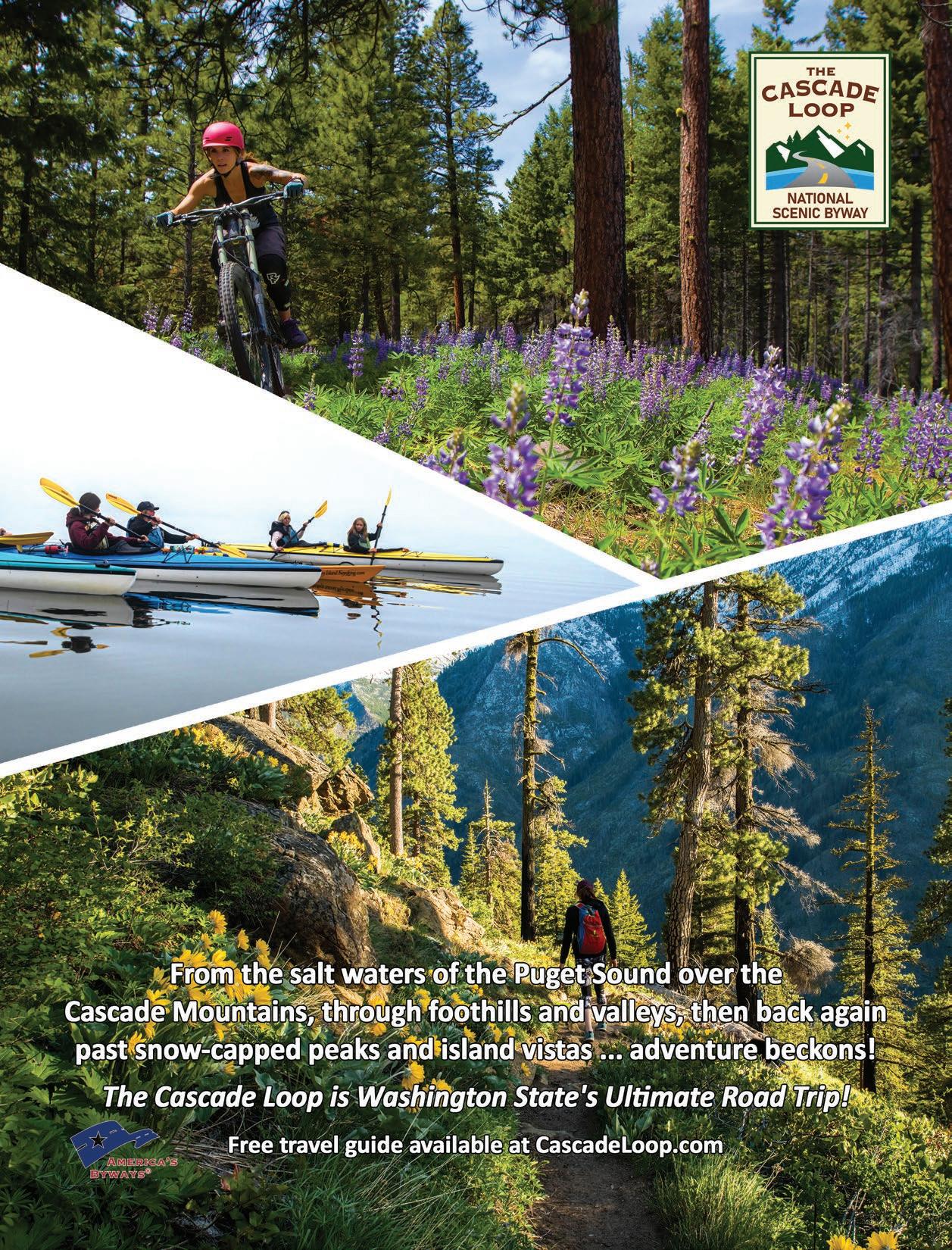

ADVENTURES

Spring in the San Juan Islands

Inspired by Nature

PeaceHealth Medical Group

Orthopedics & Sports Medicine experts specialize in surgical and non-surgical treatments for shoulder, hand, hip, knee, foot and ankle pain and injuries. Call for more information or to schedule a consultation.

Bellingham 360-733-2092

Friday Harbor 360-378-2141

Lynden 360-733-2092

Sedro-Woolley 360-856-8820

peacehealth.org/services/ orthopedics-and-sports-medicine

Rollover your old 401(k) or retirement plan assets into a Saturna Trust IRA.

It’s easier than you think. We can help.

• Take control of your retirement assets

• Sustainable investment options

• Most rollovers are tax-free

• No account or transfer fees

• Flexible beneficiary assignment

To learn more about how Saturna can help rollover your retirement assets, visit www.saturna.com/rollover

Investing involves risk, including the risk that you could lose money.

While there are no account or transfer fees for IRA accounts invested in Saturna’s affiliated mutual funds, ongoing investments in mutual funds are subject to expenses. See a fund’s prospectus for further details. Trades in a brokerage account are subject to a commission schedule. Wire transfers out of the account and expedited shipping of proceed checks may incur fees when these services are used.

IRA distributions before age 59½ may be subject to a 10% penalty. IRA distributions may be taxable. Rollovers are not right for everyone and other options may be available. Some retirement plans allow you to hold your assets in the account until you need them. You should check with your previous plan administrator about any fees they may charge. It is important to carefully consider your available options, including any fees you might incur, before choosing an IRA rollover.

Brokerage products are offered through Saturna Brokerage Services, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Saturna Capital Corporation and member FINRA/SIPC. Saturna Trust Company is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Saturna Capital.

Years.

Since 1967 LFS Marine & Outdoor has served the Pacific Northwest community from its flagship store on Squalicum Harbor in Bellingham. The secret to our 50+ year success story has been dependable service that our customers have relied on through the most challenging times. We understand that our customers count on us to help them navigate a successful boating and outdoor experience. That is why we’re here for you, and that is why we’re here to stay.

“I wondered how to love this world, with its wildness slipping away, and was told to love it in great, good sadness. And how to turn the tide? If not by persuasion then guile, if not guile, then force, if not force then poem, prayer, and song.”

“They have so much stuff!! Its a great place for any outdoors person or even DIY people. They have good prices too.” - Google Review

Carson Artac is a Bellingham, WA-based commercial and editorial photographer. When not behind the camera, he’s often mountain biking, fly fishing, or surfing. Much of the inspiration for his work comes from those magical moments of flow while pursuing these practices.

Ken Campbell is the Director of the Ikkatsu Project and author of several paddling books, including Around the Rock; A Newfoundland Sea Kayak Journey, and A Sea Kayaker’s Guide to the San Juan Islands. For more information on marine debris, expedition reports, and news about upcoming programs, visit www.ikkatsuproject.org

Abram Dickerson is the owner/ principal at Aspire Adventure Running. As a husband, father, and entrepreneur, he attempts to live his life with intention and purpose. He loves mountains and the friendships that result from the suffering and satisfaction of running, skiing, and climbing in wild places.

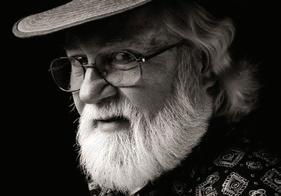

Lance Ekhart philosophizes aboard his sailboat Elenoa, surrounded by the fluttering birds of Flounder Bay. He searches for the meaning of life through his nature photography and building boat things in his shop. Visit him at www.lanceekhart.zenfolio. com

Painter Caryn Friedlander lives and works in Bellingham, WA. Represented by ArtXchange Gallery in Seattle, her work resides in multiple private and public collections, including Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Vulcan Foundation, and Washington State University. See her work at www.carynfriedlander.com and at www.artxchange.org.

Don Geyer has spent most of his life in the Pacific Northwest. He’s photographed the western U.S. and Canada for over 30 years and is the author of Mount Rainier, a photography book. View his work at www.dongeyer. smugmug.com.

Mark Harfenist was born and raised in New York. After 40 years in places with insufficient snowfall, he settled at last in Bellingham, WA, where he dabbles in mountain biking, motorcycling, backcountry skiing, kayaking, and world travel. In his spare time, he works as a family therapist and mental health counselor.

Bill Hoke came to the Pacific Northwest in 1970 and began a lifetime of climbing and hiking. He’s hiked— primarily solo—more than 1,500 miles in the Olympic Mountains and is the editor of the fourth edition of the Olympic Mountains Trail Guide

Alan Majchrowicz is a landscape and nature photographer living with his family in Bellingham, WA. His images have been used in advertising campaigns, product design, tourism brochures, books, magazines, and calendars. Learn more at alanmajchrowicz.com.

Lawrence Millman is the author of 20 books, including such titles as Last Places, Our Like Will Not Be There Again, Lost in the Arctic, At the End of the World, Fungipedia, and — most recently — The Last Speaker of Bear: My Encounters in the North. He keeps a post office box in Cambridge, MA.

Jess Newley is the Community Science and Education Manager for Friends of the San Juans. She has proudly called the San Juan Islands home since 2018. Originally from Selah, WA, Jess is a passionate SCUBA diver, underwater photographer, and sailor.

Ted Rosen was a longtime Greenways Advisory Committee chairman and remains a steadfast defender of green spaces, both large and small. When he isn’t working his day job, he can be seen on local trails pointing out invasive species and complaining about litter.

