ADVENTURES The Magic Skagit

Over the Top River of Stories

Essential Connections

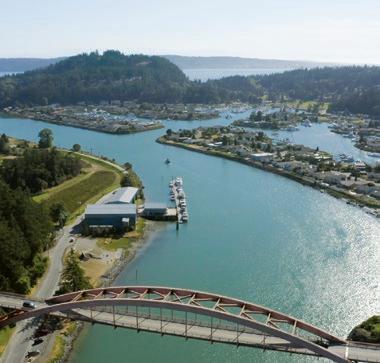

FROM THE NORTH CASCADES, FOLLOW THE SKAGIT RIVER THROUGH THE SKAGIT VALLEY TO THE SALISH SEA Marblemount

“I

all essentials—food, shelter, and extra clothes—humbly on my back. Except for spiritual nourishment and chance-encounter miracles, I expect nothing but water from a place. Ecstasy is always welcome, a bonus.”

- Michael Engelhard, Arctic Traverse

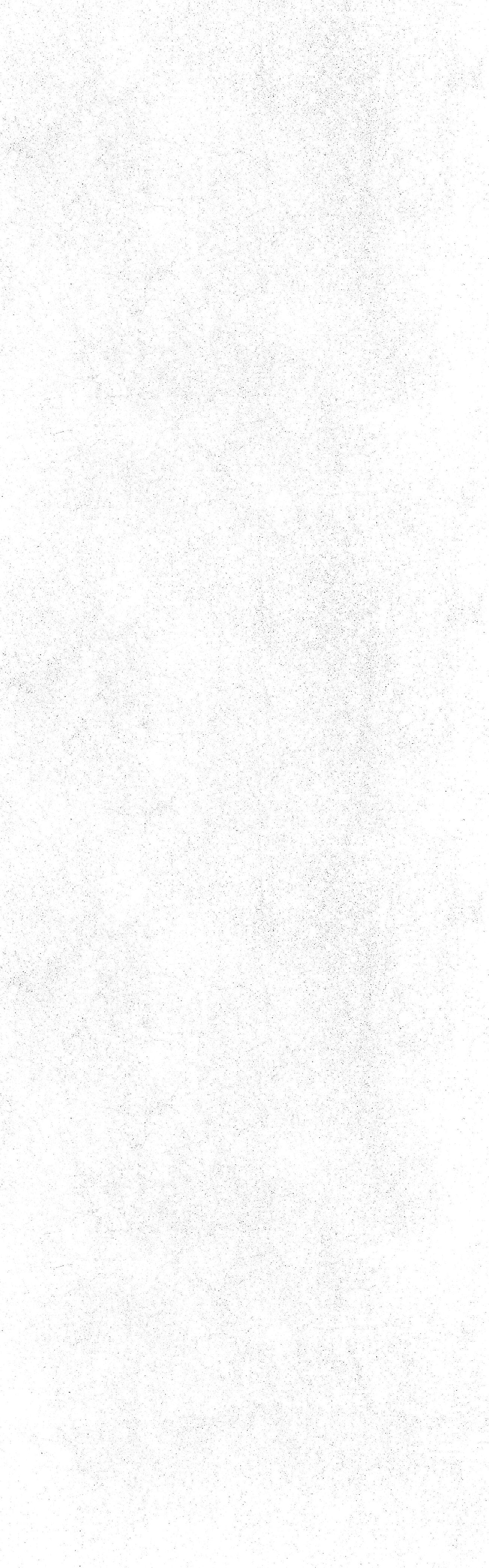

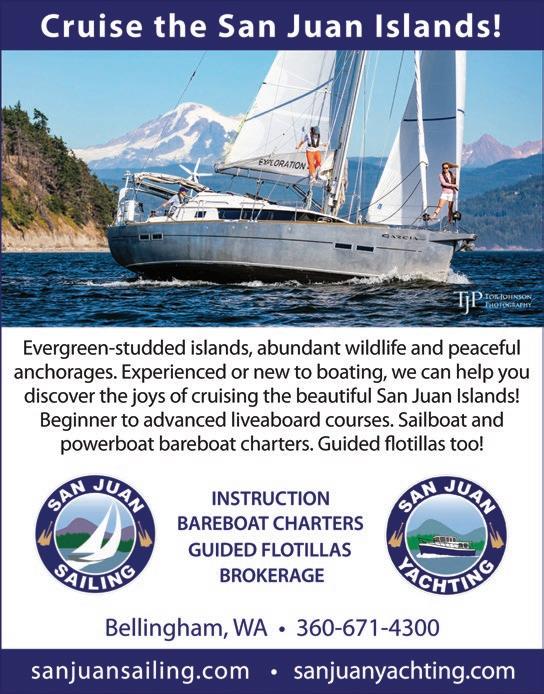

FISHERMAN’S PAVILION

FISHERMAN’S PAVILION ZUANICH POINT PARK

Third Saturday of each month during Bellingham Dockside Market.

Abram Dickerson is the owner/ principal at Aspire Adventure Running. As a husband, father, and entrepreneur, he attempts to live his life with intention and purpose. He loves mountains and the friendships that result from the suffering and satisfaction of running, skiing, and climbing in wild places.

Lance Ekhart doesn’t think he’s insane just because he keeps going to photograph the same places over and over in his sailboat, Elenoa. He actually achieves new and different results. He occasionally comes ashore to chase birds and regain his land legs.

Gregory A. Green is a career wildlife biologist and ecology instructor at Western Washington University’s College of the Environment. He is also an avid nature photographer (greggreenphoto.com) and writer. Greg’s latest nature writing is in the new book Wild Lives, a collaboration with award-winning nature photographer Art Wolfe.

Rand Jack grew up in northwest Louisiana with a stunted view of nature. Visiting Shi Shi Beach and Point of the Arches in 1967 changed his relationship with the natural world. Time spent in Yellowstone with Ranger Harlan Kredit deepened that relationship in profound ways.

Vikki Jackson has two inseparable passions: nature and creating. She retired from a career as a wetland ecologist but continues to spend her time outside making natural history discoveries as inspiration and muse for her paintings, which celebrate the diversity and magic of the natural world. Visit her at vikkijacksonartist.blogspot.com.

Christian Martin lives and plays in Bellingham, where he is a hiker, paddler, DJ, naturalist, and— for the last 17 years—communications manager for North Cascades Institute. Martin has lately been obsessed with traveling to Iceland and Ireland, where he explores remote coasts, Viking and Celtic history, bird life, hot springs, cozy pubs, and pints of Guinness.

John Minier is the owner and lead guide at Baker Mountain Guides. Originally from Alaska, he has a deep appreciation for wild and mountainous places. Since 2004, he has worked across the western U.S. as a rock guide, alpine guide, ski guide, and avalanche instructor.

Christian Murillo is a photographer and environmental storyteller based out of Bend, Oregon. His work seeks nuance both in nature and in our relationship with nature. His photographs have been featured in galleries, museums, and publications around the world. You can find more of his work at murillophoto.com

Ted Rosen was a longtime Greenways Advisory Committee chairman and remains a steadfast defender of green spaces, both large and small. When he

isn’t working his day job, he can be seen on local trails pointing out invasive species and complaining about litter.

Paul Tolme, the Journalist on the Loose, is an outdoors writer, awardwinning environmental journalist, and blogger for Cascade Bicycle Club. He lives with his wife in a Seattle houseboat crammed with bikes, skis, snowboards, kayaks, and paddleboards but has no regrets. His work can be seen at paultolme.com and cascade.org/news.

Saul Weisberg worked as a wilderness climbing ranger, field biologist, fire lookout, and commercial fisherman before starting North Cascades Institute. Now retired after 35 years as executive director, he loves paying attention to the natural world, canoeing in the rain, walking in the mountains and writing poems. He lives in Bellingham.

Bill Yake was an environmental scientist for the Washington State Department of Ecology. His latest poetry collection is Waymaking by Moonlight (Empty Bowl Press).

Is it the mighty river, the muscular, mysterious flow that carries generous rain and melting glacial ice 120 miles from the mountains of British Columbia to its broad delta on the Salish Sea, draining more than 3,100 square miles of cloud-shrouded forests and wind-swept peaks? The Skagit River is Cascadia writ large, supplying more than 30 percent of the water in the Puget Sound, transporting some 10 billion gallons every day. Home to all five species of our iconic salmon, this river is epic in every sense of the word.

gible, more ephemeral and ethereal, as evidenced by the voices of the poets, artists, and aesthetes that were drawn here to plumb the depths of their own consciousness, people like Snyder, Kerouac, Whalen, Robbins, and Sund.

Or, deeper still, the homeland of Indigenous people since time immemorial for whom the Skagit was the provider, the source of spirit and sustenance, the center of an existence rich in deep connections and the ingenuity of survival.

Or is it the land—the luscious Skagit Valley, filled with swans and tulips, a fever dream of fertility and bucolic beauty?

The Skagit Valley embodies a dream-like quality, an illustration from a children’s book, an Eden of plenty.

Or perhaps the essence of the Skagit is something less tan

In this special issue, we celebrate the Magic Skagit in all its sublime and unfettered glory, honoring its power and reveling in its timeless mystique. Places like this remind us of the complicated balancing act inherent in nature—and in our own attempts to find our place in the world.

