Introduction

In 1955 USSR started an extensive housing programme aimed at resolving the serious housing shortage that emerged in the post-war years. This essay explores the connections between ideas behind the projects developed in Moscow in the context of this programme and those put forward in the West in the 1920s by modernist movement representatives and avant-garde architects in Russia. It aims to demonstrate how housing policy pursued by Khrushchev and elevated by him ‘unprecedentedly to a top national political priority’1 [as a result, 80 million sq.m were built only from 1956 to 1959] brought to life the ideas of the Western modernists. It also explores how these ideas (the reality in the USSR) were different due to the contemporary social, political and economical context of the time. An important milestone of this period was the Experimental 9th microdistrict of Cheryomushki built in Moscow in 1957, because it was a testing bed for all microdistrict mass housing projects built afterwards all over the country2 and I will explore this project in more detail further.

The analysis below demonstrates that there can’t be established with certainty any specific projects that Soviet planners and architects learned from but that there is a very clear notion of ideas travelling through time and shared by the architects of Western3 modernism, Russian avant-garde architects and Soviet modernists of the 1950s.

Terminology, especially used across borders and cultures can be misleading, and in particular the notion of ‘modernist’ requires special attention. There are different views on how to label the architecture of the Khrushchev period, although ‘Soviet modernist architecture’ is the most common one [I will also be using this term in my work]. However, in their work ‘Moscow: A guide to Soviet modernist Architecture 1955-1991’ Anna Bronovitskaya, Nikolay Malinin and Yuri Palmin refer to it ‘with some trepidation’4 . Among reasons for this they mention the fact that architecture of this period was extremely heterogene-

1. Miles Glendinning, Mass housing: modern architecture and state power-a global history (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021), 299.

2. Kuba Snopek, “Belyayevo Forever: How Mid-Century Soviet Microrayons Question Our Notions of Preservation” (Archdaily, 2015), shorturl.at/ezDGT.

3.The ‘West’ here refers to Western Europe with focus on Germany, France, Netherlands.

4. Anna Bronovitskaya, Nikolai Malinin, Yury Palmin, Moscow: a Guide to Soviet Modernist Architecture 1955-1991 (Moscow: Artguide s.r.o. for Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2019), 9.

ous and therefore it can be difficult to give all of it one unifying title.

Historical context

To understand the context in which the mass housing construction in the USSR emerged in the 1950s it is important to consider its historical background and the timeline that led to the decree ‘On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction’ issued by the Central Committee of KPSU and the USSR Council of Ministers on the 4th of November 1955. The decree defined that ‘<...> in the works of many architects and design organisations there is a widespread externally decorative aspect of architecture, abounding in great excesses, which does not correspond to the policy of the Party and Government in the field of architecture and construction’5. A new focus on speed of construction, simplicity, proportionality and economical reasonability of prefabricated housing was prioritised from there on.

