Charles Moore

In his 11-work solo exhibition, In Jubilant Pastures, Conrad Egyir examines the concepts of migration and home, embracing themes of double consciousness, identity, and displacement, and drawing inspiration from his own experience. Egyir was born in Ghana 1989, and he moved to the United States in 2008, eventually settling in Detroit. In each of his latest works, Egyir uses a verdant backdrop to bring the so-called “jubilant pastures” to life, shedding light on topics that include land rights, citizenship, and community. Now an American citizen, the artist contemplates what makes a person belong—hinting that people can go anywhere to seek greener pastures, but they find comfort and stability in whatever or wherever it is that they call home.

Kehinde Wiley, Anthony of Padua, 2013, Oil on canvas, 72 x 60 inches (182.9 x 152.4 cm), Seattle Art Museum, Purchased with funds from the Contemporary Collectors Forum

William Blake, The Body of Abel Found by Adam and Eve, c. 1826, Ink, temperara and gold on mahogany, 14.4 x 18.6 inches (36.6 x 47.2 cm), Tate, Bequeathed by W. Graham Robertson 1949

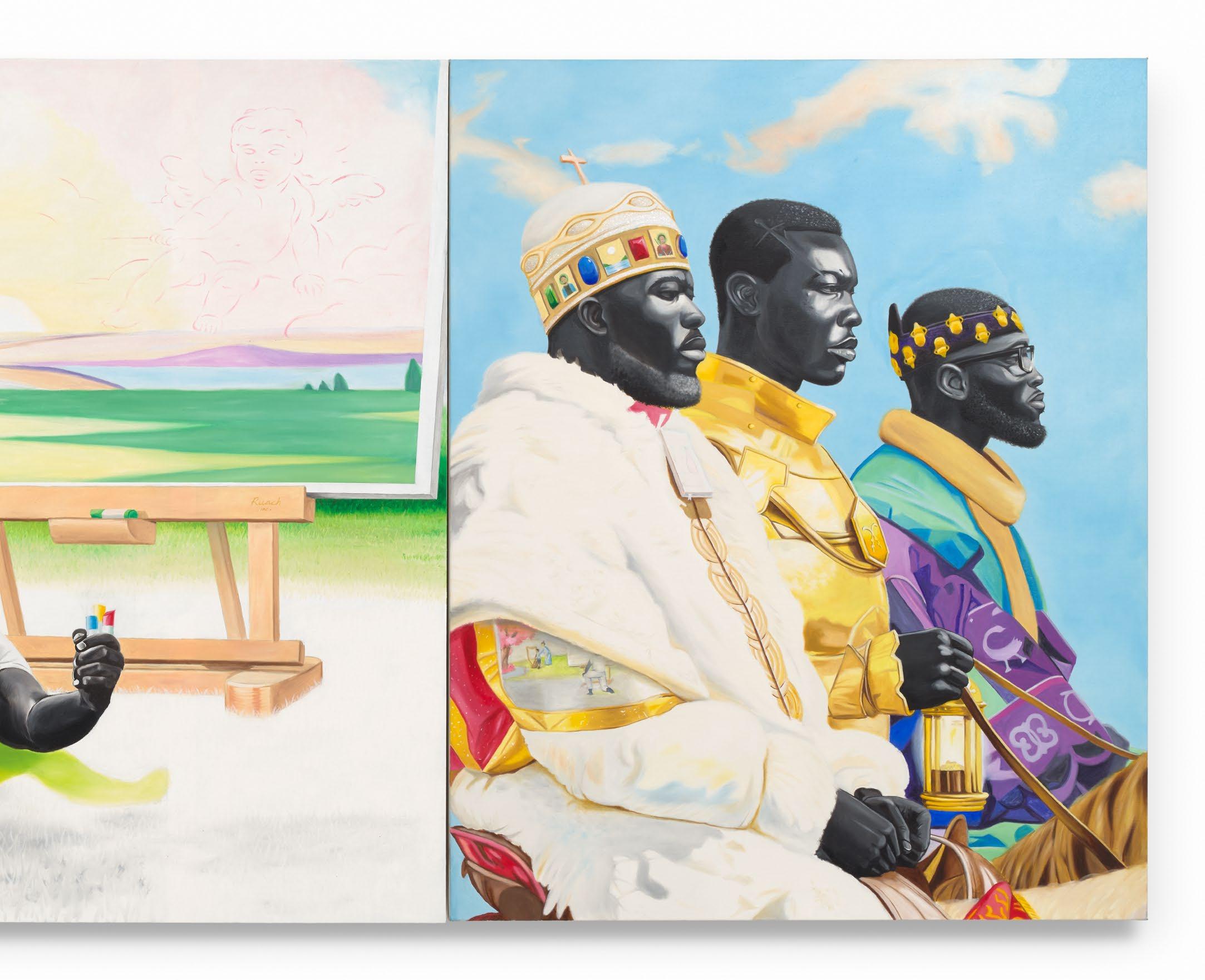

Inspired by the sovereign themes of Kerry James Marshall and Kehinde Wiley, and the regal manner with which they treat their subjects’ skin, plus the surrealism of the South African and British artists William Kentridge and William Blake, Egyir explores the meaning of Blackness, digging into his personal history as an African man in the United States, where Black Americans are noted for their ability to identify foreigners by their accent, speech patterns, and style of dress, and hone in on what it means to be different. The desire to assimilate—to blend into Black American spaces—resonates with the artist. Accordingly, he invites his subjects to occupy the places they wish to inhabit, and he lays the foundation for this process with storytelling.

Egyir notes that in his native Ghana stories are passed down by oral tradition, and he seeks to capture this process through a contemporary Americanized lens. In college, first at Judson University in Elgin, Illinois, and then at the renowned Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, where he earned his MFA, Egyir often turned to African iconography like Adinkra symbols—visual symbols that represent unique proverbs and aphorisms—to make his lush paintings come alive. He has applied these symbols to the narrative of his work, occasionally alongside political or even religious themes. Today, he focuses more on his subjects’ personal stories, using each individual

as a vessel of sorts. Egyir’s symbolism is nuanced, with objects like postage stamps pointing to migration and objects like acrylic combs from the Akan region, which connects Ghana and the Ivory Coast, allowing him to stay grounded to his African roots. His subjects wear sandals, carry dolls, and sit on stools that belong to specific tribes; the details are culturally resonant, and the landscapes offer a universal take on the scenes he creates. Egyir simultaneously embraces his Black Americanness.

