MUSIC ISSUE

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

It is Spring of 2023 and it is my fourth year writing for Inkwell. In my time here, I have seen this organization undergo a lot of change: I’ve seen it struggle, adapt, and grow. One such adaptation that Inkwell developed this year was learning to follow where our passions lead us.

It can, at times, be difficult to keep up morale. Inkwell is no small time committment. However, despite the constant ups and downs of the academic school year, of their other extracurricular commitments, our Inkwell staff has always remained enthusiatic and dilligent about their work here. We have learned to cultivate a good balance between the social and work aspects of Inkwell. Part of this, of course, is making sure that writing for Inkwell never feels like a chore. This is why we learned, as I said, to follow our passions.

We opened this year with the Kitchen Sink Issue: an opportunity for all of our writers to report on whatever they found most interesting. While we had our qualms about such a loose, unprecedented theme for an issue, the Kitchen Sink Issue ended up containing some of the most vibrant, in-depth articles I’ve ever encountered. I realized then how important it was that all of our writers had been truly excited about what they were working on. Their devotion and excitement could be felt through the inked letters.

From this point on, I decided that Inkwell would simply go where our curiosities led us. Brainstorming ideas for our next issue, while lots of lucrative and interesting ideas were thrown out, it was quickly clear that everyone had something to say about music: about their favorite artists, about the industy, and so much more. People were brimming with design and article ideas. And so, we dove right in. In your hands, now, is the product of months of creativity, months of researching, writing, editing. This issue is something we truly poured our best and hardest work into. On behalf of the entire Inkwell team, I am proud to present the Music Issue.

Sincerely,

Sofia Guerra Editor In ChiefMARCH 2023

827 North Tacoma Avenue Tacoma, WA 98403

inkwell@aw.org | 253-272-2216

Issue 2 | Volume 64

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Sofia Guerra

DESIGN EDITOR

Erin Picken

STAFF WRITERS

Amelia Hermann-Scholbe

Jack Cushman

Lucy Hall

Zoe Carlisle

Inkwell aims to provide the Annie Wright community with dependable and engaging coverage of school, community and global topics. Inkwell publishes articles of all genres weekly at anniewrightinkwell.org as well as four themed magazines during the course of the school year. Submissions of articles and photographs, correction requests and signed letters to the editor are most welcome. Please email the editors at inkwell@aw.org. All published submissions will receive credits and bylines.

anniewrightinkwell@org

Check us out at Inkwell Radio

Follow us on Instagram

@anniewrightinkwell

GIRLS LIVING OUTSIDE OF SOCIETY’S SH*T

They told us we were girls

How we talk, dress, look, and cry

They told us we were girls

So we claimed our female lives

Now they tell us we aren’t girls

Our femininity doesn’t fit

We’re f***ing future girls

Living outside society’s sh*t

Those are the daunting opening lines from the debut EP by G.L.O.S.S. (Girls living outside of society’s sh*t), a trans-feminist hardcore punk band based out of Olympia, Washington. Consisting of members Sadie “Switchblade” Smith on vocals, Jake Bison and Tannrr Hainsworth on guitar, Julaya Antolin on bass and Corey Evans on drums, G.L.O.S.S. quickly skyrocketed to popularity in early 2015 with the release of two EPs, Demo and Trans Day of Revenge.

Originally from Boston, Smith grew up going to hardcore punk shows in her area. The genere of Punk is an umbrella term, stretching over a wide range of subgeneres. Popular bands that fall into this category are Black Flag, The Misfits, Bikini Kill, and the Talking Heads. There are a varied group of ideologies associated with punk subculture. Concepts like mutual aid, equality, free-throught and non-conformity. A main tenet is the rejection of mainstream, corporate mass culture and its values. These ideologies are expressed through music and lyrics.

At the time, almost all of the people in the bands and in the audience consisted of middle class, cisgender straight white men. Smith felt the content of the music did not reflect the real issues

of people in the margins of the scene, such as people of color or the LGBTQ community. G.L.O.S.S. was formed in reaction to that lack of representation and diversity. In a retrospective article from KEXP covering G.L.O.S.S.’s iconic discography, the band’s mission and content were perfectly explained:

“Packed tightly into five songs, the eight-minute EP was like throwing an M-80 into a glass house with its powerful songs of rejecting validation from the straight boy canon and trendy mutant skinheads; decrying the performance of masculinity; crafting incendiary anthems for transfemmes, genderfluid folks, and outcasts tired of standing in the back of the venue. Spiked baseball bats beating down the structures of repression and the closets the straight white establishment force trans and nonbinary people into. Trans people being the targets of straight male bigotry and oppression. Supported by pummeling instrumentation and Sadie’s barbed wire-shred-

ded screams, the G.L.O.S.S. demo was a homicidal rebuke of transphobia and all its disgusting sub ideals.”

From songs like the wild, mosh-inducing “Masculine Artifice” to the all-out vengeful “Targets of Men,” G.L.O.S.S.’s message never subsides. Wailing guitars rip through each track as Smith’s words bleed into your ears like a battle cry. In both EPs, the influence of the Boston hardcore sound circa 2002 that Smith grew up listening to resounds throughout each song, made complete with sludging bass and crashing drums to which anyone listening could lose their mind. However, Smith makes it known that her music is not catered towards just anyone (read: cis men), as stated in their song “Outcast Stomp,” “This is for the outcasts/rejects/girls and the queers/for the downtrodden women who have shed their last tears/for the fighters/psychos/freaks and the femmes/for all the transgender ladies in constant transition.” In this song,

Smith is speaking to the people that are usually pushed to the back of the venue, or maybe to her younger in-thecloset self, growing up in the scene. Nevertheless, it’s a positive message that she might have needed to hear back then, a message long overdue for people finding themselves on the fringes of the scene. G.L.O.S.S. aimed to put these people front and center. “I consistently feel bowled over by the positive reaction to the demo” said Sadie in an interview with B*tch Media in 2015. “I have been brought to tears many times from letters, emails and conversations at our shows with other queer and trans folks who have been impacted by our songs… I think for trans women to be honest about their lives there [will] be a lot of pain

and a lot of sh*t to dig up. Singing in G.L.O.S.S. is kind of like getting to be a superhero, like weaponizing a lifetime of anguish and alienation.”

G.L.O.S.S. disbanded in 2016 after turning down a record deal with Epitaph Records due to the label’s affiliation with Warner Bros. The band did not wish to contribute financially to a large cooperation. Soon after announcing this decision, the band also announced via a statement to Maximum Rock and Roll that they decided to bring the band to an end. The reason for this was the mental and physical strain that the members endured from being in the band that had begun to take a toll on their personal growth, home lives and community involve-

ment. The statement also explained that the buzz around the band and the polarizing effect that it had on people was beginning to overshadow the band itself, and that this was not a healthy position for the band and its members. The members donated all proceeds from their records to a homeless shelter in Olympia, Washington called Interfaiths Works Emergency Overnight Shelter.

Despite the band’s short life, G.L.O.S.S.’s impact on the punk community will forever be prevalent. The work they did in creating a safe environment for trans women to express themselves through music was revolutionary.

THE NOSTALGIC INFLUENCE OF

80’S MUSIC OVER GEN-Z Lucy Hall

The majority of teenagers’ tastes in music are dependent on media trends. However, amidst modern media’s ever-changing phenomenon, certain music does not seem to fall out of style. Commonly re-surfacing in the top charts, 80s music has a particular way of lingering in popularity. From Micheal Jackson to Kate Bush and The Smiths, the world of 80s music continues to remain prominent in the mainstream today.

It is well known that TV shows and social media greatly influence how teenagers are introduced to 80s songs. Stranger Things, for example, re-introduced 80s music and aesthetics into the conversation for Gen-Zers. But beyond all of this, the question must be asked; why are teenagers nowadays drawn to music that is generationally irrelevant to them? The motives behind attraction to these styles go beyond the trend.

Nostalgia acts as an anchor for the static nature of 80s music’s relevance. Although teenagers now were not born into that generation, an affinity for the time is still predominant in their lives. Whilst this nostalgia partially originates in individuals, much of it stems from their parents. While many may not realize it, a parent’s upbringing and personal music preferences can affect their children’s tastes and what they’re drawn to. A study published by NPR and written by Nancy Shute writes, “research has found that the music heard in late adolescence and early adulthood has the most impact and staying power through a person’s life.”

exact lyrics of songs heard at an early age may not stick, simply hearing the sound creates an association and can later evolve into a source of nostalgia for the listener...Nostalgia plays an enormous role in everyone’s life, but is unique in the way it grants space for people of all ages to reminisce or simply reimagine. Music from the 80s, specifically, can act as an outlet for teenagers to romanticize a life that could have been. This nostalgia acts as a form of escapism for teenagers to explore a life they didn’t get to have.

