DANIEL RICH

511 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011 515 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

525 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011 520 West 21st Street New York NY 10011

“When fake news is repeated, it becomes difficult for the public to discern what’s real”

Jimmy

Gomez, assemblyman of Los Angeles1“Perspective was, after all, the science of the real, not the mode of withdrawal from it”

Rosalind Krauss2

In twenty-first century America, the street is loaded with meaning. It is a fraught site where history and politics are made and remade, written and rewritten—as people and law enforcement meet, and as freedoms are explored, denied, and protested.

In the last three years alone, it has become a present and recurring home of a democratic ideal in the public imagination—a consistent, public space where individual and collective grievances on both sides of the political spectrum have been aired as thousands of people have marched, week after week. Marched for George Floyd, for Breonna Taylor, for Black lives, for women’s reproductive rights, for the use of vaccines or the denial of their efficacy, and even to overturn Joe Biden’s election as president of the United States.

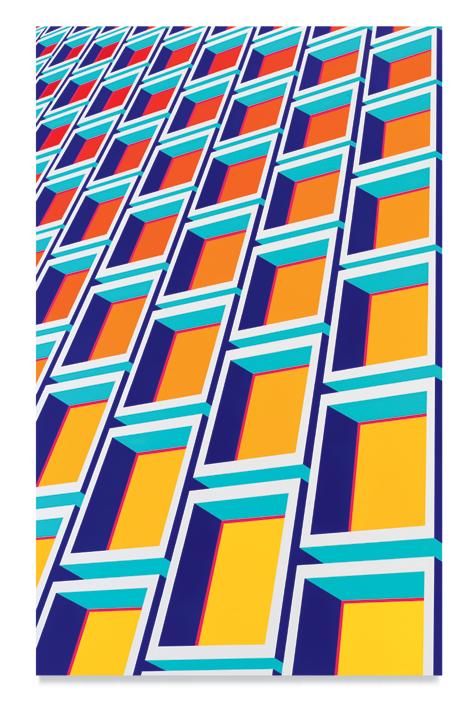

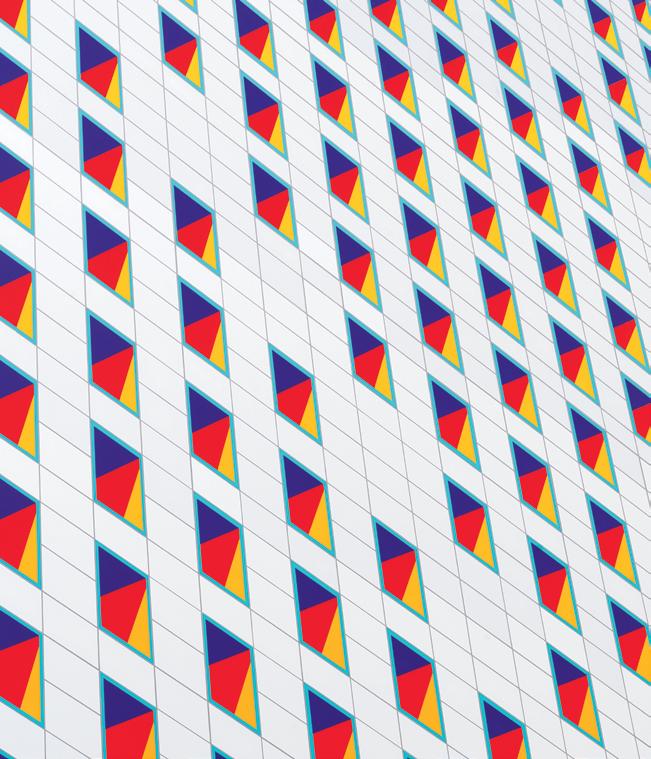

It is within this context of the streets being claimed and reclaimed that Daniel Rich began, in autumn 2021, the Flat Earth series. This new body of work consists of twelve paintings in highly saturated colors that meticulously show, from the viewpoint of the street, oblique angles of modernist buildings in midtown Manhattan. Titled after a specific address, each painting seems convincingly real, as a sense of perspective draws the eye into space, as though we are seeing a representation of the semi-abstract exterior structure of, for example, 531 Madison Avenue or 29 East 46th Street as it appears in life. The paintings are heavily cropped—we never see a

