THE HISTORIC PRESERVATION ISSUE

• Philly’s future depends on its past

• New arguments for old buildings

• Preservation without gentrification

SPRING 2024

THE BEAUTY OF NATURAL STONE WITH ADDED BENEFITS

CHAPEL STONE® MASONRY WALL

www.hanoverpavers.com

Chapel Stone® Masonry Wall is a versatile and attractive option for designers seeking the esthetic appeal of natural stone with added benefits. With a library of over 3,800 custom colors, several finishes and various height and length options, the designer’s creative vision becomes a beauitful reality.

GCCS1005 SPLIT

GCCS1006 SPLIT

GCM1008 SPLIT/TUMBLED

Canyon Blend Split/Tumbled with Pitched Faces; Shown with Reconstructed Stone™ Wall Panels and Watertables

FEATURES 10 THE PAST IS PROLOGUE Philadelphia’s historic preservation movement looks to the future By Harris M. Steinberg, FAIA, and Dominique Hawkins, FAIA 14 HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND GENTRIFICATION Spotlighting the individual experience during urban renewal in Society Hill By Francesca Russello Ammon 18 A NEW ARGUMENT FOR OLD BUILDINGS In a thriving city, preservation and affordability can go hand-in-hand By Amy Lambert and George Poulin AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 1 SPRING 2024 IN THIS ISSUE , we look at the current state of historic preservation in Philadelphia. DEPARTMENTS 7 EDITORS’ LETTER 8 UP CLOSE 22 OPINION 24 DESIGN PROFILES ON THE COVER Italianate house in the proposed Spruce Hill historic district PHOTO: AMY LAMBERT CONTEXT is published by A Chapter of the American Institute of Architects 1218 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-569-3186, www.aiaphiladelphia.com. The opinions expressed in this — or the representations made by advertisers, including copyrights and warranties, are not those of the editorial staff, publisher, AIA Philadelphia, or AIA Philadelphia’s Board of Directors. All rights reserved. Reproduction in part or whole without written permission is strictly prohibited. Postmaster: send change of address to AIA Philadelphia, 1218 Arch Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Published MARCH 2024 Suggestions? Comments? Questions? Tell us what you think about the latest issue of CONTEXT magazine by emailing context@aiaphila.org. A member of the CONTEXT editorial committee will be sure to get back to you. THE HISTORIC PRESERVATION ISSUE Philly’s future depends on its past New arguments for old buildings Preservation without gentrification

2 FALL 2023 | context | AIA Philadelphia LEGAL COUNSEL TO THE DESIGN COMMUNITY RICHARD J. DAVIES, ESQUIRE, HON. AIA. KEVIN J. DMOCHOWSKY, ESQUIRE VITTORIA D. GREENE, ESQUIRE Construction, commercial, and personal injury litigation Contract preparation and review, consultation and risk management Professional and business licensure requirements and compliance Business transactions, dispute resolution, and employment practices BERWYN, PA 610.277.2400 JERSEY CITY, NJ 201.433.0778 MILBER MAKRIS PLOUSADIS & SEIDEN, LLP MILBERMAKRIS.COM

www.beamltd.com ARCH RESOURCES, LLC. Peter Martindell, CSI Architectural Representative 29 Mainland Rd • Harleysville, PA 19438 Phone: 267-500-2142 Fax: 215-256-6591 peter@archres-inc.com https://archres-inc.com Washroom Equipment Since 1908 Arch Resources Bobrick_NOVA 4/13/2021 10:58 AM Page 1 118 Burlington Road, Bordentown, NJ www.churchbrick.com 609.298.0090

2024 BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Brian Smiley, AIA, CDT, LEED BD+C, President

Danielle DiLeo Kim, AIA, President-Elect

Rob Fleming, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, Past President

Robert Shuman, AIA, LEED AP, Treasurer

Fátima Olivieri-Martínez, AIA, Secretary

David Hincher, AIA, LEED BD+C, Director of Sustainability + Preservation

Phil Burkett, AIA, WELL AP, LEED AP NCARB, Director of Firm Culture + Prosperity

Kevin Malawski, AIA, LEED AP, Director of Advocacy

Erick Oskey, AIA, Director of Technology + Innovation

Ximena Valle, AIA, LEED AP, Director of Design

Fauzia Sadiq Garcia, RA, Director of Education

Timothy A. Kerner, AIA, Director of Professional Development

Michael Johns, FAIA, NOMA, LEED AP, Director of Equitable Communities

Katie Broh, AIA, Director of Strategic Engagement

Kenneth Johnson, Esq., MCP, AIA, NOMA, PhilaNOMA Representative

Danielle Fleischmann, AIA, At-Large Director

Michael Penzel, Assoc. AIA, At-Large Director

Andrew Ferrarelli, AIA, At-Large Director

Luka Lakuriqi, Assoc. AIA SEED,Director of Philadelphia Emerging Architects

Mitchell Schools, Assoc. AIA, Director of Philadelphia Emerging Architects

Scott Compton, AIA, NCARB, LEED AP, AIA PA Representative

Tya Winn, NOMA, LEED Green Associate, SEED, Director of Equity, Diversity + Inclusion and Public Member

Rebecca Johnson, Executive Director

CONTEXT EDITORIAL BOARD

CO-CHAIRS

Timothy Kerner, AIA, Terra Studio

Harris M. Steinberg, FAIA, Drexel University

Todd Woodward, AIA, SMP Architects

BOARD MEMBERS

David Brownlee, Ph.D., FSAH, University of Pennsylvania

Julie Bush, ASLA, Ground Reconsidered

Clifton Fordham, RA, Temple University

Fauzia Sadiq Garcia, RA, Temple University

Milton Lau, AIA, BLT Architects – a Perkins Eastman Studio

Jeff Pastva, AIA Scannapieco Development Corporation

Dana Rice, AIA, CICADA Architecture Planning

Eli Storch, AIA, LRK

Franca Trubiano, PhD, University of Pennsylvania

David Zaiser, AIA, HDR

STAFF

Rebecca Johnson, AIA Philadelphia Executive Director

Jody Canford, Advertising Manager, jody@aiaphila.org

Lee Stabert, Managing Editor

Courtney Edwards, Marketing Consultant

Anne Bigler, Design Consultant, annebiglerdesign.com

Rediscover the Many Benefits of Concrete Block. YOUR LOCAL CONCRETE PRODUCTS GROUP PRODUCER: resources.concreteproductsgroup.com Single Wythe Concrete Masonry is not only innovative, it’s also fire safe, affordable and beautiful. Visit our online Design Resource Center for the very latest in masonry design information - videos, BIM resources, design notes, and CAD and Revit® tools.

EVERY ADVENTURE BEGINS WITH PLAY General recreation, inc. • www.Generalrecreationinc.com • (610) 353-3332

Long spans up to 58 feet emphasize exposed structure architecture. The acoustic option can significantly reduce noise while the unobstructed panels reflect sunlight from skylights and clerestory windows. A high recycled content contributes to LEED® certification. Contact EPIC Metals for your next project. 877-696-3742 epicmetals.com Long-Spanning Roof and Floor Deck Ceiling Systems Wideck ® Product: WP600A, Natacoat® Dulles South Recreation and Community Center South Riding, Virginia Architect: HGA Washington, DC

JULIE BUSH, ASLA Principal of Ground Reconsidered CONTEXT Editor

DAVID B. BROWNLEE, FSAH Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor Emeritus of the History of Art, University of Pennsylvania

JULIE BUSH, ASLA Principal of Ground Reconsidered CONTEXT Editor

DAVID B. BROWNLEE, FSAH Shapiro-Weitzenhoffer Professor Emeritus of the History of Art, University of Pennsylvania

THE FUTURE OF THE PAST

It’s time to survey what’s been happening recently in historic preservation — and look forward. In Jim Kenney’s two terms as mayor, we saw some of the good, the bad, the not-sogood, and the not-so-bad in managing Philadelphia’s enormous inventory of older buildings. This is our city’s most valuable material asset, attracting visitors, providing economically and environmentally responsible places for Philadelphians to live and work, and defining our distinctive neighborhoods. Mayor Cherelle Parker has the opportunity to move the needle firmly into the “good” zone.

