14 minute read

Digital manufacturing for Murano glass

OMRI REVESZA

The project Isole aims to explore new application possibilities of Murrine, through the integration of digital technologies along its production process. Traditionally Murrine are being used for creating small decorative objects such as plates and jewels. The dimensions of those objects are limited due to a long and complex manual process, causing a narrow range of product applications and artistic expression. These technical limitations are reducing the commercial possibilities of the industry and appear unattractive to the younger generation of entrepreneurs and designers. Through an experimental process of using Murrine glass canes on their long side, Isole suggests an innovative production technique that allows to significantly increase the dimensions of murrine products and the velocity of their manufacturing, while revealing surprising artistic expressions of traditional craft, digital craft, colours and transparency. A sustainable future for Murano glass means a shift from a segregated introverted mindset to an extroverted one. Digital and manual don’t necessarily have to be contradictions, but rather complementary.

A Department of Design, Università Iuav di Venezia and Omri Revesz Design Studio, Venice, Italy.

KEYWORDS: MURANO GLASS, DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES, INNOVATION

Introduction

Murrine glass has very ancient origins, the first works date back to 3,0002,000 BC by Syrian, Egyptian and Roman glassmakers. During the Middle Ages, the murrine glass technique was lost but was taken up again later towards the end of the XIX century by Vincenzo Moretti.

The process of crafting a murrina object is long and complex. It requires manually slicing murrine canes into small pieces of about 5 millimetres, to be then arranged in a compact pattern on a ceramic plate and then heated in a furnace until they fuse into a single and further formed over a mould to the desired shape (History of Murrine, Murano Design Venezia). The decorative character of the artefact is determined by the colours and sectional drawing of the canes, and by the order in which the slices are placed one next to the other.

