Jonathan D. Katz

Drawing is an act of translation, transforming movement into stillness, three dimensions into two, warm flesh into cold mediums like pencil and paper. But the act of translation is hardly the artist’s alone. In viewing an artist’s works, we also translate what we see. This is an act of recognition that entails measuring anything we encounter against our own memories and experiences to yield the edges of the familiar. It is a low-impact attempt to recast the unprecedented as but a variation on what we already know.

As a technique, photorealism throws this act of translation into high relief. As we marvel at the artist’s skill with shadow, line, and pigment density, we are continuously conscious that what we are seeing is, in fact, not what it purports to be but a confabulation, an illusion so strong as to fool us into crossing the real with its representation. But if translation is the expression of sense or meaning as it moves from one medium to another, then failure is built into the process. In fact, failure is necessary, for absent failure, illusion would be simply a mirroring, mindlessly reflecting what was seen. And that, by definition, would not be a translation at all. On the other hand, if there are too many failures, then the act of translation itself fails, for translation requires moving from the actual to a new similarity or likeness.

To argue that the drawings of Patrick Philip Lee are translations seems obvious. But they are more than that; they are a kind of flypaper, trapping us into stilling the process of automatic recognition and forcing an attentiveness to their slow alternation between one medium and substance and another. They catch us catching ourselves in the arc of this movement, which is to say that they make us tarry in the space between person and portrait, as one thing is in the process of becoming another. As a drawing of a face turns into a person we can instantly recognize, and perhaps even claim to know or understand, the monochrome, textured quality of the artwork, its manifest density of marks and slow accumulation of textures amid hours of labor slow us down, enforcing a careful study of how this illusion has been achieved. We no longer stare at the totality of the portrait as a holistic thing, but register its part-by-part relations, the steady accumulation of partial effects and details as they build toward the whole.

To look at Lee’s drawings is to be a ball bearing rolling perpetually back and forth, moving between reality and illusion, stolidity and evanescence, truth and falsehood. These drawings are chimeric things, just wrong enough (they are in black and white, after all) to announce their deceptions. Such is the charge and reward of Lee’s art: to be suspended in a kind of total doubt as to what is real; or better, to know that what appears to be real is in fact not. And this play with likeness isn’t just a mental game; it’s an ethical practice as well.

There is, I think it fair to say, far too little doubt about the accuracy of our translations these days, as one thing becomes another with a mere sweep of the magician’s cape, a politician’s swagger, an influencer’s “likes.” We fly from A to Z so quickly that all the tricks, lies and conjuring, the prestidigitation and sleight of hand, get lost, and we see what we’re expected to see. To obey illusion as if it were reality has become a sad marker of our time. As argument and reason have been supplanted by personality and faith, doubt has curdled into conspiracy, but doubt is to conspiracy what blood is to a clot: free flowing, it gives life; settled and stifled, it can kill.

Amid our epidemic of conspiracy, of being told what and whom to believe, Lee freely sows doubt as a palliative. He enforces attention to the how as much as to the what, retraining ossified habits of acceptance. You can’t trust your eyes in front of his work—and that’s a good thing in a culture that is so satisfied with the appearance of veracity alone that bold lies can be perceived as truth with almost no resistance. In front of a Lee portrait, equivocation is the dominant feeling, a careful adding up of what we understand coupled with how we came to understand it that way, all moving us toward a fuller, 360-degree understanding of how illusion works.