The relevance of old music is stoked by the feelings it evokes that modern music does not. Many songs simply encapsulate carefree fun, but others express vulnerability in ways that modern songs and artists cannot express with the same volume due to the normalized culture of expressing sentimental issues in modern music. However, the vulnerability in music now does not have the same effect. A primary goal of modern music is to have high relatability, so a common theme in music is to write about things that the listener can relate to. However, when so commonly focused on, the theme loses its significance due to the repetitive sentiment. Rather than focusing on presenting a true and vulnerable story for the pure purpose of success, older music was original in sharing authentic situations that listeners could relate to due to the veracity and authenticity.

vulnerability encapsulated within their songs is evident and poignant. Whereas the song “Chicago” by Micheal Jackson has made a reappearance in trends due to the iconic nature of its singer and the feel of the song. Another example is the song “Running Up That Hill” by Kate Bush, a song popularized by the sensational Netflix show Stranger Things. This song is a perfect example of the romanticized life of teenagers who didn’t get to experience life in the 80s. The association with this song, of course lies, with the show Stranger Things. Like the show, which has played a pivotal role in n re-introducing the nostalgia felt with 80s culture, the song gives teenagers room to live as their own 80s character. The iconic and heartfelt nature of all of these examples is what steadies their relevance in teenagers’ music tastes today.

A large part of this article has been the repeated theme of nostalgia. “The term ‘nostalgia’ is derived from the Greek words nostos (return) and algos (pain). The literal meaning of nostalgia, then, is the suffering evoked by the desire to return to one’s place of origin.” The “pain” element of origin may come as a surprise, but romanticizing past generations acts as a major source of escapism for teenagers today. This could be escapism from pain or a desire to return to a seemingly more fun area of time.

A myriad of musical nostalgia stems from memories 80s-born adults have including their childhoods and associations with specific songs. Though the

For example, many Smiths songs such as, “There is a Light that Never Goes Out,” “This Charming Man,” and short sections of a few others have been extremely popular on social media platforms, predominantly TikTok. The Smiths have an authenticity that not many artists now possess. Their music is not just about heartbreak, but about depression and realness. The

The culture in which many teenagers’ parents grew up still in some way feels like home to kids today. Although everyone romanticizes past generations, the 80s seem to have a lasting impact on this generation. The pain and pure fun depicted in the songs speak volumes to audiences today because of their authenticity.

WHAT MAKES SCARY MUSIC SO SCARY?

A film’s soundtrack is a key catalyst for the emotions the film evokes in a viewer. Music can convey feelings of joy, heartbreak, hope and even terror. This practice is far from unscientific, though, and has a long history – from the church to the big screen, music for the purpose of scaring its audience has been both condemned and used by artists for hundreds of years.

The tritone, colloquially known as “the devil’s interval,” is a musical element that is commonly employed by composers to induce feelings of unrest in their listeners. It was nicknamed this because it was feared in the Middle Ages that if monks were to sing it, the Devil would hear it as an invitation for him to appear before them. During the development of music in the Middle Ages, the Church of England believed that the purpose of music was to bring glory to and express the majesty of God, and therefore music that was not considered to be “beautiful” was disapproved of and banned from religiously significant sites. Therefore, so-called “false music” was considered to be abject and unnatural during these times. However, as music became more accessible to peasants, the aforementioned correlation between holiness and music dissipated. Over the years, people began to use music in different contexts – for dance, political expression, media and more.

The tritone is a simple example of dissonance – the existence of tension between a given combination of notes or tones which are being played; the absence of consonance. Uses of

Erin Pickenthis type of chord include the opening phrases of Camille Saint-Saën’s “Danse Macabre” (“Dance of Death,”) and Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze,” both of which utilize A/Eb intervals. An extremely well known non-tritone example of dissonance in music is the main theme of Jaws, where John Williams masterfully conducts a combination of minor chords and nonlinear sounds to create suspense.

Dissonance is used in many genres of music within many different contexts. Suspended chords are often used to create musical tension and can be resolved into normal chord tones, such as tonic chords. The difference between, say, a major third chord and its suspended chord is the lowering of the third note in the chord by one whole step. A suspended chord can also be created from a tonic chord by the addition of an unnecessary note which prevents the pure tonic from being expressed consonantly. For example, the first two chords of Tom Petty’s “Free Fallin’” are an F major chord (F, A, C) and an Fsus4 chord (F, Bb, C.) These can all be resolved with one change (or removal) of notes.

When a dissonant interval is played, people find it unsettling because it is unresolved: people want it to move from dissonance to consonance smoothly. Many musicians who hear dissonant chords can easily play or hum the consonant ones due to the common motif of movement from one to the other in classical music from the Baroque and Renaissance eras.The positive association with consonance

and the negative association with dissonance in the West does not have one clear-cut explanation.

One musicological explanation for these associations suggests that it has to do with frequencies. According to research conducted by Harvard neurologist Mark Tramo, sound waves created by consonant intervals are smooth and regular, while waves created by dissonant intervals are jagged. While this explains the mathematical differences between the types of music and the ways in which the brain receives them, it fails to explain why some people genuinely enjoy music that employs dissonance or is entirely atonal, while others do not. A common theory is that some people enjoy predictable patterns of tonal music which lacks the tension created by dissonance, while others enjoy the unpredictability of music which either does not have a resolution or forces the listener to wait for it. This plausibility explains why people from different musical cultures prefer music with different structures and amounts of tension – for instance, people enjoy genres ranging from Romantic era classical music to grunge and heavy metal.

The evolution of music over the centuries has provided society with essentially unlimited ways by which musicians can evoke certain emotions in their listeners. As long as musicians continue to be innovative in their composition and performance of new music, the unpredictable nature of dissonant music can be used for a myriad of purposes.

Annie Wright Schools initiated the Music Laureate program in the 20192020 school year. This program, designed to gather a cohort of passionate music students, provides selected participants with mentorship as they develop two to three “new-to-you” pieces to perform at a capstone concert. Inkwell obtained interviews with a handful of the 2023 Laureates about their projects and processes.

Sofia Guerra - Sofia Guerra (USG ‘23) is translating, recomposing, and performing popular Korean R&B, indie, and ballad music for her Music Lareaute project. Although she is not a native speaker, Guerra, connecting with her Korean heritage, fell in love with different genres of Korean music in the beginning of her highschool career. At first, it wasn’t about the words or phrases she didn’t fully understand, but the feeling and mood of the pieces. It was about the story being told, the drama unfolding, and the beauty being expressed. As she learned more of the language, however, she also noted the additional impact exactitude of lyrics carried. Through her project, Guerra has decided to translate a selection of Korean songs and hopes to be able to

show the audience that same beauty the works have in their original language.

Ariel Lai - Ariel Lai (USG ‘24) is learning the first movement from Bach’s Partita II in D minor and Reflection from the Disney movie Mulan for her Music Lareaute. Lai, a violinist, wants to reignite her love and passion for classical composition and the artform of string instruments. She wants to explore technical expertise through the complex and challenging Bach piece, tackling different skills and musical deliveries. After a long absence from the stage, Lai also hopes that her performance will bolster her confidence in front of audiences along with providing her an opportunity to hone her craft.

Andrea Gyimah - Andrea Gyimah (USG ‘25) is performing three songs for her Music Lareaute project, accompanied by Mr. Orr on the piano. Gyimah began her singing career at a young age, originally performing in church choir, then with the Chicago Children’s Choir, is now taking frequent vocal lessons in hope to expand and perfect her vocal range. A pop fan

at heart, Gyimah will be performing songs by Adele and Cynthia Erivo. She is a long-time fan of both of these artists’ composition and vocal performances. Through this project, she hopes to grow more comfortable performing in front of audiences. Gyimah sees the Music Lareaute concert as a healthy opportunity to take a risk and bolster her confidence, as well as gain more experience.

EJ Carei - EJ Carei (USB ‘24) is performing pieces by Chopin and Bach for his Music Lareaute project. From a young age, Carei has held a love for music and the piano and wishes to prove his skill in front of an audience. Ever since his introduction to the instrument, Carei has been entranced by the scale of performances possible with it. With such a vast array of notes, there is almost infinite opportunity for melodies and songs. Carei views the piano as a complex craft that he hopes to gain understanding and mastery of. Carei holds music close very to his heart, and wishes to share his love with all those who hear it. Through his Music Laureate performance, he intends to do just that.

