Leading with

A magazine containing reports and stories, opinions, interviews and analyses of questions concerning nature, cities, and our future way of living

Vol. 1

Leading with landscape Vol. 1

LAND

December 2021

Publisher Andreas Kipar

Concept

Andrea Küpfer

Editing

Andrea Küpfer

Henning Klüver

Design

Tim Santore

Photography consultancy

Ralph Richter, Düsseldorf

Copyright of the texts by the respective named authors landsrl.com

DIVERSE AND INTERGENERATIONAL

WHERE ARE WE GOING?

These are truly turbulent times. The pandemic has shaken us and shown us our limits. On the other hand, it‘s given us a chance to reflect, to ask questions with no quick answers, to understand that we can’t go back to business as usual. It’s also given us an opportunity to look at our own actions as the demands of sustainability require us to intervene in processes of social transformation, with even more intervention required in the future. The great challenges of human-induced climate change call us to duty, as does our responsibility to future generations who are clamoring for their right to a future.

We are “leading with landscape” into a future conditioned by nature, which we cannot foresee but which, step by step, we can shape. In this magazine, we’re attempting to see where we stand. And where we stand is expressed through our multifaceted environment and the heterogeneity of our work. As individuals, even our most well-intentioned projects would remain ineffective. We can only be successful if we can network with men and women from our field, with our clients, our partners. We only have a future if we‘re in close communication with people from the world of art, science and politics. And so the topics and voices reflected in this magazine are both diverse and intergenerational.

The landscape consultancy LAND that I founded with Giovanni Sala in Milan in 1990 is now over thirty years old. LAND: Landscape – Architecture – Nature – Development. Through hundreds of projects, we’ve explored the landscape for the people who live in it and with it, carefully cultivating and shaping it in a variety of ways. We seek a constant dialogue that must not be allowed to falter, including within the company. A dialogue that keeps us moving, that invigorates our organization. Architect Jens Hoffmann came on board in June 2020, strengthening our management to work at my side as COO, and now attorney Marco Pazzaglia joins us as CFO. But it is the creative imagination, the creative power of all LAND employees that brings our mission to life: “Reconnecting people with nature.”

Andreas Kipar

QUESTIONING LANDSCAPE –UNDERSTANDING AND THINKING AHEAD

Landscape architecture in a changing late-modern age By Andreas

Kipar

Experiences of a young landscape architect By Stella-Zoë

Schmidtler

Space for people –an educational path By Tommaso Bassetti

Man, nature and landscape

A conversation with Philipp Blom

Three decades of green Wunderkammer a project by LAND

LANDSCAPE AS MEDIATOR –URBAN AND RURAL SPACE

The green infrastructure of the city of Saskatoon By Tyson McShane

Renfro

Renfro

Thoughts of an architect from NY By Charles

En route to the future Green dreams in Sardinia

Across borders A talk with Andrea Gebhard

Düsseldorf: Live close Feel free A conversation with the Mayor of the State Capital, Stephan Keller

Solutions of the LAND Research Lab By Andrea Balestrini

Stories from city and country

Personal experiences

38 18 08 12 C O 42 37 26 28 N 32 22 35 21

LAND SCAPE

Traveling Switzerland’s wintry crossings By Federico Scopinich

The prospects of new technologies

A conversation with Josef Nierling

A conversation about the future The directors of LAND

Piazzale Loreto and retail Meeting Marco Balducci

The value of landscape By Marco

Pazzaglia

Networking for greater sustainability Meeting Evelyn Oberleiter

The multi-layered landscape By Jens Hoffmann

Nature's parameters An exchange of ideas with Andreas Moser

T TLANDSCAPE AS VALUE –LIVING AND WORKING

Environmental goals in everyday life By

Ilaria Congia and Martina Erba

Art, nature and the wide field Tanja Schug and Thomas Schönauer in dialogue

The role of foundations A conversation with Stefan Schurig

From Riyadh to Montreal International biodiversity

61

54

68 58

63 N

E

70

48

76 44 66 74 72

QUESTIONING LANDSCAPE –UNDERSTANDING AND THINKING AHEAD

Landscape in late modernity and in a future that cannot be known but shaped by an evolutionary process

Ca' Corniani Estate (Genagricola) in the Venetian lowlands (Caorle)

© Genagricola, photo by Francesco Galifi

Questioning

landscape –

Understanding and thinking ahead

08

Andreas Kipar, Piazzale Loreto (Milan) – an emerging square

© LAND, Photo by Ralph Richter

Andreas Kipar, Piazzale Loreto (Milan) – an emerging square

© LAND, Photo by Ralph Richter

THE DAWN OF A NEW ERA

Landscape architecture in a changing late-modern age

BY ANDREAS KIPAR

“Come, friend, out into the open!” Thus begins “The Walk to the Country,” Hölderlin‘s famous early nineteenth-century elegy. But today it’s hard to find this direct access to nature, in large part because industrialization has created a rift, has caused us to trample it underfoot. We can’t just snap our fingers and expect to be welcomed back. Nature needs time. And we need time to care for it and shape it.

Landscape architecture long ago transcended the garden fences of the past. Open space has become pivotal to a new understanding of landscape. The Council of Europe's "European Landscape Convention" (signed in Florence on Oct. 20, 2000) emphasizes that landscape is an important part of the quality of life for people everywhere: “in urban areas and in the countryside, in degraded areas as well as in areas of high quality, in areas recognised as being of outstanding beauty as well as everyday areas.” Here, landscape is no longer seen as a passive object of social action, but as a basic component of Europe’s natural and cultural heritage, making a significant contribution to the formation of local cultures.

Good landscape architects, wrote Kristin Feireiss for the Berlin exhibition on LAND and Milan's “Green Rays” (2009), have two extraordinary qualities: “a far-sighted perception of time, and patience.” At that time we’d gone a long way in putting the cultivation of nature and the landscape at the forefront of city and regional planning processes. “Land in Sight” was the motto of the Berlin exhibition. More than a decade later, under the increasingly urgent challenges of climate change, the digital revolution, new mobility concepts and social isolation, the benchmarks have changed: Instead of “Land in Sight,” it's now “Land in Transition, Land in Transformation.”

A new age is dawning. Landscape architecture has consciously stepped into the late-modern age’s processes of social change, tackling vital issues that revolve around soil, water and air, but also empathy, social identity and community. In the digital age, digital networking is just something we do, not an end in itself. Networking is now what enables communication between people and places, rather than the linear, programmatic way of thinking, now finally abandoned,

10

–Understanding

thinking ahead

Questioning landscape

and

that characterized the 1990s. Non-linear, systemsoriented thinking and circular management and planning will be part of what we do. It won’t allow us to manifest our vision immediately, but only to work our way toward it, step by step.

We‘ll face challenges, find solutions, and further develop them using nature-based solutions. It’s about new forms of coexistence, and ultimately about increasing the resilience and quality of life in our urban and rural systems. We must never lose sight of the fact that our projects also outgrow us. Because landscape was there before us and will be there after we’re gone. But it only continues to live if it changes, renews itself over time. Just as nature does through its cycles of growth.

We offer landscape consulting with the goal of approaching it in terms of sustainability, which we want to make both visible and measurable. As human beings, we depend on nature. It is unique and essential. Caring for nature means caring for ourselves. This becomes a moral duty in the Anthropocene. Yet nature alone does not necessarily create humane, livable conditions; the biotope is asocial. This duty also makes us aware that designed nature is nature shaped by human hands. We once again become a part of nature, which for too long we disdained as something alien - an epochal change!

“Reconnecting people with nature!” The opportunities of this shift must not be squandered. Every landscape “has its own particular soul, like the person who lives across the way,” said author and poet Christian Morgenstern. This is a unique opportunity to reorient ourselves in this time of transition, to take responsibility and finally to take our place. On this journey, traveling with our sustainability compass, we won’t be alone. We‘ll open up. We‘ll learn to listen to young people. We‘ll share experiences, expectations, hopes. And we‘ll need a good tailwind along this path that weaves together so many fields. So many fields – what we call landscape.

Friends: come out into the open!

