AVENUE

The Journal of the University of Sydney Arts Students Society

First published 2023 by The University of Sydney

Funded by the University of Sydney Union and the University of Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

© Individual Contributors 2023

Foreword © Amy Tan and Melody Wong

Afterword © Teresa Ho and Sandra Kallarakkal

Graphic design © Amy Tan

Layout © Amy Tan and Melody Wong

© The University of Sydney 2023

Images and some short quotations have been used in this book. Every efort has been made to identify and attribute credit appropriately. The editors thank contributors for permission to reproduce their work.

ISSN: 2653-696X

AVENUE: The Journal of the University of Sydney Arts Students Society

Except as permitted under the Act, no part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or communicated in any form or by any means without prior written permission. All requests for reproduction or communication should be made to Sydney University Press at the address below.

Fisher Library F03

University of Sydney

NSW 2006 Australia

Email: sup.info@sydney.edu.au

Web: sydney.edu.au/sup

Cover Design by Yasodara

This edition of AVENUE was edited, compiled, and published on the occupied lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. We acknowledge that sovereignty was never ceded, and that the occupation is violent and ongoing. We give our deep respect and solidarity to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

This land always was, and always will be, Aboriginal land.

To the experience that made us who we are today.

Editors-in-Chief

Amy Tan

Melody Wong

General Editors

Sandra Kallarakkal

Teresa Ho

Creative Director

Yasodara

Lead Editors

Faye Tang (Non-fction)

Natalie Rathswohl (Poetry)

Nicole Zhang (Prose)

Editors

Aidan Elwig Pollock

Angela Xu

Anna Trahair

Danny Yazdani

Jem Rice

Jun Kwoun

Maja Vasic

Nicholas Osiowy

Sonal Kamble

Zara Hussain

Zeina Khochaiche

Amy Tan and Melody Wong

Angela Tran

Malavika Vijayakrishnan

Katt Johns

Teresa Ho

Ellie McLean-Robertson

Melody Wong

Natalie Susak

E.Pike

Amy Tan

Melody Wong

Amy Tan

Gracie Mitchell

Nafeesa

Zara

Her speed of

Playground Diaries

Life in the Doldrums

LOOK Percy and the Six

Playlists of your life: What are we to media giants?

The Tin Sheds - An Incomplete History

How Ramadan Rumbles: the top food items during the holy month

The chimes at midnight get louder with each passing hour

My father’s Friday nights routinely involve more alcohol and camarderie than my own birds of a feather

Grief Casserole

to you, again

The ghost of Narcissus

Chameleon Ipseity: An investigation into contemporary university identity

Teresa

October

On

Afterword

About the Editors

About the Contributors

Words from the President

Words from creative director

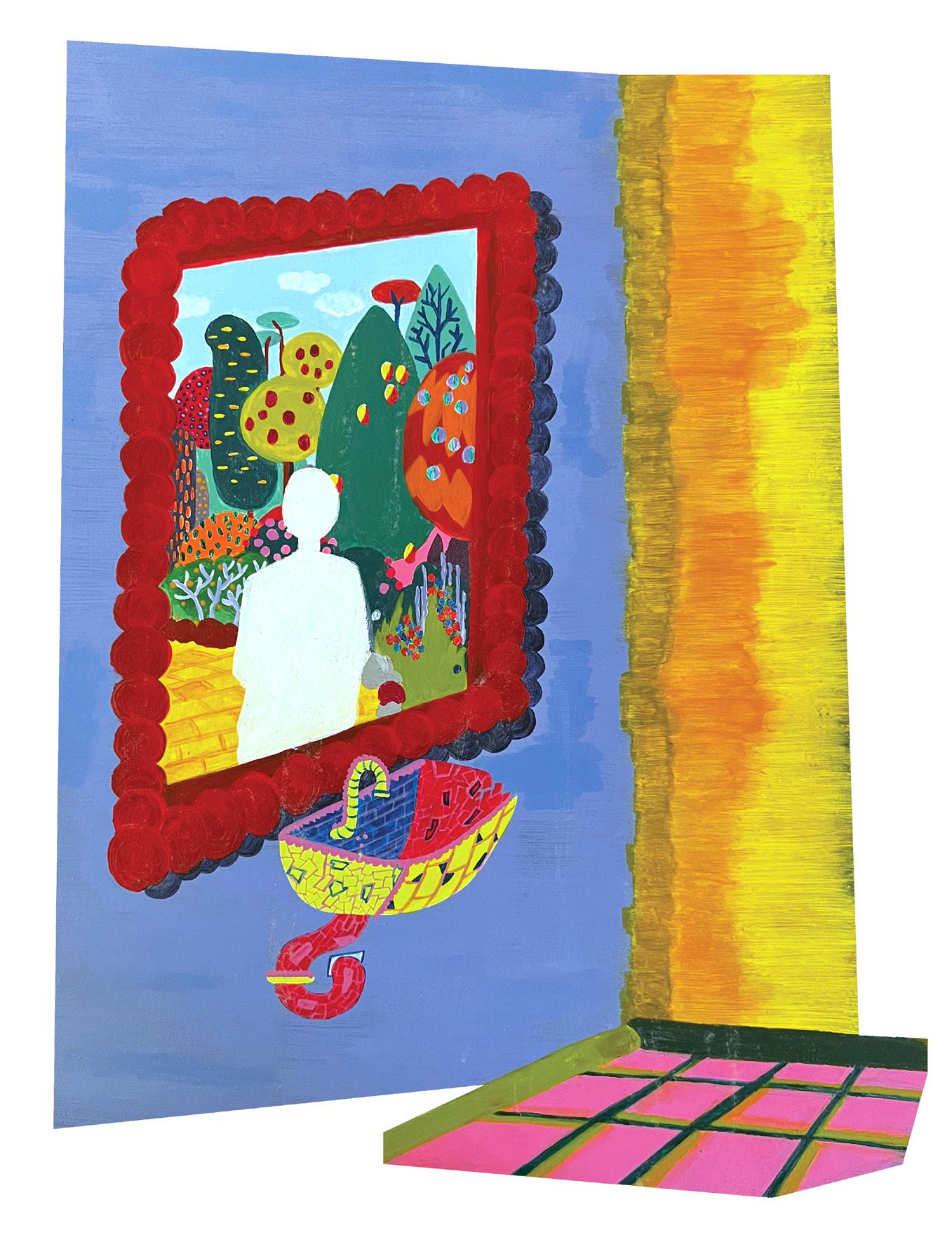

When we began envisioning AVENUE 2023, we knew we wanted it to embody a fresh sense of identity and theme. Refection came naturally as we looked back at what our past experiences have been like and thought about some overarching themes of the journal.

The idea of refection challenges us to reminisce and be introspective in our approach to the past, present and future. It could be seeing yourselves in a mirror, or tracing the steps of things that you have done. No matter what forms it takes, the process of refectiont helps us learn more about ourselves and the world around us - it is a product of curiosity, questioning and possibly a lot of inner monologues.

Refection is something that we believe we and the world need a bit more of.

The contributors of AVENUE 2023 traversed many paths of refection, whether it was the childhood nostalgia for making minced garlic, the feeting memories of playground adventures or navigating the complicated sense of losing a loved one. This collection is a testament to the beauty, triumphs and loss of being human, one which asks us to embrace our perfect imperfections.

Before we leave you to go on this journey of refection with us, we’d like to thank everyone who has helped bring to this journal to life. To our contributors, we know the act of refection can often be challenging. It highlights the warmest and most complicated memories in us. We thank you for sharing them with us and putting your trust in our team.

To our editors, thank you for your enthusiasm, insights, and most importantly, patience. It has truly been a delight to work with this team, and this could not have happened without you.

To our General Editors, Sandra and Teresa, and our Creative Director, Yasodara, massive thank-yous for the insane amount of time all of you have put into this journal. The tireless support you guys have given, especially during a few of the most hectic weeks this semester, has been crucial to the success of this journal.

And fnally, to our dearest readers, thank you for joining us on this journey and hearing what we have to refect on. We hope AVENUE 2023 flls and reignites your curiosity about the world.

