Mat cities

Mat concept in relation to the problem of size

AA / MArch 2022

Critical Urbanism

Supervisor: Lawrence Barth

Student: Anna Shpuntova

Introduction

Our, as an architectural discipline, constant preoccupation with size has deep roots and is complex in nature. This interest is multifaceted: any discussion on the topic of size inevitably dissolves in a series of other discourses. It involves questions of malleability, balance and repetition, identity, belonging, coherence, and the list can be continued much further. We are still searching for the correct relation between dimensions and opportunity to think in terms of a coherent whole, no matter if it is at the scale of a building or at a scale of the city. What is the ‘right’ attitude towards size: is it disruptive and inhuman or diversifying and a valuable tool? Such ‘pendulum swings’ are quite characteristic for the attitude towards size inside the field1. However, as with the majority of questions in architectural theory, there is no right answer to it and there are more than just two sides of the size ‘coin’. There are many concepts that emerged in this discourse, like ‘Megaform’, formulated by Kenneth Frampton, ‘Bigness’ brought in by Rem Koolhas, etc. This essay will research and elaborate on these ideas, as well as some of the key readings on the theory and implications of size in architecture and urbanism. It will then suggest a discussion of the mat buildings concept as a possible reading of a Megaform, trying to flesh out the possible affinities as well as differences between the two. Questions of representational qualities, scale, flexibility, growth, order will be in the heart of the research. What could the applications of the mat buildings theory be for our practice as architects and urbanists? The goal is not so much to give a final answer or to discover a magic ‘recipe’ but rather contribute to the debate on representational architecture, question of size and discover the opportunities that open up in the research of the ‘mat’ concept.

A large problem

One of the important starting points in the discourse is the ‘Superblock’ essay by Alan Colquhoun2 as it offers a conceptual history of our understanding of size. He begins from the structure of the ancient and Medieval Ages cities and moves through time towards the modernity. Colquhoun describes a general concern that emerged in the second half of the 20th century: our cities started to loose important qualities when the size was drawn into urban planning and architecture. Qualities like legibility, sense of purpose, continuity. The Medieval and Renaissance cities consisted of two parts, ‘undifferentiated mass of houses’ and buildings representing ‘mythos of collective life – social, political, and intellectual’3. In other words, only buildings that should have symbolic meaning to us, institutions of the public realm, were truly representational, distinctive. However, they were distinctive within a broader framework, which allowed to integrate all elements of the city. In contrast, according to Colquhoun, the modern city seems to consist mainly of ‘Superblocks’, large units which have no capacity for representing ideas. They disrupt the grain and system of the city fabric, its legibility. When everything is too big, nothing means much anymore. The author claims that of the main triggers for this problem is the accumulation of capital, which allows investors or companies to build up large parts of the city land. Rem Koolhas, although he sees Bigness4 as ‘a contemporary urban force’5 rather than a problem, notes the same tendency when talking about zoning. He claims that imposing a visually coherent system and controlling it, is not possible today anymore due to the scale of the global operations and the fact that economic incentives and needs are always prioritised6. Aldo Rossi, on the other hand, argues against Colquhoun’s point of view saying that blaming only size and growth in all metropolitan problems is ‘to ignore the actual structure of the city and its conditions of evolution’7

One can see arguments put forward by Kenneth Frampton in the ‘Megaform as Urban Landscape’ lecture as an indirect response to the Colquhoun ideas. He offered a new term, Megaform, to describe the potential of certain large forms found in the megalopolitan contexts. He saw them as a tool to actually restore the legibility of the city, rather than to disrupt it. From his point of view, It could be done by establishing a strong relation of the building to the urban landscape, ‘insinuating itself as a continuation of the surrounding topography’8. Megaform’s large size allows it to draw together multiple functions and articulate the richness and complexity of the city. Among its other key qualities according to Frampton, are also a strongly emphasised horizontality, inclination to densify the urban fabric

1 Lawrence Barth, from Critical Urbanism series of lectures. Housing and Urbanism March programme.

2 Alan Colquhoun, “Superblock”, in Essays in Architectural Criticism. Modern Architecture and Historical Change (Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press 1981), 83-104.