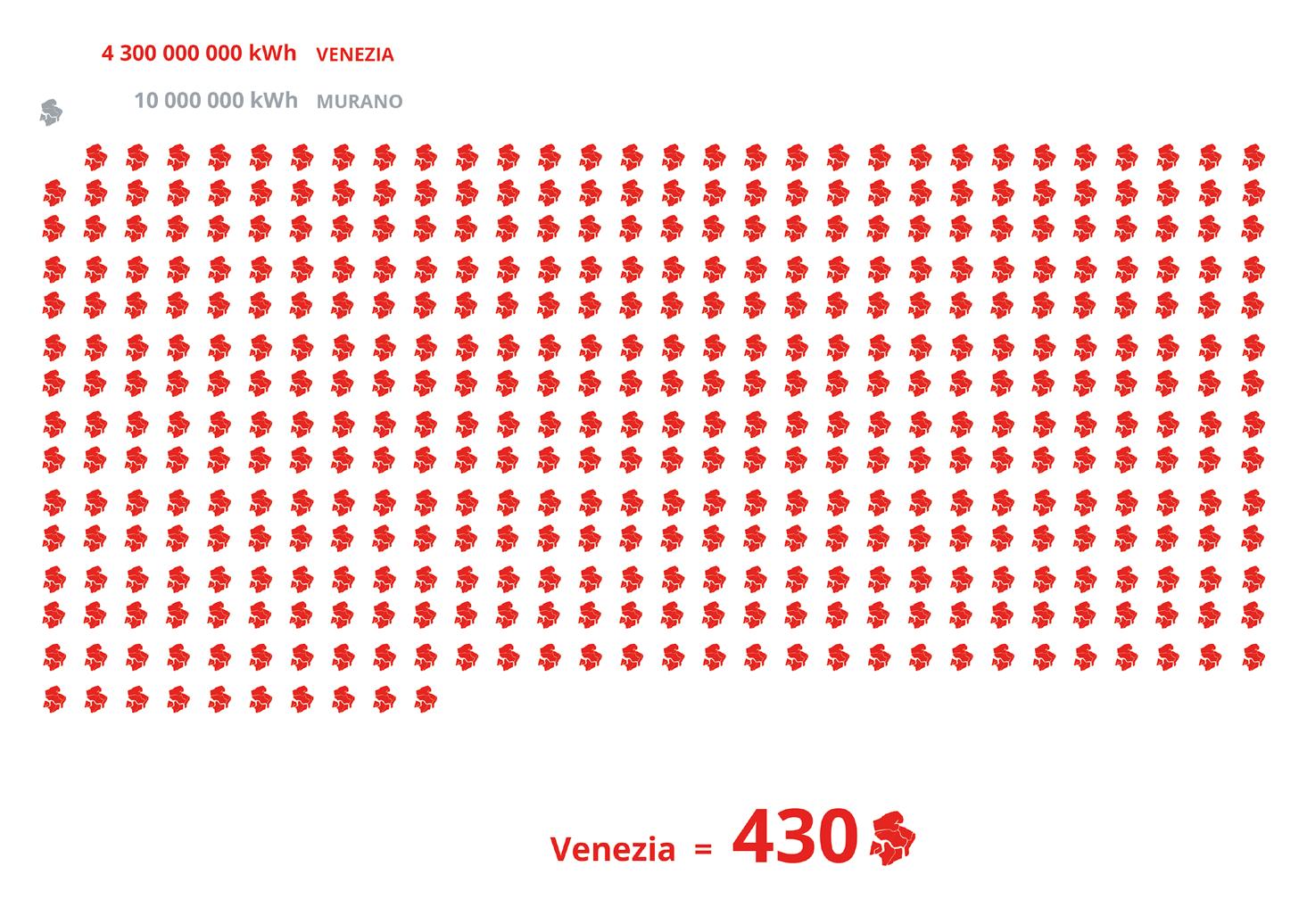

Given the complexity of the process, the dimensions of the artefacts are limited to small-scale objects, which in turn reduces the product application possibilities. Nonetheless, the colourful detailed patterns of murrine objects, the expressive language, and thus the emotional value of the artefacts are limited to those patterns of the given canes. These technical limitations are reducing the commercial possibilities of the murrine industry on one hand, and on the other appear unattractive to the young generation of entrepreneurs and designers to join in the industry and evolve it into contemporary forms of markets (Figure 01).

“Since the beginning of the economic crisis in 2008 until 2015, almost 94,400 craft workshops have closed, which amounts to a 7.26 % rate of decrease. In order to face these challenges, craft entrepreneurs must be innovative and review the ways in which they provide value to customers” (Bonfanti et al., 2018, p. 17). In recent times, industries of artisan craft are facing a similar problem, that can usually be analysed through three channels: manual work that doesn’t fit the spirit of the time, long production times that cause high costs, higher costs of the end product resulting in narrow target markets. Often the stakeholders of those industries are torn between the emotional attachment to the tradition of the practical well-established practices and the desire to innovate and bring their industry to the front of contemporary use.

Part of the frame Glass-Matters, the project Isole is an initiative of the FabLab of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, and involved a collaborative exploration process between the FabLab institute, the company Ercole Moretti, pioneers and leaders of murrine production, Lunardelli Venezia experts of wood crafting and design studio Omri Revesz. Aiming for an economical and socially sustainable future for the glass industry of Murano, the project was centred around the question of how might digital manufacturing technologies can be integrated along the production process, to create innovative product applications, without losing its well-appreciated historical DNA?

Murano glass DNA can be often defined as a dialogue between materiality

Fig. 01 Sectional slices of murrine arranged on a ceramic mould before being fused to a plate shape. E. Moretti

and craftsmanship, represented through colours and transparency. The project Isole uses Murrine glass canes in their long side allowing to significantly increase the dimensions of glass surfaces and the velocity of its creation.

Murrine are not seen anymore as an extrusion of materials but as layers. A further carving into the glass surface reveals a surprising symphony of traditional craft, digital craft, colours and transparency.

Objectives

Two spheres are setting the goals for the project: Inspirational, providing a ground for a new line of thought for Ercole Moretti and the Murano glass industry, and practical, developing openings for innovative processes and product applications. Whilst the inspirational sphere is harder to measure, the measures of success of the practical sphere were set around the following factors: • structural characteristics of larger scale surfaces; • cost efficiency of the process; • expressive design language.

