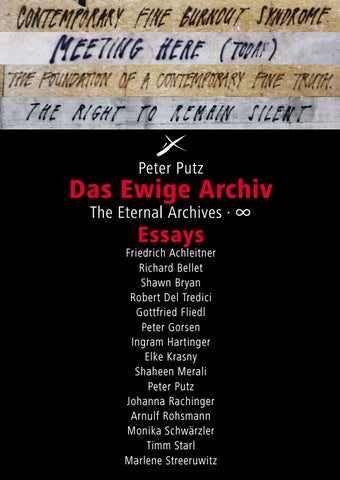

Peter Putz

Das Ewige Archiv The Eternal Archives · ∞

Essays

Friedrich Achleitner Richard Bellet Shawn Bryan Robert Del Tredici Gottfried Fliedl Peter Gorsen Ingram Hartinger Elke Krasny Shaheen Merali Peter Putz Johanna Rachinger Arnulf Rohsmann Monika Schwärzler Timm Starl Marlene Streeruwitz

Das Ewige Archiv · New Stuff (2014) 8 Johanna Rachinger Bibliotheken und die subversive Kraft der Erinnerung 10 Libraries and the Subversive Power of Remembrance 12 Shaheen Merali

Der lange Atem 14 The Long Breath 16

Elke Krasny

Aktivist Archivar Künstler Fotograf 18 Activist Archivist Artist Photographer 22

Gottfried Fliedl

Besichtigungen im „Ewigen Archiv“ 26 Touring the ”Eternal Archives” 30

Ingram Hartinger

Über das Archivieren des Ephemeren On Archiving the Ephemeral

34 36

Shawn Bryan

Ein anderes Licht? A Different Light?

38 39

Peter Putz

Woher kommen Bilder, was tun sie hier, wohin gehen sie? 40 Where do pictures come from, what are they doing here, where are they going? 41

Das Ewige Archiv · Heavy Duty XS (2012) Friedrich Achleitner MI & (lano) = MI & (stelbach) MI & (lano) = MI & (stelbach) [E]

44 46 47

Richard Bellet

L‘écho des photos, le poids des maux Echo der Photos, Gewicht des Bösen The Echo of Photos, the Weight of Evil

48 49 49

Robert Del Tredici

Photographing the Bomb: what kept me going 50 Die Bombe fotografieren: was mich weitermachen ließ 51 Photographing the Bomb (photos) 52

Peter Gorsen

Salvador Dalís fabulierte Wahnwelt im Vergleich mit . . . Salvador Dalí’s Fable-like World of Madness and . . .

54 55

Timm Starl

Das Archiv der Fotografie The Archive of Photography

56 58

Marlene Streeruwitz Occupy Occupy [E] Peter Putz

60 62

Was ich nicht fotografieren darf 64 What I’m not allowed to photograph 65

Das Ewige Archiv · Virtual Triviality (1994) 66 Kritiken | Reviews Das Ewige Archiv | The Eternal Archives · Virtual Triviality 68 Gottfried Fliedl

Das Ewige Archiv 70 The Eternal Archives 71

Monika Schwärzler

Vom Vergnügen und Ungenügen an Oberflächen 72 Of Pleasure and the Insufficiency of Surfaces 73

Das Ewige Archiv Kassettenedition The Eternal Archives – Wooden Box Edition (1987) 74 Gottfried Fliedl Das Ewige Archiv 78 The Eternal Archives 81 Arnulf Rohsmann

Text zur Kassettenedition 84 Essay for the Wooden Box Edition 85

Ingram Hartinger

Impressum | Imprint Biographie | Biography Humor und Schärfe | Humor and Sharpness

86 86 88

„Man muss den Dingen eine Form, eine Ordnung geben können, um sie besser zu verstehen, und das ist es auch, was man tut, wenn man einen Film macht oder anders künstlerisch tätig ist: Man versucht, zumindest temporär, eine Ordnung einzuführen und ein oder zwei Fragen auf diese Weise zu klären – weil man das chaotische Ganze ohnehin nicht erfassen kann. Ich glaube, das ist eine Art, um die Unordnung, in der wir leben oder als die wir die Welt empfinden, auszuhalten.“ Agnès Varda

“You have to give things a form, an order, so you can understand them better. And that is what you do when you make a film or engage in other artistic activity: you try to introduce order, at least temporarily, so as to clarify one or two questions because there is no way to grasp chaos in any case. I think that this is a way of tolerating the disorder in which we live or perceive the world.” Agnès Varda

« Il faut pouvoir donner une forme, un ordre aux choses pour mieux les comprendre; c’est aussi en cela que consiste la réalisation d’un film ou toute autre activité artistique : nous essayons, du moins temporairement, d’introduire un ordre et d’élucider ainsi une ou deux questions – car on ne peut, de toute façon, saisir le tout chaotique. Je crois que c’est une manière de supporter le désordre dans lequel nous vivons ou sous la forme duquel nous ressentons le monde. » Agnès Varda

4

Das Ewige Archiv wurde im Jahr 1980 von Peter Putz gegründet und versteht sich als dynamische Enzyklopädie zeitgenössischer Identitäten. Es ist eine der umfangreichsten nichtkommerziellen und unabhängigen Bilddatenbanken Österreichs, mit einem Bildbestand ab dem Jahre 1905, mit Metadatenverzeichnis und detaillierter Beschlagwortung. Schwerpunkt ist die permanente fotografische Notiz: Spurensicherung des Alltags, Dokumentation und Vergleich unterschiedlicher Lebens- und Arbeitsräume: Wien und Montréal, Ebensee und Poznan´, London, New York, Berlin, Lissabon ebenso wie Paris, Vandans, Bagdad und Rom. Diese Aufzeichnungen verdichten sich zu größeren Bezugsräumen und bilden ein facettenreiches Gewebe verschiedenster Realitäten mit besonderem Augenmerk auf Spektakulär-Unspektakuläres. Bilder der Sammlung werden zu themenbezogenen Tableaux zusammengefasst.

The Eternal Archives were created by Peter Putz in 1980 and can be understood as a dynamic encyclopedia of contemporary identities. They are one of Austria’s most comprehensive non-commercial, independent image databases, with images dating from 1905 and a metadata index with detailed keyword referencing. The focus is on photographic note-taking: preserving traces of everyday activity, documenting and comparing a variety of places where people live and work – Vienna and Montreal, Ebensee and Poznan´, London, New York, Berlin, Lisbon, as well as Paris, Vandans, Baghdad and Rome. These photographic records interconnect to form a multi-facetted network of greatly differing realities, with particular attention being paid throughout to the profane, the normal, the ordinary and thus pointing out its importance. Images have been collated into thematic tableaux.

5

Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier Ausstellung ¡ exhibition 2014 6

7

2014 Peter Putz

DAS EWIGE ARCHIV The Eternal Archives · ∞

New Stuff

248 Seiten · pages, deutsch · english Hardcover, Schutzumschlag · dust jacket Ritterverlag, Wien · Klagenfurt, 2014 www.ritterbooks.com 100 Tableaus: Peter Putz 7 Essays: Shawn Bryan, Gottfried Fliedl Ingram Hartinger, Elke Krasny Shaheen Merali, Peter Putz Johanna Rachinger Extras: Matthias Marx, Johann Promberger Karl A. Putz

8

Peter Putz

DAS EWIGE ARCHIV The Eternal Archives · ∞

New Stuff RITTER

9

Bibliotheken und die subversive Kraft der Erinnerung Johanna Rachinger

Gedächtnisinstitutionen – wie Bibliotheken, Museen oder Archive – stehen in einem permanenten Kampf gegen das Vergessen. Er gleicht einer Sisyphos-Arbeit, da er niemals endgültig zu gewinnen ist, sondern die Aufgabe der Sicherung unseres Wissens nur immer an die nächste Generation weitergegeben werden kann. Warum, so könnte man fragen, lassen wir uns auf diesen scheinbar aussichtslosen Kampf überhaupt ein und akzeptieren nicht einfach die Vergänglichkeit alles Irdischen? „Glücklich ist, wer vergisst ...“, heißt es in einer Wiener Operette. Verlieren wir unsere Geschichte, so verlieren wir auch das Verständnis für die Gegenwart – und damit auch unsere Zukunft. Wer sein Gedächtnis verliert, ist geistig tot. Darum haben alle Kulturen und Gesellschaften versucht, vergangenes Wissen und Wissen über Vergangenes zu bewahren und an die nächste Generation weiterzugeben. In der Geschichte erkennen wir unsere Wurzeln und damit unsere eigene geistige und kulturelle Identität. Der französische Philosoph Maurice Halbwachs hat darauf hingewiesen, dass unser individuelles Erinnerungsvermögen notwendig eingebettet ist in einen sozialen Erinnerungsrahmen, den er mit dem Begriff des „kollektiven Gedächtnisses“ zu umschreiben versuchte.1) Moderne GedächtnisforscherInnen wie Aleida Assmann haben mit dem Begriff des „kulturellen Gedächtnisses“ eine über die zeitlichen Grenzen des kommunikativen (sozialen) Gedächtnisses hinausgehende Dimension beschrieben, die wesentlich auf materiellen Dokumenten beruht. Dieses kulturelle Gedächtnis bleibt auf Dauer nur bestehen, wenn es Institutionen gibt, die es bewahren. Dies verweist direkt auf die grundlegende gesellschaftliche Aufgabe von Gedächtnisinstitutionen wie Nationalbibliotheken und -archiven, nämlich das in Dokumenten niedergelegte, über viele Generationen gesammelte Wissen für die Zukunft zu bewahren. Heute ist die Menge des im „Speichergedächtnis“ von Bibliotheken und Archiven angesammelten Wissens längst unüberschaubar geworden. Nur Ausschnitte davon können nach jeweils selektiven Interessen ins aktuelle Blickfeld einer Gesellschaft – in das „Funktionsgedächtnis“, wie Aleida Assmann es nennt – emporgehoben werden. Sie spricht deshalb von einem charakteristischen Spannungsverhältnis zwischen „Erinnertem und Vergessenem, Bewusstem und Unbewusstem, Manifestem und Latentem“2), das es uns erlaubt, Geschichte immer wieder neu zu bewerten und neu zu interpretieren. Außer Zweifel steht, dass unsere gesamte Kultur auf einer zumindest in großen Zügen funktionierenden Wissenstradierung beruht. Wissenschaftliche Forschung, ein Fortschritt im menschlichen Wissen überhaupt, ist nur möglich, weil wir auf den Erkenntnissen – und Irrtümern – unserer Vorgänger aufbauen können und nicht jede Generation in ihrem Wissenserwerb bei Null zu beginnen braucht. Jedes einzelne Dokument aus dem Wissensspeicher der Menschheit, das unwiederbringlich verloren geht, hinterlässt eine Lücke in unserem kulturellen Gedächtnis. Der Brand der legendären Bibliothek von Alexandria hinterließ einen gigantischen Krater des Vergessens. Das „Memory of the World“-Programm der UNESCO steht für diesen wichtigen Aspekt der Wissensbewahrung. Es versammelt Dokumente aus aller Welt, die symbolisch das gemeinsame 10