3 Ibid., 66.

4 Term introduced by Rem Koolhas in Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large

5 Rem Koolhas, Masao Miyoshi, “XL in Asia: A Dialogue between Rem Koolhaas and Masao Miyoshi”, Boundary 2, 24, no. 2 (1997), https://doi.org/10.2307/303761.

6 Ibid, 12.

7 Aldo Rossi, Architecture of the city (Cambridge, Mass.; London : MIT Press, 1982), 160.

8 Kenneth Frampton, Megaform as urban landscape (Mich. : University of Michigan, A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning, 1999), 20

and place-creating character9. Unlike Colquhoun, Frampton did not deny the megaforms an ability to establish identifiable spaces10 and contribute to the distinctiveness of the place character. If they have such strong topographical qualities, that are powerful enough to emulate the urban landscape, then what are they if not representational in nature. In general, Frampton by his theory of Megaform suggested to look closely at the qualities large buildings of megalopolis are offering, to use them as an answer to the problems recognised precisely in largeness itself.

The focus on the ground and topography in relation to the large framework of megaforms can be traced back to the theory of megastructure put forward by Maki in 1964. He compared megastructure (considerations about the differences in terminology coined by Frampton and himself put aside) to ‘the great hill on which Italian towns were built, a man-made feature of landscape’11. A rather obvious but not less important quality of the megaforms (megastructures / superblocks) is their ability to accommodate and concentrate within one spatial framework a variety of functions; liberating architecture from belonging to one actor and finding new ways to accommodate the collective12. This brings into play another dimension: dimension of time. Diversity of programme and actors generates the anticipatory nature of such buildings, making them future-proof and ready to change over time.

The positions described above are only a fraction of all arguments circulating around the question of size and its role in our cities. However, they start to show which important notions become of interest in relation to its problem (or virtue). For instance, issues like identity, extension and continuity, coherence, relation to the ground and landscape.

Mat-buildings – megaforms?

One of the strong concepts brought into the discipline discussion in the 1970s was one of a ‘mat’ building. As I will show further, many of its characteristics, like emphasis on the horizontal extension, densification of the fabric, strong topographical character, programmatic variation, clearly correspond with Frampton’s idea of a Megaform. However, I will also illustrate why we can’t exactly treat a mat building as a megaform and which aspects described by Frampton and Colquhoun are missing from the ‘mat’ idea. My aim is to understand which features of the both concepts could be helpful for us when we think about how we build our cities today. And to see if the two can coexist in the city without contradicting each other.

Opening the mat building topic, it is inevitable to mention the article by Alison Smithson published in Architectural Design in 197413. The British architect was the one to coin the ‘mat’ term itself. However, it was not used to describe one particular project. It was rather an attempt to give an overview of a collection of projects that all addressed similar concerns of the field and to outline their ‘genealogy’. One project did nevertheless dominate in a way the discussion in the article, at least served as a starting point for it — the Berlin Free University by Candilis-Josic-Woods. For Smithsons it revealed most clearly the characteristics of the mat-building concept. Nonetheless, the author stated from the very beginning that the ‘language’ of the mat was still in process of formation. She did not therefore describe any particular architectural qualities that would clearly distinguish this type of buildings, but did formulate the main idea behind, identifying ‘a common set of ambitions, not a family resemblance’14. These buildings ‘epitomise the anonymous collective, creating a framework that allows the individual to gain new freedoms of action through a new order, based in interconnection, close-knit patterns of association, and possibilities for growth, diminution and change’15. This directly corresponds with the general trajectory of architectural thought at the time, in particular with what was being addressed by the Team 10 group. As noted by Tom Avermaete, it would be risky to try to describe their legacy as a ‘unified whole’, to say they all promoted the same ideas and beliefs. But, certainly there was an overarching goal: to shift from the ‘tyranny’ of the functionalist doctrine to ‘a more comprehensive grasp of the social and cultural realities of the city’16. Human associations, question of personal identity and everyday practices were put in the heart of the practice.