»A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY TO REORIENT OURSELVES IN THIS TIME OF TRANSITION, TO TAKE RESPONSIBILITY AND FINALLY TO TAKE OUR PLACE.«

Questioning landscape

Understanding and thinking ahead

AN ABSURDLY INFLATED SENSE OF SELF DIFFICULT

CONNECTIONS, CONFLICTRIDDEN

RELATIONSHIPS: MAN, NATURE AND LANDSCAPE

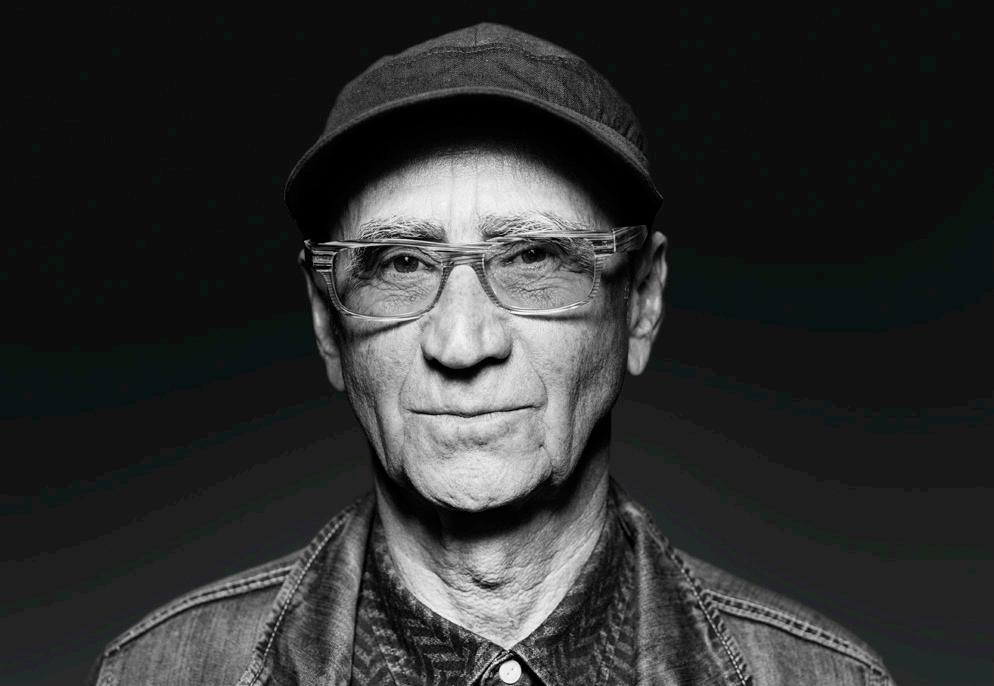

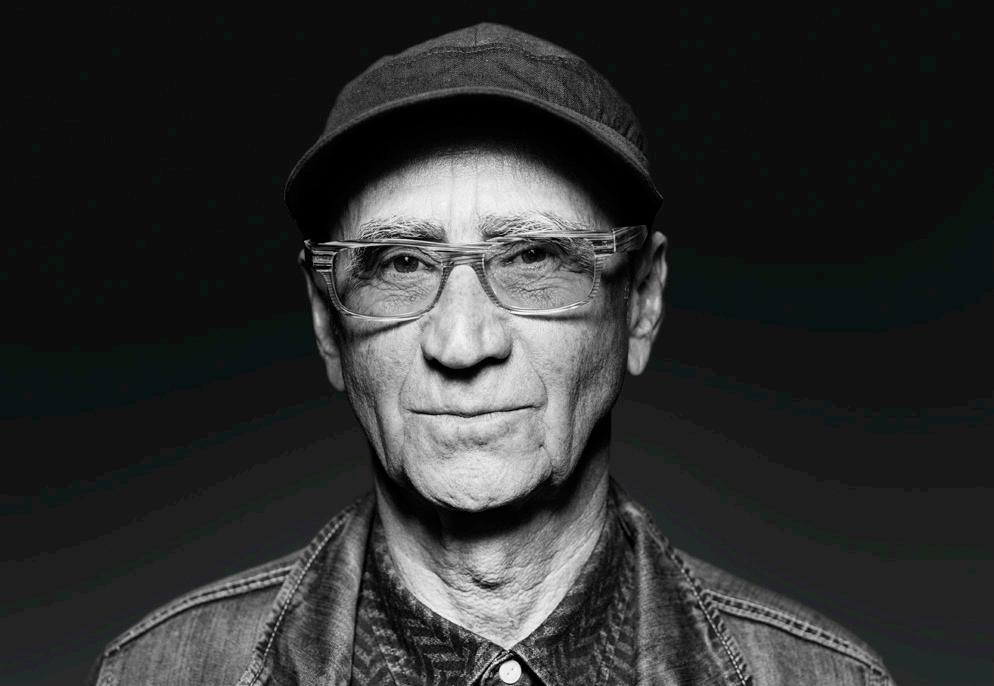

A conversation with the Viennese historian Philipp Blom

(*) Philipp Blom: "Eine italienische Reise. Auf den Spuren des Auswanderers, der vor 300 Jahren meine Geige baute." Munich (Hanser) 2018

Latest works by the author: "Was auf dem Spiel steht". Munich (Hanser) 2017 "Das große Welttheater. Von der Macht der Vorstellungskraft in Zeiten des Umbruchs". Vienna (Zsolnay) 2020

12

–

Landscape is a broad field in the truest sense of the word – where would you begin?

According to an analysis published in “Nature” magazine (Dec. 2020), the mass of man-made things exceeds the mass of natural things (biomass). Are we suffocating ourselves? What effect does this have on the relationship between man and nature? Are we now imprinting our understanding of nature on the landscape? Can nature become an antidote to a digitally alienated world?

These questions are presented in a conversation with the historian and essayist Philipp Blom. Born in Hamburg in 1970, he studied philosophy, history and Jewish studies in Vienna and Oxford, and now lives in Vienna. Questions to Philipp Blom:

In a discussion of landscape, what’s important to me is this: I believe we’ve reached the end of 3000 years of cultural history. We’ve reached the end of this epoch that began with the idea of subduing the earth. That was already a concept: it wasn’t just from the Bible, but this idea that we’re outside and above nature is coming to an end as a result of climate catastrophe. We see that it’s empirically false. And we see that our old explanations are less and less in line with reality.

Can

you say something

about the relationship between man and earth, man and nature?

Pursued in a sort of hubris?

This already throws us into the language trap. To depict man and nature as two different things is manifestly wrong. What interests me about the biblical phrase is that it constructs a relationship that in its time was an absolutely mythic atom bomb. What did our neighbors think, at the time the Bible was written? Let’s take the Greeks. Before they set sail, they had to make sacrifices to Poseidon so he would show them favor. All deities, all furies, demons, spirits, nymphs etc. represent the forces of nature, they have their own intentions and they interact with people. Sometimes through rape or abduction, sometimes by doing good things. But it’s an understanding of the enduring interaction with the forces of nature. And an understanding of the fact that this nature has power and can exert its power over our lives, and that we have to come to terms with these natural forces, in which everything is animated. And then the Bible arrives and turns them into dead matter in a very patriarchal way. So nature is dead dust, it can be possessed, bought, sold, plowed, penetrated, it has nothing to say, it has no interest, no energy, no power. This is the relationship we’ve pursued.

Everything that we create is nature, is evolution. The problem lies partly in thought but also partly in semantics. So we can talk about spirit as if it could exist separate from the body. So we can talk about there being man and nature as if it were a contradiction. And we can rise above and out of this nature and look down at it from the outside. It’s very seductive, it’s naturally also very flattering to us as a species, but it‘s intellectually very destructive. Epistemologically very destructive, because we are simply creating a false contradiction and giving ourselves an undue sense of grandeur.

And that complex system is now blowing up in our face.

We are part of a gigantic and complex system, a seemingly unimportant part of it, not even as important as fungi or algae or plankton. But we construe ourselves as not only an equal partner, but actually the ruler of all.

It’s blowing up in our face, but it’s so baked into our thought structure and speech, into our entire cultural experience, that it becomes incredibly difficult for us to break free of it. But that’s exactly the challenge we now face. That’s why this topic is so fascinating to me, because landscape is right in the middle of it. Sometimes landscape also plays with wildness, with the feral. English landscapes like to do that, French landscapes or French gardens try to do the exact opposite. Even the concept of landscape - where is the wildness, where does it begin, where is dominance achieved? Those are questions that are incredibly relevant right now.

How are nature and landscape related?

Landscape is always a construct. When working on my Italy book (*), it became clear to me that before the eighteenth century, before Rousseau, the Alps weren’t beautiful, they weren’t sublime, and they weren’t primordial, they were a death zone, they were like the Sahara. People tried to get over them fast, and not everyone made it. There were not yet any carriageways. This idea that landscape is sublime, primordial, that it connects us to something, that is of course an idea of alienation. That’s an idea that comes from the contradiction that we no longer live in the landscape and through the landscape or on the land and through the land, but rather that the landscape has become an object of aesthetic admiration and of course also an object of aesthetic construction. Sure, there are watercolor sketches by Altdorfer and Dürer that show what they actually saw during their travels. But of course, the vast majority of landscapes were created in the studio and were allegorical and did not depict an actual piece of land, but rather a universal landscape with a river, mountains, and a city and all features required to depict the wholeness of the world –never a realistic landscape. And as time went by, people began to believe that this was a true depiction of nature. Which always included people, so nature without people obviously made no sense, it wasn’t worthy of note. That first changed with the Romantic period, though even Caspar David Friedrich often paints people – at least from behind. But the idea of landscape breaking free from being an object of aesthetic admiration, that came very late. And with it a feeling of superiority on one hand and loss on the other.

14

Questioning landscape –Understanding and thinking ahead

»OUR

GREATEST

COMPLETELY NEW UNDERSTANDING OF OUR

IN

COMPLEX

CHALLENGE IS TO COME TO A

PLACE

THIS

WHOLE.«

Philipp Blom © LAND,

Photo by Sabine Biedermann

So does it have to do with caring

Is today’s increased longing for nature also an antidote to the digital world?

