Tapestry 2024

Tapestry 2024

Starcrossed

We went stargazing. I ran through the dewy grass, Barefoot and full of innocent wonder. You followed me not far behind, Dragging each limb like the weight would kill you.

The night sky was so beautiful lit up; Enchanting like your eyes, Sparkling like mine. Our hands brushed

Just as the swirling fires of dusk Met the midnight waves creeping from the horizon. Our fingers entwined

As darkness silently coated the world in shadow.

I professed my love to you In the subtlety of my breath, And sang your praises Through the song of my heartbeat. That frown you so religiously kept Turned up.

Such a chilling smile greeted me in the silence.

The moon gazed down upon us. Young lovers,

Enjoying the sweetness of a clear evening, Falling so hard the ground couldn’t catch us. She graced the field with her laughter, Touching all living creatures, coating them in bliss.

And so we slept

Under the guise of the cosmos’ mysterious love, Wrapped up in one another, Allowing our souls to be naked and true.

But now,

Even though the twilight has separated us, We are still connected By the light of the stars.

MargaretShelton‘24

Backstage GraceYang‘25

Dance of the Nebula-Fires

Faraway lands of the Indian subcontinent. Familiar foreign people

Draped in silk and gold, Their bells jingling with every step, Orbit a pyramid of palm fronds. A torch wrapped at the head in white, The first to catch the inferno. A shehnai starts the music, A blazing culture in every note. The flames wrap around every step, Smoke winding around the bright core, A nebula of swirling and flashing colors. Every downward swoop of the circle, Precedes each triumphant rise. The dying collapse of every stalk, A harbinger of new life. Each flicker of the dance undulating, Graceful.

A gift from the past. Tongues of fire, Giving birth to new light. Shooting stars flying into the sky. Some falling back to earth in a burst of glory. Some taking their places among the constellations. Cold fire scintillating and unreachable, Forevermore preserved in the night sky.

RebeccaWang‘26

ScholasticSilverKey

Your Fifth Eye

Open

Kaia Yalamanchili ‘24

Scholastic Merit Award

Do I Need Therapy?

Every Monday, I walk 3.5 miles to the Mayo Clinic because I can’t drive a car. Then I walk up six flights of stairs and tell myself it’s to avoid people finding out I see a shrink, but it’s really because the elevator lights look like two giant headlights getting closer and brighter until they crush the side panel of Cooper’s Mercedes, obliterating the glass windows that I swear were there a second ago … until the shards fly into his black leather seats, the airbag, his horror-struck face anyway. I say I can’t drive, but the truth is I could. At one point. I still have a sweet 1970 Dodge Charger collecting dust in my garage. But it hasn’t been touched for six months precisely because of what happened on June 6, 2023, at 10:27 PM. For twenty Mondays now, I’ve ended up in the painfully bright reception area of the Mayo Clinic’s Psych Ward, promptly at 8 AM. “Ended up,” because I literally could not tell you one detail about the walk to the hospital. It’s a blur, like the memory of a dream five minutes after you wake up. When I arrive each time, there is no wait period to enter Dr. Monica Evans’ office; I’ve never met another one of her patients. The only stereotypical aspect of a therapist’s office that made it into hers is the chaise lounge in the center of the room. Everything else departs from the Hollywood-manufactured office design of “allknowing therapist meets guy with PTSD embarking on an early midlife crisis.” That seems like the situation anyway.

I enter into Dr. Evans’ office for my twenty-first session and pause to let my eyes adjust to the dim lighting. The walls are painted a dark brown, and heavy curtains mask the bright Arizona sun outside. Thick, knit blankets and fabric are draped over every horizontal surface, and it takes me a moment to find the psychiatrist in the gloom. She sits behind a large oak desk with her initials inscribed on the side. “Scott, how nice to see you again,” she intones with her soft, slippery voice that seems to come from all corners of the room.

“Hey, doc,” I mumble, settling onto the dark green chaise lounge that faces away from her desk.

“I think we should start where we left off last session. You were telling me about where you and Cooper were going on the night of the 6th,” Dr. Evans says gently.

“Uh, alright,” I start, knowing how difficult it always is to tell this part. But I pause, because it’s always exactly this difficult. Every session.

“Wait a minute, doc. Isn’t this where we started last session? And … the one before … that one,” I trail off.

“This is all part of the healing process, Scott. Surely you know how important it is to become comfortable with traumatic events in order to move past them?,” she replies in a sickly sweet tone.

“Yeah, I ” Sweat was already starting to bead along my forehead, and I sat up shakily, pulling at my collar. I fidget with the Swiss army knife in the pocket of my sweatpants, a nervous habit. Sure would be funny if the doc found out her mentally unstable patient carried a knife around with him everywhere. But it’s purely sentimental. It’s the last thing Cooper gave me, back on our trip to the Alps in April. “I just thought you’d asked me that a lot. In the same way or whatever. I don’t know.”

“It’s perfectly normal to feel confused when coping with an experience like this. Sensations of paranoia, déjà vu, or--”

I interrupt her, saying emphatically, “Yes! Déjà vu, that’s exactly what it is. Because I

could swear, up until the point where I questioned it, you’ve told me to say where Cooper and I were going that night every week since I met you. In those same words. Everything’s the same, I can’t even remember how I got here from my house, I just showedup here in a trance or something and I--” I lift my face from my hands, freezing when my sightline to the floor finds Dr. Evans’ pristine black leather boots standing in front of me. I slowly look up and meet her chilling, unblinking gaze. Her lips move, but it sounds like I am underwater, miles away.

“Maybe,” she whispers, monotonic, “maybe it’s déjà vu. Maybe it’s real. Or maybe … it’s all in your head, Scott.”

Her hands start to shake, and her impassive expression falters. I can only watch in terror as her high cheekbones widen and morph into a strong jawline, stubble poking through the surface of her skin as heavy dark brows emerge, her pin-straight blond hair retreating into coarse brown curls. Her head jerks backward as bands of muscle run down the sides of her throat, erupting through the joint of her shoulder and into her arms, distorting her slight frame. And just when I think the nightmare surely can’t continue, she straightens up and faces me. But she is no longer the petite blond psychiatrist I thought I’d known for the past five months. Instead, I find myself staring at a perfect copy of myself, except the facial scars across my left side from the crash appear on my double’s right.

Nausea shoots through my torso, pain blooming across the back of my head as I fall backward onto the floor. I turn onto my stomach, burying my hands and face in the shag carpet, trying to get a grip on reality. But I recoil when the foresty scent of the carpet takes me back to the crash and the evergreen air freshener that swung from the rearview mirror as the car swerved off the road. Could it all be in my head? Impossible, because I could feel the shredded leather seat beneath me, see Cooper’s frozen expression reflected in the broken, dangling rearview mirror, and hear the high-pitched ringing of a collision’s aftermath.

I lean forward, pressing my forehead against the oak-paneled dashboard of the Mercedes, trying to breathe normally. I squint at the smooth oaken boards but scramble away when I make out the shrink’s initials staring back at me. Everything begins to spin until the heavy blankets of the psychiatrist’s office return, spiraling together behind the two letters dominating my vision. Monica Evans, M.E., M.E., M.E., ME, me, it’s allme, it’s been me the whole time. I trip on the psychiatrist’s stretched, torn black leather boots as I try to stand, getting tangled in the blankets spread over the couch and bookcase, knocking over lamps and end tables in a mad dash toward the safety of the reception area behind the door. I stumble through the doorway and hear the handle slam into the wall from the force of my desperate escape. But I don’t find the white light of the waiting room’s LEDs. Instead, I’m greeted by my own kitchen, counters covered with dirty dishes and empty beer cans. Feeling dizzy and sick, I turn back around to see the office I just left. Collapsing against the doorframe, I find it replaced by my darkened bedroom, sheets and books strewn across the floor, curtains yanked from their hooks, a broken lamp lying next to a splintered nightstand. Jagged fragments of the shattered mirror from the corner are littered across the ground. My Swiss army knife has been left on the pillow, and the letters “M, E” are carved into every visible surface: the walls, carpet, mattress, everything. I slide down the side of the door frame, blacking out before my head hits the floor that’s rushing up to meet me.

Isabelle Ferris ‘24

This Silence is Water

“Close your eyes,” the teacher says, “for our moment of silence.” And I picture two blue birds crisscrossing the vast sky. And I’m receding into the ocean. This silence is water.

Wallowing in our shallow worries, this silence presents a chance to breathe, to swallow.

As time ticks away. This silence stirs the soul. Silence is kshamai . Silence becomes sand. Crystalline. Now, we tune into the sounds of the ocean. Like waves, receding into past versions of ourselves, and rippling forwards to our future selves. Silence becomes like walking on water.

Now, this silence ignites a burning fire. We, as a class, have our eyes closed, as if in sacred prayer. Kai kai kai , chants.

“Thank you,” the teacher says. Now, class begins. Our work starts here.

