We always knew that the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement would merit a special issue of An Phoblacht where we would have many of ‘the people in the room’ making a series of contributions about the years leading to the agreement, the negotiations themselves, and the aftermath.

What we publish here is a unique striking addition to contemporary Irish history. There are never before revealed details and analysis on the peace process. It is important for us to give such a wide-ranging Republican commentary as there are many others in political society including the Irish and British governments, as well as the wider for-profit media in Ireland and internationally, who have been sharpening pens and gathering comment for their own GFA events and publications.

It is important to recount here in a considered way the development of the peace process from a Republican viewpoint. It is clear for example that, from the 1980s onwards, it was Republicans who were the dynamic driving the process forward.

The British government had from the Prior Assembly to the futile Brooke/ Mayhew talks locked itself into a pathology of failure. Failure to address the full causes of the conflict in Ireland, and failure to enable a process that could accommodate all of the participants who could create a lasting peace in Ireland.

Political Unionism in Ireland, at times aided by the British Government, stalled and delayed the potential of the peace process to deliver a better future for Ireland, both before and after the GFA was endorsed not just by the majority of political groupings, but overwhelmingly in referenda North and South.

It was Republicans who built the needed cross society coalitions of shared purpose that ultimately delivered the peace process, and who have protected it ever since. This was and continues to be not an easy task.

As An Phoblacht goes to print, it is the anti-democratic destructive forces of political unionism that are once again trying to undermine not just the peace process, but the democratically expressed wishes of the majority of Six-County voters in both the Brexit referendum and last year’s Assembly elections.

We have contributions in this issue from Gerry Adams, Martina Anderson, Lucilita Breathnach, Pat Doherty, Gearóid Ó hEara, Gerry Kelly, Mitchel McLaughlin, Mary Lou McDonald, Mícheál Mac Donncha, Michelle O’Neill, Séanna Walsh, Peadar Whelan, and Pádraic Wilson. Collectively, they bring a message of the power of Republican struggle not just in delivering the Good Friday Agreement but protecting its principles over the last 25 years and building the platform for the next stages in building an Ireland for all. �

What we publish here is a unique striking addition to contemporary Irish history. There are never before revealed details and analysis on the peace process

BY GERRY ADAMS

BY GERRY ADAMS

In the 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement, over half a million people have been born in the North. Add to this those who were only children in 1998. So, perhaps a third of our population today has no experience of violence or recollection of the previous decades of conflict, unless their families were personally touched by it. The Good Friday Agreement is the basis for this new dispensation.

The negotiations, which led to the Agreement, started in June 1996. Sinn Féin was excluded. Castle Buildings, on the Stormont estate, was the main venue for these. Later, in September 1997 when Sinn Féin joined the negotiations, negotiators met in a number of locations in bi-lateral or multi-lateral sessions in Dublin Castle, Lancaster House in London, Downing St, Government Buildings in Dublin, and St. Luke’s in Drumcondra - Bertie Ahern’s Dublin Central constituency office.

I didn’t like Castle Buildings. No one did. It was a sick building – cramped, claustrophobic,

with no fresh air. This was especially true in the last week of talks which saw an exhausting round of protracted meetings that lasted all day and late into the evenings. Even when we left Castle Buildings, the conversations continued by phone or in safe houses in West Belfast away from the prying eyes and ears of British intelligence. We hoped.

Early in that last week, Sinn Féin pressed the two governments on how they intended defining consent for Irish unity. This had been a consistent theme for us alongside equality issues. There was no doubt – no equivocation – ‘a majority is always 50% plus one’ we were told. We were also given a commitment by the British Prime Minister that the new constitutional legislation contained in the Agreement would repeal the Government of Ireland Act. This was a key objective of ours.

Senator George Mitchell chaired the talks. His schedule called for a deal to be concluded by midnight on Holy Thursday, 9 April. But as the meetings began that morning, it soon became clear that the unionists were not yet prepared to agree on an Executive or Cabinet structure or to the safeguards nationalists were demanding. The discussions continued through the night.

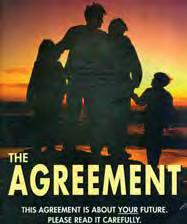

None of this was made any easier by the refusal of the Ulster Unionist Party to speak to us. David Trimble, the Ulster Unionist Party leader, had entered the talks in September 1997 flanked by the UDA and UVF and declaring that he was not going to negotiate with Sinn Féin. The DUP had absented themselves.

Slowly in the course of the Thursday night, progress was made. Agreement was reached on ensuring that the North/South Ministerial Council would be established through legislation and with Executive powers.

It was also agreed that the Assembly, the North/South Ministerial Council, and the British/Irish Council would all come into effect at the same time in order to reduce any possibility that unionists might succeed in frustrating the birth of any one of the institutions. Gradually bits of the jigsaw came together. By 3am, unionists had agreed to the establishment of an Executive with many of the safeguards we had argued for.

However, the issue of prisoners, as well as the equality agenda, demilitarisation and decommissioning were still unresolved. Martin McGuinness and I spent a lot of time with the Taoiseach and the British Prime Minister.

Earlier on the Thursday evening, Gerry Kelly and several others were dispatched to meet the British Secretary of State Mo Mowlam and officials from the NIO. We wanted the prisoners out within a year. However, two years was our private fall-back position. The Brits wanted three years.

At one point, they presented Gerry with a new paper but refused to allow him to leave the room with it. Gerry told them that that wasn’t acceptable and left. A few minutes later, as he was telling us this, a breathless Mo Mowlam arrived with a copy of the document. She asked Gerry when we wanted the prisoners out. He said, immediately. She said that wasn’t possible. Gerry then remarked that it needed to be within a year. Mowlam went off to reflect on that.

A few hours later, around 1am, President Clinton’s first call came through. Blair had been talking to him, so he knew that we were stuck on the prisoners’ issue. I explained to the President that enormous progress had been made so far but that bringing people on board required early releases.

Gerry Kelly went off to meet with the smaller loyalist parties to see if they would come on board our efforts. He rapped their door and put his head in. The large crowd of men sitting around on chairs and tables were surprised to see him. Gary McMichael of the Ulster Democratic Party (UDA) and David Ervine of the Progressive Unionist Party (UVF) came out into the corridor. Gerry explained the situation. If we both pressed on this issue, we believed we could reduce the timeframe further.

Ervine later told Gerry that they had already agreed with David Trimble a three-year period for prisoners’ release, and they didn’t want to upset Trimble at such a delicate point in the process.

By now, like everyone else, we were all dead tired. Surrounded by sleeping comrades, Martin, myself, Gerry Kelly, and a few others discussed all this. We decided to have another go at Blair. He and Bertie were sitting quietly talking together. Blair told me that Bertie was concerned about winning any future referendum on the Irish constitutional matters. Bertie himself said that Articles 2 and 3 could be a difficult issue for Fianna Fáil. I agreed with him.

Martin asked Blair where he was on the prisoner releases. After a brief but intense discussion, he said he would do it in two years. At the same time, another negotiation, potentially more perilous, was going on. The unionists were trying to secure a procedural linkage

A third of our population today has no experience of violence or recollection of the previous decades of conflict, unless their families were personally touched by it. The Good Friday Agreement is the basis for this new dispensation

We were also given a commitment by the British Prime Minister that the new constitutional legislation contained in the Agreement would repeal the Government of Ireland Act. This was a key objective• David Ervine, Progressive Unionist Party (UVF) • Gary McMichael, Ulster Democratic Party (UDA)

within the agreement between actual decommissioning and holding office in an Executive.

We had consistently warned the governments that any preconditions on our participation in an Executive would be a serious mistake. Martin and I had three meetings with Blair and Ahern in the wee hours of Friday morning. They both knew that we weren’t negotiating for the IRA and that there was no possibility of us signing up to something we couldn’t deliver.

The British agreed that the Agreement should call on all parties to use their influence to achieve decommissioning in the context of the implementation of the overall agreement.

