CARE-FULL NEIGHBOURHOODS

From care Venue to care Ecology

Exploring potential of inner-peripheral landscapes

Anna Shpuntova

Exploring potential of inner-peripheral landscapes

Anna Shpuntova

Exploring potential of inner-peripheral landscapes

Anna ShpuntovaExploring potential of inner-peripheral landscapes

From care Venue to care Ecology

Exploring potential of inner-peripheral landscapes

Architectural Association School of Architecture

MArch Housing and Urbanism 2021-2023

Postgraduate Programme

Tutors: Anna Shapiro & Lawrence Barth

London 2023

Architectural Association School of Architecture

Postgraduate Programme

Coversheet for Submission 2021-23

Programme: Housing and Urbanism

Student Name: Anna Shpuntova

Dissertation Title: Care-full neighborhoods. From care venue to care ecology.

Declaration:

‘I hereby certify that this piece of work is entirely my own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.’

Signature of Student: Anna Shpuntova

Date: 13.01.2023

I would like to thank everyone who supported me through this important and exciting journey.

To my parents who always support me in chasing my dreams and who taught me that anything is possible.

To my sister who made London feel like home and who is forever my role model.

To Denis, my best friend and partner. I could never do this without your love and support.

Anna, thank you for your love for architecture, your endless patience and devotion, for always pushing me further and helping me to find my way.

Lawrence, thank you for being an incredible Teacher, for making me challenge myself and be critical, and for showing the amazing world of architectural thought.

Irénée, thank you for the most beautiful lectures and for your dedication. It was a pleasure to be your student.

Steve, Elena, Francesco, thank you for inspiring conversations and for your guidance.

My dear H&U family, Sarah, Eduardo, Sami, Rashida, Dilara: thank you or being you and sharing with me all parts of this experience, and for giving me a chance to learn something from each one of you.

‘Care is a surprisingly short word, considering the whole cosmos of professions, sciences and demographics that are included in a holistic understanding of it’.1

The interest in the very science of who we are as subjects of health has allowed us to generate over the last decades the widest system of therapies, services and environments associated with health, well-being and lifestyle

[1-4] (e.g serviced and assisted living, nutritional, lifestyle and genetic therapies, pharmacological and sport facilities, etc.). The more these proliferate, the more possible interpretations one can give to the notion of care and the more various locations for these services one sees emerging in our cities. Broadening and interlacing of care services allows us as individuals to take personal responsibility for shaping our own care environments and including them into our changing lifestyle patterns.

These changes coincide with the shift in the attitude to our living environments and general interest in more collective ways of living where balanced sharing of resources, services and responsibilities is something we desire, whether as families, individuals, retirees or young professionals. The offer of well-being and healthcare embedded into our housing environments is the tool that would allow us to start consolidating our thinking about care into thinking about the urban value it offers.

We would claim that today we are not treating the networked distribution of care services in a strategic way that would allow to bring benefit to development of our cities. If we shift from understanding designing for care as an architectural question at a scale of a single venue and its immediate context to care as an ecology that drives the urban change, we will discover the potential of care

environments to reinvent our neighbourhoods and their vocation. This means recognising the spatial complexity of such care ecologies as well as diversity of urban settings where they can thrive and boost change. A care ecology as opposed to a care venue suggests a system that allows actors and stakeholders of different scale and vocation to see the relevance of working in a jointup way or contributing to a bigger network, managing the resources and land together. A network where the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts, which is flexible enough however to become an alternative to rigidness of masterplanning approach.

We are therefore going to investigate a morphological and typological framework that would allow us to broaden our understanding of care to questions of well-being services, vocational learning, food and event oriented environments, intergenerational knowledge exchange, sports, and various versions of living. We will also investigate how ecology of care creates crossovers with our domestic realm and in what way it changes the way we prefer to live today.

1 Paola Roca, “Care-scapes. Campus - a medium for integrated living”, in Eudamonia (London: Architectural Association, 2019): 66.

While it is not to argue that today the industry of health and well-being is a growing sector that receives a lot of investment, we are not fully benefiting from in terms of the urban value for our cities. Policies like ‘The London Plan’ or ‘Housing design Quality and Standards’ developed by the London authorities do give us guidance on how and where the environments of care should be built. This guidance most often does not look at care provision beyond the logistics of care delivery, or technical requirements for spatial elements, such as the width of the doors, noise cancellation parameters, etc. The healthcare system in the UK is structured in a way that leaves major stakeholders like the NHS on the periphery to the actual process of care provision as it is delivered by specific care providers at the bottom of the system. This also contributes to the inability of the city to take full advantage of the care environments and address them holistically.

Traditionally, the picture of the old age that exits in our society is a very uniform one. However, with greater age people become less and less alike. ‘In fact, senior citizens are an extremely heterogeneous group. In addition to their different educational, social, cultural and political identities, which remain unchanged, their financial situations vary.’2 In addition to that, in a late-living society that we are people are staying active and productive much longer and we are often underestimating the range of activities and services they require to lead full and productive life. Together with the understanding that ownership is not necessarily an answer today, this leads to a growing interest in BTR models3 and all forms of collective living. Such models are built around an idea of bringing with them an additional offer of infrastructure that can start to cater for the area around them. These models are particularly attractive for those who are willing to downsize

their households (e.g with greater age), are not ready to give up on services and amenities that belong to the central city living. They give people a chance to have access to health and well-being offer that they wouldn’t afford as a family or an individual in contrast to managing it collectively.

In the background of these trends, there is an ambition on the part of the NHS to establish a fully integrated community-based health care4. There is an investment into systems of health and well-being that would create crossover with our living environments. Finally, as hospitals become more and more specialised, more and more care services get outsourced, and there is a growing pressure on the care staff as they need to have a wider set of skills and be well trained. Hence, there is a growing understanding among care providers that they not only need to recruit talent but also to retain it. This becomes possible when environments of care come together with educational institutions, hospitals, and other stakeholders that bring with them opportunities for additional training, practice and education.

Altogether, the described trends give us the reason to believe that care models have a tremendous potential in terms of infrastructure and offer they can bring with them to local neighbourhoods and start spreading them on wider urban areas.[5]

4 ‘The long-term plan’ publication by the NHS, https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/).

Drivers of change. Redefining care as an urban question.2 Andreas Huber, “A Domicile in Old Age – Aspirations and Reality”, in Best of DETAIL: Urbanes Wohnen/Urban Housing (Munchen, 2017): 73. 3 Built to Rent models

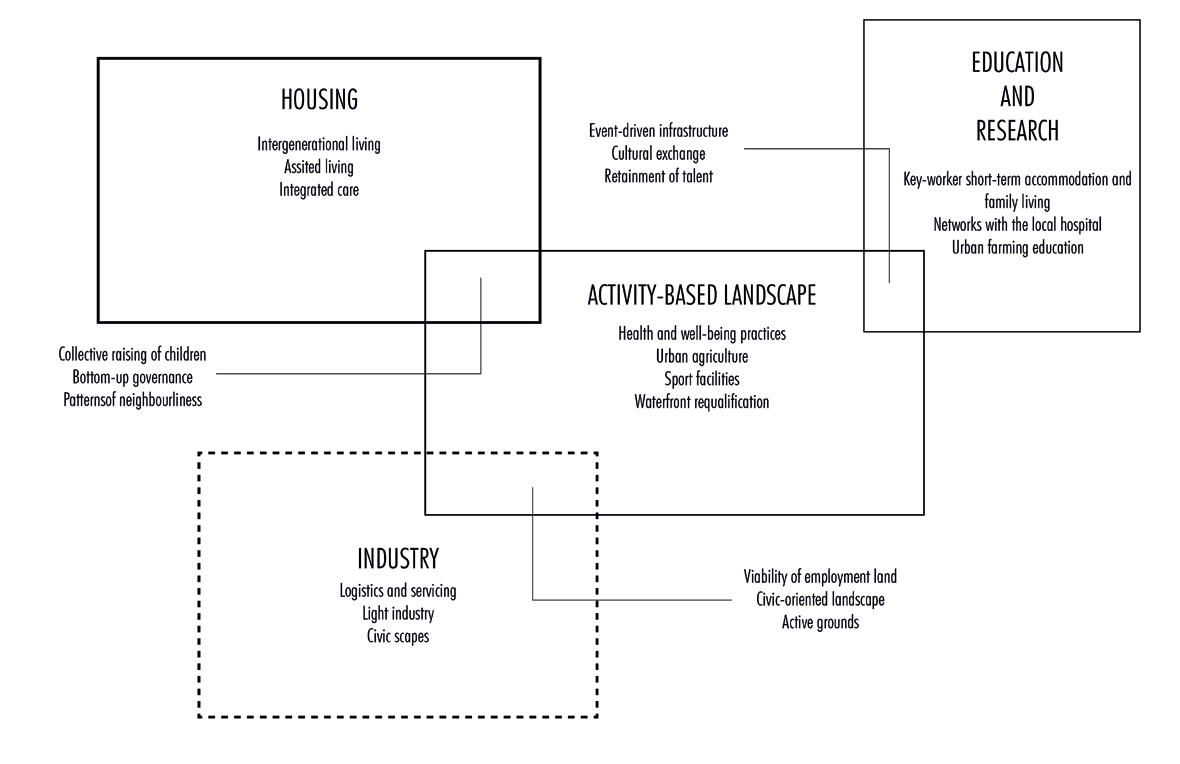

The described drivers of change allow us to put forward a speculative crossover between the elements of a care ecology, housing, and a new version of an activity-based landscape driven by health and well-being. Leading to creation of new network systems between local stakeholders, wider urban area, and larger actors at the federal level.

There is a type of areas that we often consider appropriate for care environments like nursing homes, homes for elderly, assisted living, etc. These areas are often characterised by amazing landscape, access to water and relatively quiet and calm settings in general. However, this also means that such care venues usually end up in isolation from the central city environments as desire for privacy, quietness and a certain level of security seem to be dominant considerations in their design process. If we agree to look at the potential of care ecologies in their urban value and their ability to rethink our neighbourhoods, then the first step would be to consider areas in our cities that are well-connected to the central city environments but still offer the qualities we value so much in relation to care. In this case, we would suggest to shift our attention to the inner periphery of the city, which offers fabric that is free from the ‘straitjacket of identity’1 that we inevitably face when working in the central city environments.

