pikas and civil liberties, can survive.

In June 2022, with Alaska’s Interior thick with smoke from wildfires and sweltering in temperatures above 80 degrees, the Castner ice cave partly collapsed—its front portion was gone, while the back remained. Hikers still ventured there but called it “super risky,” hearing ice cracking and water and rocks raining from the ceiling. My first reaction upon reading about this was, “What if there had been people inside when it happened?” My second: “How can this crystal marvel be gone?” Then, naturally, “Why now?” We assume landscape features will at least endure for a human lifespan.

A recent coinage, “solastalgia,” describes the grieving for dear places that progress has obliterated. It covers habitat destruction ranging from development to flooded shorelines from thawing icecaps. I never knew the Castner’s crypt intimately or even for sure if the spiraling climate caused its demise, but I know snow and winter and ice, and I’ll miss them sorely.

In the pre-digital past, sand running through the fingers of a hand or an hourglass were poignant symbols. Snowflakes melting on the tongue would better serve our thirstier times.

Hikers enroute to the ice cave

The View fromAbove

By Tore Ofteness

Sometimes, rather than capturing a grand scenic vista, a small portion of the vista is more interesting. These photos depict the abstract beauty of our region from above, an unfamiliar viewpoint that captures the striking patterns and vivid colors of our beautiful local landscapes.

The photography of Tore Ofteness will be on display at the Allied Arts Gallery December 6-20, as well as at Quicksilver Photo Lab and Bellingham Frameworks, all in downtown Bellingham, WA. The opening Reception at Allied Arts (1418 Cornwall Ave., Bellingham) is on December 6.

Tore’s book, A Higher Perspective: Aerial Photography of the Pacific Northwest, published in 2017, is available at Village Books in Fairhaven.

Visit AdventuresNW.com to view an extended gallery of Tore’s aerial photography.

Left Page, Clockwise from Top: Nooksack Delta; Golden Fog, Skagit Valley; Nooksack Delta 2; Nooksack Tides; Nooksack River Delta

Right Page, Clockwise from Top: Islands in the Sun; Boats on the Bay; Nooksack River Delta 2

On Horses, Humans, and the Trail Ahead

My horse, Joey, and I were nearing the top of a ridge, glad that the last 15 miles back to the trailhead were downhill. The area had changed since our previous trip many years ago. Although fires had devastated the forest, in its aftermath it had left vast vistas and fields of wildflowers. As we approached the ridgetop, mountain peaks towering above us, we were startled by a rushing sound coming from the ridgeline above, soft at first, then expanding into a bellowing wind that filled the air around us. Joey looked over his shoulder at the mountain tops. I felt a twinge of fear until I realized he was not afraid. Suddenly, he answered the call of the wind with the loudest, longest whinny I have ever heard. He called, and called, over and over, his whole body trembling with the effort. The wayward wind filled me with awe as it called, and my horse called back. When the wind gradually died, I softly said, “Joey, we can’t go with those horses in the sky, maybe someday, but not today,” and we headed down the mountain.

Story by Sharon Hoofnagle

our rides together are far less dramatic, but they almost always end with peace and tranquility. So, what is it about horses, humans, and trails? How did

wards others. Dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin are euphoric hormones that result in happiness, bonding, kindness, and empathy, including compassion and understanding for others, allowing us to relate to people and animals successfully. It’s not just what we are saying to others that is important, but how they interpret it. These feelings are picked up by humans and animals, resulting in the release of the same hormones, a happy contagion. Endorphins are natural brain chemicals that act as nature’s painkillers and reduce stress by moderating the adrenaline rush, helping to avoid injury.

How I ended up on that ridge alone with my horse is another story. Most of

they develop this incredible awareness, this profound bond with us? The short answer is that it’s mainly chemicals and brain circuits. But it’s also something else.

Both horses and humans are herd animals. Neither can survive without the herd. So, nature devised some incredible survival tools, such as hormones. They are our body’s chemical messengers, and once released by glands into the bloodstream, they control everything—from how the body functions to how you feel.

