Signals

June July August 2010 Number 91

@ footy fever

Try

around

daily to match the

that are playing. By the harbour’s edge in front of the Australian National Maritime Museum, Darling Harbour. 11 June -12 July, 2010 Bookings ph: 02

5144 eat@yotsdarlingharbour.com.au www.yotsdarlingharbour.com.au Open 10 am - 4 pm daily

Yots Café Bar is a great harbourside location to join in all the fun and activities of the Soccer World Cup. Bring your family to join in the Fan Fest activities & drop into Yots Café Bar for breakfast, lunch or drinks.

our ‘flavours of the world’ specials - food & beverages from

the globe prepared

teams

9211

June

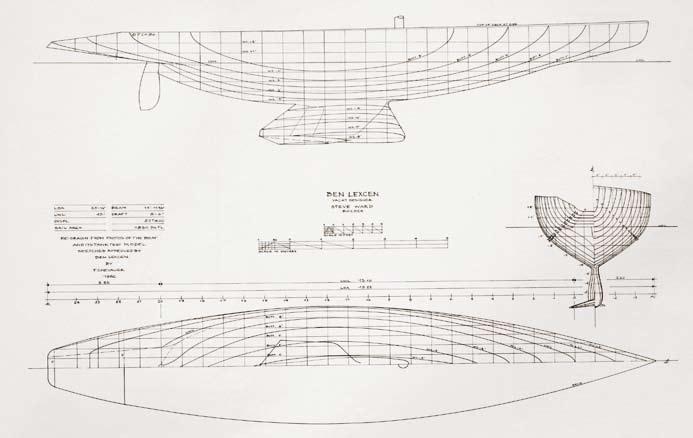

cover: The 1:3 scale tank test model of the famous Ben Lexcen-designed 12-Metre yacht Australia II is an important artefact in the museum’s collection, representing the historic Australian victory that snatched the 1983 America’s Cup and broke a 132-year US stranglehold on what was then yachting’s most prestigious trophy. Now there’s debate about who designed its revolutionary winged keel – the full story is on page 13. Gift of America’s Cup Defence 1987 Limited. Photographer A Frolows/ANMM.

2 Admiral Pâris and his extra-européen boats

One of France’s most remarkable naval officers compiled this rare encyclopaedia of non-European vessels in 1843

13 Turbulence around the winged keel

Questions have surfaced again about who really designed Australia II’s winged keel

21 Quest for the South Magnetic Pole

This exhibition is the first to examine the quixotic quest for this ever-shifting geographical phenomenon

25 Members events

Talks, tours, cruises, seminars, children’s events … winter calendar for Members

30 What's on

Cert no SGS-COC-006189

From the director 14

Winter exhibitions, events for visitors young and old, programs for schools

34 Governor Macquarie lights up South Head

An exhibition marking the 200th anniversary of the visionary governor’s arrival in the colony

39 Lady Hopetoun, first of the fleet

The seventh annual Phil Renouf memorial lecture recalls the beginnings of Sydney Heritage Fleet

42 Salty songs and rollicking verse

Renowned folk impresario Warren Fahey writes about songs from our maritime past

47 Readings

Sydney Harbour – a history; Sailing into the past

42 Tales from the Welcome Wall

Far from Mother Russia – via China and Hong Kong

44 Collection

A seat at history’s table – Dunbar memento

46 Currents

Mythic writing; Endeavour at Kurnell 240 years on

48 Bearings

Signals

Contents

to August 2010 Number 91

2 34 21 42

Admiral Pâris and his extra-européen boats

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 2

A treasure of the museum’s collection is a rare encyclopaedia of traditional, non-European vessels, published in France in 1843. This pioneering work of maritime ethnology was compiled during three world voyages by one of France’s most remarkable naval officers. Curator Dr Stephen Gapps has worked with museum staff to make the entire publication accessible online, and brings us the fascinating story.

above: Portrait of the one-armed Admiral FrançoisEdmond Pâris (1806–1893). Photographer L Rouille, late 19th century. Reproduced courtesy of the Musée national de la Marine/S Dondain left: Plate 47 Gay-you bateau de pêche de la baie de touranne au plus près du vent, et se laissant dériver pour trainer des filets (Gay-you fishing boat in Touranne Bay [indochina] close to the wind, drifting to drag the nets). Pâris delineator, Mozin lithographer. ANMM collection

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 3

It may seem unlikely that a 19th-century French naval officer who led the introduction of steam engines and ironclad warships into the French navy would be best-known for recording, with a delicate painterly hand, rustic scenes of traditional ‘native’ boating. Yet FrançoisEdmond Pâris, a decorated veteran of the Crimean War who rose to the rank of admiral, was no ordinary naval officer. He has to be one of the most fascinating characters in French maritime history. His career in many ways bridges the pre-modern and industrial periods. He was absorbed in the grand enterprise of collecting, describing and classifying curiosities of the newly explored, non-European world, sailing three times between 1826 and 1840 with renowned French world-voyagers. Pâris was also at the forefront of two great 19th-century transformations. One was the introduction of steamship technology. The other turned ‘cabinet-of-curiosity’ collections into the great didactic museums of Europe, as Pâris ended his career as head of the French maritime museum.

During his Pacific voyages, the energetic Pâris documented virtually every type of watercraft he encountered, in places as diverse as Senegal, the Seychelles, India, the Straits of Malacca, Malaya, Singapore, Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, China, Australia, Chile and Brazil. He recorded canoes from Greenland, Arab dhows, Chinese junks, Malay prahus and Pacific outrigger craft. Pâris’s fascination with non-European maritime traditions produced an extraordinary publication that’s one of the treasures of the collection at the Australian National Maritime Museum. It’s an astonishing encyclopaedia of non-European vessels, published by the

Pâris’s ethnographic work takes a seafarer’s delight in the inventive solutions that had developed to meet the universal challenges of seafaring

Pâris repeatedly depicts the craft that he records both in picturesque views and in precise technical drawings, as in this Arabian ‘beden’ at anchor, under sail and oar and in plan and section.

right: Plate 7 Beden safar de mascate, au mouillage et à la voile (Beden safar of Muscat, at anchor and under sail).

Pâris delineator, Sabatier lithographer.

below: Plate 5 Garookuh de mascate et beden safar (Garukh of Muscat and beden safar).

Pâris delineator, Adam & Lemaître engravers

French government in 1843, titled in full Essai sur la construction navale des peuples extra-européens ou collection des navires et pirogues construits par les habitants de l'asie, de la malaisie, de grand ocean et de l'amerique (Essay on non-European naval architecture, or a collection of vessels and canoes built by the inhabitants of Asia, the East Indies, Pacific Ocean and America). It includes 132 lithographic plates of boat plans and nautical scenes, and notes on the vessels’ construction, design, handling and use. Without doubt the Essai ranks as one of the greatest of all works on naval architecture.

Better-known early 19th-century illustrated French voyage accounts of Australia, Asia and the Pacific, by the likes of Baudin, Freycinet and Louis de Sainson, are rich sources of natural history and ethnography. However, Pâris’s maritime ethnography of indigenous watercraft was unique. His documentation of these vessels included meticulous, scientific plans of their structure and rigging. Yet he also created accomplished, vibrant scenes of these craft in use. Pâris’s skilful sketches, paintings and watercolours of busy waterfronts and working sailing craft often compile the different activities of fishing vessels, lighters, or transports into a single, richly informative image. We see how these vessels worked, and his careful observations provide us with information about the people who worked them and the environments in which they operated.

In 1994, the Australian National Maritime Museum acquired a copy of Pâris’s rare, limited edition with the assistance of the Louis Vuitton Fund, established by the luxury goods retailer to help the museum collect items relating to French exploration in our region.

The sumptuous folio remains exactly as published: in two volumes, 13 parts, comprising 132 loose plates and 156 loose pages of text, all presented in a blue morocco box. Since numbers of them were subsequently bound by their owners, the museum’s specimen is particularly valuable. Only a dozen copies are thought to remain in existence.

Although a selection of the images was temporarily displayed by this museum, most of them have never been publicly viewed. Now this important illustrated encyclopaedia has been included with this museum’s growing online collection content.

François-Edmond Pâris was born in 1806, the son of French government administrator Pierre-Théodore Pâris. He entered the French Naval Academy at Angoulême in 1822 and studied painting with the naval artist Pierre-Julien Gilbert (1783–1860). Gilbert’s official role was to document French naval history, and he painted many dramatic naval battles. Pâris’s other art teacher was Pierre Ozanne (1737–1813), a naval draftsman and engineer who was known for his fine and accurate drawings of ships and naval battles. Pâris’s talent for both rigorously accurate plans and lively, scenic watercolours can be traced to these early influences.