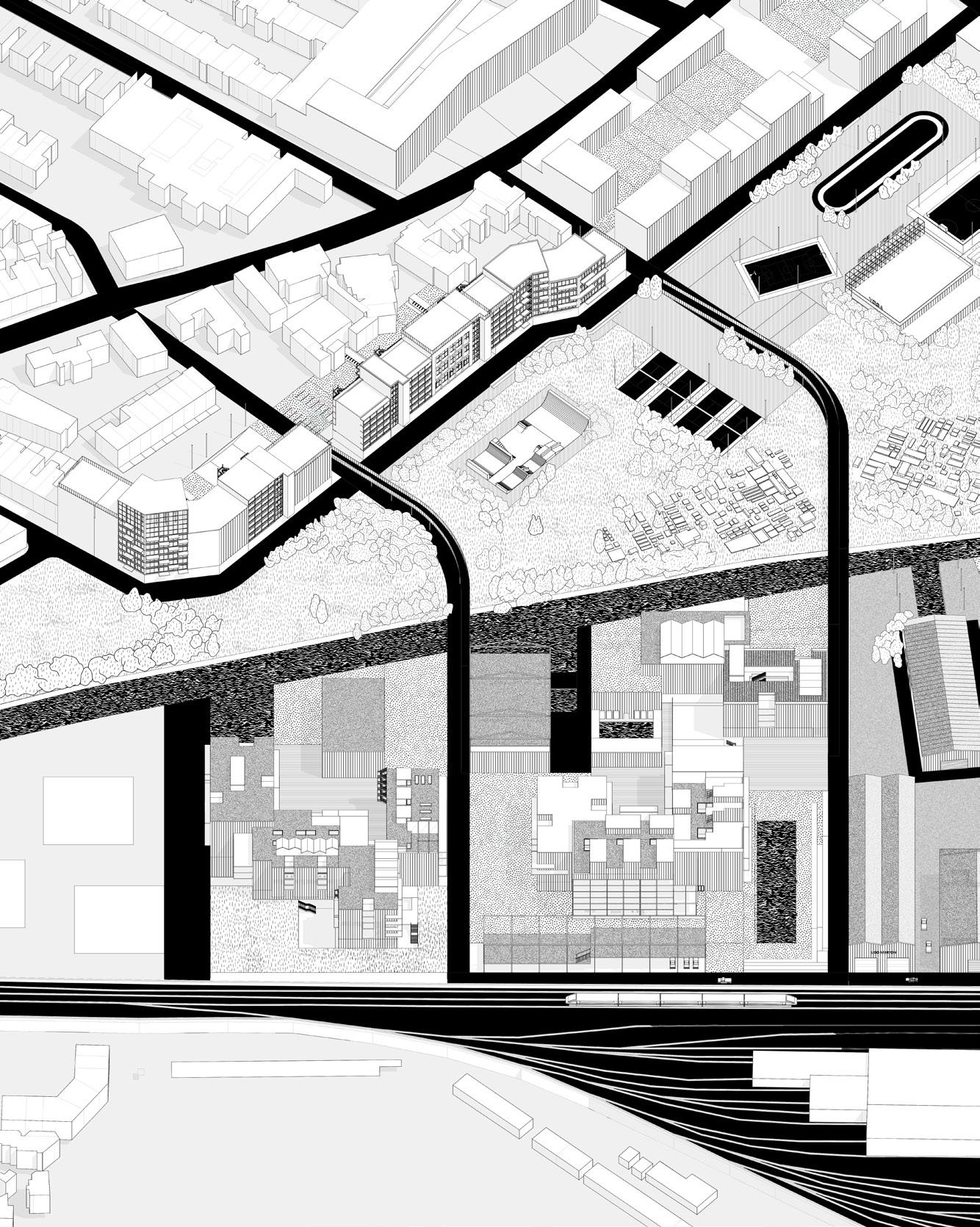

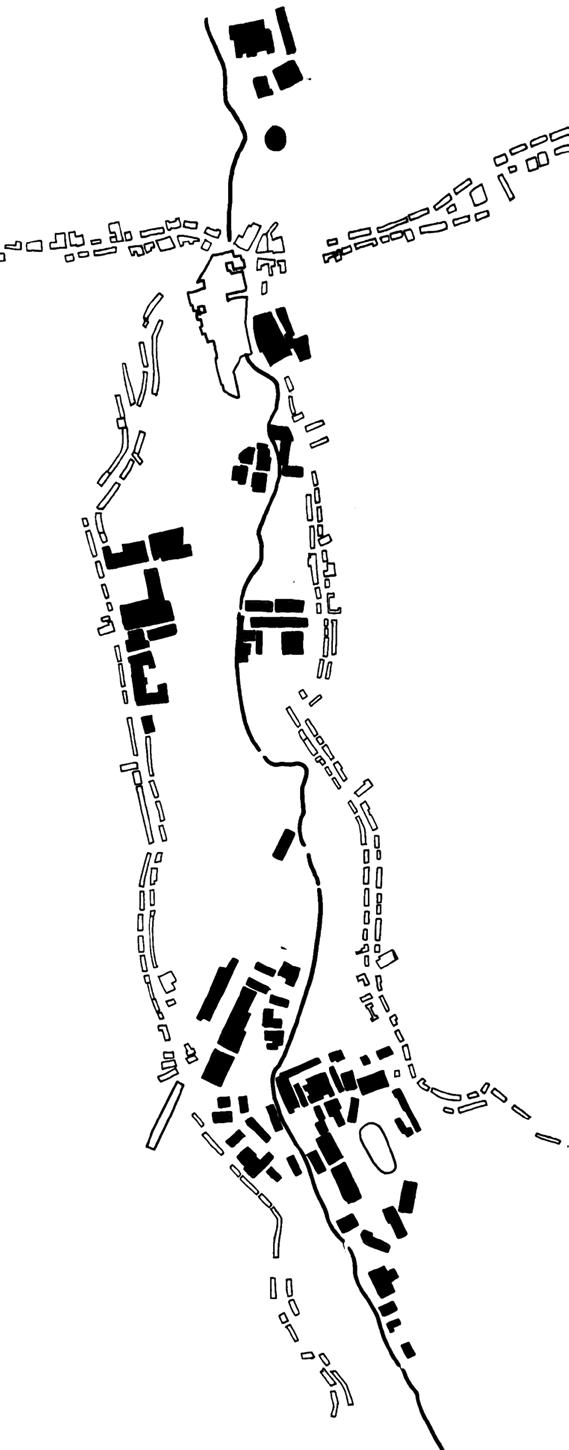

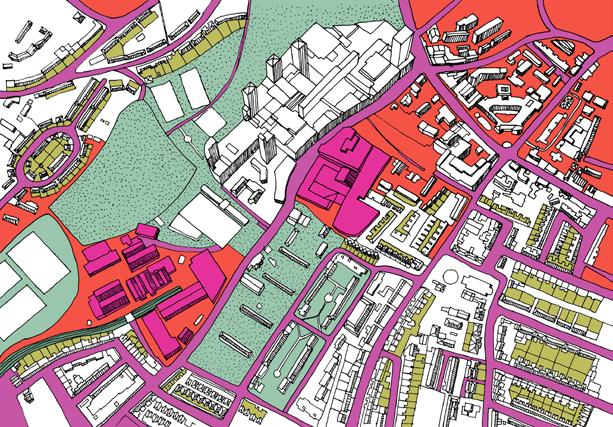

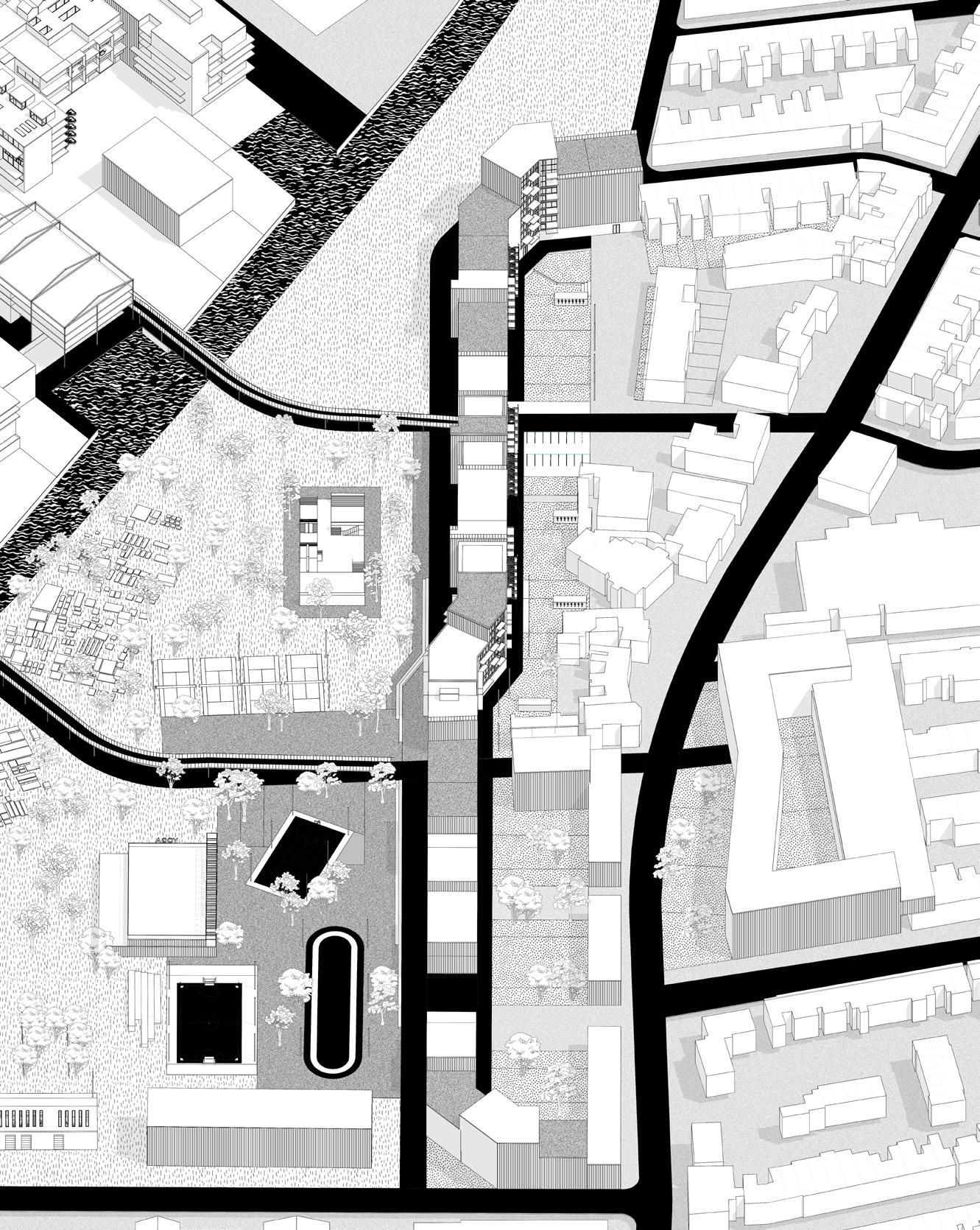

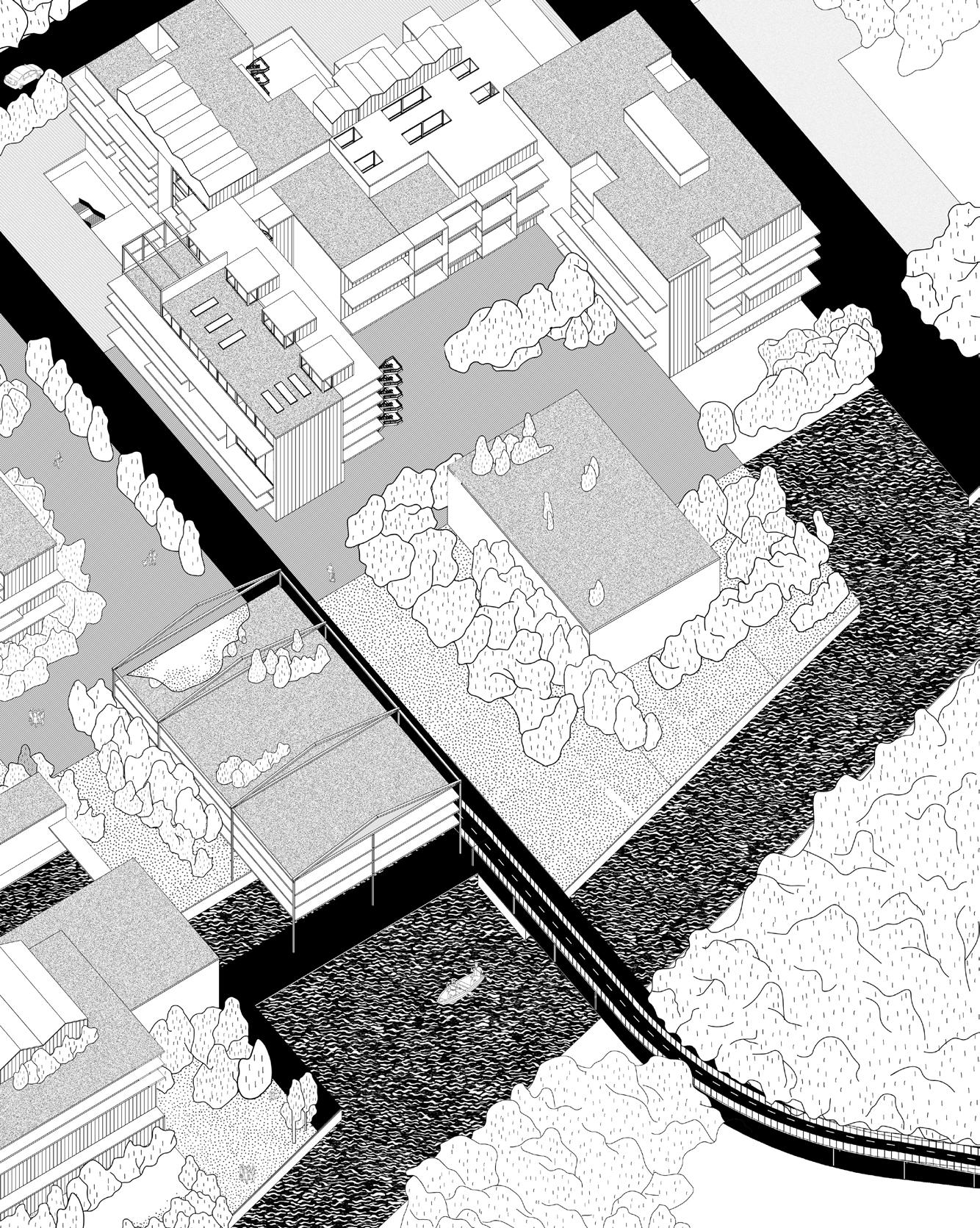

One of the corridors that starts offering this is the inner-peripheral area on the South bank of London, located along the river Wandle, stretching from the borough of Wandsworth in the North to Croydon in the South [6]. Exceptionally well located in relation to the inner city, the Wandle river trail2 offers access to landscape that is almost rural in character, vast open green areas

and clean water that supports biodiversity of the area. However, as well as many other areas in London that are located along the significant water routes, Wandle river is still dominated by the industrial hubs, storage and service centres which represent the ‘furious industrial activity’ of its past3

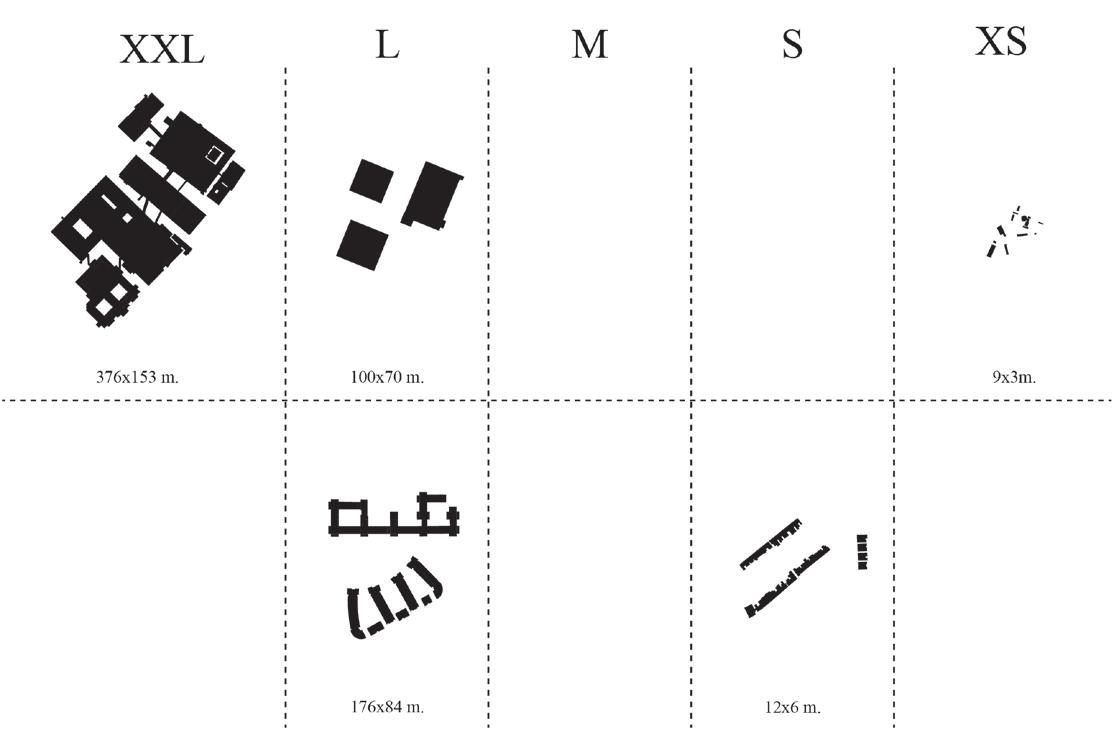

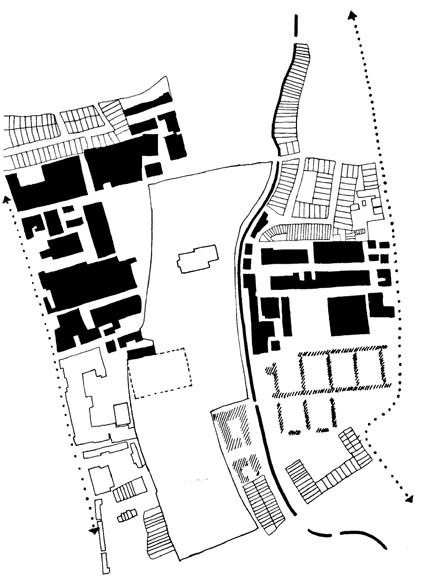

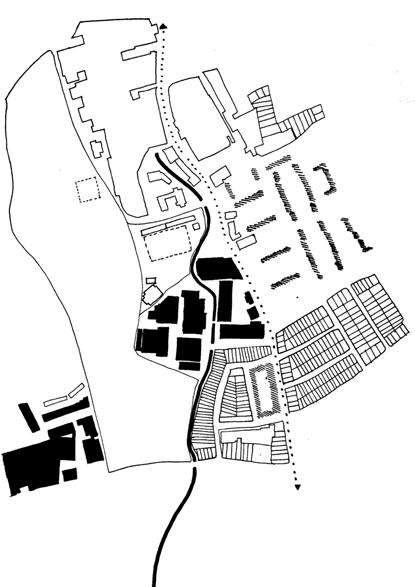

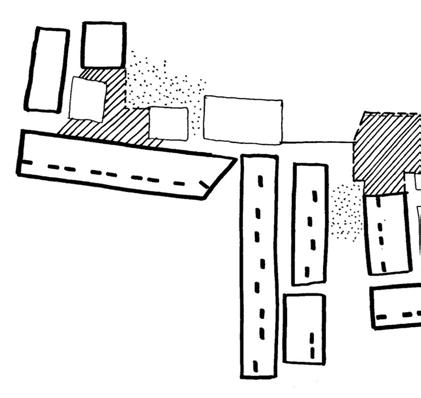

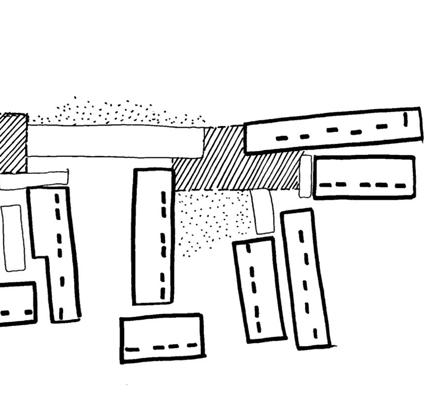

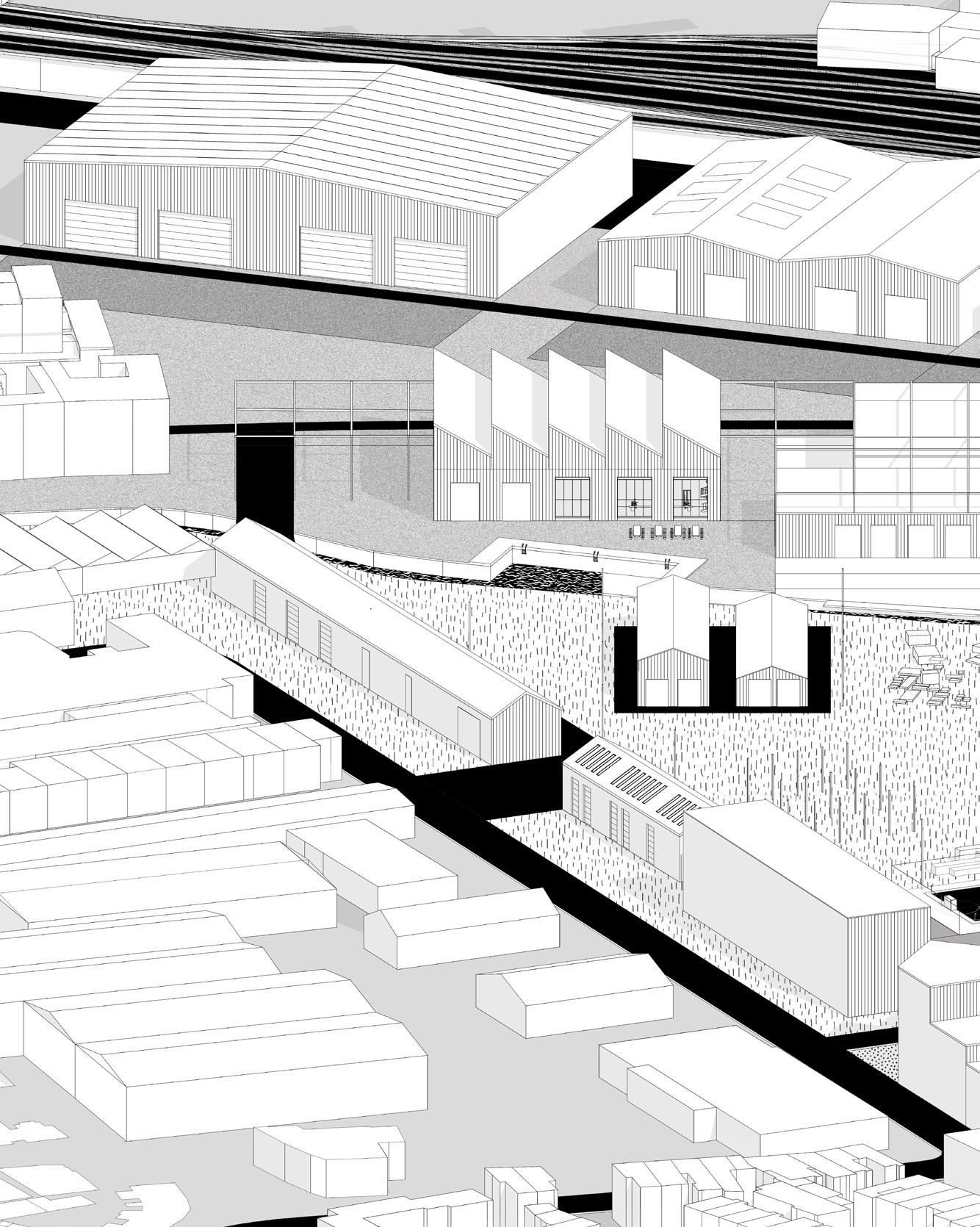

There is a distinctive transition in terms of the development models and type of settings that can be identified along the Wandle, as one moves from the Thames waterfront towards the southern end of the corridor4. Not in the last place due to the improved transport links over the last years5, the waterfront is considered an area of opportunity and high market value, and begins to be dominated by commercially oriented developments and regeneration schemes6 emerging around district centres. The fabric further to the South constitutes a combination of the ‘London vernacular’ villages – endless strips of terraced housing, under-performing high-street environments, and large scale post-industrial hubs. [7-12] Juxtapositions of scale are found between extra-small of the terraced houses and minor industrial structures to the extra-large storage and service sheds, with the medium scale of the built fabric missing from the bigger picture. [13]

1 Rem Koolhas, “The Generic city”, in B. Mau and OMA. S,M,L,XL (New York: The Monicelli Press, 1995): 1248-1264.

2 The Wandle Trail is a 12.5-mile walking and cycling trail that follows the River Wandle from Croydon to Wandsworth.

3 Tom Bolton in the ‘London’s lost rivers’ describes a walk along the Wandle as ‘unfurling a hidden history, of a rural past and of furious industrial activity’.