As a city councilman, Kenney went public with his anger at the mutilation of the former B’nai Reuben synagogue in Queen Village. He campaigned for mayor with a pledge to protect more historic buildings through designation. But in 2016, his first year in office, 400 demolition permits were granted, including one for the iconic group of nineteenth-century buildings on Jewelers Row. The National Trust for Historic Preservation was even petitioned (unsuccessfully) to put the entire city on its “endangered” list.

Then things improved a little. In 2017, Mayor Kenney assembled a large Historic Preservation Task Force. In their 2019 report, they managed to thread the needle, recommending a balanced program of regulations and incentives, and presenting a good deal of innovative thinking about seemingly intractable problems. Not enough of their recommendations have been put into effect, which cannot be entirely blamed on COVID. Most of the items that require spending are in limbo, and the huge, foundational work of building an inventory of all our historic resources will take years to complete.

Fortunately, during this period, the Historical Commission was given more staffing and urged into action. There are now 26% more buildings on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, many of them in 24 new districts. There has been a welcome emphasis on protecting sites associated with the life and work of Black Philadelphians.

In this issue of CONTEXT, it’s time to survey what’s been accomplished and provide some background for charting our next steps.

We begin with JoAnn Greco’s profile of the remarkable Paul Steinke, who has steered the Preservation Alliance, Philadelphia’s principal advocate for historic preservation, to a position of greater strength and prominence.

Then we have a report on the work that has been done to implement the recommendations of the mayor’s Historic Preservation Task Force. It was penned by the Task Force’s chair and vice chair, Harris Steinberg and Dominique Hawkins, who also outline what remains to be done.

Three additional essays tackle some of the knottiest problems in historic preservation and dispel some of the most persistent misunderstandings. Francesca Russello Ammon tells a new story about the creation of Society Hill, describing the provisions that were made to limit gentrification and enable some of the original, moderate-income residents to remain. In another piece, Amy Lambert and George Poulin argue that older buildings provide some of the best opportunities for creating affordable housing. Finally, Julie Bush chronicles the efforts of her Spruce Hill neighborhood to secure designation. She details how the current uptick in creating historic districts is the product of a powerful grassroots effort to use the protections afforded by historic preservation to promote stable communities.

Historic preservation has been around for as long as some of the buildings that we now need to protect, but the authors published here show that we still have a lot to learn.

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 7

LETTER

CONTEXT Editor EDITORS’

UP CLOSE

PAUL STEINKE

FROM REMAKING CENTER CITY TO REVAMPING READING TERMINAL MARKET, THIS LIFELONG PHILADELPHIAN’S FINGERPRINTS ARE ALL OVER OUR LOCAL INSTITUTIONS. NOW HE’S TURNING AN EYE TOWARDS HISTORIC PRESERVATION ON A GRANDER SCALE.

BY JOANN GRECO

Growing up in the Burholme section of Northeast Philadelphia, Paul Steinke was intrigued by the idea of place at an early age.

“I’d ask my father to take me to the end of streets,” he remembers. “I wanted to see what was at the end of Cottman Avenue, of Castor Avenue.” He built “little cities with little blocks, making street lights and scribbling stop signs in my terrible 6-year-old old handwriting.” He grilled his grandmother, who was born in 1900, teasing out her childhood memories about the factory districts in Kensington where she had lived.

These days Steinke lives in Logan Square with his husband David Ade, an architect. He’s been executive director of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia for nearly eight years. A quick scan of his resume — which includes stints at the Center City District, the University City District and Reading Terminal Market along with a run for City Council — illustrates that his youthful passion for Philadelphia has morphed into a long engagement with the day-to-day life of the city.

“I’m obsessed with who’s running what and what kind of job they’re doing,” he says. “What are the problems facing the city? What are its strengths and how can we leverage them?”

Still, the 60-year-old Steinke concedes that his career path was not linear. A positive experience in a Penn State economics course led him to choose the field as his major. The practicality of that decision was cemented when he graduated and quickly found a position at an economic forecasting firm. His financial aptitude and civic enthusiasm soon found their perfect match at Central

Philadelphia Development Corporation, where, working as a data analyst, he joined a very small team looking to launch a special services district. In March 1991, the Center City District was introduced.

“Our goal was to help the area rise above the challenges that had plagued Center City the decade before,” he says. He’d stay there for seven years, rising to director of finance, before leaving to head a nascent organization, the University City District (UCD).

In 1996 to be exact, two like-minded organizations, the Preservation Coalition of Greater Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Historic Preservation Corporation, merged to form the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia. Steinke ended up on its board — the beginning of a beautiful relationship. After four years at UCD, he moved on to run Reading Terminal Market, which had undergone a remarkable revitalization in the early ’90s.

“It’s clearly a civic icon — a top destination for anyone, resident or visitor, who wants to get to know Philadelphia,” explains Steinke. “I have childhood memories of going there with my dad and, in the early days of the Center City District, our offices were a few blocks away. It was a frequent lunch stop for us. It’s got a great preservation story behind it, and it was a real triumph to establish guidelines to keep it unique.”

In 2014, after 13 years, Steinke left the market to run for City Councilperson At Large.

“It was always in the back of my mind as something that I might want to do,” he says. “I thought the time was right to leverage the visibility I had achieved into an elected position where I could do more to help my city.”

He didn’t win, but when Caroline Boyce stepped down as executive director of the Preservation Alliance in 2016, Steinke was well-placed to move from his lengthy behind-the-scenes association with the organization to center stage.

He assumed the helm at a time when the city was experiencing national accolades, a growing downtown population, rising skyscrapers, and gentrification everywhere. The Alliance was in need of a pivot.

“When it was formed in the middle of the ’90s, a lot of prominent buildings — like the Naval Home, Fairmount Waterworks, and the Victory Building — were sitting vacant,” he recalls. “The Alliance and others successfully brokered workable solutions to

8 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

save them from being demolished so they could re-open for new uses. Today’s challenge is that Philadelphia, the pandemic notwithstanding, is growing again. We need to recognize and appreciate that two-thirds of our buildings were erected before World War II.

“One way to accomplish that, I think, is to pursue the sustainability objective,” he continues. “Preservation by its very definition values embodied energy, not wasting building materials, and finding new ways to use historic buildings.”

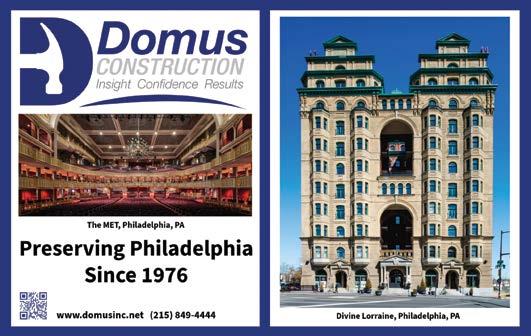

He lauds the major redevelopment efforts at the Divine Lorraine, Metropolitan Opera House, and Bok Technical High School

— all re-vamped within the last decade — as successful re-uses of large institutional buildings.

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing. Steinke acknowledges that preservation advocates have sometimes had to settle for creative compromises. For example, on the 1900 block of Sansom Street, three buildings languished for decades in the wake of a fire, until one was sacrificed to erect a high-end condo building, while the other two were restored to accommodate affordable housing units. (It was a short-lived victory, however, since the developers eventually decided that one of the two remaining structures — the beloved Rittenhouse Coffee Shop — would indeed have to go, save for its reconstructed facade, because of structural weaknesses.)

Still, the Philadelphia preservation arena is “changing slowly but steadily for the better,” he argues. “We’re catching up to other big cities. In the past six years we’ve increased the numbers of properties on the register by more than 25 percent, and we’ve added 25 more historic districts.”

Steinke sees promise in the neighborhood-focused administration of the city’s newly-installed mayor, Cherelle Parker.

“Many people think of preservation as saving old buildings in wealthy neighborhoods but they are also found in poor and working-class areas,” he says. “Whether it’s by fixing up rowhouses or converting former schools and factories to apartments, they provide opportunity for newly-created affordable housing. Look at neighborhoods that were languishing thirty or forty years ago and have rebounded. We’ve seen a sea change in neighborhoods like Brewerytown, Fishtown, and parts of South and West Philadelphia, especially when historic preservation has been embraced as a strategy.”

To stay competitive, Philadelphia needs to complete a citywide survey of historic and cultural resources.