kulturelle Gedächtnis der Menschheit repräsentieren. Mit bereits 13 Einträgen – sieben davon von der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek – ist Österreich eines der am prominentesten vertretenen Länder im „Memory of the World“-Programm.3) Daraus ergeben sich für die mit der Wissensbewahrung befassten Institutionen zweierlei grundlegende Aufgaben. Einerseits gilt es, die in Dokumenten niedergelegten Inhalte unseres Wissens zu bewahren, andererseits aber auch, das Wissen um ihre Interpretation lebendig zu erhalten. Über Jahrhunderte und bis heute wurden und werden die originalen Trägermedien – Papyri, Handschriften, Drucke etc. – selbst sorgsam und dauerhaft aufbewahrt. Heute kommt die Möglichkeit dazu, rechtzeitig digitale Substitute der Originaldokumente herzustellen. Dieser neue Weg eröffnet uns enorme Chancen: Zum einen können auf diese Weise auch die Inhalte von jenen Dokumenten gerettet werden, deren physischer Zerfall nicht dauerhaft zu verhindern ist. Zum anderen ermöglichen digitale Wissensspeicher einen direkten und einfachen Online-Zugriff auf die Informationen, wobei gleichzeitig die Originaldokumente geschont werden. Mit dem Übergang ins Zeitalter digitaler Medien treten aber auch neue Themen in den Mittelpunkt. Dabei geht es weniger um die Sicherung der elektronischen Datenträger selbst, sondern primär darum, die auf digitalen Medien gespeicherten Informationen lesbar zu erhalten. Der dynamische Wechsel der Hard- und Softwarestandards erfordert komplexe und kontinuierliche Anstrengungen sowie Institutionen, die diese Aufgabe leisten können. Unter dem Titel „Langzeitarchivierung“ hat sich an Bibliotheken und Archiven längst eine eigene Disziplin etabliert.4) Neben diesem technischen Aspekt der Archivierung von Information stellt sich aber eine ebenso wichtige komplementäre Aufgabe: Es nützt wenig, Jahrtausende alte ägyptische Papyri zu bewahren, wenn niemand sie zu entziffern vermag. Wenn es uns nicht mehr gelingt, die Zeichen aus der Vergangenheit zu entschlüsseln, bleiben es stumme, unverständliche Symbole. Eine historische Urkunde, die niemand mehr interpretieren kann, ein Bild, von dem niemand mehr weiß, wen oder was es darstellt, verliert seinen eigentlichen Sinngehalt. Genauso wichtig wie die Bewahrung der Information selbst ist also die Kompetenz, sie zu interpretieren. Beide Komponenten haben aber eine entgegengesetzte zeitliche Dynamik, denn der „Zahn der Zeit“ nagt unerbittlich: Ist ein Dokument einmal zerstört, ist es unwiederbringlich verloren. Bei der Entschlüsselung und Interpretation historischer Dokumente hingegen können wir auch auf künftige Forschergenerationen hoffen, solange die Quellen selbst noch verfügbar sind. Die Hieroglyphen konnten beispielsweise erst nach vielen Jahrhunderten der Vergessenheit wieder entschlüsselt werden. Genauso wie historische Dokumente von spezifisch darauf ausgerichteten Gedächtnisinstitutionen bewahrt werden müssen, weil sie „von selbst“ nicht erhalten bleiben würden, so bedarf die Kompetenz zur Interpretation dieser historischen Quellen einer systematischen Pflege in einem wissenschaftlichen Umfeld. Wissensbewahrung steht in einem charakteristischen Naheverhältnis zu politischen Machtstrukturen. Aleida Assmann spricht von einer „charakteristischen Allianz von Herrschaft und Gedächtnis.

Politische Machthaber sind kaum je an einer objektiven, wertfreien Bewahrung von vergangenem Wissen und Wissen über Vergangenes interessiert. Darin kommt eine fast paranoide Angst vor der subversiven Kraft von Archiven und Bibliotheken zum Ausdruck. Denn in den riesigen Gedächtnisspeichern wird sich immer auch politisch Unliebsames, ideologisch Verpöntes, offiziell tot Geschwiegenes finden, das die eigene Machtposition und Legitimation in Frage stellt. Genauso wie das kulturelle Gedächtnis also zur Legitimation bestehender Machtverhältnisse verwendet werden kann, kann es auch zu deren Infragestellung und Umsturz genutzt werden. In diesem Sinn fungieren Bibliotheken und Archive niemals bloß als Institutionen der Machtlegitimation, sondern immer auch als ihr Gegenteil: als potentielle Orte des Widerstandes, der Kritik und der Subversion. Vorausgesetzt allerdings, dass ihre Aufgabe des Sammelns und Bewahrens nicht von vorneherein einer ideologischen Kontrolle unterworfen ist. Es ist klar, dass ideologisch „gleichgeschaltete“ Archive und Bibliotheken sich in letzter Konsequenz selbst zerstören, weil sie die ihnen eigene Aufgabe als kulturelles Gedächtnis nicht mehr erfüllen können. Der Schweizer Literaturwissenschaftler Peter von Matt formulierte pointiert: „Die Vergangenheit und die Zukunft stehen miteinander in einem geheimnisvollen Stoffwechsel. Als dessen Zentralorgan fungieren die grossen Bibliotheken, die alles Vergangene ohne Rücksicht auf Aktualität für die Zukunft bewahren. […] Der Wille zur Totalität steckt nämlich als geheimer Wahn, als eine Art angeborene Besessenheit im Wesen der Bibliothek. […] Die Bibliothek muss das aufbewahren, worin sich eines Tages eine neue Zeit erkennt, muss es aufbewahren, ohne wissen zu können, was das ist und wo in ihren Lagern und Gestellen die schlafenden Hunde liegen.“6) Nur in diesem Anspruch auf Objektivität und Totalität können Gedächtnisinstitutionen ihrer Funktion als Hüter des kulturellen Gedächtnisses gerecht werden. Sie müssen versuchen, möglichst „alles“ zu sammeln – im Rahmen ihrer technischen und ökonomischen Möglichkeiten. Denn wir können heute noch nicht wissen, was zukünftige Generationen interessieren wird. In diesem Sinne muss das Wissensarchiv immer versuchen, zweckfrei und politisch unabhängig zu agieren, denn nur dann bleibt es eine unerschöpfliche Quelle überraschender Entdeckungen und geistiger Inspiration.

1) Maurice Halbwachs, Das Gedächtnis und seine sozialen Bedingungen, Berlin 1966 [Orig.: Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. Paris 1925] 2) Aleida Assmann, Von individuellen zu kollektiven Konstruktionen von Vergangenheit. Vortrag an der Universität Wien am 6.6.2005. 3) Zuletzt wurde im Juni 2013 die „Goldene Bulle“ als deutsch-österreichische Gemeinschaftsnominierung in die Liste des Weltdokumentenerbes aufgenommen. Vgl.: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/flagship-project-activities/memory-of-the-world/register/access-by-region-andcountry/europe-and-north-america/austria 4) Vgl. dazu z.B. die von der UNESCO organisierte Konferenz The Memory of the World in the Digital Age. Digitization and Preservation. An international conference on permanent access to digital documentary heritage. September 2012, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Conference Proceedings sind online zugänglich unter: http://www.ciscra.org/docs/UNESCO_ MOW2012_Proceedings_FINAL_ENG_Compressed.pdf 5) Aleida Assmann, Erinnerungsräume. Formen und Wandlungen des kulturellen Gedächtnisses. München 1999; S. 138 6) Peter von Matt, Die Vergangenheitsmaschinen. Die paradoxe Aufgabe der Bibliotheken im Kontext von Kultur und Wissenschaft. Neue Zürcher Zeitung vom 18. 4. 2005

Foto: © Hauswirth

Legitimation ist das vordringliche Anliegen des offiziellen oder politischen Gedächtnisses.“5) Herrschaft wurde gewöhnlich mittels ausgeklügelter Vergangenheitskonstruktionen legitimiert – und damit auch der Anspruch auf ihre unbegrenzte Fortsetzung. Der Versuch, auch die Vergangenheit vollständig unter ihre Kontrolle zu bringen und damit Geschichte als ihre eigene Legitimations- und Ruhmesgeschichte umzuschreiben, ist ein Kennzeichen totalitärer Macht. George Orwell hat diesen Vorgang, der sich in vielen Diktaturen der Welt bis heute abspielt, literarisch überzeichnet in seinem berühmten Roman 1984 dargestellt.