4 Similar conditions can be observed in other parts of the London inner periphery, for example in the Vauxhall-Battersea stretch.

5 Moreover, there is the Crossrail 2 system coming in the area in the nearest future.

6 Projects like the Ram Quarter in Wandsworth.

Thames

Wandsworth

Merton

Wimbledon

Thames

Wandsworth

Merton

Wimbledon

The most ‘trivial’ medium scale is missing from the built fabric, and the new project can play a mediating role in filling the gap.

Both the post-industrial and the nature landscapes in the area are at the moment under-utilised. The patterns of land ownership and plots dimensions and borders are historically challenging in the area. In combination with a lack of common framework and vision for change it results in independent developments that happen regardless of their impact on the future of the neighbourhoods and are unable to create benefits for a wider urban area

Today, the Wandle corridor is considered a very attractive area for young families and people with kids. It is possible due to the layered infrastructure of the schools, kindergartens, nurseries, sport facilities, and different versions of child care found in the area. In addition to that,it also is the place for St. George’s Hospital, one of the largest hospitals and educational/research institutions not only in South London but in the whole city.

The question is: are we doing enough in order to benefit from the phenomenal stretch along the river Wandle, all the layered infrastructure it offers, its landscape resources and heterogeneous morphology? We would claim that, in words of Duplex architects this heterogeneity ‘has a potential of transforming the direct juxtaposition into a high-contrast coexistence’5. A new version of care ecology could be fundamental to transformation in this area but is unthinkable today in the context of the kinds of care environments that we are traditionally facing in health and well-being.