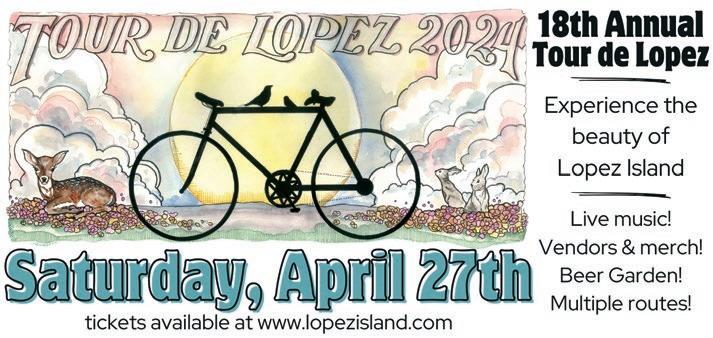

On April 1st, the Skagit Valley will once again begin its month-long celebration of floral radiance in what has become North America’s largest Tulip Festival. The festival runs through April and features numerous display gardens, art shows, a street fair, barbecues, a parade, and acres and acres of luminous tulip blossoms.

The Tulip Festival has become an iconic Pacific Northwest event, attracting flower aficionados from around the globe. This beloved event’s origins can be traced back to 1883 when George Gibbs settled on Orcas Island. The transplanted Englishman had a botanical bent and planted orchards of apples and hazelnuts on his new homestead. He purchased $5 worth of tulip bulbs and raised a bumper crop of the flowers, which until then had been the exclusive providence of growers in Holland. By 1905, with some help from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), his crop had grown to 15,000 bulbs. The USDA established its own 10-acre tulip test garden near Bellingham, which eventually gave birth

to the Bellingham Tulip Festival in 1920. But Whatcom County proved a more difficult location for raising tulips. After several years in which the bulbs froze, the festival was discontinued, and the growers moved south to Skagit County.

In 1950, a sixth-generation tulip grower from Holland named William Roozen started a tulip farm on Beaver Marsh Road outside Mount Vernon. In 1955, he purchased the Washington Bulb Company, an established grower of tulips, daffodils, and iris.

In 1984, the Mount Vernon Chamber of Commerce launched the first Skagit Valley Tulip Festival, a weekend-long event that, over the years, has grown into the monthlong celebration that we know today.

Roozengaarde, as William Roozen’s farm is known, remains a centerpiece, offering a five-acre display garden with more than 1 million bulbs planted by hand each year, 50 acres of tulip and daffodil fields, and a gift shop.

But there’s more to the Tulip Festival than

Roozengaarde. Tulip Town, Garden Rosalyn, and Tulip Valley Farms also offer botanical feasts for the senses. Salmon barbecues, organized by the Kiwanis Club, are held every weekend in April, as is English Tea at Willowbrook Manor. The festival’s annual Tulip Parade commands center stage in La Conner on April 6, and Mount Vernon celebrates with a Street Fair on the weekend of April 19, featuring more than 140 artisan vendors, live music, food trucks, and children’s activities.

But with all this activity, perhaps the best way to savor this beguiling natural spectacle is to find some quiet time out in the fields as the sun goes down, rendering the valley in pastel hues. There’s a lot to be said for taking the time to stop and smell the flowers.

More info: tulipfestival.org

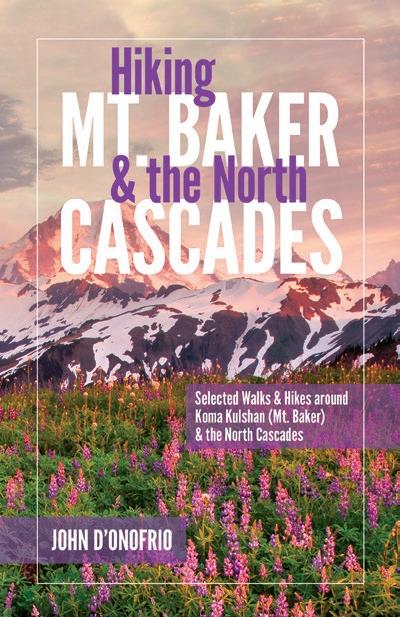

Mountaineers Books, Seattle, 2023

Edited by Elizabeth Bradfield, CMarie Fuhrman, and Derek Sheffield Review by Cathy Grinstead

The Cascadia Field Guide is not your ordinary natural history guidebook. If you’re looking for a comprehensive guide with detailed scientific descriptions and glossy photographs to slip into your daypack to aid in field identification, this may not be the book. But, if you want to be transported into the interconnected world of Cascadia through art, poetry, and elegant prose, this is for you. Edited by three poets with roots in Cascadia, the book has 140 contributors—writers, artists, and poets—and each brings a unique perspective to their subject.

The book begins with a definition and a map of Cascadia, which extends from the north at Valdez, Alaska, south to the coast ranges of northern California, and east into the Sawtooth and Bitterroot ranges of Montana and Idaho. It is a larger territory than one would imagine and encompasses the “watersheds of rivers that flow into the Pacific Ocean through North America’s temperate rainforest zone.” The authors divide their book into 14 chapters, each describing different Cascadian ecosystems, and the chapters are subdivided into essays about the quintessential flora and fauna of the area. Starting with prose, the natural history of each subject is discussed, including descriptions of Indigenous uses and mythology. A poem and pen and ink drawings of the subject round out the discussion. By the time you finish each section, you will have a better understanding and appreciation of the harmony between species that exists in each ecosystem and how that translates into the larger world of Cascadia. The artistry of this guidebook will linger long after you turn the last page.

TThe Old Sauk River Trail offers the spring hiker an easy opportunity to explore the rich textures of a vibrant rainforest, on par with the legendary lushness of the Olympic Peninsula. Along the way, you’ll pass through remnants of towering old-growth forest, curtains of hanging lichen, an understory carpeted with emerald green moss, luxurious fern gardens, and enough mushrooms and fungi to tantalize even the most discriminating mycologist. The river is not always in view, but the rhapsodic music of flowing water can be heard throughout your walk. Here and there, openings in the thick forest afford opportunities to stop and watch eagles fishing in the roiling current. There are several access points—my recommendation is to start at the north trailhead and walk the length of the trail, enjoying the lavish greenery all the way to Murphy Creek and back for a sixmile journey through the intensely green heart of the rainforest.

Trailhead: From Darrington, drive south on the Mountain Loop Highway (FS-20) for four miles to the north trailhead. No permit required.

The 4-mile out-and-back trail into the Methow’s Pipestone Canyon provides a welcome early-season hike that follows an old roadbed, popular with mountain bikers, into a picturesque canyon rimmed with sandstone hoodoos. This is open country, a breath of fresh air after a long winter, and wildflowers often illuminate the canyon floor. The trail winds down into the canyon, passes through aspen groves, and then breaks into an expansive meadow filled with birdsong. The going is easy, and the spring sunshine is abundant!

Trailhead: From Winthrop, drive the Twisp-Winthrop Eastside Road for two miles and turn left on Bear Creek Rd. After 2.3 miles, turn right on Lester Rd., taking the right fork to the trailhead parking lot. Washington State Discover Pass required.

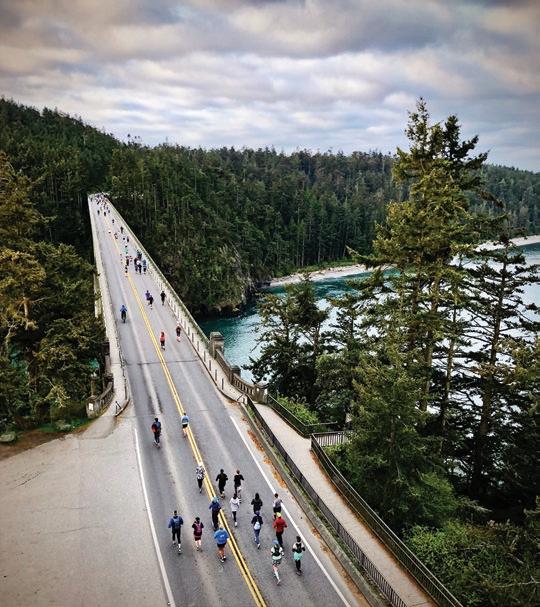

As an introduction to the splendor of the wild Olympic Coast, the hike to Third Beach affords ready access to a dramatic destination where waves pound offshore sea stacks and a spectacular waterfall plunges more than 100 feet off a cliff into the Pacific. From the trailhead, the route winds through mossy coastal forest for 1.4 miles, eventually dropping to the beach where it is necessary to negotiate a jumble of driftwood logs to gain access to the beach proper. The sand offers easy walking to the south, eventually reaching a headland that must be climbed using the provided ‘sand ladder’. From here, the South Coast Wilderness Trail leads to wonders such as Strawberry Point and Toleak Point, marquee destinations for the intrepid (and well-prepared) coastal hiker. NPS Backcountry Permit required for overnight use.

Trailhead: From Port Angeles, drive US-101 for approximately 55 miles, turning right on WA-110 approximately 1.5 miles north of Forks. In 10 miles, the Third Beach Trailhead is on the left. No permit required.

In the three years I spent photographing and writing my new book, Soul of the Skagit, I listened to countless people affectionately refer to the river as the “Magic Skagit.” Sure, it has a ring to it. But I was relatively new to the Pacific Northwest, and besides the obvious beauty of the Skagit River and the North Cascades, I was curious about what made it so “magical.” Was it the towering mountains? Or the abundant wildlife? Or maybe the brilliantcolored lakes?