Graduating from the naval academy as a hydrographer in 1824, Pâris’s flair for drawing and painting soon secured him a place on a voyage of scientific exploration. In 1826 he joined L’Astrolabe for a world voyage under Captain Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville, who preferred trained navy personnel to ‘troublesome’ civilian scientists and artists. Pâris was one of three junior officers or élèves assigned to the voyage. He was to have an excellent role-model

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 4

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 5

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 6

Plate 21 Engraving from the section ‘Ceylan et Côte de Coromandel’ (Ceylon and Coromandel Coast [india]: Doni à balancier (Outrigger dhoni) in section, elevation and plan. Pâris delineator, Adam & Lemaître engravers

in L’Astrolabe’s official artist Louis de Sainson, who would produce the remarkable Atlas historique of this 1826–29 voyage.

Dumont d’Urville’s expedition was France’s last and greatest scientific voyage of discovery, in the grand tradition of Bougainville, d’Entrecasteaux, Baudin and Freycinet. Its objectives included the delivery of young olive and fig trees from Toulon’s Botanic Gardens to John Macarthur in New South Wales; ‘to look for a place suitable for the deportation of criminals’; to look for anchorages for warships; and to continue the search for evidence of the long-lost expedition of Comte de Lapérouse, which vanished shortly after meeting the First Fleet in Botany Bay in 1788.

L’Astrolabe reached Australia via the Cape of Good Hope, and Pâris was employed surveying King George Sound in Western Australia – not yet formally colonised by Britain – and later Jervis Bay south of Sydney. Here the young officer drew an Aboriginal bark canoe, or as he titled it Pirogue en écorce de la baie Jervis Plate number 112 of Pâris’s Essai from the region ‘Nouvelle Hollande, Nouvelle Zelande’ shows several canoes from New Zealand and the only drawing of an Australian watercraft in the series.

In Port Jackson, Dumont d’Urville discovered that his extensive surveys had aroused suspicion about French intentions. Indeed Governor Darling had already been alerted from Britain of French interest in King George Sound and had dispatched two brigs, Amity and Fly, to establish a British settlement there.

Ordered to ‘examine the vast territory in the north-east of New Zealand’, Dumont d’Urville readied the ship’s guns and muskets because of the ‘fearsome reputation’ of the Maori. After causing more consternation over France’s colonial ambitions, d’Urville visited several Pacific islands and erected a monument to Lapérouse on the island of Vanikoro. While heading home via Mauritius and

Cape Town, the young Pâris received word of his promotion from élève to enseigne de vaisseau (ensign).

The hydrographic results of the expedition, its vast collection of botanical and zoological specimens and its artistic output were highly regarded. A grand record of the journey, Voyage de la corvette l’Astrolabe, was published in 13 volumes of text and four atlases of plates – the Atlas historique – between 1830 and 1835. The Atlas was a significant collection of art works, most by de Sainson but several of them based on paintings and sketches by unofficial voyage artists including FrançoisEdmond Pâris.

The plates were produced by lithography – ‘drawing on stone’ – a complex and highly skilled printmaking technique that allowed a richer texture than engraving, and the use of colour. Artists painted or drew on polished limestone blocks with oily crayons or washes, and used chemicals and acid that had an affinity for oil to etch the image into the stone. They applied inks that adhered to the oily image areas and were repelled by water sponged on the non-image surfaces. A sheet of paper pressed onto the stone came away with a perfect printed image. Used by commercial printers for scenes and views, lithography had not previously appeared in French government publications, suggesting the importance they placed on Dumont d’Urville’s Atlas historique

The next French voyage to the South Pacific was to have quite a different focus. In 1829 Cyrille-Pierre-Théodore Laplace was given command of an expedition to secure French colonial interests. Laplace was to re-establish waning French influence in Indochina, and obtain information about the ports and trading regulations of other places in Asia and the Pacific. Laplace chose his own officers and among them was the recentlypromoted Lieutenant Pâris, bringing his experience on Dumont d’Urville’s famous

Pâris delights in the aesthetic appeal of seacraft everywhere –so often the cleverest artefacts of human ingenuity

expedition and his growing reputation as a hydrographer and artist.

La Favorite sailed from Toulon in December 1829, rounded the Cape of Good Hope in a storm and encountered several hurricanes before making the island of Mauritius. Laplace took the ship to India to refit. Near Madras, La Favorite grounded on a mud bank and was assisted by local Indian fishing vessels. Pâris was to later note that these masula, despite their frameless construction of mangowood planks sewn together with coconut coir, were well-suited to the surf precisely because of their very un-European flexibility.

La Favorite continued to Singapore and then visited a series of far-eastern ports, including Manila, Macao and Canton, where Laplace secured ‘most favoured nation’ status with the Chinese. While in Da Nang (Vietnam), Laplace noted that Pâris’s survey chart of Tourane Bay was ‘as handsome a piece of work as it was useful’. Again, though, Pâris was not just making charts. The many studies of Indochinese watercraft he later published show that he spent a great deal of time painting, sketching and measuring all sorts of ‘péniche’, ‘gaydiang’, ‘bateau de pêche’, ‘gay-you’ and ‘caboteur’.

La Favorite continued to the Dutch East Indies, then to Australia. The crew had suffered much illness in Asia and two men were buried on Bruny Island in Tasmania; another three died in hospital in Hobart in July 1832. In Sydney the Frenchmen were a popular addition to the colony’s social calendar. Pâris would have been involved in what Laplace described as the daily round of ‘excursions, banquets and balls’ that took up all the officers’ time while in Sydney – so exhausting, in fact, that he had to set sail in order to gain some rest!

The warm welcome cooled when colonial authorities learned that the French were making extensive surveys of the New Zealand coastline in an

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 7

On his return to France, Pâris’s increasing portfolio of work was recognised and he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur

apparent attempt to claim it for France. The threat of this French corvette off the New Zealand coast led several Maori chiefs, prompted by some colonials, to write to King William IV for his protection. This ultimately hastened the British colonisation of New Zealand.

While Pâris made several detailed drawings of Maori canoes, Laplace was not at all taken by other aspects of Maori culture. He wrote of being ‘sickened’ by a feast that included the ritual eating of human flesh. Laplace left ‘these abominable savages’ and La Favorite headed east, arriving in the Chilean port of Valpariso in November 1832. Continuing south around Cape Horn, they were home in Toulon in April 1833.

Despite some trading setbacks in China, Laplace’s voyage was generally regarded as a success and the French government authorised the publication of his account, Voyage autour du monde … sur la corvette de l’État La Favorite, in four volumes, from 1833. Twenty-four of the 72 plates of various ports and towns included in the first volume were by François-Edmond Pâris, who had been active in sketching and painting during the expedition.

Pâris had also begun to compile his notes, sketches and watercolours of extraeuropéen watercraft. A manuscript that would eventually form the basis of his Essai sur la construction navale des peuples extra-européens, now held in Paris at the Musée national de la Marine, shows many of the views and naval architectural drawings that were later engraved or turned into lithographs.

On his return to France, Pâris’s increasing portfolio of work was recognised and he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur. Considering his expertise in native craft, it seems in some respects curious that Pâris then sought permission to go to England to learn English and familiarise himself with the operations of the new steamships. His skills in plan drawing and his

excellence as a technician no doubt aided his application. His time in England was productive, as he was later involved in installing the first steam engines on French naval vessels.

The work on indigenous watercraft was not yet complete, however, and Pâris was to embark on a third major voyage and circumnavigate the globe one more time. In 1837 Pâris was attached as executive officer to the frigate Artémise, once again under Laplace. The age of European scientific exploration was coming to an end and the voyage was primarily a political one: Laplace was to ensure fair treatment for French missionaries and traders in Tahiti and Honolulu.

The voyage of Artémise became an arduous, disease-ridden struggle through the Indian Ocean and South-East Asia that would prove catastrophic for Pâris.

In June 1838, while inspecting a steam engine in a foundry in the French enclave Pondicherry in southern India, his sleeve became caught in some machinery and his arm was mangled. It was later amputated, but in the best naval traditions this didn’t stop the energetic Pâris from continuing his work and career, or his infatuation with steam engines.

Artémise visited Hobart and Sydney – the third time for the well-travelled Lieutenant Pâris. After striking a reef in Tahiti, sailing the Californian coast and suffering an outbreak of cholera on board, Artémise returned to France in April 1841.

Pâris’s three expeditions had provided him with such a comprehensive body of work on non-European watercraft that he could now claim to have a definitive study. The King of France agreed. Pâris’s drawings and notes were to be published by royal decree and very shortly after his return in 1841, his Essai sur la construction navale des peuples extra-européens entered production. It was a mammoth task, and little expense was spared. Some of France’s most notable printers, engravers

ingenious solutions to seafaring’s challenges: right: Plate 117 Pirogues de Lakeba, au plus près y vent arrière (Canoes of Lakeba in a following wind). Pâris delineator, Mozin lithographer.

below: Plate 130 Pirogues de valparaise et balse des intermedios (Canoes of Valpariso [Chile] and raft in middle). The three-masted ship in the background is most likely the corvette La Favorite on which Pâris made his second world voyage. Pâris delineator, Mozin lithographer, Lemercier printer.

and lithographers were employed, and several artists were required to help copy Pâris’s art onto stone.