Around 2.30am, President Clinton had a long call with Senator Mitchell who briefed him on where he thought the talks were and how close a deal was. About 5am, President Clinton rang me again

Martin and I went up to see Senator Mitchell. His colleagues were now busy pulling together all the bits and pieces of paper that were to make up the agreement. We told him we were prepared to go to our party with a draft agreement but only if there were no further changes. We told the two governments the same thing.

David Trimble, who had left in the early hours of the morning, returned to learn that a final copy of the agreement would be ready for 11am. All the parties were told that a plenary was scheduled for noon.

In the UUP offices, a much-enlarged Unionist delegation was now going through the agreement clause-by-clause, line-by-line. It wasn’t going down well. The noon deadline came and passed.

Shortly after lunch, a unionist delegation, led by Trimble and Jeffrey Donaldson, went to see Tony Blair. He told them that he would not change the agreement. But we later learned that Blair provided Trimble with a side letter which breached the terms of the agreement. Blair wrote that in his view the effect of the decommissioning section of the agreement meant that the process of decommissioning should begin straight away.

Trimble was looking for a mechanism to exclude Sinn Féin Ministers from the Executive. While refusing to concede this, Blair said that he would keep it under review. This was no part of the agreement. It ran in the face of all our discussions. For some in Trimble’s party, this letter was not enough. Some wanted to walk away.

All this time, we, like everyone else, were sitting around waiting to learn the outcome of the unionists’ deliberations. Periodically, John Hume would drift in or some of us would wander into the Irish government’s rooms to get an update. Someone discovered the bar was open. Siobhán O’Hanlon went off for supplies of coke, bottled water and orange juice. Incidentally, thanks to the efforts of Siobhán and Sue Ramsey, our team was rarely without refreshments, including sandwiches from the kitchen in Government Buildings.

I spoke to Senator Mitchell. “The problem for David Trimble is that he didn’t think you were serious,” the Senator told me. “He expected Sinn Féin to blink first. He expected you to walk out. You haven’t. And he is running out of time.”

Not long after four o’clock, I called our core group together. By now, Jeffrey Donaldson, Arlene Foster, and several others had stormed out of the building.

I suggested to our group that we should press the Irish government to bring matters to a head. I met with senior officials and told them to tell the Taoiseach and British PM that “we are going home soon if

I met with senior officials and told them to tell the Taoiseach and British PM that “we are going home soon if things don’t shape up. Ask them to call the plenary. Otherwise, the Unionists will dither forever”

When it came to David Trimble’s turn, he seemed to hesitate for a split second when Senator Mitchell invited him to speak. He reddened slightly as he used a pencil to stab the microphone button on the table before him. “Yes,” he said• Bertie Ahern, George Mitchell and Tony Blair • US President Bill Clinton • Mo Mowlam, John Hume and Gerry Adams at the inauguration of President Mary McAleese, November 1997

things don’t shape up. Ask them to call the plenary. Otherwise, the unionists will dither forever.”

“Someone needs to put testicles on David Trimble,” another official agreed. The most senior person agreed to speak to Blair and Ahern. We waited. Minutes later, the messenger returned. “Message delivered,” he told us.

Shortly afterwards, we were told that a plenary was set for five. Apparently, David Trimble had phoned the Senator at 4.45pm to tell him the UUP was ready to sign up.

I went up to see the Senator with Martin and we thanked him and Martha Pope who had been a consistent and positive influence through all the deliberations.

When we returned to our office, I pulled our people together. I congratulated them all. A lot of people depended on us in these negotiations. I felt very proud to be part of our effort. Everyone had done their best.

By the time we got to the conference room, it was packed. Additional members of all the parties stood together behind their delegations. There was an air of quiet excitement. Television cameras were allowed in and the plenary was broadcast live. Senator Mitchell invited each of the parties to say whether they supported the Agreement. When it was my turn, I explained that we would have to bring it back to our party. But I said that our delegation would be urging support for the agreement.

When it came to David Trimble’s turn, he seemed to hesitate for a split second when Senator Mitchell invited him to speak. He reddened slightly as he used a pencil to stab the microphone button on the table before him. “Yes,” he said.

There were smiles all round. Even some of the unionists were smiling. When all the leaders had said their piece, the Senator closed the proceedings and there was sustained applause. For a few minutes, everyone milled around shaking hands. Some people were hugging each other. Then, it was outside to talk to the press.

That was 10 April 1998. It is hard to believe that was 25 years ago.

The Good Friday Agreement marked an historic and defining point of change in all our lives. However, George Mitchell got it exactly right when he said that getting the agreement was the easy bit, implementing it would be another matter.

Progress since then has been slow and torturous. There are key elements of the Agreement not yet implemented and currently

there are no functioning institutions as the unionists – now the DUP – try to delay change.

But progress has been made. Not least in the number of people who are alive today who might otherwise have died through conflict.

As its heart, the Good Friday Agreement is about change; political, social, economic, and constitutional. It emerged out of a hesitant cooperative effort by nationalist and republican Ireland to put in place a peace process.

Sinn Féin never pretended the Good Friday Agreement was a settlement. Neither did we pretend that it delivered the Proclamation of 1916. It did however establish, for the first time a peaceful way and a mechanism to end the Union with England. Our experience also reinforced for our leadership the merits (and risks) of negotiations as a means of struggle.

After the Agreement, British and Irish establishments presumed that the SDLP and the UUP would share the main political posts and that the Northern statelet would continue with minimum changes. Of course, that is not what happened. A process of change once started is difficult to stop.

It can be delayed and perhaps temporarily diluted but provided those of us who want maximum change can stay united and strategically focussed, while building our political strength and being resolute but generous, then what some thought to be impossible becomes possible.

So, despite the current difficulties the future looks bright. This is indeed a decade of opportunity.

The Good Friday Agreement has created a democratic and peaceful path to reunification. Our task is to make it happen. �

There are key elements of the Agreement not yet implemented and currently there are no functioning institutions as the unionists – now the DUP – try to delay change

Sinn Féin never pretended the Good Friday Agreement was a settlement. Neither did we pretend that it delivered the Proclamation of 1916. It did however establish, for the first time, a peaceful way and a mechanism to end the union with England• Ulster Unionist Party leader, David Trimble phoned George Mitchell at 4.45pm and told him the UUP was ready to sign up • Jeffrey Donaldson, along with Arlene Foster, and several others stormed out of Stormont before the Agreement had been signed

Twenty five years ago, an agreement was signed in Belfast that transcended the past and changed the future. The Good Friday Agreement brought an end to three decades of terrible conflict in Ireland. To this day, it stands as an historic, international success story in peace-making - a blueprint for the resolution of even the most intractable of conflicts. The agreement is a testament to what can be achieved when people come together in the spirit of hope to build a better tomorrow.

Resoundingly endorsed by people North and South, it is rightly described as the people’s Agreement. The Agreement and all the good that stems from it belongs to people. That can never be taken for granted. Nor can it be taken away by those who seek to undermine hard won progress for the sake of narrow political interests.

From our vantage point of nearly a quarter of a century of peace, we can say that The Good Friday Agreement transformed our country. The triumph of the agreement is that an entire generation in Ireland – ‘The Good Friday Agreement Generation’ – has grown-up and come of age in a time free of conflict. The Ireland of 2023 is a very different place. If we can agree that the purpose of leadership is always to make things better for our children, the achievement of the Good Friday Agreement shines brightly as the light on the hill.

The architects of the Agreement understood well that peace building is more than ending war but also making a concerted and unified effort to remove the underlying causes of conflict. That reconciliation must be at the very heart of progress. It was this realisation that ensured that the agreement would become a bedrock of and a pathway to a new Ireland for all our peo-

ple, from all communities, traditions, backgrounds, and identities.

Roger Casement once wrote, “A nation is a very complex thing. It never does consist; it never has consisted solely of men of one blood or one single race – it is like a river, rising in the hills with many sources, many converging streams, that become one great stream.”