J. R., 2014 Dr. Johanna Rachinger, seit Juni 2001 Generaldirektorin der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, studierte Theaterwissenschaft und Germanistik an der Universität Wien. Von 1995 bis 2001 war sie Geschäftsführerin des Verlags Ueberreuter. Dr. Rachinger wurden zahlreiche Auszeichnungen verliehen, darunter WU-Managerin des Jahres 2012, Österreicherin des Jahres 2010 in der Kategorie „Kulturmanagement“ und der Wiener Frauenpreis 2003. Von 2004 bis 2009 war sie stellvertretende Vorsitzende des Österreichischen Wissenschaftsrates. Sie ist Mitglied des Senats der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften und Aufsichtsrätin der DIE ERSTE österreichische Spar-Casse Privatstiftung.

11

Libraries and the Subversive Power of Remembrance Johanna Rachinger

Memory institutions – such as libraries, museums or archives – are engaged in a constant struggle against oblivion. The struggle resembles a Sisyphean task, because it can never be won conclusively; the job of safeguarding our knowledge can only be passed on from one generation to another. So one might ask why we even bother undertaking such a seemingly hopeless struggle rather than simply accepting the transitory nature of all earthly things. “Happy is he who forgets…” says the song in a familiar Viennese operetta. If we lose our history, we also lose our ability to understand the present – and our future. To lose one’s memory is to die an intellectual death. For this reason, all cultures and societies have sought to preserve past knowledge and knowledge of the past and to transmit it to posterity. In history we recognize our roots and, consequently, our own intellectual and cultural identity. The French philosopher Maurice Halbwachs advanced the thesis that our individual ability to remember is necessarily embedded in a social remembrance-framework, which he proposed to refer to as “collective memory”.1) With the notion “cultural memory”, modern memory researchers such as Aleida Assmann have described a dimension that extends beyond the temporal boundaries of communicative (social) memory, one that depends to a great extent on material documents. The longevity of this cultural memory depends on the existence of institutions that are able to preserve it. This points directly to the fundamental, societal task of memory institutions such as national libraries and archives, namely, the preservation, for the future, of knowledge gathered over many generations and recorded in documents. Today, the amount of knowledge collected in the “storage memory” of libraries and archives has increased beyond quantification. Only portions of this knowledge can be brought into social focus at a time – or called up into what Aleida Assmann refers to as “functional memory” – according to the selective interests of the day. For this reason, she speaks of a characteristic stress ratio between “the remembered and the forgotten, the conscious and the unconscious, the manifest and the latent”2), which allows us continually to reevaluate and reinterpret history. There is no doubt that our entire culture relies on a transmission of knowledge that functions in at least general terms. Scientific research, any advance at all in human knowledge, is only possible because we are able to build on knowledge gained by those who came before us – and on their errors – rather than having to start from scratch, generation after generation, in our acquisition of knowledge. Every single document of humanity’s store of knowledge that is irretrievably lost leaves a void in our cultural memory. The burning of the legendary library at Alexandria created a gigantic crater of oblivion. UNESCO’s “Memory of the World” program addresses this vital aspect of the preservation of knowledge. The program aims at gathering documents from all over the world, documents that symbolically represent the common cultural memory of mankind. Austria, which has already made 13 contributions – seven of which from the Austrian National Library –, is one of the most prominently represented countries in the Memory of the World program.3 12

It follows from this that institutions concerned with the preservation of knowledge are faced, fundamentally, with a twofold task: on the one hand, they must safeguard knowledge content recorded in documents, and at the same time they must perpetuate the knowledge necessary for its interpretation. For centuries, original materials themselves – papyri, manuscripts, prints, etc. – have been and continue to be preserved with care and concern for their long-term conservation. In addition to this, we now possess the means to create digital surrogates for original documents in time to ensure their survival. This opens up new prospects: on the one hand, we can thus salvage what is recorded in documents whose physical disintegration cannot permanently be prevented; and, on the other, the digital storage of knowledge offers us direct and simple online access to information, while at the same time enabling us to spare the original documents. However, the transition to the age of digital media raises new issues of central importance. Crucial here is not so much the matter of safeguarding the electronic storage media themselves, but rather that of ensuring durable access to the digitally stored information. The dynamic changes in hardware and software standards demand complex, continuous efforts to adapt, as well as institutions that are up to the task. “Digital preservation” has long since become a discipline in its own right in libraries and archives.4) Inseparable from this technical aspect of archiving information is an equally important and complementary task: it does little good to preserve ancient Egyptian papyri if no one is able to decipher them. If we can no longer manage to decrypt the signs from the past, they remain mute, unintelligible symbols. A historical document that no one can interpret anymore, a picture of someone or something that no one can recognize anymore, loses virtually all significance. Just as important as the storage of information itself, then, is the nurturing of competence necessary for its interpretation. However, both of these components find themselves in a dynamic relation with time – for unrelenting are the “ravages of time”. Once a document has been destroyed, it is lost forever. On the other hand, in order to decipher and interpret historical documents, we can also look to future generations of researchers for help, so long as the sources themselves are still available. To cite a notable example: it was not until hundreds of years after falling into oblivion that hieroglyphic script could finally be deciphered. Historical documents, being unable to survive “on their own”, must be preserved by memory institutions specifically conceived for the purpose; but as a corollary, the competence needed to interpret these historical sources requires systematic cultivation in a scientific environment. Preservation of knowledge stands in a characteristic, close relationship to power structures. Aleida Assmann speaks of a “characteristic alliance between political rule and memory. Legitimation is the top priority of official or political memory.”5) Political rule – and by the same token its claim to perpetuity – has usually been legitimated by means of elaborate constructs of the past. The attempt to bring the past, among other things, completely under its control – and in the process rewriting history as a history of its own legitimacy and glory – is a characteristic trait of totalitarian power. George Orwell illustrated this process, amplifying it literarily, in his famous novel 1984.

Hardly ever are those who possess political power interested in preserving past knowledge and knowledge about the past in an objective, unbiased way. In this we see an expression of an almost paranoid fear of the subversive power of archives and libraries. For among the things that can be found in these enormous stores of memory, there will always be those that are politically undesirable, ideologically frowned upon, officially hushed up, things that put positions of power and legitimacy in question. Thus, cultural memory can be used to legitimate the existing balance of power just as well as it can serve to put it in question and upset it. In this sense, libraries and archives can never be seen solely as institutions whose function is to legitimate power, but also as precisely the contrary: as potential places of resistance, of criticism and of subversion. On the condition, however, that their mission to collect and preserve is not prejudiced from the start by any form of ideological control. It is clear that libraries and archives that are ideologically “brought into line” ultimately destroy themselves, because they can no longer perform their essential function as cultural memory.

1) Maurice Halbwachs: Das Gedächtnis und seine sozialen Bedingungen, Berlin 1966 [Orig.: Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. Paris 1925] 2) Aleida Assmann: Von individuellen zu kollektiven Konstruktionen von Vergangenheit. Lecture given at the University of Vienna on 6.6.2005. 3) Most recently, in June 2013, the “Golden Bull” of 1356, submitted jointly by Germany and Austria, was included in the Memory of the World Register. Cf.: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/ flagship-project-activities/memory-of-the-world/register/access-by-regionand-country/europe-and-north-america/austria 4) In this respect, see, for example, the conference organized by UNESCO, The Memory of the World in the Digital Age. Digitization and Preservation. An international conference on permanent access to digital documentary heritage. September 2012. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Conference Proceedings are available online at: http://www.ciscra.org/docs/ UNESCO MOW2012 Proceedings FINAL ENG Compressed.pdf 5) Aleida Assmann: Erinnerungsräume. Formen und Wandlungen des kulturellen Gedächtnisses. Munich, 1999; p. 138 6) Peter von Matt: Die Vergangenheitsmaschinen. Die paradoxe Aufgabe der Bibliotheken im Kontext von Kultur und Wissenschaft. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 4.18.2005.

As the Swiss literary scholar Peter von Matt pointedly put it: “The past and the future stand in a mysterious metabolic relationship with each other. In this metabolism, the great libraries serve as the central organ, in the sense that they preserve everything from the past regardless of possible significance for the future. […] Striving for completeness is indeed a secret compulsion, a kind of inherent obsession that belongs to the very essence of libraries. […] Libraries must preserve that in which a new era will someday be able to recognize itself, they must preserve this without knowing just what it is, without knowing where in their stacks and storage cabinets the sleeping dogs may lie.”6) It is only by staying true to their claim to objectivity and completeness that memory institutions can fulfill their function as guardians of cultural memory. They must do their best to collect “everything” – within the limits of their technical and economic means. For we cannot know today what will be of interest to future generations. In this sense, archives of knowledge must always endeavor to carry out their work without bias or political interference, for only then can they continue to be an inexhaustible source of surprising discovery and intellectual inspiration.

