5 minute read

Materialisation

To appropriate physical gestures with respect to the existing fabric and the environmental impact whilst evolving the material palette of a place.

The effective use of materials within both the exterior and interior environments can start to illustrate a recognition of place identity. It is the physicalisation of individuality that are the “key elements of the transmission of cultural identities from one generation to the next” (Akşehir, 2003, p.13).

Advertisement

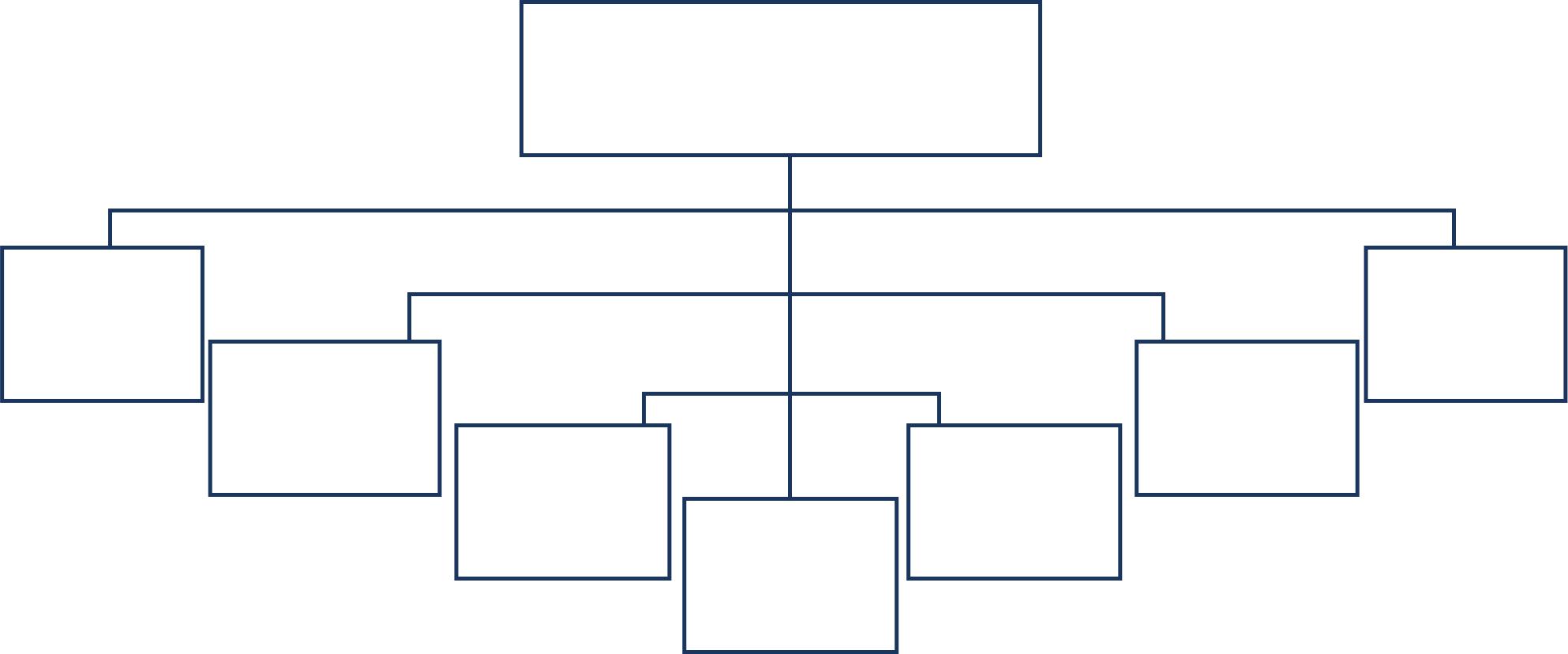

In reference to the ‘identification triad theory’, this principle examines the attitudes of ‘Visual Identity’ and ‘Physical structure/spatial layout’. These instigators can be closely considered within the design process (Fig.12).

(Delitz, 2017, p.38). It was British sociologist John Thompson who commented on the importance of

argued that it, “can never start from scratch; it always builds upon a pre-existing set of symbolic materials which form the bedrock of identity” (Thompson, 1996). This form of symbolism within materials can portray a respect for not only the environment, but the people who inhabit it.

