19 minute read

COVER | PORTADA

COVER STORY

Advertisement

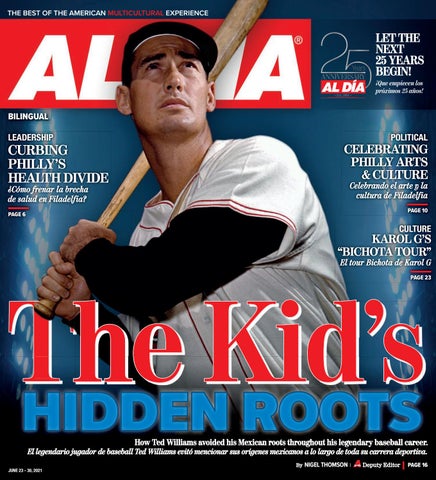

TED WILLIAMS’ HIDDEN HERITAGE

ONE OF BASEBALL’S GREATEST PLAYERS EVER ONLY MENTIONED HIS MEXICAN HERITAGE ONCE, IN A SENTENCE IN HIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

EL QUE FUE UNO DE LOS MEJORES JUGADORES DE BASEBALL DE LA HISTORIA SOLO HIZO MENCIÓN A SUS ORÍGENES LATINOS EN UNA FRASE DE SU AUTOBIOGRAFÍA.

By | Por: NIGEL THOMPSON | AL DÍA Deputy Editor

WILLIAMS’ HIDDEN HERITAGE

Ted Williams was born in 1918 to a Welsh and Irish father and a Mexican mother.

Gettyimages

Ted Williams nació en 1918 de padre galés e irlandés y madre mexicana.

ENGLISH ESPAÑOL

When looking back at the Hall of Fame baseball career of Theodore Samuel Williams, more commonly known as Ted Williams, or his plethora of nicknames — ‘The Kid,’ ‘The Splendid Splinter,’ ‘Teddy Ballgame,’ ‘The Thumper’ — most rightfully see him as one of sport’s best hitters ever.

The stats and accolades don’t lie.

In his 19-year career with the Boston Red Sox, which ran from 1939 to 1960, Williams amassed 2,654 hits, 521 home runs, 1,839 runs batted in (RBIs), and a career batting average of .344 at the plate.

All rank Williams within the top 100 of each category in MLB history, with his highest coming at number 10 in career batting average.

He is also one of only two players in MLB history with two Triple Crowns, earned when a player leads the entire league in home runs, RBIs, and batting average at a season’s end. Williams took home the crown in 1942 and 1947.

He also won the American League MVP award twice, in 1946 and 1949.

A HIDDEN IDENTITY

Al mirar atrás en la carrera de béisbol del famoso Theodore Samuel Williams, más comúnmente conocido como Ted Williams, o por su plétora de apodos: ‘The Kid’, ‘The Splendid Splinter’, ‘Teddy Ballgame’, ‘The Thumper’, la mayoría lo ven, con razón, como uno de los mejores bateadores deportivos de todos los tiempos.

Las estadísticas y los elogios no mienten.

En sus diecinueve años compitiendo con los Red Sox de Boston, entre 1939 y 1960, Williams acumuló 2.654 hits, 521 jonrones, 1.839 carreras impulsadas (RBIs) y un promedio de bateo de .344 en el plate.

Todos clasifi can a Williams dentro de los 100 mejores de cada categoría en la historia de la MLB, y su puntuación más alta es de 10 en el promedio de bateo de su carrera.

También es uno de los dos únicos jugadores en la historia de la MLB con dos Triples Coronas ( se ganan cuando un jugador lidera toda una liga en jonrones, carreras impulsadas y promedio de bateo al fi nal de una temporada), conseguidas en 1942 y 1947.

También ganó el premio MVP de la Liga Americana dos veces, en 1946 y 1949.

‘The Kid’ left more than enough history to talk about on the baseball diamond, and if he were still alive, Williams would likely be ok with that.

Off the fi eld and before he even stepped foot on one, Williams was the son of Samuel Stewart Williams and May Venzor.

His father, whose last name Ted would take, was Welsh and Irish, and his mother was Mexican-American, born to Pablo Venzor and Natalia Hernandez, hailing from Valle de Allende, Chihuahua, Mexico.

Williams’ Mexican-American heritage is something only the few writers to do deep dives on his life and career have been able to unravel.

The baseball legend himself only reserved one 44-word sentence in his 232-page 1970 autobiography, My Turn at Bat, for his own Mexican heritage.

