Fiona Rae

A few years ago, I was in the studio as usual and I was bored. I’ve been a full-time painter ever since I left art college, which is now exactly 37 years ago and a very long time indeed to sustain an interest in anything, let alone something that entails long solitary hours in a studio with no view in London’s East End.

So I’ve kept myself interested for decades by periodically changing the rules — the conceptual strategies — for the paintings, and thereby I’ve ended up working in series. Sometimes a series will last barely a year; sometimes it will last several years. And in 2021, I’d come to the end of a series, and I was bored, which is always how I know that it’s over. In desperation, I sprawled the words “I can’t do this, NO, NO” onto a canvas that I was trying to conjure into life. It was messy and unresolved and not a painting that could be allowed to go out into the world. But this disruptive act gave me an idea for my new paintings, the Word series.

I began my professional painting life in the late ’80s with the Row series, in which multiple cells of brush marks played across canvases, acting as prototype words in my own idiolect, a gnomic abstract language. And over the decades, I’ve sometimes inserted a word or sentence into a painting, whether heavily disguised under an abstract moustache or picked out in legible letters and added as a legitimate painting element to sit alongside all the other legitimate painting elements. I’ve also used letters and signs from contemporary fonts as compositional starting points for paintings, bouncing paint marks off their presence as geometric or abstract shapes, whilst simultaneously delighting in their role as interlopers throwing welcome spanners into the works of abstraction.

My idea for the Word series is that each painting embodies a sentence or quote. There is no intention to illustrate the meaning or emotion of the particular sentence; instead, the languages of abstraction and literature twist around each other and, I hope, give rise to new and unexpected images and meaning. I have a long-standing interest in the skirmish between intelligibility and ambiguity; language is mutable, not literal, barely holding back the chaos even though it is our opportunity to understand each other and make sense of the world. Indeed, as Krazy Kat said so wisely, “Lenguage is that we may mis-unda-stend each udda.”1

The act of painting is a gesture, a shape that the body makes when standing before a canvas in order to make a mark. So an abstract painting documents a physical dance or set of movements in space, resulting in footprints of language and form. I intend the painterly constructions in these new paintings not only to present abstract propositions, but also to articulate letters and words, with every part of the painting “emitting language,”2 to borrow Roger Hiorns’s description of his foaming sculptures. The pieces of painting are alive, the paint crawls and shifts, brush marks prop each other up as if they are 3-D sculptures, bits of background white lose their place in the plot and move to the foreground, interrupting carefully constructed multicoloured brush marks. The language in the paintings, both the abstract paint language and the literal word language, is nudged and jostled by whatever is next to it, and what’s behind it and what’s on top of it — let alone what’s hiding underneath it. Everything is contiguous and contextual and provisional, which is how I find the world to be…

Each word is a little depth-charge of meaning and associations; even letters carry their own handbags and histories, as do paint marks and shapes that trail art history like phosphorescence. So the dialectic of running these two language systems alongside each other leads to a third set of possibilities, and if we’re jolly lucky, the emergence of something not previously known…

1 George Herriman, “Krazy Kat,” King Features Syndicate, January 6, 1918. The comic strip, which ran from 1913 to 1944, was a favorite of intellectuals, artists, and art critics.

2 Roger Hiorns, From Art School to Artist, Christie’s video, 2015.

When I started university, I thought I loved English literature enough to do a degree in it. Unfortunately, I quickly realised that I could not sit through another lecture on Milton’s syntax, brilliant though it was, so I dropped out in order to go to art college. However, I was left with an abiding love of 16th and 17th century plays and poetry, Shakespeare and the Metaphysical poets in particular, and these still live in my thoughts to this day. There’s a lot of quiet in the studio; I don’t listen to the spoken word to help pass the time, and I barely listen to music. Instead, I listen to the voices in my head whilst I’m painting, and those voices remember lines from movies, cartoons, sonnets, pop songs, and books. So to choose a quote from literature or popular culture and to have it be the subject of a painting, while at the same time providing the internal soundtrack and the echoes in my mind, seems quite a tidy decision.