“It’s something that many other historic cities have long since accomplished,” he explains. “Identifying, preserving and maintaining our enviable stock of historic buildings and streetscapes will only add to the appeal of our city as a place where people want to live and raise their families. It’s consistent with our goals of being a walkable city, a sustainable city, a diverse and equitable city. Preservation checks a lot of the boxes.”

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 9

JoAnn Greco is a Philadelphia-based journalist who frequently writes about the built environment.

PHOTO: PRESERVATION ALLIANCE

Paul Steinke

THE PAST IS PROLOGUE

PHILADELPHIA’S HISTORIC PRESERVATION MOVEMENT CELEBRATES ITS SUCCESSES WHILE LOOKING TOWARDS THE FUTURE

BY HARRIS M. STEINBERG, FAIA, AND DOMINIQUE HAWKINS, FAIA

PHOTOS: DAVID BROWNLEE, TOP; CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT, RIGHT

Jewelers Row in 2024, after its 2017 demolition [below]. A clip from the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 2017 [lower right]. A public task force meeting at Independence Visitors Center, October 3, 2017 [bottom].

PHOTOS: DAVID BROWNLEE, TOP; CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT, RIGHT

Jewelers Row in 2024, after its 2017 demolition [below]. A clip from the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 2017 [lower right]. A public task force meeting at Independence Visitors Center, October 3, 2017 [bottom].

The Philadelphia preservation community was on high alert.

It was the fall of 2016. Toll Brothers had successfully pulled an as-of-right demolition permit for five buildings on the famed Jewelers Row on the 700 block of Samson Street. In its place, they planned a towering 29-story luxury residential building.

Jewelers Row, a singular planned residential strip dating from 1799, is a Philadelphia icon and the oldest diamond district in the U.S. But it was not historically protected by the adjoining Society Hill or Old Philadelphia historic districts. To further complicate things, existing site zoning encouraged density and height in this area of the city. A battle royale played out across the preservation community and within the press, but there was nothing that could be done to rectify the situation.

There was a silver lining to this dust-up: the creation of the Mayor’s Task Force on Historic Preservation.

In April 2017, Philadelphia Mayor James Kenney convened 33 experts in law, development, architecture, and historic preservation, along with community leaders and others. We were honored to be among the membership of this diverse and engaged group. He charged us with developing a set of actionable recommendations that could strengthen preservation in Philadelphia while balancing the need for development. The Task Force was supported by a grant from the William Penn Foundation, with additional support from the National Trust on Historic Preservation.

The Task Force met regularly beginning in July 2017 and worked through late-2018, educating itself, learning about best practices, and analyzing how Philadelphia stacked up to

peer cities. Working in subcommittees focused on surveying historic resources, regulatory control, financial incentives, and education and outreach, the Task Force developed a series of overarching recommendations that incentivized the twin goals of preservation and development. The goal was for this work to be embraced by a wide range of stakeholders from die-hard preservationists to for-profit developers.

THE TASK FORCE SUBMITTED ITS FINAL REPORT TO THE KENNY ADMINISTRATION IN APRIL 2019.

Almost seven years later, it’s time to take stock and reflect on the next steps. To that end, we called upon Martha Cross, AICP, Philadelphia City Planning Commission interim deputy director for planning and zoning under the Kenney administration, to sum up the progress made on the Task Force’s recommendation. Cross expertly staffed the Task Force, helping the group navigate the sometimes-conflicting concerns of the city government, preservation advocates, and the development community.

Cross’ report on the accomplishments of the past four years is organized according to the eight central recommendations of the Task Force. Following each is our evaluation of those accomplishments and analysis of what remains to be done — our charge to the administration of the city’s new mayor, Cherelle Parker.

1. PLAN FOR SUCCESS

The creation of an internal government Historic Preservation Policy Team

The Historic Preservation Policy Team, formed in 2019, has been actively collaborating across city departments to advance pres-

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 11

ervation goals in internal city policies.

Led by Laura Spina, the team has conducted a survey of city-owned facilities and meets regularly.

Collaboration with the City Planning Commission (PCPC) Philadelphia Historical Commission (PHC) staff now work closely with PCPC staff on outreach efforts related to neighborhood zoning and preservation, ensuring coordination, and avoiding duplicative survey efforts.

NEXT STEPS:

USE ZONING AS A TOOL TO SUPPORT PRESERVATION

The Jewelers Row demolition demonstrated the threat to historic places when zoning incentivizes new construction rather than maintaining historic structures. When developers can profit from a 29-story luxury residential building, it is difficult to convince them to preserve five- and six-story 120-year-old buildings that are of far less potential value.

2. CREATE A HISTORIC RESOURCE INVENTORY Treasure Philly! (phlpreservation.org)

An ongoing citywide historic and cultural resources survey plan, known as Treasure Philly!, is being piloted in neighborhoods surrounding the Broad Street, Germantown Avenue, and Erie Avenue intersection. A write up is expected to run in Planning Magazine this winter. Arches implementation

The Arches platform, a state-of-the-art open-source geospatial platform, designed by the Getty Conservation Institute and the World Monument’s Fund, is being implemented with funding from the state and the citywide survey project. The database is positioned to be public facing, with additional work needed for maximum public utility. Increased staffing within the Philadelphia Historical Commission

The PHC staff has grown to ten positions, including an additional historic preservation planner and a Community Initiatives Specialist (CIS), both set to enhance survey work and community outreach.

NEXT STEPS:

The city has implemented several recommendations to establish a framework for broadening Philadelphia’s historic resource inventory. The survey process is labor intensive and costly but necessary for decision-making. The development of a comprehensive inventory will be a multi-year effort requiring dedicated leadership and commitments from the mayor and City Council, and assistance from the advocacy community as well as from public, private, and nonprofit organizations, and volunteers. Emphasis should be placed on those neighborhoods that have been overlooked in the past, in order to tell the broader story of our citizens.

3. MODIFY HISTORICAL COMMISSION PROCESSES eCLIPSE

The launch of the eCLIPSE online permitting system in March 2020 has streamlined the review and approval of building permit applications, efficiently accommodating remote processes.

NEXT STEPS:

The Historical Commission review process remains opaque to many applicants. The eCLIPSE permitting system “flags” projects subject to commission review, and the implementation of online meetings during COVID has encouraged appli -

Buildings in the “Treasure Philly!” pilot project area: rowhouses on Fifteenth Street, left, and Broad Street, looking north from Erie Avenue, in 2023.

cant and public participation. But the city lacks a clear, user-friendly, illustrated guide to show applicants what is likely to be approved by the Philadelphia Historical Commission. Along with promoting public education and outreach, this will help applicants meet the permitting requirements for historic properties and understand the city’s preservation goals.

It is important to modify city policies in order to regulate substantial alterations within city-designated historic districts, but this will be more challenging. Unlike most cities, PHC’s regulatory control does not extend to vacant lots and non-contributing buildings within historic districts. New construction that is incongruous with its surroundings can erode the historic character of a neighborhood. We need to address this problem.

4. REDUCE HISTORIC BUILDING DEMOLITION & BROADEN NEIGHBORHOOD PRESERVATION

Linked regulatory control of demolition in Neighborhood Conservation Overlay (NCO) Districts to the issuance of building permits

Legislation enacted in January 2020 requires applicants in NCO districts to obtain a building permit for new construction before obtaining a demolition permit for existing buildings.

Increased historic districts and designations related to Black history

Since 2017, the PHC has increased listings in the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places by at least 26%, designated more historic districts than all previous mayoral administrations combined, and recognized more sites significant to Black and LGBTQ+ history.

New (tiered) historic districts

Over the past year, PCPC has convened meetings with an advisory committee to provide input on the new district recommendations, worked on legislation and new regulations, and is now identifying an area for piloting the new district type.

Spirit of place

As a part of a Philadelphia City Planning Commission joint workplan with the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC), staff created a robust report of how cities across the country recognize and preserve culture. Staff will work with the new administration and with the Commerce Department to identify the greatest opportunities to bring these ideas to Philadelphia.

PHILADELPHIA, DEPARTMENT OF PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT/GRACE SWEETMAN 12 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

PHOTOS: CITY OF

NEXT STEPS:

Great strides have been made in the preservation of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods. There has been a steady increase in the number of historic districts and growing recognition of sites associated with Black and LGBTQ+ history.