The publication was produced as a folio series, rather than bound as a book. This meant not only that subscribers could receive the Essai in instalments as it was produced in 13 parts over the next two years, but that errors could be amended and changes incorporated as the production continued.

The firm Lemercier, Benard et Cie was one of the major participants. Joseph Lemercier, who was once described as the ‘soul of lithography’, had been awarded medals for his work including Dumont d’Urville’s Voyage de la corvette l'Astrolabe. He was associated with many prominent French artists, and explored different techniques for colour lithographic printing. In 1837, with the printer Benard, he formed Lemercier, Benard et Cie & Co, which was to print the majority of the 132 lithographs and engravings in Pâris’s Essai, although a handful of the last plates in the folio were credited solely to Lemercier.

The Essai was produced by the publishing house of Arthus-Bertrand, bookseller and specialist editor of new voyage chronicles. Claude Arthus-Bertrand was an ex-army officer who established a bookshop and publishing house in Paris in 1803.

After producing the eight-volume atlas of Louis Isidore Duperrey and Jules Dumont d’Urville’s Pacific voyage of 1822–25, Arthus-Bertrand became an official publishing house for the French Naval Ministry.

The majority of the Essai’s lithographs were printed by Bouchard-Huzard, established by veterinarian Jean-Baptiste Huzard and his wife Marie-Rosalie to produce veterinary and agricultural books. It was thus well-positioned to produce large, detailed images. Madame Huzard was one of the few women involved in printing in 19th-century Paris, continuing after her husband’s death in 1838. She was

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 8

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 9

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 10

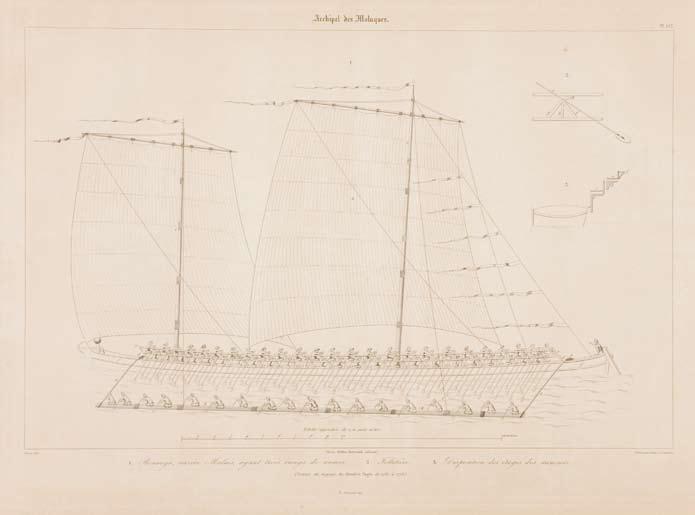

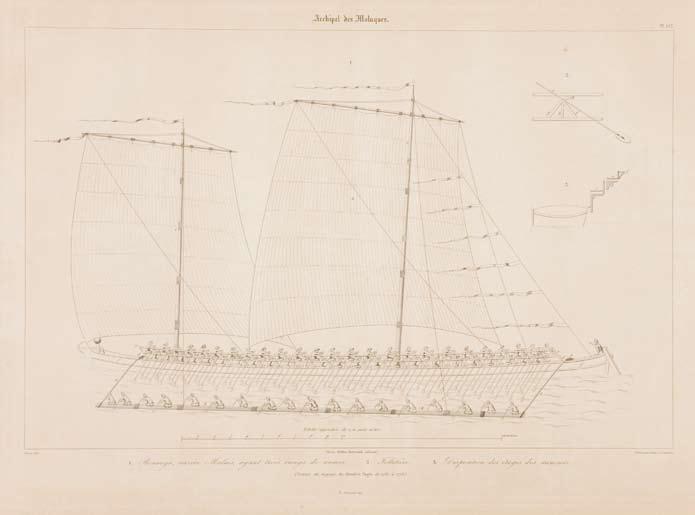

From the humble Jervis Bay bark canoe and decorated New Zealand canoes to an extraordinary Moluccan war galley.

left: Plate 123 Pirogue en écorce de la Baie Jervis, pirogue de l’Anse de L’Astrolabe dans l’île de Tavai Pounamou, pirogue de la Baie Houa-Houa dans i’île Tka-na-Mawi (Bark canoe in Jervis Bay, canoe of Astrolabe Cove in Tavai Pounamou island, canoe of Houa-Houa Bay on the island Tka-na-Mawi). Pâris delineator, Adam & Lemaître engravers.

below: Plate 103, section ‘Archipel des Moluques' (Molucca Archipelago), Bouanga, navire Malais, ayant trois rangs de rames (Bouanga, Malay vessel, having three banks of oars). Pâris delineator, Adam & Lemaître engravers

a significant presence in the production Pâris’s Essai

Most of the engravings required to reproduce its lines plans and drawings were produced by Adam et Lemaître. Augustin François Lemaître was a prominent engraver and lithographer in 19th-century Paris. Victor Adam was a respected lithographer who had worked on several major publications of Pacific voyages including Dumont d’Urville’s Atlas historique

Léon Jean-Baptiste Sabatier was the lithographer of many of the plates in Pâris’s Essai and is noted as artist on the only two plates in the folio where Pâris himself is not the credited artist. Sabatier was a prolific artist, engraver and lithographer between the 1830s and 1880s. He produced many scenes of Asia and the Pacific and was involved in the production of several volumes and folios of scenes from French maritime expeditions in the mid-19th century, notably Dumont d’Urville’s Atlas historique

Arguably the most prominent artist involved with Pâris’s work was Charles Mozin. Regarded as a significant artist in the development of what has been called pre-impressionism, his early work in the 1820s focused on views of fishing boats and coastal villages and ports. A remarkable draughtsman as well as a painter, he paid attention to small details such as a ship’s rigging. All of this made him an excellent choice as the main lithographer for Pâris’s Essai. Between 1841 and 1843 sections of the Essai were posted regularly to subscribers. They appear to have been produced monthly. This system allowed some flexibility in the engraving and printing process. The individual plates did not arrive sequentially, but were grouped with the corresponding text pages. The yellow cover sheets for each series –

from the first series or Livraison Première to the 13th and final Treizième et Dernière Livraison – wrapped the plates and text pages and held an updated index to each series.

When complete, the Essai text and accompanying atlas of plates were arranged in geographical regions such as ‘Arabie’, ‘Côte de Malabar’, ‘Bengale’, ‘Ceylan’, ‘Afrique’ ‘Chine’, etc. The text provided information on the type of vessels, what they were used for and how they were constructed. Each entry has at least one accompanying image of a vessel that shows how it was sailed or how it was employed, for example in fishing or transportation. Some are dramatic scenes under full sail in high seas. Others show in precise detail intricate carvings on the prows of Maori canoes or Chinese junks. Some are obviously intended to show how a particular type of sail was rigged. Many include everyday details such as laundry hanging on a line to dry. The major study is often accompanied by an engraving of construction drawings of the vessels shown in section, elevation and plan, and sometimes the complete lines taken off the hull. Some show scaled human figures. The detailed architectural drawings were later to form the basis of reconstructions of many of these vessels as models.

Despite the loss of an arm, Pâris remained active in the French Navy, transferring to its new steamship section in 1842, commanding the steam ships Infernal and Archimède, before receiving the rank of captain in 1846. Other commands between 1847 and 1854 included the royal yacht Comte d’Eu in 1847. In this time of rapid innovation and change in naval warfare, as steam-driven, ironclad ships evolved, Pâris collaborated with his father-in-law Admiral Bonnefoux on a huge Maritime Dictionary of Sail and Steam, in both French and English.

His arm was amputated, but in the best naval traditions this didn’t stop the energetic Pâris from continuing his work and career

During the Crimean War (1853–56) Pâris headed a naval division, and in 1856 took command of the single-screw steamer Audacieuse. In 1857 he visited England to study the construction of Brunel’s great ‘Leviathan’, the steamship Great Eastern In 1858 he was promoted to Rear Admiral and from 1860 to 1861 led the second division of the French fleet, with his flag on Algésiras. Made a member of the French Academy of Sciences in 1863 in recognition of his contributions to geography, he continued to write treatises on naval architecture. In 1864, Pâris was promoted to Vice-Admiral. He served as director of the Dépôt des cartes et plans de la marine (Bureau of naval charts and plans) and was vice-president of the Dépôt des phares et balises (Bureau of lighthouses and beacons).