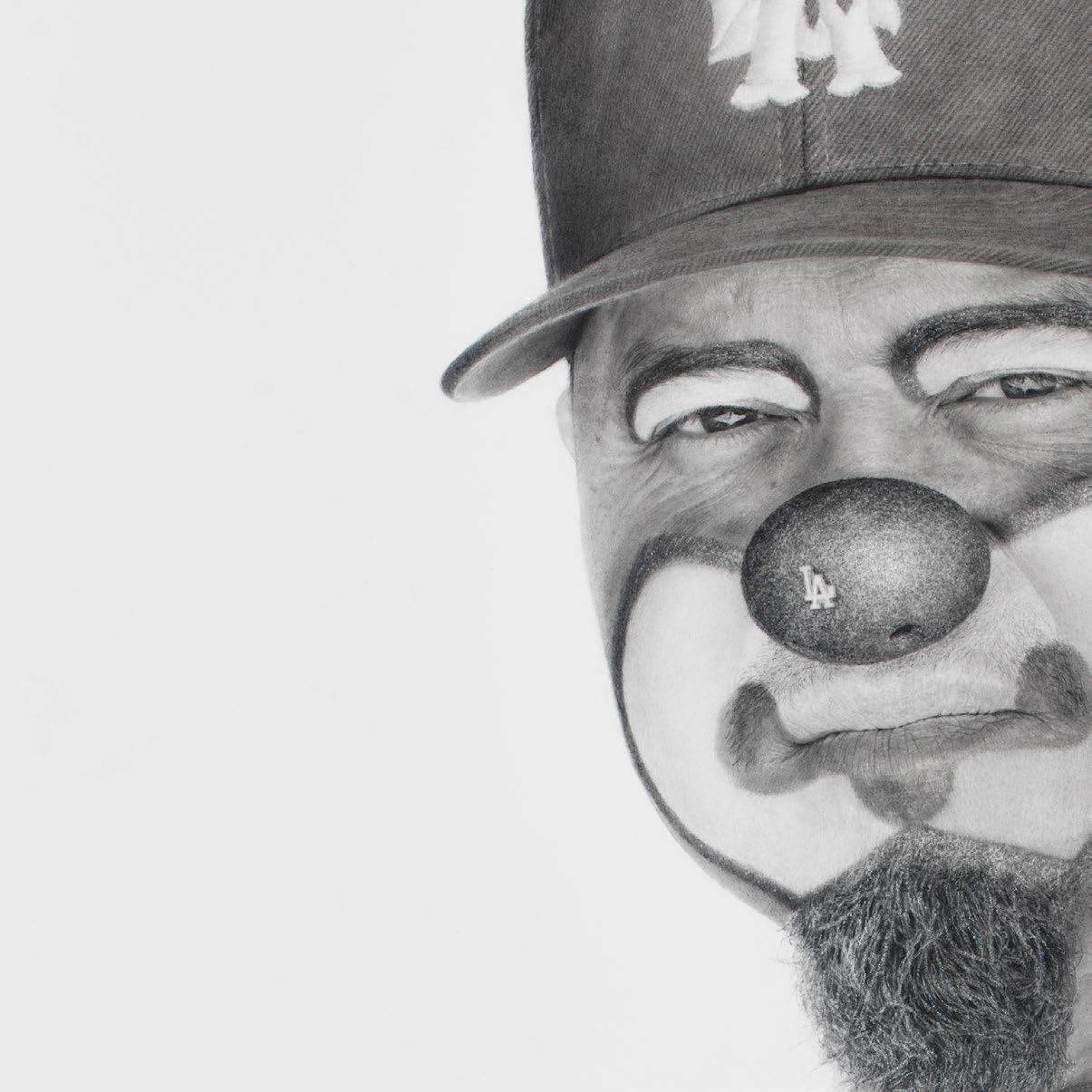

That Lee’s subjects are not what they may seem compounds our equivocation. A tough-looking, stocky, middle-aged man in a Los Angeles Dodgers cap gets an extreme conceptual makeover when grease paint and a clown’s nose are added to the equation. He’s Lee’s friend, Frank Mercado, aka Hiccups the Dodger Klown, who, Lee reports, “is a preschool teacher who also volunteers to feed and clothe the unhoused and comfort and inspire kids with cancer as well as their families.”

