3 minute read

1.1 Glacier retreat, psychology, and design

Introduction

1.1 GLACIER RETREAT, PSYCHOLOGY, AND DESIGN

Advertisement

There has been a recent flurry of research and news articles ringing alarm bells for people dependent on disappearing glaciers. The New York Times published, “Glaciers are Retreating. Millions Rely on Their Water” (Fountain, 2019) and The Guardian published, “A third of Himalayan ice cap doomed, finds report: even radical climate change action won’t save glaciers, endangering 2 billion people”. Although glaciers have been retreating since the end of the last ice-age, since the 1980s, their retreat has sped up to unprecedented levels (Purdie, 2013). The large amount of attention that this topic has received indicates distress, concern, and a shout for active engagement.

Glacier retreat is a powerful landscape indicator for climate change and it has economic and non-economic implications for communities (Jurt, Brugger, Dunbar, Milch, & Orlove, 2015; Purdie, 2013). Increased flood risk, more frequent mudslides, and sea-level rise are the first amongst a list of issues caused by glacier melt (Zemp et al., 2015). Economic implications include the loss of hydroelectric power, water for drinking and irrigation, and income from tourism. The Andean glaciers, for instance, feed into streams that power hydroelectric dams and provide municipal drinking and irrigation water. The Himalayan glaciers hold the world’s second largest fresh water reserve after Greenland and supply the rivers of southern Asia with enormous amounts of irrigation water during the lengthening dry seasons (Thompson et al., 2017; Jurt et al., 2015). The Canadian, New Zealand, and European glaciers support communities that depend on them for agriculture, hydro-power and tourism (Milner et al., 2017; Purdie, 2013).

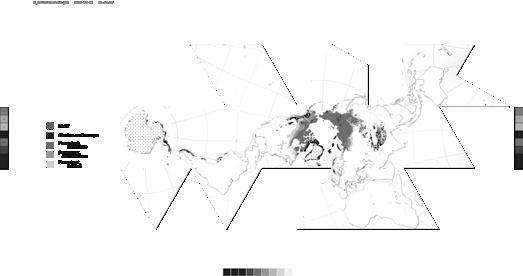

Figure 1-2. The Cryosphere, world map; glaciers and ice caps in black (Adapted from Ahlenius, 2007).

Non-economic implications include the “losses and damages” to the cultural values attached to glaciers. These go beyond water issues and hazards and refer to losing the sense of community, identity, and self-reliance that the glacier enables. Unspoiled glaciers are considered powerful, wild, living, pristine and/or sublime! As they disappear, the cultural narratives and practices weaken with them (Carey, 2007). For instance, Andean communities increasingly struggle to perform annual rituals of walking up to glaciers to present offerings (Jurt et al., 2015, p. 90). Scientific communities also feel the loss as these great “natural environmental archives” melt away (Carey, 2007; Jurt et al., 2015).

The mountain of scientific literature describing glacial processes, human attachment to glaciers, and the implications of their retreat is not matched by publications and projects that respond to them. The few examples include cloaks to cover glaciers in European ski resorts, snow “growing” for snow sports, and artificial

glacier projects in India to provide dry season irrigation water for villages in the Himalayas (Carey, 2007). There are initiatives to save specific glaciers, but the solutions are often engineered, adaptive, and admit to an expiry date.

Engagement still appears to be the exception. Researchers in psychology and social sciences are trying to explain this phenomenon, namely the lack of engagement with environmental degradation, climate change, and related “wicked problems”. Descriptions and terms are emerging to describe what many people internalize as they try to cope. Examples include solastalgia, a painful nostalgia caused by losing ones home environment, environmental melancholia, a paralyzing mourning for a degraded environment, flight guilt, a Swedish term for the guilt felt for polluting when flying, and types of denial, such as ignoring or repressing, climate change-related realities (Higginbotham et al., 2007; Lertzman, 2015; Norgaard, 2011). Renee Lertzman makes a compelling argument for psychological inquiry as a crucial step: “In order to promote advocacy and political action to deal with environmental changes, we must first address the psychological dimensions of issues” (p. 5).

It is intriguing to note the absence of landscape architects in offering responses to economic, non-economic, and psychological dimensions of glacier retreat, because it is a field that prides itself and repeatedly demonstrates its ability to respond in novel and visionary ways to environmental challenges (Clouse, 2014). Glacier retreat presents local issues with global causes that cannot be mitigated locally. This landscape architecture thesis is therefore presented with the challenge and opportunity to explore how a spatial intervention can address the experience and emotions associated with glacier retreat and climate change. If such an intervention integrates economic and non-economic values, and involves people and their lived experiences, it can trigger muchneeded involvement, engagement, and stewardship (Jurt et al., 2015; Lertzman, 2015).