Wien | AT · 2012

Wien, Heldenplatz, 2012

Dr. Johanna Rachinger, Director-General of the Austrian National Library since 2001, studied dramatics and German philology at the University of Vienna. From 1995 to 2001 she was Managing Director and General Manager of the Ueberreuter Publishing House. Dr. Rachinger has been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Vienna Woman Award in 2003, Austrian of the Year in 2010 in the category “Culture Management”, and the University of Economics’ Manager of the Year in 2012. From 2004 to 2009 she was Deputy Chairwoman of the Austrian Science Board and is a Senate Member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Dr. Rachinger is a Supervisory Board Member of the ERSTE Foundation. 13

Der lange Atem Shaheen Merali

Wenn man nicht in Worte fassen kann, was man fühlt oder woran man glaubt, wenn man zudem nicht für sich behalten kann, was man über die Welt weiß, über ihre Räumlichkeit, oder wie einen das alles tagtäglich beeinflusst - was macht man dann? Wählt man dann die meditativen Möglichkeiten des Schweigens oder konzentriert man sich allmählich auch auf Möglichkeiten über das Unsagbare hinaus? Für viele Menschen mit dieser Tendenz entwickeln sich solche Möglichkeiten in unkontrollierbaren Formen und zeigen Spuren einer Ausgrabung von ungezügelten Phantasien. Die Resultate könnte man als poetisch oder paradox bezeichnen, Lösungen, Änderungen oder Modifizierungen, die uns dazu bringen, den Lauf unseres Universums zu verändern. Der vielzitierte erste Satz von Franz Kafkas tiefsinniger Erzählung Die Verwandlung ist ein wichtiges Beispiel: „Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheueren Ungeziefer verwandelt.“ Eine Art epistemologischer Lizenz gestattete es dem japanischen Schriftsteller Haruki Murakami zudem, seinen metaphysischen und bewusstseinsverändernden Roman Kafka am Strand zu schreiben. In beiden Erzählungen wurden die Werkzeuge und Instrumente, um das deutlich zu machen, immanent im Visuellen geschmiedet; eine Erweiterung des Visuellen, das nicht mehr in traditionellen Kategorien von Bezeichnungen verharrt, die das Geschriebene, Choreographierte oder Gemalte voneinander trennen. Davon zeugen etwa die gespenstischen Prozesse des Denkens. Der Prozess des Schaffens aus dem nicht Greifbaren, Unvergänglichen und sogar nicht Fühlbaren führt zu dieser Form der Visualisierung. Das übrig bleibende Material formt häufig mentale Bilder, mit deren Hilfe wir die zerbrechlichen visuellen Wahrnehmungen, aus denen sie ursprünglich entstehen, erfassen. Nicht alles ist möglich, aber Aspekte des Visuellen können im Lauf des kreativen Prozesses manchmal umfassender gemacht werden. Für jene, die derartig flüchtige Momente der Klarheit kommunizieren können, ist das, was sich zeigt, nicht die innere oder äußere Landschaft, sondern eine potente Mischung aus emanzipierter Erinnerung, die imstande ist, immense Komplexitäten des Imaginierten sowie des Emotionalen zu überbrücken. Im kreativen Prozess überlagern Visualisierungen die Fiktionalisierung oder das Erzählte. Daraus ergeben sich oft sensible Beschreibungen, mutige Gegenüberstellungen und dunkle Subversivität als Ausdrucksform. Der Schwerpunkt der Erzählung bewegt sich mehr auf der visuellen Ebene als auf einer geschriebenen oder artikulierten Vermittlung. Schließlich werden wir mit den Augen geboren, mit denen wir sterben, während alle anderen Organe wachsen und sich ab dem Zeitpunkt unserer Geburt ständig verändern. Für den „Ewigen Archivar“ Peter Putz ist das Visuelle zu einer täglichen Praxis des Aufzeichnens geworden, das Aufgezeichnete wird organisiert und behauptet seinen Platz in einer ständig anwachsenden, zusammengesetzten graphischen Darstellung. Dieses einsame Bemühen bestärkte seine künstlerische Überzeugung und produzierte ein verblüffendes Dokument von alltäglichen bis hin zu außergewöhnlichen Dingen, die seinen Lebensweg kreuzten. 14

Sein Lebenswerk, Das Ewige Archiv, hat in gewisser Weise Parallelen zur Veröffentlichung von Archivmaterial bestimmter Institutionen, wie das kürzlich beim Metropolitan Museum of Art der Fall war, das 400 000 Bilder online für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke veröffentlichte, oder beim British Pathé-Nachrichtenarchiv, das seine gesamte Sammlung von 85 000 historischen Filmen in hoher Auflösung auf ihren YouTube-Kanal lud. Das Ewige Archiv veröffentlicht und verbreitet sporadisch in Form von Broschüren, Publikationen, Filmen, Videos und als fotografische Arbeiten für ein Publikum, das sich seiner Ambitionen oder wie mit seinen Inhalten umzugehen ist, nie sicher sein kann, während es sich zwischen den Bereichen Dokumentation, künstlerische Fotografie, Tagebücher und Voyeurismus bewegt. Das Ewige Archiv ist ein turbulentes Unternehmen, es fühlt sich nie ganz gemütlich still an und sichert sich so einen Kultstatus in diesen bemerkenswerten Zeiten, wo mit einem Klick oder einem kurzen Befehl an Suchmaschinen eine riesige Datenmenge vor unseren Augen aufgelistet wird, die unseren Horizont begrenzt, indem sie unsere visuelle Reichweite limitiert. Ob per Instagramm, Pinterest, Downloads, in USB-Form, mit Picasa – diese Liste ist unglaublich lang und alle haben ihre tiefgreifenden Regeln und Philosophien, die bestimmen, wie wir die gesamte visuelle Bibliothek lesen, die angeboten wird. Diese Regeln basieren oft auf Sicherheitserfordernissen oder, etwa in früheren Zeiten, darauf, wie mit Wahrheit umgegangen oder wie Macht über den Körper oder die Gesellschaft ausgeübt wird. Wahrheiten schaffen ein Reservoir an Wissen in diesen Kontaktzonen, und wir, die Zuschauer, werden zu virtuellen Bürgern visueller Landschaften, besessen von den gemeinsam geteilten Erfahrungen, wobei wir das, was angeboten wird, ebenso kennenlernen wie das, was abgelehnt wird. Irrationale Gesetze darüber, was in ihren epistemologischen Grenzen präsentiert werden darf und was nicht, haben einen enormen Einfluss auf Facebook als Archiv. Indem Putz sich dieser konzeptuellen Strukturen der fiktiven und der gelebten Realitäten auf holistische Art und Weise bedient, um die Welt zu erfassen, gelingt es ihm, sein Ewiges Archiv aus täglichen Aufzeichnungen und zahlreichen „Feindflügen“, kombiniert mit zufälligen und entfremdeten Begegnungen, zu erschaffen. Das Ewige wird zur Gesamtheit seiner Fähigkeit, das Dokumentierte auf diesen formelhaften „Seiten“ zu rekonstruieren. Die „Seiten“, oft mit vier bis fünf Bildern einer beliebigen Situation, können zwischen dem Besuch eines Ateliers, eines Blumenladens, oder noch weiter hergeholt, Reiseberichten variieren. Durch die Platzierung auf ein und derselben „Seite“ agieren die Bilder wie eine Reihe von vorsichtigen Anmerkungen zu einer größeren Bildersammlung; Bilder, die sowohl räumliche als auch geografische zeitliche Bezüge verkörpern, und dabei, was das wichtigste ist, jede Menge über die Wissbegierde des Autors aussagen. Man kann von diesen „Seiten“ nicht erwarten, dass sie uns ein Gesamtbild davon geben, was in seinem Privatarchiv vorhanden ist oder nicht – die Ewigen Archive präsentieren ein teilweise vermitteltes Bild. Dieses selektive Archiv ist der Prozess, mit dessen Hilfe Putz das Ganze visualisiert, die Welt und seinen Platz in ihr – es ist eine Kostprobe und

zugleich die Summe dessen, was ausgewählt und veröffentlicht wird. Putz gelingt es, diese Visualisierung kontinuierlich durchzuhalten, indem er sowohl recht großformatige Bücher als auch ergänzende Supplemente in kleineren Editionen produziert, die seine Vorstellung vom Konstrukt des Ewigen zeigen. Seine Wahrnehmung der Welt rund um ihn in täglichen Aufzeichnungen, mit seinen lustigen Scherzchen vor der Kamera, wirkt endlos. Das Ewige muss eben tagtäglich hinzugefügt werden, ergänzt durch ausgedehntes Vagabundieren und repetitive Explorationen des Gefundenen, wodurch der Bezug zum bereits Archivierten verwischt wird.

Es ist eine Suche und auch eine Reise, die Peter Putz mit einer Freude und einer Leidenschaft unternimmt, die jede Seite durchdringt, eine Herausforderung und zugleich Zeugnis von der Sehnsucht, zu schaffen, was Kafka und Murakami gelang – der mäandernde Geist, der aus dem Alltäglichen eine Aussage über das Leben und Denken an den dunklen Rändern seiner digitalen Spur trifft. Wie Leslie Jamison kürzlich sagte: “…accumulation, juxtaposition, the organizing possibilities of metaphor. These techniques are ways in which the essay has always linked the private confessional to the communal…”1)

1) Leslie Jamison, Was sollte ein Essay können? Zwei neue Sammlungen, die die Form neu erfinden, 8. Juli 2013. http://www.newrepublic.com/article/113737/solnit-faraway-nearby-and-orange-running-your-life „…Akkumulation, Juxtaposition, die organisierenden Möglichkeiten der Metapher. Diese Techniken sind Formen, in denen der Essay schon immer die private mit der öffentlichen Beichte verbunden hat…” (Anm. d. Übersetzers) aus: Peter Putz, Das Ewige Archiv · New Stuff, Wien 2014, Ritter

Übersetzung aus dem englischen Original

S. M., 2014 Shaheen Merali ist Kurator und Autor, der zurzeit in London ansässig ist. Davor war er als Direktor für Ausstellungen, Filme und Neue Medien im Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2003-2008) tätig, wo er diverse Ausstellungen kuratierte und zugleich bedeutende Publikationen herausgab, wie zum Beispiel The Black Atlantic; Dreams and Trauma – Moving images and the Promised Lands und Re-Imagining Asia, One Thousand years of Separation. Merali war Co-Kurator der 6. Gwangju Biennale, Korea (2006). Nach seinem Deutschland-Aufenthalt kuratierte er zahlreiche Ausstellungen in Indien und im Iran; darauf folgte eine Zeit der Recherche und Beratung für die Erhaltung und zur Fertigstellung einer großen Ausstellung der International Collection of the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata (2010-2012).