1. Alan Yuhas, “California Lawmakers Propose Bill to Teach Students to Identify ‘Fake News,’” The Guardian, January 12, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jan/12/california-lawmakers-propose-bills-toteach-students-to-identify-fake-news

2. Rosalind E. Krauss, The Originality of the Avant Garde and other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1985), p. 10 https://monoskop.org/images/1/1f/Krauss_Rosalind_E_1979_1985_Grids.pdf

full view from bottom to top, but instead are presented with a sharp corner, as in 29 East 46th Street; a section of skyscraper with edge-to-edge material, as in 789813 10th Avenue; or a series of repeated window panes that recess into the distance, as in 780 3rd Avenue. Windows and reflective glass abound in these works. The street is being watched and viewed, and the buildings bear witness.

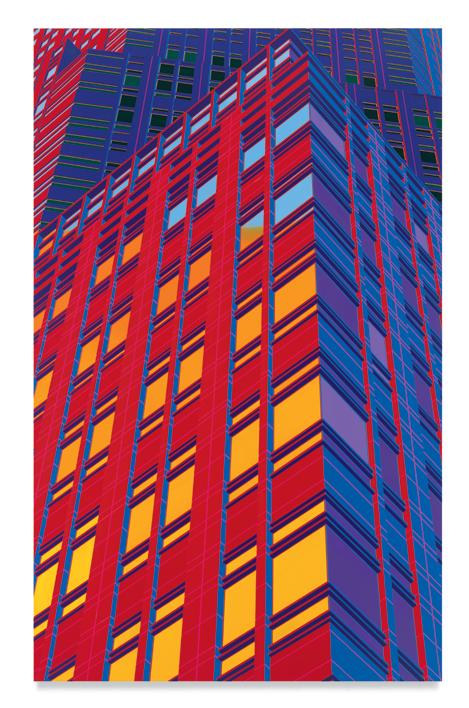

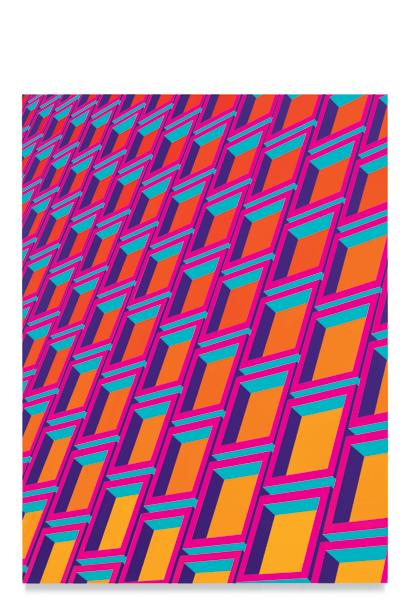

There is a double gaze at play. Just as there is a sense that the buildings see the events on the street below, so too are we looking up at the buildings. As viewers, we are asked to occupy the position of a protestor, someone on the street who is showing up for a cause we believe in—a cause worthy of our bodies, worthy of us taking up space and showing others “I am here.” The first time I saw these paintings, particularly 531 Madison Avenue, with its orange and yellow windows, as though reflecting the street below ablaze, I remembered all of the conflicting emotions that came with marching in a city, in my case, London. The challenge is to go to that emotional place—to see the architecture from a position of indignation and vulnerability, of powerlessness and power, of rage and hope. Rich invokes the potential productivity of these emotions in Zeitenwende—both the title of paintings in the exhibition, and a concept that he says governs the conceptual underpinning of this exhibition.3 Meaning “turning point” or “watershed moment” in German, the phrase suggests a potential for a pivot, the hope that something can—and will—change.