The genius of the Good Friday Agreement is that it not only provides an authentic accommodation for the multiplicity of identities on our island, but this reality is woven deeply into the fabric of the accord. The right to be Irish, British or both is guaranteed. It is enshrined in the Agreement, but it is also a reality of our shared lives to be embraced and nurtured as a strength while we continue to work together for a better future. None of us have anything to fear from the identity of another. In fact, we have so much to gain. It is through such an embrace that we truly see each other and reach for the living, breathing essence of the Ireland that can be.

At its very core, the Good Friday Agreement is about equality for everyone who calls Ireland home. It has made the advancement of equality for all the driving goals for politics. Equality of opportunity. Equality of education. Equality of aspiration and ambition for every single citizen.

The Agreement has made progress possible. It has made real change possible. Today, a nationalist, republican woman stands elected as the First Minister in a state designed to ensure it could never happen. When Michelle O’Neill

�

A nation is a very complex thing. It never does consist; it never has consisted solely of men of one blood or one single race – it is like a river, rising in the hills with many sources, many converging streams, that become one great stream

says she will be a First Minister for all, she means it. Respect for all. This is the only basis upon which power-sharing can truly work and deliver the good government to which people are entitled.

It is regrettable that, since the historic Assembly Election of May 2022, the DUP chose to use the Protocol as pretext to boycott the democratic institutions. We all know the Protocol is necessary to protect Ireland from the sharp edge of the Tory Brexit. We always knew, with good faith and political will, it would be possible to strike a deal. Above all else, the Executive must be up, running and working for all the people of the North. Martin McGuinness made it work. Ian Paisley made it work, and it is through partnership that we can make it work again. This momentum for progress captures the spirit of a generation determined to move on together.

We also know that equality cuts much wider than divisions of the past. Irish Republicans have no interest in simply stitching North to South and carrying on as normal. We are about building an Ireland for all our citizens in all their diversity, including our Traveller community and those who have made this land their home in recent years. Equality must always be the watchword of nation building, and Republicans are first and foremost about the work of building the Irish nation anew.

The ultimate triumph of peace is unity. The Good Friday Agreement provides for Referendums on Irish Unity. I believe that this will happen in the course of the next decade. We are living in the end days of partition. We are living in a time when history will be made by the people. The reunification of Ireland presents the single greatest opportunity to unlock all the potential of our island, to deliver prosperity for all.

The conversation is growing, and a Citizens Assembly is urgently required to prepare for planned, peaceful, and democratic constitutional change.

Changing and Uniting belongs to everyone. Unity referendums can be won and won well, but we will have to reach out, create space for others to come on board, and build alliances right across Irish society. We will have to push the boundaries, surpass expectations and extend ourselves even further. That is what republicans

have always done in the name of peace and progress.

The United Ireland we seek to build is an Ireland of equality and inclusion. An Ireland with strong public services, driven by opportunity and with balanced economic and social development where no region is ever left behind. A nation home that stands as a monument to this era of seismic generational change in Ireland.

The tides of history are with those who seek to unite. Our population is growing to levels not seen since An Gorta Mór. I have no doubt that the power of our young people, from all backgrounds and traditions, will play a special part in unifying Ireland. We also want those who have been forced to emigrate to have the opportunity to come back and build a good future at home, to live their lives in an Ireland changed for the better.

Twenty five years ago, a generation reached for hope and a new way forward. Through the Good Friday Agreement, they wrote a ground-breaking chapter in Ireland’s story. Today, it falls on our generation to write ours. We can be the generation that unites our country and our people. Here, in our time, we can build the nation home. We can realise the promise of a better tomorrow, together and for each other. It is an opportunity we must seize with both hands. �

I was 20 years old and a young mother when the Good Friday Agreement was signed. I remember vividly the sense of hope and optimism that a brighter, more peaceful future was on the horizon.

And from that point I got in behind the politics to help build the peace and as a representative of the Good Friday Agreement generation, I have been working towards that ever since.

It is of course a political accommodation. Through the establishment of the political institutions, the power-sharing Assembly and Executive, and the North-South and East-West bodies, it has helped the process of bringing people together and provided a peaceful alternative to 30 years of conflict.

This was complemented by the demilitarisation of British Army security apparatus and checkpoints and free movement across the whole island which was within the European Union. This transformed the lives of those living and working in the border counties.

While we all remember the GFA and its huge achievements, it is worth reminding ourselves there have been six further political negotiations and agreements since then, all aimed at cementing peace and delivering on the key commitments from the Good Friday Agreement itself.

This has been painstaking work, but quite necessary to ensure commitments made were followed through on.

Fast forward to 2016 and the Tory Brexit was forced upon the people of the North without the consent of the majority who voted in the referendum to remain.

The outworking of that has damaged our power-sharing institutions and created huge political setbacks for our society here.

The hard Brexit pursued by the Tories and championed by the DUP ruptured British-Irish relations causing major political divergence between the governments.

This resulted in London and Dublin losing their ability to act jointly in their stewardship of the Agreement, and the north was

The 'Windsor Framework' deal struck between the EU and British government is a positive development and will help give certainty to local businesses and the economy• First Minister designate Michelle O’Neill and Mary Lou McDonald

then squeezed causing a destabilisation of politics and the economy.

The reliance of the British Tory government on the DUP to keep them in power through the Confidence and Supply arrangement removed any pretence of the ‘rigorous impartiality’ required of them under the Good Friday Agreement.

The fact is that the relationship from London to Dublin under Tory leaders David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson and Liz Truss became entirely self-serving and unpredictable.

They attempted to undermine the Protocol, which was put in place to prevent a hard border and protect the all-island economy, and in turn undermine the Good Friday Agreement itself.

Given the key role played by the United States in achieving the Good Friday Agreement, the Joe Biden Administration and wider Irish-America has been adamant that despite Brexit, the Good Friday Agreement and peace in Ireland must be preserved, and should it be damaged there is no prospect of a UK-US post-Brexit trade deal.

There is little doubt that the so-called ‘special relationship’ between Washington and London had become strained under successive dysfunctional and chaotic Tory governments.

However, what has fundamentally forced things to change now is the outbreak of war on Ukraine, the global energy crisis and rising cost of inflation and its economic impact, all of which has demanded that allies come together in their national interests.

The new British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is desperate to undo the damage that his government has done to the British economy.

The reality for the DUP, who have fallen in and out of cosy relationships with the Tories before being quickly dropped, is that power-sharing with Sinn Féin and the other Executive parties is the only show in town.

Direct rule from London is no longer a viable option, and if Stormont was dissolved what would in fact emerge is a British-Irish partnership approach with real input from Dublin.

Brexit has caused a permanent cleavage and divided even British public opinion who see very little of the promised benefits coming through.

The 'Windsor Framework' deal struck between the EU and British government is a positive development and will help give certainty to local businesses and the economy.

Sinn Féin consistently made it clear to British Prime Ministers and the EU Commission President throughout this process that

The reality for the DUP, who have fell in and out of cosy relationships with the Tories before being quickly dropped, is that power-sharing with Sinn Féin and the other Executive parties is the only show in town• The new British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is desperate to undo the damage that his government has done to the British economy

the fundamental principles we wanted to safeguard were no hard border on the island of Ireland, protecting the Good Friday Agreement, and safeguarding access to the EU single market for the whole island.

People rightly want to see parties working together around the Executive table, delivering for them, focusing on their future and unlocking economic opportunities that make a difference to the lives of everyone. Sinn Féin is committed to that.

Since the collapse of the Assembly in May 2022, the DUP embarked on a blockade of the Assembly and Executive that has only served to punish workers and families who are struggling with the cost-of-living.

It has blocked parties working together to fix the huge challenges in our health service, including tackling waiting lists and hiring more doctors and nurses to take the pressure off our exhausted health and social care workers.

People are now starting to look towards the

future, beyond Brexit. They want a good standard of living, more and better jobs, a firstclass health service and all the benefits of EU membership. The loss of these benefits can only be replaced through reunification.