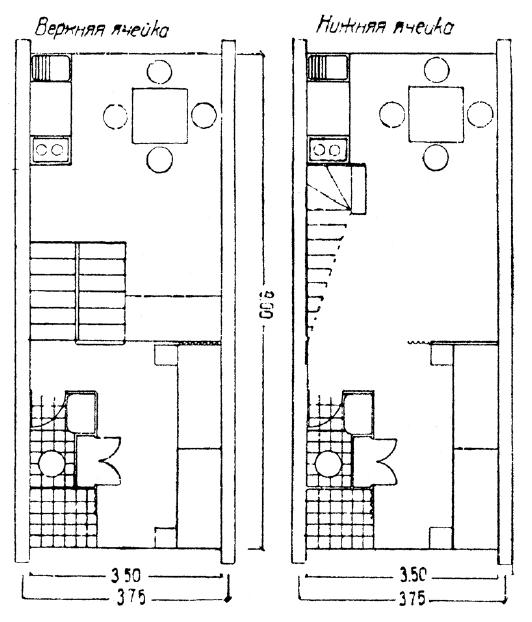

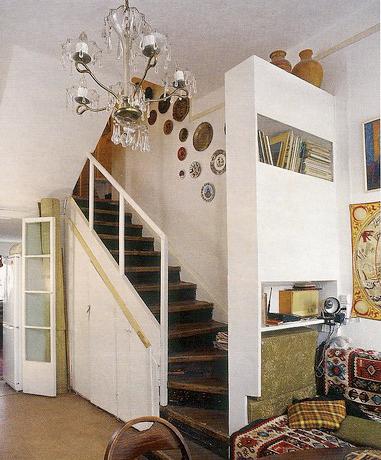

The October revolution of 1917 and the end of the civil war marked a new era: creation of a new country, new person, new society and of course new architecture that could accommodate them. Anatoly Kapp in ‘Town and revolution’ puts it this way: ‘For the avant-garde of the Soviet architects of the twenties, architecture was a means, a lever to be employed in achieving the highest goal that man can set himself. For them architecture was, above all, a tool for transforming mankind’ 6. Architecture spanning over seven years from 1925 to 1932 brought a new housing type: ‘dom-kommuna’ (house-commune). This structure was believed to be a ‘socially superior mode of life’ ought to be designed for a new worker of the time. Architectural proposals for standardised living units by O.S.A7 published in 1927 ‘in many ways anticipated subsequent developments in the West’8. Parallels in the architectural diagram of a two-level living unit with interior street designed by O.S.A, and Unité d’habitation in Marseilles by Corbusier can be found (Fig.1-2). This case is only one from a broad list of ex-

5. Full text of the decree: “On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction” (Strelka Mag, 2020), https://strelkamag.com/ru/ article/postanovlenie-ob-otkaze-ot-izlizhestv-full

6. Anatole Kopp, Town and Revolution. Soviet Architecture and City Planning 1917 - 1935 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1970), 12.

7. O.S.A (Organisation of Contemporary Architect): an architectural association in the Soviet Union, which was active from 1925 to 1930 and considered the first group of constructivist architects.

8. Anatole Kopp, Town and Revolution, 130.

amples which illustrate how much did the ideas travel at the time between Soviet Union and the West and how exchange between the architects occurred. This vast area lies beyond the scope of this essay, however I would like to stress the importance of this exchange.

Another example of such an ideological exchange was that one of the most well-known representatives of the international CIAM organisation, Ernst May was invited to Russia in 1929 as a Chief Engineer of Planning and Housing to develop the workers settlement in Magnitogorsk9 It happened following the impression he made on the Soviet government by the success of his workers housing settlement project in Frankfurt10. In his work in the USSR Ernst May promoted CIAM-style zoning planning and industrialised concrete Zeilenbau apartment blocks. It was another step towards the future shift to industrialised CIAM-style planning in the 1950s11 .

The year 1932 and specifically the design competition for the Palace of Soviets12 (Fig. 3) signified a breaking point, a crisis of the modernist movement in Russia and cooling in relationships with the CIAM movement. The new ideology officially accepted the ‘socialist realism’ style of art which was illustrated by Lunacharsky’s13 speech in which he claimed that ‘the future Palace of Soviets must be monumental and bear witness to the grandeur of the proletariat’14. Thus, the working-class collective living gave place to classical architecture, grand facades, wide roads and monumental buildings serving for engraving the names of the Great into the history. As for the housing, despite the official eloquence, the whole Stalinist period was characterised by a serious gap between spacious richly decorated apartments provided for Party nomenclatura and other privileged parts of society and overcrowded ‘kommunalkas’ where the majority of the population was cramped.

Stalin was succeeded by Nikita Khrushchev in 1953 who announced a policy of tackling the acute housing shortage (heritage of the 2nd World War and Stalin regime) to be one of the new nation’s main pri-

orities. Unlike the functionalists of the 1920s who had neither industrial, nor economic base to successfully develop their ideas, Soviet architects 30 years later were not constrained that way thanks to transition to industrialisation and improvement of construction methods and pace. Two important documents illustrate the beginning of this period: the decree ‘On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction’ issued in 1955 and another one issued in July 1957. The latter promised to ‘liquidate the housing problem’ in 10 years, followed by a 7-year plan launched by Khrushchev in 1958 aiming to build 15 million new city apartments based on a principle ‘one family, one flat’15 .

A significant ideological shift that happened during this time was in the attitude towards architecture as a discipline from understanding it as a high art during the Stalin period to associating it more with a technological process. Individualism was taken from the architectural profession for a while, separate studios were merged into huge, anonymous offices16 .