No, it’s about a much more radical humility. We’re not a particularly important animal in this gigantic system. It’s not dependent on us, but rather we on it. We’re not good shepherds who tend nature and can do things and control them. We’re dependent on nature, and these systems are so complex that we’ve barely begun to grasp and comprehend one or two percent of their complexity. Which is why geoengineering is such an absurd idea. How can we intervene in systems whose complexity we absolutely cannot comprehend, in terms of either space or time? The idea of 'subduing the earth' has become a shallow concept that’s resulted in an ever-growing global market, a dogma of eternal growth, eternal control and domination. And we’ve reached our limits. We live in a world in which enough rain forest to fill 30 football fields is destroyed every minute, and it’s obvious that this cannot go on for even one decade more. We’re not destroying nature, which in 300,000 years will look wonderful again, except for ourselves. But we’re changing systems in ways that make it impossible for us to live in them anymore. Our greatest challenge – and it is actually an evolutionary challenge, an existential challenge –is to come to a completely new understanding of our place in this complex whole.

It’s clear that anyone who interacts with nature, who ventures a little bit away from very artificial surroundings, can begin to feel it within themselves. Simply put, an environment that speaks to and soothes our evolutionary experience makes us feel more in tune with our surroundings and ourselves than an environment that does not. Here as well, we are victims of a rapidly accelerating history. I think we are seriously underestimating the psychological effect on us of the digital world. The digital world is rule-bound. Maybe the algorithm’s built-in random generator does something interesting once in a while, but the digital world basically makes us unfit for the outside world. Because the outside world is neither fair nor meaningful, it’s haphazard, and we’ve got to learn to improvise in order to deal with it. I think this is something that people who live from and on the land experience daily. Because something is always happening, a hailstorm comes through and destroys the harvest, or the harvest is especially abundant, animals suddenly appear, things happen all the time that can’t be calculated. Hence the desire to return to natural environments. It may start with a potted plant, an experience of growth and the selforganization of nature, and leads to the clear connection between us and nature.

16

Questioning landscape –Understanding and thinking ahead

about nature?

Can you say anything at least to soften this sense of alienation?

Is it possible to live intelligently with nature?

We only share 20 percent of our DNA with trees, yet this 20 percent also produces common goals that result in a symbiotic community. I don’t think that’s mysticism. This alienation you’re talking about has a very high cost, some of which we can afford, because we’ve grown rich by creating this alienation. But it also creates a lasting malaise, which we can partially compensate for by sublimating nature into landscape and making it our own, creating it according to our own criteria. Like a universal landscape that does not reflect any existing part of the land, but is rather a projection of what the ideal land should be. But I believe that the landscape we’ve constructed is a product of this alienation, a very beautiful product of this alienation. And we’ll never be fully free of this alienation. There’s no going back to the trees, there is absolutely no going back in history. The model we’ve successfully used for hundreds of years to dominate and loot the world is now collapsing around us. And we still haven’t figured out how to deal with it.

My point is, I believe that what we understand as landscape comes from this outsider perspective that we’ve assumed. And which, I might add, has been an unprecedented success, without which we would have had no science, no democracies, no human rights. And to some extent these are luxuries. It’s no coincidence that democracies in the true sense of the word are all products of the post-war period and the oil boom. The question is how we can come to a new understanding of the relationship between us and the rest of nature. That, I believe, is a great challenge. We’re just beginning to glimpse the vague outlines of how it could be if we could give up this absurdly inflated sense of ourselves. And that impacts the very foundations of our understanding of ourselves as humans. Then there won’t be landscape any more, just land.

Interview (in Vienna on June 21, 2021) by Henning Klüver

(Translated from the German original)