One of the Task Force’s greatest challenges was to identify means of encouraging the preservation of neighborhoods by disincentivizing the demolition of buildings for new development while supporting property owners who, while dismayed by the erosion of their neighborhoods’ character, lack the financial means or desire to meet the rigorous requirements of the PHC.

To address this, we need to enact the Task Force recommendations for the creation of a range of “tiered” districts with a streamlined nomination process and several levels of regulatory control. We should also adopt the recommendations for financial support for owners: basic financial incentives in districts with the least regulatory control and larger incentives in districts subject to the highest level of regulatory review. The city is in the process of identifying a pilot project to work the kinks out of the process. It would be encouraging if the pilot project were conducted in a non-traditional historic district, providing protection for an otherwise overlooked neighborhood.

5. CLARIFY THE DESIGNATION PROCESS

Additional staff resources have been added to review and author nominations.

NEXT STEPS:

Although the additional staff is relieving the nomination backlog, the historic designation process continues to be a frustration for many. There is a lack of clear guidance on the designation process and on the information that must be provided for a nomination to be deemed “complete” by the staff.

6. INCENTIVIZE HISTORIC PRESERVATION

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs)

The creation of ADUs in locally registered historic properties has been allowed, providing potential revenue that homeowners may use for building maintenance.

Changes to parking requirements in the zoning code

Parking requirements for locally registered historic properties have been eliminated upon redevelopment. Parking requirements have been reduced by 50% for expansions of existing historic properties. By-right uses for special purpose buildings

This zoning code change allows more land uses “by-right” for non-residential, locally registered historic properties.

Construction tax abatement preserved for older buildings

While the residential new construction tax abatement will be reduced by 10% each year, renovations of existing structures are still allowed the full abatement.

Tangled Title Fund

Funding from City Council’s Neighborhood Preservation Initiative has supported the Tangled Title Fund, administered by the Philadelphia Volunteers for the Indigent Program (PhillyVIP).

NEXT STEPS

The city acted quickly to implement some of the Task Force’s recommended incentives for the preservation of historic buildings, including allowing the construction of accessory dwelling units, reducing the parking requirements, and allowing by-right “special purpose” zoning for those buildings. Owners are taking advantage of these opportunities.

The city has also supported a reduction in the new construction tax abatement, which promoted demolition rather than rehabilitation, and it has made efforts to clear “tangled titles,” which often impede the preservation of older buildings.

These efforts are a commendable beginning, but if preservation is going to be prioritized and the new tiered district process made effective, additional incentives will be required to balance development pressures.

7. SUPPORT ARCHAEOLOGY

Consulting support is planned for 2024 in accordance with the State Historic Preservation Office’s request to facilitate complete Section 106 reviews in Philadelphia without state participation.

NEXT STEPS

Archaeological resources, by their nature, are unseen, and when encountered, they often dismay or confuse property owners. Providing clear information regarding likely archaeological deposits and what to do if they are encountered, and ensuring appropriate staff support remain high priorities.

8. ACTIVATE EDUCATION AND OUTREACH

Archive of minutes back to 1956

All minutes of Commission and its Committees’ meetings have been digitized and added to an online archive.

Add an archivist

The Division of Planning and Zoning is now hiring an archivist to evaluate, scan, and archive decades of paper drawings and files, making them more readily available to the public.

NEXT STEPS

There is a general lack of understanding of the current Historical Commission designation and review process, and this will only get worse as new processes are implemented. The current PHC website is utilitarian, providing basic information to facilitate the processing of designation nominations and permit review applications. Clear, accessible information is needed to dispel confusion and myths about historic preservation and educate citizens on its benefits.

LOOKING FORWARD

The city’s accomplishments fall short of addressing all of the Task Force’s recommendations, but they should be viewed within the context of the last four years. Less than a year after the release of the Task Force report, COVID-19 shifted the city’s focus to the health and well-being of its citizens. Through that lens, great strides have been made to protect the city’s historic resources.

Now, with a new mayoral administration, we have the opportunity to move the remaining Task Force recommendations to the forefront. We must continue the vital work of restraining destruction, incentivizing preservation, and increasing public awareness. And we must encourage more Philadelphian’s to participate in preservation — democratizing the stories and places that are saved in order to represent the breadth of our history and the diversity of our city’s citizens.

Harris M. Steinberg, FAIA, is the executive director of the Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation at Drexel University. Harris served as chair of the Mayor’s Task Force on Historic Preservation.

Dominique Hawkins, FAIA, is a principal in the Philadelphia firm of Preservation Design Partnerships. Dominique served as vice chair of the Mayor’s Task Force on Historic Preservation.

Martha Cross, AICP, is a Principal with MAKE Advisory Services. She was recently Interim Deputy Director of the City’s Department of Planning and Development for the Division of Planning and Zoning and staffed the Mayor’s Task Force on Historic Preservation.

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 13

HISTORIC PRESERVATION AND GENTRIFICATION

EXCEPTIONAL CASES IN THE HISTORY OF SOCIETY HILL SHOW THEY

DON’T HAVE TO GO HAND-IN-HAND

BY FRANCESCA RUSSELLO AMMON

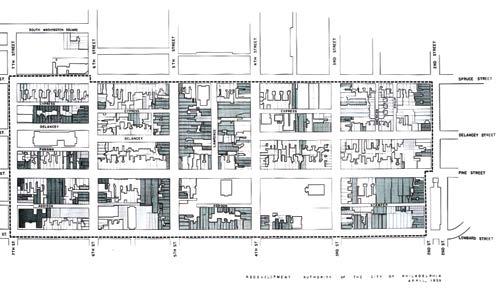

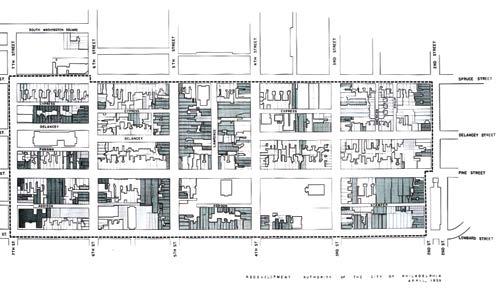

Philadelphia is home to one of the nation’s landmark urban renewal projects — and this one was grounded in historic preservation, not clearance. In Society Hill, planner Edmund Bacon, and architect and architectural historian Charles Peterson (considered one of the fathers of historic preservation) guided the modernization of a postwar neighborhood by building upon, rather than just wiping away, its physical past.1 To be sure, demolition still played a large role in the neighborhood’s remaking [Figure 1]. But clearance was not the city’s singular tool. Observers like Architectural Record called this approach the “Philadelphia Cure,” in which planners approached the city “with penicillin, not surgery.”2

While the Society Hill project took a different approach than conventional urban renewal, its social impacts were not wholly dissimilar from those realized by clearance-based projects. As a result, scholars, including geographer Neil Smith, have criticized the endeavor as an example of gentrification: the process of middle- and upper-class investment in a neighborhood that drives up real estate prices while driving out pre-existing residents.3 The percentage of adults who completed college grew from 4% to 64%, owner occupancy more than doubled, and median house prices grew from three-quarters to seven times the city average.4

Although historic preservation and gentrification sometimes go hand-in-hand, the first does not necessarily prompt the other.5 The lived example of Society Hill bolsters this distinction. Since Society Hill was not a clearance project that displaced all residents by design, existing residents were able to adopt two major strategies to remain in the neighborhood. The first was investing in restoration work required by the Redevelopment Authority, at a level that was more modest for those who wanted to maintain ownership of their properties. The second was leveraging alternative funding sources and activating the

legal system to create new low-income rental properties that were compatible with the neighborhood’s aesthetic guidelines. Although much of the neighborhood did gentrify, these exceptions disprove the claim of an inevitable causal linkage between preservation and gentrification, while also suggesting some mechanisms for proactively dissociating the two in the future.

