AVENUE 2022

First published 2022 by The University of Sydney Funded by the University of Sydney Union

© Individual Contributors 2022

Foreword © Angela Xu and Frankie Rentsch

Afterword © Ibi Khan and Iris Yuan

Layout © Frankie Rentsch, Angela Xu, Angel Zhang and Trinity Kim © The University of Sydney 2022

Images and some short quotations have been used in this book. Every effort has been made to identify and attribute credit appropriately. The editors thank contributors for permission to reproduce their work.

ISSN: 2653-6978

AVENUE: The Journal of the University of Sydney Arts Students Society

Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below.

Fisher Library F03

University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia

Email: sup.info@sydney.edu.au Web: sydney.edu.au/sup

Cover by Angel Zhang

This edition of AVENUE was edited, compiled, and published on the occupied lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. We acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded, and that the occupation is violent and ongoing. We give our deep respect and solidarity to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and to their Elders, past, present, and emerging.

This land always was, and always will be, Aboriginal land.

To new beginnings.

Angela Xu Frankie Rentsch

Ibi Khan

Iris Yuan

Creative Directors

Angel Zhang

Trinity Kim

Lead Editors

Melody Wong (Essays) Amy Tan (Poetry) Janika Fernando (Prose)

Teresa Ho Daniel Graham Sonal Kamble Nicole Zhang Natalie Rathswohl Sandra Kallarakkal Niamh Elliott-Brennan Christine Lai Nafeesa Rahman Simone Maddison Julie Nguyen Yasodara Solomiya Sywak

Angela Xu and Frankie Rentsch

Kamyar Murphy

10000hats

Janika Fernando Zoe Morris David He Niamh Elliott-Brennan Christine Lai Lucy Bailey Nishta Gupta Christine Lai

A E Leighton

Frankie Rentsch Iris Yuan Ya sod ara

Ellery McKelvie I bi Kh an

Atoc Malou Ibi Khan

11 15 18 19 27 28 32 34 35 36 38 40 44 45 53 54 63 64 77

Foreword

I couldn’t tell you what it means (but it meant something to me)

Transfiguration

Queens of the Sea

Song of the Moon

By the Sea

The Laurel Tree

The Two Times I Almost Set Fire to the Shed Strawberry Legs

Split Screen Self

Buzzcut Killer

The Dance Cunt Connoisseur

Hawaii Five-0, Cultural Hegemony and Copaganda: a Critique LEFT

The War Parts, Anyway, are Pretty Much True: Science Fiction as Historical Fiction in Slaughterhouse Five

Shadow Party Boys Chaos

Ibi Khan

10000hats Teresa Ho Lucy Bailey Jem Rice

Iris Yuan and Ibi Khan About the Editors About the Contributors

78 82 83 89 90 93 94 98

The Urge to Cry in Public Places Chair

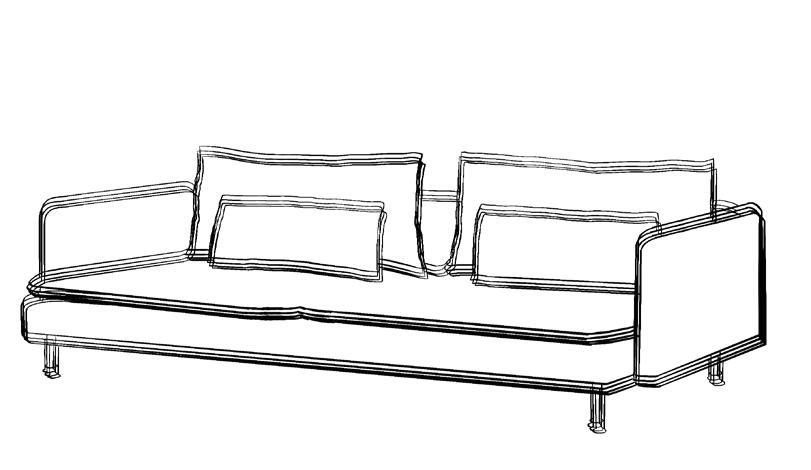

Moving Under the Shadow Soderhamn Sanitiser Afterword

Welcome to AVENUE 2022. We invite you to step into a world, new yet familiar, where your heart yearns for loves that have come and gone, time and space bubble and melt, and avenues for exploration appear, superimposed onto well-trodden paths. Come share in the many talents of our contributors, artists, and editors; look through these pages onto landscapes awaiting your arrival.

You may have noticed that this journal bears a new name. First published in 1918, the Sydney Arts Students’ Society’s annual journal has taken on many names in its lifetime. In 1938 it was named ARNA; it would remain so for the next 83 years. According to the editorial in the 1938 edition, this name was taken from an unspecified Aboriginal language and is a reference to a ‘sun-god who gave laws and culture to mankind.’

Having discovered this troubled history in 2022, we realise that this name was likely stolen without permission or consultation. As a journal that prides itself on being a place where all can have a voice, we could not continue without acknowledging this past and changing our name. A more detailed tracing of the history of the name can be found on our social media pages.

Our new name is AVENUE. AVENUE reflects Eastern Ave, where student life teems and flourishes. It also refers to avenues of thought, pathways which our minds and creativity can wander down and explore. Finally, it is a road forward, towards a future which is inclusive down to every last word, a road where we can keep our past in the rearview mirror, never forgetting, and always striving to do better.

What you’ll read in the following pages perfectly encapsulates these

meanings. Peek into the lives of a pair of sisters from Sri Lanka, set to the backdrop of chugging trains and daunting waters. Challenge yourself with the cultural critique of a beloved cop show and take another look at your ikea sofa.

In a journal of old and new, bask yourself in funky form, melodic prose, and subject matter pulled from every corner of a creative’s fever dream. The amount of diversity and talent we have had the privilege to publish this year is simply indescribable and we hope you enjoy the journey.

However, we can’t let you go without thanking the incredible people who have created this journal.

To our contributors, thank you for sharing your talent with us and for keeping the long history of this journal alive. Your bravery, creativity, and unfailing honesty paint the landscapes of this journal in the most vibrant colours. To our editors, you are the lifeblood of this journal - thank you for your hard work, innovation, and insights. Special thanks must also go to our Creative Directors, Trinity and Angel, and our General Editors, Iris and Ibi. We couldn’t have done this without your work, experience, and wisdom.

Finally, as the last journal of 2022, we would like to thank the 2022 SASS team, for supporting our portfolio over the past year. We are so thankful for your encouragement, love, and tireless dedication.

Now, lovely reader, welcome, and enjoy.

Over and out, Angela and Frankie

There’s water painted over the earth as far as I can see. It washes onto the sand with every wave, filling in all the shallow footprints. When a stick drifts in at just the right spot, it becomes a gravestone, a record of whoever had walked over it, the water burying, carving the memory into the sand. The white noise of the wash breaks the beach open, pushing around shells and seaweed and stones.

There are leaves drooping from my hands, dark green and wrinkled and tangled around my arms and my legs. Their spines trace my veins and arteries, and when I try to speak the air comes out scratched.

I’m holding the plant tight, trying to cut it open and rip it apart. I want to hold it up against the sky and stretch it from edge to edge.

I haven’t been here at night before, it feels jarringly alive, even though there’s nobody else on the sand. I can’t see anyone on the street either, or in the water, or on the rocks at the north end of the beach where people go to swim on New Year’s.

***

The last time I came here was in April. It was still warm then, I think that Ava had organised a picnic in the park next to the beach. I was distracted by the noise of detail. The sun warbled between us, the grass was warm but just comfortably warm, and soft air swept around us and filled the branches of the tree behind me. The sky was light blue, vast and bright but not blinding, it draped over the park, and Reide had made this coconut and almond cake, one I’d given him the recipe for a few years ago, and he was holding one of his hands in the other, but it wasn’t out of nervousness, he’s not the type to be nervous, and

I couldn’t tell you what it means (but it meant something to me)

There was a plant growing in my chest. It sprouted out of my mouth and my nose and my eyes and sank in with the grass. Bright green leaves stretched out towards them, one unfolding every few seconds, spreading out and surrounding everyone there. Yellow flowers burst out of its stem and brushed against the leaves.

One of the branches caught in Reide’s hair. He brushed it out and laid it on the ground. He was smiling, and I hoped. His eyes turned towards me for a moment.

‘Do you wanna swim?’ It didn’t feel like Reide had said it aloud, but I heard him clearly.

‘I don’t know,’ I replied. The plant lined my veins, rootstalks tracing underneath my skin. ‘Won’t it be too cold?’

