Demand for Irish Unity growing FULL REPORT SEE INSIDE

THE CHANCE TO BEGIN ANEW - THE GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT AND THE FUTURE PAGES 8-12

THE COMMISSION ON THE FUTURE OF IRELAND

PAGES 17-23

THE CHANCE TO BEGIN ANEW - THE GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT AND THE FUTURE PAGES 8-12

THE COMMISSION ON THE FUTURE OF IRELAND

PAGES 17-23

The local government elections in May have dramatically increased the process of transformation which last year saw Sinn Fein emerge as the largest party in the Assembly and Michelle O’Neill as First Minister designate. Previously, in the Westminster 2019 election pro-unity MPs for the first time outnumbered pro-Union MPs. The May election produced a historic number of firsts for Sinn Féin and for the pro-unity position. The outcome marks a huge symbolic shift in the northern political landscape.

For the first time the pro-unity vote was greater than the pro-union vote. According to several different sources the pro-unity vote was 308,624 compared to 281,196 for the pro-union position. A century ago the six county state was carved out of Ireland by the British for unionism as the geographical area best able to guarantee unionist numerical dominance. The May election spectacularly changed that.

For Sinn Féin the result saw the party’s vote share increase to 30.9% and it received the greatest number of first preference votes. Every electoral area contested by Sinn Féin witnessed an increase in the party’s vote share, with more Councillors elected than ever before – 144.

Sinn Féin Councillors were elected in areas where there has never been a Sinn Féin representative and according to Chris Donnelly in the Irish News

the party grabbed seats from all quarters “including nine seats from unionist parties and three seats from Alliance and the Greens.”

So, well done to everyone involved, our 162 candidates, their families, and our election teams.

Sinn Féin stood on its commitment to Irish Unity, our record of work in the Councils, our defence of the Good Friday Agreement and on the imperative of getting the power sharing institutions back up and running. Michelle O’Neill demonstrated her commitment to be a First Minister for all.

The election results were a good day for United Irelanders. But they also reflect the substantial task that faces us if we are to achieve our goal of Irish Unity. This requires those of us who favour unity persuading those who don’t, or those who are ambivalent, that unity is the right outcome.

The new Ireland has to be shaped by all of us, collectively, and that includes by those who identify as pro-union. They have to be involved in shaping this.

The unionist population and its political representatives working with the rest of us on this island is the surest guarantee that their cultural identity – British and unionist –will prosper and be protected in a new and independent Ireland.

The safeguards that are in the Good Friday Agreement with respect to identity, cultural and language rights will continue in a new Ireland. Working with the unionists in the Assembly and the other parties and independents is also part of working toward a new agreed Ireland.

This will not be easy. At this point the

British and Irish governments are against constitutional change and against the unity referendums. So, are the unionist parties. There are many different reasons for this. For example, the British government is a unionist government.

The Irish government is worried about a national re-alignment of politics in which the establishment parties will lose their dominance. For this reason Leo Varadkar is insisting that the priority must be to make the Good Friday Agreement work and restore the Assembly before any “conversations about what change we might be able to make” can happen.

Uachtarán Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald criticised this position. She said: “We all know full well that we need the Executive back up and running, a functioning Assembly, the East West bodies, the North South bodies up and working as well. But you can do all of those things and at the same time have the conversations, the kind of engagement and planning I’m describing.

“Political systems and political leaders have to have the capacity to multi-task and do several important, critical things at the same time. To advance an argument that we will not prepare for the medium and long term future simply because we have challenges in the present, that doesn’t stack up. That’s not responsible politics in my view.”

As for the immediate term, we have much work to do.

A new, pluralist, progressive Ireland is possible, but not inevitable.

The monolith of political unionism is no more. The ability of the DUP and others to permanently

The new Ireland has to be shaped by all of us, collectively, and that includes by those who identify as pro-union. They have to be involved in shaping this.

veto the process of change has been ended. That’s why it makes sense for them to get involved in discussions about managing future transitional arrangements. Refusing to talk won’t make the conversation go away. Workers and families in Ireland, north and south, want a better society for themselves and their families.

They have been failed by partition, and by unionist and gombeen politicians. We can do better, and we deserve better. Constitutional change and Irish unity are on the political horizon.

The future is bright. A new, rights-based, national democracy is the way forward. That prospect is now within touching distance. So, whether you are ‘Catholic, Protestant or Dissenter’ or none of those, get involved and help make even more change happen.’

The Irish government has a constitutional obligation, and it is also a co-guarantor of the Good Friday Agreement - to prepare for unity. That means the Irish government should establish a Citizens’ Assembly or series of such Assemblies to begin the work of planning. Sinn Féin is not suggesting that the unity

referendums should take place immediately but the Irish Government should seek a date now which allows for inclusive preparation to begin. And that preparatory work should start now.

The people of the island of Ireland have the right to self-determination. We have the right to determine our own future, without outside interference, peacefully and democratically. That is a central part of the Good Friday Agreement.

Without Unity, the North is at risk of being left behind, outside the EU, and divided from the rest of Ireland by a Brexit border. The people of the north continue to be denied rights on issues such as justice, legacy, marriage equality, and reproductive rights that are available in England, Scotland, Wales and the rest of Ireland.

Irish Unity can change all of that. Of course, it cannot be a crude exercise of simply stitching North to South and returning to business as usual. We need to build a New Ireland. An Ireland in which equality and rights are guaranteed, cultures respected, and the diversity of our identities embraced.

Citizens want us to deliver on commitments. They want the promise of change and the hope for a new future to be more than rhetorical. We need to keep building greater political strength. The momentum is with those who want change but the big challenge facing Irish republicans is how we use our growing strength, not least to secure and win the Good Friday Agreements unity referendum.

Sinn Féin is not suggesting that the unity referendums should take place immediately but the Irish Government should seek a date now which allows for inclusive preparation to begin. And that preparatory work should start now.

By Colin Harvey

By Colin Harvey

The intensity of the focus on Irish reunification since Brexit is undeniable. The extent of ongoing work is well documented. Books, articles, opinion pieces, research projects as well as multiple new initiatives suggest increased attention to practicalities. The unity debate is making the civic and political weather - whether acknowledged or not – and these efforts are all to be nurtured and encouraged. The primary question for those who want to advance this project is how to complete the task. Although I understand why it is used, the language of inevitability can be problematic. If something is inevitable, why bother to do the work? It is going to happen anyway, right? The difficulty with this line of thought is that progressive movements around the globe have heard this type of thinking before. The reality is that the propped-up nature of the North within

the Union may well persist without determined political and civic intervention to bring a united Ireland about. How will a united Ireland be achieved in the circumstances of 2023? A candid starting point is recognition of the history of failure thus far. There is little sense in avoiding this harsh initial assessment. Ireland is still partitioned and divided in fundamental ways. Even with the Protocol/Windsor Framework, the island is also now separated by an external border of the EU. These contexts require lesson learning and further strategic reflection about productive ways forward.

