NICK AGUAYO

Nick Aguayo’s studio seems to be a world unto itself. It is located in a decommissioned U.S. post office building in the El Sereno neighborhood of Los Angeles, and the space is filled in all ways. Cluttered, chaotic, and overstuffed: it is a compact, selfcontained universe of creativity, erupting with materials that include canvases, paint, paper, and the like—with the artist at its center point. Paintings, both finished and in progress, are chaotically stacked. Papers—new, used, and to be reused—are densely piled.

The studio is bustling with transformational energy. Stretched canvases lean against the walls, lean against each other, and stack across the floor, such that the artist takes his work into an adjacent hallway to get a good look at it. With a vast mixture of materials both waiting to be deployed and having been discarded, there is an overlap between what is in progress and what is complete. The pileup of materials parallels the artist’s buildup of ideas, and Aguayo uses the space as a test bed where he can “put one thing next to another to see if it creates a spark.”1

Aguayo works on everything all at once. He moves fluidly and quickly between pieces in a continuous, rhythmic flow. A gesture on one canvas affects decisions on the next, and so on. Ideas spread from one work to another, as the artist moves in, around, and through the studio. The collisions in the studio parallel the layers upon layers of ideas that occur within a single work. One work imprints onto an adjacent piece to become part of its history. In the end, each work is the result of an animated interplay, a simultaneous back-and-forth on a single canvas and across multiple works.