‘It’s only April,’ he said, ‘the sun hasn’t been out for so long, we should make the most of it.’

Light filtered down through the tree branches, falling on his shoulders and spilling onto the grass.

I smiled, half of my mouth curving up more than the other, and reached out to hold his hand. My hand weaved into his and I could feel his joints and tendons and bones under my skin, and his hand pulled me through the grass and the ground opened up around us and everything around him drowned out and the blue sky expanded out farther with every second and

The leaves wrapped tighter around me. The plant twisted between tree roots and burrowed into the earth. My words became part of its structure before I could say anything. Blades of grass pierced from my fingertips and anchored my hands to the ground.

I stopped hearing whatever Reide was saying and he stood up and walked towards the water.

I was lying on the ground and the vines were wrapped around me. Everyone was gone now. The leaves contorted and coalesced and they were choking me. My knees were twisted to the side and it stretched around my limbs and it was in my throat. Half submerged in a dark green pool, its water clutching to my skin and piercing it, seeping in. The water kept filling in, drenching the soil. The longer I lay there the heavier its branches became. How long had it been? The sky darkened. Its weight held my tongue to my jaw and pressed against my skin.

***

There’s water painted over the earth as far as I can see. The plant is a darker shade of green now, twisted and curled in on itself. It drifts forwards and backwards and forwards and drags sand around next to my feet. There are still yellow flowers tangled in, faded and pale and brittle. My fingertips have toughened under the leaves, darkened and sunken onto their bones. Somewhere between the grass and the sand it became seaweed, and now it loops around my body and clings to me at the edge of the beach. Every time the water washes over it, another piece breaks off, and the seaweed sinks out into the ocean, waves pulling it apart.

There aren’t any clouds in the night sky, just an unending darkness so thick that the horizon becomes a haze. It’s like looking over a cliff, trees so far off in the sky that they blend together. It’s too distant, too incomprehensible to see anything, no canvas to hallucinate on, no blank wall to cast shadows on. The sky pulls the roots from my skin, writhing out from my throat and my veins.

I don’t look at the holes it leaves on my skin, or the faint grey line on my forearm, or the cut on the bottom of my face. I couldn’t tell you what they mean.

And the waves bury the leaves in the sand, every stem and every spine sewn into the beach. A stick drifts over the sand as I turn around and walk home.

December 26, 2004 Galle, Sri Lanka

All I could remember was the surging of the waves, like someone had abruptly opened a door that led to darkness and doom. The sweat that clung to my dress before the hairs rose on my arms, amidst the frigid air and the damp odour of wet carriages. All I could remember was the loud whistle of the train before it became a deafening cry as it tumbled over. We formed a communal body on the carriages, brown bodies brave and strong – yet those bodies were tumbled over soon too. All I could remember were the green leaves whispering against the hot wind before it turned into a high wave of water, crushing us, engulfing us as if we were nothing but rocks.

***

My house was ivory. Ammi,1 Thathi,2 Nangi3 and I were the lucky ones, compared to the poverty in the slum parts of the island and humble homes in the villages. You could emerge from slumber and gaze out your window at the golden sand. See where the sunrise meets the sea, as blue as the sky. Galle.4

Our one-storey home was long and curved, the white pillars lining the baby blue double-door entrance. The red clay tiled roof provided shade for us on the open-sided pavilion. There was a single lamp dan gling from it. In the darkness of night, we could immerse ourselves within its glowing light.

Our bedrooms were spacious, where each one was sacred, and within, our hearts were unfolded by each other’s presence and the serene

1 ‘Mother’ in Sinhala

2 ‘Father’ in Sinhala

3 ‘Younger sister’ in Sinhala

4 City on the Southwest Coast of Sri Lanka

views. The largest, where the window invited the eyes into the green vistas of rice paddies, belonged to Ammi and Thathi. Nangi’s bedroom had a veranda, overlooking our long swimming pool. We spent most of our time together there. As we splashed each other, Nangi’s eyes sparkled with joy.

‘Ane meh, yanne Akki!’5 she squealed.

I splashed her. Again. It was within these moments – her long, jet black hair rising and glistening under the sun, the particles of water floating everywhere in the air, and hearing her giggles echo – that I felt at home. She was home. The kind of home that is a bubble of water, emerging and reemerging as she was from the body of water we were under. We swam in and out, our red-brown ochre skin glowing to become a blessing as we synchronised our movements under the sun.

Even though she annoyed me, she was my life. We pretended that we were queens of the sea. ***

The familiar fumes of turmeric, cloves, and garlic lingered in the air. One only had to hear the clanging and banging of pots and the smooth stirring of the spoon to know my mother was making chicken curry. Rice was breakfast, lunch, and dinner. The stone steps at the back of the kitchen led to our garden. Our garden contained an assortment of greenery, the finest spices for our curries.

‘We are visiting your cousins today. The Colombo6 train leaves soon. Ikmanin kanna!’7

‘Yes, Ammi…’ Nangi and I nodded, rubbing the rheum off our eyes, tired from the early rise. *** 5 ‘Go away, Sister’ in Sinhala (playfully) 6 Capital city of Sri Lanka 7 ‘Eat quickly’ in Sinhala

Colombo was the main city of our island. Our cousins resided in this city, where large shopping centres beamed with bright lights. Nangi and I loved shopping there, basking in its contrast to the natural atmo sphere which penetrated our home. My family and I had to catch the only railway train in the city: Queen of the Sea.

Elongated and embodied in red, the train had a rusty exterior, as if it had emerged from the ancient ruins of our island. The train’s whistle and the wheels skidding screamed. Puffs of smoke floated gently like clouds into the blue diamond sky. Each carriage was marked by a golden number and open, rectangular windows.

Our arms and legs brushed against the other passengers who were swarming like a sea of fish. My palms were sweaty, and I started clenching my hands into fists to remain strong amidst this scene. I stood with Nangi in carriage one, while Ammi and Thathi managed to find a seat in the same carriage. Nangi and I leaned against the walls, watching the greenery and our house far within the fields fade away into a body of deep blue. ***

‘Aiyo,8 I am so bored!’ Nangi exclaimed. She edged closer to the train door, which was wide open, stretching her arms and legs outside as the breeze gently touched her face.

‘Come back, Nangi!’ I tugged her inside.

Before she could whine, a loud roar echoed from the village our train was racing past. Telwatta.9 At first, we thought it was nothing. But then, the roaring grew louder and louder. My eyes met Nangi’s and trav elled beyond the carriage for an answer. Droplets of water landed on our foreheads and the wind was as heavy as our pounding hearts.

The railway man screamed, and everyone in the carriage scurried around helplessly. We shut the doors and grappled for safety by holding

8 Sinhala term to express dismay, regret and disappointment

9 Small populated, Southern province in Sri Lanka

the walls, the bars and standing on the seats. Nangi and I held onto each other, clinging to each other’s dresses. The wall of water cloaked the train. One by one, waves surged through the carriages, sending shivers through our bodies. The train jerked violently to the side. We held our breath with all our might. Downwards, the train tumbled over the railway tracks as if a giant had pushed it off.

***

Our dreary eyelids blinked us from the fatal sleep. Our bodies were sore from the minor cuts on our arms, and our trapped legs. We coughed as the fumes of smoke circled the air. Nangi and I emerged from landing face-first on the carriage floor and rummaged our way out of the wreckage, one arm, one by one, and one leg, one by one. But the people around us – their eyelids remained shut.

‘Ammi? Thathi?’ our voices echoed.

Not far from us a ragged blue shirt and dress dangled off a tree…

May 26, 2013 Sydney, Australia

The cold wind slapped our faces on a fine Monday morning, as Nangi10 and I ambled our way down the small flight of stairs and across the vibrant walkway near our home. So blue, so fresh, and so salty was the body of water that flowed downstream on our walk. As fitness fanatics cycled past and a family of ducks sunbathed on the tranquil grass, Nangi fidgeted with her long, blue navy skirt. I fixed up the collar of her blouse, untucking it from under her blazer. She was in Year 12 now. Her final year, and yet, I somehow felt we were both so young, so delicate, and still so lost. After many years, our hearts now resided in the city where ‘eels lie down’. Parramatta.

The sea creatures, monkeys, and hands painted on the ground waved at us, as my winter boots and Nangi’s black school shoes clicked cleanly against the beautiful footpath. The footpath was rich in its history

10 ‘Younger sister’ in Sinhala

and these artworks of bright yellow, blue, and red, all beautifully crafted by Jamie Eastwood, one of the Ngemba descendants. The Indigenous artworks reminded me of our now distant home, our own teardrop shaped country rich in history, its culture, and its people. Family. Well, the family that was left. I turned to look at Nangi, her face resolved and ready to battle the Monday of today. She didn’t seem lost and nostalgic at all, like I was.