The work has been reframed by the political and legal consequences of the Good Friday Agreement. The route to reunification flows through that document and the 25th anniversary provided a welcome opportunity to reaffirm and renew the commitment to constitutional change. What does that mean? The pathway to exercising the right to self-determination is

within the framework of the Agreement. Not everyone is comfortable with that prospect. None too subtle attempts to hardwire in a unionist veto are plain in current rhetoric around the ‘principle of consent’. This has not survived direct contact with legal reality or expert analysis. The discomfort about what the Agreement requires includes unsuccessful attempts to alter the ground rules and framing. That is likely to continue, aided by those whose primary goal is the Agreement’s destruction. Expect sharp contestation at every stage. The frequent references to a ‘settlement’ also encourage the erroneous view that this is the constitutional endpoint. The Agreement combines ongoing effort to build a better society with a firm question mark about the future. Perhaps the most troubling element of recent discussions is the occasional treatment of the constitutional compromise as an irrelevant inconvenience, not to be taken seriously and deferred indefinitely. The privileging of unionist perspectives often obscures the fact that many people opted for the Agreement because of its transitional qualities. More frequent reminders about that are needed as part of a wider rebalancing of the constitutional conversation. The process of getting to the vote presents challenges, particularly given the role accorded to the British government and the Westminster

Parliament, within the context of established constitutional constraints and flexibilities. There continues to be much agonised consideration of the applicable legal tests, but politics will prompt action and any next steps. Even where evidence does emerge that the people of the North want decisive change, international, EU and domestic political pressure will be required. What will a vote for a united Ireland mean? There must be credible answers to the first question that will arise in any doorstep conversation. This matters to everyone, but if the objective is to win over ‘persuadables’ it is vital that comprehensive responses emerge. Those who retain a genuinely open view will take convincing about the merits of change. And this is where discussion of a New Ireland also comes in.

How ambitious will the proposals be? There will be room for dialogue, with many becoming involved precisely because of the transformative potential. While there will be much detailed interrogation of constitutional models and arrangements, there needs to be just as much attention paid to practical social change and the improvement of wellbeing, particularly for those most disadvantaged at present. There are many comparative examples of fine constitutional texts whose words remained paper only. Will progressives be in a position to ensure that proposals for a new and united Ireland do not embed serious impediments to realising societal

transformation? The North demonstrates the impact that vetoes, for example, can have on the advancement of a meaningful culture of rights and equality. Even where legal gains are made, implementation can be an enduring problem if there are hostile institutional cultures.

The Irish government and state must not be passive observers. It is hardly credible to press any British government on criteria for a ‘border poll’, for example, when the Irish government is disinterested. The preparation of an ambitious case for a united Ireland remains essential. It is already the constitutionally mandated outcome. The Irish state has a long and tragic history of avoiding direct responsibility on profound matters of national and public interest. It is to be hoped that it will not repeat that error on this occasion. Orienting the Irish public service towards the advancement of reunification in precise terms would put the preparatory effort on a new footing. The debate is hampered by procrastination and too many interventions deliver no tangible progress towards reunification. Calls for patience that are left as prose on the page and unimplemented scripts with no concrete plan offer little assistance. Governmental action would alter the dynamic. One way to combine the ‘how do you secure

a vote?’ and ‘what do you mean by a united Ireland?’ questions is, at the appropriate time, to adopt an intergovernmental time frame with associated parameters. The British Irish Intergovernmental Conference is the obvious location to raise this matter. That would bring clarity and focus attention where it needs to be, on the content of the propositions and the development of participative processes. Retreating into abstract language that invents additional obscure obstacles is therefore unhelpful and an exercise in avoidance. What is required now is a clear and decisive pathway with practical steps towards the achievement of a united Ireland within a defined time frame. On 22 May 1998, people across Ireland voted for change. In doing so they endorsed a constitutional compromise about Ireland’s future and how it will be decided.

Achieving a new and united Ireland is about giving people a choice once again and ensuring everyone knows the implications of the decision. At this stage, only proactive and complementary civic and political advocacy for reunification will do. There is an onerous responsibility to get this done and make a success of it. In particular, the island awaits an Irish government willing to face into the task and join the many others diligently preparing the ground.

The Irish government and state must not be passive observers. It is hardly credible to press any British government on criteria for a ‘border poll’, for example, when the Irish government is disinterested. The preparation of an ambitious case for a united Ireland remains essential.

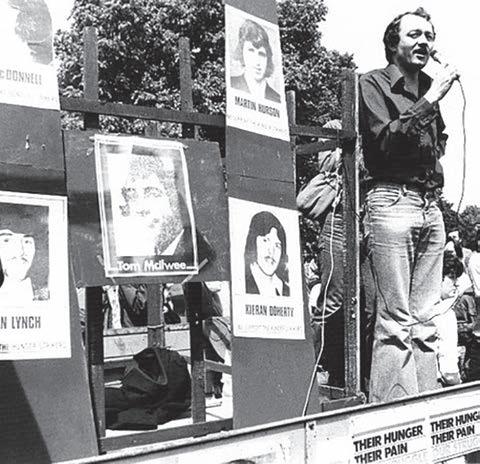

By Gerry Adams

By Gerry Adams

Speaking in Leinster House in a considered contribution to the discussion by the Oireachtas Joint Committee on the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement, former Uachtarán Shinn Féin Gerry Adams set out the background to the negotiations in 1998.

Gerry Adams said:

“I don’t think it is putting it too strongly to describe the Good Friday Agreement as probably the most important political agreement of our time in Ireland. When it was agreed George Mitchel told myself and Martin McGuinness that that was the easy bit. The hard part was going to be implementing it, he said. And he was right. The twists and turns from April 10th 1998 to now have been many.

Currently the institutions are not in place due to the intransigence of the DUP, the machinations of successive Tory governments and unionist efforts to force the EU and Irish government to scrap the protocol.

However, despite these difficulties the success of the Agreement is that there are many people alive today because of it. It brought an end to almost three decades of war. It is seen by many internationally as an example of how deep rooted conflicts can be resolved. Those who still seek to use violence or threaten the use of violence represent the past. So do the securocrats who manipulate the groups involved. They should end their actions and go away. Of course, the Good Friday Agreement isn’t a perfect agreement. It was after all a compromise between conflicting political positions after decades of violence and generations of division. It is also a fact that crucial elements of the Agreement have still not been implemented by the British and Irish governments, including a Bill of Rights for the North; the Civic Forum; a Charter of Rights for the island of Ireland and the British government’s refusal to honour its Weston Park commitment to establish an inquiry into the murder of human rights lawyer Pat Finucane. In addition there is the British government’s refusal to fulfil its commitments and obligations to deal with the legacy of the past and the concerns of families bereaved during the conflict that its legislation, currently going through the

The Tory government has no real investment in the Good Friday Agreement. In fact, its policy is to emasculate the human rights elements of the Agreement. Nonetheless, the new dispensation ushered in by the Agreement has replaced the years of violence which preceded it. It is important to remind ourselves that earlier initiatives - political and military – on the part of the British government and often supported by the Irish government - failed to bring peace because they were not inclusive. They consciously failed to address the causes of conflict. Rather than tackling exclusion, censorship, discrimination and repression, they entrenched these injustices

and, in so doing, deepened and perpetuated conflict.

Previous efforts by the Irish and British governments – from Sunningdale in December 1973 through to the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985 and the Downing Street Declaration in 1993 – were about defending and protecting the status quo. They were about stabilising and pacifying rather than about removing the injustice that was driving political dissent and resistance.The policies of both governments sought to criminalise and marginalise Irish republicans.

The British state’s counter insurgency strategy also relied heavily on state sponsored collusion with unionist death squads. None of this worked.

On the contrary, it made the task of peace building more difficult. It led to an entrenchment of conflict.

Peace building requires a different approach. Peace is not simply about ending conflict. It has to tackle the causes of conflict. Peace must therefore mean justice. The work of the late Fr. Des Wilson and Fr. Alec Reid was central to this endeavour.

Sinn Féin also came to understand the importance of the international dimension. We began to explore that area of work – most successfully in the USA and South Africa. At that time, the British government was resisting any scrutiny of what was happening in the North. It insisted that these issues were an internal matter “for the government of the UK.”

The Irish government had no consistent strategy to contest this. As Sinn Féin increased our electoral mandate, rather than addressing the core issues that were driving conflict, policies were developed to subvert and set aside the rights of republican voters. This was, of course, entirely counter-productive.

