7 minute read

Balancing Phenotype and Genomics

by Ryan Boldt, IGS Lead Geneticist

With advancements in genomic technology, do I still need to turn in birth weight, weaning weight, and yearling weight data, and other phenotypes on my herd?

In the age of genomic testing and genomically enhanced EPD, do we really need to collect phenotypes? This is a question that is asked of me from time to time, and it is a good one. For those who are wanting a summary, the answer is yes. The collection of phenotypic information is still necessary and arguably more necessary than prior to the incorporation of genomics into single-step genetic evaluations.

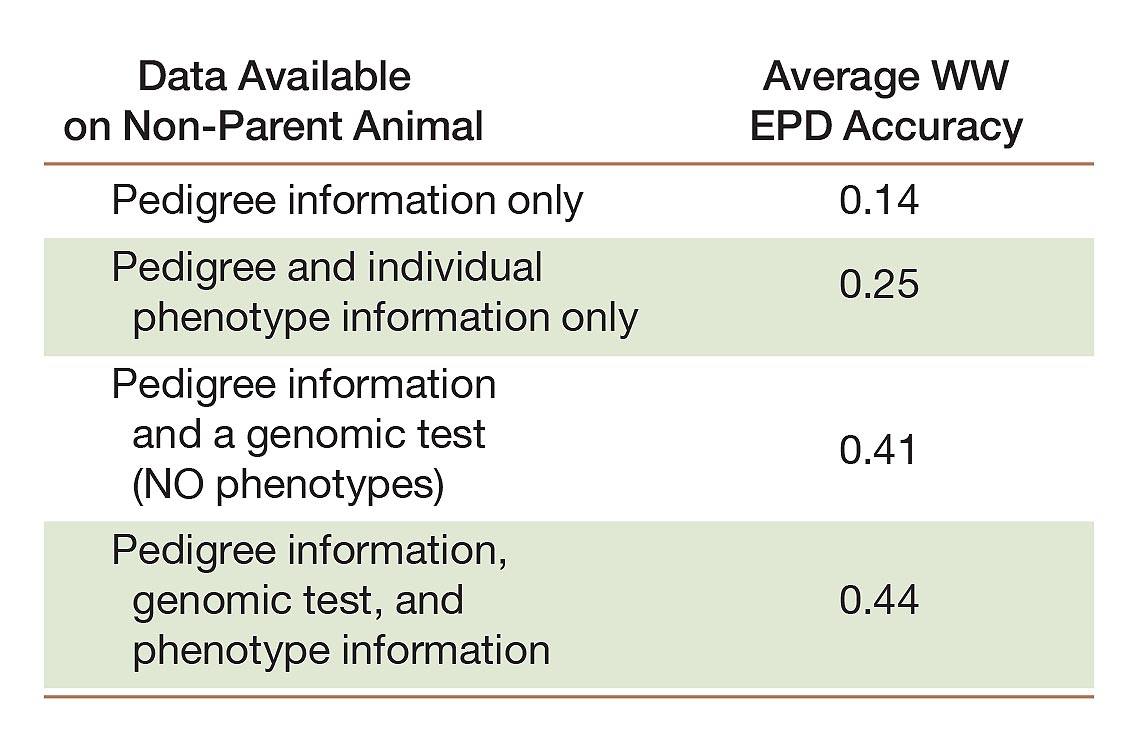

This illustrates that as data is added to the prediction of non-parent animals, the accuracy of the EPD increases. However, the question becomes that, without a phenotype, an animal with genomics has a higher accuracy than an animal with only a phenotype recorded. This tradeoff is largely the reason for the misunderstanding that the genetic evaluation is at a point where phenotypes are not required. However, previous studies have shown that if we do not continue to supply the evaluation with both genomic and phenotypic information, the accuracy of the genomic portion of the EPD calculation quickly diminishes.

The ability of genomic data to predict and improve EPD accuracy is dependent on the amount of the variation that can be explained by the markers included in the model.