He retired from the navy in 1871 –whereupon the ethnographer of nonEuropean maritime cultures came full circle. He became curator at the Musée naval du Louvre and was put in charge of conserving the paintings and drawings he had made in his early career. The naval museum at the Louvre – forerunner of today’s Musée national de la Marine – held a large collection of French ship models and naval paintings. To this Admiral Pâris added his own signature: he commissioned the construction of 250 models of vessels from different locations of the French Empire, based on his plans and drawings. While this gave physical form to the images from his Essai, it also neatly reinforced the extent of French dominions around the globe. The Australian National Maritime Museum has in its collection a copy of the French maritime museum’s catalogue for 1909 that includes the models that Pâris commissioned, all listed as ‘bâtiments éxotique’ (exotic constructions).

Admiral François-Edmond Pâris died in Paris, the city of his birth, in 1893,

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 11

aged 87. His incredible career had commenced in the burst of postNapoleonic ambition for a new French colonial empire, and ended in the cataloguing of these materials in a public, instructional museum. In between, Pâris took the opportunity offered by three world voyages to become the first European maritime ethnographer. He brought to this the same enquiring and technical mind that drove his later involvement with the new technologies of steam and iron.

The vast majority of the craft Pâris recorded have disappeared from use, making his plans and sketches even more significant today. Pâris’s images of Hawaiian craft have been used as the basis for reconstructions of vessels to retrace the journeys of ancient Polynesian voyagers. They have helped researchers to reconstruct the kind of prahus sailed by Macassans from Sulawesi to the trepang or bêche-de-mer fishing grounds of northern Australia. Just a few of the craft Pâris drew survive today. The kattu maram of the southern Indian coasts, fishing rafts of logs bound together by cords and rigged with a lateen sail, are still built and used today in the manner recorded by Pâris.

Pâris’s ethnographic work with its classification of indigenous artefacts exemplifies the spirit of scientific enquiry and the world view of the Enlightenment that propelled the great European voyages of the 18th and early-19th centuries. Yet unlike some images and accounts that emphasised the superiority of the European, Pâris’s work also shows empathy with indigenous cultures. There is a tension – typical of European perceptions of non-European cultures –between the scientific need to document and the impulse to capture the strangeness of exotic cultures. There is also a selection process at work that neatly ties in with French imperial aspirations, with so much of his focus on studies in French Indochina.

Ultimately, though, Pâris’s ethnographic work takes a seafarer’s delight in the inventive solutions that non-European peoples had developed to meet the universal challenges of seafaring. At the same time he demonstrates how these watercraft were ingenious adaptations to quite particular maritime conditions and environments. And he delights in the aesthetic appeal of seacraft everywhere – so often the cleverest artefacts of human ingenuity.

Plate 35 Grands patiles de Calcutta (Large ‘patiles’ of Calcutta). Pâris delineator, Sabatier lithographer, Lemercier, Benard et Co printer

Plate 62 in the section ‘Chine’ (China), Bateaux caboteurs de l’une des provinces du nord (Cargo boat of one of the northern provinces) showing views of a junk rigged with additional topsail and a light-air stuns’l or ringtail. Pâris delineator, Mozin lithographer

Plate 49 Grande jonque de querre (Large war junk). Pâris delineator, Adam & Lemaître engravers

Plate 69 Bilalo, bateau de passage de Manille à Cavite (Bilalo, a passenger boat plying between Manilla and Cavite). Pâris delineator, Mozin lithographer

The Musée national de la marine currently has an exhibition of Pâris’s ethnographic ship model collection, viewable at: www.museemarine.fr/site/fr/expo-tous-bateaux-du-monde clockwise from top left:

You can see Pâris’s masterpiece on our website at 203.35.183.199/eMuseum/code/ emuseum.asp by entering the words ‘essai sur la construction’ in the search box.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 12

*Valid until the end of September 2010. Exclusive to Signals members only. Subject to availability and conditions apply. Based on twin share accommodation. RH931 THE SPECIAL ESCAPE HOLIDAY IS BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND. At Novotel Rockford Darling Harbour you can relax and unwind in one of our Standard Rooms and enjoy FREE full buffet breakfast. We are at the heart of vibrant Darling Harbour and conveniently located near... well... everything. Reservations 1800 606 761 sydney@rockfordhotels.com.au Proud supporter of the Australian National Maritime Museum $179* per room inc breakfast from Designed for natural living www.rockfordhotels.com.au Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 13

Turbulence around the winged keel

Questions have surfaced again about who really designed the famous winged keel of the America’s Cupwinning 12-Metre yacht

Australia II David Payne, curator of ANMM’s Australian Register of Historic Vessels, looks at artefacts in the museum collection to sift through the claims and counterclaims – and delves into the Cup’s tricky history.

It was a standout theatrical moment during the celebrations when Australia won the America’s Cup on 26 September 1983, and broke a 132-year US stranglehold on what was then yachting’s most prestigious contest. Live to world TV, Australia II was hoisted from the water to reveal at last its highly secret winged keel, the unconventional appendage that had devastated the American defenders – psychologically as much as by any boat speed advantage it delivered.

Those images from Newport in Rhode Island, USA, were replayed in October 2009, as controversial claims were aired that the extraordinary keel was not the invention of Australia II’s designer Ben Lexcen. This self-taught genius of yacht design was revered by our nation for the 1983 America’s Cup victory, along with Australia II skipper John Bertrand and the syndicate leader, flamboyant

businessman Alan Bond. Lexcen died of a heart attack in 1988, aged just 52. Not long afterwards Bond was disgraced and gaoled for corporate fraud. Now the media were reporting claims by Dutch naval architect Dr Peter van Oossanen that it was he, not Lexcen, who played the principal role in the keel’s development.

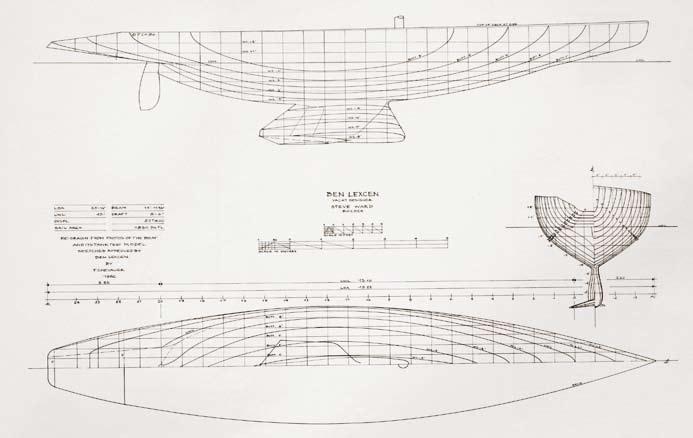

In 1981 van Oossanen had been a key staff member at the Netherlands facility where the Australia II design was tank tested using a 1/3 scale model. That model, number 5854b with keel Va, was gifted to the Australian National Maritime Museum by the Australia II syndicate, along with a series of plans, in the late 1980s. It is currently in storage.

The full-size Australia II was displayed here, on loan, for nearly 10 years from the time this museum first opened. It was then transferred to the Western Australian Maritime Museum in the state where the aluminium-hulled 12-Metre

yacht was built, and where the challenging yacht club and syndicate leader resided.

Last October, when the dispute over who really designed Australia II had journalists clamouring for comment and footage for the day’s news, it was still daybreak in Western Australia. Attention was directed here instead, where our historic 18-foot skiff Taipan – designed and built by Ben Lexcen in 1959 – was on display. As the late designer’s supporters sprang to defend his reputation, the revolutionary skiff Taipan was a trump card. It featured an early precursor of the winglets on Australia II’s famous winged keel, trialled by Lexcen nearly a quarter of a century earlier.

By mid-morning the first TV crews had set up to film and conduct interviews. This continued until early evening when Nine News ran a live cross between the studio and the museum. Standing in front

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 14

The Australia II 1:3 scale tank test model in the museum's collection is an iconic artefact representing the historic Austalian victory in the 1983 America's Cup. Stern and bow views. Gift of America's Cup Defence 1987 Limited. Photographer A Frolows/ANMM.

The bodyplan (the fore and aft sectional view of the hull) was taken from the model in 1986 (see credit page 19).

of a floodlit Taipan, their reporter dismissed the claims that someone else had designed the winged keel in a short, rehearsed exchange with the newsreader.

For the museum, this was a chance to demonstrate another dimension. More than just a place to visit, it was a national resource of significant historical material and was ready at short notice to provide a quality perspective on questions of public interest. It proved again the value of the huge Taipan restoration project we had undertaken in 2008 (reported in Signals Nos 80, 82 and 83). The skiff could now be interpreted correctly, and it made a stunning visual statement for national TV.