ShriprabaNarayanan‘25

The View From My Goggles

Madelyn Priest ‘24

Scholastic Merit Award

Last Night I Ate a Van Gogh

Last night I ate a Van Gogh climbed over and shoved it into my mouth the canvas crumpled tasted like salt moss iron wool crunch ivory night the museum guards weren’t very pleased they came running over but slipped on the shattered glass I stood there and chewed thinking about the sunflowers my mother painted yellow as the ones I’d just eaten so who are they to decide which one is worth more? a gold frame means nothing I bet they’d both taste the same.

SophiaChen‘24

Scholastic Honorable Mention

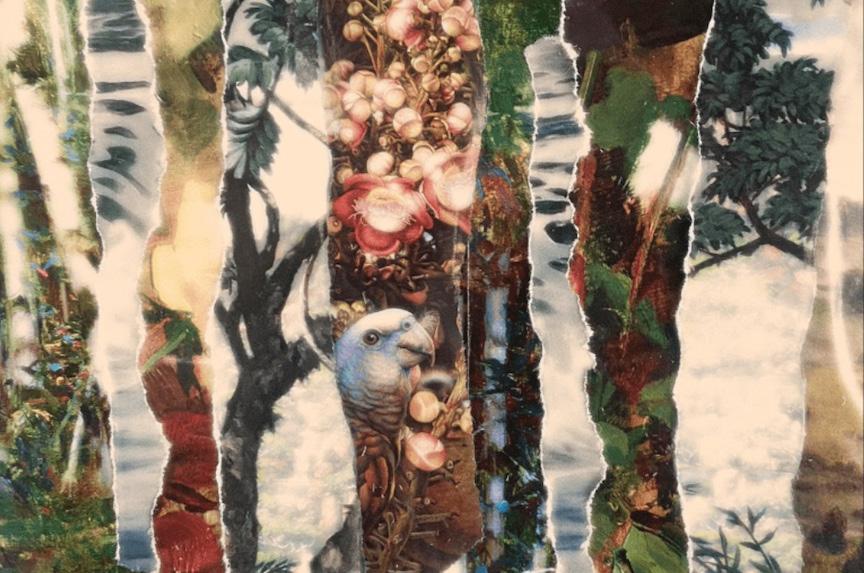

Tribute to André Derain

CarlyPolsky‘25

Scholastic Merit Award

Three and a Little More Pieces Of My Father and Me

The First Piece, Revealed to Me When I was Eight I’d been to Chinatown before, but this time, baba told me to wait in my booster seat while he bartered with the old women for their sugarcane. He brought back eight-foot-long monsters that couldn’t fit into our little 2013 Avalon’s trunk and had to be shoved diagonally between the passenger and backseat. The three weighty stalks rested on my mosquito-biteridden legs, poking into my belly when we hit a couple speed bumps on the way home. They didn’t look all that special–why did we waste a whole twenty minutes just trying to fit them in the car?

Mama was delighted. “Sugarcane,” she laughed, shaking her head in disbelief when she saw us lugging them up the driveway. There was pride mixed-in also, at the good deal we’d got them for.

He brought out our steel meat cleaver (usually reserved for ribs or tough beef, but apparently, no other knife could slice through the stalks) and labored at the wooden chopping board for half an hour, each cut scattering purpley-blue fronds onto the floor. I gathered them into my arms and played dress up. We worked in tandem; my hourly pay arrived in the form of a small mountain of sugarcane sticks set on the table.

That constituted our lunch for the day, and the usual fare of cool noodles in almond butter sauce and julienne-cut cucumbers could not compare. I crushed the fibers between my teeth, sugary juice flooding my parched throat on the most scorched day of the year.

Awholeyuanforhisbirthday.Ayuan–tenwholemaos!Hisfriendswouldn’tbelieve him.Dirt-crustedfeetpoundingdownthedustyroad,muddyfromyesterday’swarmrain. Skiddingtoahaltinfrontofthedisgruntledgrocerperchedonhiswoodenstool.Slappingthe moneytriumphantlyintohisweatheredhands;tenpurple-brownstalksboundinroughstring shovedintohisarmsinexchange.

Rinsingoffinaclearbrook,sweepinganyremnantsofgrimedownstream,beating thestubborncaneagainstacleanrock.Smallfibersgettingstuckinhisteeth,butworthit,so worthitwithjuicerunningdownhisarmsandpealsofboyishlaughterringingoutfrom belowthetrees.Maybehe’dtakesomehometoMa,andshe’dboilitintosyrupcomewinter. Spooningstickysweetsyrupintothehotwater,sprinklingintealeaves.Lighting candlesandwritingonroughpaper,painstakinglycopyingeachforeignletterfromhis borrowedtextbooks.Teakepthimlucid.He’dhavetostayuplatetonight,andmemorizethese papers.Hecouldcatchuptohisclassmatesthisway,andmaybedobetteronthenext grammartestifhereallyputhismindtoit.Anotherhourortwo,andthenhewouldsleep.

School,thenworkonthefarm,thentendingtohisyoungersister,scoopingthesugarcanepreservesintoabowltosootheheritchythroat.Thisallhadtobeworthit.Hecouldn’t standthecrisp,leather-boundbooksthemagistrate’ssonbrandishedathim,histicketto universitypunchedinsincethedayhewasborn. Something good will happen, hepromised himself. Someday, everything will work out.

The Second Piece, Revealed to Me When I was Eleven

When I stood up from the piano bench, baba handed me a tennis racquet. Where my abilities lacked in music I made up for it on the court. I loved the sweat, the adrenaline, the satisfying smack of yellow balls, and the sound of heavy shoes skidding on worn concrete. Baba instituted the morning regimen: at least one sweet banana with my breakfast every morning. Whole, sliced, smeared with peanut butter (or Nutella for the more sinful), caramelized in the pan, baked into breads if they were past ripe. It didn’t matter how I ate them; as long as I met my daily quota, he was satisfied.

I secretly abhorred the bunches of fruit that proudly crowned our kitchen island after every Costco run, but they appeared with wheat bread and orange slices every morning without fail, and I knew better than to complain. I ate them begrudgingly, full of stickiness and peanut butter when I stepped onto the bus with the rest of the fifth graders.

Twelveyearsold,playingcatchwithhisfriends,when mama called them inside. A flash ofdisappointment–hehadbeenabouttowin,asusual,armssnappingforwardsand hurlingtherubberballhighabovethetreetops–butsteppedinsidethefarmhouse nonetheless.Crowdingaroundthesmallkitchentable,aforeignsightgreetingthemonaplate. Shecutitopenwiththeknifethatalwaysseemedtodullalittletooquickly,paleyellowmeat andasprinklingofdirt-coloredseedssplittingopenfromthevibrantpeel.“FromAmerica,” shesaidsoftly,dicingthepreciousfruitintosmallpieces.Sosweet,impossiblysweeterthan thespoonfulofbrownsugarhe’dpurloinedlastweekwhen mama wasn’tpayingattention.She wouldn’ttellthemhowmuchshe’dpaidforit,orevenwhereshegotitfrom.Itwasa banana though. Bah-nah-nah,theyrepeatedtoeachotherforweeksafter,rollingthestrangeEnglish fromtheirtongues.

Twentyyearsold,crossingintothesupermarketinanewcitywheretherichkidswent; seeinganever-endinglineofgoldenyellowsittingacrossfromtheapples.Puttingabunchinto theplasticshoppingbasket–alittlegreen,buthedidn’thavethetimetocare–andhurrying hometohisroommates.Carefullyunwrappingmemoriesandtakingasatisfiedbite,but missing mama and the chickens all the same.

The Third Piece, Revealed to Me When I was Thirteen

Eggs were the first thing I was ever trusted enough to cook. On the weekends I tried new recipes, balancing carefully on chairs to reach long-forgotten spices in our dusty cabinet. Fluffy omelets with runny yolk in the middle, unfolding on the plate like a yellow sundress with green parsley embroidery. Savory shakshuka engulfing the house in tomato-scented steam (and sometimes the smell of burnt cheese). Buttery scrambles (the secret was to leave them just a touch uncooked) spread on toast and griddle cakes. Eggs on eggs on eggs, and baba loved it. Held the pan when it was too heavy, ran out and bought cream or Old Bay or more tomato sauce at my request. The most consummate food critic could not deny the breadth of my culinary talents, and yet I could never conquer mama’s warming egg-and-tomato soup. The taste was never quite right; the broth was always a little too milky. I threw in the towel after my fifth try, but dad was never one to quit.

She instantly tasted the difference. “You put butter in the eggs,” she accused, annoyance sparking in her eyes. “Just let them be and stop using that American crap in our food!” Nothing in the house was safe. We found the Old Bay in the trash a few weeks later, and any unopened cans of marinara or alfredo were returned silently to the grocery store.