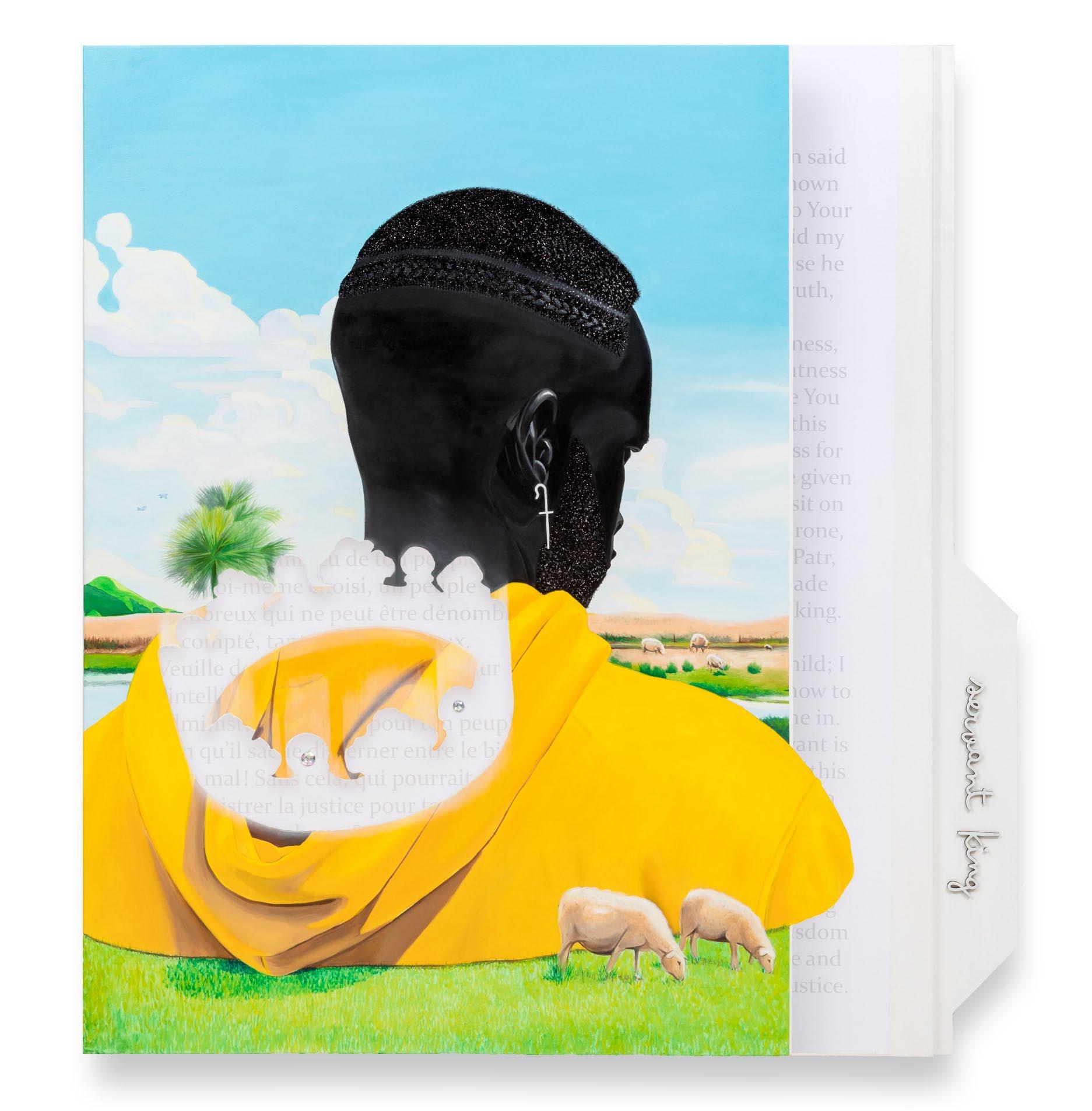

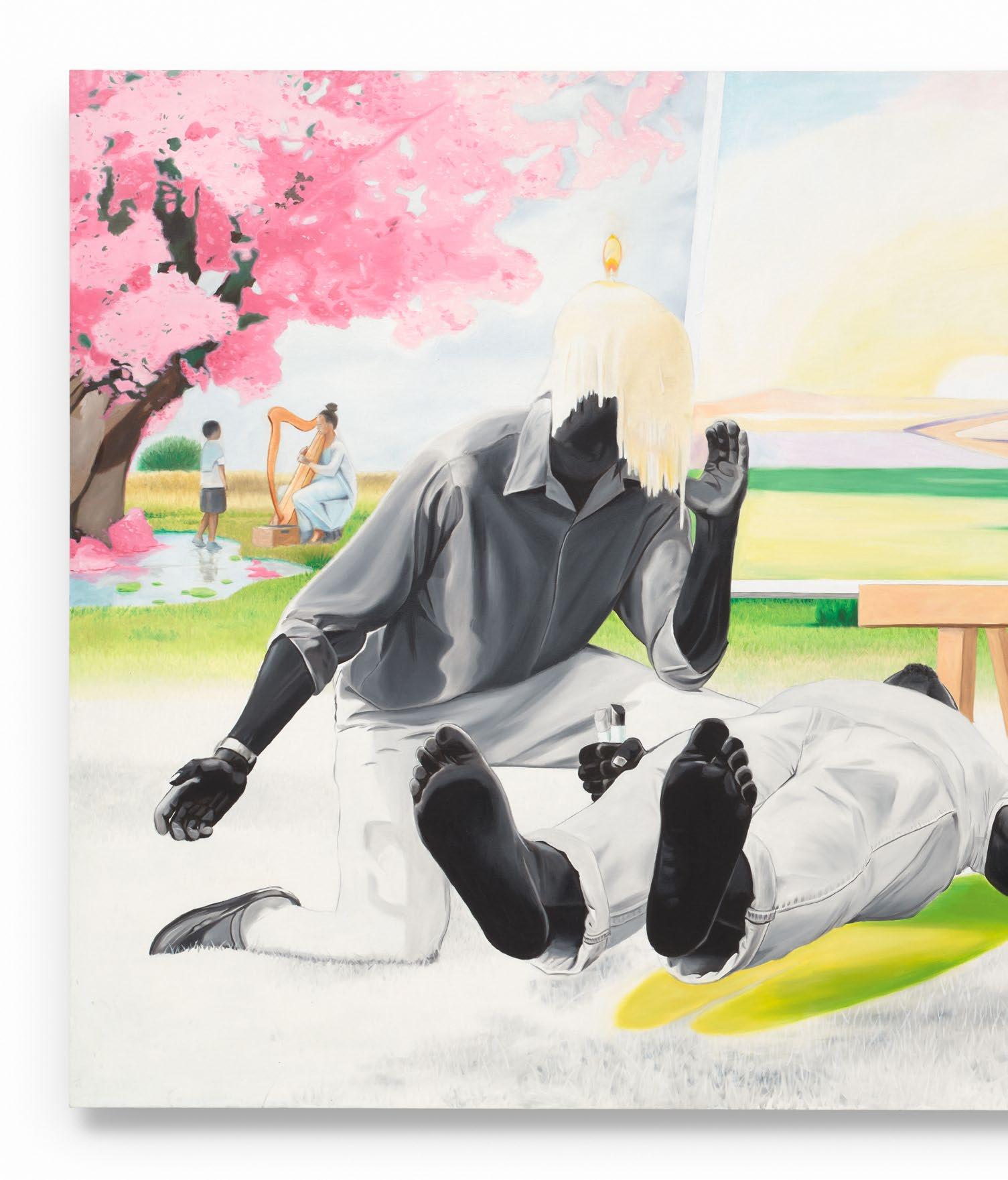

La Gloire de Rois (2024), the largest work in the show, was inspired by one of the artist’s dreams. Its inherent surrealism is all-encompassing, touching on notions of home, place, and sovereignty. (“La Gloire de Rois,” it’s worth noting, is French for “The Glory of Kings.”) In the foreground of the work, a Black male subject levitates on his back, his features indecipherable to the viewer. All we can see is that he is floating outdoors, just inches above a field of some kind, a canvas nestled on an easel right behind him, oil paint sticks in hand, while a second subject kneels before him—his face completely covered by a lit candle that is dripping wax. The second subject serves as a spiritual paradigm—seemingly breathing life, and imagination, back into the initial subject. It’s important to note, though, that these subjects are one and the same, or two versions of a single person; Egyir has a habit of multiplying his subjects within each canvas, with complementary, or at times contrasting, situations shaping their identities. Yet the viewer can’t overlook the use of landscape. A burst of vibrant color decorates the background on the left-hand side: There is a cherry tree in full bloom, pink and abundant, sheltering the green grass below. In this section, a woman, immersed in the scene before her, plays a harp, while a young boy stands beside her, looking on. These scenes unfold in parallel in the work, reinforcing the artist’s pull between two cultures. With migration and empathy—or relating to others—at the forefront of the painting, Egyir multiplies his subjects to craft the composition, weaving together stories of antagonists and protagonists, placing each character within the space, and deconstructing the very notion of colonialism. The artist doesn’t hesitate to play with borders or textures, underscoring the impact of documentation in all forms and embellishing his canvases at will.