Over the past two decades, Rich has investigated the ways in which architecture might suggest underlying political narratives, turning his attention to the ways in which buildings are significant not for their design, but because of how they have been used and the events that have taken place within or in front of them. Previous work referenced specific historical, political and socially significant events based on appropriated imagery of architecture sourced online and from social media. The Flat Earth works mark a new departure for Rich. They share with previous work an insistence on line, color, structure, and the organization and creation of both flat and three-dimensional space, but they are original in his oeuvre, as they are, in his words, “sci-fi vision[s] of pictorial architecture.”4 They are sci-fi in part because Rich used Google Street View to generate the images for these paintings, mining its bank of

3. Daniel Rich in an email to the author, June 5, 2022.

4. Daniel Rich in an email to the author, June 5, 2022.

anonymously captured images, but also because there is a timelessness and ubiquity embedded in these images that attest to the apparent endurance, permanence, and uniformity of our built environment and, by implication, protest. Looking at the pristine surface of 789-813 10th Avenue, for example, time is suspended. We could well be viewing the building when it was first constructed in 1964, or today, or in a projected future. Likewise, because of what Ara H. Merjian has referred to as the “anonymity of the imagery,” this building could potentially be part of New York, or of any developed city globally; protest is a global phenomenon.5

Yet, to speak of this work conceptually as emerging from and hinting toward a very real political situation—as I have done so far—is to discount how we see, what we see, and what painting can do that language cannot. Language, when used descriptively, gives us images—ideas in our heads that we can conjure into pictures. Paintings, far more mysterious and ineffable, can give us images and something else: paint itself. The “stuff” of it all. In an interview with the art historian David Sylvester in 1960, the American painter Philip Guston (one of the most sensitive and adept political commentators of the twentieth century) reflected on this push and pull of paint—its status as both an image-maker and image-refuser on the surface of the canvas. Guston talked about the “matter” of paint having a certain resistance on a picture plane: “Without this resistance, you would just vanish into either meaning or clarity, and who wants to vanish into clarity or meaning?… Most great paintings have this duality between the forms of the surface and the forms in depth.”6

Rich thinks primarily in color, shape, and line that intersect and overlap to create structure, and his work hinges on this tension between the forms of the surface and the forms in depth that Guston describes. In the Flat Earth paintings, he masterfully creates images with a sense of three-dimensional space, while simultaneously frustrating that space and denying there are more than two dimensions on a picture plane. Flat earth, indeed.

This tension comes to a head in one of three paintings of interiors in the exhibition, a self-reflexive painting Homage to Sol LeWitt, in which Rich paints the fictitious, gridded

5. Ara H. Merjian, “Daniel Rich,” in Daniel Rich: Back to the Future (New York: Miles McEnery Gallery, 2021), p. 2

6. “Interview with David Sylvester, 1960” in Philip Guston, I Paint What I Want to See (London: Penguin Classics, 2022), p. 4

space of a Sol LeWitt wall drawing as installed in a real space—the interior of the Williams College Museum of Art. There’s a double take as we realize that Rich is painting Sol LeWitt’s illusory, three-dimensional space on a two- dimensional surface (the painting on a wall), which exists in a real 3D architectural space (of the museum staircase), rendered flat, illusory, and abstract again on the surface of the canvas.