A key part of our focus therefore was about turning the governments away from their disastrous, undemocratic and deeply flawed policy of refusing to talk to Sinn Féin. Sinn Féin argued in Scenario for Peace in 1987; in our talks with the SDLP in 1988, in Towards a Lasting Peace in Ireland in 1992 and in my joint statements with John Hume and in the Hume-Adams Agreement that inclusive dialogue was essential for building peace.

John Hume was pilloried and vilified and condemned by governments and most of the political parties and by large sections of the media, for daring to talk to me. Thankfully John refused to succumb to that pressure. Imagine where we would all be today if they had had their way.

Sinn Féin had also begun the slow process of talking to others, occasionally publicly but often privately, secretly. This was especially the case when dealing with the British and Irish governments.

The dialogue between John Hume and myself was probably the clearest example of this developing alternative strategy. It certainly generated enormous public attention, most of it negative, as the establishment in Britain and Ireland pushed back against any new approach. But others were starting to listen and talk to Sinn Féin and to acknowledge the rights of our electorate.

Taoisigh Charles Haughey, Albert Reynolds and then Bertie Ahern authorised and then facilitated a dialogue with the Sinn Féin leadership. Bill Clinton listened to Irish American voices and broke

with the pro-British agenda that had been followed by successive US administrations. And the British Prime Minister Tony Blair also recognised the need to talk and to listen. These key leadership figures were critical to ending the failed approaches of the past and in developing a new approach based on dialogue and on inclusion. The process also involved republicans taking significant initiatives and risks to create momentum in the process or to end crises.

All of this took many years of hard work, too many years but in the end, collectively, we succeeded in building a conflict resolution process that, for all of its imperfection, has become a model for peace building. The negotiations which commenced in September 1997 and led to the Good Friday Agreement were based on this new and different approach grounded in inclusion, equality and democracy.

As Jonathan Powell remarked in his contribution to the Committee in June 2022 the “crucial point about the Good Friday negotiations was making them inclusive.” That is the key to its success. The Sinn Féin leadership went into the negotiations knowing we would not achieve all of our objectives given our political strength at that time. However, we had our own red line issues. For example; we had already decided to compromise on the need for a single unity referendum by holding two referendums North and South on the same day. Our leadership decided that the policing and justice issues should be dealt with in a separate negotiation – the RUC had to go. In our view a Commission could best deal with this issue. One of our key objectives was to get rid of the Government of Ireland Act. I am pleased that we succeeded.

The issue of equality had to be imbedded in the agreement; as a result measures were put in place to achieve this and the Agreement correctly refers to equality 21 times in sharp contrast to the Sunningdale Agreement where it is not mentioned at all. Then crucially, there is the issue of consent. Previously this was interpreted as referring specifically to the consent of the unionist majority defined in Article 4 of the Sunningdale Agreement as “represented by the Unionist and Alliance delegations.” The Good Friday Agreement is clear. Constitutional change requires the consent of a majority. This is the democratic position. Of course, the sensible goal for all democrats must be to persuade the largest number of people to vote YES. That is obvious and common sense. Finally, it is important to understand that the Good Friday Agreement is not a settlement. It never was. It doesn’t pretend to be. It is an agreement to a journey without agreement on the destination. The promise of the Agreement is for a new society in which all citizens are respected; where the failed policies of the past are addressed; and where justice, equality and democracy are the guiding principles.

It also provides for the first time a peaceful democratic pathway to achieving Irish independence and unity. This was crucial and central to the decade’s long effort to provide an alternative to armed struggle as a means to advance these legitimate goals.

From a Sinn Féin perspective, the efforts to reach that position involved prolonged engagements with John Hume, back channel communications with successive British governments, with Fianna Fáil led administrations, ongoing outreach to Irish America, and subsequently the White House, as well as attempts to outreach to elements of unionist and loyalist opinion.

No Irish government has ever produced a strategy to build a new and inclusive Ireland and give effect to Irish unity. Now there is a mechanism to achieve this. The absence of Irish government planning is indefensible and incredibly short-sighted. There is no excuse for this.

What is needed is the full implementation of the Good Friday Agreement, including setting a date and planning for the referendum on the future.

This requires inclusive discussions about the future to ensure that not only do citizens take informed decisions but that the new Ireland which emerges when the Union ends is one in which everyone is valued and social and economic rights are upheld. The Irish government should establish a Citizen’s Assembly or series of such Assemblies to discuss the process of constitutional change and the measures needed to build an all-Ireland economy, a truly national health service and education system and much more. This makes sense.

Very few countries get a chance to begin anew. Ireland, North and South, has that chance. Most leaders would embrace this, welcome it and be excited by that prospect. Most leaders with a vision for the future would carefully and diligently seize this opportunity. But not in the South. Political parties which have enjoyed being in power in the Irish state since partition don’t wish to give up that power.

That’s why the government refuses to establish a Citizen’s Assembly to plan the future -an inclusive, citizens centred, rights based society of equals.

It is certainly Sinn Féin’s desire to encourage and help create such a new departure for all the people of our island. It’s all about democracy. The people should decide.

At a time when the debate on constitutional change is dominating much of our politics and

opinion polls are being produced regularly, it makes no sense not to plan – not to prepare for the unity referendums.

The Irish government has a responsibility to prepare for constitutional change. The government and the rest of us need to be totally committed to upholding and promoting the rights of our unionist neighbours – this includes the rights of the Orange Order and other loyal institutions.

The protections in the Good Friday Agreement are their protections also. This is their land, their home place. There needs to be a clear commitment by the rest of us to upholding their rights and to working with them to make this a better place for everyone.

As Martin McGuinness said:

“I am so confident in my Irishness that I have no desire to chip away at the Britishness of my neighbours.”

Surely the new Ireland planned and built by all of the people of the island can accommodate and celebrate our differences and diversity. Irish Unity will profoundly transform the political landscape. A new multicultural society, embracing and respecting all traditions will emerge. At the core of the progress we have already made is dialogue. Dialogue - talking and listening to each other - is the key to resolving conflict. Dialogue is key to building an inclusive society.

Yes, there will be many challenges but there will also be many opportunities. I look forward to the future with hope and optimism.

It was a Friday like no other. President Biden was speaking in Mayo and former President Clinton had just landed in Belfast to take part in a three day conference at Queen’s University marking 25 years of the Good Friday Agreement.

President Biden was accompanied by Secretary of State Blinken, Special Envoy Joe Kennedy, and leading members of Congress. President Clinton was traveling with former Secretary of State Hilary Clinton and they were both joined by George Mitchel at the Queen’s Univeristy event. It was an unprecedented demonstration of US support for the Good Friday Agreement, peace, and progress in Ireland.

The message was clear and consistent. The US remains a player in the politics of the Good Friday Agreement. They have skin in the game. The Institutions should be working, the agreements honoured and the governments operating in partnership.

This was the latest in a long line of presidential visits. Every sitting President since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement has visited Ireland. There are some commentators and British politicians who paint these visits as some kind of “paddywackery” or playing to an Irish American vote. These uninformed opinions are founded in racism, colonialism, and a cynical approach to politics that tells us more about the commentator than the issue. Tammany Hall is long gone and no American President is driven by naïve romanticism. Presidents’ Clinton and Bush had little connection to Ireland, but both acted to enable and protect the Good Friday Agreement.

Our peace process is viewed in Washington as the most successful foreign policy intervention of a generation. In protecting the Agreement, they are protecting United States interests in peace and progress in Ireland. While we differ on other aspects of US foreign policy, in Ireland their intervention has worked.

The British like to promote the “Special Relationship” with the US. A strange invention for a nation that prides itself on having no permanent allies or enemies only strategic alliances.