The dimensions of the glass surfaces were defined as a key factor to reach new product typologies, the efficiency of the process is referring to reducing the times of manufacturing and the amount of manual repetitive work, and the expressive design language refers to the freedom applied by considering the layered glass surface as a blank terrain from which to extract hidden content rather than a predefined pattern to assemble.

Methods

With goals centred around structural characteristics, material DNA and design languages, and through a constant dialogue between design, glass experts and digital manufacturing experts, a series of empirical experiments were set to isolate each of the factors that could affect the accomplishment of the goals.

Structural factors: Murrine canes in their source form are provided in different diameters, and once fused together are creating thicker or thinner glass surfaces. Further, the size of the mould affects the thickness as the melted glass spreads wider and thinner in the relatively larger mould. The experiments held in order to test the structural resistance of each murrine diameter were set through predefined 10x10 centimetres ceramic moulds, fusing in them 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 millimetres diameter of canes (Figure 02). The experiment showed that during their fusing process and spread along a surface, rather than along a circular section, the canes would lose up to 30 per cent of their sectional dimension. 6, 7 millimetres of murrine resulted as the minimum viable dimensions for the formation of a one square metre surface. An 8-millimetre diameter of canes allowed a bigger surface of two square metres. The dimensions for the Isole project were limited solely according to the dimension of Ercole Moretti’s Fornace, measuring 180x120 centimetres.

Static factors related to the volumetric geometry of the end product were tested through the boundaries of curvature of the glass surface. The experiment included a series of moulds with different angles and inclination, and glass surfaces fused on them in a furnace of 800 degrees for 8 hours, to test if the surfaces can remain in the shape of the mould, or if it accumulates by gravity at the bottom of it. Results showed the possibility to incline the surfaces 15 degrees between plans and still obtain full control of the outcome surfaces.

