5 minute read

Theoretical Framework

The Identification Triad Theory

To formulate a foundation for the core principles, the Identification Triad Theory can be utilised. An article titled ‘Explicating place identity attitudes, place architecture attitudes, and identification triad theory’ in the Journal of Business Research explored this concept with regards to place identity and architecture. The aim of the paper was to “investigate place architecture (the focal construct) and its relationship to place identity (as antecedent) and internal identification (as an outcome).” (Balmer, 2008, p.325).

Advertisement

The study was conducted by Mohammad Mahdi Foroudi of Faroudi Consultancy, John M.T. Balmer and Weifeng Chen of Brunel Business School , Pantea Foroudi of Middlesex Business School and Paschalia Patsala of the Arts and Humanities Research Council UK.

The approach takes into consideration six key instigators of place identity and how they interconnect (Fig.2). These instigators are visual identity, philosophy, mission and value, communication, spatial layout, physical stimuli and symbolic artefacts. This concept gives precedent to people’s perception of both ‘Place Identity’ and ‘Place Architecture’, showcasing that “the uniqueness of a place identity is likely to be determined in part by its perceived identification” (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003).

Fig.2 The research conceptual framework ((Mahdi Foroudi, 2020)

It can be understood as a structure from which interpretations can be drawn explaining the role of people within the identification of architectural form in relation to their own perceptions (Fig.3).

A series of hypotheses were accumulated in response to the concept of corporate place identity. These included such statements as “The more favorable the place architecture design is perceived by internal-stakeholders, the more favorably they will identify themselves with that place.” and “The more favorably the visual identity is perceived by internal- stakeholders, the more favorably the symbolic artefacts are perceived by internal-stakeholders.” (Balmer, 2008, p.323).

These examples break down the perceptive relationship between people, place and architecture This relationship is then further expanded upon, via reference to ‘Place Communication’ in the ‘Journal of Marketing Communications’. ‘Place Communication’ “refers to a place identity and can influence strategy and underpin communications” (He & Mukherjee, 2009).

Although this concept is applied to understanding corporate identity, this could become increasingly integrated into the architect/public dialogue. This could start to reduce the disparities that occur between the two parties during the design process.

These concepts of internal stakeholders and communication could be utilised to represent the individual and communal perception that contribute to and are a product of place identity. The identification triad theory can then be aligned to behavioural qualities of place in relation to spatial creation.

Fig.3 Self Sovereign Identity Actors (Mühle, Grüner, Gayvoronskaya and Meinel, 2018)