Cheryomushki district project

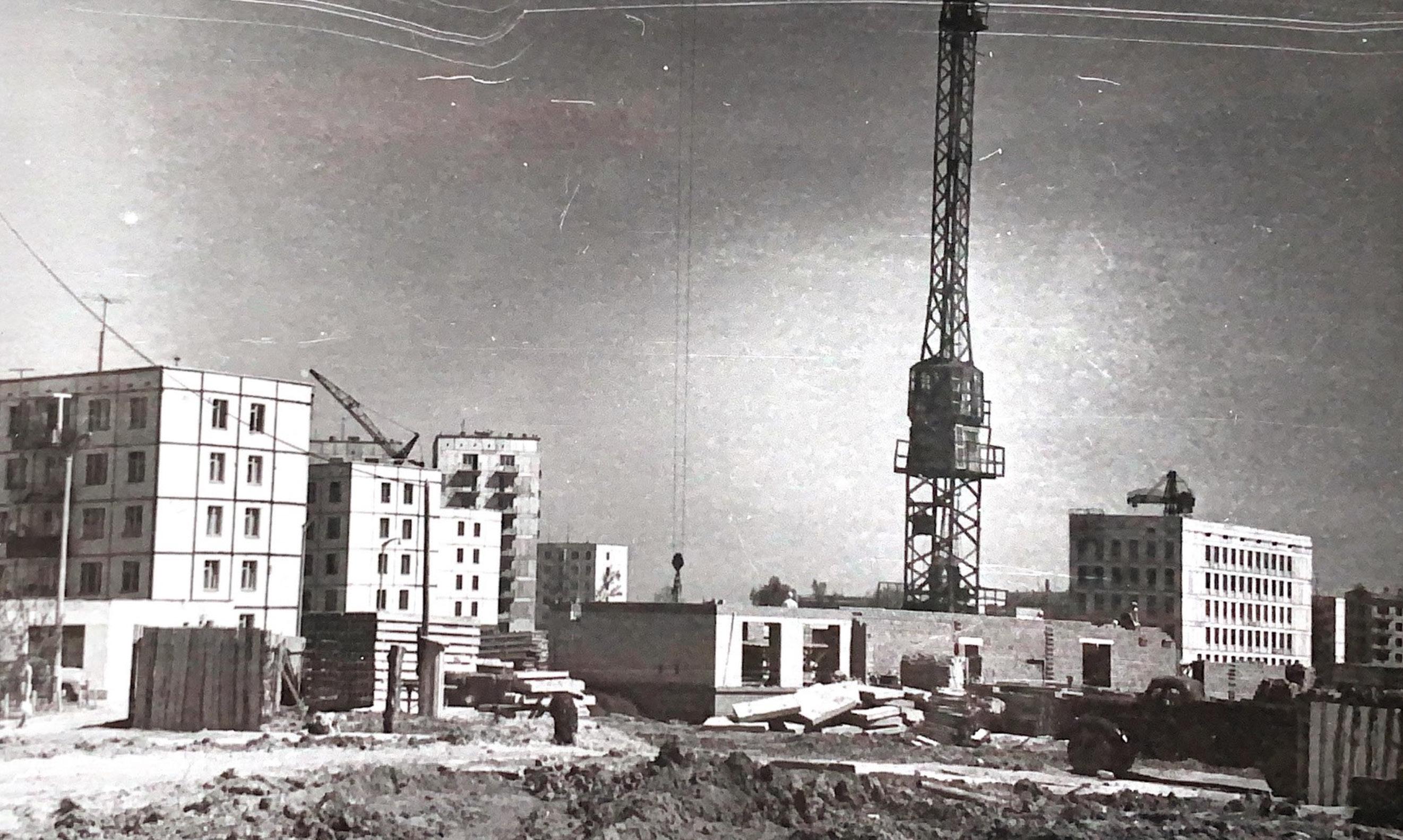

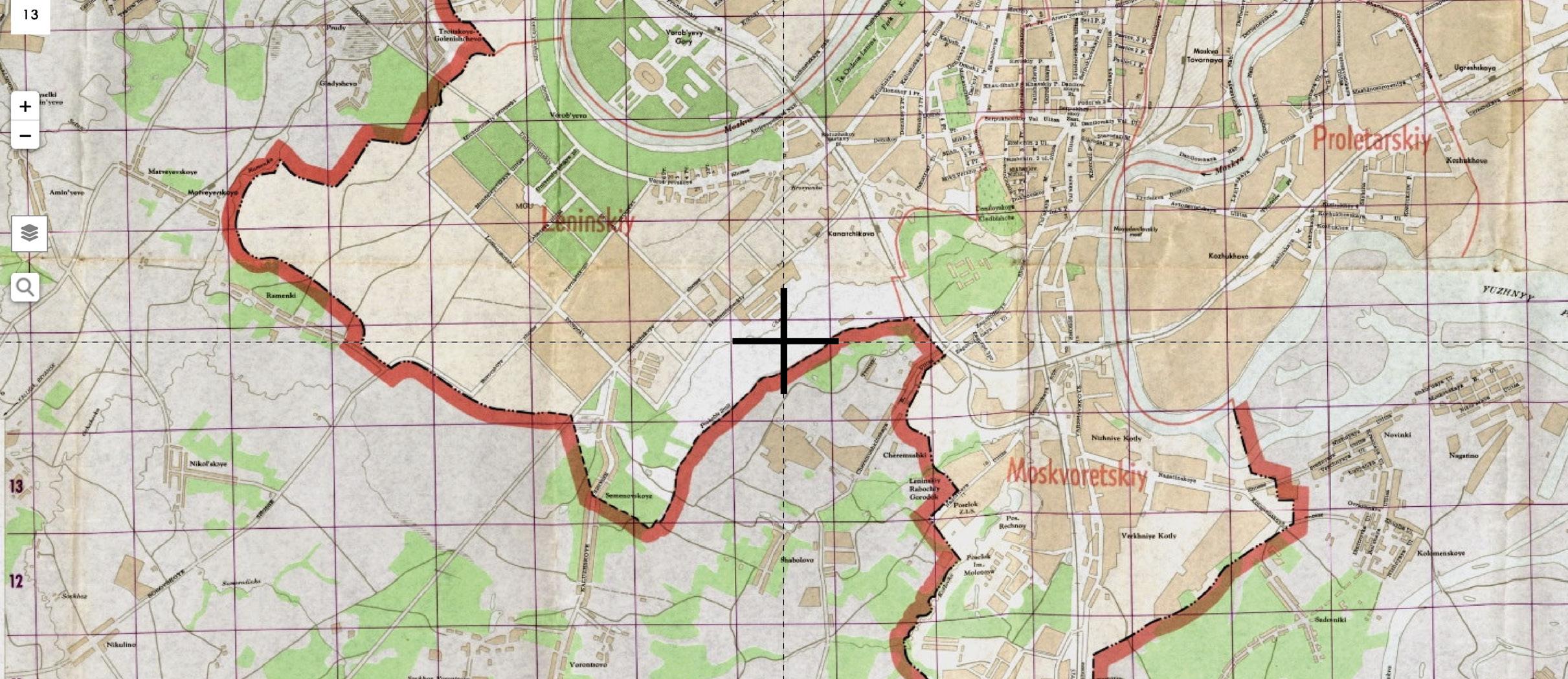

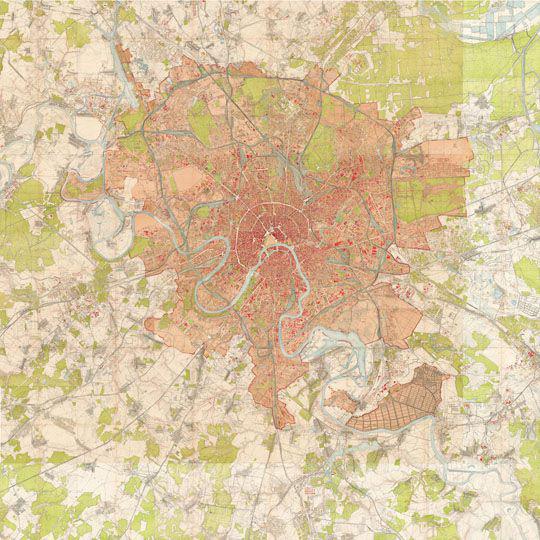

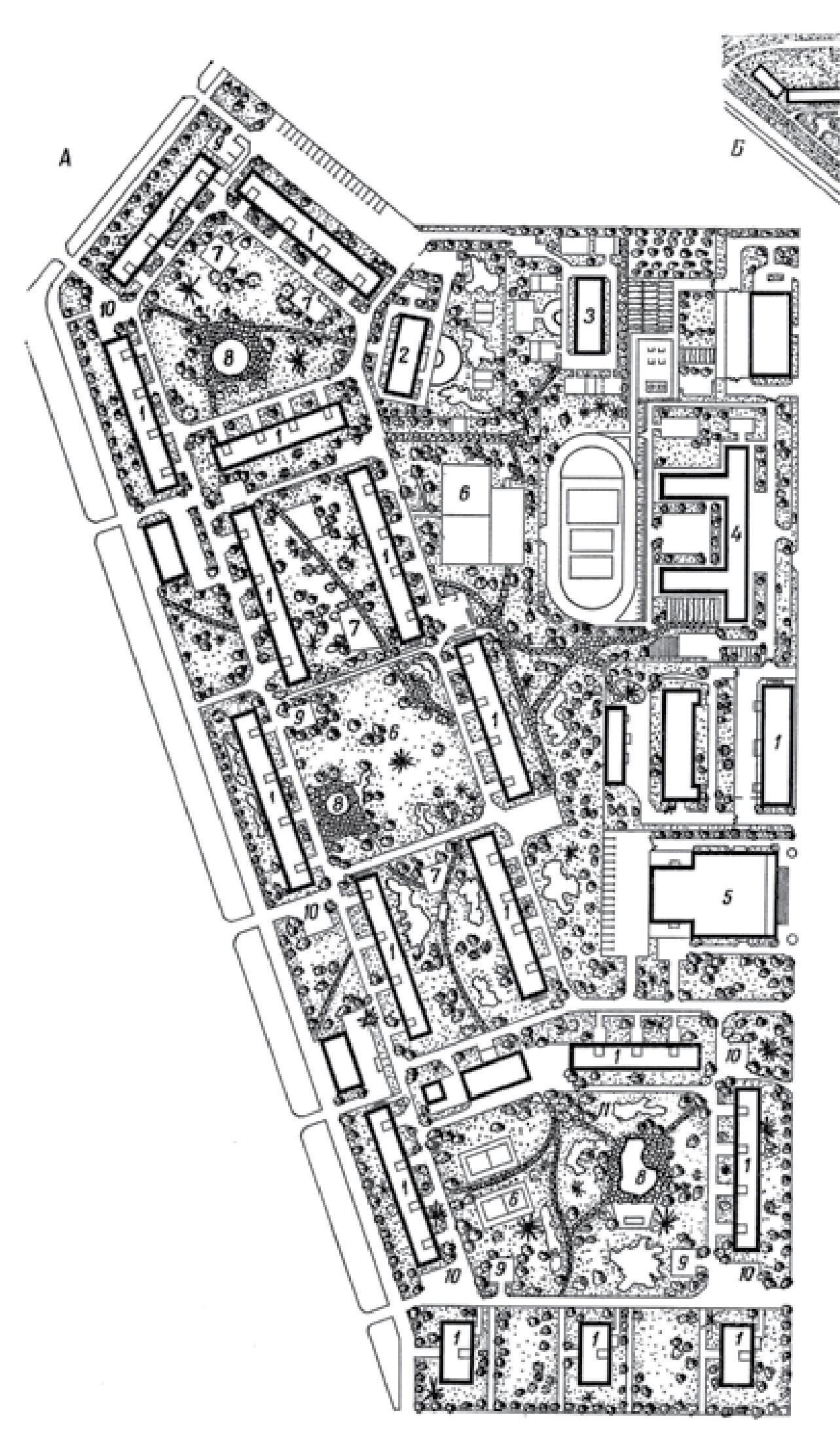

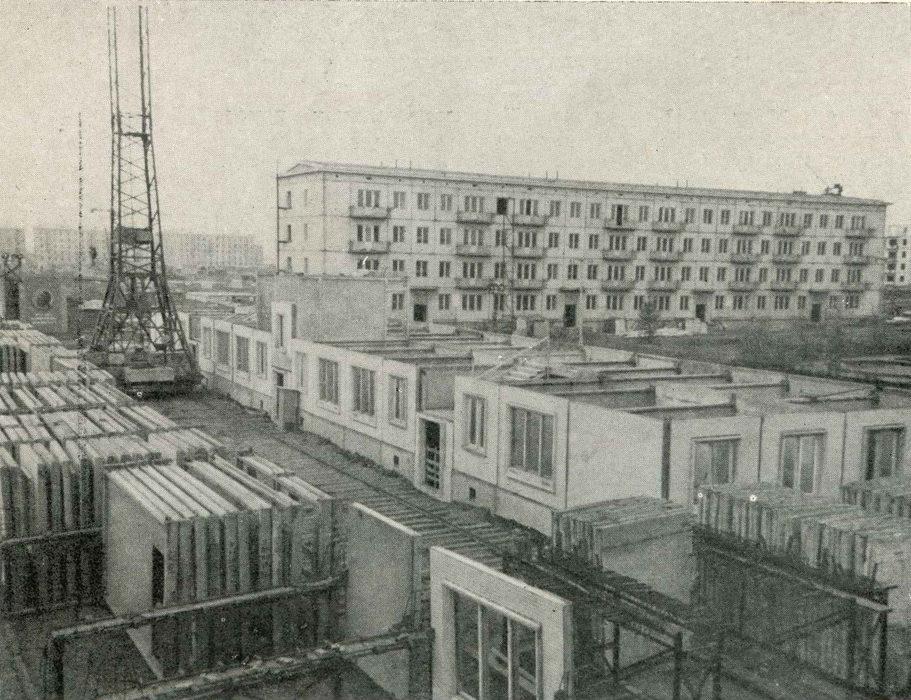

The development of new housing areas in Moscow was handled on the periphery of the city (Fig. 4-7), outside of the city border at the time. This allowed it to operate with a different type of city fabric, a ‘microrayon’ (microdistrict). One of the first built districts within the new programme was Novye Cheryomushki in the south of the city. This essay takes the first microdistrict with single-family apartments, the 9th microdistrict of Cheryomushki (Fig. 8-14), as a starting point. The reason this project is important to consider is that it was seen as a testing ground of the design and planning principles which later were implemented in microdistricts all over the country. The project was commissioned to the SAKB (Special Architectural Design Bureau). All residential houses in this microdistrict were different in terms of their construction methods, apartments layouts, materials and even furniture. The goal of the project

tionary and the first Bolshevik Soviet People’s Commissar responsible for the Ministry of Education.

