9 minute read

Measure Yield to Maximize Milling Benefits

MEASURE YIELD TO MAXIMIZE MEASURE YIELD TO MAXIMIZE MILLING BENEFITS MILLING BENEFITS

LLocated in the Hudson Valley alongside the Hudson River about 70 miles north of New York City, East Fishkill, New York, is home to around 30,000 residents. For three of the past four years, Intercounty Paving Co. (IPC), Carmel, New York, has won the bid to perform the paving and pavement maintenance work in the town.

BY SARAH REDOHL

However, 2021 was the first year the town’s highway supervisor agreed to allow IPC to mill prior to paving.

“Milling is nothing new on highways or state roads, but in our area towns are just starting to adopt the practice,” said Project Manager Tyler Spano. “We’re seeing that trend and we want to be on the leading edge of it.”

Spano has been working to educate highway superintendents in IPC’s area of operation on the benefits of milling. “Not only does it maintain current elevation, but it reduces reflective cracking and results in a smoother ride,” Spano said.

However, many municipalities have been reluctant to try a new process with which

LEFT: Spano has been working to educate highway superintendents in IPC’s area of operation on the benefits of mill-and-overlays. TOP: In addition to paving more than 10,000 tons of asphalt in East Fishkill—including several mill-and-pave projects—IPC also performed mill-andoverlay jobs in two other New York towns, Yorktown and Sommers, in 2021. BOTTOM: After the crew milled off 2 inches of pavement with its Wirtgen 200 milling machine, broomed and applied tack coat, it paved 2 inches of New York state 6F top mix asphalt with its Caterpillar 555 paver equipped with Cat grade control. All photos courtesy of Nick Spruck.

they are unfamiliar. “For years, they’ve just paved on top of the existing pavement,” Spano said. For decades that approach worked, but eventually road elevation became a problem. All the catch basins and manholes were low, and municipalities began to experience more callbacks from residents asking to have a lip paved on their driveways.

When East Fishkill hired a new highway superintendent, Ken Williams, one who was open to trying new things, Spano took his shot. He explained the benefits of milling, including how it minimizes trimming and leveling and could reduce the total amount of required asphalt. “I explained how those savings could be applied to the cost of milling,” Spano said. “In the end, a 2-inch mill-and-pave was only 10 percent more than their traditional 2.5-inch overlay with leveling and made for a much better pavement.”

It also didn’t hurt that IPC had multiple years of history performing work for the municipality. Williams gave them a chance to illustrate to him the benefits of milling and paving on a ¾-mile section of East Fishkill’s Dale Road in September 2021.

“It’s probably not by accident that they wanted to test out a mill-and-overlay on a small project first,” Spano said. He knew he and his crew had to bring their A game. “I’d been in his ear all year about milling, so if the job didn’t come out right I knew they’d never mill and pave again.”

MAKE THE CASE WITH A TEST CASE

After the crew milled off 2 inches of pavement with its Wirtgen 200 milling machine, broomed and applied tack coat, it paved 2 inches of New York state 6F top mix asphalt with its Caterpillar 555 paver equipped with Cat grade control and Carlson EZIV screed. They compacted the mat with a Cat CB 10 10-ton roller for breakdown and Bomag 138 5-ton roller for finishing and compacting up against the country curb.

In total, the job required around 1,200 tons of asphalt, which IPC purchased from Thalle Industries in Fishkill.

Keeping close track of their yield was key to the project’s success, since the reduced asphalt tonnage helped the municipality afford to mill. “I told the highway superintendent that we could use less asphalt if we milled and paved,” Spano said. “If we went over, that disproved my theory.”

IPC has worked with paving consultant John Ball of Top Quality Paving and Training, Manchester, New Hampshire, for years. Among the skills they’ve picked up is how to measure and monitor yield throughout the project. The company honed its measuring skills on its private jobs, where blowing their yield could mean breaking even on a project. Half of the company’s work is for municipalities, the rest is parking lots, condos and private roads.

“Even when we get paid by the ton, it’s a good practice to have,” Spano said. “Regardless of the job, the materials we’re playing with are expensive. We try to be right on the money with tonnage.”