Sustainable Place Shaping

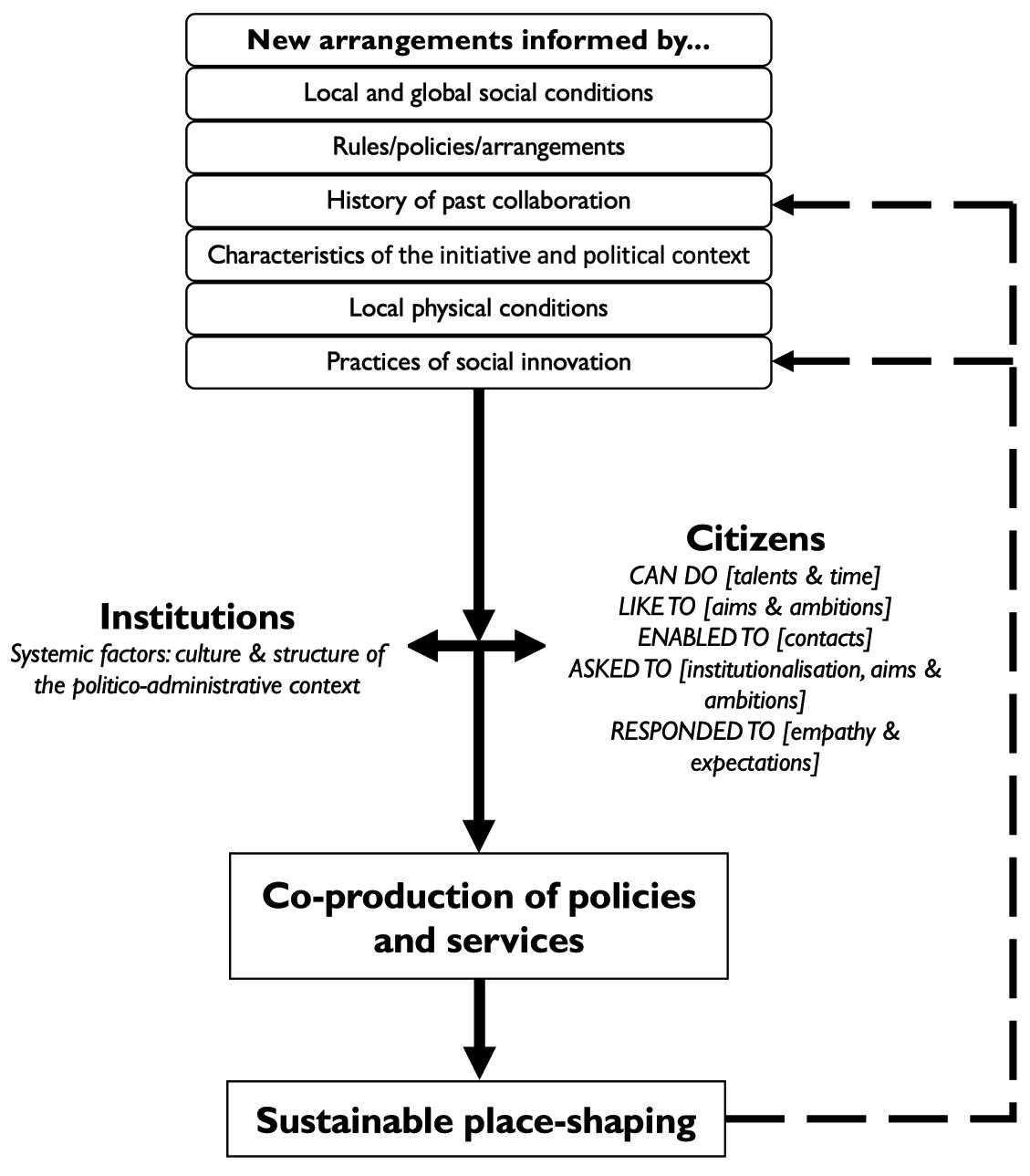

As an extension of the Identification Triad Theory, the ideologies behind “Place Shaping” come as a response to “ differentiated outcomes of intersecting, unbound, ecological, political-economic and socio-cultural processes” (Horlings, 2016, p.33).

It was Professor of socio-spatial planning at the University of Groningen, Lummina Horlings, who argued that ‘Place Making” is not adequate enough to maintain place. She stated that sustainable place shaping allows us to “understand how people make sense of their place and attach values to place” (Horlings, 2016, p.35). Her argument addresses the need for people to become reacquainted and re-evaluate identity and symbolic meaning in order to continually strengthen identification.

This line of inquiry into the notion of place acknowledges the perception of place as something that is continually changing, that place “is considered as not pre-given, but constructed” (Horlings, 2016, p.33). This suggests that if we are to maintain identity, we cannot assume that what we have been given in the past is what represents an identity.

Rather, it is how we continue to live within it, appropriate it and respect it in the present. In sustainably re-engaging with place identity, Horlings proposes three areas to analyse; re-grounding, re-positioning and re-appreciation (Fig.4). Re-grounding focusses on the existing ecology and culture of place as a result of “wider communities, cultural notions, values, assets, technology and historical patterns” (Horlings, 2016, p.34). Re-positioning addresses “ways of

Fig.4 Place and Place Shaping (Horlings, 2016)

value-adding, altering political-economic relations shaped by gloablization” (Horlings, 2016, p.34). Finally, re-appreciation centres on the psychological understanding of re-identification “which includes perceptions, meanings and values attached to place, processes of sense-making and how actors take the lead in appreciating places” (Horlings, 2016, p.34).

To acknowledge the presence of these measures in the perception of place identity, Horlings suggests that we need to “address the temporal, historical, spatial, value-led and multi-scale aspects of sustainability in places and (re-)connect people to place” (Horlings, 2016, p.35). If this examination could be recognised within the design process; architects could begin to unravel the psychological responses to place.

Phenomenological Consideration

To comprehend the conscious interpretation of place, a phenomenological approach should be considered in order to dissect the individuality of place. This can then begin to translate into the physical appropriation of architecture within a place. Phenomenology, has been defined as “the exploration and description of phenomena, where phenomena refer to things or experiences as human beings experience them” (Seamon, 2000, p.158). This initially suggests that the concept refers to how an individual views conditions presented to them.

However, via its application within a communally shared setting, it goes beyond an internal process and can be expressed outside of those limitations (Fig.5). This

Fig.5 Sustainable Place Shaping (de Vrieze, 2019) humanistic attitude towards phenomena could be compared to the idea of place as a humanly driven ideology. It was Doctor of Philosophy Mohammed Qasim Abdul Ghafoor, of Al-Nahrain University, who utilised both of these theories. He viewed the perception of place as a concept that is “largely drawn from phenomenology, was concerned with individuals’ attachments to particular places and the symbolic quality of popular concepts of place” (Mohammed Qasim Abdul Ghafoor, 2013, p.932).

It was Norwegian architect Christian Norberg-Schulz who expanded upon the importance of individuality within spatial configuration when he states that “ ‘space’ denotes the three – dimensional organisation of the elements which make up a place, “character” denotes the general ‘atmosphere’ which is the most comprehensive property of any place” (Norberg-Schulz, 1991, p.11). It is re-engaging with this fundamental ‘character’ that will integrate not only the adaptive functionality of place within the design process, but also the highlighting of psychological identifiers associated with it.

As people continue to relate meaning to situations and symbols, the role of phenomena should be more highly regarded by the architect. It was French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty who questioned spacial experience as a basis for understanding other forms of connection when he stated, “Does not the experience of space provide a basis for its unity by means of an entirely different kind of synthesis?” (Merleau-Ponty, 2002, p.284). Unpacking this interpretation of space will become a basis from which re-identification can occur, bringing this otherwise subconscious concept into the forefront of design consideration.