With love, Amy and Melody

my mother’s hand squashes bulbs of garlic on the fat side of the knife –the juices o o z e out

like tears / when i think about her for too long to think that my mother’s mother and her mother’s mother squashed garlic with the same fat side of the knife –in a tiny kitchen and even tinier kitchens in a dimmed corner of Ho Chi Minh City as she watched eagerly, hoping one day to pass this onto me

i’m alone in the kitchen in Carlton watching the garlic o o z e underneath the knife, wondering to myself –if this is what i’m taught, why couldn’t they teach me to survive the harshest of conditions?

being frst generation here, losing what is there, feeling like i will always be torn between two places, a nomad of both cultures, never knowing if i am enough or who i am / what i am

i am a vessel of new knowledge made to teach them to survive here in this place disguised as home. i reminisce of a place not known to me as the garlic juices coat my fngers, a reminder of the language of love exists here, that i can speak i want to tell her i love her, con yêu mẹ

but the words get stuck like a conversation in my throat here in the process of mincing garlic

On the outdoor glass table bought years ago for the express purpose of gracious entertaining Five Budweisers –four in their cardboard cells and one free, warm and half-full Accompanied, of course, by limes –two of them, shockingly green, brought by the same friend who leaves bumpy, terrier-sized zucchinis that look and taste, according to my mother, like “monster-pumpkins” sitting on our kitchen counter after nights like these (more tax than gift, we joke) But with no knife in sight. All that has been cut Is a deck of cards –Bicycle brand; the sleek Copag box never makes an appearance unless he’s stayed sober (enough) Twin stacks, squared and forgotten.

Saturday’s afternoon languid, wavy with heat, Is nothing like his Friday night And even less like my own –calendar-checking, list-crossing, preparing and preparing and preparing.

My father’s Friday nights routinely involve more alcohol and camaraderie than my own

By Katt Johns

By Katt Johns

Clarissa had a theory … to explain the feeling they had of dissatisfaction; not knowing people; not being known. … It was unsatisfactory, they agreed, how little one knew people. But she said, sitting on the bus going up Shaftesbury Avenue, she felt herself everywhere; not “here, here, here”; and she tapped the back of the seat; but everywhere. She waved her hand, going up Shaftesbury Avenue… she believed (for all her scepticism), that since our apparitions, the part of us which appears, are so momentary compared with the other, the unseen part of us, which spreads wide, the unseen might survive, be recovered somehow attached to this person or that, or even haunting certain places after death . . . perhaps - perhaps.

from Mrs Dalloway (1925) by Virginia Woolf, p. 167

I am like a child in a funhouse, mesmerised by my refection refracted across glossy suburbia. On my way to my local library, I catch a vision of myself superimposed onto the lonely interior of a store that once sold replicas of Chinese antiques. I catch my own watchful eye thrown across a passing bus or car window. I search for myself, distorted, in mirrors that the rain occasionally provides when it pools in the gutters. Like a cat lazily chasing its tail, I try to capture my side profle, perhaps relieved that I cannot see my poorer angles. I want to convince myself that this exercise whilst fuelled by an indulgence of the self is not fuelled by narcissism, at least not the same vanity or obsession with physical appearance the condition’s namesake possessed. Instead, I want to believe that this chase after my refections is a reminder that I leave marks on the spaces I inhabit. Amidst everchanging suburbia – the crush of rolling trafc, blank pavement, sleek surfaces – I want to leave traces of myself. Spectral ones will sufce. There exists a desire to haunt places in the same way that same Clarissa Dalloway haunts Shaftesbury Avenue. Such that, if someone was to peruse the local library, graze their hand along the warm rubber as they descend the escalators at the nearby shopping complex or perhaps cast a glance into the now-abandoned faux antique store, they might catch my faint apparition and notice how suburbia hallucinates.

But how do you haunt a place that revolts against your memory? The park which I used to climb over, small poltergeist I was, has been demolished, leaving behind a pit of mulch. The park functions as a dog park now. The dental clinic that I visited as a child has been replaced by a Woolworths; my sister and I treated the clinic like a library, borrowing children’s books from the collection in the waiting room. Woolworths Hurstville East (‘East’ used to diferentiate it from ‘Woolworths Hurstville’ located a brisk 600m away) boasts a 4.1 star review. The shelves are always tidy and full. Its ‘new’ style is appealing. The reviews note that Woolworths East is quiet and empty but suggest that that is a positive quality. As you walk around Woolworths Hurstville East note the shiny refrigerator doors, slightly frosted from the condensation. Note your refection, pale against the blissful and multicoloured boxes of ice blocks and bags of frozen peas.

‘All around, the tinted glass facades of the buildings are like faces: frosted surfaces. It is as though there were no one inside the buildings, as if there were no one behind the faces. And there really is no one’.1 This is Baudrillard’s ‘ideal city’. Hurstville is no city. It’s located 16km from the Sydney CBD. There are over 31,000 residents – a sizeable number yet nothing to boast of. And yet, I occasionally see the ideal city encroaching upon suburbia. One Hurstville Plaza is a 14-storey commercial ofce building. It describes itself as a ‘living working’ environment. It appears so beautiful, yet so empty, in contrast to the patch of grass just outside the train station where parents queue to pick up their children from tutoring, where pigeons gather to peck at the chips which high school students have recklessly spilled, where members of the Falun Gong peacefully protest in the morning, where a toddler runs – small poltergeist – across the rainbow hopscotch. Staring up at the stillness of One Hurstville Plaza, I fnd it difcult to detect the shadows of the past and I cannot help but feel a little unmoored. I was struck by this pang of anxiety and fear when I realised that I had forgotten what the streets looked like before One Hurstville Plaza had been constructed. So taken was I by the static freshness of One Hurstville Plaza that I could not remember the streets of my childhood. I had to look up old photos of Forest Road to remember what used to exist in the space One Hurstville Plaza (note the blue-tinted windows) now occupies. There used to be an old arcade, a short strip of dimly lit stores. A

Facebook post written in March 2019 by the account ‘I grew up in Mortdale 2223’ describes how Jolley’s Arcade, opened in 1930, was created after Bert Jolley decided to excavate the land under his highly successful department store to develop his business. My mother used to occasion the forist at the arcade’s entrance. I see myself amidst the crowds walking as I walk past One Hurstville Plaza and hope to restore the faces to the ideal city.

In order to awaken the ghosts in this cold ‘ideal city’, perhaps it is necessary to recede into our country’s deep history in the hope that it might yield some hauntings. The late historian Minoru Hokari discussed the ways in which the Gurindji people actively practise history; rather than searching for history in the archives, the Gurindji people touch and feel history in the land around them.2 They remember where colonisers shot their predecessors when they drive past the hill where violence was enacted.3 The Gurindji people are acutely aware of the way in which memory inscribes itself onto place and the necessity of engaging with a place to access history.4 History is necessarily situated and our experience of it should be as well. Yet Hokari’s observations inevitably poses the question of whether non-Indigenous Australians can detect the ghosts that remind us of Australia’s true and deeper histories. Can my apparitions – the products of a second-generation immigrant – inscribe themselves upon Bidjigal land, a land that was never ceded? Or are my apparitions a testament to my complicity in the violent dispossession of the Bidjigal people? Perhaps Shaftesbury Avenue was Clarissa Dalloway’s for the haunting, but can Bidjigal land be home to my ghosts?

Bidjigal land used to swarm with mangrove trees. During the 1960s, the dense shrubbery was used as a meeting spot for illicit sex and viewed as a place where ‘bad things’ happened to young women.5 The ghosts of promiscuous youths are hazy. The ghosts of the Bidjigal people’s ancestors are obscured from sight even more. Few mangroves remain for the ghosts to cling upon to the haunting. Or perhaps, I simply cannot decipher what it is the mangroves communicate. And perhaps our inability to decipher the histories embedded

2 Hokari 2011, 92.

3 Ibid, 92.

4 Ibid, 112.

5 Goodall 2022, 34.

in the spaces around us perhaps means that we are truly haunted (for this should be a source of discomfort) by the futures that we failed to produce. Without recognising the benevolent ghosts of the past, the dream of a truly postcolonial society, the real ideal city, remains the phantom.

I imagine suburbia as a palimpsest made of ectoplasm, where the ghosts of my childhood are made more impalpable by gentrifcation and where those very same hauntings, the ones that seemed so benign to begin with, spread cancerous over our deeper histories. A few years ago, after reading a book on feng shui that we had discovered tucked into the back of the bookcase, my sister and I jokingly told my mother that we should remove the wall-length mirror that covered the built-in cupboard in the bedroom we used to share. The mirror would amplify the negative energy and encourage insomnia. My mother, taking the suggestion seriously, replaced the mirror with a pale and plasticky timber veneer. I still sleep poorly. The past and future continue to haunt. Although the faux utopia of the ideal city voids the suburban landscape of the ghosts we inevitably leave behind, I still see the ghosts here, here, and here, in car windows, antique shop windows, dental clinics and in the overgrown lawn outside train stations. And although many of these ghosts are the seemingly bittersweet remnants of a young child, I try to peer through their corporeal fgures, squinting through the obscurity of colonial history, looking for the voices among the late mangroves: the hope of the true ideal city.