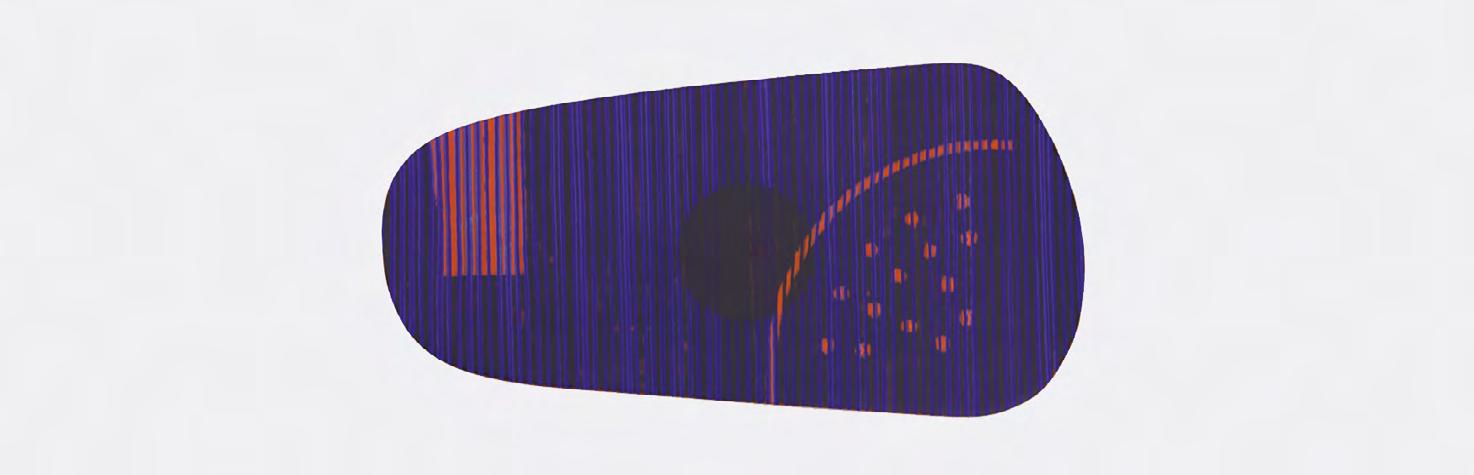

Material DNA: Colours and transparency are the most crucial characteristics of murrine to study and control within the process of Murano glass innovation. In a sectional view of the murrine canes, concentric circles of different colours and opacity are arranged to create the drawing stamp of a specific murrine. At the same time, according to the concept of working on the long side of the canes, those circles can be seen as layers of colour and transparency. Once fused to a surface, the canes deform from their original circular section to a quasi-square section, with layers arranged from the centre toward up, down and sides. The external layer of glass defines the first visible colour of the surface, while when carving on the surface further layers of colour and transparency are revealed out of the surface.

The control of this characteristic, which will later define the expressive language of the surface, was measured across factors of: • depth, in order to reveal inner layers of coloured glass, external layers can be removed by carving in the glass surface. The deeper the carve goes the more layers are being revealed;

• direction, the carving can be made along the direction of the canes revealing a continuous line of colours, or perpendicularly to the direction of the canes revealing a dashed line of colours, diagonal and circular carves reveal diverse patterns of continuous and dashed lines; • opacity, light effects can be controlled by using canes made of inner transparent layers, or outer ones. Inner ones create a three-dimensional depth effect, while outer layers will be almost entirely transparent as the outer layer once fused remains continuous throughout the entire thickness of the glass surface (Figure 03).

Expressive language: The artistic expression or design language is measured by the amount of graphics freedom associated with any Isole glass surface. To test the limits of graphic freedom, the experiments consisted of the study of different techniques of material removal. The first experiments included the configuration of specific 10x10 centimetres moulds, made by laser cutters, 3D printers and CNC milling of refractory materials. The moulds were flat at the bottom, but with nukes of different shapes and depths in them. Canes were placed in the moulds, and once fused in the furnace took the shape of the bottom and nukes. Subsequently, the moulded nuke shape was removed by using a circular sanding disc, to flatten back the surface and expose the inner layers of colours. This technique provided complete freedom of graphic expression, but at the same time demanded a complex post-process with the circular disc, when working on a larger scale of a glass surface. The second technique and most successful was tested through

Fig. 02 5-7 murrine canes placed in 10x10 centimetres sample moulds before fusion. Studio Omri Revesz Fig. 03 Sample moulds milled through a CNC machine to test depth, direction and transparency of murrine layering. Studio Omri Revesz

a process of laser cutting a mask of the desired graphics from a polymer sheet, placing it on the glass surface and sandblasting the exposed parts of the mask. The longer the sandblaster stayed on one spot, the more material was removed and therefore, deeper layers of materials were revealed.

By defining the structural and dimensional limitations of the glass surface, achieving control of the material DNA in terms of colour and light, and developing a semi-digital process that allows complete freedom in terms of expressive language, the ground was set for the developing a new range of product applications.

Results

Within the practical sphere, the experiments resulted in a 20 fold larger surface than previously obtained by Ercole Moretti, made in a significantly reduced time. Through this structural advantage, new diverse product applications are possible. The sandblasting decoration technique allows a complete freedom and aesthetic control over the design language applied to each surface. On the inspirational level, a new range of products designed by Omri Revesz Design Studio got internationally acclaimed at Milan Design Week, part of the exhibition Reflected/Reflections at Teatro Franco Parenti and at Venice Glass Week.

The design concept for the product range Isole follows the very essence of the production process that was developed during the experimental phase: reveal. Isole is a collection of tables made of a solid Mahogany base and a murrine table top, inspired by the relation between the islands of the Venetian lagoon and the natural phenomena of a constant water tide that covers and reveals them every day.

