MARKUS LINNENBRINK

An unnecessary necessity as well as a universal idea, beauty can pave the way toward understanding that we are participants of a larger world. In his decades-long career, Markus Linnenbrink is an artist who seeks to disrupt or transform our perceptions of beauty and provoke new ways of seeing and feeling. In our appreciation of beautiful things, we can find a connection to others and a path to embracing ideas about empathy and inclusivity.

Throughout history, beauty has been a central concern of art, and contemporary art is no exception. Since the late ’60s, art has challenged and expanded on this concept, with many artists exploring new forms of the aesthetic experience that may not conform to traditional interpretations of what is considered beautiful. In an abstract sense, philosophers describe beauty as the result of an internal reaction, an automated response that rebuts the survival instinct. In Critique of Judgment (1790), which deals with the nature of aesthetic understanding, Immanuel Kant says that the pleasure we take in beauty is ideally an “entirely disinterested satisfaction,” meaning that it is unlinked to our sensory or moral needs. Yet beauty satiates us in such a way that what we enjoy is not an object but a state of mind independent of lack.

Friedrich Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (1794) builds on Kant’s notion that aesthetic pleasure exists between the notions of pure nature and pure mind. He asserts that there are two things that drive humans: the “sensuous” or “physical,” which attends to basic needs, and the “formal,” which attends to intellectual needs. Unlike Kant, he argues that beauty is more objective and connects the two seemingly disparate ideations.

Beauty is a connected experience. It occurs when we find something that meets our unarticulated impulse. In Elaine Scarry’s seminal book On Beauty and Being Just, she argues:

Beauty brings copies of itself into being. It makes us draw it, take photographs of it, or describe it to other people. Sometimes it gives rise to exact replication and other times to resemblances and still other times to things whose connection to the original site of inspiration is unrecognizable.1

This is especially true in social media, where we are able to post and consume images of beautiful things found in nature (the external), in life (the internal), and in art (the bridge). This is one way people in contemporary society choose to keep in touch with old friends, make new connections, stay informed, and share.

The second half of Scarry’s book discusses “radical decentering,” the phenomena of letting go of solipsistic ideas and connecting to other views.

“Radical decentering might also be called an opiated adjacency. A beautiful thing is not the only thing in the world that can make us feel adjacent; nor is it the only thing in the world that brings a state of acute pleasure. But it appears to be one of the few phenomena in the world that brings about both simultaneously; it permits us to be adjacent while also permitting us to experience extreme pleasure, thereby creating the sense that it is our own adjacency that is pleasure-bearing.”2

EVERYTHINGBETWEENTHESUNANDTHEDIRT (2023) begins with an eponymous installation greeting its visitors with enthusiasm. As the entry point for the exhibition, Linnenbrink activates a space not usually designated for art. In his installations, Linnenbrink demonstrates his ability to respond to his surroundings and create an ad hoc art piece that begins with a blank space that builds itself into the exultant compositions that are his trademark.

Physically, Linnenbrink’s studio works are composed of epoxy resin, pigments, and simple supports that project themselves into our spaces on laminated wooden panels. While this list of materials is simple enough, the main component of Linnenbrink’s work is color. The artist gleefully creates entire rainbows of primary, secondary, and tertiary hues that are layered, hewed, and poured into compositions. He is adept at creating combinations of his uniquely mixed pigments, but also recognizes that “all interaction with color happens in and through the eye of the viewer. The same visual information then lands in receptors that are all molded by the whole life story of the individual that receives what is to be seen.”3

While Linnenbrink is not an artist who is about control, he is a disciplined conductor who considers his paintings from every angle and distance. Seeing a painting from afar should be just as satisfying as seeing it from a few feet away, up close, or, in the example of his monumental 90-ft composition HEARYOURNAMELIKELIGHTPASSINGBY

