TOMORY DODGE

FREEFORM: TOMORY DODGE’S SQUARE WAVES AND GLITCHES

Daniel Gerwin

Over the last three years, Tomory Dodge has developed a private sidebar in plein air landscape. Small scenes of forests, hillsides, flowers, and night skies fill the walls of a secondary studio. They are exquisite, displaying the sensitivity to chromatic relationships that makes this artist’s well-known abstractions so compelling: precise juxtapositions of hue and saturation make his colors vibrantly alive. Dodge’s recent adventures working from observation coincide with the almost complete disappearance of references to the natural world in his nonobjective paintings, a process that was already evident in his 2023 show at the Philip Martin Gallery in Los Angeles. In that exhibition’s works, entire visual fields were suffused with dots, zigzags, or parallel lines to create flat surfaces divorced from the spatial depth of three-dimensional depictions.

Dodge’s new paintings continue his journey away from horizon lines and other hallmarks of landscape space. Instead, he uses formal visual effects to create an optical experience of depth in a universe without gravitational force. Talking in his studio, Dodge speculated that making observational images has scratched his representational itch so successfully that he has found greater freedom to deepen an engagement with abstraction over the past four years. Even his palette is removed from nature, drawing instead from psychedelia (a childhood friend of Dodge’s had a book of 1960s posters that Dodge loved) and artificial light.

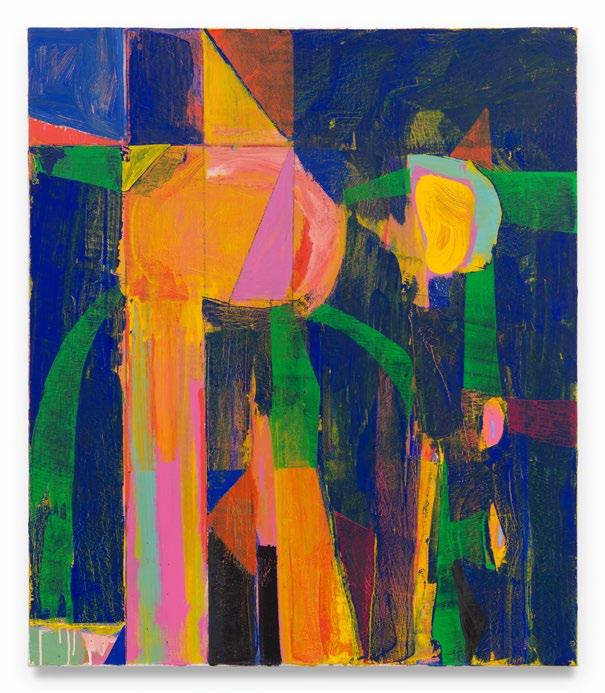

Dodge packs three distinct elements into the new paintings:

First, there is what Dodge calls a “square wave” moving horizontally across the canvas. (In his 2024 painting Pink Panther, it traverses vertically.) The pattern resembles sine waves in which the curves are rectilinear, a thick line traveling up and down in abrupt 90-degree angles. The wave starts off small at the canvas’s top edge, then becomes increasingly larger while it proceeds lower, as if Dodge were a kid trying to complete a one-page writing assignment by making his letters bigger and bigger. The shift in scale creates a subtle perspectival effect; the heftier forms toward the bottom seem to be closer, and the smaller forms up top seem to be farther away, as in a traditional Chinese scroll.

Second, Dodge fills the rectangle with closely packed zigzagging lines running vertically up and down. (There is one horizontal exception, the 2024 painting Bong.) The color relationships between the square waves and the zigzag patterns are tuned to produce intense retinal buzz. It’s as if Josef Albers had dropped acid before picking up his brush.

Third, Dodge includes what he calls “glitches” in the visual field: messy patches reserved from the canvas’s first layer that have generally been scraped to a blurry haze. The glitches interrupt the image’s dominant patterns and disrupt its prevailing logic (as in the 2024 painting Breakfast In Bed). The vibrating hues of the zigzag patterns are so powerful that if you look for even a minute the glitches seem to float free, hovering about a foot in front of the canvas. Yet Dodge is committed to keeping his paintings on the surface: He periodically tosses little globs of paint onto the canvas, where they lie like spat-out chewing gum on a sidewalk, reinforcing the picture plane, lest you be taken in by the artist’s considerable illusionistic powers.