We headed closer to the second flight of stairs near the archshaped Lennox Bridge that extended beyond, as did the river. As we emerged from the small flight of stairs and reached our bus stop, Nangi motioned her hand and the bus haltered, its engine moaning and heaving as if the bus too was dreading Monday morning.

We boarded the bus. It was swarming with people as usual and the claustrophobic air tightened my chest, as if a metal wrench were gripping it. I inhaled and exhaled, as I held onto the yellow handle railings that dangled from the ceiling and silver poles above.

Inhale.

Time is of the essence. Time can be akin to a river, flowing relentlessly and endlessly until before we knew it, time had swum by with both its hands plunging into the abyss.

But time could not take away my pai–

The bus came to an abrupt halt at Westfield. The last stop. ‘Akki!11 Hurry up, we’re going to miss the train!’ Exhale.

She tugged the woolly sleeve of my bright yellow coat as we bolted from the bus, down the escalators to the underground flow of shops, past Opal card machines and train times flickering on screens, and most importantly, bodies of people who had places to be and simply amazing lives. Lives.

11 ‘Older sister’ in Sinhala

This train will now stop at…… Lidcombe.

The whirring sound of the speaker echoed these announcements, as Nangi and I sat in the open part of the carriage, because everywhere else was full. She pulled out her laptop, and started working on her Modern History essay while my eyes wandered to the clear doors, where I could see flashes of stations, buildings and people. The train halted and jolted between intervals, reminding of me of a time not so long ago, when –

Nangi tugged on my sleeve and started edging her laptop screen towards me. She wanted me to read her essay. I couldn’t tell if there was any resonance in her eyes on that fateful day, but it didn’t seem to bother her. I mean, her essay was really good.

This train will now stop at…… Strathfield.

And before I knew it, she was gone. Well, for six hours and a half at least. She waved goodbye, her back turning as she faced the doors ahead, moving forward, while I was alone, waiting to spend yet another day at university.

This train will now stop at…… Redfern.

Time kept moving, like a body of water flowing forward forever and ever with no return. ***

I was done for the day and heading towards the station. The night wore its cloak of blackness and I could see nothing but a few dim lights lining the walkways, and cars flashing their red and yellow headlights on the roads. Mahansiyi,12 I sighed, adjusting my shoulders to the uneven straps of my backpack. My beanie shielded my ears from the coldness of life, the coldness of the weather and the coldness of pre-exam stress –12 ‘Tired’ in Sinhala

and my own insecurities about finding love and hope in all this mess.

Inhale. ‘You have to keep moving, Duwa,13 for our sake…’ Thathi’s14 words echoed within my mind.

Keep moving. Exhale. Puffs of smoke from my mouth floated in the air. At the diagonal and multi-way crossing, I wondered to myself what life was. How life was a constellation of mere moments that can happen in an instant. How life could change so suddenly like a body of water that turns from blue to grey and then becomes murky. Never-ending, always rushing onto the next chapter, leaving us with the cutting remains of yesterday… ***

I was sitting in the open area of the carriage again. The flashes of buildings, people and stations were engulfed by the night sky and its many shadows. I could see nothing, but I could feel the warmth of my father’s voice. My mother’s. I could feel the breeze of the palm trees from the beaches I once knew, the texture of the sea shells I had collected over the years, which to this day still lay on my dresser. Galle. The name, which forever lays ingrained in the back of my mind, because I cannot forget it. Because I carried each of these moments like someone who carries photographs in their wallet of memories that mean so much to them.

‘Just keep moving, my Duwa.’

‘Karunavanta vanna.’15

‘Study hard, we want to see you thrive. Both of you.’

13 ‘Daughter’ in Sinhala 14 ‘Father’ in Sinhala 15 ‘Be kind’ in Sinhala

This train will now stop at…… Strathfield.

My sister entered the carriage, her dreary eyes meeting mine, with a slight smile of reassurance. We both sat together as time swam and as the train was seeping through many stations until we reached the end of the journey. Maybe Nangi and I didn’t choose to hide away the pain, but instead have chosen to embrace it.

The body of water was flowing.

Always.

It is a clear night. I am learning to drive and my mother is sitting next to me. I have almost finished my hours, so she tells me I can drive wherever I want. We drive around Marrickville for a while, and stop at the traffic lights near the library. ‘Look, up there!’ she says. Right above the roof is the biggest full moon I have ever seen. It is beautiful.

Did you hear me, girl, when I scaled high atop the pillars of the Earth white as bone and shiny as a sclera?

Did you see me when the sun caught me in his mathematical grip and shaved me down until I was a ‘0’?

I come from the shards of your Earth and know its pressure points. I can make the sea dance –a marionette, a maenad. I glided, disk-like, across its surface as Ichthyostega staggered onto the shores and became unholy, as aeons of men staggered onto new shores and became unholy –I’ve been shimmering over each dark place like a film.

Admire me now, girl, as I flaunt my figure big and bright as an old theatre actress, enveloping you in my steamy glow like a clam shell until the sunrise pries me open with her rosy claws.

Falling asleep to Liszt’s Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, I was ecstatic, grateful to be alive. In the cantando melody I could almost hear the faint crackle of my soul – flaming, wavering, like an upswept cyclamen vowing to outstare winter. Behind the curtains, the fluttering chords ruffled a stretch of moon-blanched sea, and, returning stealthily, murmured by my ear to hold out hope.

***

‘Can you – can you pass me the sunglasses?’ Surprised by my own croak, I stumble over words.

I receive them with my left hand while keeping my eyes on the road. But she gave me the wrong pair: this pair is unpolarised. Well, so be it.

***

The long drive drained me – it was the glare and the heat, and the silence. Silence, that is, apart from the drone of wheels on the asphalt, and trucks trundling by, that still dimly throbbed in my temples. Though it was I who proposed the trip, whatever zest I had for the viatic had dissipated upon arrival. Like an oil stain, fatigue would blot out my mind, or rather bleach my thoughts until only one remained: to curl up under the sheets, my back to the balcony which, I would discover later, gave onto a magnificent stretch of elliptic shore.

No doubt it made her unhappy, and she had every right to be unhappy. Even I winced at the prospect of an afternoon in bed, listening only to the spectre of waves tearing at the land. But a wedge had been

slid between us. It began that night when I complained about her footfall being too loud on the stairs, and dithered before knocking on her door. That night, one might say, marked the Mid-Atlantic Ridge of our relationship, but had the fissures not formed long ago even before that?

Cut to black. I turned my head through a slight angle, grazing the pillow, but still could hardly see anything. I stared into the inky blackness until finally, with a faint shock, it dawned on me. That the night had really fallen, and she was not here beside me. I slid a hand over the pillow, perhaps to feel the absence, or search for a thread of hair to sweep. My limbs were suffused with lethargy. My fatigue returned. I stuck in my earphones and played some classical piano.

If only I could start again. The fact that she had left me in the dark seemed to clinch our conclusion. I repeated the phrase, if only, until it became quite empty and pathetic. The breeze that seeped through the window screens bore the antidote to summer, and I thought about what must have been out there in the night – the ridges of a moon-hazed cumulus, stars that never wink out, waves scrubbing the foreshore for another eternity. In that landscape I seemed to find solace, as the tender chords and singing bass rang in my ears, and then reverberated in my entrails. ***

Late afternoon, the moon hung pale in the air. She removed the key from the door and slid her hand into mine. With a furtive glance, I thought I had caught on her face the vestiges of a smile which made my heart throb. In the brisk air I saw seagulls, beating their wings to banish an ebbing tide, and soaring with such vigour, at the wild gale’s call, over the wispy sky that a few contrails had slashed. In the dulcet sunshine, everything seemed to assume a crystal clarity.

The path narrowed before us and I had to walk in front. A row of buildings on the left cut off the breeze, and painfully recalled the stale air that was in the car: too thin for a full breath, too thick for a word to cut in. I hastened past the buildings until the beach reappeared, and waited

for her before descending together a flight of stairs leading to the sands. We walked along the shore. The waves roared.

***

She’s seated on the balcony. ‘Come and look at the waves,’ she calls out, trying to conceal – unsuccessfully – her excitement.

‘I’m too tired,’ I reply, irritated by the pretence.