Stan Allen, reflecting upon the article by Alison Smithson, identified more specifically the ‘architectural objectives’ of a mat building: ‘a shallow but dense section, activated by ramps and double-height voids; the unifying capacity of the large open roof; a site

9 Kenneth Frampton, “Urbanisation and Discontents: megaform and Sustainability”, in Aesthetics of Sustainable Architecture, edited by Sang Lee (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 201: 102.

10 Ibid.

11 Maki Fumihiko, “Investigations in collective form”, in Nurturing dreams : collected essays on architecture and the city, edited by Mark Mulligan (Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press, 2008): 8.

12 Christophe Van Gerrewey, OMA/Rem Koolhaas: a critical reader (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2019), 301.

13 Alison Smithson, “How to Recognise and Read Mat Building”, Architectural Design, no.9 (September 1974): 573-590.

14 Hashim Sarkis, Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival (p 15, Hashim Sarkis Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag): 15.

15 Smithson, How to Recognise and Read Mat Building, 573.

16 Max Risselada, Dirk van den Heuvel, Team 10, 1953-1981: in search of a utopia of the present (Rotterdam : NAi, 2005), 258.

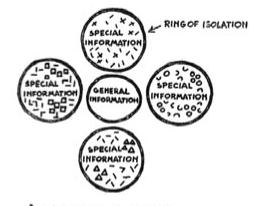

1 The idea of university: the need for and exchange of general and special information

6. The external expression of differences in function (are these as important as the similarities?) and nostalgia for representative form also tend to segregate the university into specialised disciplines only.

strategy that lets the city flow through the project; a delicate interplay of repetition and variation; the incorporation of time17 as an active variable in urban architecture’18. Allen drew a clear connection between Landscape urbanism and the mat buildings characteristics. The ‘thick 2D’ of a landscape means a dense section, strongly articulated horizontally, but still not flat as a simple surface. The same can be applied to the mat buildings: best seen in section which does not work as a primitive stack, but is complex and works together with the plan. Almost endless flexibility, openness for change and possibility for growth is also what is believed to be distinctive about the mat buildings. Whether via ‘the open-ended quality’ that allows the potential users to appropriate the building according to their wishes and needs; or via the ‘flexible cellular structure, a stem or web of connections’19 created in such projects.

2. The university is composed of individuals and grouos, working aloneor together, in different disciplines. When individuals work together they take on new characteristics and develop new ideas

7. We seek rather a system giving the minimum organisation necessary to an association of disciplines. The specific natures of different functions are accommodated within a general framework which expresses university

All of the features described above conform with the Megaform idea put forward by Frampton. However, one of the most important aspects of his theory is missing, that being the representational quality: ‘Mat building is anti figural, anti representational, and antimonumental. Its force is diagrammatic and organisational’20. One does not experience the special qualities of a mat building from the outside: it is instead in the system of its interiors, their complexity, programmatic richness, the way the environments within the building framework are intertwined. Here an important shift can be observed: from interest in the creation of a form to the content, quality of the environment. I will further use the example of the Berlin Free University to illustrate what exactly are the spatial and architectural means that allow to conduct this shift.

Berlin Free University

8 In skyscraper typebuildings disciplines tend to be segregated. the relationship from one floor to another is tenuous, almost fortuitous, passing through the space - machine - lift.