Westernization, in my parent’s homeland and on the homefront. Baba mixed stir fry with spaghetti, vegetables and rich brown sauce coating the al dente noodles. Mama refused to eat lunch that day. He poured quinoa in our winter porridge, to which she made hot soy milk for a week instead. New ciabatta bread from Trader Joe’s molded while we ate white rice under her watchful eye. Silent, petty war raged within our walls, and my stomach suffered most of the casualties. I never understood how they fought so fiercely when they cooked, then ate sitting right next to each other at the dinner table, almost like nothing happened. They were always silent. Mama fumed in her chair. Baba pretended to be absorbed in his food, his chopsticks clattering just a touch too loudly on the porcelain rice bowl.

I myself was complicit in sustaining our mute condition. There were attempts at conversation, at filling the void with cheerful stories from school, but my throat always closed up before I got to the interesting parts.

Orangeyolkspillingoutontothepearlygrains,adashofsoysauce,stirringthe tamagoviolentlywithhischopsticks.Notime,notimeatall,andheshouldn’twasteiton breakfastexceptforthefactthathecouldn’tignorethehungerclawingathisbellyanylonger. Thesunbeatingtoobrightlythroughthethickglass,hisrumpledshirtrefractinglightacross thecrampedstudyroom.Sweepingthemessofpapersandequationsintohisschoolbag, shovelingriceintohismouth,sprintingalongthewalkwaystogettoclass.Hisclass.Topofhis class,topofhisschool,clawinghiswayupthelegsofthebigwigs,slavingawayatacomputer for the rest of his life. How else would he make it to America?

America…surelyitwouldn’tbesoscary.HelearnedEnglishfromthecartoons,hecould usehisdegreeifheevergraduated,andthemoneywouldbeextraordinary.Justaslongashe madeitpastanotherclass,anotherexam,anotherpaper.

Thesundippingoverskyscrapersthatevening,lettingthepalemoontakeoveronthe nightshift.Eggsagain,crackedoverrice,hurriedlymixedwithsavoryshoyu.Nocandlesnow, justalamptoturnonandatickingclocktokeeptrackofoutofthecornerofhiseye.Tongue incheekandscribblingmadlyonthepagesofhistextbook. What a fine engineer, hescoffed tohimself, with no machine or computer to test my knowledge. Buthereadon.Sleepwasnot aquestionbutanecessity,andyethiseyesmovedtothenextpage.Wordsslippingpasthis recollectionasthesunawokeoncemore.Crackinganothereggoveranotherbowlofriceand pouringanotherhelpingofsoysauceontopandshovinganotherspoonfulintohismouth…

One More Piece That I Realized On My Own

There’s a special kind of peace on Saturday mornings after all my assignments are turned in for the week. Baba and I are usually the first ones up. We cook together, one head crowned with strong black hair and the other beginning to bald. A pink baby face working alongside one with crow’s feet. We toast slices of bread, blend three ripe bananas with whole milk and

just a little honey. Brew black coffee, the decade-old machine still functioning by some miracle. Churn out a heap of fried eggs in chili oil.

As I have grown older, I’ve come to cherish these early mornings, when we can both smile at the bluejays quarreling in the backyard and stop to feed the dog some table scraps. It has been on these mornings only that my father has told me stories of his life before he immigrated to America.

I have never had to transcribe borrowed textbooks in a foreign language by candlelight or fight tooth and nail just to get an education. I saw the vivid colors of the produce section as soon as I was old enough to walk. But my father and I, we bridge the gap in our formative years through the food that we share–the sugarcane I’ve come to love, the variations of bananas that I have yet to start liking, and each new and old way I’ve learned to cook eggs. Each sprinkle of spice, each sizzle on our stove, is my continuation of the narrative that he began.

BriannaYang‘25

ScholasticGoldKey

DePaul’s Blue Book Finalist

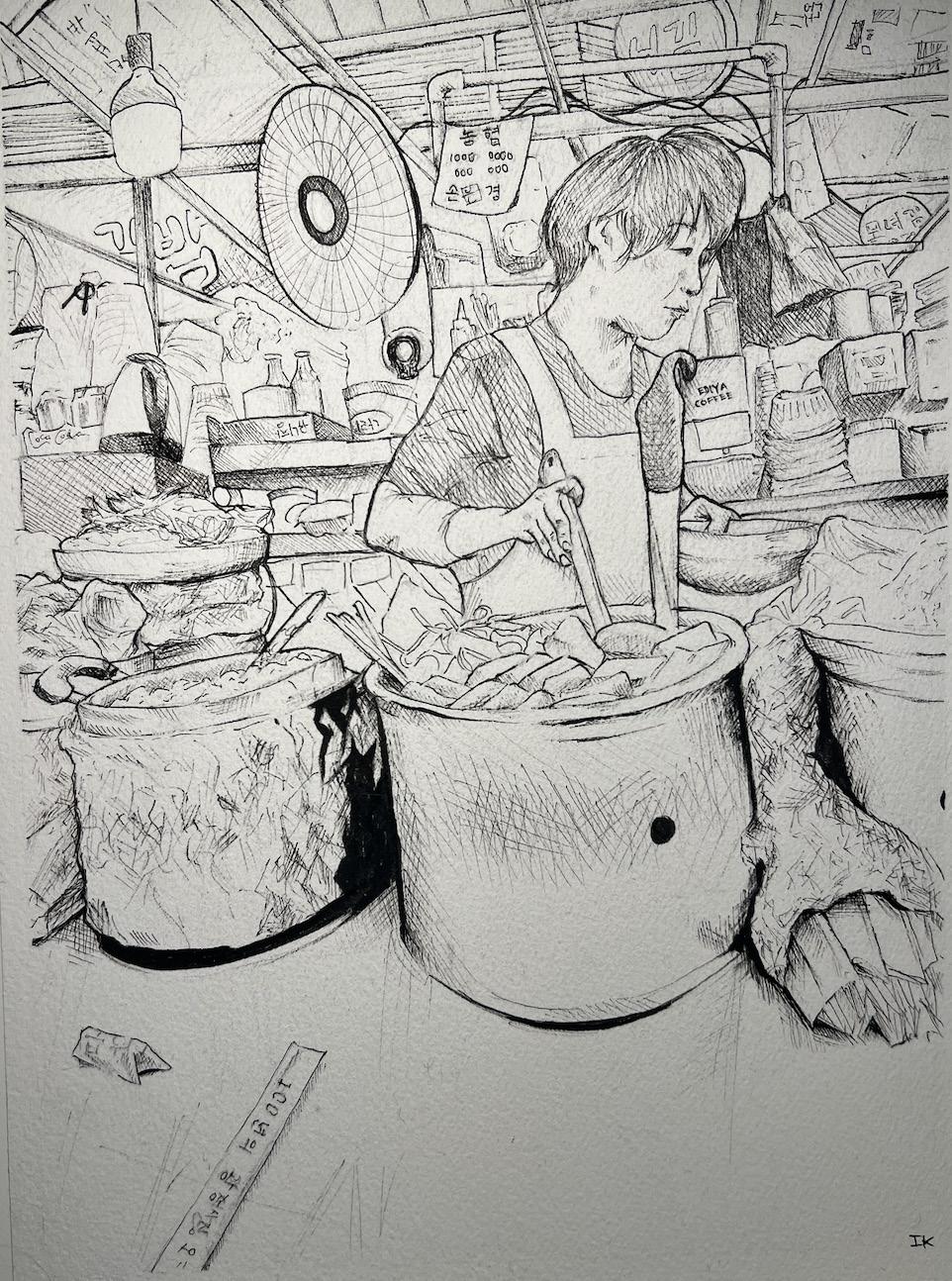

Moreplease

Isabelle Kim ‘27 Scholastic Gold Key

Eyes on Me

A park on a sunny day.

Trying to escape the heat, Resting below a tall tree With prickly grass below.

A picnic with friends, Dressed in clothes that Cling to my skin. Trying To fill unspoken expectations.

The sun draping over The branches, light pouring Through the spaces Between the leaves.

Fragments of light Blind me briefly.

It tries to break Through the darkness And reveal the parts That don’t want to be seen.

SylvChen‘24

Waldesrauschen Grace Chen ‘24

Veil of Smoke

I remember when smoke mystified me: An offering to God above, floating high. How its perfumed scent danced around.

I remember when smoke mystified me: An escape from the makers Of discord in my home.

As I aged, smoke clouded me In purity, in vanity, in indulgence And with each breath

I pleased Him: ................................I felt gratified: He gave me gold: ...........................An orange-white stick I waved it around, .........................Filled my lungs with smoke Smoke rose to heaven: .................I fell to my knees as I Touched His face: ..........................Coughed, choked, in fear–The Lord, I honored him ...........Worried I’d succumb: His grace and glory .......................I kept praying to live Above all my wishes .....................To clear my lungs of Him. ..................................................Sin.

Smoke diffused between my two realities, Each inescapable: my two homes: The house of God, and suburbia.

I remember when I saw smoke in my home: Candles lit around, all souls rising above… The bravest soul was my own.

I remember when I saw smoke in my home: I dropped my lifeline on the floor, I consumed its smoke, but now it consumed me.