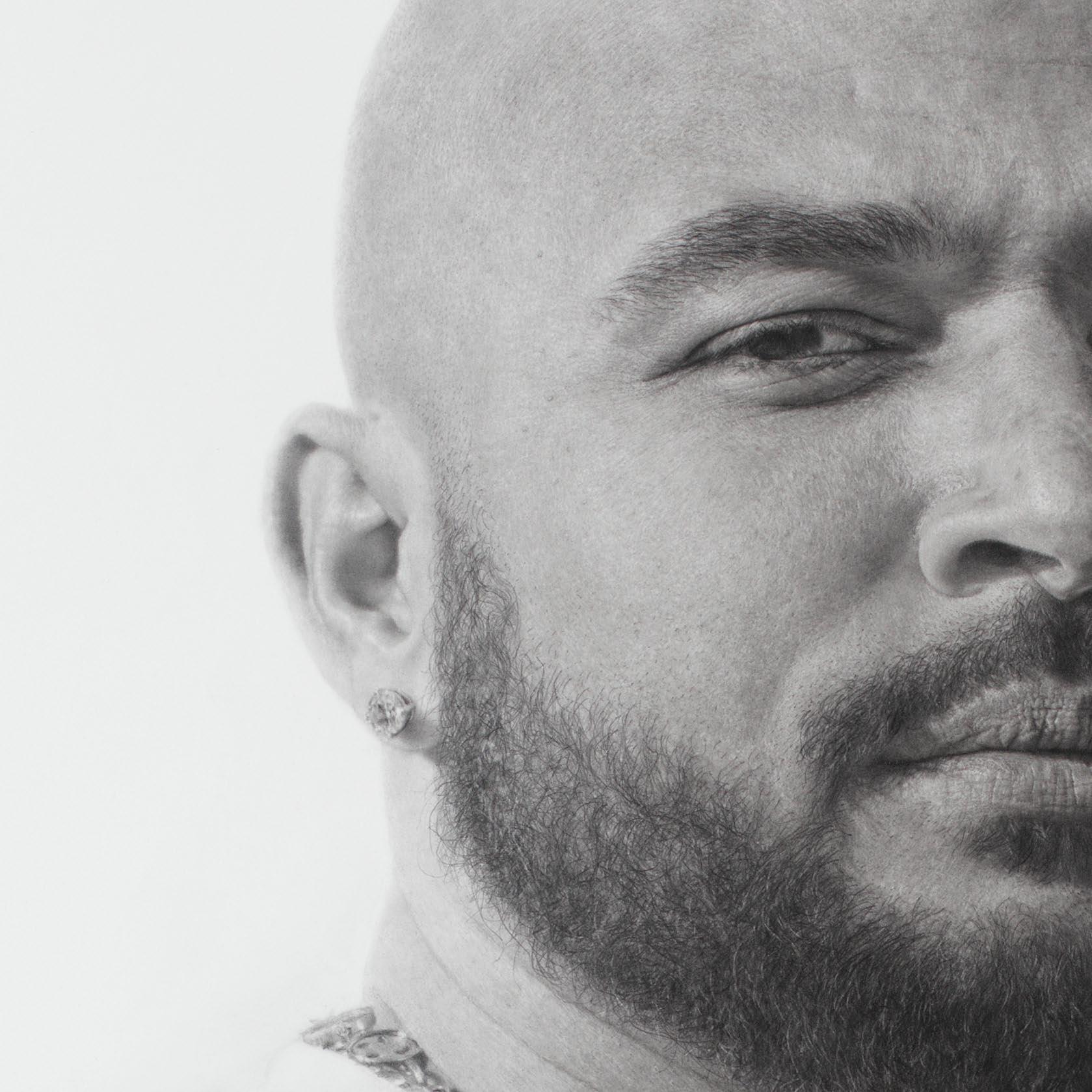

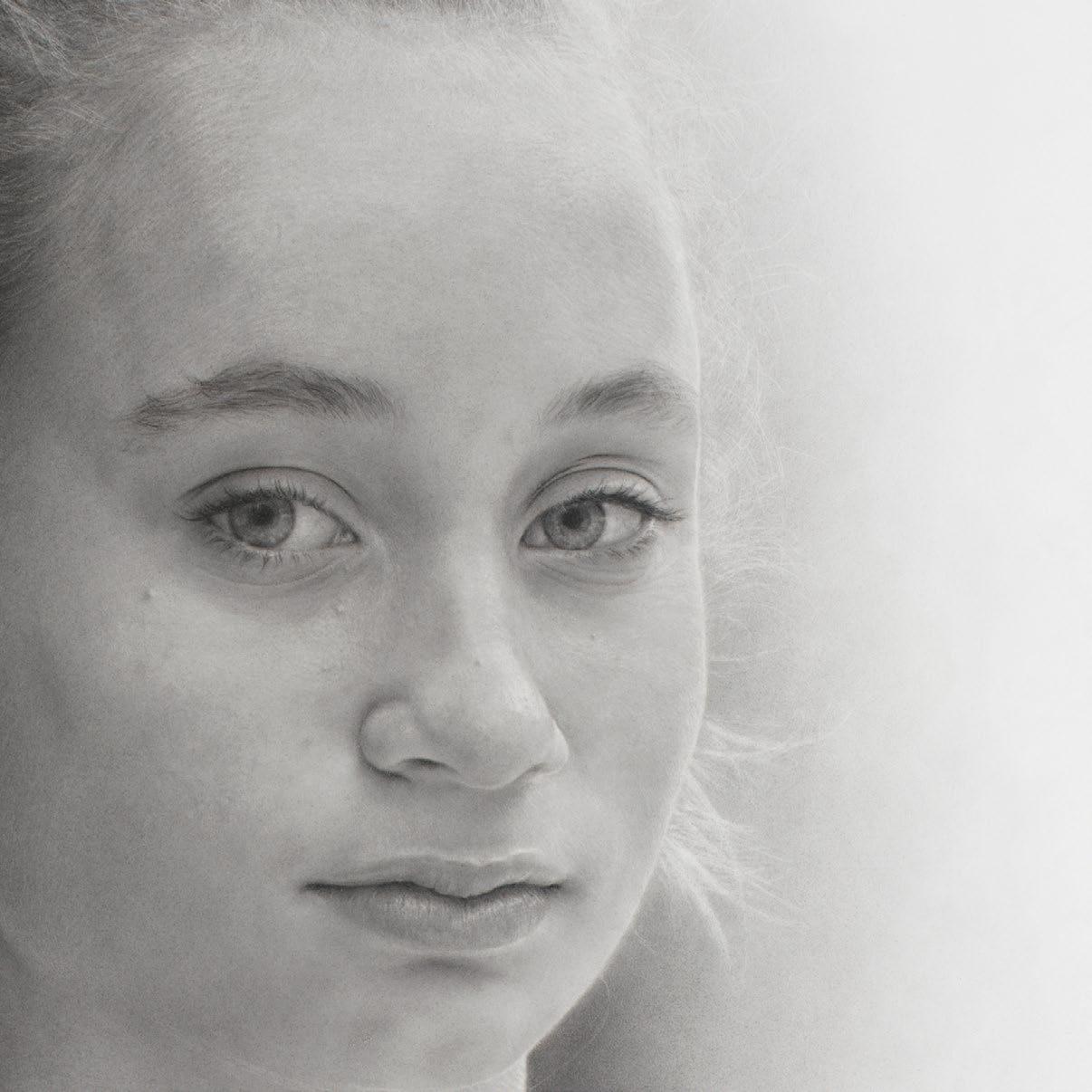

Dakotah, the bald guy with the heavy chain around his neck, looks menacing enough, but he is actually an astrophysicist at UCLA. Doubt is built into these works. Lucia, the teenage girl drawn by Lee, is the first female subject he has explored, and her portrait is a picture of contradiction. Self-conscious and confident, tentative and self-possessed, she can be the very opposite of how she seems. A storm surge of adolescent angst is visible in the suspicious questioning eyes and the firm closed-off mouth.

Of course, queer folks, such as Lee (and this writer) have long experience with translation in real life. In high school, I would try to cross my legs in a way that would avoid my being branded and called out. Or wonder how I could look at the cute jock in my homeroom without getting caught. Daily life was a masquerade, and failure to maintain the masquerade had serious consequences. Even for those who are out of the closet, there are frequent split-second decisions on whether it is advisable, safe, or necessary to declare oneself. One is constantly determining whether it’s better to play along or swim

against the tide. Only members of the empowered majority can be their authentic selves: For the rest of us, identity is a tool kit or a costume closet—choose your own gendered metaphor—that allows us to become different selves as the situation demands, in public or in private, whether at work, school, or home. Various aspects of this mobile self, the inheritance of a marginalized identity, need to be well- (even seamlessly) performed if one is to avoid being called out by power and made to pay the price. To be a minority is to translate for your life.

So Lee knows something about being misread, misunderstood, or just plain missed. And his work, in opening up the process of signifying, restores agency to viewers, asking us to ask ourselves how meaning is conveyed, and conviction is compelled, how we know what we know and if we really know it. In an earlier series of works entitled “Deadly Friends,” Lee approached strangers in the street and asked if he might photograph them as models for portraiture. The inherent risk in approaching dangerous-looking strangers, coupled with his open queerness, led some to hypothesize that Lee was attracted to danger, fetishized violence, or even had a pleasurably masochistic reaction to these fraught encounters. But these are mistranslations of a kind familiar to queer men, wherein querying the norms and standards of the performance of masculinity gets mixed up in identifying with, and even eroticizing that very masculinity.