One group of hormones is nicknamed the “feel-good do-good hormones,” not just due to the happy and euphoric feelings they produce but also the altruistic feelings they engender to-

The endocrine system that produces hormones works with the nervous system to influence many aspects of behavior. The autonomic nervous system kicks in during times of danger or high excitement. Adrenaline shifts blood flow from non-essential areas to the muscles and heart, allowing instant flight from danger or increased speed in a competition.

However, there can be a disadvantage to calming chemicals. Sometimes, we are a little too calm. One time, we were slowly moving up a trail. I grabbed berries to the right, and Joey grabbed grass to the left. Feel-good hormones lulled both of us until I was startled by an object just a few feet in front of us. A doe had stepped out on the trail, her mouth full of whatever deer browse

Sharon and Buddy, Pasayten Wilderness

Photo by Gene Gilbert

on. She stared at us with a typical deerin-the-headlights look. She was frozen. I was frozen. Joey had not yet spotted her. Horses and deer typically are not afraid of each other, but this was unexpected, and she was far too close. I knew the next few seconds were going to be very interesting. There was nothing to do but hang on. I knew Joey would spin, but I didn’t know which way. He lifted his head and spotted the doe. He and the doe exploded in opposite directions. Joey spun 180 degrees faster than any competitive reining horse, and I could feel his rear legs flex and prepare to propel us down the steep trail at 40 mph.

he spun. Adrenaline increased the blood flow to the heart and muscles as the horse spun out of harm’s way and prepared to run. But endorphins kicked in, and panic did not overcome him. Recognizing the

The danger from bolting is likely a rider’s greatest fear. A racehorse can accelerate from 0 to 40 mph in just a few feet. Jockeys describe coming out of the gate at a racetrack like being shot from a cannon. Without a good grip on the mane, the horse could leave them behind. Yet they know it is coming and the direction they are going. Picture the trail rider whose horse suddenly sees a terrifying object on a trail. It may be in front, back, above, below, or to the side.

In this case, horse, human, and deer were all flooded with chemicals. Adrenaline allowed us to flee, but endorphins permitted us to remain calm and gave us the heightened awareness that made it possible to deal with the issue. The human realized she should not jump off her horse because he could hit her when

deer, he stopped. The 40-mph downhill dash was averted.

The adrenaline of the sympathetic nervous system propels the racehorse around a track or the bike rider down the trail. Endorphins moderate this, countering panic and keeping the spooked trail horse from running far or crashing into anything. They enable an injured hiker to crawl back up to the trail after falling. These profound evolutionary tools help humans and non-human animals deal with dangers and injury.

We were again on a trail, Joey and I. It was a usual ride; feel-good hormones were high—until we heard something in the brush 50 feet off the trail at the four o’clock position. It was too loud for a

deer and, very likely, a bear. Fortunately, it was behind us; best to keep going. A little adrenaline kicked in, but there was no real concern until we heard a louder commotion at the nine o’clock position. The feel-good hormones evaporated, and adrenaline took charge. We were between a cub and its angry mama. To complicate the situation, the trail went straight for about 100 feet ahead of us but then hooked directly towards Mama Bear, then abruptly north out of danger. Joey and I were in a typical northwest forest with downed trees and challenging terrain. There was no other route.

We hear a lot of advice on dealing with wildlife. Play dead (not applicable here; Joey would not be the least bit interested in playing dead). Look big (I’m a human on a horse; together, we weigh 1100 lbs. and are eight feet tall.) There was little time to do more than react. The message from the mama bear was short and clear: “GET AWAY FROM THE CUB.”

It was interesting riding Joey towards an angry bear. It was the most reactive I have ever seen him, but the bear quieted once we moved away from the cub. The adrenaline level dropped. Relative calmness took over. Some of this is due to the human-animal bond. Joey and I had stayed relatively calm because we trusted each other; there were mutual dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin levels.

