BLOCK STREET & BUILDING

The Best of New Urbanism in Arkansas

8 Letter from the Arkansas Municipal League 10 Letter from the Editor

12 PRESERVING HISTORY

Architect Tommy Jameson’s legacy.

14 PRESERVATION IN ARKANSAS

Historic buildings are community assets.

16 TASTE AND PLACE

Destination dining successes in Clarksville, Hot Springs and Lonoke.

20 HOUSING REPORT

Fayetteville considers zoning changes, permit-ready building design program.

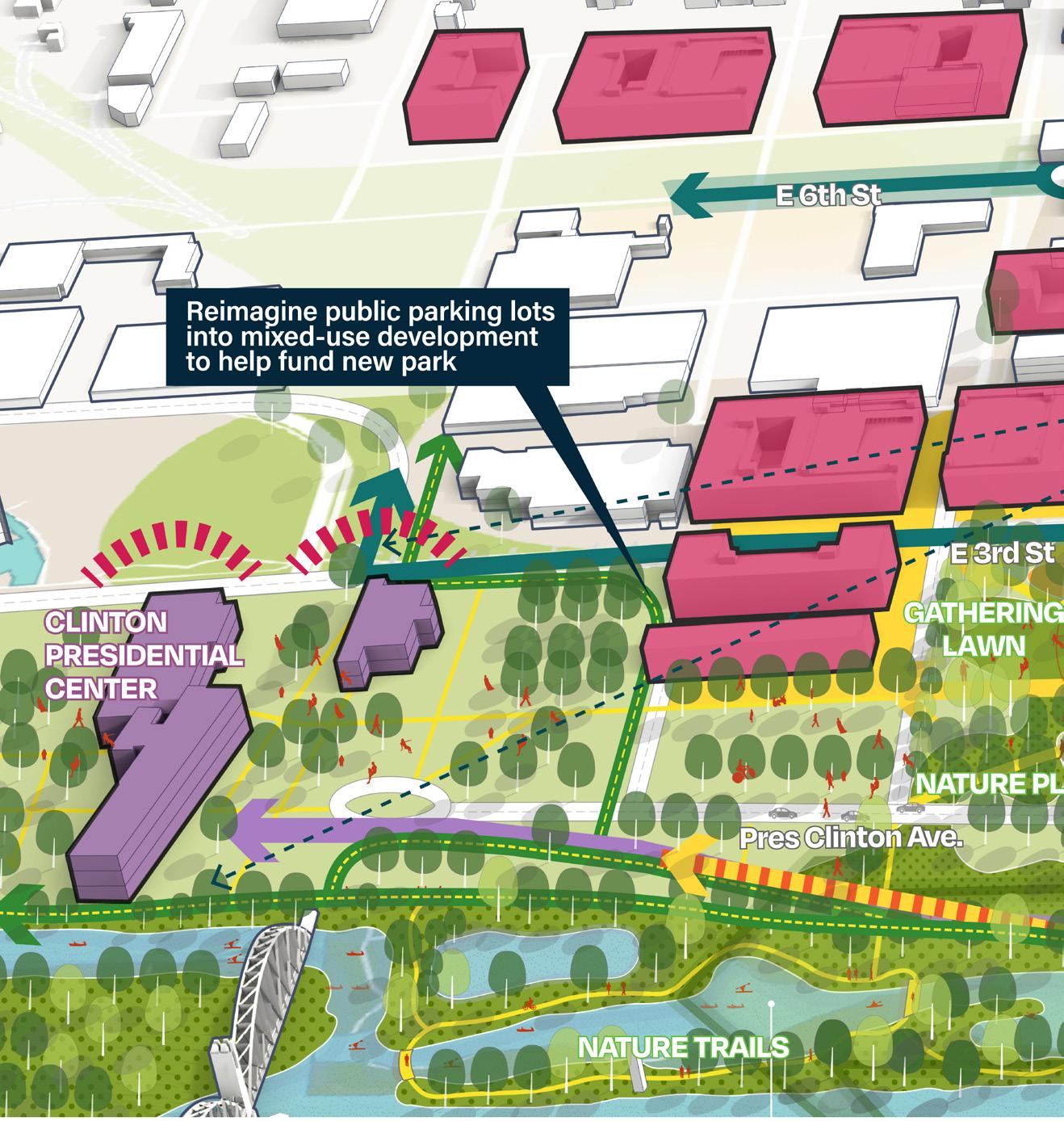

24 DOWNTOWN LITTLE ROCK MASTER PLAN

A roadmap for creating a complete neighborhood.

32 ROLLING ON THE GREENWAY

Central Arkansas Regional Greenways Master Plan boosts transport, fosters growth.

34 CHECKING IN OR CHECKING OUT?

Short-term rental regulation in Arkansas varies depending on municipal needs.

36 DEVELOPER’S DIARY

Forming the unconformable in the Pettaway Neighborhood.

40 NEW VENTURES IN PARAGOULD

100-year-old power plant reimagined downtown.

42 THE EDUCATOR MAYOR

Rick Elumbaugh’s 48-year tenure is rooted in listening.

44 DOWNTOWN, DOWNTOWN

Maxfield Park, Royal on Main marry history and vision in Batesville.

48 OUR LITTLE ROCK

Mobilizing residents to shape a more livable Little Rock for all.

51 REIMAGINE THE TOWN YOU LOVE

2 winning plans from urban designers.

54 CABOT’S URBAN RENEWAL

Reimagining downtown as a space for art, entertainment and fellowship.

56 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT

Public planning culminates in a new form of Rogers.

58 CRAFTING COMMUNITY

Central Arkansas’s Brandon Ruhl a pro at finding new uses for old gems.

ON THE COVER: Pettaway Square offers a unique model for placemaking from an infill development standpoint. Photography by Sara Reeves. See page 36.

A Special Publication of Arkansas Times Produced in partnership with the Arkansas Municipal League

BROOKE WALLACE Publisher brooke@arktimes.com

JAMES WALDEN Editor

BECCA BONA Managing Editor

MANDY KEENER Creative Director mandy@arktimes.com

EVAN ETHRIDGE LUIS GARCIAROSSI

TERRELL JACOB

KAITLYN LOONEY

LESA THOMAS Account Executives

WELDON WILSON Production Manager/Controller

ROLAND R. GLADDEN Advertising Traffic Manager

MIKE SPAIN Advertising Art Director

ROBERT CURFMAN IT Director

CHAROLETTE KEY Billing/Collections

JACKSON GLADDEN Circulation Director

ALAN LEVERITT President

TAGGART Architects has helped Arkansas communities from the Delta to the Highlands revitalize their downtowns with exciting and vibrant public spaces since 1974.

Our Philosophy

We believe great architecture and design respects history, listens to local voices, and keeps an eye on the future.

We turn visions into realities, Weave stories into structures, And breath soul into architecture. At TAGGART, detail makes design.

inety years is a long time. Heck, 50 years is a long time — although I just turned 64 on April 3, and neither 50 nor 90 seem nearly as long as they used to. Perspective is a powerful thing.

The Arkansas Municipal League celebrates its 90th birthday this year. The League was created in 1934 by the extension office in affiliation with the University of Arkansas. I know the League’s history pretty well, after all, I’ve worked there since 1989. Again, perspective. As in, “Yikes, I’m old!” Likewise, the Arkansas Times is marking 50 years in 2024. I don’t know as much about the Times’ history, although a little research told me that Alan Leveritt launched it in 1974 with a mission to increase investigative reporting in our state. Known briefly as Union Station Times, the Arkansas Times moniker was implemented the next year and has remained in place for the past five decades. Collectively, that’s 140 years of service between the two organizations.

Here are a few things that occurred, some in Arkansas and others not, in 1934 and 1974 that have shaped this state and will continue to do so.

1934: The Dust Bowl began.

1974: Arkansas’s first nuclear reactor, known as ANOUnit One, went online.

1934: Art Porter Sr. was born. He became an international jazz musician.

1974: National Baseball Hall of Famer and Arkansas native Dizzy Dean died.

1934: Future U.S. Senator David Pryor was born in Camden.

1974: Derek Fisher was born in Little Rock. He played basketball with the University of Arkansas at Little Rock and won five NBA Championships with the Los Angeles Lakers.