Questioning landscape –Understanding and thinking ahead

PLANTING

NEW PERSPECTIVES

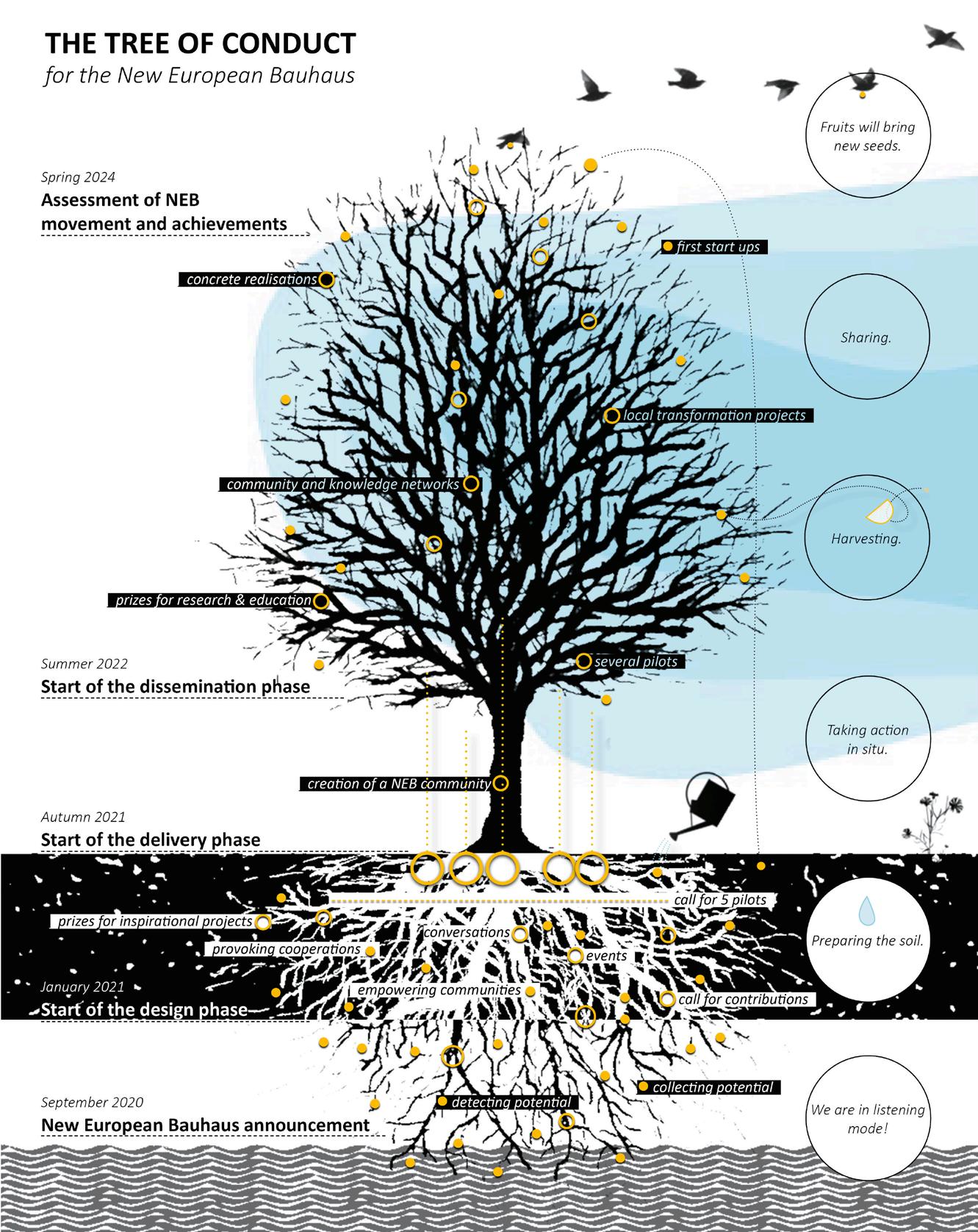

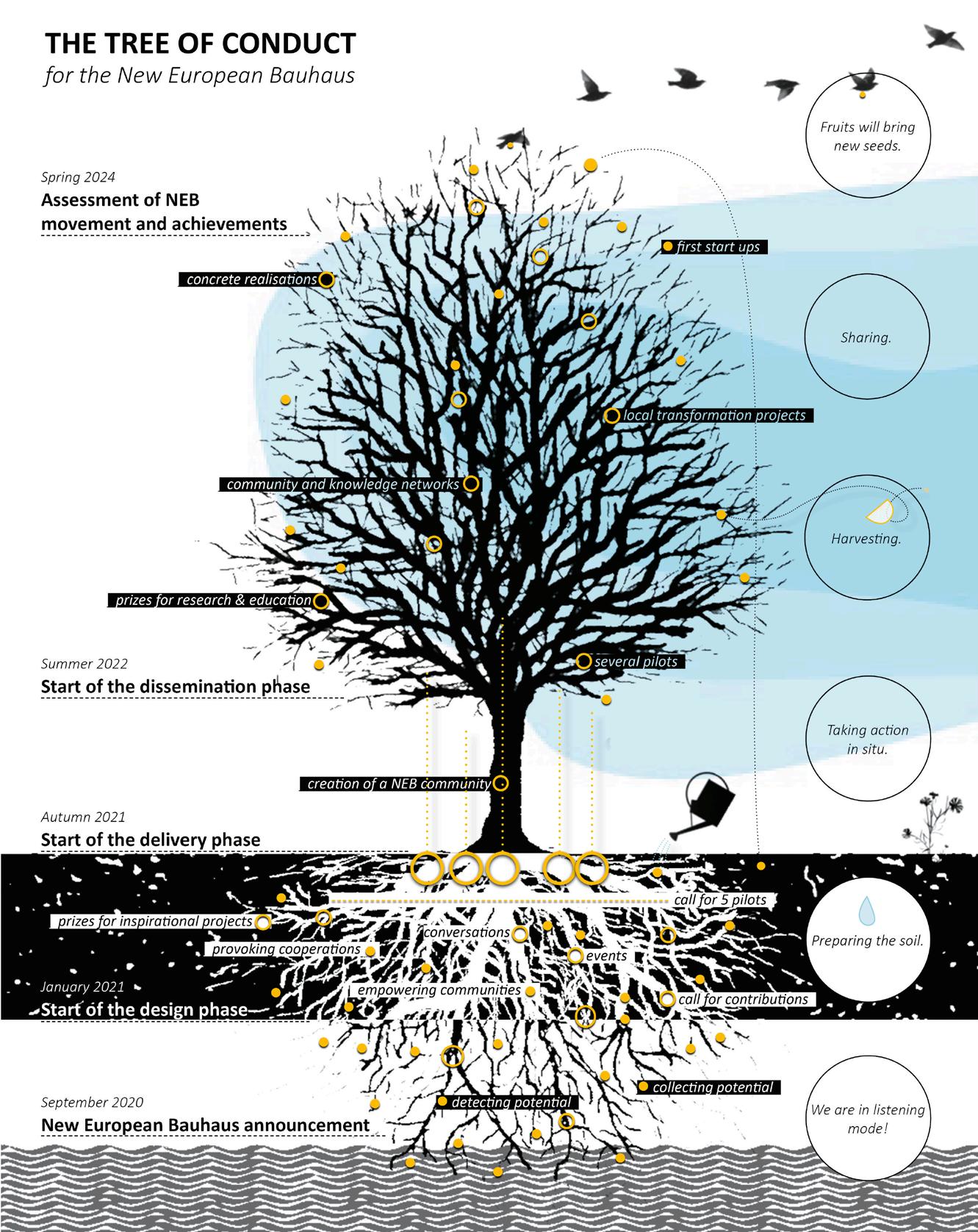

Landscape architecture, the “New European Bauhaus”, the role of public space and the power of bold ambitions – experiences of a young landscape architect

BY STELLAZOË SCHMIDTLER

18

Stella-Zoë Schmidtler © LAND, photo by Ralph Richter

As a young female landscape architect, I’m part of the generation of planners who started their career with a variety of new challenges on their plate. The environmental crisis and demographic changes enriched our field in many ways that go far beyond aesthetics and planting. Any project, whether it’s 100 or 100,000 square meters in size, has the potential to improve the social and environmental condition of the space and its surroundings; especially if we consider how the economic value of space is interminably rising.

I received my undergraduate degree from Hochschule Geisenheim University and my masters from Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona. My deep knowledge of construction and project execution was enriched by eco-centered project topics such as wildfire management, coastal erosion, and strategies to dispel mass tourism using landscape architecture as a guiding instrument. I gained more than 4 years of work experience in the private sector in Germany, Spain and Switzerland, and then decided to apply for an administrative Traineeship at the European Commission, through which I wanted to learn about their strategies of policy-making and funding systems, and how both affect our work as planners. During one year within the Joint Research Centre in Brussels I co-developed processes on Scientific Development (standardisation, open access to JRC research infrastructures), and in October 2020 joined the core team of the “New European Bauhaus” initiative that President Ursula von der Leyen had launched in her State of the European Union Speech one month before.

GLOBAL MOVEMENT

For my expertise as a landscape architect, I had the good fortune to join Xavier Troussard and Alessandro Rancati on the ground floor of shaping the initiative for a more inclusive, sustainable and beautiful way to design our joint future. As the team slowly grew, we worked closely with the President’s advisory team I.D.E.A., and the first few months focused on the design concept for the initiative, which was intended to become a movement just like the original Bauhaus. We held many inspiring interviews with ambitious

organizations and individuals which supported the values of the New European Bauhaus and were eager to start a movement together. The website we designed had already been launched in January 2021 and offered various ways to engage with the initiative: to share ideas of how to make Europe more inclusive, sustainable and beautiful, send in projects that promote inclusiveness, sustainability and aesthetics, or host a conversation on New European Bauhaus topics.

The audience for the initiative thus grew very quickly, and we received even more feedback, ideas and many messages from motivated and capable people who were ready to participate. Besides the open approach to the public – showing the institution in listening mode and assuring an unusual bottom-up approach of engaging with anyone who wanted to engage – the President’s cabinet also required a high-level roundtable of international experts from different sectors as external representatives acting as ambassadors. Part of my work was also dedicated to preparing this roundtable, from evaluating potential candidates, organization and co-hosting of group interviews, and proposing candidates for the cabinet to select.

THE ROLE OF PUBLIC SPACE

The opportunity to propose young people as candidates, including more women and people from disadvantaged countries or regions, was a crucial experience for me. With the candidates who accepted our invitation we set up conversations in groups of three, mixing them in terms of nationality, age, profession, and attitude, to challenge their qualities of flexibility, expertise and communication. Participating in conversations with personalities like Alexandra Mitsutaki, Shigeru Ban, Olafur Eliasson, Gina Gylver, Jan-Christian Vestre or Bjarke Ingels was the least expected but professionally most inspiring part of my experience within the European Commission. With all the challenges we discussed in the context of the New European Bauhaus, I realized how urban or rural public space can and must mediate in so many ways in order to bring people back together in the globalized world.

The insights on how the European single market is working, why we need European regulations and standards, and the people who provide scientific evidence for making political decisions showed me the importance of European institutions. The most impactful thing I realized was that, due to the Union’s complexity, all processes and projects within the European Commission are very slow and require a great deal of sensitivity, but in the end, they do not directly lead to change in the field. There are hundreds of experts, scientists, lawyers etc. who work on shaping the financial and legal framework to constantly improve the lives of people living in Europe.

We planners need to seize the many opportunities and tools they give us and take the ambitious visions for the future to the field.

Concept sketch New European Bauhaus by Stella-Zoë Schmidtler during her work with the Commission's team

To me, landscape architecture is planting new perspectives. Physically or mentally, it is about telling a story, explaining why things are the way they are and helping people to envision a good future. Landscape architecture stands between the man-made and the natural, and its goal must be to assure the most respectful interaction between the two. We create spaces for people while we must assure natural functioning and an effective enhancement of value. We have many opportunities to save the world with landscape architecture; we just need to stay constantly informed, be bold with our ambitions, and spread awareness of our work and its potential.

Stella-Zoë Schmidtler, Master in Landscape Architecture (Polytechnic University of Catalonia), works as a landscape architect at LAND.

20

Questioning landscape –Understanding and thinking ahead

SPACE FOR PEOPLE AN EDUCATIONAL PATH

BY TOMMASO BASSETTI

As our family drove through the Sulcis-Iglesiente region of southwest Sardinia, I looked out the window and felt an odd attraction for the desolated, abandoned mines, wells and tunnels, the ghost towns and beautiful beaches we were passing through.

Once a prosperous area thanks to mineral and coal mining, the Sulcis is now a prime example of Italy’s deprivation, unemployment and brain drain. How could such beautiful, history-rich landscape be left in such state? What makes people want to be in one place and then, suddenly, leave it as it is?

It was the summer of 2014. I had just turned 19 and was myself about to migrate, leaving the comfort of Rome to pursue a new life studying abroad in the Netherlands. At University College Utrecht, through courses in human and urban geography, political science and sociology, along with an extremely multicultural cohort of students, I found the perfect place to explore new ideas.

During a month-long urban planning course which included two weeks of urban exploration in New York City, running around a jungle of concrete, high-rise buildings, rampant homelessness and extreme wealth, I started to reflect more and more on the power dynamics behind landscape. Essentially, who gets to decide on how landscape is shaped and evolves through time? In NYC, I began to get a rough idea of the complexity of urban systems through meetings with different departments in the city government, NGOs, neighborhood initiatives, real estate developers and many others.

My internship at LAND’s Research Lab in Milan came at the perfect time. I had the privilege of working on a project that looked at regenerating the inner city of Genoa through nature-based solutions. LAND’s approach was key for my personal and professional development. One of the key lessons I got from them is that city planning needs a paradigm shift: we need to plan cities and places with, not against nature, and with a detailed eye to the local context in which we live and work.

With these rich experiences, I was ready to continue my journey through a Master’s, learning from English and international planners at the University of Cambridge. Specializing in affordable housing issues, specifically in London, I spent the year researching and interviewing a diverse range of stakeholders. From the 1990s, the sudden shift of responsibility away from local government to increasingly global real estate developers made housing increasingly unaffordable, not only in London but in most major cities. The commodification of housing, which is an essential component of the urban landscape, needs to stop, and housing needs to be seen as a basic human right.

Since 2018 I have worked on sustainable urban development policies and projects, with a focus on developing cities in Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Western Balkans and Central Asia. Working with the United Nations, the World Bank, and the C40 Cities Finance Facility on housing and transport, I always try to bring an integrated, context-based and climate-oriented view to urban infrastructure project development and financing.

In a recent UN Mission to Podgorica, Montenegro, I had an afternoon without meetings and took the time to walk around the city’s neighborhoods, sitting in parks, speaking to local women and men both young and old, trying to immerse myself into the local community. As I move forward with my career and personal development, I will continue observing each and every aspect of the landscape around me, trying to make the best connection I can between people, places and nature.

Tommaso Bassetti, MPhil (University of Cambridge), is a consultant on urban and environmental policy at the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE).