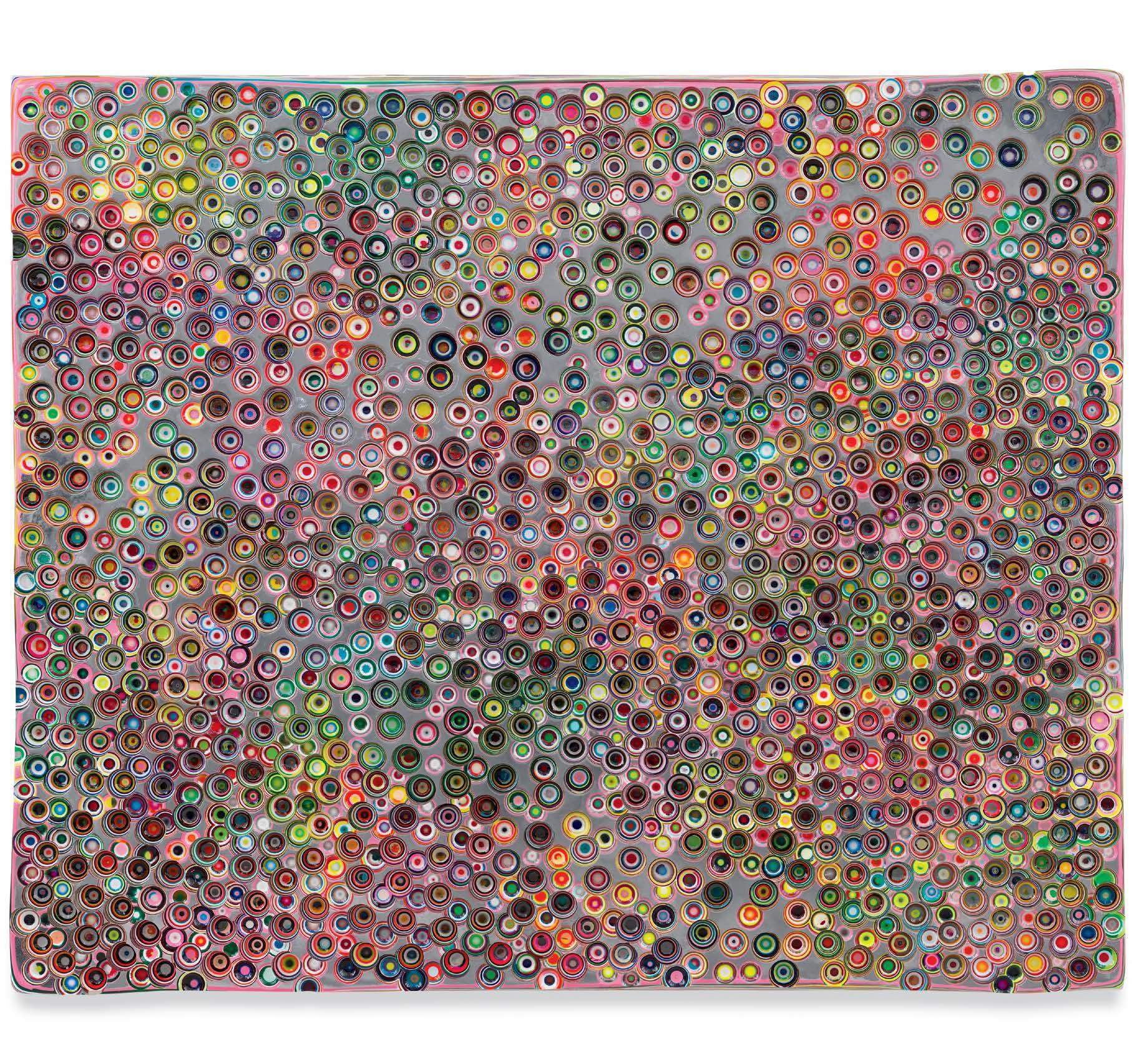

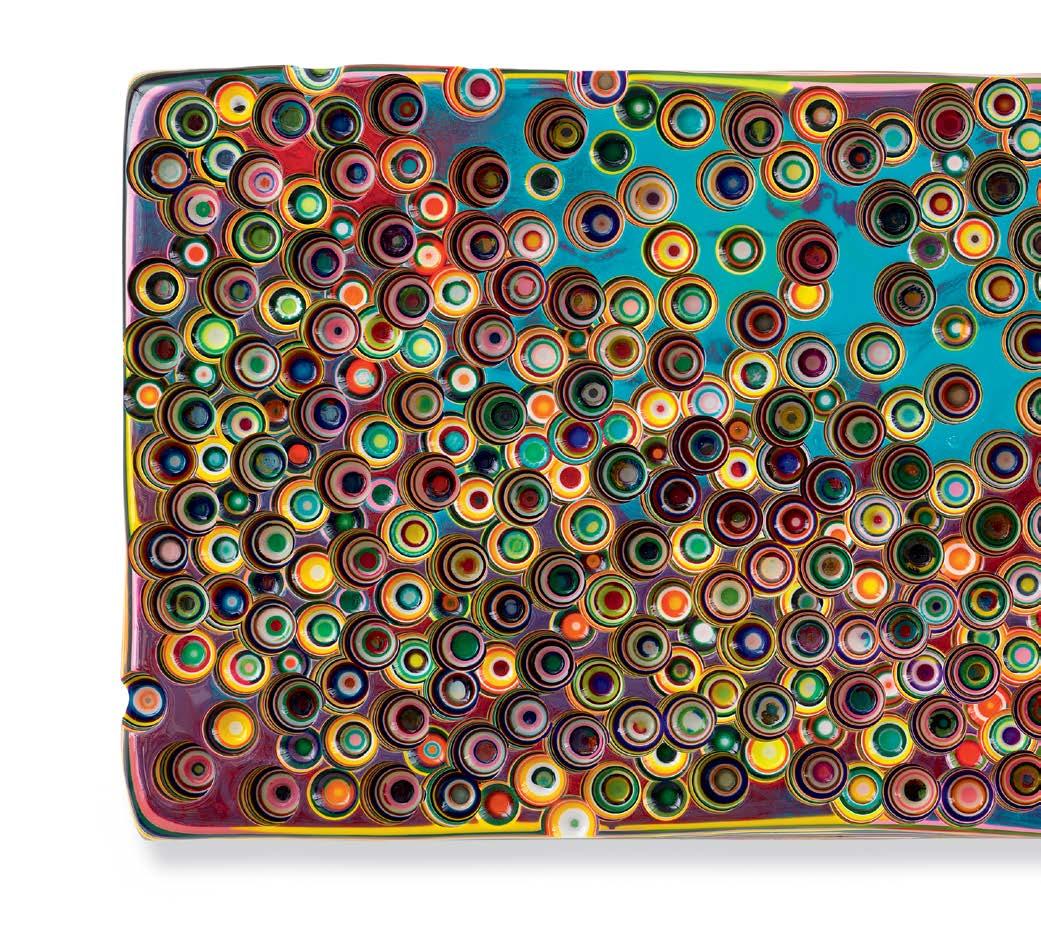

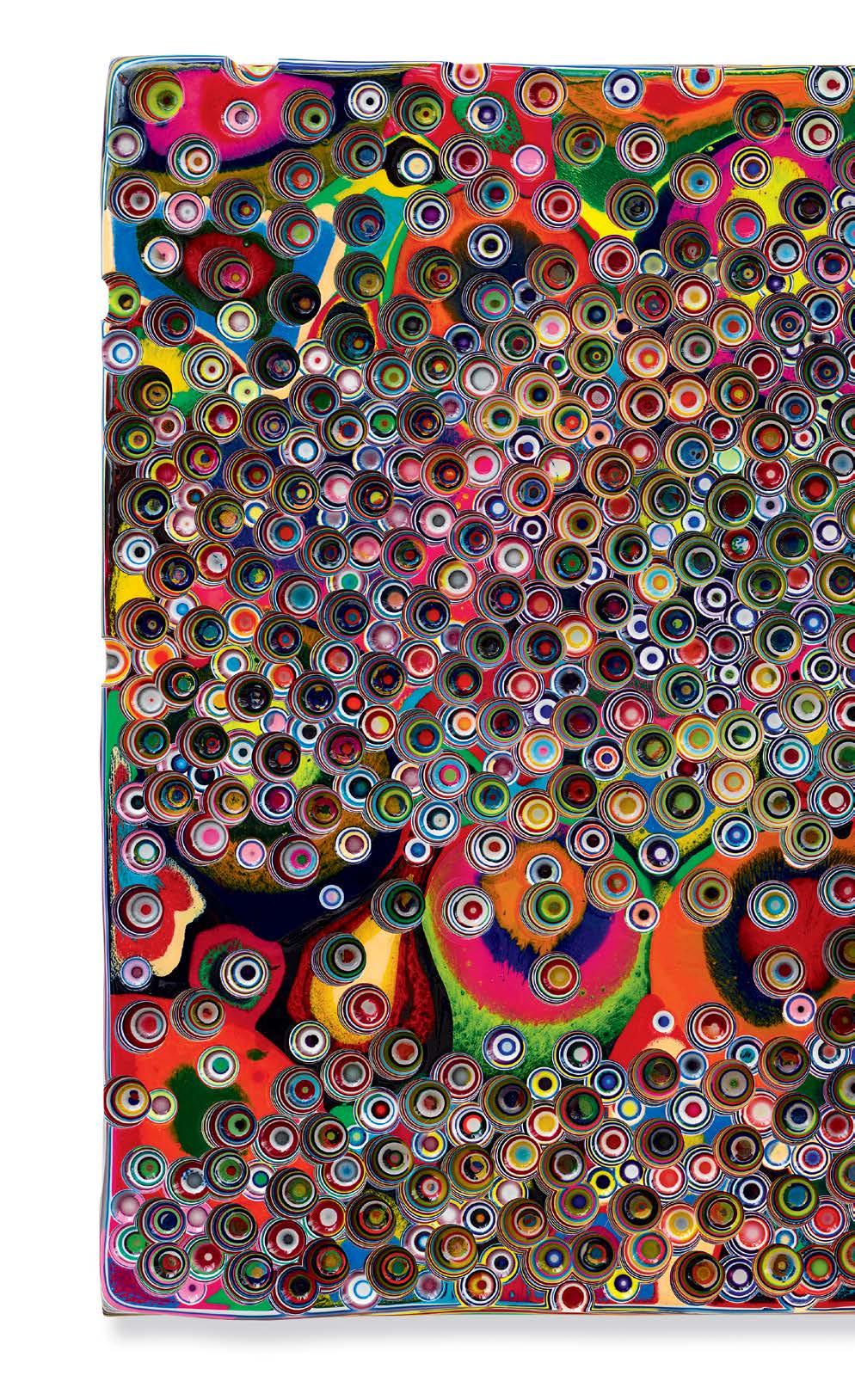

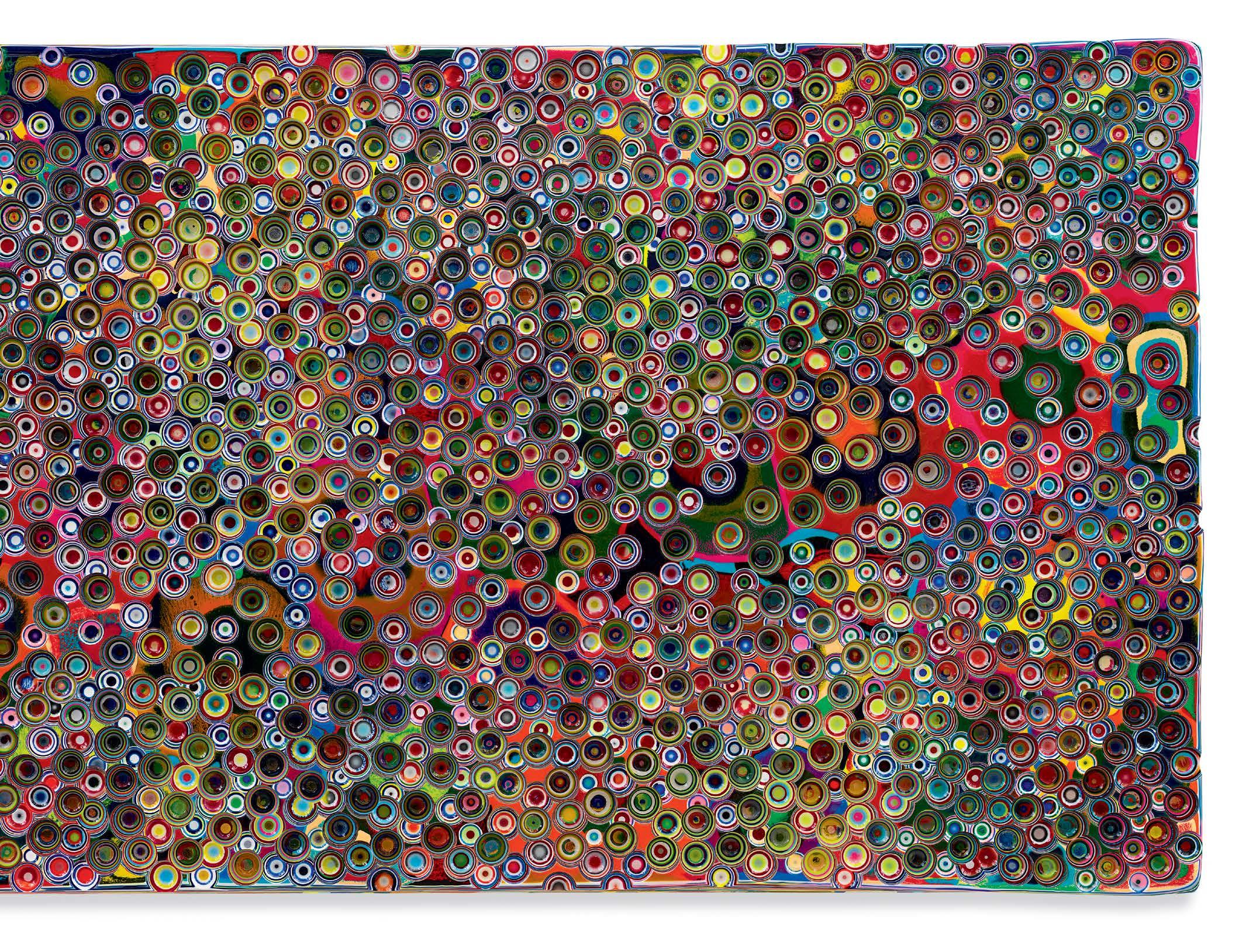

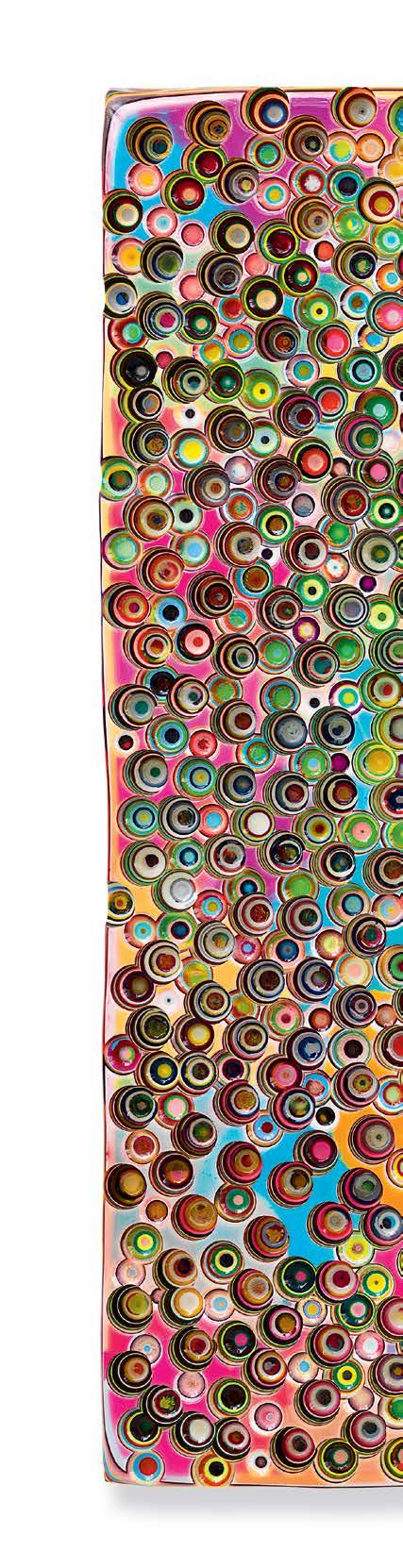

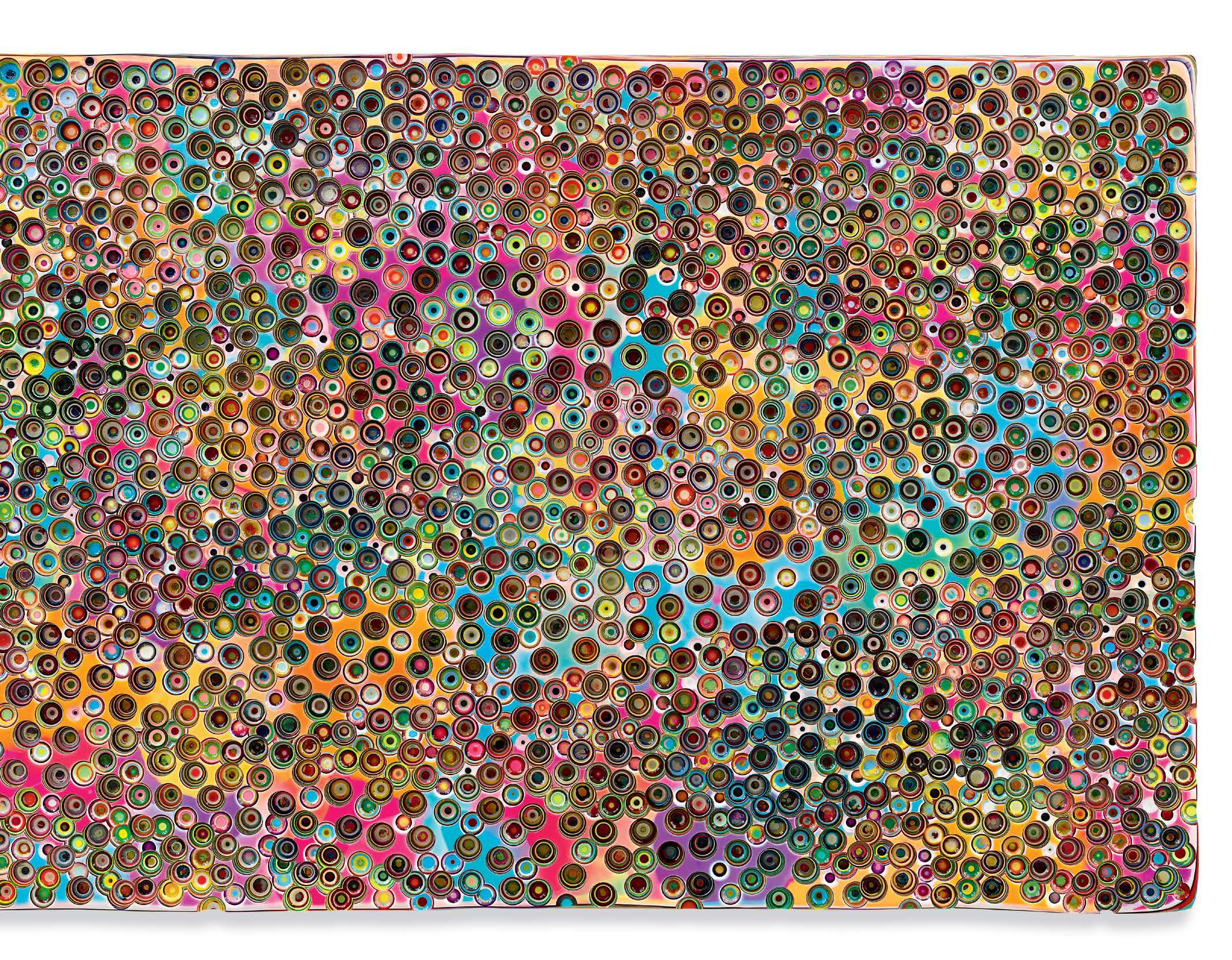

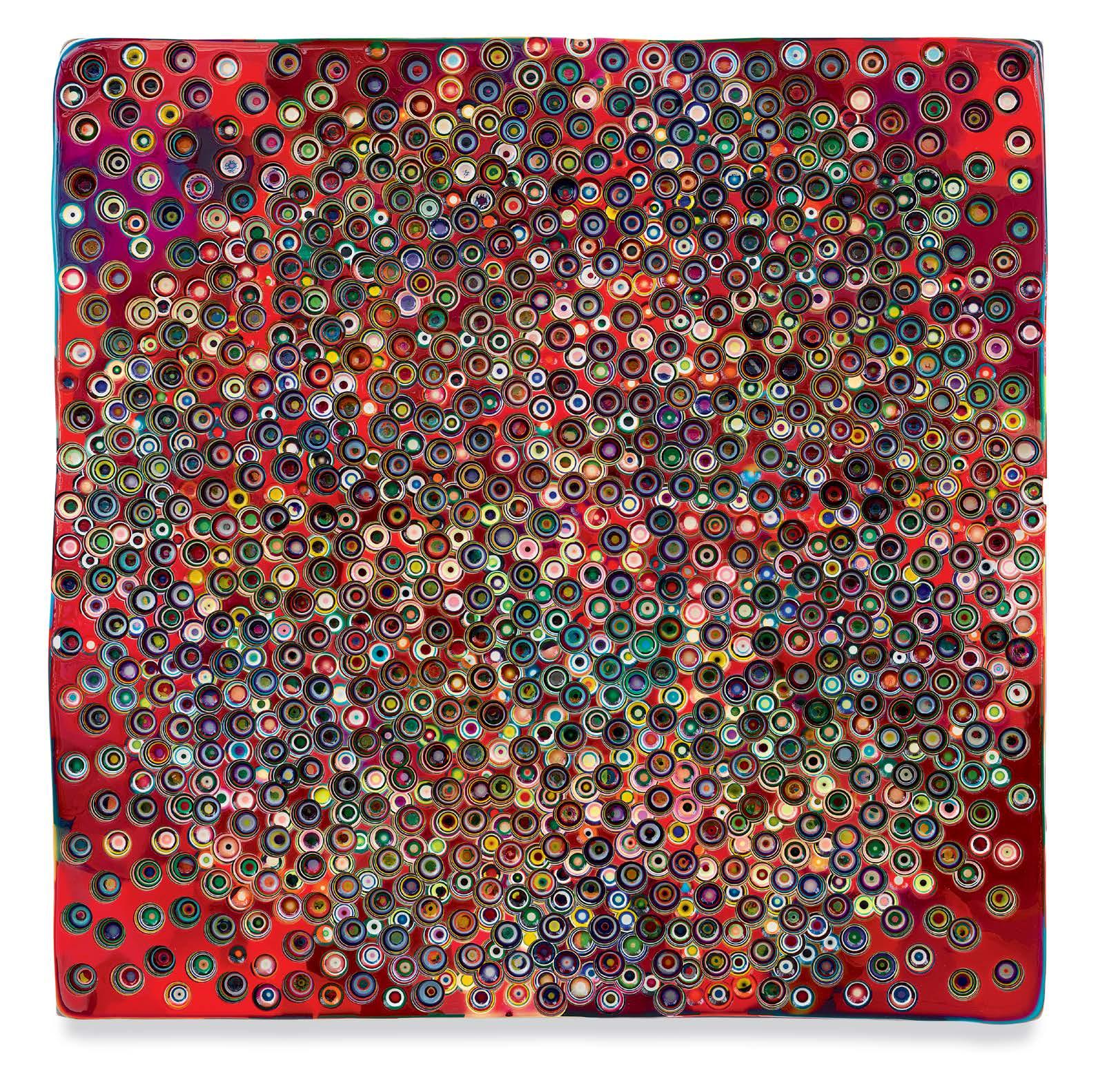