I saw God. .......................................I saw my parents. I looked down.................................I cried in their arms. His hands shunned me. ...............She spoke in flames.

I longed for clearer skies.

Ethan Flores ‘26

Swiss Alps

Andres Ramos ‘26

Scholastic Merit Award

A Moment in Time Dress

Ellie DiCarlo ‘24

Scholastic Merit Award

We’re All Mad Here, Why Not Act Like It?

Imagine this: Oxford in the 1910s. Brilliant yet dour scholars from all corners of the world (but mostly England) learning and growing in their talents. The air is rife with competition. Amongst this volatile environment, a party is held for the boys of Oxford. Standard party, standard dress code. That is, until the students JRR Tolkien and CS Lewis show up–in polar bear costumes.

These two men would go on to write some of the most popular fantasy-fiction books of the modern day, the ChroniclesofNarniaand TheLordoftheFreaking Rings, yet here they were in bear suits at a non-costume party. And this wasn’t the only situation I’d read of weird shenanigans involving the two authors. These friends, war veterans and distinguished gentlemen, were also known for pulling some of the most juvenile pranks I’d ever heard of.

JRR Tolkien, particularly, convinced his students that Leprechauns existed, drove like a maniac on the daily, and chased his neighbors in full viking gear. The polar bear prank, however, always stuck with me because he was with his close friend. I always loved the two authors as a kid, but when I read about their daily lives–almost as exciting as the stories they wrote–I fell in love again. It was just so weird! So funky! I wanted to do that! And that’s when my belief in wearing polar bear costumes to dinner parties began.

No, I don’t actually want to go to every party dressed as a polar bear. (One time would suffice.) I want to live every day without fear. Because, contrary to popular belief, I do care what other people think of me.

I do embarrassing stuff. Constantly. Zone out while I’m supposed to be listening to instructions, talk too long, laugh too loud, trip over thin air, or get excited about (God forbid) school. Ogh, I just threw up a little in my mouth. Passion? Excitement? It’s hard enoughgetting up in the morning with work and sports and friends and enemies and frenemies and . . . Sometimes I just want to shut myself off and remain indifferent so I don’t get hurt. But every time I try to, I remember my mother telling me to act as if I didn’t care about what others thought of me, even if I really did care.

Last year, I had a tough time adjusting to Archmere. I met many wonderful people, but I was too afraid to express my often anxious, negative, or downright strange emotions for fear of pushing people away. One of the only places where I could relax was The Patio. And it’s all because I decided to finally bite the bullet, donning my metaphorical bear costume. You’ll see. In early October, my friend Yedda brought me to The Patio to meet another girl, Arlene. We found her playing enchantingly on the piano. Her playing was so lovely that I felt the urge to dance–but who was I kidding! That would be weird. I’d just met the girl, and I couldn’t even dance. But then I thought of CS Lewis and JRR Tolkien in their bear costumes. What if, they too, felt a bit anxious that no one would find their stunt funny? Yet they still wore that bear costume, loud and proud, like nothing worried them. And so I danced–terribly, clumsily–but still. Light from the stained glass window dappled into the clearing below, while music weaved between marble pillars. There was something magical about the building that day.

Later on, Arlene told me that she thought I was crazy when we first met. And yet, she’s now one of my best friends at Archmere. I felt comfort and joy from being unapologetically weird. I could be weird withsomeone. So, I entreat you: put on your own bear costume in life. Live like no one’s watching even if you see and fear the stares. Then maybe one day you won’t have to act when you say you don’t care what the haters think.

Anne-Cécile(CC)Kittila‘26

But I Am Still Proud

I am Different, and I am Proud

My skin doesn’t glow under the moonlight like the rest

But I am still Proud

I glisten in the sun, blessed by Ra

My hair doesn’t fall straight or wavy

But I am still Proud

It fluffs up to form a halo

Not bound by earthly gravity

I am Different

I stand out

I get looks

But I am still Proud

I am different from everyone else, but I work to shine brighter I stand out from everyone else, but I make all the difference I get looks from everyone else, but I embrace the spotlight

All these differences may make another crumble

But not me

I will continue to stand Proud

Madison Gates ‘27

What do you see?

Cassius Hearne ‘26 ScholasticGoldKey

Jeánne, not Jean

My first name is not the most significant part of my name. For me, the most unique part is my middle name, which is Jeánne. It’s pronounced like John, but I was so embarrassed by it that I just went by Bridget Jean. I hated how masculine it sounded, and wanted a middle name like the other girls in my class. Rose, Elizabeth, Grace. I wanted a name like that. Instead, I was stuck with a middle name made for a boy. My mom said it fit me. She said my middle name made me sound tough.

My dad often described me as “a little rough around the edges.” I was loud, brash, and spoke exactly what I was thinking. Growing up with two brothers meant I developed a loud mouth. I got the bar of soap in my mouth far more than my siblings. When my brothers and I argued, they would taunt me, yelling “John! John!” I hated it. I was meant to be a Jean, I thought. I wished I could be a soft-spoken girly girl. I felt awkward and out of place with my horribly boyish middle name and rude tendencies, but I couldn’t control my mouth. Even when I knew I should bite my tongue, I always found myself shouting, shrieking, or cackling like a hyena.

Eventually, I stopped trying to change myself. I might be a loudmouth, but I knew that I always stayed true to myself. My personality doesn’t fit certain people, and I’ve accepted that. That’s just who I am. I can’t deny that my middle name makes me unique, or that the boyish nature of it fits my loud mouth. I wasn’t meant to be a soft-spoken Jean. I was meant to be Jeánne.

BridgetMcGuire‘24

Penny For Your Thoughts

MayaGranda‘25

Scholastic Merit Award

A Shadow Over Yosemite

As the sun rose, a single car drove down a scenic road leaving a trail of dust in its wake. The dirt road was rough and bumpy, and wound through the trees like a serpent, never seeming to end. The car passed a sign saying “Welcome to Yosemite National Park,” and soon it arrived at a small dirt parking lot. There were plenty of spots open, yet the driver seemed to have trouble picking one. Eventually, he landed on a spot and the car ground to a halt.

The driver stepped out of the car and shut the door behind him, emitting a clunking noise. Lewis was a man in his early twenties: he had black hair, brown eyes, and a small, unimposing figure. After getting out of the car, he stood there for a while thinking. Looking into the distance through the thick tree line, he could make out a massive cliff face; it was picturesque and awe-inspiring, and a part of him wanted to visit its base just to see what it looked like from directly below. He closed his eyes and took a deep breath, and for a moment all of his problems faded. Then they came rushing back into his mind like rapids filling a small pool before overflowing. He walked to the back of his car, opened the trunk, and then pulled out a bloated brown backpack with his camping equipment and supplies. Tent poles poked out of one of the zippered compartments, and the form of the bag was misshapen as crammed equipment tried to escape through its walls. He shut the trunk and it made a loud thud. Lewis began walking away from his car and towards a pamphlet display holding maps of the park. He picked up a map labeled Yosemite Valley, and he began to hike in search of a camping spot.

Lewis knew that camping outside of the designated camping sites was illegal in Yosemite. He decided that camping alone was worth the risk to get the time he needed; he could handle himself around wildlife anyway. The sun had risen behind him, beating down his back, warming him, and casting his shadow in front of him. His eyes began to rest on the shadow, on its featureless face, its movements matching his own. He started walking in different ways to see how his shadow reacted. First, he tried skipping, then hopping, each walk more exaggerated than the last. After several types of walks, he began to tiptoe, almost as if he were an old cartoon trying to make his way past a guard. After doing this for a while, he tripped and fell face-first, landing in a muddy patch of dirt. He slowly got to his feet, cleaned himself off, and after a moment began to laugh aloud to himself.

Lewis then turned his attention back to finding a camping spot and set off in the direction of the cliff face he saw earlier. He passed through several locations, all of which could have suited his needs, but none struck him as being particularly suited for contemplation. First, he passed a small clearing in the woods. The spot was cozy and quiet. He was thinking about settling for it anyway when he saw someone walking in the distance. He realized suddenly that the spot wasn’t secluded enough and he would likely get caught before he even got his tent up. He thought about approaching the man, maybe even striking up a conversation with him, but decided against it. He was taking this trip to get away from people and he wasn’t about to compromise that for small talk. He looked down at his shadow again. By now it had begun to scrunch up in front of him, compressed as the sun got closer to the center of the sky. It looked as if it were being drained of its life, and had deflated like a balloon as a result. Lewis slowed down as he approached a pond. It was a small thing with cattails poking through the surface of the water and tall grass growing around it. A side of the pond was well-shaded from the sun’s rays, and in addition, the cicadas’ buzzing was surprisingly

soothing. Just as he began to believe that this might be the perfect camping spot, a mosquito flew into his eye and it began to twitch. He swatted at the mosquito in a desperate attempt for revenge, missing. As he stood there trying to clean his eye, another mosquito took advantage of the situation and landed on his arm and bit him before getting swatted off. Lewis quickly began to jog away from the pond, his shadow following suit.