PREVIEWING THE ‘23 ANNIE WRIGHT MUSIC LAUREATES

HOT TOPIC: THE 2023 GRAMMYS

The 2023 Grammys gave rise to significant controversy in three main categories: album of the year, song of the year, and best new artist. Inkwell surveyed the Annie Wright upper schools in order to figure out whether the awards given aligned with the opinions of the student population.

Erin Picken

Album of the year WINNER: Harry’s House by Harry Styles (18.8%)

Voyage by ABBA (12.5%)

30 by Adele (6.3%)

Un Verano Sin Ti by Bad Bunny (12.5%)

RENAISSANCE by Beyonce (9.4%) In These Silent Days by Brandi Carlisle (3.1%)

Music of the Spheres by Coldplay (3.1%)

Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers by Kendrick Lamar (28.1%)

Special by Lizzo (6.3%)

Good Morning Gorgeous by Mary J. Blidge (0%)

Song of the year WINNER: Just Like That by Bonnie Raitt (0%)

About Damn Time by Lizzo (6.5%)

All Too Well (10 Minute Version) by Taylor Swift (48.4%)

As It Was by Harry Styles (12.9%)

Bad Habit by Steve Lacy (6.5%)

BREAK MY SOUL by Beyonce (3.2%)

Easy on Me by Adele (12.9%)

GOD DID IT by DJ Khaled (6.5%)

THE HEART PART 5 by Kendrick Lamar (3.2%)

abcdefu by GAYLE (0%)

Best new artist WINNER: Samara Joy (0%)

Anitta (16.1%)

Omar Apollo (35.5%)

DOMi & JD Beck (6.5%)

Muni Long (3.2%)

Latto (6.5%)

Maneskin (22.6%)

Wet Leg (9.7%)

Molly Tuttle (0%)

Tobe Nwigwe (0%)

FOLK MUSIC: AN UNEXPECTED INSTRUMENT OF SOCIAL JUSTICE Erin Picken

Music and social justice have been long intertwined. Throughout history, musicians have used their platforms to advocate for social justice issues such as civil rights, environmentalism, anti-war activism and misogyny. This method of activism has the potential to reach individuals who would otherwise never be inspired to seek to become educated about political issues and promote real change by doing so. In addition, this emotionally charged and socially relevant music often inspired listeners to educate themselves and make their own music. This article will highlight musicians who wrote political music and those whom they inspired: Woody Guthrie, to Bob Dylan, to Johnny Cash.

Woody Guthrie:

Woody Guthrie was the author and original singer of the classic American folk song “This Land is Your Land,” sometimes called the unofficial American national anthem. Throughout his career, Guthrie pushed socialist and anti-fascist messages to his fellow Southern Americans and beyond. Guthrie was a founding proponent of music being used as a method of protest, often playing a guitar with the slogan “this machine kills fascists” on it. His passion for activism began when he was forced to look for work in California, leaving his family in Oklahoma, by the dust storm events of the 1930s. There, he became educated about the occurrences of lynchings in the South which he believed his father had participated in as a member of the Ku Klux Klan and frequently participated in the communist circles of Southern California. His music career was tempo-

rarily halted when he released a song that praised the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland. This prevented him from airing much of his music over the radio until his 1940 release of “This Land is Your Land,” a communist anthem that was, ironically, heralded instead as an anthem that highlighted America’s provision of freedom to its people in the midst of the Second World War.

Bob Dylan:

Inspired greatly by Woody Guthrie, folk/rock musician Bob Dylan aimed to push the civil rights movement through his music by writing lyrics that addressed issues such as racial inequality and police brutality throughout the 1960s. Dylan’s folk career began in New York City’s Greenwich Village, which was then an epicenter of folk music and political consciousness which provided many performers with a setting in which they could share their music and make money. Widely considered to be his first protest song, Dylan wrote “The Ballad of Emmitt Till” in 1962. The ballad aimed to honor Till, a Black child from Mississippi who was kidnapped, tortured and lynched in 1955 after he was accused by a white woman named Carolyn Bryant of whistling at her. Bryant later admitted that she had been lying. Following the success of the ballad at a Congress of Racial Equality benefit, Dylan continued to write politically charged music: “Let Me Die in My Footsteps” (critiquing American Cold War hysteria), “Paths of Victory” (pushing for the continuation of marches for civil rights), “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” (warning of the consequences of potential nuclear

war, which premiered at Carnegie Hall a month before the Cuban missile crisis), and many more.

Johnny Cash:

While Johnny Cash’s admiration of Bob Dylan’s work is often cited by referencing his cover of Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me, Babe” on his 1964 album Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian, the influence didn’t stop there. Many of Cash’s political works were shaped by the genres and political issues that Dylan most often engaged with. Cash believed in the power of music to not only influence the ignorant but to raise the hopes of those oppressed by the situations he sang about. He wrote “Singing in Vietnam Talking Blues” after having the opportunity to perform for troops deployed during the Vietnam war and famously performed twice for prisoners at California’s Folsom State Prison in 1968, playing songs including the timelessly popular “Folsom Prison Blues.”

This type of music remains useful even after its prime: the common phrase “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it” rings true, and this music can help us remember. While the specific songs mentioned in this article were all written between 1939 and 1964, many of these issues remain relevant today – from potential impending nuclear war to the existence of racial inequality both inside and outside of America’s prison system, these are issues we not only need to remember but pay attention to as they continue to happen today.

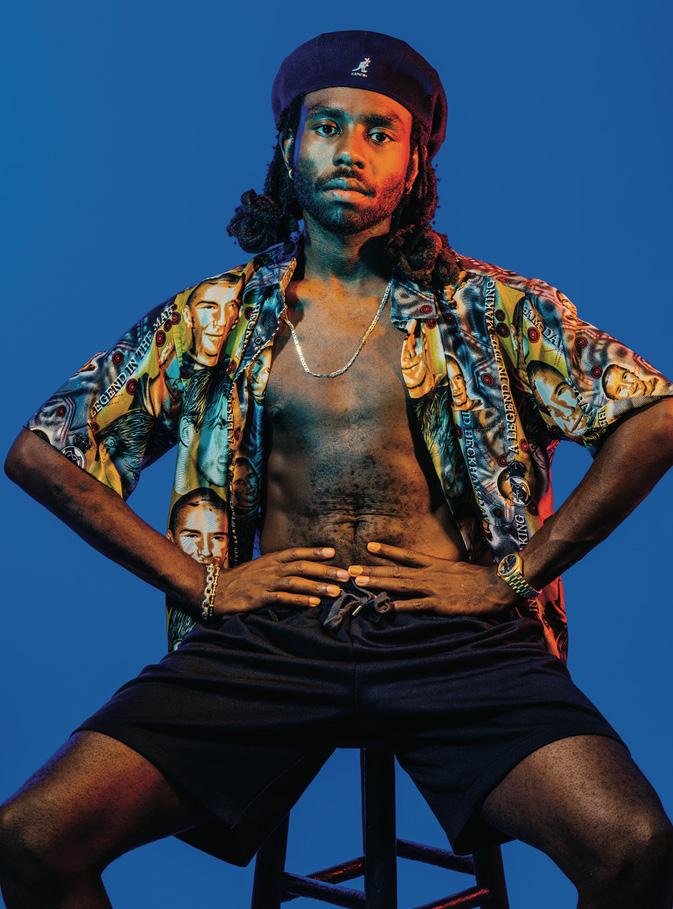

For the past 3 years, Blood Orange has consistently remained one of my most listened-to artists, and for a good reason. This unbelievably talented and multi-faceted musician crosses several musical styles such as R&B, soul, funk, post-punk, chillwave and indie rock, all laced with his dreamy and beautifully melancholic falsetto. He explores a variety of lyrical themes within his music like identity, relationships, sexuality, belonging and spirituality, and how these things shape his existence and that of his peers.

Born and raised in Ilford, East London to a Guyanese mother and Sierra Leonean Creole father, English singer, songwriter and producer Devonté Hynes (stage name Blood Orange) first came into the music scene in 2004 as a member of the indie rock band Test Icicles. After moving to the US in 2007, Hynes released two solo studio albums under the name Lightspeed Champion. This first solo venture into Hynes’s experimentation with the type of indie R&B jazzy-electronica sounds that he would later become known for, morphed into his best-known moniker, Blood Orange. Under this name, he has produced a total of five albums as well as scattered E.P.s and singles all between 2008 and 2022.