In the Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness Photo by Sharon Hoofnagle

Once, we met four runners, running abreast towards us on a road. I felt Joey tense. I asked the runners to slow down with a hand signal. When I thanked them for stopping, they said they didn’t realize that running towards us was frightening to a horse. A biker coming downhill didn’t stop or slow despite my calls and hand signals. When he finally stopped, he explained that he knew to stop but wanted to get closer. He was surprised that both horse and rider could be frightened by his approach. A hiker we met was afraid of horses, so we moved out of his way to give him space. An inexperienced biker didn’t want to stop on the steep trail for fear that she could not get started again. We moved off the trail for her, even though horses have the right-of-way. These are all examples of situations where trail users need to register the issues and

feelings of others. We need empathy and concern for each other.

But we also need plain old education. We need stop signs, speed limits, and one-way street signs in life. And we

and space. Prey animals are frightened by fast-moving objects. A horse’s eye can see a fast-moving object but may not be able to identify it immediately. They are reactive animals; they survive by running away. Their large eyes are positioned on the side of their heads, allowing broad panoramic vision of almost 350 degrees—they can see a lot but may not recognize what they’re seeing. They will run first, then later stop to focus on what the object may be.

often require flashing lights, bells, and drop-gates to get a point across. Some people need to be told not to approach a cuddly-looking bear to pet it.

All creatures exist in their own time

Horses are incredibly perceptive animals that pick up on subtle environmental changes. They have an innate ability to sense energy emitted by those around them. The human’s energy level affects the horse, and vice versa. It seems contradictory, but horses are often drawn to troubled people. Some are quieter when close to an agitated person, which makes them excellent

Riding in the Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness

Photo courtesy of Sharon Hoofnagle

therapy animals. This is the beauty of nature—we can all sense empathy and kindness, and it’s contagious. Horses benefit from the same positive feelings as humans. Although we need to train horses in order to be safe around them, the concept of the human being as the passive leader has replaced the idea of alpha domination, one the horse gravitates to and bonds with. This incredible bonding we experience results from chemicals and

brain circuitry, but there is also something else. Karma? Love? No name can encompass it. The feeling is beyond comprehension.

So, what triggers these feel-gooddo-good chemical reactions? Food, music, cuddling, laughter, exercise, and friendship will do it. But high on the list is relating to animals, spending time in nature, and being on a trail, and for me, riding a horse on a trail just about tops the list.

We can’t make laws or instruction manuals covering all the idiosyncrasies of behavior and situations, especially when other species are involved. But genuine compassion and concern for all living things will cover all the bases. It’s been years since the restless, wayward wind called to Joey and me from the mountaintops, and Joey called back to the wind. To this day, I still feel that extreme awe, peace, power, and joy from those few minutes.

Photo by Bruce Howatt

Dark Beauty

Notes from Winter Sailing Journeys on the Salish Sea

Story

and

Photos by Peter Frazier

Cypress Island

Bellingham

Before casting off, we met friends at the Cabin Tavern. It was dark and wet beyond the cold windowpane but warm and convivial around the table. Ordering at the bar, I told the bartender she wouldn’t see me for some time as I’d be sailing the Salish Sea. “Oh, that sounds great!” she said, likely picturing the summer version of sailing, with warm sun and light winds. I said, “It is great, but there’s a reason no one else is out there this time of year.” Her expression shifted as another rain-soaked patron walked in. “Oh, right,” she said, looking worried. “Be safe!”

Bedwell Harbor

It’s a lovely sunrise, breaking into blue skies, but I am wary. The forecast is for bitter cold and gales over the coming week. It’s a good day to move on, though we had hoped to stay out another week. Winter sailing requires constant readiness—things can go wrong in moments. The responsibility can feel heavy, but that’s what maximizes the joy. I always have two backup plans: checking and rechecking and, above all else, ensuring my guests are safe and comfortable. It’s been this way since I started taking boats around the Salish Sea at age 13. It’s a rush, heading out into uncertain waters. Winter out here is like turning up the volume.

Oak Harbor

shrieks. S/V Selkie heels over in her slip, bucking and straining at her mooring lines. The cleats could part at any moment and dash us into splinters along with the driftwood. I repeatedly don my weather gear and venture into the cockpit to check the lines, putting more fenders

lands to the vanishing point. Ever churning, flinty dark seas. Bedeviled by the scene, words can’t capture what it’s like to be in this moment. They only serve to take me out of it.