Soon he was nearing the cliff face. He looked up to see the sun, which was now partially obscured by the cliff face, casting a massive wave of darkness in front of him only a hundred or so steps away. When he was only a few steps away from crossing the threshold into the cliff’s shadow, he heard the noise of footsteps. The noise was indistinct, far off at first, but it quickly closed the gap with inhuman speed. By the time Lewis even registered the footsteps, they had already stopped, only inches behind him. He jolted, and for a moment stood still, frozen in fear. He forced himself and sharply turned to face the source but when he looked back he only discovered a shadow which was sprawled out on a large tree behind him. It was looming over him, towering, emaciated, with long spindly fingers that came to sharp points. It seemed to stare down at him. He stared back. It certainly couldn’t be his shadow. For a shadow cast from him to even remotely resemble that thing, he would have to be twenty feet tall or the sun would have to be under the ground, which wouldn’t even cast a shadow anyway. But what could he do? For a moment it felt like he could do nothing.

Then he realized that the sun can only cast one shade of shadow, but this conjecture was reliant on the shadow being cast by the sun and not some other unearthly source. He didn’t have any other choice, though, than to hope that the shadow of the cliff would serve as a protective barrier or consume his pursuer entirely. Committing to his course of action, he quickly turned again to face the cliff face and sprinted into its shadow and then some, hoping that he would lose the thing.

To his delight, he seemed safe, completely unharmed. When he stopped, he spun around, his eyes starting on the tree where the shadow had been and then darting around for any signs of the thing. His hopes were confirmed: the shadow was gone.

He found a nice spot in the shadow of the cliff and set up camp. As Lewis began to set up his camp, he thought about leaving, giving up on this trip entirely. He realized that to do so he’d risk confronting that thing again, which was something he could not yet stomach. A part of him began to wonder, whether the shadow was really there, or whether he had merely conjured it with his mind. Perhaps there was no shadow other than his own; perhaps he was seeing things again. He continued setting up the camp, first by placing the nylon body of the tent on the ground, then with much care putting the poles, which were to be the tent’s supports, together until they had made a rough frame of the tent-to-be.

By the time the small tent was put together, it was completely dark out, and Lewis had to strain his eyes to make out what he was doing at any given time. He rifled through his backpack and made out a rectangular plastic container, his food. He pulled out the container and, without thinking, also pulled out a lantern to give him ample light in which to eat. He hadn’t eaten all day, and his stomach had been grumbling ever since the sun passed the middle of the sky. The meal was a single muffin, a piece of steak that he had made the day prior, and an assortment of other snacks to keep him busy. After he had finished, he sat there, thinking about why he had come on this trip. Then, suddenly and unprovoked, he burst into speech

and began to hold a lively conversation with himself.

“It was in no way my fault.”

“What are you talking about? Of course it was.”

“It couldn’t have been.”

The shadow–cast by the lamp lying in front of him–began to grow behind him, but he was paying attention to his words.

“But there was everything for you to do!” He said to himself sharply. “You might not be a doctor, but you knew exactly what they were doing and exactly what it was going to do to them.”

Lewis quivered at this before retorting, “Of course they were going to hurt him in the long run, yes, of course! But I had no idea that he already had high blood pressure. I told them that it was a bad idea and that he should have stopped them! That’s all I could have done!”

“What? The bare minimum to try to absolve yourself from guilt? You murdered him!”

Lewis began to tear up at this last line, before finally bursting into tears. He cried for longer than he knew and only composed himself when he was disturbed by a noise coming from behind him. For an instant, he thought he might have been found by a park ranger who overheard his argument. Would they simply bring him to the campsite where he should have been since the beginning, or would he be charged? Then he looked up and to the right to see the lantern and in an instant, he recognized his horrible blunder. He hadn’t even thought of it this entire time for some inexplicable reason. As if some force beyond comprehension had grasped into his mind and pulled all knowledge of his own oversight from him, until now. It was a particularly bright lamp, and it was illuminating his entire campsite, casting shadows of the tent, the surrounding trees whose shadows trailed off into the night, and finally of him.

He stood up, his mind racing at the terror he was about to face. He turned to see the shadow stretched across the ground, facing him from below. What truly terrified him, though, was not the shadow’s emaciated and inhuman form or even its enormous stature, but its movements. Movements which not only failed to emulate his shaking motions, but stayed almost entirely still, almost as if to simultaneously mock his lack of control over it and to assert its own dark dominance over him. Lewis began to analyze the shape of the shadow and what immediately caught his attention was the thing’s hands, or more specifically his fingers, which stretched out to an abnormal degree. The thing then cocked its head as if to examine Lewis. Then it put its taloned hand up to the dirt and began to push its way up through the soil. Lewis hastily shut the lantern off and turned back, expecting to be rid of the thing again. Instead, its horrible black-taloned hand had already made its way to the surface and despite Lewis’ efforts, the shadowy creature proceeded to pull the rest of itself up from the ground. Lewis stood there, compelled by an unusual mix of awe, terror, and a sense of culpability. The shadow now stood before him, towering in stature. It was as emaciated and terrifying as it had been back when it was chained to the surface of the tree trunk, but now its chains had been loosened and it had taken form in this world. The shadow was no less than twelve feet tall. Its fingers were foot-long claws that came to razor-sharp tips. Instead of feet, its shadowy legs ended in stumps. It was made of a black, solid, yet ever-shifting substance that made it unclear whether the thing could be truly interacted with or whether you would simply pass through its form. A thin layer of black mist outlined its figure, which rolled down its body,

pooling beneath it, obscuring the very ground on which it stood. The shadow, whose face was obscured in the dark, stepped closer to Lewis, leaving trails of its black mist in its wake. It looked down at Lewis to reveal its featureless face before beginning to rattle and letting out an ear-piercing screech, somehow, from a mouth or orifice that didn’t exist. The screech brought Lewis to his knees. He was drained and shaken to the core; there was no covering up this shadow any longer, no way to hide it from himself or others. He couldn’t run, he had expended his options and his resolve. With what little energy he had left, he looked up one last time to face the monster he had made before he finally closed his eyes.

NathanOristaglio‘24

Isolated

Kaia Yalamanchili ‘24

Scholastic Merit Award

Nocturne No. 2

Caroline Wiig ‘24

definition essay: piano

After Grace Chen ‘24

I didn’t know what a piano was until I saw grace play one for the first time.

sure, I’d seen them before— admired them, even—but back then a piano was just the curve of the lid stretching up into the sky; the slanting array of strings; the smooth brass pedals: inanimate.

then grace came and it became a living thing. she tells a thousand stories without once opening her mouth, plays every character seamlessly. she’s coiled rapture, fingers poised, crackling flames in the way her hands find every note. she breathes and the music breathes with her.

a piano’s not a piano unless grace plays it: she is everywhere at once, an exercise in divinity, crafting an awe so great I often look back and wonder how I never saw it before.

SophiaChen‘24

Ode to the Internet

I could have lived my whole life not knowing that crows bring families trinkets to show love or something like it; the kind that animals feel which we may never understand or need to. There is something marvelous in knowing that there are uncountable hours of footage made by people tearing the guts out of old buildings and replacing them with something beautiful, or wandering through derelict places because ruins can be beautiful, too.

Parents film kids crying to discover bacon is cuddly pink pigs with a raw astonishment that adults have forgotten and pledging change.

On the internet

Abandoned puppies and lonely senior dogs get snatched up in warm blankets: given a future of comfort and care in apology for a broken past. Poems that might never be heard outside of local slams find their way into classrooms or bedrooms and the ears of that one person who needs to hear those words at that exact moment.

Ordinary people take famous songs and reinvent them in stairways and corners of kitchens and cars in ways that make the people who wrote them listen and be amazed.

On the internet

We discover that mother dogs adopt orphaned kittens. Strangers band together to rescue a duckling that fell through a grate. Hard-won trust brings wild creatures back to the same human again and again over countless miles. Millions of people stream the same story dance the same dance watch the same show laugh at the same meme learn the same lesson in a free online class that used to be locked behind ivy-covered walls, inaccessible. The world can be sad and terrible; proof of that is on the internet, too. But painted on a bridge that shares a name with a battle and has a history of both Instagrammable photos and tragic sighs an image that has pumped through online veins: a girl with a heart-shaped balloon and the words thereisalwayshope.

Ms.LaurenWalton,Faculty

Swarm

The rickety bright-yellow school bus flew down the shaded gravel road. Its passengers tossed around like a ball around a schoolyard. The July afternoon produced a suffocating humidity paired with an unrelenting heat that made the campers restless. Tomás stared out the window of the bus and watched the dense forests of West Virginia’s backcountry presenting their intense green foliage and verdant grottos pass by. Beside him, Wendy was rattling off facts about various insects found in the region from her compendium of everything creepy and crawly. Tomás was deathly afraid of anything that happened to have a segmented body and more than four legs. However, he tolerated Wendy’s fascination with such creatures as she was one of his only friends at school.