And before I forget, I also want to add something about my need to be irreverent and to undermine and challenge existing agreements about how things should be done. It’s hard when you’re learning to paint to be told that there are things you should and shouldn’t do — and that here are the texts and writings to prove it. When a fellow Goldsmiths College student shouted at me from across the street that I shouldn’t be trying to make paintings, that the battles had already been fought and won by other art armies, it made me even more determined in my belief that there was still something of interest to be explored in painting. Besides which, I wasn’t being entirely high-minded in my wish to continue with this old-fashioned and out-of-fashion art form; by then I had discovered that I really loved painting on a canvas, searching for those slipping glimpses of magical outcomes.

I approach painting as a conceptual game and/or endgame with an overwhelmingly physical manifestation that usually gets in the way of theoretical ambition and makes the whole thing a much more likeable proposition to be around. Decades later, I still find that the more embarrassing and unacceptable my ideas seem to be to the orthodoxy, the closer the paintings flirt with tricky areas like decoration, fashion, greetings cards, computer games, cartoons — the whole shebang of popular culture — the more interesting the painting becomes to me and the more inclined I am to get up off the sofa and pick up a brush.

I can hope that the trajectory of my painting history is in a way a performance of Fischli and Weiss’s Der Lauf der Dinge (The Way Things Go), the seminal film released in 1987, the year that I graduated from art school. This film shows a series of absurd encounters and unexpected yet inevitable consequences, a simultaneously comic and serious entropy that unfolds at different speeds, the whole episodic journey being triggered by a decisive action. There’s no usage or point to any of the activity, nothing is to be gained or lost, and yet it’s a pleasurable and meaningful experience for the sympathetic viewer. As for my painting spirit, I still choose to ignore “I can’t do this, NO, NO” and instead look to Samuel Beckett, “you must go on, I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”3