1934: William Delford (Willie) Davis was born in Louisiana but raised in Texarkana. He was a star defensive player for Grambling State University while making the dean’s list twice. Davis went on to star for the world’s greatest football franchise, the Green Bay Packers. Yes, I’m a cheesehead! He won six championships including Super Bowls I and II!

1974: George Foreman and Muhammad Ali fought for the heavyweight boxing championship of the world in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in what was billed as The Rumble in the Jungle!

The League and the Times have very different missions but share some common traits. First, transparency. Just like local government here in The Natural State, the League is an open book. Similarly, the Times appears more than willing to let the public peer into its operations and welcomes readers’ commentary and thoughts, both positive and negative. Both organizations are information centric. Specifically, information that must be accurate and confirmed. These objectives and

purposes found in the League’s constitution reiterate that point:

Promote best practices in municipal government. Promote the education of municipal employees and officials.

Maintain and distribute information, research and analysis of municipal issues.

Publish educational materials, special reports, brochures, magazines and newsletters of interest to municipalities.

The Times reports on current events and newsworthy stories. It does that by looking at information relevant to the item being reported on. Research, facts and publications, just like the League.

This year’s edition of Block, Street & Building shines a spotlight on Arkansas’s uniqueness and happens to underscore the League’s tagline: “Great Cities Make a Great State!” There’s so much happening in the cities and towns of Arkansas that should make us beam with pride. We have a fantastic dining scene and no matter the destination, you’re certain to enjoy a great meal. Here are a few gems: The Grumpy Rabbit in Lonoke, The Eden at Hotel Hale in Hot Springs, Trio’s in Little Rock and The Wilson Café in Wilson. If you’re not sure where to start, consult one of Arkansas’s local food blogs or podcasts for endless recommendations.

This issue is filled with stories of growth and progress in our state, like Little Rock’s Pettaway Development, the comprehensive community development plan in Rogers, the housing report in Fayetteville, the Central Arkansas Regional Greenways Master Plan, a statewide review of short-term rentals, the revitalization efforts of The Station, Paragould’s historic power plant, the rebirth of downtown Batesville, and more. Our state is blossoming with opportunities that not only make our lives better, easier and more enjoyable, they also mean jobs and real economic strength for our cities and towns.

I’ve yet to mention the many annual festivals we have access to, so here’s a few: The Gillett Coon Supper, The Magnolia Blossom Festival and World Champion Steak Contest, The Cave City Watermelon Festival, The Tontitown Grape Festival, The Winfest Music Festival in Winslow, The Frontier Day Festival in Paris, The King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena-West Helena and the New Year’s Eve Ball Drop in Fort Smith.

Folks, Arkansas is a hidden gem amongst the other 49 states and we need to enjoy every vista, forest, lake, river, festival, diner, downtown, park and public space! But mostly, we need to relish our fellow Arkansans and their kind, loving and giving personas found in every city and town.

Mark R. Hayes Executive Director Arkansas Municipal League

Mark R. Hayes Executive Director Arkansas Municipal League

What differentiates places that represent good urbanism from the bad? This is a question often pondered by many in the community of professionals and advocates that love cities. However, the answer is fairly simple. Places built around people are the heart of good urbanism.

Building places around people means building at a human scale. It means keeping the experience of the person in mind, creating places that feel interesting, safe and unique. It means celebrating the history and character of the people of the place. It means creating a place that can be navigated by foot as a main means of transportation. Places built like this inspire, entertain and invite someone to make the place part of their story. However, building this way isn’t always the easiest.

There are a whole host of issues that influence how places are developed. Maybe it’s a developer or banker unsure that a shift in the type of product they build or finance will be successful. Maybe it’s outdated, outmoded federal policy that propels forward the status quo. Maybe it’s an elected official or city planner gun shy from pushing reform because doing so can be an obstacle to remaining elected or employed. And, maybe sometimes it’s unfortunately plain ignorance or believing somebody else will make it happen.

This edition of Block, Street & Building focuses on places for people. You’ll see stories celebrating the history and form of a place. Stories about how cities are planning to repeople formally cherished, vibrant places. You’ll hear about amenities and people that have a catalytic effect on places to make them better. Additionally, this edition features winners of the second year of the Reimagine the Town You Love design competition. These submissions represent the hope in our state to continue creating good urbanism. Finally, I’d like to say a big thank you again for the opportunity to serve as editor for this edition of Block, Street & Building. I hope you enjoy these stories and are inspired to help create places for people.

James Walden, AICP, is an urban planning leader with Garver.

Entergy Arkansas is committed to a sustainable future. We’re working toward net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, and we’re helping our customers lower their emissions as the leading adopter and provider of solar in Arkansas. If your business shares similar goals, we have several programs to help you get there.

Green promise and zero-emission offerings

Get access to clean energy resources and reduce your Scope 2 carbon emissions at little or no cost. We’ll even retire your renewable energy credits on your behalf.

E-tech

Qualifying customers can find cash and training incentives to help make the transition to electrically powered equipment. An electric fleet will benefit your business and the environment.

Schedule a free energy efficiency audit of your facilities to find ways to save money on your bill and reduce Scope 1 emissions.

more at entergyarkansas.com/brightfuture

Urbanism concerns how inhabitants of urban areas interact with the built environment. The built environment, however, does not always prove to be a stable entity, particularly in the historical context. Ask Little Rock architect Tommy Jameson. He knows.

Jameson enjoys a justified reputation as a designer with an exhaustive list of achievements. These include work on all four of the museums owned and operated by the state’s Division of Arkansas Heritage. His work has generated awards including the Parker Westbrook Lifetime Achievement Award from Preserve Arkansas.

He has also committed his time to preservation through volunteering with Quapaw Quarter (receiving their Jimmy Strawn Award in 1996), Little Rock Historic District Commission, Capitol Zoning District Commission, Arkansas Chapter of the AIA (receiving the Dick Savage Memorial Award in 1992) and Preserve Arkansas, serving as president in 1993.

Jameson’s journey took him from a childhood in Little Rock, to a senior year of high school in Malvern, and to the University of Arkansas Fay Jones School of Architecture. It then led to the pinnacle of respect in his profession. Along the way, he and his wife, Christy, have enjoyed a marriage of 40 years, a union that produced two children, Kauley and Aly Clare.

Jameson credits his interest in historic work to two factors. One involved legendary architecture instructor Cyrus “Cy” Sutherland of the University of Arkansas, who taught an elective course on preservation in 1976. The other was to join the firm of Witsell and Evans. Charles Witsell was one of the founders of Preserve Arkansas and a local icon in historic preservation.

Jameson remembers Witsell asking him about specializing in preservation. He responded, “Gosh, Charles, I don’t know, that’s a big commitment, that’s a big step, I’m not sure.”

A decision followed, and the rest, as they say, is history. As

Jameson’s reputation grew, he established his own firm. His architectural journey took him from restoration of the state’s Senate Chamber in its capitol building to an 1846 log plantation house in Drew County, Arkansas.

Then there was the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center.

The entrance to Ninth Street from Broadway once led to the vibrant African American commercial corridor of Little Rock. Time proved unkind over the years, and the 1980s found the area almost deserted. Only skeletal fragments of the commercial district survived.

One remaining building stood at the southwest corner of the subject intersection. An early “mixed-use” structure, the ground floor of the building originally housed retail as part of the commercial strip. Its top floor housed an auditorium where African American

entertainers of such stature as Count Basie had performed. The middle floors contained the offices of the National Headquarters of the Mosaic Templars of America.

From the Encyclopedia of Arkansas: “The Mosaic Templars of America (MTA), an African American fraternal organization offering mutual aid to the black community, was founded in Little Rock in 1882 and incorporated in 1883 by two former slaves, John Edward Bush and Chester W. Keatts. Taking its name from the biblical character of Moses, the organization offered illness, death, and burial insurance to African Americans at a time when white insurers refused to treat black customers equally.”

In 1911, the MTA established its national headquarters, the National Grand Temple, at the corner of West Ninth and Broadway streets. Frank M. Blaisdell was the chief designer for the four-story building which was dedicated at its completion on May 18, 1913, by Booker T. Washington.