Calling this series “Different Places” makes clear that it’s not the artist who is identifying with the subject; rather we are. Or perhaps better, we are alternating places with both the artist’s subject and the artist, engaged in seeing what Lee is seeing. To shift places is not about identity, which is a static, solid, and external thing placed over a subject. Rather, it’s about the act of identification, which is fluid, improvised and partial, a verb not a noun, always in process. To identify with someone is a radical form of empathy that causes differences in identity to fall away in favor of similitude. It is also a radical act of sympathy, a forging of a bond that supersedes manifold external and internal differences and acknowledges what is shared. We can and often do identify with people who are manifestly different

from ourselves. To do so entails a kind of translation of our experiences into what we take to be theirs.

And that, finally, is my point. To translate from my experience to another’s isn’t an appropriation of their experience, for how can I appropriate what I don’t know? It is rather a projection, a makeover, a sharing of emotion that is profoundly intimate. Whether the translation is accurate or true is beside the point; what matters is that we take on another’s subjectivity as if it were our own. After all, to translate is to try to speak in another’s language. And in recognizing what we share, how we are alike despite our differences, translation replaces a framework of difference with a framework of commonality. This is a species of love, and Lee’s portraits are absolutely infused with it.

Jonathan D. Katz, Professor of Practice, University of Pennsylvania.