Robert Sund (1929-2001) is the author of Poems from Ish River Country, Collected Poetry and Translations, Taos Mountain, and Notes from Disappearing Lake. His recently published chapbook, First Glimpse of Swallows, is available from Brooding Heron Press, P.O. Box 29, Waldron, WA 98297. www.robertsund.org.

Jimmy Watts lives in Bellingham, WA, with his wife, their two sons, and a golden retriever. An awardwinning writer, his work has appeared in American Flyfisher, the Drake, and Orion magazine, among others. He is also the craftsman behind Shuksan Rod Company’s split cane bamboo fly rods, and for the past 22 years, has been a professional firefighter in downtown Seattle.

“A walk amongst nature, whether by the sea, river, hill, valley, meadow or wood, works wonders for the human spirit.”

- unattributable

Theact of venturing into the wild offers a litany of rewards; the physical (and psychological) stimulation of exercise, the freedom that comes from shedding our regular routines, and a refreshing sense of exploring unfamiliar terrain.

But perhaps the greatest gift that the wilderness offers us is inspiration. A different and possibly more grounded perspective, an opportunity to re-frame priorities. This resonance reverberates throughout our lives, simultaneously energizing and calming; at minimum, a coping mechanism and, at most, a path to self-discovery.

In this issue, we highlight this hard-to-define quality, as exemplified by David James Duncan, Lawrence Millman, and Doug Peacock (‘Hayduke’ to the Edward Abbey fans in the audience), three writers whose life work has been to inspire readers.

Springtime in Cascadia is also inspiring. Trillium blooms in the shadows of the forest, and the days grow longer, rewarding our winter-worn perseverance. After the long season of grey days and long nights, we can all benefit from some forest bathing or a few hours spent afloat among the emerald-green islands that comprise the San Juan archipelago on the Salish Sea.

Thankfully, the San Juans are easily accessible. What a joy to spend a spring day among these alluring islands! This remarkable archipelago offers sailing, hiking, camping, mountain biking, trail running—a thousand ways to connect to the source. In this issue, we highlight these magical islands that occupy the western horizon—so close, yet a place apart. We’ll dive deep, exploring the shimmering eelgrass beneath the surface of the Salish Sea, and climb high on the cliffs surrounding Lopez Island’s Watmough Bay. Our featured photographer in this issue, Lance Ekhart, knows the San Juans better than most. His evocative images capture the intimate details that make this marine paradise a treat for the senses. Did someone mention ‘inspiration’?

When Jazmen Yoder found herself working with Aimee Wright as a field botanist for the Botanical Survey and Monitor Project at Western Washington University (WWU) in 2019, they formed an immediate bond. Both enjoyed a deep passion for ethnobotany and Pacific Northwest plants and both loved camping and spending quality time in the great outdoors. Jazmen had studied ethnobotany, mycology, and Salish Sea ecology at WWU and Whatcom Community College. She also had a long history of practicing survival skills. Aimee’s background was in Environmental Science and Terrestrial Ecology, plus she was an artist and musician. The two became inseparable friends.

“While Aimee knew all the wetland plants, I knew all the trees,” Jazmen remembers. “We could call all the flowers by name and were skilled in taxonomy and using dichotomous keys. Our attention to detail and love for the outdoors were shared passions.”

They both served on the board of the Washington Native Plant Society and enjoyed studying plants and collaborating on outdoor adventures. Then, in 2020, COVID hit, and the Pinedrop Sisters, as they now called themselves—the name is derived from woodland pinedrops (Pterospora andromedea), a member of the Indianpipe family—couldn’t get together anymore. “We were both getting depressed,” Jazmen says. “We needed to do something that used our degrees to make us feel like we weren’t wasting all the time, money, and knowledge we had garnered.”

They decided to start Northwest Natura to share their knowledge and love for botany, bushcraft, wildcrafting, herbal medicine, mushroom foraging, birding, and more. “Aimee and I both wanted to be teachers,” Jazmen explains, “but neither of us wanted to go back to school to work at a university level.”

At first, due to the pandemic, their only outlet was social media, and they started a YouTube channel and opened an Instagram account. Despite the challenges of launching a new venture during the pandemic, Jazmen became convinced that she had found her path. She left her job as an Ecologist & Botanist at an environmental specialist firm and decided to make Northwest Natura a full-time operation.

Now with the pandemic behind them, Northwest Natura has launched guided field trips and nature walks, foraging trips, classes

on wildcrafted plant medicines, bushcraft workshops, mycology classes, and more. In addition, Aimee’s artistic inclinations have given rise to offerings such as basket weaving and foraging plant fibers for paper and bookbinding. Their numerous classes, trips, and workshops are now open to the public. “I want to share everything that I know,” Jazmen says, “in hopes that I can help enrich people’s lives.

“The dream is that people who learn more about nature will stand up against threats posed by industrialization, urban sprawl, deforestation, and together share a passion to protect threatened/ vulnerable species and biodiversity,” she says. “The more people learn about what’s out there; the more people will care about parks, wilderness, climate change, etc. I want people to love this place better. I believe nature is healing, but I also believe that people need more than a day out simply forest bathing. They want to enhance their confidence outdoors, feel strong when they’re alone, and they want to have special skills because it makes them feel special (they are!). Having deep knowledge is a type of currency not everyone can come by without formal education.”

Underscoring this heartfelt belief in the power of connecting to nature as a source of personal strength was Jazmen’s experience growing up. After a difficult childhood, she drifted into drug abuse and, at 19, became addicted to heroin. “I know what it’s like to feel like there’s no place for me in the world, to not feel comfortable in my own skin, and to be so alone, sad, angry, and helpless that the future seems hopeless.

“Truly, it was finding an interest in Native American culture, and particularly a fascination with wolves, that saved me. I became passionate about becoming a wolf biologist. I found my identity through self-reliance skills, which included knowing the traditional uses of plants and making friends with trees, flowers, bumblebees, and wild places that imparted a deep-seated love for life again.

“I believe that the skills Northwest Natura offers are not only going to help the ecology of Cascadia, but its principles can save individuals’ lives as they have for me.”

Learn more at northwestnatura.com

Asure sign of spring, the annual Wings Over Water Northwest Birding Festival returns on March 17-19 to Whatcom County, WA. The festival features birding field trips at Semiahmoo Spit, Birch Bay, and Reifel Bird Sanctuary in Delta, BC; nature walks; wildlife cruises; Audubon Society bird viewing stations; art demonstrations; wildlife presentations; and a Birding Expo. The weekend-long celebration of all things avian has something for every bird lover in the family.

An artist reception scheduled for March 17 at 5 pm at the Blaine Community Center highlights artist Laurel Mundy. The festival’s keynote presentation features wildlife biologist Mel Waters on March 18 at 5 pm, also at the Blaine Community Center. Waters, known as “The Bird Guy,” is a wildlife biologist for Puget Sound Energy (PSE), where he has championed the company’s nationally recognized Avian Protection Program. Waters will share his lifetime experience protecting birds and developing environmental and wildlife programs at PSE. More info: wingsoverwaterbirdingfestival.com

In springtime, the Baker Lake Trail provides a rare opportunity to savor lowland solitude in a wild and peaceful setting, a chance for an in-depth visit to the silent forests that line the east side of ninemile-long Baker Lake. You can hike the entire length of the trail (14 miles point-to-point) or sample the considerable charms of the topography from either end on short and rewarding day hikes. The forest is a vivid green, and although the lake is out of sight most of the way, various side trails afford access to the lakeshore and views of Mt. Baker and Mt. Shuksan. There are numerous campsites along the way, should you want to make a night of it.

Trailheads: (North) Drive to the end of Baker Lake Rd, 26 miles from WA-20. Hike .6 miles up the Baker River Trail to a suspension bridge and the beginning of the Baker Lake Trail. (South) From Baker Lake Rd., turn right on Baker Dam Rd. After crossing the dam, turn left on FS-1107. The south trailhead is 1 mile from the junction. A Northwest Forest Pass is required.

The Columbia Gorge is famous for its waterfalls and wildly scenic trails. The short (1.9mile) round-trip to Wahclella Falls hits both of these marks in a big way. Waterfalls are plentiful—including the twotiered showstopper at the end. Although signs of the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire are visible along the way, the journey is supremely scenic. From the trailhead, the route follows an access road to a fish ladder, where a bridge passes beside (and almost through Munra Falls. Exhilarating! From here to the endpoint at Wahclella Falls, the trail is narrow – keep an eye on the kids. Along the way, enjoy the music of falling water, the vibrant green of lush moss gardens, and the sculpture gardens of immense boulders that fill the amphitheater at trail’s end.

Trailhead: On I-84 in the Columbia Gorge, take exit 40 (Bonneville Dam). The well-signed trailhead is on the south side of the Highway. Northwest Forest Pass required.

The Olympic Coast is a jewel in the crown of our national public lands. Part of Olympic National Park, this coastal wilderness offers a chance to dance on the continent’s edge and breathe the cleansing winds that blow in from the vast Pacific. The trail to Cape Alava begins at Lake Ozette (a fine—if sometimes soggy—campground here) and traverses a puncheon boardwalk through a luscious rainforest for 6.2 miles to the beach and campsites among the trees above the sand. From here, you can go north to the Ozette River or south to Sand Point. On a warm, sunny spring day (hey, you might get lucky!), it’s nirvana.