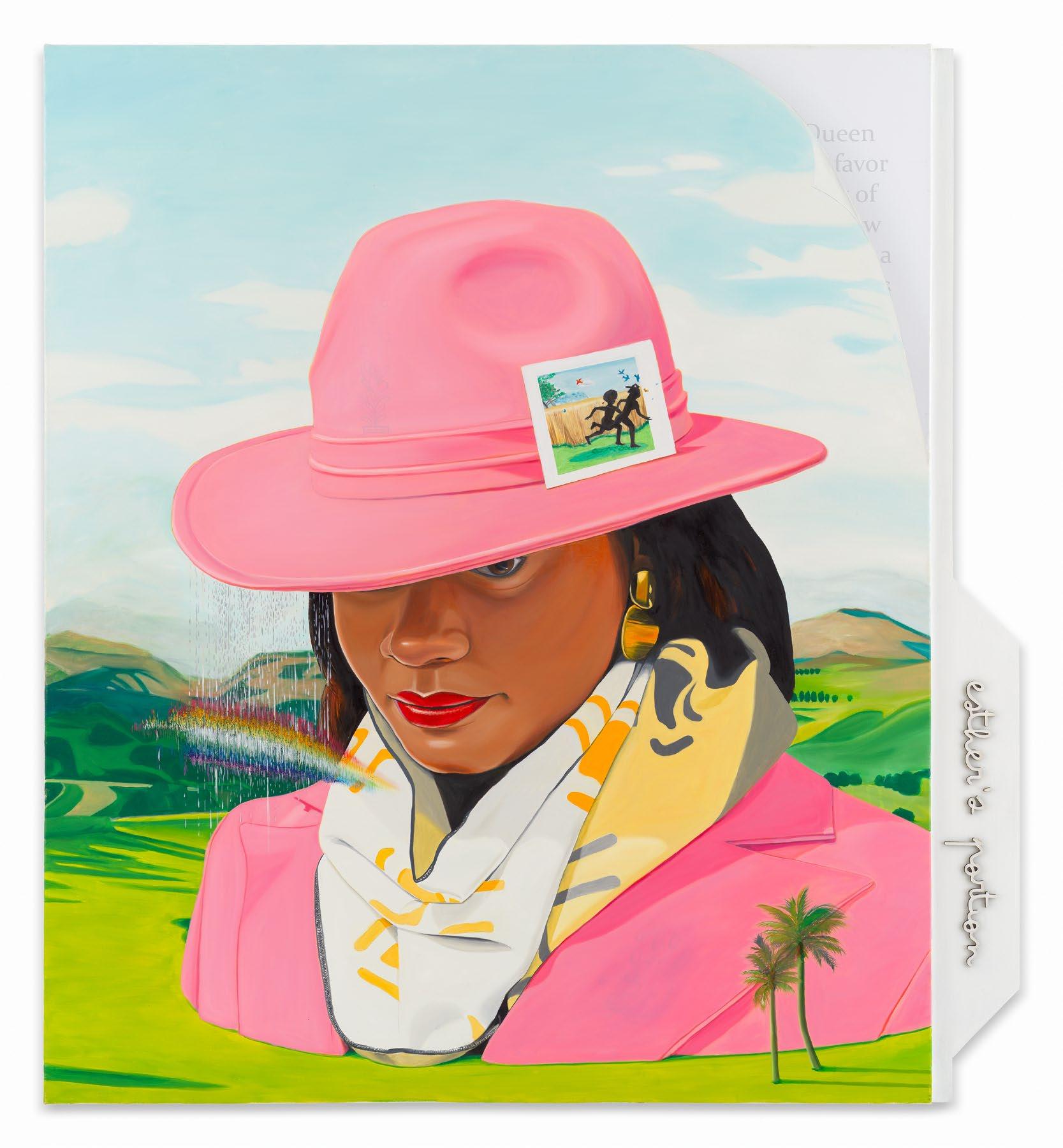

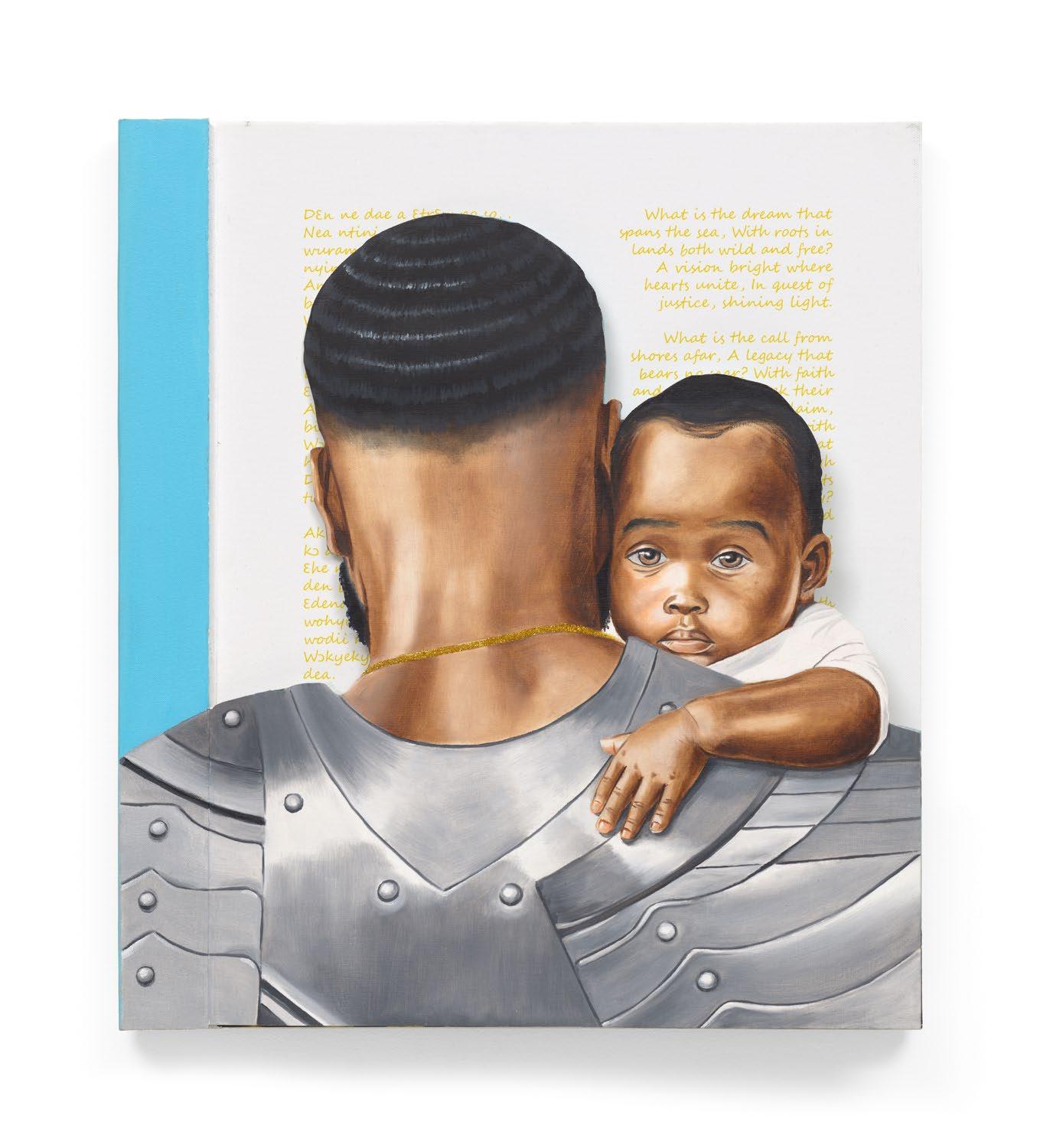

Egyir’s bright color palette is uniquely his, with each work enlivened through colors, through ideas—through the careful application of glitter, even—and ultimately through a desire to craft stories from dreams. Each rich yellow, oceanic blue, or deep green is associated with content the artist has consumed: music, literature, sermons, West African folklore, or, of course, internal dreamscapes. Egyir thinks about the colors that appear in his dreams, allowing his memories of the moment to morph into new concepts entirely; his color selection is the driver behind this, helping each scene to come alive. The resulting canvases are poetic—and not only because the artist has infused poetry, written in English, Twi, French, and Swahili, into four of the works. These four paintings are on wooden panels that open up like a graphic novel or journal. Fusing the impact of visual iconography with that of literature, the artist has adorned these canvases with stories, or special narratives, decorating his paintings with paraphrased quotes that inspire him, and he has sculpted them into something new. In My Knight and Shield (2024), he writes: What promise holds both near and wide / A home where dreams and truth abide? / With hands entwined, they shape their fate / In sovereign lands, they liberate. Here again, Egyir weaves liberation, legacy, and nobility into his paintings; in the work, a knight in shining armor holds a small child on one side, while on the other, a second subject wears a blood-red robe, standing on moss-covered rocks as he looks out at the sea before him, with the initial duo’s silhouette subtly integrated into the canvas. The impact is profound.