By the 1930s, the Great Depression had contributed to the demise of the MTA. The Jim Crow laws of the South made it hard for African American businesses to survive. The last inter-urban

The question looms in historic preservation as to what building codes will prevail. Jameson cited what local architects and builders call “The Roy Beard” test, named after a legendary Little Rock code enforcer. Beard often posited that when the cost of rehabilitation exceeded 50% of the value of the building, new codes must come into effect.

Those who have worked on restoring old homes know the trials of the “shrinking two-by-fours.” For this job, modern technology in the form of a then-new software program called “Revit” proved a godsend. It allowed the architects to translate plans into visual information concerning such building items as oversized bricks that were necessary to replicate the historic proportions and detailing.

Keeping the ground floor in historic harmony was a challenge. Retail businesses need windows. Museums need wall space. One result was an opaque black granite covering that suggested windows from the outside but provided uninterrupted wall space on the inside.

Although the entire top floor contained the auditorium, fire safety regulations mandated a reduced size and fewer occupants. This

IN JAMESON’S RECOLLECTION, AFTER A BRIEF PERIOD OF MOURNING, THOSE IN CHARGE TASKED HIM WITH THE DESIGN OF A REPLICA OF THE ORIGINAL BUILDING WITH THE MISSION OF HOUSING A MODERN MUSEUM.

freeway allowed in an American city, Interstate 630, tore through, and completed the destruction of the Ninth Street business district. The Mosaic Templars building and its annex immediately to the south stood in sad shape.

Then there was the Mosaic Templars Preservation Society.

This organization of volunteers worked to preserve the original structure. Its members persuaded the Arkansas Legislature to support the preservation of the building. Act 1176 of 2001 established the Mosaic Templars of America Center for African American Culture and Business Enterprise. The building would become a museum housed under the Arkansas Department of Arkansas Heritage (now the Division of Arkansas Heritage). This settled a major decision in preserving the past, but what next?

Jameson credits the beginning of his association with the project to the fact that an upholstery mechanic who cared for a treasured Jeep CJ-5’s soft top operated in the back of the aging Mosaic Templars building.

This eventually led to design and construction drawings for rehabilitation and reuse. The firm Carson and Associates would undertake the construction. They were six weeks into construction before the disaster.

On a chilly March evening, transients broke into the building to seek shelter. They built a fire on a piece of sheet metal, lost control of it and fled as the fire spread. The city awoke the next morning to the jagged remains of one of its most historic buildings.

In Jameson’s recollection, after a brief period of mourning, those in charge tasked him with the design of a replica of the original building with the mission of housing a modern museum. With that, he went to work.

As he recounted the times, he listed areas in which history, function, funding, and technology intertwined.

The original building was a mixed-use structure with groundfloor retail, middle-floor offices, and a fourth-floor auditorium. The reconstructed building would have those functions with exhibit spaces replacing the retail.

worked to some advantage by allowing room for restrooms, stairs and support space.

Because of its historic context and public ownership, the rare cost-plus approach to the construction contract allowed flexibility and protection from so-called “black swans,” or totally unforeseen problems that can plague such projects.

Adding the former adjacent annex building to the project became a reality with subsequent grant cycles.

With such factors at work, the project reached completion, an architectural phoenix rising from the ashes of history. It is open now and free to the public.

Of his recent private projects undertaken within the framework of historic preservation, Jameson cites Hill Station, a restaurant at Kavanaugh and Beechwood.

Developed by Doug Martin and Daniel Bryant, the site originally housed a fire station. Next, a “filling station” occupied it from until 1980, then a garage until 2016. The unique challenge was to utilize the existing building while adding on to the overlay district’s requirement to build to the street and to create a “restaurant within a park.”

The transition from historic fabric to new warranted major decisions. According to Jameson, “The project included relocating an adjacent early 1900s house to Van Buren Street (to make room for parking) where it was rehabilitated and remains listed as a contributing structure in Hillcrest.”

Jameson is now semi-retired. He cites several up-and-coming architects to note, mentioning an 11-year member of JAMESON Architects — Amoz Eckerson.

It would seem, then, that accommodating our heritage is possible within the flow of urbanism. It just takes talent, diligence and the willingness to make complex and difficult decisions.

Jim von Tungeln is an urban planner and staff planning consultant with the Arkansas Municipal League.

Historic preservation is an essential part of community and economic development. Arkansas’s historic buildings tell stories about commerce, government, transportation, education, agriculture, recreation, social norms and more. Their preservation and reuse create distinctive places where people want to live, and it’s good for the environment, conserving materials and embodied energy.

Since 1976, the U.S. government has encouraged the rehabilitation and reuse of historic buildings through its Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives program. This program provides a 20% income tax credit, taken ratably over a five-year period, to owners of income-producing property who complete a certified historic rehabilitation. According to the “Annual Report on the Economic Impact of the Federal Historic Tax Credits for Fiscal Year 2022” published this year by the National Park Service in cooperation with Rutgers University, the Federal Historic Tax Credit (HTC) program “remains the Federal government’s largest and most effective program supporting historic preservation and community revitalization,” incentivizing private investment in communities nationwide and yielding a net benefit to the U.S. Treasury.1 According to the report, in FFY22 alone, federal HTC projects in Arkansas supported 585 jobs resulting in $19.7 million in earned income, $29.3 million in GDP and $52.2 million in economic output. These projects also generated a total of $6.3 million in federal, state and local taxes.

Recognizing the economic potential of a companion state HTC, the Arkansas General Assembly created the Arkansas State Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credit Program in 2009. Improvements to the credit were instituted in the past four regular legislative sessions, the most recent of which took place in spring 2023. The

Before and after views of the River View Inn, originally completed in 1923 and recently restored by sisters Tracy Owens and Cathy Beard.

Arkansas State HTC Program provides a credit on state income tax or insurance premium tax for the certified historic rehabilitation of owner-occupied and income-producing properties. There is a program-wide annual cap of $8 million per fiscal year as well as per project caps for owner-occupied and income-producing properties, respectively. The cap on qualified rehabilitation expenses for owner-occupied properties is $100,000, while the cap for incomeproducing properties is $1.6 million. The credit percentage is tiered based on the population of the municipality in which the project takes place, providing a significant incentive for the rehabilitation of historic properties in small cities and towns. Beginning in July 2023, projects in municipalities with a population of less than 10,000 may receive a 40% credit; projects in municipalities with a population between 10,000 and 50,000 may receive a 35% credit; and projects in municipalities with a population greater than 50,000 may receive a 30% credit. Regardless of location, every HTC project in the state benefits from this change, as the credit percentage was previously set at 25% across the board. The Arkansas State HTC is fully transferable. It is also important to note that income-producing projects that qualify may take advantage of both the federal and state HTC, potentially receiving a 60% tax credit on a project in a city of fewer than 10,000 people.

The vast majority of Arkansas municipalities are small cities and towns. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, 463 (or 93%) of Arkansas’s 500 municipalities have a population of 10,000 or less. The new tiered percentage can produce transformative results, saving places that matter and reactivating often vacant or underused spaces, making them valuable community assets. Take the River View Inn at Calico Rock (population 888) and the St. Charles Building at Pocahontas (population 7,371) as recently completed examples.

The historic St. Charles Building, built in 1859, underwent a complete rehabilitation by Dr. Patrick Carroll, bringing new life to its vacant spaces with retail, office and residential units.

Located on the north bank of the White River in Izard County, Calico Rock is a charming city with native stone buildings and picturesque views of calico-colored river bluffs. Calico Rock is known for its trout fishing and has long been an attractive location for tourists and retirees. Situated on a hill overlooking Main Street and the White River, the aptly-named River View Inn was completed in 1923. The building was constructed using ornamental concrete block, a popular building material during the early 20th century that could be substituted for any use of brick or stone. The concrete blocks on the River View Inn were made with a rock face to resemble cut stone. Over the years, the building operated pretty consistently as a hotel or bed and breakfast but sat vacant and overgrown before this project. Sisters Tracy Owens and Cathy Beard purchased the hotel and began work in January 2022 to address decades of deferred maintenance and update the building’s interior spaces, plumbing and electrical systems to make it a viable business once again. Additional family members got involved to help rehabilitate historic wood windows and doors, paint and stencil the concrete floors. The project was completed in summer 2023 and received a 40% state HTC and 20% federal HTC. Now known as the Calico Riverview Inn Bed and Breakfast, the building offers nine guest rooms with unique amenities and homemade breakfast served daily. The reopened Calico is already making a positive impact on the region’s tourism economy. According to Owens and Beard, 2024 occupancy is up 66% with a revenue increase of 113% over last year already.