“Her maiden name was Venzer, she was part Mexican and part French; and that’s fate for you; if I had had my mother’s maiden name, there is no doubt I would have run

UNA IDENTIDAD SECRETA

“The Kid” dejó una historia más que sufi ciente de la que hablar en el campo de béisbol, y si todavía estuviera vivo, Williams probablemente estaría de acuerdo. Fuera del campo, y antes siquiera de haber puesto el pie en uno, Williams era el hijo de Samuel Stewart Williams y May Venzor. Su padre, cuyo ape As I transcribed llido tomaría Ted, era de the tape later, I origen galés e irlandés, y su madre era mexikept hearing him coamericana, nacida de say ‘Venzor’ — not Pablo Venzor y Natalia Hernández, oriundos de

‘Venzer Valle de Allende, Chihuahua, México. La herencia mexicano-estadounidense Mientras de Williams es algo que transcribía la solo los pocos escritores que profundizaron en su cinta más tarde, vida y carrera han podiseguía oyéndolo decir “Venzor”, no do desentrañar. La leyenda del béisbol solo dedicó una frase de 44

“Venzer” palabras en su autobiografía de 232 páginas publicada en 1970, My Turn Bill Nowlin, Ted Williams: at Bat, para mencionar su The First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame herencia mexicana.

ENGLISH From pag.17|

into problems in those days, the prejudices people had in Southern California,” Williams wrote.

The sentence was arguably the first time Williams had ever publicly acknowledged his Mexican heritage — after 52 years and a Hall of Fame baseball career.

VENZER OR VENZOR?

It was also the sentence that sent Boston-based writer and baseball historian Bill Nowlin on a long journey to discover more of Williams’ hidden Mexican roots. He would go on to write an article for Boston Globe Magazine about the subject in 2002, published just a month before Williams passed away.

The journey introduces Nowlin’s book, Ted Williams: The First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame, published in 2018, the same year Williams would have turned 100 years old.

“I did a nationwide web search on the name Venzer. There were five people listed. I called them up. They didn’t know anything about having Ted Williams as a relative,” wrote Nowlin. “There was no thread for me to follow.”

More would be discovered, recounted Nowlin, after the publication of his first book on Williams, Ted Williams: A Tribute, in 1997.

His co-author on the book, Jim Prime, got an email from a man named Manuel Herrera more than a year after its release. Herrera claimed to be Williams’ cousin.

Nowlin called Herrera, and the writer finally had more thread to work with in putting the story of Williams’ Mexican heritage together.

He even came to the realization that the man self-proclaimed as “the greatest hitter who ever lived” had his own mother’s maiden name spelled wrong in his autobiography.

“It was maybe seven or eight minutes into the interview before he used the name Venzor,” Nowlin wrote about his conversation with Herrera. “As I transcribed the tape later, I kept hearing him say ‘Venzor’ — not ‘Venzer,’ which I’d always been pronouncing ‘Venz-air.’ Accent on the first syllable. Part Mexican and part French, Ted had written.”

A cross-reference with Williams’ birth certificate, and Nowlin confirmed the mistake that had stymied his research for years.

Williams amassed a number of nicknames throughout his playing career, but “The Kid” was always his favorite. Gettyimages Williams acumuló varios apodos a lo largo de su carrera como jugador, pero “The Kid” fue siempre su favorito. Gettyimages

If I had had my mother’s maiden name, there is no doubt I would have run into problems in those days, the prejudices people had in Southern

California

Ted Williams in his autobiography, My Turn at Bat

His next stops saw him make plans to go to Santa Barbara, California and El Paso, Texas to potentially meet more members of Williams’ extended Mexican family.

Both cities, along with San Diego, are vital locations in the early life of Williams and that of his family. El Paso is where his mother spent the earliest years of her life, and Santa Barbara is where her family would settle.

San Diego is where Williams’ parents, May and Samuel, would settle with him and his brother Danny.

After Nowlin, the next writer to take on Williams’ Mexican heritage in a biography was longtime Boston Globe journalist and editor, Ben Bradlee Jr. His work on Williams, The Kid, The Immortal Life of Ted Williams, came out in 2013, and went on to become a New York Times best seller.

ASHAMED OF HIS FAMILY

The first chapter of Bradlee Jr.’s book is titled “Shame.”

It starts by laying out Williams’ embarrassment with his own family. Whether it be his mother, “the Salvation Army devotee and fixture of Depression-era San Diego.”

His father, “who ran a cheesy downtown photo studio that catered to San Diego’s sailors and their floozies.”