The story resurfaced in March 2010 on Seven’s Sunday News program and another media stop was accommodated, at short notice. The mass media, of course, is not known for its ability to convey nuanced information and complex

historical contexts – in this case the background to the America’s Cup and the challenges for it – which were missing from their coverage of the keel-design controversy. The museum, by contrast, is a centre for research, and much of relevance to this question can be found in our collection and archives.

Intriguingly, the formula for a successful America’s Cup challenge was predicted with uncanny accuracy in 1903 by the eminent Australian naval architect Walter Reeks, little-remembered today but profiled on the website of our Australian Register of Historic Vessels. A newspaper report about a meeting he had that year in the USA with Nathanial Herreshoff, then the dominant designer of American defenders of the cup, says: ‘It is the opinion of Mr Reeks … that the cup will never be taken from America so long as the challengers are built on conventional lines, and while such

men as Nathanial Herreshoff still live to design and build American yachts.’ He was right on both points. The eventual winning challenger Australia II was totally unconventional for a 12-Metre yacht, the class that contested the cup from 1956 to 1987. The baton of American design dominance, handed from the great Herreshoff to Starling Burgess and then to Olin Stephens, was gone too; the 1983 defender Liberty was designed by a Dutch-born US citizen, Johan Valentjin.

Earlier Australian challenges for the America’s Cup had pointed the way: things went better when the thinking was unconventional. In 1962 Gretel’s unusual cross-linked genoa sheet winches caused the Americans to abandon the exhausting upwind tacking duels that they used to dominate … and then they watched in disbelief as the flat-sterned Gretel surfed past their defender Weatherly to win a race.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 15

The NYYC began to regret their generosity, alarmed at the threat of a design breakthrough as the rampaging Australia II easily beat off the other challengers

right: Australia II tacks ahead of US defender Liberty during Australia’s successful challenge for the 1983 America’s Cup. Photographer Sally Samins, ANMM collection centre: The museum’s 18-foot skiff Taipan, a revolutionary early Lexcen design. The replica rudder, held by America’s Cup-winning skipper John Bertrand, shows early Lexcen experiments with endplates and other hydrodynamic features. He’s with former Taipan skipper Carl Ryves. Photographer A Frolows/ANMM

far right: Australia II’s winged keel and Dennis Conner, the defending US skipper who it helped to defeat in 1983. Conner, who won back the America’s Cup in 1986, visited the museum in 1992 when Australia II was on display here. Photographer J Carter/ANMM

Gretel II came back in 1970 with proportions that probed new boundaries in the 12-Metre rule, and it featured a number of engineering novelties. Many observers thought it was the faster boat, winning two races but losing one of them on protest. That year’s defender Intrepid, previously an Olin Stephens masterpiece, had been largely redesigned by the lesser-known Britton Chance, and was considered slower as a result of the changes.

The wheels of the America’s Cup juggernaut were beginning to wobble, as Ben Lexcen and Alan Bond understood. Their third challenge, Australia in 1980, carried a radical bendy mast copied from the British 12-Metre Lionheart. Australia was competitive and won a race, giving the team confidence to challenge again knowing that if they could get a major design edge they would at last have an advantage. Previously, advantages had almost always rested with the defender.

The America’s Cup was named after the New York Yacht Club’s schooner America, which sailed to England in 1851 and won the ornate ‘hundred guineas cup’ put up by the Royal Yacht Squadron. Thereafter the contest was governed by a Deed of Gift that set a template for the race’s conduct, in terms largely favouring the defending club. Nonetheless the Deed allowed for many details to be agreed by ‘mutual consent’ between challenging and defending clubs. Over the years the NYYC gradually gave ground, consenting to arrangements or details that assisted the challenger.

After World War II the archaic requirement for the challenger to sail to Rhode Island from its home port was

dropped. Although the Deed specified that the yacht was to be ‘constructed in the country to which the challenging club belongs’, the 1962 Gretel syndicate was allowed to use some American sailcloth and sails, and was granted the use of an American test tank to develop the design. Gretel proved too competitive, and the Americans denied the sailcloth request for the next two Australian challenges.

Later in the 1960s, joint challenges were accepted. By 1983 there were seven challengers, with tough racing to determine which club would be the final challenger. This eroded a previous advantage enjoyed by the Americans, who traditionally chose their defender after hard-fought trials between several yachts. As well, the NYYC now permitted materials and fittings to be sourced from suppliers world-wide. The rules that restricted team membership to nationals of the challenging country were eased, so that a recent change of citizenship would qualify someone to sail for that country.

Bond’s team took advantage of these concessions, to source the very best. They secured an advanced mast extrusion from US sparmaker Tim Stearns and then designed the taper and fittings themselves. They sourced superior instruments from the US firm Ockam. Top New Zealand sail designer Tom Schnakenberg became an Australian citizen to join them. He persevered with new Kevlar cloths when the Americans had given up on the tricky material, recutting and fine tuning until in the end Australia II had superior sails.

The design team was also given permission to use the Netherlands Ship Model Basin test tank in Wageninen

to test models at a large 1:3 scale, because there was no such facility in Australia. This is what has caused the continuing controversy over the actual design of the yacht.

As 1983 progressed the NYYC began to regret their generosity, alarmed at the threat of a design breakthrough as the rampaging Australia II easily beat off the other challengers. The club tried to disqualify Australia II on the basis of the Dutch contribution to its design. In response, Dr Peter van Oossanen denied any design input, saying the Dutch technicians had only carried out tests as directed.

Twenty-six years later, van Oossanen – now an Australian citizen – made the claim that he had been untruthful in 1983. He now says that he and associate Joop Sloof actually played a major role in proposing, designing and testing the keel configurations, and that Ben Lexcen had little input into the process. Their motive for coming forward, they said, was to gain recognition for their input, which they felt had been ignored by Australian accounts of the campaign over the years since 1983. And they wanted to claim most of the credit for the final hull design, too.

A detailed account of the Dutch version of events was gradually made public including the final 1983 report from the Netherlands Ship Model Basin, notes on meetings, comments on telexes – even their records of when Lexcen was at the tank, questioning the amount of time he spent there. Some of it appeared to support a higher level of Dutch involvement, but the tank test report simply described the process and outcome, and did not attribute a designer.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 16

The claim by the Dutch duo set off a furious response from surviving Australia II syndicate members and Ben Lexcen’s supporters, angered that their late colleague was unable to respond. Nor could campaign manager Warren Jones, who had died in 2002. The defenders produced their own records and recollections of the events at the time. John Longley, project manager and crewmember of Australia II, responded with evidence of Lexcen’s design input that appeared in documents archived at the Western Australian Maritime Museum.

In one telex to Warren Jones, dated 22 May 1981, an animated Ben complains about Dutch food – ‘sick of bread and cheese’ – then talks about ‘Keel III’ being a big advance’, christening it Darth Vader and signing off as Ben Skywalker. Ben was clearly there and carrying on as only he could.

His supporters also argued that Lexcen had been an innovative designer for decades, highlighting yachts like Mercedes III, Volante, the International Contender class and the legendary Apollo – the yacht that bonded Bond to sailing. They didn’t hide Lexcen’s failures – he was a risk-taker, always trying something new. But they certainly questioned van Oossanen’s record: two of his later America’s Cup boats, one Australian and the other Swiss, had been eliminated in 1992 and 2000. Both had radical but unsuccessful keel innovations.

Here at the museum Taipan presented Lexcen’s side of the story. It showed that he was a lateral thinker from his earliest designs. On Taipan he had experimented with the hydrodynamics of centreboards

and rudders, using endplates and devices called fences that limited water-flow disturbance and anticipated the winged keel. The radical concept of Taipan’s hull and rig frustrated the 18-foot skiff opposition when it won easily, and upset the traditionalists. But it showed a man capable of pulling apart a rule in ways not contemplated by others – just as he would do with the 12-Metre rule for Australia II Lexcen worked with endplates again on his next 18-foot skiff Venom a year after Taipan, and they showed up on the keel and rudder of his 1967 International 5.5-Metre design Kings Cross. His first 12 Metre was Southern Cross for the 1974 America’s Cup challenge. That year two Australian America’s Cup designers, Alan Payne and Warwick Hood, wrote a now-forgotten article in Australia’s leading yacht magazine Modern Boating One innovation they suggested was an endplate to the 12-Metre keel, arguing that the short keel span of this ageing class needed all the help it could get to improve its effectiveness.

The article drew attention to various ways in which the waterline length could be manipulated within the 12-Metre rule, and how this could ease the peculiar problems associated with these yachts’ proportions and their massive ballast ratios – problems that were compounded when the new, light-aluminium construction was adopted. The article showed how a hull with a shorter waterline length and less ballast could still have enough stability to support its greater sail area.