OWNER-OCCUPANT INVESTMENTS IN RESTORATION

Several factors drove Philadelphia to its more conservation approach. The Housing Act of 1949, which initiated federal urban renewal by providing redevelopment grants covering two-thirds of the costs of acquiring and clearing land, was critically amended by the Housing Act of 1954; this later act expanded project eligibility to include rehabilitation and restoration, in addition to clearance. Philadelphia applied this second approach. Moreover, planners appreciated Philadelphia’s distinctive historic fabric, as already demonstrated by the colonial-centric preservation approach that created Independence National Historical Park, immedi-

14 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

ately north of Society Hill. If trafficked in historical currency for tourists, its nearby neighbor would do so, too, but for residents, and new pedestrian greenways helped seamlessly connect the two areas. Finally, the preservation approach avoided certain bureaucratic obstacles. Clearance-based renewal could be slow, expensive, and dependent on a few large developers. By contrast, smaller preservation projects held the promise of faster, cheaper progress, completed in partnership with a multitude of individual property owners.6

In 1959, Philadelphia joined other contemporary pioneers, including Providence, Rhode Island, and the Wooster Square neighborhood in New Haven, Connecticut, in using a preservation-based approach to urban renewal to remake the 116acre, 4-block by 7-block area that was officially designated Washington Square East.7 When Charles Peterson rebranded the neighborhood as “Society Hill,” he resurrected a historical name for the area, dating back to the Free Society of Traders business venture, which was located there during Philadelphia’s early days.

At the outset of Society Hill’s renewal, the Redevelopment Authority identified only certain properties for clearance and redevelopment. These included sites slated for future greenways; the expansion of churches, schools, or Pennsylvania Hospital; or the construction of large-scale housing projects (like Society Hill Towers). But they also designated buildings for residential rehabilitation (Fig. 1).8 Owners could retain those properties if they agreed to make the physical changes mandated by the Authority. But if they lacked the financial means and/or willingness to

take on such work, their only option was to sell the property to the Authority for fair market value. Notably, the standards for rehabilitation by existing owners were less strict than those imposed on the new owners who purchased houses that had been acquired by the Authority.9

While most Society Hill property owners did choose to sell, a sizeable number did not. Among those who stayed was Anthony Gogolski, who had purchased the house at 242 Delancey Street in 1928.10 Gogolski immigrated from Poland to Philadelphia, where he became a construction foreman. The 1950 census documented him living at 242 Delancey Street with his wife, son, two daughters, granddaughter, and two roomers — plus a family of three residing in a rear apartment.11 In August 1959, he wrote to the Redevelopment Authority about the restoration work he was completing. In removing the artificial stone facing of the building, he had discovered Flemish bond brickwork beneath, which he preserved. This façade restoration also revealed that the original windows were wider, and he was restoring those as well. In addition, Gogolski was preparing to remove the non-original mansard roof and replace it with a new pitched roof with a single dormer.12 The city issued him a permit for this work in 1961.13 Four years later, he sold the house to new owners for $22,000, a price that reflected the property’s upgrades.

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 15 MAP: REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY OF THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, WASHINGTON SQUARE EAST REDEVELOPMENT AREA, UNIT NO. 2, MAY 1, 1968

Figure 1. Acquisition, clearance, and rehabilitation plan for Washington Square East, Unit 2 (original version published in 1959).

Unrestored properties nearby were selling for one-third of that amount [Figures 2 and 3] 14

Two doors down, at 246 Delancey Street, Michael and Catherine (Schmidt) Smith would go on to spend an even longer time in their home. Michael was the son of Russian immigrants. He and his wife purchased the rowhouse for $5,300 in 1948 and soon moved in with their three young sons, a sister and brother-in-law, and a roomer.15 The Redevelopment Authority required work similar to that at their neighbors’ house, including altering the roof and restoring the front windows. In January 1960, the Historical Commission certified their property as a successful restoration.16 Nearly half a century later, Catherine, already widowed, died. In 2017, the couple’s son sold the house to a new owner for $623,000.17 Here was another family who used the opportunity of urban renewal to restore an existing property, maintain a residence there, and then sell at an increased property value.

Not everyone could choose to rehabilitate and remain in the neighborhood, even if the building they owned was not targeted for demolition. Although pre-renewal Society Hill had been a largely mixed-use neighborhood with many first-floors shops, postwar planners largely zoned out such commercial uses. Thus, the changes required of the owners of commercial properties were more than just aesthetic. Such was the case at the storefront laundry dropoff that had operated at the corner of South Fourth and Spruce Streets for a quarter century. Owner Harry Altman proposed to restore the exterior to its colonial appearance if he could maintain his business. Numerous neighbors signed a petition in support, including leading preservationist Charles Peterson, who lived just three doors down. But city planners ultimately doomed Altman’s hopes. They argued that any zoning exceptions put the whole plan at risk. Since Altman resided above the store, he lost both his livelihood and his residence as a result — displaced not by historic preservation, but rather by prevailing wisdom about zoning.18

ADVOCATING FOR LOW-INCOME RENTAL HOUSING

Clearance-based urban renewal uniformly displaced both owners and renters. For owners, the historic preservation approach taken in Society Hill did not necessarily require even their temporary relocation, and they had a choice that those faced with clearance did not. Renters, by contrast, had little control over whether they would stay or go. While former rental residents could potentially move into the new housing constructed in the wake of demolition, in practice, they could rarely afford to do so. And if their landlord opted to sell a building not slated for demolition, as many did, renters had to relocate, albeit with relocation assistance and the payment of modest moving expenses by the Redevelopment Authority. In 1950, fewer than 20% of all dwelling units in Society Hill were owner-occupied, making the plight of the renter a common one [Figures 4 and 5] 19

While the largest group of pre-renewal renters in Society Hill were Eastern European immigrants and their descendants (like Golgoski and Smith), a concentration of African Americans resided in the neighborhood’s southwest corner. This area overlapped with Philadelphia’s former Seventh Ward, the historic home of much of the city’s Black community. Roughly 20% of Society Hill’s pre-renewal residents were Black.20 On the north side of the 600 Block of Lombard Street, the Octavia Hill Association (OHA) owned and rented twelve rowhouses. The occupants were of various races and all were low-income. The OHA is a Philadelphia charitable organization that has provided low-cost housing, while earning only a modest dividend, since the late 19th century. In 1971, when the organization determined that it could not afford to meet the rehabilitation demands of the Redevelopment Authority while renting to low-income residents, it informed the roughly twenty households living on Lombard Street that they would have to leave. Within two years, these residents had been evicted.21

Seven of the households, six of which were Black, protested displacement. One of their leaders was Dorothy Miller, a Black crossing guard for the neighborhood public school whose parents had grown up in the area. Following her eviction, she was relocated to Washington Square West. As she told a reporter from the Inquirer, “It’s nice here, but I want to go back. That’s home. That’s where my roots are.”22 Miller and her neighbors soon gained the support of members of the Society Hill Civic Association, whose then-leaders were urban-renewal era arrivals in the neighborhood who had purchased and restored their own rowhouses. This alliance created Benezet Court, Inc. (named for Anthony Benezet, an early Philadelphia abolitionist), which planned to use Section 236 financing to develop new low-income housing on vacant parcels in the immediate area. Opposition came in large part from longer-term residents of the neighborhood, who lived close to the proposed sites and feared that low-income housing would threaten their property values. But while neighbors argued at heated Civic Association meetings, Miller and her allies partnered with Community Legal Services to bring the dispute to court, where

16 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

Figure 2. 242-246 Delancey Street, 1959, prior to restoration, above.

Figure 3. 242 Delancey Street, 1961, after restoration, right.

PHOTOS: PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENT OF RECORDS, PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION

they eventually prevailed. In 1979, the city sold them three vacant lots for the purpose of constructing rowhouses containing 14 units of low-income housing. Miller moved into one of these units two years later, continuing her crossing guard duties into the early 1990s [Figures 4 and 5] 23

In all these examples, the number of affected residents was admittedly small. It was not typical for low-income owners to restore their properties and continue to reside in Society Hill after renewal. Neither were many lowincome renters able to remain. But by studying these exceptions to the quantitative averages and examining the details of individual experiences, we can come to appreciate the variety of past practices and the potential for future solutions that they suggest.

Housing Act of 1949, ed. Douglas R. Appler (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2023), 195-216.

