TRADIÇÃO E TRANSGRESSÃO EM REI LEAR

Para o desafio de conceber uma cenografia possível para a encenação de Rei Lear, tragédia de Shakespeare, no espaço do Armazém da Utopia no Rio de Janeiro, adotou-se a interpretação da obra oferecida por Jan Kott em seu ensaio “Rei Lear ou Fim de Partida” (In: KOTT, Jan. Shakespeare, nosso contemporâneo. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2003, p. 125-157).

Para Kott, o caráter trágico da obra shakespeariana observado nas grandes produções cênicas do período romântico se perdia ao aplicar-se a tradição elizabetana de pouca ou nenhuma cenografia. Assim, “(...) esse velho louco, que arrancava fios de sua longa barba, tornava-se de repente ridículo. Ele devia ser trágico, mas não o era mais” (KOTT, 2003, p. 127).

| See the

English

|

end for an

translation

O trágico é então substituído pelo grotesco, na visão de Kott, comparável a Fim de Partida, obra de Samuel Beckett:

(...) a tragédia conduz à catarse, enquanto o grotesco não oferece nenhum consolo (...). Já o teatro grotesco moderno, costuma ter por cena a civilização pura; a natureza está quase totalmente ausente dele. O homem está encerrado numa peça, acossado por coisas e objetos. Mas as coisas desempenham atualmente o mesmo papel de símbolos da condição humana e da situação do homem que a floresta, a tempestade ou o eclipse do sol em Shakespeare (KOTT, 2003, p. 129-130).

A essa visão da tragédia shakespeariana somou-se a compreensão de Fim de Partida como situada em um cenário pós-apocalíptico e a própria ideia de reino fraturado presente em Rei Lear para chegar-se ao conceito principal da proposta: uma cenografia que transgride o binarismo natureza-civilização, construída por remanescentes de uma civilização a tal ponto deteriorados que mais se assemelham a paisagens inóspitas da natureza.