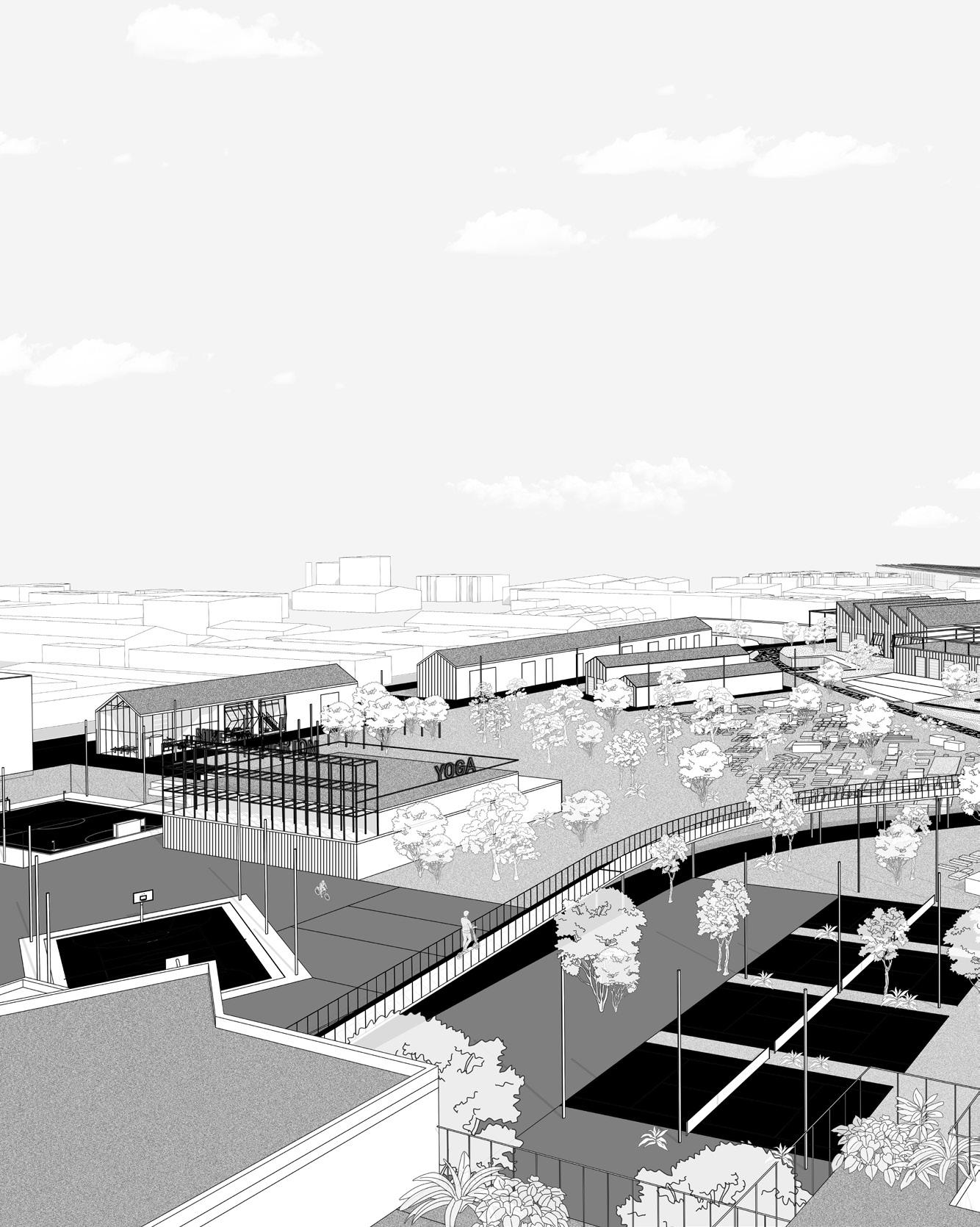

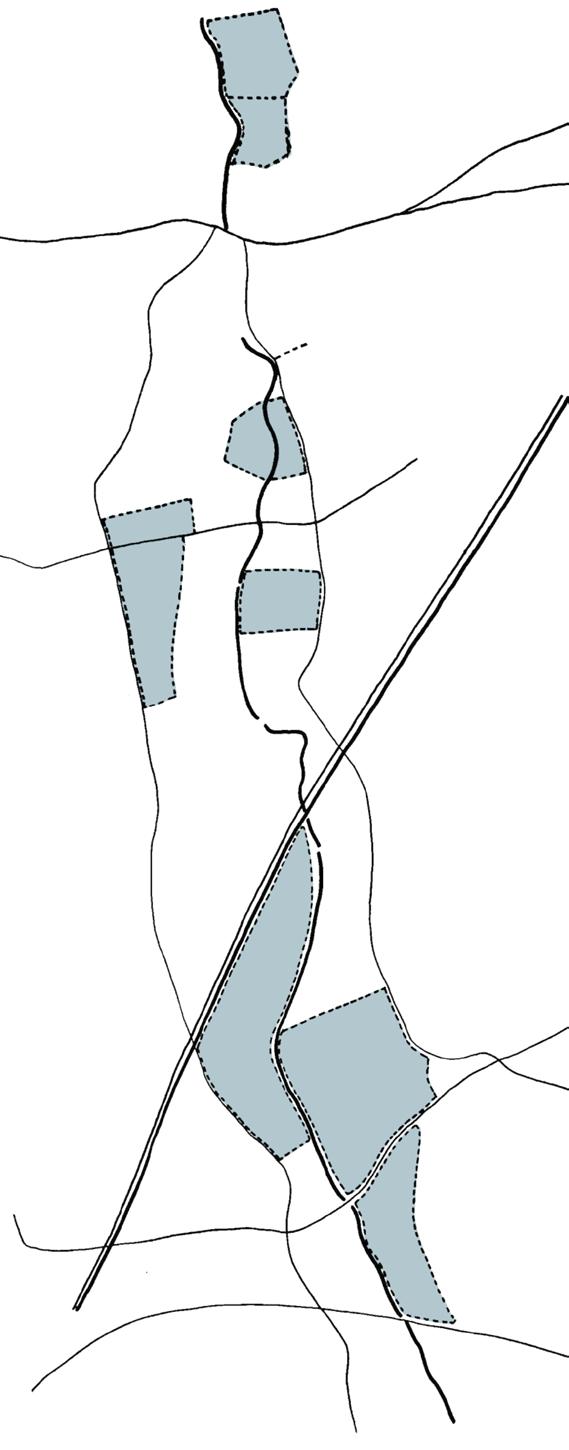

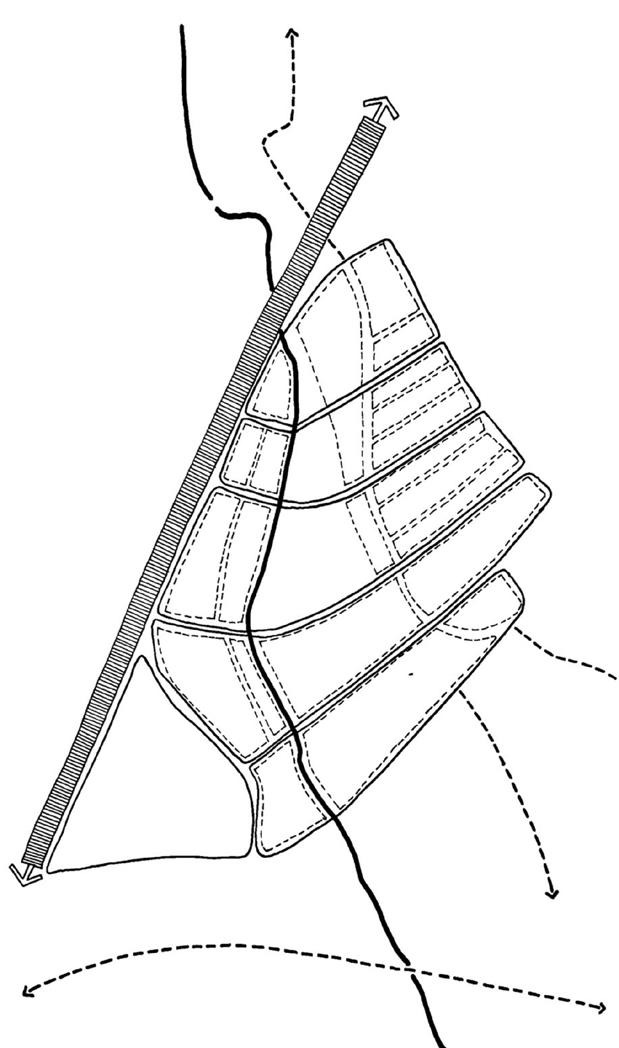

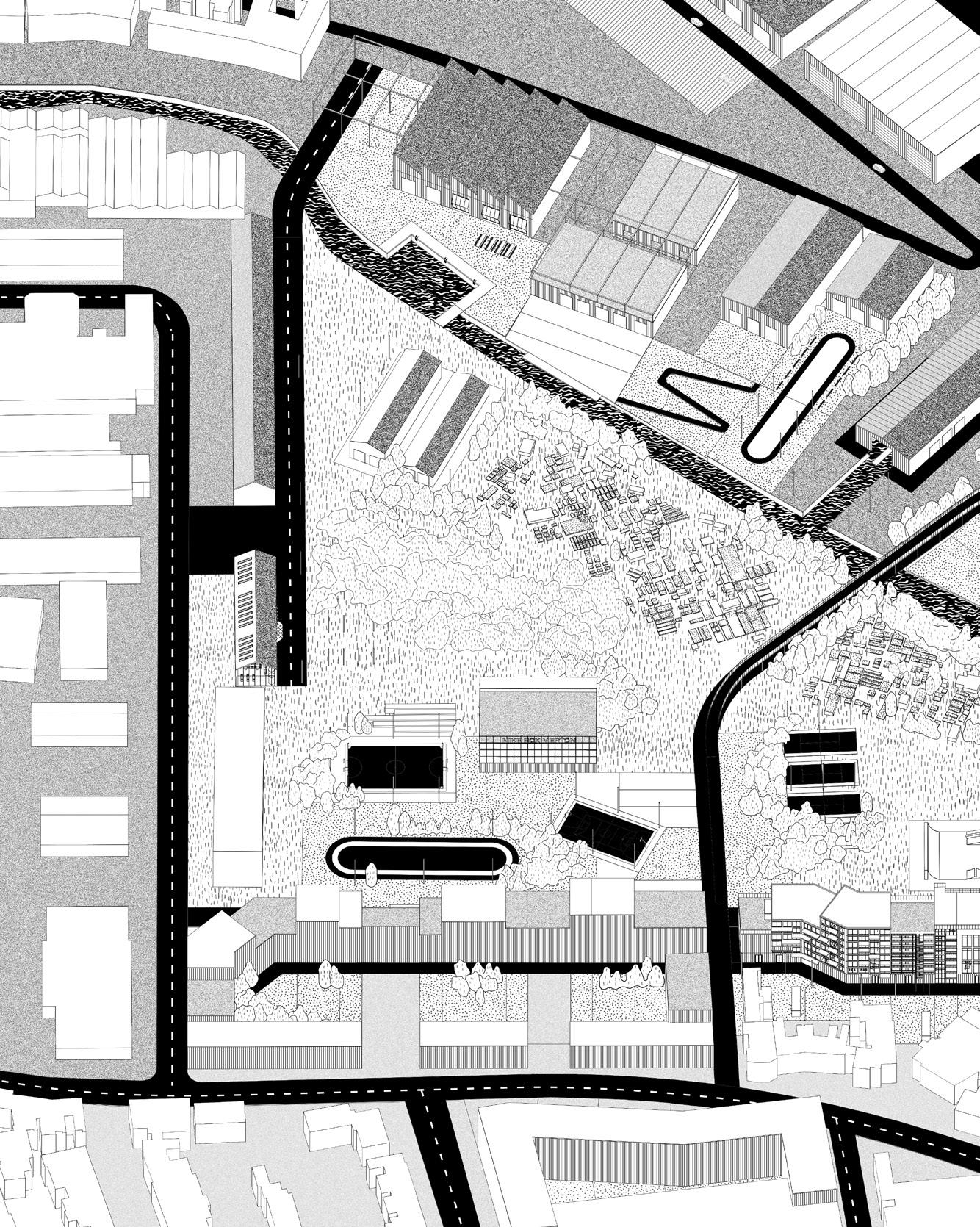

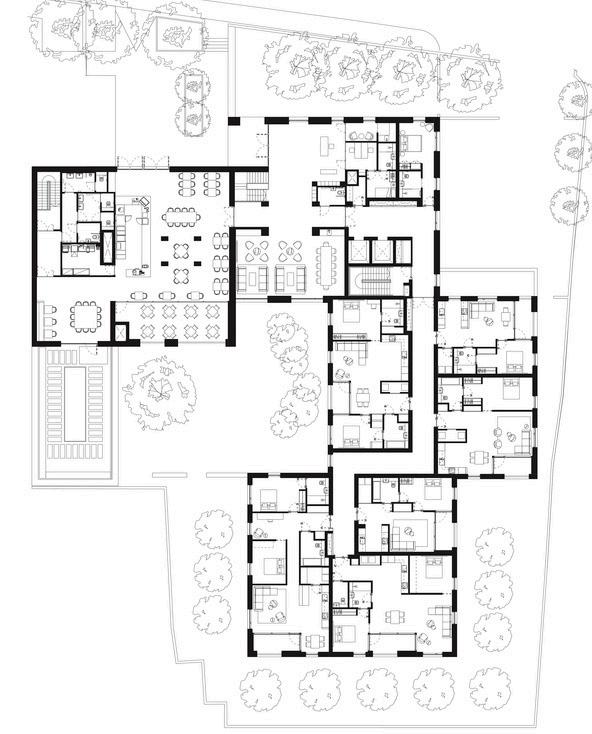

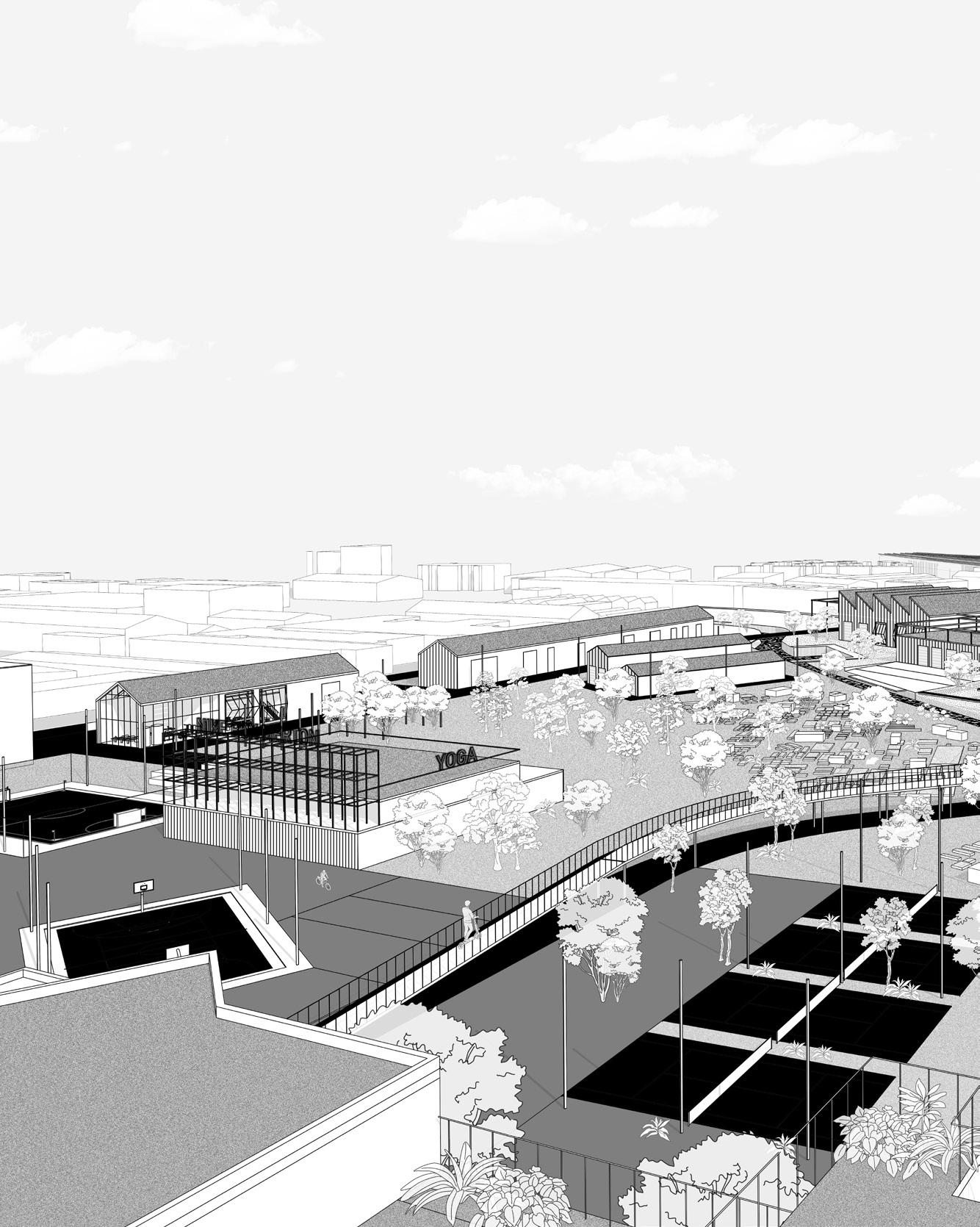

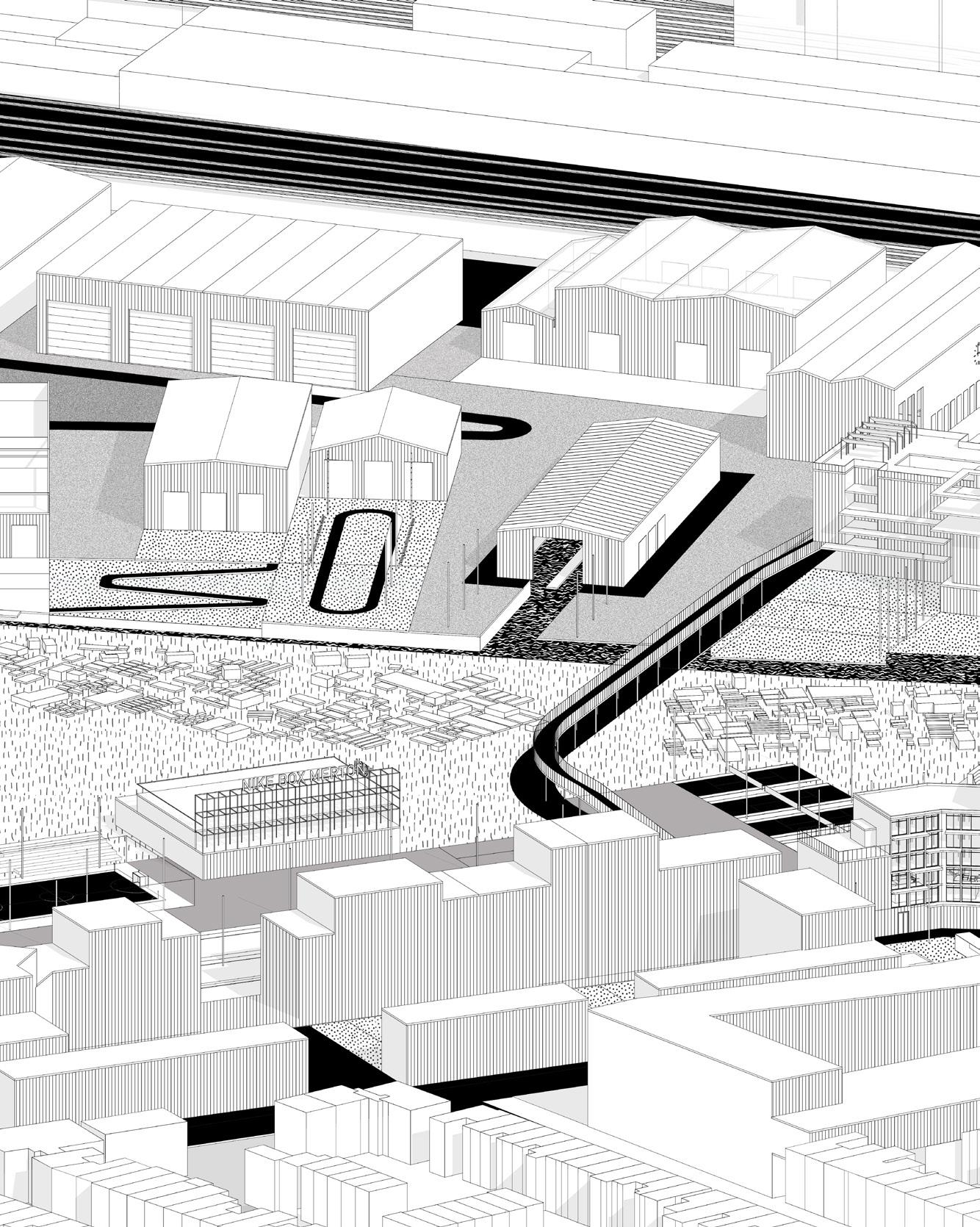

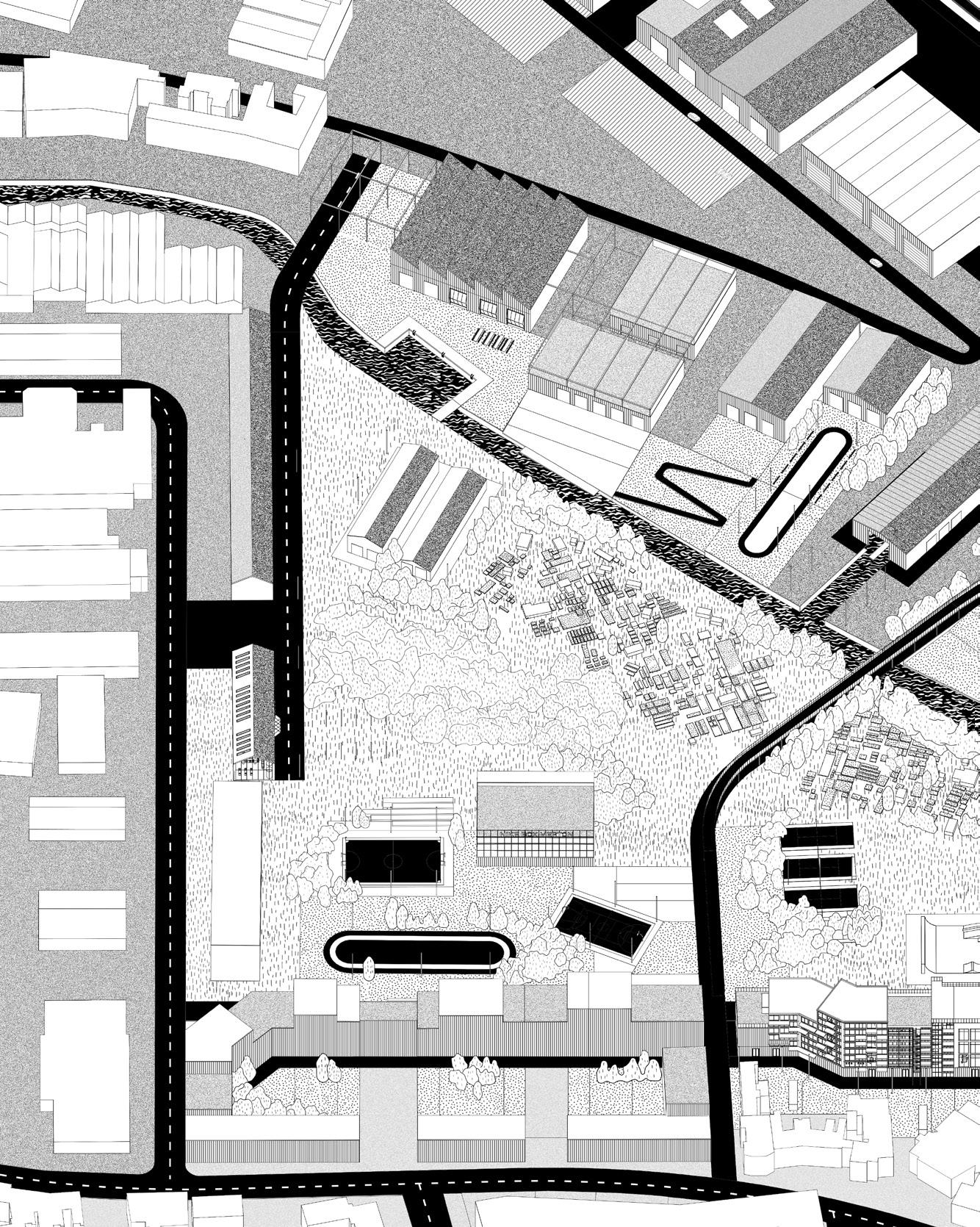

The thesis puts forward a design-led project located on the border between the Merton and Wandsworth councils, within the North Wimbledon/Garrett Business Park area. [14] It occupies a 15 ha. site, works with partial requalification of the exisiting industrial area. It puts forward an adaptable urban strategy and typological framework with a goal of requalifying the area into a productive neighbourhood which can potentially boost transformation of a wider urban area and become apart of a rethought Wandle corridor.

https://duplex-architekten.swiss/en/#/en/projects/bell-areal/.

accummulation of care environments oriented towards collectivity as a framework for a new version of neighbourhood

Although in general the morphology of the Wandle trail comes across as broken and irregular, there are consistencies to be found if we zoom out and look at the corridor holistically. The high-street, railway and Wandle armatures emphasise the prevalence of the North-South axis of the corridor and start forming distinctive post-industrial enclaves along the water. [15-20] Following David Graham Shane, each of these enclaves can be read as a ‘recombinant assemblage’ working on the basis of neighbour-to-neighbour relationships of the fragments, as ‘an unpredictable, self-organised system with strictly local rules that can nonetheless produce predictable largescale patterns’6.

Within the disjunctions and irregularities of the enclave fabric certain strong urban conditions can be found. For the purposes of this research, 3 of them are rethought. They are: the industry, the park and the high street. [2129] At the moment each of these conditions presents its own conflicts.

The issue of losing employment lands to housing has become urgent in the UK over the last years7. However, an attempt to continuously retain industrial land leads to creation of conservation areas and the strategies offering crossovers between production and housing often ends in a 'limited promise, seized upon as a nostalgic dream, thereby unconsciously transformed into an unsatisfying theme park’8. Crossovers with new care ecology could help us to retain viability of the employment lands by broadening the set of businesses they can support.

We are shifting our attitude to the role parks have to play in our cities today from ‘negative’ green spaces to places promoting event-led urbanity and different culture

of using green and blue infrastructure that is more civic oriented and activity-based.

Today the traditional high-street so typical for residential areas of London is struggling to redefine its purpose. We see the need to shift away from a concentration of commerce to a less linear and more layered way of organising our daily rhythms.

As a result of all these conflicts, we tend to separate these environments to have dedicated city spaces for production and logistics, for leisure and sport, and for everyday activities associated with home, family and work respectively. The fact that they overlap only for a limited amount of time and do so ineffectively, is the reason why areas like the one we are investigating, are under-performing.

6 David Graham Shane, Recombinant urbanism : conceptual modeling in architecture, urban design, and city theory (Chichester: John Wiley, 2005): 145-146.

7 Oliver Wainwright, “Made in London no more: will property speculation kill industry in the capital?”, Guardian (2017), https://www. theguardian.com/cities/2017/feb/06/made-london-property-speculation-industry-capital.