Zu seinen neuesten Ausstellungen zählen: Refractions, Moving Images on Palestine, P21 Gallery, London; When Violence becomes Decadent, ACC Galerie, Weimar; Speaking from the Heart, Castrum Peregrini, Amsterdam; (After) Love at Last Sight / Nezeket Ekici Retrospective, PiArtworks , London und Fragile Hands, Universität für Angewandte Kunst Wien. Merali schrieb Essays für Kataloge, unter anderem über Agathe de Bailliencourt, Jitish Kallat, Sara Rahbar, TV Santhosh, Cai Yuan and JJ Xi (Madforeal). www.shaheenmerali.com

15

The Long Breath Shaheen Merali

If you cannot put into words what you feel or believe, if you cannot, at the same time, contain what you know about the world, its spatiality or how the whole effects your day to day - then what do you do? Do you seek the meditative possibilities of silence or gradually stage the possibilities beyond the unsayable? For many of such a disposition, the possible evolves in encroaching forms, bearing the marks of excavation from untamed imaginations. The results may be described as poetic or paradoxical, solutions, changes or modifications that persuade us to alter the passage of our universe. The much quoted opening line of the profound novel, Metamorphoses by Franz Kafka, is an important example: “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.” A certain epistemological license further authorised the contemporary Japanese writer, Haruki Murakami, to write his metaphysical mind-bender, Kafka on the Shore. In both novels the tools and means to make apparent were forged innately in the visual; an expanded visual which no longer remains contained in traditional categories of notations that separate the written, the choreographed or the painted. Herein the processes bear witness to the specters of thinking. The process of making from the intangible, the intransient, the untranslatable, and even the impalpable, results in this form of visualisation. The residual material often forms mental images that help us grasp the frail, visual perceptions from which they emerge in the first place. Not all is possible, but aspects of the visual can sometimes be made more comprehensive during the creative process. For those able to communicate through such fleeting moments of lucidity, then, what is represented is neither the internal nor the external landscape but a potent mixture of emancipated memory, bridging immense complexities of the imagined as well as the emotional. In forging creatively, visualisations supersede fictionalisation or narratives. In many ways what emerges are sensitive accounts, daring juxtapositioning and dark subversions as a form of expression. The narration continues, taking its emphases from the visual rather than from an inscribed or articulated transmission. We are, after all, born with the eyes that we die with as all other organs grow and constantly transform from the time of our birth. For the eternal archivist, Peter Putz, the visual has become a daily practice of recording, organising the recorded and reiterating its place in an ever-increasing composite graphic. This solitary effort has engaged his artistic faith, constructing a bewildering record from the mundane to the extraordinary that crisscrosses his life path. His lifework, The Eternal Archives, in many ways parallels the release of archived materials by institutions, as in the recent case of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, releasing 400,000 images online for non-commercial use or the newsreel archive, British Pathé, uploading its entire collection of 85,000 historic films, in high resolution, to its YouTube channel. Putz’s Eternal Archives release and sporadi16

cally emit, in the form of booklets, publications, films and videos as well as photographic works, for a public which is never sure of its ambition or how its contents are to be managed as it circulates in the field between documentary and fine art photography, diaries and voyeurism. The Eternal Archives are a turbulent entity, for they never sit entirely comfortably, ensuring them a cult status in these remarkable times, where, in a click or at a moment’s command, a vast amount is arranged before us by search engines, limiting our horizons by dictating our visual range. Instagrammed, pininterested, downloaded, usb(ed), Picasa(ed), the list is immense and all these have pervasive rules and philosophies that dictate the way we read the entire visual library that they supply. These rules are often based on security or, erstwhile, on how subjects inhabit truth or imply power over the body or society. Truths create a pool of knowledge in these zones of contact, and we, as viewers, become virtual subjects of visual lands, possessed by all the experiences that we share, becoming familiar with what is offered as much as by what is repudiated. Irrational laws, of what can and cannot be presented in its epistemological limit, heavily influence Facebook as an archive. In drawing on these conceptual frameworks of the imaginative and the lived realities as a holistic way to encapsulate the world, Putz manages to create his Eternal Archives from daily recordings and frequent sorties, in combination with accidental and estranged encounters. The eternal becomes the entirety of his ability to reconstitute the recorded in these formulaic “pages“. “Pages“ that often contain four to five images from a constituted situation can range from a studio visit to a visit to a florist or, further afield, studies as a tourist. In being placed within a ”page” the images act as a set of hesitative notations for a larger body of images, images that embody both spatial and geographical temporalities but, most importantly, speak volumes about the artist’s inquisitiveness. One cannot rely on these “pages“ to give us the full picture of those images that remain absent from or present in his private archive – The Eternal Archives present a partially mediated picture. This selective archive is the process through which Putz visualises the whole, the world and his place within it – it is both the taste and the sum of the culled and the framed. Putz has been successful in continually asserting this visualisation by producing both larger format books and smaller edition supplements that testify to his notion of the construct of the eternal. There is no seeming end to his capturing the world around him in daily recordings with his lens-based frolics. The eternal remains to be added to on a daily basis, supplemented by further roving and often-repetitive explorations of the found, confounding the relation to the already archived. It is both a quest and a journey, which Putz takes with a joy and passion that permeate all the pages, both challenging and giving testimony to the desire to create as Kafka and Murakami have done, the meandering mind making from the mundane a statement of living and thinking in the dark edges of his digital trace.

As Leslie Jamison recently said, “…accumulation, juxtaposition, the organizing possibilities of metaphor. These techniques are ways in which the essay has always linked the private confessional to the communal…”1)

1) Leslie Jamison, ”What Should an Essay Do? Two new collections reinvent the form“, July 8, 2013 http://www.newrepublic.com/article/113737/solnit-faraway-nearby-andorange-running-your-life

from: Peter Putz, Das Ewige Archiv · New Stuff, Wien 2014, Ritter

Shaheen Merali is curator and writer, currently based in London. Previously, he was Head of Exhibitions, Film and New Media at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin (2003-2008) where he curated several exhibitions accompanied by key publications, including The Black Atlantic; Dreams and Trauma – Moving images and the Promised Lands and Re-Imagining Asia, One Thousand years of Separation. Merali was the co-curator of the 6th Gwangju Biennale, Korea (2006). Upon leaving Germany he curated many exhibitions in India and Iran and then embarked upon a period of extensive research and consultation on the conservation and production of a major exhibition of the International Collection of the Birla Academy of Art and Culture, Kolkata (2010- 2012).

His recent exhibitions include Refractions, Moving Images on Palestine, P21 Gallery, London; When Violence becomes Decadent, ACC Galerie, Weimar; Speaking from the Heart, Castrum Peregrini, Amsterdam; (After) Love at Last Sight / Nezeket Ekici Retrospective, PiArtworks , London and Fragile Hands, University of Applied Arts Vienna. Merali has written catalogue essays on Agathe de Bailliencourt, Jitish Kallat, Sara Rahbar, TV Santhosh, Cai Yuan and JJ Xi (Madforeal) amongst others.

www.shaheenmerali.com

17

Aktivist Archivar Künstler Fotograf Elke Krasny

Mein erster Besuch im Ewigen Archiv fand im Frühling des Jahres 2014 statt. Hätte mich Peter Putz nicht kontaktiert und in sein Atelier eingeladen, dann hätte ich nie Kenntnis von der Existenz des Ewigen Archivs erlangt. Mit den Mitteln der Fotografie unternimmt Putz den Versuch, die Sprengkraft des Gegenwärtigen, die städtischen Veränderungen im Moment ihrer öffentlichen Erscheinung festzuhalten. Die so erzeugten Dokumente finden Eingang in das Ewige Archiv, welches seinen Standort im Atelier des Künstlers in der Mollardgasse im sechsten Wiener Gemeindebezirk hat. Putz verbindet das, was man als Studio Practice1) bezeichnet, seit vielen Jahren mit dem, was man als Post-Studio Practice bezeichnet. Sein Atelier ist Wien, die Stadt, in der er lebt und arbeitet, aber auch eine große Anzahl anderer Orte und Städte, in die ihn seine Lebens- und Arbeitswege geführt haben. Sein Atelier in der Mollardgasse gibt dem Archiv Raum. Die Stadt und ihre öffentlichen Erscheinungsräume sind in diesem Archiv geborgen. Peter Putz agiert als Künstler und als Fotograf. Peter Putz agiert als Archivar und als Aktivist. Das Ergebnis ist das Ewige Archiv. In den Überlegungen dieses Essays werde ich untersuchen, wie diese vier unterschiedlichen Handlungsweisen, die des Künstlers, des Fotografen, des Archivars und des Aktivisten, sich zueinander verhalten. Mein besonderes Interesse gilt dabei der Frage nach den Bedingungen, Möglichkeiten, Grenzen und Konflikten im Agieren, im Handeln. Weiters werde ich die Frage aufwerfen, in welchem Verhältnis dieses selbstgewählte und selbstbestimmte künstlerisch-aktivistische Handeln zu den Ansprüchen der Öffentlichkeit steht. Zunächst werde ich mich mit dem Begriff des Handelns auseinandersetzen. In zeitgenössischen Theoriedebatten – mein Interesse gilt im Speziellen dem feministischen sowie dem kunsttheoretischen Kontext – wird die Frage der agency, die ich mit Handlungsmacht übersetzen möchte, intensiv diskutiert. In dem Buch Why Stories Matter. The Political Grammar of Feminist Theory widmet Claire Hemmings einen eigenen Abschnitt der Frage der Handlungsmacht, der agency. Sie weist darauf hin, dass Unabhängigkeit, Autonomie, Freiheit und Selbstbestimmung als bestimmende Faktoren einer westlichen Konstruktion von Handlungsmacht aufgefasst werden. (Hemmings 2011: 205) Wie die Autorin ausführt, richtet sich eine marxistische Kritik, wie die von Kalpana Wilson, an einer subjektzentrierten Handlungsmacht darauf, dass diese das Individuum über das Kollektiv stellt und zur Kapitalakkumulation anderer beiträgt. Aus einer machttheoretischen Perspektive kritisierte, wie Hemmings darlegt, Judith Butler das Konzept der Handlungsmacht, da dieses die Macht, die die Handlungen immer schon, ohne dass das Subjekt sich dafür entschieden hat, (mit) bestimmt, außer acht lässt. Mein Interesse am künstlerischen und aktivistischen Handeln gilt einer Handlung(smacht), die sich dieser Fallen bewusst ist und im Gestus des reflektierten Trotzdem weiterhin agiert. Ich verstehe Agieren folglich nicht in Unabhängigkeit von materiellen Bedingungen und Möglichkeiten, nicht in Unabhängigkeit von anderen handelnden Subjekten und nicht in Unabhängigkeit von Fragen der Macht. Handeln, wie ich es begreife, bedeutet Agieren mit und durch Ko-Existenz, Ko-Dependenz und Ko-Implikation. Ich verwende die beiden Begriffe Handeln und Agieren als austauschbar und habe das Agieren ebenfalls eingeführt, weil es, vermittelt über die lateinische Wurzel des Wortes agere, im Deutschen nochmals eine Nähe zum englischen Begriff der agency aufbaut. 18