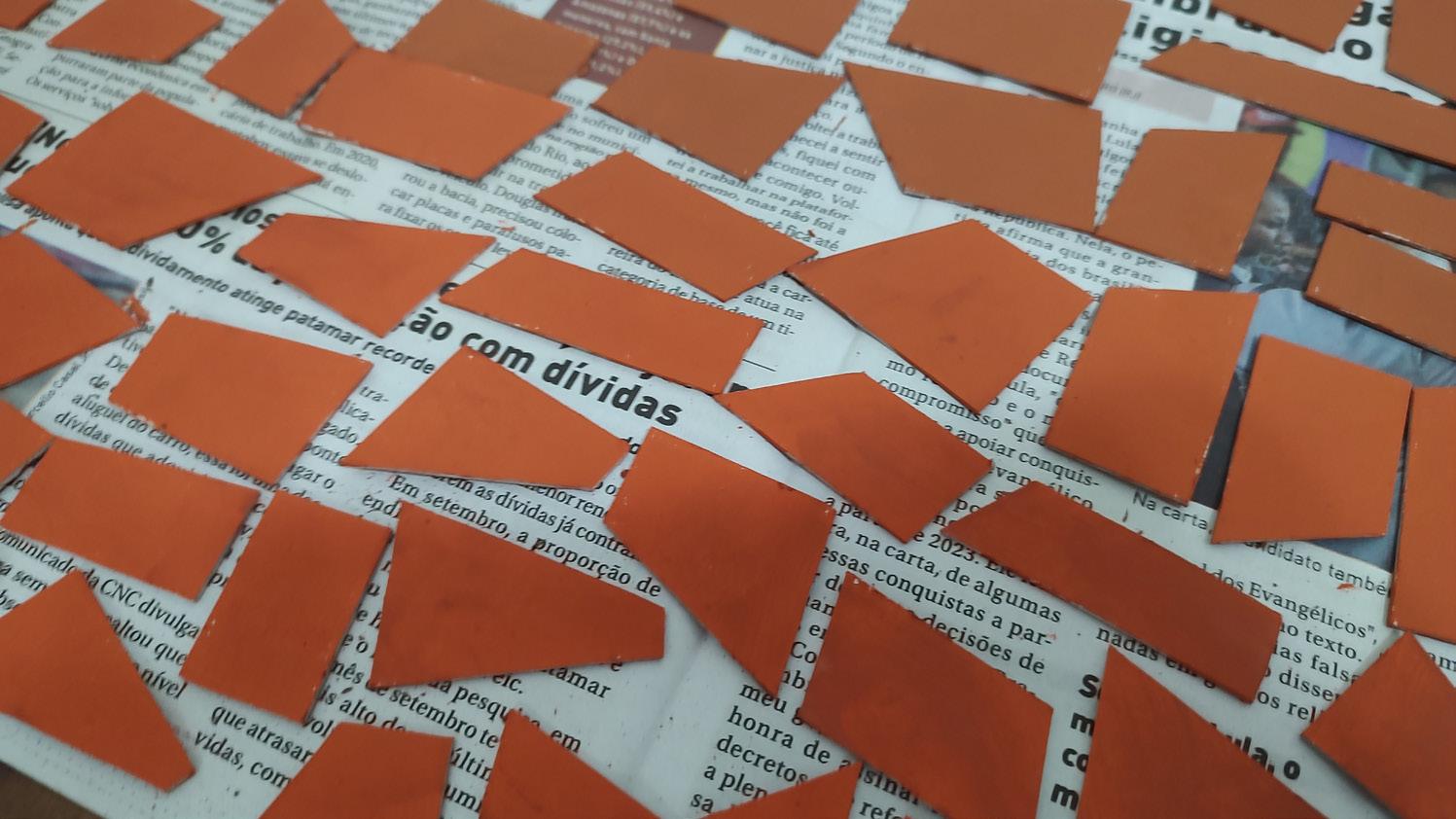

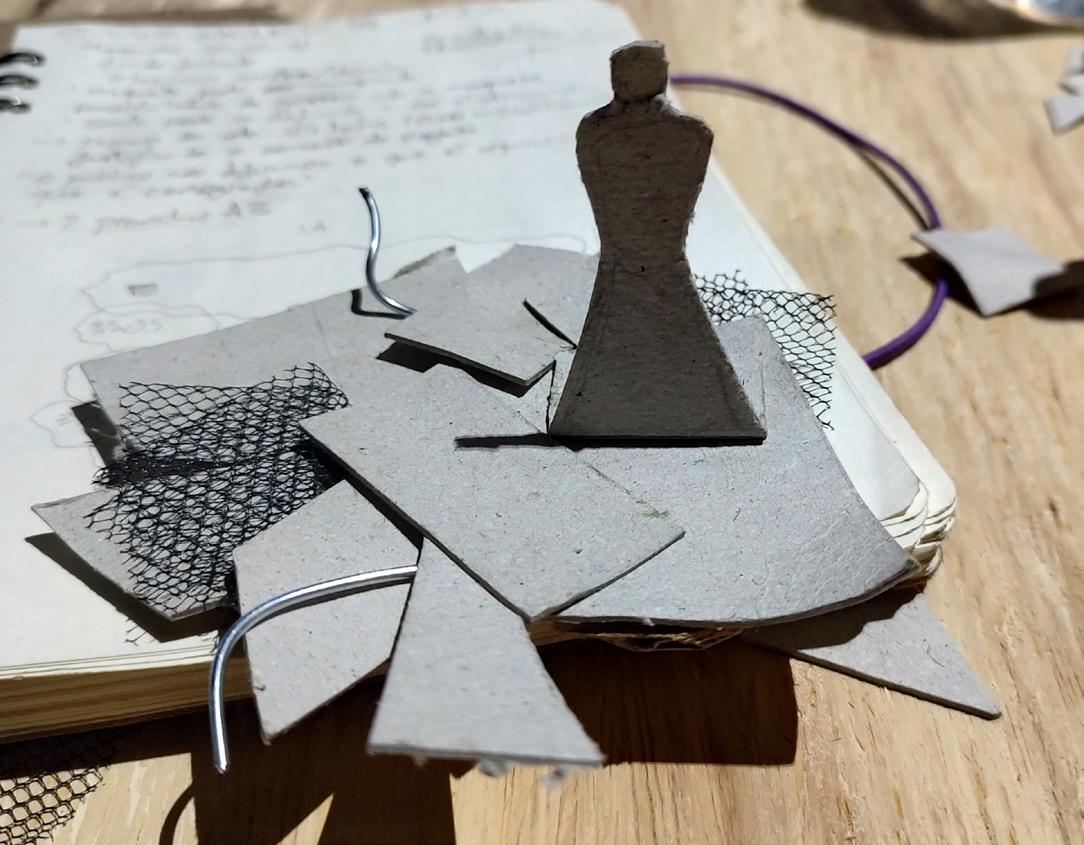

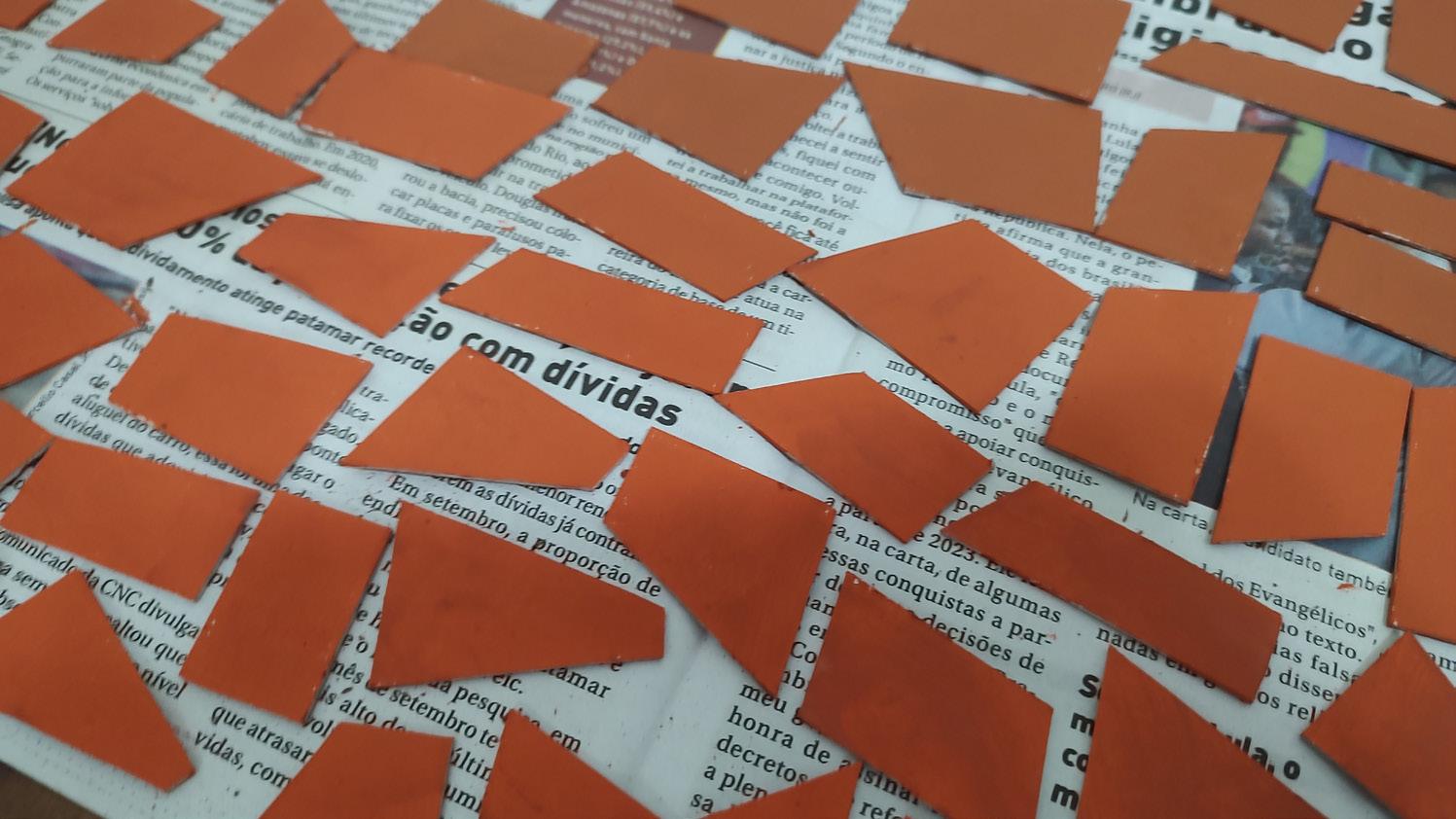