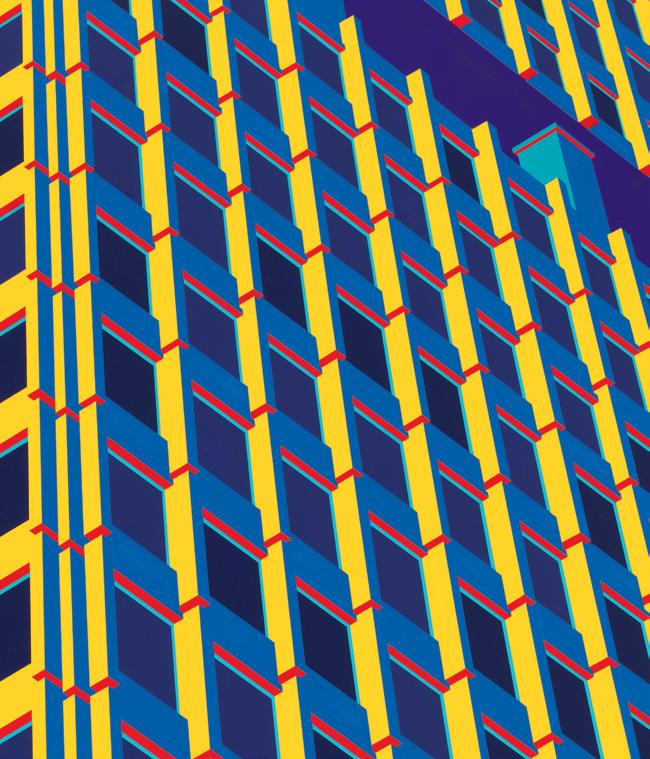

This work throws the whole show into disarray, and we are prompted to question whether the buildings and interiors in the rest of the show are “real” or whether they are, in fact, imagined, fictitious spaces where information and misinformation overlap. Take 780 3rd Avenue, for example, an M.C. Escher-like image of a series of window perforations in the facade that seemingly repeat ad-infinitum beyond the edges of the canvas. Here, the illusion of space is suggested by perspectival lines that draw the eye diagonally from the bottom left corner of the canvas to the top right. Yet, on closer inspection, all is not as it seems, and the “real” becomes harder to grasp as color and distortion work their magic. The blue, red, and yellow of the window perforations simultaneously suggest space, while the solidness of the color blocks it and renders it flat. Look closely at the upper right-hand corner of the picture, and you’ll see that the perspective—the “science of the real” as Rosalind Krauss calls it—is off. The upper right-hand corner is overly stretched. Across the series, Rich used photoshop to manipulate the Google Street View images, warping their corners, producing a feeling of disorientation as some buildings tweak upward, while others seem to slide downward.

This tension between real and artifice, two seemingly conflicting ideas, is at the heart of Rich’s work. His paintings are at once illusions of real places and abstract surfaces, flat and three-dimensional, strange and familiar. This is their subtle, political power as paintings, as “matter” on canvas: The images put the viewer in the position of protestor at the same time that pictorial devices of saturated color and distortion get us to question what is real and what is fake—essentially, thrusting us into a condition of unknowing that is so indicative of our current political moment, in which information and misinformation are widely spread. Jimmy Gomez, an assemblyman of Los Angeles described it clearly: When fake news is repeated, it becomes difficult for the public to discern what’s real.

Julie Mehretu, Transcending: The New International, 2003 Ink and acrylic on canvas, 107 × 237 inches (271.78 × 601.98 cm). Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis T.B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 2003. Photograph courtesy Walker Art Center © Julie Mehretu

In preparing to make these works, Rich turned to other painters he admired, among them Mark Bradford and Julie Mehretu, who also masterfully wield abstraction to create political images. But so often this political tendency in abstraction rests on imagery or supporting text to illuminate what these paintings are about—as though a documentary photograph or specific historical moment might unlock the narrative of the work. The unique beauty of Daniel Rich’s work is that it doesn’t need it—you can take the paintings at surface value for what they are—images suggesting surveillance, protest, and that something may be at a turning point; and painted surfaces that disorient and make the familiar strange.7

In referring to the artifice of painting while invoking real-life politics, the Flat Earth paintings operate as clever devices in which life and art map onto one another and become self-referential. Life, like painting, these works suggest, is a series of constructions in which there is no truth. Both are, after all, a matter of perspective.

Wells

7. Calvin Tomkins describes this tendency best when writing about the work of Ed Ruscha, who similarly plays with flat surfaces, panes of flat color and an oscillation between two-dimensional and threedimensional space in his scenes of Los Angeles: “This is not the kind of picture that reveals hidden depths on subsequent viewings. Everything is right there, every time, and it never fails to make me feel good.” In Calvin Tomkins, “Ed Ruscha’s LA,” The New Yorker, June 24, 2013.