Or his younger brother, “a gun-toting petty miscreant always one step ahead of the law.”

“Ted was always ashamed of his upbringing,” reads the first sentence of Bradlee Jr.’s book.

Regardless, his Mexican uncle, Saul Venzor, is credited by many biographers (including Bradlee Jr.) as being the one to first introduce Williams to baseball.

ASHAMED OF HIS HERITAGE

The resentment for his family extended to his Mexican heritage, which he saw throughout his playing career as something that would block him from playing on baseball’s biggest stage.

“Ted didn’t want anyone to know he was part Mexican,” Bradlee Jr. quoted Williams’ longtime friend, Al Cassidy.

Instead, due to his fair complexion, Williams would identify as “Basco,” hailing from the Basque region of Spain. The lie was kept up even by his closest family member, Sarah Venzor Diaz, when interviewed by Bradlee Jr. for his book.

FULL NAME Theodore Samuel Williams

BORN San Diego, California August 30, 1918

NATIONALITY AMERICAN

DEATH Inverness, Florida July 5, 2002

POSITION Left fielder

“We have no Mexican heritage in our family. We are Basque,” she said.

Williams’ rookie season in 1939 was eight years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the owner of Williams’ Red Sox, Tom Yawkey, oversaw the last team to add a Black player to its roster.

As is mentioned by many writers and family members interviewed for PBS’s Ted Williams: “The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived,” Williams was also acutely aware of the prejudice faced by Mexicans in Southern California when he was growing up.

THE PROBLEM WITH PASSING

In response, he passed as white, even if he wasn’t the first Latino or even Mexican in the majors. The latter distinction goes to Mel Almada, who debuted for Williams’ Red Sox in 1933, six years before “The Kid” began his own career.

Williams’ passing has been a point of contention for many when considering him one of the best Latinos to ever grace a baseball diamond. The Hispanic Heritage Hall of Fame inducted him as part of its 2002 class, but Major League Baseball left him off its own list of 60 “Latino Legends” in 2005.

Williams was afraid his Mexican heritage would bar him from playing in the majors. Gettyimages Williams temía que su herencia mexicana le impidiera jugar en las grandes ligas. Gettyimages

Illinois Sports History Professor Adrian Burgos Jr., has also come out against “retroactively inserting Williams” into the history of Latinos in baseball because he did not identify as one.

For support, Burgos Jr. described the unique experiences of Latinos that en-

tered the MLB before Robinson that Williams avoided with his passing.

“These Latinos gained entry, for the most part, not because they were white but because they were not definitively Black,” he wrote for Sporting News.

He pointed to players like Cuban-born Miguel Angel Gonzalez, whose name was not only Anglicized to “Mike,” but his accent also became the subject of ridicule.

There were also the experiences of Latinos in the farm system of the Washington Senators in the South during the 30s and 40s.

“Their encounters in Jim Crow towns and around the major league circuit taught them that while they were not Black, most certainly did not see them as fellow ‘Caucasians’ or white,” wrote Burgos Jr.

Sarah Venzor Diaz

SUPPORT FOR BLACK PLAYERS

The only thing he gives Williams credit for is publicly supporting the induction of Black players into the MLB Hall of Fame during his 1966 Hall of Fame speech.

“I hope that someday, the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson can… be added to the symbol of the great Negro League players that are not here only because they were not given a chance,” Williams told the crowd July 25, 1966.

Five years later, Paige joined Williams in the Hall as the first Negro League player inducted.

While ‘The Kid’ can’t be given all the credit for the MLB finally inducting Black players into its Hall, his speech started the discussion. In the same way, Williams’ biographers have started the discussion about his own hidden Latino identity. z

ESPAÑOL Viene pag. 17 |

“Su apellido de soltera era Venzer, era en parte mexicana y en parte francesa; y ese eso iba a marcar mi destino;“si hubiera llevado el apellido de soltera de mi madre, no hay duda de que habría tenido problemas, dados los prejuicios que tenía la gente en el sur de California en esa época”, escribió Williams.

Podría decirse que con esa frase Williams reconocía por primera vez públicamente su herencia mexicana, después de 52 años y una carrera de béisbol enmarcada en el Salón de la Fama.

VENZER O VENZOR

También fue la frase que motivó al escritor e historiador del béisbol de Boston Bill Nowlin a realizar un largo viaje para descubrir más sobre las raíces mexicanas secretas de Williams. Acabaría publicando un artículo sobre el tema para Boston Globe Magazine en 2002, solo un mes antes de que Williams falleciera.