Australia II’s upside-down, winged keel was the means to this end. It increased stability due to its lower centre of gravity,

allowing Australia II to have a shorter waterline and greater sail area. As is so often the case, similar things had been done before. British yacht designer Uffa Fox, a favoured inspiration to Ben Lexcen and a man with a similar larrikin streak, had been putting upside-down keel profiles on some of his designs since the 1940s, and Ben’s sketchbooks in our collection show similar ideas beginning to surface as far back as 1958.

A key point emerging from these examples is that yacht designers, like artists or writers or musicians, influence each other all the time, drawing on and developing ideas that are already circulating in their highly complex disciplines.

By the 1983 America’s Cup, designs were no longer the product of one person as had been the case when the Deed of Gift was drafted. For decades they had been the result of a team effort, overseen by a chief designer who took the ultimate responsibility for the design when signing it off. That was Ben Lexcen; he had his team, and so did the Americans. Even if a Dutch technician had contributed to the design, he was just a part of the team under Lexcen’s direction. Olin Stephens had used Italian Mario Tarabocchia as draughtsman for the lines of their challengers. Lexcen had teamed up with Liberty’s Dutch-born designer Johan Valentjin in 1977 to produce Australia, and Valentjin had also worked for Stephens in the past. The design web had long been an international tangle. Rule bending was virtually an America’s Cup institution, and whether it was cheating was often a matter of perspective. The Americans had

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 17

above: Lines of Australia II, reproduced from America’s Cup Yacht Designs 1851–1986, author/ publishers François Chevalier et Jacques Taglang 1987. Lines redrawn by F Chevalier 1986.

allegedly sailed a ‘13 metre’ instead of a 12 Metre to win a previous contest, when Courageous apparently slipped through the measurer’s tape. In 1983 a multiple-rating certificate for US defender Liberty was a real irritation. The yacht had been measured in three different displacement and sail-area configurations that could be changed at short notice to suit the wind conditions. Some claimed that this crossed the boundaries of ‘fair sailing ‘demanded

by the rules – but as Australian skipper John Bertrand noted in his book Born to Win, the real frustration was that they had not thought of it themselves. Liberty pulled the rating certificate trick for the final race, and Australia II’s crew found themselves racing a different, lighter boat that had more sail area and was more competitive in conditions that had previously left the defender in their wake. The indelible drama of that race lives on for everyone on the water, and

top: Hull lines of Australian, reproduced from Sydney Sails – the story of the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron’s First 100 Years, published by Angus & Robertson 1962.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 18

the worldwide audience watching live on TV – especially those of us night-owls viewing in Australia.

As Australia II trailed on the reaching legs the keel’s extra drag weighed on the crew’s mind, its upwind advantages nullified by the now-changed Liberty By then, however, the keel had done its job – psychological and actual – while the winning break came from Australian teamwork. The afterguard chose the right wind shifts to follow. Months of recutting the spinnakers, with advice from sailmaker and tactician Hugh Treharne, provided better downwind sails. In tricky conditions they sailed through from behind to lead again at the last mark as the US team panicked. The crew’s concentration kept them in front during the final, nail-biting leg, and the cup left America after 132 years.

Australia had won sailing’s Holy Grail with a blueprint for success: innovative design, attention to detail on every aspect of the project, and a strong team proud to sail their boat for their country. Walter Reeks had observed of the US defender in 1903: ‘Building a yacht to defend the prestige of their country is looked upon in America from a national standpoint. Every man helps.’ Australia II had this commitment all through the campaign, and it remains a pinnacle of Australian sporting achievement.

What happened to wings on keels after 1983? Though heralded by some as the next big thing, history suggests otherwise. Certainly a number of racing and even cruising keels swiftly spread underwater wings, but many bodies controlling yacht racing shut the door, banning them as an unnecessary complication that could make existing craft obsolete. They were permitted by the two remaining International Metre-boat classes still racing, the 12 and 6 Metres, something of a niche market.

The 1987 America’s Cup 12-Metre designs featured a flock of highly refined keels with wings of various proportions, angles and sweep – and that was about as far as it went. It was the last series raced in the old 12 Metres. When the new America’s Cup class of lightweight 25-metre-long monohulls emerged in the 1990s, they allowed much deeper-draft and high-aspect ratio keels with large torpedo-like ballast bulbs. Wings became smaller and barely contributed to ballast, beginning a path back toward the size of endplates – which is more or less where the journey had started.

Back in 1983, the focus on Australia II’s keel distracted attention from the team’s

As the late designer’s supporters sprang to defend his reputation, the revolutionary skiff Taipan was a trump card

breakthroughs in hull shape – the canoe body, in yacht design jargon, which can be seen clearly in photographs of the test tank model in the museum’s collection. Once again Lexcen’s supporters have strongly challenged recent claims of significant Dutch input into shaping the hull, pointing out that Lexcen had not been satisfied with the initial ‘final shape’ that had been refined through the testing. John Longley recalls Lexcen delaying the yacht’s fabrication as he went over the lines on his knees, working by hand to modify them during the full-size lofting of the design at Steve Ward’s shed in Cottesloe, Western Australia, until he was happy with the final shape.

This final hull shape, and the radical package it was part of, has a number of conceptual elements that are eerily similar to a remarkable Sydney yacht from 1858, and these begin with its name, Australian Built at Woolloomooloo by Dan Sheehy from a design by Richard Hartnett, Australian was a Sydney Harbour sensation, winning races until the mid-1880s. It had a very low handicap for its size, achieved by exploiting the rules with a clever location of the rudder that significantly reduced the length measurement used in the rating rule of the time. It was an interesting example of lateral thinking, just like Australia II – and like her, this made the authorities and competitors unhappy.

Australian’s hull design was remarkable and different too. Thirty years later Walter Reeks described it as ‘almost the perfect vessel’. It featured a deepveed, double-ended hull shape with semi-circular longitudinal lines. Its mathematically precise hull shape was based on Hartnett’s dissection of the streamlined body of a mackerel he caught.

If you compare the bodyplan (the fore and aft sectional view of the hull) on both yachts, there is a strong sense of déjà vu in that of Australia II. Both show a very

similar constant deadrise as their respective hull sections rise from the keel. But Lexcen was not copying Australian; he was pushed toward the outcome by the 12-Metre rule.

Its restrictions relating to heavy displacement and a girth measurement (a crucial part of the complicated 12-Metre formula) force designers to use a deep-vee midsection, and in the 1970s and early 80s the deadrise of the hull from the keel and centreline became relatively flat-sided. The fore-and-aft hull sections either side of the girth measurement station (near midships) then followed a very similar section shape to fair into the mid-section. This produced a hull with an almost constant deadrise to the sections throughout much of the hull.

Looking side-on at the profile, Australia II also recalls Australian’s semi-circular lines. Australia II had a shorter waterline compared to conventional 12 Metres of the period. It was able to reduce both displacement and drag-causing wettedsurface area, by removing volume in the region between the keel and rudder (known as the skeg or bustle). Taking out the skeg allowed the parallel sections of Australia II to run through well into the stern, so the hull lines approach being double-ended. It also created a circularlooking run to the profile and the longitudinal lines – all affinities with Australian’s hull form.

At this point, the ghost of Walter Reeks joins us again. In 1889 he proposed an Australian challenge for the America’s Cup in the great era of 100-foot cutters, and was happy to submit to the Deed of Gift, no concessions asked. He was even prepared to sail a challenger from Sydney to New York ‘on its own bottom’. Reeks went to the USA to discuss the challenge and examine the successful 1887 defender, the Edward Burgessdesigned Volunteer. Reeks proposed a design of the maximum allowable 90 feet (27.43 m) on the waterline that would follow the principles of Australian, described by Reeks as ‘an approximation of the best forms known to modern times’. He was unable to secure financial backing, so the venture never proceeded.

Given the success of Ben Lexcen’s Australia II, it is curious to think what a similar-shaped hull might have done for Australia almost 100 years earlier if there had been an entrepreneurial, colonial-era Alan Bond to support the project. There wasn’t, so our generation was lucky to have Ben Lexcen, Alan Bond and John Bertrand to finish off the job in spectacular style almost a century later.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 19

Australia II tank test model

The wooden tank test model of Australia II is a work of craftsmanship in its own right, painted a gaudy, high-gloss yellow with contrasting black grid lines so that the wave patterns could be observed easily as it was towed along the tank and filmed at the same time.

Made of a local European pine, it is fabricated in the time-honoured ‘breadand-butter’ layered method used for model yachts and builders’ half-models. The joints between the lifts, as each layer is called, were cut exactly to a waterline (a horizontal section through the hull) by an early form of computer-controlled milling. The stepped shape left by the large number of squareedge lifts was faired down to the joints by hand to create the final hull shape,

to bring the model down to its correct floatation trim.

At 1:3 scale the test model is itself a small yacht, which the designer hopes will closely replicate the performance of the fullsize hull. Large-scale models like this ensure more accurate measurements of resistance and observations of wave patterns or water flow. As long as the test conditions are exactly replicated, designers hope that comparisons between different models will demonstrate the real performance of the full-size versions.