3 Samuel Beckett, The Unnamable (London: Calder, 1959).

152.4

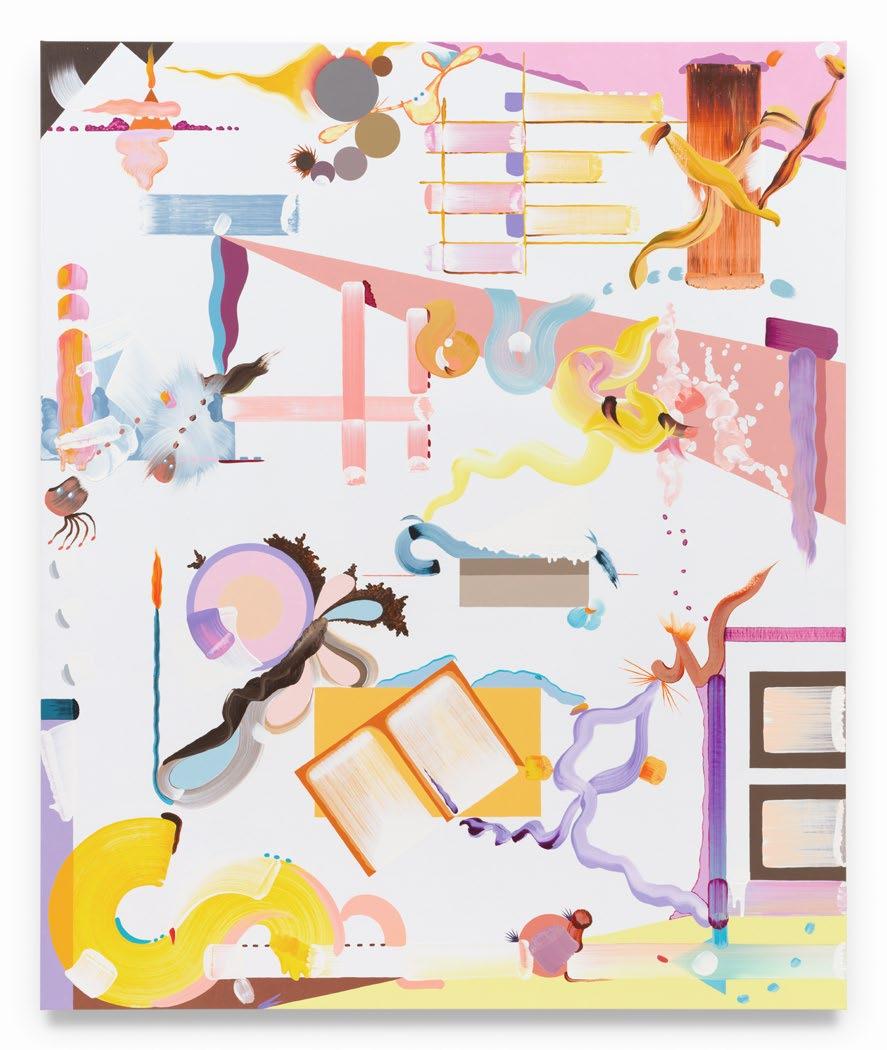

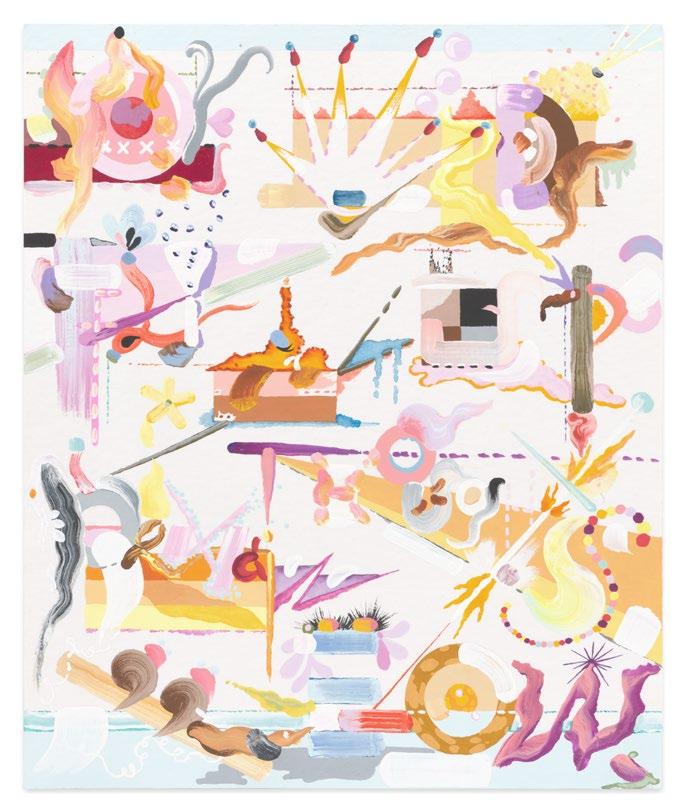

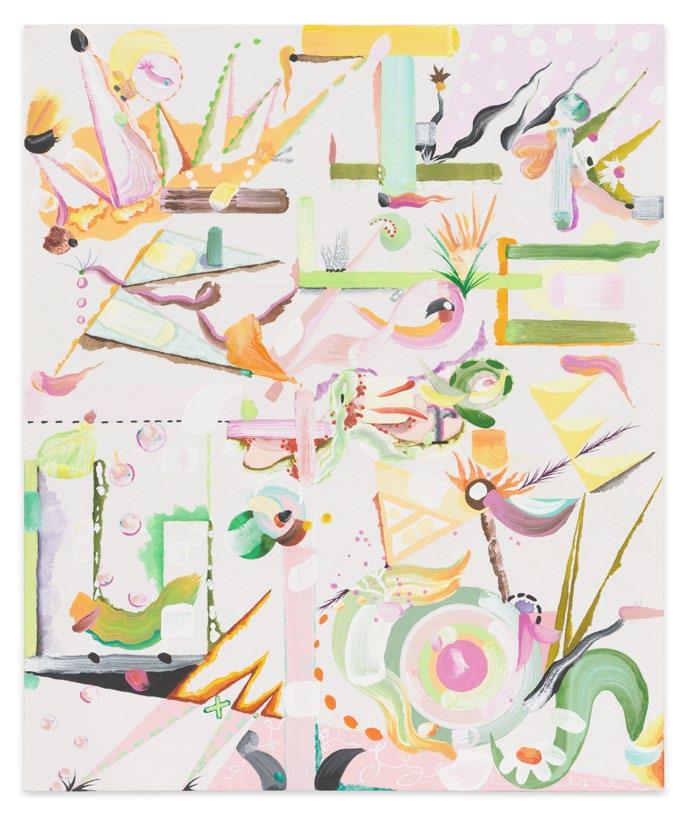

Teach me to hear mermaids singing, 2023

60 x 50 inches

152.4 x 127 cm

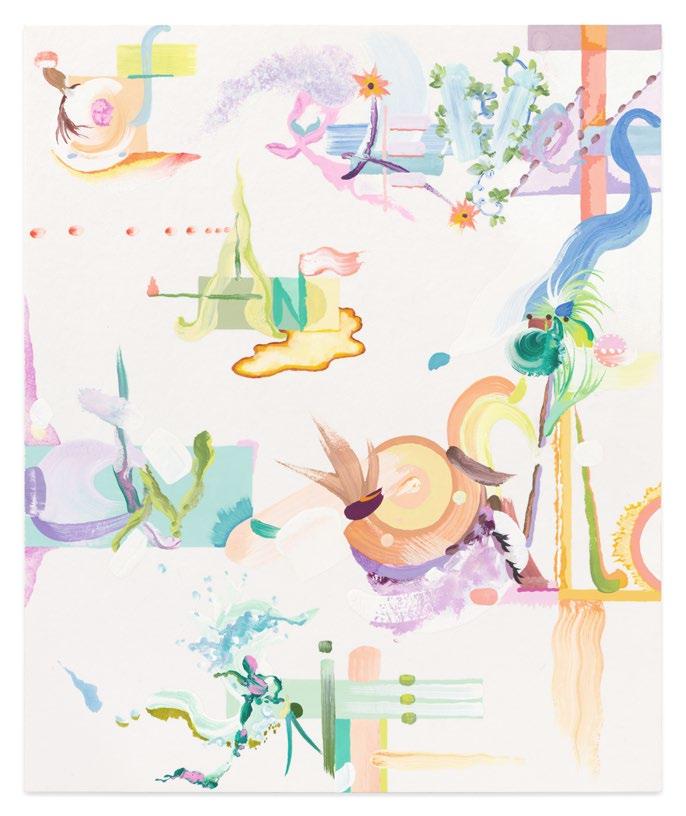

I am a little world made cunningly, 2024

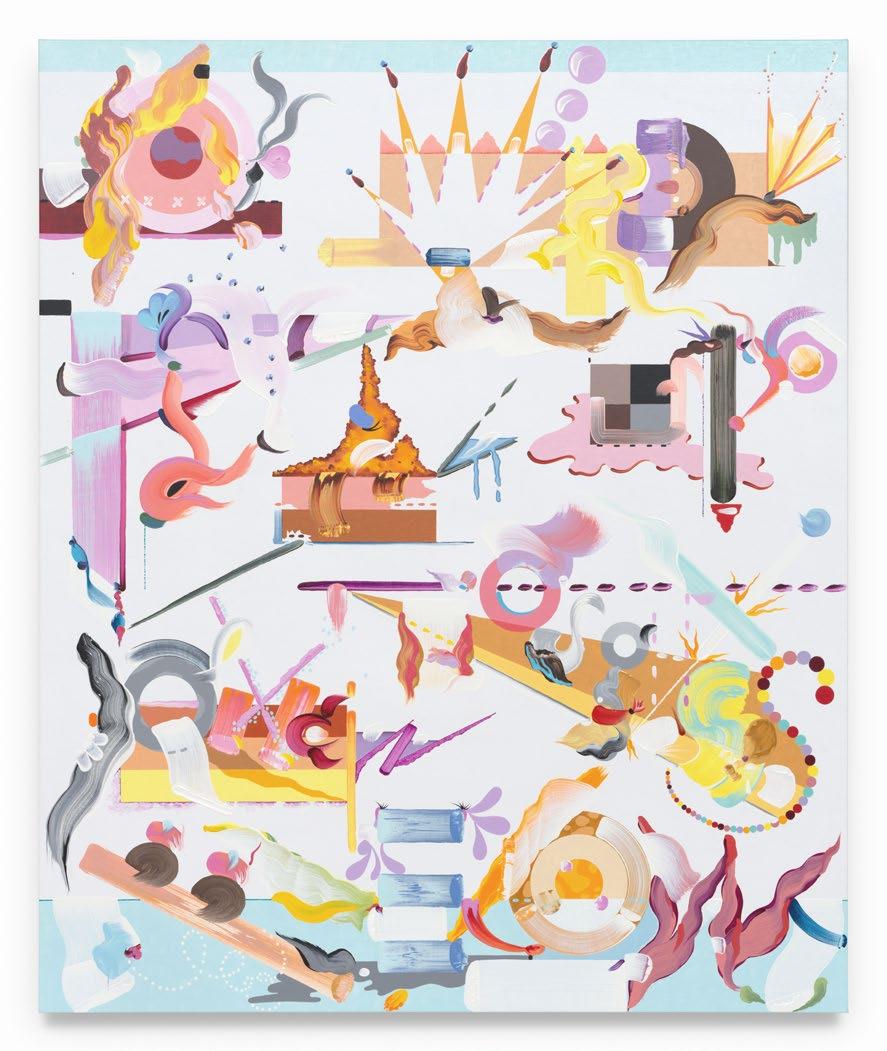

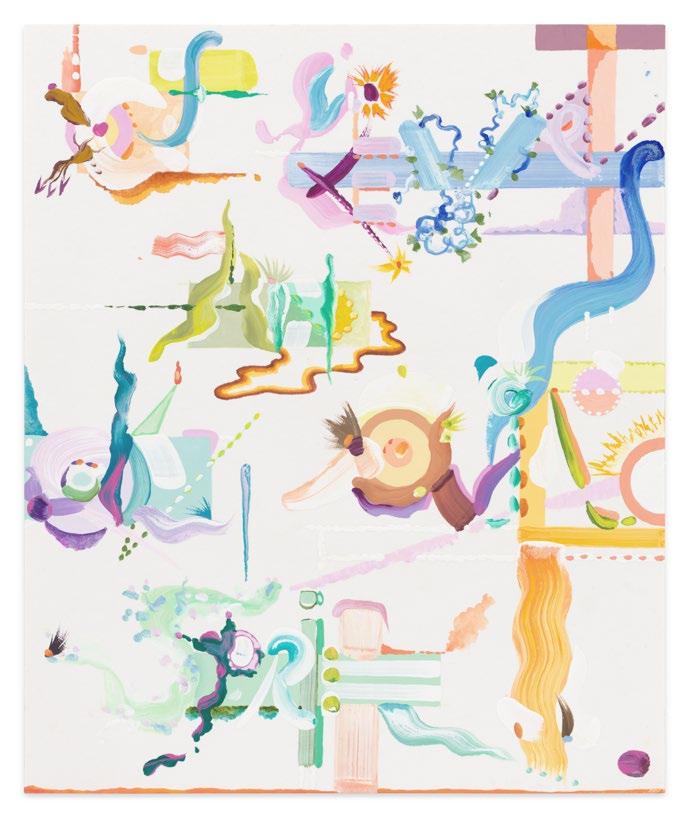

Like tears in rain... Time to die, 2024