El viaje es un preámbulo del libro de Nowlin, Ted Williams: The First Latino in the Baseball Hall of Fame, publicado en 2018, el mismo año en que Williams habría cumplido 100 años.

“Hice una búsqueda en Internet a nivel nacional sobre el nombre Venzer. Había cinco personas en la lista. Los llamé. No sabían nada sobre tener a Ted Williams como pariente ”, escribió Nowlin. “No había ningún hilo que pudiera seguir”.

Se descubriría mucho más, relata Nowlin, después de la publicación de su primer libro sobre Williams, Ted Williams: A Tribute, en 1997.

Un año después de su publicación, el coautor del libro, Jim Prime, recibió un correo electrónico de un hombre llamado Manuel Herrera que afirmaba ser el primo de Williams.

Nowlin llamó a Herrera, y de esta manera encontró más hilo con el que trabajar para armar la historia de la herencia mexicana de Williams.

Incluso se dio cuenta de que el hombre autoproclamado como “el mejor bateador que jamás haya vivido” tenía el apellido de soltera de su madre mal escrito en su autobiografía.

“Quizás pasaron siete u ocho minutos de la entrevista antes de que mencionara el apellido Venzor”, escribió Nowlin sobre su conversación con Herrera. ¿Venzor? Venz-remo? Mientras transcribía la cinta más tarde, seguía oyéndolo decir “Venzor”, no “Venzer”, que siempre había estado pronunciando como “Venz-air”. Acento

Después de Nowlin, el siguiente escritor en interesarse por el legado mexicano de Williams fue Ben Bradlee Jr., periodista y editor veterano del Boston Globe. Su biografía de Williams, The Kid, The Immortal Life of Ted Williams, se publicó en 2013 y se convirtió en un bestseller del New York Times.

Williams was told not to speak on behalf of Black players in his Hall of Fame acception speech, but he chose to anyway. Gettyimages A Williams se le dijo que no hablara en nombre de los jugadores negros en su discurso de aceptación en el Salón de la Fama, pero decidió hacerlo de todos modos. Gettyimages

en la primera sílaba. Mitad mexicana y mitad francesa, había escrito Ted”.

Una referencia cruzada con el certificado de nacimiento de Williams y Nowlin confirmó el error que había obstaculizado su investigación durante años.

Sus siguientes paradas fueron Santa Bárbara, California y El Paso, Texas, para conocer potencialmente a más miembros de la extensa familia mexicana de Williams. Nowlin solo logró reunirse con sus familiares en El Paso, ya que los de Santa Bárbara habían fallecido todos.

Ambas ciudades, junto con San Diego, son lugares vitales en la vida temprana de Williams y la de su familia. El Paso es donde su madre pasó los primeros años de su vida, y Santa Bárbara es donde se asentaría su familia.

San Diego es donde los padres de Williams, May y Samuel, se asentarían con él y su hermano Danny.

AVERGONZADO DE SU FAMILIA

Bradlee Jr. analizó con profundidad la herencia mexicana de la leyenda del béisbol y cómo las dificultades de su infancia se tradujeron en relaciones difíciles y arrebatos de ira más adelante en su vida.

El primer capítulo del libro se titula “Vergüenza”.

Comienza exponiendo la vergüenza de Williams de su propia familia. Ya sea de su madre, “la devota del Ejército de Salvación y ejemplo del San Diego de la era de la Depresión”.

“Que parecía mucho más comprometida con su misión callejera que con la crianza de sus dos hijos”.

Su padre, “que dirigía un estudio fotográfico cursi en el centro, donde atendía a los marineros de San Diego y sus fulanas”.

“Y a quién le gustaba darle a la botella”.

O su hermano menor, “un malvado y mezquino armado con pistola que iba siempre un paso por delante de la ley”.

“Quien resentía amargamente con la fama y el éxito de Ted”.

“Ted siempre se avergonzó de cómo lo educaron”, se lee en la primera frase del libro de Bradlee Jr.

Independientemente, su tío mexicano, Saul Venzor, es reconocido por muchos biógrafos (incluido Bradlee Jr.) como el primero en introducir a Williams al béisbol.

AVERGONZADO DE SUS ORÍGENES

El resentimiento hacia su familia se extendió a su herencia mexicana, que a lo largo de su carrera como jugador vio como algo que le impediría competir en el escenario más grande del béisbol.

“Ted no quería que nadie supiera que era en parte mexicano”, escribió Bradlee Jr. citando al viejo amigo de Williams, Al Cassidy.