Pocahontas, the Randolph County seat of government, sits along the Black River where the Delta meets the Ozarks. The city is an educational and agricultural center in the area and is home to Black River Technical College. Located on the courthouse square

in downtown Pocahontas, the St. Charles Building was constructed in 1859 to serve as an annex for the St. Charles Hotel. It is now the oldest extant building in the city. The St. Charles Hotel was known for its hospitality and good food. After the older part of the hotel burned in the 1920s, the annex continued to house the Pocahontas Star Herald and a barber shop, while the upstairs offered rooms for rent. In the intervening years, a variety of businesses occupied the first floor of the building until about 2005, but the upstairs was vacant for more than 50 years.

When Dr. Patrick Carroll purchased the St. Charles Building in 2011, it was vacant. Several years later, he began a full rehabilitation of the building, which was completed in fall 2023 and received a 40% state HTC and 20% federal HTC. The project included a new roof (including the installation of a solar array), masonry repair, restoration of the original storefront configuration, all new systems and interior finishes, restoration of windows and doors, and more. The building’s first floor now offers retail or office space for lease, while the second floor houses one short-term rental unit and a larger apartment unit for long-term lease. The rehabilitation of the St. Charles Building is a beautiful project that put a prominently located, historically significant property back into active use.

Rachel Patton is executive director of Preserve Arkansas, the only statewide nonprofit advocate for the preservation of Arkansas’s historic places. Contact her at rpatton@preservearkansas.org.

1Technical Preservation Services, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior and Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, “Annual Report on the Economic Impact of the Federal Historic Tax Credits for Fiscal Year 2022,” February 2024.

Destination dining successes in Clarksville, Hot Springs and Lonoke.

BY LINDSEY FISHERIn the heart of a city renowned for its national park, vibrant arts scene and rich history, DeLuca’s Pizza has become a beloved dining destination for Hot Springs locals and tourists alike.

Culinary gems that offer an experience from plate to palette to atmosphere often are destinations in and of themselves. The capacity these restaurants have to attract locals and out-of-town visitors alike makes them an important part of the local culture.

Prestonrose in Clarksville, DeLuca’s in Hot Springs and The Grumpy Rabbit in Lonoke have become such destinations. The owners, managers and staff at these three restaurants live with an unbeatable passion for their business and the food they serve. Undoubtedly, these destinations have become woven into the fabric of their communities, and it is easy to see why people will travel far and wide in order to experience what they have to offer.

Fans who have had the opportunity to eat and drink at Prestonrose’s certified USDA organic farm over the years have likely met the family behind the destination’s one-of-a-kind dining experience. From fresh ingredients that are cultivated from the farm, and others in the area, to being the only certified craft malt brewery in Arkansas, Prestonrose is a destination worth traveling to. And their new location in downtown Clarksville is no different.

Liz and Mike Preston move with great passion for their business and the local farming community. Liz shares that their entire identity comes from protecting the history of places and families in the community. “We believe in transparency in all things food, drink and business,” she said. “It’s important to know where everything we eat and drink comes from, who handles it, and how long it’s been ‘out there.’ We are all about sustainability and being valuable stewards of the land.”

This same type of passion and commitment is what led to their new location on Clarksville’s Main Street. Housed in a restored 1940s automotive shop, the farm-to-town establishment features the original stone walls, historic tall ceilings and new metal work from local artists. “Everything you encounter from the food to the design aesthetic was curated with great intention,” Liz explained.

In partnership with the building’s current owners, the University of the Ozarks, the Prestons worked hard to create two distinct spaces for visitors to enjoy — the general store, which houses local products, and the restaurant, where patrons can order all the menu items that were once only available at the farm.

The Mercantile Clarksville offers coffee (locally roasted, of course), ice cream (Loblolly of Little Rock), house-made bagels, artisan cheese, salads, espresso coffee with locally made syrups, deli sandwiches, local eggs and fresh milk. At the Prestonrose Towne Bistro, there’s a beautiful dining area, a bar and a custom kitchen. “Dining with us, whether it’s a regular night at the bistro, or special event at the farm, is a unique, informative and thoughtfully prepared experience,” Liz said. “Our menu rotates monthly and allows us to fully evolve with seasonal availability of produce and meats. We also offer plenty of gluten-free and vegan options and are always willing to work with folks who have special dietary needs.”

Look for farmers market brunches at their new location as well as upcoming classes like cheese and pasta making. Beer lovers can still make appointments at the farm to fill growlers with local favorites, such as Abigail’s Okra Brown that uses a centuries-old Southern recipe for “okra coffee,” and the Dragon Volant, a French farmhouse saison that uses locally foraged trifoliate oranges.

Hot Springs is already a tourism destination, thanks in part to the national park, a variety of shops, vibrant arts scene, museums and interesting history. Therefore, the fact that there is a coveted restaurant with a cult following should come as no surprise to Spa City lovers.

At DeLuca’s you’ll find brick oven pizza, handmade dough, fresh local ingredients and an owner who has brought all his passion and memories of growing up in Brooklyn, New York, to the community of Hot Springs.

Anthony Valinoti has successfully recreated the feel of an old school Italian restaurant from his neighborhood of Bay Ridge with an atmosphere that is simultaneously fun, dark and loud. Stepping into the eatery feels a bit like walking back in time.

“EVERYTHING YOU ENCOUNTER FROM THE FOOD TO THE DESIGN AESTHETIC WAS CURATED WITH GREAT INTENTION.”

—LIZ PRESTON, PRESTONROSE

“DeLuca’s is a theater of my imagination. We have a large, inviting patio and an amazing bar. The decor is made up of red banquettes, red chairs and large headshot photos of our oldest and dearest clients,” Valinoti explained. “The music is also crucial, I think, to our restaurant. I have a 50-hour playlist that I tinker with all the time to create the right mood depending on the crowd that day. It’s all these tiny little pieces that build the beautiful fabric that DeLuca’s has evolved into.”

The inspiration for the pizza joint actually comes from a pivotal time in Valinoti’s life. “DeLuca’s was born out of loss, the loss of my parents two days apart. It set the wheels in motion. I set out on this journey to find myself again, and in the process I accidentally created a pretty amazing little place and my home,” he said.

Born out of such passion and attention to detail, it’s no wonder that the pizza is top-notch; just ask Dave Portnoy from Barstool Sports. He went crazy for the Sidetown pizza (which is also Anthony’s favorite pie). This stamp of approval made DeLuca’s an overnight sensation.

top to bottom: The exterior of

“WE ARE PROUD TO BE AN INTEGRAL PART OF THE DOWNTOWN REVITALIZATION.” —KEVIN DARKER, THE GRUMPY RABBIT

Visitors can expect fresh ingredients in every dish. In other words, if it comes out of the ground — it’s grown locally. Basil, onions, mushrooms, tomatoes and herbs are grown by farmers in the surrounding regions. Valinoti shares that the number one selling pizza is the Patsy Searcy — which comes with spicy soppressata, Calabrian chili oil, peppadews and honey. “But I am a cheese pizza kind of person,” he said. “So, a simple cheese pizza has to be the best thing in your arsenal.”

Later this year, DeLuca’s will open a second location in Little Rock, offering award-winning pizza in both Hot Springs and the capital city.

Lonoke’s only full-service restaurant boasting a full bar happens to include an award-winning kitchen. Cue The Grumpy Rabbit.

This classic Arkansas downtown establishment started as a way for the Cox family, owners of The Grumpy Rabbit, to help pump life back into the once-thriving downtown district. Since then, it has become a gathering point for locals in Lonoke and is a popular stopping point for anyone commuting along Interstate 40.

And if you’ve had a chance to sink your teeth into any of their specials, it’s not hard to see why this establishment has become such a popular destination. Local favorites include the 14-ounce ribeye, Swamp Grits and carrot cake. However, the most sought-after item is the award-winning Grumpy Burger.

Kevin Darker, general manager of The Grumpy Rabbit, said, “We are fortunate to be surrounded by local farmers that provide us with bountiful farm-to-table opportunities that allow us to offer locally sourced specials and frequent menu upgrades. We are proud to be an integral part of the downtown revitalization, and our farmers are proud of their products in our specials.”