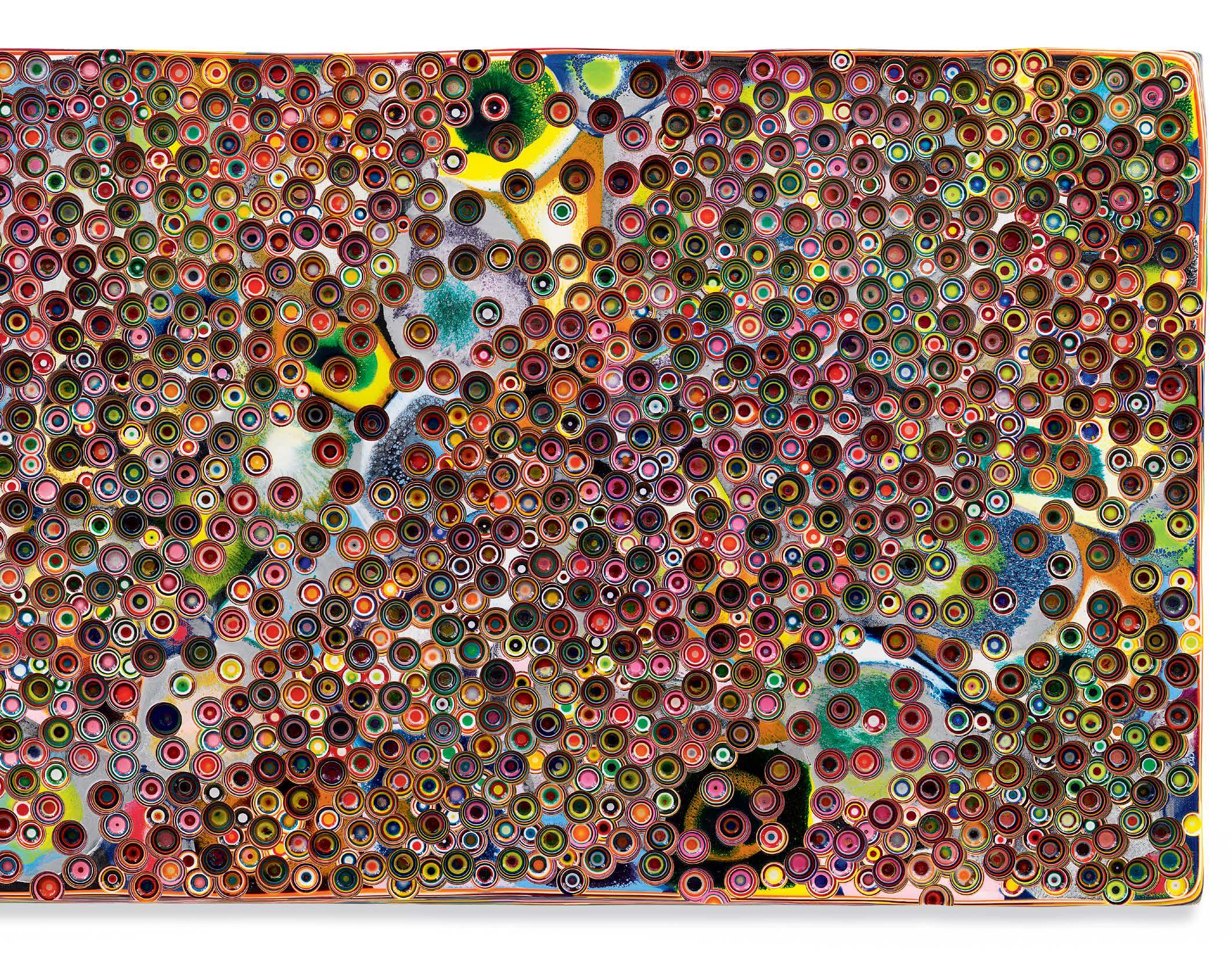

(2016), currently on view at 75 Rockefeller Plaza. Titles are visual clues to reading the paintings—in small pieces across. Take any 6-inch section of a drip painting, for example, and you will find a perfectly composed quote that reads as coherently as the painting does as a whole. The drill pieces are, upon closer inspection, composed of thousands of small, circular paintings that contain cloud-watching blobs that can be faces, fire trucks, lightning, lizards, or dancing bodies that move to the beat of the song after which the piece is titled.