14. Kees Somer, The Functional City: CIAM and the Legacy of Cornelis Van Eesteren (Rotterdam : NAi Publishers, 2007), 118.

11. Miles Glendinning, Mass housing, 51.

12.

15. Lynne Attwood, Gender and Housing in Soviet Russia: Private Life in a Public Space (Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2010), 154.

16. Anna Bronovitskaya, “Open city: the Soviet experiment”, in Volume 21, ed. Arjen Oosterman (The Netherlands: Stichting Archis, 2009), 24.

was to see in practice if the implemented designs from landscape to the bathroom shape proved themselves to be convenient for the new tenant, properly embodied the ideals of the time, and, most importantly - were economically efficient. In a way principles that underpinned the 9th microdistrict project partially mirrored some of ideas put forward in the ‘Athens Charter’ manifesto, one of the most important documents of modernist thought17 .

The size of the microdistrict was based on the minimal distance to the most critical services. Schools would often occupy the central place in the heart of the microrayon (not further than 850 m. from houses); pharmacies, grocery stores, dry cleaners were located in 10 minutes walk distance etc. This principle was established to ensure children’s safety of children who did not have to cross major roads on their way to school as well as proximity of all the necessary services to residential blocks. The idea of communal services being well-connected and closely located in relation to housing appeared in the clause 37 of the ‘Athens Charter’: ‘The new green areas must serve clearly defined purposes, namely, to contain the kindergartens, schools, youth centers, and all other buildings for community use, closely linked to housing’.

The same principles once pronounced by Khrushchev: ‘build quickly, cheaply and well’18 were dominant everywhere: all buildings besides residential were built from the same materials and using the same construction systems and did not stand out in terms of their exterior. There was no traffic allowed inside the microdistrict, the houses were set back 12 m. from the major road along the site border and protected from the noise and pollution by a row of trees19. By comparison, the 27th and the 64th clauses of the ‘Athens Charter’ state respectively: ‘The alignment of the dwellings along transportation routes must be prohibited’ and ‘As a rule, verdant zones must isolate the major traffic channels’.

Landscape in general played an important role in the concept of microdistricts. Firstly, it provided

17. It contains requirements and priorities necessary to establish a healthy, decent, humane environment for man and was created as a result of the 4th CIAM congress, putting together an outline of problems, trends and cures for the cities of the future.

18. Khrushchev’s speech at the National Conference of Builders, Architects, Workers in the Construction Materials and Manufacture of Construction and Roads Machinery Industries, and Employees of Design and Research and Development Organisations on December 7,1954 was published in Project Russia 25: Moscow (Moscow and Amsterdam: A-Fond / 010 Publishers, 2002).

19. Anna Bronovitskaya, Nikolai Malinin, Yury Palmin, Moscow: a Guide to Soviet Modernist Architecture 1955-1991, 30.

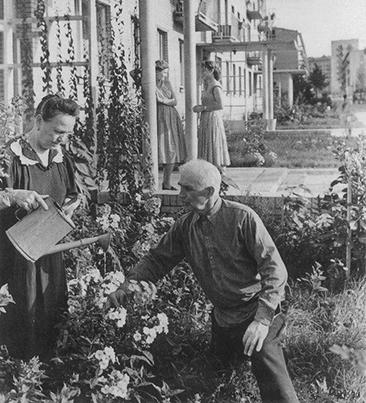

collective outdoor spaces of a true communist society: 3 padding pools still can be found in the 9th microdistrict, big courtyards formed by the residential blocks were designed for local residents’ leisure activities and more active socialisation. This point was addressed in the ‘Athens Charter’ as well in clause 35: ‘Hereafter, every residential district must include the green area necessary for the rational disposition of games and athletic sports for children, adolescents, and adults’. Flower caches and rails for climbing plants were placed on the external walls under the windows to variegate a little bit the monotonous and rough facades. Secondly, such attention to the landscape was rooted in the attempt to compensate for extremely compact areas of the new apartments (in the first edition of design norms and rules kitchen area equaled 4.5 sq.m, an apartment for a family without kids equaled 18 sq.m., ceiling height equaled 2,5 m.).