Kevin says the team’s entire mission is to “enrich the lives of those in the community and to provide quality food, beverages and legendary service that aims to bring the community together like one big family.”

Not to mention, the atmosphere is off the charts. There are pops of color, neon lights and art on display. “From the art to the architecture, everything at The Grumpy Rabbit is local,” Darker said. “The building itself is a visual feast.” Here, patrons can find private rooms for intimate gatherings, large spaces for groups, a bar and 12 large-screen televisions. There is also a downstairs and upstairs patio woven with string lights and art. Dining at The Grumpy Rabbit for a night out or as a stopping point on a long drive is not to be missed.

The Grumpy Rabbit is truly of the community. The restaurant’s namesake honors both the local community and the Cox family.

“Gina Cox was the point guard on the Lonoke 1977 State Champion basketball team whose mascot is none other than the Jack Rabbit. Gina’s husband, Darrel Cox, who is a long-time local farmer, is one of those individuals that the corners of his mouth just turn down,” Darker said. “His family gifted him the name ‘Grumpy.’ Together they are The Grumpy Rabbit.”

Lindsey Fisher is an Arkansas-based freelance writer and photographer focused on promoting tourism in The Natural State.

Fayetteville considers zoning changes, permit-ready building design program.

BY BRITIN BOSTICK

The city’s recent housing assessment highlights the need for 1,000 new

Since the start of 2020 a combination of factors left Fayetteville residents challenged to find housing that is within an affordable price range. These include but are not limited to: higher-than-projected population growth, record-breaking enrollment at the University of Arkansas, changes in financial markets leading to high interest rates, and delays in housing production caused by supply chain issues and construction labor shortages. Knowing these factors had been at play for the past three years but needing more definition to the scale of the issue, the city’s Long Range Planning team led a Housing Assessment that was published in October 2023.

Fayetteville needs about 1,000 new units of housing annually to keep pace with projected population growth. Beginning in 2019, however, Fayetteville’s population growth began to increase at a rate beyond housing production. From 2019-2022 Fayetteville fell about 1,480 housing units short of demand, and from 2021-2022 the population growth was 78% above projected.

An estimated 15,853 households, or 38% of Fayetteville’s total

households, were cost-burdened by housing costs as of 2022 (paying more than 30% of household income on housing costs).

More than half of Fayetteville households need housing at a cost below current average rent.

Fayetteville would need an additional 8,426 housing units at costs calibrated to specific income levels to have affordable housing options for the projected population growth to 2045.

Fayetteville’s current zoning is similar to what it was in 1970, emphasizing low-density development despite more than tripling the total population since then.

If all new housing units needed for the projected population growth by 2045 were built as single-family housing in the city’s predominant low-density pattern, it would require nearly 7,000 acres of land, or 11 square miles, and more than 156 miles of streets, water and sewer. However, if current population growth trends continue and the housing units needed for the current growth rate were built as low-density, single-family homes, it would require more than 12,000 acres of land — approximately one-third of Fayetteville’s current land area.

According to the projections captured in the Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission’s 2020 Transportation Plan, Fayetteville’s population was expected to reach 97,917 by 2025. According to the U.S. Census and American Community Survey estimates, the count of the city’s residents blew past that projection in just two years, growing from 90,993 people in 2020 to 99,288 people in 2022. Fayetteville was the second-fastest growing city in Northwest Arkansas from 2020 to 2022 by proportion of population increase, taking on 17.8% of population growth in the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and 34.1% of population growth among the four largest cities in the region — Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers and Bentonville. In addition, enrollment at the University of Arkansas grew by nearly 4,600 students from fall 2020 to fall 2023 with no additional beds added on campus to absorb the additional housing demand.

More students than ever needed to find housing in Fayetteville after having a COVID-era option to attend classes virtually and remain at home in other cities, or even other states. Unlike most growth caused by in-migration that happens over weeks or months, university enrollment growth is observed over the course of a week in late summer when new and returning students arrive and housing, parking and restaurant tables quickly become more scarce. For the city’s building inspectors, summer can be one of the busiest times of the year as student-oriented apartment complexes rush to complete units and move new tenants in, and new housing developments with leases signed for fall residents feel pressure from parents ready to get their students settled before classes start. It’s an annual cycle that has repeated for decades, but never with this many new people added to the equation for both the student and non-student variables in such a short period of time. The last time Fayetteville grew this quickly was from 1940-1950, when the city’s population of 8,212 more than doubled to 17,071 in the decade that saw the end of WWII and the beginning of American servicemen enrolling at the UA as a benefit of their wartime service. There was not enough housing at that time, either, which led to concerns about overcrowding and congestion that still echo through Fayetteville’s zoning code today.

While the Housing Assessment found that Fayetteville fell hundreds of housing units short of demand in the last few years, the city issued permits for more than 10,000 housing units over the last decade. Single-family homes and apartment units made up nearly 86% of the 11,106 residential permits issued from 20142024. 2017 had the fewest residential permits issued in that decade with just 650 (only 192 multifamily units were issued permits that year), and 2019 had the highest number of permits issued at a record 1,693 (over 1,000 multifamily units were issued permits that year). Ironically, that record year for residential permits was the beginning of Fayetteville’s population growth peeling away from housing production as demand began to outpace supply. The obvious question was how many of those issued permits resulted in available housing? (see Figure 1).

Permit records show that from 2019 to 2023, 5,884 housing units had been issued a certificate of occupancy. 2020 and 2022 had the

two lowest years of housing production in that half-decade with 909 units and 847 units, respectively. In 2019, 1,269 units were completed, and a record 1,706 units were completed in 2023 for a five-year average of 1,176 units. That nearly matches the annual average of 1,179 residential units issued permits for the same period. And it’s still not enough.

Even as more people are seeking housing in Fayetteville, the number of people per household is lower here than for the state as a whole. Fayetteville averaged 2.19 people per household in 2022 compared to an average of 2.44 in Arkansas — 15,967 or 71% of nonfamily households had one person in 2022, and 13,684 or approximately one-third of all households in Fayetteville had two people. Household formation — or the lack of it — is a component of housing demand that can either exacerbate or reduce demand pressures. When housing costs are high or supply is low, it might seem reasonable to expect an increase in the number of people per household as residents find solutions to fit their needs. The Fayetteville data has not shown that to be occurring, however, even as housing costs have rapidly increased for both renters and owners (see Figure 2).

From 2000 to 2022, the median house value in Fayetteville as captured by the U.S. Census and American Community Survey more than tripled, and median gross rent increased by 54%. At the same time, median household income increased by only 69%. As a result, an increasing number of Fayetteville households are unable to afford housing costs here, and as of 2022, 38% of Fayetteville residents were cost burdened by housing — paying more than 30% of their income on housing costs, such as rent or mortgage, utilities and insurance. Data from the Center for Business and Economic Research at the University of Arkansas’s Sam M. Walton College of Business suggests there is a nuance to Fayetteville’s housing market not captured in the federal data. Although Fayetteville’s average new apartment in 2023 rented for $922 — just $5 per month below the 2022 estimate by the U.S. Census — that $922 was heavily weighted toward a housing product nearly (or possibly completely) unique to Fayetteville in the state of Arkansas. Lease by the bedroom (“By-the-Bed” in Figure 3) student housing is a popular housing type accounting for many of the multifamily units in the city. Apartments with a single kitchen unit may have three to five bedrooms, each with their own bathroom, leased individually to college students who then don’t have to worry about covering rent if a roommate moves out (or doesn’t move in at all). These leasing units account for 74% of the units surveyed for the data in Figure

3, and they have substantial downward pull on the monthly rent average, although they are typically not available to nonstudent residents. New, traditional two-bedroom apartment units rent for substantially more at $1,440 per month. At that rate, a household would need an income exceeding $64,000 annually (around $31/ hour or more) for that rent to be affordable.