Trailhead: Lake Ozette Ranger Station, at the end of the Ozette Road, 21 miles from WA-112, 32 miles south of US-101. Olympic National Park Pass Required.

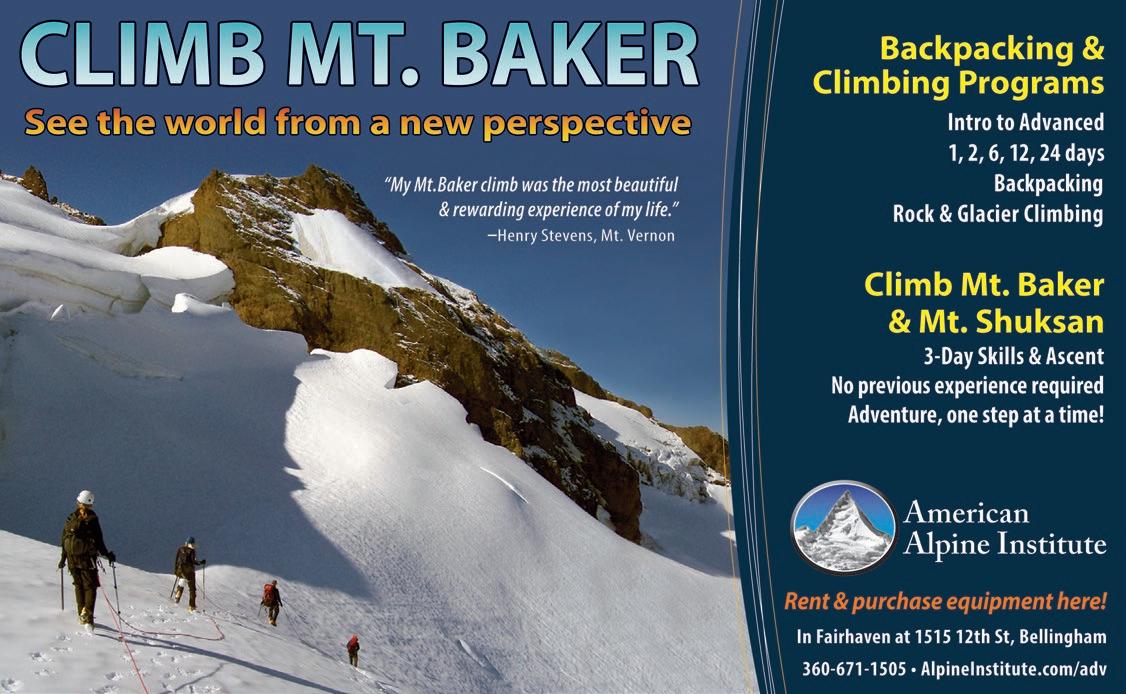

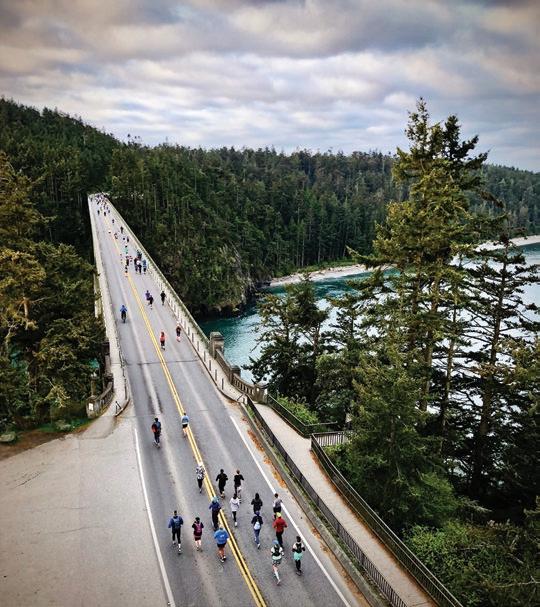

Get out the candles—Ski to Sea celebrates its 50th birthday this year on May 28, and the celebration promises to be one for the ages.

Inspired by the original Mt. Baker Marathon (1911-13), this epic 7-leg relay (cross-country skiing, downhill ski/snowboarding, running, road biking, cyclocross biking, and sea kayaking) spans 93 miles, from Mt. Baker to the Salish Sea. It is hard to overestimate Ski to Sea’s importance to the community. The two-year pandemic shutdown (in ’20 and ’21) gave a new perspective on how the race (and the many associated events) is seamlessly woven into the fabric of Cascadian life, and its return last year was cause for widespread celebration.

The driving force behind Ski to Sea is Race Director Anna Rankin of Whatcom Events. We sat down with her to learn more about this 50th Anniversary milestone for the iconic event.

To celebrate 50 years of racing, I am trying to get an entire team or at least one racer to represent each of our 50 states (and DC). We are also making a Legacy video with archival footage that I am really excited about. I have another idea up my sleeve but should wait to share until plans are solidified. What’s

I expect the Cyclocross course will continue to change,

and we hope to add a beer garden at Hovander Park in Ferndale! And LOTS of merch will be for sale this year to commemorate 50 years.

How has Ski to Sea changed over the years?

Looking at old photos, videos, and race guides has been such a kick and downright emotional. I feel honored to be at the helm of such an important event in our community. One that has only been shut down twice due to the pandemic. Did you know the original letter of recommendation to the Chamber suggested nine events: skiing, mountaineering, canoeing, kayaking, horseback riding, water skiing, running, fishing boat, and sailboating? Over the course of 50 years, all but four (mountaineering, horseback riding, fishing boat, waterskiing) of these events have been used, and only one not recommended (bicycling) has been added.

After a pandemic-caused hiatus, The Junior Ski to Sea Race is back. What will that look like this year?

We are so excited to bring the Junior Race back to the community after a three-year hiatus, and we have made major changes to the race so that it mirrors the big race and earns its name

of Junior Ski to Sea. There will be four legs (skiing, running, mountain biking, and kayaking) starting at the Mt. Baker Ski Area, with a virtual handoff to Lake Padden for the remaining legs. Our Board of Directors quickly realized that we have a large community of kids who are up for the challenge and currently practice and/or excel at these sports. The Junior Race registration just opened. The event is Saturday, May 13th, two weeks before Ski to Sea. It is going to be a crazy May, but we’re up for it.

What did Whatcom Events do to keep this iconic event alive during the pandemic when Ski to Sea

Oh man, it was so hard for me to shut down the race that first year and not much easier in 2021. I received so many comments from racers with personal stories that were so touching that my keyboard was flooded with tears on more than one occasion.

A few teams did their own version of Ski to Sea remotely,

and I thought that was very cool. I tried to keep in touch with the community via social media and a few pop-ups, but it just wasn’t the same. In 2021, I was able to host our three other events (The Tour de Whatcom, Mt. Baker Hill Climb, and Trails to Taps Relay), keeping me busy and connected.

Can you tell us about the effort to have racers from all 50 states compete this year?

I started by reaching out to out-of-state racers that have joined us in the past and got the first eight teams that way. Now we are working with our national partners and sponsors to help us spread the word. I quickly realized that getting a whole team from every state was a bit unrealistic (something I should have started on last year if I had had the time). So now we hope to have at least one racer from each state; currently, over half the states are represented. If people want to find out if their state still needs to be represented, they should contact us, as it comes with a discounted entry!

I think Ski to Sea touches nearly everyone in town and has for five decades. People race or volunteer or sponsor or simply show up to cheer people on. So many fun events are happening in tandem: the Fairhaven Festival, the Block Party at Boundary Bay Friday night, library book sales, etc. I can’t help but feel that Ski to Sea unites the entire community. I love that week when you start seeing all the cars with boats, bikes, and skis on them, and it hits me that it is GO time. Last year was truly magical because people really missed the event during the hiatus. I felt celebration in the air. As the Race Director, the day came with many challenges. I missed that special moment to stop, and look around, to let it sink in that my efforts, and those of my staff of two and race committee of 25, had led to that glorious day. So that is my goal this year, to have a moment where I truly let that sink in. I’ll also probably cry tears of joy.

This Steller sea lion is just one of the unique wildlife encounters that you can enjoy while visiting the islands. Keep an eye out for large colonies hauled out on rocks and an ear out for their roars often heard throughout the night.Photo by Jess Newley

Story by Jess Newley

Story by Jess Newley

Breaching killer whales, soaring eagles, and sea lions hauled out on rocks along stunning shorelines—these are just a few of the sights that people travel to the San Juan Islands every year by foot, boat, or plane to behold. Of course, if you’ve been to the islands before, then you know their moniker as “the hidden gem of Washington State ” is true. But did you know that under the water, there is a whole system of

wondrous natural resources (eelgrass, kelp, forage fish, juvenile salmon, and of course, killer whales (Orcinus orca), to name a few) that support what we get to experience above the surface?

Residents and visitors alike play an important role in stewarding the marine habitats of the Salish Sea. Read on to learn more about a few vital habitats and species of this region and how you can help support and maintain them.