Carr Inlet

out, expecting disaster. Wave after wave breaks over the seawall and dashes across Selkie’s dodger and into the cockpit. No sleep. Not for me. Not for the people in the boats across the way. Headlamps bob about in the darkness as they work to save their boats. I wait for dawn to see the damage.

I took cover here just on the inside of the floating seawall. Thirty-mile-per-hour winds were predicted. As the front bears down, though, we have sustained winds of 50 mph with gusts to 75. The docks are grinding. The wind turbine on the boat next to me began to howl and now

Rosario Strait

Captain George Vancouver said, “To describe the beauties of this region will, on some future occasion, be a very grateful task to the pen of a skillful panegyrist.” He was right: The infinity of greys. The low-angled light. The ombre of the is-

No one else out here. No one. Alone so much, I’ve been thinking about my first adventure buddy, Tom, who was like a brother. He was my first companion on the Salish Sea, and he’d have wanted to be here. When we were 11, we survived our first squall together in a rowboat. Now, I realize I’m seeing the beauty and experiencing the action for him, too—since he chose to leave the adventure early. He’d have had 17 more years of all this if he hadn’t done it. I wonder what we’d have discussed tonight over whisky and lamplight. It’s lonely out here tonight.

Peale Passage

Seventeen thousand five hundred years ago, the front edge of the glacier that shaped the Salish Sea came this far south but no further. It stopped right here before retreating, leaving granite boulders from Squamish littered throughout the region, piles of till, sloughing cliffs, gouged seabeds, carved sandstone formations, and endless undulating shorelines. Now, I take shelter in these coves and islands the glacier left behind. Thank you, glacier. Good things take time.

Cypress Island

People have used this beach for thousands of years: eating, drinking, laughing, playing music while pulling their sweetheart close as the night chill creeps in at the fire’s edge. Generations have, like us, shared the same stars and same

sun, while Raven, Heron, and Eagle perch on the rocks and trees around us. Seemingly consequential and historical changes have happened over millennia, but what provides our primary satisfactions doesn’t change and never will.

Job Posting

Needed: Salish Sea Watcher. Help keep countless opportunities of breathtaking beauty and moments of stunning evolutionary magic from going unappreciated. Job requires a quiet mind, an open heart, and willingness to fully utilize any of all five senses. People with disabilities, current troubles, past traumas, broken hearts, and consternation issues encouraged to apply. Training provided by team in supportive atmosphere. Excellent entry-level position, though those with

experience will be considered. Generous compensation packages available to can-

didates willing to dedicate themselves. Please submit your application here, now, as opportunities are unlimited.

Chuckanut Coast

The sea breathes in tides. Big, long

breaths twice a day. I watched her inbreath this morning as she filled her bays and estuaries. At sunset, she breathed out, sending her waters toward the ocean. During the night, she turned and filled again. It has been this way. It is this way. It will remain this way. We can fight it if we want, though it takes a lot of energy, and there’s little to show for it if you do. Kayakers and sailors know that well. Pay close attention to the flow of the currents and eddies as they dance among the islands, shores, and shoals. When we pay attention, traveling through gets much easier and kinder.

Portland Island

Walking the shores and forests here, we came across a long-ago harvested cedar tree, its bark peeled in a long strip.

Cedarbark can be used for all manner of things, from rope and netting to clothing and baskets. People have a good friend in the cedar.

Liberty Bay

On the Fourth of July, Liberty Bay is packed! But today, Selkie and I are alone at Poulsbo’s guest docks, enjoying a welldeserved rest after a long day’s exploration of Dyes Inlet and a spicy sail from Bremerton. She and I were ecstatic with the driving rain and winds behind us. A needed resupply had me walking up to the big box stores and mini-malls by the highway. Like so many other towns along the Salish Sea, Poulsbo only has restaurants and gift shops on its waterfront now—the vestiges of their original business districts when the front of the town was at the docks. In the 20th century, each town turned to face the highway. After a day in the Wild, navigating four-lane roads and the aisles of a mammoth Safeway felt jarring. I hap-

pily returned to Selkie and look forward to casting off in the morning to catch the slack water in Agate Passage.