Eighty years ago, Fayetteville was faced with its first population boom. A small town of just over 8,000 people, its agricultural heritage was just beginning to transition to a different mode of economic prosperity, and the new homes constructed to house twice as many residents felt overwhelming in a way our community would recognize today. At the time, land was inexpensive and readily available to the north and west of downtown, and the city’s leadership chose to follow national practices and the state highways already crisscrossing the city and grow outward, adding low-density neighborhoods and single-story commercial buildings toward Springdale to the north. This pattern continued for decades as Fayetteville’s expansion consumed small farming communities once noted as being “3 miles from Fayetteville” and created housing densities that averaged barely two units per acre. It’s a pattern that Fayetteville began reconsidering more than two decades ago and began in earnest to address about a decade ago with changes to how we plan and invest.

Cities bear the costs of housing in many ways, but perhaps most recognizably in the costs of constructing and maintaining public infrastructure. Housing is connected by streets and serviced by water and sewer in cities, with the city government taking on either a lifetime of operation and maintenance costs for these infrastructure elements if they are dedicated by a developer, or

building and maintaining them from the start. Infrastructure represents future liability, with road surfaces needing replacement every 15-20 years on average and full replacement of water and sewer systems typically occurring less frequently, but at costs above and beyond annual city budgets. For the city to be able to afford new housing, it must be built more centrally and more compactly, a change in direction from the course set eight decades ago.

Fayetteville’s comprehensive plan, City Plan 2040, prioritizes appropriate infill development; a walkable, connected city; and housing opportunities. It was adopted in early 2020, just before housing demand began to noticeably outpace supply. City Plan 2040 captured elements from previous city plans that recognized the city needed to change its course and provided a foundation to support the work underway today. The work includes an ongoing assessment of housing and the demographic and market changes that affect housing supply and affordability; a PermitReady Building Design Program to create neighborhood-sensitive housing in areas of the city’s historic core undergoing rapid redevelopment; infrastructure investment that provides complete transportation connections and safe streets; and large-scale zoning changes to provide hundreds of acres of housing opportunity in central areas of the city that have not permitted housing over the last several decades. These transformative projects adjust the city’s course for 2045 toward a different set of outcomes than were imagined in 1950, but the need for which is clear today.

Britin Bostick is the Long Range Planning & Special Projects Manager for the City of Fayetteville.

A roadmap for creating a complete neighborhood.

BY DANIEL CHURCH

A conceptual vision of transforming the Arkansas River waterfront into a gathering place with water play and recreation.

It seems unlikely that when Jean-Baptiste Bénard de La Harpe first saw “la petite roche” (“the little rock”) at the narrow crossing of the Arkansas River in 1722, he or anyone else could have envisioned it would one day become the heart of a thriving region, adorned with steel-and-glass skyscrapers and home to a vibrant center of government. But as a small trading post at the river’s edge transformed into a center of business for all of Arkansas, Downtown Little Rock was born.

Downtown has seen a great deal of change in its 200-year history. As the state’s most populated city and state capital, it is home to the largest concentration of institutions, cultural amenities and historical locations in Arkansas. It is also Arkansas’s largest employment center, with nearly 43,000 jobs. As the governmental, health care and financial heart of Arkansas, the success of Downtown Little Rock is critical for the success of the entire state.

Like many downtowns, Downtown Little Rock aims to redefine itself in a post-COVID world. Over the last decade, downtown has seen marginal job growth when compared to the rest of Central Arkansas and has seen employers leave for suburban locations. Concerns about safety and homelessness, a lack of quality of life amenities and a general sense of lifelessness are often cited as to why employers relocated. And while the impacts of the post-COVID job market still linger, activity in downtown has largely rebounded back to pre-pandemic numbers. Residential demand is high, with multifamily occupancy over 95%. Retail is thriving in the River Market, Main Street, SOMA and East Village areas. Tourism is strong, with new hotels planned. Most importantly, new investment is underway. The renovation and expansion of the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts in MacArthur Park has created a cultural centerpiece in downtown to complement the Clinton Presidential Center, which is planning its own major expansion. The Arkansas attorney general, in partnership with Moses Tucker Partners, is renovating the Boyle Building at Main Street and Capitol Avenue, saving the oldest skyscraper in Arkansas. New investments and expansion by Arkansas Children’s Hospital, the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and Artscape are just some of the numerous projects planned for downtown. It is an exciting time for Downtown Little Rock, but now is the moment to capitalize on these key investments to catalyze well-planned growth and success into the coming decades.

Having never had a comprehensive plan, downtown’s success has largely been a series of disconnected projects and private investments. In 2023, knowing that a plan for downtown was essential for its success post-COVID, the city of Little Rock, in collaboration with the Downtown Little Rock Partnership, hired Sasaki, an internationally renowned planning and design firm, to complete the master plan. Sasaki has been instrumental in downtown planning efforts around the country, including in Raleigh, North Carolina; Houston; and Greenville, South Carolina. At its core, the Downtown Little Rock Master Plan, which is funded through federal dollars received through the American Reinvestment Plan Act, is a roadmap for city officials, the Downtown Partnership, other

From top to bottom: A conceptual vision of the future of Downtown Little Rock, with new development, improved open spaces, and enhanced connectivity and mobility. A conceptual vision of the new 30 Crossing Park at 2nd Street and Sherman Street.

A GREAT DOWNTOWN IS A SIGNAL NATIONALLY THAT CENTRAL ARKANSAS IS AN INVESTMENT WORTH MAKING AND A TRIP WORTH TAKING.

agencies and private investment to steer decisions and investment over the coming years and decades.

The downtown master planning process began in fall 2023 with a large public meeting and a series of steering committee and focus groups comprised of dozens of downtown residents, business owners, city officials and elected leaders. During this discovery and analysis phase, Sasaki absorbed as many ideas, concerns and aspirations as possible to serve as the foundation for establishing a guiding vision and values. Dozens of potential ideas were workshopped with the public at another round of engagement in December. This prioritization helped inform a more detailed review of the emerging Big Ideas and strategies in February. This last round of public engagement, along with an implementation workshop with the steering committees and city leadership, informed the implementation chapter that anchors the entire plan. A draft of the master plan was released to the public in May 2024. Comments from the public will lead to updates and revisions, with the final plan slated to be adopted by the city of Little Rock’s Board of Directors later in summer 2024.

Throughout the nine-month planning process, Sasaki received thousands of public comments across three surveys, seven public meetings, numerous pop-up events and dozens of conversations with downtown stakeholders. Key themes began to emerge around open space, mobility, economic development, urban design, and culture and institutions. These themes helped establish the Big Ideas that form the plan’s foundation:

• Downtown should be a tapestry of neighborhoods

• Downtown’s open spaces and trails should serve as rambles to the river

• Reimagining mobility should loop, stitch and reconnect people from where they are to where they need and want to go

• Culture is a catalyst for placemaking and growth

Each of these bold and aspirational ideas serves as a visionary guide for investment and infrastructure. The plan outlines roughly 10 strategies for each Big Idea, including potential projects, partnerships, programs and policies necessary for success. For each strategy, there is a clear summary for when implementation should occur, who is responsible for its implementation and how each strategy will be funded. Of the broad-reaching 44 strategies, a few key ones are worth noting and have the opportunity to be immensely transformative.

The first, and most critical, is to increase the residential population of downtown. Downtown Little Rock’s residential density is up to four times less than comparable cities such as Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Richmond, Virginia. More population means more activity, more retail, more vibrancy — all of which change perceptions about safety

From top to bottom: Engagement with the community has been essential in shaping the ideas outlined in the Master Plan. The removal of the off-ramps through the reconstruction of Interstate 30 presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to create a premier park in the heart of the city. A conceptual vision of a redesigned LaHarpe Boulevard as a slow-speed two-lane parkway will transform the riverfront and improve connections from downtown to the water.

and lifelessness. But in order to attract more residents, it is critical to build more housing, which will require new financial incentive tools to enable denser construction types to be built. The plan outlines a series of strategies, including the creation of a new tax increment financing district, to help incentivize new development.

Although housing demand is high, it is also important to improve the experience of living and working downtown. Throughout the process, the public highlighted the desire for downtown to more actively embrace and celebrate its riverfront. The Arkansas River is the lifeblood of the city, and yet, the city largely turns its back to it. Fixing this will require a series of infrastructure and open space enhancements to change that dynamic. One key strategy is to reimagine La Harpe Boulevard as a two-lane parkway that meanders through Riverfront Park instead of dividing the city from the water. Another key strategy will be to redevelop public land near the water into housing and retail. Lastly, there exists an incredible opportunity to transform the 18 acres left over from the reconstruction of Interstate 30 into a jewel of a central park for all of Central Arkansas. This new park should be an oasis of activity that connects downtown to the riverfront where new opportunities for water recreation could occur. These new assets, combined with new daily needs amenities such as a grocery store and other retail, can turn downtown into a complete neighborhood.