The term “Special Relationship” was coined by Winston Churchill in 1946 after the end of World War 2. It came to prominence in the subsequent cold war. The British were the closest US political and military allies in Europe. Throughout the 1960’s successive US administrations encouraged Britain to join the EU and for the EU to accept Britain.

The collapse of the Berlin Wall, the runification of Germany and the ending of the cold war changed the dynamic between Britain and the US. It was a time of great hope in terms of global politics. Peace processes were developing in Palestine, South Africa, and Ireland. This was mirrored in Irish America. For years the British had asserted that the North was an internal matter. Throughout the late eighties and early nineties, the discussion in Irish American circles was about the potential of peace and agreement in Ireland. Into this stepped Bill Clinton when he committed to issuing a visa to Gerry Adams and to appointing an envoy. The North of Ireland was no longer an internal matter for the British Government.

The British objected, but under the leadership of Bill Clinton, the issue had moved on. The potential for a peaceful resolution to what had been adjudged an intractable conflict was now embedded in US policy.

The road ahead would not be without its

twists and turns. But the US played a central role in reaching the Good Friday Agreement. Since then they have acted as guarantors. Our peace process was an international matter, our agreements became international agreements. Fast forward twenty years and Brexit brings a challenge to the Good Friday Agreement and a change in the relationships between the US, EU, and Britain.

In EU terms partition was an issue between two member states. Since Brexit partition is now an issue between the EU and an external country. Irish unity is the easiest option to safeguard the internal market, manage borders and safeguard EU interests

Britain was America’s key ally in the EU - that is no longer the case. The relationship between Washington and Brussels now out trumps that with London. While the military alliance with Britain, as part of the wider EU actions against the invasion of Ukraine is important, the long-term strategic alliance for the US is

with the EU and by dint of membership the Irish Government.

The US-Irish relationship runs deeper than strategic self-interest. It is forged in generations of immigration. It is in shared stories, personal histories, and cultural pride. The connection between Irish America and Ireland is unique. That plays out in arts, economy, and politics.

The Good Friday Agreement is supported by both parties in a highly divided Congress. The US wants to see the Irish Peace process prosper. Political leaders and foreign policy experts are looking at the coming twenty-five years. The trends are obvious.

The US as a guarantor of the agreement recognises the right of the people of the island of Ireland to determine our constitutional future. We share a common challenge to ensure progress is planned, peaceful, and democratic. It is for the people of Ireland, North and South to determine their future free from external impediments and threats. They are the rules and the US has a role in ensuring that they are followed.

Supporters of the Agreement have to deal with a British government that believes it is not bound by the rules and an Irish Government in denial about the future.

The 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement focused on past achievements and on current challenges. This was reinforced with the local government results which saw for the first time a greater number of pro United Ireland voters over pro-Union voters.

The message for the US since Brexit has been to protect progress, implement the agreements and work the institutions.

We are at a time of Global change and realignment. Once again Ireland can demonstrate that peaceful and democratic change can be managed. The US and International allies will continue to play a meaningful part in that process. We now need both the Irish and British Governments to live up to their obligations including planning and providing for Irish Unity referendums.

By Conor Heaney

By Conor Heaney

While the Irish Government continues to reject the sensible proposal that it should be preparing for constitutional change, and the holding of the unity referendums provided for by the Good Friday Agreement, local councils North and South have begun to increasingly fill that void.

The Irish government’s stance has come under increasing criticism. In recent weeks

Professor Brendan O’Leary, who is Lauder Professor of Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania, has added his voice. In an interview with the BBC he said: “It is incumbent upon the Irish Gov to start preparing for the possibility of unification … Even if it doesn’t happen it is the minimum courtesy owed to the population of the North.”

The local government election in the North, which saw pro-unity voters outnumber prounion voters for the first time since partition, has intensified this debate around constitutional change.

Prior to the May election local councils North and South had already taken initiatives to encourage the conversation on Unity. Irish Unity Working Groups have been established in Derry City and Strabane District Council, Mid Ulster, Fermanagh and Omagh, Newry Mourne and Down, and Donegal County Council.

In addition, Council motions calling for the establishment of a national Citizens’ Assembly to prepare for reunification have also been passed by all the above Councils plus Belfast, Dublin City Council and South Dublin Council, and by Cavan and Monaghan Councils.

In relation to Derry and Strabane Council the Irish Unity Working Group has put in place a phased Consultation with rate payers and stakeholders in the Council area asking for views and contribution on visions for a new united Ireland that opened in January 2023 and will run until 5th April. These responses will be collated in a report and the consultation will move into further phases including in-person meetings, guest speakers and sectoral aspects of reunification. The consultation can be found at www.derrystrabane.com/ constitutionalchange

Derry and Strabane Council have also established a library of materials on Irish unity on the Council website that ratepayers and others can access to help inform their contributions to the consultation. This work will likely be replicated in the Councils that have also established Irish Unity Working Groups during 2023, but the ultimate aim is for the Irish Government to start to plan and prepare properly through an AllIreland Citizens’ Assembly for the Irish Unity referendum to come.

Dear Mr Smith,

This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing. This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.

This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing. This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.

This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing. This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.This text is only intended to show that the recommended font for letters is Arial 10.5pt. You can choose your preferred line spacing.

Yours Sincerely,

In 1998 the Good Friday Agreement set out the context for referendums on Irish unity. The Agreement asserts that it is for the people of the island of Ireland alone to shape our future and to exercise our right of self-determination on the “basis of consent, freely and concurrently given, North and South.”

This democratic and peaceful mechanism to achieve Irish Unity is a game changer which was not available to previous generations. 25 years on from the Agreement Irish Unity is now within touching distance. There is growing interest in and support for Irish Unity. But reunification needs to be planned for. That means those of us who want Irish Unity, planning for its achievement. The Commission on the Future of Ireland was established by Sinn Féin in November 2021. Its remit is to undertake a grassroots consultation with the people of Ireland and internationally on the future of Ireland.

This will be achieved through the hosting of public People’s Assemblies; through the collection and collation of written contributions; through hosting sectoral meetings, and in private engagements. A final report will be compiled at the culmination of the project. So far, the Commission has hosted successful public events in Belfast, Derry, Donegal and the Armagh/ Down / Louth border region, with a series of others planned. A series of sectoral events are also being planned over the coming months which will include discussions with women, young people, trade unionists, gaeilgeoirí and those from an agricultural, rural and farming background.

The Belfast People’s Assembly was an informative and thought provoking event, which addressed a multitude of topics. It was clear from the wide range of speakers from diverse backgrounds, that there is a desire to engage with the Commission on the Future of Ireland and that this desire is not limited to those from a republican or nationalist background. The principle message from the meeting was that people want a better future and they believe that a future which is better than the present arrangement is possible and desirable. The issue of citizens’ rights formed a large part of the discussion– housing rights, language rights, migrant rights and the rights of disabled people were discussed.

The economy, low productivity in the North, class-based economic policies and developing all-island infrastructure as an aid to economic development formed the basis for other contributors.

Those who attended the event clearly believed that there is a need to begin planning for constitutional change and that this should be led by the Irish Government. Consequently,

the meeting voted overwhelmingly in favour of the Irish Government establishing a Citizens’ Assembly on The Future.

The Belfast meeting was addressed by Sinn Féin’s Party Chairperson Declan Kearney, Leas Uachtarán and First Minister Designate Michelle O’Neill, and the independent chair for the evening was Eilish Rooney of the University of Ulster.

Over 300 people packed into the Waterfront Studio where they discussed constitutional change and the steps needed to create the new Ireland.