WUNDERKAMMER THREE DECADES OF GREEN

»The landscape knows no boundaries and it is with this awareness that we have cultivated our story since we began in 1990. In recent years, our projects and processes have favoured a sustainable development capable of expanding the conception of environment, recognizing the relationships between people, plants and animals and the dialogue with the elements air, water and land, and putting them first.«

Andreas Kipar

22

landscape –Understanding and thinking ahead

Questioning

The Wunderkammer in via Varese 12 in Milan. A project of LAND – Andreas Kipar, Roberta Filippini with Virginia Sellari. Curated by Luca Molinari, Luca Molinari Studio with Anja Visini. Exhibition and graphic design – Leftloft.

The Wunderkammer in via Varese 12 in Milan. A project of LAND – Andreas Kipar, Roberta Filippini with Virginia Sellari. Curated by Luca Molinari, Luca Molinari Studio with Anja Visini. Exhibition and graphic design – Leftloft.

LANDSCAPE AS MEDIATOR –URBAN AND RURAL SPACE

About the global revival of cities through green and blue infrastructures, the cultivation and care of natural regions and the role of technologies

The High Line of New York, designed by James Corner Field Operations (Project Lead), Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Piet Oudolf. A 1.5-mile long public park built on an abandoned elevated railroad.

© Photography by Iwan Baan

RADICAL MIXED USE CHARLES RENFRO

A New York architect on lessons learned from the pandemic, the future of the city and the role of architects

Changes to the workplace due to COVID have left many of our single-use office buildings abandoned. Why not reimagine them as sites for a new form of zoning and building called Radical Mixed Use? In RMU, office buildings could be adapted to house low-income apartments, community facilities, schools, parks, shopping, culture, healthcare and yes, offices. Such a shift would allow many urban residents priced out of the city to return while enlivening entire districts of the city that are now ghost towns after dark.

Source: Document Journal, January 2021, published alongside One World Trade sketch (see next page)

Making buildings that are more equitable, more approachable, and more accessible is something that's driven our practice for a long time. In the context of this global pandemic, we are trying to make our cities habitable during a time of contagion. That has resulted in a few notable efforts that might be here to stay, with the Open Streets initiative in New York being chief among them. Turning our cities inside out, bringing the interior activities outside, makes our cities more transparent, accessible, vibrant and connected to the environment. By dissolving the walls between inside and outside, we significantly reduce the barrier to entry while simultaneously reducing the chance of disease transmission. This barrier-free thinking should then trickle into many facets of our society — into healthcare, culture and education, to name a few.

We are likely to also see a radical shift in the way our built resources are used. Office buildings are already being targeted for reimagining. Some of them are going to go into foreclosure. Why couldn't the city put in place a plan where foreclosed office buildings could be redeveloped into what I call radical mixed-use? Not just retail on the ground floor, and residential above. Noretail, schools, housing for every income bracket, parks, community facilities, schools, kindergartens. A building could be an entire community, and also include offices. The monocultures of office buildings are city killers. If you think about Midtown Manhattan - Sixth Avenue and the west side of Rockefeller Center in particular – before the pandemic it was already a pretty dead part of town as of 7:00 or 8:00 PM, aside from Broadway attendees. It's because those buildings are just sucking the life out of the city. What if those buildings could be reimagined, rebuilt, rethought, rezoned, to create community? I would like to see a more radical type of mixed zoning emerge from this crisis that would eliminate traditional zoning which perpetuates inequity and racism.

Source: 92Y The Great Thinkers, and Design Disruptors public panel conversations, 2020

If we could re-write zoning codes and regulations to allow radical mixed use, the resulting architecture would need to follow more of a scaffold model, allowing radical mixed-use users to occupy structures, such as the concrete domino structure, that could change over time as needs change and the virus changes, and in turn make segregated cities into integrated cities. This would be a spectacular direction for architecture. In this way, it reflects Cedric Price’s Fun Palace, one of our studio’s favorite projects for inspiration. As you probably know, it was a piece of architecture that could rebuild itself based on the desires of its users and inhabitants, and it was a framework designed by an architect, Cedric Price, although it was never realized. My idea of a future building is one with a radical mixed use

26

Landscape as mediator –Urban and rural space

Charles Renfro © Photography by Geordie Wood

that can remake itself in the future, maybe not without architects, but certainly with a whole group of architects. Maybe a tiny family can hire a 1-person firm to redo their house that will sit within an 80 story framework. So, it is really much more about collectivity than about iconic, monolithic, culturally dead buildings that are in our downtowns now. (…)

If we can re-code and re-engineer office buildings that have been abandoned because of COVID into radical mixed-use buildings, and transform them to allow people who have been pushed out of the places they live and work to come back to cities such as NYC and San Francisco, that could be a really interesting way that architecture could be rethought and remade post COVID.

Source: Interview with Rodrigo Tisi, 2021

Charles Renfro, US architect, is a partner at the New York studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro. The text is based on several contributions by the author during 2020 / 2021.

On the left: One World Trade sketch by Charles Renfro On the top and on the right: The High Line of New York

© Photography by Timothy Schenck and Iwan Baan

On the left: One World Trade sketch by Charles Renfro On the top and on the right: The High Line of New York

© Photography by Timothy Schenck and Iwan Baan

Landscape as mediator –Urban and rural space

ACROSS BORDERS LOOKING BACK HELPS

A conversation with landscape architect and city planner Andrea Gebhard, President of the German Federal Chamber of Architects

28

Country in the city: Massagno, Lugano (Ticino)

© LAND, Photo by Ralph Richter

»VITAL: INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION«

When congratulated on her election as President of the German Federal Chamber of Architects, Andrea Gebhard puts things into perspective. Her predecessor was also a woman, and a landscape architect had already headed the professional organization. Moreover, she says she’s also an urban planner, and from 2007 to 2014 she served as president of the Association of German Landscape Architects (BDLA). At the time, however, she was in fact the first woman to head the professional association since its founding in 1913.

She puts the current trend toward greener cities into a similar perspective. She’s obviously quite happy about this and about the new focus on landscape architecture that comes with it. But Andrea Gebhard explains just as matter-of-factly that landscape architecture has always been a foundation for urban development. “Landscape architecture is a foundation of urban planning and is closely tied to it.”

Before Andrea Gebhard founded the gebhard·konzepte studio in 2006, which became mahl·gebhard·konzepte in 2009, she had worked with the Munich planning unit since 1984, heading the green planning department there from 1993 to 2000. She notes Munich has had an open space design statute since 1996. At the time, the purpose of the statute was “to ensure and promote appropriate greening and design of building sites and children's playgrounds.” And it’s been a real success for the design of open spaces.

But the history goes back much further. She knows that in past centuries Munich was full of gardens, and she mentions the year 1812, when Maximilian I Joseph commissioned garden designer Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell and architect and master builder Carl von Fischer to plan the expansion of Munich. The city is still shaped by this ground-

breaking planning, and the layout of Munich’s English Garden can also be traced back to Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell.

Andrea Gebhard, who also received the Munich Architecture Award this year, is delighted about the increased focus on green cities: “Climate change has brought green issues to the forefront as never before. Awareness of this has increased enormously.”

LANDSCAPE MUST BECOME THE LAW

Awareness is one thing, action is another. What does she see as the obvious consequences? Here she mentions the important landscape architect Walter Rossow, who back in 1965 amazingly demanded that “The landscape must become the law.” She still feels committed to the principle voiced by this pioneer of landscape and environmental planning decades before there was general awareness of climate and urban development issues.

Right now there are various connections between the city and the countryside. Great numbers of people move back and forth between them. Initially, it was mainly younger people who moved from the countryside to the city, but later the exact opposite happened, with an urban exodus that intensified after the outbreak of the pandemic but had been underway for years due to the high cost of living. So generally speaking, Andrea Gebhard considers city and country to be “interrelated spaces. Urban lifestyles shape country areas. Conversely, agricultural uses, including urban farming and urban gardening, will also increasingly find their way into cities in the future.”

It’s no coincidence that people often refer to the appearance of cities as “urban landscapes.” This could literally become the future. But she

30

–Urban and rural space

Landscape as mediator

»GREATER MIXED USE AND SHORT DISTANCES FOR THE CITY OF THE FUTURE.«

also believes it’s important for land also to mean soil. “Roof gardens and green facades are great, but they‘re no substitute for parks. Trees really thrive in parks, and that's where children play.”

For the city of the future, the president of the Federal Chamber of Architects anticipates greater mixed use, short distances as suggested in current discussions on the 15-minute city, dismantling of traffic corridors, pedestrian- and bike-friendly planning and, of course, more and better quality greenery. To make that a reality, it helps to think back, but it’s not enough for the future. Andrea Gebhard emphasizes that “above all, interdisciplinary cooperation across

Andrea Gebhard, President of the German Federal Chamber of Architects

municipal, state and administrative borders” will be necessary. These few words have major ramifications: regions as spaces and new perspectives can make different kinds of planning possible.

Text: Andreas Schiller (Translated from the German original)

Landscape as mediator –Urban and rural space

Attractive and liveable: Düsseldorf on the Rhine ©

DÜSSELDORF LIVE CLOSE FEEL FREE

A conversation with mayor Stephan Keller

In this time of climate crisis and pandemics, a future-oriented urban policy must address issues like affordable housing, the public function of open space, green areas in the inner city, and the importance of water. This is also true in Düsseldorf, where Stephan Keller, who also heads the Rhineland metropolitan region, has been mayor since November 2020. Born in 1970, the politician, lawyer and cycling enthusiast studied law in Bayreuth and Birmingham and did his doctoral work at the University of Bochum. Questions to Stephan Keller:

32

Photo by Ralph Richter

Dr Stephan Keller, Mayor of the State Capital Düsseldorf

Since the pandemic began, much has been written and discussed about the city of the future. How do things look in Düsseldorf?