The plan also outlines strategies for other areas of downtown. West Ninth Street was once Little Rock’s Black Main Street that was fragmented by the construction of Interstate 630. New streetscape enhancements, alongside a proposed Black Entrepreneurship and Innovation Hub operated in partnership with local institutions such as the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center, could transform West

Ninth into a vibrant new neighborhood anchoring the southern end of downtown. Capitol Avenue should be reimagined as a two-lane vibrant ceremonial street that connects the heart of the urban core with the state capitol. Regulatory, zoning and development approval process changes should be made to expedite and incentivize downtown development, and many of downtown’s one-way streets should be changed to two-way traffic flow.

A full draft of the master plan can be found at mp.downtownlr.com.

The success of Central Arkansas is contingent on a thriving urban core that serves as the beating heart of the region. A great downtown is a signal nationally that Central Arkansas is an investment worth making and a trip worth taking. And while the strategies outlined in the master plan will help Downtown Little Rock grow and thrive, they will not happen overnight. They will require long-term support from the broader Central Arkansas community. It is critical for everyone to become an advocate for the ideas in the plan that are important to you, and, more importantly, to become an advocate for downtown. Support downtown restaurants and retail, and encourage out-of-town visitors to take a gander at its museums or stay in the hotels. Your support and the guidance of the master plan can unlock Downtown Little Rock as a one-of-a-kind urban experience for which everyone wants to be a part.

Daniel Church is an urban planner for Sasaki Associates, the firm hired by the city of Little Rock to complete the Downtown Master Plan. Daniel lives in Denver, and is a Little Rock native and a graduate of Central High School.

If walkability and connectivity are the keys that can unlock the potential of a downtown corridor, an urban neighborhood or even an entire region, one would be hard-pressed to find a key ring that jingles louder than the Central Arkansas Regional Greenways Master Plan. This plan, which will connect four counties and 19 communities through an expansive system of trails, will ultimately provide an active transportation greenway network for the heart of Arkansas and bring a wealth of potential to the area. By incorporating existing trails and proposing miles of new ones, this plan embodies the concepts of new urbanism by encouraging walkability, connecting older neighborhoods to new and unlocking economic potential for trail-oriented developments while allowing each community to promote their individual identity. Metroplan understood this potential, which is why the federally designated Metropolitan Planning Organization for Central Arkansas committed to a substantial investment in developing such a network in early 2020.

Daniel Holland, Metroplan transportation project manager, says Metroplan has seen firsthand what successful trails can do for communities. Through fact-finding trips throughout a variety of regions with successful trail systems, the picture became clear. There was an opportunity to realize the benefits of providing residents with more choices in transportation.

Over the span of two years and through a pandemic, Crafton Tull and Toole Design worked to lay a foundation for what this greenway plan would look like. Early in the planning process, the project team identified eight guiding principles that informed the route development process to create a unified network across the region. These principles state that each network segment must be transportation-focused, physically separated, inclusive, consistent, safe, context sensitive, high quality and well connected.

Ultimately, the Central Arkansas Regional Greenways Plan identifies approximately 222 miles of trail network at an estimated cost of nearly $280 million. Metroplan officially adopted the final report in May 2023, which identified six specific corridors that will each connect several communities and provide both recreation and the option of active transportation.

These six corridors include the Southwest Corridor, already in development before the greenways plan, which uses an abandoned railroad corridor to connect Little Rock Central High School to Hot Springs National Park and connects Little Rock to Shannon Hills, Bryant and Benton along its path. The Central Beltway Corridor navigates the oldest blocks of downtown Little Rock westward along the Interstate 630 corridor to newer developments in West Little Rock. The Northwest Corridor departs the Arkansas River Trail and traverses White Oak Bayou through North Little Rock to Maumelle before continuing north through Mayflower to Conway, navigating both urban and rural areas. The Northeast Corridor connects communities and destinations from the Arkansas River Trail in North Little Rock through Sherwood, Jacksonville, Cabot, Austin and Ward, providing a seamless pathway from one city to the next. The East Corridor to Lonoke and Southeast Corridor to Wrightsville function in a similar fashion through predominantly rural areas and

result in notable portions of their corridors consisting of signed routes with critical separated facilities proposed in areas of dense population.

The greenways traverse the varied landscapes in both urban and rural contexts of the region, with views of the highest peaks and the soothing sounds of rushing water present along every corridor. Each corridor has its own character and major destinations, which not only provides individually for each of the segments, but also an option for those looking to use the trail system for recreation.

What started as an ambitious vision is becoming reality, with several planned segments in design and some in construction. The Southwest Trail from the Clinton Library to Sixth Street is under construction, while segments in both Pulaski and Saline counties, including Benton, are under or beginning construction. Along the northeast corridor, Sherwood, Cabot and Austin have projects either under design or bidding for construction. Segments of the East Corridor and Southeast Trail are also in development.

What does this mean for Central Arkansas? Simply put, this means that the communities in the region and the landscapes between them could look very different in the decades ahead. Greenways may breathe new life into old neighborhoods and expand opportunities for healthy lifestyles and recreation.

Not only will the implementation of the greenway change the landscape, but it also holds the potential to spur economic growth for areas along this network that might have never seen an avenue for such. Forgotten areas may one day be bustling with walkers and joggers alongside people on bicycles. The potential for further placemaking and trail-oriented development along the greenways can be transformative for neighborhoods, adding amenities not currently available for several communities throughout the network.

There is also the potential for an improved quality of life in general. Central Arkansas has been automobile dependent for decades but owning multiple cars is not always an option for residents. A connected system of greenways provides safe and direct paths to major employment hubs, grocery stores and essential services in the absence of a car. The opportunity for socialization is another benefit of a connected system of this nature. As the greenway weaves through housing, parks and retail hubs, travelers will stop to enjoy the scenery, grab a cup of coffee or window shop. This is where we run into our friends and neighbors, fostering those important community connections.

The vision has been cast and funding has been outlined. Now is the chance for communities to use this opportunity to partner in the implementation of this network. With a plan for a system such as this for Central Arkansas, Metroplan has ensured that there will be active transportation projects continuing for decades to come, and instead of communities being left behind, they will be moved to the forefront of quality development in the region by handing them the keys to connectivity and walkability.

Julie Luther Kelso is a landscape architect and city planner serving as the Vice President of Planning with Crafton Tull.

Born out of the evolution of the real estate and hospitality industry, “short-term rentals” refer to lodging accommodations rented out for (typically) less than 30 days. While they aren’t new, companies such as Airbnb and VRBO popularized the rise of the sharing economy, which resulted in the now commonplace practice of renting out spare rooms or entire properties to travelers and temporary visitors.

During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, short-term rentals became even more mainstream, due to the flexibility they provide for travelers and the ability to social distance.

Across the country, short-term rentals have come under debate. They come with a list of positives and negatives. They potentially drive tourism and offer flexible accommodations to travelers.

However, they can also eat up the viable housing supply and wreak havoc on local infrastructure. The largest issue, perhaps, is each community has its own needs, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach to regulation. The Arkansas Municipal League (AML) notes that cities, towns and communities in Arkansas are tackling short-term rentals in various ways. General Counsel and Legislative Director John Wilkerson notes that part of the debate involving short-term rentals is about investment. “If you’re a long-term renter, you’re at least investing yourself into the community,” he said. “If you’re a short-term renter you’re just there for a weekend.” Plus, the amount of short-term rentals in a municipality can cause issues with the available housing stock.

“There is a housing shortage,” AML Executive Director Mark

Popularized by platforms like Airbnb and VRBO, short-term rentals have reshaped the housing market prompting Arkansas cities to address regulation in various ways.

Hayes said. “And whether it’s in every single community or not, I think, generally speaking, affordable options have shrunk for people.” While Hayes notes that there are multiple factors driving this issue, he believes it’s still important to take note, especially in tourism communities. “That’s a balance as well, you can’t provide those entertainment tourist services if people aren’t able to afford to live there long term,” he explained.