Baudrillard, Jean. America, trans. Chris Turner. London: Verso, 1988.

Goodall, Heather. “The Picnic River: Pleasure Grounds and Waste Lands.” In Georges River Blues: Swamps, Mangroves and Resident Action, 1945–1980, 1st ed., 31–56. ANU Press, 2022. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2bks5h7.10.

Hokari, Minoru. Gurindji Journey : A Japanese Historian in the Outback. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs Dalloway. London: Penguin Classics, 2000. First published 1925 by Hogarth Press.

I didn’t mean to kill her...

It happened naturally. Of course, she wound me up. She was the reason for her own death. She was a constant example of attachment. A constant example of falling in love far too easily. She was a constant giver. I was there from beginning to end with her. I experienced every heartbreak with her. I was the only one who was always there. I’m a giver too. I really am. But I felt this constant need to take from her. I wanted to take her away from all the situations she stupidly put herself in.

I wanted to take away her memory of the older boy who touched her when she froze up in fear. She had only been 14. Her naivety got the best of her that time and he hurt her in more ways than I care to explain, but she didn’t learn. I wanted to take away thoughts of her dad who wasn’t the ideal father fgure we all long for. I wanted to take away her feelings for that ‘frst love’ she had in high school, who she knew deep down wouldn’t last. I wanted to take away the lasting anxiety because of that one drunk boy she let stay over that one night. She should’ve known better. She should’ve known what he would try to do to her.

The last heartbreak she had was the end for her. She didn’t seem to realise her inevitable fate, and I don’t know whether even the slightest part of her soul lives on. I saw it from the beginning with him. For goodness’ sake, she saw it too... She saw it from the frst time his hand landed on her cheek; she excused his reasoning, disregarding the disrespect that he implanted in her pores. Then, it was the lack of time that he gave her... her desperation for innocent intimacy grew so strong. Quality time was all she asked for. Basic. Human. Decency. Picture this: her, him, and porn starring a girl who looked nothing like her.

This is how worthless she was made to feel. So, do you blame me?

I wanted to take her kindness away.

I wanted to take her pain away because she was the reason for mine.

So I did just that. She stabbed me in the back, this wasn’t murder. This was retaliation. Self-defence. She was the type of storm that soaks you from head to toe as soon as you’re in its presence. There was no escaping. There was no point in trying. I sometimes miss her, the freedom that coincided with her love. I sometimes miss her empathy... You know, she always put others frst. That’s why I resent her so deeply. It was bittersweet. She was bittersweet. People left her with pufy eyes and a red nose too many times. I used to tell her she had no back bone. She never did like facing that truth.

She always seemed happy. But, if she was as honest as she made herself out to be, she would’ve saved herself from a lot of hurt. She would’ve saved herself from all the pity in her heart, she wouldn’t have lied to herself the way that she did. I’ll never forgive her for that. She was an actress. I remember how fake she was. I remember how she made others perceive her in such a diferent light to who she really was. A pathetic, hopeless, weak little girl. God, I’m glad she’s gone. I have a new girl now. She’s stronger, more real than the last. I guess I could say I’m happier with her.

I could be lying.

The girl I have now is a lot less joyful. She confronts people if they push her boundaries. She actually sets boundaries. She has standards that she sticks to and she can be difcult, but only when there’s reason to be. She doesn’t have the same joyful smile that the other girl did...

But what do I care? She’s gone. I don’t want to think about her.

This new girl doesn’t cry over petty sorrows. She cuts people out after the slightest lump in the throat, after the slightest ache in her chest. She doesn’t deal with those silly manipulative games that she can detect coming her way. Her love is more like a single thistle amongst daisies than it is like the last

girl’s vanilla and cinnamon endearment. I would say that I’ll never kill this girl, but frankly, I didn’t think I’d kill the other. And I didn’t think this new girl would be so cold.

I don’t feel warmth from her.

I don’t feel joy from her.

I don’t feel comfortable with her.

I can never tell if I’m ashamed or proud of what I did. In some ways it’s a mix of both. I know that I put her out of her misery, and that was my intention. But I was with my mum the other day, and I realised that if she knew what I’d done, she’d be so disappointed. It was strange. I had never thought about how my mum might feel. She loves this new girl, but I’m sure she enjoyed the old girl’s presence much more.

I see the way she softly smiles at old photos, the way she only glances over the new. I’ve felt the diference in her hugs: she doesn’t hold on as tight these days. I never thought about the love the old girl’s family had for her brilliant, energetic self. I wonder if they miss her as much as I do. My mum handed me a picture of myself smiling on my frst day of primary school. Amidst the nostalgia, the sad thought crossed my mind once again...

... I didn’t mean to kill her.

By Melody Wong

By Melody Wong

I thumb the sky; it purples. Stars tacked up, black and blue –plastic, incorrigible, I made this ceiling (just for you). The carpeted foor is my tender companion. I lie here (until the room grows strange).

I saw the blades of grass, the constellations of ladybirds on the park’s pale roses.

There was sunlight (this is true) and in the park, a girl. Her hair clip a metal diadem, her lips crushed mulberries.

We stole mint leaves stufed them in our pockets, crushed between my teeth the faming fragrance curled around my tongue –and I was alive.

Glaring into the eyes of the wind –

I did not cry, I did not cry.

Robby tells me to take a tab and look at the stars while he huddled over rolling us joints, giving me the illusion of the First Man working desperately on some tool for survival. My eyes look at everything and nothing but I can still imagine his hands in the dark next to me, fdgeting like a fy rubbing its insect-hands together, concocting evil machinations involving an unbalanced mix of tobacco and weed roughly guessed by the likely-dead light of the Saucepan.

I should tell you about the Saucepan. It’s a collection of bright dots in the sky that ended up there in such a particular way that they bring you back to earth the moment your mind starts wandering and thinking all sorts of unbelievable things. When existence seems too endless you see it and think of how hungry you are, of linoleum kitchens, of the fact that all of us just cook-eatshit-and-die until our cells mutiny and then gather in celebration amongst the worms in our cofns.

Robby prises my hand open and places the flter between my fngers. It’s poorly rolled but I’d never tell him that because I can’t roll and what do I know, and also, because I’ve never managed to fnd myself a wholesome person to buy my drugs from. They exist, but I’ve never looked hard enough and my friends are wholesome enough. Speaking of, I can’t remember how Robby and I came to be friends. Most people in my life just ended up being in it with no starting point, just a gradual fade from two souls in darkness to an inevitable companionship without any explanation of the time-in-between. He never ofers me the lighter frst, which I like, because I’ve always attached chivalry with romance and I want to be no less and no more than one man would be to another, except I am a woman, but I’ve never seen why that should change things that much.

Robby is (formerly) religious like me, which speaks for almost everybody from a small country town where, lacking other forms of entertainment,

praying to God becomes a hobby by virtue of having nothing else to do. So maybe we met at Church, which is highly likely because most of my friends grew up attending the Saturday 6pm mass – Catholic – so you sat imprisoned in forced piousness unless your parents were so kind as to let you scribble with dried-out textas while the Priest lectured greyly about Eternal Damnation. Afterwards we would fght on the Church lawns just to undo all that good work by throwing tree seeds at each other, you know, the ones that have sharp needle-like spikes all over them. They bruised with a bit of force and punctured the skin if you managed to hit bare arms or the backs of legs. There were two types, but you had to get the ripe ones that were green and heavy. The old seeds were brown and dead, the needles softened and the inside all hollowed out, feather-like. Useless.

This all took place whilst Father, Son and the Holy Spirit watched on and placed bets as to which kid would go too far and make another kid cry frst. Then it was ‘we better go home now, it’s late’ at the unreasonable hour of 7:30pm, when a procession of Toyotas, Nissans and Holdens would turn in either of the two directions on ofer to get home three minutes away. In fairness to my parents, we never left early. I take immense pride in that. Partly because my dad sometimes insisted on joining in in the name of character building, general toughening-up and the spirit of it’s-all-good-fun. It was.

The actual ‘church’ part was less fun. The crucifx hung over the altar, staring down at you in His moment of death with a dull expression that some artists considered a ‘modernist’ take on Ultimate Sacrifce. Yet despite this ‘abstract Jesus’, Church was a social event, fashion parade, a competition of who knew the most prayers word-for-word and of course, an opportunity to wage war in the aftermath. Life defnitely became less exciting when one day, our families all just stopped going and the ripe tree seeds piled up untouched on the lawn and those dried-up textas weren’t fought over by anyone and there were no cars rushing of at 7:30pm – because there were hardly any cars at all.