Despite constant protest, Tomás’ parents forced him to embark on this grand expedition which was his school’s annual campout. Due to his aversion to insects, Tomás tended to avoid going out, leading to his lack of friends and social life. His parents saw the campout to the mountains of West Virginia as an opportunity for him to get out of the house and make some friends. Tomás just hoped they were not the ones with thoraxes and kaleidoscope eyes. Eventually, Tomás drifted into a dreamless sleep.

He was jolted awake by the bus screeching to a dramatic stop. He adjusted his glasses and looked out at the shaded path to the campsite. Tomás gathered his things and steeled himself for the week to come. As he exited the bus, he was hit by a sickly sweet scent composed of honeysuckle and dead leaves. The air was thick with humidity and it hummed with the buzz of cicadas.

The first few days were relatively uneventful, however, the heat was unrelenting and the daily temperatures were increasing. The campers were scheduled to go on a backpacking hike through the mountains on the second to last day of camp.

When Tomás awoke the morning of the hike, he felt the hot, damp air on his skin. A wicked wind blew through the forest providing some respite from the heat. However, it was odd as there had not been an ounce of wind the days prior. The forest also seemed to be disturbed with the frantic calls of birds and other critters echoing between the trees. Tomás gathered his backpack and ran to join Wendy and the other campers.

Without much delay, the group set off into the emerald expanse of forest. After a while of walking, Tomás noticed that his shoelace was untied, even though he swore he tied an extra-tight triple-knot. He knew that the group would move without him so he quickly tied his shoe.

Tomás stood up from tying his shoe to see that the group had moved on without him. He quickly gathered his bag and tried to catch up. Tomás walked for a solid thirty minutes without seeing a trace of his fellow campers. He soon arrived at a divergence in the trail. Off to his left was a clearing, a wide ellipse devoid of any vegetation. Intrigued, he ventured into the clearing. As soon as he stepped in it, the noise of the forest vanished. He could no longer hear the songs of birds, trees swaying in the breeze, or the endless drone of cicadas. After a few minutes, Tomás could hear a near-silent rumble as if the earth was trembling. He could feel what felt like millions of eyes on him. A strange force compelled him to venture into the center of the ellipse. It was as if gravity was increasing on just him. Suddenly, Mr. Aranea burst out from the tree line, his figure distorted and grotesque. His face was twisting as his eyes grew big

and inky black. Large, hairy arms burst from his shirt, revealing a segmented body with a large abdomen. Tomás gazed upon the man-sized spider as it emerged from its cocoon of cotton and nylon. Suddenly, Tomás felt a tickle around his ankles. He looked down to see a swarm of insects with their jet-black, chitinous shells emerging from the ground by the thousands. What was once dirt was a sea of insects of every variety. They scrambled up Tomás, whose resistance was futile. As he gasped for breath, his glasses fell into the sea of black. The bugs reached his face and fully consumed him. In the moments following, he expected the pain of thousands of insects biting into his skin, however, he felt the opposite. A wave of ecstasy washed over him as he felt his mind and body become one with the swarm, until he felt nothing.

JustinFlenner‘24

Omniscient Flower

I look down At the delicate daisy Pinched between my thumb and forefinger.

Each petal, Such a pure white. The silky feeling lingering on my fingers

As I rip each petal, Trying not to damage it more than I have. My fate becomes clearer:

He loves me, He loves me not. I repeat.

Four petals left. The flower is losing its beauty, As if it already knows the truth:

He loves me not. The last of the petals Is ripped from the stem.

I could cry, Or I could pick another flower, And try my luck again,

But I chose to believe the flower, Because nature knows What the heart does not.

EllaHarshyne‘24

Forgive Me, Bee

A bee passed through my open window Just as the sun began to rise, The window –Cracked open the night before To hear the soft falling of the rain.

The bumble bee large and plump, Flew into my cream curtains

His frantic whirring –Jolted me awake.

Fearfully I leapt aside, Covers falling quickly To distance myself –From his mighty buzz.

I considered getting closer, Opening the window wider Hoping a gust would pull him out –Sparing him from our actions.

Fearful of a sting I knew would never come I called my mother –To shoo him out.

But the pouring rain, And the maze of curtains

Tore the chance of freedom –From his tiny hands.

The world of my design Caused his untimely death As it forced her hand –To kill him.

I mourn for this bee, for he did no harm Nor could he do any –Caught, by circumstance alone.

Innocent as a child Murdered by our fears, Oh bee!

Absolve me –Of my foolish actions.

Victoria Eastment ‘24

Finding Claraty

When you want to order egg whites in Spanish when you’re at a resort in Cancun? You order huevos claros . When you substitute the O for an A, you get my name. Yep, Clara means clear and light in Spanish. In Latin, it means clear and bright. Clear doesn’t just mean transparent in this sense, but also understandable and certain. It’s funny that my name is associated with the things we consider bright and happy when I’m rather pessimistic. I was named after my great-grandmother Clara. I don’t know that much about her other than what my mom has told me. She was a sweet woman who never had a harsh word to say about anybody. She actually took care of my aunts for most of their childhood and she always had people over at her house. Clara was someone who was always there for my mom, providing emotional support. The name Clara is positive and happy, and I would classify myself as chronically sarcastic. When I think of Clara, I picture gentle rolling waves and the soft movement of the leaves on a willow tree. I, on the other hand, am a tad more chaotic. My mom wanted me to be as sweet and kind as Clara. I can’t say I’ve exactly succeeded in fulfilling that wish.

Clara, my great-grandmother, was a Jehovah’s Witness. When I first learned this I was practically aghast. This religion hasn’t had the best reputation and in my eyes, that fact was a bit disconcerting. I was happy to find that no, she wasn’t knocking on people’s doors all day to tell them about God. However, she was steadfast in her beliefs and she didn’t compromise them for anyone. In fact, she died for her beliefs, refusing to undergo a life-saving procedure because of her religion. Honestly, I don’t know if I would have had the strength to make that decision. If I gain anything from her name, I hope it’s the ability to stay true to myself no matter what others around me have to say.

Sometimes it feels impossible to live up to Clara.

Whether it is pronunciation or spelling people will find a way to mess up my name, and I feel like maybe there’s a reason. My mother purposely gave me a name that she thought was easy to spell and say. I’m out here every day proving that theory wrong. I’ve been called Claire, Carlo, Carla, Clairo, Kaia and Ciara. Despite my innate Americanness, my name has been pronounced in a British accent by other American people. Each time my name is butchered my exasperation grows.

My nicknames aren’t much better. Some of them I love and others just don’t fit me anymore. My family calls me Skita, Ritha, and Claritha. I like those nicknames because they come from a place of love. My aunt calls me Claritha and since we live far away from each other, it’s always nice to hear that nickname in person. The unfortunate nickname I got in middle school was Clara Beara, which was eventually shortened to Beara. I don’t hate this nickname, but I don’t resonate with it either. In fact, the name Beara and all that it represents feels like a completely different person. Back in middle school, I wasn’t as mature and my behavior definitely reflected that. I wasn’t just walking around being a terrible person, but I let other people’s views influence my own. Now, as a senior, I feel confident in my own beliefs and how I want to grow as a person. So yes, Beara doesn’t fit anymore. Maybe I’m slowly growing into the name Clara, learning to be a good person in my own way, even if I’m not as sugary sweet as my great-grandmother.

ClaraKorley‘24

Rose-Tinted Glasses

I.

He flips a page as you sit and watch. Crayon clutched in your fingertips, bright red wax melting slowly down your palm, stark against white knuckles. You wonder if it’ll ever get cold again. The man across from you, tall in stature and heavy in voice promised to bring in a fan, but the breakfast room is too small to fit one. You don’t care; you love it in here. The pretty pink roses scattered across the wallpaper make you feel like a princess.

His newspaper is the one without the funny faces you giggle at. To cheer him up, you push your drawing towards him. You sit on the edge of your seat, feet barely grazing the wooden floor, waiting till he looks towards you and your masterpiece. The newspaper must be really interesting today because your father doesn’t look up until long after you’ve busied yourself drawing more flowers for him to enjoy.

II.

She sits in your seat when you come home from school this fall, using your makeup, wearig your top. She doesn’t look up when you comment on the quiet fan, the new table without any wobbly legs, the fresh coat of gray paint.

Her cheekbones are more defined, she’s lost weight since last time. When your father looks up, he only glances at her.

Wounds still sensitive from past fights threaten to dig into you like thorns. She doesn’t know why you care so much. You think your sister doesn’t know how good she has it, but she will; you know she will.

III.

He pokes at his plate from across the table. Eggs, scrambled with cottage cheese, just how he likes them. Scrunches his nose, picks up his phone. The kitchen with him is bigger, and the legs of the table don’t wobble so much. You glance at your newest addition: messy blotches of roses painted across the wall.

You’ve spilled your guts on a porcelain platter for him. Yet he doesn’t eat a bite. He tolerates the letters of love you leave on his bedside, remains still when you kiss his forehead. But last week you found a note in the bathroom trash, and yesterday he winced away from your touch.