***

A wave rushed upon the sands, and, after some violent struggle, left on the beach a ball of seaweed that unfurled like butterfly wings. I drew nearer to the water, crossing the threshold marked by strips of seaweed, and, for a moment, there was nothing in my sight but the infinite ocean, over which a rose glow had begun to diffuse. I indulged in the scene for a brief instant, then jogged to catch up with her.

If only I could start again.

She was leading now; I followed, watching her sandals skim the sands. Beside the long stretch of beach, strips of grey rocks sprang up and formed a barrier against the waves. Jets of foamy water splashed over the rocks, filling the holey surface for an instant before draining away. We watched a few rounds in silence.

‘Isn’t it beautiful?’ I burst out.

She nodded. Her hair fluttered a little before settling down on her shoulders. ‘It’s beautiful,’ she said. It must have been the wind which made her voice so distant, a bare whisper. I was shivering now in the dusk; my fatigue returned and the sea had become deafening. I had covertly prayed that the shoreline would extend forever, but now I wavered.

***

Standing before the door.

Quite some time has passed since the last knock, but there is still no response. It’s not the right time to open the door. Perhaps it would startle her. But she knows, surely, that I’m still standing there – to apologise, I suppose.

Tired of thinking, I turn the handle.

The door is locked. ***

I stumbled on a cluster of seaweed and, thinking I was going to fall, called out her name. But she could not have heard it over the waves.

Regaining balance, I realised it was not seaweed that I had tripped over at all, but a half-interred seagull, with thick grey feathers that jutted out like grass. I stood there transfixed, hands on my knees and panting, as the dusk grew more opaque by the second.

At last I looked up and met her eyes. Dazzling eyes, like star-glints on that shore under a lethargic half-moon, as cold wind wrapped around my forehead and I saw, in the ocean’s vignetted frames, a seagull riding the waves alone.

If only I could start again.

‘There’s something I want to talk to you about,’ she said.

But that something I already knew. ***

Grazing the pillow, I turned my head through a slight angle. Abetted by a genial breeze that at that moment lifted the curtains, and by the thinnest shard of moonbeam, I made out her soft-limned features, her brows – lightly knitted in slumber, trembling a little with each breath. She must have come back from a walk. I held my breath, afraid to wake her, and couldn’t contain a tear.

the moment she steps out, she sees them. butterflies. sweetly wafting around the garden, metamorphosed, severed –

or; roughly, I pray.

severed she ran wings trembling furiously winds exposing supple skin the swift savagery of golden apollo stalking chaste flesh, giving chase to feet leaden with fear

ahead, a kaleidoscopic cluster of orbs flutters between evergreens in defiance of the hunters watching from the skies. glittering as the sun glances off bejewelled pinions their bodies moving as one wind moulding their flight in waves –

air washes over her, she concealed between maidenly branches of laurel wreaths wrap round her soft body thin bark pierces her breast, rhizome driving under virgin skin eternal

and hanging from a low-reaching branch are the knobs sheathing ripe golden pupae the aura of sublimity in nature’s rapturous ceremonies ecdysis

the shedding of skin –and yet always will he have slivers of her limbs snapped subdued crafted to his blonde crown, songs sung by lyres her beauty quivering easy broken is that laurel, the sacrificial –

I can’t shake the feeling she is afraid I can’t shake the sensation the appeal of a chrysalis where no one can reach I just can’t shake the prickle downy hair on my nape desire to escape –she did not want to burn with him. she will.

It was your idea to leave the gas cooktop on while tending to the unkempt weeds and occasional shrub in the backyard.

Afternoon dashes to the grocery store keys in hand, loose change in cargo pockets Returning with a coy smile and a small unnamed plant in the palm of your hand September kept them from fraying.

I couldn’t help it when the ten-minute version of her song played, where I had to dance in the kitchen in the refrigerator light Because she told us to.

She was well-meaning.

So maybe both of us had a part to play.

Once, when you’d driven to the hardware store to pick up a watering can, fresh timber and three different basecoats of white

You stopped on the way back to pick out flowers for your soon-to-be-ex-wife only to hit a pothole and call my line In a half-conscious haze where I proceeded to throw on a coat and a pair of navy suede shoes before calling a taxi to you

The gas had still been left on, Unchecked

September is dawning, peel off your tights, let me touch those pink legs that have not seen the light since you were the more tender age of eighteen, step out of your skirt and step into the steam.

I see the blue dots under your rind I see the red welts on your underwear line. Let me palliate skin that lies chalky dry Let me wet the cutis that covers your thighs.

The water does not ask or halt to overflow your body now: your shoulders wet, your matted hair and your back in droplets drowns. Through the fog, the mirror peeks at two legs spotted with strawberry seeds.

The hull coyly raised, from the place where you tweezed out your blue ghosts from the pink deep, Let me lick up your pair of strawberry legs Put me down onto my knees, let me beg.

I’ll feast upon your bare skin here: the warm, ripe flesh that’s tender sweet and softened in the soapy damp, the juices trickle down my cheeks. Your calves have the sickly sweet taste of the young, I cut your rubbery knees with my tongue.

Finds Ladybird lover on a balcony of a thirteen-storey apartment during a ‘meet the neighbours’ event, hosted by the landlord who goes by the name, Crash

Fifteen minutes of small talk and semi-pleasing icebreakers has the pair arriving at the conclusion that they should fuck

Buzzcut Killer wears his name like a badge, Runs his hands through his hair And unironically wears sunglasses while indoors, most times

Ladybird lover houses a notebook in her handbag, is never without a bookmark, a pencil and a trade secret of some kind She takes sunscreen with her whenever a day is forecast to be over 20 degrees and offers to leaflet for community centres on her off-days

Buzzcut Killer and Ladybird lover get drinks from the open bar and share canapes from the same entree plate

They eye the place for any other partners they could take for the evening, flip a coin to decide who gets to have who while the watercooler chats come to an end

tails wins out, yet they leave hands loosely clasped with the barest sincerity

There we were, swaying to the music again. His hand in a firm hold on mine; he was to lead. I yielded. It was always the rule, of course, there was no tolerance for a domineering woman. The order was that the man was in charge, and if the order was broken, then chaos would unleash, all society would disintegrate. He led me into a spin, my body pulled into an almost imperceptible whirl.

Impossible! I did not even comprehend that I moved, lest in such quick motion. I glanced at him with a wicked smile, which he returned amiably. Oh, what sweet ignorance! Despite everything, we were on utterly different planes. He decided that I was created for matrimony. I knew that I would retain my freedom. He was besotted by my shapely decolletage and ravishing charms, but did not care to look further into why I acted like this, or if it was a facade. He simply smiled and continued dancing.

I glimpsed the boutonniere tucked under his starched white collar: a sprig of blue forget-me-nots.

‘Just as delicate and beautiful as you are.’

A boutonniere – a sumptuous bouquet, carried down the aisle… I could rend those fragile flowers apart, tear apart the stem, and stamp the petals under my feet.

Yes, there he was. He spun me yet again, and I revelled in the motion. The hall was filled with such dancers, so engrossed in temporary joy, heels kicking and bodies swaying, ready to exert all their energy the next night to the next, year after year…

The thin crepe de chine of my carnation pink gown now stuck to my back with perspiration. I let my gaze fall onto the crowd of men against the wall. They noticed me, a hint of regret in their weary countenances. If only I could have approached them and asked for a

dance. I would have stamped out the fire in my suitor’s heart then and there. A softer end, a theatrical end. But I was not going to conform to mere convention. He insisted now, another up-tempo dance.

‘I feel so energetic,’ he beamed, ‘that I could go on dancing all night.’ I assented. We circled around the hall yet again and the band played on, unwavering in the swing melodies. But I was not finished yet. There was still midnight to see, then the early hours of daybreak – where the sky becomes an indeterminate grey – when we would wait for the hand of destiny.

The hall was now filled with guests all sitting down. They carried potent drinks in hand, languidly watching the quartet play and us dance. I was not finished yet; I had more. More, more, more, I promised him. He was delighted, grasping my waist tighter, pulling me closer. I would deliver the promise, yes I would. Then, in one devilish trick, he spun me whilst lifting me off the ground. The spectators gaped, gave a resounding applause at the stunt. When I touched the floor again, I breathed relief. He would not deceive me, I thought. I had to gain every advantage. Now the band turned to us – would we continue on? It was nearing midnight. He insisted that we should rest. But I resisted, saying I was nowhere near finished. We would dance until I had exhausted every nerve and muscle.