It only took one three-day backpacking trip in the North Cascades with my dad to begin to understand what made this gem in a remote corner of the Pacific Northwest so special. Our backpacking adventure was intended

to be a scouting trip. I was looking for a new photography project in the Pacific Northwest in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since my parents had just moved to Washington from Miami (where I grew up), I figured throwing my dad in the deep end of the North Cascades wilderness would be

therapeutic. Considering it was also his first time camping, we took it relatively easy, something that is surprisingly difficult to do in the rugged terrain of the North Cascades interior.

items from his pack into mine. I wanted to bond with him, not torture him during the 2,600-foot climb to Cutthroat Pass. About two miles in, he started asking me about what potentially dangerous wildlife we might find. At three miles, his nervous questioning continued, probing whether I was sure I locked the car. For my dad, the concept of backpacking must have seemed outlandish. He emigrated from a very modest upbringing in Bolivia then spent his whole life pursuing the comforts of modern-day America. Why on earth would someone intentionally leave their climatecontrolled home and plush memory foam mattress in favor of sleeping on a two-inch thick blow-up sleeping pad while temperatures plunge below freezing?

Scientists estimate that there are more ice worms on some of the larger glaciers in the Skagit than humans on earth.

We packed our bags at Cutthroat Trailhead, just north of the popular and scenic Washington Pass area. As my all-too-stubborn father was going to the bathroom, I snuck a couple of the heavier

We moved slowly and steadily up the switchbacks, hiking for about four hours to make the six miles up to camp. With daylight to spare after setting up camp, filtering water, and cooking dinner, my dad anxiously asked, “What do we do now?” I grinned and replied, “Absolutely nothing.” Doing nothing was not normal for my dad. He spent his

entire life either working multiple jobs to put himself through school and then selflessly and ceaselessly devoting himself to a quota-driven career in sales. “Doing” was how he learned to exist. For him, there was more comfort in the idea of staying busy rather than taking a step back to soak it all in. When I encouraged him to let his mind simply wander, I began to see the magic of the Skagit firsthand.

than I had ever seen him.

It had only taken about six hours from when we left the trailhead until we’d set up our camp, and everything that needed doing for the day was done. As he reclined back into the hammock with golden larch needles gently dropping onto him from their drifting branches, I saw my dad more relaxed

The sheer natural beauty of this wilderness surely had a big part to play in my dad’s transformation. Endless mountain layers pierced the horizon. Luminous larches draped the alpine landscape— lakes and streams nestled in the valleys below. Still, there was something more.

I would like to think that my dad’s

repose was also a product of our inherent connection to this landscape, one that humans have fine-tuned over 300,000 years of interacting with nature as a part of our very existence. Even here on this rugged land near Cutthroat Pass, the indigenous ancestors of the Upper Skagit, Chilliwack, Nlaka’pamux, Wenatchi, and Syilx (Okanagan) peoples have called this home for over 20,000 years.

These early occupants of this land thrived not despite the rugged landscape and harsh winters but largely because of those same factors. From the snowy 10,786 summit of Koma Kulshan (Mt. Baker) all the way down to sea level in Skagit Bay, at different times of the year, this watershed is filled with resources that occupy various parts of the landscape.

Snow covers much of the mountainous landscape in the winter, but life in the Skagit continues to thrive; countless salmon surge upstream to spawn in their ancestral waters, each species favoring different tributaries and gravel beds. With the help of the glaciers and shade from the riparian forests, the waters of the Skagit are kept cool enough for salmon to favor this river more than any other that flows into the Puget Sound. In part, the cool water is why the Skagit is the only river in Washington that is still home to all five species of Pacific salmon, plus bull trout and cutthroat trout, which are also in the salmonid family.

Of the salmon in the Skagit, Chinook is king, returning to spawn upriver in the autumn. Not only does their average size of roughly 30 pounds earn their “king salmon” nickname, but so does their cultural and ecological importance. Chinook are the favorite meal for the endangered southern resident orcas, comprising 80% of their diet.

yet delicate. Both species are listed under the Endangered Species Act, and their populations are intertwined in their success and challenges. With about 60% of the total Puget Sound chinook population coming from the Skagit River alone, there is no place as critical for the future of these iconic species as the Skagit.

like an entirely different world than the salmon-filled water thousands of feet below, it is perhaps the driving force that makes the entire watershed function the way it has since the last ice age. While it is easy to assume that this dramatic alpine landscape is too extreme to support any life, perhaps part of the magic of the Skagit is its ability to trick us.

The relationship between the resident orcas and the Chinook is inspiring

As the ecological and man-made stressors that threaten the resident orcas and salmon have increased, Washingtonians have not sat idle on the sidelines. Huge conservation initiatives have been implemented to measure and limit noise pollution, reduce toxic waste in Puget Sound, and open more spawning and rearing habitat for the salmon, among countless other efforts. These are worthy initiatives, and it is refreshing to see so much passion going into recovering these two icons of the natural world. However, I cannot help but feel like sometimes we are trying to place a new roof on a building with an unsettled foundation. While orcas and salmon carry immeasurable cultural value, they depend on entire ecosystems, such as those within the Skagit watershed. Much less revered organisms than orcas and salmon fill many of these ecosystems, but those life forms are just as important.

Interestingly, one of the ecosystems that impacts the success of orcas and salmon the most is the alpine zone, high above the river. Although this seemingly inhospitable terrain of ice and rock feels

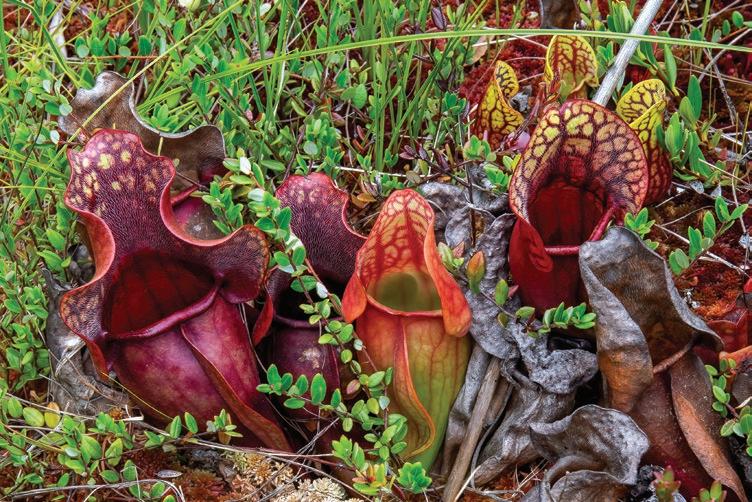

The approximately 370 glaciers in the Skagit are home to a select group of hardy animals. Their specialized characteristics and behaviors are precisely what allows them to thrive here, where few others can. One amazing example of life in these icy expanses is the ice worm. Ice worms might sound like something from a sci-fi movie, but they are a very real and integral part of the alpine ecosystem. Scientists estimate that there are more ice worms on some of the larger glaciers in the Skagit than humans on earth.

This abundance is staggering, because the truth is, we don’t know much about these eyelash-sized creatures. What we do know is that they only live on glaciers. Due to their extremely limited range, they need year-round access to ice in order to survive. Ice worms can survive within the snow and ice because of highly specialized anti-freeze proteins. These proteins allow the worms to carve through the ice during the day and then come to the surface at night to feed on bacteria and algae on the frozen surface.

Ecologists and biologists are currently trying to figure out what value ice worms have to the watershed as a whole. We know there are a lot of them, and we know what they eat and what eats them. But if the glaciers in the North Cascades continue their current recession rate due to climate change, then what would that mean to the ice worms and, hence, the rest of the ecosystem downstream?

Other parts of the watershed can

give us clues as to how valuable those ice worms and the glaciers they live in are to all of life further downstream. Despite their reputation for heroic rainfall, the North Cascades receive shockingly little precipitation in the late summer relative to the wet winter months. During these dry spells, the glaciers bestow their reserves of icy, fresh water downstream. This significant contribution of glacial meltwater in August and September happens just in time for the spawning Chinook. The many frigid tributaries keep the main body of water in the Skagit cool throughout its path towards the Salish Sea.

Cold, rushing water is essential for salmon and countless other animals in the Skagit. Salmon won’t spawn in tributaries without enough water to travel upstream, and their eggs won’t hatch if the water is too warm. The glaciers, while critical, are not alone in keeping these ideal conditions intact.

The riparian forests throughout the Skagit also help keep the river cool. Where the trees grow tall, they provide shade, and the dense vegetation of the understory helps control erosion, benefitting the salmon and the entire riverine structure. Salmon reciprocate in this relationship as they swim upstream in their last gasp for life. Shortly after their eggs have been laid and fertilized, the salmon die in the same tributaries in which they were born. Some carcasses wash ashore, while various scavengers, including eagles, carry others into the forest.

Once the salmon flesh is consumed, their skeletal remains are left to decompose on the forest floor. While their sacrifice gives life to their offspring, their post-mortem sacrifice is equally important. The salmon carcasses decompose into the soil with the help of insects, bacteria, and fungi. This process provides the plants with a vital source of a special ocean-derived nitrogen compound, 15N. While all plants need nitrogen to grow, very few plants have the ability to source it from the air, where it is plentiful. They rely on bacteria, and in this case, salmon, to bring nitrogen to their root systems. The trees in the Skagit carry the nitrogen that the salmon bring from faraway oceans into their heartwood, helping them grow taller and stronger.

The Skagit is full of cyclical, intertwined relationships like this. We can see it within specific biomes like the riparian forests or the alpine glaciers. More importantly, we can see it between biomes across different elevations throughout the Skagit. No matter how tight we zoom in or how far we zoom out, interdependencies and a spider web of relationships reveal themselves.

We humans fit somewhere in that spider web, or at least we are intended to. Perhaps that is where the “magic” of the Skagit lies. In those little moments, lying in a swaying hammock, supported by the flexible structure of the golden larches, we reconnect with the wilderness. Maybe sometimes our role in that spider web is to repair some of the broken strands of silk.