Such is also the case in Milk, Honey, and Refuge (2024), which shows a Black female subject sporting white angel wings and doing another woman’s hair, her green dress slipping off her shoulder, while a small child embraces her. The seated woman sits in profile, making eye contact with the viewer and enjoying an abundance of well-landscaped plants in her vicinity. Though the child is imaginary, Egyir notes that both female subjects represent his wife; here, too, the artist has painted the same person twice. His works, in this way, examine relationships with the self. Milk, Honey, and Refuge is a work of abundance, and while the title has religious connotations, liberation is a core theme. The artist emphasizes that when people come out of bondage, they are free—and as a result, they can enjoy the proverbial land of milk and honey. But where do

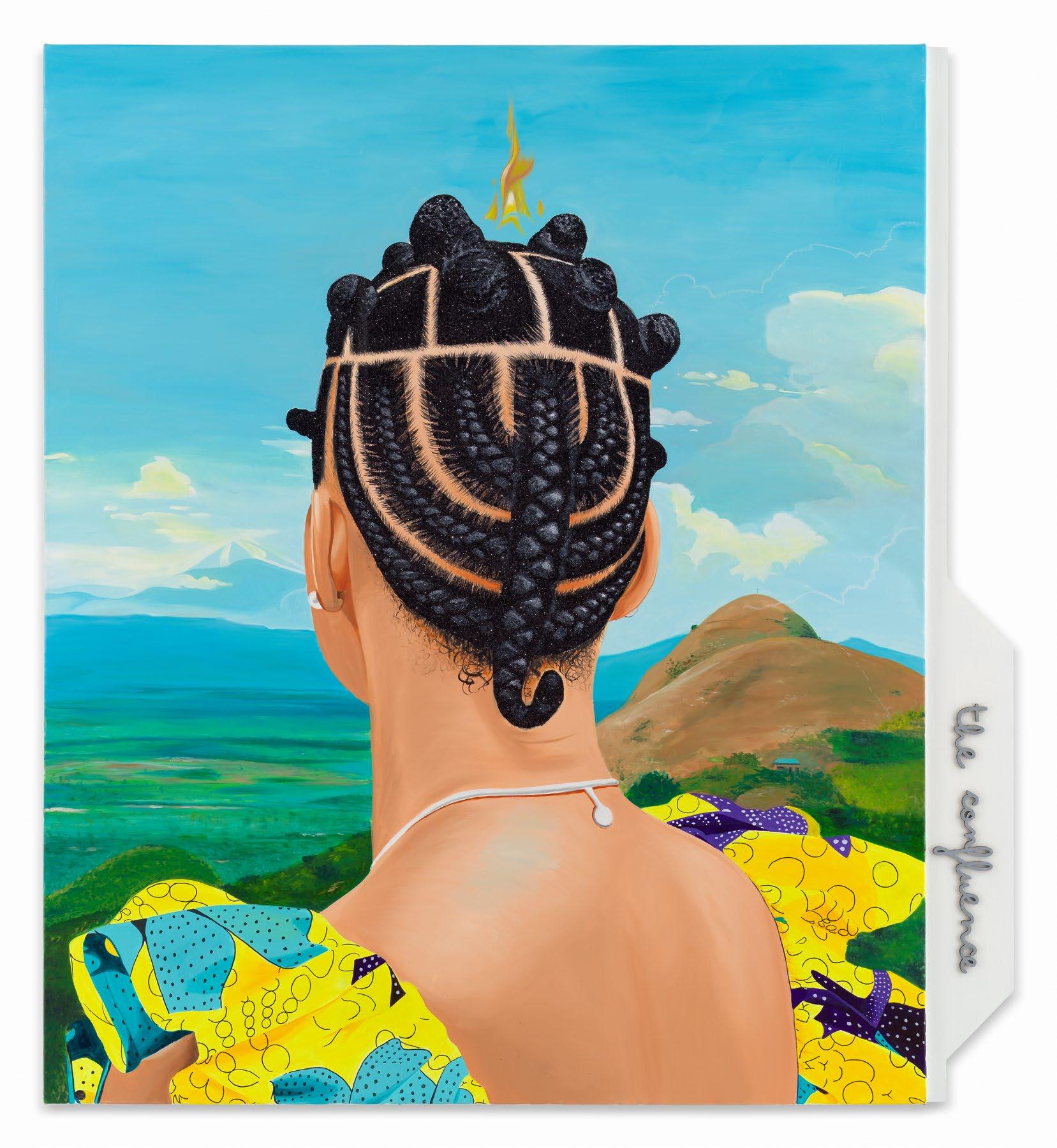

migration and displacement come into play? In Menorah’s Volta: A Light That Speaks (2023), Egyir creates a hybrid space between the United States and Ghana; the canvas depicts his wife, close up from the back, as she looks out at two topographically different mountain ranges—one in America, the other in Africa—while a flame flickers above her head, decorating the sky. Like a Menorah, the light continues to shine in the work, fusing two territories together in another play on identity, reinforcing the idea that a person may feel in equal measure displaced and entirely at home.

Then there’s Prevailing Psalms That Sway Familiar Victories (2024), which features three versions of the same subject—based on the artist’s friend Joshua Rainer, a current Cranbrook painting student—dressed in robin’s egg blue coats, pants, and matching black shoes. The staircase and piano in the background were present during the initial shoot on which the work is based— yet the painting is spiritual and ethereal in nature: a celebration of Black church culture, a blend of indoor and outdoor spaces, and an homage to the hymns and music involved. Two arrows are planted firmly by the subjects’ feet, an acknowledgment of the victories their devotion may bring; the artist calls them a “war for multiple