So we continued, never ceasing in our pace. I moved in perfect rhythm, landing each step without fail. His arm began to tremble. I held myself with the utmost grace, standing straight but not rigid. Finally, I was gaining my advantage. The band played a slow ballad – a Fats Waller love song. We moved in close, swinging side to side like a pendulum. I would not stop, would never let him stop. My motion was perpetual and relentless; if it ceased my essence would crumble into a void. He had the audacity to whisper into my ear a proposal – that afterwards we repose on the balcony. It was imperative that we were alone, he explained. I had already decided.

‘Yes, let’s rest on the balcony after.’

‘Splendid, my dear.’

My dear! Was I already ‘my dear’ to him, a man merely two steps removed from being a stranger? I saw it in his possessive gaze, a

gaze that had predetermined my fate. Already ‘my dear’. My – already his. But I was not going to yield to the fancies of a passing suitor. His words were gauze and I was the sharpened blade, ready to cut it apart.

The band struck the final chords. He swung me into a charming dip, his cheek so nearly tainting my skin. We held out our arms in triumph, and the crowd cheered. Yes, us, such formidable partners! Many of the spectators were now asleep on divans. Waiters collected empty glasses from the floor. He gestured to the drunken crowd; how stupid they were, polluting their robust minds with excessive drink. Women reclined with frizzled Marcel waves and gloveless wrists. The stench of cigar smoke lay heavy in the air. I followed in agreement. He took my hand – unlike me, who was so sensible, who knew how to conduct herself. He took the lead, bringing me into the open air of the balcony.

I was near finishing. I leaned on the balustrade, gazing out into the stygian view. A cascade of burning stars shimmered in the sky. I saw a cluster of diamonds shining upon a lady’s bare collarbone. The chilly air tempered my hot skin. He stood next to me, turned so that his vista was my wretched figure and inquired about my time at the dance. Did I enjoy it? Was the hostess adequate? Was the band competent?

‘Yes, yes,’ I said, to all of it. He placed his hands around my shoulders. I raised a piercing countenance to him. I saw it; his malleable features like uncooked dough, presently set in a yearning expression. His eyes betrayed a timely limelit glint. He took my hand and professed the same profession that men have uttered for millennia.

I did not, could not give an answer. The limelight in his eyes persisted still, hoping for the glamorous ending and curtain fall that it anticipated. His saccharine voice implored me to surrender. But I couldn’t. Surrender had left my blood long ago. He stood there, unaware that he was merely an actor, and I was the god who would dictate his ultimate fate. I knew it; it must be done now. A searing tension surged through my fingers. I must draw close and fulfil my righteous desire.

With blinding deftness, I hauled him by the legs and threw him

over the balustrade. He toppled over without even a gasp of agony. His body was like a stone tossed into a lake: a perfectly stoic and unmoving vessel dropped into irretrievable depths. And the weight dissipated.

When I next looked, his mangled body lay unmoving on the lawn. In the deep sable darkness I could not discern much, but I thought I beheld a stain creeping from his skull. Oh, but what a pleasant resting place, there on the soft green grass. He shall return to the soil. The icy night erased all traces of his body’s warmth on my skin. His body ignited a grotesque joy in me. Yes – I had triumphed through death. Now I had all life in my grasp. As I walked away, I felt a bump underneath the sole of my satin heels. I picked it up: a gold ring. I laughed, tossing it below to the grass. A trifle of men’s brittle affections.

The clock struck one-thirty. I descended the ornate staircase, visibly weary. Anguished shouts echoed from without. I had to hurry home, get sufficient rest. The house was deserted, not even a servant for assistance. I did not need anybody to escort me or bid goodbye. My time there had finished. I ignited the engine and drove off into the unbound distance, free to return to the comforts of home. Domestic bliss was awaiting me.

So I swung open the double doors to my parlour. Not a single guest, no suitor, no drunken crowd reclined on my sofa. Ah! Freedom, pure silence, no obligation to compromise. I peered through the velveteen curtain. The moon, a pearl suspended in the inky sky, beaming down on this mortal realm. The moon – always a benevolent woman, guardian over human vicissitudes. And I think that night she smiled upon me.

Detrimental lusting after forbidden people

I can tell you’d like me if I was a little evil. You decide to give me a lift home. Joy to cause the fall of man Thrust clawing hands in underpants.

Systematic poisoning of suburban people

You can only hate me for making you deceitful. The buckle on your belt is not my friend. Front-seat sex is hard enough without fighting with this kind of stuff.

Patriarchal fucking over not-so guiltless people

Feeling no remorse for my actions is too peaceful. Your hands cement their place around my neck.

If it’s just a cliché fuck it hardly rates as misconduct.

Hedonistic orgasming with drained and draining people. Is it love or cunning that makes me want this evil? Your wedding band is tight upon your finger. I am just an empty face but you love the way I taste.

Trumpets blare and a blue-tinted graphic overlay passes over shots of surfers out on the ocean. The camera pans across to the aggressively photogenic, gun-and-badge-wielding stars of CBS’s rebooted Hawaii Five-0, one of America’s many long-running buddy cop shows. It’s a funky, upbeat, almost fanfare-like track, using the same iconic instrumentation as the original 1968 production’s opening theme, despite initial attempts to modernise it (complete with clunky synth and grating guitar riffs) in early versions of the reboot. Based on the premise that the in-series Governor of Hawaii sanctions the set-up of a law enforcement task force with ‘full immunity and means’ in order to reduce high crime rates and terrorism, US Navy Lieutenant Commander Steve McGarrett partners with Honolulu Police Department Detective Danny Williams to solve crimes with a supporting team including Detective Chin Ho Kelly, Officer Kono Kalakaua.

You can almost predict exactly what happens next – it’s what happens with every formulaic police procedural: crime occurs, good and pretty cops attempt to solve the crime, an ‘unexpected’ plot twist occurs, the bad guy gets away, and then the good guys come in to save the day in the end in the form of some deus ex machina. Despite this predictability, Five-0 and scores of other serialised cop shows, from the dramatics of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation to the mostly light-hearted Brooklyn Nine-Nine, have enjoyed high ratings and viewership across the Western cultural sphere. In fact, the rebooted Hawaii Five-0 was popular enough to have a decade-long run from 2010, with off-network syndication rights now sold off, ensuring its continued broadcast internationally. I, myself, was susceptible to its dramedy-adjacent charm as a form of mindless after-dinner entertainment with my family when I was younger.

Five-0 ostensibly distinguishes itself from other US crime procedurals by virtue of its setting in an exoticised Hawai’i and boasting an ethnically diverse supporting cast. But that’s just a surface-level difference that does not exempt the show from the critical examination that other police-related media have received in the past few years. In a period of resistance to systemic violence and police brutality in the form of movements like #BlackLivesMatter, Five-0 is just one of many shows that portrays the US justice system in a morally-righteous light, dubbed as ‘copaganda’ – a portmanteau of ‘cop’ and ‘propaganda.’1

At its core, the show plays its part in reinforcing the same cultural hegemony as any other crime procedural. In this case, Gitlin’s theory of cultural hegemony (dominant ideology of the ruling class, à la Marxism) as being reinforced and reproduced in prime time television,2 can be used to break down how Hawaii Five-0 and other police procedurals reflect a culture of glorifying police brutality and systemic racial injustice. Gitlin outlines formal devices through which hegemony is reinforced and reproduced, including: form and format, genre, setting and character type, slant, and solution.

The form and format of serialised TV have contributed immeasurably to the dissemination of socially and culturally dominant, hegemonic ideas. In a world where streaming services are accessible from the comforts of our couches, ideologies bleed into our private lives and spaces without giving us room to unpack the content that is being paraded before our eyes. Glittering advertisements and blatant product placement in shows gets us ‘accustomed to thinking of ourselves and behaving as a market rather than a public, as consumers rather than citizens.’3 Five-0 is rife with gratuitous shots of the Chevy logo every time a character gets in or out of a vehicle. Before streaming services, television was routine - daytime soaps had their slots, and primetime had its after-dinner seat of honour.

1 Corbett 2020 2 Gitlin 1979

3 Gitlin 1979, 255

But this new age contributes to what essentially is a privatising environment of leisure that makes it harder to be critical of what is shown on TV. We are seeing and watching it all on our own screens ‘in the privacy of our living rooms,’4 on our laptops, computers, or even our mobile phones. There is no room for public discourse, unless you take that further step to online discussion – which not everyone has the time for, and not everyone will even consider an option. This is particularly true with genre shows, such as Five-0, that are predictable and procedural. They’re routine entertainment for most, and don’t often inspire the same critique a high art film or a limited dramatic series might.