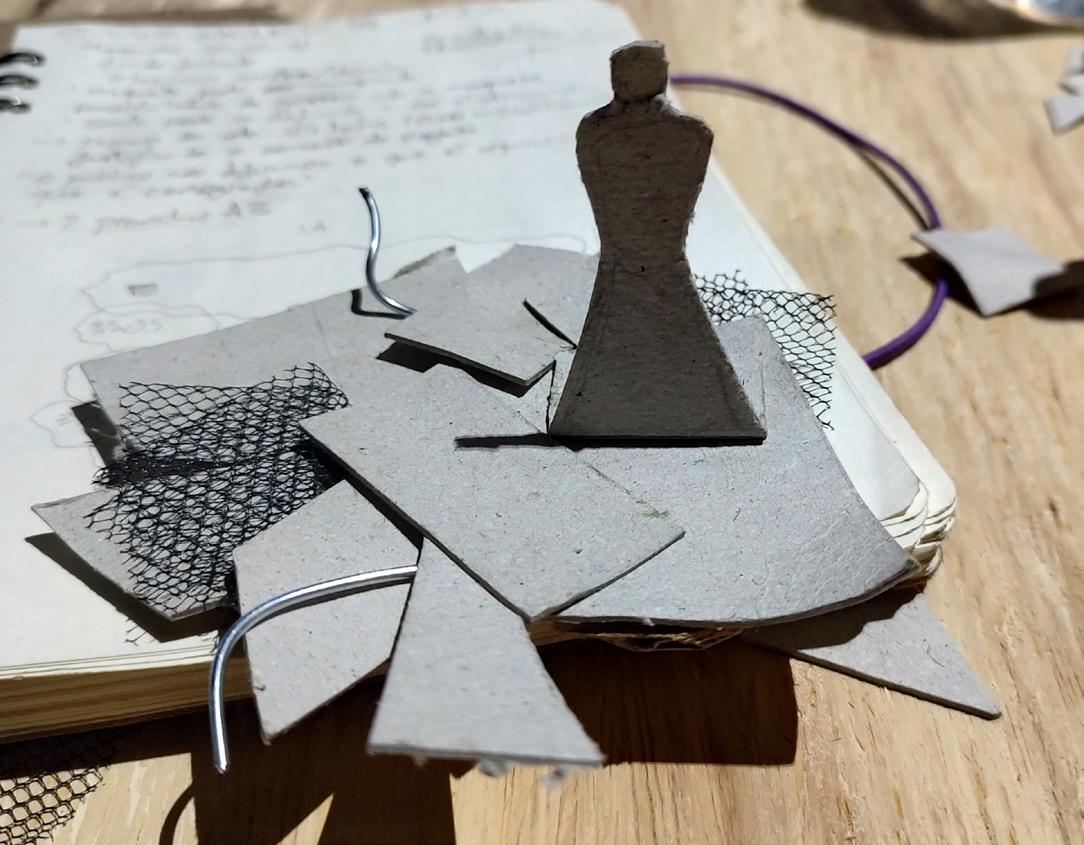

Para atingir esse impacto visual na maquete, produziu-se uma textura a partir de peças de papel paraná trabalhadas para se assemelharem a chapas enferrujadas, agregadas a peças de arame e metal.