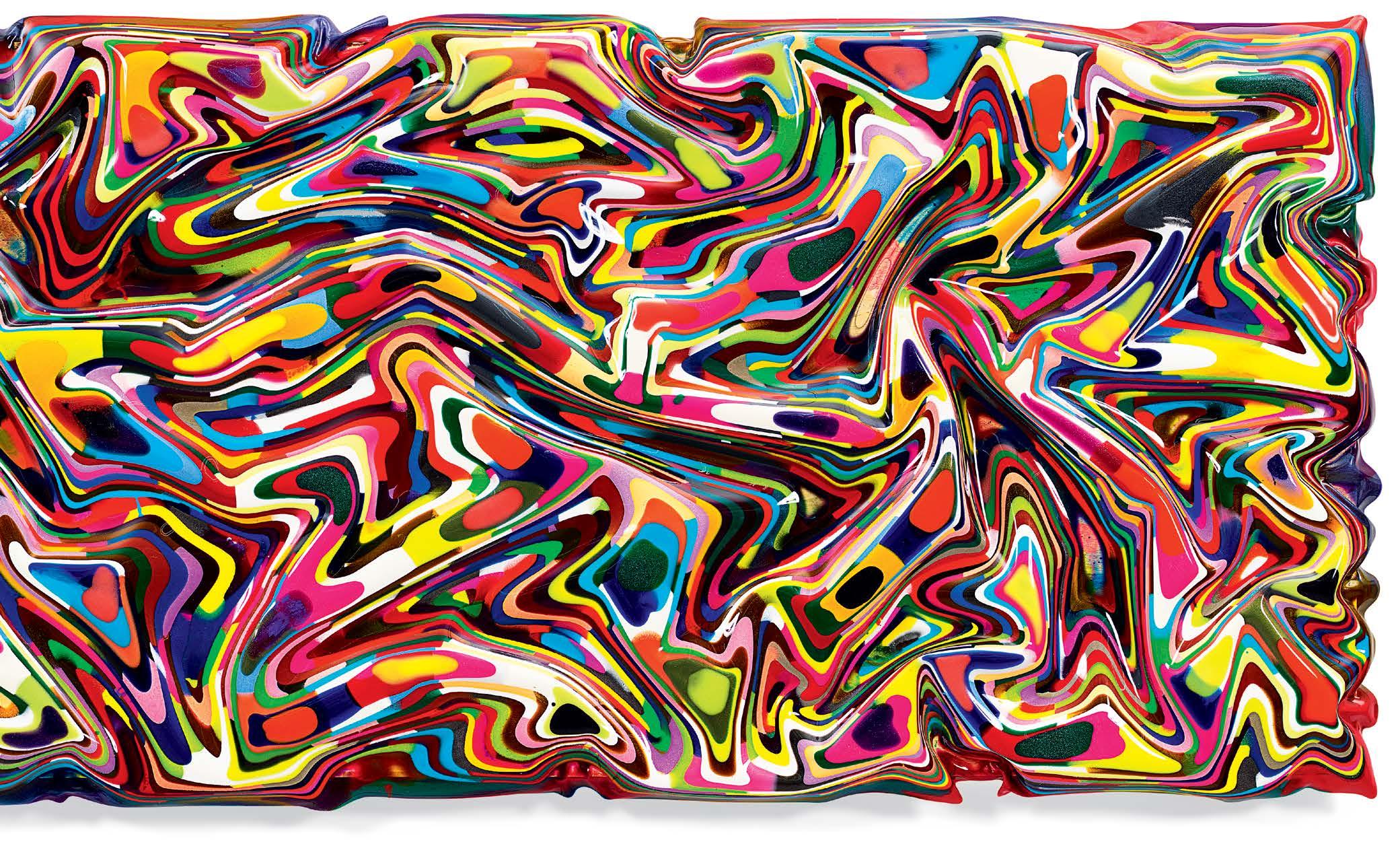

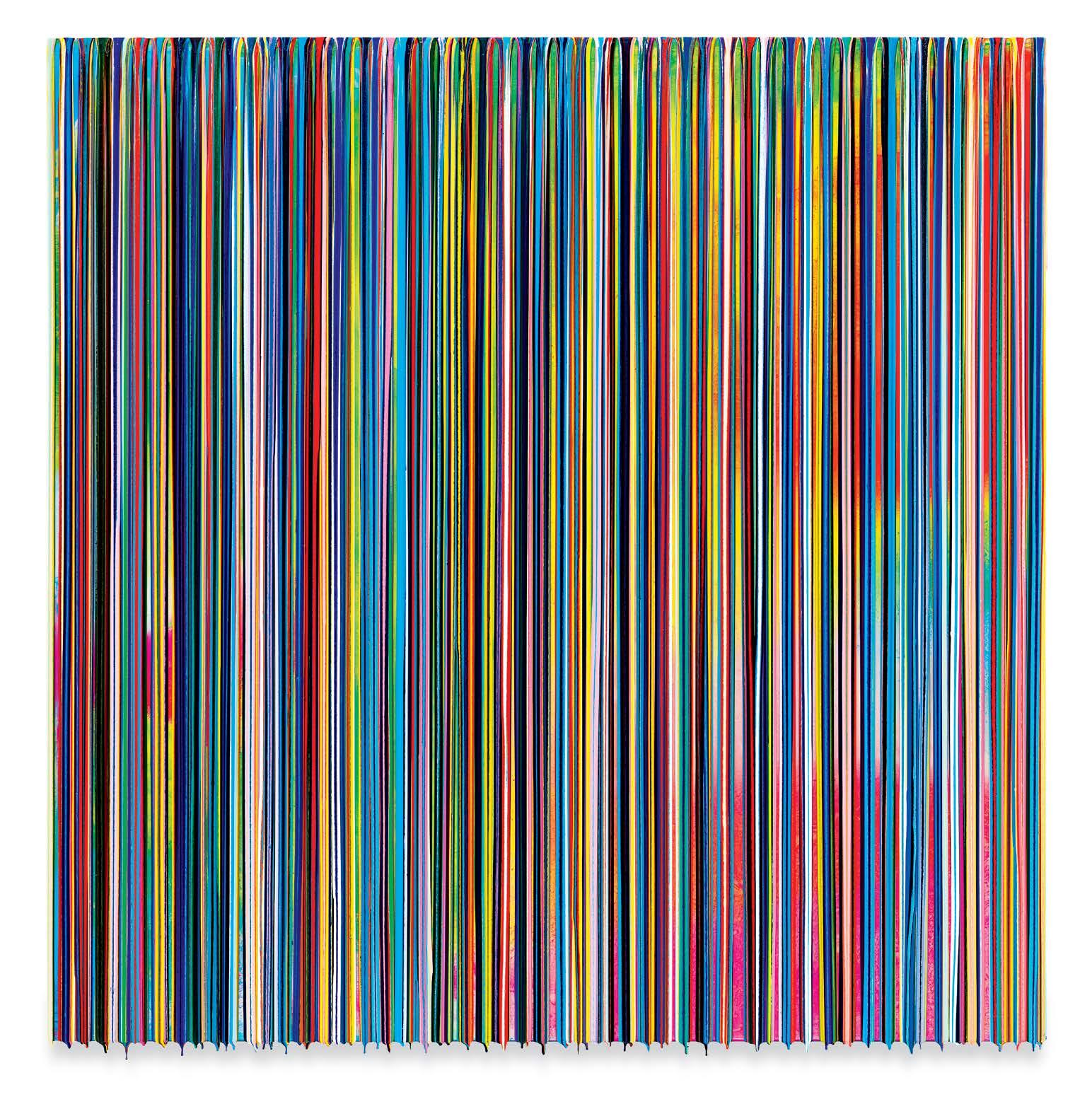

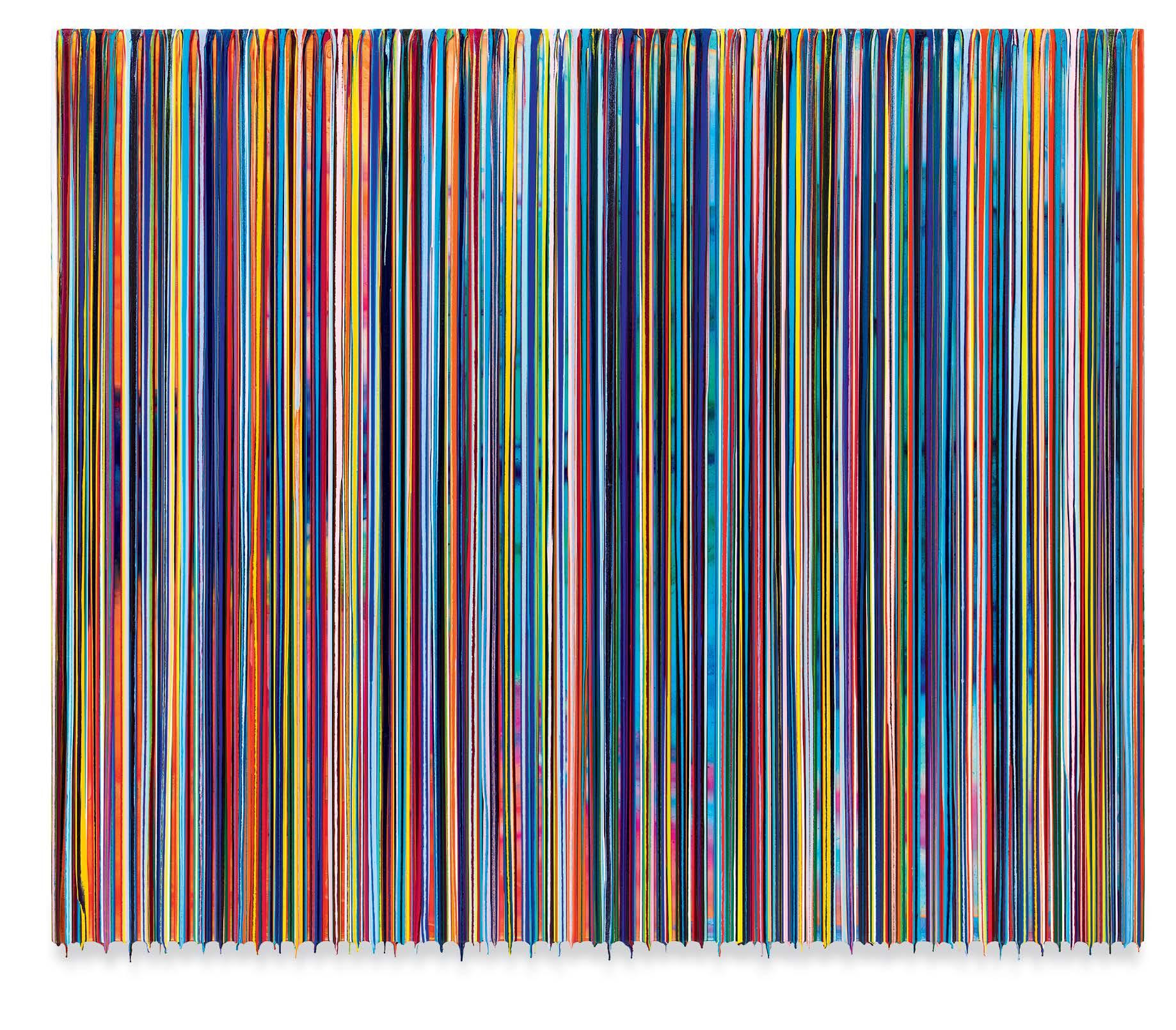

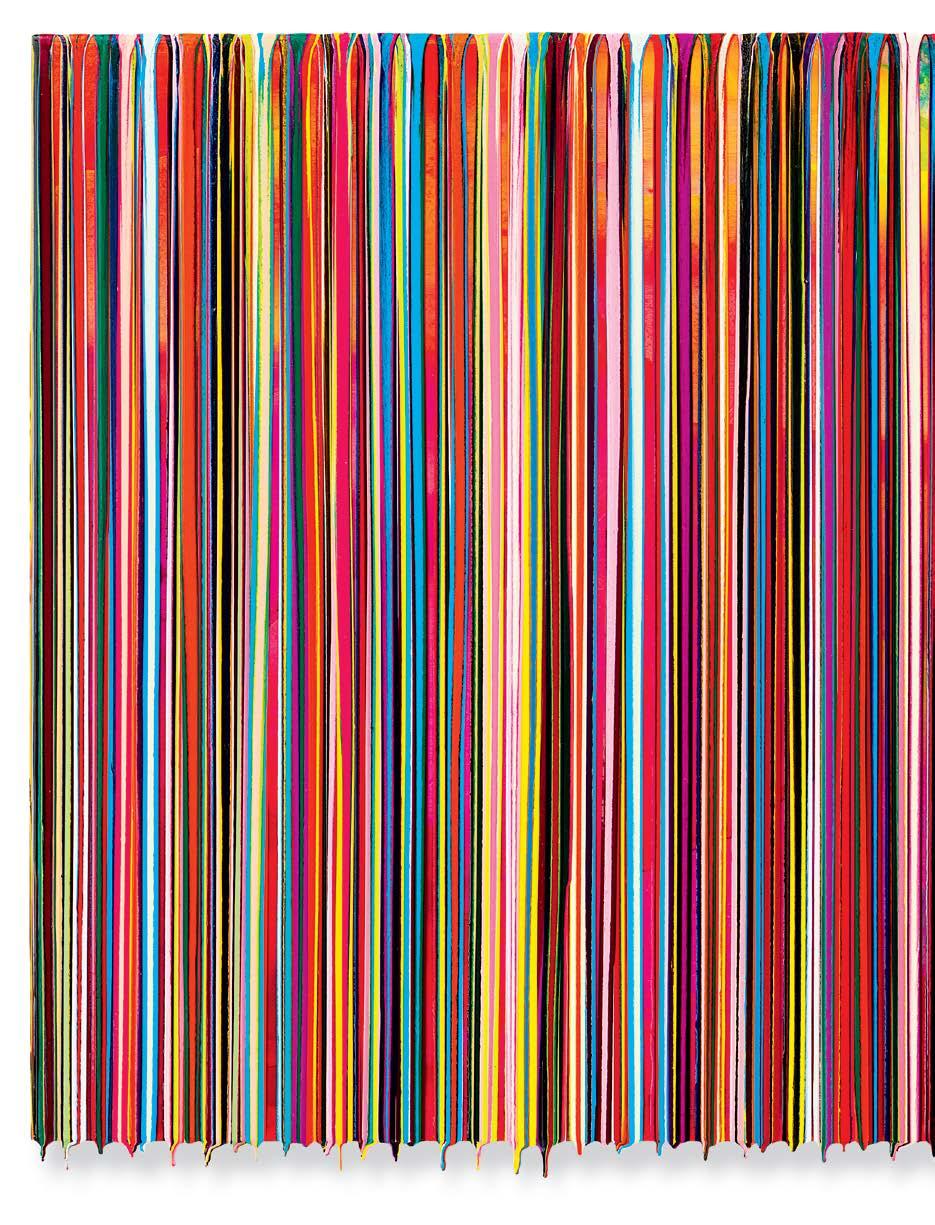

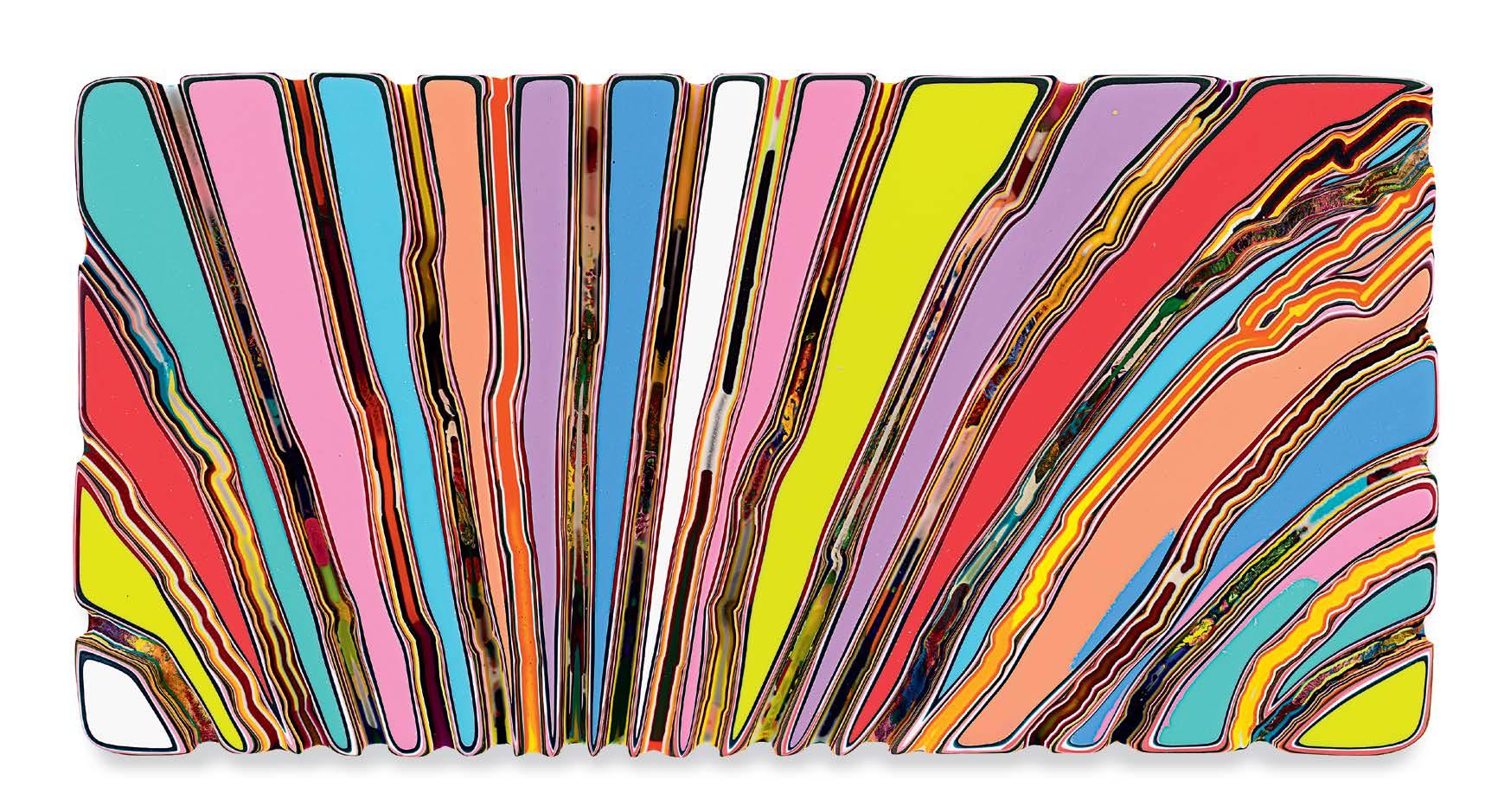

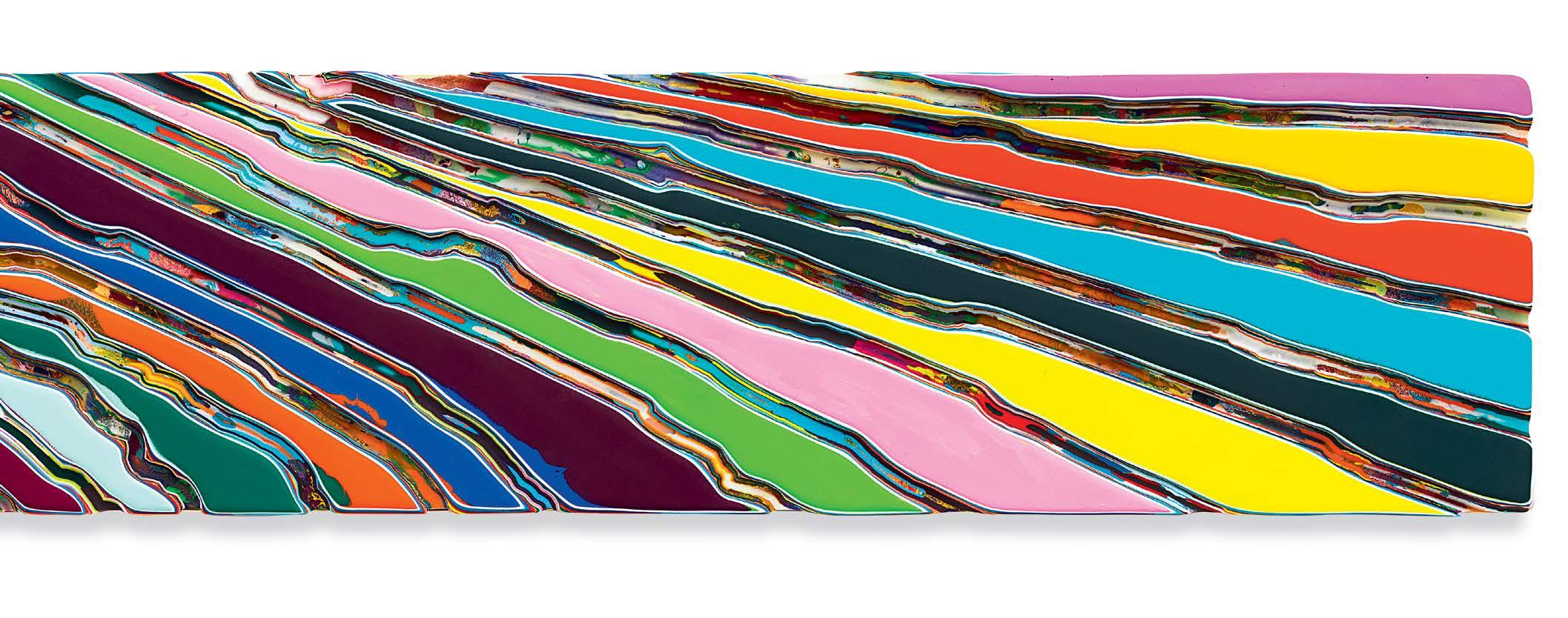

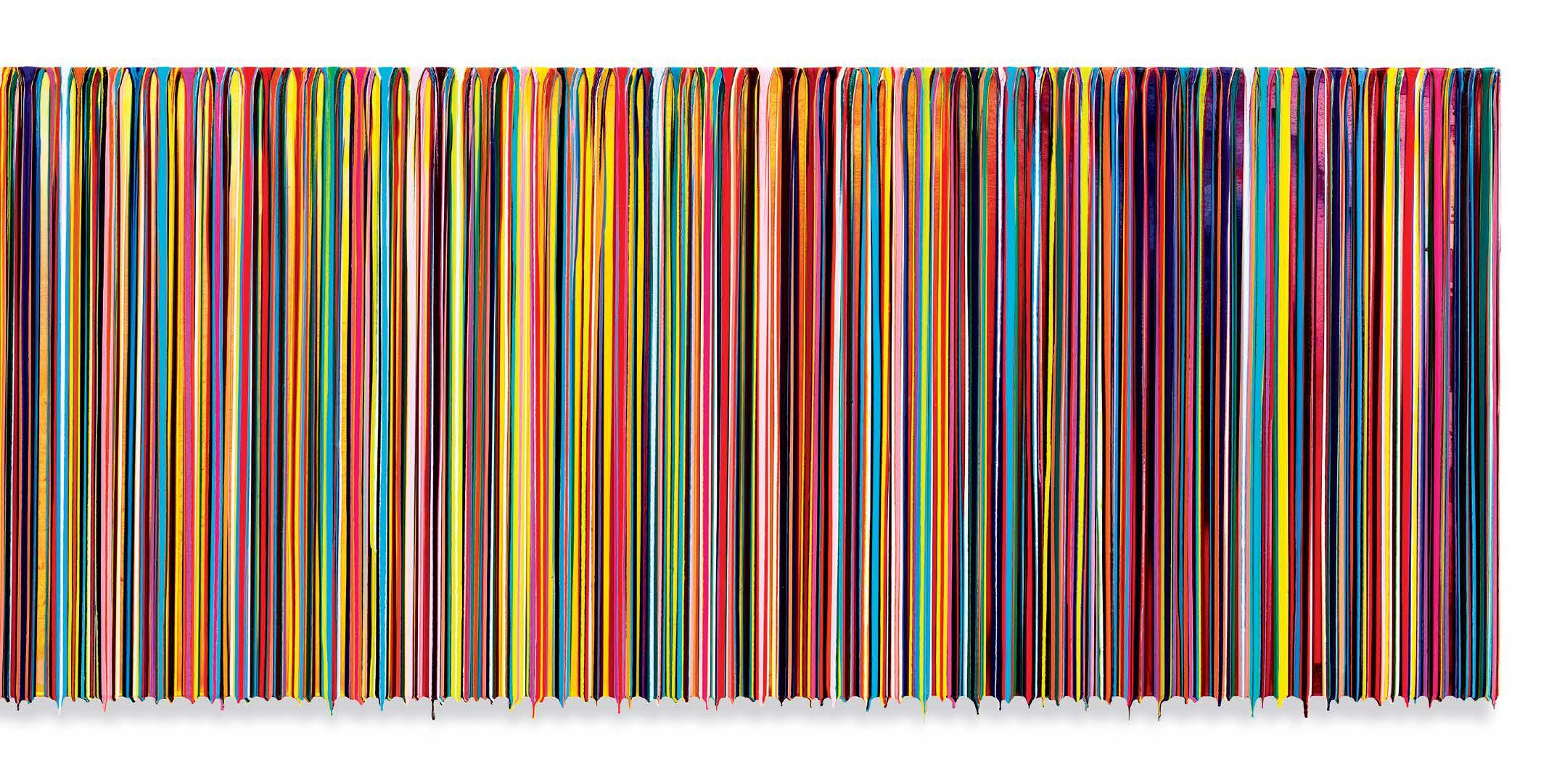

Music plays an almost integral part in the work. His titles are snippets from song lyrics, and his horizontal drip paintings evoking musical instruments themselves. WEDRINKCOFFEEWITHCOLA (2023) is an elongated rectangular form not unlike the keys of a piano or bar lines on a sheet of music, its overly caffeinated title hinting at the melodic exuberance each divergent drip represents. The “reverse” paintings begin with their apexes and are then layered in subsequent tiers using colored resin onto a shaped vinyl mold. When the artist has accumulated enough layers, he them mounts the composition to the frame, which reveals the piece to the artist for the first time. This kind of “blind” painting presents a trust between the artist, the material, and his colors. The peaks and valleys in ALITTLEASPHALTHEREANDTHERE (2022) become a jig of yellows, blues, greens, oranges, and other colors creating a visual dynamism that implies a moving narrative rather than a static painting.