An unstoppable conversation is taking place right now about the future, and more and more people from all backgrounds and none are starting to look at what that means, and they are helping to shape the conversation.

The debate on reunification has been reframed because of Brexit, and reunification is now seen as a part of a wider process of European integration. Having one par t of the island of Ireland inside the EU and the other outside is not a durable or realistic position.

And the EU have been clear that a reunified Ireland would have automatic entry into the European Union.

I see no contradiction in power-sharing and making politics work for everyone in a

genuine and practical way, and which also takes account of the substantial differences between our continuing, and equally legitimate, political aspirations.

While I am the first nationalist to become First Minister, I do not seek to serve only one section of society.

I intend to be a genuine First Minister for all, irrespective of what tradition you come from, or where your allegiances lie. I will work to reach people where they are with an open hand and I am hopeful that they will respond with an open mind.

A quarter century on from the Good Friday Agreement we must all settle for a shared future. We have spent a century apart. It’s time to work together for the benefit of everyone.

An Phoblacht selects some of the key moments and events that led to the Good Friday Agreement.

The Hume/Adams talks marked the next substantial milestone in the Peace Process. Those talks and the resulting Irish Peace Initiative broke through the failure of the Brooke/Mayhew talks, which had begun in 1990 and collapsed a year later.

The publication of ‘A Scenario for Peace’ in May 1987, the 1988 Sinn Féin/SDLP talks from January to September, and the February 1992 launch of ‘Towards a Lasting Peace’ were all crucial steps taken by republicans.

In April 1993, Gerry Adams and John Hume said in a joint statement that, “As leaders of our respective parties, we accept that the most pressing issue facing the people of Ireland and Britain today is the question of lasting peace and how it can best be achieved” and that, “Everyone has a solemn duty to change the political climate away from conflict and towards a process of national reconciliation, which sees the peaceful accommodation of the differences between the people of Britain and Ireland and the Irish people themselves”.

In September 1993, the IRA issued a statement welcoming the Hume/Adams Initiative, stating that, “Our Volunteers, our supporters, have a vested interest in seeking a just and lasting peace in Ireland.”

By November 1993, the British Government admitted it had been involved in meetings with Sinn Féin between 1991 and 1993. On 18 December 1993,

On 31 August, the IRA released a statement announcing a cessation of all military operations from midnight. The statement said:

“Recognising the potential of the current situation and in order to enhance the democratic peace process and underline our definitive commitment to its success, the leadership of Óglaigh na hÉireann have decided that as of midnight, Wednesday, 31 August, there will a complete cessation of military operations. All our units have been instructed accordingly.

“At this historic crossroads, the leadership of Óglaigh na hÉireann salutes and commends our volunteers, other activists, our supporters and the political prisoners who have sustained this struggle against all odds for the past 25 years. Your courage, determination and sacrifices have demonstrated that the spirit of freedom and the desire for peace based on a just and lasting settlement cannot be crushed. We remember all those who have died for Irish

freedom and we reiterate our commitment to our republican objectives.

“Our struggle has seen many gains and advances made by nationalists and for the democratic position. We believe that the opportunity to create a just and lasting settlement has been created. We are therefore entering into a new situation in a spirit of determination and confidence: determined that the injustices which created the conflict will be removed and confident in the strength and justice of our struggle to achieve this.

“We note that the Downing Street Declaration is not a solution, nor was it presented as such by its authors. A solution will only be found as a result of inclusive negotiations. Others, not least the British government, have a duty to face up to their responsibilities. It is our desire to significantly contribute to the creation of a climate which will encourage this. We urge everyone to approach this new situation with energy, determination and patience.”

Gerry Adams pledged in conjunction with John Hume and the then Taoiseach Albert Reynolds the party’s total commitment to democratic and peaceful methods of resolving political problems. The three leaders shared an historic handshake on 6 September 1994.

The British removed the broadcasting ban on Sinn Féin following a similar decision in the 26 Counties in February. Sinn Féin held an internal conference in Dublin to discuss developments. The Forum for Peace and Reconciliation opened in Dublin Castle. The Combined Loyalist Military Command announced a cessation in October.

The first official meeting was held between British Government officials and Sinn Féin in December 1994. The government claimed decommissioning was an obstacle to progress, but would not answer Sinn Féin’s questions about demilitarisation. Sinn Féin produced a demilitarisation map, detailing the massive number of British military posts in Ireland.

John Major and John Bruton launched their ‘Framework’ document, which included plans for a Six-County Assembly in February.

In July 1995, Sinn Féin pulled out of talks with the British Government, after the British introduced the issue of decommissioning. The party said the subject had not been on the table when the IRA called their cessation.

Residents of the Lower Ormeau Road were hemmed into their area as the RUC forced an Orange Order march down the road.

The head of the International Body on Decommissioning, former US Senator George Mitchell, invited submissions on arms decommissioning from all parties.

The Mitchell Report was published in January, laying down six principles of non-violence for entry into all-party talks.

Sinn Féin had engaged positively with the International Body on Decommissioning in 1995 and 1996 in an attempt to resolve the impasse. Despite the bad faith of the Major government, Sinn Féin had used all its influence to sustain the first cessation for a full 17 months, until the rejection by Major of the report of the International Body on Decommissioning.

The IRA ended its cessation with the bombing of Canary Wharf in London on 9 February. In a statement, they said, “The cessation presented an historic challenge for everyone, and the IRA commends the leaderships of nationalist Ireland at home and abroad. They rose to the challenge. The British Prime Minister did not.

“Instead of embracing the peace process, the British government acted in bad faith with Mr Major and the Unionist leaders squandering this unprecedented opportunity to resolve the conflict.

“Time and again, over the last 18 months, selfish party political and sectional interests

in the London parliament have been placed before the rights of the people of Ireland.”

In March, Sinn Féin was turned away from a consultative process organised by the two governments. Sinn Féin polled a record vote in May’s Six-County Forum elections. Sinn Féin was subsequently barred from the opening of inter-party talks.

• 1997: More violence on the Garvaghy Road after Orange Order parade brings renewed calls for a proper policing service

May’s Westminster elections put Labour Party leader Tony Blair into 10 Downing Street and returned Gerry Adams and party colleague Martin McGuinness as MPs. In June, Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin was elected TD for Cavan-Monaghan. A Fianna Fáil Progressive Democrats government was formed in the 26 Counties, with Bertie Ahern taking over as Taoiseach.

Blair visited the North and gave the go ahead for exploratory contacts between government officials and Sinn Féin.

A third year of violence on the Garvaghy Road brought a renewed call for a proper policing service in the Six Counties and an end to Orange Order parades being forced through nationalist areas.

On 21 July, the IRA announced its second cessation in three years. Sinn Féin had undertaken a number of political initiatives to bring about this cessation. British Secretary of State Mo Mowlam said she would monitor activity over the following six weeks to decide if Sinn Féin would be admitted to all-party talks scheduled for 15 September.

The IRA statement said:

“After 17 months of cessation in which the British Government and the unionists blocked any possibility of real or inclusive negotiations, we reluctantly abandoned the cessation.

“The IRA is committed to ending British rule in Ireland. It is the root cause of divisions and conflict in our country. We want a permanent peace and therefore we are prepared to enhance the search for a democratic peace settlement through real and inclusive negotiations.”

In August, an international decommissioning body was set up to deal with the weapons issue. Sinn Féin signed up to the Mitchell Principles and entered all party-talks. The Ulster Unionists joined the talks, but the DUP stayed away.

In October, Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness met Blair for the first time at Stormont Castle buildings.