South Sound

When the English, Spanish, and Americans first explored and charted the Salish Sea, they sailed ships that could barely point to wind, had no engines, no depth finders, no weather reports, no current charts, and were all in competition with one another for

furs, naming rights, staking claims on who should own what, and ridiculous orders and expectations from their superiors. They hit reefs, were becalmed for days, went aground, died of scurvy, were shot to and fro by currents, and lost rank for difficulties beyond their control, all while far from home on a voyage they had a good chance not to survive. The indigenous people must have watched in wonder at this strange mix of incompetence and power.

Hope Island

On this little voyage of mine, I’ve never felt closer to the explorers than tonight, moored here after a strong wind blew me too close to shore on a minus-two tide. My depth finder showed that I had very little water beneath my keel. For hours, I did what I could to readjust my position, predict how low the tide would go, and where Selkie would swing as the wind grew stronger. The waves crashed louder and ever nearer to me on the lee shore. I created a lead line, just like the explorers used to measure the water below their vessels, so that I could check the accuracy of my depth finder. As I pulled the lead line in and considered my narrowing options, the wind and the tide turned, and now, all is well.

Strait of Juan de Fuca

We crossed today on a 25-mile sail in good winds. Entering Rosario Strait was exciting as we had a consistent and

strong blow against an ebb tide. We passed Watmough Bay on Lopez Island,

where, on June 10, 1792, a Spanish expedition set up a telescope and observed the transit of one of Jupiter’s moons to

aid them in locating their latitude. That day was much warmer than the 40 degrees we had just experienced on this crossing. The following day, the men complained of the heat—98 degrees. I am thrilled by the expedition’s descriptions of tacks, wind direction, and observations of the original inhabitants. We will follow their course home to Bellingham through the Guemes Channel tomorrow. To an observer, I’ll be standing in the cockpit dealing with lines and such, chatting amiably with my companion, but inside, I’ll be in reverie, imagining a different time, as the Spanish, so far from home, traded with The People who came by canoe to their ship—dried clams strung on cedar bark in exchange for metal buttons—and by day’s end go aground while anchored in Bellingham Bay.

Salt Spring Island

We came across a midden yesterday. It is likely the result of 3000 years of

Selkie

clam bakes and clam processing on a wide beach facing the south, made up of stacks of shells in a low bluff above the beach. That’s about 100 generations of The People. I sketched it today while my companion read aloud from a charmingly outdated post-war sea novel as the wind howled outside. I drank a cup of broth and enjoyed being dry and warm inside the boat while I let my imagination run wild. I would have liked to have known these early residents of the beaches, the first of whom emerged from a clamshell into the world, in the Haida telling.

Stuart Island

I want to say a few encouraging words about reading aloud to one another. Nights are long, and the weather often demands we stay in. Streaming video and social media are always right there to fill the time, but they are thin compared to reading aloud with your people. It brings you together into a warm, entertaining embrace that feeds you food you forgot you needed. It’s not unlike telling stories around the fire. People can draw, knit, play with Legos, and do all manner of things while someone reads. I can hear my mother’s voice reading countless books to me. It’s in my bones. My son and daughter know my voice in this way,

too. It’s a memory that stitches us together as we share the power of story. It is easy to forget this powerful, primary way of circling up and being close. If it’s been a while, consider giving it a try on these dark, cold evenings. You might, like me, re-discover something we lost along the way.

Rosario Strait

The Irish blessing, ‘May the wind be always at your back,’ was made true over the last few days. Riding the current north throughout the morning and

early afternoon has been welcome as we head closer to home. Winter rains have added to the transcendent brooding grey-shaded wash we’ve been taking and make the warmth of food, drink, and heat in Selkie’s cabin all the sweeter afterward. We seek comfort, and understandably so, but enjoying those comforts too much and too often may well be more dangerous than a winter passage across cold, rough waters. I’m going to miss the excitement. ANW

Skagit County Historical Museum Presents: Wick Peth: “The Original Rodeo Bullfighter” and the History of Rodeo in Skagit County

Photo by Jerry Gustafson

At the Water’s Edge

A Year Beside Todd Creek

Poems by Nancy Canyon. Paintings by Ron Pattern

In my year-long tenure as a Writing the Land poet, I penned several poems about Todd Creek, the Whatcom Land Trust parcel I adopted. The Whatcom Conservation District is partnering with the Whatcom Land Trust to restore 22.4 acres of riparian habitat along this beautiful creek in the South Fork Valley of the Nooksack River in Whatcom County.