8

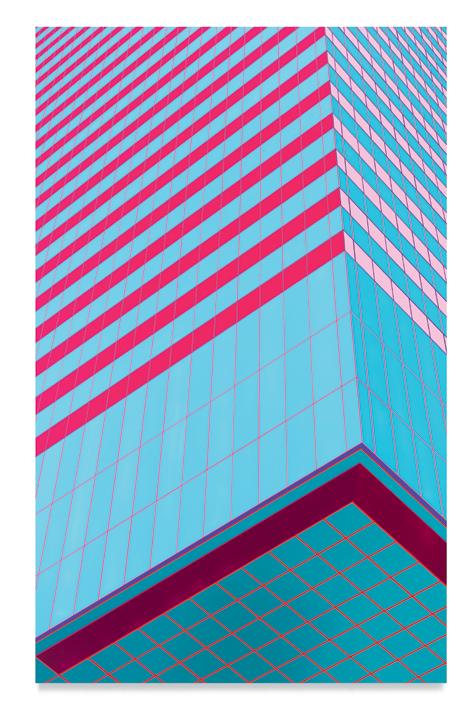

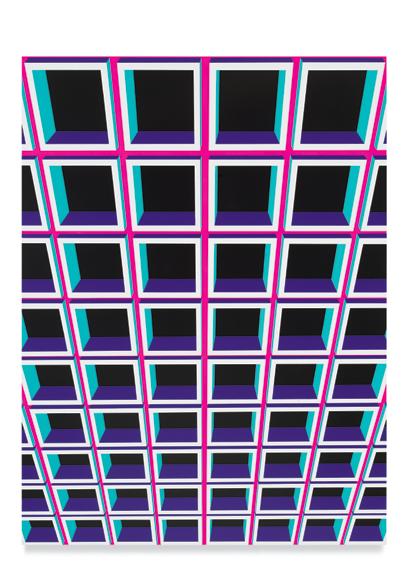

200 Park Ave, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

80 x 50 inches

203.2 x 127 cm

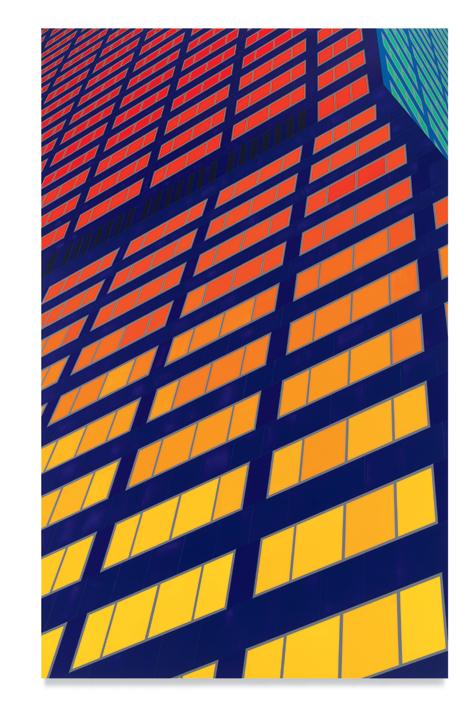

10

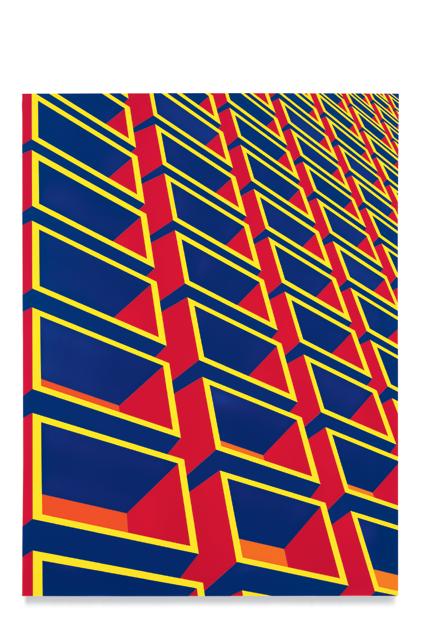

29 East 46th St, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

80 x 50 inches

203.2 x 127 cm

12

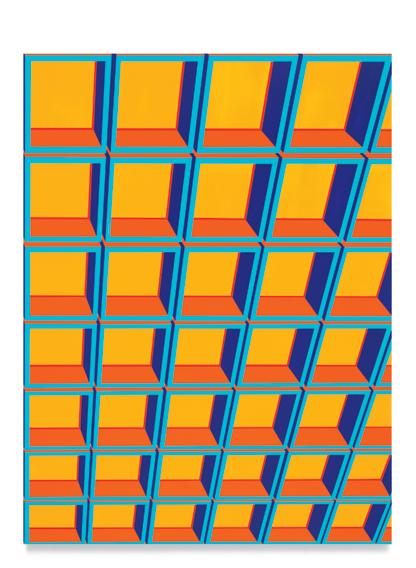

531 Madison Ave, 2022

Acrylic on dibond 80 x 50 inches 203.2 x 127 cm

14

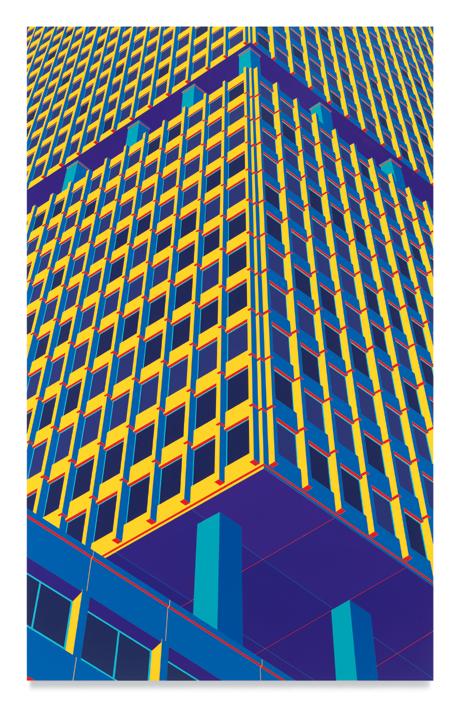

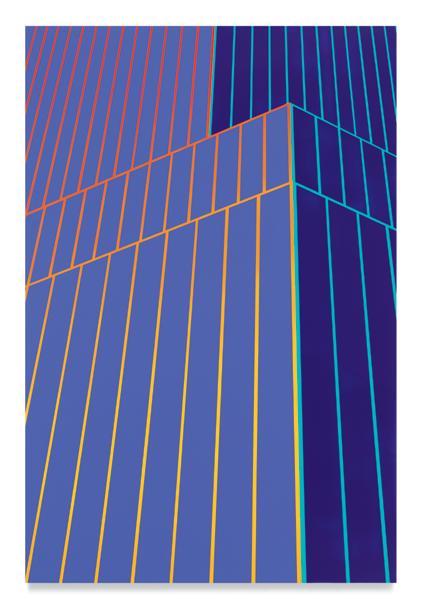

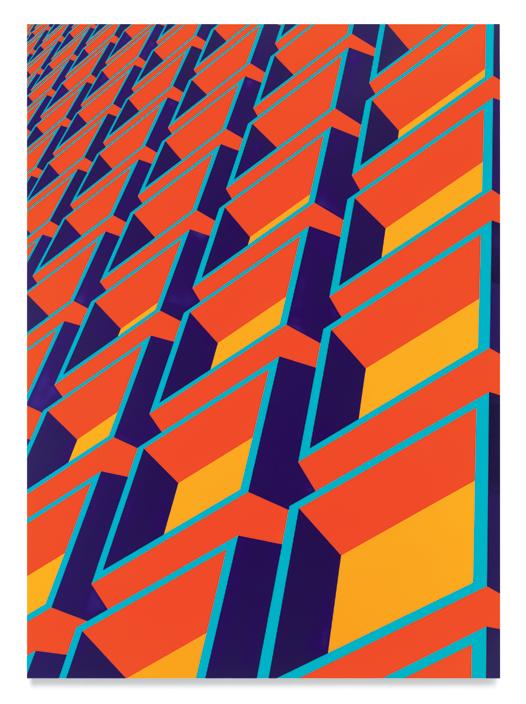

601 Lexington Ave, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

80 x 50 inches

203.2 x 127 cm

16

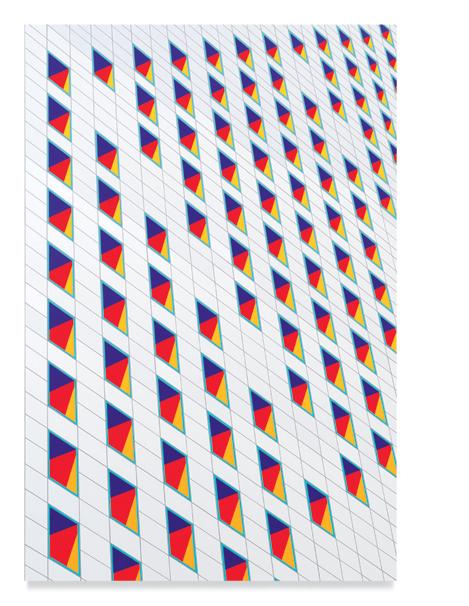

780 3rd Ave, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

60 x 40 inches

152.4 x 101.6 cm

18

789-813 10th Avenue, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

60 x 40 inches

152.4 x 101.6 cm

909 3rd Ave, Interior, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

40 x 30 inches

101.6 x 76.2 cm