8 Julia Spirig, From employment land to makers society (London: Architectural Association, 2021): 10.

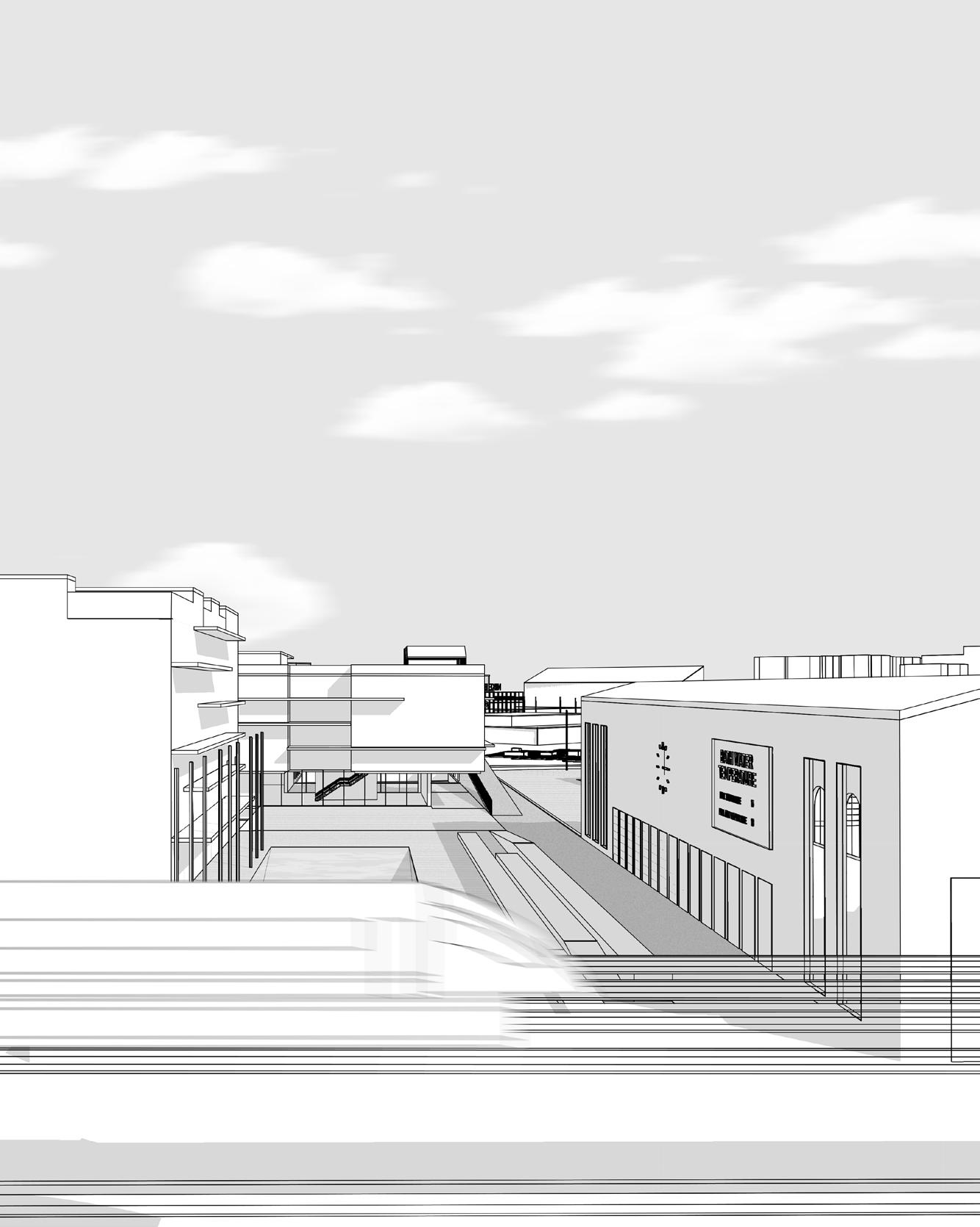

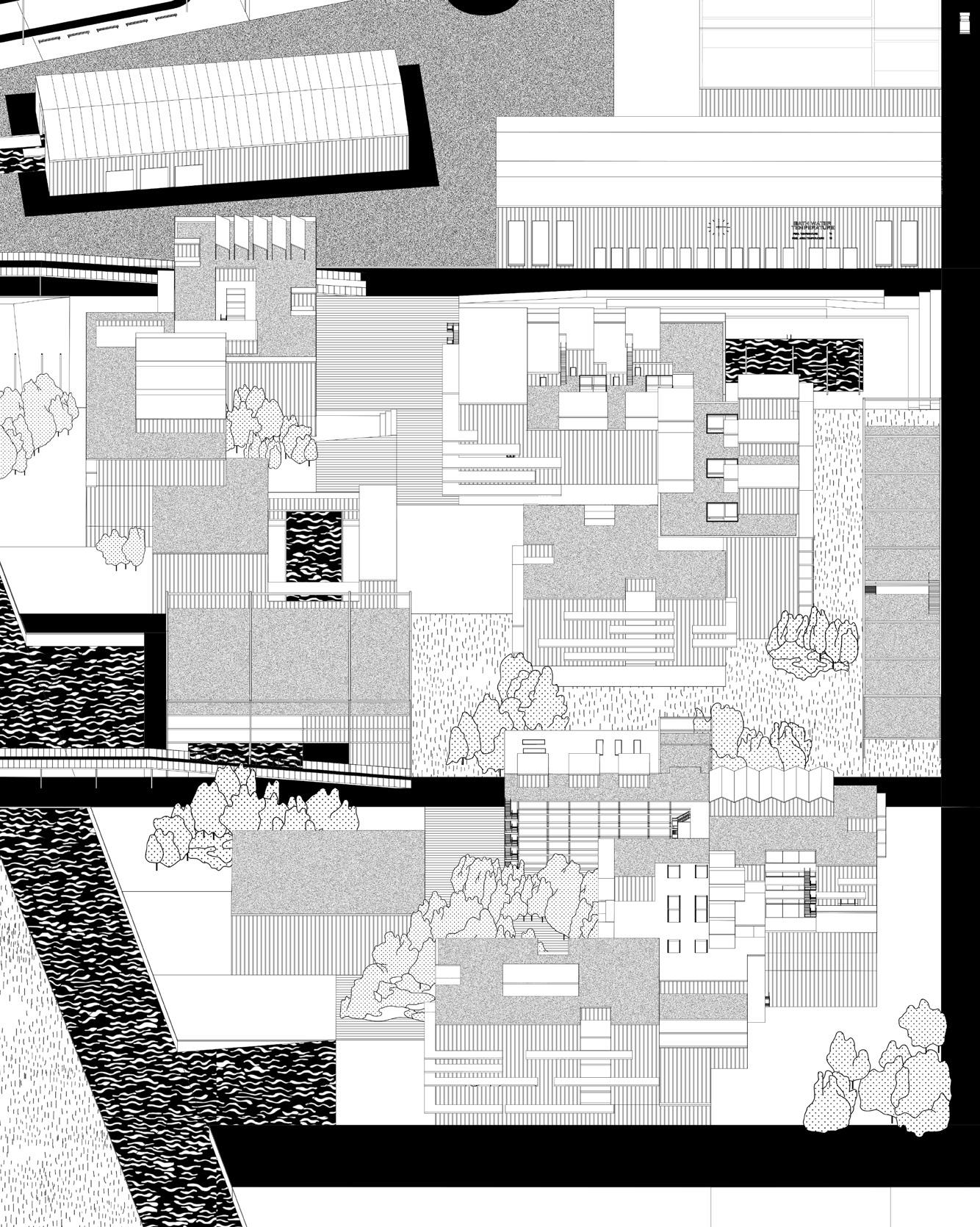

To start changing the way the enclave operates today and to address the challenge of separation described above, thesis suggests to rethink the way service delivery is currently organised on the site. Right now the heavy mobility and logistics routes are spread within the industrial part of the area with the main access road located between the sheds. Therefore, the space between the industrial structures is compromised by the parking of heavy machinery and delivery trucks and vans. As a result, the connection to the land in the northern part of the site is restricted, in addition to the railway line running in the West and river in the East. It makes it challenging for any substantial development to come in and start forming a dialogue with the industrial land9. A solution put forward by the project is to organise a separate service corridor between the back of the sheds and the lifted railway line by disassembling part of the sheds structure and shifting their borders farther in. This could unload the logistics and servicing demands off the industrial yards and turn them into much more purposeful civic-oriented spaces engaging with the waterfront and accessible for the local residents. The goal is not to mask the activity that belongs to the realm of the sheds. On the contrary, the space between them can still be productive and used as a working yard. However, all the ‘disruptive’ mobility is handled in a much more systematic way and allows to unlock possibility for a different landscape.[30] In order to allow for seamless and quick turning of large vehicles in the corridor, as well as create a dedicated parking area for them, one of the existing sheds structure is transformed into a garage.

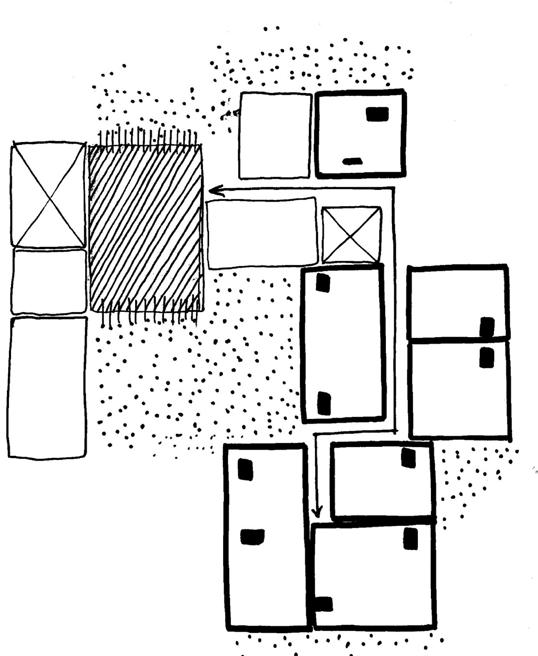

Paying attention to the way the buildings on the site are currently organised, one can notice that despite the fact that the North-South axis is the dominant one, the eastwest direction is already registered in the way the industrial structures are organised on the site. They form an array located almost perpendicular to the waterfront.

This exisiting parcellation provides a system of striations that run through key armatures (the railway, the river, and the road). They also give a sense of dimensions and help to locate the ptoject as something that establishes balance and integration within a wider circulatory system.

The project uses the existing directions formed by this array and transforms them into physical links – the new light mobility routes crossing the river and connecting the industrial land and new clusters to the high street on the other side.This way the waterfront becomes an extension of the buildings’ organisation logic and part of the everyday life activities of the residents, putting emphasis on actively engaging with the water. [31-33] The existing park in the middle of the site becomes a crucial element in negotiating between all the elements of the site.[ 34] Right now this green area is treated almost like a backyard of the residential fabric and the high-street and is under-performing.

Zooming out, the urban area of each enclave along the river Wandle can be thought of as a node within a larger system. On the basis of understanding the form and potential of each of these urban areas we can start conducting design investigations. These investigations would have an aspiration of turning what is currently the Wandle corridor into a series of well-defined, highly performing neighbourhoods; where the strength of the enclaves system lies in ‘the proximity and the accessibility of ‘the other’ Enclaves, despite their independent position, are a boon for the city as a whole. They can give the city the layeredness and multifaceted identity fitting to our present-day society10.

9 Right now a Garratt Mills co-housing project is being delivered on the northern end of the site. However, the project does not seem to offer qualities addressed at a wider urban area.

10 Dick Van Gameren and Pierijn Van Der Putt. In: The Urban Enclave, Fragments of an Ideal City, 2011. P.4-11.

The placement and dimensions of the project are determined by the existing parcels. The light industrial vocation remains in place, and new residential care-driven environments come in

The range of conditions that we have discovered while studying the post-industrial fabric of the London inner periphery [the industry, the park and the high-street] opens up opportunity to start thinking about different versions of living associated with care that are typologically distinct. Currently there is a gap in terms of architectural scale in the area and neither of the present typologies offers a way of solving the conflicts of the site that we already had elaborated on earlier. The question of type and understanding of architectural intelligence that derives from it allows us to work with challenging urban conditions and generate long-term value in multiple ways. Accumulatively, we could change the way the morphology of the areas is working by shifting our attitude to the 3 distinctive settings explored above, and by introducing a new typological starting point for each of them.