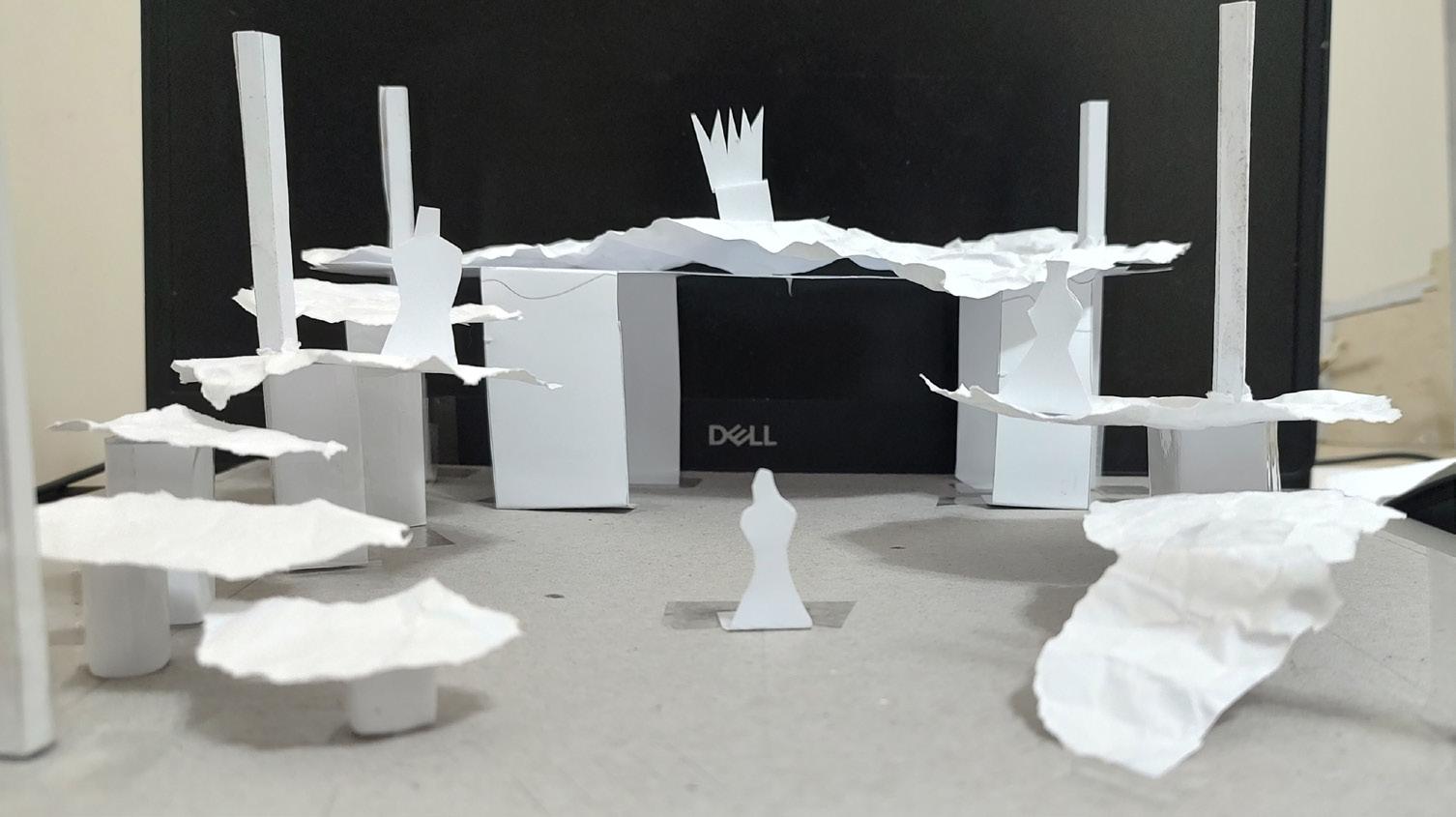

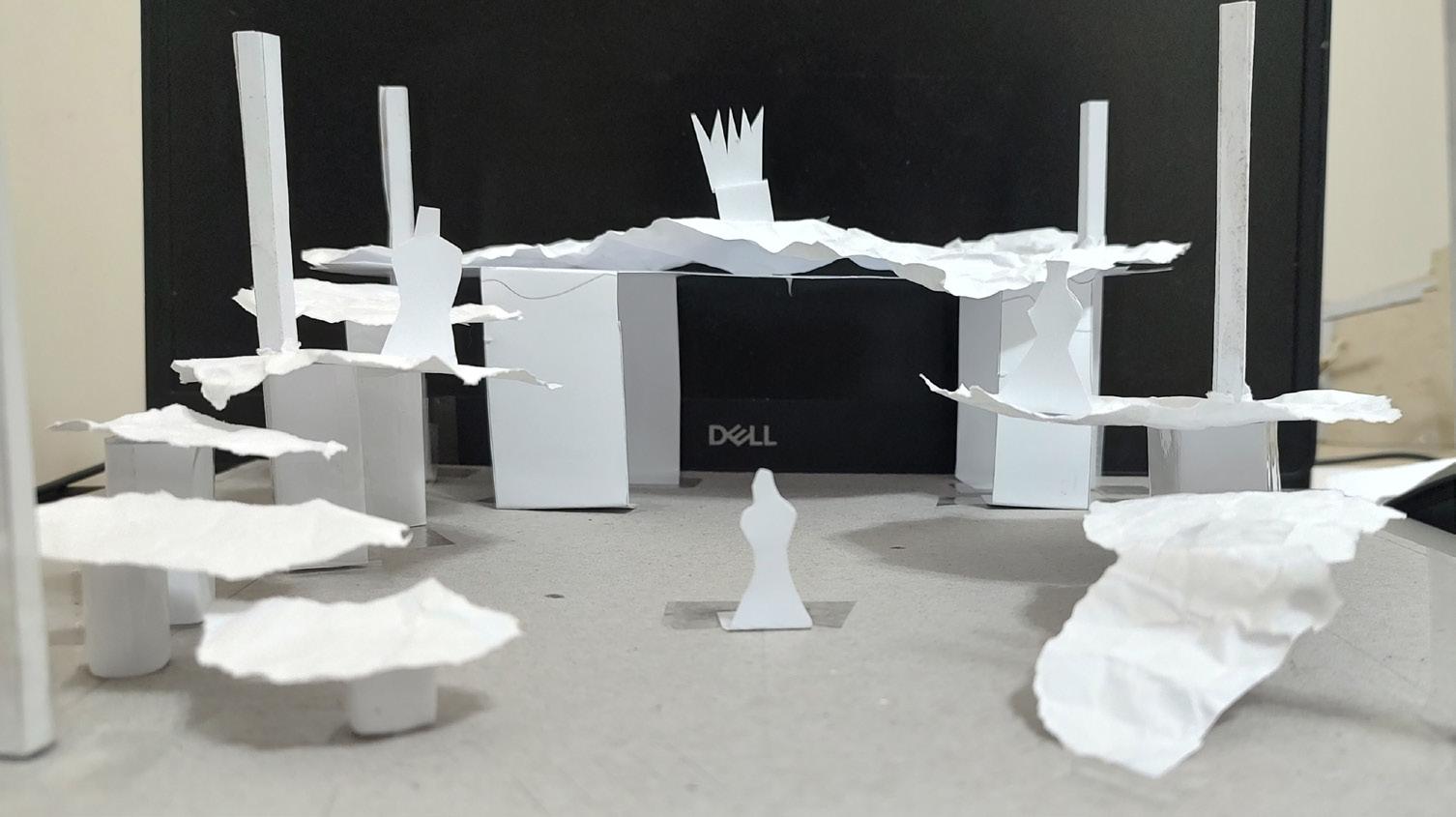

A partir da decupagem do texto, essa textura foi disposta em plataformas que conformam os espaços da ação. Entendeuse que durante a maior parte da peça as ações se desenrolam em dois espaços que precisam ser diferenciados entre si — os palácios de Gloucester e Albânia nos atos iniciais e os acampamentos francês e britânico ao final. Foram dispostas então duas plataformas maiores, uma em cada lado da cena, aproveitando a esquerda para oferecer acesso a uma plataforma central, ao fundo da cena, de maior altura.

Nessa plataforma foi constituído um espaço central que faz as vezes de trono, sendo efetivamente utilizado apenas na primeira cena, de repartição do reino, permanecendo vazio ao longo do desenrolar do restante da encenação. Esse vácuo, aliado à verticalidade construída através da disposição dessas plataformas, alude à cobiça pelo poder que destroça o reino na tragédia. As figuras humanas foram dispostas na maquete remetendo a uma encenação possível dessa cena inicial.