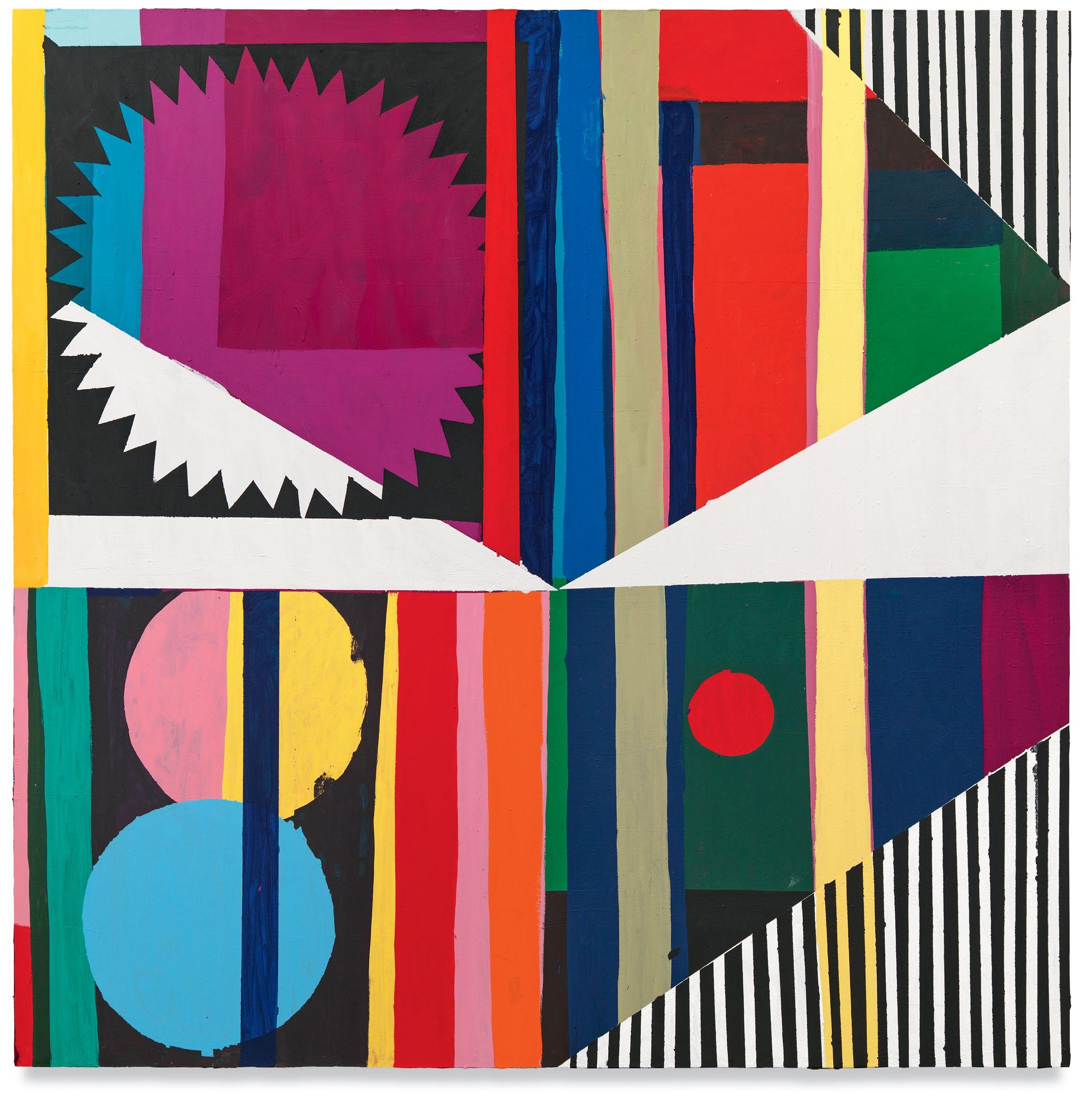

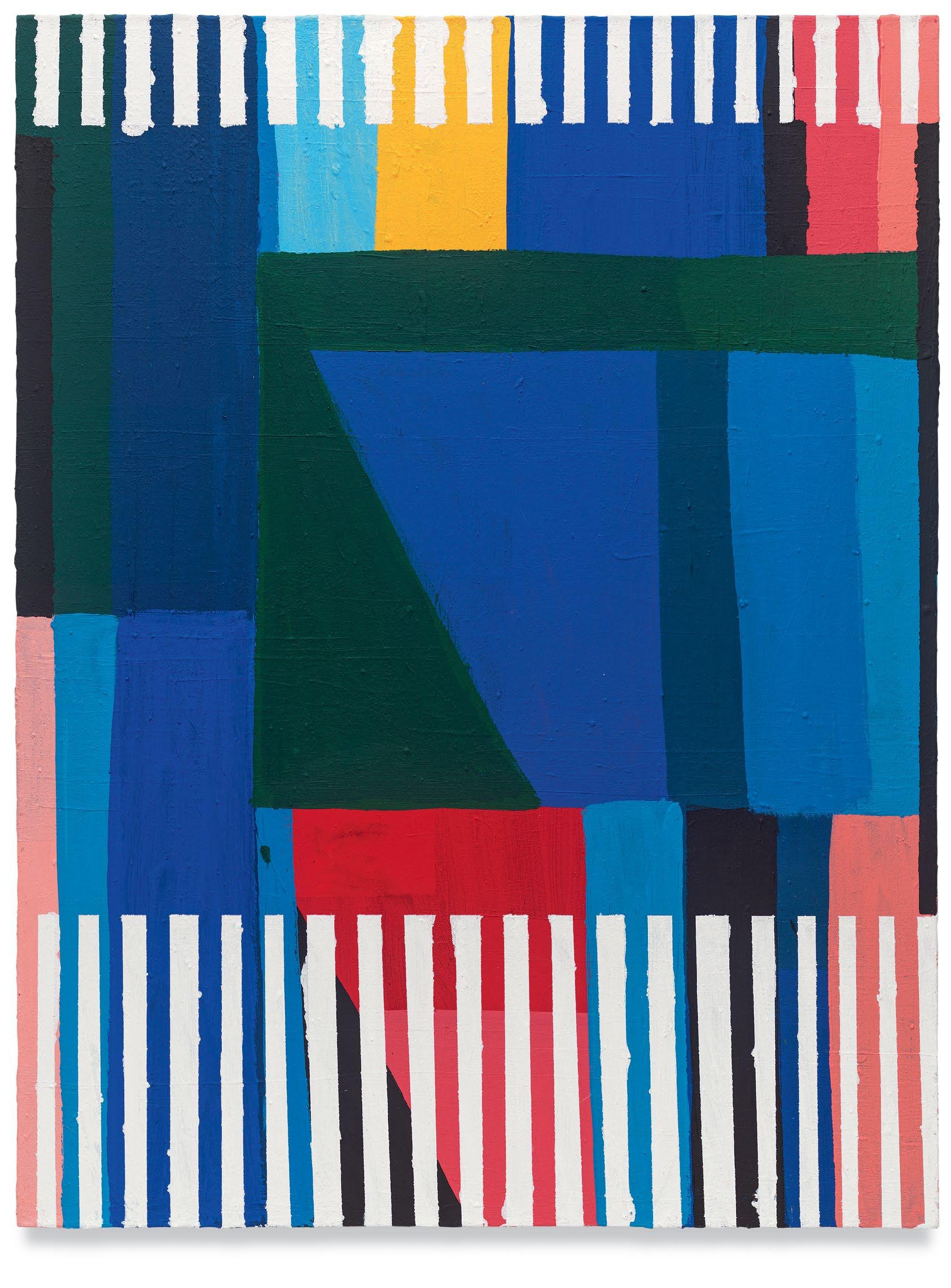

According to the artist, his mark-making is planned as well as inadvertent. Loose structures—often based on the grid and other regular or repeating forms—tend to be starting points. But accidents lead to other marks being made in response to those