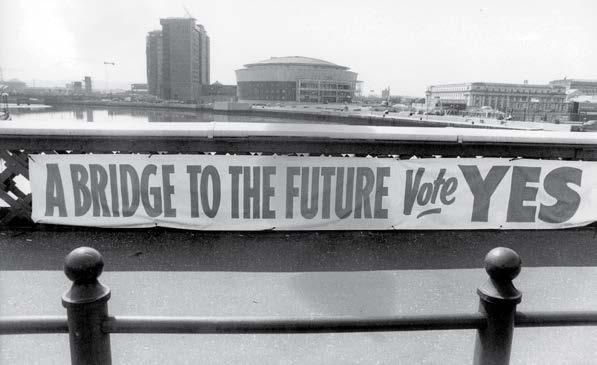

• 1998: Referenda North and South vote overwhelmingly for the Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement was signed on 10 April, with Sinn Féin members endorsing it at the party’s Ard Fheis in Dublin on 10 May 1998.

On 22 May, The people of Ireland, in referenda North and South, voted overwhelmingly in favour of the Good Friday Agreement. �

Telling the horrific brutality and murderous campaign against republicans carried out during the Civil War by the authorities of the British-founded state.

ONLY

POSTAGE

Dorothy Macardle’s tense, restrained and true story of how men and women, boys and girls, fought for the freedom and honour of Ireland and of how, despite almost incredible torture and brutality, they refused to admit defeat.

Margaret Buckley’s story of the hundreds of women Republican prisoners locked up by the Free State in 1922 and 1923.

Margaret Buckley was a Republican activist, prisoner of war, trade unionist and President of Sinn Féin 1937-1950, the first Irish woman to lead a political party.

MARGARET BUCKLEYReflecting over the quarter of a century since those momentous days of April 1998 and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, PEADAR WHELAN, then An Phoblacht’s Northern Editor, wonders at the enormity of what was achieved.

In the North during those years leading up to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, the political landscape was dominated by the Orange Order and its bedfellows in Loyalist paramilitary groups and their demands to march over the rights of national ist citizens in Garvaghy Road, Derry, Ardoyne, and the Ormeau Road in Belfast.

Nationalists were still being targeted by these loyalist gangs, while the unionist political leadership turned a myopic eye to this violence and refused to engage with Sinn Féin, an attitude that was supported by the pro-Unionist governments in London and Dublin.

And while the IRA had reinstated its cessation of military operations in August 1997, in the months after general elections in Ireland and Britain that brought Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair to power, the mood music, as they say, wasn’t good.

Yet, as the parties, under the stewardship of US appointed George Mitchell, gathered in Stormont, there was a curious optimism seeping out from the negotiations.

And this optimism obviously whet the appetite of the international media as truckloads, and I mean truckloads, of journalists set up camp in the car park and forecourt area of Castle Buildings where the talks were being held.

Castle Buildings are the nondescript administration

blocks for the various ‘government’ departments, so these history making talks weren’t taking place in the splendour of Stormont Castle nor the opulent surroundings of Parliament buildings. No, they were filtered down into third class steerage.

On the one or two occasions that I, as Northern Editor, was required to go to Castle Buildings, I was struck by the darkness and functionality of the place. I was also surprised at the lack of any obvious or ‘in your face’ security.

As I drove to Stormont on Good Friday itself with some research material that the Sinn Féin negotiators needed, I was greeted by one of the Sinn Féin administration team and escorted through halls that were dimly lit and even though it was a bright spring day, there was this sense of depression in the soulless corridors.

At this point, the Agreement had actually been signed and photocopied editions were flying about like confetti and, in

time honoured fashion, those with an eye to the occasion and the historical significance of what they were part of were running about, cornering Gerry Adams, Martin McGuinness, Bairbre de Brun, Joe Cahill, Francie Molloy, Dodie McGuinness, Gerry Kelly, and anyone else who had the energy to hold a pen for an autograph.

One of the things that struck me was the camp beds which were lying in a corner of one of the suite of rooms the party were using, evidence that people were literally burning the midnight oil in their efforts to thrash out some sort of consensus.

However, the big bizarre moment for me occurred when, out of the blue, Marjorie ‘Mo’ Mowlam strode into the room looking for “Gerry and Martin” who were ensconced with some colleagues working on some media points or whatever and just planked herself in the middle of it all.

Looking back on that time, and particularly remembering the occasion, there was an enormous sense that Sinn Féin

These history making talks weren’t taking place in the splendour of Stormont Castle nor the opulent surroundings of Parliament buildings. No, they were filtered down into third class steerage• An Phoblacht’s Northern Editor, Peadar Whelan on a white line picket calling for respect of Sinn Féin's vote, Andersontown, Belfast, June 1996

had achieved something of political significance, despite the array of anti-republican forces aligned against them, and this became clear in the series of briefings involving activists packed into halls and meetings places across the North.

An example of the opposition the party faced, which was reported during one briefing, was when Sinn Féin tried to solicit SDLP support for the release of prisoners, only for Seamus Mallon to retort snottily “We have no prisoners”!

And these gatherings seemed to underscore the contradiction at the heart of the Agreement, because even though it marked a positive move forward the spectre of Paisley hovering over the newly agreed accord told us that, at its heart, unionism was not for moving.

The 1974 Ulster Workers Council (UWC) strike, instigated by Paisley and other diehard unionists to destroy the Sunningdale Agreement, echoed through the memory banks of those of us old enough to have experienced it. Whatever opportunities for progress the Good Friday Agreement offered were still set against the activities of those who perpetrated the mass killings in Omagh, only months after the accord was agreed.

The Drumcree marching dispute led to the loyalist killing of at least 10 people, not least the Quinn brothers Richard (10), Mark (9) and Jason (8) burned to death in their Ballymoney in July, as well as the killing of solicitor Rosemary Nelson in March 1999.

Of course, underpinning all this was the refusal of David

Trimble’s unionist party to fully embrace the deal and effectively treating the Sinn Féin mandate as ‘second class’, so the assembly, voted for by the Northern electorate only met in fits and starts.

On reflection, there has been a sense of déjà vu with the DUP stonewalling over re-forming the Executive, but as Gerry Adams would say we always knew it would be “a battle a day”. �

Sinn Féin tried to solicit SDLP support for the release of prisoners, only for Seamus Mallon to retort snottily, “We have no prisoners”!• Drumcree marching dispute and the unionist parties refusal to fully embrace the deal lead to loyalist killings not least the three Quinn brothers burned to death in Ballymoney, as the killing of solicitor Rosemary Nelson

In November 1998, I was released as a Good Friday Agreement (GFA) political prisoner. An election for members of the Assembly had taken place four months earlier in June ‘98 and Stormont only existed in “Shadow” form.

A few months after my release, in April 1999, I found myself on a journey from Derry to Belfast that had not been part of my post prison dream plan. I was in a car on my way to start my first post-prison job as a Sinn Féin researcher in Parliament Buildings, Stormont – “Stormont”! I shook my head more than once that morning and when I walked into that building, I shook it more!

Every day, Republicans working in Stormont would drive along the Prince of Wales Avenue, past the statue of Carson, park the car next to where Craig is buried, walk into Stormont Parliament Building with Britannia written on the roof on days when there was not one, but two union flags flying and walk past a statue of Craig at the top of the stairs on the way to our offices.

I comforted my resistance knowing that all Republicans who entered Stormont would work as I would, diligently to advance a political process that would lead to an Ireland of Equals. The Assembly was a transitional to something better.

However, initially one could not help but feel like we did not belong. It wasn’t long before I felt that Unionists certainly believed that I and my ilk were in ‘their’ traditional power base. We were once again made to feel unwanted and unwelcome. Unionists even refused to enter the same elevator that we were in and if one stopped and they were already in it, they turned and faced the wall!

In the canteen, Unionists eventually cornered themselves into an apartheid-type sitting area – a section of the canteen where they congregated and became physically, deeply uncomfortable when confident Republicans sat where we wanted, when we wanted.

The only thing that all of that ever did for me was to remove doubts and reinforce “that thought that says you’re right”. I knew Republicans were right to be there – there were no ‘no-go’ areas for us. The days of “a Protestant Parliament for a Protestant People” were well and truly over, done with, gone.