The banality of these procedurals is almost insidious; in our quest to consume mindlessly, the ideology that is normalised by these shows remains too often unchecked. Police procedurals like Five-0 are allowed to continually take up airtime and enjoy cultural currency by virtue of their temporally digestible plots; we expect to see cases closed, happily ever after. But this predictable format reflects the idea of a benevolent police system. Dangerously, it turns this idea mundane.

Genre is how shows are framed according to existing TV markets – and cop dramedies now with their ‘good’ cop depictions play an important role in reinforcing the idea that the police system works and will address rising crime.5 This is contrary to what is becoming clearer to the public eye – that the system (both in the US and domestically here in Australia) is structured in a way that protects cops first, in cases of police brutality and systemic violence, particularly against Black and Indigenous people.

The entire premise of this show is based on the idea that the main characters belong to a special task force with no oversight and no restrictions; what normally counts as police brutality and abuse of authority is validated textually by the task force’s special status. In

4 Ibid 5 Gitlin 1979, 257

one episode, McGarrett breaks the arm of a drug trafficker to take his place undercover.6 In another, Williams assaults a man who abducted a young girl after they take him into custody – as his commanding officer, McGarrett asks for his gun and badge and walks away from the two of them, allowing Williams to continue beating the criminal.7 It is a habitual violence that is displayed in almost every episode, justified on screen by the evils committed by the antagonists.

But this routine is one that, for all that the average viewer may believe themselves to be able to separate fiction from reality, worms its way into our subconscious as something acceptable. On TV, cops bend rules and beat up criminals with no consequences, because they’re the good guys. In reality, the distinction is less clear. Who is to say that the one being beaten up has not been wrongfully accused? And what gives the police the right to be judge, jury, and executioner all at once? It has perhaps remained embedded too far into our cultural consciousness that ultimately, the cops are the good guys - copaganda shows like Five-0 only further this undeserved absolution.

Slant, in a police procedural, seems intertwined with genre conventions. As the name suggests, slant as a device is when a certain ideology is pushed within the content of television, ‘embedded in character’8 – not on specific topics, but in a more basic way, lest an obvious bias be registered by the audience. With many police and spy dramas of the 60s and 70s, the violent arming of terrorist or anarchist antagonists was accompanied by the cops being given the chance to ‘justify their heavy armament and crude machismo.’9 In the particular case of Hawaii Five-0, this violent arming of antagonists is seen throughout the show. On the flip side, the protagonist cops are armed to the teeth in retaliation, from semi-automatic rifles to full out military equipment where CIA or Navy involvement happens. This 6 Lenkov and Wheeler 2016

violent characterisation leads to the effect of ‘the delegitimation of the dangerous, the violent, the out of bounds.’10 Indeed, the excessive violence of the police is gradually delegitimised through this consistent slant in combination with the genre-typical framing of the police protagonists as well-intentioned bearers of justice. The violence is declawed , made to seem benign or at best benevolent. This then leads to the reinforcement of the idea that police should or are within their rights to exercise violent power against citizens.

But beyond genre conventions and slanting ideologies, the actual setting and characters of the show also reflect the dominant cultural norms, not the least being exoticising Hawai’i and Hawaiian culture. As Barthes does in his semiotic studies of myth, we look to obvious symbols.11 Gratuitous shots of palm trees, beach babes, and perpetually undone top buttons – these icons become signifiers to carry the idea of a laid-back, relaxed vacation destination. The cultural myth of Hawai’i as a tourist hotspot is resultantly perpetuated.

However, the past decade (and before that too) has seen as a result of too many tourists, the cost of living for locals skyrocket and displacement of Native Hawaiians continue.12 The depiction of Hawai’i from such a one-dimensional Western standpoint has meant a reinforcement that the land is in fact sovereign US soil – an issue that has been hotly contested since the US overthrew Queen Lili’uokolani in 1893 and annexed the Kingdom of Hawai’i in 1898.13 Showing these cops operating throughout Hawai’i is in and of itself an implicit admission that Native Hawaiian claims on land are considered illegitimate, which legitimises structurally the role of the US to govern morality in Hawai’i (very ‘White Man’s Burden’ of them). While the show makes plenty of reference to Hawaiian culture, and its history in select episodes, even the single episode that brings up the sovereignty movement Nation of

10 Ibid 11 Barthes and Lavers 1957 12 Maniece 2021 13 Mzezewa 2020

Hawai’i (who claimed a portion of land back in Waimānalo on O’ahu from the US government in 1989) employs them only as a narrative device and obstacle in the capture of a Native Hawaiian suspect.14

On and off screen solutions, all tied up in a bow.

Since cultural hegemony seeks to reproduce and reflect the status quo, the final device of solution identified by Gitlin is perhaps the most important one for the continual reinforcement of dominant cultural norms. As Gitlin claims, cultural hegemony ‘operates through the solutions proposed to difficult problems’.15 Solutions in television resolve problems at the end of the allocated time-slot, bringing everything back to how it was before – the bad guy defeated, arrested, and the good guys happy and vindicated. Indeed, the predictability of this sequence is what keeps us hooked to these shows - by the end, viewers have a happy ending and are not left with glaring questions that cannot be solved in another hour-long episode. Five-0 is a prime example of this – the protagonists are the main drivers of the solution that ‘leaves the rest of society untouched,’16 regardless of if the villain is a corrupt government official or a petty thief.

But what then happens when society changes? Well, hegemonic ideology changes with it.

We can see this example in the show’s casting changes; cast members Daniel Dae Kim (in the role of Chin Ho Kelly) and Grace Park (Kono Kalakaua), who are both of Korean descent, left the show after the seventh season, citing unfair discrepancies in pay compared to their white co-stars Alex O’Laughlin (Steve McGarrett) and Scott Caan (Danny Williams).17 While Kim and Park were both consistently posed together with O’Laughlin and Caan in promotional material that billed the four as a quartet, their pay certainly did not reflect this apparent

14

O’Reilly 2017 15 Gitlin 1979, 262 16 Ibid 17 Saraiya 2017

equality. Though O’Laughlin and Caan played the leading roles of buddy-cop duo, Kim and Park had just as much significant screen time - especially after Caan negotiated less appearances to accommodate for his other commitments.18 A loss for sure, for a show that had succeeded in reframing the original production in large part by casting Asian actors instead of the consistent yellowface that the 1968 version engaged in. Prompted by emerging discussions around racial inequality in the entertainment industry, the departure of the main representation of Asian Americans in the show drew media buzz. However, there was a marked increase in screen time for other POC actors after their departure, with many of the supporting cast being promoted to series regulars. Clearly, the network paid attention to the cultural changes and increased importance placed on racial equality by the society around them. As Gitlin puts it: ‘The hegemonic ideology changes in order to remain hegemonic; that is the peculiar nature of the dominant ideology of liberal capitalism.’19

In the end though, representation of minorities on screen doesn’t make up for painting a picture of violent cops with what amounts to free reign with their treatment of suspects as ‘the good guys,’ especially when characters are clearly aware of the implication of the power dynamic they hold as law enforcement.

The show’s ending in early 2020 couldn’t have come at a better time – there’s now one less copaganda show being made. The remaining crime procedurals should be viewed with the same critical eye; complacency only serves to further the frightening normalisation of systemic inequality and police violence.

18 Ibid 19 Gitlin 1979, 262

Barthes, Roland, (1957). Mythologies / the complete edition, in a new translation. New York: Hill and Wang.

Corbett, Erin (2020). Copaganda: A look into the subversive ways police ask for sympathy. Why Copaganda Is A Dangerous Police Sympathy Tactic, Refinery 29, 2 July. https://www.refinery29.com/enus/2020/07/9887229/copaganda-police-propaganda-protests-meaning.

Gitlin, Todd (1979). Prime time ideology: The hegemonic process in television entertainment. Social Problems 26(3): 251–266.

Lenkov, Peter M (2013). Ho’opio. Hawaii Five-0 , episode, CBS.

Lenkov, Peter M and Wheeler, Matt (2016). O Ke Ali’i Wale No Ka’u Makemake. Hawaii 5-0, episode, CBS.

Maniece, Mykenna (2021). Native Hawaiians are asking for a reduction in tourism, and we should listen. POPSUGAR Smart Living, POPSUGAR, 3 September. https://www.popsugar.com.au/smart-living/how-tourism-is-negativelyimpacting-native-hawaiians-48465388 (accessed 26 April 2022).