It did become more interesting at some point when hormones and alcohol and small-town restlessness led us racing past that old church on the way out of town to some Paddock Bash full of familiar names and around-town faces. Someone’s parents were always a bit more relaxed about the whole thing and

risked unlikely repercussions to buy us cheap wine or a pack of fake-fruit mixers that probably made you buzz more from the sugar than alcohol content. Next weekend it was by the beach, maybe a diferent crowd but the same sort of stuf. Robby would sit perched back in a spindly camp-chair with the drink-holder hiding a beer you had to drink, but somehow everyone knew it tasted like shit and you should really just be able to drink something you like. We all had our roles that we knew weren’t really us, but at the same time, we enjoyed the freedom of not having to be ourselves when we still didn’t know what that meant. I played along just fne, and I can’t say I didn’t have fun because I did. I really did. We performed the same little play every weekend and we got very good at it, and when the world around you is so small it’s nice to feel that you have a Very Important Place in it.

Robby fnally hands me the lighter and I sit up to catch the fame. I can’t tell you what we’d been doing that day, except that it was now halfway to midnight and we found ourselves by some sad old riverbed. There were supposed to be others but everyone else was on the burger assembly line or on the other side of town being abused by some bitter old woman for under-pouring her seventh glass of wine. Luckily we both had day jobs, Robby and I, so we got to be productive in our own ways by getting high and looking for satellites zooming between the stars like cars weaving through trafc cones. I tell Robby, play that song by Air, and sink back into the grass, turning my head to the side when I feel like another smoke.

The singers’ monotone voice sends me falling through the earth, my body swallowed up in tufts of grass and chocolaty soft soil, my arms and legs folding together as if caught in one of those hospital beds that snaps shut. I see my hands and feet sticking out at weird angles from the surface, knuckles white with fngers bent in all kinds of unnatural directions. I’m some kind of fucked-up plant sprouting slowly. Then I grow and unfold and there I am, lying fat on my back again, a joint undamaged between my fngers. Not even one ounce of dirt beneath my nails.

“Why do we keep coming back to this shit spot?” he mutters. I feel my eyes roll like marbles in his direction. “The river’s drying out, you can hardly swim in it anymore and it’s full of Bullrout. Gab’s sister stood on one the other day, did you hear that?”

“It doesn’t happen that often.”

“Often enough.”

“You know, Robby, you picked this place.”

“Yeah, well. Where else is there to go really?”

Now I couldn’t argue with this point because there really was nowhere else and we both knew it. In the silence between us I started picturing Bullrouts hiding between river rocks waiting to pierce our feet. They’re these ugly old fsh with sharp spikes along their spines that look like a rock and act like a rock until they see some tempting feshy toes and then it’s time for action.

They haunted our childhoods and flled us with enough fear that we’d strap thongs to our feet with duct tape when we went swimming. Still, some of my mates didn’t bother and I didn’t either half the time. During the summer the soles of my feet were so black and calloused that I’d pride myself on being able to walk across hot coals without finching by February. I never did that of course, but I could have. Despite my self-professed prowess, none of us could compete with Megsy, a friend of just about everyone. Megsy would smoke a cigarette and put it out on his bare heel.

You’d wince as he pressed the butt into the sole of his foot, expecting the skin to singe and fester and leave him screaming, but that cofn-nail had met its match. Megsy would laugh at our impressed horror and chuck the defeated butt into the fames, sip his beer, stretch out his toes by the fre and light another.

He was the King for a while, just on that one move alone.

Now, if it seems like we smoked a lot, or if I’m giving the impression that we did, we didn’t (Robby might have). In fact, I’ve hardly taken anything by many’s standards. I was too Catholic for too long and then by the time I grew up, I’d missed the window where you can do what you like and get away with it. However, as an exception, we did fnd ourselves by the riverbed on a mix of things tonight because our other friend had died a month ago.

When you’ve felt too strongly for too long you want to be numb, and then when you’ve been too numb for too long you just want to feel something. So that night we were trying to fnd a way to remember and forget, to feel sad and happy, to be mournful but grateful all at once for the person we’d known.

It wasn’t going well.

I kept imagining his body breaking down in a box amongst the rows and rows of other boxes, all at diferent stages of decay. Maybe some had already fnished decaying and were just… I don’t know. The funeral had happened a few weeks ago and let me tell you that it had turned me of motherhood forever. The seconds that passed while they lowered him into the ground were the longest of my life.

Have you ever seen a mother try and grab onto her child’s cofn as it’s being lowered, trying to pull it back up, grasping onto the rails with her hands so desperately that the groundsmen glance at each other nervously and try and fgure out how long to give her before they continue letting it down again? At some point, she laid down and kept holding on until the rest of the family had to wrench her hands away. Then she sat there in the grass sobbing in a way that you’d never forget for the rest of your life.

I remember throwing rose petals into the grave and holding onto a friend I hadn’t spoken to for years and never knew that well in the frst place. That day, I decided that I’d probably never have kids because if I ever lost one like that it would destroy me.

His mum joined him a week or two later. I always forget that detail every time I go to visit his grave, and I’m always surprised to see her gravestone right beside his, and then I cry a little more for that woman and for the fact that my mind made me forget her and what had happened. Because it did happen. My parents carted food around to their house like just about everybody else in town. I don’t know why we all do that. The food thing. Their family would’ve looked around at all that food going cold and old and cursed the fact that there were two less people there to fnish it all.

See, our friend that had died had once lived a little out of town on this pretty decent property with a river running through the bottom paddocks. The other day – so a very long time ago – we had gone bush-bashing along the river, and being the small, runt-like child I was at the time, I was forgotten at the back of the group in a tangle of vines and branches. There’s no moral to that story. I eventually freed myself and found them all because they were so damn loud, but for some reason when I think of him I think of that day and the jet black hair on the back of his head bobbing between the trees. He was marching us to an invisible war. He was charming, intelligent, hilarious, spiritual, one of those people that was so full of rarity and promise.

His death felt wasteful.

So, when he died I realised I didn’t want to be satisfed with a life like this and I honestly tried to change it. I moved away; I went to the city and studied something too ambitious. I hardly knew anyone, and everyone was cold and no one caught your eye and you couldn’t wish people a ‘good morning’ otherwise they thought you were ‘on something’. I felt my world open up and then sufocate me with its limitlessness and indiference. So maybe it didn’t make me happy, but it made me feel like I was doing Something and going Somewhere.

In the dark I can feel Robby staring at the night-sky and I wonder what he’s thinking about. Is it possible for two people to think the same thing at the same time? I’ve always liked to believe we’re more special than that but my mind is like a fsh out of water, always fipping back and forth in some desperate struggle to make itself up about whether or not our lives are all that important. My eyes fit between the Saucepan and the Universe.

“Do you think you’ll go back to Sydney in a few days?” he asks, and I can see the whites of his eyes shining in the not-quite pitch black.

By Amy Tan

By Amy Tan

Over the past two decades, the proliferation of social media platforms has increasingly led to the commodifcation of human activity as users try to ft into the new media landscape. Have you ever looked at the social media we are drowning in and considered our relationship with them? Are we benefting from the technologies, or, the other way around? Personally, I see technology to be benefcial to our lives. Spotify, which seems to align more with entertainment, could actually be considered as a social media platform as it allows users to create a personal profle, and interact with each other through sharing playlists and listening activities. These social media platforms have made it easier for an indecisive person like me to fnd entertainment in this world awash with information. However, that’s not what scholars such as Shoshana Zubof believe in.

In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Zubof argues that machine intelligence, such as Artifcial Intelligence and recommendation algorithms, has been leveraged by these companies to achieve their commercial goals.1 Consequently, netizens live under surveillance capitalism, a form of behavioural manipulation whereby enterprises use technologies to collect an excessive amount of users’ data footprints without proper consent to produce tailored content accordingly.2 Spotify, the music streaming giant that is preferred by many people, including myself, is the perfect example of this.