Eelgrass is a flowing plant that grows in shallow, light-filled marine waters, forming large meadows of underwater vegetation that support aquatic food webs. It is easy to see eelgrass at low tide, especially in the spring and summer when it thrives. However, eelgrass abundance varies seasonally, with some winter die-offs. The long blades of eelgrass are an underwater nursery for incubating eggs, such as herring, and provide food and refuge for a wide array of small creatures and young animals, including Dungeness crab, juvenile flatfish, and salmon. Eelgrass beds are also important feeding areas for birds. In addition, eelgrass mitigates wave energy and traps sediments, safeguarding shorelines from wave-driven erosion.

If you are a boater, you can help protect eelgrass beds by anchoring in water deeper than 30 feet. While each anchor might create just a small scar, the cumulative effects can be dramatic enough to be seen in satellite images from space! To avoid damaging

grass, use a public marina or mooring buoy. When those options are unavailable, anchor deeper than 15 feet at low tide in bays and in more than 30 feet of water in more open areas. You can explore an eelgrass depth map at sanjuans. org/greenboating and see for yourself where eelgrass is growing around the islands. Lastly, avoid chemicals when cleaning your boat, and if you live near the shoreline, limit the use of lawn and garden chemicals.

Known as “the rainforest of the sea”, kelp beds are another vital habitat found around the islands. Bull kelp, growing up to a foot a day in subtidal waters, sometimes at depths of over 60 feet, is one of the fastest-growing organisms on earth. Clusters of bull kelp can be seen offshore of almost any high-energy rocky coastline in the San Juans. Also, numerous species of understory kelps grow along rocky bottoms, providing additional habitat complexity to the kelp forest. Kelp provides shelter to sea urchins,

otters, seals, crabs, juvenile rockfish and salmon, anemones, starfish, sea cucumbers, octopuses, and many other marine creatures. Kelp needs clean water and light to thrive because, unfortunately, it is very sensitive to pollution from small and large oil spills, soil erosion, and yard chemicals.

If you live near the shoreline and have a septic system, you can help by ensuring your septic system is working correctly and reducing your use of chemicals. If you are a boater, keep your boat in good condition, and clean even minor fuel spills using absorbent pads—not soap! Never soap! And, of course, for your safety and to protect the kelp, always steer clear of kelp beds when underway.

Small schooling forage fish, or bait fish, are essential staples in the diets of fish, seabirds, and marine mammals, including Chinook and coho salmon, lingcod, marbled murrelets, rhinoceros auklets, and minke whales. Primary

species in the Salish Sea are pacific herring, pacific sand lance, and surf smelt. Each forage fish plays an essential role in marine food webs by transferring energy from plankton to larger species. Forage fish do not spawn just anywhere. Pacific herring deposit transparent, adhesive eggs on eelgrass and marine algae close to shore. Surf smelt and pacific sand lance incubate their eggs on beach sand and small gravel near the high tide line. These spawning forage fish utilize the same shoreline areas where humans concentrate activities, making them vulnerable to shoreline alterations such as armoring or bulkheads, docks, roads, and vegetation removal. You can help forage fish by keeping beaches natural with plenty of overhanging native trees and shrubs. Large driftwood is also beneficial as it helps to maintain cool, moist conditions for the tiny eggs.

It’s hard to visit or live in Washington State without hearing

about salmon. These fish are the lifeline to indigenous cultures, economic stability, ecosystem functionality, and much more. But did you know that the San Juans are a critical rearing habitat for juvenile salmon? Each spring and summer, young salmon, just inches long, migrate from their natal rivers along the shores of the Salish Sea into the productive shoreline habitats of the islands. Researchers have found that the time juvenile salmon spend nearshore, eating and growing as fast as possible, is critical to their survival as adults.

Marine mammals such as southern resident killer whales depend on adult salmon for food as these anadromous fish pass through the San Juans on their way to spawn in their natal rivers. Salmon are also culturally vital to indigenous tribes in

the Pacific Northwest.

To help salmon, avoid single-use plastics that often make their way into rivers and marine waters. If you are a waterfront property owner, there is much you can do to support salmon populations. Did you know that juvenile salmon eat insects that fall into the water

from shoreline vegetation? By keeping your beach free of shoreline modifications and retaining overhanging vegetation, detritus, and driftwood, you will support the insects and forage fish that young salmon eat. Also, juvenile salmon tend to avoid swimming under docks and instead move out into the deeper waters, where they are at risk from predators. To reduce demand for new docks, consider using a marina, mooring buoy, or sharing an existing dock with neighbors. If you already have a dock, look into improvements such as grating that can increase light penetration.

We have two killer whale populations swimming through Salish Sea waters and the San Juan Islands. The most well-known are the southern resident killer whales, an endangered species that used to regularly spend their summers in the region but

are visiting the islands less. Southern residents depend primarily on a diet of Chinook salmon, a threatened species that are increasingly harder for the orcas to find. Southern Residents need space and quiet waters to find this limited food.

We also have transient killer whales (a.k.a. Bigg’s killer whales), who are currently thriving in the Salish Sea, where their primary food sources—harbor porpoises, seals, and sea lions—are plentiful.

Luckily there are many places in the San Juans to view these extraordinary species from shore. Consider joining the regional Give Them Space movement to avoid watching the endangered Southern Residents from vessels. Instead, focus on the exciting Bigg’s whales or view the whales from shore at Lime Kiln State Park on San Juan Island. If you end up boating near the Southern Residents, stay at least 400 yards away. Visit BeWhaleWise.org for more information and viewing guidelines.

Salmon, eelgrass, bull kelp, forage fish, and orcas—all of these wondrous things are connected in ways that we don’t always see or experience as humans living above the surface of the Salish Sea. If we lose one of these critical pieces of the puzzle, the Salish Sea and all who rely upon it will suffer. Therefore, it is increasingly vital that we all do our part to take care of this special place and do what we can to protect it for people and nature.

Next time you look out the ferry window, off the aft of a boat, or gaze from a plane as you fly over, take a moment and go deeper. Remember that this amazing and complex web of life outside our usual view depends on all of us to steward and protect it.

Evolutionarily, our unique bipedal movement served as transportation and survival. Our legs got us places. If our endurance and primitive tools bested our prey, we ate. If we ran faster than what or who was chasing us, we survived.

Fast forward 70,000 years from the Paleolithic period, and the once critical evolutionary adaptations our bodies made for movement have been supplanted by new technologies. Today I can sit at my computer and order food, do “work,” pay my mortgage, and communicate across time and space, all by dancing my fingers across a keyboard. Running has been relegated to the realm of leisure or loathing.

There are some, possibly eccentric or potentially unassuming characters for whom echoes of an ancient running practice still resonate. For these runners, a commitment to movement is more than sport and more than an effort to improve one’s corporeal presentation. For these humans running is a ritual that increases our mental and physical capacity to do difficult things. Thus, the very act of running is a protest against an alltoo-common inclination toward doing what is easy. By choosing movement, we rage against complacency, embrace suffering,

and unlock wisdom reserved for those willing to transgress the norms of ease and comfort. It’s as if the very process of choosing movement unlocks a fundamental connection to a deep and powerful psyche forged in our earliest evolutionary consciousness.

In practice, every run begins in the mind—our bodies follow. The legs begin to churn; the arms swing. In motion, the body presents the mind with a dialogue of fatigue, joy, pain, sweat, and breath. The mind receives these messages and determines how to respond. Continue? Walk? Sprint? Crawl? Stop? In movement, this chorus of physical sensations is the lived experience of a mind-body connection. Over miles and time— hours, days, and years—the timbre of these sensations change. The body adapts. The mind learns when to push and when to rest. An understanding and acceptance of individual strengths and weaknesses develops and informs choices of how to care for the body and mind in a holistic and graceful way. This running as a ritual creates space for a moving meditation. Ultimately, it is a means for furthering our connection to self, place, and others. Each run provides an opportunity to escape external expectations and simply move. Each run invites the runner to be fully present and aware. Each run is a testament to our power and capacity to be agents of change and creation. While none of this directly translates to our survival, each run is an act of living. Welcome to the tribe.

TheSan Juan Islands are world famous, attracting all manner of seafarers who enjoy exploring this luscious archipelago in everything from yachts to sailboats to kayaks. They are also a playground for hikers, beachcombers, and birdwatchers. Consisting of more than 400 islands (depending on who does the counting), the San Juans have some marquee attractions: Sucia Island with its picture-perfect anchorages and miles of scenic hiking trails; Orcas Island and its magnificent Moran State Park; San Juan Island’s prime orcawatching location at Lime Kiln State Park, the list goes on and on.

Lopez Island is a somewhat more low-key destination. It is home to artists and writers, a quiet place focused more on quality of life than tourism. But Lopez has some beguiling places that offer visitors opportunities to explore lonely beaches, peaceful forests, and sun-dappled headlands. One of these is the small preserve at idyllic Watmough Bay, located on the island’s southeast-

ern shore and reachable by car (thanks to the Washington State Ferry System). Starting at the parking lot, one can

hand Fidalgo Island, as well as distant vistas of Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters Range, especially evocative at dawn and dusk when the peaks are often bathed in rosy light.

Driftwood logs on the beach provide excellent places to lean back and enjoy an al fresco lunch while soaking up the sights, sounds, and scents of the Salish Sea. Across the water, the blue-green colors of the San Juans soothe the soul.