Ich werde nun das Agieren des Künstlers, des Fotografen, des Archivars und des Aktivisten mit meiner Bestimmung des Handelns, das sich durch Ko-Existenz, Ko-Dependenz und Ko-Implikation auszeichnet, zusammenführen. Zwei der Positionen lassen sich aktiv als Handeln ausdrücken: fotografieren und archivieren. Zwei der Positionen hingegen benötigen ein sogenanntes Hilfszeitwort, das Wort Sein, Künstler-Sein und Aktivist-Sein, um als Agieren ausgedrückt zu werden. Weder gibt es das Zeitwort zu „künstlern“ noch gibt es das Zeitwort zu „aktivisten“. Beide, Künstler und Aktivist, brauchen daher, und ich betrachte dies von der wörtlichen sprachlichen Hilfskonstruktion ausgehend im übertragenen Sinn der materiellen, ästhetischen, bedeutungsproduzierenden, politischen Implikationen, Hilfe. Sie bedürfen der Unterstützung. Künstler-Sein und Aktivist-Sein hängt folglich ab von diesem spezifischen wörtlichen Verhältnis zum Sein. Es mangelt am Zeitwort, das alleine die Handlungen ausdrücken könnte, die der Künstler oder der Aktivist hervorbringt. Die Sprache liefert die Einsicht in diesen Umstand. Ich verwende das poststrukturalistische Wissen und den linguistic Turn nicht, um diesen dekonstruktivistisch mit den Mitteln der Sprache zu verfolgen, sondern vielmehr verwende ich dieses Wissen für eine materialistische Lesart in einer sozialen und politischen Ökonomie und für eine kritische Analyse der Verhältnisse zwischen der individuellen Produktion, der kollektiven Involviertheit, der individuellen Seins-Investition, den öffentlichen Ansprüchen und den institutionellen Zusammenhängen. Das Wissen aus der Sprache zeigt auf die Politik, die Ökonomie, die Ontologie, die alle gleichermaßen durch das Hilfszeitwort Sein mitbenannt sind. Von der Unterstützung, der Hilfe, des Hilfszeitworts Sein sind der Künstler und der Aktivist abhängig. Dieses Hilfszeitwort Sein führt uns zurück zur Ko-Existenz, zu dem, was gleichzeitig ist, zur Ko-Dependenz, zu dem, wovon es gleichermaßen ein Abhängigkeitsverhältnis gibt, und zur Ko-Implikation, zu dem, wovon die Positionen gleichermaßen erfasst sind. Ich werde mich nun im folgenden den Positionen (und Mythen) von Künstler und Aktivist zuwenden. Position (und Mythos) des Künstlers2) wurde historisch auf komplexe und komplizierte Weise mit Autonomie verbunden. In seinem Buch Anywhere or Not at all. Philosophy of Contemporary Art analysiert Peter Osborne den Begriff der Autonomie aus verschiedenen Perspektiven. Ich greife hier die Beziehung zwischen Autonomie und Ware heraus, um zu unterstreichen, dass die materielle Abhängigkeit (nicht die Unabhängigkeit von materieller Abhängigkeit, der Unterschied ist entscheidend) die Autonomie der Kunst (und der Position des autonom agierenden Künstlers) gleichermaßen ermöglicht und einfordert. Die Warenförmigkeit der Kunst ist die Ermöglichung ihrer Autonomie. “Autonomous art has always been for sale, as a commodity in the market. (Historically, the market is the social basis of art‘s autonomy from its previous social functions.) Autonomous works of art are thus always also commodities – (…). Autonomy is never a given. In so far as it exists it is the individual achievement of each work: the victory of technique (the principle of internal organization) over social conditions. Autonomy is the achievement, in each instance, of the production of a law of form.” (Osborne 2013: 166) Im Gegensatz zu dieser westlichen Konstruktion von Position und Mythos des Künstlers, der Kunstschaffen und Autonomie verbindet und im Kunstschaffen autonom bleibt und die Autonomie in der Kunst ausdrückt,

gibt die Sprache den Hinweis darauf, dass es sich beim Künstler-Sein um eine Position handelt, die auf der Zurverfügungstellung von Hilfe beruht. Die Autonomie ist folglich hilfsbedürftig. Dass die deutsche Sprache (für das Englische gilt dasselbe) kein eigenes Zeitwort ausgebildet hat, das aktiv zum Ausdruck bringt, was Künstler tun, was künstlerisches Agieren ist, verweist in meiner Lesart darauf, dass materielle und institutionelle Bedingungen für das Agierenkönnen als Ermöglichung hergestellt werden müssen, um diese (mythische) Konstruktion von Künstler und Autonomie zu produzieren und aufrechtzuerhalten. Das Hilfszeitwort Sein gibt den Hinweis darauf, dass Künstler-Sein existiert in Ko-Dependenzen und Ko-Implikationen, in Abhängigkeit von den Bedingungen und Möglichkeiten, die ein künstlerisches Werk ermöglichen und bedingen, und in Bezugnahme auf die (affirmierende, kritische, reflektierende, negierende, ignorierende) Artikulation dieser Implikationen, die das Werk ermöglichen und bedingen. Position (und Mythos) der Aktivist_In3) sind in ähnlicher Weise, wie die des Künstlers, in ihrem Verhältnis zu Autonomie zu problematisieren. Kämpfe um die Durchsetzung von (Wahl)Rechten, wie von den Suffragetten, um territoriale Selbstbestimmung, wie in den kolonialen Unabhängigkeitskriegen, oder um sexuelle Selbstbestimmung, wie von LGBT Organisationen, gehen von einem Subjektbegriff der Aktivist_In aus, die sich mit anderen Aktivist_Innen organisiert, politisch formiert und kollektiv agiert.4) Die geführten Kämpfe um Un-Abhängigkeit sind abhängig von den historischen Bedingungen, die sie zu überschreiten suchen. Sie sind abhängig von den materiellen, intellektuellen, emotionalen, ökonomischen Ressourcen, über die sie verfügen, die zu mobilisieren sie imstande sind. Wieder ist es die Ko-Existenz (die im Kollektiv organisierten aktivistischen Subjekte), die Ko-Dependenz (die Abhängigkeit in den Bedingungen, die überschritten und transformiert werden sollen), die Ko-Implikation (die Bedeutungen, die Existenzen und Abhängigkeiten zueinander konstituieren und mobilisieren), die ich für meine Lesart in den Vordergrund rücke. Der Künstler und die Aktivist_In haben ihre Positionen zu unterschiedlichen Zeiten miteinander verbunden und als Künstler-Aktivist_In5) agiert. Bevor ich mich nun den Positionen von Archivar und Aktivist zuwenden werde, möchte ich nochmals zusammenfassend betonen, dass der Kampf um die Autonomie, der durch die Positionen von Künstler und Aktivist_In und ihren jeweiligen Arbeiten (Kunstwerk, Kunstprozess, politische Selbstorganisation und Durchsetzung von Rechten, Zugang zu Ressourcen, Umverteilung etc.) ausgetragen wird, folgt man der Logik der Sprache, des Hilfszeitworts Sein bedarf. Autonomie bedarf der Hilfe, ist auf Unterstützung angewiesen, hängt von dieser ab. Der Kampf um die Autonomie braucht die Hilfe von Subjekten, wie Künstler oder Aktivist_innen, welche ihr Sein in diesen Kampf investieren. Um dieses Sein investieren zu können, bedürfen sie der Hilfe im materiellen wie immateriellen Sinne. Dies führt den Kampf um die Autonomie und die Investition in das Künstler-/Aktivist_in-Sein zurück in die Zyklen von Ko-Existenz, Ko-Dependenz und Ko-Implikation. Dem Fotografen und dem Archivar sind eigene Zeitworte zugeordnet. Er fotografiert. Er archiviert. Diese Handlungen kommen ohne Hilfszeitworte aus. Sie bedürfen der Hilfe nicht. Im Gegenteil, sie helfen. Die Handlungen dienen der Fotografie oder dem Archiv.