Spotify is more than just a streaming platform. It is a platform that mines users’ data copiously. It is no doubt that parts of the data go into services improvement, users’ personal information, including and not limited to basic personal data for creating an account and billing, users’ general locations, users’ interaction with the application (‘search queries’), users’ likes and dislikes, device sensor data and information from ‘certain advertising or marketing partners’. However, what is problematic is that such personal information

1 Zubo 2020.

2 Ibid.

can be shared with unspecifed third parties, such as ‘advertising partners’ and ‘marketing partners’.3

And that is not the worst turn of events. In the past, Spotify explained how they utilized users’ data to attract potential business partners.4 While this information can only be retrieved through the Wayback Machine (an Internet Archive website), it is still strong proof of how Spotify plans to ascertain users’ consumer behaviours, including their ‘ofine behaviour’.5 This is corroborated by Andrew Haldane, the Chief Economist for the Bank of England, who said that ‘data on music downloads from Spotify has been used, in tandem with semantic search techniques applied to the words of songs, to provide an indicator of people’s sentiment’.6 Such evidence suggests that Spotify has already turned its users into data and commodities to generate predictions for the company and its actual customers – other businesses. Importantly, Zubof explains this model as ‘enterprises that trade in its markets for future behavior’.7 This lucrative business model uses the music people listen to as a powerful ‘tool [for] understanding’ their interests and emotional proclivities.8 In the eyes of capitalistic companies, users are merely free raw materials they can use for proft. Isn’t it unsettling to have nearly everything known about you, just to be viewed as nothing more than data, and numbers.

Concerningly, the Pew Research Centre revealed that more than 36 percent of adults in the United States have ‘never read a privacy policy before agreeing to it’.9 This is particularly pertinent when Spotify’s privacy policy is so convoluted that it is considered very difcult to read under the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease test,10 making it even less likely for users/consumers to invest efort in protecting their data. Even if users could understand the terms and agreements, there is not much they could do about it apart from opting out of the platform entirely.11 Let’s be honest here, have you ever read the privacy

3 Spotify 2022b.

4 Spotify 2019.

5 Ibid.

6 Bank of England 2018, 12.

7 Zubo 2020, 17.

8 Attali et al 1985, 4.

9 Pew Research Center 2019.

10 Heinrich-Böll-Sti ung 2019.

11 Brewster 2015.

policy and terms of services before agreeing to it? I, for one, am always overly excited about the content hiding behind the wall of policies and just scroll to the bottom of the page with no hesitation. Do tech giants care if you truly understood the terms of not? At least Spotify doesn’t. It never informs its users about ‘the right to object to the processing of personal data or provide a means for individuals to object’, even when they are advised to use the data with consent.12 Such variables contribute to the asymmetry of power between Spotify and its users as the latter only have a diminutive knowledge of how their private details are used. This asymmetry of power has a deleterious efect on users’ autonomy. It challenges individuals’ fundamental rights, particularly their right to sanctuary, because their personal lives, including parts they unknowingly provide, are being reconstructed into data for companies’ proft.13 Ultimately, users now face a dilemma between privacy and commodifying themselves for ‘better’ services; however, this option is only available under the assumption that users have a choice.

In fact, users have lost their autonomy, and will only lose more as they attempt to survive in this technology-focused era. This can be explained by Zubof’s notion of ‘instrumentarian power’, which, in simpler terms, means that companies are using their excessive grip on users’ behavioural data to shape users’ actions towards a certain end.14 This grip is deepened by what she called the ‘economies of action’: tuning, herding and conditioning, which could be exemplifed through Spotify’s model and marketing campaigns. As music streaming platforms account for 65 percent of the revenue of recorded music,15 Spotify has shifted the balance of power in the music industry, pressuring musicians to stay relevant to survive. Sam Wolfson, a freelance music journalist, argues that Spotify has changed how music is being made: songs’ intros are now shortened to prevent users from ‘skipping a track with a slow buildup’ and albums have included more tracks because longer albums can help increase revenue.16 Due to the popularity of Spotify’s playlists, it has become proftable to modify songs in hopes of getting onto playlists created

12 Heinrich-Böll-Sti ung 2019.

13 Zubo 2020.

14 Ibid.

15 IFPI 2022.

16 Wolfson 2018.

by Spotify.17 Such playlists are known to have a ‘more dominant position on the page than those created by other actors’18, which could help Spotify and artists get streams and thus increase revenue. Spotify further supports this phenomenon by ofering tutorials to teach producers how to interpret data,19 increasing the chances of artists conforming to the algorithm. As algorithms prevail and dominate, artists, especially indie artists, are infuenced to believe in a reality where one has to tune into a new, algorithm-driven music landscape to thrive.

You might be asking yourself – why should I care? I like the personalisation function that makes random songs show up on my ‘for you’ page and makes entertainment more accessible for me. And I agree. Every time I am on my Spotify homepage, my eyes are subconsciously drawn to those (eerily) personal ‘Made For Melody’, and ‘Your top mixes’ playlists, then you can often fnd me drifting through these curated playlist black holes for days.

There are times I found good bops and good artists that I wished I knew earlier, but not having to actively look for the songs that I want makes me wonder if the decisions that I am making are not what I’m meant to be making; if my thoughts are not original anymore.

Spotify has employed similar conditioning techniques for another type of user – us – people who stream music on the platform. By ‘[tailoring] improved experiences to [their] users, and [building] new and personalised products’, streaming services such as Spotify adapt their services to users by giving them what they want instead of overtly changing their decisions (Collins, 2015). Under this infrastructure, users no longer have to actively search for music that fts their palate. Voigt, Buliga and Michl note that ‘Spotify subscribers don’t pay for content – they can get that for free through piracy – they pay for convenience’.20 This sense of convenience is exemplifed in their marketing campaigns, ‘music for every mood’, which entails that Spotify can give you easy access to content21. Gustav Söderström, Spotify’s Chief Research & Devel-

17 Ibid; Forde 2017.

18 Åker 2017.

19 Spotify 2022a.

20 Flynn 2019, 14.

21 Cirisano 2019.

opment Ofcer, said, ‘Over time, we see again and again, convenience trumps everything’.22 This sense of convenience – (somehow) getting song suggestions that one likes as they shufe through a random playlist – traps users too far deep in this fallacy. A fallacy where users believe they have the autonomy to jump from song to song, when in fact, they are unknowingly being herded towards a direction that Spotify has predicted. they are practically manifesting Spotify’s visions – making decisions Spotify wants them to make. Users are constantly acting under the illusion of choices, dictated by the recommendation algorithms that are based on users’ electronic footprints. Your private life, including your listening habits, is ironically becoming a weapon against your music taste. This makes users an easier target to squeeze data out and an assistant in this game of power acquisition, completing the feedback loop.

The recommendation algorithms of Spotify reveal the tech giants’ invasive nature, especially in the social media industry. Despite the convenience created by personalised playlists and content, there is a clear trade-of. Users are forced to give up their privacy and autonomy to a large extent in the name of enhancing users’ experience. We are not listening to songs that we want to listen; we are listening to songs that Spotify specifcally wants us to listen to –we are living in a world where our decisions are no longer completely autonomous, our thoughts are not as original as we thought they were. And we will only live under its grip unless we gain a better understanding of the way tech giants do businesses – what helps them remain free or freemium.

Ignorance is not bliss when everything about you is for the world to see and use. Advocacy works, can be successful and should be put into the spotlight to remind users of their right to protect and own their data, especially in a paradigm increasingly shaped by corporate digital interests.23 Were you spoon fed the songs you are listening to? I think, unfortunately, I will continue to use the platform for a much longer time. I will not lie, it is indeed hard to leave the grips of something as convenient as Spotify. But I hope this can be a reminder that we should start refecting on why we love social media and seek out its hidden agenda, especially when we could be glued to it for a long time.

22 Bloomberg 2021. 23 Zubo 2020.

Reference list

Åker, P. (2017). Spotify as the soundtrack to your life: Encountering music in the customized archive. In Streaming Music (pp. 81–104). Routledge. https:// doi.org/10.4324/9781315207889-6

Attali, J., Jameson, F., McClary, S., & Massumi, B. (1985). Noise : the political economy of music. University of Minnesota Press.