945 Madison Ave, Interior, 2022

Acrylic on dibond

40 x 30 inches

101.6 x 76.2 cm

Zeitenwende #1, 2022 Acrylic on dibond 40 x 30 inches 101.6 x 76.2 cm

26

Zeitenwende #2, 2022 Acrylic on dibond 40 x 30 inches 101.6 x 76.2 cm

Zeitenwende #3 / 909 3rd Ave, 2022

Acrylic on dibond 83 x 60 inches

210.8 x 152.4 cm

Zeitenwende #4, 2022 Acrylic on dibond 80 x 50 inches 203.2 x 127 cm

Born in Ulm, Germany in 1977

Lives and works in Berlin, Germany and Blowing Rock, NC

2004

Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME MFA, Tufts University, Medford, MA and School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA 2001 BFA, Atlanta College of Art, Atlanta, GA

2022

“Flat Earth,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY 2020

“(co)vertex,” Studio Trouble, Berlin, Germany “Back to the Future,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY 2018

“Never Forever,” Peter Blum Gallery, New York, NY 2014

“Systematic Anarchy,” Peter Blum Gallery, New York, NY 2012

“Platforms of Power,” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA 2010

“Berlin: Daniel Rich and Wieland Speck,” Horton Gallery, New York, NY 2009

“1989–2009: Paintings of the Berlin Airports 20 Years after the Fall of the Wall,” Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Chicago, IL 2008

“Downburst,” Perry Rubenstein Gallery, New York, NY

2007

“Black Sunday,” SUNDAY, New York, NY “Baghdad,” Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, MA 2006

“Torre Velasca,” Mario Diacono Gallery, Boston, MA 2005

“Project Space,” Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, NY

2022

“Otherworldly,” Mucciaccia Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2021

“Studio Visit,” Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, Italy Weber Fine Art, Greenwich, CT

“Beyond the Streets on Paper,” Southampton Arts Center, Southampton, NY

2020

“Endless State,” The Skowhegan Alliance, New York, NY 2019

“Mensch in Moll,” Inter Port, Berlin, Germany “Geometric Heat,” GR Gallery, New York, NY “Invisibli,” Anna Marra Contemporanea, Rome, Italy “Set for the Sun” (curated by Jenne Grabowski), Lobe Block, Berlin, Germany “#” (curated by Markus Linnenbrink), Cindy Rucker Gallery, New York, NY