Nonetheless some questions remain about how accurately the results can be extrapolated to full-scale predictions. This might partially explain why the conclusions in the final report on Australia II ’s model tests suggested it would have ‘about a seven-minute lead at the finish’ in a moderate wind, when the margin was much closer for many races.

ANMM registrar Cameron McLean with the Australia II tank test model in a museum storage facility. The stern view shows the hollowed-out skeg area, lines converging into a double-ended hull form below the waterline. Winglets on the keel are clearly visible. ANMM collection, gift of America's Cup Defence 1987 Limited. Photographer A Frolows/ANMM

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 20

Quest for the South Magnetic Pole

For over 150 years, explorers risked their lives in desolate Antarctica to plant a flag at a shifting point on the Earth’s surface. This exhibition from South Australia recalls one of history’s oddest and most protracted quests – and salutes the Australian scientist who came as close as possible to the elusive South Magnetic Pole.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 21

The exhibition poses a surprising question that challenges Mawson’s achievement: did he plant the flag in the right place?

Friday 16 January 2009 marked the 100th anniversary of Douglas Mawson planting the British flag at the South Magnetic Pole. The achievement was commemorated with flights over Antarctica, postage stamp issues and an exhibition, Quest for the South Magnetic Pole. The exhibition has now reached our galleries, where it poses a surprising question that challenges Mawson’s achievement: did he plant the flag in the right place?

Developed in collaboration with the South Australian Maritime Museum and South Australian Museum, with support from Visions of Australia, Quest answers its own question and goes on to explore the science of magnetism – how the Earth’s magnetic field works, what the South Magnetic Pole is and why scientists and explorers were so keen to locate it. It also shows how scientists and explorers live, work and survive in this extreme environment.

Magnetic mysteries

In 1600, English scientist William Gilbert postulated that the Earth is a giant magnet, and that this is the reason a compass points north (and not, as had previously been thought, due to the influence of the pole star Polaris, or a magnetic island on the North Pole). Later scientists and explorers devoted their efforts to understanding how these magnetic forces work and why a compass needle constantly veers off true north.

overleaf: Northern Party at the South Magnetic Pole. Mawson set up the camera before the shutter cord was pulled by expedition leader Edgeworth David. Photographer Douglas Mawson 1909. Courtesy Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum

left: Getting ice on the glacier in drifting snow. High velocity wind. Photographer Frank Hurley 1912. Courtesy Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum

opposite: Bob Bage cooking, Frank Hurley in sleeping bag. Mawson's Southern Sledging Party. Photographer Xavier Mertz 1912. Courtesy Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum

Driven by curiosity and a desire to improve navigation, scientists had established by the 19th century that a compass needle is pulled towards a magnetic – rather than the geographic – pole, and that the North and South Magnetic Poles are constantly on the move.

We now know that the magnetic poles are the extremes of a magnetic field generated by molten metal churning around the Earth’s core. Just as that molten metal is never static, so the poles are also constantly shifting – sometimes travelling up to 30 kilometres a day. Yet despite being a moving target, the South Magnetic Pole attracted explorers 100 years before the better known – and fixed – geographic pole that lies at the end of the Earth’s rotational axis. While many exhibitions have profiled Antarctic exploration, Quest is the first to feature the search for the South Magnetic Pole.

The quest begins

In 1831, dashing British polar explorer James Clark Ross proved that it was possible to reach the North Magnetic Pole. Embarking on a sledging journey in the Arctic from his ice-bound ship Victory, he observed the needle on his dip circle (a three-dimensional compass) point to the vertical. The race was on to locate its southern counterpart.

German scientists Humboldt and Gauss subsequently established a string of observatories throughout the world

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 22

that could take simultaneous observations. From these readings, the pair calculated the likely position of the South Magnetic Pole. Spurred by these tantalising coordinates, three separate expeditions set out in the late 1830s to search for it and to explore Antarctica. They were led by Frenchman Jules Dumont d’Urville, American Charles Wilkes and Briton James Clark Ross. International rivalry was intense and there was no warmth when the French and American expeditions encountered each other in the ice-pack. Instead, they tacked and sailed the other way!

These 19th-century voyagers took astounding risks to negotiate ice-choked waters in timber sailing ships. Although all three expeditions failed in their quest, the consolation prize was the charting of vast tracts of the Antarctic coast and the identification of hundreds of new species. To 20th-century explorer Roald Amundsen, ‘these men were the real heroes … those who sailed right into the heart of the pack.’

Antarctic landings

A revival of whaling in the late 19th century prompted a Norwegian expedition to venture into Antarctic waters seeking new whaling grounds. Signed on as expedition scientist was a brash young Norwegian, Carsten Borchgrevink. In January 1895, he leapt ashore and declared himself the first person to stand on continental Antarctica.

Borchgrevink subsequently mounted his own expedition in 1898 on the Southern Cross, drumming up funding on the promise of finding the South Magnetic Pole. The expedition’s scientific party would be the first to winter on the Antarctic landmass.

Meanwhile, a young Tasmanian physicist named Louis Charles Bernacchi, desperate to voyage to Antarctica, bombarded the local press with articles on the importance of sending an Australian expedition to the region. He caught a lift with Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross, becoming the first Australian to land on the continent and the first scientist to conduct magnetic research there.

Bernacchi would later be recruited as physicist for the 1901–04 Discovery expedition led by British Captain Robert Falcon Scott, living on the iced-in ship that served as a base for an attempt to reach the South Geographic Pole. The trekkers were forced to turn back after two months, suffering snow blindness and scurvy but having reached 82° south.

Ernest Shackleton was a veteran of Scott’s failed attempt to reach the Geographic Pole. In 1907–09, Shackleton led his own epic expedition south on the Nimrod intent on reaching both the magnetic and geographic poles. In October 1908 he sent three men out on a sledging journey in search of the magnetic pole.

The exhibition relates the gripping tale of this Northern Party’s bid. Douglas

Mawson, T W Edgeworth David and Alastair Mackay hauled sledges (initially weighing 200 kg) more than 2,000 km in gruelling blizzard conditions over largely unmapped terrain. In their attempt to reach the pole, they ditched mineral specimens, equipment and food to lighten the load, living off seal blubber and penguin meat. On 15 January 1909 they took a final reading of the dip circle, and the next day sledged several more kilometres and hoisted the British flag.

However they had niggling doubts about the ‘dip’ of their compass needle that eventually proved founded. Soon after they rejoined Nimrod, they realised that the magnetic pole had eluded them. In fact Mawson, Edgeworth David and Mackay had been forced to pull up over 100 kilometres short of their goal.

Now a seasoned Antarctic explorer, Mawson raised funds for a new Australian-New Zealand expedition. Setting up base at Cape Denison, one of the most desolate places on Earth, four parties set out in the summer of 1912 to map the continent. The Southern Sledging Party – Australians Frank Hurley and Robert Bage and New Zealander Eric Webb – resumed Mawson’s quest for the South Magnetic Pole.

This time the terrain was featureless and there were no animals to hunt when the food ran out. Battling frostbite, snow blindness, exhaustion and starvation, the group was forced to turn back a crushing 60 kilometres short of their goal.

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 23

Ultimately, their journey would be overshadowed by Mawson’s own epic bid for survival following the death of his two companions on the Far Eastern Sledging journey.

Charles Barton takes up the quest

After World War I, interest in reaching the South Magnetic Pole waned. Scientists on Mawson’s 1928–30 Discovery expedition focused their efforts on reoccupying old magnetic stations to measure changes in the Earth’s magnetic field. It would be the 1980s before Australian geomagnetist Dr Charles Barton took up the challenge again.

By now the wandering pole had moved out to sea, and what had once been a sledging race against time now became a thrilling seaborne quest. Working for Geoscience Australia, Barton developed a fluxgate magnetometer to measure the strength and direction of the magnetic field at sea.

In 2000, Barton mounted a private expedition on the Antarctic ship Sir Hubert Wilkins. Frustratingly the constantly shifting pole proved faster than his slow-moving vessel. Finally, however, on 22 December, the forces of nature relented: the pole slowed and Barton’s instrument recorded a distance of 1.6 kilometres – the closest anyone had, or could ever hope to come, to the South Magnetic Pole. The quest had finally come to a conclusion, at sea, from a ship – and with surprisingly little fanfare.

The exhibition

Initially shown at the South Australian Maritime Museum from May–October 2009 to coincide with the anniversary of the Mawson’s Northern Party achievement, Quest traces the story

Charlie Barton recorded a distance of 1.6 kilometres – the closest anyone had, or could ever hope to come, to the South Magnetic Pole

of the search for the South Magnetic Pole and highlights Australia’s significant role in the race. The exhibition draws on the riches of the South Australian Museum’s Mawson Collection. This collection of Antarctic artefacts, papers and photographs, rare books, reports and maps numbers over 100,000 items, many of which belonged to Sir Douglas Mawson (1882–1958), university geologist and polar explorer.