Bank of England. (2018). Will Big Data Keep Its Promise? https://www. bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/fles/speech/2018/will-big-data-keepits-promise-speech-by-andy-haldane.pdf?la=en&hash=00A4AB2F080BDCDB1781D11DF6EC9BDA560F3D98

Bloomberg. (2021, August 10). How Spotify won the world’s ears by prizing convenience (Cornell Tech @ Bloomberg). Bloomberg. https://www. bloomberg.com/company/stories/how-spotify-won-worlds-ears-prizing-convenience-cornell-tech-bloomberg/

Brewster, T. (2015, August 20). Location, Sensors, Voice, Photos?! Spotify Just Got Real Creepy With The Data It Collects On You. Forbes. https://www. forbes.com/sites/thomasbrewster/2015/08/20/spotify-creepy-privacy-policy/?sh=28c60d99413a

Cirisano, T. (2019, January, 05). Spotify Launches New Meme-Inspired Global Ad Campaign. Billboard. https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/spotify-launches-new-meme-inspired-global-ad-campaign-8509606/

Collins, K. (2015, August 21). Why people are stressing out over Spotify’s new privacy Policy. Wired. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/spotify-privacy-policy-outrage

Flynn, M. (2018). Back to the Future: Proposing a Heuristic for Predicting the Future of Recorded Music Use. In Popular Music in the Post-Digital Age: Politics, Economy, Culture and Technology (pp. 211-234). Bloomsbury Publishing Inc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501338403.ch-010

Forde, E. (2017, August 17). ‘They could destroy the album’: how Spotify’s playlists have changed music for ever. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/aug/17/they-could-destroy-the-album-how-spotify-playlists-have-changed-music-for-ever

Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. (2019). Privacy In the EU and US: Consumer experiences across three global platforms. https://eu.boell.org/sites/default/ fles/2019-12/TACD-HBS-report-Final.pdf

IFPI. (2022). Global Music Report 2022. https://www.ifpi.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/04/IFPI_Global_Music_Report_2022-State_of_the_Industry. pdf

Pew Research Center. (2019, November 15). 4. Americans’ attitudes and experiences with privacy policies and laws. Pew Research Center. https://www. pewresearch.org/internet/2019/11/15/americans-attitudes-and-experiences-with-privacy-policies-and-laws/

Spotify. (2019). Spotify For Brands [Web log post]. Spotify. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20190612090952/https://www.spotifyforbrands.com/en-US/audiences/

Spotify. (2022a). How to read your data. Spotify. https://artists.spotify.com/ video/how-to-read-your-data

Spotify. (2022b). Spotify Privacy Policy. Spotify. https://www.spotify.com/us/ legal/privacy-policy/#spotify-privacy-policy

Wolfson, S. (2018, April 24). ‘We’ve got more money swirling around’: how streaming saved the music industry. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/apr/24/weve-got-more-money-swirling-around-howstreaming-saved-the-music-industry

Zubof, S. (2020). The age of surveillance capitalism: the fght for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAfairs.

By Amy Tan

By Amy Tan

For as long as they have existed, the arts – whether it be visual arts, music, dance, theatre – have proven to be the lifeblood of social movements. Artistic spaces have helped to sustain the social role of art in building and promoting activism, directly infuencing how we view the world. Sydney University’s Tin Sheds Gallery is no exception.

Established on our University’s campus as an autonomous art space in 1969, the Tin Sheds remain open as an exhibition space today. Throughout the 1970s, the Tin Sheds operated as an independent art studio where established artists, students, academics, activists, and art-based political collectives met and created. The original site for the Tin Sheds was located where the Jane Foss Russell building now stands. According to the Tin Sheds’ website, during the 70s the Sheds were used as ‘a creative space for artistic experimentation and the development of studio based contemporary visual arts practice, to complement (or possibly counter) the theory-based visual arts teaching of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Sydney.’1

Indeed, in a 1979 special edition of Honi dedicated to the Tin Sheds,2 it was noted that the development of the Tin Sheds was ‘organic’ and ‘dictated by the demands of the people using the facility… NOT set up to fulfl the aims of bureaucrats, planners and so on.’ Existing outside the bounds of University administration or their oversight, the Sheds were akin to the autonomous collectives we know today, who often stand in direct resistance to the University.

During the 1970s, the Tin Sheds housed numerous poster collectives, adding to the broader counter-cultural revolution that shaped the socio-political landscape of Sydney in the 1970s. These poster collectives were political groups formed by artists who concentrated on promoting awareness of social issues through their artworks. Collectives included the Tin Sheds Art Collec-

1 University of Sydney 2023.

2 Honi Soit 1979, p.11.

tive, the Lucifoil Poster Collective and the EarthWorks Poster Collective. These underground organisations were foundational to the propagation of activist messages both inside and outside of the University grounds, employing art as a means to inspire and generate activism around social issues such as Queer rights, pro-choice movements, prison reform, and Land Rights.

In particular, the EarthWorks Poster Collective, an art collective aiming to distribute activist messaging around social issues such as feminism and Aboriginal Land Rights through screen-printed posters, played a major role in the art-as-activism sphere of USyd during this era. Founded by the counter-cultural advocate and artist, Colin Little, this collective was associated with the Tin Sheds from 1972 to 1980. Other activists involved in EarthWorks included Jan Mackay, Marie McMahon, Pam Ledden, Di Holdway, Loretta Vieceli, and Toni Robertson, to name a few. Many EarthWorks artists were not only visual art students at the University, but were also involved in other areas of activism, namely feminism and environmental political groups.

The collective also made posters for political groups, including the 1983 Pine Women’s Peace Camp – a feminist camp held outside the Northern Territory’s Pine Gap protesting the location of an American intelligence base on Australian soil. Archives of these posters and posters from other Tin Sheds art collectives can be found in the State Library of New South Wales, the National Gallery of Australia, and here at Sydney University.

Unfortunately, the collective dissolved in 1979 due to a lack of funding. However, the campaigns run by EarthWorks continue to inspire present day activism; for example, the legacy of the Earthworks Poster Collective can be seen in those ‘banner paints’ which USyd political collectives still conduct today in preparation for protests and strikes.

By the end of the 20th century, the activist and artistic work carried out at the Tin Sheds was incorporated into coursework as part of Sydney University’s Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning. However, the Tin Sheds remains a space for all Sydney University students to create – whether or not this involves architecture models or paintings – and exhibit their art to the public, albeit being no longer under autonomous student-led control.

Ultimately, the history of the Tin Sheds reminds us that art remains a powerful force of activism. Located right here on our Camperdown campus, the Tin Sheds have provided past activists with a space of creation – infuencing how we foster and communicate social causes in the modern world. Today, as we witness the climate emergency, the continuing impact of colonisation on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and the attempts to resist homophobia and sexism, art remains a powerful force to inspire social change. You only have to look at the many posters still pinned to poles and notice boards on Eastern Avenue today. The history of the Tin Sheds and indeed art-as-activism remains incomplete; we must be the ones to continue its legacy.

The Tin Sheds remain on campus.

Note: This is an edited version of an article that was frst published in the student newspaper, Honi Soit.

Honi Soit (1979). “10 Years at the Tin Sheds: Issue 4.” Honi Soit, March 19, p.7, p.11. https://digital.library.sydney.edu.au/nodes/view/3997#idx28578

University of Sydney (2023). “Tin Sheds Gallery: About the Gallery”. Accessed from https://www.sydney.edu.au/architecture/about/tin-sheds-gallery/ about-the-gallery.html

‘Tis the season to be holy. All your Muslim friends are fasting. Every year, there is an eerie quiet on Eastern Avenue at sunset. Many have left campus, keenly awaiting iftar time. And when the Azaan – call to prayer – resounds, it’s time to feast on your favourite once-a-year dishes. It’s about time we shine a spotlight on some of these deserving iftar items that make most Muslims weak at the knees.

Before we go further, let us unpack this elusive term, iftar. By formal translation, iftar is a meal eaten after sunset by fasting Muslims in Ramadan. To me, iftar also means family, love, community, and piety. My earliest memories of iftar centre around family – helping my mother set the table, the sounds of Islamic radio, the conviviality of evening meals sitting on the foor balancing plates of food and drink. At iftar time, Muslims believe that Allah (SWT) shows special mercy and love to those who have been fasting, and especially to those who have provided food for others. And after having no food or water (yes, even water) during warm Aussie days, iftar is very welcome. So, in honour of this communal spirit, it only felt right to ask others for their verdict on their top iftar preferences. Ten fellow USyd students have been surveyed, and their responses are ranked and tallied in order from ‘Mmm that’s good’ to ‘Ahh I have totally ascended’.

Coming in piping hot at number fve is none other than the humble soup. One student made the health conscious statement – ‘lentil soups are really replenishing and fulflling,’ while another opted for the more blatant remark – ‘love that shit.’ Lentil soups have been a staple in iftar for centuries, often served alongside assorted meats and vegetables. In Arab iftars, lentil soups (Shorbet Adas in Lebanon and Mercimek Corbasi in Turkey) are rich, creamy, and hearty. In Bangladesh we fnd a soup-er curried stew, Halim. This dish, served with a sliver of lemon and dash of garlic satisfes the heart.

5.4.