When you consider the slogan “Live close Feel free” in terms of urban development, does “free” also refer to open space – does open space create urban space?

Düsseldorf is attractive and livable, international and cosmopolitan, with a 'global Rhenish' mentality, but above all it’s distinguished by the special charm and uniqueness of its fifty neighborhoods. I very much like this combination of hominess and cosmopolitan attitude, and I think that it’s been very successful in Düsseldorf. The city’s progress, especially in terms of construction projects, was in no way hindered by the Covid pandemic. First of all, of course, demand for living space has continued unabated. We’re also moving ahead with the redesign of central squares like Heinrich-Heine-Platz and Konrad-Adenauer-Platz across from the main train station. I think the Düsseldorf of the future will be an ideal combination of urbanity and hominess. To me, our slogan “Live close Feel free” expresses this very well, and I’m sure that we’ll be back in the saddle very soon.

Of course we should think of the city in terms of open space. We need to understand and assess its qualities and potential so we can create good development concepts. By the same token, open space is where people who live and work in the city meet and interact. The city is essentially perceived through open space. So adequate, well-designed and properly functioning open space is essential for a livable city.

What are your thoughts on green areas and nature in your city?

What developments are you expecting in upcoming years?

In these times of Covid, the city’s green areas have become even more important for its residents. People have used parks and woods, playgrounds and community gardens, and even the countryside, much more than they did before the pandemic. Requests for community garden plots have significantly increased, and sports in public parks, woodlands and open areas have become more popular than ever. So it’s important both to protect and develop nature. This applies not only to the natural landscapes that still make up nearly half the city, 85 percent of which are subject to natural and landscape protections, but also to green areas in the inner city. Since 2016, Düsseldorf has been a member of the “Municipalities for Biodiversity” alliance, which is committed to preserving biodiversity in both residential areas and the countryside.

The challenges for the future lie in adapting urban green areas to climate change and preserving and developing green areas and open spaces with an eye to climate protection and the needs of a growing city. Düsseldorf has set itself the goal of becoming a climate capital. Comprehensive measures for climate protection and climate adaptation should be interwoven, helping the city become climate neutral by 2035. One building block in the strategy for effective climate adaptation is consistent implementation of the city tree concept, to improve the tree population and increase the number of trees.

The urban development approach known as Raumwerk D, in which LAND is also involved, has been used in Düsseldorf for a long time. What role do you think nature plays in it? And what about water and green areas?

A crucial foundation for Raumwerk D is the Rhine-influenced Green Space 2025 Plan approved by Düsseldorf’s city council in 2015. Water plays a major role in developing the city and its green areas. The mostly undeveloped Rheinaue area is one of the two most important open stretches in Düsseldorf. The Rhine flows 42 kilometers through the city, with diverse natural and green areas. Preserving this diversity and sustaining the Rheinaue in terms of its effect on local climate, flood control, recreation, and protection of nature and the landscape remain key tasks for the future. The city’s namesake – the Düssel tributary – also plays a crucial role in the development of important city parks. The Ostpark, Zoopark, Hofgarten, Ständehaus and Spee’sche Graben are located along the Düssel, which feeds their ponds and lakes. Prominent city streetscapes like those of Prinz-Georg-Straße or Karolingerstraße are influenced by the Düssel. In online discussions, “bringing the Düssel to life” is one of the six most hotly discussed and popular approaches in the four spatial concepts of Raumwerk D. So the issue will continue to be an important building block in the process of creating a city-wide strategic development concept.

»DÜSSELDORF

HAS SET ITSELF THE GOAL OF

BECOMING

A CLIMATE CAPITAL.«

Düsseldorf and Moscow have been sister cities for more than 25 years. Do the cities exchange ideas on green issues during their meetings?

Interview from September 2021, questions by Andreas Schiller (Translated from the German original)

Düsseldorf and Moscow exchange ideas on various social issues and challenges, including green issues. For example, a round table discussion on “Environmental Monitoring Programs and Technologies, Greening the City” brought together representatives of the two city administrations, with additional onsite visits during the 2017 “Moscow Days in Düsseldorf.” Representatives of Düsseldorf’s city administration regularly participate in panel discussions at the Moscow Urban Forum, an international symposium that deals with urbanization issues and urban planning, development and environmental problems.

34

–Urban and rural space

Landscape as mediator

STRATEGIES OF CULTURAL CHANGE

The green infrastructure of the city of Saskatoon (Canada)

BY TYSON MCSHANE

Saskatoon, the city that I live and work in, sits at the heart of one of the most transformed landscapes in the world. Once a mix of boreal forest and mixed moist grassland, the southern half of the province has been transformed due to intensive agriculture, ranching, and diverse forms of resource extraction. This change has proved to be a major economic driver for both Saskatchewan and Canada, while also resulting in the province sometimes being called the breadbasket of Canada due to it being the largest wheat producer in Canada.

Despite the great benefits from this change, it hasn’t come without its costs. Grasslands, such as the prairie rough fescue, have become increasingly rare and at risk from fragmentation, invasive species, and climate change. An increased knowledge and appreciation of how transformed our landscape is and how threatened some of the remaining native species are, has resulted in significant work to assess how and where our development happens here in Saskatoon. In my role as the manager of Long Range Planning, I’ve had a front row seat to a culture shift that is slowly but surely underway. With a greater appreciation and access to more knowledge of existing natural systems, and the ecological services they provide, the debate on how to not just conserve natural areas but find ways to appropriately integrate them into our city and region is underway.

HOW TO CONSERVE NATURAL ASSETS AND AREAS WITHIN OUR BUILT ENVIRONMENT

A key milestone in this debate has been the development of Saskatoon’s Green Infrastructure Strategy. This ambitious document charts a course for how natural assets and areas can be conserved within our built environment. It provides a vision of an interconnected network of green spaces within our city and provides a new lens to use when reviewing development proposals.

[ continued on next page ]

Tyson McShane, City Planner, manages the Long Range Planning Section of the Canadian city of Saskatoon. His current role has seen him overseeing the development of large-scale Sector Plans for the City of Saskatoon, supervising the development of a green infrastructure strategy, and leading a redesign and update of Saskatoon’s Official Community Plan.

Protected grasslands: Saskatoon (Saskatchewan Province, Canada)

With this vision in place, now comes the hard work to ensure that the value of natural areas and assets is appropriately considered through the development process. A significant current debate regards an area known as the Northeast Swale – a glacial channel scar left over from when the glaciers retreated from the Canadian prairies. This natural area contains some of the last remaining prairie rough fescue in the province as well as valuable habitat for rare, endangered or culturally significant species ranging from the northern leopard frog to the sharp-tailed grouse.

Though this has been an area of interest for some time, it took until development was on its doorstep for it to be studied in detail and its value and boundaries debated. Currently one neighborhood is under construction adjacent to the swale, with another at the initial design stage. The telling detail of this process is that over the last fifteen years, our understanding of the Swale, and therefore our understanding of how to conserve and appropriately interface with adjacent developments has changed. Initial studies showed wetlands to be the most significant natural assets, but with increased study, came increased knowledge, shifting the focus for conservation efforts towards grasslands. This resulted in changes to where roads should pass through

and what overall boundaries should be. This speaks both to the complexity of natural systems, but also the fact that they are ever changing, resulting in a need to continually monitor and consider how they can fit into an urban environment.

THE COMPLEXITY OF EVERCHANGING NATURAL SYSTEMS REQUIRE CONTINUOUS MONITORING

The exciting thing for Saskatoon is that due to how our understanding of the northeast swale changed, our processes for assessing natural areas during the planning of new developments are evolving to provide more accurate information at an earlier stage in the process. This helps to ensure developers, regulators and the community as a whole have better access to information and more opportunity for debate ahead of decisions being made. These processes will continue to evolve and we will continue to be challenged to ensure we have the right information and the right understanding of the impact of development on natural areas. Fortunately, we are in the best position yet to be able to incorporate our evolving understanding of our natural assets into how we guide development. The Green Infrastructure Strategy and the vision it provides sets Saskatoon on a new path for how development and natural assets can complement one another.

36

–Urban and rural space

Landscape as mediator

FLIGHT OF THE BIRDS OF CAGLIARI EN ROUTE TO THE FUTURE

As dusk falls in Cagliari in the spring and early summer, you can feel a change in the air. Small flocks of greater flamingos fly back and forth over the city, from the Molentargius wetlands, where thousands of them nest, to the Santa Gilla lagoon, which offers the birds rich nourishment. With a population of about 150,000, this regional capital on the southern coast of Sardinia has ancient Phoenician-Roman roots. For almost two decades, changing municipal governments have tried to promote the green-blue potential of this panoramic seaside city stretching out across seven hills. From the two bordering lagoons, various parks and gardens create natural counterpoints in the island city, although the city’s rapid growth after the war did not always include good building quality.

As early as the Green Plan (Piano del Verde) developed with LAND in 1996, strategic principles

had been developed to double public green areas. At present (2021-22), the focus is on developing and updating this master plan and transforming the historic administrative city to a green metropolis. The new strategic plan currently being developed is meant to prepare Cagliari to make a new bid for the European Green Capital Award after this summer’s failed attempt in the competition for the title of “European Green Capital.”