But don’t get too comfortable. A short trail circles the marsh, offering opportunities to savor the peaceful duff-carpeted forest. Birds are plentiful. And a more vigorous 2.9-mile round-trip hike climbs to the top of Chadwick Hill, at 470 feet, the second highest point on Lopez, and part of San Juan Islands National Monument. From the top, views extend out over the Salish Sea to the glittering San Juans and the distant Olympics.

easily stroll through a forest of towering cedars to a cobbled pocket beach beneath a soaring cliff with expansive views across Rosario Strait to close-at-

If you choose to visit by water, there are several (free) mooring buoys and excellent anchorages in the bay. If possible, use the buoys to avoid damaging the underwater eelgrass beds that carpet the bottom of the bay and provide excellent habitat for juvenile Chinook salmon.

Boulder Island, near the southern end of the bay, is a National Wildlife Refuge – boats must not approach within 200 yards.

A short skiff ride brings you to the beach and hiking trails.

Bank, along with a conservation easement to protect the wetlands. The Bureau of Land Management, yielding to pressure from local islanders, purchased more of the waterfront as well as uplands in 1995.

additional shoreline, creating the 400acre area of the existing Watmough Bay Preserve.

Public access to this lovely marine enclave is relatively new. In 1993, the Oles family donated a portion of the beach to the San Juan County Land

In 2007, the San Juan Preservation Trust led an effort to purchase more land along the southern shoreline. In 2009, Imogene ‘Tex” Geiling donated

These paintings refer to a spring-fed lake I hiked around almost weekly throughout the pandemic. Offering everything one could want in a refuge, the lake is quiet, out of the way, and surrounded by verdant, hilly trails flanked by giant nurse logs that nourish already large, mossy trees. I have observed two complete seasonal cycles there, witnessing lilies emerge and disappear into those waters, along with the startling calls of bullfrogs in spring and ducks cutting across the calm surface with their stippling V-shaped trails in the fall.

I needed nature more than ever during those two years. It kept me whole and kept me sane. The certainty of the cycle of life and death that nature mirrors brought me hope and resilience that was hard to find elsewhere. So, with gratitude, I brought nature into the studio as my companion and surrounded myself with its beauty. Learn more at www.carynfriedlander.com

From the Washington State Ferry landing at Lopez Island, drive 2 miles southwest on Ferry Rd. Turn left onto Center Rd. After 5.6 miles, turn left onto Mud Bay Rd. After 4.2 miles, take a right on Alek Bay Rd. In .5 miles, turn left on Watmough Head Rd. Follow this road for approximately 1.5 miles, then turn left at the bottom of a small hill at the Watmough Bay sign. The parking lot (which includes a restroom) is well-signed.

•

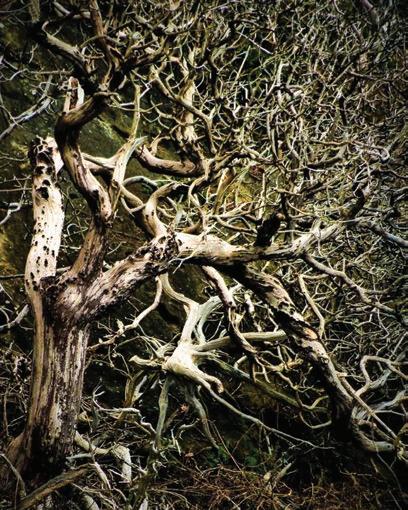

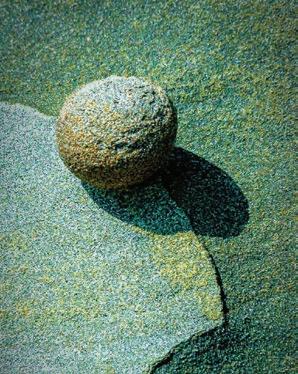

For more than 20 years, I’ve been visiting the secluded “Three Amigos” in the San Juan Islands: Matia, Sucia, and Patos Islands in my sailboat, Elenoa . Each voyage is different: the seasons determine what sections of the fantastical sandstone formations receive glorious lighting, whether Madrone bark is colorful, and whether spring flowers or fall colors dominate. Weather conditions and tides determine access to seaweed formations and other often-hidden shoreline treasures. Storms bring new driftwood to explore, and calm winds create reflections in still waters.

The depth of understanding that has gradually been revealed to me by this decades-long affinity brings me great joy in connecting deeply with this special place and allows me to see deeper into both the grandeur and intimate details that make these islands so remarkable.

See more of Lance Ekhart’s photography at: www.lanceekhart.zenfolio.com. Visit AdventuresNW.com to view an extended gallery of Lance Ekhart’s island photography.

Restore salmon habitat across Whatcom County on Saturday mornings! Our event schedule is regularly updated and open to all ages and abilities; scan below to find an upcoming event near you.

“The whole package was fantastic. Whales...glorious wilder ness areas, glacier s, bear s, rainbows and water falls!”

It’smid-afternoon in Bellingham (WA), and a bonfire burns behind our house—split timber from last winter’s tree fall towered high and bright. An October breeze gently feeds the flames. There’s a break in a week’s worth of rain, and the wind has blown the grass dry, begging us to sit outside.

With me is David James Duncan—the revered author, storied activist, and one of the most profound spiritual and ecological minds of our time. He’s just finished a forthcoming novel, Sun House, a sweeping 1100-page odyssey through the American West portraying what he calls “our biological and spiritually inescapable realities and the love and justice they demand.”

“I tried to stick to a more practical length, but the state of a world in which problems are no longer political, but epic, overwhelming, mythical, left me pining to pen an epic in what the praise poet Anne Porter called “an altogether different language.” I wanted this read to feel like walking El Camino in Spain, or the Pacific Crest Trail, or taking a month-long spiritual retreat in a place far from the nearest asphalt and fumes,” he says. “I’m hoping Sun House

Photos by Carson Artacfound that different language, and it’s my best and most timely work. It’s certainly been the most costly.”

hearth fire to light another. Huddled behind us—as if they too were a fire—are twelve tamaracks raining amber needles like embers into our laps as broadleaf maple leaves the size of dinner plates and the color of the sun drift down around us. It’s cold out and we’re sitting close to the flames, savoring the warmth. Even my retriever reclines toward the heat, his back against the warm firepit stone and mortar walls. Nearby is a small and nearly dry spring-fed creek, a Lost Creek as its actual name predicts; its water diminished by four unprecedented summer months without rain. I’m in a hooded fleece jacket zipped tight to my chin. Duncan wears two long-sleeved, collared shirts and a hand-knitted blue scarf horseshoed around his neck, wearing it like a hug. “My daughter Celia made it,” he says.

How my audience with Duncan came to be is a separate story started around a much earlier fire—or an earlier reverberation of this same fire warming us today; friendships being no different than flames, the way lightning strikes for millennia have been carried from one

“Scattered on the acre behind you,” I tell him, “hidden under the salmonberry and sword fern are five Sequoia starts Ellie (David’s other daughter) gave me a couple of years ago. They may be the only conifers still here a few hundred years from now.”

Holding the ends of Celia’s blue scarf while eyeing Ellie’s Sequoias, David remarks that he loves sitting in the backseat while his daughters choose the

destination and drive. He says he wrote Sun House as a gift to his daughters and all the generations facing the epic and the overwhelming. “Our challenges,” he says, “have moved far beyond the political. The world situation is darkly mythic now. Epic. And requires a collectively mythic and epic response.”

“Nothing having arrived will stay,” I remark, quoting a Wendell Berry poem, “…and yet this nothing is the seed of all—the clear eye of Heaven, where all worlds appear.” It’s a poem I hear resonant within the pages of Sun House. Inside the narrative is a sense that the womb of Earth herself harbors a smoldering warmth that cannot be extinguished, as if a maternal force hidden in the dark nothing, beneath the dirt, is waiting to become known.

“One of the most unusual things about my life,” Duncan continues, “from the time I was twenty, I’ve had many friendships with wise old women and a preference for the feminine expressions of wisdom, ongoing to this day. I drew on the saint Julian of Norwich in The River Why, and visited her home city when I was just seventeen. I draw on Julian again in Sun House, saying ‘just as God is our Father, so God is our Mother.’ Toxic masculinity has driven our engagement with Mother Earth in the wrong direction for centuries. I heed wise women facing the direction of life, not money. As our Muscogee Nation U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo wrote, ‘Remember the earth whose skin you are.’”

to be Gus, his protagonist in The River Why, finished in 1979 when he was just twenty-seven and published in 1983. At the time, Duncan was mowing lawns for

changed their ‘Nonfiction Only’ policy and made The River Why their first novel. Nearly 40 years later, it’s still in print and widely considered a classic.

In 1992 his novel, The Brothers K, was published, an 800-page effort he spent seven years writing, portraying a Vietnam-era American family, broken for the same reason families break today, pieced back together with deep understandings and heroic acts of forgiveness. The Brothers K earned Duncan widespread acclaim and international attention; ever relevant, it remains in print.

a living in Portland, OR, and driving a Dodge Coronet with two smashed quarter panels and a door that wouldn’t open. “But it got me to the Deschutes in two

To say Duncan has been prolific in the three decades since The Brother’s K is an understatement, but much of his work took the form of public speaking and activism. During those decades, he published three collections of essays, including the National Book Award-nominated My Story As Told by Water. In addition, he co-authored two activist-response books— Citizen’s Dissent with Wendell Berry and Heart of the Monster with Rick Bass—while giving some fifty talks in close to as many cities.