The strain on infrastructure can cause pain points, as well. Is the city well-poised for an influx of visitors?

The AML has to consider all parties involved when heading into a legislative session. Property rights are king in Arkansas, and property owners expect a certain level of freedom to use their property as they see fit. “We don’t want to regulate things out of existence, by any means. But we do need to have the ability to be nimble and deal with the needs of our citizenry,” Wilkerson said. “It’s a very careful and delicate balance.”

Regulating short-term rentals at the local level goes a long way. Bella Vista, Hot Springs and Bentonville, for instance, all take different approaches.

Bella Vista Mayor Jack Flynn believes short-term rentals have a positive impact on his community, especially because the area lacks traditional hotels. “People want to come to visit, sometimes they’re even visiting relatives but they don’t have enough room in their house,” he said. “I think short-term rentals have an economic effect, definitely.” Flynn also notes that short-term rental properties in Bella Vista have improved the housing stock, as people want good reviews and street appeal matters.

That doesn’t mean that Bella Vista hasn’t had its own issues with citizen concerns, however. “They worry that if there are too many [short-term rentals] in an area, then it will lose that neighborhood feeling. They don’t like that idea of having a different group of people there every weekend as opposed to neighbors they know,” Flynn said.

The mayor added that right now, the main goal is to ensure the amount of short-term rentals doesn’t outrun the percentage of available housing stock.

Hot Springs has long been a tourism hot spot, thanks to the national park, colorful mob history, and unique blend of art and culture. Hot Springs City Manager Bill Burrough explains that while the Spa City is a destination for visitors, residents call the place home as well. “The board set a cap

on short-term rentals within the city at 500. If it’s a horizontal property group or condominium outside of our regulation … we don’t regulate those,” he said. Burrough says city management worked on the short-term rental ordinance for more than a year, conducting meetings with stakeholders and capturing citizen input. “The ordinance we started with changed over time as we learned more about short term rentals and how they impact our city and the character of our neighborhoods,” he said. For instance, a few months ago, the city lowered the short-term rental cap to 400 but honored all those approved at the time, with 425 licenses now active.

Main complaints from citizens regarding shortterm rentals involve garbage pickup, parking and occupancy. Hot Springs took action by regulating how many people can stay overnight in a rental: two per bedroom. “The number of people that can be on the property is 50% more than what is allowed to sleep overnight,” he clarified. “That comes into effect when we see a complaint. Part of our ordinance requires a local contact to be available 24 hours a day, and they have to be able to respond to a complaint within 60 minutes.”

Burrough pointed out that even though there is an ordinance in place, it’s subject to change again if the community deems it so. “Being a resort community we have to be cognizant of the fact that short-term rentals are something that people look for when they travel as well as staying in our hotels. It all goes back to that balance and finding what works for your community,” he said. “I think there’s a place for them.”

Bentonville offers individuals many reasons to visit, from renowned art institutions to Walmart HQ and quality trails. Considering this, Bentonville has a plethora of short-term rentals. “Bentonville does not have specific regulations for short-term rentals,” Bentonville Planning Manager Sherri Kerr said. She notes that common complaints include parking, noise and property maintenance. “Bentonville city codes regarding those issues apply to all property, including those being used for short-term rentals,” she said. “Bentonville enforces existing regulations particularly related to nuisance issues to help ensure that short-term rentals remain good neighbors.”

Instead of direct regulation, the city offers programs aimed at encouraging neighborhoods to create a sense of connection and safety. “We offer a Great Neighborhoods Program designed to build bonds between neighborhood residents, foster communication between the residents and city, and empower residents to enhance their neighborhood all to help create strong, stable neighborhoods,” Kerr said.

No matter the municipality, it all comes down to specific needs. “If I was a mayor and city council member, I would want to have a lot of information,” Hayes said. “The key is making sure we listen very carefully to what the residents of the city say.”

Icut my teeth as a home builder around 2012 in Benton. For years, all across the United States, subdivisions were rolled out with finished streets and utilities but were left vacant of homes. I didn’t know it at the time but I was spoiled. Those empty lots were cheap, labor was cheap, materials were cheap and interest rates were much better than they are today. Additionally, subdivisions have an advantage over infill development because of their Bill of Assurance that makes the lion’s share of decisions for you. With “copy and paste” style house plans, I built 50 homes using just three different sets of plans. The hardest part of my job was figuring out how to build them with the least number of windows and the smallest set of cabinets possible. They are the two big-ticket items that appraisers pay no mind to.

Just a couple of years later my girlfriend and I were planning on getting married and wanted to build a home together in a walkable community that was a little closer to the action. We found the empty lot that our home stands on now, and it was a short walk to the ice cream shop and several restaurants, one block and walking bridge away from a dog park and fine arts museum.

Our neighborhood was almost entirely unknown; even the residents didn’t know our name. Between redlining decades earlier, white flight, gang violence and even a tornado, half the neighborhood, I’d say, was vacant land. But the bones were perfect and the neighbors that were still here were good ones. They had seen it all and were glad to have new life being breathed back into their streets.

It was hard starting out because we didn’t have the appraisals to support the sales prices that new construction labor and materials demanded. We stretched and fought and asked more of appraisers than they were used to and slowly made a chain gang of reliable comps for us to build on.

Our buyers were not completely convinced yet, either. The neighborhood still had a reputation, and the perception wasn’t great. There were some homes we couldn’t sell or rent, but Airbnb was beginning to be a thing, so we tricked people who didn’t know any better into staying in our neighborhood and continued to build homes so that we could “literally” change the perception.

Many of the lots were developed over a hundred years ago. The lot sizes were replated through some handshake agreement, leaving many just 50 feet deep, with 25 feet setbacks off the front and back that left us with zero feet to build on. One lot was just 32 feet wide and 62 feet deep. So, we built a tiny home on it of just 270 square feet.

Shotgun homes — homes that are just 12 to 18 feet wide in many cases — once lined our streets on lots just 25 feet wide. It’s not often you will find two lots the same. So, you have to think through a new house plan every time. Many times, due to modern-day zoning, these empty lots, while accommodating a home just a few years earlier, were now undevelopable or “un-conforming.” Which meant you would have to spend over $1,000 usually and notify all your neighbors in a 200-foot radius and wait a couple months or three to find out if you could build a home on it or not.

Between banks, appraisers, persuading buyers, crime and maneuvering the city, it sometimes feels like you’re fighting for something every day before you even get to have it out with your subcontractors and vendors. The politicians do everything they can to help, but there are new problems every single day. We burn

From left to right: Apartments line Pettaway Square, facing inward and fostering community. A popular shop, Paper Hearts Bookstore, is open for business on 21st Street. The popular foodtruck Smashed N’ Stacked serves up grub alongside newly opened microbrewery Moody Brews.

“WE GET TO TURN OUR IMAGINATIONS LOOSE, WHICH RESULTS IN SOME REALLY INTERESTING ARCHITECTURE.”

—MICHAEL ORNDORFF

through our political capital before the ink on the check is dry.

But, 10 years later, my wife and I are raising our two kids, who are 3 and 5, in a neighborhood that’s right next to three parks. We still walk to go out to eat, grab something from the convenience store and even get groceries sometimes. But now we get to do it on nicer sidewalks that are mostly shade covered by the trees we planted.

We have regular farmers markets in two different directions just a short walk away. The owners of the locally owned businesses here know my children by name. They get to grow up watching people chase their dreams and are exposed to a culture rich in different ideas and lifestyles.

We don’t drink and drive here because our locally owned microbrewery, Moody Brews, is literally in the middle of our neighborhood. You can skip the car entirely and walk home. Our coffee shop, Pettaway Coffee, has a hard time competing with the speed of 7 Brew but since it’s basically next door, it’s still quicker. And it’s a lot more enjoyable to get out of your car, and say “hi” to the barista or a neighbor along the way.

While constructing Pettaway Square, a neighbor who is a barber came to me with the idea of opening up his own shop called Blue Water. He’s thriving now with two employees after being in business for over a year. If that’s not enough, we have a locally owned bookstore called Paper Hearts, a shared studio space called The Commons@ Pettaway, a Nail Salon called L’Etoile and a hair salon called Honeycomb Hair Lounge.