At the end of my tenure, Writing the Land: Channel, a book of land poets was published by NatureCulture.

Todd Creek at Forty-eight Degrees

I

The sound of the Nooksack is steady, rapids tossing & rolling, river rerouted around a tangle of uprooted alders. After the flood, fast water & forest debris blocked the road for days. Today is the day we first see the damage. Sticky mud coats the ground a hundred feet inland. Above Todd Creek, a mature maple rests on its side, its huge root ball lurching upward. Below the bank, the creek passes a logjam the size of a mill yard. At the confluence with the Nooksack, a revised spit curves into the river.

II

This morning we packed a thermos of tea, two sandwiches, two apples & chocolate, …always chocolate! Now we sit on the rocky beach eating lunch, taking in the eroded bank across the river. We estimate 30 feet of pasture washed away in the torrent. The Nooksack calmly eddies & swirls past the bank, whirlpooling back to take another swipe at the undercut. Small trees & large rocks create an island that twists up from beneath, splitting the river around the riprap. North of Bellingham, floodwaters forced evacuations. I’ve heard that the smell of a river & the fine silt deposited by floodwaters is almost impossible to clean away.

A sudden squall has us scrambling from beach to woods, laughing, slipping in the silty mud, coming to rest beneath tall maples. Heads tipped upward, we squint against raindrops splatting green leaves bright as spring grass.

III

Then there are the nutrients: minerals in the silt fertilize the land.

The grass at Todd Creek is waist-high now, like prairie grass before the dustbowl.

The sky is a deep blue-black, rain falling, the two of us tucked like cattle beneath the maples.

Finished with our lunch, R pulls up his hood & slips back onto the path.

I return my notebook to my backpack & fasten the closure, wend my way through wet grass

to follow the arc of cornfield. Overhead, seven turkey vultures lift on thermals. I imagine they’re

waiting for our insignificant lives to end. Beyond the scavengers the sky lightens, clouds begin to drift east. All around, a calm-quiet contrasts with the imagined roar of raging waters. We walk past the plowed field, heading back to the truck where we’ll scrape mud from our boots before climbing in.

despite the flood damage, the land is lush from silt: a sea of grass, saplings shooting skyward, blackberries thriving.

IV Todd Creek—

Devil’s Club

Nooksack Winter

In the Water

Tree hormones flow through our blood bioidentical cells shared with cedars joined together by the river’s flood

Mother tree towers as family leader

Bioidentical cells shared with cedars blend our lives with the trees

Mother tree towers as family leader we bow down on our knees

Writing the Land

Writing the Land is a collaborative outreach and fundraising project for land protection organizations, partnering with nonprofit and environmental organizations to coordinate the “adoption” of conserved lands for poets. Each poet is paired with a specific site, usually for about a year, and they visit the location to create work inspired by a sense of place. This project emphasizes the importance of individual connection to land and place—inspiring others to visit or donate toward protecting these conserved lands of all types, including conservation easements, ranches, farms, ecosystems, habitats, sanctuaries, and wilderness preserves.

More info: www.writingtheland.org/

New Book by Nancy Canyon

Nancy Canyon’s new memoir, STRUCK: A Season on a Fire Lookout, about her time spent as a fire lookout in the Clearwater National Forest of Idaho was published in September.

Learn more at nancycanyon.com/books

Blend our lives with the trees mixing our chemistry together we bow down on our knees forest of siblings tethered

Mixing our chemistry together hormones shared with the beloved forest of siblings tethered tree hormones flow through our blood

Log Jam

Cycology

by Paul Tolme

Dampening Expectations

It’s best to enter winter with a plan, lest the wet weather dampen your enthusiasm for biking. My winter plan is to set a goal, to be prepared, and to be opportunistic.