Despite the deeply personal and individualistic nature of all five albums, Blood Orange’s evolution can be mainly attributed to collaboration. Hynes is highly sought out and has featured, written, produced and played for notable artists such as FKA Twigs, Solange Knowles, Steve Lacy, Florence + the Machine, Mac Miller, and more. Hynes

also has dipped into scoring films with movies like Palo Alto (2013) and Queen & Slim (2019).

Blood Orange’s debut album Coastal Groves (2011) introduces the groundwork for his music with a plucky, indie pop adjacent that screams “main character energy.” Coastal Groves is the perfect soundtrack for night drives through the city, with each song capturing the pure essence of teenage angst. From the enigmatic and fastpaced beat of “I’m Sorry We Lied” to the romantic yet vengeful “Are You Sure You’re Really Busy,” much of his music radiates a moodily nostalgic, longing feeling. The final track, one of Blood Orange’s most popular songs titled “Champagne Coast” feels atmospheric, with Hynes’s hazy vocals flowing through the song like something out of a dream. This debut album introduces the type of demonstrative and emotionally engaging sounds that define Blood Orange. My favorite song off this album would have to be “Champagne Coast” (a given) due to the versatility of sounds, and genres incorporated. I get goosebumps every time I hear the ambient keyboard swell and catchy hooks of what is in my opinion, a musical masterpiece. If you enjoy this album, I also recommend giving the album 6 Feet Beneath The Moon by King Krule a listen. Both albums implement an indie guitar style and unique singing.

Following Coastal Groves, Cupid deluxe (2013) is Blood Orange’s progression into funky new wave and contemporary R&B, still keeping that familiar indie pop feel. The effect of

genre blending is dizzying and comforting all at once. Similar to the content of his debut album, these 80s-inspired odes move through themes of heartbreak and longing, especially as they attain to LGBTQ+ youth. The track “Uncle ACE” refers to the ACE subway line in New York, which runs from the top of Manhattan to the bottom of Queens, nicknamed “Uncle Ace’s house” by youth who found refuge from unaccepting home environments within the subway lines. In this impressionistic album, Hynes switches between a low and high singing voice, subtly accentuating the androgynous characters within himself. It feels mysterious, desperate, and empathetic. Hynes shines a light onto vulnerable subjects, showcasing them inhabiting their travails of prejudice with grace and poise, all while a dance-worthy disco pulse plays in the background. Songs off this album that I recommend listening to include “You’re Not Good Enough,” “It Is What It Is” and “Time Will Tell.” And if you enjoy the indie new wave style heard in this album, the album Street Desires by Gap Girls implements a similar sound and I highly recommend giving a listen.

Negro Swan, Blood Orange’s fourth studio album released in 2018 is by far Hynes’s most popular, influential and collaborative piece of work to date. Negro Swan is a restless jazzy slow jam that starts as a spoken-word poem and ends as a languid rap with sprinkles of synth and electro-R&B throughout. Made complete with contributions from the gospel singer Ian Isiah and verses from rapper A$AP Rocky. In this album, Hynes wanted to express

DARK AND HANDSOME: THE BEAUTY OF BLOOD ORANGE

themes of isolation, loneliness and displacement, especially as they pertained to race; he wanted to get at what he calls “the different weight of life” for marginalized people, “how it’s tackled and how you live with it.” He uses a curated sound to tell a story about memories that still haunt him and thoughts that plague him, still while clinging to a hope of a brighter future. “The underlying thread through each piece on the album is the idea of hope, and the lights we can try to turn on within ourselves with a hopefully positive outcome of helping others out of their darkness.”

Part of Negro Swan’s influence stems from its specificity. The album’s opener “Orlando” tells the story of Hynes being bullied throughout his childhood and adolescence, comparing the experience to something that should be magical: “First kiss was the floor,” he sings. The juxtaposition between something so violent yet so intimate shows the ways in which the traumas we experience in our lives can poison our innocence and sincerity from a young age. The depth, softness and warmth of the instrumentation emphasize the masking of the horrors we experience. Negro Swan unequivocally understands the authentic and humane nature of heartbreak and longing. mewhat easy to write, but there’s a sort of bravery in the amount of vulnerability it takes to admit that you have tasted love, but could not hold onto it through your own faults. Expressing these difficulties in combination with the overall existential crisis of just simply existing is threaded throughout Negro Swan.

Coming in at over eighty million streams, Blood Orange’s most popular song “Charcoal Baby” tackles the microscopic feeling of having to

represent oneself in one direction to justify one’s worth in another, Hynes sings “No one wants to be that odd one out at times/No one wants to be that negro swan/Can you break sometimes” over the almost eerie synth drone and stripped down beat. Negro Swan shares similar connections to Frank Ocean’s Blonde. Both albums perfectly capture melancholy in similar fashions, implementing experimentation with vocals, warped guitars and midi keyboards. The overlapping concepts addressed in both albums are nothing short of breathtaking.

My personal favorite song off Negro Swan is “Dagenham Dream,” which feautres a clip of Janet Mock, an American writer, director, producer and trans rights activist speaking on belonging and her struggles with identity at the end of the song. “Growing up I have always heard, or I was always hyperaware of the things that the people around me who were charged with my care or told me, be silent or be quiet or be ashamed or hide or perform a version of myself that wasn’t really me. And so, I think that through my life I’ve always been hyperconscious and aware of not going into spaces and seeking too much attention. Because part of survival is being able to just fit in, to be seen as normal and to ‘belong’ but I think that so often in society in order to belong means that we have to shrink parts of ourselves.”

Each song on this album pertains to a certain human experience. That is one of the main things I truly admire about Devonté Hynes’s music. He takes his life experiences and turns them into art, thus creating incredibly complex works that almost anyone can relate to, find comfort in, or simply enjoy.

MORE THAN SINGING AND DANCING: THE POLITICS OF KOREAN POP MUSIC

Sofia Guerra

What is Korean Popular music, or K-pop? In recent years, the industry has grown exponentially, affecting every aspect of Asian and Western pop culture. From the feature of “K-pop trolls” in the Justin-Timberlake starring animated film “Trolls 2” to rookie group Aespa’s appearance before the United Nations, K-pop has come to infect all aspects of modern society. Everywhere you look, it seems that K-pop is there in its vibrant, sparkly glory. In this article, Inkwell sat down with Dr. Inkyu Kang, Associate Professor of Digital Journalism at Penn State. Professor Kang is lauded for his 2015 book predicting the rise of K-pop into mainstream Western media. Inkwell interviewed Kang about his opinion on the history, current events, and future of the juggernaut music industry.

Inkwell: Can you describe how K-Pop has evolved and changed over time, especially in recent years?

Kang: The popularity of Korean pop culture didn’t come out of nowhere; it has evolved gradually as a global phenomenon for the last few decades. It was the late 1990s when I started to feel the growing popularity of South Korean popular culture outside Korea. I came to the United States as a student in 1999, and on campus I met several Chinese students talking passionately about a Korean television drama. The TV series — “What Is Love?”— was aired on China Central Television in 1997 and watched by over 150 million Chinese viewers. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Korean TV, film, music, fashion and food, as well as Samsung and LG consumer electronics were gaining so much popularity that the Chinese started to call it “Hallyu,” or the Korean Wave.

In 2004, another TV series titled “Winter Sonata” was broadcast on NHK, triggering a massive Korean drama boom in Japan. Lots of the drama fans, notably middle-aged women, started visiting Korea en masse, which was quite unexpected. According to an NHK survey, 90% of the Japanese respondents knew the show and 38% of them watched it. It was around this time when top Korean musicians, such as BoA and TVXQ!, started performing and releasing albums routinely in China and Japan. BoA, dubbed the “Queen of K-pop,” sold over one million copies of each of her first two albums in Japan alone in 2002 and 2003.

The popularity of Korean popular culture spread out outside China and Japan, but the wave was limited to Asian countries until the 2010s. The wave, triggered initially by satellite TV, spread to Japan in the early 2000s, and then to the rest of the world through digital platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and Netflix. Since the pandemic began, many North American and European audiences have turned to Korean TV series on Netflix as welcome distractions—and have become hooked.