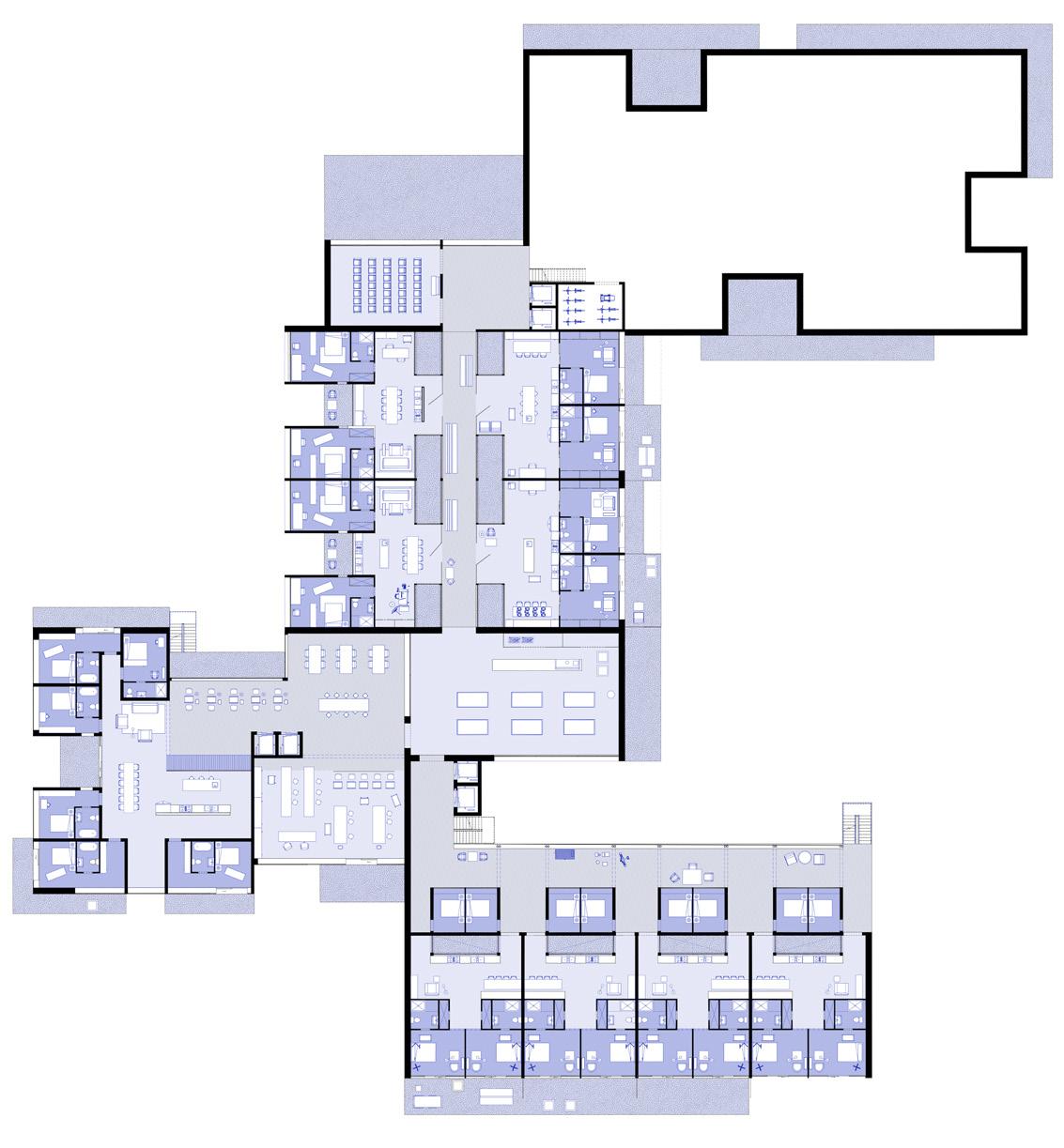

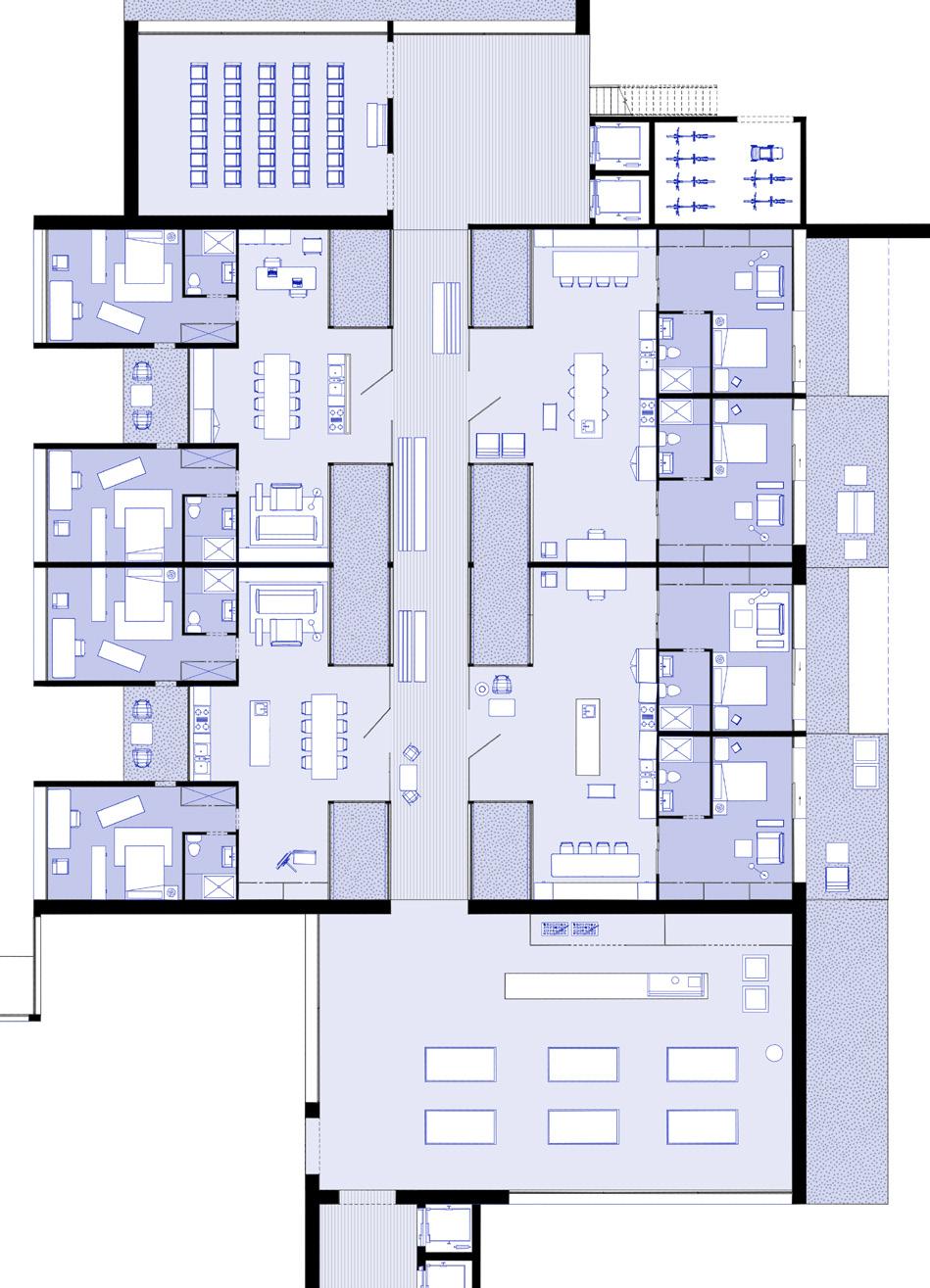

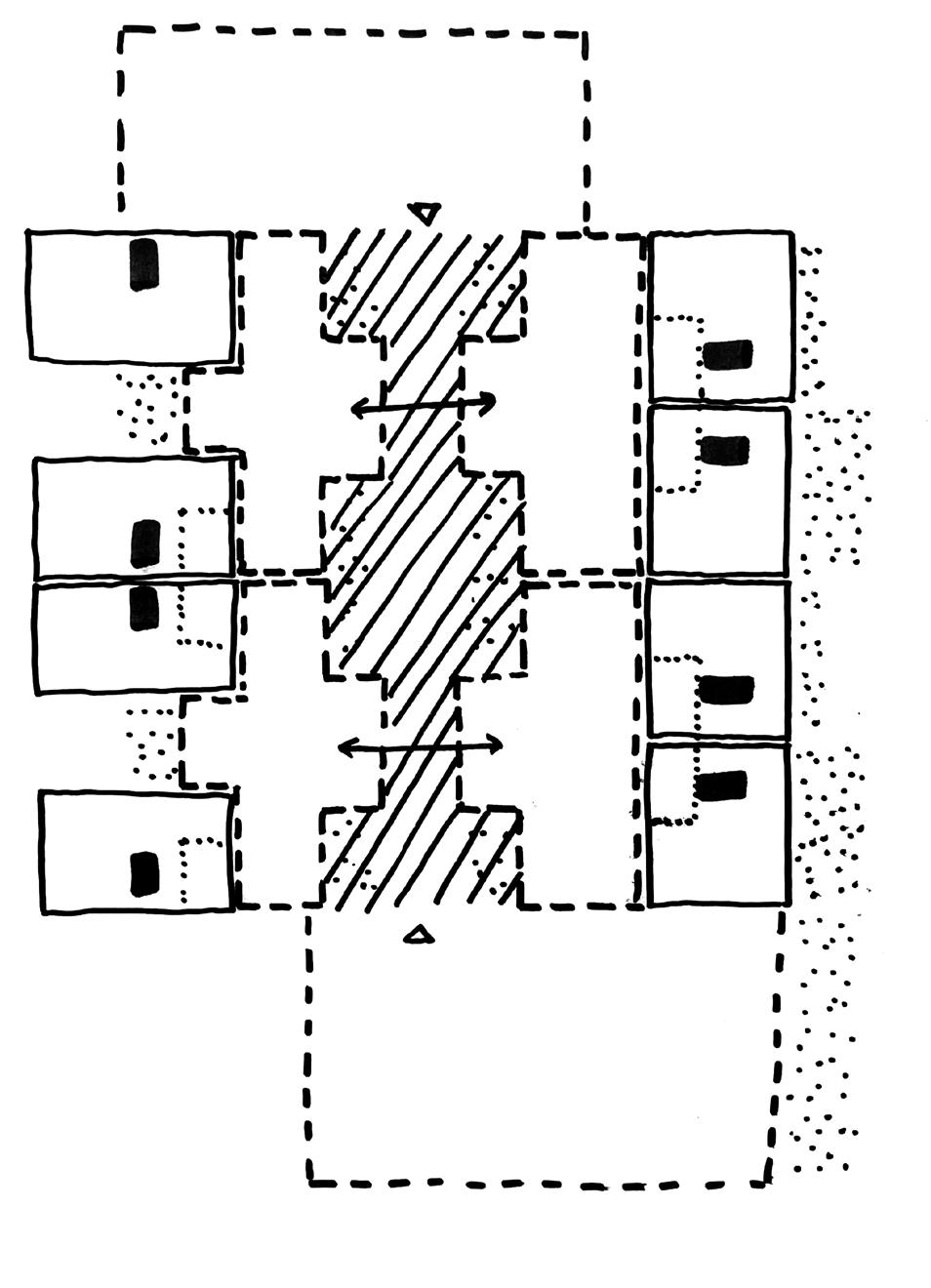

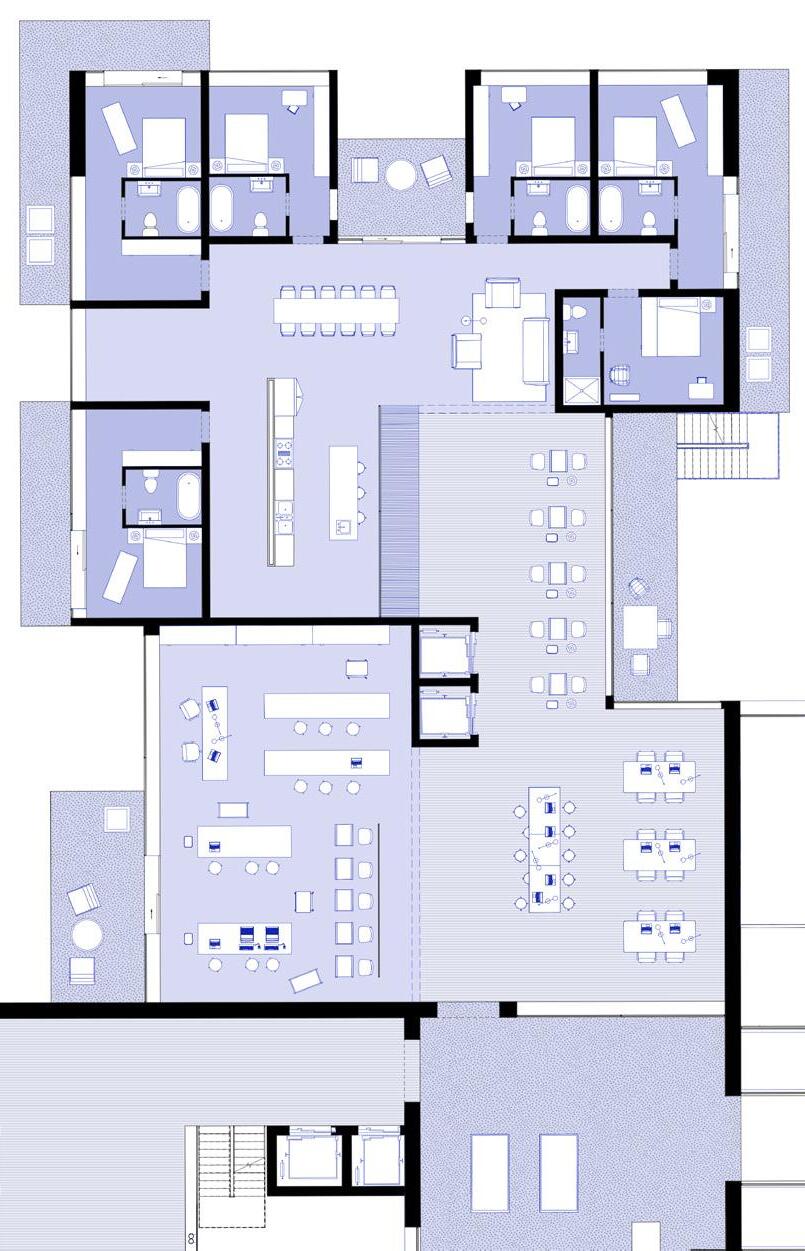

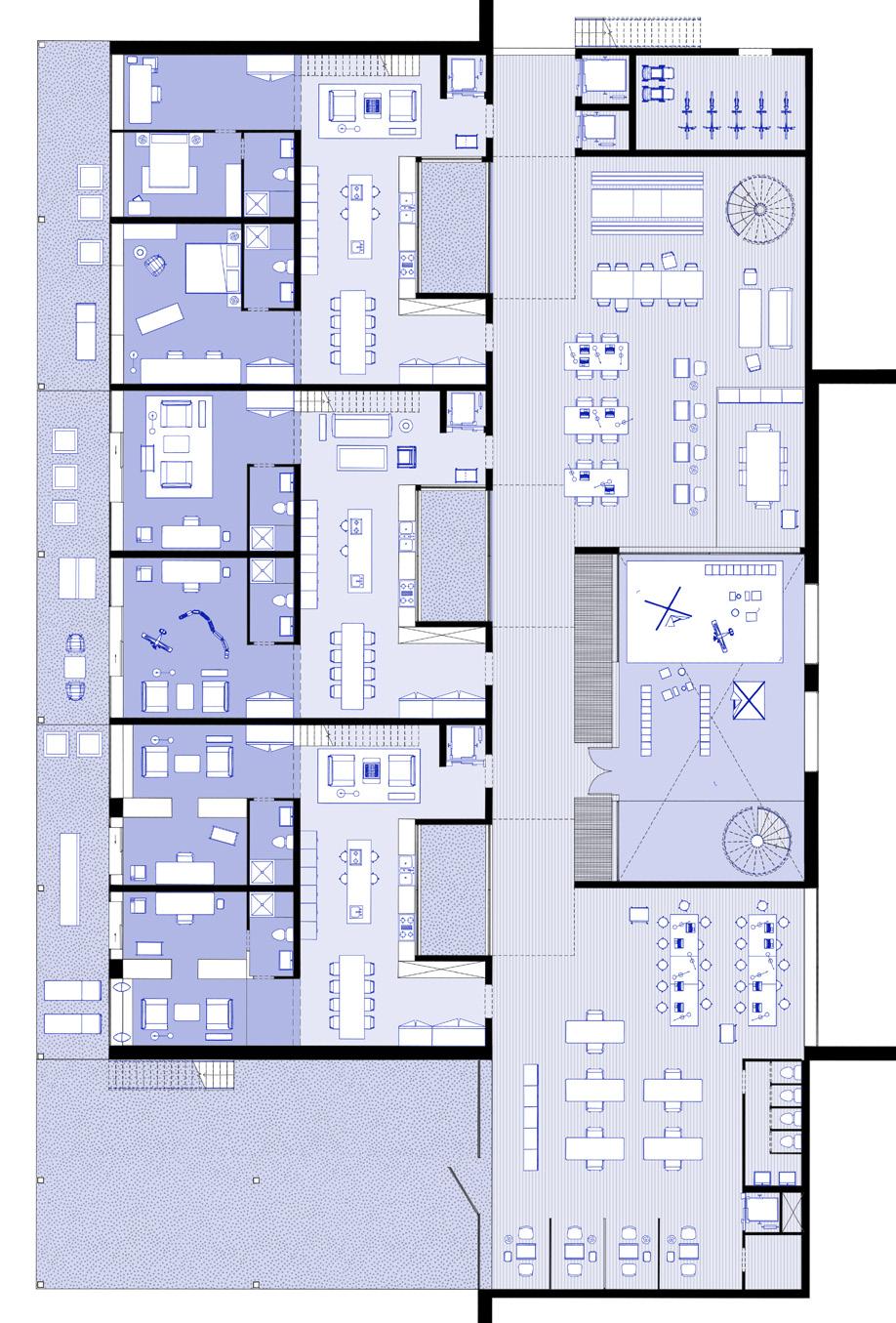

A set of deep floor-plate clusters with a range of dimensions11 comes in occupying part of the existing industrial site. [35] The relevance of such morphology is in its flexibility and ability to be expanded or reduced over time in accordance with the changing area. Every cluster can operate as a single building with its parts benefiting from the services offered by others and the collective offer embedded into their architecture. However, each part is independent enough to be built separately and occupy land sequentially, not imposing master-planning solutions on the industrial land. The system of clusters does not choose a primary orientation and works with a version of frontality that is closer to the way a campus organisation operates on a landscape, with multiplicity of entrances and a network of secondary and primary paths.

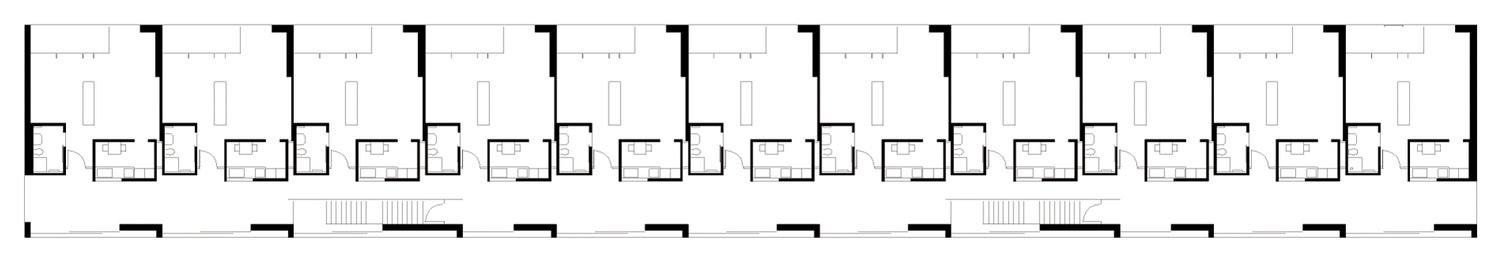

The frontage of the existing park between the high street and the river is rethought by means of a linear form that

11 width: 23-28 m, length: 35-40 m.

shapes its edge and starts to slightly shift from the high street and terraced housing inside the park.[36] A linear element offers great opportunities for handling and shaping very different kinds of environments on both of its sides.

Despite its rather simple form, it can create experiences and architectural moments that are never symmetrical in each part of the building. In order to understand the potential of a linear form, one might start by exploring the Am Lokdepot project by the Robertneun architects [37-39]. Located on the edge of the Gleisdreieck park in Berlin, parallel to the railway line, the project manages on the one hand to create a hardscape edge with ground that belongs to the city, the park itself, that assumes a possibility of an active play in the city, display activities, workspaces, etc. Clearly visible from the trains passing by, this elevation of the building is the one that allows us to quickly grasp its character in all its unity, notice all kinds of things that can happen in front of it. The opposite side of the project continues the logic of the existing residential fabric by attaching to the edges of the urban block and closing it off. This way, a very different kind of setting is created inside: a stepped terrain with a set of smaller courtyards, gardens, playgrounds, more self-contained area that is mostly enjoyed by the residents but is nevertheless accessible for everyone.

This demonstrates the different approach to linearity, and the difference that the question of orientation and handling of the facades makes to the way the building starts engaging with its surroundings. It can be particularly useful as an alternative to the linear approach of the high-street that creates a very clear distinction between the front and the back of the houses along it.

In the case of the explored site, this leads to the green space behind the high-street under-performing and acting as the backyard of the neighbourhood life. Operating with a different version of linearity, project starts to address both the adjacency to the residential environment in the east and the conditions of the park, allotment gardens and the river to the west. The western elevation faces the rethought version of the park12. It takes further the idea of urban gardening and brings in infrastructure to support the culture of the allotment gardens. On top of that, it diversifies the active landscape offer working with a range of sport facilities. The eastern facade addresses the current back of the high street, offering the existing housing playgrounds, water facilities, bike storages and gardens to share.

Car access to the park is limited and gives way to light mobility linking to other side of the river. The residents of the terraced houses of the area get more choice for their everyday activities within a new diverse landscape that acts as a threshold between the open and super collective realm of the park and the high-street, and the closed and very private spaces of their own back gardens.

Another type that contributes to the new version of a highstreet is a courtyard building offering a new archetype of a care home. [36] It offers an alternative to the current image of the typical ground floor found along highstreets by opening up generous double-height spaces to the use of the local community together with the residents of the home itself. Commerce gives way to civic-oriented settings like workshops space, a library, therapies rooms, as well as a shared green infrastructure in the middle, creating a transition from enclosed private gardens of the terraced houses. An image of such alternative to traditional housing found along our high-streets has been put forward by the WWMA architects in their Central London Almshouse project.[40-42] It has an ambition to tackle

loneliness among elderly and low level of community engagement in the traditional terraced ‘villages’ found in London by creating a building that can become a node of interaction for all parts of the local communities and a tool to integrate those who need assistance and care into the life of the city. An important feature of the Alms house project is its attitude towards the notion of threshold and level of privacy available for its residents in different parts of the building. It offers a smooth transition between the noisy and collective at its extreme realm of the street, towards spaces of the inner yard and ground floor areas open for sharing by a smaller groups of people, still allowing ‘outsiders’ to come in. To the intimate space of the circulation galleries which thanks to their width can accommodate moments of encounter and communication but are only available to those occupying the building. And finally, to the secluded and private realm of the apartment and a care unit.

12 The thesis will elaborate in detail on the idea of the landscape and its specific elements that the project is putting forward in the 3rd chapter.

Am Lokdepot, Berlin, Robertneun architects. The hardscape of the eleation addressing the park and the railway in contrast to the environemnt of the backyard shared with the old residential fabric

Alms house, WWMA architects. Another version of the ground floor addressing a high-street; one that offers gradation of collectiveness and opportunities for encounter in different forms.

One of the fundamental values of thinking through architectural type is in finding relations between its form and ways of life it can offer. If we were to talk about the housing environments that are part of a new care ecology and have the care, health and well-being offer embedded into them, we should start by identifying the values of the contemporary society, the shifts that happen in the way we prefer to live today.

Among the most noticeable are two shifts. Firstly, that the concept of a nuclear family — defined as two adults with at least one child — has long ceased to constitute the majority of households13. We are now facing the world that is extremely diverse in the type of familiar constructs it accommodates14. The legal framework and demands of the market prevent us however from building housing that would fully respond to these changes15. Secondly, an extreme digitalisation and changing work patterns of the post-pandemic world gave rise to the second important shift. Today we are looking to stretch the domain of our private dwelling, exploring the different answers to the question of what we are willing to share. Besides the purely practical considerations like opportunity to collectively manage resources, share responsibilities and have access to much wider set of services even when downsizing one’s home, it starts a conversation about how domestic realm can give rise to the transformation of a wider urban area. An opportunity to accommodate a diversity of services and establish patterns of neighbourliness is directly dependant on the ability of type to experiment with the thresholds between the freedom of an individual subject and engagement in a series of wider networks. Extension of the domestic realm, experimentation with the threshold between communication in the

group and retreat of an individual allow architecture to open up and create crossovers with a wider urban area.

Within the whole realm of care, the area of residential care for elderly has been most notably separated as a specific kind of care environment in the whole system. This is due to the fact that the demands upon this type of care provision are often among the highest. As a result, they present us with greater challenges of being integrated into wider urbanity. Therefore, for the purposes of this research, examples of care homes and assisted living environments for elderly are taken as starting points of architectural investigation as ones with the most challenging criteria of excellence.

If we look at examples of such care environments, we can get a sense that very often they are purely thought of as machines for service delivery. They are very often located in isolated rural settings where access to nature is one of the key requirements, and these environments are not designed to drive urban transformation and form life-long neighbourhoods. [43-54] Some of them, like the Belle Vue senior residence are located in the central cities environments but belong to the luxury end of the market and are still isolated from the life outside. Quite a few of these projects offer advanced typological diagrams, like the Home for Dependent Elderly People, or Peter Rosegger Nursing Home. However, they do not offer us opportunities for cultivating meaningful relationships across ages beyond highly engineered and institutionalised spaces, which also means they are not accessible for families.

13 Niklas Maak, "Post-Familial Communes in Germany”, Harvard Design Magazine, no. 41 (2015), http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/ issues/41/post-familial-communes-in-germany.

14 In addition to the familiar constellation of father/mother/child, there are more of the DINKs and LATs, the single parents, the divorcees, the part-time parents, the residents of functional shared apartments, the minimalists, the polyamorous, the multilocals, the digital nomads, and so on and so forth. Ludovic Balland, Nele Dechmann, ‘Duplex architects rethinking housing’, (Zurich, Park Books AG, 2021): 79.

15 Unlike, for example in the DACH region where the tradition of collective housing as well as ‘non-traditional’ housing forms have a long trajectory due to the specificity of legal apparatus and institutions in place.

43-44: Home for Dependant Elderly People and Nursing home. Spaces intended for collective experience are unproportionally large in contrast to the individual care units and do not offer any particular reason to occupy them, except for the dining experience.

45-46: Peter Rosegger Nursing Home. A beautiful typological diagram is thought of in terms of the service provision efficiency, not opportunities for meaningful interaction and building of networks.

47-48: Belle Vue Senior Residence. The project offers beautiful landscape elements and works with attractive materiality. It is however managed as a secluded entity that does not offer anything to the city around it and does not interact with it much.