My perennial goal is to ride the annual Chilly Hilly on Bainbridge Island. Organized by Cascade Bicycle Club, Chilly Hilly is the annual kickoff to Washington’s bicycling season. Mark your calendars for Feb. 23, 2025 and get motivated to join the thousands of people who have completed this historic bucket-list excursion.

But riding in winter requires more than motivation; it also requires preparation.

Preparation means having the right waterproof gear and bike setup for foul conditions. For me, comfortable winter cycling is about two things: fingers and toes. Keep your hands and feet warm and dry, and you can bike through the coldest and soggiest of Pacific Northwest winters.

In addition to a rain jacket and rain pants, here are a few items from my gear stash that keep me pedaling when the weather turns cold, damp, and dark.

• Waterproof Socks. I recently got a pair of Cross Point socks from Portland’s Showers Pass, a great PNW brand. They have a waterproof membrane sandwiched between two layers of soft material that keeps cold water away from your feet.

• Rain Booties are like galoshes for biking. I have two pairs: a set of snug rubberized Endura Luminate overshoes that slip over my click-in road biking shoes and a pair of zip-on Club Waterproof Shoe Covers from Showers Pass to wear over my sneakers or casual shoes when commuting to the office.

• Fenders are crucial in winter, and they come in many types. Some are easily installed and removed, such as the Raceblades from SKS that mount with quick-release straps. Others can

be permanently mounted with hardware, such as the Full Metal fenders from Portland Design Works that I keep on my winter commuter.

• Bar Mitts: These voluminous neoprene mittens attach to your handlebars like a big, comfy oven mitt. I wear a thin glove underneath when it’s frigid or go barehanded inside when it’s just chilly.

• Bike Lights won’t keep you warm but will keep you safer. There are two basic types— lights for seeing and for being seen. I recently acquired a 700-lumen rechargeable City Rover headlight from Portland Design Works to light up the road in front of me. For visibility by drivers behind me, I attach a red USB taillight.

My final tip: be opportunistic. When the clouds break, get out there. Dark winters can dampen my mood. That’s why I make daily outdoor activity— whether bicycling, skiing, or just suiting up and walking in the rain—an intentional practice because there is no greater gift to give oneself than the resolution to move through winter with joy and reverence for the natural world.

Stillness

There is a level of hustle and bustle in the world that is hard to avoid. To be a part of “what’s happening,” socially or professionally, means engaging in often frenetic activity where everyone seemingly goes a mile a minute. I’m as guilty as anyone in perpetuating this behavior. I’ve been known to stare at the screen on my cell phone while also staring at the screen in a self-checkout line.

I engage in this hyperactive world for the same reasons other people do. It’s natural to be social. We are a social species that has designed a world where it is easy to surround ourselves with each other. This design offers great benefits in the form of convenience and access that would be tough to give up. However, sometimes I wish I could make it all disappear. I’m a naturally ‘hyper’ person, so as the world around me gets wound up, my energy follows. This is great… until it isn’t. At some point, it turns to stress as my cortisol levels rise. The masses of people and constant stimulation become too much, giving rise to a feeling of being trapped, a feeling that I must escape. So escape I do.

Story and Photos by Tony Moceri

go to these places to relax my mind and lower my blood pressure. I enjoy going on runs under a canopy of trees and taking long paddles through crisp waters.

But most of all, I enjoy wandering the woods behind my house. With my

I retreat to nature, the place our species is truly designed to be a part of. To be social with animals other than humans. To be in the shadow of a mountain on a sunny day or duck under a protective tree when raindrops fall; to sit quietly on the shore of a river or in a boat in the center of a lake. I

dog in tow, we walk with no agenda. She sniffs, I gaze, and then sometimes we switch. When walking quickly, the area can seem small, but when slowing down to zoom in on the details, worlds upon worlds appear. A vine maple snaking through the woods with moss clinging to its bark. Bright green ferns sprout out of a rich bed of moss— their web of roots taste like licorice. These beds of moss are entire worlds for insects. Birds use the branches as spring-