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

UCLA Astrophysicist, Culver City, 2024

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

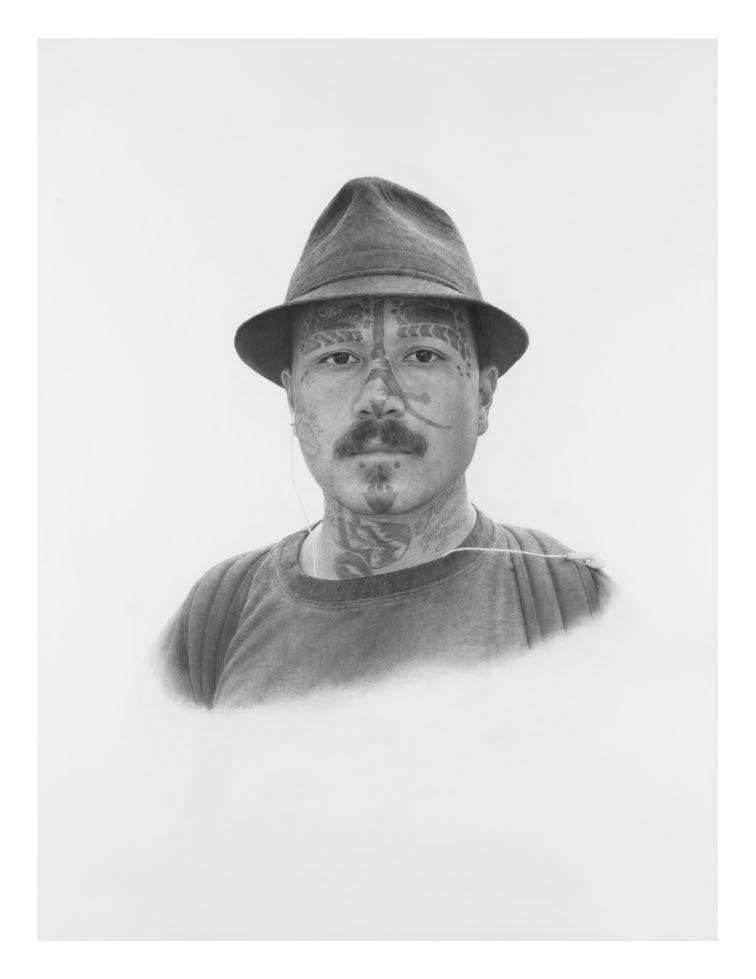

Hiccups aka Frank, teacher, community organizer and activist, Silver Lake, 2024

Graphite on paper

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

Jess, creative director, multi-media artist and designer, West Adams, 2024

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

Lucia, 13-yr-old student, Pasadena, 2024

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

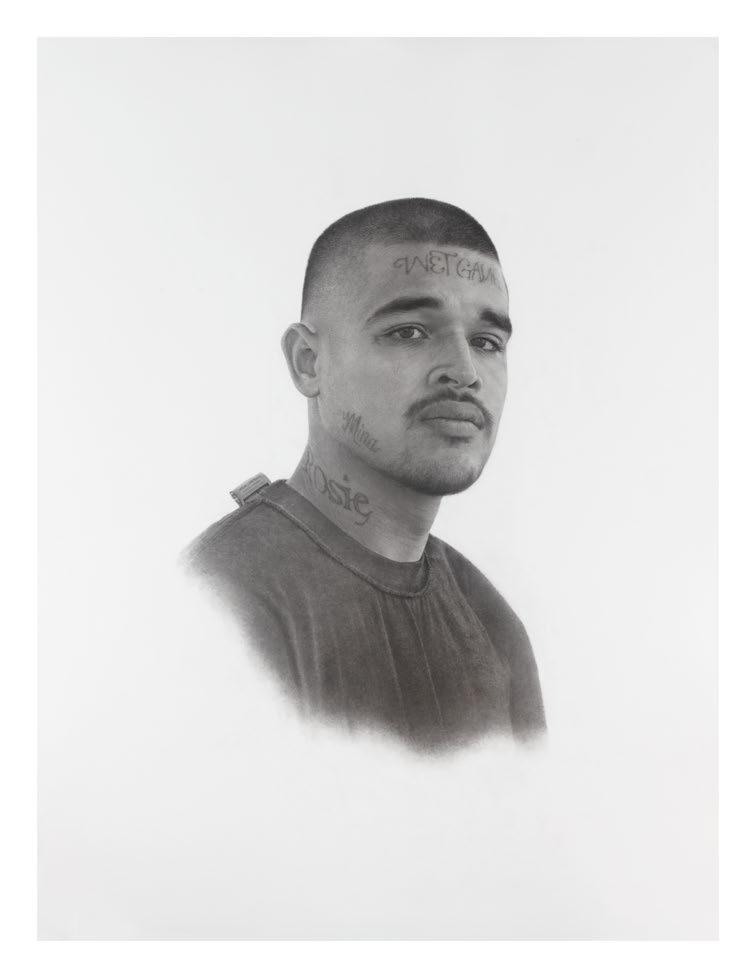

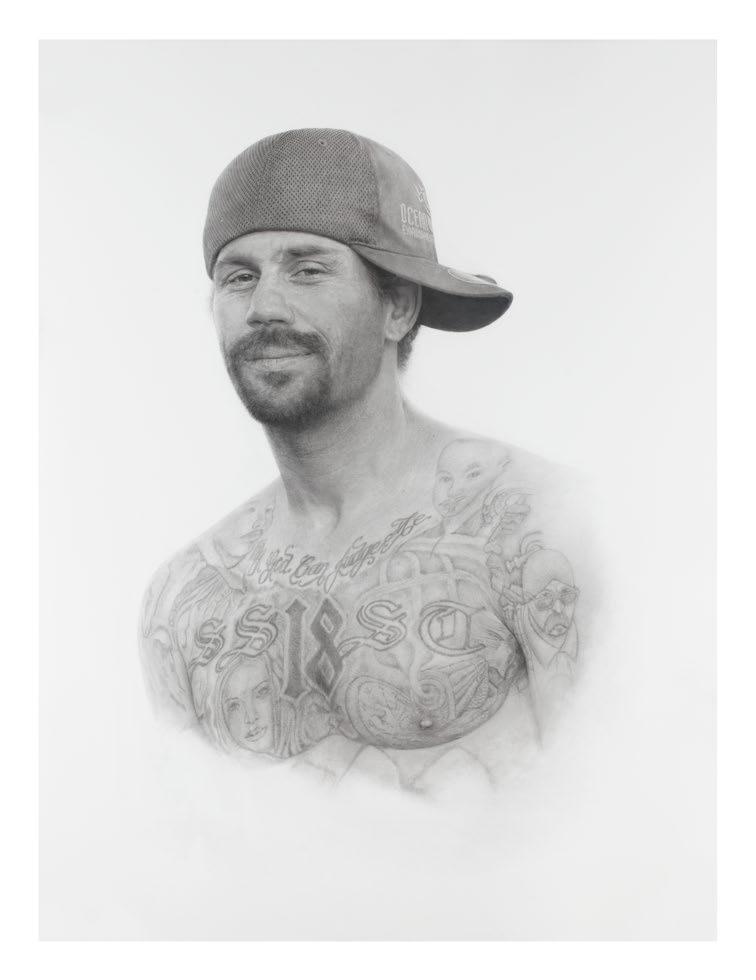