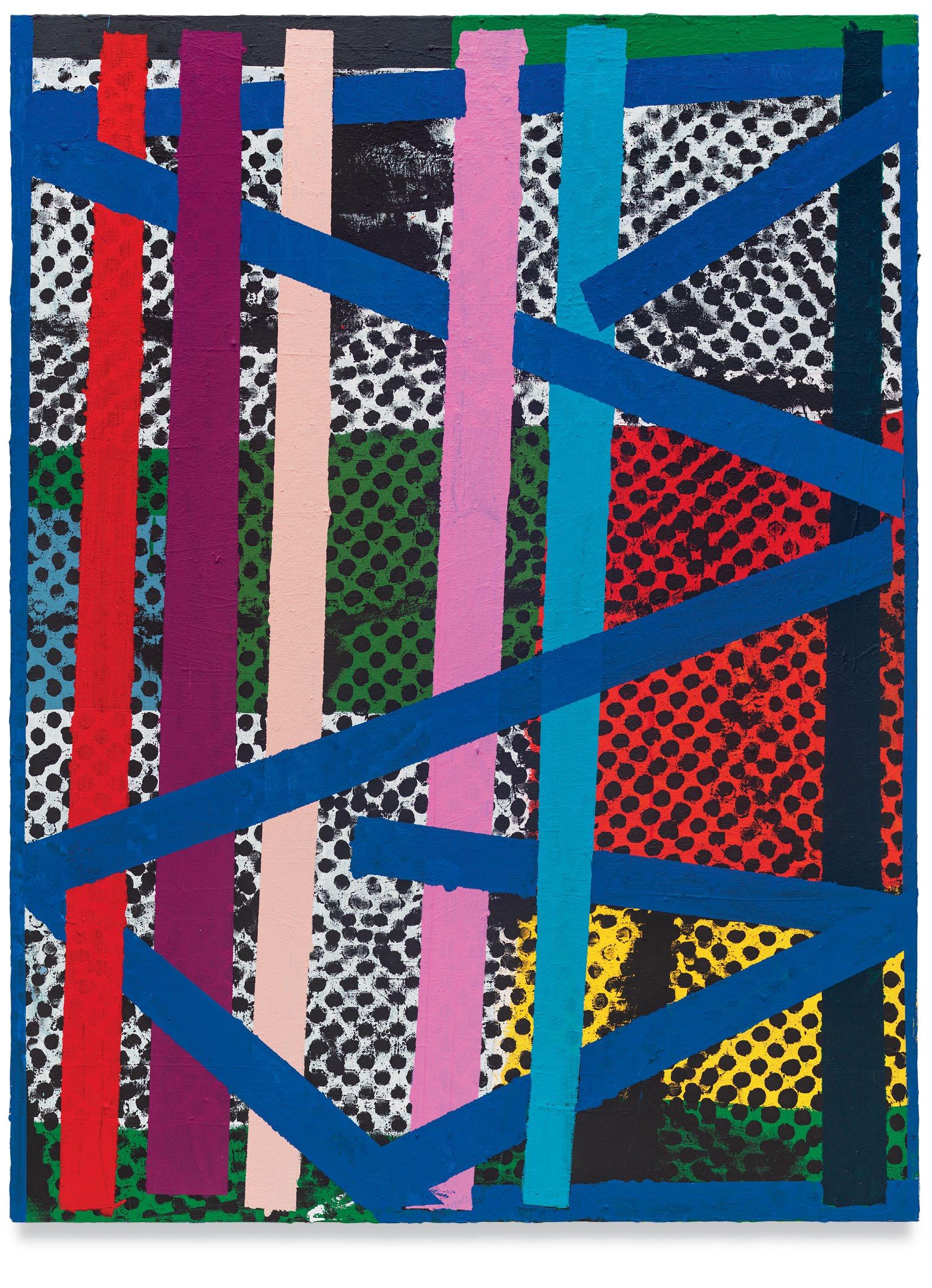

that have come before. Nevertheless, out of this seemingly chaotic creative situation, patterns emerge: Shapes, forms, markings, colors, and approaches become increasingly legible. Circles are small, medium, and large; they are lined up in rows, and they punctuate fields. Horizontal, vertical, and diagonal strips and stripes are woven beneath and above other imagery. Clashing and vibrant colors repeat.

Aguayo engages with modern painting, and he has found particular inspiration in the work of Willem de Kooning. Aguayo cites de Kooning’s Montauk Highway (1958), a painting in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, as one that he has considered in terms of its physical size as well as its scale in relation to the body of the maker and the viewer. “De Kooning was known for constantly reworking his paintings,” Aguayo writes, “but Montauk Highway possesses an urgency and freshness that makes it seem as if it was simply born into existence....” Aguayo argues, however, that “Once you get past the...first glance, a sensitively nuanced and advanced structure is revealed. Each component of the composition feels tightly and masterfully controlled, yet the painting maintains a sense of wild openness.”2

Here, Aguayo points toward a duality that intrigues him and can be seen in the grounding of his work—structure underlying the appearance of spontaneity, and spontaneity subverting aspects of formal composition. He typically sets up figure/ ground relationships and defines structures within the works, which may then be obscured by his deployment of color and materials. According to the artist, points of departure have included the edges of the canvas as the demarcation of artistic space, printed items he finds interesting, and bold fields of color. He compares his embrace of both composition and improvisation—or the planned and the accidental— to jazz, in terms of working with both structure and flow.

Within the paintings, the artist’s hand and body are referenced in the marks he makes. For example, the gestures made with a dry roller convey the movement of his arm, and blemishes and irregularities in the paint surface suggest his working and reworking of the materials. The imagery is both intentional and incidental, as are his finishes. They are recordings of his physical movement and his engagement with the works in space.

