7 minute read

Balance

Balance

By Kate Selby

As instructors, we strive to bring out the best in our students so that they can bring out the best in their horses. One essential element to their success is being in balance. Without a balanced rider, a horse cannot perform in a balanced way. Balance—left to right, up and down, front to back, while in correct alignment —is the foundation on which we build fluid strength that enables us to ride well and to deliver clear, concise aids.

How do we help our students learn to maintain balance on their own? The following visualizations and exercises can teach a rider to self-check their alignment and balance. The process begins by making sure the rider is sitting quietly and without tension.

At a walk—preferably without stirrups—ask the rider to feel the horse’s rhythm and to sense their own breath. Remind the rider not to try to create or mimic the motion for the horse, but to sit quietly and softly. Next, ask them to assess their seat bones. For example, do they feel even on both seat bones, is one lighter, smaller, sharper, or not there at all, what size and shape are they? This is an awareness tool for the rider; there is no need to make corrections.

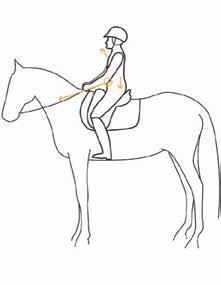

Step one Ask the rider to create up-down balance using the “cutting the body in half” exercise.

From the belly button up:

Stretch the spine up and out through the top of the head, right above the ears, and allow the neck to lengthen. Lift the rib cage gently upward and forward, being careful to lift only from the belly line, and not out of the seat.

“Cutting the body in half”

From the belly button up, stretch the spine up and out through the top of the head; allow neck to lengthen. Lift the rib cage gently upward and forward.

From the belly button down, allow a neutral (perpendicular) pelvis with legs hanging. Release hips to let legs soften. Feel the horse moving freely through lower back, without mimicking the motion.

Note: Many riders, when asked to “sit up” actually lean slightly, arching their back away from the perpendicular. This loses the neutral spine, and creates tension in the arms, which leads to using the reins as support for the upper body.

From the belly button down:

Allow a neutral (perpendicular) pelvis to sit with legs hanging. Release hips to let legs soften. Avoid holding the legs up into the hip joints, or trying to push the legs down. (Don’t work to keep your legs attached to your body — they won’t fall off.) You should be able to feel the horse moving freely through your lower back, without mimicking the motion.

Feel for any tension in joints, especially backs of hands, wrists, and forearms. Find the seat bones again, and reassess as above. Step two Find front-to-back balance by lifting the ribs and extending the frontline of the body.

Bring belly button close to the spine by “hugging” with abdominals while dropping the shoulder blades down.

Practice moving the arm from the elbow softly forward towards the horse’s mouth while keeping the upper body quietly still.

Ask the rider to bring their belly button closer to their spine while dropping the shoulder blades down. This will encourage engagement of the abdominal muscles to support spinal alignment without leaning or gripping.

Note: If the rider struggles to hold themselves up without leaning or pulling out of their seat, ask them to imagine a corset around their middle. Tightening the corset’s “hug” will help engage the abdominals.

Allow the rider to practice moving the arm from the elbow and shoulder forward towards the horse’s mouth (not the ears, chest, or front feet), while keeping the upper body quietly still. Step three When the rider can maintain balance frontto-back and up-and-down over a soft leg, move to the third exercise, focusing on leftright balance.

Most horses and riders are one-sided. It is very easy for the rider to be swayed by the horse’s imbalance; for example, a horse that leans left can create a rider that leans left.

Using the criss-cross exercise, the rider

Inhale. Stretch left shoulder up and outward, downward and outward into right seat bone. Release with an exhale. Repeat on other side: Inhale, stretch right shoulder up and outward, and down and out into the left seat bone. Exhale and release to neutral posture.

can find good left-right balance in the saddle on their own.

Ask the rider to stretch their left shoulder up and outwards while stretching downward and outward into their right seat bone. Hold only for one inhale, then release with an exhale. Repeat the stretch on the other side, raising the right shoulder up and outwards and stretching down and out into the left seat bone. Release to neutral posture.

Note: The rider may find that one side was harder to stretch than the other, and that they feel different in the saddle now. They may even feel a bit off balance if their crookedness was one of their best bad habits. (See sidebar)

Have the rider pick up the stirrups and take up contact. Maintaining an even, active walk, go through each of the exercises again: cutting the body in half, lifting the ribs up and forward, and the criss-cross.

As the balanced rider takes up the reins, they may already feel their horse coming onto the aids. This is an important moment. The rider should accept what the horse gives by keeping their balance and shortening the reins. Many riders, when they feel the horse soften or accept contact, immediately “return the favor” by giving the reins, or softening their body to the point of folding or rounding. These are normal, sympathetic responses.

We work hard to get into and maintain alignment and balance, hoping this will result in a better balanced horse, and lo and behold! It works! We feel grateful and want to reward the horse, as we are taught to do. So we release—but this is exactly the wrong thing to do at this moment. The horse has sought his own reward by coming into better balance under the rider. If we change our bodies at this point, then we actually take the reward away, essentially asking for something different. Maintaining balance in correct alignment is crucial. Otherwise, the game keeps changing, and the horse cannot hope to figure out what the rider actually wants.

We can teach riders to help themselves achieve balance in all directions. Practicing these techniques at the start of every lesson will help the rider learn to “self-check” and correct when their instructor is not there to catch them. These exercises will soon

Best Bad Habits

We all have habits we return to over and over again. Yours could be gripping one rein, or fidgeting with your fingers, or collapsing one hip. Or perhaps you lose focus when schooling, and ride without a plan. Whatever it is, the one bad habit you go to over and over, even as you advance up the levels, is your “best bad habit.” These may stay with us forever; we just need to be aware of them so we can check in frequently and make corrections.

What is your “best bad habit” when you ride?

become a habit that can be used quickly during a ride, allowing students to progress further faster. About the author: An award-winning riding instructor and life-long professional horseperson, Kate Selby is Head Coach of the Middlebury College Equestrian team, and a freelance clinician/instructor. As an author and copy editor, Selby has worked for PR and publishing firms, published articles for equine publications, and written and illustrated four books for young readers. Having spent her life and career outside, working and living with animals—including a pack of foxhounds—she likes to write about the intersection of life with nature.

Your E-Mail Address is important—for us and for you!

ARIA communicates primarily by e-mail with its members. Please make sure we have a working e-mail address for you. If you’re not sure, write to us at aria@riding-instructor.com and let us know your current e-mail address. Thanks!

American Riding Instructor Certification Program

Nationally recognized certification

2

National standards of excellence and integrity

2 Over 36 years of quality and integrity.