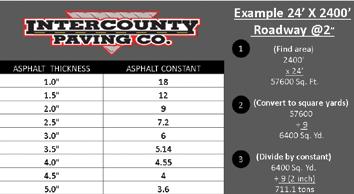

Spano calculated the yield for the whole project, and then divided it by each pass. Spano set off with his measuring wheel and began marking out the milled pavement with anticipated yield at several points throughout the project so he could monitor and control tonnage as the crew paved. This is the yield formula Spano uses for IPC’s projects.

“If I have the load ticket in my hand, and I know how far 21 tons should have taken me on a 10-foot-wide pass, I can easily monitor how close we are to our initial calculations,” Spano said. It also helps him call for the right number of additional trucks as the crew gets close to finishing for the day.

Between markings, Spano relies on the smartphone app Measure Map. “I can sit on the paver and lock in my location, draw a line to the end of the road and it will tell me how far I am from the end of the road,” He then multiplies that linear footage by the width of the pass to figure the balance of the unpaved area.

“Measuring beforehand, marking on the ground how much each pass calls for, and checking that against each pass is a lot of work,” Spano said, “but it’s worth it because we’re dealing with a lot of money.”

CALCULATE & COMMUNICATE

On the Dale Road job, Spano’s calculations were within 20 tons of the amount of asphalt the crew ultimately placed. “That’s pretty good, especially with the challenge of calculating with the country curb on both sides,” he said.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: IPC utilizes Sonetics wireless headsets to communicate with one another on the job site.; IPC compacted the mat with a Cat CB 10 10-ton roller for breakdown and Bomag 138 5-ton roller for finishing.; The job also called for a country curb, which is a 4-inch tall integrated berm on both sides of the road.; Keeping close track of their yield was key to the project’s success, since the reduced asphalt tonnage helped the municipality afford to mill. In total, the job required around 1,200 tons of asphalt.

The geometry of the job was tricky, with about two dozen driveways tying in and ending in a cul de sac. The job also called for a country curb, which is a 4-inch tall integrated berm on both sides of the road.

Country curbs are quite common in the northeast and growing in popularity year by year, Spano said, since they are more cost effective than installing costly concrete curbs that frequently get damaged by snow plows.

To create the berm, the last 12 inches of IPC’s Carlson screed extension is angled upward to pave a wedge that is 4 inches taller at the end gate than the rest of the pass.

Spano calculated yield for the country curb by adding 1 foot to each side of the road. “If the road is 20 feet wide and has a country curb on both sides, I’ll figure the yield as though the road is 22 feet wide,” he said, since the area of a triangle with a base of 12 inches and a height of 4 inches is 24 square inches (or, the same area of a 12-inch-wide by 2-inch-tall lift).

The country curb is uncompacted, achieving a density of 77 percent from the strikeoff.

To calculate the yield of the cul de sac, Spano will use the formula for the area of a circle if the cul de sac is a perfect circle. Otherwise, he will use the Measure Map app to draw around the cul de sac to get its square footage and perimeter.

With the unique challenges on this job in terms of yield, constant communication was a useful tool on the project. IPC utilizes Sonetics wireless headsets to communicate with one another on the job site.

Spano, who usually runs IPC’s milling crew, would often find that he needed to stop milling in order to communicate with other members of the crew. “If I have to get off the machine to tell him what to do, that reduces my own productivity,” he said. With the headsets, everyone on the crew can hear one another clearly. “They really improve our efficiency.”

If Spano is out measuring and the paver operator needs to know the yield on the paving job, Spano can tell him his measurements from 400 feet away without stopping the paver, and the screed operator will hear the answer simultaneously. “Everyone is talking about the job and how it’s moving versus how it should be moving,” Spano said.

MILL MORE

“We had to nail the job on Dale, because we only had one shot to show the benefits of milling,” Spano said. And they did. After IPC finished its project on Dale Road, East Fishkill’s highway superintendent opted to have them mill and pave an entire neighborhood, a 3,200ton job on the aptly named Miller Drive.

In addition to paving more than 10,000 tons of asphalt in East Fishkill—including several mill-and-pave projects—IPC also performed mill-and-overlay jobs in two other New York towns, Yorktown and Sommers, in 2021.

“It’s hard to convince someone to spend money, but once they see the value of not getting called back and ending up with a better product, it speaks for itself,” Spano said. “The best part of this job was the opportunity to prove to the municipality that this process is the way to go.”