3. The university as it seems to be: Buildings contribute to the isolation of specific disciplines

I chose this project not because it is the best exemplar of the mat building concept (as it became already apparent, it is an ambiguous and complex term and there is no single description for it). It has even in a way become a cliche to talk about this particular case when discussing the mat buildings topic. However, it is still a vivid example, located in a way in the roots of the discussion and emergence of a mat concept. There are several key points in the way the university is organised. A grid of ‘primary and secondary’ pathways, or traces is used as a framework21. The relative hierarchy of the pathways depends on the anticipated speed of movement along them and the level of intimacy required by spaces they lead towards. Everything else inside this framework is ‘play of solids and voids’22. They comprise open courtyards of different sizes, communal plazas and gardens, classrooms, offices, communal spaces serving for all kinds of purposes. One of the main goals behind such organisation was ‘to create space for fluid association between disciplines’23. This tendency towards multidisciplinarity and exchange is related to the general shift in knowledge sphere in the 1960s. An emerging ideology at the time was in opposition to the old school system and claimed ‘that innovation never happens within the comfort zone of a single discipline but always on the divide among different domains’24.

Atomisation of the idea of university

4. But the removal of built barriers and the mixing of disciplines is not enough. The group is meaningless when there is no place for the individual

9. In a groundscaper organisation greater possibilities of community and exchange are present without necessarily sacrificing any tranquility.

It was not only about connections between the disciplines but also the proliferation of relationships between an individual and collective, one meaningless without another. There was a search of balance between the needs and interests of the two via architectural and spatial means. A diversity of spaces of different characteristics, vast and intimate, quiet and active, was meant to promote a diversity of the users’ experiences. What is important is the way all of these spaces were connected, not just variety in terms of their qualities. The transitions and circulation spaces were not just neutral links. Together links and ‘nodes’ of spaces formed a continuous fabric of internally

17 The notion of time also came through in the article by Alison Smithson. She wrote: ‘The systems will have more than the usual three dimensions. They will include a time dimension. The systems will be sufficiently flexible to permit growth and change within themselves throughout the course of their lives’. Smithson, How to Recognise and Read Mat Building, 580.

18 Stan Allen, “Mat Urbanism: The Thick 2-D”, in Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis (Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001): 121.

Group is everywhere

5. The relationship of group and individual must also be considered. Areas of activity and areas of tranquility must be provided. If the group is everywhere, there is no group because there is no individual.

19 Timothy Hyde, “How to Construct an Architectural Geneaology”, in Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis (Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001): 106.

20 Allen, Mat Urbanism, 122.

21 The use of a grid as a structuring device was criticised by the Woods’ colleague, Giancarlo who claimed that such pattern might negatively affect the process of eduction, interaction, their creative character. As an answer Woods said: ‘The intellectual grid is all in your head. But people (and pipes) need direct routes, instead of so much indeterminate art, in which building clearly should be the last part’. It is also interesting to see how 15 years later, Rem Koolhas in the Delirious New York described the Grid as an urban tool and in a way more robustly, but as serving for the same qualities that we can observe in the Berlin FU. ‘The Grid’s two-dimensional discipline also creates undreamt-of freedom for three-dimensional anarchy. The Grid defines a new balance between control and de-control in which the city can be at the same time ordered and fluid, a metropolis of rigid chaos’.

22 Hyde, How to Construct an Architectural Genealogy, 105

Places for individual — Places for group Tranquility and Activity Isolation and Exchange

through the space organisation; wish to shift from the 'nostalgia of representative forms'; attention to the relation between individual and collective.

23 Candilis-Josic-Woods, project explanatory diagram ‘Articulation of Public and Private Domains’.

24 Francesco Zuddas, “Pretentious equivalence. De Carlo, Woods and Mat-building”, FAmagazine, no. 34 (October-December 2015): 54, https://www.famagazine.it/index.php/famagazine/article/view/73/536

Pedestrian circulation paths. There are 4 main axis running parallel to each other, while the rest of the building is penetrated by a net of narrower paths.

4: The 'mat' and 'web' metaphors come through clear when at least two layers are combined. Here: layer of the circulation routes and layer of unbuilt spaces.

5: Top view on a plan where all layers came together: built,voids, circulation areas and functional spaces.