Historic preservation has not always been — and need not be — synonymous with displacement. Put differently, physical and social preservation can coexist. But scaling up such possibilities requires flexibility in the scope (and also, consequently, the cost) of acceptable restoration and rehabilitation work. Further, it requires other measures to counter gentrification, whatever its causes. These measures could include tax breaks for long-term residents, loan and grant programs for maintenance and rehabilitation, and incentives for developing lower-cost rental units. These strategies all merit further investigation. But historic preservation can be a partner with any of them. With greater appreciation today that the greenest building is an existing building, there are even more reasons for contemporary planners to consider preservation-based approaches to neighborhood revitalization. In so doing, they should be mindful of the past so that the exceptions made and lessons learned in Society Hill can become the norm.

FRANCESCA RUSSELLO AMMON is associate professor of city & regional planning and historic preservation at the University of Pennsylvania. Her book, Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape, won the Lewis Mumford Prize for best book in American planning history.

CITATIONS

1. See Ammon, Preserving Society Hill, 2021, https://preservingsocietyhill.org.

2. “The Philadelphia Cure: Clearing Slums with Penicillin, Not Surgery,” Architectural Forum, April 1952.

3. Neil Smith, “Market, State and Ideology: Society Hill,” in The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (New York: Routledge, 1996), 116–35.

4. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population and Housing, 1950 and 1980, calculated based on tract and block group data.

5. See David Stanek, “Socioeconomic Neighborhood Change in Local Historic Districts of Large American Cities, 1970-2010: A Mixed Methods Approach” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2020); Caroline Cheong and Kecia Fong, “Gentrification and Conservation,” Change Over Time, vol. 8, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 2-7.

6. Stephanie R. Ryberg, “Historic Preservation’s Urban Renewal Roots: Preservation and Planning in Midcentury Philadelphia,” J ournal of Urban History 39, no. 2 (March 2013): 193–213.

7. Ammon, “Urban Renewal through Rehabilitation and Restoration,” in The Many Geographies of Urban Renewal: New Perspectives on the

8. Wright, Andrade & Amenta, “Washington Square East Urban Renewal Area Technical Report, prepared for the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Philadelphia,” May 1959.

9. Wright, Andrade & Amenta, “Standards for Rehabilitation of Existing Buildings, Washington Square East, Urban Renewal Area, Unit I,” May 1, 1959, Athenaeum of Philadelphia.

10. Ellen Crowley to Anthony F. Gogolske, Deed, August 8, 1928, book JMH 2824, page 367, City Archives of Philadelphia, accessed via Philadelphia Land Records.

11. U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Housing, 1950, enumeration district 51-127, sheet 18, accessed via Ancestry.com.

12. Anthony F. Gogolski to Clarence Alhart, August 10, 1959, Box: 200 Block of Delancey Street, south side, Folder: 242-244 Delancey Street, Philadelphia Historical Commission.

13. Anthony Gogolski, 242 Delancey Street, Zoning Permit, March 10, 1961, Box: 200 Block of Delancey Street, south side, Folder: 242 Delancey Street, Philadelphia Historical Commission.

14. Anthony F. Gogolske to Jay H. and Deen Kogan, Deed, November 5, 1965, Book CAD 586, page 454, City Archives of Philadelphia, accessed via Philadelphia Land Records.

15. Salvatore and Paula Graziano to Michael and Catherine Smith, Deed, October 14, 1948, Book CJP 2171, page 314, City Archives of Philadelphia, accessed via Philadelphia Land Records; U.S. Census of Housing, 1950, enumeration district 51-127, sheet 19, accessed via Ancestry.com.

16. Mrs. Charles J. Maurer to Mrs. Smith, January 8, 1960, Box: 200 Block of Delancey Street, south side, Folder: 246 Delancey Street, Philadelphia Historical Commission.

17. Michael A. Schmidt to Michael DiPilla, Deed, May 8, 2017, City Archives of Philadelphia, accessed via Philadox.

18. Ammon, “Picturing Preservation and Renewal: Photographs as Planning Knowledge in Society Hill, Philadelphia,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 42, no. 3 (September 2022), doi:10.1177/0739456X18815742.

19. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Housing, 1950, calculated based on tract and block group data.

20. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Housing, 1950, calculated based on tract and block group data.

21. Ammon, “Resisting Gentrification Amid Historic Preservation: Society Hill, Philadelphia, and the Fight for Low-Income Housing,” Change Over Time 8, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 8-31, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/717926.

22. Paul Taylor, “Moved Out: The Society Hill Suit,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 1977, 7–A.

23. Ammon, “Resisting Gentrification Amid Historic Preservattion;” “Obituary: Dorothy D. Miller, October 29, 1930 – April 23, 2023,”https://www.mitchumwilsonfuneralhome.com/obituaries/ dorothy-miller (accessed January 11, 2024).

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 17

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF PHILLYHISTORY.ORG, A PROJECT OF THE PHILADELPHIA DEPARTMENT OF RECORDS, TOP LEFT; FRANCESCA RUSSELLO AMMON, TOP RIGHT

Figure 4. Octavia Hill Association-owned rowhouses, 611-621 Lombard Street, in 1959, above. Figure 5. One of the three low-income housing developments, 601-603 Lombard Street, in 2018, right.

A NEW ARGUMENT FOR OLD BUILDINGS

IN A THRIVING PHILADELPHIA, PRESERVATION AND AFFORDABILITY CAN COEXIST

BY AMY LAMBERT, AIA AND GEORGE POULIN, AIA

One of the most repeated criticisms of the historic preservation movement is that preservation adversely impacts housing affordability. In an era when cities across the nation are experiencing affordable housing crises, this tension has fueled a robust debate in which the benefits of historic preservation are pitted against the necessity of affordability. Communities across the Philadelphia region are grappling with these seemingly competing priorities: the desire to preserve neighborhood character and the fundamental need to ensure access to housing. And these challenges must now be considered in the context of climate change and the concomitant imperative to conserve existing resources.

Fortunately, solutions exist. Older buildings are one of the best sources of affordable, environmentally responsible housing, and there are a variety of sources for funding their preservation and adaptation. Realizing that potential, however, requires the ability to navigate complex funding structures. In addition, expanding the economic programs to meet these needs will require political will.

Historic preservation is the discipline that was created to meet these challenges. It is a pursuit that understands that modern society and historic resources should exist in productive harmony in order to fulfill the requirements of current and future generations.1

In this endeavor, architecture and preservation naturally align in important ways — many architects actually consider themselves preservationists. One of the greatest talents of architects is problem solving, and that skill is needed to maximize the opportunities that existing buildings offer.

Preservation is resource management. As the late architect

Emanuel Kelly stated in a 2023 interview, “Preservation isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s more about identifying cultural resources that link us to our history.”2 The past is not behind us. It is very much with us and often confronts us with intriguing design challenges. How we respond reflects our values — and the values of preservationists align with those of many architects: sustainability, and economic and cultural responsibility. Our partnership, based on shared goals of transforming the built environment, is powerful.

THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF OLDER BUILDINGS

In cities all across our nation, and in Philadelphia in particular, preservationists are often pitted against pro-development advocates who see high-density new construction as the solution to our cities’ affordable housing crisis. But what we often fail to recognize is the inherent affordability of our existing housing stock [Figure 1]

Take the Spruce Hill neighborhood of Philadelphia, for example. Well known for its Victorian architecture, the neighborhood enjoys a population density more than twice the average of Philadelphia as a whole.3 The median price of a one-bedroom rental in Spruce Hill is $1,025 per month.4 These affordable units also take the form of “missing middle” housing, a type of house-scale building with multiple units located in walkable neighborhoods, just like Spruce Hill. This figure is in stark contrast to the pricing of new construction. On Chestnut Street alone, between 41st and 46th Streets, more

18 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

PHOTO: AMY LAMBERT

than 1700 units have been constructed in the past five years. In many instances, the new buildings have taken the place of the historic neighborhood fabric, such as the site of the Christ Memorial Reformed Episcopal Church at 43rd and Chestnut. The least expensive one-bedroom apartment in these newly completed buildings starts at $1,600 per month, 50% more expensive than the median rent of the neighborhood as a whole. The historic district designation of Spruce Hill, which is now under review, would usher in a community-led balance between preservation and development, and affordable housing is among the things that will be preserved.

MEETING THE COSTS

Local designation is one of the tools that can help preserve valuable older buildings, but it does not automatically come with financial relief or provide maintenance funding to keep long term residents in place. Indeed, one of the most prevalent criticisms of historic designation is the perceived financial burden it imposes on owners of historic properties. But while the reality of these burdens must be acknowledged, there are now a handful of promising programs at the national and state level that target the reactivation of older buildings, giving them opportunities for continued useful life and economic generation. In recent years, the Philadelphia Historical Commission has also been increasingly sensitive to the financial realities of repairing and maintaining historic properties.