2018

“In My Room: Artists Paint the Interior 1950-Now,” Fralin Museum of Art, The University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA

2017

“After the Fall,” Peter Blum Gallery, New York, NY “Urbanopolis,” Galerie LJ, Paris, France

2016

“Postcard from New York,” Anna Marra Contemporanea, Rome, Italy

“Summer Group Show,” Joshua Liner Gallery, New York, NY

2015

“On a Boat, Looking to Land: Gil Heitor Cortesao & Daniel Rich,” Carbon 12, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

2014

“Résonance(s),” Maison Particulière, Brussels, Belgium “Epic Fail 2,” Active Space, New York, NY

2013

“October 18, 1977” (curated by Birgit Rathsmann), Gasser Grunert Gallery, New York, NY

2012

“Summer Group Show,” Joshua Liner Gallery, New York, NY “Divergence,” Lower East Side Printshop, New York, NY

2011

“LANY” (curated by Mario Diacono), Peter Blum Gallery, New York, NY “Chainletter,” Golden Parachute, Berlin/Samson Projects, Boston, MA

2009

“Rattled by the Rush,” Andrew Rafacz Gallery, Chicago, IL “Slow Photography,” Sunday LES, New York, NY “Transitions-Painting at the (other) end of art,” Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, Italy

2008

“Supernova,” Art Basel Miami Beach, Miami Beach, FL “A Sorry Kind Of Wisdom,” Perry Rubenstein Gallery, New York, NY

2006

“Material Matters,” Maryland Art Place, Baltimore, MD “We Build the Worlds Inside Our Heads,” Freight + Volume, New York, NY

2005

Elizabeth Dee Gallery, New York, NY “Skowhegan Projects,” Skowhegan State Fair, Skowhegan, ME

2004

“Combined Talent,” Tallahassee Museum of Fine Art, Tallahassee, FL “Summer Distillation,” Miller Block Gallery, Boston, MA “Site Specifics,” ArtSpace, Malden, MA “The Sublime is (still) now” (curated by Joe Wolin), Elizabeth Dee Gallery New York, NY “Axiom,” Gallery 4, Baltimore, MD “Constellations,” Tufts University, Medford, MA

2003

“Properties,” The H. Lewis Gallery, Baltimore, MD “CGR Advisors & Dragon Foundation Scholarship Recipients,” Museum of Contemporary Art, Atlanta, GA “Referencing Perspective,” Gallery 100, Atlanta, GA “Deconstruction and Recomposition,” The Art Farm, Atlanta, GA

2017

Print Residency, Lower East Side Printshop, New York, NY

2015

Traveling Scholars Grant, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

2012

Painting Fellow, New York Foundation for the Arts, New York, NY

2011

Keyholder Residency Award, Lower East Side Printshop, New York, NY

2010

Marie Walsh Sharpe, The Space Program, New York, NY Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, Omaha, NE

2004

Full Fellowship, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME

Travel Grant, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

2001

Graduate Fellowship, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Ben Shute Scholarship for Excellence in Representational Art, Atlanta College Art, Atlanta, GA

Dragon Foundation Scholarship, Atlanta College of Art, Atlanta, GA

Cornell Museum at Rollins University, Winter Park, FL

Fidelity Art Collection, Boston, MA

Hudson Valley Museum of Contemporary Art, Peekskill, NY

Maramotti Collection, Reggio Emilia, Italy

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA

Wellington Management, Boston, MA

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

8 December 2022 – 28 January 2023

Miles McEnery Gallery 525 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2022 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved Essay © 2022 Wells Fray-Smith

Director of Exhibitions Anastasija Jevtovic, New York, NY

Photography by Christopher Burke Studio, New York, NY

Color separations by Echelon, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue designed by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 978-1-949327-92-2

Cover: 29 East 46th St, (detail), 2022