En cambio, debido a su tez clara, Williams se identificaría como “vasco”, oriundo del País Vasco, en España. La mentira fue mantenida incluso por su familiar más cercano, Sarah Venzor Diaz, cuando Bradlee Jr. la entrevistó para su libro.

“No tenemos herencia mexicana en nuestra familia. Somos vascos”, dijo.

Una vez, mientras viajaba en tren de

NOMBRE COMPLETO Theodore Samuel Williams

NACIMIENTO San Diego, California 30 de agosto de 1918

NACIONALIDAD Estadounidense

POSICIÓN Jardinero izquierdo

Fuente: Wkipedia regreso a San Diego después de su temporada de novato en la que llegó a alcanzar la cuarta posición en la votación de MVP y ser declarado novato del año por Babe Ruth, Williams se encontró con su familia predominantemente mexicana esperando para recibirlo en la plataforma.

“Ted se retiró apresuradamente después de ver al grupo heterogéneo desde lejos”, escribió Bradlee Jr.

Pensó que ser visto con ellos significaría el final de su carrera. 1939 fue ocho años antes de que Jackie Robinson rompiera la barrera del color en las Grandes Ligas con los Dodgers de Brooklyn, y el dueño de los Red Sox de Williams, Tom Yawkey, supervisara el último equipo en agregar un jugador negro a su lista.

Como lo mencionan muchos escritores y familiares de Ted Williams en una entrevista con PBS, “El mejor bateador que jamás haya vivido”, Williams también era muy consciente del perjuicio al que se enfrentaban los mexicanos en el sur de California cuando era niño. El problema de “hacerse pasar por”

En respuesta, se hizo pasar por blanco, a pesar de que no era el primer latino ni siquiera el primer mexicano en competir en la gran liga. Ese honor lo tuvo Mel Almada, quien debutó con los Red Sox de Williams en 1933, seis años antes de que “The Kid” comenzara su propia carrera.

El fallecimiento de Williams ha sido un punto de discordia para muchos al considerarlo uno de los mejores latinos que jamás haya honrado una cancha de béisbol. El Salón de la Fama de la Herencia Hispana lo incorporó como parte de su clase de 2002, pero la Major League Baseball lo dejó fuera de su propia lista de 60 “Leyendas latinas” en 2005.

El profesor de Historia del Deporte de Illinois, Adrian Burgos Jr., también se ha manifestado en contra de “insertar retroactivamente a Williams” en la historia de los latinos en el béisbol porque no se identificó como tal.

En busca de apoyo, Burgos Jr. describió las experiencias particulares vividas por latinos que compitieron antes de Robinson en la MLB, que Williams evitó con su fallecimiento.

“Estos latinos consiguieron entrar, en su mayor parte, no porque fueran blancos sino porque no eran definitivamente negros”, escribió para Sporting News.

Señaló a jugadores como Miguel Ángel González, nacido en Cuba, cuyo nombre no solo fue anglicizado como “Mike”, sino que su acento también se convirtió en objeto de burla.

También hay que hacer mención a las experiencias de los latinos en el sistema agrícola aplicado por los senadores de Washington en el sur del país durante los años 30 y 40.

“Sus encuentros en las ciudades de Jim Crow y alrededor del circuito de las Grandes Ligas les enseñaron que, si bien no eran negros, ciertamente no los veían como su compañeros ‘caucásicos’ o blancos”, escribió Burgos Jr.

Sarah Venzor Diaz

APOYO A LAS ORACIONES NEGRAS

Lo único que le da crédito a Williams es haber apoyado públicamente la inducción de jugadores negros al Salón de la Fama de la MLB durante su discurso en el Salón de la Fama de 1966.

“Espero que algún día, los nombres de Satchel Paige y Josh Gibson puedan ... agregarse al símbolo de los grandes jugadores de la Liga Negra que no están aquí solo porque no se les dio una oportunidad”, dijo Williams a la multitud el 25 de julio de 1966.

Cinco años más tarde, Paige se unió a Williams en el Salón como la primera jugadora de la Liga Negra.

Si bien a “The Kid” no se le puede dar todo el crédito por el hecho de que la MLB finalmente indujo a los jugadores negros a su Salón, su discurso fue el detonador de la discusión. De la misma manera, los biógrafos de Williams han iniciado el debate sobre su propia identidad latina secreta.z

Williams is known as one of the best MLB players of all time and dubbed “the greatest hitter of all time.” Gettyimages Williams es conocido como uno de los mejores jugadores de la MLB de todos los tiempos y apodado “el mejor bateador de todos los tiempos”. Gettyimages