The statewide Pennsylvania Whole-Home Repairs Program is an important resource for owners of older houses. It was established to reverse years of systemic neglect in our well-used but aging housing inventory.

One of the few Pennsylvania state programs to assist homeowners in maintaining their properties, it encourages the extended life of houses by providing a bulwark against rising maintenance and utility burdens. Especially in gentrifying neighborhoods, where housing costs can quickly soar, this additional support for homeowners and small landlords can prevent displacement and stabilize communities. This is as much about people as buildings. As State Senator Nikil Saval, who represents PA District 1, contends, “Preservation is, at its heart, a social practice that honors the sense of belonging, continuity, and stability that beats in the sacred connection between people and place. The Whole-Home Repairs Program protects this connection.”

Other states do more. Some have tax credits for the repair and rehabilitation of owner-occupied historic properties.

The Maryland Sustainable Communities Tax Credit Program offers homeowners a state income tax credit equal to 20 percent of qualified rehabilitation expenditures.5 With similar demographics and aging communities, Pennsylvania would be wise to offer the same.

[Figure 1]

4000 block of Sansom Street: “Missing middle” houses, which allow flexible and reversible single-family/multifamily conversion.

New federal initiatives are also responding to the housing crisis and the sustainability concerns of the post-COVID world. A guidebook has been released that details the efforts of twenty agencies, including the General Services Administration (GSA) and Housing and Urban Development (HUD), to reach the dual goals of affordability and low emissions. Among the newest initiatives is a program to incentivize the conversion of commercial properties into affordable housing, which was announced by the White House in October 2023.

The creative use of Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs) can provide another funding stream. LIHTCs usually prioritize the construction of new affordable housing that meets the minimum requirements. They operate not unlike Historic Tax Credits for developers. In New York State, the agency that oversees LIHTCs prioritizes projects that combine the two tax credit programs to support the reuse of existing buildings for low-income residents. This provides another response to the strawman argument that preservation is a roadblock to development or affordability.

[Figure 2]

The Beury Building, during the Rust Belt Coalition of Young Preservationists Conference, October 2019, now undergoing rehabilitation by Shift Capital with historic tax credits.

The connection between people and place is at the core of the Wolf Avenue Collective, a new model of affordable housing through community ownership in Missoula, Montana.6 When an 8-unit historic building in a National Register (NR) district was put up for sale, fears of rising rents with new ownership drove a community-led effort to turn renters into shareholders through a housing cooperative. A willing interim buyer held the land while two nonprofits — one specializing in Community Land Trusts and the other a housing lender — worked to create a community land trust with the eager residents becoming collective owners. While Missoula is a Certified Local Government, neither that designation nor the NR status were leveraged in the funding structure, but NeighborWorks Executive Director Kaia Peterson was explicit that the historic significance of the property was a factor. She stressed that the residents were driven by a belief that existing housing which has served the community for generations was a key value worth protecting. This could be a model to replicate in Philadelphia, and one where NR and CLG designations could be leveraged to encourage the affordability of existing historic housing.

TAX INCENTIVES

Philadelphia benefits from Historic Preservation Tax Credit (HPTC) programs at both the federal and state levels, which are among the best tools for the rehabilitation of older buildings. They are applicable to properties that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While inclusion on the National Register is one of our nation’s highest recognitions of historic significance, it comes with no protections against demolition or insensitive alteration. It does make developers of income-producing properties eligible for federal tax savings of 20% and for up to $500,000 in state tax credits for qualified rehabilitation expenses. Since the program’s

inception in 1976, it has leveraged $116.34 billion in private investment to preserve more than 47,000 historic properties. Federal funding has historically been the catalyst for positive and proactive development that has employed architects, improved cities, and bettered lives [Figure 2]

The HPTC has been one of the most successful incentive programs in the country, and Harrisburg’s state level program, though far smaller than those in neighboring states, provides a crucial boost to this work. The 1926 Beury Building on North Broad Street in Philadelphia received $200,000 in state tax credits in 2023, which will help to remake the long-vacant bank and office building into a hotel, led by developers Shift Capital. Kalidave LP, spearheaded by developer Guy Laren, is shepherding the 1912 Leader Theater, long hidden behind a mid-century façade on Lancaster Avenue, through a conversion. The movie palace will be transformed into a multi-floor commercial building with help from a $200,000 state tax credit, giving new economic vitality to the thoroughfare that stretches across West Philadelphia.

MM Partners LLC has also been at the forefront of developing vacant buildings throughout the city with the support of tax credits. While they may not identify as “capital P” preservationists, the tax benefits associated with the National Register designation of many of the buildings they have adapted have made their work possible. Preservation is indeed a big tent endeavor, and the advantages of working with vintage architecture are not only economic.

“Older buildings by and large tend to be of a much higher quality than anything you could ever afford to build today with higher ceilings, bigger windows, cool original details, and often reusable infrastructure,” says David Waxman, co-founder and managing partner of MM. “In addition, the history of the building typically provides a great back story for marketing purposes. These buildings aren’t cookie cutter like much of the new mid-rise multifamily projects being built here and all over the country.”

20 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

PHOTO: AMY LAMBERT (RIGHT), SARAH MARSOM (TOP)

The company’s current portfolio includes the transformation of a nineteenth century trolley barn on Haverford Avenue into loft apartments and the multifamily conversion of a former psychiatric hospital on Henry Avenue in East Falls. MM’s projects have received several Preservation Achievement Awards bestowed by the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia [Figure 3]

While historic tax credits can reactivate larger buildings, there is no obvious remedy for the estimated 50,000 vacant houses that dot our city. Sheriff’s sales have not happened in years.7 The Philadelphia Land Bank is a nearly ten-year-old attempt to streamline the redevelopment of vacant and tax-delinquent city-owned properties into productive use. Yet it has released only a fraction of its parcels, most of which are vacant land that has found its way to developers for new construction. These vacant buildings and lots reflect the legacy of redlining, which still marks our racially diverse city. They do not seem to have a hero, and they need one if we are to make the best use of these resources.

LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

As design professionals whose work investigates and shapes the built environment, we must continue to engage with our elected officials and local nonprofits to meet the demands of our communities for affordable homes in a city rich with history. Philadelphia is still beset by mistakes

made in the prior century, which we must confront in this one. Structural poverty, racist redlining, uneven public safety, and selective disinvestment will continue to weigh down the entire city. As architects, we have the skills to understand the dynamic relationship between preservation and affordability. Voting, advocacy, and the successful implementation of projects are our professional responsibility. As our nation’s most affordable and historic large city, Philadelphia can seize this moment to demonstrate that preservation and affordability are not just complementary, but intertwined.

Amy Lambert and George Poulin are both Philadelphia architects serving on the board of the University City Historical Society, a volunteer-run organization dedicated to the preservation of the history, architecture, and cultural heritage of West Philadelphia.

CITATIONS:

1. Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and Housing and Urban Development. “Affordable Housing and Historic Preservation,” 2006

2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FfZNN7s32ZY

3. https://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Spruce-Hill-Philadelphia-PA.html

4. https://issuu.com/universitycity/docs/the_state_of_university_ city_2023_web?fr=sOWE3MzU5OTQ4MjI

5. https://mht.maryland.gov/Pages/funding/tax-credits-homeowner. aspx

6. https://www.nwmt.org/wolf-avenue-collective-case-study/

7. https://www.inquirer.com/news/sheriffs-office-tax-sales-bid4assets-20231224.html

West Philadelphia Passenger Railroad Company Carhouse (1876), being converted into apartments by MM Partners, LLC.

[Figure 3]

COMMUNITY DRIVEN

HISTORIC DESIGNATION

PRESERVES THE PERSONALITY OF PHILADELPHIA’S NEIGHBORHOODS. SPRUCE HILL MAKES ITS CASE.

BY JULIE BUSH, ASLA

While some Philadelphians are debating the merits of historic preservation, neighborhoods are lining up to be designated as historic districts, aiming to protect their distinctive appearance and their communities. Spruce Hill, an area of West Philly between 38th and 46th Streets, bound by Market Street to the north and Woodland Avenue to the south, would like to be next.