It is the architect’s obligation to appraise the significance of materials and their application, ultimately affecting their sensitivity to place as “architectural artefacts are not exterior to society or to human social interaction” materials in identity formation when he

The main characteristics of identity in architecture

Shape & form of building General design principles Materials

Relationship with context

Temporal organisation

Semantic organisation

Spatial organisation

Fig.12 Main characteristics of identity in architecture (Authors own image) (Based on Torabi’s diagram, (Torabi and Brahman, 2013)

Chapel of St Benedict - Peter Zumthor

An example of respecting identity within a building’s materiality is Peter Zumthor’s Chapel of St Benedict in Sumvitg, Switzerland, completed in 1988 (Fig.13). In briefing the project, the village authorities “had issued the building permit with the comment “senza perschuasiun” (without conviction)” (Yue, 2013, p.1). This open approach to the brief left Zumthor free to interpret it.

This could have initially be seen as an oversight in maintaining a physical avatar of identity within the community. However, as a result of his previous experience in carpentry, he was “greatly influenced by the sensitive use of rustic material” (Yue, 2013, p.1). This led to an approach which showed a respect for the embodied meaning behind material and spacial considerations. The church utilised timber shingles on the building’s exterior (Fig.14) as it is “a common material used for the local houses” (Yue, 2013, p.1) that “speak to traditions in the region” (Zukowsky, 2006). This preservation of traditional methods takes into account specificities of a locality, whilst continuing to develop their contemporary applications.

Zumthor addresses the historical significance of the site with regards to the ethics of St. Benedict, after whom the original church was named before an avalanche struck the village and destroyed the previous church in 1984. It is believed the saint emphasised the importance of “the living community of men who live, work, eat and pray together as a permanent element…giving a sense of togetherness” (Yue, 2013, p.4). He did this by “eliminating the usage of internal wall” (Yue, 2013, p.4), thereby eradicating any form of division between individual identities and embracing a single community (Fig.15).

Fig.13 St Benedict’s Chapel (Camus, 2013) Fig.14 Timber Shingles (Camus, 2013)

Fig.15 Inside St Benedict’s Church (Camus, 2013)

It was architectural theorists Zohreh Torabi and Sara Brahman who suggested examples of material communication. They suggested the use of brick and timber “shows the belief in world mortality in the community.” (Torabi and Brahman, 2013, p.110) (Fig.16) and that the use of “stone in palace of the Kings is a symbol of building stability and strength of kings.” (Torabi and Brahman, 2013, p.110) (Fig.17). Combining material identity with new methods like this embraces “two separate moments of a phenomenon: a cultural moment and a technological moment.” (Torabi and Brahman, 2013, p.106).

As phenomena is a time sensitive quality to the human experience of architectural space, these deliberations cannot be limited to singular moments. They must instead continue to support a ‘congenial relationship’ to establish a “relationship between the buildings with their surrounding” (Torabi and Brahman, 2013, p.106) that evolves over time.

It could be argued that, because of the material and topographical consideration employed by Zumthor, this forms a congenial relationship with the environment. However, when “we can intentionally distinguish the shape of the building from the context” (Torabi and Brahman, 2013, p.106), this is known as a ‘conflict relationship’.

Fig.16 Tudor House (Daniels, 2019)

Fig.17 Palace of the Kings (Hepburn, 2008)

Kuwait National Assembly Building - Jørn Utzon

An example of this type of relationship, that attempts to express cultural identity, is the Kuwait National Assembly Building by Jørn Utzon, completed in 1982 (Fig.18).

The building is functionally a representation of the identity of Kuwait as it “houses government offices, spaces for representation, a large assembly hall and a mosque.” (Utzon, 2019). Due to both the political and occupational scale, the structure is vast and immediately contrasts the shape of its immediate context.

Utzon based the plan of the building “on the plan of a Middle Eastern ‘souq’ or market” (Utzon, 2019). It is evident that he has regarded symbols of identity within the material and spacial arrangement (Fig.19), however there were those who questioned the specificity of these inspirations. MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) professor Lawrence Vale criticised the inspiration behind the covered plaza, stating that it “hearkens as much to ship sails and a tradition of water-based merchant trade as it does to a nomadic desert tradition” (Langdon, 2019). When identifiers become unclear to those who observe, use and critique architecture, the idea of structural integration is lost. If identity is to remain a relevant concept within future appropriation of architecture and place, there most be a symbolic referral to historic foundations, but adapted to show a clear evolution in the concept of identity.

It’s clear that understanding material identity can help further integrate physical and historical presence to place. To continue the presence of identity, the material application must evolve and continually be expressed within the design process in order to relate physical gestures not only to BREAAM and Approved document regulations but also to its psychological instigators within human consciousness.

Fig.19 Kuwait National Assembly Building interior (Utzon, 1971)

Fig.18 Kuwait National Assembly Building (Utzon, 1971)