Historisch waren Fotografen nicht als autonome Künstler positioniert, ihre Profession war ein Gewerbe. Sie handelten im Auftrag anderer, für die Aufträge anderer. Sie handelten im Dienst anderer. Die Mittel des Fotografierens wurden in vielen verschiedenen Bereichen eingesetzt. Von der Polizei bis zur Archäologie, vom Journalismus bis zur Rechtssprechung, von der Anthropologie bis zur Architektur, vom Militär bis zum Städtebau wird das Fotografieren benötigt. Erst im Laufe des 20. Jahrhunderts als eigenständige Form innerhalb der bildenden Kunst anerkannt und den verschiedenen Technologieschüben folgend als Massenmedium der AmateurInnen etabliert, hat das Fotografieren eine ambivalente Position im Wissen, im Nützlichen, im Glaubwürdigen. Der Fotograf braucht das Hilfszeitwort Sein nicht. Sein Handeln kommt ohne Sein aus. Er fotografiert. Das Fotografieren steht im Dienst dessen, was sich auf den Fotografien zur Erscheinung bringt. Das, was sich zur Erscheinung gebracht hat, ist fotografisch festgehalten. Als Dokument, als Zeugnis, findet die Fotografie Eingang ins Archiv. Sie dient als Beleg dessen, was ist, als Zeugin der Ereignisse. Im Archiv werden die dort gesammelten und aufbewahrten Dokumente geordnet, erschlossen und zugänglich gemacht. Das Archiv ist eine öffentliche Einrichtung, die die Akten verwaltet. Archivieren umfasst alle Handlungen, die der Bewahrung, Erhaltung und Ordnung des Archivierten dienen. Durch die Akten erschließt sich der Zugang zur Geschichte. Die Lage der Akten ist eine geschichtspolitische Frage. Der Archivar braucht das Hilfszeitwort Sein nicht. Sein Handeln kommt ohne Sein aus. Er archiviert. In der Praxis von Peter Putz verbinden sich die von mir dargestellten Handlungsweisen. Putz agiert durch das Archivieren und das Fotografieren in Verbindung mit dem Künstler-Sein und dem AktivistSein. Er stellt seine Kunst und seinen Aktivismus als Position der Autonomie in den Dienst des Archivierens6), welches er mit den Mitteln der Fotografie unablässig und unterschiedslos betreibt. Da er als Künstler die Entscheidung getroffen hat, der Stadt ein Archiv zu erzeugen, zeigt sich in diesem immer weiter wachsenden Archiv die Entschlossenheit, mit der Putz die Konsequenzen dieser Entscheidung trägt und mit den Mitteln der Fotografie und dem Einsatz von Aktivismus als Archiv-Künstler lebt. Der Aktivismus hilft dem Archiv. Die Fotografie hilft der Kunst. Ersetze ich das Hilfszeitwort Sein, das der Künstler und der Aktivist brauchen, um ihr Agieren als Tätigkeit ausdrücken zu können, im Fall von Peter Putz durch die Tätigkeiten des Archivierens und des Fotografierens, so sehen wir, wie das den Künstler-Archivar und den Fotografen-Aktivist ergibt oder den Künstler-Fotografen und den Archivar-Aktivisten. Die Positionen ko-existieren, sind von einander ko-dependent und ko-implizieren einander. Wie diese Positionen sich zueinander verhalten in Hinblick auf Hilfe und Autonomie und welche Konflikte, sowohl theoretisch wie praktisch daraus resultieren, habe ich gezeigt. Peter Putz handelt im eigenen Auftrag. Als Künstler setzt er auf die Autonomie. Der Auftrag, den er sich gestellt hat, ist unbewältigbar, unabschließbar, immer größer als die Möglichkeiten, die dem Fotografen und dem Archivar zur Verfügung stehen. Die Stadt zu erfassen, in ihren Mikrotransformationen und ihren Makrotransformationen, ihren Situationen, Momenten, Langfristigkeiten, politischen Manifestationen, übersteigt die Möglichkeiten eines Einzelnen. Als Aktivist stellt er sich dieser permanenten Herausforderung und Überschreitung seiner Möglichkeiten. Wird der Markt im 18. Jahrhundert 19

zu jenem Mechanismus, der die Grundlage für die Autonomie der Kunst ermöglicht, so muss der Markt diese Möglichkeiten bieten und tragen. Trifft ein Künstler für seine Praxis, wie im Falle von Peter Putz, die Entscheidung, die Autonomie, die der Markt ermöglicht, durch die Autonomie, die der Aktivismus in kritischer Distanz zum Markt postuliert, zu ersetzen, so ist der Preis, um in der Sprache des Marktes und der Kunst als System von Anerkennung und Auszeichnungen zu argumentieren, der dafür bezahlt werden muss, hoch. Der Preis ist das Leben, das sich in das Ewige Archiv als unabschließbares Projekt investiert. Für das abschließende Argument und das finale Plädoyer dieses Essays kehre ich zur Situation zurück, die ich eingangs beschrieben habe. Peter Putz hat mich eingeladen, das Ewige Archiv in seinem Atelier zu besuchen. Hätte er mich nicht persönlich angesprochen, hätte ich von der Existenz des Ewigen Archivs nie erfahren. Es gibt kein öffentliches Wissen um die Existenz dieses Archivs. Ich habe mich bis jetzt den inhärenten Konflikten und Potenzialen, die aus allen denkbaren Verbindungen zwischen Künstler-Archivar und Fotografen-Aktivist resultieren, gewidmet und diese analytisch aufgezeigt und kritisch beleuchtet. Diese vier Positionen des Agierens bilden jedoch kein in sich geschlossenes System, in dem sie nur voneinander abhängen. Vielmehr ist allen vier gemeinsam, dass sie einen Anspruch stellen: den Anspruch auf Öffentlichkeit. Entsteht die Öffentlichkeit in dem Raum und durch den Raum, in dem sie sich zur Erscheinung bringt, und ich folge hier Hannah Arendts Begriff des Erscheinungsraums, wie er von Judith Butler kritisch weiter entwickelt wurde (Butler 2012: 117 und 118), dann braucht dieser Erscheinungsraum auch bleibende visuelle Dokumentationen, um ein langfristiges Erinnern an seine Existenz zu ermöglichen. In ihrem 2012 erschienenen Essay Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street stellt Judith Butler einen Zusammenhang her zwischen der politischen Theorie Hannah Arendts, die die Idee des Erscheinungsraums, der die Öffentlichkeit konstituiert, entwickelt hat, und dem physisch notwendigen Raum, der dieses Erscheinen materiell trägt und ermöglicht. Butler schreibt: “Human action depends upon all sorts of supports – it is always supported action.” (Butler 2012: 118). Der öffentliche Erscheinungsraum der Stadt ist die Voraussetzung für die Praxis von Peter Putz, zugleich bringt Putz diesen Raum in seinen fotografischen Dokumenten zur Erscheinung. Er hält diesen fest in seinem momenthaften Erscheinen, macht ihn archivierbar und dadurch (öffentlich) zugänglich. Ich habe das Öffentlich im vorangegangenen Satz eingeklammert, um auf die Potenzialität der öffentlichen Zugänglichkeit zu verweisen, die jedoch (noch) keine Realität ist, da zwar jedes Archiv dem Anspruch nach öffentlich ist, das Ewige Archiv als Kunstprojekt eines Individuums jedoch diesem Anspruch nicht gerecht werden kann. Daher braucht das Ewige Archiv Unterstützung. Jedes Dokument des Ewigen Archivs, jede Fotografie, die in das Archiv Eingang gefunden hat, vermag Einsichten zu vermitteln in die städtische Öffentlichkeit und den Erscheinungsraum, den die Öffentlichkeit produziert. Die Archivalien des Ewigen Archivs, die Fotografien, bringen Stadtgeschichte zur Erscheinung. Sie sind ein Teil des kollektiven Gedächtnisses von Stadt, das durch ein individuelles künstlerisch-aktivistisches Projekt getragen wird. Im Ewigen Archiv befindet sich eine Fülle von visuellen Dokumenten, die für HistorikerInnen, StadtforscherInnen, EthnologInnen, AnthropologInnen, ArchitekturhistorikerInnen, Kultur20

theoretikerInnen und StadtbewohnerInnen von Relevanz sind. Die Fotografien des Ewigen Archivs sind sich nicht selbst genug. Sie sind unabgeschlossen, sie benötigen und ermöglichen die weiterführende Bearbeitung, Erschließung, Erforschung. In Hinblick auf sein Archiv-Sein – und ich verwende hier nochmals das Hilfszeitwort Sein, um auf Judith Butler zu rekurrieren und auf den sozialen wie politisch relevanten Umstand, dass jede menschliche Handlung der Unterstützung bedarf, also auf Hilfe angewiesen ist, dann hat das Ewige Archiv nun einen kritischen Zeitpunkt erreicht, zu dem es der öffentlichen Unterstützung bedarf, um seine Ansprüche an die Öffentlichkeit in einem anderen Erscheinungsraum zur Wirkung bringen zu können. Zugleich sind Institutionen und die BenützerInnen von Institutionen darauf angewiesen, dass es Projekte wie das Ewige Archiv gibt, die sich ebenso leidenschaftlich wie andauernd den Erscheinungsräumen der Öffentlichkeit widmen, da die Institutionen, wie Archive, Bibliotheken oder Museen, in Zeiten der Austerität, der Sparmaßnahmen, diesem öffentlichen Anspruch der Dokumentation der Gegenwartsgeschichte der Stadt nicht mehr umfassend Rechnung zu tragen imstande sind. Die BenützerInnen von Institutionen können sich nicht mehr darauf verlassen, in den genannten Institutionen die öffentlichen Erscheinungsräume der Geschichte der Gegenwart auffinden zu können. Meine Argumentation zielt nicht darauf ab, dass das Atelier Peter Putz in der Mollardgasse nicht mehr der Ort sein soll, an dem jemand wie ich das Ewige Archiv entdecken kann. Meine Argumentation verfolgt eine Doppelstrategie: als künstlerisch-aktivistisches Projekt wird das Ewige Archiv vom Atelier Peter Putz getragen. Als Projekt von öffentlichem Anliegen und öffentlichem Interesse braucht das Ewige Archiv eine Institution, in dem die Einsicht in das Ewige Archiv und dessen Erforschung für viele möglich werden. Diese öffentliche Version des Ewigen Archivs benötigt ein neues Sein, einen Erscheinungsraum, in dem es den gespeicherten öffentlichen Erscheinungsraum zeigen kann. Ein Archiv, wie das Stadtarchiv, eine Bibliothek, wie die Wienbibliothek, ein Archiv, wie das Bildarchiv der Nationalbibliothek oder ein Museum, wie das Wien Museum, wären ein geeigneter öffentlicher Erscheinungsraum für das Ewige Archiv.