6: University sections reveal another type of complexity, in addition to the one found in plans. The building acts as continuation of the landscape and the simple stack of levels gives way to what can be called combinations of modeules.

differentiated space25. A shift of focus took place: the built was no longer dominant over the unbuilt, the void. Moreover, one even became more interested in the spaces between the built parts, the ‘interval’, than in the building parts themselves. This resonates with what Robert Venturi was writing about in the ‘Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture’. He argued against a simplistic attitude which rejects the complexity an ambiguity of space; which does not deal with its qualities’ nuance for the sake of purity and clarity of definitions. His ‘gentle manifesto’ invited the discipline to consider the ‘difficult whole’, which would include the elements with all their interrelationships and complexity of characteristics. In this context, Venturi also payed attention to the contrast between interior and exterior and how their interdependence could be rethought. What if we started incorporating the notion of intermediate spaces into the architecture, create extended thresholds in the progression from interior towards the outside? ‘The transition must be articulated by means of defined in-between places which induce simultaneous awareness of what is significant on either side. It provides the common ground where conflicting polarities can again become twin phenomena’26

Mat building contradiction

Alan Colquhoun in his aforementioned essay27 used the Rockefeller center project to demonstrate an exception to the negative tendency of size parcelling the city. He also called the project ‘a sort of microcosm of a city as a whole’28. This is an appealing metaphor that is used quite frequently in architectural practice and theory. One of its variations is the ‘university as a city’ analogy that became popular in the 1960s and symbolised a changing attitude towards university as a place where new planning ideas and urban concepts could be tested29. The authors of the FU Berlin also claimed that their project was a possibility to create a ‘little city’. While the Rockefeller center is most clearly a separate building, set within a defined boundary, there is an ambiguity in the way we can perceive the Berlin Free University. Candilis-Josic-Woods considered the mat (or the web in their terminology) ‘not as a language of a recognisable form’30, but as a way to shape the environment of the city, become part of the ‘urban tissue’. Perhaps the quote that best describes this attitude is: ‘They [mats] are not the sum of length, height and largeness but rather a two-dimensional dense fabric, where men walk and live in’31. One can argue, whether the FU Berlin actually demonstrates such approach. The building diagram is restricted by a clear border. The notions of flexibility, change and growth, so important are read in the interior organisation rather than in the exterior form. Thus, this project ‘endures in its status of a finite building’ never mind how large it is and how complex is its internal organisation32 There is a certain tension here, out of which arises a question concerning the ‘mat’ idea in general. At which scale should we recognise a mat building? At a scale of a building or at the urban scale? Should we see it as an object or rather as a process? Or, as Timothy Hyde put it: ‘a verb or a noun’? In other words, it can on one hand serve as a finished model in its own right, with distinctive qualities set within a specific context. On the other hand, we can see it as a tool of urban transformation. Several authors gave specific answers to this issue. Eric Mumford in his article ‘The Emergence of Mat or Field Buildings’ mentioned that the mat buildings strength was in shift towards provisional organisation of fields of urban activity instead of shape-making33. Similarly, Stan Allen claimed that the qualities characteristic of a mat building are ‘most effectively put in play within an urbanist assemblage’34

Mat cities

I believe that this is precisely how we should look at the mat building idea today: in terms of its potential as a process of urban transformation35. But I would argue against what Candilis-Josic-Woods proposed. The idea that the city should shift from a ‘collection of separate buildings’ to the ‘urban as mats’ model. It is quite a radical suggestion if one imagines our whole cities in form of interwoven mats

25 Allen, Mat Urbanism, 122.

26 Aldo van Eyck, cited in R. Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (London : Architectural Press, 1977): 82.

27 Colquhoun, Superblock.

28 Ibid., 70.

29 Zuddas, Pretentious equivalence

30 Tom Avermaete, Another modern : the post-war architecture and urbanism of Candilis-Josic-Woods (Rotterdam : NAi Publishers, 2005): 330.

31 Ibid., 319.

32 Zuddas, Pretentious equivalence, 50.

33 Eric Mumford, “The Emergence of Mat or Field Buildings”, in Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis (Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001), 64.