About Citizen’s Dissent, cowritten in 2003, Duncan says the book was “in protest of the de facto political party embodied by the so-called ‘Christian-right’ which betrays the words and example of the very Jesus it claims to love…Jesus scorned riches and embraced the poor, blessed peacemakers, not war-makers, celebrated creation, diversity, empathy, and beauty, and insisted that compassion is literally compassionate!”

For the better part of my life, David James Duncan has been a treasured companion, for years now in person, far longer in his body of work. Like every Pacific Northwest river kid Huck Finn wannabe, at age sixteen, I wanted

hours,” he said, “and to my favorite coast streams in an hour forty-five.” Living in a $100 a-month cabin on an urban creek, finger-pecking at a typewriter, and without an agent to his name, every publisher in the country rejected his unsolicited manuscript until the Sierra Club Books

In 2010, in a heroic attempt to stop Exxon-Mobil from turning 1,100 miles of Montana’s scenic byways into a primary transportation corridor for the Alberta Tar Sands via river-routed roads—including the road passing directly in front of Duncan’s house and home water, Heart of the Monster was

“We’re here for a little window, and to use that time to catch and share shards of light and laughter and grace seems to me the great story.”

-Brian Doyle

conceived, written, and published in fewer than three months. The proposed transportation corridor would have allowed articulating trucks, larger and heavier than the Statue of Liberty, to travel alongside five iconic Western rivers. The book required tremendous personal courage from both Bass and Duncan, and in the end, their cause prevailed.

“We went head to head with ExxonMobil at the time of their greatest power,” Duncan says, “And thousands of local heroes share the credit for stopping them. With our book, Rick and I were, so to speak, the Paul Revere figures yelling, ‘The Monster is Coming! The Monster is Coming!’ It’s still hard to fathom how our side won this fight to protect the Clearwater, Big Blackfoot, Nez Perce trail of tears, and other national treasures from being turned into Tar Sands’ tentacles. But when I drive along those rivers today, by damn, I don’t see a trace of Exxon’s ‘high and wide industrial corridor.’”

Barry Lopez described their effort

best. “What David Duncan, Rick Bass, and their colleagues have done with The Heart of the Monster knocked me across the room. They have breathed fire into a worldwide effort to make Big Oil, Big Ore, and Big Government accountable, to bring them to bay. And they have set a standard here—for citizenship, integrity, and courage.”

Amidst these involved writing and activist efforts, Duncan continued to produce stand-alone essays, published in scores of magazines and journals and over 40 anthologies, including Best American Essays, Best American Spiritual Writing (appearing five times!) and Best American Sports Writing. He also appeared in numerous documentaries. The River Why and The Brothers K were adapted and performed live on stage to sold-out performances at the acclaimed Book-It Repertory Theater beneath Seattle’s landmark Space Needle.

Most recently, Duncan edited, curated, and wrote the forward to, One

Long River of Song —a vast and heartfelt collection of writings by his close friend and much-loved Portland-based writer, Brian Doyle. Published in 2019, One Long River of Song is already in its second printing. On the back jacket of the book, the poet Mary Oliver writes, “Doyle’s writing is driven by his passion for the human, touchable, daily life, and equally for the untouchable mystery of all else.” It’s a description and attribute equally applicable to Duncan’s writing as well.

on a twice-failed cattle ranch joining forces with a few urban refugees who swallow their City Mouse vs. Country Mouse stereotypes.

Yet, for the past fourteen years, Duncan has primarily been in Montana, seated at the table of Sun House, writing a vast, multi-generational novel that is a fusion of eastern and western traditions with a chorus of blues, folk, and gospel music. Set against the mountains and rivers of the west and told through the perspective of multiple narrators, it’s the contemporary story of rural Montanans

While the community and characters in the novel are fictional, the implications of their viability are pertinent and pressing, based on the very best things David has seen, and in that sense, very real. “I’ve come to believe only love and justice can work this mess out. And will,” Duncan says, “as slowly and damagingly as selfish and cynical tricksters force it to. But I still see a path forward.” He’s written about this path with the urgency of a fireman entering a house ablaze and the calm wisdom of one who’s entered conflagrations before.

His writing days are six to twelve hours long. Occasionally he takes breaks for birds, mountain walks, and an occasional cast when fishing is good (a privilege reserved for those who live on trout rivers, whose fly rods are always against the wall strung up and at the ready

David told me, “I’ve seen countless op-eds calling for a change of consciousness if humanity is to survive. I’ve seen zero op-ed descriptions of what this con-

sciousness looks, feels, tastes, sounds, and lives like from day to day. That’s the void Sun House sets out to fill because that’s the void plaguing countless human lives.”

“Needed changes of consciousness are the through-line in my fiction, from The River Why to The Brother’s K and on to Sun House,” Duncan says, “and it will remain a throughline. Charles Eisenstein, an activist I admire, recently said in an essay titled ‘On the Great Green Wall, and Being Useful ’—“To heal the world, people must no longer be treated as standardized producers, functionaries, or medical objects in a global industrial system. Not only does this alienate them from the local knowledge and relationship needed to heal the places where they live, it creates legions of superfluous human beings.”

“Beginning with those wise, older women befriended when I was young… most of the people I’m closest to lead lives that are not only not superfluous, they’re heroic,” Duncan adds. “I reference scores of these people in the epigraphs that open each chapter of Sun House, like these words from Meister Eckhart: ‘When the

soul wants to experience something, she throws an image out in front of her, then steps into it.’…This statement reminds me of how you and your firehouse brothers step into a fire, Jimmy, ‘soul first’, and I admire that.”

appears…We don’t put water on the fire until we’re nearly on top of where it’s hottest. The only way this is accomplished is with love, and it can’t be accomplished alone. Here firefighters can only navigate in unison, with literal, physical contact and a complete change of consciousness, turning entirely away from the self.”

Adding logs to the fire, I mention a paradox I’m well acquainted with as a fireman: the way water is taken into the darkness toward flames, where the light hides. “Inside a house on fire,” I say, “it’s complete darkness…ink black.”

Duncan listens; his eyes are the color of a coastal river. “So, we navigate by feel and sound, searching for life and the seat of the flames, both felt well before they’re seen, inching toward them until a sun

As dusk arrives, and the shadows from the sun have all but disappeared, we move closer to the fire, and I remember something his friend Barry Lopez wrote before passing, “There are simply no answers to some of the great pressing questions. You continue to live them out, making your life a worthy expression of leaning into the light.”

This Duncan has done his whole life. Surrounded by darkness save the glow of the fire and its reflection against his face, his heartfelt truths and compassion are radiant. I can see it. The trees see it, as do the lost creeks. As do the hundred-billion suns in the night sky above us. Listening to him talk next to the fire, it strikes me that Duncan, now seventy, has become

an elder—a guide, one comfortable both in this world and the other, the inner. His stories read like gospels—where the word is the water, ‘where all worlds appear,’ and where Duncan is carrying it with cupped hands.

“We’re here for a little window,” his close friend, Brian Doyle, said, “and to use that time to catch and share shards of light and laughter and grace seems to me the great story.”

“What’s next?” I ask, to which

Duncan replies with the expected itinerary of an author with a completed book—the back and forth with the publisher, book tours, readings, etc., and he has other works on the backburner too. But that’s not what I’m asking about and he knows it.

“In response to Barry’s insight that the great questions have no answers,” he says, “I find the unanswerable to be a reminder that I was born lost, but in creeks and rivers began to be found. Watersheds

remain a place of pilgrimage, wild salmon an internal compass, rivers prayer wheels, industrialized rivers blues tunes, dying birds prophets and guides, wild places as small as weeds blooming in the cracks of city sidewalks a momentary home.”

Before retiring for the night, I try to describe to Duncan an experience I hold dear but can’t very well express, “Either I don’t have the words,” I tell him, “or by putting words to it, I’ll diminish the experience. I’m not sure which. Maybe

APRIL 13 - JULY 7, 2023

OPENING RECEPTION THURSDAY, APRIL 13 FROM 6 - 8PM

Suddenly seeing how it should go --the right word suddenly appearing, like a first glimpse of swallows.

it’s both.” Duncan encourages me by saying what his late friend William Kitteridge said, that ‘secret’ and ‘sacred’ are basically synonymous.

“I see her, sometimes in dreams and sometimes awake. I once saw her in a house on fire. But most often, she appears on the far banks of rivers, ankle deep, holding a fistful of field daisies, smiling beneath chestnut eyes and long brown hair. It’s

Dirty Dan

Saturday April 29 – Sunday, April 30

It was a dark and stormy night when the first train roared into Fairhaven Station in 1890. As torrential rain turned muddy streets to rivers of chocolate milk, the townspeople drank and danced at a lavish gala welcoming the railroad. No one imagined what would happen next ...

For event info: @enjoyfairhaven

Presented by:

and these great sponsors: www.enjoyfairhaven.com

silly...” I admit. “She’s an image, an imagination, an apparition, or an angel. Or maybe she’s only a memory. I just know that I love her, and when she’s there, I drop my fly at her feet hoping she’ll pick it up.”

“One of the heroines of Sun House might tell you,” Duncan answers, “that words aimed at such an event are trying to catch a thunderhead in the gopher trap of American English. But, from your long, sometimes impossibly intense friendship with fire and water, Jimmy, you know as well as anyone that the greatest love de-selfs us, making of us itself…So the story-telling problem you face here is wonderful: there are mysteries far greater than words or stories can contain.”