1) In dem im Rahmen der von der Whitechapel Gallery herausgegebenen Reihe Documents of Contemporary Art stellt der von Jens Hoffmann herausgegebene Band The Studio eine Reihe von Texten zu Studio-Practice und Post-Studio Practice vor. Wiewohl sich das Atelier als der Arbeitsort von KünstlerInnen seit den 1960er Jahren entscheidend verändert hat, ist das Atelier weder obsolet noch bedeutungslos geworden. Orte und Arbeitsweisen, die außerhalb des Ateliers im engeren Sinn liegen, haben sich vervielfacht und wurden Teil von konzeptuellen, postkonzeptuellen, politisch involvierten, sozial engagierten, relationalen, performativen, dokumentarischen und anderen künstlerischen Praxen.

begreift und einen Aktivismus des individuellen Handelns, der sich kollektiven und öffentlichen Erscheinungsformen widmet, praktiziert.

2) Die männliche Form ist mit Absicht gewählt, um der historischen Konstruiertheit von Position und Mythos Rechnung zu tragen, die mit den westlichen bürgerlichen Revolutionen im 18. Jahrhundert begonnen hat.

6) Im Unterschied zu anderen künstlerischen Positionen wie der von Dayanita Singh oder Rosangela Renno, die mit der Befragung, Appropriation oder Rezitierung von Archivmaterialien arbeiten, arbeitet Putz wie ein Archivar, der Dokumente erzeugt, wie sie in ein Archiv Eingang finden können.

3) Die Schreibweise, die die männliche, die transgender und die weibliche Form durch das Binnen I und den Unterstrich visuell in der geschriebenen Sprache ausdrückt, wurde mit Absicht gewählt, um der historischen Entwicklung von Aktivismus aus der Position von Kämpfen um die Durchsetzung von Rechten von unterschiedlichen Subjektpositionen Rechnung zu tragen.

Literatur: Judith Butler, Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street, in: Sensible Politics. The Visual Culture of Nongovernmental Activism, eds. Meg McLagan and Yates McKee (New York: Zone Books 2012) Claire Hemmings, Why Stories Matter. The Political Grammar of Feminist Theory (Durham and London: Duke University Press 2011) Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All. Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London: Verso 2013)

Foto: © Alexander Schuh

4) Eine Reihe von Fotografien im Ewigen Archiv dokumentieren die Ereignisse des Widerstands gegen die Regierungskoalition von ÖVP und FPÖ im Jahr 2000. Die Widerstandsbewegung um die Botschaft der besorgten BürgerInnen am Rande des Heldenplatzes wurde von Peter Putz fotografisch festgehalten. In diesem Fall war er als Aktivist, der fotografiert, Teil einer kollektiven selbstorganisierten Widerstandsbewegung. Sein Aktivismus ist jedoch einer, der sich auch außerhalb kollektiv organisierter Zusammenhänge als solcher

5) Aus den vielen möglichen Beispielen der Geschichte der bildenden Kunst greife ich die folgenden heraus: Eugène Delacroix (Französische Revolution), Suzanne Lacy (Second Wave Feminism), Chto Delat (Post-1989, Verbindung von Theorie, Kunst und Aktivismus). Allen diesen Beispielen ist gemeinsam, dass sie durch eine kunsthistorische, kuratorische, sammelnde und institutionengeschichtliche (Ausstellungen, Biennalen, Triennalen, Museen) Praxis zu ihrer öffentlichen Erscheinung gebracht werden.

E. K., 2014 Elke Krasny ist Kuratorin, Kulturtheoretikerin, Stadtforscherin und Schriftstellerin. Sie ist Professorin an der Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien und im Jahr 2014 Gastprofessorin an der Technischen Universität Wien. Ihre theoretische und kuratorische Arbeit ist tief verwurzelt in sozial engagierter Arbeit und raumbezogenen Praktiken, urbaner Erkenntnislehre, postkolonialer Theorie und feministischer Geschichtsschreibung. In ihrer konzeptuell bestimmten und forschungsbasierten kuratorischen Arbeit arbeitet sie an den Schnittstellen von Kunst, Architektur, Bildung, Feminismus, Landschaft, raumbezogener Politik und Urbanismus. Sie ist bestrebt, zu Innovation und Debatten in den erwähnten Gebieten beizutragen durch die Formung von Allianzen zwischen Forschung, Lehre, kuratorischer Tätigkeit und schriftstellerischer Arbeit. www.elkekrasny.at 21

Activist Archivist Artist Photographer Elke Krasny

My first visit to the Eternal Archives took place in the spring of 2014. Had I not been contacted by Peter Putz and invited into his atelier, I would never have become aware of the existence of the Eternal Archives. Using the medium of photography, Putz ventures to capture the explosive power of the present, of urban changes at the time they make themselves visible in public space. The documents created in this manner find their way into the Eternal Archives, which are located in the artist’s atelier in the Mollardgasse in Vienna’s 6th district. For many years, Putz has been combining so-called “studio practice” with what is known as “post-studio practice”1). His atelier is Vienna, the city in which he lives and works, but also a large number of other cities and places where the paths of his life and work have led him. His atelier in the Mollardgasse provides the space for his archive. The city and its public spaces of appearance are held securely within this archive. Peter Putz works as an artist and as a photographer. Peter Putz works as an archivist and as an activist. What results from this are the Eternal Archives. In the following considerations, I will examine the ways in which these four different approaches to his work intersect: artist, photographer, archivist and activist. What interests me here in particular is the question concerning the conditions, opportunities, constraints and conflicts implied by the various ways of operating, by the various ways taking action. Furthermore, I will raise the question as to the nature of the relationship between, on the one hand, this self-imposed and self-determined artistic-activist action, and, on the other, the demands made by the public. I will begin by grappling with the notion of “acting”. In contemporary theoretical debates – my special interest here is in the contexts of feminism and art-theory – there is intense discussion of the question of agency, which I would like to translate as “capacity to act”. In the book Why Stories Matter. The Political Grammar of Feminist Theory, Claire Hemmings devotes a special chapter to the issue of capacity to act, agency. She points out that independence, autonomy, freedom and self-determination are understood as decisive factors in a Western construction of the notion of capacity to act. (Hemmings 2011: 205) As the author remarks, Marxist criticism of a subject-centered capacity to act, such as the criticism put forth by Kalpana Wilson, focuses on the claim that such a notion of capacity to act places the individual above the collective and contributes to the accumulation of capital by others. From a power-theory perspective, as Hemmings points out, Judith Butler has criticized the concept of capacity to act as disregarding the power that has always (co)determined action, action which, consequently, does not result solely from decisions made by the subject. My interest in artistic and activist action is directed at (capacity of) action that takes these pitfalls into account and continues nevertheless to operate in a manifest spirit of reflection. Hence, I do not conceive forms of action independently of material conditions and opportunities, independently of other acting subjects, or independently of the question of power. To act (handeln), as I understand it, means to act (agieren) with and through co-existence, co-dependence and co-implication. I use the two German terms “handeln” and “agieren” (both signifying “to act”, “to take action”) interchangeably and have introduced the word “agieren” for the additional reason that it shares the same Latin root that gave us the word “agere” and thus establishes a proximity to the English word “agency”. 22

I will now correlate the work of the artist, the photographer, the archivist and the activist with my conception of action as being characterized by co-existence, co-dependence and co-implication. Two of these identities can be expressed actively as forms of action: photographing and archiving. By way of contrast, the other two require what one might figuratively call in the present context a “helping” verb, the verb “to be”, in order to express forms of action: “to be an artist” and “to be an activist”. There is no verb “to artist”, nor is there a verb “to activist”. Given the literal, linguistic, “auxiliary” construction, both terms, artist and activist, therefore require help, in the figurative sense of the material, aesthetic, relevance-generating, political implications involved. They require support. The state of being an artist and being an activist is subsequently dependent upon the specific literal relationship to the notion of being. There is no verb that alone expresses what the artist or activist actually brings forth in terms of action. Language provides insight here. I do not use post-structuralist knowledge and the linguistic “turn” in order to pursue a deconstructivist line of reasoning by means of language, but, rather, I use this knowledge to arrive at a materialistic understanding in a social and political economy and for a critical analysis of the relationship between individual production, collective involvement, individual investment in being, public demands and institutional contexts. The knowledge gained from language points to politics, economics and ontology, which all equally require the “helping” verb “to be”. The artist and activist are dependent upon the support, the help of the verb “to be”. This verb “to be” leads us back to co-existence, to what is synchronous, to co-dependence, to what entails a mutual relationship of dependency, and to co-implication, which equally encompasses all four identities with which we are concerned here. I will now discuss the artist and the activist as identities (and myths). Historically, the identity (and myth) of artist2) has been associated with autonomy in a complex and complicated manner. In his book Anywhere or Not at all. Philosophy of Contemporary Art, Peter Osborne examines the term “autonomy” from various perspectives. Here, I am singling out the relationship between autonomy and commodity in order to emphasize the fact that material dependence (not autonomy from material dependence – the difference is crucial) makes possible as much as it demands the autonomy of art (and of the artist as an identity operating autonomously). It is the commodification of art that makes its autonomy possible. “Autonomous art has always been for sale, as a commodity in the market. (Historically, the market is the social basis of art’s autonomy from its previous social functions.) Autonomous works of art are thus always also commodities as well – (…). Autonomy is never a given. In so far as it exists, it is the individual achievement of each work: the victory of technique (the principle of internal organization) over social conditions. Autonomy is the achievement, in each instance, of the production of a law of form.” (Osborne 2013: 166) In contrast to this Western construction of the identity and myth of the artist who combines creative work with autonomy and remains autonomous in the creative process, expressing this autonomy in his art, language use indicates rather that “to be an artist” connotes a position that is based upon the provision of support. Consequently, autonomy requires support. In my view, the fact that the German language (the same applies to English) has not developed a verb of its own to