34 Allen, Mat Urbanism, 126.

35 In the modern practice there are examples which would traditionally be ascribed to the ‘mat buildings’ category. A number of such buildings has been designed by the SANAA office. For example, De Kunstlinie Theatre, or the Rolex learning center. However, they still rather represent defined objects than work hard for integration into the urban fabric.

8: A space that can illustrate the notion of layering that is characteristic of a mat building'. One is moving through the building, but at the sane time can observe the courtyard or go outside; in addition to that, other parts of the building are visible from here,sometimes one cam even peek inside them.

9: Outdoor spaces are working harder than just pieces of landscape to look at or to walk through. They have a feeling of

10: All elevats of the University look approximately the same, designed according to the same modular system. it is hard to say of any of the entrances is the main one.

which comprise all spheres of our lives. Let us design buildings that are representational and are looking to acquire a status of a metaphor. But we might also think of building parts of our cities according to the mat principles next to those buildings36. By reconsidering the open under-utilised ground and making it work much harder, when the void and unbuilt spaces start to support the built. There is no need to choose between the two approaches. It might be useful here to learn from Colin Rowe who argued against polarisation of attitudes in understanding and planning of cities37. He invited to think about the city as a never complete instance and consisting of pieces that can be ambiguous to one another. Hence, we should look for ways to accommodate distinctive qualities and integrate them within a larger whole, a compilation of differences. ‘The situation to be hoped for should be recognised as one in which both buildings and spaces exist in an equity of sustained debate.<…> a type of solid-void dialectic which might allow for the joint existence of the overly planned and the genuinely unplanned, of the set-piece and the accident, of the public and the private, of the state and the individual’38 There are several reasons which allow us to think that the mat ‘principles’ could be useful today. They derive from the trends that we see emerging in the background of the discourse about architecture and urbanism. Relying less and less on the transport infrastructure, we are looking for new versions of pedestrian-oriented environments. For settings which tend not to rely heavily on the streets anymore. Walking along a continuous frontage addressing the street is substituted for the process of moving in depth, extending the experience of entry, whether it is entering a building or a block. We recognise the importance of the action of moving through a layered space. This is exactly what a mat building idea potentially offers for organisation of neighbourhoods or larger urban areas. Sequences of interconnected spaces of different qualities that draw things to each other and create wider networking opportunities. Of course, what this implies, and what is characteristic of a mat building organisation, is that the importance of frontality and external hierarchy is diminished. Neither of its elevations are usually assigned a special role, given a priority over the others. But the question is if in such environments the notion of frontality is that important. In my view, waiving its principle is compensated by creating what Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky called a ‘phenomenal transparency’39. A tool that enables us to think that any moment in space belongs to more than one spatial system, to different groupings and scales.

Another tendency is that we are placing more emphasis on the possibilities for individuals and collective to collaborate and promote associational practices. In addition to such collaboration, we look for possibilities to both proliferate individual freedom and cultivate sense of belonging within a wider collective. There are several ‘mat’ qualities that work for these aspirations. Firstly, it offers a vast variety of spaces, all of which can provide environment for a different number of people. This flexibility and range help to promote association and interaction across scales. Just like in the FU Berlin, where the architects wanted to have spaces for everyone — for different group sizes as well as for individuals, it can work in any building of any genre.