44-46: typological exploration of the above mentioned projects as a way to ‘distill’ the main ingredients that constitute this type of care environments. These are: living areas of the individual care units, natural elements /green spaces, and service elements.

2.3

‘Architecture must take a more even-handed approach to satisfying the opposing needs for communication and retreat, while also devising ways to spatially combine them. We can understand them as poles of a dialectical system that not only specifies housing types but also determines urban space. Community hinges on a spirit of voluntariness. Its quality is manifest in the freedom of being able to swing back and forth between these poles at any given time’16

Re-evaluating the question of extended threshold between the collective experience and individual freedoms becomes key. ‘Traditional’ diagrams only offer a transition from an individual living cell reduced to a bare minimum to the highly collectivised space available for sharing to all the residents. An alternative is to create a more sophisticated gradation and organise common spaces that have character and are shared by those who have a sense of common culture. From a personal unit where one can productively spend time on one’s own to a space for hosting and sharing within a small group up to 10-12 people, to a bigger space open to wider set of neighbours. Here, the understanding the fundamental logic of a small group behaviour17 becomes important. Process of building meaningful relationships, acquiring relatively deep knowledge about others and participating in group activities gets challenging and ineffective after a certain number of people. In addition to the considerations mentioned above, one more starting point for a change is that the sense of common purpose and feeling of the common space can be cultivated through the ownership.

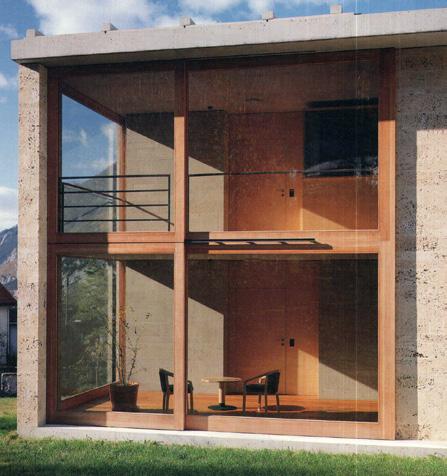

An elegant illustration of this notion can be found in the project of a Home for Senior Citizens by Peter Zumthor. [55-59] It works with a very simple diagram of a linear block where a set of living units is located on the one side of the building with all of them open into a common

16 Balland, Duplex architects rethinking housing, p 89.

glazed gallery. If we look at the dimensions in the section, we can notice that the width of the shared gallery is the almost the same as of the private bedroom. The photos of the gallery show that the space inside the gallery has been appropriated by the residents in different ways. In general, it makes a very different impression than the large empty communal spaces found in other projects and comes across as a space loved by the residents and the one that is widely used by them.

17 We do not claim this work to have expertise in the question of the small group behaviour as a separate realm of psychology but we do offer a translation of it in relation to the realm of architecture and spatial organisation, learning from case studies found in the domain.

A chance for partial privatisation of the common space, spatial generosity with understanding of the numbers involved in different activities, shift in attitude towards the spaces of circulation and storage – these are among the notions on which the project starts to elaborate. It uses one of the newly introduced types, the deep floor plate cluster, to show different versions of dwellings that reflect upon changes in the way we live today and imagine more self-organised systems than the ones we see happening today. [60-61]

The first scheme [62-63] explores the rentable assisted living that could serve for people who are willing to downsize their households after a certain age but are not ready to give up on the set of services that the central city has to offer. The project suggests that they can lead an independent life but live in close proximity to their families and friends, being in control of the time they spend alone or with others. The spatial diagram is organised around the central axis – a widened circulation space that simultaneously acts as a social space shared and owned by all of the residents. [64] It then transitions through the bridges between the light-wells into spaces, each of which is dedicated to the life of 2 residential units. These ‘living rooms’ act as thresholds between the private realm of a single unit and the collective gallery. They give the residents an opportunity to host their friends and families without unnecessary intrusion into their private lives, or work on their own or with a single neighbour. There is geometrical complexity embedded into the structure of the living units themselves. Breaking from the traditional rectilinear form of a typical care unit, it works with an L-shape. It allows to avoid entering directly at the bed and micro-manages the separation within the unit itself: the storage and bathroom entrance are distanced from the area for working, sleeping, doing yoga or reading.

On the one side of the block balconies are arranged in a chequerboard way to provide more diagonal visual synergies and contact opportunities across the building. On the other side small terraces have more private character

and can only be shared by 2 people who are also sharing the living room area.

The gallery continues outside of the building, leading to the other 2 schemes within the same cluster. One of them offers a short-term lettable accommodation intended for the care staff, following a hotel concept.[65] Besides living units this part of the cluster also has access to research, library and write-up spaces. Such scheme allows those employed at the local hospital or local care facilities to arrange short-term stays in case they can’t travel on the same day or need several days to stay and work on their research without leaving their workplace.

In the third scheme, the logic of the diagram shifts from the one organised around the centre to the one that is works as a linear form, with clear differentiation between the two sides. [66] The access gallery is 3.5 m wide, is externalised and aims to be not only primary circulation space but again a space of encounter open for appropriation and adoption by the residents. The depth of the building allows to accommodate a dwelling for those who are in need of care and assistance on a more regular basis. The bedrooms organised in the same L-shape logic are brought in the depth of the apartment, with access to a spacious balcony that can be used for bringing the beds outside into the fresh air. The space between the entrance and the care unit is dedicated to dining and cooking and is adjacent through light-wells to a series of additional bedrooms. These rooms are intended for the care workers that need to stay overnight in order to look after their patients. This organisation can be used to serve not only the ‘intensive care’ units but the entire cluster.

Typical floorplan of a cluster working with deep floor-plate. Each part can work as an indepenedent unit but there are efficiencies to be gained both in terms of lifestyle and delivery model when the building is managed as a whole.

type addresses question of subtle gradation of privacy within the housing scheme

Widened central circulation space is open for appropriation and partial privatisation by the residents, and creates another opportunity for encounters

assisted living with units for care staff

Another scheme is designed with life of potential key workers and their families in mind. [67-68] It can be inhabited by different groups of people: several individuals, non-nuclear families, families with several generations, etc. It elaborates on the idea of offering very different versions of sharing that we struggle to generate in the market-driven housing projects today. Our opportunities for encounter, social interaction and collective experiences are limited there by either spaces dedicated for very specific events or highly engineered and institutionalised settings. There is another approach pursued in such successful collective schemes as Spreefeld in Berlin, Musikerwohnhaus in Basel or Wohnprojekt in Vienna [69-71] that embed among other shared elements the notion of collective raising of children into their residential environments. Being parents becomes way easier as the realm of childcare is seamlessly integrated into their lifestyle along with work, education, leisure and hospitality.

The project offers to parents in the cluster opportunities to care for kids, share these responsibilities with other residents and have services that normally me imagine travelling far for, at their doorstep. Culture of trust and ‘beneficial togetherness’18 becomes crucial to the scheme. A daycare space is incorporated in the middle of the floor plate, integrated within the ‘collective’ part of the building – working spaces of different formats that are accessible not only for the residents of the building and act as resources for the cluster as a whole. This way the spaces that we traditionally would put on the opposite sides of the ‘need for privacy and isolation’ spectrum, like workspace and nursery, come right next to each other. It gives the residents flexibility in organising their daily routine between workplace, home and parenting responsibilities.

The side of the floor plate located across the corridor from the working area and the nursery is occupied by the double-storey apartments that share dining, cooking and

recreational spaces on their ground floors.

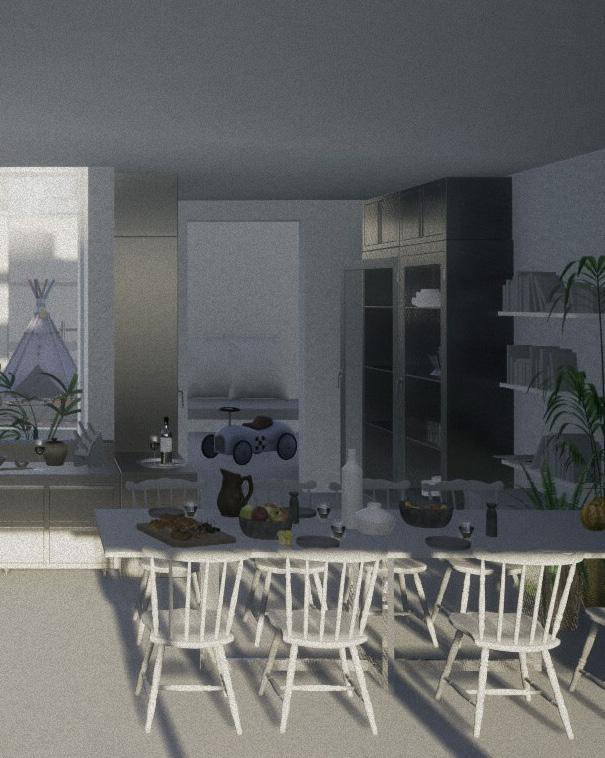

Coming back to the question of which part of the everyday life one is ready to share, several projects would answer by saying: cooking and eating. And indeed these are things that we are usually not hesitant to be seen doing or to physically share with the others. The kitchen often becomes the part if an extended threshold that is part of the collective experience of the place and helps us to construct wider systems of neighbourliness and trust. In projects like the Riff Raff and KNSM kitchens are brought closer to the ‘active’ facades becoming part of the visual engagement with the surroundings and with the neighbours. [72-74] The project suggests to take the notion of such visual engagement and give it a supervision quality in relation to other environments. In such a way, that there is a layering to the spaces, starting from a shared kitchen lit by a light-well, through the shared gallery and to the nursery and workspaces. [75] It allows to establish a whole range of possible interaction patterns between the residents and the visitors of the building.

18 Katharina Borsi, Shapiro Anna, “Type, New Urban Domesticities And Urban Areas (http://cloud-cuckoo.net/fileadmin/issues_en/issue_38/article_borsi_shapiro.pdf)”, in Wolkenkucksheim: Internationale Zeitschrift zur Theorie der Architektur. 24(38), 149–166.

Wohnprojekt, Vienna. Shared spaces for cooking establish additional layer of visual angagement and supervision with spaces for childcare

Spreefeld,Berlin. Growing up in this project, kids get an opportunity to become part of an extended family that reaches way beyond their own household. They get to learn, play and share with the whole neighbourhood without having to leave the relam of their homes

Mehr als Wohnen, Zurich. An extended threshold between circulation space and the dwelling occurs through the cooking space. It does, however, depend on the individual household , how much is shared with the outside.

Spaces for cooking and dining become part of the visual engagement with the surroundings and is given supervisional quality in relation to the spaces across the hall.

New version of landscape becomes key to successful functioning of a care ecology. It explores the civic potential of green spaces in our cities, role of sport, food and event in establishing environments of care

We have already identified the reasons that allow us to think about the potential of a new kind of care ecology and why it could be fundamental to transformation of neighbourhoods in the Wandle corridor of London inner-periphery. Requalification of 3 distinctive urban settings, new systematic approach to questions of servicing and mobility, and typological exploration of care-driven housing are the tools that the project operates with. Application of these tools invites us to think about a new kind of legibility that unites all of the project elements. If one elaborateson the tradition of high-streets in the UK: the underlying principle of them is a linear pattern of things one can do and services one can use, all united in a single system.

The aim of the project is to create a new version of system of accessibilities, breaking however from the regularity of a high-street and moving to a scale of a neighbourhood. The walk along the river Wandle could turn from a straight-forward route from A to B into a network of opportunities that one can take all along the way: from the requalified ground of the industrial area and the civic realm of the new care environments to the park and rethought high-street. A new version of landscape becomes key for shaping such network and shifting from the master-planning attitude to the landscape that is architecture driven and relies on different organisational devices.

The role of landscape [the green and blue infrastructure] in our cities as of a traditional picturesque environment that does not offer much apart from opportunity to observe nature, started to be rethought a long time ago by various architects and urban planners19. It is now rather seen as platform ‘that can sustain not only recreational functions, but also housing, services, educational, cultural functions an even becoming the surface for local circulation and active synergy’20. It also means gaining civic21 power: the role of landscape and of amenities it brings with, is to engage those who live around or are even just visiting, to give them an opportunity to participate in the decision-making that concerns the place. In the context of the project it would mean a shift from the corridor as a ‘diffused’ area to a series of neighbourhoods that nurture a sense of belonging and bottom-up patterns of communication.

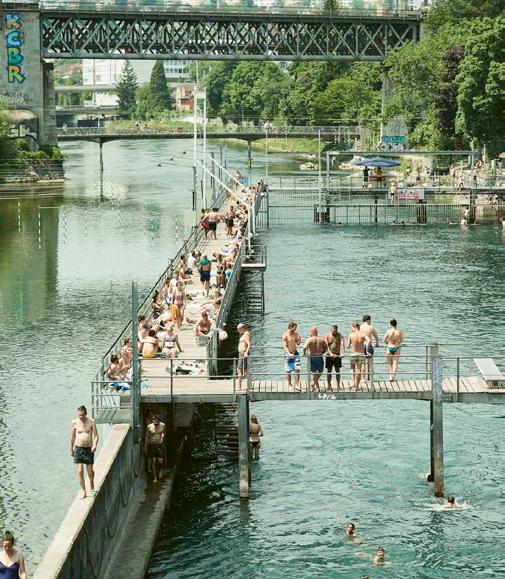

Namely, the project rethinks the landscape through several key areas: health and well-being, urban agriculture and event, and sports. Active engagement with the water in various ways becomes important to all of them, so that the waterfront can turn into a significant place for everyday activities of the neighbourhood residents and guests.

19 e.g Parc de la Vilette, Gleisdreieck, Burgess park, Zaryadye park

20 Marlene Ortiz Rivas, Something like a park. The changing role of landscape as a tool for urban requalification (London: Architectural Association, 2020): 24.

21 In this research the word civic is used in the sense it was described by Peter G. Rowe in ‘Civic realism’: ‘to be civic is a position that requires, at heart, some kind of convergent or communitarian concept to which people’s conduct can correspond.’ Meaning the design that allows people to take responsibility for it, take part in the decision-making processes that concern the place and appropriate it in different ways.

Nordhavn waterfront, Copenhagen. Active use of the water resource together with developed systems of micro and smart mobility

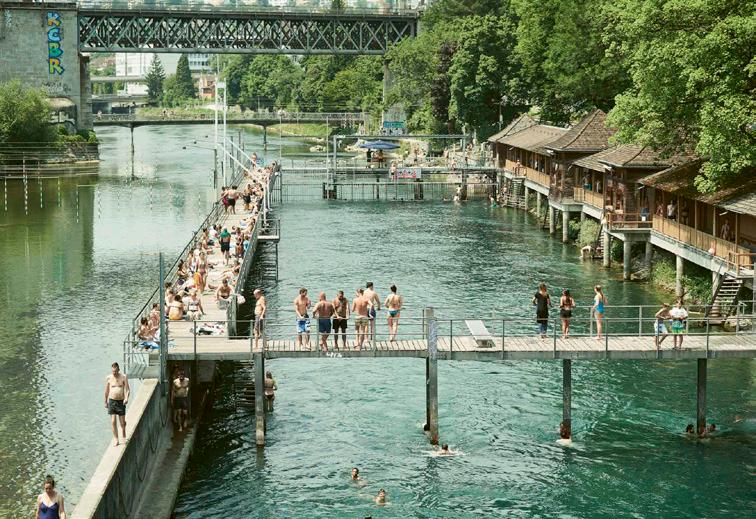

We could start by learning from the cities that have a rich history of projects taking full advantage of their water resources. Kalvebod Bølge project and Nordhavn neighbourhood in Copenhagen, culture of ‘badis’ in Zurich [77-78] – are examples of how the waterfront can perform much stronger than a framing device to our walking and cycling routines. It starts offering an opportunity to have a quick chilly swim in the morning right in front of your house, or to store your boat in a shed just outside your office and go out fishing right after the working day is over. The riverside becomes a layered ground where we find things that traditionally are associated with the rural settings: fishing, bird-watching, doing water sports, etc.

The exceptional care that the local community22 has been giving to the river Wandle over the years helped to return it to ‘almost pre-industrial cleanliness’ 23 and support a rich biodiversity of the corridor. The river is therefore an amazing resource around which the landscape can evolve. The area that used to serve as the back of the working industrial sheds is now addressed towards the river, bringing in a rowing school, a boat workshop and partially supporting the urban agriculture and event infrastructure on the other side of the river. Further along the waterfront a new shed structure is brought within the residential development. It serves as water sports equipment storage and rental on the ground floor with direct access to the water and as a civic structure for residents on other levels.