For the first Assembly team of Sinn Féin activists, it was without doubt a steep learning curve. We had to collectively deepen the party’s capacity for assuming government responsibility as we took opportunities to learn the trade of efficient governing arrangements.

Before the GFA, the Six Counties had only six depart-

ments. The new Assembly established ten, along with the GFA Strand-2 all-Ireland Implementation bodies and areas of co-operation.

Sinn Féin secured two ministers, Martin McGuinness was appointed Education Minister and Bairbre de Brún appointed Health Minister. Sinn Féin now needed to ensure cohesion and connect the Sinn Féin Stormont team with the wider party. I was moved from a research role to a new position to help do that.

Whilst our Ministers objected to positions at variance

We were once again made to feel unwanted and unwelcome. Unionists even refused to enter the same elevator that we were in and if one stopped and they were already in it, they turned and faced the wall• Carson statue, on Prince of Wales Avenue, Stormont • (front) Martin McGuinness and Bairbre de Brún; (back) Alex Maskey, Conor Murphy, Gerry Adams and Mitchel McLaughlin on the way to nominate ministers in the Assembly, November 1999

with party policy, our limited political strength at that time rendered it difficult for our ministers to overturn them.

MLAs Conor Murphy, Alex Maskey and I constituted the Sinn Féin Stormont management committee and I admit at times to having both of their heads fried. But we had to be mindful to protect the integrity of our party and protect our core ideas against being compromised by pragmatic realities of ‘realpolitik’.

All of us had to learn about Annual Budgets, Quarterly Monitoring Rounds, Bids, Standing Orders, Private Notice Questions, Legislation, First, Second, and Committee Stages, Amendments, the Assembly Business Committee, the Order Paper, Nil Returns, Written Procedures etc - bureaucratic details that at times challenged us to our outer limits.

Stormont bureaucrats bombarded us with paperwork, documents, rules, procedures, protocol – the details of which we had to know, but which are the yawning but necessary nuts and bolts to get around those who wanted to maintain the status quo which we were out to change. We had to be mindful of the dangers of institutionalisation. I told my husband that I was in more danger of being institutionalised in Stormont than I was in jail.

All Sinn Féin activists in the Assembly, elected and non-elected, had to learn the craft of civil service tactics. We had to remain mindful not to be blinded when civil servants created a row when we insisted on the Sinn Féin approach to issues.

There were senior civil servants who were incensed at Sinn Féin MLAs on scrutiny committees “flouting conventions” demanding earlier draft papers and access to documents; incensed at party MLAs doing their job diligently, scrutinising and ensuring democratic accountability – officialdom objected to questions on matters that they regarded as “the exclusive preserve of the civil service”.

Martin and Bairbre did sterling work. Martin for exam-

ple secured the purchase of the former St. Joseph’s Training Centre in Middletown Co. Armagh and established an all-Ireland Centre of Excellence in the education of children throughout Ireland with Autism.

Bairbre made advances on an all-Ireland Helicopter Emergency Medical Service and created a framework within which an all-Ireland infrastructure for joint programmes in Clinical Cancer Research was developed.

Those moves sowed the seeds of the debate for single issues strategies in Health, Education, Agriculture etc, as opposed to the cost incurred in having two separate health and other systems operating in this small island.

The argument for a planned and prepared process of reintegration towards reunification was accelerated on the back of the Assembly work done by MLAs like Martin, Bairbre, and indeed others, which ultimately resulted in the Sinn Féin Green Paper on Irish Unity.

MLAs in the Assembly linked with TDs and party representatives on the Implementation Bodies, to establish joint working mechanisms that ensured a strategic connection between their shared briefs, these links that have strengthened, deepened and became more joined up over preceding years.

The ‘reality sandwich’ is that without Republicans’ input, the change created and opportunities maximised through republican engagement in the Assembly, Executive, All-Ireland Ministerial Council, and Implementation Bodies, would not have happened and that cannot be underestimated.

The first Sinn Féin Assembly team 25 years ago opened previous untapped and new means by which republican politics were mainstreamed. That team was influential in creating the road map upon which more Republicans in the North and throughout Ireland walked and which ultimately lead to making the impossible, possible – Michele O’Neill, Sinn Féin First Minister in waiting, and the real potential of the first woman Taoiseach – Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald. �

I told my husband that I was in more danger of being institutionalised in Stormont than I was in jail• In the new Assembly Martin McGuinness was appointed Education Minister and Bairbre de Brún appointed Health Minister

Former Sinn Féin vice president PAT DOHERTY was part of the Sinn Féin negotiating team that concluded the Good Friday Agreement. Here he takes us from the first meetings in Castle Buildings to the long Good Friday that culminated in the historic agreement.

In the aftermath of the restoration of the IRA cessation in 1997, the first meeting between the British Government and the Sinn Féin leadership took place in Castle Buildings, Stormont estate on 13 October 1997. It lasted less than 30 minutes.

On the British Government side were Prime Minister Tony Blair, Mo Mowlan, Paul Murphy, Jonathan Powell, Jonathan Stephens from the Northern Ireland Office, and two note takers. Present from Sinn Féin were Gerry Adams, Martin McGuinness, myself, and Siobhan O’Hanlon. There was a table between the two delegations with some flowers and cakes on it.

The meeting opened with a short exchange and Gerry Adams introduced our delegation. Gerry presented Tony Blair with

Gerry presented Tony Blair with a Celtic cross made out of pressed Irish turf, and told Tony Blair that, “This was the last bit of Irish soil we wanted the British Government to own”

a Celtic cross made out of pressed Irish turf, and told Tony Blair that, “This was the last bit of Irish soil we wanted the British Government to own”.

Tony Blair thanked Gerry and said he has heard that, “You have the gift of saying the hard thing softly”, and so the tone was set for all of the numerous meetings that led to the Good Friday Agreement.

During the course of the discussions, Tony Blair told us that he “understood more about history than you think” and then said, “I have read about you guys, about your youth etc, and those from other communities, I will deal with you in good faith but I have to have that back”.

We did not directly respond to the comments, but we had done a bit of reading our-

selves and we were certainly committed to good faith negotiations.

Gerry Adams told the British delegation that, “There was a need for constitutional change and that the British Government have to be the engine for change”. Martin McGuinness told the British delegation that one of the issues was the mindset of the Unionist parties, summed up by the previous leader of the UUP, Jim Molyneaux, who said in relation to the last ceasefire, “That it was the most destabilising thing that had occurred”, adding, “The British Government need to recognize that this is a political problem that needs to be resolved”.

Martin continued stating that “We are sitting in a room with people who will not speak to us and some other parties”. Martin concluded that, “The people of Derry are not interested in an apology for Bloody Sunday, that they want an International Public Inquiry” I added that, “Partition can be ad-

dressed, there is nothing more that the people of Ireland want”.

Tony Blair concluded the meeting by saying, “The political will is there, the only thing I stress again, we would be in an impossible situation is violence began again, subject to that, there will be equality of treatment, we want a settlement which is lasting”.

The Irish Government under the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, had appointed three senior civil servants to be his leading personnel in the negotiations that led to the Good Friday Agreement. They were Paddy Teahon, Secretary General of the Department of An Taoiseach; Dermot Gallagher, Secretary General of the Department of Foreign Affairs; and Tim Dalton, Secretary General of the Department of Justice. In a recent conversation with my colleague Rita O’Hare, we both agreed that we were blessed with having those able men to work with. Martin Mansergh was also involved as the Taoiseach’s Special Advisor.

It was clear right from the start of the negotiations that there were great tensions within and between the various Unionist parties. At the start of the negotiations under the American Senator George Mitchell, the DUP party walked out at the decision to include Sinn Féin. The UUP Party arrived at the talks flanked by various loyalist parties to bolster their credentials.