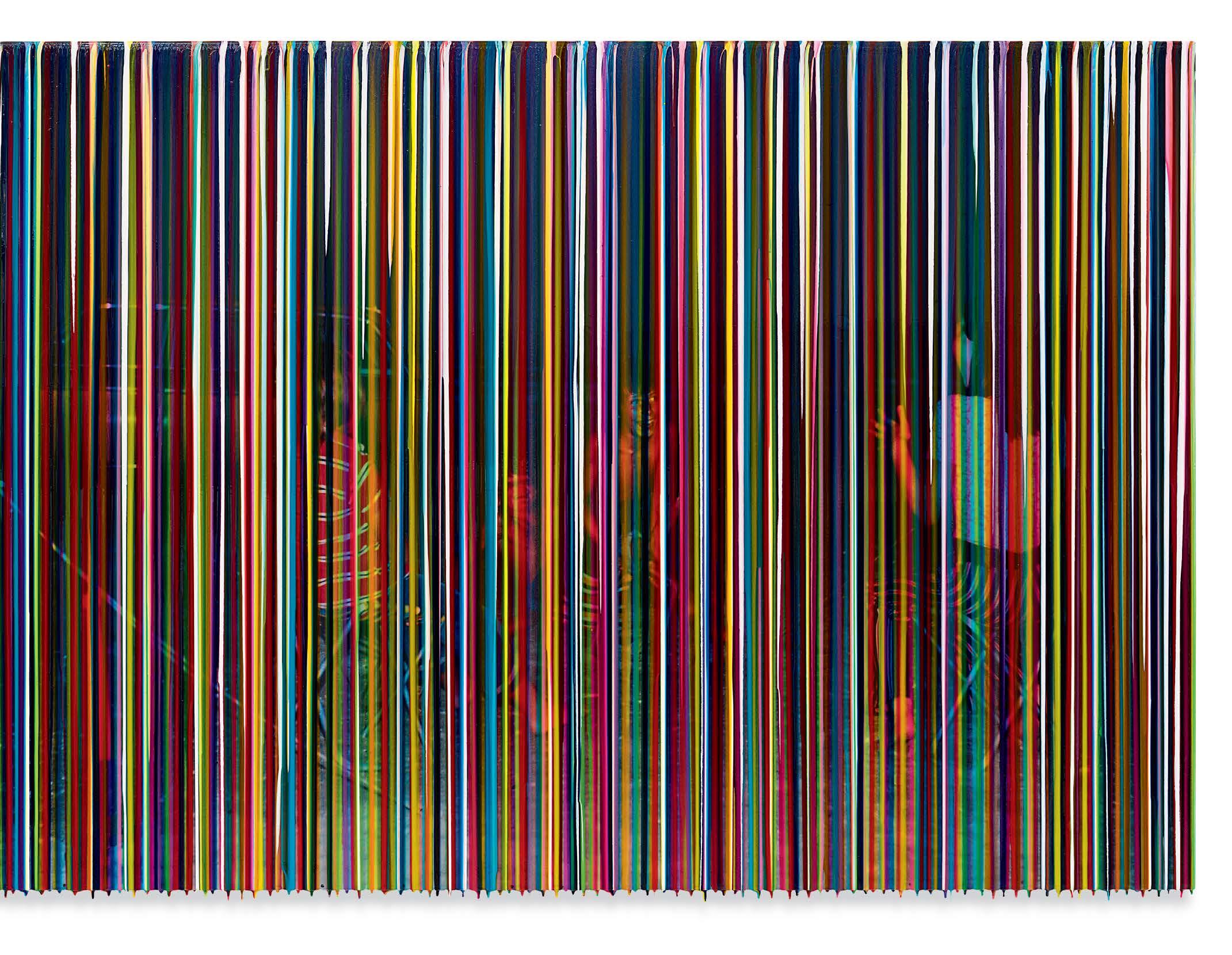

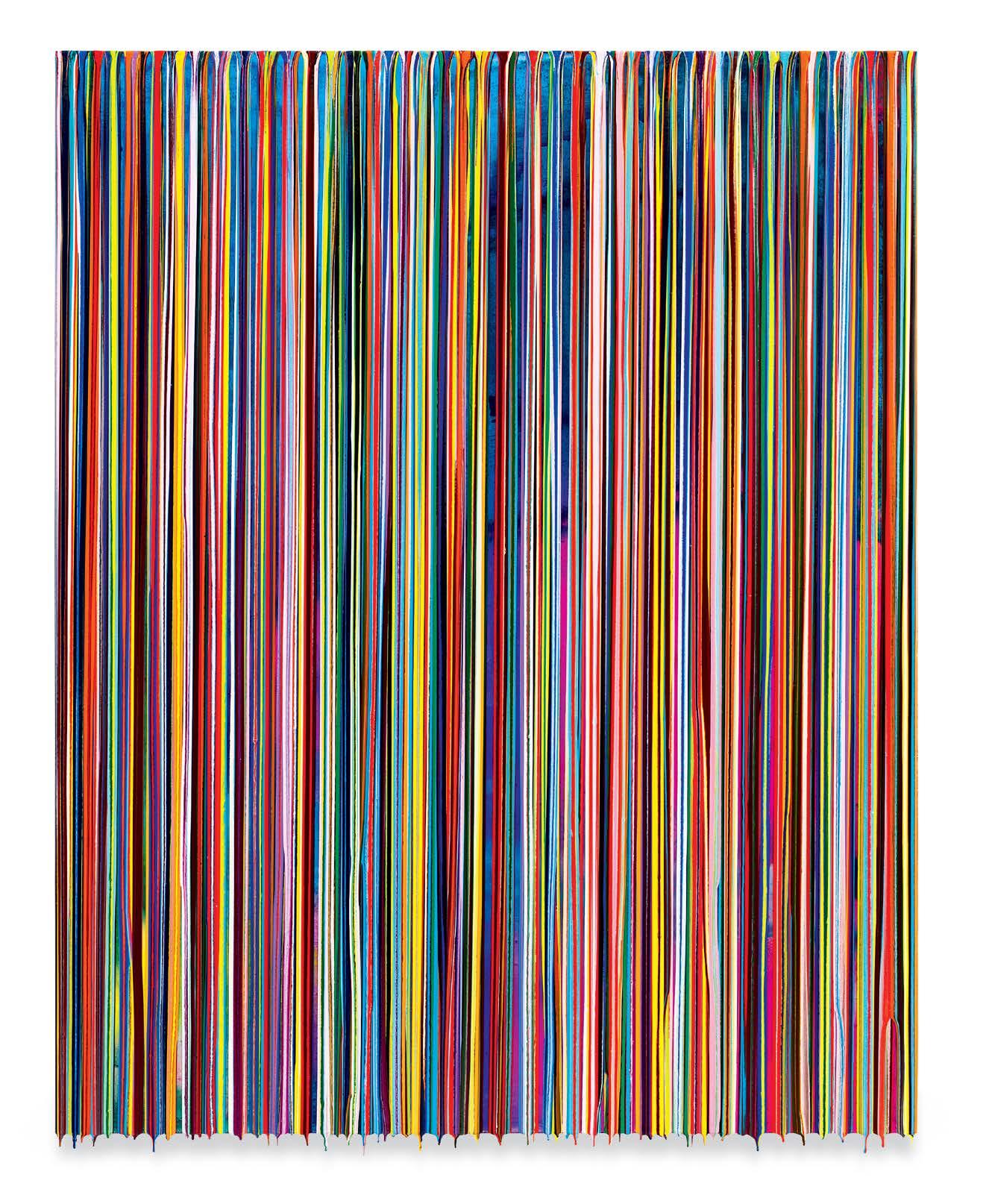

Linnenbrink’s paintings are the result of material and process. Barely an ounce of material is wasted during the production of his works; the “drip” paintings are poured from the tops of the panels and are allowed to flow freely toward the bottom, creating a stalactite of colored epoxy resin at its edge before landing onto an awaiting paneled composition or sculpture, the latter of which encapsulates discarded objects gathered by friends and family, rescuing them from the fate of our general refuse. His two-dimensional works are composed of layers of colored resin, which are spotted, poured, swirled, airbrushed, and excavated into concentric circles that overlap from their centers to the lacy edges created by the artist’s disregard of the natural boundary, or routed into comic book lines that punctuate matte-colored arcs.

COLDWORLDGOODMANBITEBACK (2023) is an orb that seemingly bounces through the parade of rectangles usually found in white-box spaces. It tempts the viewer with its slick, shiny surface and its seemingly deep oceans of objects, familiar and absurd, that peer out through the breaks in color. The bands of pigmented resin that run

throughout are like spaces between text that help us understand what we are seeing: keys, batteries, cutlery, a Seinfeld biography, plastic men, sunglasses. A collage of the everyday, a synecdoche of the self.

The exuberant greeting. The encapsulation of everything. The enveloping installations that were once described as “a great space to stand in and think about abstraction as an infinitely renewal energy source.”4 This is a positivity that ignores the sighs of cynicism and instead embraces its viewer with a bear hug. It is with this that Linnenbrink finds his voice; he is an artist who extends an invitation to everyone to join the party and to be in on the joke that while we may not want to admit to our shortcomings, they exist for everyone.

What makes beauty relevant to contemporary art is its ability to engage, to will others to connect, and to offer new perspectives and new ways of understanding. Linnenbrink recently stated: “All works have a process of growth to them; a lot of that is related to process in real life. So, they also give examples of happenings in real life, like plans gone wrong, process in and out of control etc., so they are open to find oneself in them.”5 Linnenbrink’s work is about our ability to consider and accept things as long as we are open.

“My work is more focused on creating a space to enter for everyone that wants to experience it. The struggle is not the center of my work. It is the power and energy colors carry when brought together in a way so they sing and work together. That can create a similar power as great music has, the moment that exists on its own, releasing and stimulating emotions, thoughtfulness and joy. I want the work to be open, readable, and accessible. I am not interested in explaining the world, but I am very interested in understanding the way we experience it. If that is subversive is not for me to judge. But the better we understand things, the better we are able to act.”6

Notes

1. Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 3.