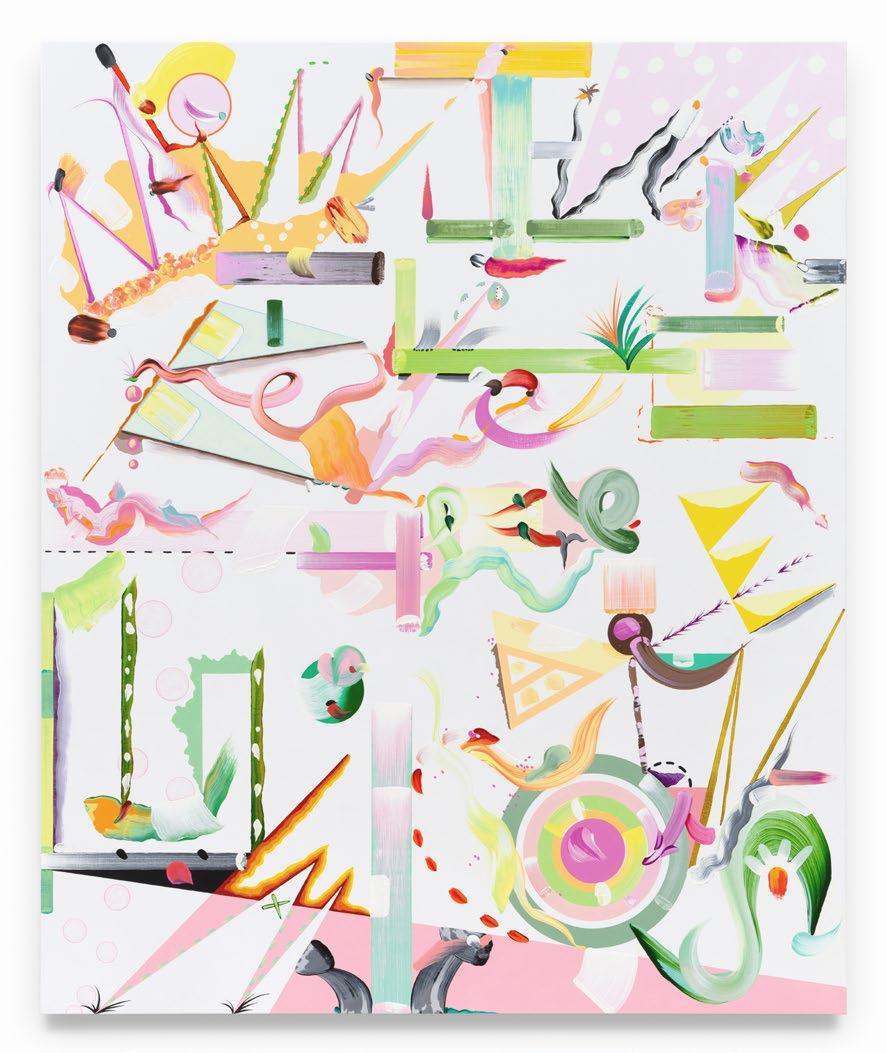

My words fly up, my thoughts remain below, 2024

Oil and acrylic on linen

60 x 50 inches

152.4 x 127 cm

Now I will believe there are unicorns..., 2024

Oil and acrylic on linen

60 x 50 inches

152.4 x 127 cm

elements and an angelic sprite, 2024

60 x 50 inches

152.4 x 127 cm

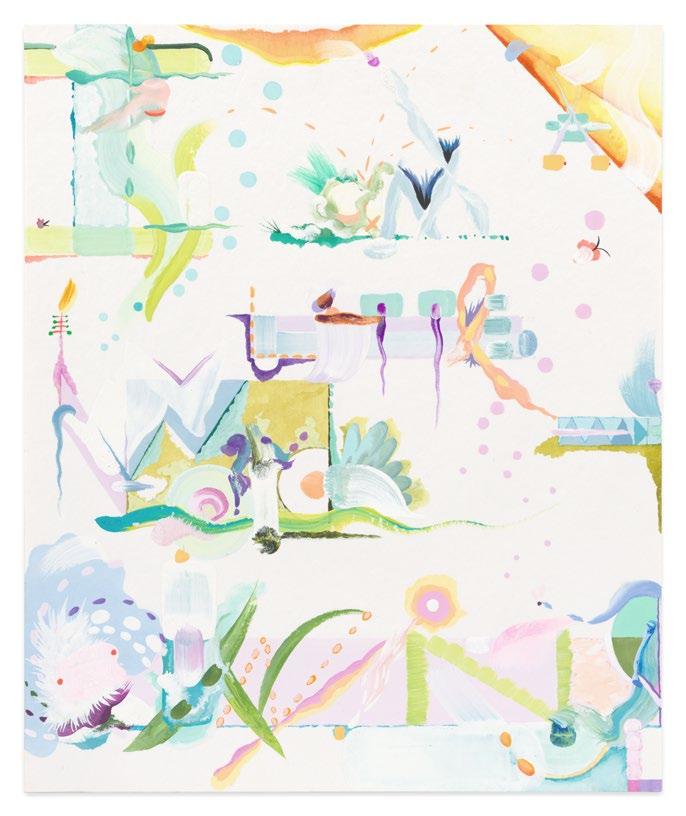

Drawing (I am a little world made cunningly), 2024

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