Mike, professional tattoo artist, Eagle Rock, 2024

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

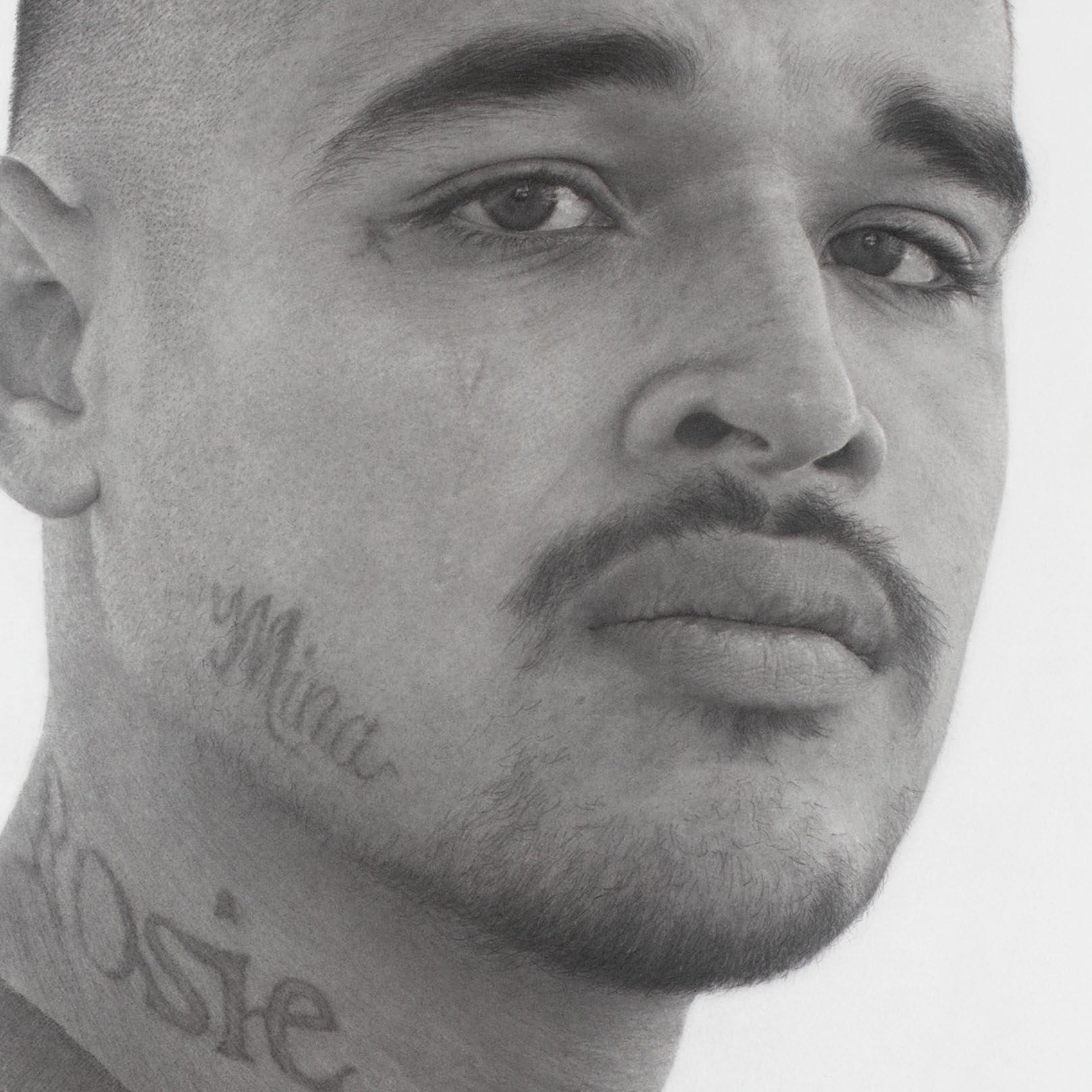

Tim, ex-con, Palm Springs, 2024

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

31 October – 7 December 2024

Miles McEnery Gallery 515 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2024 Miles McEnery Gallery All rights reserved

Essay © 2024 Jonathan D. Katz

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Christopher Burke Studios, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 79-8-3507-3964-0

Cover: Dakotah, UCLA Astrophysicist, Culver City,(detail), 2024