“We continue to persevere,” says Paolo Truzzu. The mayor wants to examine the reasons for the rejection set out in the commission’s report and to use them as a catalyst for improvement and another application in the future. Cagliari as the green city on the sea? The goal may still be distant – but there’s a clear map pointing the way.

Text: Henning Klüver (Translated from the German original)

The dream of a green capital © Photo by Ilaria Congia

INSTRUMENTS METHODS SOLUTIONS

BY ANDREA BALESTRINI

Landscape as mediator –Urban and rural space

How the LAND Research Lab is helping to make cities and rural areas more livable, climate-positive and resource-efficient

38

»THE DECADE UP TO 2030 WILL BE DECISIVE IN TURNING OUR LIVES AROUND.«

Everyone’s talking about climate protection and resilience, about energy efficiency and saving water. The issue of sustainability is front and center for cities, public entities and companies. The decade up to 2030 will be decisive for turning around current lifestyles and production processes and accelerating plans to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

National and international institutions as well as citizens require clear information and concrete action to tackle and achieve this goal.

APPLIED RESEARCH

Can you make sustainability quantifiable? That is our task. Due to its multidisciplinary approach, sensitivity to local context, and responsive attitude to societal challenges, landscape design is emerging as a leading discipline in urban and territorial transformation processes. So here at the LAND Research Lab (LRL), we’re developing tools to do this. This is not purely scientific research, but rather applied research and practice supported by theory.

LRL’s goal is to identify collaborative practices and data-driven methods to make cities and rural areas more livable, climate resilient, and resource efficient: through our Sustainability Compass, for example (see title photo of the article). This is a new tool that makes the environmental and socio-economic impacts of landscape projects visible and measurable within the framework of the ecological transition driven by the EU Green Deal. The compass evaluates the impact of projects and regional strategies on the targets of UN Agenda 2030 and relates them to the values of the New European Bauhaus: beauty, sustainability, inclusion.

LRL also offers consulting services in developing and evaluating nature-based solutions, and sustainability strategies. It cooperates within the framework of EU-financed projects and their net-

works. One of these is “UNaLab” (Urban Nature Labs), with 28 international partners. In Genoa, we’re supporting a pilot project to transform a former barrack in a densely populated and socially diverse neighborhood into a public park. The project deploys various nature-based solutions to address multiple local challenges (water management, heat stress, and lack of accessible open space). The monitoring plan and governance guidelines developed for the project allow such solutions to be transferred to other situations. Another EU project, called "T-Factor," makes transformative change and time the central factors of new approaches to urban renewal. With 25 partners and six pilot projects (such as MIND, the innovation district rising on the former 2015 World Expo hold in Milan), we’re developing an international platform to support urban development by facilitating knowledge exchange and fostering practices regarding temporary uses and inclusive participation in large regeneration masterplans. As part of LAND, LRL also promotes continued learning, innovation and exchange of practices within the company to support its projects.

BEST PRACTICES

The significance of these projects is easy to see. Europe has been severely impacted by the effects of climate change. Economic losses in the EU due to flooding will rise from EUR 4.9 billion annually to EUR 23.5 billion by 2050 (in a worst-case scenario, costs could even increase fivefold). But according to the Nature Climate Change Report, flood losses could be reduced by 30 percent by 2050 if around EUR 1.8 billion is invested yearly in flood protection measures. Across Europe, certain best practices show the real impact of mitigation and adaptation projects in reducing economic losses. These include our regional green infrastructure projects and new productive landscapes on coal mines and wastelands in the Ruhr region, climate-adaptive

40

as mediator –Urban and rural space

Landscape

restoration of valley floors and riverfronts in Ticino, and floodplains and rain parks in Italy.

NATUREBASED SOLUTIONS

To quantify and explain environmental impacts in landscape projects, we have added a new dimension to the BIM (Building Information Modelling) interactive cloud model: LIM landscape information modelling®. LIM helps our clients and partners in designing, implementing and monitoring nature-based solutions for greener and healthier cities, using a data-driven approach. “Nature is eternal life, generation and motion,” said Goethe. It’s a dynamic element that grows and accomplishes more and more over time. So LIM is creating scenarios that measure impact on air quality, water management, soil condition, and plant growth across the life-span of vegetation to improve the well-being of people living in cities. For example, vegetation can be used in green roofs, which regulate the internal temperature of houses, absorb rainfall, and promotebiodiversity. This multi-benefit approach is how nature-based solutions have now found their way into official EU climate strategies.

Many cities are taking steps to hasten the process toward a more robust regenerative economy by promoting sustainable mobility, participatory planning, and the use of digital infrastructure. Yet we should not forget that urban green areas must play a fundamental role in preventing the unhealthy partitioning of open space and decline in quality of life. The mission stated in the regenerative urban development strategy, “Reconnecting people with nature,” is the basis of LAND's research on adaptive design of the urban landscape, where streets are considered to be a shared ecosystem, water-sensitive design is promoted, urban reforestation becomes essential, slow mobility enhances quality of life, and last but not least, digital technologies make it possible to extend, connect, and talk about landscapes.

This is why we can talk about a sustainability decade. In this regard, LAND is committed to identifying new opportunities for the resilient development of communities, based on a pact between people and Nature that can respond to societal changes and benefit from the potential of technology.

»NATURE IS ETERNAL LIFE, GENERATION AND MOTION.«

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Title photo of the article: Andrea Balestrini, Head of LAND Research LAB, and the Sustainability Compass © LAND – a new tool that makes the environmental and socio-economic impacts of landscape projects visible and measurable.

The author studied landscape architecture in Stuttgart, among other places. He has contributed to research projects under the German Ministry for Science and Research, conducted one year of baseline studies in Lima (Peru), and now directs the LAND Research Lab in Milan.

STORIES FROM CITY AND COUNTRY FOUR HIGHLIGHTS FROM PERSONAL EXPERIENCES

Milan is a city that people either love or hate. My first experience here wasn’t easy – Milan’s gray and rainy fall and winter days aren’t especially inviting. But then I started to meet people, go places and create memories – and my whole perception changed. At some point, I began to see the city not just as the big picture, but rather as a puzzle with many pieces. This helped me create my own mental map of places – where I could meet friends and drink an aperitif, a cozy little corner with a beautiful Milanese-style facade, a piazza where I took a great photo. My whole perception changed once again when I started riding my bike every day. I got an even clearer picture of streets and places that aren’t terribly familiar to people who drive or use public transportation – a lot of typically Italian places in a city that doesn’t seem very Italian.

In a city like Montreal, where I’ve spent a lot of time working on our firm’s projects, the pandemic forced many social meeting places to curtail their activities drastically. People responded to the need to socialize by turning to existing public parks and open spaces. What struck me the most were the reactions of individual citizens. During the pandemic, individual initiatives on behalf of nature multiplied, from planting small public flower beds to creating private fields of flowers and private gardens. Local government initiatives have brought nature closer to the city. Beekeeping and city chicken coops have been approved and regulated. In some parks, lawns are maintained by flocks of sheep. While there’s a clear trend toward sustainable development at the administrative level, often there’s still no overall vision. What makes the difference is the full participation – street by street – of people working to build a new urban nature, in support of next door biodiversity.

42

as mediator –Urban and rural space

Landscape

MARTINA ATANASOVSKA THE CITY AS PUZZLE

VALERIA PAGLIARO NEXT DOOR DIVERSITY

»BIG CITIES WILL HAVE TO VENTURE MUCH FURTHER INTO NATURE.«

KORNELIA KEIL STRENGTHENING

KORNELIA KEIL STRENGTHENING

THE COMMUNITY

I think it’s an absolute privilege to live and work in a vacation area. Being able to protect my mental wellbeing through nature during the stresses of everyday life is essential to me, and it’s easy to do when you work in a home office in a rural area like Kiefersfelden. Most people have gardens and private open space where they spend much of their free time. The pandemic in particular shifted the focus to the private sphere. So we need to create more attractive opportunities in public areas in order to strengthen the community and lure people out of their homes again. Town centers should be made stronger, creating places where residents can get together. Rural areas are currently under a lot of pressure due to increased local tourism. I’d like to see development go in the direction of soft tourism, so the locals can keep their safe havens.

LISA PEREGO AMONG FOXES AND BADGERS

LISA PEREGO AMONG FOXES AND BADGERS

I‘ve always lived in the country, in a little village in the Brianza region north of Milan. The hilly landscape is agricultural, with large wooded areas, valleys, rivers and streams. Having grown up surrounded by squirrels, rabbits, foxes, badgers and birds in a place with great biodiversity, I find it hard to imagine giving it all up and moving to a crowded and chaotic city. Admittedly, the city can be quite attractive, particularly because of its social and cultural events and job opportunities. But the country also offers relationships and activities that enhance our community life. The landscape and nature in the place where I live influenced my professional life as well – I was delighted to choose landscape architecture as my vocation.

The authors work for LAND from a variety of locations.

Landscape as mediator

FROM PASS TO PASS

Traveling Switzerland’s wintry crossings

BY FEDERICO SCOPINICH

44

–Urban

and rural space

When I was asked to write something about life outside the big cities, I (who grew up in Milan and have lived in Lugano for several years) thought about last winter, when I had few options for traveling south. So I turned to the old nearby mountain passes to the north, which are partially closed to traffic in the winter and only accessible on touring skis and climbing skins. That’s how this little story started, as a hiking diary in which I describe the perhaps unconscious need to overcome geographical barriers while contemplating questions about the future of alpine landscapes.