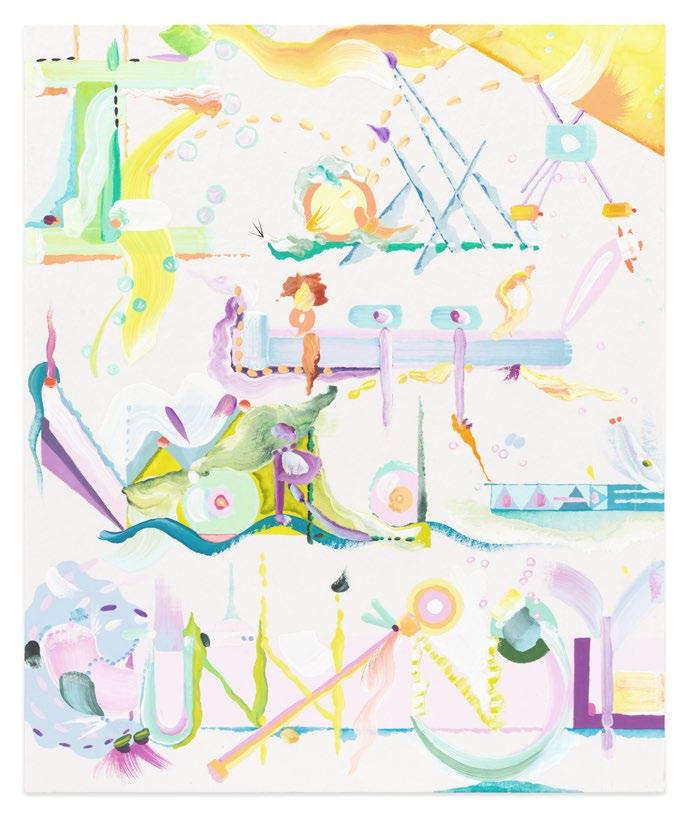

Drawing (I am a little world made cunningly 2), 2024

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

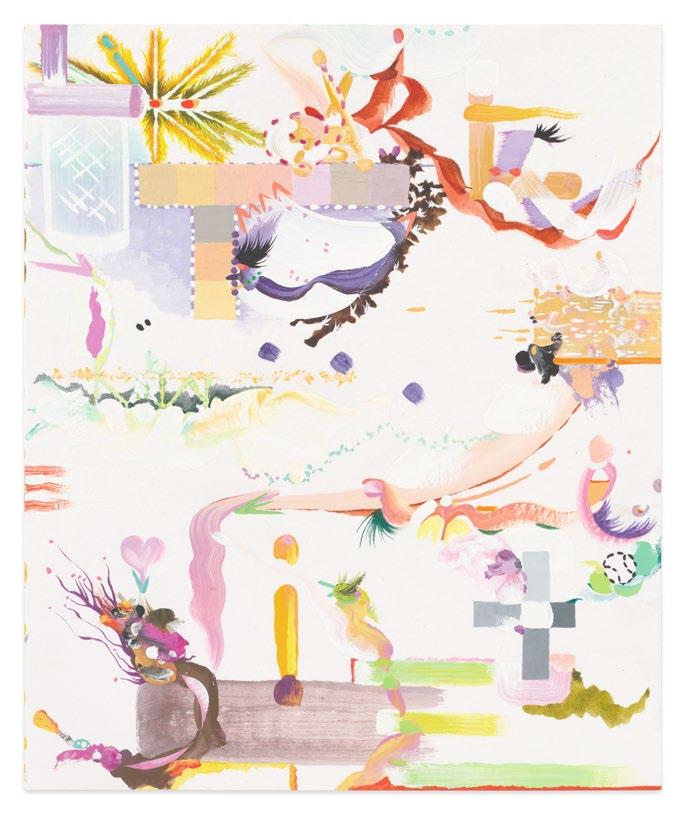

Drawing (like tears in rain... time to die), 2022

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Drawing (like tears in rain... time to die 2), 2023

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Drawing (like tears in rain... time to die 3), 2024

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Drawing (my words fly up, my thoughts remain below), 2024

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Drawing (my words fly up, my thoughts remain below 2), 2024

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Drawing (now I will believe there are unicorns...), 2024

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Drawing (of elements and an angelic sprite), 2023

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

(of elements and an angelic sprite 2), 2023

Watercolor and gouache on paper

11 3/4 x 9 7/8 inches

30 x 25 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

31 October - 7 December 2024

Miles McEnery Gallery 525 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2024 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2024 Fiona Rae All works © Fiona Rae

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-3876-6

Cover: Like tears in the rain... Time to die,(detail), 2024