Korea’s entertainment has a unique blend of high production value, distinctive style and blistering social commentary, which one can find from Blackpink’s electropop or BTS’ hip hop to Netflix’s sleeper hit “Squid Game,” as well as Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-winning “Parasite.” Until recently, Korean film, TV, and music escaped the attention of the majority of Western media and audiences, leading them to believe that Korean pop culture emerged out of thin air.

Inkwell: How have the foundations of

K-Pop informed the direction it has taken today? Tangentially, what other cultural and social aspects have influenced its development?

Kang: I think that what makes K-pop popular globally, including Europe, is good food for thought. On the surface level, K-pop is a spectacular body of cultural products characterized by catchy rhythms and jaw-dropping dance delivered by attractive pop artists. At the same time, they also get comfort from the social messages in K-pop and enjoy interacting with the performers with unique identities, which they didn’t experience before. For example, male K-pop idols’ images are strikingly different from the conventional rugged, tough-guy masculinity that has dominated Western culture. Many of them are comfortable defining themselves as “kkotminam (flower boy),” wearing makeup, dying their hair, and wearing clothes and making gestures across gender boundaries. Such a practice might make older audiences (and the mainstream media) uncomfortable, but K-pop’s gender fluidity is a selling point for the young counterparts.

The global rise of Korean culture also involves a lot of other things, including global cultural flows, the digital economy, the emergence of the new generations as the dominant cultural consumers and participants. What’s notable is the socioeconomic conditions into which the young generations—millennials and Gen Zers—are born, turning them into “the most progressive generation in history.” Since birth, they have lived under the direct influence of the financial crisis of 2007-2008, the election of the first Black president, Occupy Wall Street, climate change, and #MeToo, Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate movements.

Plus, the young audiences are less racially biased and more open to non-Western culture. They are relatively less biased racially and ethnically, because they have witnessed the economic and cultural influence of Asia. The Millennials and Gen Z are the generations that grew up with a Samsung smartphone and an iPad assembled in China, and they spend most of their waking time on them.

Unfortunately, the future of the youth around the world is clouded with deepening inequalities and job insecurity caused by growth without

employment, labor market flexibility and unregulated, widespread precarious work. They are often referred to as the first generation to earn less than their parents. The growing concern and discontent over inequalities have contributed to the popularity of South Korean films and dramas like “Snowpiercer,” “Parasite” and “Squid Game.” Their critique of class issues has resonated deeply with audiences around the world.

Many K-pop bands, including BTS and Blackpink, talk about issues that matter to their fans, such as their uncer-

tain future, broken heart, bullying and self-hate. Many Korean filmmakers and music producers had developed social awareness under the influence of activism during the 1980s. They happened to be the beneficiaries of the newfound wealth brought by the industrialization dubbed “The Miracle of the Han River,” which gave them opportunities for a good education, travelling overseas and diverse cultural experiences. Since its democratization, South Korea has achieved one of the strongest civil societies in the world, instilling creativity and imagination in the young generations and making the culture sector a desirable career path.

Korean corporations invested heavily in the culture industry after recognizing its economic potential in the late 1990s. However, Korea has always been a cultural mediator between China and Japan in the past, and now it is a cultural mediator between the East and West. Many Koreans experienced Western popular music for the first time during the 1960s and 70s through AFKN (Armed Forces Korea Network), the radio and television network for the military personnel

stationed in South Korea. A lot of budding artists experimented with the rock ‘n’ roll, hard rock, pop, jazz and R&B, incorporating the Western genres into their own music. Some of them gained national popularity while performing regularly at U.S. military bases. Of course, Korean genres, such as trot and pansori, have always been loved by Koreans.

Koreans have gone through tremendous tragedies and hardships, especially since the early 20th century, including the oppressive Japanese rule, separation of families by the division

of the country, deaths and destruction caused by the Korean War, severe famine and destitution that followed, and ruthless iron-fisted rule by military juntas that lasted until the late 1980s. These traumatic experiences have left deep dents in Koreans’ psyche, which they call “han.” This is a collective emotional scar, but it has worked as muse for Koreans as well. Koreans have expressed their han by singing, dancing, writing poetry and novels, and making films. Korean culture has developed its identity through the sufferings.

Inkwell: Can you speak to different types of political power that exist beyond hard, military power? How does K-Pop fit into these structures?

Kang: It seems that some people believe that the South Korean government has grown its culture industry strategically to achieve soft power greatness. Unlike washing machines or military aircrafts, hit shows and platinum-certified albums cannot be churned out through, say, “Five-Year Development Plans.” This misconception seems to have been caused by the seemingly sudden rise of Korean popular culture. However, the Korean Wave had developed for decades and was discovered by European and North American audiences only recently.

As a matter of fact, South Korea has a strong manufacturing and defense base. The Korean government has acted as a guiding hand by laying out the infrastructure, providing funding for research and development and offering tax incentives. The entertainment industry cannot be built this way because people’s cultural tastes and trends are notoriously unpredictable, fickle, and ever-changing. The Korean government seems to enjoy the country’s newfound status in soft power, but Korea’s culture industry has been led predominantly by the private sector. As a matter of fact, Korea’s culture sector started to grow rapidly after it got out of government control with the country’s democratization in the 1980s and the lifting of the decades-old ban on Japanese cultural products in the 1990s —the government had long worried that Japanese pop culture would threaten Korea’s cultural sovereignty.

Now the major players are big and small film studios and music agencies

competing fiercely in both domestic and international markets.

Inkwell: Why do you think K-Pop, over other music industries, has become such an omnipresent force? Specifically, what distinguishes K-Pop from other East Asian popular music industries such as C-Pop and J-Pop? Why has it had such great success?

Kang: I find J-pop and C-pop equally fascinating, but I think that K-pop is more systematized, taking its production value to another level. We can also talk about K-pop as a system or mode of production, such as Motown. For example, Jennie Kim of Blackpink, one of the most popular K-pop bands, said that “what makes K-pop K-pop is the time that we spend as a trainee.” Shi-hyuk Bang, the founder of Big Hit Entertainment (now HYBE) that manages BTS, also said, “K-pop artists, by average artists’ standards, have to show acrobatic-level skills in their performances.” K-pop performers are expected to flawlessly sing and dance at the same time, which requires years of training from a young age—like dancers at ballet schools. Of course, it causes a lot of stress and frustration, because only a very small percentage can successfully debut.

Inkwell: What is your personal opinion on the utilization of K-Pop in international diplomatic relations?

Kang: I don’t support any attempt to use K-pop as a marketing tool to boost the image of a specific country. However, I fully support the collaboration between BTS and UNICEF to end violence and bullying and promote self-esteem. I was also thrilled when Blackpink joined the global fight against climate change a few years ago. K-pop is a global phenomenon; K-pop

stars should care about issues that matter to their global audiences.

Inkwell: Where do you see K-Pop five, ten years down the line? What predictions do you have about its growth (or decline)?

Kang: I that K-pop will maintain its success for a while due to its competitive edge. What makes K-pop K-pop is its training system that requires performers to be equipped with skills that wow the audiences. However, audiences are very fickle and there is no guaranteed way to keep them satisfied.

K-pop has constantly evolved as it globalizes. In the past, entertainment companies tightly controlled their entertainers to maintain the images they had carefully crafted, and some agencies did not allow their stars to communicate directly with their fans. As you see today, however, the success of BTS and Blackpink would not have been possible without a strong bond with their fans. K-pop will keep evolving.

As Kang detailed, K-pop is a rapidly growing industry: an industry of music, culture, politics, and more. The flashy performances with sparkly outfits and impeccably coordinated choreographies are truly only the tip of the iceberg. K-pop tells a intricate story of the struggles and triumphs of both the country of Korea and East Asia as a whole on their journey to global interconnectedness with the West. K-pop is an industry unbounded: what started as music has become a political, cultural, and social upheaval. It will be fascinating to observe how this music industry will continue to grow and develop and just how far its influence will extend.

THE KANYE WEST COLLAPSE: A HISTORY

Kanye West, also known as Ye, is an American rapper, songwriter, and fashion designer. West has 18 million followers on Instagram and over 49 million listeners on Spotify, giving him a huge platform and influence to a large number of people. Prior to his scandals, West released many albums including Graduation, Life of Pablo, and My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. All of them have over a billion streams on spotify. He also owns a very popular shoe brand called Yeezy which he is partnered with through Adias. West makes roughly $220 million dollars annually from Yeezy. In this article, Inkwell dives into some of West’s most impactful controversies.