While we’re on the healthy trend, we must reserve a place for our favourite high vitamin, non-guilty pleasure – fruits. Almost all the surveyed students named some sort of fruit, with some citing ‘fruit platters’ and others drooling over specifc fruit dishes such as the Egyptian Khoshaf. But for most, the queen of fruits was easily Miss Watermelon. When all asked why she was a fan favourite, one student said, ‘THE BEST – so refreshing.’ Watermelons store over 80% of water which keeps tabs on dehydration. And somehow, she seems sweeter during Ramadan. It’s almost as if she knows she’s the it-girl of the season.

3.

If you do not have fried goods on your platter after a long day of fasting, you are either lying to yourself, a vegan, or built like Michelle Bridges. In terms of oil quantity, South Asian iftars could compete with McDonalds. Deep fried novelties like Chicken Samosa, Pakora, Beef Patties, and Beguni leave you feeling whole. The crackling sounds of oil from the kitchen right before sunset, and the loud crisps when breaking into steaming pastry are unparalleled memories. After iftar, a lot of Muslims burn of the extra calories gained through the 20 rakah Taraweeh (prayer). The prayer is a time of refection and spiritual growth, as well as physical exercise, and it is an important part of the Ramadan experience.

2.

Contrary to popular belief, water is criminally underrated during Ramadan. Most Muslims opt for its bejewelled cousins – Tang cordial, mango smoothies, and strawberry milkshakes. But there is just one beverage that reigns above all. To some it tastes like heaven, to others cough syrup, but like caviar, it is truly an acquired taste. Rooh-afza, arguably the most Ramadan drink there is. Originally from Pakistan, the very scent of this sweet scarlet punch brings forth memories of fasting.

1.

Dates. That should come as nobody’s surprise. It is highly likely that you won’t fnd dates in the markets during this month since most of the bulk wholesale packs will be stacked in my fridge. All of the surveyed students listed dates somewhere on their list, with many admitting that it is their number one most satisfying iftar item. Walnut stufed dates were also a popular alternative among respondents.

But why dates? One student summed it up beautifully, writing, ‘Slay.’ They later elaborated, ‘dates really are great for all the sugar lost during the day. They’re also Prophet approved.’ The signifcance of dates in Islam harks back to the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) who is noted to have broken his fast with dates and water. This is considered Sunnah, or a model of behaviour for Muslims to follow. If you don’t have a date at the sound of the Azaan, your Mum’s coming for ya.

As fawless as this list is, it is of course difcult to rank food items that we are lucky enough to see at our tables. Ramadan is a time of gratitude for what we do have, and a time to think of others less fortunate. So, next Ramadan, practice giving thanks, gift your Muslim friends a watermelon, and for god’s sake, don’t let your intrusive thoughts pop the ‘not even water?!’ question.

Note: This is an edited version of an article that was frst published in the student newspaper, Honi Soit.

The curtains were drawn as I looked on from the frst row. I stared at the little ritual, not emotional, but not entirely distant either, as the motor whirred and the casket rolled away into a fery consummation. Death always looked better in Shakespeare. Hamlet’s old man got poison in the ear, and Polonius was dispatched by a curtain. All she got was a funeral chapel with some near-strangers in the seats, looking blankly as a Priest she never knew said the usual, boilerplate stuf about love, and honour, and hard work.

I hadn’t known her that long, really. Yet I felt I had always known her: that familiar smile that cracked gently at the sides of her mouth, the kind-hearted look as I came through the door. Always the same, always welcoming. One noticed just how tall she was at frst, the height towering in under door-frames and trees. It seems odd that it all ended so abruptly. A few lines in the paper here, a bouquet of wilting fowers there. There was a coldness to it all; a conveyor-belt rehearsal about the death. It was almost as though the vicar, the undertaker, and the lady playing Jerusalem on the old electric organ had seen it all before. Of course they had. She was the second one that day.

What I knew of her life, I knew in pieces. Born in India, the daughter of an expat academic, she was sent away to one of those rather Dickensian boarding schools and then on to Melbourne for Philosophy and Law. The whole sort of quasi-Raj upbringing put the zap on her. At 21 a letter was sent to her father, aging disgracefully somewhere near Shimla.

Even though she had never played, she joined the tennis club near me on retirement. There’s a delicacy to it, as a sport. The repetitive motion of the forehand, the smell of fresh-cut lawn. But she wouldn’t touch a racquet. She had, by the account of those who I spoke to after the funeral, had always avoided organised activities. It was, if anything, a nice place to eat lunch. I too was no great player. Most of my family had belonged there and joining was the “done thing.” Both of us, therefore, settled into an equally uneasy routine.

When I noticed she always lunched alone, I decided to go over. It felt like the right thing to do. After delicate introductions we became one of those accidental friendships, a sort of happy coincidence, something that I managed to keep up for years. We would have lunch and talk. Or rather, I would talk and she would nod, occasionally looking up from her food to mumble quiet approval of the topic. I doubt really that she wanted to be there, or that, at least, she ever wanted to speak to me.

She was guarded. I would always ofer to buy cofee, but she was insistent we have iced water. When it came I’d see her through the convex end of the glass; her features distorted by water, ice and the almost flm-like layer of condensation that gathered on the cup. We did this for over fve years. One day, as I was leaving, I noticed her take a notepad from her handbag and begin to write. The club steward said she came every Wednesday and followed the same pattern.

I arrived the next week and found an armchair with a view of proceedings akin to that of the Speaker in parliament: above the fray. She didn’t see me, for this week she was sitting at a corner table, facing away from me. The woman ate the same lunch every time. The soup of the day and cold water. Then she retrieved the notepad and an old pen, one of those large, submarine-like fountain pens. She wrote for nearly half an hour, then packed up and left.

Not once in the years before her death did she ever mention an illness. Any elephants in the room were led out the back door by a talented handler. I guess that’s why she always sat facing towards the room, and I, looking out over the tennis courts. Easier to hide the elephants that way.

It was a Tuesday when the Herald landed on the doorstep with a resounding thud and I went over to the obits page, if only to make sure I wasn’t there. Being in my twenties I’d never seen anyone I knew in it, at least not yet. There she was, in black and white. The article stank of newsprint; of the sub-editor’s pen scratching without feeling across the typescript that someone must’ve sent in after the goings-on of death were over.

The funeral was later that week. Some people from the club were there. A few lawyers, better-dressed than the rest of us and with a typical arrogance about them, stood in the corner of the church, expressionless behind their half-moon glasses. The priest and one of the lawyers spoke. I remember he talked like a barrister - everything was carefully set out and nothing was unnecessary. What I don’t remember is what he said. Not worth remembering. After the charade, the cofn passed through the curtains and out of our lives forever. I knew her, but I never knew her.

She came back into my life a few weeks after the funeral. One of the waiters from the club came over, holding the diary. “She wanted you to have this,” he said, and thrust the book into my hands.

It was well written, almost literary in its prose. Not a diary, but not a memoir, she had written in the front cover ‘Remembrance from beyond the looking-glass.’ Nearly Proustian. I reached for a madeleine, but there were no little French biscuits. One would have to make do with her words.

Here it was. India. University. Her law practice and her life. The collected observations of a human life, bound up in a little leather volume. I never knew the lady in life, and yet, in death, I looked beyond the plane of the real and began to tread carefully into the more delicate, opaque world of her inner experience. How am I meant to know someone when I never really had the chance?

I had picked up snatches, little hints here and there of the person she was. A group of us went to her house after the funeral. Laid conspicuously on a table was a box of old photos. She must’ve been reminiscing in her twilight. I picked one up without looking. It was curled at the corners and waterlogged. She was young, then, wearing her legal wig and gown, but it was still clearly the same fgure. All this was just someone else’s viewpoint of such a person, of this lady long-talked about as an enigma, one of those people that well-meaning types call “eccentric” when they really want to patronise and judge.

What is it about the people we know? We go through life thinking that we know them, even when they say so little about themselves. How could I have ever known her? I knew her name, could recognise her by face but to know someone like her seemed impossible, when she lived a life almost alone. I spoke to some other friends of hers. We all thought we knew her, but none of us ever knew her. This life, a life we shared, remained marked by its opacity more than its clarity.

If anything, I have only known her in death. It feels quite roundabout, that one so guarded in life is so open in death. It should be the other way round. When I fnished reading I felt far more confused than before. It was late in the afternoon. The sunlight began to dip below the horizon, and her life seemed to fade away into a darkness as unclear as the night. If anything lay beyond the looking-glass, it was beyond my vision.