Hours after saying goodnight and unable to sleep, I’m lying awake beside our open bedroom window as the faint fragrance of smoke wafts in from the untended fire that’s long since gone out. It’s the black of night, ink black. From my angle of repose, even the starlight is unseen through the tree line and canopy and clouds, hidden. I can’t see outlines or shadows. Outside the dark vacancy of the window, I can’t see anything at all, but she’s there. I hear her whispers. They float on the back of warm ash in the breeze and are just as quiet—wordless and uncontained, sharing a secret and saying the purpose of all that we do connects us forever.

The Mountain Stream

by Stephanie StrongAdventures

Northwest recognizes that people are truly a part of nature, and that an adventure worth having should celebrate our wholeness with the lands, waters, plants, and creatures, rather than subordinating them to our own bravado.”

- Robert Michael Pyle

- Robert Michael Pyle

In 1975, writer Edward Abbey published his fifth novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang. It’s a comedic romp about a serious subject. In it, four misfits come together to perform acts of sabotage against the machines of environmental destruction. These threats to the sanctity of the southwest wilderness included construction equipment, roads, bridges, dams, and anything else helping humanity encroach ever further into the untrammeled wilderness.

The book spawned a new dictionary word: “Monkeywrench,” which means to sabotage equipment nonviolently. Abbey’s work is said to have laid the foundation for the Earth

First! movement, a radical environmental action group born in the American southwest that has since spawned chapters worldwide.

The character of Hayduke, easily the most charismatic of the Monkeywrench

Four, is based on writer and naturalist Doug Peacock. A longtime friend of Abbey’s, Peacock saw combat as a medic in Vietnam and came home a changed man. He started taking long solo tramps in the silent desert scrub of the American southwest, eventually discovering and falling in love with Yellowstone National Park.

Like his character Hayduke, Peacock is an unapologetic defender of wilderness and the creatures that

dwell within it. But, unlike Hayduke, Peacock isn’t quite so gruff and cantankerous. While uncompromising in his ethics, he is affable enough to have a group of fast friends who enjoy his company and join him on crazy adventures in the remote wilderness.

Now settled in a house in the Yellowstone area, Peacock has spent decades working to reintroduce grizzly bears into the National Park. Once the domain of these mighty bears, Yellowstone was home to just 136 grizzlies in 1975. Thanks partly to

Search of the American Wilderness (1990), chronicled twenty years of studying the grizzlies of Yellowstone. Armed only with camera equipment and notebooks, Peacock made startling discoveries about this apex predator: its habits, social hierarchy, communication methods, and placement in the wider ecosystem. Most importantly, Doug shares keen observations about the human-grizzly relationship. Having long ago immersed himself in the primal headspace of the wilderness; he shares his revelations about the grizzly soul and how these two apex predator species (us and them) regard each other when the playing field is leveled.

Peacock’s tireless efforts, the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem is now home to approximately 728 grizzlies (per a 2019 study). While an improvement, this is still a far cry from the pre-colonial population that once roamed this striking corner of the American west.

Peacock has spent a lot of time among the grizzlies: filming them, photographing them, studying them, and writing about them.

His first book, Grizzly Years: In

In his most recent book, Was It Worth It? A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home (2021), a compendium of his many adventures all around the world, Peacock tackles the question of grizzly safety: “Grizzlies charged me a couple dozen times. About half of them were serious encounters: mothers with cubs or yearlings, often from nearby daybeds where they were sleeping during the middle of the day. This is the source of almost all human mauling by bears… attacks by mothers near or on daybeds when humans get too close and carelessly invade the space the bear feels she needs for her cub’s safety.

“The sow only cares for her cub’s safety. As long as you are perceived to be a threat, she will continue to charge; and if you do anything stupid, like run or try

to climb a tree, she may start chewing on you. If you fight back, the mother griz will keep attacking you until you are no longer seen as a threat to her young. You could die.

“The advice to ‘play dead’ during a grizzly attack is sound. Many a victim

of a mauling saved his or her life by ceasing to resist the attack by relaxing. Tough advice, but it works.”

Not content to limit his grizzly research to Yellowstone, Doug has gone further afield to find and study these fabled creatures as well as many other impressive beasts that spark his imagination.

In Was It Worth It? Peacock recounts adventures that span the globe, from the High Sonoran Desert of Mexico to the remote forests of Siberia. The details of these trips are not limited to his experiences in the outback; Peacock also writes

beautifully about his strange and amusing interactions with the people he meets in the hinterlands of human society.

Each chapter transports us to a corner of the world that Peacock felt compelled to investigate. He tramps the tropical forests of Belize in search of the wild jaguar and sails the inlets of British Columbia to spy on the rare Spirit Bear. He charts a course for the Galapagos Islands to chase Darwin’s odd birds, lands in the Russian taiga to seek out the reclusive Siberian tiger, and even heads south to the Baja Peninsula to find remnants of our primitive ancestors. Ultimately, he comes home to make peace with his youthful indiscretions.

Each adventure is presented in Peacock’s signature style. He can be brusque and even vulgar, then turn rhapsodic with beautiful prose in praise of Nature. There is some Hayduke in Peacock, but some Ed Abbey is in there, too. His knowledge of flora and fauna is impressive, and his skill at describing the sublime will move you with its immediacy.

About his trip to the Sierra Madre in search of the last grizzly bears of

northern Mexico, he writes,

“The next morning, we awake to a landscape of melting snow. Our sleeping bags are wet but not soaked. We hadn’t expected the snow. But what the hell, it won’t last; this is April in Mexico, not Montana. Clumps of wet snow drop out of the trees and drip from the cactus. The green leaves of giant agave plants have triangles of decorative white snow wedged against the stalks. Bright painted redstarts, orange-bottomed bug-eating birds, flit in a nearby yucca, brilliantly contrasted against the green and white: Christmas in the Sierra Madre.”

While tracking the desert bighorn sheep in Arizona’s Cabeza Prieta Mountains, he writes,

“The reason I sleep well in the desert is probably because I walk so much out there. Traveling over the land on foot is absolutely the best way to see the country, scent its fragrance, feel its heat, and get to know its plants and animals; this simple activity is the great instructor of my life. I do my best thinking while walking—saving me thousands of dollars in occupational counseling, legal fees, and behavioral therapy—and the Cabeza Prieta is my favorite place in the world to walk.”

About his first sighting of a black Spirit Bear: “A half mile downstream, we round a bend and freeze: on the right bank, a plump black bear browses on huckleberries. We drift motionlessly toward the bear, which hasn’t seen us. The bear checks out a chum salmon carcass but leaves it where it lies; the fishing is better downriver. He is walking atop a log, grazing on the streamside vegetation as we drift alongside him. His head reappears with a mouthful of grass and forbs, and we hold our breath: The bear, though fewer than twenty feet away, hasn’t spotted us yet. This is natural. Danger doesn’t drift down the Aaltanhash in a red plastic log in this bear’s universe. We float away from the bear, and, suddenly, he sees us. His ears pop up, his mouth falls open, and a

F eaturing documentaries, multimedia presentations and sportsrelated workshops, the Mountain Film Festival coincides with the Mount Baker Ultramarathon, which starts and ends in Concrete’s Historic Town Center. Attendees can enjoy films and presentations in the 100-year-old Concrete Theatre, live music, beer garden, and other activities in Concrete’s historic Town Center!

mouthful of grass falls into the water. We suppress our giggles. After about thirty seconds of sizing us up, the bear decides to ignore us, and goes back to browsing. He behaves as if he has never seen a human, as if he has yet to learn to fear humans—a situation that may soon change.”

Each of Peacock’s adventures unravels with wit, insight, and devotion. Describing a place or an event isn’t too challenging, but bringing a reader into your consciousness and taking them along for the ride is something few writers capture well. At this, Peacock is superb.

So: how much of Hayduke is in Doug Peacock? Just enough.

If you have room on your nightstand, I strongly recommend Was It Worth It? Because, yes: it was worth it, Doug.

Every year, between 8 and 12 million tons of plastic, much of it single-use, enter the ocean. While larger pieces may break into smaller ones in the water and on the beaches, the plastic itself never completely breaks down. Individual pieces of plastic can be rendered microscopic, perhaps difficult to see, but they are not gone.

The issues surrounding marine debris and the high concentration of plastic in fresh and saltwater environments have been the Ikkatsu Project’s driving focus since beginning operations in 2012. By incorporating sea kayaks to access remote beaches in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere, we’ve collected data and tons of marine debris from some of the wildest places on the planet. This has allowed us to document the effect of the growing plastic load in the oceans – on all kinds of sea life, from plankton to whales, and extending to humans.

Although most of the work of the Ikkatsu Project over the past decade has focused on areas here in the Pacific Northwest—building kayaks out of discarded plastic bottles and Styrofoam, canoeing the Puyallup watershed freshwater to conduct microplastic surveys, and launching field studies in area middle

schools—we have also continued our efforts in Alaska, most recently at Cape Decision, on the southern tip of Kuiu Island.

The lighthouse at the tip of the Cape is one of the most remote locations in southeast Alaska, almost 100

sea lions, and salmon. Kelp forests run along the nearshore in many places, and there are always several eagles watching from the tall spruce trees at the edge of the forest.

