African Statistical Journal Journal africain de statistiques

African Statistical Journal / Journal africain de statistiques

AN

NT

F

ENT

FO

S ND

AF RIC

P LO AIN DE DEVE

2233 2820

Volume 20 – February / février 2018

© AfDB/BAD, 2018 – Statistics Department / Département des statistiques Complex for Economic Governance & Knowledge Management/ Complexe de la gouvernance économique et de la gestion du savoir African Development Bank Group / Groupe de la Banque africaine de développement Avenue Joseph Anoma 01 BP 1387 Abidjan 01 Côte d’Ivoire Tel: (+225) 20 26 42 43 Internet: http://www.afdb.org Email: ASJ-Statistics@afdb.org ISSN : 2233-2820

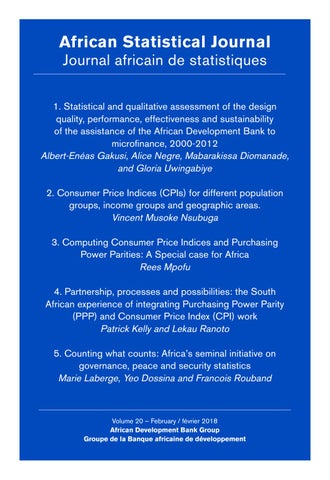

2. Consumer Price Indices (CPIs) for different population groups, income groups and geographic areas. Vincent Musoke Nsubuga 3. Computing Consumer Price Indices and Purchasing Power Parities: A Special case for Africa Rees Mpofu 4. Partnership, processes and possibilities: the South African experience of integrating Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and Consumer Price Index (CPI) work Patrick Kelly and Lekau Ranoto

D

AF

RI

C

ELOPME

PE M

O

DEV

UN

B A N QU EA F

E DE DEV EL

ENT EM PP

IN CA RI

1. Statistical and qualitative assessment of the design quality, performance, effectiveness and sustainability of the assistance of the African Development Bank to microfinance, 2000-2012 Albert-Enéas Gakusi, Alice Negre, Mabarakissa Diomanade, and Gloria Uwingabiye

5. Counting what counts: Africa’s seminal initiative on governance, peace and security statistics Marie Laberge, Yeo Dossina and Francois Rouband

Volume 20 – February / février 2018 African Development Bank Group Groupe de la Banque africaine de développement