On display are scientific instruments, sledging equipment, cameras and provisions taken on both the British and Australian sponsored journeys. Items include the Northern Party’s map (annotated by Mawson and his companions), a dip circle and a manhauling sledge. Personal items include expedition skis and poles, a Nansen cooker, finnesko (reindeer-skin) boots and wolf-skin mitts and a three-man reindeerskin sleeping bag.

Stunning historic images, including photographs from Shackleton’s Nimrod and Mawson’s Aurora expeditions, are displayed. They include dramatic

3D images captured by innovative stereo cameras and lenses carried by Shackleton and Mawson. Soundscapes conjure up the roaring winds of the plateau, and the experience of sheltering in a flimsy canvas tent during a raging blizzard. There’s a strong interactive component. The Lucky Dip explains how the Earth’s magnetic field works, and demonstrates the instrument used by early explorers to locate the South Magnetic Pole. The Pulley Hauley encourages visitors to climb into a replica man-hauling harness and imagine hauling a heavy load over wind-swept ice. Visitors can also dress in replicas of polar explorers' specialised clothing.

A special exhibit is an extremely rare edition of Aurora Australis – printed on site at Shackleton’s winter quarters and the first book written, printed and published entirely in Antarctica. Charlie Barton’s fluxgate magnetometer, which he employed in 2000 to finally pinpoint the elusive South Magnetic Pole, is definitely a highlight of this exhibition.

Dr Charles Barton will be a special guest at the museum’s opening of the exhibition Quest for the South Magnetic Pole on 2 July 2010. This travelling exhibition from the South Australian Maritime Museum and South Australian Museum appears in Gallery One until 17 October. This article was edited from their material by Penny Crino. The exhibition is supported by Visions of Australia, an Australian Government program that assists the development and touring of cultural material across Australia.

left: Aurora Australis, the first book written, printed and published entirely in Antarctica. Ernest Joyce and Frank Wild 1908. Courtesy Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum

left: Aurora Australis, the first book written, printed and published entirely in Antarctica. Ernest Joyce and Frank Wild 1908. Courtesy Mawson Collection, South Australian Museum

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 24

right: Charlie Barton alongside his fluxgate magnetometer on the Sir Hubert Wilkins, December 2000. Nicknamed ‘Charlie’s Bird, it jutted out from the ship’s stern, removing it from the vessel’s magnetic field. Photographer Gregory Haremza. Courtesy Charlie Barton

Members

Members welcome Jessica News

Relaunching the lavishly refurbished, classic Halvorsen cruiser Silver Cloud at our wharves last March was a champagne event for Members.

Photographer Michael Ellem

As the 16-year-old Australian singlehanded sailor Jessica Watson neared the end of her epic voyage we organised a ferry to take our Members out to greet her as she entered the harbour, the youngest person to sail solo around the world.

Welcome to another quarter of exhibitions, activities and events for you to enjoy.

We don’t let the winter chill slow us down here, so do come in for a visit over the winter months. All event details are overleaf.

We host some interesting visiting vessels. The classic old Halvorsen Silver Cloud was re-launched here in March. Ella’s Pink Lady, the S&S 34 made famous by plucky 16-year-old Jessica Watson, berthed here after her world voyage and triumphant return in May. Don’t miss the Plastiki, here in June. She’s built from plastic bottles and recycled materials, and is sailing to us across the Pacific Ocean from North America. You can hear designer Andy Dovell talk about the project and inspect this extraordinary vessel.

Our traditional annual Navy mess dinner in the HMAS Vampire Wardroom is coming up, with dining President Captain Paul Martin RAN (Rtd) who commanded Vampire in 1982–83. You’ll have a chance to tour Spectacle island, repository of Royal Australian Navy heritage items, conducted by RAN museums director CMDR Shane Moore ran. And we’ll be out on the water in the Sydney Heritage Fleet vessels Lady Hopetoun and Waratah

Among our guest speakers this winter is the popular media personality, journalist and author Mike Carlton who’ll talk about his new book Cruiser: the life and loss of HMAS Perth. Aficionados of the other kind of cruiser won’t want to miss P&O archivist Robert Henderson’s half-day history of P&O

in Australian waters. He’s bringing classic images and films – many previously unseen – from his own collection and P&O Orient Line archives. Don’t miss this one!

You’ll find the winter’s exhibitions on page 32. A personal favourite is Sons of Sindbad: The photographs of Alan Villiers. This famous Australian writer and photographer had a lifelong passion to record the passing of the age of sail. in the late 1930s he sailed with Arab dhow masters from the Persian Gulf to Zanzibar, East Africa, recording age-old indian Ocean sailing traditions. A special guest will be Kate Lance who wrote the award-winning biography Alan Villiers: Voyager of the Winds

We have plenty for your children, too. The NSW Department of Primary industries (Fisheries) is coming back with its workshop Fishing for Kids to teach responsible fishing practices to children. They’ll get a chance to catch some of those increasingly big fish we see swimming around the museum wharves since the commercial fishing ban a few years ago.

We will be contacting many of you shortly as we undertake a survey of our Members so that we can receive your feedback and suggestions and try to serve you better. These may be online or by post. Do please take a few minutes to complete the survey, to help us build an even better Members program for you.

On behalf of the Members team, i look forward to seeing you here very soon.

Adrian Adam, Members manager

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 25

Photographs courtesy of Member David Mueller

Members events

Calendar Winter 2010

Friday 18 Lunchtime talk & view: Portraits of a shipping company

Sunday 27 Viewing: Ghost Ships with Max Gleeson

To be advised Talk & viewing: The Plastiki project

July

Thursday 1 Preview: Quest for the South Magnetic Pole

Saturday 10 On the water: Cruise on Lady Hopetoun

Wednesday 14 For kids: Fishing for Kids

Saturday 17 Special: HMAS Vampire Wardroom dinner

Thursday 22 On the water: Spectacle island naval heritage tour

Sunday 25 Talk: Sons of Sindbad – Alan Villiers

Thursday 29 Talk: Life & loss of HMAS Perth, with Mike Carlton

Sunday 8 Talk: Documents that shaped Australia

Saturday 14 For kids: After-dark ships & museum torch-light tour

Tuesday 17 Lunchtime curator talk & view: Macquarie’s Light

Sunday 22 Special: History of P&O Cruise ships – films & lecture

September

Saturday 4 On the water: Cruise on Waratah

November

From Friday 19 Overseas tour: The floating world of Cambodia

How to book

it only takes a phone call to book for these Members events … have a credit card ready and we can take care of payments on the spot.

• To reserve tickets contact the Members office: phone 02 9298 3644 (business hours) or email members@anmm.gov.au Bookings strictly in order of receipt.

• If phoning, have credit card details handy.

• If paying by mail after making a reservation, please include a completed booking form with a cheque made out to the Australian National Maritime Museum.

• The booking form is on reverse of the address sheet with your Signals mailout.

• If payment is not received seven days before the event your booking may be cancelled.

Booked out?

We always try to repeat the event in another program.

Cancellations

if you can’t attend a booked event, please notify us at least five days before the function for a refund. Otherwise, we regret a refund cannot be made. Events and dates are correct at the time of printing but these may vary … if so, we’ll be sure to inform you.

Parking

Wilson Parking offers Members discount parking at nearby Harbourside Carpark, Murray Street, Darling Harbour. To obtain a discount, you must have your ticket validated at the museum ticket desk.

Lunchtime talk & viewing

David Moore –Portraits of a shipping company

12 noon–1.30 pm Friday 18 June at the museum

Australian photographer David Moore was commissioned by Columbus Line to create photographic portraits of their shipping activities. The company began operations between North America and Australia/New Zealand in 1959 and was the first company to regularly schedule a containerised shipping service. Join curator Paul Hundley for an introductory talk and guided tour.

Members $15, general $20. includes light lunch and refreshments, Coral Sea Wines

Viewing

Ghost Ships of the Coast Run –a new film by Max Gleeson

2–4 pm Sunday 27 June at the museum

Shipwreck authority and experienced wreck diver Max Gleeson presents his new documentary about the loss of colliers Woniora, Birchgrove Park and passenger/ cargo vessel Bega. Historical images and movie footage skilfully bring these stories to life, and spectacular underwater scenes let you join the divers as they venture down 80 metres deep to film the wrecks and surrounding marine life.

Members $15, general $20. includes canapés and Coral Sea wines

David Moore Columbus Line portraits

June

August

Photographer David Moore Hamburg

Süd

Si GNALS 91 J UNE TO AUGUST 2010 26

Collection

Talk & viewing