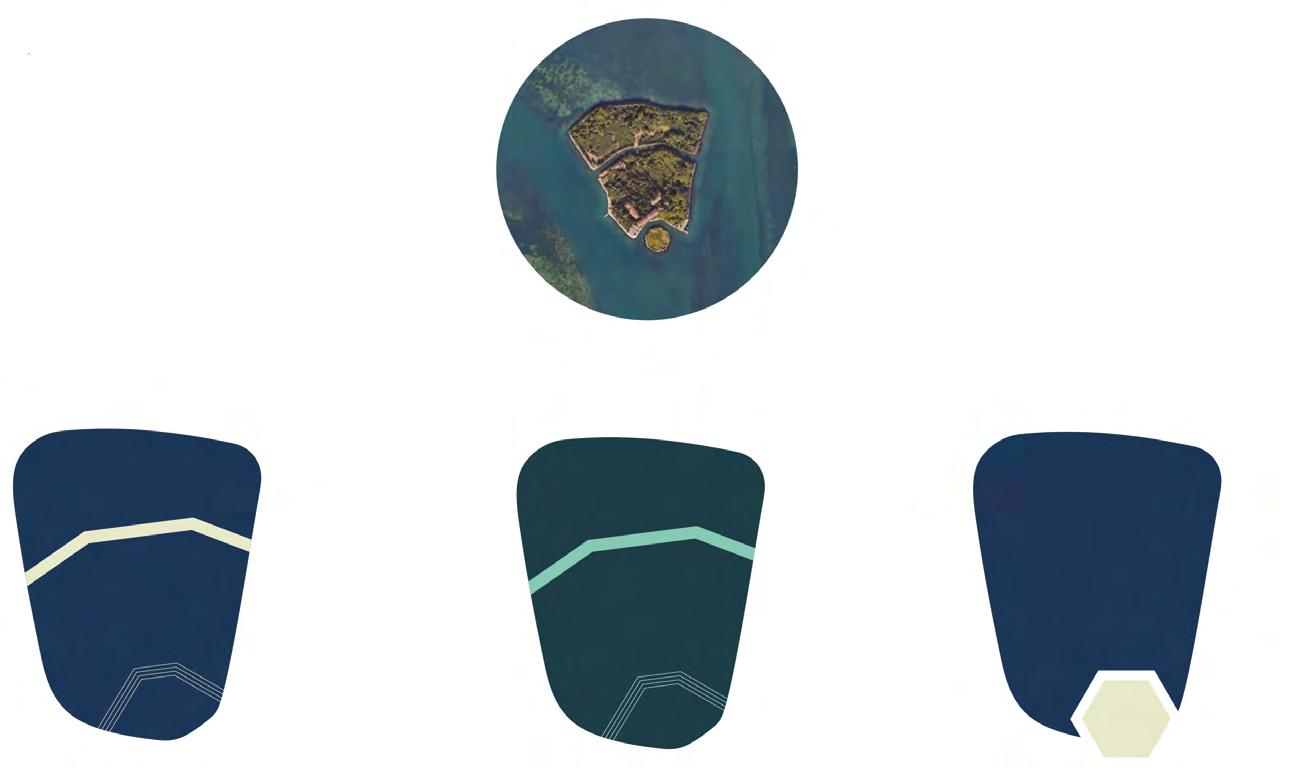

Venice’s lagoon is studded with 123 islands, whether hidden or tentatively exposed beyond the water’s unassuming surface. Every island tells the story of an ancient treasure buried beneath the sands of time, or of contemporary productive reality. Within the design process, the islands of the lagoon were mapped according to their natural environments, agriculture, architecture and human activity. A schematic graphical representation of the islands was created and simplified to abstract direct geometries (Figure 04 and 05).

Graphics were laser cut out of a polymeric sheet to be applied as a mask on the glass surface. Murrine canes were studied according to their layers of colours and transparency to be associated with each island representation. The collection in its first batch included 4 island tables in different scales, and a standing lamp called Moon, as a metaphor for the natural forces that control the tides. All surfaces include an intact part of outer glass layers and a decorative part of diverse colours and transparency. The island Poveglia becomes a side table, represented through its water canal that divides the island into a natural environment and a man-made architectural one. Mazzorbo,

Fig. 04 and 05 Mapping and schematising the islands of Venice’s lagoon. Studio Omri Revesz

narrow and long in its form, becomes a higher console decorated with dots and lines, a symbol of its local Castraure artichoke fields (Figure 06, 07 and 08).