Other times, perhaps our role is simply to listen and observe, tipping our hats to the sublime balance of all things wild.

The earliest people in the Skagit showed us ways to live that celebrate the wildness of this incredible corner of the Pacific Northwest. Somewhere along the way, we started mistaking the abundance of the Skagit for an inexhaustible well, abusing our status as beneficiaries of the river’s resources. We sought to conquer the watershed’s wildness, moving the earth to tame its natural fluctuations.

Now, as we seek paths toward healing the wounds caused by centuries of extraction and manipulation, knowing which way to turn can be difficult. We are only beginning to understand the complexity of this interwoven network of life. Even armed with the latest science paired with Indigenous records and ways of knowing, we are just beginning to understand this incredible river. Yet, the sooner we reckon with the complexity of the natural systems at hand, the sooner

we can develop solutions to ensure a “Magic Skagit” exists for future generations of all living beings.

Watching my father unwind while backpacking was quite a juxtaposition. In moments such as these, life just seems so simple. At the same time, it is the extremely complex relationships in nature that afford us this perspective. My dad was able to make the personal transformation from stressed serial worker to sunshine-soaking backpacker in a matter of hours. His inspiring metamorphosis lasted the rest of the backpacking trip and likely beyond. Not only was this the validation I needed to spend the next three years of my life dedicated to and immersed in the sacred Skagit, but it was proof that we all belong here. An 82-year-old couple camping in a tent just up the ridge from us affirmed this belief, as they appeared to belong in this rugged landscape as much as anyone else we ran into on this trip. Beyond the awareness that despite our diverse back-

grounds, the wilderness is our home, I also began my process of learning how the wilderness of the Skagit can be transformative.

Witnessing animal migrations in the Skagit changed me. Listening to glaciers bending and cracking, eventually releasing chunks of ice thousands of feet down the valley, changed me. Being invited to document the fishing culture of the Upper Skagit tribe as members passed the knowledge down to new generations during their sockeye harvest changed me.

In its unrivaled ability to change us, the Skagit is perhaps the most magical place I have ever been. I will always be grateful for what the river gave me in the three years I waded its tributaries, climbed its mountains, and paddled its waters. Yet, if there is one thing I can give back, it is to tell the story of the Skagit River because it so deserves to be heard. Maybe you, too, will one day find yourself immersed in the Skagit, forever changed by its wild waters.

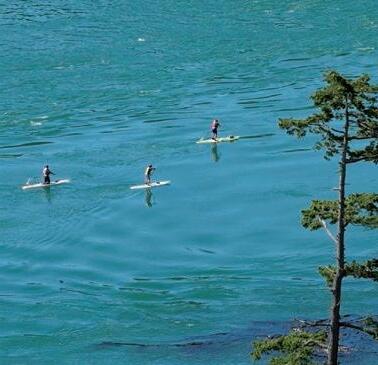

The Skagit River sustains humans in many ways, from providing drinking water to irrigating crops and nurturing fisheries. Of course, the basin is also home to a profound richness of wildlife, including bears, salmon, bald eagles, otters, trout, voles, elk, swans, and the Pacific giant salamander. The river is a popular destination for recreation— camping, kayaking, rafting, fly-fishing, skinny-dipping—as well as spiritual sustenance. Paying a visit to the Skagit in any season can be a ritual, a wellspring of peace, a space for reflection and renewal.

The Skagit River is also a fount of creativity, one of my favorite lenses through which to view the river and the storytelling heritage its flowing waters continually inspire.

Rivers have enkindled stories throughout history, from underworld rivers in Greek mythology to sources of

Long ago, in the time before the great changes, the river ran in both directions. The people were happy. The water carried them wherever they wanted to go. In those times, all the people and animals were together. They spoke the same language—they had the same spirits. The wise ones—coyote, otter, and raven—advised the Old Creator on how things should work. They had many arguments but worked out most other things.

But Raven, he didn’t stop arguing. He complained and complained about the river—he thought it should run one way. One day, Old Creator had enough. He decided that some people, especially Raven, were asking too many questions. He was tired of listening to them. He decided to make some changes.

purification in Hindu traditions to world creation in Norse tales. The Skagit is no different. Its waters, fish, plants, and animals have nourished the spiritual and mythological life of the region’s original people, including the SaukSuiattle Indian Tribe, the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community, the Samish Tribe, and the Nlaka’pamux Nation. These liminal dimensions are often expressed through stories.

In surveys by anthropologists, the Upper Skagit people have many stories involving three particular figures: mink, raven, and coyote. All were “mythological trickster transformers, supernaturals in the form of these animals but as large as

One change was that people and animals would be different and speak in different tongues.

Another change was that each person would have to make themselves very clean by bathing in the river and going without eating, so spirits could enter them and give them power and wisdom to know how to live. But things would not be easy—the river would always run one way. People would have to learn to find their way through the currents.

And Raven, he was changed to the way he is now. He wears feathers, sits in the tops of trees, and complains all day—and no one listens to him.

From Voices Along the Skagit, courtesy of North Cascades Institute

humans, capable of speech, living in houses, and to a certain extent behaving like humans“ according to Allan Smith in his study Ethnography of The North Cascades.

“Myths were told in evenings for the children, who were expected to sit just so and be attentive,” he explains. “To increase interest and give the tale a vitality of its own, a good raconteur changed his voice for different characters and added details of his own choosing.”

The excellent collection of stories from Puget Sound’s indigenous cultures Haboo, translated and edited by Upper Skagit native speaker Vi Hilbert, shares folklore from tribes dwelling around the Skagit River. Tales like The Legend of the Humpy Salmon, Legend of the Season, Basket Ogress, and Wolf Brothers Kill Elk and Beaver are full of hyper-local details and a dazzling, sometimes bewildering mix of voices from animals, ancestors, spirits and the elements.

Many centuries later, closer to our present era, the Skagit River inspired two distinct and important American literary movements: the Beat Generation and the Northwestern counterculture of the late 1960s-70s.

Washington-born poet and essayist Gary Snyder worked for the US Forest Service as a fire lookout in the North Cascades, first on Crater Mountain in 1952, then Sourdough Mountain in 1953. His Reed College roommate and fellow poet Phillip Whalen joined him, manning lookouts on Sauk Mountain and

These experiences on remote mountaintops near the river’s headwaters provided fertile periods for self-reflection, connecting with nature, writing, and exploring Zen Buddhist philosophy and meditation.

Looking down from his Cascadian perch towards the river, impounded behind Ross and Diablo dams, Whalen wrote:

Morning fog in the southern gorge

Gleaming foam restoring the old sea-level

The lakes in two lights green soap and indigo

The high cirque-lake black half-open eye

Snyder’s lookout journals were published in Earth House Hold, and poems inspired by his Skagit sojourns enliven his books The Back Country and RipRap Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout opens with these details from wildfire season:

Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies.

Snyder—who later won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry—con-

vinced his writer friend Jack Kerouac to follow in his footsteps. In the summer of 1956, the East Coast urbanite spent 63 days as a lookout on Desolation Peak facing down imposing Hozomeen Mountain, where the Skagit River flows over the border from Canada. His popular experimental-prose novels Desolation Angels and The Dharma Bums immortalized the intense isolation and immersion in wilderness.

In an essay from his collection Lonesome Traveler, Kerouac describes the journey up the Skagit:

“At Marblemount the river is a swift torrent, the work of quiet mountains.—Fallen logs beside the water provide good seats to enjoy a river wonderland, leaves jiggling in the good clean northwest wind seem to rejoice, the topmost trees on nearby timbered peaks swept and dimmed by lowflying clouds seem contented.—The clouds assume the faces of hermits or of nuns, or sometimes look like sad dog acts hurrying off into the wings over the horizon.—Snags struggle and gurgle in the heaving bulk of the river.—Logs rush by at twenty miles an hour. The air smells of pine and sawdust and bark and mud and twigs—birds flash over the water looking for secret fish.”

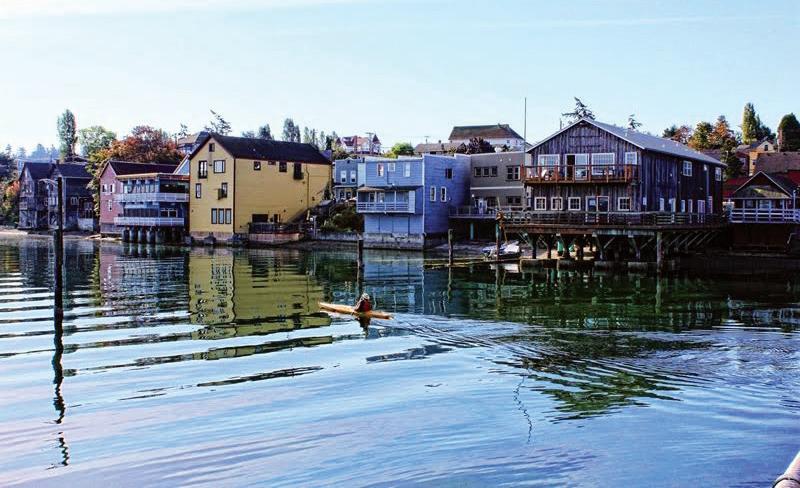

Several decades later, at the other end of the river, another counter-cultural

movement arose as a group of writers, scholars, and artists collected like a logjam in the Skagit’s northern estuary. Occupying a motley assortment of abandoned cabins and gill-netter shacks, the group formed a sort of commune named Fishtown. Fixing up and inhabiting the rustic structures, they practiced meditation, calligraphy, sculpture, music-

making, painting, and voluntary poverty as the Summer of Love of the late 1960s crested and spilled over into the 1970s.