Any minute now, he’ll take a bite, he’ll write back. Any minute, your husband will wake up. And so you remain seated; you watch, you wait.

Rose-tintedglassesdrivethemselvesdeeperintoyourskull.

Elisabeth Small ‘25

Two Figurines on a Windowsill

Two figurines on a windowsill

In a rustic old cottage overlooking a hill. It was just you and me and we were just inches tall And our world was the window, the floor, and the wall.

I’ll admit I had believed since long before That beyond us in the world, there wasn’t much more. You were the only other being I could see –A little bit bigger and shinier than me.

For a long time we sat on the sill high and dry With nothing to do but just stare at the sky. Sometimes we’d see a plane vanish into a cloud And wonder what clouds felt like or if planes made sound.

You asked what I would give to fly like a plane, And I answered such fantasies were purely insane. But this freedom became the only thing you’d talk about, And you dreamt of a world where we could find a way out.

You spoke and I clung to every word you said. All of your grand ideas infested my head, ’Cause I had known all along you could never be wrong. I peered out the window to where we could belong.

But if we got out, where would we go?

Could we follow a leprechaun to the end of the rainbow? Or perhaps get a boat and spend our days at sea? Maybe just hide in a hole beneath a tree?

You came up with a plan, even with no destination, And I knew this was the one chance to change our situation. I thought to myself, “This is where we begin,” And you knew from the look in my eyes, I was in.

With all of our strength, we raised the windowpane. I tumbled to the grass, and for the first time, felt rain. But I looked behind me as I bounced off the hill And the window slammed shut with you still on its sill.

I stared at the window in shock and despair As raindrops and wet leaves swirled through the air. Here I was with the freedom you had dreamed about, But I knew from the look in your eyes, you were out.

You looked away from the window and I knew we’d both lost. Suddenly you appeared so different through the frost. Only from there could I see the cracks in your shell And I realized you were not that shiny as well.

I had known deep down it would only be me. Nothing we could go through was any guarantee. I still picture you there when I see windows on my own; One figurine in the world all alone.

CaileighCrane‘25

Filter Feeder Jar

Anastasia ‘26

Scholastic Merit Award

Isabella

Scholastic

Dying to See the Ducks

They say that blood is thicker than water. But it never seemed thick enough to connect our family. We’re split across the Pacific Ocean and only connect every other summer via the $5000.00 plane ticket.

The summer of third grade was the first time I visited Dad’s hometown. Until then, every visit was to my mom’s side of the family in the south of China, near Hong Kong. A few years before, I visited Dà Bó (my paternal uncle) who lived in Beijing. Before third grade, I had no idea that Dad hadn’t grown up in Beijing after all.

That was when I found out that my great-grandmother was alive. To be honest, I had little knowledge about my father’s side of the family. I knew my dad had a brother, who had two children. Shān Shān Jiě is my older cousin. There’s an old photo of us, and she’s hugging me at the kitchen table on my second birthday. My two-year-old self looks off into the distance, pensive thinking about the cream cake we just indulged in. In China, if you share a common surname with your cousins, you’re siblings. Since our fathers are brothers, that made us sisters. This is part of the reason why thinking about Shān Shān Jiě always feels wrong. What sisters haven’t even exchanged two memorable sentences with each other?

Dad’s hometown is located in Dōngběi, which directly translates to the Northeast of China. Liáoyáng is neither large nor highly urbanized, especially not in rural areas.

We trudged along dirt paths to reach Dad’s childhood home. There were few developed roads for taxis to travel along, and the closest form of transportation was rickety little scooter carts. I was filled with dismay as we passed what were supposed to be people’s homes. The outer walls were grayish, washed out, and dilapidated. Many were single-room shacks thrown together with the sole purpose of providing a roof over people’s heads. I crossed my fingers as we passed each one, hoping that it wasn’t where we were going. When we finally arrived at Dad’s childhood home, I was so relieved. I was relieved that there was at least something resembling a home in that patch of land. They say that your father’s hometown is your hometown too.

I remember the first time I stepped inside the building, I said out loud to my family, “Not bad!” The house was one story tall, with a total of just three rooms. The main room served as a kitchen and living room, and the other served as a bedroom. The third was for laundry. There was no bathroom in the house. Instead, there was a dank shack outside where a single ditch was dug into the ground. The house was almost the embodiment of poverty, but my dad explained that his family built the house from scratch shortly after he was born. I was suddenly in awe over the fact there was even a television or running water.

My great-grandmother was shriveled and gray-haired, yet once again I was impressed by how spry she was. She didn’t need a cane to walk and even smoked a pipe while doing chores. My sister and I were the most excited about the ducks and geese she owned on the little farm, and she once took us outside to feed them.

My sister turned and asked me, “Why don’t the ducks have noses?”

My great-grandmother, or Tài Tài as we called her, looked over and asked what my sister said.

I explained in Chinese and repeated myself since Tài Tài was deaf in one ear. After a few tries, Tài Tài explained to us that the ducks did have noses, they were the little slits on the bills.

I still remember that moment. It was no big feat, but I had just communicated in Chinese with my half-deaf, ninety-something-year-old great-grandmother who lived on a farm across the ocean from us. Maybe blood was a little thicker than water, after all.

The following day, we went to pay respects to my Yé Ye, or grandfather. I didn’t know much about him either, except that he died from lung cancer at a young age. I never met him. We walked a little through the wild foliage, past some trees, until we reached a dirt mound maybe three feet tall. Our whole family was there, including Tài Tài. On our way, we bought a stack of paper money with us, and I asked my mom what it was for.

She said, “We’re going to burn it to send your Yé Ye money in the afterlife.”

We all stood around the mound, spread the money on top, and set it on fire. Tài Tài took her wooden stick and began poking the ashes around, and she was crying. Her face had crinkled up like old paper, and I heard through sobs, “Ér Zi… (my son).” It’s gut-wrenching to watch an elderly person cry. I promised myself that my parents would never have to do the same for me. I suddenly realized how much my parents love me. No parent should have to bury their child.

My mom nudged my dad to comfort my Tài Tài, but he just stood there, blankly staring off into the distance. Looking back, I feel bad for my Yé Ye. He lived in poverty more or less his whole life and died of lung cancer before ever meeting his grandchildren. I could only wonder what my dad felt at that time.

This summer, Tài Tài passed away too. I heard it was from COVID-19, and the hospital was hesitant to try anything drastic because of her age. The whole family was on FaceTime, and the last time I saw her, she was lying in a hospital bed with a hospital feeding tube. I smiled, to let her know that I was doing okay. I thought that maybe it would give her some peace of mind. That same night, she passed away. The doctors said she wanted to go home.

My initial reaction was shock. I couldn’t believe that anyone would willingly choose to leave their only lifeline. I couldn’t believe that I would never be able to ask Tài Tài about what her life was like, or that I would never talk to her about the ducks again. I also realized that Tài Tài chose not to struggle over something that wasn’t important to her.

These days, whenever I think that things are going badly, I think of our hometown. I think about how we came from nothing. Nothing but a three-room house with no proper toilet and a single bed made of bricks, shared by cousins and siblings alike. But it’s still home. I used to think that a fulfilled life was one where you do a lot of things. You travel the world. You make a lot of money. You show your face to lots of people. The opposite of the quiet life my family led in Dōngběi. However, if Dōngběi taught me anything, it’s that I wouldn’t change “not bad” at all. I wouldn’t change the ducks, the walking, anything. My Tài Tài chose “not bad” over her life. I think that says enough.

Chloe Li ‘26

ScholasticSilverKey

I am outside your house again

I am outside your house again, snow sifting softly onto gabled roof, winter fog wreaking havoc on the streetlights, casting everything in halo.

how tiresome, all the back and forth. I am still trying to decide whether this heartache was inevitable.

it was difficult for me to accept not being able to find the right words. I tried on labels like fitting-room clothes, sleeves dragging on the floor. every word felt like a lie to get lost in.

I struggle under the surface of an iceberg. I let longing overtake me, then call it ordinary, call it frost.

oh, well— so we are without name, then. and also without shadow. what am I to do about it? one of us is the snowflake, the other a warm glove. how beautiful, the edge of your window paved with snow.

oh, how I want to call it love. this nameless thing, I keep bumping into it in the dark.

The House Atop the Hill

Sometimes I used to walk by The house atop the hill With the two dogs barking Loudly from inside, And the boys playing baseball In the large front yard, And the girls running and laughing On the long driveway, And the man waving As he got out of his car, And the smiling woman In the window. How lovely.

Then one day I walked by The house atop the hill And saw the two dogs howling Frantically from inside, And the boys whispering Nervously in the front yard, And the girls staring at the doctor Walking down the long driveway, And the man sweating Getting out of his car, And the frail looking woman In the window. How peculiar.

Now I walk by The house atop the hill With only silence Coming from inside, And no playing or laughter In the large front yard, And cars with matching flags Parked in the long driveway, And the man holding the kids With tears in his eyes, And nothing to see In the window. How tragic.