/art/a40106744/why-this-art-montauk-highway-nick-aguayo/

As much as Aguayo is primarily concerned with the act of painting, he is also an assembler. His work features ready-made and found materials. Collaged paper— cut, torn, and misshapen scraps—underlay and overlay the paint. Fabric swatches, adhesive-backed paper, and pieces of old clothes—solid, printed, and textured—find their way in as collaged layers. He fashions these materials as strips and stripes, both regular and irregular. Textured papers add dimensionality under layers of paint. Objects act as tools and templates for his visual vocabulary: For example, paint cans and their lids act as circular shaped stencils. The artist counts found color among materials ready for use. This includes paint itself, which he typically uses directly from the tube or can, without mixing. Often, these found elements are applied in broad sections, so they form blocks of color or areas of patterning, obscuring what lies beneath and creating areas of opacity within the overall spirit of the composition.

One ready-made image that has entered the work is found on the perforated metal covering of the sole window within the studio space. Aguayo stencils this ornamentation (and other similarly repeating patterns) over other imagery, and he layers it beneath various visual elements. He compares the resulting grading and shading to the semiopacity achieved through printing techniques utilizing Ben-day dots, prevalent in mid-century reproduction as well as pop art. The result is a shallowness of the image, as seen, for example, in the work of Sigmar Polke, from whom Aguayo draws inspiration, where planes appear to be compressed and flattened.

The artist admits that for a long time he didn’t recognize the centrality of this perforated window screen in his studio and, in turn, the impact it plays in his work. (It is easily overlooked amid the clutter of materials he collects, piles up, and saves.) However, it is both visually and conceptually relevant. Where windows serve as portals to the outside world and frame the view, for Aguayo this view is marked by a perforated lens.

Aguayo is also keenly aware of what is happening outside his studio: The surrounding neighborhood is a source of fascination, and the artist takes regular walks and photographs the environs. These experiences and collected materials are the basis

of his diaristic engagement with the adjacent urban landscape. The hand-painted signs, the graffiti, and the contents of the thrift shop next door (where he gets some of his bits of fabric) are among the elements that have infiltrated his art. Aguayo notes that he has observed with interest, among other things, the architecture of his block, the color of his apartment door (green), and chance occurrences and interactions on the streets of the surrounding area.

He recalls a memorable exchange he witnessed: Text appeared on the building next to his saying, “Eddie you owe me 5 fucking dollars.” After a few days, he noticed a response, of a sort: “Yeah, Eddie, give him his money.” The unfolding of this visual “conversation” across the neighborhood’s walls struck Aguayo as analogous to the way his own paintings are made: an additive, call-and-response process, with each mark in dialogue with those before as well as those that come next. (While the artist does not play chess, he often thinks of a match occurring as he works.)

This encounter highlights another potentially overlooked aspect of Aguayo’s work: time. The “conversation” and the artist’s experience of it unfolded over a few days, enough time for the “dialogue” to evolve. Likewise, inside his studio, the back-andforth rhythm of the work’s making—where one idea or mark gives rise to another and the next—takes time.

A likely assumption is that Aguayo works on everything all at once because of his compact working quarters: in other words, because of spatial constraints. However, this working method is also the result of the way he engages with time. Aguayo often references the artist Alex Katz’s adage, “Paint faster than you can think.” Yet, he builds canvases slowly and rhythmically, as he works on many simultaneously. One may advance, while another waits. The canvases take their turns. Time is seen in the syncopated flow within and among the works.

For the past decade, the artist’s El Sereno studio has been his center of activity and has provided the internal metronome of his practice. During the pandemic, however, he temporarily decamped from this hub and spent a year in La Quinta, California, where his family lives. His sparer and smaller work space there provided

a different environment and set of conditions, both formally and conceptually. Aguayo created drawings and collages, seemingly focused on color, line, form, and composition. They featured recurring elements from his visual vocabulary, including circles and dots, swaths of bold colors, and layered paper and paint, made with found color and materials, including colored pencils, markers, and whatever was available to him. During this period, Aguayo worked with greater limitations, and yet with a greater sense of freedom and more flexibility. He calls the results “permissive and promiscuous.”3

Ultimately, though, these works were framed by time: Each was made in a single sitting, and together they are markers of time’s passage. The Quarantine Drawings reflect experimentation during a period of great uncertainty and anxiety in the world at large. Time stopped, but it was also brought to the surface as an otherwise underrecognized condition in the artist’s work. It is time, as much as spatial conditions and formal patterning, that provides the structure of and framework for Aguayo’s work. An understanding of time allows and encourages the artist to work on everything all at once. And it is time that is reflected in the visual rhythms—both planned and improvisational—that are central to his practice.