The event saw 10 guest speakers make verbal contributions and this was followed by a discussion with the audience. The conference was divided into two sessions. The first covered ‘The Economy and Communities in the New Ireland’ and the second was titled ‘A New Ireland for Everyone’. What was clear from this event was that we must also address the concerns of those who have not yet made up their minds, and are unsure how they would vote in a unity referendum.

The Commission on the Future of Ireland is an important part of this process of dialogue.

Watch the Belfast People’s Assembly on Youtube:https:// www.youtube.com/

watch?v=B88dmep9SS4&t=3223s

Full report of Belfast People’s Assembly available here:

https://www.sinnfein.ie/files/2022/ A5_REPORTCommissionFutureIre. pdf

https://www.sinnfein.ie/files/2022/A5_ REPORTgaeilgeCommissionFutureIre_061222. pdf

the Belfast session in that it took the form of a panel discussion. The theme of the event was ‘Celebrating Diversity- Ending Divisions’. The event was chaired by Joe Martin, former teacher and principal who has worked with people across the cultural divide in Derry. He stated that “Our biggest natural resource is our people, particularly our young people” and that “Unity is not about uniformity, it embraces diversity.”

The panellists were former Sinn Féin MLA Maeve McLaughlin who is Project Manager of the Bloody Sunday Trust and a community activist; former minister of First Derry Presbyterian Church David Latimer; writer and former editor of The Impartial Reporter Denzil McDaniel, and Catherine Pollock an Irish langauge activist and rights campaigner. There were also contributions from the floor of the meeting.

The key themes of the Derry discussion were safeguarding rights and protecting Protestant Unionist Loyalist traditions in a new Ireland, the changing political attitudes and perspectives on a new Ireland, celebrating diversity and ending divisions and the role of a Citizens’ Assembly in the debate on a new Ireland.

Maeve McLaughlin referenced the ‘Derry Model’ – “Derry people have led the way –Derry people have principles, leadership, are able to take risks, and able to get things done.” She pointed to the Bloody Sunday apology and parading resolutions as specific examples of this.She also remarked that senior loyalists have told her that people who are not discussing a new Ireland have their “heads buried in the sand”.

The Rev. David Latimer opened his remarks in Gaeilge, advising he is “Iontach sásta le bheith ag caint le chéile – happy to be speaking together”. He believes that Unionists are currently having smaller, quieter, water cooler type discussions on a potential new Ireland but he believes it is important to increase engagement.

“Everyone should have their say and no one should be left behind” were the words of Sinn Féin National Chairperson Declan Kearney who opened the second Commission public event which was hosted in Derry City. Over a hundred people packed into the venue. The structure of the discussion differed from

Denzil McDaniel began his contribution by saying: “I very much identify as a Protestant/ Irish”. Denzil said “I think we need a big conversation about how we grab the change and move on. There isn’t enough conversation from Protestant and Unionists. I would worry for them because change is already happening.

‘Celebrating Diversity - Ending Divisions’

More change is happening and they need to be in that conversation and saying what part of the new Ireland they want to be part of.”

Catherine Pollock comes from a traditionally Protestant home with unionist parents. She identified as British initially but has also embraced her roots as Irish, with a strong connection to the Irish language. Catherine felt that a shared island is such a unique opportunity. It will be a challenge and stated the importance of getting the process right and listening to the alternative Protestant voice as the “Protestants in the curious middle ground may be decision makers”.

Declan Kearney MLA, the Chair of the party’s Commission on the Future of Ireland appealed to “our Protestant neighbours, and unionist people in our society” to engage in the conversation on constitutional change. He urged those from the Protestant/Unionist section of society “who may already be considering this process of change; or who may hold reservations about reunification; to identify the guarantees and protections which are important to you.”

Watch the Derry Commission event here: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=KYm5iMyyUKY&t=5s

Full report of Derry event available here:

https://www.sinnfein.ie/files/2023/ A5_DERRY_REPORTtogether1.pdf

“The need to create an island that is warm and welcoming for everyone, which protects public services, creates decent jobs and pay and establishes democratic arrangements and structures which leave no-one behind”. This was how Donegal Sinn Féin TD Pearse Doherty set the context for the third public meeting of the Commission on the Future of Ireland – the Donegal People’s Assembly held in Ballybofey on 13th February.

The independent chairperson was Micheál Ó hÉanaigh, former head of Údaras na Gaeltachta. He framed the meeting saying that “the people here are on the coalface living this day to day.” The panellists on the night were Professor Terri Scott, recently retired Pro Vice-Chancellor at Ulster University; Noelle Duddy, a former chair of Donegal Action for Cancer Care (DACC) and spokesperson for Co-operating for Cancer Care North West, CCC(NW); Paul Hannigan, Head of College at Atlantic Technology University Donegal. Paul is a member of the Donegal Local Community Development Committee (LCDC) and the North West Regional Executive of IBEC; Toni Forrester, Chief Executive of Letterkenny Chamber of Commerce, and Seamus Neely, former Chief Executive of Donegal County Council.

The key themes of the Donegal People’s Assembly were the infrastructural deficit in the North West, linked educational policies beingkey to the future of the region, the challenges in engaging political unionism on the future of Ireland and the idea of community in all its forms in the new Ireland.

Seamus Neely spoke of the limitations that currently exist as a result of Donegal being partitioned from its natural hinterland. Examples include the lack of joined up thinking regarding planning and infrastructure.

Toni Forrester highlighted how businesses in the

North West try to not see a border and attempt to create avenues to work together. She outlined some examples of businesses working together successfully while admitting that partition has caused limitations. “We don’t see the border in our head, but we do have to deal with it”.

Paul Hannigan stressed how education is key to the future of the region and desired a sustainable education model. He also explained how Brexit has brought the political focus back on the North and how he hopes we can take advantage of this.

Noelle Duddy highlighted the fact that, due to partition, Letterkenny hospital does not have a critical mass to have a radiotherapy unit. Donegal patients are still travelling to Galway and Dublin which is not good enough. Many in the audience got involved the discussion, many of whom spoke in Irish. The audience highlighted the significant disadvantages faced by the people of Donegal including the ongoing cost of living crisis; marginalisation and economic disadvantage; failures to invest in critical infrastructure such as roads, public transport and broadband;

emigration due to lack of jobs, opportunities and housing; underinvestment in healthcare services and the defective concrete scandal affecting hundreds of households across the county.

Pearse Doherty TD said “Partition cuts Donegal off from our natural hinterland of the North West. Partition and unequal development across the 26 Counties has led to marginalisation, isolation, low employment and poverty.”

Watch the Donegal People’s Assembly here:

https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=OUmR_pPnVt8&t=438s

The most recent People’s Assembly took place at the end of March. Over 300 people packed into the Carrickdale Hotel to attend the Armagh Down Louth People’s Assembly. The huge attendance at that event demonstrates the level of interest in planning for a new and united Ireland.

This People’s Assembly was an opportunity for citizens from the border region to have their say on the future of Ireland.

The ill-effects of living under British rule are keenly felt in this area and the implications of Brexit casts a long shadow.

This People’s Assembly was chaired by Dr Conor Patterson of Newry and Mourne Enterprise Agency. The panel included; Reverend Karen Sethuraman; ICTU Assistant General Secretary Gerry Murphy; Mairéad McAlinden former CEO of the Southern Health & Social Care Trust and Aidan Browne of Dundalk’s DKiT’s Regional Development Centre.

In addition to an excellent and varied panel, the contributions from the audience were thoughtful, spirited, informed and very interesting.

It was standing room only and the packed gathering heard Uachtarán Shinn Féin Mary Lou McDonald open the event. In a wide ranging address Mary Lou spelt out the difficulties caused by partition and the opportunities which will be created by ending division.