A member of the Spruce Hill Community Association (SHCA) Board, the Zoning Committee, and the Historic Preservation Committee, I moved to Spruce Hill in 2003. I was drawn by the beautiful Victorian homes, set back from the sidewalk to allow for small front yards and connected porches.

As a design professional, I am pro development, but I have witnessed multiple buildings in my neighborhood being torn down by developers and replaced by bland boxes to house students. In these situations, the quality of the architecture does not matter — student residents are temporary and seem to care little about such things.

In some cases, even the ownership of the building is temporary. I have noticed a pattern: Developers buy an existing building, demolish it, build a new one, get it fully rented, and then sell it. If the quality of construction is poor, it’s on the next owner. I am tired of outside forces profiting from the destruction of the fabric of my neighborhood.

Spruce Hill has one of the largest collections of Victorian-era housing in the country and is already on the National Register of

Historic Places as part of the West Philadelphia Streetcar Suburb Historic District. However, the National Register does not shield a property from demolition. Protection requires designation by the Philadelphia Historical Commission, either as a contributing building in a historic district or an individual listing on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. The nomination of Quadrant 1 of the Spruce Hill Historic District (south of Spruce and east of 43rd Street) is currently under review by the Historical Commission. Hopefully, by the time this spring Issue of CONTEXT is published, we will have taken the first step toward being declared a historic district.

Spruce Hill also made a play for historic district designation in 1987 and in 2002. I was not involved with those efforts, but common knowledge in the neighborhood is that developers got in the ear of City Council. A false narrative was introduced: The expense of home ownership in historic districts led to population displacement and gentrification. Obviously, there are many factors that lead to gentrification, but these include the demolition of older buildings and the construction of new apartment buildings with higher rents. Historic designation actually helps to prevent that kind of gentrification.

As part of the Spruce Hill Historic District process, SHCA has led multiple public meetings. We hosted a forum in fall 2022 with Powelton Village and Overbrook Farms, neighborhoods that were both successful in recent efforts to be declared historic districts. At a panel discussion in summer 2023, concerns about the cost of home repairs in the district were raised and answered. A Philadelphia Historical Commission representative explained that the staff works alongside homeowners to figure out what they can afford while helping to maintain the architectural character of their property. There are new, more affordable products on the market that closely resemble the original materials. There is also a financial hardship provision in the preservation ordinance, which protects owners from being forced to make changes they cannot afford. Moreover, the ordinance does not compel owners to replace non-historic materials that were in place at the time of designation.

Attendees at these information sessions were also reassured that historic designation was not linked to property tax assessment and that it does not dictate use, which is governed by zoning.

As before, the Spruce Hill Historic District nomination campaign is entirely community driven. Because Spruce Hill is so large, the

22 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

OPINION

Historical Commission recommended that we divide the neighborhood into four quadrants. SHCA raised money to hire an outside consultant. They researched and photographed all of the properties in the southeast quadrant, which will be the first quadrant to be evaluated. This information is part of the nomination, which is currently being reviewed by Philadelphia Historical Commission staff. After every owner in the proposed district receives written notice, the Philadelphia Historical Commission will hold two public hearings. Finally, the Commission will vote to accept or not accept the nomination to designate the district as historic.

My understanding of the designation process and my support for it has been shaped by my participation on the Spruce Hill Zoning Committee, where we review any projects that require variances from the zoning code. These requested variances are often for use, parking, and setbacks. They are never for demolition, because no permission is needed: Demolition is currently allowed by right.

When we ask why a developer is demolishing a historic building, we often hear that the layout of the plan is not conducive to current student desires for studio apartments (not group housing) or that the cost to maintain it is too high. Since the current zoning allows demolition, all that we can do is request that they keep the existing structure, and find creative solutions to preserve and reuse it. These are simply recommendations, as they are not binding. The zoning code does not compel developers to think creatively about historic preservation, nor are there sufficient incentives for them to do so. That is why the protection offered by listing on the Register of Historic Places is so important.

Spruce Hill is not alone in our fears about the destruction of our neighborhood. Many of the 25 new historic district designations in the last six years have been community-led. Powelton Village has similar housing stock and is also near a university that generates a demand for student housing. They were successful in their community-led effort to protect their neighborhood through designation as a historic district. We hope to do the same to preserve the special character of our neighborhood.

“THE ZONING CODE DOES NOT COMPEL DEVELOPERS TO THINK CREATIVELY ABOUT HISTORIC PRESERVATION, NOR ARE THERE SUFFICIENT INCENTIVES TO INDUCE THEM TO DO SO.”

Julie Bush, ASLA is a Principal at Ground Reconsidered and a member of the Context Editorial Board

For more information on the Spruce Hill Historic District, go to this link: https://ucityhistorical.wordpress.com/spruce-hill-historic-district/

AIA Philadelphia | context | SPRING 2024 23

Interruption of the historic block on 45th Street PHOTO:

JULIE BUSH

DESIGN PROFILE

HERRINGBONE LOFTS

Stanev Potts Architects

Herringbone Lofts takes its name from the original purpose of this elegantly redeveloped building: a factory and warehouse for a 1920s men’s suit manufacturer. Before its transformation into a modern mixed-use project with 54 apartments, exceptional amenities, and ground floor commercial space, this structure sat abandoned for over 30 years. With major sections of the building deteriorated beyond repair, an adaptive reuse approach required a careful survey and evaluation of the façade and structure, and inventive techniques to harmonize the new skin and systems with the handsome industrial character of the original.

This approach is exemplified in the elevations where original brick is juxtaposed with new spandrels of folded weathering steel, redefining the building’s appearance while preserving the original façade composition. The existing steel windows—determined too corroded to repair—were replaced by modern ones designed to echo the original muntin pattern while providing

high thermal and acoustic performance.

“Salvage and reuse” was the theme for the carefully planned interior as well. Original exterior steel windows were restored for use as interior dividers in the amenity spaces. Salvaged timbers and decking were planed and reused for a variety of purposes, from stair treads to furniture tops to a herringbone patterned accent wall in the lobby.

While the historic framework provided a handsome aesthetic vocabulary, it was also challenging to ensure that the building

could deliver modern comfort, particularly regarding acoustics—a common issue with timber factory conversions. The floor/ceiling assemblies utilized a detail developed for modern heavy timber buildings: ultra-thick isolation matts combined with a thickened gypsum topping slab. This allowed the existing heart pine decking timbers to be left as exposed ceilings paired with minimalist surface-mounted lighting and exposed ductwork. These design strategies combined to create industrially spare, luxurious, and comfortable interiors ■

PROJECT: Herringbone Lofts

LOCATION: Grays Ferry, Philadelphia, PA

CLIENT: Miller Investment Management

PROJECT SIZE: 58,800 sq ft

PROJECT TEAM:

Stanev Potts Architects (Architect)

Ascent Restoration ( Facade Consultant)

Cooke Brown (Structural Engineer )

BHG Consulting ( Electrica l / Mechanical Engineer)

Reed Street Builders (General Contractor)

24 SPRING 2024 | context | AIA Philadelphia

PHOTOS: DANIEL JACKSON

DESIGN PROFILE

PROJECT: Schoolhaus

LOCATION: Newtown, PA

CLIENT: Private homeowner

PROJECT SIZE: 5,400 sq ft

PROJECT TEAM:

Gnome Architects (Design/Architect)

Poulson & Associates LLC (Structural Engineer) Hutec

Engineering (Electrical / Mechanical Engineer) Point

Builders & Design Concepts (General Contractor) Round

Three Photography (Photographer)

Mid Atlantic Timberframes (Heavy Timber Framing)

SCHOOLHAUS Gnome Architects LLC

This former 1860s schoolhouse has undergone several renovations during its conversion to a private residence. After a series of mid-century additions, it was purchased by a family who wanted to expand the home’s footprint and unify its design, while maintaining the character and materials of the original structure.

Hinged around the original stone structure, the renovation approach provides necessary updates to portions of the existing building and features a new wing of the home for additional spaces and modern amenities. The new wing is extended out from the existing gable form and separated from the stone structure via a glass connector, allowing the new and old to be expressed independently. The gable is further extended to provide cover for exterior living spaces on the first and second floors.

Integrating a modern addition with the original 1860s