CaileighCrane‘25

Scholastic Honorable Mention

In the Valley of Aval Dalte

A mellowing man was sitting in his pine wood rocking chair, leaning forward; his elbows resting on his knees as his hands played with the scraggly, graying hairs of his beard. The man stared blankly into the faltering fire before him, which lit the unfavorable contours of his face–highlighting his sunken features and wrinkles. He heard no noise, the birds had ceased their chirping some time ago, having left the north for warmer weather. He thought of the boy, upstairs and cramped in his room–reading. Beginning to ease up, the man leaned back on the chair, causing it to commence rocking. He analyzed the room around him with critical eyes, looking ahead of himself to the stone brick fireplace holding in the flames like a gaol a prisoner, then to the cracks in the tan composite wattle and daub walls to his right, and down to the dark splintering wooden floor below him.

“Are you still living up there boy?!,” he called out.

Only silence was his response.

“I guess I should be taking that for a no?!”

He was met with silence once more.

The man put his feet to the ground–halting his rocking chair–and began to rise. He was deliberate and slow, for although he may have only been around forty in age, the hardships that building a new life in isolation required of him had begun to take their toll.

They had aged him far beyond his years: graying his hair and giving him his signature aged appearance and demeanor. Finally, he stood, hunched and feeble, and step by step pushed his way to the stairs, and then up them. After much effort, he reached the door to the boy’s room.

He knocked.

Hearing nothing for the third time the man creaked the door open and peered carefully into the room. His eyes looked into the hole the door made, beginning with the left wall where a shelf lay. The boy’s prized shelf was tall and made of a polished dark wood, its beauty barely capturable by words alone. On it, there were countless books of all kinds lined neatly yet pressed tightly against one another, cramped for space. The man’s eyes lingered on the books, cased in weathered and peeling leather, their titles displayed proudly on their spines. He read off a couple of titles in his head as he glanced over them: The World of the Southern Cities , and a particularly dense book titled Pyrem:IntredishAvanci , which the man correctly translated from the distant southern tongue in which it was written to Pyromancy: IntroductorytoAdvanced . And lastly, for a transient moment, the aging man’s eyes came to rest on one book: The Battle of Aval Dalte , which had many of its pages folded to mark key points. Then the man’s eyes came to the corner between the left and far walls where nothing other than collected dust sat. As the door continued its slow swing, the man’s eyes followed as it reached the far right corner. There sat a small bed and under its tattered covers lay the boy. Only the boy’s pale head and spindly arms were poking out from under the covers. His eyes fixed intently on the book lying in front of him, his arms clenching the thing out of sheer captivation and pressing in on the padded leather cover. He was towards the end of the book and the man could tell that the boy was reaching the climax of whatever tale to which he had

become a steadfast spectator. The boy did not look up, and the man, seeing the intensity of the boy’s focus, chose to wait until the child’s grip waned.

And slowly but surely it did. Minute by minute, as the boy’s story reached its close, his grip loosened until, after sighing out of relief and satisfaction, he finally, set his book down. The boy looked up surprisedly, seeing the man at the door.

The boy quickly solicited, “For how long have you been standing there?”

“Quite some time,” the man responded gruffly, then pausing before stating, “I didn’t wish to disturb you … seeing how absorbed you were.”

“Thank you?,” the boy replied relievedly.

“Come, I want to go on a walk.”

“I was going to start reading my next bo-”

“Come.”

With this the man began to walk towards and then carefully down the steps, listening patiently for the boy’s footsteps behind him. And the man was not disappointed–as by the time he had hobbled halfway down those stairs he could hear the swift footsteps of the boy pursuing him. Youthful, the boy quickly caught up and then slowed his pace to match that of the man, descending beside him. The man looked down at the boy.

“I’ll never understand why you stay so cramped up in that bed all the time reading,” he said with a tired yet sincere chuckle.

“I’ve never thought about it. It helps me … learn–to see things in a way that I never would have without them. See places I never would have without.”

They reached the ground floor and began towards the door

“Perhaps I don’t see much use in reading anymore, then,” the man said calmly.

“Why is that so?,” the boy asked as he opened the door, letting in a great gust of frozen air, and held it for the aging man.

The man walked out the door, his face met fresh and frozen air which softly brushed across his face, cooling it. The man looked forwards to the forest and great hill which lay at a distance in front of him: ageless snowy pines stretched out into every direction, the hoarfrost-covered grass poking through the snow of the forest’s floor. And then he turned to face the boy.

“I’ve seen all I’ve wanted to, don’t have much use for exploring anymore … ”

“How?! How could you have seen everything worth seeing? Experienced everything worth experiencing?,” the boy asked in a skeptical tone.

“I just … you’ll see when you get older. Hopefully, though, the reasons that cause you to lose interest in travel are not as unfortunate as mine,” the man grimly said as he began steadily hobbling towards the tree line which marked the beginning of their neck of the secluded woods, towards a great hill in the distance.

The boy still stood back, holding the door despite the fact that the man had passed through it and made quite some distance. “What do you mean?,” the boy half-shoutingly asked as he stood back by the door, entirely perplexed.

“I’d prefer not to speak on the matter. What I have told you of myself is all I wish to divulge. If that changes then I will tell you more, but until then try not to pry,” the man said

vexedly as he stood next to a towering ancient tree - resting his hand on its craggily brown bark.

As he did this the man closed his eyes and took a deep breath in, held it, and exhaled in relief: releasing embers of irritation. Then he turned back to the boy, still standing at the door, and playfully shouted, “Trying to sneak back into the house without me noticing, eh!?”

“Sorry…” the boy responded abashedly before running to catch up with the man.

The man took his hand off the tree and began to walk onwards, reaching the base of the hill and pausing. He let the boy catch up to him before asking, “Could you grab me that?” and pointing at a particularly straight and sturdy yet lightweight stick.

“I need something to help me up the hill,” the man continued.

The boy nodded agreeably and, fulfilling the man’s orders, went over to the well-built stick, picked it up, and carried it over to the man before offering it to him.

“Thank you … I’m not sure what I’d do without you these days–can barely bend my back anymore,” the aging man said as he took the stick and began testing its weight, getting a feel for its balance.

The boy remained silent, entirely unsure of how to respond.

With this the man–giving out a pained grunt–commenced his climb of the hill’s steep incline. The boy walked half beside the man and half behind him, unsure of whether to stand next to him to speak or to stand behind him to ensure he didn’t fall backward and hurt himself. They kept up the hill at a leaden rate, slowly weaving between the trunks of great snowcovered pines. The man ascended silently, not speaking a word, and instead was entirely focused on balancing both his pace and breath; the boy trailing behind him in silent concern.

“Are you sure you don’t need help?,” the boy asked, looking at the man with an anxiety-stricken face.

“I’m quite sure, I’d prefer to make my way on my own for as long as I can. My years may be catching up to me quickly, but I have enough strength in me yet.” the man replied in a proud albeit pained tone.

“Why are we even up this hill?,” the boy pried.

“Have you ever come this way? Looked out into the valley?”

“No, but what is there that is so important to see?”

“We’re nearly there. Have patience. Give it time and your questions will answer themselves.”

The incline at this point had begun to plateau. The man, no longer having to push himself nearly as hard to continue up the hill, began to ease up, catching his lost air with deep, full breaths. The boy trailed directly behind, the tension in his face softening as the man began to steady himself.

They tread, quietly again, through the trees and relentlessly towards their goal, which the man could see off into the distance: a point where the tree line ended, dropping off into nothingness. Seeing this, the man hastened his pace in pursuit of his object. The boy followed, but hesitantly, his head turned towards where they had come from and his eyes fixed on the house down the hill–mind set on his prized bookshelf, books lying dormant in wait for his return.

The man turned, and upon seeing the boy teased him, “What? Missing your books already? They’ll still be in your room and on your bookshelf as they always are when we get back.”

“I know… ”

The edge was near now, and the man began to slow down, looking for somewhere where he could rest his legs and sit. He saw a downed log forward and to his right–close enough to the edge to see the splendorous view but not dangerously so–and began to make his way to it. The man sat down on the leftmost side of the log methodically and with a certain hesitancy as if lowering himself into a cold lake or river.

The boy came up behind the log to the man’s right, hopping over the log and sitting quickly down beside his guide restlessly, hoping to be done with this trip as soon as possible. Instead of looking forward, the boy opted to direct his gaze downwards, towards the snow at his feet.

The man looked at the boy, and upon seeing his averted eyes shifted his own expression to that of great vexation, showing a sliver of an era long lost to time.

“Lift your head! Look forward! You’ve come this far. At least have the decency to see what brought you to see!” the man shouted in a controlled outburst, a flame the man now kept tame save for rare occasions.

The boy shivered, taken off guard by the man’s anger, for he had never experienced it before.

“Look up!” the man shouted again.

The boy complied and, doing as the man asked, raised his head.