One of the parts of the site heritage are the allotment gardens which are significant to the culture of the place. We could treat them as an opportunity to bring in the idea of food and food-related events as something that gives greater role to our assemblages. Projects like Le Paysan Urbain in Paris and the Omved Gardens in London are perfect examples of how the idea of gardening, urban farming and the general interest in food in an associational way are developed in our cities today. The idea of gardening at one’s private allotment is expanded

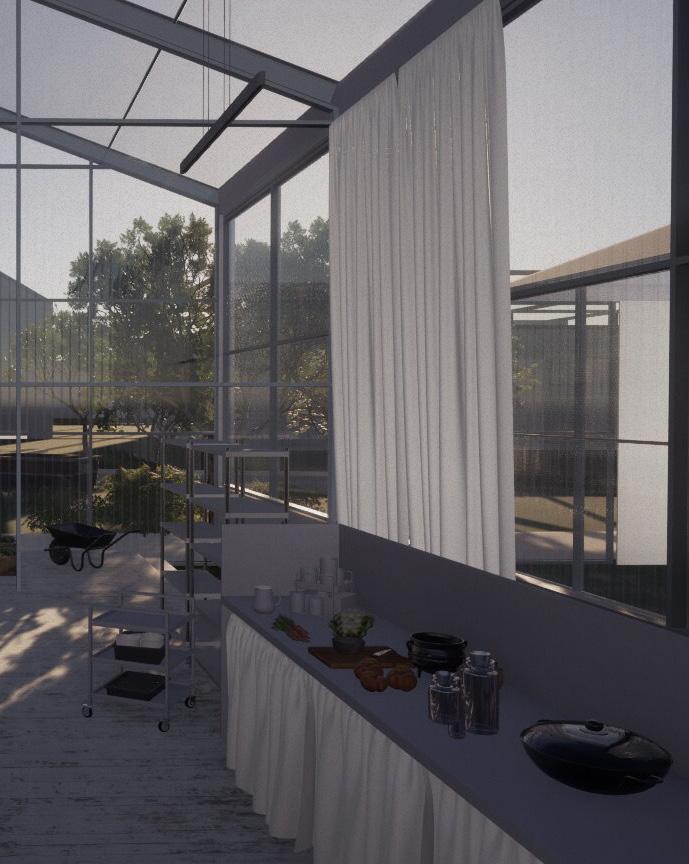

into a whole system that has nutrition, awareness of what we eat and how it gets processed in its core. The actual process of growing up food is combined with questions of learning and inter-generational exchange. Greenhouses, orchards, gardens become places where one can hold workshops, community events, where children can come and learn through play and practice about crops, importance of biodiversity in our cities, and food production. Such a setting can give a new direction to how we curate events in our cities, from food-oriented workshops with renowned chefs to weddings on the waterfront. In the case of the project, location of the allotments just across the river from an industrial site opens up an opportunity to support the logistical side of the food and event-driven environments. Large flexible industrial structures and the new mobility system can be used to cover the servicing needs of the food production. [84] An additional layer of infrastructure is brought next to the existing allotment gardens – greenhouses, an orchard and spaces for catering and event-hosting. The existing sheds along the edge of the site house storage, waste-disposal, compost and shelters for delivery cargo-bikes. This way, elaborating on the cultural and historical background of the site, the landscape can be given a new vocation that celebrates food, brings people around eating and producing.

Another traditional element that the project is using is the idea of a Lido. Found in many boroughs of London, Lido pools have their own character and atmosphere and are sometimes rethought in connection with other amenities like restaurants and wellness facilities like the Bristol Lido. An outdoor swimming pool can be a rather obvious but nevertheless instrumental element of a landscape that targets promotion of health, well-being and care. Bringing it in the heart of a residential environment means another set of opportunities: swimming lessons, leisure swims, sun baths become the extension of the everyday life of the assemblage.

22 e.g. Wandle trust, Living Wandle projects. The Wandle Trust is part of the South East Rivers Trust (https://www.southeastriverstrust. org/) (SERT), an environmental charity which aims to deliver healthy river ecosystems across the south east of England.

23 Paul Talling, London’s lost rivers (London : Random House, 2011): 232.

The industrial land extends towards the riverand becomes a more civic-oriented surface housing a rowing school, a boat workshop, and a new walking and cycling route along the Wandle. They also act as supporting servicing infrastructure for the rethought realm of urban agriculture and allotments on the other side of the river

Industrial shed next to the allotment gardens can become a setting for catering event, cooking workshops, or arestaurant that collaborates with the producers next door and takes advantage of the freshly grown local foods. The dimensional characteristics of these spaces become instrumental to other spaces in the project. The gsubstantial height of the ceiling and large window surfaces on the ground floor becomes crucial to the quality of light and air, and to the range of programmes these spaces can accommodate

One of the goals of creating a multi-layered and textured landscape like the one we have been describing, lies within the realm of decision-making, governance and associationalism. The ambition behind the transformation of the neighbourhood is to shift from the notion of diffused area that is just formally part of a corridor to a place where its parts are linked together by networks of effective communication. Here, the patterns of civic participation and qualities of the landscape and architecture are tightly knit. A complex and layered landscape ‘thickens up’ the way in which we look at the urban area today, turning into a network of spaces where each of the elements provides a platform for moving to something else, in a pattern of an ‘active ground’. Each of the amenities in the landscape is a scene by which stakeholders, employees, residents engage with each other and contribute to the success of the place as a whole, so that the civic life is proliferated by a range of practices. In the case of the project, these practices evolve around ideas of food and event, sport, health and well-being, forming bottom-up organised systems that run through care, education, research, etc. Potentially, different versions of civic organisations beyond the realm of federal institutions could become interested in joining up and promoting a range of services and activities in this landscape. These sub-forming patterns of communication and civic life contribute to the way the local leadership can govern the area, by relying on those who are ‘closer to the ground’.

The question of associationalism is tightly knit with the sense of subtle variation, hierarchy and gradation of spaces that are embedded into the organisation of the ground and architecture. The project aims to start accumulating the sense of belonging, participation and create a ‘textured’ environment from inside the building to the realm of the landscape. We have already showed how exactly type can proliferate a sense of belonging and balance between the individual and collective realms at the scale of a dwelling and an assemblage. At the scale of the landscape, the rhythm of the spaces and their intersections become important. They change from the active, articulated waterfront of the industrial area, making a transition into almost campus-like organisation

of the residential clusters where a network of courtyards, plazas and lowered gardens is formed. If the former offers open views on the water, visual engagement with the allotments and the park on the other side, the latter woks with subtle variations in the views that open between the buildings, wider range of sizes of spaces and more enclosed environment overall. Continuities between 2 sides become physical through the new system of light and smart mobility and extend towards the existing residential environments. There, again, a transition is formed between the dynamic, engaging qualities of the park and its sports-oriented part towards the residential realm that is nuanced through introduction of a new linear form. A careful attention to the nuances of the public realm lead to a changing logic of an inner-peripheral neighbourhood. A fairly simplistic relation between bifurcation of commercial life outside and the quiet domain of the residential life inside then gives way to a much more subtle gradation between spaces.

Altogether, each of the elements that constitute the new version of landscape within the project is articulated both spatially and in terms of the its collaborative character. This way, an overall purpose of a neighbourhood can be articulated almost sociologically. Through emergence of event structures and shared civic surface, not only the residents of the neighbourhood but those from outside can start relating to the culture of the emerging area and seeing themselves as stakeholders to its existence

Reflecting on this design-driven research, we would claim that now is the time we as an industry pay serious attention to the role that investment into realm of care can play for our cities. Care in its extended sense can become a strong driver for urban transformation, for formation of life-long neighbourhoods, support of strong intergenerational and intercultural networks. For the purposes of this research, we suggested as a first step to agree on the notion ‘care ecology’ as something that can represent the most broad and rich set of services, therapies, stakeholders and settings that are associated with the word ‘care’ today. And as something that can become an alternative to a traditional approach we see today, when the challenge of creating a care environment is treated as a challenge of designing a single care venue with considerations about its urban potential left aside. We exemplified only part of the goals that can be achieved by means of such approach. They include efficiencies that can be gained by those who become part of the rethought care system. Synergistic opportunities across sectors lead to creation of a wider network of services, where more diverse set of stakeholders and actors are interested in becoming part of it. This leads to varied careers offer, retainment of the local talent base, and generation of new type of residential environments that correspond with the changes in our lifestyles.

All of the ‘textured’ networks of a care ecology constantly reciprocate with the decisions we make with regard to the morphology of our neighbourhoods. We showed how attention to the way areas are organised, to the questions of scale, size, hierarchy, movement, direction become important for choosing tools for its transformation, and finding a key to making its morphology work. We also showed how morphological change is tightly knit with typological reasoning in architecture. Thinking through types allows us not only to boost urban transformation and react to very different meaningful conditions found in our cities but also respond to the shifts we observe in the

way we want to live today. Together, using these tools we illustrated how the purpose of a neighbourhood can be translated as a way of life: when people start to relate to its culture, see themselves as stakeholders to its existence. The work looked into how collectivity can be formed around the notion of care; how our domestic life can be transformed in order to answer important questions about what are we willing to share today, how much we can see patterns of neighbourliness and care distributed across wider urban areas, and how we start forming bottom-up governing systems instead of dispersed ones we see in action today.

When asking the question about a potential location of a new care ecology, we suggested to pay attention to the areas located in the inner periphery in our cities, the ones that traditionally are considered challenging due to their structure, spatial characteristics, and qualities that have to do with ownership, market trends and lack of common vision about their vocation. Areas like this, often found along significant water routes in London, come from an industrial past and present us with conflicts: fabric disrupted by industrial heritage, large scale transport armatures, gaps in scale of the built. An indicative site in one of such corridors was used to show that these parts of the city offer us nevertheless exciting resources and are a valuable alternative for the central city areas exhausted by development pressures and constraints. Broadened understanding of a care ecology as a driver of change, systematic approach to an activity-based landscape, new systems of mobility, and typological tools can give us a key to start looking at the corridor in a more structured way. This way, a dispersed area that is unthinkable today in the context of the traditional care environments, has a potential of becoming a set of well-defined, interconnected care-driven neighbourhoods.

This thesis is not offering a ready-made solution but should rather be seen as a starting point to begin raising questions about what our next steps in requalifying the challenging areas of our cities ought to be. The majority of solutions that we implement today at the post-industrial inner-peripheral areas are not viable enough as they are controlled by the market ambitions and restrictions, and as a result, we tend to only contribute to the disjunctions within this fabric. Unfolding the richness of care ecologies as drivers of urban transformation, we could start taking full advantage of the resources and infrastructure these areas have to offer. Relying on the naturally sub-forming patterns of association, to start building attractive neighbourhoods that cultivate a sense of belonging, shared ownership, and give rise to the civic life of a new quality.

Ábalos, Iñaki. The good life: A guided visit to the houses of modernity. Zurich: Park Books, 2019. Lim, CJ. Food City. Oxford: Routledge, 2014.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio, Martino Tattara. “Production/reproduction: Housing beyond the Family”. Harvard Design Magazine, no. 41 (2015). Accessed April 23, 2022, http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/41/production-reproduction-hous- ing-beyond-the-family.

Balland, Ludovic, Nele Dechmann. Duplex architects rethinking housing. Zurich: Park Books, 2021.

Beundermann, J., Fun, A., & Hill, D. (2018, July 11). Places that work. Centre for London. Re- trieved January 23, 2022, from https://www. centreforlondon.org/publication/places-that- work/.

Borsi, Katharina, Anna Shapiro. “Type, new urban domesticities and urban areas”. Internationale Zeitschrift zur Theorie der Architektur, 24 (38), 151-166. Accessed April 23, 2022, https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/1229979/ type-new-urban-domesticities-and-urban-areas.

Donzelot, Jacques. The policing of families. London : Hutchinson, 1980.

Gameren, Dick van. The Urban Enclave = De Stadsenclave, Rotterdam : NAi Publishers, 2011.

Koolhaas, Rem. “The Generic city”. In B. Mau and OMA. S,M,L,XL. New York: The Monicelli Press (1995), p. 12481264.

Maak, Niklas. “Post-Familial Communes in Germany”. Harvard Design Magazine, no. 41 (2015). Accessed April 23, 2022, http://www.harvarddesignmagazine.org/issues/41/post-familial-communes-in-germany.

Rowe, Colin, Robert Slutzky. Transparency. Basel; Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1997.

Schmid, Susanne, Dietmar Eberle, Margrit Hugentobler. A history of collective living : forms of shared housing. Basel : Birkhauser Verlag, 2019.

Steel, Carolyn. Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives. London: Vintage Books, 2009.

Talling, Paul. London’s lost rivers. London: Random House, 2011.

Ungers, O. M. (Oswald Mathias). The Dialectic City, Milano : Skira, c1997.

Cover and page transitions photos / drawings by author

1. Swim City: Zurich’s Unique Summer Scene. Available at: https://discovery.cathaypacific.com/swim-city-zurichsunique-summer-scene/

2. Le Paysan Urbaine, Paris. Available at: https://www. paris.fr/pages/micro-pousses-et-coup-de-pouce-a-laferme-de-charonne-20-18629

3. Chipperfield Canteen. Available at: https://www. wallpaper.com/lifestyle/dinner-at-daves-chipperfield-architects-canteen-launches-kantine-klub-dinners

4. WMS Boathouse at Clark Park. Available at: https:// studiogang.com/project/wms-boathouse-at-clark-park

5. Drawing by author

6. Google earth

7. Photo by author

22. Drawing by author

23. Drawing by author

24. Photo by author

25. Photo by author

26. Photo by author

27. Photo by author

28. Photo by author

29. Photo by author

30. Drawing by author

31. Drawing by author

32. Drawing by author

33. Drawing by author

34. Drawing by author

35. Drawing by author

36. Drawing by author

37. Am Lokdepot, Berlin, backyard, Photo Archives of Anna Shapiro

38. Am Lokdepot, Berlin, backyard, Photo Archives of Anna Shapiro

39. Am Lokdepot, Berllin. Available at: https://live.staticflickr.com/1669/25351308793_739bfd91df_b.jpg

40. Central London Almshouse, WWM, ground floor plan. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/780345/ central-london-almshouse-promotes-sociability-for-the-elderly

41. Central London Almshouse, WWM, ground floor plan. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/780345/ central-london-almshouse-promotes-sociability-for-the-elderly

42. Central London Almshouse, WWM, ground floor plan. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/780345/ central-london-almshouse-promotes-sociability-for-the-elderly

43. Home for Dependant Elderly and Nursing home, Dominique Coulon and associates. Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/794834/home-for-dependent-elderly-people-and-nursing-home-dominique-coulon-and-associes

44. Home for Dependant Elderly and Nursing home, Dominique Coulon and associates. Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/794834/home-for-dependent-elderly-people-and-nursing-home-dominique-coulon-and-associes

45. Peter Rosegger Nursing Home. Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/565058/peter-rosegger-nursing-home-dietger-wissounig-architekten

46. Peter Rosegger Nursing Home. Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/565058/peter-rosegger-nursing-home-dietger-wissounig-architekten

47. Belle Vue Senior Residence, Morris and Co. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/922550/belle-vue-senior-residence-morris-plus-company

48. Belle Vue Senior Residence, Morris and Co. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/922550/belle-vue-senior-residence-morris-plus-company

49. Belle Vue Senior Residence, Morris and Co. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/922550/belle-vue-senior-residence-morris-plus-company

50. Home for Dependant Elderly and Nursing home, Dominique Coulon and associates. Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/794834/home-for-dependent-elderly-people-and-nursing-home-dominique-coulon-and-associes

51. Peter Rosegger Nursing Home. Available at: https:// www.archdaily.com/565058/peter-rosegger-nursing-home-dietger-wissounig-architekten

52. Drawing by author

53. Drawing by author

54. Drawing by author

55. Homes for Senior Citizens, Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner AG. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/ Cm3YHoNs3Y_/?hl=en

56. Homes for Senior Citizens, Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner AG. Available at: https://zumthor.org/project/ masans/

57. Homes for Senior Citizens, Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner AG. Available at: https://www.atlasofplaces.com/ architecture/homes-for-senior-citizens/

58. Homes for Senior Citizens, Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner AG. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/85656/multiplicity-and-memory-talking-about-architecture-with-peter-zumthor

59. Homes for Senior Citizens, Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner AG. Available at: https://www.archdaily. com/85656/multiplicity-and-memory-talking-about-architecture-with-peter-zumthor

60. Drawing by author

61. Drawing by author

62. Drawing by author

63. Drawing by author

64. Drawing by author

65. Drawing by author

66. Drawing by author

67. Drawing by author

68. Drawing by author

69. Wohnprojekt, Einszueins architects. Available at: https://www.simonprize.org/co-housing-wohnprojekt-wien/sheet/

70. Spreefeld cooperative project, Carpaneto Architekten + Fatkoehl Architekten + BARarchitekten. Available at: https://assemblepapers.com.au/2020/03/16/living-labs-for-housing-co-operatives-reinvented/

71. Musikerwohnh aus, Buol and Zund architects. Available at: https://basellive.ch/blog/hauser-gucken/utdd

72. Mehr als Wohnen cooperative project, Zurich. Available at: https://docplayer.org/168252648-Wohnen-leben-arbeiten-im-hunziker-areal-in-zuerich.html

73. Riffraff 3+4, Meili, Peter & Partner & Staufer & Hasler. Available at: https://www.atlasofplaces.com/architecture/ riffraff-34/

74. Java island, Diener and Diener.

75. Drawing by author

76. Drawing by author

77. Swim City: Zurich’s Unique Summer Scene. Available at: https://discovery.cathaypacific.com/swim-city-zurichsunique-summer-scene/

78. Nordhavn district in Copenhagen, Cobe architects. Available at: https://cobe.dk/place/nordhavn

79. Urban farming in Copenhagen. Available at: https:// www.wonderfulcopenhagen.com/wonderful-copenhagen/ international-press/urban-farming-copenhagen

80. Le Paysan Urbaine, paris. Photo Archives of Anna Shapiro

81. Micro-pousses et coup de pouce à la ferme de Charonne. Available at: https://www.paris.fr/pages/ micro-pousses-et-coup-de-pouce-a-la-ferme-de-charonne-20-18629

82. OmVed gardens, Available at: https://collectiveworks.net/2018/07/18/fundraising-at-omved-gardens/

83. Lido, Bristol. Available at: https://www.visitengland. com/experience/live-good-life-lido-bristol

84. Drawing by author

85. Drawing by author

86. Drawing by author