forces.” The work is an exercise in pain and joy, in celebration and disappointment, and the pastel sky in the background showcases the subjects’ internal fellowship. Here, too, the land that surrounds them is grounding—and the space they inhabit is quickly overtaken by nature. In Jubilant Pastures is a testament to the artist’s history, his surrealist capabilities, and his technical expertise—juxtaposed against the double consciousness of his Ghanaian roots and American citizenship, and the fact that he has found his home in both places.

Charles Moore is a New York-based art critic and curator, holding a master’s degree from Harvard University and is currently a doctorate candidate at Columbia University. As a writer, he has authored books on art collecting, written critical reviews of exhibitions, and engages in dialogues with artists. As a curator, his work explores themes such as color theory, Abstract Expressionism, sociology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. His contributions to the art world have been recognized globally, with his work translated into over a dozen languages.

72 x 66 inches

183 x 168 cm

72 x 66 inches

183 x 168 cm

72 x 66 inches

183 x 168 cm

60 x 132 inches

152 x 335 cm

78 x 60 inches

198 x 152 cm

Milk, Honey, and Refuge, 2024

Oil, acrylic, and mounted wood on canvas

77 x 60 inches

198 x 152 cm

Prevailing Psalms That Sway Familiar Victories, 2024

78 x 60 inches

198 x 152 cm

Daughter’s Flight, 2024

Oil, acrylic, and glitter on canvas

20 1/2 x 18 inches

52 x 46 cm

20 1/2 x 18 inches

52 x 46 cm

20 1/2 x 18 inches

52 x 46 cm

Permeating Light, 2024

20 1/2 x 18 inches

52 x 46 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

5 September – 26 October 2024

Miles McEnery Gallery 520 West 21st Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2024 Miles McEnery Gallery All rights reserved

Essay © 2024 Charles Moore

Photo Credits:

p. 4: © Kehinde Wiley p. 4: © Tate, Photo: Tate

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY Tim Johnson, Detroit, MI

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-3529-1

Cover: Menorah’s Volta: A light that speaks,(detail), 2023