Mary Lou also extended the hand of friendship

to Protestants and unionists when she said: “To those from the unionist culture I extend a sincere welcome – the new Ireland must be a warm house for all and your traditions and beliefs must be respected and cherished. I invite you especially to be part of the conversation and for us all to plan for the future together.”

Mary Lou urged the Irish government to facilitate and support our changing country by establishing a Citizens’ Assembly on Irish unity. She said: “This is an exciting time for us all; filled with opportunity and hope for a better future. That’s why we need to get it right. Our new constitutional national democracy will emerge from a phased transition and that is why planning and preparation should begin now. Grassroots communities should be involved at the beginning of that process, not at the end.” Speaking directly about the challenges facing the border region Mary Lou said: “Our shared challenge is to create a future which is warm and welcoming for everyone and where the

potential prosperity of areas like this border region can be fully unlocked.”

Footage of Mary Lou McDonalds main address to the Armagh Dow Louth People’s Assembly available here:https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=HP2OWkwK0_U&t=131s

Over the past few weeks and months the focus has been on the anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement.

The GFA provides a mechanism for selfdetermination through which Irish unity can be achieved peacefully and politically.

An agreed, united Ireland should be shaped by the people of Ireland alone without interference. That is an Ireland which guarantees and safeguards the rights of every citizen and section of society.

Sinn Féin does not own the Irish unity debate. We want it to be inclusive, flexible and genuine. Nor do we claim to have all the answers. That’s why structured dialogue is essential.

A genuine and open discussion should be taking place about the principles and reassurances required to underpin a new constitutional settlement on the island. The Commission on the Future of Ireland gives people an opportunity to have their say and tell us what their main hopes, aspirations or concerns for the future are.

The public debate around ending partition and achieving Irish unity is now mainstream and one of the most important discussions in our society at this time.

The focusfor the next 25 years should be upon opening a new phase of the peace process and a pathway towards a new future.

That’s why the Irish government should establish an all island Citizen’s Assembly without further delay.

The people should be sovereign. It is they who must self-determine our future on this island.

Everyone should have their say.

It is estimated that in the years since the Good Friday Agreement was achieved more than 600,000 people have been born. Add to this the number of young people who were alive then and a large proportion of today’s northern population has never had any direct experience of conflict. Unless their family was impacted most will have no memory of the militarised society that existed then.

25 years later Éire Nua asked four young people to comment on the Agreement.

Rugadh in 1998 mise. Bliain na síochána, bliain an chomhaontaithe. Bliain a d’athraigh achan rud, athraithe go hiomlán mar a dúbhairt Yeats tráth. Ní leor líon focal gan srian le cur cíos beacht a dhéanamh ar an bhliain stairiúil seo. A bhuí le laochra agus ceannródaithe, níor mhothaigh mise saighdiúirí gallda ar shráideanna mo chathrach. Níor mhothaigh mise nuacht tragóideach achan oíche agus níor chuir mise lá isteach riamh le buairt nach bhfeicfinn cara nó ball teaghlaigh liom le druidim an lae.

Bhí mise ar an Ghaeloideachas mar a tháinig mé i mbun mo mhéide, éacht nach féidir a dheighilt ar an chomhaontú agus na buntáistí a thug an tsíocháin. Tháinig borradh faoin Ghaeloideachas ar fud na sé chontae ó síníodh an comhaontú in 1998, feabhas ar na háiseanna, nó foirgnimh agus líon na bpáistí ar an Ghaeloideachas ag gabháil thar 7000 le blianta beaga anuas agus gan cuma ar chúrsaí go dtiocfaidh moill air seo. Dul chun cinn na síochána.

Chaith mise tréimhse ag obair le Féile an Phobail, an fhéile ealaíon is mó in Éirinn agus ar cheann de na mórfhéilte is mó san Eoraip. Achan tsamhraidh, tchí tú na sluaite ag teacht go hiarthar Bhéal Feirste ag na coirmeacha ceoil, na léachtaí agus na laethanta spraoi do theaghlaigh. Féile a tháinig ar an tsaol i seachtain dhorcha do mhuintir uile na hÉireann. Leoga, léiriú ar phobal éagsúil iarthar na cathrach atá ann. Dul chun cinn na síochána.

Tá aistear fada curtha isteach againn agus aistear fada eile le gabháil. Tá feabhas nach beag tagtha ar shaolta na ndaoine ar an oileán seo a bhuí le laochra 1998, ar chomhchéim dar liom le laochra 1916.

I wrote this as I sat in the chamber in Stormont at the British Irish Parliamentary Assembly which was meeting for a special gathering to mark 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement.

Truthfully, my memories of the Agreement itself is minimal to none although I do remember things which happened around that time which I now know, in hindsight, happened as a result of that Agreement.

My defining memory of that period is undoubtedly the release of prisoners and the impact that had on families. At that age your key understanding of families are the families of the children you play with. My sister and I always played with two sisters who were our age and friends of our family. Their father was in jail and, therefore, I never met him throughout all the years of playing in their home.

When he was released there was a big picture of him in the Andytown News with his daughters and I couldn’t believe it! It was only years later that I realised the impact it had on me, I regularly get asked in interviews what impacted on my politics, and looking back Séanna’s release from prison is without question one of them.

Of course, when preparing to write this, I was puzzled as to why I couldn’t remember the Good Friday Agreement so I asked my family…. They told me that I was in Legoland that week. That explained it! I clearly remember punting in Cambridge with my uncle, a BBQ in the rain and of course my favourite Legoland ride in great detail.

Clearly for my 8 year old self this was far more exciting but undoubtedly the GFA played a far more important role in my life.

If my Legoland trip did teach me one thing it was the concept of building blocks. We continue to build on the foundations of the Good Friday Agreement and the pathway for Irish Unity therein.

When the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, I wasn’t born.

However, as a young person, the 25th anniversary in April of the Good Friday Agreement offered a space in which to reflect on what change has taken place from a society which was once divided by conflict, to a more peaceful one which still has to seize the opportunities contained within the agreement.

The Good Friday Agreement transformed the island of Ireland for the better, creating a much more prosperous social and economic picture with peace at its core. However there is much more to be done. The mechanisms required for a poll on Irish reunification are contained within the agreement, enabling my generation to decide on our own future.

A quarter of a century after the signing of the agreement, it is imperative that we learn lessons from the recent Brexit referendum and properly plan and prepare for the referendum on Irish Unity which I believe is coming.

People must recognise that the Good Friday Agreement, regardless of each individual’s identity, helped us all, and so too could the reunification of this island. Identity, in my opinion, will not be challenged by constitutional change and as a society we must see past this as a barrier to further progress on this island.

I also feel strongly that we must use the 25th Anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement to educate my generation about the change it has brought about so far, the opportunities it offers for even more change in the future, and the importance of protecting it in all of its parts. Progress on peace and prosperity cannot stop now. 25 years on, the agreement is more important than ever.

Paul Boggs was elected to Derry City and Strabane District Council in May 2023

Síníodh Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta nuair a bhí mé cúig bliana d’aois. Cé nach bhfuil cuimhní agam air sin go direach, tá breac-chuimhne agam ar chúrsaí eile mar a bhí siad ag an am sin.

Bhí mo mhamaí ag obair ar An Chéide mar ghruagaire, cúpla céad slat ón bheairic póilíní sa bháile mhór agus cúpla míle ón teorainn idir Ard Mhacha agus Muineachán. Is maith is cuimhin liom na saighdiúirí bheith taobh amuigh ar na sráideanna agus, ag an am, níor thuig mé an fáth a raibh siad ann, ach bhí eagla orm rompu agus roimh na gunnaí a bhí leo mar sin féin. Bhíodh an siopa gruagaire féin lán craic agus comhrá, ach nuair a bhí na saighdiúirí ar na sráideanna, bhí teannas nach beag san aer a mhothaigh mé féin, fiú ag cúig bliana d’aois.