In addition, the importance that we assign to the landscape is growing. It becomes a tool of articulating not only the relationships between the buildings but the life inside the buildings as well. The landscape can act as very high-performance area which does not only serve for circulation. The mat building concept strongly emphasises the landscape and articulation of the ground in the understanding of an urban form. It rethinks the role of traditional elements like courtyards in a new way. For example, in the Berlin FU case the landscape voids became important areas for the life of the university. They were spaces of encounter, information and knowledge exchange, serving exactly for the disciplines crossover which the architects aspired for40. I would argue that It was made possible because of how tightly all interior and open spaces were knit together into a coherent system. Another aspect of the ‘mat’ idea potential is that its structure and organisation are useful for multifunctional environments and for coexistence of multiple stakeholders. Clearly, programmatic variation is something we find today even more often than single-genre buildings and is not a new concept. Nevertheless, the growth of knowledge economy, changing patterns of work and life in general mean that we are looking to innovate further and bring together areas and genres that didn’t work together before. For instance, we question how the health, education, culture services could be integrated with the housing in order to see it more as an urban notion. The mat concept suggests a way of accommodating such crossovers as an alternative to typologies which create complexity through stacking the environments vertically. It works with another type of section that is much more interested in an interphase with the ground, offers more flexibility in combinations of its modules within.

36 Perhaps another ‘branch’ of conversation could evolve from here: about the iconic buildings and their status. Are all buildings that symbols/metaphors in their own right, iconic? How is this connected to the question of representational qualities? It seems that today the whole idea of ‘iconic’ got warped in a way: one starts to build with a wish to create an iconic building from the very beginning. Where is place to the notion of civic value in this debate?

37 Colin Rowe, Collage city (London : MIT Press, 1978).

38 Rowe, Collage city, 83.

39 Colin Rowe, Robert Slutzky, Transparency (Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1997).

40 There is an opinion expressed by Florian Heilmeyer in his article about the FU Berlin that there was another factor that contributed to the popularity of the exterior spaces like gardens and courtyards. The interior spaces were not that comfortable and either too cold or too hot, therefore the students and the staff preferred to spend time outside. However, I would not lessen the role of the spatial organisation in this question. Florian Heilmeyer, “The Radically Modular Free University of Berlin”, Uncube, July 15, 2015, https://www.uncubemagazine. com/blog/15799747.

Conclusion

The research that preceded this work confirmed what I believe is one of the main qualities of the architecture theory in generalThere are no simple answers or unambiguous definitions in it. The size and ‘mat’ concepts are no exception. As I stated in the beginning, the goal of this essay was not to bound these notions to short descriptions or to form an opinion on whether they are simply useful or destructive for our practice. What I think is important about the 'mat' concept is that it suggests to shift our focus towards the value of the buildings and places in relation to their qualities rather than on their representational character. The way that buildings organise our experiences, practices alone and within groups, the way we associate around everyday routine are more important than their statements as iconic objects. We have many examples of projects which offer strong representational qualities that can be experienced from the interior and the ‘mat’ concept contributes to this range. Naturally, we expect the buildings in our cities to deliver more and more every day, to work harder, to articulate the urban fabric. But instead of putting pressure on the way they look, we should probably put this effort in how they work. Again, as I already claimed, it does not mean that the idea of ‘mat’ should should become our only tool as urbanists and architects, but it does start an interesting discussion.

Bibliography:

Allen, Stan. “Mat Urbanism: The Thick 2-D”. In Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis, 118-127. Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001.

Avermaete, Tom. Another modern : the post-war architecture and urbanism of Candilis-Josic-Woods. Rotterdam : NAi Publishers, 2005.

Banham, Reyner. Age of the masters : a personal view of modern architecture. London: Architectural Press, 1975.

Calabuig, Debora Domingo, Raul Castellanos Gomez, Ana Abalos Ramos. “The Strategies of Mat-building”. The Architectural Review, August 13, 2013. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/the-strategies-of-mat-building.

Colquhoun, Alan. “Superblock”. In Essays in Architectural Criticism. Modern Architecture and Historical Change. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press (1981): 83-104.

Fabrizi, Mariabruna. "The Free University of Berlin (Candilis, Josic, Woods and Schiedhelm - 1963)”. Socks, October 29, 2015. https://socks-studio.com/2015/10/29/the-free-university-of-berlin-candilis-josic-woods-and-schiedhelm-1963/.

Frampton, Kenneth. Megaform as urban landscape. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan, A. Alfred Taubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning, 1999.

Frampton, Kenneth. Modern Architecture : A Critical History. London: Thames and Hudson, 1980.