Mzezewa, Tariro (2020). Hawaii is a paradise, but whose? The New York Times, 4 February. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/04/travel/ hawaii-tourism-protests.html.

O’Reilly, Sean (2017). Ka Laina Ma Ke One. Hawaii 5-0, episode, CBS.

Saraiya, Sonia (2017) CBS made wrong call on Daniel Dae Kim, Grace Park ‘Hawaii five-0’ deals (column). Variety, 6 July. https://variety. com/2017/tv/columns/hawaii-five-0-daniel-dae-kim-grace-park-cbsparity-1202488093/.

Slaughterhouse Five (1969) is a satirical, science fiction war novel written by Kurt Vonnegut, mostly centred around the fire-bombing of Dresden in 1945. Though the novel is semiautobiographical, based on Vonnegut’s experience as an American POW who survived the bombing, Slaughterhouse Five follows a soldier named Billy Pilgrim via an omniscient narrator. Despite all the jumbled generic tendencies lurking within the novel, it seems that the author’s main concern is to produce a work of historical fiction. He aims to preserve the memory and impact of Dresden in literature. Though the bombing has aroused controversy and debate, it is largely overlooked – this attack on Germany by American and British forces during World War Two (WWII) often seems needless to justify.

As someone who experienced the bombing, however, Vonnegut is far more ambivalent about the supposed necessity of this offense. Slaughterhouse Five delves into this event to illustrate the complexity of war, even in cases of unquestionably necessary conflict. In the first chapter, the narrator laments the difficulty of writing about the subject, a project he has had on his mind ever since he got home after the war. What is interesting is that the actual bombing is so scarcely detailed. What we get, instead, are the goofy misadventures of Pilgrim, a timejumping WWII veteran who doesn’t take death or war very seriously because some aliens told him it was all meaningless. This doesn’t seem to be very generically conventional.

Is this an appropriate treatment for such a controversial subject? Yes, and here’s why: the value of historical fiction is not in how accurately it represents the past. Rather, it is valued for its role in denaturalising

The War Parts, Anyway, Are Pretty Much

True: Science Fiction as Historical Fiction in ‘Slaughterhouse Five’

the present – showing that our reality today is not arbitrary, it was not inevitable, but the result of conjunctural, knowable material processes.1 In this regard, the science fiction elements not only make the novel’s historical treatment possible, they make it better and enliven it. Scientific accuracy and picture-perfect predictions of the future are not the central goal of the genre. Sci-fi similarly serves to denaturalise the present, and has much more in common with historical fiction than may immediately be apparent.

But is Slaughterhouse Five really science fiction? What’s the point of the Tralfamadorians if they can so easily be argued away as imaginary? I argue that the Tralfamadorians’ presence – whether in Billy’s head or Billy’s real life – introduces the aesthetic properties of science fiction into Slaughterhouse Five, which is what animates Vonnegut’s anti-war sentiments.

Today, the use of sci-fi tropes and techniques is extremely prevalent even in literature considered to be ‘outside the genre’, reflecting what scholar Sherryl Vint calls ‘the centrality of science and technology in daily life and the absurdities of living in a media saturated environment.’2 Vonnegut himself seems to have felt this way even in the ‘60s: recalling his trip to the New York World’s Fair, he says ‘we saw what the past had been like, according to the Ford Motor Car Company and Walt Disney, [and] saw what the future would be like, according to General Motors.’3 Vonnegut understands, and demonstrates here, the influence of the industrial titans of his time over the cultural hegemony of America, reshaping a past he actually experienced. Not only are our historical narratives shaped by these forces more than we’d like to think, they also influence the reality of the present and the direction of our future. As such, it makes more than enough sense to employ the imaginative possibilities of science fiction to make sense of such absurd, lived experience.

Many aesthetic elements of science fiction are utilised in the novel, but in subversive and sneaky ways bubbling just below

1 Freedman 2000, 56

2 Vint 2014, 121

3 Vonnegut 2005, 23

the surface. A common feature of science fiction is its use of critical, dialectical language. In realist fiction, Carl Freedman notes, the most familiar emotions – love, affection, hatred, anger – are rendered as static, universal experiences.4 Science fiction, however, provides us with cognitively plausible yet different worlds to test this against. Something that often helps to establish this dialectic is what science fiction critic Darko Suvin calls a novum, borrowing the term from Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch.5 Standard generic examples include time machines, spaceships, and hyperintelligent AI. The novum is, essentially, a device that is cognitively plausible, but which estranges this sciencefictional world from our world, acting as a catalyst for change, which is felt throughout the whole narrative.

We can see these narrative mechanisms in Vonnegut’s work. This is most obviously demonstrated in the near-future society of his debut novel, Player Piano (1952), wherein the workforce has been totally mechanised. The overarching conflict of the novel is between the lower class, whose labour and purpose are replaced entirely by machines, and the upper class – engineers and corporate managers – who service and profit handsomely from the machines. The automation of industry is the novum of this story, and it not only informs the conflict, but also the narrative voice. By prioritising the efficiency of machines over humanity, the worldview of the engineers has become distorted and callous. We see this in Dr. Paul Proteus, manager of the industrial plant Illium Works, and his disdain for his own wife:

‘[Anita] was hale, enthusiastic about Finnerty’s coming. It annoyed Paul, because he knew very well that she didn’t care for Finnerty… [he] had become a man of consequence, a member of the National Industrial Planning Board; and this fact no doubt dulled her recollections of contretemps with Finnerty in the past.’6

‘Anita had the mechanics of marriage down pat, even to the subtlest conventions. If her approach was disturbingly rational, systematic, she

4 Freedman 2000, 32

5 Suvin 1979, 16-19

6 Vonnegut 1952, 28

was thorough enough to turn out a creditable counterfeit of warmth.’7

The faith that Paul puts into this industrial way of life has made him inhuman. Paul is cold, unfeeling and distrustful of Anita, believing her to think and feel just as mechanically as the machines he looks after. There must be some sort of selfish, economic motive to her behaviour; the warmth she offers must be performative. Giving us insight into a bourgeois character in a cognitively plausible, dystopian future, Vonnegut illustrates how capitalism produces greed and indifference in people who may think they are on the side of ‘progress’.

Player Piano is uncomfortably dissonant to the Cold War context it was released in. A large part of what makes the wholesale automation of industry such an unquestioned good in Player Piano is its connection to America’s success in World War Three, an event that has already occurred by the start of the novel. This forms a direct parallel to Vonnegut’s own world, wherein the events of WWII justified America’s place as the ‘leaders’ of the ‘free world.’ America’s conduct during the Cold War relied on unchallenged trust in the American way of life –capitalism, the traditional nuclear family – and the ways in which they could help to spread this way of life – advancements in military science. Here, however, Vonnegut illustrates that these forces are not naturally compatible with the needs and wants of humans, and that scientific ‘progress’ may, in fact, be indifferent to what is good for us. This dialectic between our world and a science-fictive world is effective because it points out the historicity of things that we take to be universal, unchanging, natural.

Further more, this is a technological innovation that Vonnegut did not predict so much as observe. From his time at General Electric, Vonnegut took notice of the computer-operated milling machines that had replaced skilled machinists. When asked whether science fiction was the best vehicle for this kind of social commentary, Vonnegut responded, ‘there was no avoiding it, the General Electric Company was science fiction.’8 Additionally, the full scale automation of Player Piano has since been seen in countless industries, exemplifying a literary novum that

7 Vonnegut 1952, 29

8 Vonnegut as cited in Freese 2002, 125

has become a reality. To put it another way, science fiction is effective not only for its fanciful predictions of a far-off future, but what it tells us about the present in a way that realist fiction cannot.

With this in mind, we begin to see a subtle, yet remarkable subversion of sci-fi conventions in Slaughterhouse Five. Billy and the omniscient narrator are so completely immersed in Tralfamadorian philosophy that it colours the entire perspective of the novel – our world is rendered back to us in completely alien terms. One scene describes Billy, during a bout of sickness, soiling himself while he coughs his guts out. The narrator follows this unpleasant description by stating, very matter-of-factly:

‘This was in accordance with the Third Law of Motion according to Sir Isaac Newton… this law tells us that for every action there is a reaction which is equal and opposite in direction.’9

Not only does the narrative structure resemble what Tralfamadorian literature is described to be like, the novel itself also reads like an alien’s take on humanity. Euphemisms and obscenities are always taken by Billy, and the narrator, extremely literally, creating an alien detachment from reality that flattens everything – including figurative language. When Roland Weary calls Billy a ‘dumb motherfucker,’ it’s treated like a genuine accusation. Billy is shocked, and the narrator assures us that ‘Billy had never fucked anybody before.’10 This not only provides humour, but it also enters the reader into a dialectic with our empirical reality from a completely new angle, producing the cognitive estrangement that we usually get from science fiction.