Robert Sund was among this eccentric crew—occasionally known as The Asparagus Moonlight Group. Born in Olympia, Sund spent summers logging in the Olympics, working wheat harvests in Walla Walla, and fishing in Alaska. At the University of Washington, he studied creative writing under the mentorship of

Theodore Roethke and soon dedicated himself to the simple life of a poet and spiritual seeker.

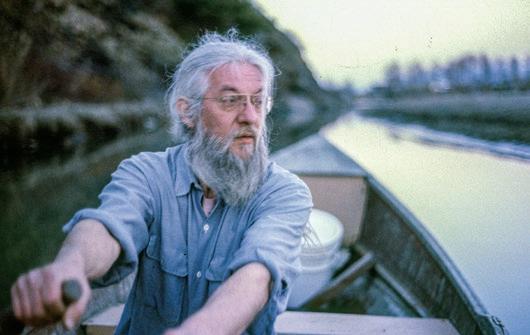

In the summer of 1973, Sund built a hermitage from salvaged lumber on old pilings near Fishtown. With no running water or electricity and accessible only by boat, he dwelled there off and on for the next dozen or so years, writing, playing his autoharp, brewing tea, communing with nature, and observing the cycles of the seasons—the Skagit’s own modern-day Thoreau.

“Out on the river you know you are in the midst of a great creation,” Sund wrote. “You see the old work and the new work side by side; the ancient migration routes of all the birds, and the slow building of silt and soil in the estuary…”

Sund produced a flood of poems during his time on the Skagit, published in small-batch chapbooks, including Why I Am Singing for the Dancer and Shack Medicine. Most of his poetic output was collected and republished posthumously in Poems from Ish River Country, as were his river journals. According to his editor and friend Tim McNulty, Notes from Disappearing Lake is comprised of short, pithy entries from more than “75 small, thin Chinese notebooks of near-weightless paper” from 1973 to 1987. McNulty, a Northwest

poet, also spent summers as a fire lookout atop Sourdough— coincidentally including during the 50th anniversary of Snyder’s stint in 2003, “a lovely synchronicity,” as he describes it. His mountaintop poems were published in the chapbook Through High Still Air and the collection Ascendance.

Notes from Disappearing Lake offers observational gems like Arriving Home Late at Night from July 2, 1978:

Rowing upriver in the dark I startle a beaver.

Chopping kindling at midnight I wake the frogs.

I light a fire & make tea.

At last, falling asleep, I leave the night to the owls calling in the Bald Island woods.

Around the same time, just a few paddle strokes downstream from Fishtown, writer, and literary prankster Tom Robbins settled into the sleepy fishing and farming village of La Conner. From his perch on the Swinomish Channel, he conjured up cult

classic novels, including Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, Skinny Legs and All, and Jitterbug Perfume.

“October lies on the Skagit like a wet rag on a salad,” Robbins observed in Another Roadside Attraction. “Trapped beneath low clouds, the valley is damp and green and full of sad memories. The people of the valley have far less to be

unhappy about than many who live elsewhere in America, but, still, an aboriginal sadness clings like the dew to their region; their land has a blurry beauty (as if the Creator started to erase it but had second thoughts), it has dignity, fertility and hints of inner meaning—but nothing can seem to make it laugh.”

Experimenting with nonlinear plot lines, collage techniques, sentient inanimate objects, and an attempt not to recreate the psychedelic Sixties on the page but instead “to mirror in style as well as content their mood, their palette, their extremes, their vibrations, their profundity, their silliness and whimsy,” as he once described it, Robbins has sold millions of books in multiple languages around the world.

What is it about the confluence of the glacier-fed waters of the Skagit River intermingling with the salty Sound that inspires prose and poetry as potent but diverse as Sund and Robbins?

“A river mouth, in and of itself, exerts an influence on human consciousness

that becomes manifest in music, literature, and art,” opines Robbins in his essay The Tao of Mud. T.S. Eliot celebrated rivers as great brown gods. Could it be that where such a god French-kisses the vast maternal sea... forces are released that spur a particular brand of intellectual activity?”

Every river is a unique expression, an interconnected braid of physical place and metaphysical meaning. Rivers not only show us where we are but also reflect back who we are. From the headwaters in Canada to its union 130-some miles later with the Salish Sea, the Skagit River has inspired, influenced, and informed centuries of stories and storytellers. We are lucky for this local legacy. Long may the creative waters flow!

SCAN TO LEARN MORE & REGISTER!

On the shores of Lake Crescent

Camping Encouraged! CAMP DAVID Jr.

The old idiom “can’t see the forest for the trees” describes being too wrapped up in details to see the big picture. But in close-up photography, the details are what matter—a recognition that the blanket of frozen, dead leaves on the ground or the tiny mushroom sprouting from a rotting log is the “forest,” just as much as the towering trees above. During my career as a wildlife biologist, I spent many years scanning grand landscapes, searching for specific animals. Now, I find myself observing nature in a different way. I am drawn to its abstract beauty, moved by the changing symmetries of reflected light, inspired by the repeated patterns of intertwining shapes and colors in the flora, fauna, and geology of tiny, overlooked landscapes at my feet. I see artistry in nature’s chaos. My photography is often serendipitous, something I stumble upon, which works—as long as I keep stumbling about.

See more of Gregory A. Green’s photography at www.greggreenphoto.com

Visit AdventuresNW.com to view an extended gallery of Gregory’s photography.

Washington State Route 20 (known as the North Cascades Highway from Marblemount to Winthrop) is the state’s longest and most scenic highway. If you’ve traveled in the North Cascades, you’re already familiar with it. SR20 stretches from Whidbey Island in the west all the way to the city of Newport on the Idaho border. Along the way, it winds along the Skagit River, through the North Cascades National Park (NCNP), down into the picturesque Methow Valley, east through the Okanagan, across the Columbia River at Barney’s Junction, through the rugged Colville National Forest, and down along the Pend Oreille River to the state border, where it terminates at US Route 2.

it is believed that some intrepid Natives regularly made the perilous journey.

The history of the North Cascades

Company found well-maintained Native trails through Ross Pass and Suiattle Pass in the Glacier Peak Wilderness. Further north, fur trappers found extensive networks of usable trails along the Methow, Twisp, and Stehekin Rivers. Evidence was thin, but it became apparent that this east side trail network also led to pathways crossing the mountains at Washington Pass, Rainy Pass, Hart’s Pass, and Slate Creek, which is approximately where SR20 is located today.

Wild and rugged, the North Cascades are a formidable barrier to transportation and commerce. Nonetheless, centuries before Europeans first visited, Native tribes forged overland trails from Lake Chelan to the Sauk Valley near Darrington. While there is limited evidence of organized crossings between the Methow and Marblemount to the north,

Highway rightfully starts with those hardy Native travelers who dared to struggle across this steep and deeply forested landscape. Their tracks have long been overgrown but their efforts didn’t go unnoticed. When Europeans first arrived, they found networks of trails on both sides of the North Cascades that appeared to have links deep into the mountains. It would take more than a century for those early pioneers to construct a viable connector over the northern section of the mountain range. Their efforts culminated in the completion of the North Cascades Highway in 1972.

The dream began in 1811 when employees of the British North West Fur

Nonetheless, most ancient commerce occurred further south, at Stehekin and the passes near Glacier Peak. The Skagit Indian word “Sta-he-kin” (Stehekin) means “the way through” or “the crossing place.” The Native Americans had already sussed out trail infrastructure that led from the east side of the North Cascades all the way to the mouth of the Skagit River, moving people and goods from one side of the North Cascades to the other.

To the north, the Methow Valley had been mostly depopulated by the 19th century, and the northern mountain passes were little known to locals.

In 1814, Alexander Ross, an employee of the British North West Fur Company, set out with Native guides to

cross the North Cascades at what we now call Cascade Pass. It was an arduous trek. The team laboriously hacked through endless miles of thick rainforest and traversed log-choked creeks and rivers. The expedition was miserable and nearly failed several times. Ross noted in his diary that the path through the mountains was “...gloomy forest almost impervious with fallen as well as standing timber. A more difficult route to travel never fell to man’s lot.”

Upon reaching the western foothills, a much-relieved Ross found “a delightful country of hill and dale, wood and plains...a good many beaver lodges along the little river [Skagit River]” and “some small lakes, and grazing deer in herds like domestic cattle.”

With the previous difficulties having reduced the expedition to a party of two, a freak windstorm shattered them, and they disbanded. Ross struggled to make his way back home over the North Cascades, disillusioned and hopeless.

His plan to realize a useful crossing from Methow to the sea had failed. Little did he know he was just four miles from completing the journey.

Despite Ross’ failure to blaze a new trail in the north, the pressure to do so mounted. Fur trappers and mining interests were keen to move massive loads from the resource-rich inland areas to the shipping lanes of the Puget Sound. Connecting the Methow Valley to the Skagit River via a new “Cascade Wagon Road” became a serious project.

At the same time, the federal government hoped to build a rail link through the North Cascades. This newfangled rail technology required a gentler connector than a wagon road. This was a tall order in this mountain wilderness, but in 1853, the rail survey task fell to Captain George B. McClellan, who later became Commanding General of the US Army during the Civil War and eventually governor of New Jersey.

After carefully surveying the Twisp

and Methow Rivers into the North Cascades, McClellan concluded that these waterways led only to impassible mountains, wholly unfit for rail travel. Like previous adventurers, McClellan felt that the only workable route was at Snoqualmie Pass. The northern route was impossible. McClellan was roundly criticized for not trying hard enough. Known for his intemperate tongue, McClellan refused to hand over his logbooks because he had peppered them with insults about his superiors, including Isaac Stevens, the sitting governor of Washington Territory.