West vs. Taylor Swift:

Dating all the way back to 2009, when Taylor Swift, singer-songwriter, won best female video award at the VMAs for her song and iconic music video “You Belong With Me”, West stormed the stage, dissatisfied with the results. He took the microphone from Swift and said “Yo, Taylor, I’m really happy for you and I’mma let you finish, but Beyonce had one of the best videos of all time, one of the best videos of all time.” The camera then cut to Beyonce, nominated for her music video for “Single Ladies,” who was visibly mortified

For years, this outburst from West incited lots of backlash. Not only from Swift’s fans but from celebrities like Barack Obama, Katy Perry, and Kelly Clarkson. Many took to twitter to voice their disappointment in West. Later, Swift and West were able to put this incident behind them and become civil with one another. But, this peace wouldn’t last long. When West released his album, “Life of Pablo,” in 2016, it included a song titled “Famous,” featuring the now infamous lyric “I made that b*tch famous,” referring to Taylor Swift and the 2009 VMAs. According to a billboard statement made by a representative of Swift, she never gave West the approval for this lyric. On the other hand, West made the claim that between a phone call of the two of them, Swift pre-heard the lyric and gave him permission to use this line in the portion of the phone call released by West. In 2020, the entire phone call was then released (when only part of it was publicly released prior) proving Swift was unaware of the lyric and West didn’t run it by her beforehand.

West and Controversial Celebrities

In 2021, Kanye West hosted a listening performance for his new album “Donda.” But, during the performance, West brought Marilyn Manson

(who was facing sexual assault allegations) and Dababy (who was being called out for anti-gay comments) on stage with him. Because of this, West received lots of backlash from social media for associating himself with such controversial people. Some people believed this was West’s clapback at “cancel culture,” while others saw this as yet another childish outburtst.

This isn’t the first time West has involved himself with controversial celebrities. Back in 2016, West tweeted “BILL COSBY INNOCENT!!!!!!!!!!” after the comedian Cosby was charged with the sexual assault of over 50 women. Just like the Donda performance, the media expressed their frustration and disappointment, including other comedians Sarah Silverman and Billy Eichner.

West Running for President

Kanye West took to Twitter in 2020 to announce his presidential campaign, tweeting, “We must now realize the promise of America by trusting God, unifying our vision and building our future. I am running for president of the United States! #2020VISION.”

West said that he would be running under the “Birthday Party” for his political party because according to him, “When we win, it’s everyone’s birth-

“When we win, it’s everyone’s birthday.” Unfortunately for West, his presidential dreams came quickly to an end after receiving just 60,000 votes and zero delegates. Only after he put 6 million dollars toward his campaign.

But, this wouldn’t be the end for West. Despite all the controversial incidents he has been in recently, in November of 2022 announced he will be running for president in 2024 and will have former president Donald Trump as his running mate. Because of his recent bans on social media the legitimacy of this announcement is not strong.

Kim Kardashian and Pete Davidson

In 2014, Kanye West and Kim Kardashian tied the knot in Florence, Italy and even had four kids together. But, after seven years of marriage, Kardashian filed for divorce from West in February of 2021. Although they divorced, West and Kardashian seemed to be healthily co-parenting, until Kardashian hosted SNL in October of 2021. After Kardashian’s SNL debut, she started to kindle a relationship with comedian Pete Davidson, an SNL cast member. This didn’t make West happy.

The first attack West made on Davidson was in January of 2022 after he released the song “Eazy.” Which featured the lyric, “God saved me from that crash -Just so I can beat Pete Davidson’s a** (who?).” But this was just the beginning of the harassment that Davidson would receive. Rapper Kid Cudi was long-time friends with both West and Davidson, but, his friendship with Davidson became an issue for West. On February 12th of 2022, West posted a handwritten note on Instagram, stating, “Just so everyone knows Cudi will not be on Donda because he’s friends with you know

who.” Cudi was quick with a response and commented “Too bad I don’t want to be on your album you f*ckin’ dinosaur hahaha everyone knows I’ve been the best thing about your albums since I met you.” West then posted a photo of all of them at Cudi’s birthday dinner from 2019, putting a big X over Davidsons face with the caption, ““I JUST WANTED MY FRIEND TO HAVE MY BACK THE KNIFE JUST GOES IN DEEPER.”

West doesn’t stop there. He then started posting private text messages between Davidson and himself. Davidson told West, “And you as a man. I’d never get in the way of your children. It’s a promise. How you guys go about raising your children is your business not mine. I do hope one day I can meet them and we can all be friends.” West then posted that with the caption “NO YOU WILL NEVER MEET MY CHILDREN.”

Not long after, Kanye uploaded a modified version of Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War, putting himself on the same side as Julia Fox, Drake, Future, and Travis Scott. And on the opposite side having Pete Davidson, Kim Kardashian, Taylor Swift, Kid Cudi, and Billie Eillish. Uncoincedentally, those are all people he has had feuds with. He captioned the post “THE INTERNET HAS STILL NOT FOUND A DECENT PICTURE OF SKETE,” giving Davidson the derogatory nickname, Skete.

Then Kanye tells fans via social media, “IF YOU SEE SKETE IN REAL LIFE SCREAM AT [THE] LOOSER [sic] AT THE TOP OF YOUR LUNGS AND SAY KIMYE FOREVER.”

Kimye refers to the portmanteau of Kim Kardashian and West’s names. Because of this outburst, West re-

ceives a prompt text from Kardashian saying “ U are creating a scary and dangerous environment and someone will hurt Pete and this will all be your fault.” West then posts Kardasihan’s text with the caption “UPON MY WIFE’S REQUEST PLEASE NOBODY DO ANYTHING PHYSICAL TO SKETE IM GOING TO HANDLE THE SITUATION MYSELF.”

Anti-Semitism and Hitler

Just when you thought Kanye West couldn’t get any worse: well, he can. On December 1st, West went on the Alex Jones show and during the interview, West was praising Hitler and the Nazis, saying, “The Jewish media has made us feel like the Nazis and Hitler have never offered anything of value to the world.” This comment put right winged Jones in a difficult position. He tried to get West to backtrack and told him that they also did a lot of bad things. But, that didn’t faze or concern West because he responded, “But they did good things, too. We’ve got to stop dissing the Nazis all of the time.” The same day after the interview, West posted a photo of a swastika on his twitter, which permanently suspended his twitter account.

Because of all of West’s anti-semitic comments, his longtime partner Adidas, with whom he developed Yeezys, announced they were cutting ties with the rapper after almost a decade of working together.

As you can see, Kanye has many problems and can usually find a way to get out of all his controversial scandals. He is seems to be the only celebrity that could get canceled to such an extreme and still have his music be sampled at the Super Bowl.

