7 minute read

DISCUSSION PANEL:

regarding the problem, it does not intend to generate testimony of what happened.

However, the most significant contribution of this article seems to be the conceptual construction of a “cartography” as a kind of map holding all the agents involved and the problems surrounding “the curatorship of Architecture at the Venice Biennale.”

Advertisement

The table was guided by the two key questions that framed the meeting: First, what is the reason, locally and internationally, for having a national pavilion in Venice (taking into account the symbolic, cultural, professional, and academic effects)?; Second, what are the tasks and implications of the curatorial submission of Architecture?

The article includes a series of tension points, with diverse answers and discussions regarding these questions. These points range from the value of the pavilion for the construction of national cultural richness, the “not coincidental” fact that the country has a pavilion, the absence of curatorial discipline

47-Degree in Psychology and Plastic and Visual Arts (Udelar). Master in Psychology and Education (Faculty of Psychology, Udelar). Adjunct professor of the Department of Aesthetics of the IENBA and the Sociocultural Area of the Bachelor’s Degree in Visual Communication Design (Udelar). Research line: aesthetic practices and subjective formations. Author of books and articles.

48- Publication in Patio: http://www.fadu.edu.uy/patio/?p=75077

49-”(...)we do not intend to generate a testimony of what happened, but rather, with courage, we try to open some path in the woods even if you lose (Heidegger) afterward. For this reason, we will not identify the “authors” of what was said for our analysis since we attend to the signifiers and their drifts: misunderstandings, alliances, jokes, and refrains; the party of knowledge, taking the words of Denise Najmanovich.” Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national and the simplification of Curatorship to a formal act,51 the dependency economics of otherness (institutions),52 the scope of the exhibition as a deep bibliography, the need to experiment and generate a culture of exhibitions, the exclusivity of its participation53 and the mediatic nature of the commission. The article approaches the panel discussion with a neutral vision of the event, while some positions were essential to review. For example, the conversation around the disciplinary aspect of the Curatorship was the root at which most discussions were developed. The quotes below are taken from the discussion panel in an audiovisual record of the event archived in the School’s audiovisual media service. 54

Martin Craciun, who works as a curator, expressed that in Uruguay, Curatorship is not trained, and submitting an exhibition has the expertise to achieve “(…) a deficiency that exceeds the architectural discipline because it is different, it is another language (...)”. While Carina Strata, Cultural Academic Assistant, opposed expressing the idea that communicating architecture is part of the discipline and deep on it by asking, “(…) How is it communicated in the Biennial, and what is wanted to be communicated? (…)”.

This discussion breaks down into two structural debates, the “what” and the “how” it is shown. The “what” is shown was criticized by Emilio Nisivocioa, who understands that the Biennial is a space for Curatorship and defined it as “Curatorship is not a show like Ford’s, where you will see the latest Fordist production models (...),” to relate it to the need to incorporate discourses and critical thinking, also by explaining the message regarding the different users who visit the Biennial, that is, “to whom” it is shown. Define who the public is; it would be one of the parameters to define the “what” and the “how.” Nisivoccia identifies different users, first the “biennials” who visit the exhibition quickly and second, the one who searches for a bibliography and sources of information.

Gustavo Vera Ocampo criticizes the lack of local participation “(...) we have not achieved any type of participation instance in the local environment (...) it has remained as something that goes outside and has not finished consolidating a repercussion inside.” So far, activities have been carried out before the Biennale event, like LUP at the MNAV, and after the event, like shows in other museums of most submissions, excluding Reboot. This aspect has been a vital feature of future submissions, such as Prison to Prison (2018 proposal), which was a pioneer in carrying out activities in parallel to the development of the Biennale. Furthermore, this aspect could be reconnected with the “curatorial training” problem that, as Nisivoccia describes well, “(...) we must begin to dialogue and having the possibility of testing, professionalizing and having more experience within us, not like in a workshop, while trying other kinds of practices...” This expression of the desire for “curatorial training” or test space for curatorial practices appears earlier in the statement of the jury of the 2016 edition made up of Emilio Nisivoccia, Patricia Bentancur, and Bernardo Martin those who express: “(...) it would be interesting for the School try to build and pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 131.

50- Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 131.

51-” (...) as expertise: circulating the voice in English, the foreignness of assembly knowledge stood out more, and this is found in another place that is not the discipline of architecture” Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 132.

52-“(...) Thus, this question generated an emergence of faces, which took the value of the FADU, the Society of Architects of Uruguay, the Municipality of Montevideo, the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC), from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MRE), from the Friends of the Art Biennial Foundation.” Magalí Pastorino in the article “A look at the Uruguayan national pavilion in Venice” in Revista R15, FADU (Montevideo,

2017) p. 135.

53-” (...) at a work table where the exhibitors were males-adults-whites-people with good manners-etc.” Magalí Pastorino in the article “a look at the national pavilion of Uruguay in Venice” in R15 Magazine, FADU (Montevideo, 2017) p. 135.