The syncopation of the three fundamental pictorial features is musical. Dodge has been hacking around on drums, guitar, and synthesizer since he was a teenager, and he clearly has a strong sense of rhythm. Each of these new works possesses a distinctive synesthetic arrangement of beats, derived from the square waves’ percussive dance across the surface (they actually resemble sound waves) and set off by the zigzags’ manic rush along the opposite axis. Both cadences are accented by the popping treble notes of the glitches. If the paintings were songs, they might be club music. In fact, the

Bridget Riley, Blaze I, 1962, Emulsion on board, 42 x 42 inches (106.7. x 106.7 cm). National Galleries of Scotland. Long loan in 2017

M.C. Escher, Development I, 1937, Woodcut, Cornelius Van S. Roosevelt Collection

freewheeling way in which Dodge lays down his zigzags reminds me of the short dashes and curving lines Keith Haring used to animate his figures, often making them dance.

Every rule has exceptions, and in this new body of work there are two: Bong (2024) and Dessert Island (2024). Both paintings are built on a single zigzag pattern; neither includes an additional square-wave as a transverse layer. In this regard, they resemble December Boys (2023), a somewhat anomalous painting from Dodge’s previous show at the Philip Martin Gallery. December Boys and Bong share key characteristics: Each is composed of alternating rows of blue and black zigzags stretching across the canvas to create a nocturnal mood, and both are interrupted by large organic shapes in pink and orange hues, as well as other geometric forms in assorted colors that play a small part in December Boys but become dominant in Bong. The close relationship between these paintings is a juicy little revelation, showing how visual ideas weave in and out of the painter’s consciousness as he explores their core subject, taking little side trips off the central highway when something compelling is discovered.

Dodge has long admired the art of Bridget Riley, who helped spark the Op Art movement in the 1960s and ’70s but ultimately transcended it. Her influence on his recent work is clear in such paintings as Riley’s Blaze 1 (1962), in which closely packed undulating lines create a powerful hum and optical illu-

sions. While Dodge executes his zigzags in a way Riley would consider unforgivably lax, they cannot help but kick off the hallucination of steps ascending diagonally up the rectangle, reminding me of the artwork of M.C. Escher or the Q*bert arcade game of my misspent teenage years. James Siena’s work provides another interesting comparison because, like Riley, Siena sets up rules for each painting that he follows rigorously. The result is maze-like arrangements of line and carefully calibrated color. Siena’s horizontal wave structure in Infolded Ridgeling (2020), with its pattern flowing horizontally across the visual field and going haywire in the center, could almost be the scaffolding of one of Dodge’s newest paintings.

Whereas Riley and Siena are precisionists in painterly execution—and unerringly loyal to the system they establish for any given painting—Dodge stays loose, improvising with his chosen pattern. This inevitably leads to deviations that require solutions on the fly. This process is most evident in his approach to the zigzags: Dodge typically begins a pattern on one or two edges simultaneously and works his way in. Because he wields his brush freehand rather than following pre-drawn lines or tape, the motif gets wonky as he fills the canvas. The resulting “errors” are resolved spontaneously—adding diamonds, rectangles, or more irregular shapes to allow the unaligned zigzags to synch up (as in the 2024 painting Telephone Tells Me). Dodge plays with this device by shifting his starting points to great effect. In Mental Physics (2024), he starts the pattern in three locations: on the left side, on the right side, and from the middle, so that the irregularities occur in two columns, each a third of the way

James Siena, Infolded Ridgeling, 2020, Acrylic and charcoal on linen, 36 x 48 inches (91.4 x 121.9 cm)

across the painting’s horizontal axis. Like many good painters, Dodge takes his canvases right up to the edge of the cliff by breaking down the zigzags and further interrupting the imagery with seemingly random glitches. A lesser artist would fall into the chaotic crevasse between Riley and free jazz, but Dodge pulls it off.