THE WORKS OF LORDE: A COMING-OF-AGE ACROSS ALBUMS

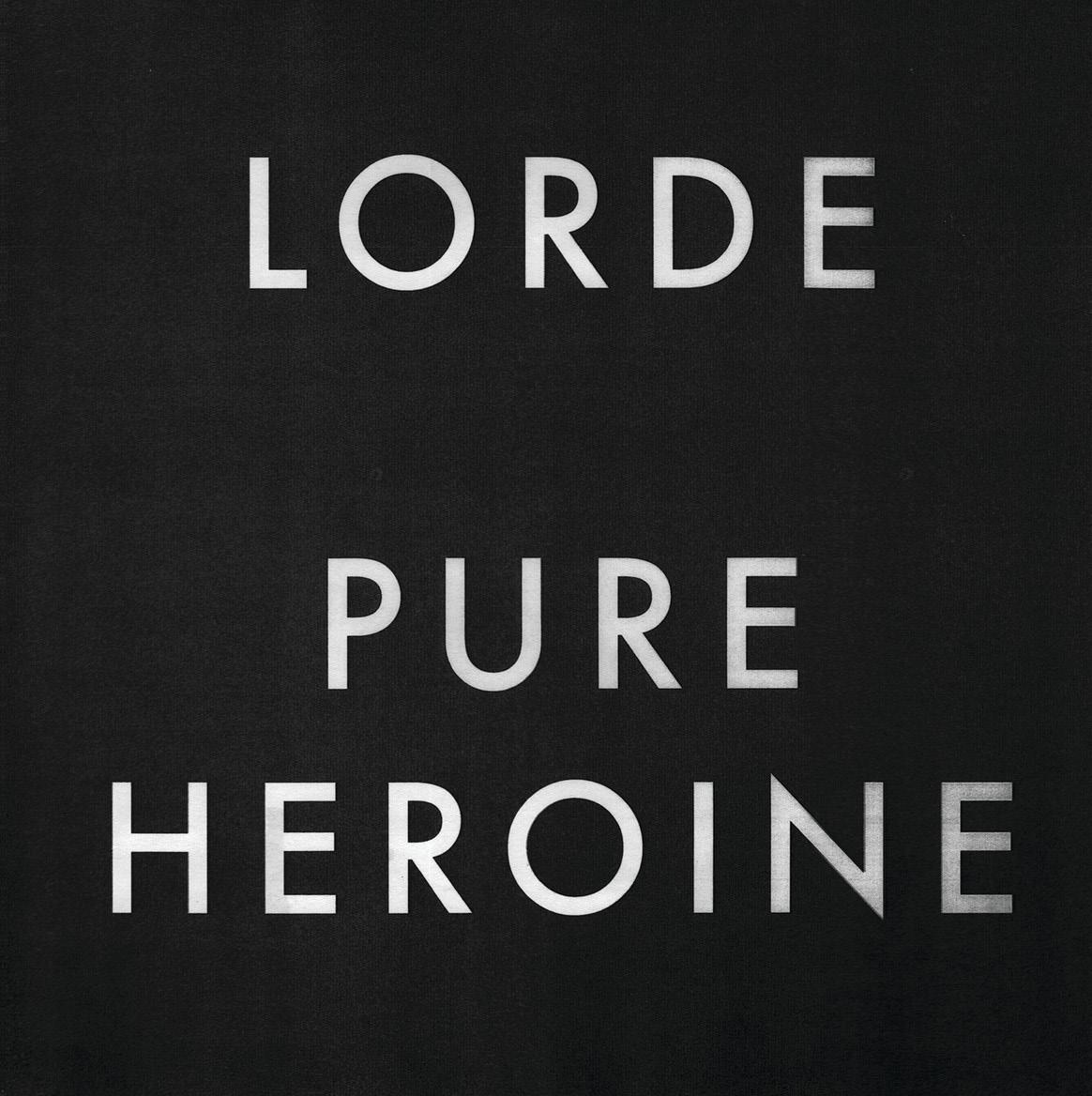

Ella Marija Lani Yelich-O’Connor, better known by her stage name Lorde, was twelve years old when she first entered the music industry. Scouted by Universal Music Group after a talent show performance, Lorde is an example of an artist who truly grew up in the industry. Lorde was freshly sixteen at the time of the release of her first body of work, The Love Club EP, which she self-published through SoundCloud. She then released her first full-length album Pure Heroine less than a month before her seventeenth birthday. Pure Heroine (the extended version of which contains all the tracks featured on The Love Club EP) is truly a work of teenagedom: an unfiltered portrait of the social and emotional battlefield of adolescence. She followed this debut with two more full-length albums: Melodrama (2017) and Solar Power (2021).

Pure Heroine

The lyrical themes of Pure Heroine can be divided roughly into the categories of rebellion, nostalgia, social interaction and isolation, and stardom.

Perhaps it is sensible to start with the theme of rebellion, which produced the track Lorde is best known for: “Royals.”

And everybody’s like Cristal, Maybach, diamonds on your timepiece

Jet planes, islands, tigers on a gold leash

We don’t care

We aren’t caught up in your love affair

In the song’s pre-chorus, Lorde boldly refutes the stereotypes and fantasies

often pushed in modern media. She asserts her indifference towards what is expected of her as a young person and a young star.

Let me be your ruler

You can call me Queen Bee

And baby I’ll rule

Let me live that fantasy

She establishes her own kingdom. She leads her own faction. These themes are repeated in lyrics from the tracks “Glory and Gore” and “Team.” “Glory and Gore” metaphorically inserts Lorde into a battle, a gladiator-age arena.

And now we’re in the ring and we’re coming for blood … You could try to take us But victory’s contagious “Glory and Gore” exemplifies the more violent symbolism with which Lorde approaches her teenage experience. It is a battle cry that pulls no punches. “Team,” contrarily, employs an equally powerful nonchalance: We’re kind of tired of getting told to throw our hands up in the air

So there

The final line of the song’s chorus, “So there,” is delivered with complete apathy. These three tracks come together to characterize the adolescent rebellion Lorde presents in Pure Heroine as a whole: a combination of recklessness and the utter indifference that fuels it.

home

It drives you crazy, getting old

In the opening verse, Lorde paints the picture of the kind of party everyone is familiar with. It is unremarkable. It is naive. “My mom and dad let me stay home:” this lyric screams youth and immaturity. Plainly, Lorde states her longing for a simpler past, saying, “It drives you crazy, getting old.” She once again utilizes childish language in the song’s chorus.

We can talk it so good

The grammatical error and the phrasing are reminiscent of that of a young child. Both the verses and the chorus of “Ribs” drip with nostalgia; however, it is the post-chorus and outro that unabashedly drives this point home.

I want ‘em back

The minds we had

How all the thoughts

Moved ‘round our heads

I want ‘em back

The minds we had

It’s not enough to feel the lack

I want ‘em back, I want ‘em back, I want ‘em

There is no greater anthem of nostalgia than Lorde’s “Ribs,” a six-minutelong track that takes the listener right back to a fantastical youth.

The drink you spilt all over me

Lover’s Spit left on repeat

My mom and dad let me stay

These lyrics, echoed and desperate, beg for the imagination and carelessness of a child’s mind. “It’s not enough to feel the lack:” self-awareness does not mitigate this pain. Lorde finds herself torn away from the comforts of her childhood, fearfully looking towards an unknown future. It is understandable, the angst and anger that is born from this terror.

The most overarching theme of Pure Heroine is naturally that of the social. From feelings of rejection, isolation, distaste, and even hatred towards some people to her fierce dependence on

others, Lorde’s writings holistically encompass the adolescent social experience. In “Tennis Court,” she criticizes social structures and stereotypes.

Baby, be the class clown

I’ll be the beauty queen in tears

It’s a new art form

Showing people how little we care

She caustically points out the ridiculousness of social performance in high school and in general life. In “Buzzcut Season,” she is a young girl angry at the disaster that is the world being handed to her

Explosions on TV

And all the girls with heads inside a dream …

And I’ll never go home again and in “World Alone,” she is angry at the people that world contains.

All the double-edged people and schemes

They make a mess then go home and get clean

In “White Teeth Teens” and “The Love Club,” Lorde comments on a lack of true belonging even in groups she, appearance-wise, is a member of.

I let you in on something big

I’m not a white teeth teen

I tried to join, but never did

The way they are, the way they seem

After building up an entire song describing her antics and activities with said white teeth teens, she shatters this image in the bridge. In “The Love Club,” she declares from the very first lyric:

I’m in a clique but I want out

She rejects and feels rejected by her supposed companions. However, even amidst these criticisms and complaints, throughout Pure Heroine, Lorde addresses a certain “you.” In the events of “Buzzcut Season,”

But you laughed, “Baby, it’s ok” …

But now we live beside the pool

And everything is good …

I live in a hologram with you Lorde is not alone. She faces the burning world comforted by this friend. The same is true in “A World Alone:” And people are talking, people are talking

But not you …

Let ‘em talk ‘cause we’re danc ing in this world alone

Lorde finds a haven from society in “you.” In “400 Lux,” this “you” is even able to relieve her of the drudgery of day-to-day life.

We’re never done with killing time

Can I kill it with you?

What Lorde has is a deep, dependent relationship. Deep, dependent, and also volatile. In “A World Alone,” she admits

I know we’re not everlasting We’re a trainwreck

Waiting to happen

Lorde paints a picture of complete social tension. She is torn between isolation and co-dependence. She encapsulates perhaps the greatest struggle of growing up: the absence of both stable and fulfilling social relationships.

It is one of Pure Heroine’s most often-overlooked tracks that contains some of the most important messaging in regard to stardom: “Bravado.”

All my life

I’ve been fighting a war … My heart jumps around when

I’m alluded to …

It’s the closest thing to assault when all eyes are on you

In “Bravado,” Lorde details her experience as a performer — as someone who has been a performer her whole life. The song starts off slow and dark in the first verse, as she describes the

I was frightened of

Every little thing that I thought was out to get me down

To trip me up

To laugh at me

But I learned Not to want

The quiet of a room with no one around to find me out

I want the applause, the ap proval, the things that make me go, oh

With the chorus comes a blaring organ track and a change from a minor to a major key. Both with her lyrics and music does Lorde convey the switch she makes, the mask she puts on to face a crowd. It is notable that “Bravado” was part of Lorde’s original EP, The Love Club. It is truly a marker of her journey into performance and fame. Lorde then furthers this theme with “Still Sane”

Riding around on our bikes

we’re still sane

I won’t be her tripping over on stage

It’s all cool

Still like hotels but I think that’ll change

Still like hotels in my newfound fame

Promise I can stay good

In the chorus of the song, Lorde establishes and before and after: as a child, riding her bike, she is “still sane.” She is not like the other stars “tripping over on stage.” This changes when she enters into music and into fame. She reflects that she is new enough to the scene that she still finds hotels exciting; she is still enthusiastic about the experience.