Castle Building Stormont estate was the venue for the negotiations, and it was not a

On the morning of Good Friday, all our delegation were given the latest updated draft of the Good Friday Agreement. We were all very tired. Some of us had tried to sleep on available chairs, others like Gerry Kelly had slept on the floor, others again got no sleep

well-constructed building for talks. There seemed to be double swinging doors every 10 yards in all the various corridors. I went through one of those double swing doors one late morning to see two Unionists having a big row at the other swing door. One of the Unionists, a tall man, was very clearly telling the other man that he was nothing but a “jumped up grocer”. He then took a swing at him but missed. Both were elected as MLAs to the first Assembly Election in June 1998.

On another occasion, Mo Mowlan came through the swing door next to the Sinn Féin office wearing an Easter Lily, well pinned on, only to meet Martin McGuinness who, without asking her, took Easter Lily from her asking her did she want a Unionist walk-out.

One of my responsibilities was around the release of republican prisoners and to this end, we were dealing with NIO Officials. These officials did not want prisoners released until they had finished their sentence. We wanted them all out the following

morning. At the end of the negotiations, the Good Friday Agreement set a release date of two years.

Another responsibility was the briefing of the media from time to time and doing many meetings with our base around the development of the negotiations. We also did as many meetings as possible with the other parties that would talk to us.

I found the SDLP particularly arrogant, although John Hume was always pleasant. Seamus Mallon told us on one occasion that the SDLP did not have any prisoners. They also did not have a clear ideological core, hence their current standing in the Six Counties.

Senator George Mitchell was very straightforward in any of the dealings we had with him, telling us on the afternoon of Good Friday, “When you have the numbers, take the vote”.

On the morning of Good Friday, all our delegation were given the latest updated draft of the Good Friday Agreement. We were all very tired. Some of us had tried to sleep on available chairs, others like Gerry Kelly had slept on the floor, others again got no sleep.

Gerry Adams told us all to read the section we were involved in negotiating and then read all of the document. I was sitting beside Francie Molly when he asked me, “How do we judge all of this document?”. I said that if we get if across a certain line, we can find energy and commitment to the many issues in order to push them on.

After an hour or more, we both finished reading and Francie said, “I think we have just crossed the line”. I replied saying, that I thought we had just landed on the line. Our delegation was told that there would be a plenary session of all parties at 12 noon. Of course, it did not happen until much later that evening.

The Agreement was announced that eve-

ning with the hand of history on everyone’s shoulders. Referendums were held North and South in May 1998, being carried in both jurisdictions and then the Assembly Elections were held in June 1998.

I was elected as an MLA for West Tyrone. Unfortunately, the horrendous Omagh bomb exploded on 15 August 1998, with the loss of 28 people and two unborn twins and many, many more were injured.

Even though we had secured an agreement, the Good Friday Agreement, for a new way forward, it was very clear that we had still a lot of political work to do. �

Pat Doherty was Sinn Féin vice-president from 1988 to 2009. He represented West Tyrone as an MP from 2001 to 2017, and as an MLA from 1998 to 2012.

BY ROY GREENSLADE

BY ROY GREENSLADE

Should anyone doubt that the ‘independent’ British press is willing and able to act on behalf of the British state, then its collective enthusiasm for the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) should surely quieten the doubters.

The London-based newspapers had plenty of form, of course, in supporting successive governments, of whatever stripe, during the 28-year war against Republicans in the north.

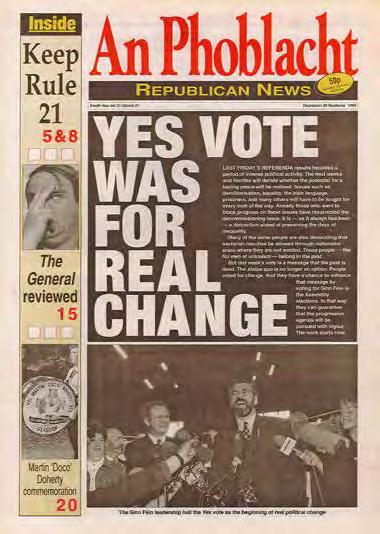

But that joint call for a referendum ‘yes’ vote in 1998, by Westminster and Fleet Street, has significant implications for the present. Firstly, it illustrates that the government can, if it sets its mind to it, successfully confront Unionist intransigence. Secondly, it shows how the British media, when properly motivated, can be persuaded to do its government’s bidding.

Before we take those lessons to heart in the current context, let’s consider how those newspapers dealt with the issue at the time. Despite having relatively small sales in Ireland, north and south of the border, most editors did not so much urge Irish people to support the GFA as order them to do so.

In parallel, they sought to convince their readers in England, Wales and Scotland –who were non-voters – that securing acceptance of the Agreement would benefit Britain as a whole. Peace was at hand.

The popularity of Prime Minister Tony Blair, then enjoying a honeymoon period after sweeping to power in a landslide less

than a year before, undoubtedly played a major part in the press’s attitude.

But editorial zeal for the GFA had a much more profound rationale, which the British media dare not admit, neither to themselves nor the public they purported to serve. Here, for once, that elephant-in-the-room cliché is relevant.

Over the course of the war, Britain’s security forces had failed to crush the IRA while Westminster’s attempts to enforce peace on its own terms had failed just as miserably.

Therefore, the Agreement represented what politicians of all parties, and journalists of all persuasions, regarded as the last, best hope for a lasting peace that their previous belligerence had helped to prevent.

Editors were aware that there was, to quote The Times’s apposite understatement, a “sense of distance” between the citizens of Britain and those identifying as British in Ireland’s northern counties. With that in mind, they recognised that they were on safe ground in disregarding loyalist antagonism.

They were also conscious that the buyers of their newspapers were eager for the conflict’s conclusion and there was no chance of them losing readers by taking the government’s side

So, in the days before the poll, in a remarkable sign of unity, papers of the political left, right, and centre, carried the same message. There was not a scintilla of difference between the Labour-supporting Daily Mirror and the Tory-cheerleading Daily Mail

The Daily Express warned: “Don’t reject this bid for peace.” The Sun agreed, running three successive leading articles supporting a ‘yes’ vote. It also devoted a front page to an exclusive article written by US President Bill Clinton, headlined: “Say YES to peace.” The Sunday Times was adamant: “Both sides should grasp this settlement with enthusiasm and move forward on behalf of Ireland, Britain and future generations.”

The Daily Express warned: “Don’t reject this bid for peace.” The Sun agreed, running three successive leading articles supporting a ‘yes’ vote. It also devoted a front page to an exclusive article written by US President Bill Clinton, headlined: “Say YES to peace.”

The Guardian pointed out that “wholly negative” Unionists who opposed the deal offered no “alternative solution to Ulster’s woes”. It cited Joe Cahill’s support for the GFA, “after more than 50 years of struggle”, as a welcome sign of “a genuine shift” by “the republican movement.”

The Times chose a very different revolutionary to make its case, by quoting Antonio Gramsci’s famous statement about the need for optimism, even if it was only “optimism of the will.” Italian Marxist philosophers do not figure too often in Britain’s venerable paper of record. The Daily Mail, without mentioning Gramsci, echoed the sentiment: “It is better to venture in hope than surrender to fear and despair.”

Only the Daily Telegraph registered its reluctance to endorse the Agreement, viewing it in less than positive terms. In its early risible misreading of the situation, it speculated that Gerry Adams would find it difficult to convince Sinn Féin to back the Agreement.

It found much to dislike, such as the early release of prisoners and the mooted disbandment of the RUC, saluting the force’s “loyalty to the United Kingdom”. It was also angry with the Tory opposition, led by William Hague, for supporting the Agreement. “Why”, it asked, “does he not listen to Mrs Thatcher?”

The paper, in contending that the IRA “has been unable to defeat the RUC operationally”, was frustrated that Sinn Féin was “doing well in the battle of the airwaves.” How dare that party succeed in articulating its case so well!

Indeed, one of the notable features of the Telegraph’s hostility to Irish republicanism, shared by several other papers, was that having long demanded that republicans should follow a political rather than a military path, it could not stomach the fact that Sinn Féin proved so adept at the task.