In 1857, the US State Department authorized a Northwest Boundary Commission led by Archibald Campbell. He hired a diverse team to tackle the wild north and survey potential crossings. Campbell hired geologists, naturalists, and topographers to get a better picture of this complex and majestic mountain range. Also on the exploration team was artist James Madison Alden, whose vivid watercolors are the earliest depictions of

the mountains, meadows, and glaciers of the North Cascades.

Campbell’s team also included a topographer, Henry Custer, who spent years exploring mountainous terrain from the Fraser River to points south. His team successfully marked the boundary with Canada at the 49th parallel. An avid and eager mountain climber, Custer was also credited as the first person to cross Whatcom Pass. During his border survey work, Custer and his Native American canoe team started at the Canadian portion of the Skagit River, where they paddled due south on the river, making occasional portages along local trails. As they headed further south on the Skagit, Custer remarked:

“Nothing can be more pleasant than to glide down a stream like this; the motion is so gentle; the air on the water cool and pleasant; and the scenery, which is continually shifting, occupies eye and mind pleasantly.”

a canyon. The river flows here between rocky banks, with a swiftness and impetuosity which even makes my expert Indian canoe men feel more or less uncomfortable. From the anxious looks they cast around, I conclude that it is about time to look out for a secure harbor for our canoe.”

Ever the topographer, Custer climbed

peditions were launched to conquer Cascade Pass. In 1870, the Northern Pacific Railway sent surveyors who successfully marked a foot trail. Small mining parties, trappers, and gold-seekers followed. Yet the dream to build a commercially navigable northern route remained unrealized. The large extraction industries appealed to the government, which commissioned Lieutenant Henry Hubbard Pierce and a small army expedition in 1882.

Astonished by the natural beauty of the eastern hills and the glory of the North Cascades, Pierce and his crew surveyed and marked a path over Cascade Pass to the tiny hamlet of Mount Vernon. This successful expedition became the focal point for further efforts to tame the North Cascades.

Eventually, the team made it to what we now call Ruby Creek along the future route of the North Cascades Highway. Custer thought it might be a tributary of the Skagit River. It was tough going at this point, with Custer writing:

“We rapidly enter the beginning of

the local peaks and made careful notes of the landscape. Having already gone further than his remit, he and his team eventually headed back north, stumbling into the Pasayten Wilderness, where they climbed several peaks and made detailed surveys of the land.

After twelve quiet years, more ex-

In the summer of 1895, the Washington Board of State Road Commissioners tasked a party of surveyors led by engineer Bert Huntoon to create a comprehensive survey of 500 square miles of the North Cascades. Their ultimate goal was to plot a Cascade Wagon Road, now known as State Route 17, from Marblemount to the Methow Valley. Still a wild and unexplored place, the existing maps and notes of the area were considered “woefully erroneous and misleading.”

The party started from Marblemount, carefully noting elevation, barometric pressure, and land profiles. They also noted every creek, prospector’s cabin, family home, and crude pathway they found along the way. They had an easy time heading east along the Skagit River until they reached the expansive meadow we now call Newhalem. From there, dead-end mining roads, dangerously crude bridges, and plenty of rockfalls tormented them. Unable to plot a workable wagon trail, they took the southern route to go back inland over Snoqualmie Pass, then swung around to the north and attacked the problem from the east.

Starting from the confluence of the Methow and Twisp Rivers, they plotted their way to Cascade Pass, only to find the west side of the pass plummeted steeply into a large basin where the current Cascade Pass Trailhead is situated. Building a switchback wagon road with any measure of safety seemed impossible. Undeterred, they went back east and

marched up to Thunder Creek Pass, now known as Park Creek Pass, on the eastern slope of Buckner Mountain. But the pass was narrow, with no options that made economic sense for a wagon trail.

Huntoon’s team continued surveying multiple mountain passes, hoping to find a viable path for the Cascade Wagon Road. Among their four primary options was one along Ruby Creek. None of the crew was aware that Alexander Ross visited this area in 1814 and Henry Custer in 1859. Huntoon noted that at Ruby Creek was an area “...along which a trail had never been even blazed.”

Huntoon’s notes were eventually published, and the commission decided on a route for the Cascade Wagon Road south of what is now the North Cascades Highway. Their study concluded that “the route up the Twitsp [sic] River, over Twitsp Pass, down Bridge Creek, up the Stehekin River, over Cascade Pass and down the Cascade River is the shortest and the most feasible and practicable.”

Our third annual Mountain Film Festival features documentaries, photography presentations, sports-related workshops and a special showing of MountainFilm on Tour from Telluride, Colorado.

Work commenced in 1895 to build a forty-foot-wide road from Stehekin, northwest along the Stehekin River, to Bridge Creek. They never finished the project as the sheer volume of treefall and massive glacial rocks frustrated every effort. Today, parts of this “Old Wagon Trail” are incorporated into the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail.

Undaunted, the commission started blazing the Cascade Wagon Road from the west side, starting at the Cascade River just northeast of Rockport. This effort also failed. The wildlands were too much for the technology of the era. Over $100,000 was expended on the wagon road, with precious little to show for it. The dream of the Cascade Wagon Road sputtered out. Instead, the primitive wagon road further south over Snoqualimie Pass got a major upgrade in 1909, timed to coincide with a well-promoted New York to Seattle auto race.

World War II. Some forward-thinking locals formed the Northern Cross-State Highway Association (NCSHA). Their goal: build a new highway connecting the Diablo Dam in the west to Mazama in the

Open 7 Days a Week in Downtown Winthrop! 222 Riverside Ave., Winthrop, WA 509-996-3480 cascadesoutdoorstore.com

It would be seventy-seven years before the North Cascades Highway would open to the public. Ironically, SR20 follows a pathway considered by the old Washington Board of State Road Commissioners to be the most expensive, longest, and least feasible option for a wagon road across the North Cascades. This belief remained after State Road 15 (now part of U.S. Route 2) was finished in 1931, connecting Leavenworth to Everett over Stevens Pass. Much like the ancient Stehekin pathway, it succeeded. Route 2 was considered good enough, and there was little movement to build a highway further north.

east. In 1947, the state legislature balked. Any potential road up there would have limited seasonal access and wouldn’t attract enough traffic to prove worthwhile. Once again, the project was shelved. But by the 1960s, the population in the Pacific Northwest had grown enormously. They were a hardy bunch and very much in love with their wilderness. Voices became a chorus, and the initial construction of a North Cascades Highway began on both sides of the mountains, courtesy of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT). Local Knowledge One-on-One Customer Service Hand-Picked, Trail-Tested Gear Tents, Backpacks, Sleeping Systems, Supplies

Rumblings about a potential North Cascades Highway began again after

Concurrent with the road construction was the potential designation of a new North Cascades National Park. The proposal caused a major shakeup in Washington state. The folks at NCSHA and a wide array of outdoor enthusiasts, economic development councils, farmers, guides, fishermen, and even skiers opposed handing the North Cascades over to the National Park Service (NPS). They were concerned that the NPS would turn the North Cascades into a fee-laden payto-play recreational nightmare.

They preferred the light touch of the Forestry Service, which was largely hands-off when it came to regulating recreational activity in the mountains. Might that change with a National Park designation and the steadier hand of the NPS?

Since most of the timber in the mountains was uneconomical to extract, the North Cascades was still generally untouched wilderness. In yet another ironic twist, the Western Forest Industries

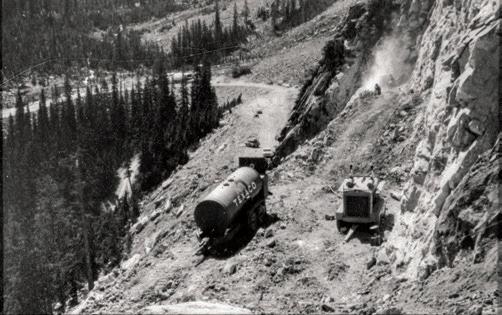

In July 1943, James T. Ovenell and a group of men went on a planning expedition to scout a safe route for the North Cascades Highway. Mr. Ovenell was a former Skagit County Commissioner of the 2nd district from 1940 to 1946 and served as State Representative from 1950 to 1958. He was instrumental in planning the highway, intended to open commerce in the Upper Skagit Valley. Mr. Ovenell and Harold Pierson bought 730 acres in the 1940s in Concrete, WA. They began the P &O Ranch, which later became the Double O Ranch and Ovenell’s Heritage Inn log cabins & guesthouses. Today, his descendents run a working cattle ranch focused on conservation and accommodations for travelers to the North Cascades. Learn more: www.ovenells-inn.com

Association and other timber industry councils felt that a National Park designation would be a good thing despite it locking up all the timber in perpetuity.

“We see nothing wrong with the proper use of the North Cascades for recreational purposes. After all, our workers on their vacations and weekends are some of the greatest users of recreational facilities on our public lands.”

The timber industry had better prospects elsewhere. Creating a North Cascades National Park (NCNP) was no skin off their apple.

The discussions and arguments about a National Park teetered back and forth inside and outside Olympia for years. For his part, President John F. Kennedy recommended the creation of the NCNP. He tasked the Departments

of Agriculture and Interior to fund a study completed in 1966 and recommended the creation of North Cascades National Park. The exact size and borders of the park were hotly debated. After much compromise and a litany of expert opinion, the North Cascades National Park was designated on October 2, 1968.