All in all, Pure Heroine is a refusal, a cry of rebellion and anger. Lorde is young, inexperienced, and filled with teenage angst.

Melodrama

Melodrama, released in June of 2017, is the musings of now almost-twentyyear-old Lorde. It carries a significant amount of the anger and recklessness displayed in Pure Heroine. For example, Pure Heroine’s theme of violence is heavily featured in Melodrama as well. From the drug usage in “Perfect Places”

All of the things we’re taking ‘cause we are young and we’re ashamed and “Sober”

Ain’t a pill that could touch our rush to the abandoned champagne glasses and hungover regret in “Sober II (Melodrama),”

All the gunfights and the limelights

And the holy sick divine nights

They’ll talk about us

All the lovers

How we kiss and kill each other Lorde once again takes emotions of love and anger to brutal extremes. Lorde’s sardonic and caustic outlook on society and relationships is also on full display. This is best exemplified by the cynical track “Loveless.”

Bet you wanna rip my heart out

Bet you wanna skip my calls now

Well, guess what? I like that … L-O-V-E-L-E-S-S generation

All fucking with our lovers’ heads generation

Here, Lorde, full of vitriol, takes on a taunting tone. Attached to a previous break-up ballad “Hard Feelings,” “Loveless” is the other side of the coin of heartbreak: bitterness.

prise),” “Hard Feelings,” “Writer In the Dark” — Lorde paints a bleaker picture. Gone in these tracks is the energy of rebellion and anger present in Pure Heroine. She draws on painfully familiar imagery of independent, adult life to paint a picture of true loneliness. In the second verse of “Writer In the Dark,” she states

I still see you now and then Slow like pseudoephedrine

If you see me, will you say I’ve changed?

I ride the subway, read the signs

I let the seasons change my mind

References to cold medicine and the subway suddenly humanize the suffering that was much more glorious and grand in Pure Heroine. In “Hard Feelings,” she writes in the outro: But I still remember everything How we’d drift buying groceries

How you’d dance for me

In Melodrama, Lorde gives concrete details to the deep relationships she referenced in Pure Heroine. The “you” is defined and, devastatingly, has left. In Pure Heroine, even in her darkest moments, she was accompanied. In Melodrama, she is completely left on her own. In this way, Melodrama becomes a markedly transitional album. Written while Lorde was eighteen and nineteen, Melodrama documents a time in her life in which she is growing into adulthood. She is living on her own; she is thrust into the adult world. With it, she presents newfound loss.

However, in addition to established themes, Melodrama also showcases a deeper sorrow, a more profound suffering. The majority of the album’s tracks — “Liability,” “Liability (Re-

Melodrama stands out as an album written in a period of change. Listeners can see both the pulls of young, teenage Lorde and the sorrows of the adulthood she comes into. Melodrama, both musically and thematically, acts

as the perfect bridge between where Lorde’s career begins and where it currently stands.

Solar Power

Solar Power, Lorde’s third album, comes nearly a decade after her first release. With it, Lorde makes a complete 180 in both her style and her themes. Gone nearly completely is the high-octane nature of 16-year-old Lorde. At 24, Lorde has acquired both peace and wisdom her younger self never even dreamed of. Perhaps the starkest example of this in her lyrical choices is the callback to Melodrama’s most notoriously painful track, “Liability.” In this song, she sings:

Every perfect summer’s eating me alive until you’re gone Better on my own

In Solar Power’s “Big Star,” she makes a callback to the “every perfect summer” lyric.

Every perfect summer’s gotta take its flight

I’ll still watch you run through the winter light

I used to love the party, now I’m not alright

I think it is important to highlight here that Solar Power does not lack pain or heartache: this is evidenced by the above lyrics. What separates Solar Power from Lorde’s previous bodies of work is how she approaches this pain. In “Liability,” she carries over from Pure Heroine that aura of rebellion and stubborn independence: “Better on my own.” Whereas in “Big Star,” Lorde acknowledges her heartbreak. “I’ll still watch you run through the winter light / I used to love the party, now I’m not alright.” She takes a reflective stance. She does not blame nor refute; instead, she hopes. The ill will and anger present in her previous albums are long gone. She shows maturity through this display of heartache.

What makes Solar Power believable as a stepping stone on Lorde’s path is just that. The album, despite its general air of enlightenment, still discusses emotional struggles and intrapersonal turmoil. With “Mood Ring,” Lorde explains how she cannot find a remedy for her emotional numbness:

I’m trying to blow bubble but inside

Can’t seem to fix my mood

Today it’s as dark as my roots

She acknowledges that even with the persona she has adopted, the hair she has dyed, she is still unable to “fix” her emotional struggles. In “Fallen Fruit,” she conveys her difficulty grappling with the impossibility of true bliss: But how can I love what I know I am gonna lose? Don’t make me choose

The fallen fruit

She even goes so far as to discuss an amused annoyance with an elusive past boyfriend in “Dominoes:”

The whole world changes right around you

You get fifty gleaming chances in a row

And I watch you flick them down like dominoes

Must feel good being Mr. Start Again

This lighthearted nature of her criticism or ill-feeling towards someone is something that would have been impossible in her Pure Heroine or Melodrama eras. She jokes about the man’s drug use, about his yoga sessions with Uma Thurman’s mother. The listener can tell that she does not harbor serious hatred towards this man the same way she did towards her enemies in Pure Heroine. No longer do these negative emotions weigh her down. Lorde’s experience with pain in Solar Power can be distinguished from those of Pure Heroine and Melodrama in the sense that no longer does she wallow

in her suffering, no longer does she self-destruct. She still suffers: but she takes this suffering at face value. This is what shows her growth and maturity. This is emphasized one final time in the album’s closing song, “Oceanic Feeling.” In this track, Lorde takes listeners on a journey of reflection and contemplation. She describes a calming scene, sounds of the sea playing softly in the background. She balances wisdom and retrospection

Baby boy, you’re super cool I know you’re scared So was I

But all will be revealed in time

I can make anything real … Just had to breathe And tune in with acknowledgment of what she is yet to learn.

O, was enlightenment found? No but I’m trying

Taking it one year at a time

She is on a journey of growth, a journey on which she has found peace. She makes an overt callback to her music video for “Tennis Court” in which she sports dark lipstick, mouthing the scathing lyrics.

Now the cherry black lipstick’s gathering dust in a drawer

I don’t need her anymore ‘Cause I’ve got this power Here, she leaves behind the anger and bitterness she previously used as a defense mechanism. She opens her heart; instead of warding off pain with substances or risk-taking or violence, she accepts it. She no longer views heartbreak as the horror she once did. She is no longer afraid of suffering.

Lastly, I would be amiss not to mention Lorde’s most overt of songs on Solar Power: her love letter to her past self, “Secrets from a Girl (Who’s Seen it All):”

Couldn’t wait to turn fifteen

Then you blink and it’s been ten years

Here, she references directly the time frame of her first release and now.

Growing up a little at a time, then all at once

Everybody wants the best for you

But you gotta want it for yourself, my love

She speaks with a tender affection. She offers perspective; she has come to understand what she refuted in her teenage years.

Remember all the hurt you would feel when you weren’t desired?

Remember what you thought was grief before you got the call?

In the second verse of the song, Lorde reminisces about a time in which her perspective was much narrower. Without condescension or patronization, she points out the ignorance of her past self. Lastly, in spoken word, Lorde cleverly plays with the announcement of a flight attendant.

Thank you for flying with Strange Airlines...

Your emotional baggage can be picked up at Carousel Number 2

Please be careful so that it doesn’t fall onto someone you love…

We can go look at the sunrise by euphoria mixed with exis tential vertigo? Cool

Lorde’s tone is comforting, like an older sister here to offer advice. She doesn’t know it all; far from it. However, she has healed. She has grown as a person and as a songwriter. Solar Power is Lorde amidst healing. I look forward greatly to what Lorde will produce next.