Although fishing vessels and other craft frequently use Decision Pass, Cape Decision itself is difficult to access. The area is prone to high winds and inclement weather that makes dependable travel to and from the Cape and between certain points on south Kuiu extremely difficult. Beaches are rocky, and large swells can make landing and launching in small craft a risky proposition. As with literally everything else in Alaska, flexibility is the key to success.

miles west of Wrangell and just under 100 miles south of Sitka. The beaches on the windward side of the peninsula are exposed to the full force of the Pacific, while the eastern coves and inlets are more protected. As a result, the waters teem with whales and otters,

The volume of debris on the beaches in southeast Alaska is staggering. Fishing gear, plastic bottles, household items, and every other kind of plastic imaginable can be found on any island shoreline in large quantities. The program’s main goals, since its inception in 2018, include not only counting, weighing, and tracking the debris but also bagging, removing, and finally, transporting it to a landfill or other suitable destinations. Volunteers spend a week at the lighthouse and paddle or hike to clean up nearby beaches.

In addition to standard surveys and microplastic sampling, a multi-year

deposition study is going into its fifth year. It involves an effort by volunteers to ensure complete debris removal on the target beach, collecting and counting each item found until the shoreline is free of all plastic and other debris. By

continuing this process each successive year, we can be confident that anything collected has come ashore in the intervening time. Regularly repeating this process contributes to a better understanding of how debris travels and the

rate at which it accumulates on shore. With the addition in 2021 of a new deposition study beach on the island’s windward side, it will now be possible to use parallel data to compare impacts on each of the separate beaches.

Given the number of logs lining the high-water mark of each beach, and their deposition in shifting piles, often many layers deep, it can be challenging to determine exactly how much debris remains after a crew completes cleanup

To love and protect these wilderness shorelines is going to take an understanding of the threats they face and how our behaviors and habits play a part in the larger picture.

operations. However, they make every effort to get to beach level, and when debris is spotted, it is retrieved, even from under logjams. This is especially true for the deposition study beaches; any outsized or trapped debris found impossible to remove is documented.

Critical to the success of surveys and beach cleanups scheduled each July is the relationship between the Ikkatsu Project and the Cape Decision Lighthouse Society (CDLS), the organization responsible for the preservation of the historic building and the surrounding lands. Having a base camp as unique and adaptable as this one makes the program’s ongoing success possible and provides a lot of fun in the process. The CDLS Is a dedicated group of staff and volunteers with their own list of multiple projects to accomplish each summer, and the buzz of

activity, whether at the cape or out on a beach somewhere, is almost constant.

Since the start of the program, we’ve had dozens of volunteers make the trip, and they have been able to survey and clean ten different beaches within paddling distance of Cape Decision. (And everywhere is paddling distance if you have the time, right? More extensive trip plans are in the works.) The beaches are often rocky, and kayak landings are not always easy. Still, some locations are more accessible, including the mile-long sweep of Howard Cove, located about four miles north of the lighthouse on the exposed west side, a sandy swath of shoreline that looks more like California than Alaska. Some cleanup work was done at Howard Cove in 2019, but 2021 was the first year crews could complete full surveys, and it will not be the last. Of all the locations documented thus far, this is the one that likely has the most debris, with large numbers of buoys, bottles, and rope balls deposited well into the trees above the sand.

Surveys at various locations have yielded varying amounts of debris through the years. The outer coast beaches are more affected than those on the protected east side of the peninsula. Every beach we visited was significantly littered, and most of what we found was plastic. In total, 4,990 pounds of marine debris has been removed, with about 3,000 pounds bagged up and still awaiting transport back to Wrangell or Petersburg.

In 2020, the Ikkatsu Project released a film, Decision, a 12-minute story about south Kuiu Island, marine plastic, and the volunteers working to clean it up. Beautiful visuals of breathtaking Alaskan scenery, wildlife, and the lighthouse are woven into the story of plastic, how it got to such a remote location, and the decisions we all need to make for real change to happen. Selected to the Paddling Film Festival’s world traveling list and the online National River Supplies’ Duct Tape Diaries, the film is an excellent introduction to the work of the Ikkatsu Project. It is always hard to precisely say what the future holds, but there is no shortage of potential projects. The deposition studies remain a significant focus, as does working to remove the debris already collected. Beyond that, an extended kayaking venture is in the planning stages for 2023, a circumnavigation of the south

part of the island involving at least one significant portage and allowing for a series of surveys and a substantial assessment of the area. Going forward, the sea kayaking aspect of the South Kuiu Cleanup will continue to be a big part of the program, the best way to get volunteers into isolated locations to collect debris and data.

The problems associated with marine plastics have serious consequences for people and all other life throughout the food web. The fact that so much plastic is

on these remote beaches provides a powerful illustration of the ubiquitous nature of the problem. While the collected data can provide critical information, what matters is how researchers use and connect it between wild places like these and people everywhere. To love and protect these wilderness shorelines is going to take an understanding of the threats they face and how our behaviors and habits play a part in the larger picture. There needs to be that spark in each of us, that

recognition of responsibility and a desire for change. Working consistently toward that point continues to be the Ikkatsu Project’s primary goal.

For more information on marine debris, expedition reports, and news about upcoming programs, visit www.ikkatsuproject.org.

Ecologist Aldo Leopold defined wilderness as “an area that possesses no possibility of conveyance by mechanical means.”

Welcome to Mansel Island in Canada’s eastern Hudson Bay, where there are no cars, tundra buggies, ATVs, SUVs, motorcycles, or airplanes, all of which are mechanical conveyances. As my Inuit guide Jake and I explored this large, uninhabited chunk of limestone, I was obliged to use my feet, the very best conveyance of all.

It was a raw, gray day with drizzle and a leaden rack of clouds. At one point, we discovered an old Inuit burial cairn on a hillock. The cairn had a hole on top, so I peered inside and saw a well-preserved skeleton curled into a fetal position, suggesting the inhabitant of the cairn had lived in the late Thule Period (maybe 400 years ago). Inuit from that era believed their dead should exit the world in precisely the same posture as they had entered it.

I took my knife and gently turned the bleached skull until it faced me. The condition of the teeth would tell me

whether it had belonged to a male or female. If it had belonged to a woman, the teeth would be worn down from chewing skins, but if it had belonged to a man, the teeth would hardly be worn at all. As it happened, the skull turned

knife, but it wasn’t in its case. I looked in my pockets. Empty. I investigated the mesh flaps and pockets on the outer shell of my rucksack. It wasn’t there, either. Would I soon become insensible? For there’s an old saying in the Canadian outback that “A knifeless man is a lifeless man.”

“Maybe you left it at the cairn,” Jake said. So we walked back to the cairn, and I looked around but still couldn’t seem to find it.

All at once, I saw an arctic fox standing next to the cairn gazing at me with what seemed to be a wry grin. This seemed somewhat odd, since arctic foxes are seldom this fearless with respect to my species, especially so in the North, where they’re commonly trapped for their fur.

out to be a man’s.

“I don’t think you should have done that,” Jake said. “That guy could be an angakok (shaman), and he might decide to take revenge on you—maybe stick a knife in your skull.”

“I’ll take my chances,” I replied. Later, when we were nearly a mile away from the cairn, I reached for my

Lawrence Millman’s new book, The Last Speaker of Bear, is classic Millman: by turns respectful and irreverent, profound and whimsical, often funny, and always wildly entertaining. A collection of vignettes (several first published in Adventures Northwest) chronicling his many years of travels in the far north, this is not an adventure tale, nor does it possess a narrative flow. But it is rich with finely-wrought details of an arctic that most of us will never know, portraits of the indigenous people who have preserved ancient wisdom, (and suffered mightily), and, of course, Millman’s one-of-a-kind persona.

Occasionally, a fox will emit a high-pitched barking sound when it sees a person, then beat a hasty retreat. Once in a while, it will retreat a short distance, then peer quizzically at that person from behind a boulder. But this one uttered not a sound, nor did it withdraw.

Witnessing the fox standing fearlessly about ten feet away from us, Jake proclaimed: “That proves it. The person in the grave is an angakok, and he’s taken on the form of an akunnatuq (fox). He’s telling you, “I’ve stolen your knife, so you’ll never touch my skull with it again.”

However long I looked, I couldn’t locate the knife. Finally, I realized I had no choice but to conclude that the shamanic fox had indeed stolen it.

40 among strangers on a small Indonesian island––that one known for its population of giant carnivorous lizards, which we name dragons. In the morning, local guides herded little clots of tourists down a narrow path to a fenced enclosure, and from within, we studied groups of dragons: great lumbering beasts, drooling, tongues flickering. We were told that the old custom of feeding them goats for the entertainment of tourists had been ended; nevertheless, they circled our little enclosure expectantly. Threadbare deer grazed cautiously just out of reach, and our

guides told gruesome stories about the deer and feral goats, about the intersecting lives of the local farm-

No longer framed by the camera, he became real, and once real, he became abruptly terrifying, carrying the weight of a lifetime of bad dreams halfglimpsed and forgotten.

ers and these languid dragons. In brief spurts of speed, they said, the dragons could run down a grown man. Their saliva contained a nerve toxin. Once every year or two, a

farmer was killed and eaten.