Ní raibh aon ealú uaidh fiú amuigh faoin tuath ag an teach baile. Tá cuimhe an-soiléir agam ar fhuaim na héileacaptar thart orm, agus mé féin agus mo dheirfiúr ag amharc ar cheann acu ag tuirlingt sa pháirc in aice linn, gan eolas nó gan tuiscint ar cad a bhí ar súil nó na impleachtaí a bhí leis.

Ar ndóigh, de réir mar a d’fhás mé aníos, d’fhoghlaim mé níos mó faoi na cúinsí a d’fhulaing mo mhuintir agus gach duine eile sa phobal; na heachtraí marfacha ar nós an ionsaí a rinneadh ar an Rock Bar in aice linn, an teannas agus eagla a bhíodh orthu gach eile lá roimh bhrúidiúlacht na saighdiúirí agus na péas, agus na deacrachtaí a bhí acu ag dul i mbun gnáthchúrsaí an tsaoil mar gheall ar na seicphointí, na sceimhlí buama agus mar sin de.

Mar sin, tá áthas orm gur athraigh é sin uilig, agus go raibh an t-ádh orm fás aníos in am Chomhaontú Aoine an Chéasta. Tá mé anbhuíoch do na ndaoine a tháinig le chéile lena chur i bhfeidhm. Sílim féin gur thug sé deis do na sé chontae athfhás agus athbhláthú mar áit níos sabháilte agus rathúla ná mar a bhí, áit a dtugann deiseanna níos fearr agus níos cothroime do dhaoine.

Ar ndóigh thug Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta deis dúinn athchairdeas a dhéanamh idir an dhá phobal. Go pearsanta, tá mé buíoch as an ardchaighdéan oideachais agus fostaíochta a fuair mé féin go dtí seo, agus as na rudaí a tharla i mo cheantar ó síníodh an Comhaontú. Mar shampla tá oideachas lánGhaeilge anois againn ar an Chéide, a bhuíochas le Foras na Gaeilge a bunaíodh mar gheall ar an chomhaontú. Tá an beairic ar an Chéide dúnta,

tá na saighdiúirí imithe agus tá an spás in úsáid ag gnó áitiúil a chuireann neart fostaíochta ar fáil. Tá roghanna eile ag daoine seachas an long bán anois.

Faoi láthair, spreagtha ag na daoine a chuaigh romham, tá mé i mo Chomhlaireoir Shinn Féin ar an Choisear 2019, an chéad uair riamh do Shinn Féin an suíochán a bhaint ann. Tá mé ag obair fosta le Michelle Gildernew, MP Fhear Manach agus Thír Eoghain Theas. Dhá áit stairiúla ina mbealaí féin agus beirt ban eile ag treabhadh gort na polaitíochta. Is doiciméad fíor-thábhachtach agus ábhartha é Comhaontú Aoine an Chéasta fós sa lá atá inniu ann. Leag sé an bhunchloch d’Éire Aontaithe a bhaint amach trí chomhthoil an thromlaigh. Níl aon amhras ach go gcaithfidh mé an tréimhse atá romham ag tógáil ar an dhúshraith sin a leagadh in 1998, agus Éire níos fearr agus níos cothroime a thógáil do chách in éineacht le mo chomrádaithe.

Bróna is a Councillor on Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Council

The campaign to get the Irish government to establish a Citizens’ Assembly or series of such assemblies on Irish Unity is a key component of Sinn Féin’s strategy towards national independence. Such citizens’ assemblies have been a feature of the political landscape in the South since 2011. The Irish government can establish a Citizens’ Assembly at any time by a simple Dáil resolution. In the last 12 years Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil have organised seven such forums.

In 2012 Enda Kenny’s Fine Gael led government set up the Constitutional Convention which led to the referendum on Marriage Equality and to the first Citizens’ Assembly. This Citizens’ Assembly which ran from 2016 to 2018 considered the issues of abortion reform, the aging population, parliamentary reform, the management of referenda and climate change. It led to the 2018 referendum on access to abortion services.

In 2019 the then Taoiseach Leo Varadkar established a Citizens’ Assembly on Gender Equality. The referendum which will take place in November this year will seek to amend the reference in Bunreacht to a woman’s place in the home.

In 2022 An Taoiseach Micheál Martin announced not one but two Citizens’ Assemblies. One was to examine the

establishment of an elected Mayor for Dublin. The Assembly published its report last January. It recommended the creation of a “powerful new Mayor with wide-ranging powers and responsibilities similar to other major international cities.” The report is currently being considered by the government.

The second Citizens’ Assembly established by Micheál Martin considered the critical issue of biodiversity. This report was published in April. It contains 159 recommendations, including 73 high-level recommendations and 86 sectoral specific actions and priorities. At its heart the report is calling on the government to take urgent and decisive action to address biodiversity loss and protect our natural environment for future generations.

In February of this year Leo Varadkar announced the latest Citizens’ Assembly which will deliberate on drug use. Its inaugural meeting took place in April and over the remainder of this year the Assembly of 100 citizens will be asked to consider legislative, policy and operational changes the State could make to reduce the harmful impact of illicit drugs on society.

The 2020 Programme for Government commits the FG/FF led government to establish a Citizens’ Assembly on Education. Given this apparent commitment to participatory democracy why is the Irish government so dogmatically opposed to a Citizens’ Assembly on Unity?

The establishment parties in Dublin on paper are committed to Irish Unity. However the reality is that none have a strategy to achieve it. Their consistent refrain when this issue is raised is that now is not the time for a Citizens’ Assembly or a government led conversation on this.

Both point to the Shared Island Unit as evidence of their support for unity and while it is doing some good work nonetheless the Shared Island Unit is a minimalist approach by government from the real work that needs to be done.

Instead it is being left to academia, groups like Ireland’s Future, local Councils, political commentators, economists and others to address the myriad of issues that Irish reunification will throw up.

The reality is that thus far every Citizens’ Assembly held by the State has significantly raised public awareness of the issue under consideration. At this time the British and Irish governments are against constitutional change and against the referendums. So, are the unionist parties. There are many different reasons for this. For example, the British government is a unionist government.

For its part Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil are worried about a national re-alignment of politics in which the establishment parties will lose their dominance.

The political establishment in the South has done very well out of partition –Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have replaced each other as the government for decades.

So, how do we encourage the government to establish the Citizens’ Assembly and set a date for the referendum on Unity?

It must be the campaign issue at the heart of republican activism.

The electoral growth of Sinn Féin, the effectiveness of our burgeoning team of representatives across the island and the obvious support we are enjoying among the public, places enormous political pressure on the Irish government. Our task is to use that leverage efficiently. Do that and we can secure the Citizens’ Assembly that is necessary for the advance planning for Irish Unity.

For more information on the Citizens’ Assembly, how it could be arranged, what it might discuss and what could come in its wake, please see Sinn Féin’s discussion document. Our Future, Let’s Plan for it...Why the Irish Government must establish a Citizens’ Assembly on Irish Unity.

https://www.sinnfein.ie/files/2022/

While the present and previous Dublin governments have decided that it is not the time for a discussion on the issues surrounding Irish reunification, it is clear that this is not the feeling among many, including a wide range of academics both on the island of Ireland and internationally.

Brexit and the implications for Ireland, North and South, has triggered a myriad of research - too many to dissect - that are looking at the implications of Brexit and the constitutional issues that it raises going forward for the island of Ireland. There are many academics and institutions now looking at the many issues in respect of the constitutional question. These include the preparation, planning and strategies needed to advance the unity referendums. They are also examining the economic, social and environmental impact of partition and the potential scope and benefits of collaboration North and South.