2. Ibid. 114.

3. Artist interview, March 2023.

4. Roberta Smith, “Varieties of Abstraction,” The New York Times, August 6, 2010, C21

5 Artist interview, March 2023.

6. Ibid.

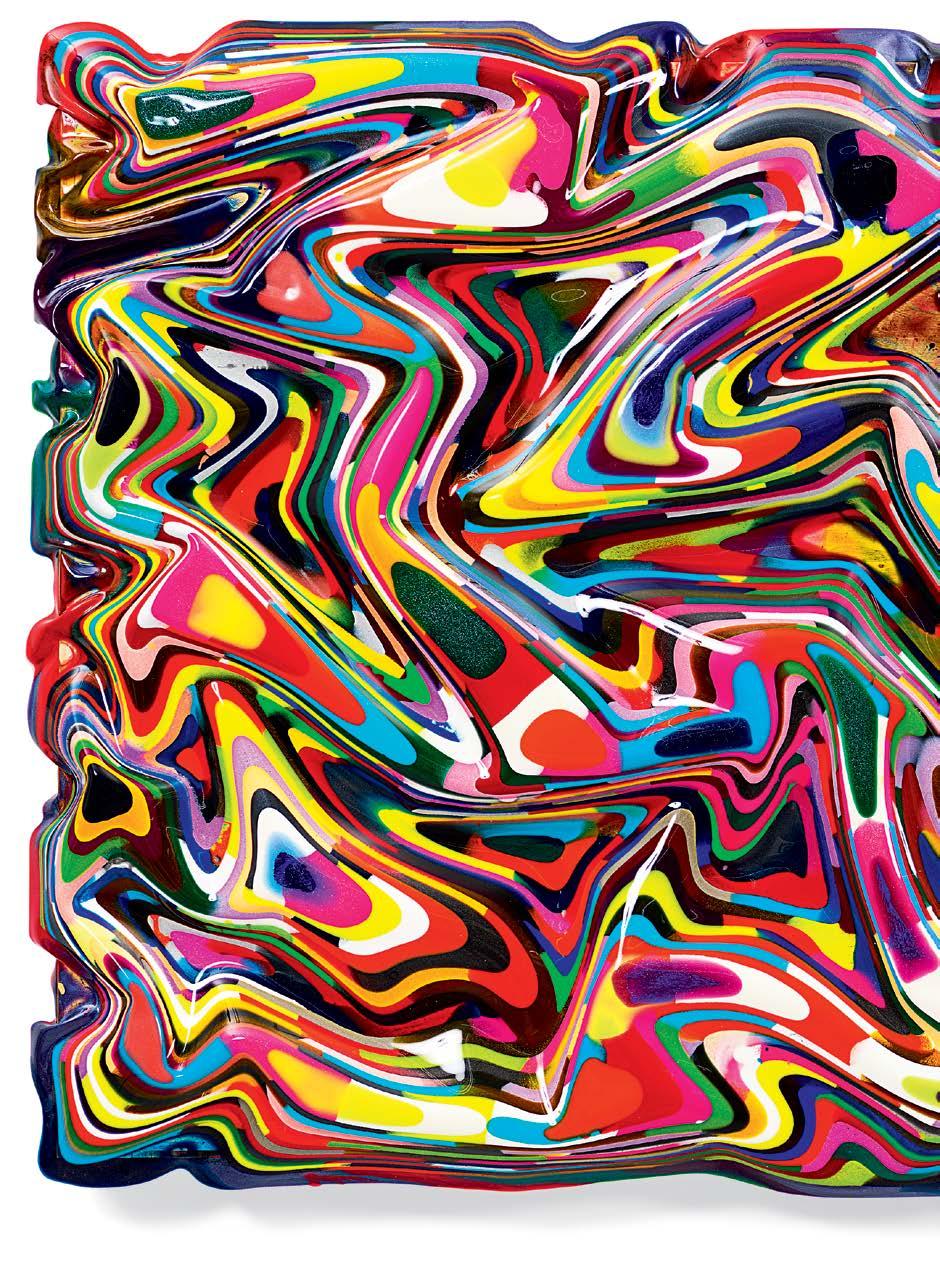

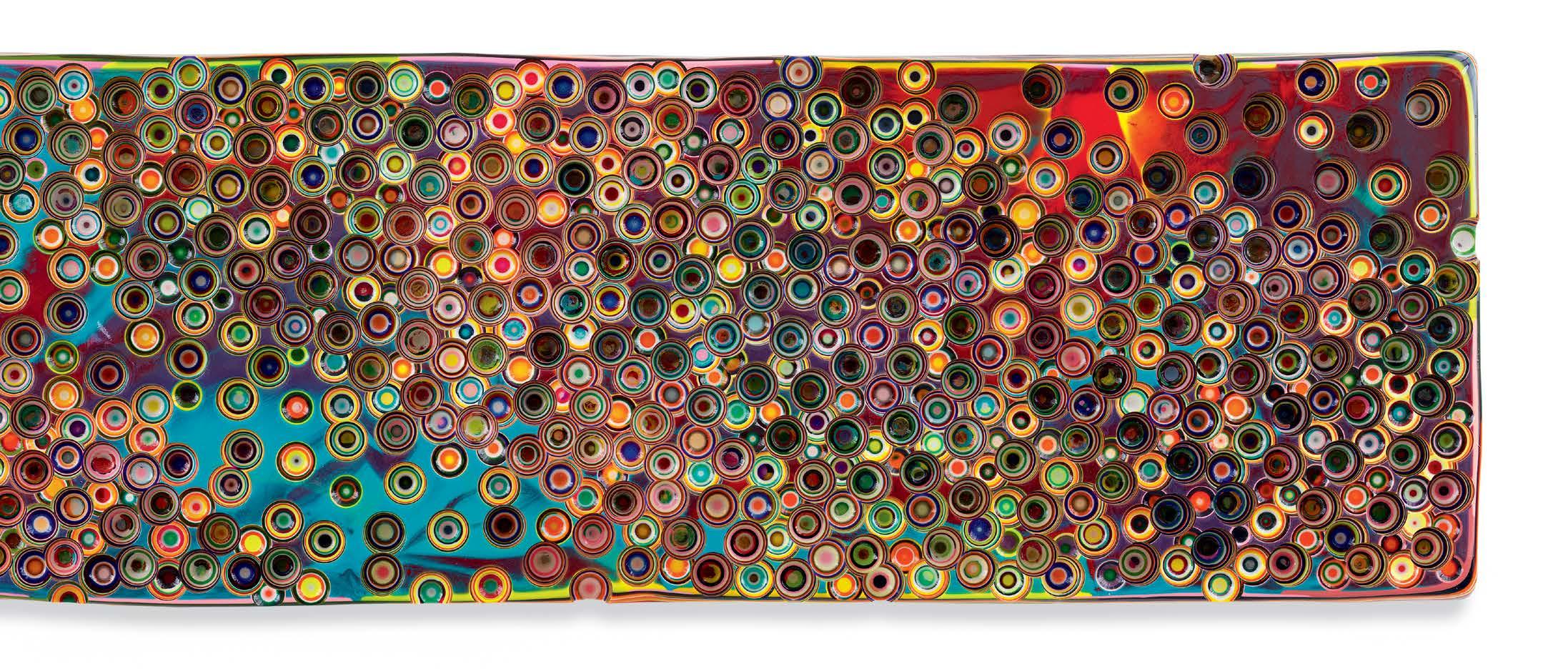

ALITTLEASPHALTHEREANDTHERE, 2022

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

39 x 99 inches

99.1 x 251.5 cm

BREAKINGTHROUGHTHESOIL, 2022

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

24 x 96 inches

61 x 243.8 cm

60 x 60 inches

152.4 x 152.4 cm

IHAVEBEENWAITINGTOHEARYOURVOICE, 2022

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

48 x 96 inches

121.9 x 243.8 cm

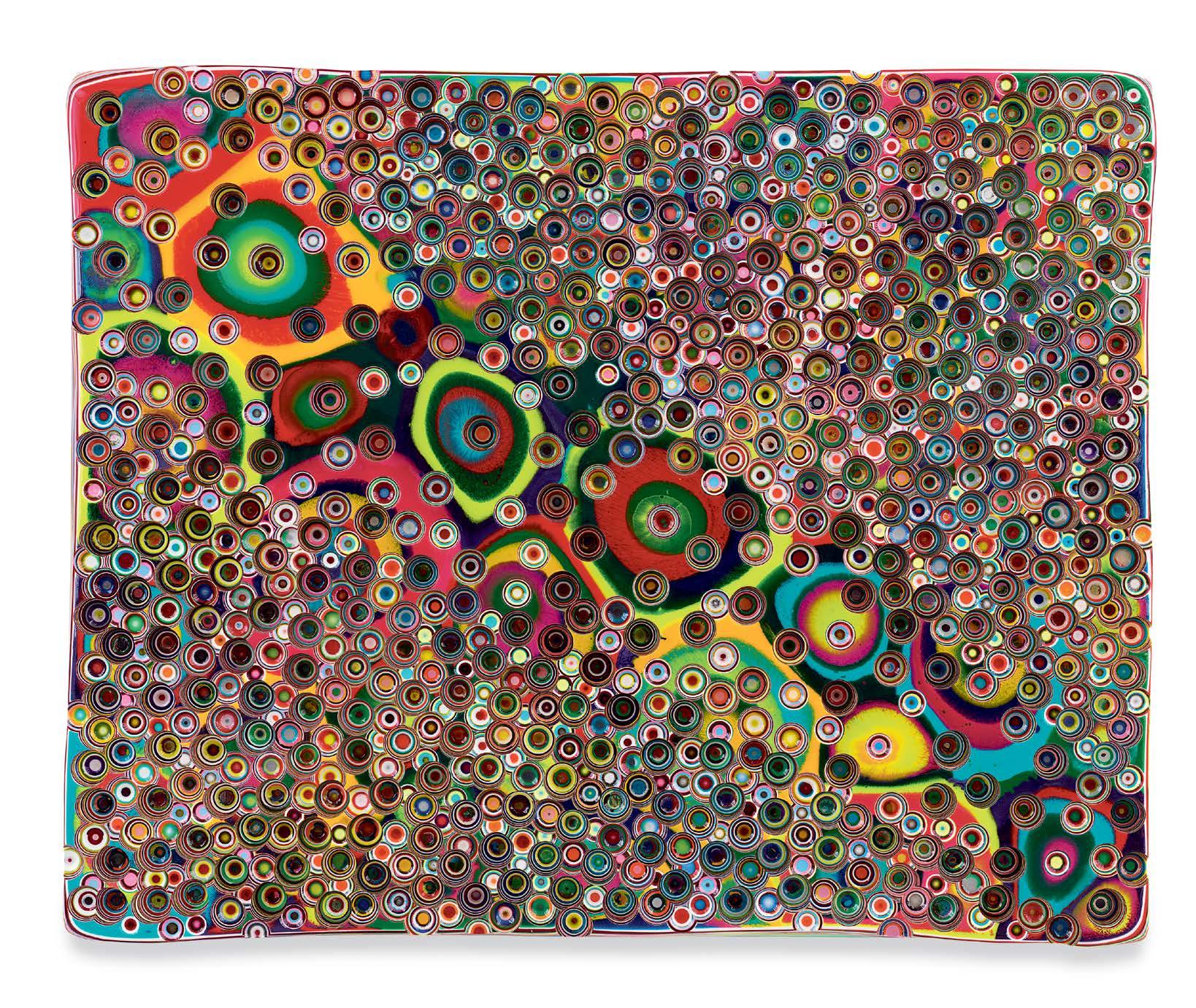

KNOWLEDGEBETWEENBLUEANDPURPLE, 2022

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

60 x 72 inches

152.4 x 182.9 cm

MYMINDIFINDINTIMES,

NEVERCREATEDNEVERDESTROYED, 2022

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

36 x 96 inches

91.4 x 243.8 cm

OUTOFSTYLETRAGEDY, 2022

48 x 60 inches

121.9 x 152.4 cm

60 x 90 inches

COLDWORLDGOODMANBITEBACK, 2023

Epoxy resin, pigments, objects

36 inches, diameter

91.4 cm, diameter

EVERYTHINGBETWEENTHESUNANDTHEDIRT, 2023

20 x 100 inches

50.8 x 254 cm

60 x 48 inches

152.4 x 121.9 cm

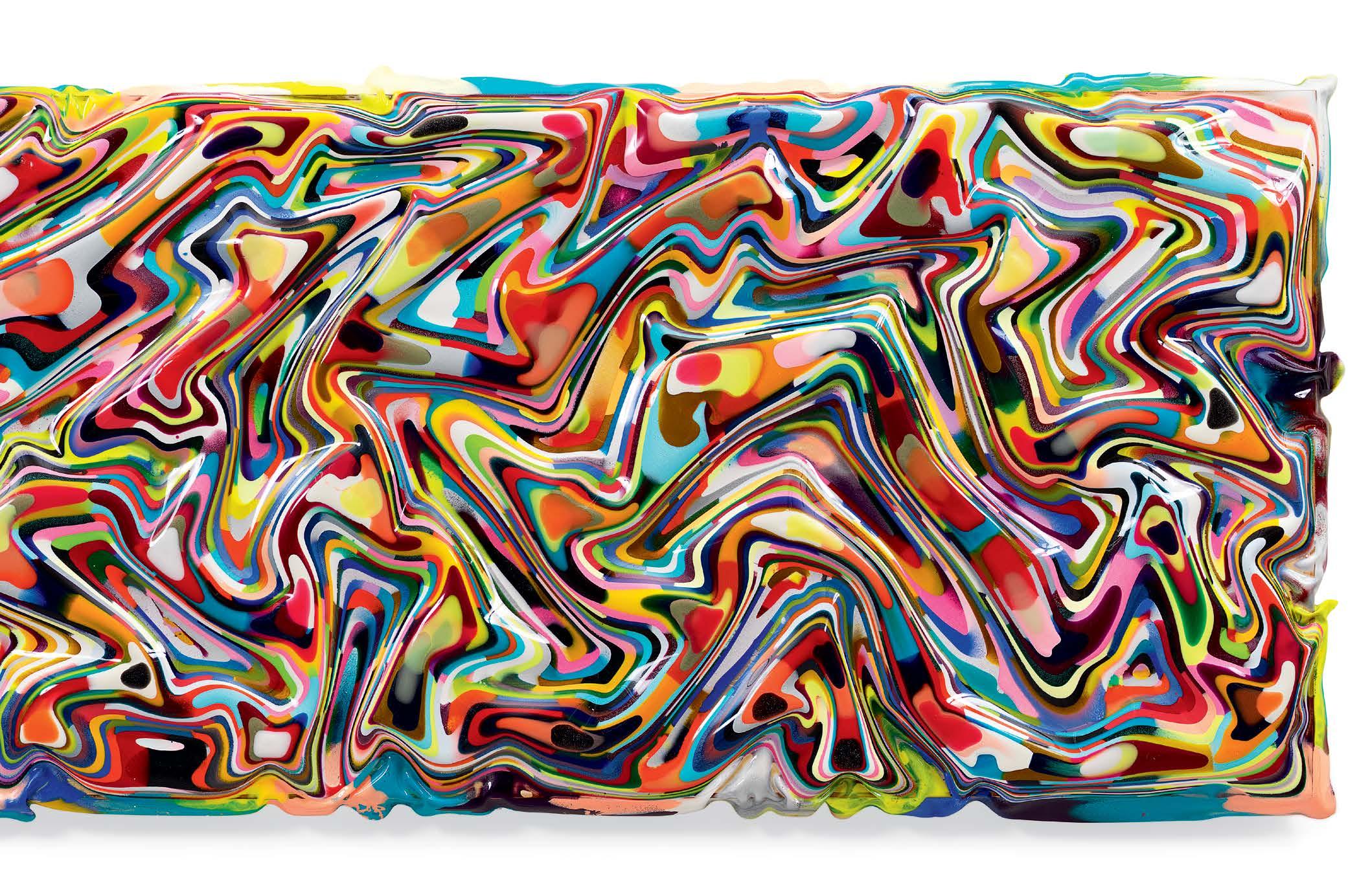

LONGINGFORTOMORROWSMOMENTOFTRUTH, 2023

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

39 x 99 inches

99.1 x 251.5 cm

OHIEND(ABOUTCOMINGANDLEAVING), 2023

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

24 x 96 inches

61 x 243.8 cm

RESONANZPERZEPTIONAFFEKT, 2023

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

36 x 96 inches

91.4 x 243.8 cm

THEBLISSTHEPLAYERTHEMIRROR, 2023

Epoxy resin and pigments on wood

48 x 96 inches

121.9 x 243.8 cm

28 x 96 inches

71.1 x 243.8 cm

WILDGEESEGOLDENBEES, 2023

48 x 48 inches

121.9 x 121.9 cm

EVERYTHINGBETWEENTHESUNANDTHEDIRT

8 June – 22 July 2023

Miles McEnery Gallery

511 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051

www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2023 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2023 Cindy Rucker

Director of Exhibitions

Anastasija Jevtovic, New York, NY

Publications and Archival Assistant

Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Christopher Burke Studio, New York, NY Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Color separations by Echelon, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 978-0-9850184-9-8

Cover: ALITTLEASPHALTHEREANDTHERE, (detail), 2022