Pass the Distance, 2022

Born in Palm Springs, CA in 1984

Lives and works in Los Angeles, CA

2012

MFA, University of California, Irvine, CA

2007

BA, University of California, Los Angeles, CA

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2023

Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

2019

“Wake the Town and Tell the People,” Vielmetter Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

2014

Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, Culver City, CA

2007

“Nick Aguayo: Painting Exhibition,” Undergraduate Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2022

“GENERATIONS, Abstract Los Angeles: Four Generations,” Brand Library & Art Center, Glendale, CA

“Art at Tamarisk,” Tamarisk Country Club, Rancho Mirage, CA

Blue Door Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

2021

“20 Years,” Vielmetter Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

“Truth in the Face of Reality: Non-Objective Art in the 21st Century,” Robert Berry Gallery, digital

“Via Cafe,” Tif Sigfrids, Comer, GA

2020

“poem from home” (curated by Rema Gholum), digital

“LA in Bloom: Seven Approaches to Abstraction” (curated by Maryam Parsi), Werkartz, Los Angeles, CA

“The Vista: Abstract Painting,” Durden and Ray, Los Angeles, CA

“Glyph” (curated by Ryan Schneider), Unpaved Gallery, Yucca Valley, CA

2019

“Synthesis: Some Abstraction in Los Angeles,” Claremont Graduate University, Claremont, CA

“The Flat Files,” The Pit, Los Angeles, CA

2017

“Crystal Flowers,” Index, Los Angeles, CA

“Wrong II,” PØST, Los Angeles, CA

“Vantage,” Finishing Concepts, Los Angeles, CA

“Objective / Non Objective,” Gallery Also, Los Angeles, CA

2016

“Be With Me, a Small Exhibition of Large Paintings,” New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, NM

2015

“Black / White” (curated by Brian Alfred), Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, New York, NY

2013

“Black Rabbit, White Hole,” Samuel Freeman Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

“Paradox Maintenance Technicians,” Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA

2012

UC Irvine Graduate Exhibition, LAXART, Los Angeles, CA

“A Romantic Measure,” Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

UC Irvine Thesis Exhibition, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA

“Traumatic Materiality,” Autonomie, Los Angeles, CA

2011

“My head is falling out, so I’m standing on my stomach,” Artist Curated Projects, The Armory Center for The Arts, Pasadena, CA

“Ne Me Quitte Pas,” University Art Gallery, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA

2010

“Action (Un)Packed: Abstraction After Action,” Commonspace, Los Angeles, CA

“GLAMFA,” California State University, Long Beach, Long Beach, CA

“Workspace Selects,” House on Genesee, Los Angeles, CA

2007

Undergraduate Scholarship Exhibition, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

“No Art Today,” INMO Gallery, Los Angeles, CA

Hillel Juried Exhibition, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

Senior Show, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

2014

Emerging Artist Grant, Rema Hort Foundation, New York, NY

2009 – 2012

Fees Fellowship, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, CA

2007

Edward J. and Alice Mae Smith Award, Art Department, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA

The Bronx Museum, New York, NY

Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Springs, CA

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

16 March – 22 April 2023

Miles McEnery Gallery

511 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2023 Miles McEnery Gallery All rights reserved

Essay © 2022 Rochelle Steiner Director of Exhibitions Anastasija Jevtovic, New York, NY

Publications and Archival Assistant Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Christopher Burke Studio, Los Angeles, CA

Color separations by Echelon, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by McCall Associates, New York, NY

ISBN: 978-1-949327-99-1

Cover: Soft Machine, (detail), 2022