As the Forest Service handed the keys over to the National Park Service, a primary issue remained: access. The North Cascades Highway was inching its way into the park from the west and the east, but thirty treacherous miles remained to clear, grade, and build before the connector was complete.

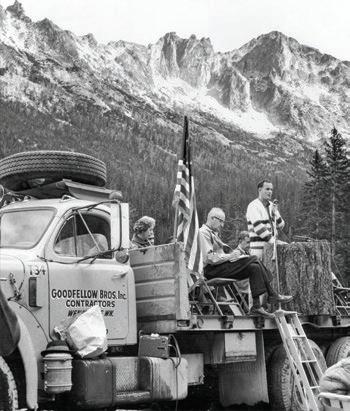

Technology had improved somewhat since the 1890s when efforts to build the Cascades Wagon Road first began. With the might of the WSDOT on the job, the final connector was completed, and a ribbon-cutting ceremony took place on September 2, 1972. In attendance were the Concrete High School Marching Band, Governor Dan Evans, and Richard Nixon’s brother Ed. They all traveled in a victorious vehicle procession over the

stunning central spine of the park.

True to form, the highway closed due to snow conditions on November 26, 1972, just eighty-five days after it opened.

Today, the North Cascades Highway is a multi-purpose road. It serves as the border, splitting the NCNP into its two primary sections, designated the North Unit and the South Unit. It’s a primary corridor for goods and services to reach the Methow Valley, weather permitting. It helped put the cow town of Winthrop on the map.

It’s easily the most impressive leg of the famed Cascade Loop tour, Washington state’s premier sightseeing trip. Visitors from all over the world can drive up Whidbey Island, across the beautiful Skagit Valley, up into the North Cascades for a dazzling view at Washington Pass, back down into the Methow Valley, south to the stark, rolling countryside of Chelan and Wenatchee, back up into kitschy Leavenworth, across Snoqualmie Pass, and back down to civilization in Snohomish county. Along the way there is more hiking, skiing, mountain climbing, snowshoeing, fishing, and

See more of Vikki’s art at www.vikkijacksonartist.blogspot.com.

kayaking than one lifetime could permit.

What started as an Indian footpath 8,000 years ago is now a comfortable, speedy cruise into one of America’s most breathtaking landscapes. The Diablo Lake Overlook is the most photographed spot in the park, and rightly so. While most folks make a quick stop at Washington Pass for photos, more intrepid visitors venture into the Liberty Bell Group for challenging hikes and climbs. This area is also a favorite for backcountry skiers, providing unmatched beauty as a backdrop for bold free heelers.

Should SR20 close for the season, local guides offer snowmobile access for truly memorable winter ski adventures at Washington Pass. Cascade Pass and Rainy Pass also offer easily accessible ski adventures and climbing opportunities for visitors willing to exchange some sweat equity for an exhilarating experience.

The North Cascades Highway makes all this possible. It was a long time coming, and we’re awfully lucky to have it in our backyard. ANW

"Itravel across the skin of the earth, much like a blade of grass, held gently, travels across my skin. I imagine my hands and my feet moving over the ground in such a way that the earth finds sensuous. I feel her playful pinch in the sharp plants that I pass. I feel her desire in the heat of the rock upon which I lie. I feel her longing in the shadows that she stretches across her canyons.”

So reads a journal excerpt from my time spent wandering the canyons of Cochise in Southern Arizona. I have been moving across landscapes my entire life. What began as a selfish pursuit of adrenaline-fueled adventure sports has matured into a mutual love affair with the world. Some say Mother Earth…I say Lover Earth. I belong to her as much as she belongs to me. No longer am I simply a visitor to wild places. I am a dance partner. The earth and I find a rhythm with each other, improvising if necessary, choreographing when we can, but mostly just expressing ourselves through meaningful movement. She is the wave below my board, the powder under my skis, and the wind in my sails. She likes to let me think I’m leading, but we all know who’s really in charge.

I have taken my tears to her more than once, and I have felt held and loved by the earth as much as I have felt held and loved by my community of humans. Sometimes, even more so. Humans are messy creatures with lots of big emotions, and we often fear that we are going to be “too much” for other humans. But I’ve never felt like I could possibly be “too much” for the earth. She’s always had my back.

And I have hers.

MAY 5 3 : 00 PM

Let's wrap up another unforgettable season of live music with an exhilarating program, featuring composer & clarinetist Kinan Azmeh.

TStory by Saul Weisberg

TStory by Saul Weisberg

hese four poems originate from 20 years of canoe tripping on the Skagit River from Ross Lake to the Salish Sea. The Skagit is a river, a watershed, a cultural identity, a place of spirits, and a home. As a guest on native land, I acknowledge the people whose longhouses and seasonal camps bordered the river from the mountains to the sea since time immemorial. Their descendants include the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe and the Swinomish Indian Tribal Community.

Mare’s tails fill the sky, sweat runs into our eyes, we pull into the wind.

Six-hour paddle up the East Bank, steady wind and whitecaps. We stand in knee-deep waves to unload the canoe.

Summits rise above cloud-shrouded mountains, pale October sky.

Many trails linger below the surface of the lake.

Some day the dams will be gone –old campsites emerge.

Skagit mist rises spring floods fill Newhalem Gorge it was all like this before.

People name things even if they already have names that’s not the worst we do.

Far below

Diablo Lake a silver thread late morning sun.

Sunset beach broken paddle yesterday’s rapids.

The waterfall is full of good intentions and pools of abundance.

Diablo Gorge narrows the river turns on its side salmon wait.

Skagit River –a dark ribbon of moving light. Spring rain brings flowers, summer rain feeds the people, fall rain quenches fires, winter rain calls the salmon home.

Paddling through this land, your stories witnessed by trees, we know the stars by different names.

In the calm between storms, the night is alive with the cries of migrating geese.

We paddle through green valleys, listening for the calls of small birds. 18 miles on the river today, past Sauk Delta rocks and snags.

In the long twilight of a summer afternoon we build a fire in rocks by water, camp on narrow sand spit in tall grass.

Tomorrow, downstream, the day after, downstream.

Photo by John D’Onofrio

“It just got better and better every day, from serenely calming and peaceful to heart pounding excitement. We learned so much from you all and will never forget your warmth, your generosity and your humor. Loved spending this wonderful time with you all. Many thanks!” Ann

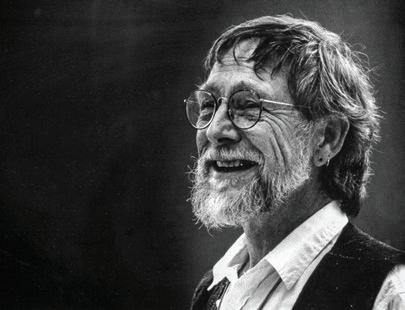

Harlan Kredit was raised in Lynden, the epicenter of conservatism in the rural northwest corner of Washington State. Lawns were expected to be manicured, but lawn mowing on Sunday was forbidden. With 29 churches, many of which are Christian Reformed, Lynden is said to have one of the country’s highest per capita ratio of churches—one church per about every .09 square miles. In 1981, Lynden passed an ordinance outlawing dancing in establishments where alcohol was served. Calling dancing “evil,” a city council member observed: “I’d like to dance, but I see the harms and evils that come from it. Like guys dancing with other guys’ wives, so I don’t know what can come of it.”

Harlan graduated from Lynden Christian High School (LCHS) and Calvin College. After teaching away from his hometown for 11 years, he returned to Lynden to teach high school science for 45 years at his alma mater. Harlan sent generation after generation of students home with the understanding that there are differing views on the age of the earth and its inhabitants. He also coached track and was the LCHS athletic director for 30 years, a highprofile role in the Lynden community. In 2017, Harlan retired but stayed on the payroll at a dollar a year so he could con-

tinue to serve as a substitute teacher and drive a school bus on field trips.

“Every morning, I have a bowl of Wheat Chex and take on the world. It’s exciting for me to get up and think, ‘So, what’s going to happen today?’”

Starting in 1972, Harlan began a second job as a summer ranger at Yellowstone National Park, a position that continues to this day

Linda, Harlan’s beloved wife and pillar of support, died in April 2023 after

Christianity is not just there because he teaches in a Christian school, not put-on, never pushy; just always evident in everything he does.” So, who is this person, Harlan Kredit? He is a legendary teacher, an uncompromising conservationist, a man of science, an accomplished outdoorsman, a national park ranger for 51 years, the product of a very conservative community, and a person for whom Christian ethics are essential to who he is.

Whether at Yellowstone or Lynden Christian High, Harlan is a teacher. Whether describing to visitors the microbial life in Yellowstone Lake’s thermal vents or working with his students to release coho salmon fry in Lynden’s Fishtrap Creek, Harlan is, first and foremost, a passionate teacher.

57 years of marriage. They attended the 3rd Christian Reformed Church of Lynden. Together, they had two daughters and a son.

Harlan’s hobbies include mountaineering and backcountry exploring, beekeeping, repairing old cars, and restoring antique player pianos. He is a devout Christian whose religious faith is central to his life. As a student said: “His

I believe I was ‘called’ to be a teacher and, particularly, one who emphasized stewardship and conservation. I am a man of faith and have always believed that God has made a beautiful world and stewardship is one of our highest responsibilities towards his creation.”

While hiking in a meadow on Church Mountain at the age of 12, Harlan saw a black bear for the first time.

“That scene is vividly etched in my mind. At a very young age, I decided I wanted to be a biology teacher. God has let me live out my dream of teaching science from a stewardship perspective in Christian high schools.”