But, after days railing against both the concept and the reality of the Agreement, it grudgingly came into line. Its stablemate, the Sunday Telegraph, reluctantly concluded: “There may be occasions in future when it is right to say ‘No’; but Friday’s referendum is not one of them.”

That leading article, which expressed the views of high Tory right-wingers, carried the headline “faute de mieux”, meaning “for want of a better alternative”. It was, in other words, a lame admission that it, and the naysaying Unionists, had nothing to offer.

Perhaps the most revealing point made by the Telegraph was its statement about having “grave reservations about the peace process.” Quite so. What irked it most was the failure of the “war process”.

It was noticeable that the rest of the English press (for that is what it was, and is) gave short shrift to the Orange Order’s rejection of the Agreement, noting it only in passing. As for the DUP’s leader, Ian Paisley, several papers ignored him altogether.

Then again, they also turned a blind eye to Republicanism’s part in the 700 days of ne-

gotiations which led up to the Good Friday. Instead, papers chose to lionise David Trimble, with The Times referring to his “personal triumph” in persuading so many Unionists to back the Agreement. Fair enough, but personal triumphs from the republican side were entirely overlooked.

Re-reading the newspaper output in spring 1998 is a reminder of deep-seated British exceptionalism. There were several instances of the kind of blind ignorance that, from an Irish perspective, made for painful reading. For example, a Labour MP, and member of the Commons select committee on Northern Ireland, Martin Salter, offered his wisdom to readers of his local evening newspaper.

The people of Ireland, he told them, were “the prisoners of their troubled history”. This has become something of a British mantra since the plantation, if not before, in which the architect of that troubled history is eliminated from the scene.

On the same theme, The Sun told its readers that “a No vote will plunge the province

back into the Dark Ages.” If we obligingly overlook the misuse of “province” and ignore the hyperbole, we cannot disregard the message: unlike Britain, Ireland remains uncivilised, and that is no-one’s fault but its own. History is erased. Britain is not responsible for the creation of an unstable statelet based on religious division.

There were many similar examples, but let us turn away from the myth-making to consider the real import of that moment 25 years ago when a united British press acted as the propaganda arm of Westminster and, even more importantly, when Westminster briefly stopped playing the Orange card.

Ever since the DUP refused to comply with the democratic will of the Six Counties, firstly by scorning the people’s vote against Brexit, secondly by opposing the protocol, and thirdly by defying the people’s wish to see a Stormont assembly, Westminster has let the tail wag the dog.

Rather than act on behalf of the majority, it has allowed the minority to dictate events in the North. As for the press, it has returned to its traditional position – the one it has employed ever since Partition – of turning a blind eye to the political realities of life in a place it laughably insists is part of the United Kingdom.

But should Westminster and its compliant press set their mind to it, as they did over the Good Friday Agreement, they could take on loyalism, could they not? �

Roy Greenslade is a journalist, author and former Professor of Journalism at City, University of LondonThe Sunday Telegraph, reluctantly concluded: “There may be occasions in future when it is right to say ‘No’; but Friday’s referendum is not one of them.”• The agreement represented what politicians and journalists of all persuasions, regarded as the last, best hope for a lasting peace that their previous belligerence had helped to prevent

Mícheál Mac Donncha argues that despite the challenges to the Good Friday Agreement over 25 years, it has opened the potential for a path way to a United Ireland.

An era is defined as a long and distinct period of history. Three such eras can be clearly discerned in the history of the Six-County state: from its foundation in 1921 to the outbreak of armed conflict in 1969; the years of armed conflict up to the mid-1990s; and the 25 years since the signing of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

The last 25 years have been defined politically by that Agreement, the efforts to implement it, the progress, the successes and failures, the stalling, the advances. Underlying all are the principles of equality and inclusivity enshrined in the Agreement. While the Assembly and the Executive have stumbled from crisis to crisis the peace has held firm. Peace and the principles of the Agreement reached on 10 April 1998 have become deeply embedded in the social, economic and cultural life of Ireland.

That this is so, in spite of all efforts to thwart the implementation of the Agreement, is no small achievement. In An Phoblacht on 29 July 1999, Gerry Adams wrote:

“From the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in April 1998 until the UUP prevented the transfer of power and the establishment of the institutions two weeks ago - a period of almost 16 months - the peace process has limped from one unionist-induced crisis to another.”

Months became years and every step along the waythe establishment of an Executive that included Sinn Féin ministers, policing reform, demilitarisation, all-Ireland institutions, Irish language rights and more - Unionist road-blocks were set up, usually supported by the British government. But change happened.

David Trimble was leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, the majority party of unionism, when he endorsed the Agreement. He was rightly credited for doing so, but he failed to fully embrace it and to promote it to his followers

and he never ceased looking over his shoulder at his antiagreement DUP rivals.

The UUP was in continuing crisis and the process of implementing the Agreement paid the price. Then, when the DUP had overtaken the UUP as the main unionist party, they too realised that the Agreement was the only show in town, their only route to political office.

There was a decade of the Executive with DUP First Ministers, beginning with Ian Paisley, and Sinn Féin Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness. Peace was consolidated, the Agreement was firmly in place, but its implementation was slowed to a snail’s pace by the DUP.

The ‘cash for ash’ scandal involving DUP First Minister Arlene Foster was the last straw for Sinn Féin and, in January 2017, Martin McGuiness resigned as Deputy First Minister. His resignation letter is very instructive about how the DUP had behaved since they entered the Executive:

“Over ten difficult and testing years, in the role of Deputy First Minister, I have sought with all my energy and determination to serve all the people of the North and the island of Ireland by making the power-sharing government work.

“Throughout that time, I have worked with successive

Over ten difficult and testing years, in the role of Deputy First Minister, I have sought with all my energy and determination to serve all the people of the north and the island of Ireland by making the power-sharing government work

�

MARTIN McGUINNESS

DUP First Ministers and, while our parties are diametrically opposed ideologically and politically, I have always sought to exercise my responsibilities in good faith and to seek resolutions rather than recrimination. I have worked tirelessly to defend our peace process, to advance the reconciliation of our community and to build a better future for our young people.

“At times, I have stretched and challenged republicans and nationalists in my determination to reach out to our unionist neighbours. It is a source of deep personal frustration that those efforts have not always been reciprocated by unionist leaders. At times, they have been met with outright rejection.

“The equality, mutual respect and all-Ireland approaches enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement have never been fully embraced by the DUP. Apart from the negative attitude to nationalism and to the Irish identity and culture, there has been a shameful disrespect towards many other sections of our community. Women, the LGBT community, and ethnic minorities have all felt this prejudice. And for those who wish to live their lives through the medium of Irish, elements in the DUP have exhibited the most crude and crass bigotry.

“Over this period, successive British governments have undermined the process of change by refusing to honour agreements,

refusing to resolve the issues of the past while imposing austerity and Brexit against the wishes and best interests of people here.”

Just how far the DUP went in acting against the interests of the people they were supposed to represent and against the Agreement was revealed in the Brexit shambles. A majority in the Six Counties voted to remain in the EU. But the DUP had gladly provided its party funds to the Brexit campaign (already over its permitted spending limit in Britain) to lavish on a final advertising splurge in England that helped to get the vote to leave the EU over the line. This left Ireland potentially further divided by Brexit with one part in the EU and one part outside it.

While the Executive was restored in 2020, the DUP was wedded to Brexit and its relationship with the British Tory government. The Executive became a hostage to that fraught DUP-Tory, love-hate relationship.

The DUP thought that Brexit would trump the Good Friday Agreement and they would get their way. They thought the Tories’ love for ‘our precious Union’ would outweigh the British government’s need to get international trade deals and rebuild some form of relationship with the EU. The Protocol, which simply recognises the reality of the island of Ireland and the principles of the Good Friday Agreement, proved that the DUP were wrong. And so in February 2022, the DUP pulled the plug on the Executive yet again.