54- Venice Pavilion Table, SMA FADU Archive (Montevideo, 2017) 55- Catalog of the LUP exhibition for the XI International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2008, page 13. https://issuu.com /miguelfascioli/docs/celestial_body/172 preserve its own exhibition space equipped with adequate infrastructure and supports. In this way, many projects that have not been awarded could be developed in the local environment. In addition, it would allow gaining experience in Curatorship, assembly, presentation, and communication of ideas.” This proposal would undoubtedly help the architecture show become independent of the exhibition design “inherited from the plastic arts,” as Craciun demands at the beginning of the panel. Moreover, Craciun doubts the necessity for “a pavilion,” proposed by Pedro Livni in the 2012 edition, by saying that it could be more appropriate in the local context than in the Venice Gardens. Since this Biennial is not the only one or the most significant, there are other biennials in other places and with other formats, like Chicago, Sao Paulo, or Quito experience. proposal “Freespace” by Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara. Also, “proximamente,” in English, means “soon,” selected for the 17th edition, follow the same path. Is it due to a generational shift? Or because both curatorial teams have members who worked with curatorial practices somehow? Are there similarities between the Prison to Prison proposal and the main features discussed on the panel? All these questions require a more historical perspective to approximate an answer, but undoubtedly, there is an evident influence of the discussion panel on the future development of these practices. For this reason, those last two proposals are not included in the period studied.

Another argument that emerged was the foreignness of the jury around curatorial practices; despite the School used to nominate as jury the people who participated in previous editions, they are enough, so others are chosen for their academic or professional expertise, such as Diego Capandeguy, Gustavo Scheps, Bernardo Martin, and Conrado Pintos. In addition, however, they need to gain experience in curatorial practice. Martin Delgado intercedes from outside the panel with two pertinent comments. First, he proposes building a path to achieve automation and building a structure that will last over time, like the architecture trip, allowing us to repeat a model that adapts over time and provides expertise. Secondly, proposes to abandon self-definition and change the question “What is Uruguay’s contribution to the global discussion through the pavilion?” an essential aspect of what would be the Prison to Prison proposal the following year.

The Prison to Prison proposes with a solid critical component the expansion of contemporary architectural problems from a specific phenomenon, the prison. It is articulated within the general

These issues are possible to discuss, work on and change. Nevertheless, there is a crucial factor that Pastorino defines as “otherness,” which is the economic and legal dependence on the participation of the School as the managing body of the shipment to the pavilion. According to Strata, “in the Ministry, there is the commission of visual arts, which according to what is designated by law, is for the shipment of arts Biennales. Although the law predates the architecture biennial, it is not updated, and art supplies are doubled compearing to architecture”. This diffused responsibility for the pavilion causes, for example, that it needs a representative Architect in charge of the repairs and a permanent curator who makes possible the continuity of international relationships with the media world of the Biennale. To conclude, considering the curatorial practice is an assemblage of parts and agents articulated in different dimensions. As this essay shows, the lack of legal and institutional frames, economic strategies, and non-practice continuity that allow us to exercise a technical prelude leaves our production in a curatorship without curators. Anyhow, it generates structural instability, which forces those interested in the sociopolitical role of Architecture to ask ourselves: What are the tools and means we can use to build an authentic role of Architecture Curatorship?

- Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli, Catalog of the LUP exhibition for the XI International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, (Uruguay, 2008), https://issuu.com/ miguelfascioli/docs/cuerpo_celeste/172

- Emilio Nisivoccia, Lucio de Souza, Martin Craciun, and Sebastian Alonso, Catalog of the exhibition “5 narratives, 5 buildings”, page 9, (Uruguay, 2010), see more: https://issuu. com/martincraciun/docs /5_buildings_5_narratives

-Miguel Fascioli, Research initiation project: The national pavilion at the Venice Biennale. (Uruguay, 2012)

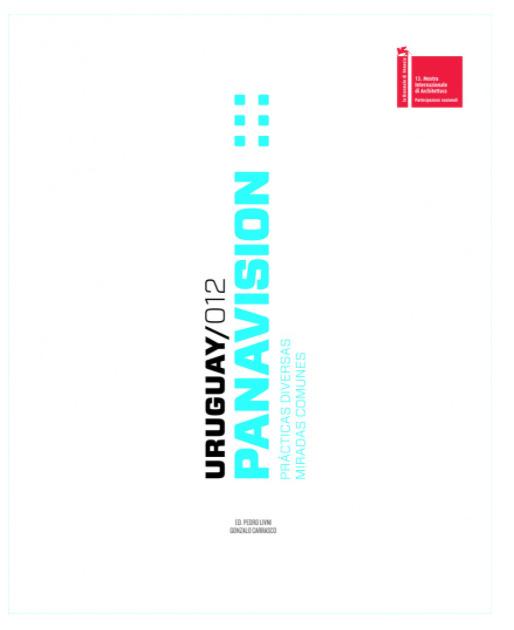

- Pedro Livni and Gonzalo Carrasco in the Catalog of “Panavisión: diverse practices, common views”, page 18, (Uruguay, 2012).

- Martín Craciun, Jorge Gambini, Santiago Medero, Mary Mendez, Emilio Nisivoccia, Jorge Nudelman, Catalog “The Happy Village: episodes of modernization in Uruguay”, page 19, (Uruguay, 2014).

- Marcelo Danza and Miguel Fascioli, Catalog of the exhibition “Reboot, 2 lessons of architecture” (Uruguay, 2016). https:// issuu.com/miguelfascioli/docs/catalogo_issuu_reboot

- Magalí Pastorino Rodriguez, Article “A look at the Uruguayan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale” in R15 Magazine, (Uruguay, 2017)

- Sergio Aldama, Federico Colom, Diego Morera, Jimena Ríos, and Mauricio Wood in Catalog for the Prison to Priston exhibition, (Uruguay 2018)

- SMA, the archive of the Discussion Panel: “The Venice Pavilion” moderated by Magalí Pastorino Rodriguez within the framework of the R15 in 2017.

- Interview with Emilio Nisivoccia