In terms of genetic prediction, the types of variation that are most important are phenotypic and genetic variation. Phenotypic variation is the amount of variation that is seen in the measurements that are collected on animals or the total amount of variation. This variation is influenced by not only the genetics of the animal, but also the environment that the animal experiences. When it comes to genetic prediction and genetic improvement, the amount of variation that can be explained due to differences in genetics that can be inherited is known as additive genetic variation. The important distinction here is that we want to focus on the genetics that can be inherited from one generation to the next. In terms of genomics being the only source of data used for genetic prediction, then the

genotype would be required to account for 100% of the genetic variance of the trait. While genotypes can account for a certain portion of the variation in each trait, the ability of genotype information to account for all genetic variation has not been achieved in any trait. Also, the amount of variation that the genotype can account for does improve over time as more animals have both genotypes and phenotypes included in the evaluation. There are situations where the ability to get genetic predictions for a trait is solely through genomic data. These situations are when collection of phenotypes is extremely cost prohibitive. Therefore, the only tangible way to be able to create predictions is through collection of the phenotypes on a subset of animals with genomic

data and identify what genomic markers are most influential and their effect. Then this can be applied to a larger group of animals.

Inclusion of genomic information into EPD calculations does improve EPD accuracy, especially on young, non-parent animals. The inclusion of both phenotype and genotype information on animals leads to the maximum accuracy at a young age to make selection decisions. On a larger scale, the more animals that have the maximum amount of information the more accurate predictions will be for all animals included in a genetic evaluation. .

Corporate Report

JBS Touts $150M in Sustainability Investments

Amid continuing congressional pressure on the matter, JBS unveiled a sustainability report touting its accomplishments.

In the report, JBS stated it has invested “more than $150 million” across its global facilities to reduce Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions, and since 2019, “intensity” of emissions is down by 17%.

Specifically, the report detailed transparency/traceability in Brazil’s livestock supply chain, climate-smart facility upgrades in the UK, and methane-to-renewable-energy conversion initiatives in Australia and the United States.

“As we tackle the many sustainability topics that need our attention, taking a systems approach is key,” said Jason Weller, JBS Chief Sustainability Officer, in the report. “This encourages and allows for innovation, collaboration, prioritization, and investment — all of which are essential to making meaningful progress.”

The report included details about JBS’ overall business: As of Q4 2023, the processor’s revenue was $73 billion; JBS is the number one processor of poultry and beef in the world, and number two in pork; 50% of its business is concentrated in the US, with 27% in Brazil, 9% in Australia and New Zealand, 7% in Europe, 4% in Canada, and 3% in Mexico; and it is also number one in prepared foods in Australia and the UK.

Tyson Settles with One Farmer in Missouri Plant Closure Lawsuit

Lawyers for Tyson Foods told a federal court the company reached an agreement with one farmer to settle a lawsuit that alleged the poultry giant engaged in anti-competitive behavior when it closed its facility in Dexter, Missouri.

The case originated in a state court but was moved up to a federal court last month. In a filing in August, lawyers from Tyson revealed that the two sides agreed to a settlement at the end of July. The terms of the deal were not disclosed.

Forty-five broiler growers who contracted with Tyson to raise chickens for the processor filed the class-action lawsuit in the county’s circuit court in June, contending Tyson failed to live up to its commitment to sell its Dexter facility to a competing meatpacker and instead sold it to an egg producer.

Last week, Grandview Poultry, which was the lead plaintiff in the case, filed a notice to voluntarily dismiss the lawsuit with prejudice, meaning the case is permanently closed. However, Tyson still has an ongoing class-action lawsuit with the rest of the farmers.

Beyond Meat Paying One Third of Bills Late

Data from Creditsafe show that Beyond Meat is struggling to pay its bills, with 36% of payments 91 days late or more so far in 2024, according to an article by Food Dive. In July, 32.8% of bills were one to 30 days late, and another 13.2% were 31 to 60 days late, the data show.

“When a company has an erratic pattern of paying bills on time, it’s usually an indication of larger financial issues at play,” wrote Ragina Bhalla, head of brand and spokesperson at Creditsafe, in an email to Food Dive. “What really stood out was how unstable the company’s payment behaviors have been over the last 12 months.”

The article noted that Beyond Meat had made late payments of 91 days or more that leapt from 9.7% of bills in October 2023 to 42.3% in November and 69.7% in December; and that the firm reported its ninth straight quarter of falling revenue, year-overyear, for the second quarter of 2024. Yet, “CEO Ethan Brown assured investors on its August 7 conference call that the company was making progress on streamlining its manufacturing and holding down costs,” Food Dive noted.

Beyond Meat did not respond to the publication’s request for further comment. .