When Harlan returned home after

15 years away, he found that Fishtrap Creek, which had been jammed with salmon when he was a boy, was practically devoid of fish. What had become little more than a drainage ditch became an inspiration for him. “I wanted to develop some hands-on programs for my science classes that were practical, useful, exciting, and beneficial to the community. I wanted them to be based on sound Christian stewardship principles, such as fulfilling the biblical command to ‘tend the garden.’”

Fishtrap Creek fit the bill and became the centerpiece of Harlan’s teaching and stewardship at Lynden Christian.

This many-year, holistic student restoration and conservation project has been handed down to successive LCHS classes for over 40 years. With a focus on the science, the project began with his students compiling a 200-page survey of the 12-mile length of the stream, mapping such things as erosion concerns, riparian vegetation, and large, woody debris. The project has developed from a small salmon egg box at the high school to an enclosed, fully functioning coho salmon hatchery. So far, students have released approximately three million coho salmon fry into the stream, removed tons of

invasive vegetation, and planted over 10,000 native trees and shrubs on the banks of Fishtrap Creek. They have engaged the community with a popular brochure describing the project, installing over 1,400 warning signs on the city’s storm drains and signs at every bridge crossing declaring that THIS STREAM IS IN YOUR HANDS.

Over the years, approximately 750 senior biology students have managed the hatchery, tending to the fish five times a day, seven days a week, regardless of weather. About 5,400 younger students have worked on stream restoration, and solid classroom science backs up the hands-on work necessary to understand salmon biology and stream restoration.

Each year, Harlan has taken students on field trips—in the fall to the Cascades to see the origin of the river system which includes Fishtrap Creek, and in the spring for three days camping on the Olympic Peninsula to witness where freshwater delivers salmon into the salty sea. In Harlan’s retirement, the project continues with his support.

Looking back, Harlan reflected: “Our stream restoration project has become a meaningful way for thousands of students

to make a connection between biological science and the community in which they live. We hope that connection will help them become more productive and discerning citizens. All I have been trying to do is to train my students to be better stewards. I would like to believe that they have learned a valuable lesson in how to take care of God’s world. And yes, the salmon are returning.”

“My teaching style is active, enthusiastic, and passionate. Kids should learn through ‘sweat equity’ by going outside the classroom. To have students buy into a project, they must have ownership of it, and that comes from actually doing the work. Blisters are OK.”

Harlan is emphatic “that our young people need to understand how critical conservation issues are to our health and the survival of the planet…. My goal is to cultivate a sense of stewardship with these kids, that they realize how fragile the world is and they are accountable for their actions. I believe that one day God will ask each of us what we have done to tend his garden. What an exciting

and enormous challenge and blessing to be able to work with our students in God’s vineyard, helping to restore a fallen world.”

Harlan’s stewardship/conservation teaching philosophy has distinguished him and led to national recognition. He has received over 20 teaching awards,

Christian’s Principal noted that “he brings the classroom alive for students, and he has an amazing ability to get kids excited about not only biology but taking care of the world.” But perhaps this comment from one of his students says it best: “What truly sets Mr. Kredit apart is that as incredibly well as he teaches biology, he teaches life even better.”

including the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching, the nation’s highest commendation. He was the first teacher from Washington inducted into the National Teachers Hall of Fame.

On the occasion of Harlan’s Presidential Award in 2004, Lynden

In 1782, President Grant signed a bill creating Yellowstone National Park, the first U.S. National Park, indeed the first national park in the world. Harlan has been a ranger at Yellowstone for 51 years, slightly more than a third of the life of the park. Almost certainly he knows more about Yellowstone and has spoken to more park visitors than anyone ever.

On the shore of Lake Yellowstone, 250 people came together in July 2022 to celebrate Harlan’s 50 years as a Yellowstone Ranger. The Park Superintendent presented Harlan with his third Superintendent’s Outstanding Achievement Award: “Harlan has dis-

tilled this art [of interpreting the Park to people] to a relatively simple principle. If your passion for the park leads you to ever greater breadths and depths of knowledge, your passion and love will be evident to all you encounter... Nearly 150 million visitors have come to Yellowstone during Harlan’s career. His countless visitor interactions inspire thousands from around the globe each year. His love of Yellowstone, whether in the classroom, on a hike, walk, or wildlife jam, has inspired people to learn about Yellowstone and become future stewards of its preservation.”

The celebration prompted Harlan to reflect on his long tenure in Yellowstone: “Perhaps the most fulfilling for me is that four generations of my family now have connections to the park. Our three kids all grew up here and learned to swim on the shores of Yellowstone Lake. All three at one time worked for the park service. My daughter Karen and her husband are still park rangers, and my 15-year-old grandson recently began as a volunteer. In 1971, my first summer, my parents visited. Now, with my grandkids and my daughter, we’re fishing in the same place where I fished with my dad and mom 50 years ago. Yellowstone has given me a sense of place. It is where I belong. We are a Yellowstone family. This park is who we are.”

The head of Yellowstone’s Education

and Youth Programs knows Harlan well. “His in-depth experience and knowledge bring incomparable richness to Harlan’s interactions with park visitors and with his peers and colleagues. Harlan is a naturalist in the best and richest sense of that word. It takes a love of natural history and enjoyment of spending time in the great outdoors to become a naturalist at the elite level of Harlan’s knowledge and skills.”

Harlan’s unique relationship with Yellowstone has included escorting various VIPs around the park, including National Parks Service Directors and the Secretary General of the United Nations, and participating in the visits of Presidents Carter, Clinton, and Obama. When Secretary of the Interior Deborah Haaland concluded her presentation at the Old Faithful Visitor Center in 2022,

and asked to hear about his Yellowstone experience.

I have watched Ranger Kredit talk to countless park visitors. Impromptu, he weaves together stories, history, science,

and stewardship with a freshness and enthusiasm that seems to say, “You are the first I have ever told this to.” The presentation invariably becomes a conversation— whether the subject is the microbiology of the thermal vents at the bottom of Lake Yellowstone or why Hayden Valley is a great place to see bears and wolves.

As Harlan tells it, the geology determines the biology. Glaciers carved a great basin; then, a glacial dam impounded a gigantic lake. Very, very fine sediment collected on the bottom of the lake. When the ice impounding the lake melted, the silted lakebed remained like a piece of Visqueen plastic on the former lake bottom. Water can’t penetrate the Visqueen-

like layer, so there is enough moisture for grass to grow even in the middle of the dry summer, and the sediment keeps trees from getting a foothold. Because the grass is there, the bison and elk are there. Because the bison and elk are there, the wolves and bears are there. Thus, the geology of these glacially dammed lakes makes for excellent big-game watching in the Hayden Valley.

While visiting with Harlan in 2021, his 49th ranger year at Yellowstone, he invited me to a conference center in the Tetons where he was scheduled to “give a talk” to a gathering of staff from various Salvation Army summer nature camps.

With dinner tables cleared, the camp staff settled in for a lecture on ecosystems, a lecture that never happened. Instead, Harlan asked 12 volunteers to come forward and hold a placard with the name of an animal printed large on it. BEAVER, BEAR, ELK, WOLF, BUTTERFLY, BISON, DEER, MOUSE, GROUND SQUIRREL, COYOTE, RAVEN. Right away, the audience became participants. Harlan’s passion for the subject was contagious. What was he up to? Harlan asked the WOLF cardholder to step back. What happens to the ecosystem when the WOLF is eliminated? The volunteers began to puzzle this out. The audience pitched in. Someone got it—the ELK population explodes. How does that affect the Yellowstone ecosystem? Someone got it—the ELK eat all the willows along the streams. Ecological impact? On whom? After some ruminations, TROUT and BEAVER. And so on, until wolves were reintroduced, all the cards played, and the broken ecological connections mended. Harlan only asked questions and amplified answers. Everyone was treated with respect and affirmation. The camp staff explored ecological connections and discovered the consequences of disruption and repair on their own.

I sat in awe, watching a master teacher remove all egocentricity from teaching and gently guide a diverse group of people in learning important ecological and stewardship principles for themselves that they will not soon forget.

When I asked Harlan whether he considered himself a teacher at Yellowstone as well as at Lynden Christian High, he responded: “One of the biggest reasons I have enjoyed my work in Yellowstone each summer is because it complements my teaching. I do consider myself a teacher in Yellowstone because I see my role as someone who is trying to educate our park visitors about the importance of “wild lands” and to instill in them a love and appreciation for the natural environment. That is one of my main goals in the classroom as well. We take care of what we ap preciate, and one way to accomplish that is to better understand

Before us, lowland forests ended only at the water or opened out to clearings where loose soil could not hold its rain. Fire swept the openings clear, licked the dry and jointed grasses up, burned the seedling fir. Deep camas bulbs survived to sprout, bloom blue, then go, puckering in late May to seed.

The bunched grass called Festuca (Latin for straw, a mere nothing) still arrays itself in knots, provides its browse and seeds –first to feed the voles, then through these –hawks’ eyes and coyote’s sure, light lope.

the complexity of life. I am very passionate about stewardship and will seek any forum or setting to promote it, whether in my classroom or in Yellowstone.”

Now more than ever, humanity’s most important task is conservation—protecting and enhancing ecological systems and biodiversity. People can travel many paths to come to this challenge. Harlen’s life beautifully illustrates one of those paths.

Those of us who ride bikes are a big and diverse community. Some of us ride for fun, fitness, and adventure. Others bike for transportation—commuting across cities and towns to reach their jobs, schools, or friends.

Bicycles are magical machines. They propel us overland more efficiently than any other mechanism of human transport. They extend our horizons, allowing us to harness gravity and momentum to travel further and faster. They are also utilitarian workhorses that help us get work done without the pollution, aggravation, and high cost of driving.