Lunardelli Venezia, a local PMI with a long heritage of manual and digital woodcraft, beyond the formation of the moulds of the experimental phase, had worked on the manufacturing of the wooden base for the tables and lamps, using a combined process of CNC milling of the legs and manual craft finishes. Further, to add value to the products and tell the story of the context and process, Lunardelli integrated a digital chip into the solid wood, inviting people to use digital devices and link back to an online media page. The wooden base structure was inspired by the bricole pillars in Venice lagoon that rise out of the water level to mark the paths of navigation canals.

Conclusions1

A sustainable future lies within the intersection of cultural heritage, human aspirations and technological advantages. Through this project, a solid collaboration between four cross-disciplinary realities was created to explore the synergic opportunities of shared know-how of the private sector and universities on a strictly local scale. The project raised interest both from local and international communities as an inspirational reference both for its cultural aspirations and technical solutions. The project was exhibited first during the Venice Glass Week and further at Milan Design Week Fuorisalone, part of the exhibition Reflected/Reflections at Teatro Franco Parenti, including the complete collection and the entire sample batch of the process. Further, the collection formed a social space at Venice Pavilion during Venice Art Biennial.

A sustainable future for Murano glass means a shift from a puritan to contaminated thinking and manufacturing. Even Though the craft of Murano is historically considered a highly reserved practice, where methods and know-how are kept secret from other industries, the collaboration, in this case, showed clear advantages in terms of innovative thinking and results. Digital and manual are not contradictions but complementary. Often, when facing the conflict between digital and manual craft, these two are perceived as concurrent. The combination of these two dimensions in the project Isole results in an equilibrated outcome, where both techniques are represented and needed.

Technical development requires a commercial orientation. A multidisciplinary project such as Isole must also include a commercial marketing partner, to create strategies and direct the implementation to the market from the very early stages of work. Technical, artistic and commercial know-how are crucially equal parts of the whole.

1 Isole project is a shared effort of Omri Revesz, Giada Consegnani and Marco Kotov from Omri Revesz Design studio, Damiano Frison from FabLab Ca’ Foscari University, Marcello and Paolo Moretti from Ercole Moretti and Agnese and Sebastiano Lunardelli from Lunardelli Venezia.

Social sustainability and continuity: Reducing costs and therefore reducing labour carry a risk of damaging the social structure of an industry. Nevertheless, while looking at the bigger picture, without evolving those processes into an up-to-date cultural heritage, the risk is a complete extinction of that industry for a lack of interest from the young generations. A constant exploration and evolution is a key to maintaining those industries alive, rather than their preservation. As stated by Mark Wigley in the book Preservation is overtaking us (Koolhaas and Otero-Pailos, 2014, p. 11) “Preservation is always suspended between life and death - calling on us to get smarter, faster, deeper, longer, sharper, and I would say more tender”.

Tradition and the human factor: desires, interest, satisfaction. By intervening in the traditional process and introducing digital technologies, new methods and product applications are possible. Thus, the industry becomes more attractive to younger entrepreneurs and designer generations. If cultural heritage testifies to the spirit of an epoche, it is only reasonable to investigate how the technologies that are associated with our times can impact, contribute and help evolve the art of Murano glass.

Fig. 06 Isole collection of tables, front view of Poveglia. Lunardelli Venezia Fig. 07 and 08 Isole collection of tables, a detail and the top view of Mazzorbo. Lunardelli Venezia

References

Bonfanti, A., Del Giudice, M., Papa, A. (2018). Italian craft firms between digital manufacturing, open innovation, and servitization. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, vol. 9, n. 1, pp. 136-149. Johnson, O. T. C. (2015). Glass, Pattern, and Translation: A Practical Exploration of Decorative Idiom and Material Mistranslation using Glass Murrine. PhD thesis. London: Royal College of Art. Koolhaas, R., Otero-Pailos, J. (2014). Preservation is overtaking us. New York: GSAPP Books.