Professor Colin Harvey, who was the target of intense abuse and threats because of his pro-unity stand, has chosen to look specifically at the legal and human rights issues around Irish Unity. His latest paper entitled ‘Making the case for Irish Unity in the EU’ was co authored by Mark Bassett, a barrister and lecturer, also from Queens University Belfast. It was commissioned by ‘The Left in the European Parliament’.

The paper looks at the necessary preparatory work for reunification within European and International Law as well as the merits of reunification from the perspective of the EU. Professor Harvey also published a paper in 2019 entitled ‘The Future of our Shared Island: A paper on the logistical and legal questions surrounding Referendums on Irish Unity’ in which he looked at the issues before and in the run up to a referendum.

One of the most important projects running at present is ARINS - ‘Analysing and Researching Ireland North and South.’ ARINS is a significant programme of research being undertaken jointly by the Royal Irish Academy and the University of Notre Dame in the US which also has contributing academics from a range of universities in Ireland. In its overview ARINS points to the constitutional flux in the aftermath of Brexit but also the need to understand and assess the functioning of the Good Friday Agreement and how it might be improved and developed. With this in mind ARINS intends to map interdependencies and connections between the North and

South and with Britain. ARINS also references the possibility of a referendum on the constitutional position of the North and that the absence of prior research and informed debate on the options and their consequences would be disastrous.

With this in mind their research and analysis focuses on three broad areas: political, constitutional and legal questions; economic, fiscal, social and environmental questions; and lastly cultural and educational questions. ARINS says that it does not seek to support any one position but to create the conditions for a better quality of debate and decision making.

A number of papers have already been published that focus specifically on constitutional issues around a referendum. Professor Brendan O Leary from the University of Pennsylvania has conducted comprehensive research regarding the need to prepare for a referendum on reunification called: ‘Getting Ready: The Need to Prepare for a Referendum on Reunification’.

This paper looks at models of a new Ireland that could be offered. He states that people are more likely to vote in favour of change if they understand what it is they are voting for. He also lays out the process needed if this approach is not followed. Either way he argues very clearly for a well thought out strategic approach in advance of a referendum. Rory Montgomery, former diplomat and Steering Committee member for ARINS echoes this point in his article ‘The Good Friday Agreement and A United Ireland’.

Professor O Leary’s analysis is continued further in a joint piece of work between himself and Professor John Garry of QUB in collaboration with the Irish Times. The project consisted of two major opinion polls conducted North and South as well as a number of focus group discussions. The project’s aim was to gather independent and unbiased information regarding public opinion on the constitutional future of the island; what influences their views; how their views might change; and what are the issues that could change their mind.

Other contributors to ARINS include Professor Jennifer Todd from UCD. Her paper ‘Unionism, Identity and Irish Unity: Paradigms, Problems and Paradoxes’ looks at Unionist perspectives regarding a United Ireland; where their issues lie; and looks at what forms of Irish Unity might be acceptable.

Professor Todd has also co-authored another paper with Joanne Mc Avoy of the University of Aberdeen and Dawn Walsh UCD entitled, ‘Participatory Constitutionalism and the Agenda for Change: Socio-economic issues in Irish Constitutional Debates’. This paper investigates how the participation of grassroots communities can shape the constitutional agenda, widening debate beyond institutional models to include everyday issues of importance to citizens.

Their paper found that there was a very strong interest in ‘bread and butter’ socio-economic and rights issues, and a surprisingly low concern with issues of institutional form, e.g. an integrated or devolved united Ireland. This was the case across the North among Protestant, Catholic and those deemed ‘others’ and this was the same in the South.

Professor Rory Montgomery also hosts a podcast series of interviews with ARINS authors about their work. It can be found at; https://open.spotify.com/show/08pJYRfzjn4XKKUqRql1IA

In terms of Human Rights research, Brice Dickson, Emeritus Professor of International and Comparative Law, QUB looks at the human rights aspect of reunification in his paper ‘Implications for the protection of Human Rights in a United Ireland.’ He concludes that there will be no impact on anyone’s human rights including those of citizens from the Protestant/Unionist community in the North in a United Ireland.

There is also a serious body of research that has been completed by a number of organisations who have been commissioned by the Shared Island Unit in the Department of An Taoiseach.

The Shared Island Initiative was launched in 2020 by the then Taoiseach Micheál Martin. The Shared Island initiative states: “... it aims to harness the full potential of the Good Friday Agreement

to enhance cooperation, connection and mutual understanding on the island and engage with all communities and traditions to build consensus around a shared future. It also goes on to say that it wants to foster constructive and inclusive dialogue and a comprehensive programme of research to support the building of consensus around a shared future on the island.”

In light of their commitment to research, they launched the North South Research Programme which aims to support collaborative research, innovation and development between individuals, research teams (in and between disciplines) as well as between higher education institutions –which will be of economic and social benefit to the island of Ireland. The first call for funding was in 2021. It awarded sixty-two collaborative research projects between academics and institutions, North and South.

Many of the projects encourage collaboration by academics North and South on a range of different issues, such as medicine and agriculture. Others are projects that specifically address particular issues on a whole island basis or the development of an all island approach to specific areas.

There are projects such as CARTLANN by the University of Ulster and University of Galway that will use the archival records of Conradh na Gaeilge to track the uneven development of Irish language policy on both sides of the border.

CEAB is a piece of research being conducted by the University of Cork and the University of Ulster which aims to ensure that women are included in political conversations of changing relationships on the island of Ireland.

COSHARE aims to provide an all island strategy to surveying staff about perspectives on consent and sexual violence and harassment.

HIGH-GREEN, being developed by Queen’s and the University of Cork is seeking to develop a miniature sensor which will map green house gas emissions in the context of all Ireland emissions monitoring.

In its role of providing advice on strategic policy issues to the government and An Taoiseach, relating to economic, social and environmental developments, NESC (The National Economic and Social Council) has been undertaking a programme of research to produce a comprehensive report on the Shared Island Initiative to inform its development as a whole of government priority.

After a number of impressive scoping and secretariat papers based on economic, social, environmental and connectivity studies North and South, NESC produced a comprehensive Report ‘Shared Island: Shared Opportunity’ in April 2022. The report made no fewer than 27 recommendations in 5 broad areas covering socio-economic and climate-sustainability issues.

The ERSI (Economic and Social Research Institute) is also working in partnership with the Shared Island unit. They have produced six reports to date based on economic issues such as cross border trade, high value FDI and productivity levels. They have also analysed the primary care and education systems North and South and the benefit of an all-island approach to the co-ordination of the energy infrastructure and renewable energy supports.

The Irish Research Council in partnership with the Shared Island unit has also launched a research scheme aimed at academia called the ‘New Foundations Programme’. Eleven awards have been made so far with research currently underway.

The University of Limerick is researching an all island network to combat hate crime while Trinity and the University of Dublin are conducting a North-South Legal Mapping project. A number of universities and studies are involved in projects that aim to foster dialogue, including highlighting the psychological processes that contribute to intergroup conflict and provide means to foster cooperation. Another study by UCD is looking at strengthening collaboration in cancer research across the island.

In conclusion, the breadth and depth of academic research and analysis around the issues

pertinent to and in preparation for Irish reunification is substantial and ongoing.

Added to this there is a level of academic collaboration on issues North and South that can only be beneficial and informative with regard to moving forward.

An understanding of all of this research is no easy task. The reports and papers are not easy to navigate. This in turn leads to the conclusion that if this research and analysis is to be accessible and helpful to citizens then there also needs to be a collaborative approach by academia, across all disciplines and institutions, to ensure that the papers and reports do not sit gathering dust on shelves.