AIROLO AND ST. GOTTHARD

This hike begins in Airolo at the foot of the Gotthard Massif, where the Swiss army was once stationed in order to fend off an expected attack by fascist troops from nearby San Giacomo Pass. Now it’s traffic that threatens Airolo. In 2018 the municipality was able to launch an important landscape restoration project for the valley, including plans to cover a one-kilometer stretch of the A2 highway nearby. It will still be years before people can forget the endless traffic jams of the Alta Leventina and their negative effect on quality of life. In their place, a new landscape is slowly emerging, with agricultural areas, woodlands and recreational facilities, inspired by the sustainable development of tourism and the environment.

From Airolo, two tracks lead to the Gotthard Pass. With its 24 hairpin turns, the historic Tremola route, built between 1827 and 1832, is perhaps the most spectacular stretch of the Via delle Genti (the “Peoples’ Road”). Unlike the Brenner and Simplon passes, the deep gorges in the Leventina and Valle della Reuss often prevented goods from being transported over the Gotthard Pass. Yet it was a direct route for anyone who wanted to reach central Switzerland from the south. Today the Gotthard Pass has reached a technological pinnacle, the culmination of centuries of creating infrastructure, connections and relationships across the Alps. The city is far away, but it leaves its mark through various infrastructure scattered across the pass. With its five wind turbines, the wind farm that opened in 2020 generates 15% of Switzerland’s wind energy. Although the amount of infrastructure on the valley floor is finally starting to decline, and people are increasingly moving towards a future of sustainable development of the environment and tourism, the pass remains a

© LAND, photo by Ralph Richter

Landscape as mediator

symbolic place that has been marked by outside forces. I wonder whether acceptance of such facilities in uninhabited mountain regions like the Gotthard Pass has become less questionable.

ANDERMATT, OBERALP AND FURKA

On the north side, the Gotthard Pass trail leads

to Hospental, a picturesque village in the Urserental. The largest town in the valley is Andermatt, a formerly reclusive alpine village that over the past ten years has undergone a major transformation, with the construction of hotel and residential complexes and a connection to the nearby Sedrun ski area. The reason for this sudden development of tourism is Andermatt’s strategically attractive location. The village is on the Furka – Oberalp railway line, which connects the cantons of Valais and Graubünden. And the A2 highway is only seven kilometers away. The Urserental’s destiny clearly lies in tourism. The community’s future seems predestined, and it would not be the first alpine region to embrace an increasingly urban atmosphere. Do we miss the city when we go to the mountains?

NUFENEN AND VAL BEDRETTO

The Gotthard Massif is the source of four major European rivers. In addition to the Rhine and the Reuss, the Rhône also arises from the foot of the Furka Pass with a glacier of the same name (now shrunk due to global warming), and flows through the Valais into Lake Geneva and on to the Bouches-du-Rhône, the Rhône delta in southern France. On the eastern side of the Nufenen Pass, the Ticino has its source in Val Bedretto, flowing through the Leventina across Lake Maggiore and finally emptying into the Po. Rivers are important links in this region. During the summer you can explore this great European watershed along the

85-kilometer “Vier-Quellen-Weg” (Four Springs Trail). It seems a paradox, but these natural elements link the different valleys of the region better than transportation infrastructure does. With the exception of the Nufenen Pass for a few brief months in summer, there is no direct connection between Ticino and Valais (and thus Lake Geneva). Perhaps because the transalpine crossing over the Gotthard permits no detours?

An almost straight stretch runs from Andermatt to Realp, a village in the extreme southwest of the Urserental at the mouth of the railway tunnel that leads to Valais. Here the hairpin curves climb up to the Furka Pass. Barely visible on the signposts is the name of the road that was the scene of the famous car chase in the film “Goldfinger,” with James Bond driving a souped-up Aston Martin DB5. Near Tiefenbach, where the path to the pass winds up the steep slopes of the Bielenhorn, I have an encounter with a viper just coming out of hibernation. It’s slow and confused, trying to avoid patches of snow, and finally it vanishes among the steep meadows that slope down to the Reuss.

LUKMANIER

In the High Middle Ages, the Lukmanier Pass, which connects the Blenio Valley in Ticino with the Medel Valley in Graubünden, was one of the most popular European routes between the Po Valley and the Rhine Valley, and was also a road for religious travelers, with pilgrimage churches and monasteries. Nowadays, after keeping the pass open in winter for a time (2002-2010) to encourage tourism, the trail is one of the first to

open in the spring, and is used to get to various points of departure for ski tours in the region. Along the upper stretches of the trail are extensive forests with slow-growing, long-lived stone

46

–Urban and rural space

Gotthard Pass

Furka Pass

pines (Pinus cembra) nestled along the bends and riparian meadows of the Brenno River, which regularly floods, regenerating its rich ecosystems. Large parts of the area are pristine, while at lower elevations the landscape of the Blenio Valley is marked by agriculture.

»DO WE MISS THE CITY WHEN WE GO TO THE MOUNTAINS?«

The Swiss Confederation maintains its landscapes through “landscape quality contributions.” This financing maintains the cultural value of the landscape, including the preservation of woodlands, creation and care of chestnut forests, and promotion of alpine agriculture. This rural landscape is the result of goals shared by business leaders, politicians and citizens. While the balance of interests is less challenging at lower elevations, in the mountains, in places like the Greina plateau, there is a clash of interests between efforts to preserve the pristine nature and uniqueness of the Greina area as an “alpine tundra” for hiking and nature tourism and the interests of shepherds and hunters. Leo Tuor talks about these problems in his interesting article, “Eine andere Greina” (“Another Greina”). How does the alpine identity develop, when nature becomes a museum?

VAL D’AVERS

A long drive along the San Bernardino road takes you to Juf, Europe’s highest permanently inhabited community, enthroned above the treeline at the far end of Avers valley, at an elevation of 2126 meters. This peaceful place with its mostly undeveloped ski facilities attracts few visitors in the winter, but the feeling of seclusion vanishes during the summer. An extensive network of hiking trails takes visitors to nearby valleys like the Bergell and Val Surses, or up to the Lunghin Pass, the triple watershed for the Black Sea, the North Sea, and the Mediterranean, where the Inn, the Julia and the Mera (known as Maira in the Bargell dialect) have their source. The Septimer Pass is also nearby, on the divide between the major European basins of the Rhine in the north and the Po in the south. The pass played a major role during Roman times, but became

less important after the Gotthard was opened. Today Juf has 21 residents, while the municipality of Avers has 171. Although its population has steeply declined over history (in the seventeenth century almost 500 people lived in Avers), the number of residents has now become fairly stable. Of course, for such an isolated community to survive, both service facilities and local job opportunities are of vital importance. But what would become of Juf if the village’s remarkable qualities began to attract vacationers and more of its dwellings were used as second homes?

Federico Scopinich, Urban & Landscape Planner, studied at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna and at the Valencia Polytechnic University, and heads LAND Suisse. Photos by Federico Scopinich (Translated from the Italian original)

Val Bedretto

Landscape as mediator –Urban and rural space

DESIGNING WITH TIME A CONVERSATION ABOUT THE FUTURE

LAND’s leadership team met for a talk in Lugano on September 23, 2021. The occasion? As the driving forces of the LAND international consulting and planning company, they wanted to spend time together and talk about Today and Tomorrow – as people who live in and design public space. This is a brief overview of the topics, challenges and responsibilities they discussed.

Time is an essential component of the work of landscape architects. Landscape has no beginning and no end. Landscape is always evolving and being shaped over time. At any moment in time, it provides a snapshot of the society that lives in it and shapes it. This is precisely why we need visions for our landscape. Common visions that make participatory processes

possible and pursue a sustainable strategy. It takes imagination. The power of persuasion.

One of the biggest challenges we now face is maintaining the quality of public spaces and their infrastructure and services during this time of transformation. In the 1980s, Ian McHarg talked about this in his book Design with Nature Today we know that the dimensions of time and cultivation are also important.

Convincing others to adapt to Nature’s timeframes and be patient is a real challenge. The best answer to impatience is usually to take a walk –out there where LAND launched the green transformation 30 years ago. In Milan, in EmiliaRomagna, in Essen. Even a symbol of environ-

48

Shadow play at the LAC Lugano Arte e Cultura - the directors of LAND

mental destruction like the Ruhr region with its steel mills and coal mines could be restored. Over the last 15 years. How was this achieved? With foresight. With a roadmap of multi-year actions. With a patiently committed community of purpose.

Landscape consultants are not scientists or social engagers, but transferring knowledge and engaging stakeholders are other fundamental components of the work. There must be an understanding (data-based) of how important Nature or Nature-based solutions are for urban and rural open spaces. That they serve not only aesthetics, but above all our future and future generations. There must be first-hand knowledge of how green transitions can succeed. People must be given the opportunity to become part of it.

There’s no longer any doubt that landscape can’t be dedicated to the simple desire for beauty anymore, but must instead pursue ethics and well-being. Our responsibility is to develop tangible and measurable solutions to counteract climate change. And when even Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, calls us to action because now is the time,