In their work on the new housing types architects at the time developed their own model of the minimum dwelling. Here similarities to the Existenzminimum20 ideology can be traced. Search for the ‘minimum dwelling’ principles emerged in similar circumstances to the Soviet housing crisis of the 1950s, during the housing shortage of 1920s in Germany, and underpinned the development of rationalised and standardised public social housing.

*Later, the ‘District and microdistrict: Manual for Design and Building’ published in 1971 will include diagrams showing scientific principles of planning mikrorayons based on the intensity of use of various services located in the district.

Social context

Within projects of this period there was a certain complicated search for balance between privatisation of family life and the ideals of collectivisation. On the one hand, building a truly socialist society required to support the strong sense of community and element of collectivity. One of the ways to avoid

20. The theme of the second CIAM congress held in Frankfurt in 1929 was ‘Die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum’ (The minimum subsistence dwelling). ‘Existenzminimum’ ideology looked into principles of designing a minimum dwelling. It was grounded in the assumption that human well-being and biological factors play far more important roles in the design than the space itself and its size.

creating a degree of privacy excessive for a socialist society was a maximum standardisation of the apartments’ interior design: the good taste was considered underpinned by modesty, simplicity and utility21 The new tenants left their old belongings behind and chose compact multifunctional furniture from the catalogues provided to them before moving in thus not falling out of the general picture too much. Sometimes the apartments provided to the workers by their employers were already furnished without tenants’ input. In addition to that, the practice of neighbourhood volunteer brigades and block community groups was revived in order to ‘maintain collective spirit’22 .

At the same time, escape from kommunalkas of the Stalin times where the notion of private life was completely obliterated and not obliged any more to share a kitchen and a bathroom with several other families was a blessing for Muscovites. Hence, they embraced the opportunity to enjoy moments of privacy in places of their own, and the level of collectivity was much lower than in modernist housing projects or in ‘kommuna’ houses in the 1920s.

An operetta ‘Moscow. Cheryomushki’ (Fig. 15-16) written by Dmitry Shostakovich in 1958 and a film from 1963 based on it by Herbert Rappaport are the perfect illustration of what the slogan ‘For each family a separate apartment’ meant at the time. In one of the scenes the young newly-wed couple runs towards the new building in which they are supposed to get an apartment and then along the windows and sing ‘Look, the whole apartment is ours, the kitchen is ours too. It will be just the two of us’. The whole film is an ironic but still beautiful illustration of how the idea of an individual dwelling occupied everyone’s minds at that period and became a miracle of the time.

Khrushchev era realising modernist ideas

In a brief interview I conducted with Kuba Snopek, the author of ‘Belyaevo forever’, he expressed an idea that the massive quantitate difference between the mass housing production process in the USSR and

West also meant a qualitative difference.

By being able to build as fast, as cheap and in such great amounts as Khrushchev (in rhetoric about Soviet mass housing Khrushchev’s name is being used to represent a collective image of the whole industry and everyone who took part in this process) embodied the modernist dream into reality. A combination of specific cultural, historical and economic circumstances created the opportunity for Khrushchev to successfully and extremely broadly implement in life ideas the international modernist movement dreamt of and promoted in the 1920s / 1930s. Reality turned out to be different from how modernists saw their concepts and had to adapt to the environment in which it developed. However, undoubtedly, it was one of the biggest, most ambitious mass housing experiments in the world which learned not only from the Russian architectural and urban background but was tied to the international experience.

Bibliography:

“100 Years of Mass Housing in Russia”. Archdaily, July 23, 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/898475/100-yearsof-mass-housing-in-russia

Alonso, Pedro Ignacio. From mass-production to mass-destruction. ARQ (Santiago) 98 (2018): 92-105. https:// dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-69962018000100092

Attwood, Lynne. Gender and Housing in Soviet Russia: Private Life in a Public Space. Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2010.

Bertaux, Daniel, Paul Thompson and Anna Rotkirch. On living through Soviet Russia. Abingdon, Oxon : Taylor & Francis Group, 2003.

Bronovitskaya Anna, Nikolai Malinin and Yury Palmin. Moscow: A Guide to Soviet Modernist Architecture 19551991. Moscow: Artguide s.r.o. for Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2019, 8-26, 29-33.

Bronovitskaya, Anna.“Open city: the Soviet experiment”. In Volume no.21 (2009), edited by Arjen Oosterman, 14-35. The Netherlands: Stichting Archis.