This defamiliarisation extends to the war at large, blending science fiction and historical fiction across genres. The narrator is absolutely indifferent to national and ideological ties. So, unlike most war novels written by veterans, Slaughterhouse Five makes the whole affair look completely unglamorous. Rather than being a masculine, character-building experience for Billy, serving as a soldier in WWII has left him an infantilised shell of a human. Justified as it is to fight against

9 Vonnegut 2005, 101 10 Vonnegut 2005, 42

fascism, joining the war effort means sacrificing one’s individuality and becoming, to quote the narrator, ‘a listless plaything of enormous forces.’11 One character makes a notable exception - Edgar Derby, the heroic schoolteacher who stands up to a Nazi for liberty, individualism, and equality. But this affords him neither safety nor a dignified legacy, for he is rewarded with the most humorously pitiful death in the novel.12 Here, the idea that Derby’s individual sacrifice contributes to freedom, or any other ‘inalienable’, patriotic virtues, is downright laughable – a rare sight in an American war novel.

Vonnegut even dares to complicate our view of the Nazis. Not once, in this novel about an American POW in WWII, is the word ‘Nazi’ or even ‘fascist’ invoked to refer to the German soldiers. This may initially seem like a sign that Vonnegut is a political quietist, but it is

11

Vonnegut 2005, 208 12

Vonnegut 2005, 1

arguable that there’s purpose and nuance to this choice. The only person in the book who is referred to as a Nazi is the man who Edgar Derby stands up to – Howard W. Campbell, who was, to quote the narrator, ‘an American who had become a Nazi.’13 This says something far more compelling than a tale of the Heroic Allies versus Evil Nazis. It says something about choice. Vonnegut destabilises the notion of Nazism as a monolithic or incomprehensible evil, a sort of plague which inexplicably swept through Germany and simply ‘happened’ to the moral actors responsible for the Holocaust. Here, we find a sobering reminder that being a Nazi is a political position, a conscious decision to give up one’s humanity. Edgar Derby states this plainly – he calls Howard a snake, but corrects himself, saying that snakes can’t help but be snakes, whereas he could help being what he was.14 Contrary to popular understandings of America’s place in WWII, Vonnegut highlights here that ideology transcends borders and that the Americans were not so immune to fascism as we would like to think.

So, what does this have to do with science fiction? Well, it is intrinsically linked to the use and abuse of science, as embodied by the bombing of Dresden. Because of the book’s non-linear jumps through time, we’re aware of the bombing and its consequences all throughout the novel, even when we’re in the middle of the war with Billy. In vaguely illustrating the bombing as a looming threat of annihilation, an inevitable and traumatic experience that will just come to Billy whether he’s ready or not, Dresden represents the newfound, apocalyptic power of modern warfare. Judged by the usual, simplified justifications given for the war, this capacity for destruction seems necessary. Vonnegut denaturalises the situation and makes us think harder about the ethical foundations of military science. Today, the actions of the allied powers, no matter how atrocious, have been comfortably assimilated into our collective historical consciousness. This defensive attitude is seen in Bertrand Rumfood, the conservative history professor who coldly responds to Billy’s war stories that the bombing of Dresden ‘had to be done.’15 Vonnegut doesn’t allow us to think of the bombing as such an unproblematic solution, as a necessary evil against more evil. We’re challenged to reckon with the

13

Vonnegut 2005, 206

14

Vonnegut 2005, 253

Vonnegut 2005, 209 15

ethical implications of the enormously destructive power wielded by the West.

Vonnegut’s conflation of science with destructive warfare echoes most resoundingly in the last chapter of Slaughterhouse Five, this time regarding what was happening at the time of publication: ‘every day,’ he says, ‘my Government gives me a count of corpses created by military science in Vietnam.’16 By looking at our empirical reality the way we would look at a sci-fi dystopia, the military technology wielded by world superpowers since WWII becomes the novum of our world. In doing this, Vonnegut enlivens the historical experience of the bombing of Dresden, a forgotten moment of modern warfare, in a conflict that effectively gave America its licence to police global affairs. In this way, science fiction connects this overlooked historical event to the violence of American interventionism which continues today. This is what elevates Slaughterhouse Five from a 53-year-old novel about WWII to a prescient statement about war that is more relevant than ever.

The value of this historical treatment lies not in its delicacy or comprehensive detail, of which it has almost none. One reason it remains so compelling and timeless, however, is its engagement with science fiction. The interrogation of unbridled scientific ‘progress,’ its dubious motivations, and its potentially devastating consequences – all core tenets of the genre, all key takeaways from Vonnegut’s masterpiece. Science fiction not only allows us to confront the ugly logical conclusions of our current reality in some far-off, hypothetical future. Rather, it provides us a language to decipher our current reality, and the unfortunate steps that we took to get here. In this incredibly boring, tech-driven dystopia we live in today, science fiction is key to any decent literary treatment of the present, and even, sometimes, our past.

16 Vonnegut 2005, 268

Darko, Suvin (1979). Metamorphoses of Science Fiction: On the Poetics and History of a Literary Genre. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Freedman, Carl H (2000). Critical Theory and Science Fiction. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Freese, Peter (2002). ‘Kurt Vonnegut’s ‘Player Piano’; or, ‘Would You Ask EPICAC What People Are For?’’. AAA: Arbeiten Aus Anglistik Und Amerikanistik 27(2): 123-59.

Vint, Sherryl (2014). Science Fiction. A Guide for the Perplexed. London: Continuum Publishing Co.

Vonnegut, Kurt (2005 [1969]). Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Random House.

Vonnegut, Kurt (1952). Player Piano. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Lieutenant Kaid slowly emerges from beneath the shrubs.

Forty soldiers watch.

Hidden behind spiky bushes surrounding the village, our knees ache from crouching too long.

We listen as rainbow birds chirp. The ensemble accompanies a woman as she draws water from the compound’s well.

Forty soilders watch. She steadily pours the fluid into an orange container and absently whistles the anthem of the Elaine Liberation Army .

She is oblivious. To the left, an elder peels two oranges. Beneath a pine tree, she sits peacefully. Her fingernails dig too deep, and the juices drip at her feet. She sucks her fingers, and the ants come to feast. Frustrated, she throws the orange peels at nearby chickens.

We watch. The pine tree protects her. From the afternoon sun. But little else. To the right, there are six mudbrick houses. Murmurs and laughter drift from the largest one at the centre. Moments later there is an eruption of cheers and about 25 residents emerge from the house. We tense, holding our breath. Lieutenant crouches down again. ‘Why can’t we just join them? I’m scared, Luro.’

Sen is rambling again and shivers between my legs. We’re huddled behind a sweet smelling shrub and breathe in unison as we try to remain silent. Six months ago, I found him crouching beside the Kaii river using his hands to drink from the murky water. From a distance, his tiny frame and dirt-stained clothes made him invisible as he crouched. When he heard me approaching, he became startled and screamed, exposing two broken front teeth and frightening the meadow birds. He tried fighting me and I almost laughed at his pathetic attempts to kick my ankles and nuts, but Sen was so serious. He was so frightened and angry that I let him punch me in the cheek. Once he had calmed down, knowing that I wouldn’t hurt him, he told me his story. Sen was an orphan, mourning his fathers murder and the disapparence of his sisters. He was between six and seven years of age and for four months, cried himself to sleep every night.

‘Luro please can we go back!’

Eli flashes him a look and immediately he hushes.

I whisper in his ear. ‘I’ll be with you all night, just stay close ok?’

He hesitantly nods; his curly hair brushing my chest.

When the Laine Salvation Force defeated the ELA, we knew that our sacrifices were a blessing for the people of Elaine. Their freedom from oppression had finally come. I rejoice with them, I really do. On our knees, between shrubs, we wait to take over this village and celebrate our victory. Our camp was too small so we needed a bigger space for our victory party. Lieutenant had passed by this place when he journeyed three days on foot to find our campground four kilometres east. This here, is a beautiful village, surrounded by palms, secluded and peaceful. We surround the compound crouching among the trees bearing six barrels of alcohol, two large battery speakers and pockets full of marijuana. Lieutenant has the pleasure of bearing ecstasy and ames tablets. Tonight, soldiers will drown themselves in golden booze and rainbow tablets.