Growing up in Denver in the 1980s, Dodge had a habit of drawing in front of the television set, often sitting close to the screen. The family had an old-school TV with reception provided by rabbit ears, rather than a rooftop antenna or a cable connection. This resulted in all the low-fi static and pixelation that were signatures of the cathode ray tube experience. The tendency of Dodge’s zigzags to fall apart and reconstitute, along with the glitch passages and paint blobs, all hearken back to the fuzzy images of his pre-digital youth, summoning memories of “falling in love with drawing in the presence of a screen,” as he put it to me. That was a more innocent time, when signal-to-noise ratios were obvious, even on a crappy set. Now we live in an era of high resolution and AI deep fakes—you can believe nothing you see, no matter how authentic it looks.

We consume content on YouTube, TikTok, and the like, all tailored in advance so it fits corporate algorithms to maximize exposure and thus revenue, meaning that thoughts (to the extent they can be found) are pruned beforehand in accordance with the laws driving what is likely to go viral. All of this is to say that there is value in Dodge’s decision to interrupt his paintings drive toward seamless coherence. His approach to image making advances a skepticism of any single answer, doubling down on a refusal of our twenty-first century embrace of ideological purity (on both the left and right)— along with a rush to cancel those who dare to violate prevailing strictures. Dodge’s new body of work advocates an understanding of the world that does not include the high-polish gleam of the snake-oil salesman, nor does it require everyone to get in line. It makes room within its entropic environs for a good deal more freedom.

Daniel Gerwin is an artist and critic whose writing has appeared in publications including Artforum, Frieze, The Brooklyn Rail, and Hyperallergic. He has been a MacDowell Resident Fellow and taught at universities throughout the country.

56

Almost Famous, 2023

Oil on canvas

22 x 18 inches

x 46 cm

December Boys, 2023

84 x 84 inches

213 x 213 cm

Oil on canvas

229

Medicine King, 2023

Oil on canvas

90 x 72 inches

x 183 cm

72 x 60 inches

183 x 152 cm

Spook 2023

Oil on canvas

The Riffraff, 2023

Oil on canvas

60 x 40 inches

152 x 102 cm

72

183 x 152 cm

Venusian Blind, 2023

Oil on canvas

x 60 inches

183

Visitor, 2023

Oil on canvas

72 x 50 inches

x 127 cm

Austral, 2024

35 x 30 inches

89 x 76 cm

Oil on canvas

80 x 72 inches

203 x 183 cm

Bad Lands, 2024

Oil on canvas

54

48 inches

137 x 122 cm

Bong, 2024

Oil on canvas

x

183 x 152 cm

Breakfast In Bed, 2024

Oil on canvas

72 x 60 inches

22

56 x 46 cm

Bunny, 2024

Oil on canvas

x 18 inches

122 x 122 cm

Dessert Island, 2024

Oil on canvas

48 x 48 inches

22

56 x 46 cm

Heat Dome, 2024

Oil on canvas

x 18 inches

Mental Physics, 2024

72 x 60 inches

183 x 152 cm

Oil on canvas

Midnight Radio, 2024

Oil on canvas

30 x 25 inches

76 x 64 cm

Pink Panther, 2024

Oil on canvas

54 x 48 inches

137 x 122 cm

Solar Technology, 2024

35 x 30 inches

89 x 76 cm

Oil on canvas

30 x 25 inches

76 x 64 cm

Sometimes, 2024

Oil on canvas

Telephone Tells Me, 2024

Oil on canvas

60 x 60 inches

152 x 152 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

TOMORY DODGE

31 October 2024 – 7 December

Miles McEnery Gallery 511 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2024 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2024 Daniel Gerwin

Photo Credits:

p. 5: © Bridget Riley 2024. All rights reserved

p. 5: © 2024 The M.C. Escher Company-The Netherlands. All rights reserved. www.mcescher.com

p. 6: Courtesy of the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY

Associate Director

Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Christopher Burke Studios, Los Angeles, CA

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-3858-2

Cover: Breakfast In Bed,(detail), 2024