Sob a plataforma mais alta ao fundo da cena foram dispostas faixas remetendo à cena da tempestade, mas que permanecem presentes ao longo da peça, a tempestade sempre no horizonte. O espaço central, revestido de maneira a remeter a uma pós catástrofe, foi pensado para a encenação dos eventos externos, com os pilares de sustentação das plataformas conformando o cenário de “floresta” exigido para algumas dessas cenas.

Processo

The model’s production processes, involving an initial study of volumetry, a prototype of the platforms and the production of the final pieces.

Estudo de iluminação para as cenas da tempestade e da batalha.

de produção da maquete, envolvendo estudo volumétrico inicial, protótipo de plataforma e produção das peças finais.

Lighting studies for the storm and battle scenes.

TRADITION AND TRANSGRESSION IN SHAKESPEARE’S

KING LEAR

For the challenge of conceiving a possible scenography for the staging of Shakespeare’s King Lear, in the Armazém da Utopia in Rio de Janeiro, we focused on the interpretation of the work offered by Jan Kott in his essay “King Lear or Endgame” (In: KOTT, Jan. Shakespeare, nosso contemporâneo. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2003, p. 125-157).

For Kott, the tragic character of Shakespeare’s work observed in the great scenic productions of the Romantic period was lost when applying the Elizabethan tradition of little to no scenography. Thus, “(...) this crazy old man, who plucked strands of his long beard, suddenly became ridiculous. It should have been tragic, but it wasn’t anymore” (KOTT, 2003, p. 127, translated by the author).

The tragic is then replaced by the grotesque, in Kott’s view, comparable to Samuel Beckett’s Endgame:

(...) tragedy leads to catharsis, while the grotesque offers no consolation (...). Modern grotesque theater, on the other hand, usually has pure civilization as its scene; nature is almost entirely absent from it. The man is enclosed in a play, harassed by things and objects. But things currently play the same role as symbols of the human condition and man’s situation as the forest, the storm or the eclipse of the sun in Shakespeare (KOTT, 2003, p. 129-130).

Added to this view of Shakespearean tragedy was the understanding of Endgame as situated in a post-apocalyptic scenario as well as the very idea of a fractured kingdom present in King Lear to define the main concept of the proposal: a scenography that transgresses the binary nature-civilization, built by remnants of a civilization deteriorated to such an extent that they resemble inhospitable landscapes of nature.

To achieve this visual impact on the model, a texture was produced from pieces of cardboard worked to resemble rusty sheets of steel, added to pieces of wire and metal.

From the decoupage of the text, this texture was arranged on platforms that make up the spaces of the action. It was noted that during most of the play the actions take place in two spaces that need to be differentiated from each other — the palaces of Gloucester and Albania in the opening acts and the French and British camps at the end. Two larger platforms were then arranged, one on each side of the scene, taking advantage of the left one to offer access to a higher central platform at the back of the stage.

On this platform, a central space was built to serve as a throne, being effectively used only in the first scene, the division of the kingdom, remaining empty throughout the rest of the staging. This vacuum, combined with the verticality built through the organization of these platforms, alludes to the greed for power that shatters the kingdom in the tragedy. The human figures were arranged in the model referring to a possible staging of this initial scene.

Under the highest platform at the back of the scene, strips of cloth were placed for the storm scene, but remaining present throughout the play reference the storm always on the horizon. The central space, lined in such a way as to evoke a post-catastrophe scenario, was designed for the staging of external events, with the supporting pillars of the platforms forming the “forest” setting required for some of these scenes.

ARTUR TADEU PAULANI PASCHOA (1994) is a brazilian architect and scenography student based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He works in the field of scenography and on the artistic production of the traditional Rio de Janeiro Samba Schools’ Carnival Parade.

E-mail: arturtpp@gmail.com

PRAGUE QUADRIENNAL OF PERFORMANCE DESIGN AND SPACE |

|

PAVILION AT THE STUDENT’S EXHIBITION | CIA. ENSAIO ABERTO | ARMAZÉM DA UTOPIA | RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL |

PRAGUE, 8-18 JUNE 2023

BRAZILIAN