Bronovitskaya, Anna. “The history of mass housing in Russia”. Streamed live by KB Strelka, Moscow, November 27, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dTjt5QcGypI

Chatterjee, Choi, David L. Ransel, Mary Cavender and Karen Petrone, eds. Everyday life in Russia: Past and present. Bloomington, IN : Indiana University Press, 2015. Accessed December 19, 2021. ProQuest Ebook Central.

De Graaf, Reinier. Four walls and a roof: the complex nature of a simple profession. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017.

Erofeev, Nikolay. “The principle of economy was central. How and why the New Cheryomushki were created”. Colta, January 14, 2016. https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/9784-printsip-ekonomii-byl-opredelyayuschim

Glendinning Miles. Mass housing: modern architecture and state power – a global history. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021.

Gropius, Walter. The scope of total architecture. London : George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1956.

Hatherley, Owen. “Radical suburbs”. The Calvert journal, accessed December 19, 2021. https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/4119/polands-szczecin-philharmonic-hall-wins-eu-contemporary-architecture-prize

Hemmersam, Peter. Making the Arctic City. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021, 53-59.

Khrushchev, Nikita. “On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction”. Strelka Mag, November 4, 2020. https://strelkamag.com/ru/article/postanovlenie-ob-otkaze-ot-izlizhestv-full

Kopp, Anatole. Town and Revolution. Soviet Architecture and City Planning 1917 - 1935. London: Thames and Hudson, 1970.

Kotkin, Stephen. Magnetic mountain: Stalinism as a civilisation. Berkeley : University of California Press, 1997.

Le Corbusier. The Athens Charter. New York: Grossman Publishers, 1973.

Pavlov, G. “Time and experiments”. Tatlin, September 22, 2020. https://tatlin.ru/articles/vremya_i_eksperimenty

Snopek, Kuba. “Belyayevo Forever: How Mid-Century Soviet Microrayons Question Our Notions of Preservation’’. Archdaily, 2015.

https://www.archdaily.com/777185/belyayevo-forever-how-mid-century-soviet-microrayons-question-our-notions-of-preservation

Somer, Kees. The Functional City: CIAM and the Legacy of Cornelis Van Eesteren. Rotterdam : NAi Publishers, 2007.

Zadorin, Dimitrij. “Soviet Mass Housing Since 1948”. Video, November 23, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ZLygxXlRAxM

Table of figures:

Cover page: Photo from family archive, our house in the 24th microdistrict in Cheryomushki, Moscow.

Fig.1: Ginsburg, Moses. Dwelling. Moscow, 1934: 77. https://archi.ru/russia/image_large.html?id=282398

Fig.2: https://paulkuz.livejournal.com/7722.html

Fig.3: https://medium.com/moscowww/%D0%B4%D0%B2%D0%BE%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%86-%D1%81%D0 %BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2-%D0%B2-%D0%BC%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B 2%D0%B5-b2ddd3041aee

Fig.4: http://retromap.ru/051952_55.755665,37.615170

Fig.5: http://retromap.ru/0519722_55.755665,37.615170

Fig.6: http://retromap.ru/0519722_55.755665,37.615170

Fig.7: http://retromap.ru/0519722_55.755665,37.615170

Fig.8: GBU, General Department of Architecture and Planning. Landscaping in renovation: Approaches and Challenges. Moscow: A-Print, 2018: 28.

Fig.9: https://pastvu.com/p/166883

Fig.10: https://pastvu.com/p/152925

Fig.11: https://trolleway.medium.com/1964-%D0%B9-%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%B4-%D0%BA%D0% B0%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B2%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%BD%D1%8B%D0%B5%D1%84%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE-9-%D0%B8-10-%D0%BA%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%80%D1%82%D0% B0%D0%BB%D0%B0-%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2%D1%8B%D1%85-%D1%87%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%91 %D0%BC%D1%83%D1%88%D0%B5%D0%BA-18b157183968

Fig.12: https://strelkamag.com/ru/article/25-neochevidnykh-faktov-o-raionakh-moskvy

Fig.13: https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/9784-printsip-ekonomii-byl-opredelyayuschim

Fig.14: https://pastvu.com/p/824303

Fig.15: https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/9784-printsip-ekonomii-byl-opredelyayuschim

Fig.16: https://pastvu.com/p/1161091

Fig.17: https://tatlin.ru/articles/vremya_i_eksperimenty

Fig.18: https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/9784-printsip-ekonomii-byl-opredelyayuschim

Fig.19: Ibid.

Fig.20: https://eefb.org/retrospectives/urban-planning-as-a-shifting-symbol-in-soviet-and-post-soviet-cinema/

Fig.21: https://www.colta.ru/articles/art/9784-printsip-ekonomii-byl-opredelyayuschim