Frampton, Kenneth. “Seven points for the millennium: an untimely manifesto”. The Journal of Architecture 5:1 (2000): 21-33. 10.1080/136023600373664.

Frampton, Kenneth, “Urbanisation and Discontents: megaform and Sustainability”. In Aesthetics of Sustainable Architecture, edited by Sang Lee, 97-109. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2011.

Fumihiko, Maki. “Investigations in collective form”. In Nurturing dreams : collected essays on architecture and the city, edited by Mark Mulligan, 44-68. Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press, 2008.

Heilmeyer, Florian. “The Radically Modular Free University of Berlin”. Uncube, July 15, 2015. https://www.uncubemagazine. com/blog/15799747.

Hyde, Timothy. “How to Construct an Architectural Geneaology”. In Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis, 104–17. Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001.

Koolhas, Rem. Delirious New York : a retroactive manifesto for Manhattan. Rotterdam : OIO Publishers, 1994.

Koolhaas, Rem, Masao Miyoshi. “XL in Asia: A Dialogue between Rem Koolhaas and Masao Miyoshi.” Boundary 2 24, no. 2 (1997): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/303761.

Koolhas, Rem. S, M, L, XL : small, medium, large, extra-large; Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau, edited by Jennifer Sigler. Koln : Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1997.

Krunic, Dina. “The ‘Groundscraper’: Candilis-Josic-Woods and the Free University Building in Berlin, 1963–1973.” Arris 23, no. 1 (2012): 28–47. doi:10.1353/ARR.2012.0002.

Mumford, Eric. “The Emergence of Mat or Field Buildings”. In Le Corbusier’s Venice Hospital and the Mat Building Revival, edited by Hashim Sarkis, 48–65. Munich London New York: Prestel Verlag, 2001.

Risselada, Max, Dirk van den Heuvel. Team 10, 1953-1981 : in search of a utopia of the present. Rotterdam : NAi, 2005.

Rossi, Aldo. Architecture of the city. Cambridge, Mass.; London : MIT Press, 1982.

Rowe, Colin. Collage city. London : MIT Press, 1978.

Rowe, Colin, Robert Slutzky. Transparency. Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1997.

Smithson, Alison. ‘How to Recognise and Read Mat Building’. Architectural Design, no. 9 (September 1974): 573–90.

Speaks, Michael, Gerard Hadders, Crimson. Mart Stam's trousers. Rotterdam : 010 Publishers, 1999.

Taut, Bruno. “The city crown”. In Metropolis Berlin, 268-273. Berkeley : University of California Press, 2012.

Teyssot, Georges. Aldo Van Eyck and the rise of an ethnographic paradigm in the 1960s. Editorial do Departamento de Arquitetura, 2011.

Van Gerrewey, Christophe. OMA/Rem Koolhaas: a critical reader. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2019.

Venturi, Robert. Complexity and contradiction in architecture. London : Architectural Press, 1977.

Zuddas, Francesco. “Pretentious equivalence. De Carlo, Woods and Mat-building”. FAmagazine, no. 34 (October-December 2015), https://www.famagazine.it/index.php/famagazine/article/view/73/536.

Table of figures:

Fig.1: https://socks-studio.com/2015/10/29/the-free-university-of-berlin-candilis-josic-woods-and-schiedhelm-1963/.

Fig.2: By author.

Fig.3: By author.

Fig.4: https://socks-studio.com/2015/10/29/the-free-university-of-berlin-candilis-josic-woods-and-schiedhelm-1963/.

Fig.5: https://socks-studio.com/2015/10/29/the-free-university-of-berlin-candilis-josic-woods-and-schiedhelm-1963/.

Fig.6: By author.

Fig.7: https://www.uncubemagazine.com/blog/15799747.

Fig.8: https://www.uncubemagazine.com/blog/15799747.

Fig.9: https://www.uncubemagazine.com/blog/15799747.

Fig.10: https://www.uncubemagazine.com/blog/15799747.