By Yasodara

By Yasodara

After Tom died, Marjorie was given three casseroles. One from her next door neighbour Gracie, one from her daughter’s mother in law Maureen, and a third from her friend Carol. Marjorie planned to handwrite a thank you note to each, which she would place on top of a clean, folded tea towel inside the gleaming casserole dish she would set on each doorstep.

Tentatively, Marjorie poked at the hardened glob of cheese stuck to the bottom of Carol’s dish, fngers protected by a set of bright pink latex gloves. The dish had been left out on her kitchen counter for fve days, half eaten, as Marjorie had spent the working week ordering Chinese takeaway and making steady progress on Tom’s whiskey collection. At some point she had put the whole monstrosity in her dishwasher, running two long cycles over it before leaving it to fester for a few more days. The thought of lifting it out and giving it a real going over had seemed like an insurmountable task. But, her two children had promised to visit her this weekend, and there was a clear agenda to their interest in her.

They wanted Marjorie to assure them that she was just fne, thank you very much. That now, two weeks after Tom’s death, they were released from their duties. No more phone calls at bedtime, or popping over on their days of. They would expect the house to be in order, at least. So, Marjorie had to tackle the grotesque week-old beef casserole and detergent gunk sitting in the bottom rack of the dishwasher. After all, Carol would want her dish back. Especially since it was customary to send your best casserole dish over to the bereaved.

Marjorie lifted up the dish and placed it gingerly in the sink, running the hot tap over it to loosen the hardened crust of greyed tomato and cheese. That was the thing about loss, it robbed you of the person who remembered to rinse of the dishes thoroughly before putting them in the dishwasher. Of the

person who didn’t think it was a personal injustice that you had to put dishes into the dishwasher practically sparkling clean. Bloody waste of money, she thought, then realised she sounded exactly like Tom did when she pitched the idea of getting it in the frst place. Marjorie squirted the last of her bottle of Rinse-Aid into the main wash compartment and slammed the door closed, turning it on to run again.

Whenever tragedy struck, Marjorie cooked determinedly – she was of a generation of women who knew that in a world where nothing was promised, there was a comfort to be found in certain practical things. It was always amusing. The way women fussed around the kitchen after a tragedy: at once misguided and unyieldingly wise in their belief that everything would seem a little better after a hot meal.

Marjorie had made a lasagne for Carol after her son David committed suicide two Januaries ago. And an apple pie, wrapped in a red chequered tea towel, with a litre of Sara Lee ice cream balanced on top. The condensation from the ice cream container had made the tea towel damp beneath it, but it was important to show Carol how sorry she was. In fact, everybody had gone to an extra efort on account of David being so young and good natured.

That was another thing about loss: you had to admit some losses were bigger than others. There were the big, juicy devastations that happened to young and beautiful people, and the quieter losses that didn’t make anybody very sad at all. It was true, Marjorie thought as she attacked the glass dish with a piece of steel wool: there was no appetite for loss when it’s mundane. By nature, tragedy was reserved for a special class of people, only worth anything as long as it was newsworthy. Marjorie had a lingering sense that there was no news value to a 68 year old widow whose husband had smoked like a chimney. No beautiful mystery: all questions answered, all things accounted for. He’d even signed up for premium health insurance; they hadn’t paid a cent for his treatment. Woe was not her.

Truth be told, Marjorie’s children had thought he was a grumpy old bastard by the end of it. They had had enough tact to pay for the funeral, and chose a good, solid casket. It was made of golden brown cedar wood, with brass

handles that winked under the fickering lights of the funeral home. Marjorie had loved the casket. It was elegant and charmingly antiquated, the type of thing that Tom would have run his hands over remarking on its good construction.

Marjorie gagged as she scrubbed of a spongy lump of gristle, revealing its underside dotted in blue and green spots of mould. She wondered if this was how David was found: smelling like rotten eggs, fat beginning to separate from the bone. He was cremated. There was no question of an open casket that she remembered. Perhaps there was no question of a closed one either –on account of that terrible smell. He had died from a paracetamol overdose on the shoulder of the highway, and by the time they located his car it had spent days baking in the sun. They must have had to scrape him of the seats. Tom had been found peacefully by the nurse at his 6am checks. He was swiftly wheeled down to the morgue within minutes.

After David’s death, Marjorie had been over to Carol’s house a lot. Stocking the fridge, wiping down the counters, feeding the dog. Carol’s husband would shut himself in the study while she was over, but Carol herself was desperate to talk, sitting on the couch in pink pyjamas, telling her to stop fussing and to sit down and watch television with her. After Marjorie would come home, she’d share her every observation with Tom. Tom was too proud to ask, but he would always listen intently to each piece of gossip Marjorie shared, occasionally chiming in to declare someone an idiot. Then, late at night, Marjorie would lie awake thinking about David. She wondered how the nice young man who had once mowed her lawn would do such a thing, how all the while he was planning something so awful. People didn’t think Paracetamol would be painful, it was a painkiller after all. But it was. Terribly. That, she’d kept from Carol.

Marjorie rinsed out the dish and attacked it again with the sponge. Carol had said that the moment she found out about David, she’d felt like she’d been stabbed in the gut – an unfathomable amount of pain hitting all at once. But, if a sudden loss was like a knife driven through your ribs, a slow one is like starving to death. You have time to focus on each pang of hunger as it comes for agonising weeks, long before the real pain begins. Marjorie felt a

sting of jealousy and shame as she imagined Carol and her husband sitting together later that night, discussing how sorry they felt that she would spend her twilight years entirely alone. That was the last thing: loss made you uncharitable. Marjorie looked down at the dish in her hands, watching little yellow fecks of her sponge crumble of in the soapy water and foat away down the sink.

if i just remember –the way bees are holy to me and sparrows stained glass the way citrus smells like sunlight and dawn tastes crisp and cold like the earth like apples

if i hold on and remember that summer is a yawn and a stretch of young and alive that i swam through to get here –i’ll be home again, and we’ll help each other, again.

you’ll learn knees were made to bend / crack / creak / tremble, and i’ll remember that wild hearts outpace time

we’ll pull down the blinds turn on our eyes and just stare

we’ll lay in our bed, lie to the world and make ourselves real,

with held hands and these words: i \ me \ my \ we

but out here it is bitter cold and dark, stars a fction and the moon absent, a gaping hole left behind that i cannot climb through yet.

for us, tonight, please please please? exist tenderly and gratefully (never gracefully) and we’ll dance again, barefoot when the night is soft and sweet.

By Yasodara

By Yasodara

From Sigmund Freud’s id, ego and superego, Parft’s identity criticisms, Aristotle’s aphorisms of personal identity to the treacherous unchartered waters of Eastern Avenue; knowing who, what, how, why we are who we are is a complex journey of self discovery.

And quite frankly, USYD’s students don’t know who they are.

Navigating campus identity from orientation to graduation day is a tentative equilibrium that prescribes social standing for every university student. Put simply, this experience is a looming inevitability. For many students, identity is inherently linked to creating a legacy, a social group or an impact through their educational discipline. For others, it is the most terrifying echochamber of pride-infused self-importance. Let’s unpack this elusive, complicated and fatiguing reality of student identity.

Often, the loudest voices provide an idealistic model of community and individual expression. But what if we don’t have fyers in our hands or a megaphone attached to our hip? Perhaps the theatre and SUDS groups are a fruitful social exercise? Or maybe building our gentility with law students can support our social standing? Potentially the change stirrers of our engineering minds can catapult our success? Maybe we can go on an investigative foray hand in hand with our greatest history decoders? But where does that leave us?

Do we look to our greatest philosophers? Like Derek Parft’s iterations of identity philosophy? Or to our instagram feeds and pinterest boards?

If we don’t embody a commonly accepted convention, then we occupy a sort of purgatory between student and individual where we fght to carve out our own identity. That’s not to say our powerful stupol community is steering

our ship south. Or the Law and Engineering students’ noses are blocking the shade. It is anything but. Taking away the student aspect, discovering who we are and what we stand for is a challenging reality of the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. This reality is arduous regardless of which social sphere we choose to occupy. Some students have the sole mission to soundlessly fy under the radar but others fght to make cataclysmic waves. For many, university and social interaction is a confusing anomaly.

Personally, I changed degrees three times. I didn’t know who I was academically, let alone personally or socially. I felt like a fraud in all three degrees. And sometimes still do. Navigating the tempest of campus life truly is a balancing act but when combined with staying afoat academically, social identities become claustrophobic. No one can deny the infuence that your degree composition has on your identity compass which adds another layer of pressure.